Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

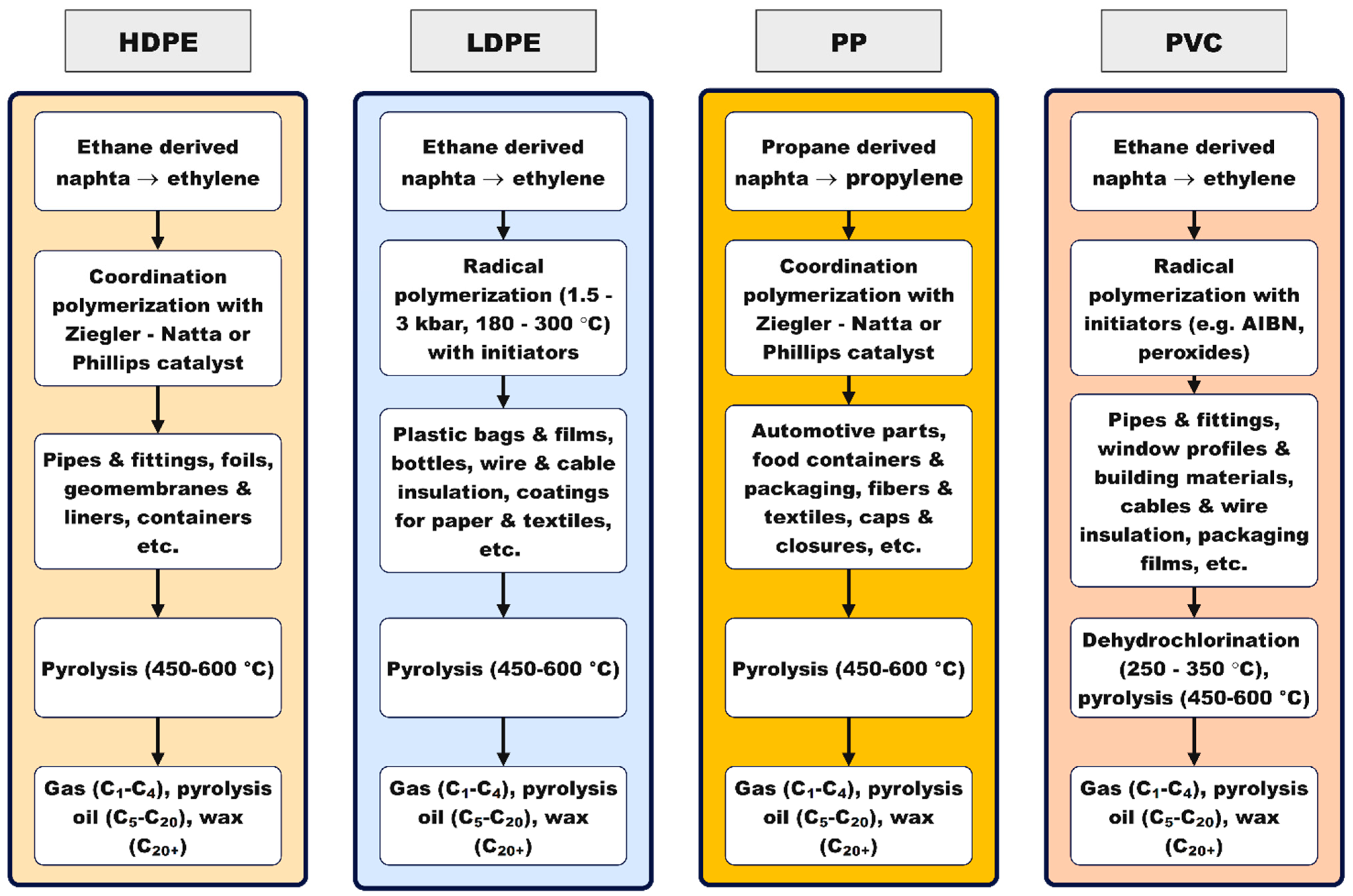

2. Coordination and Radical Polymerization Mechanisms in the Synthesis of HDPE, LDPE, PP, and PVC

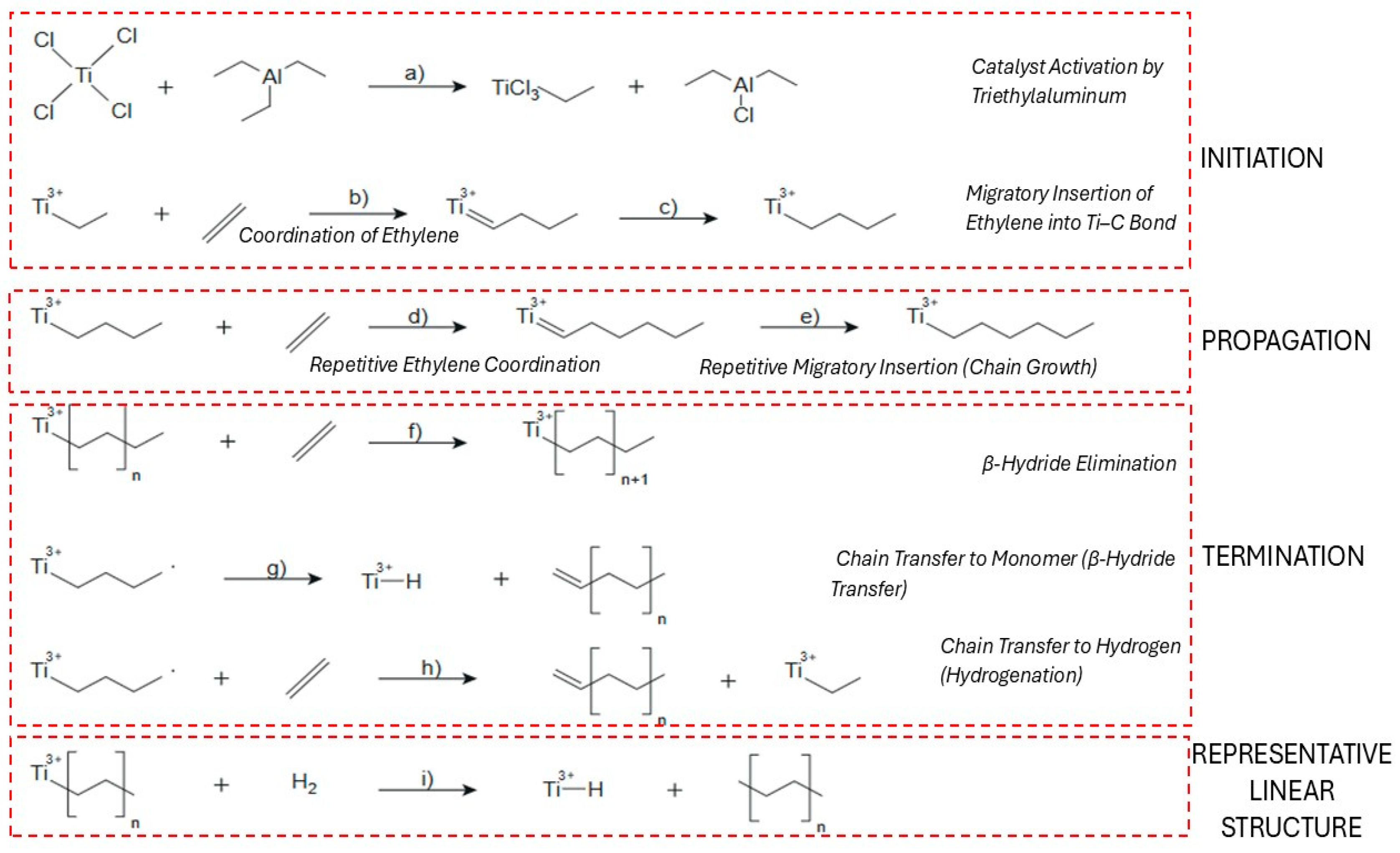

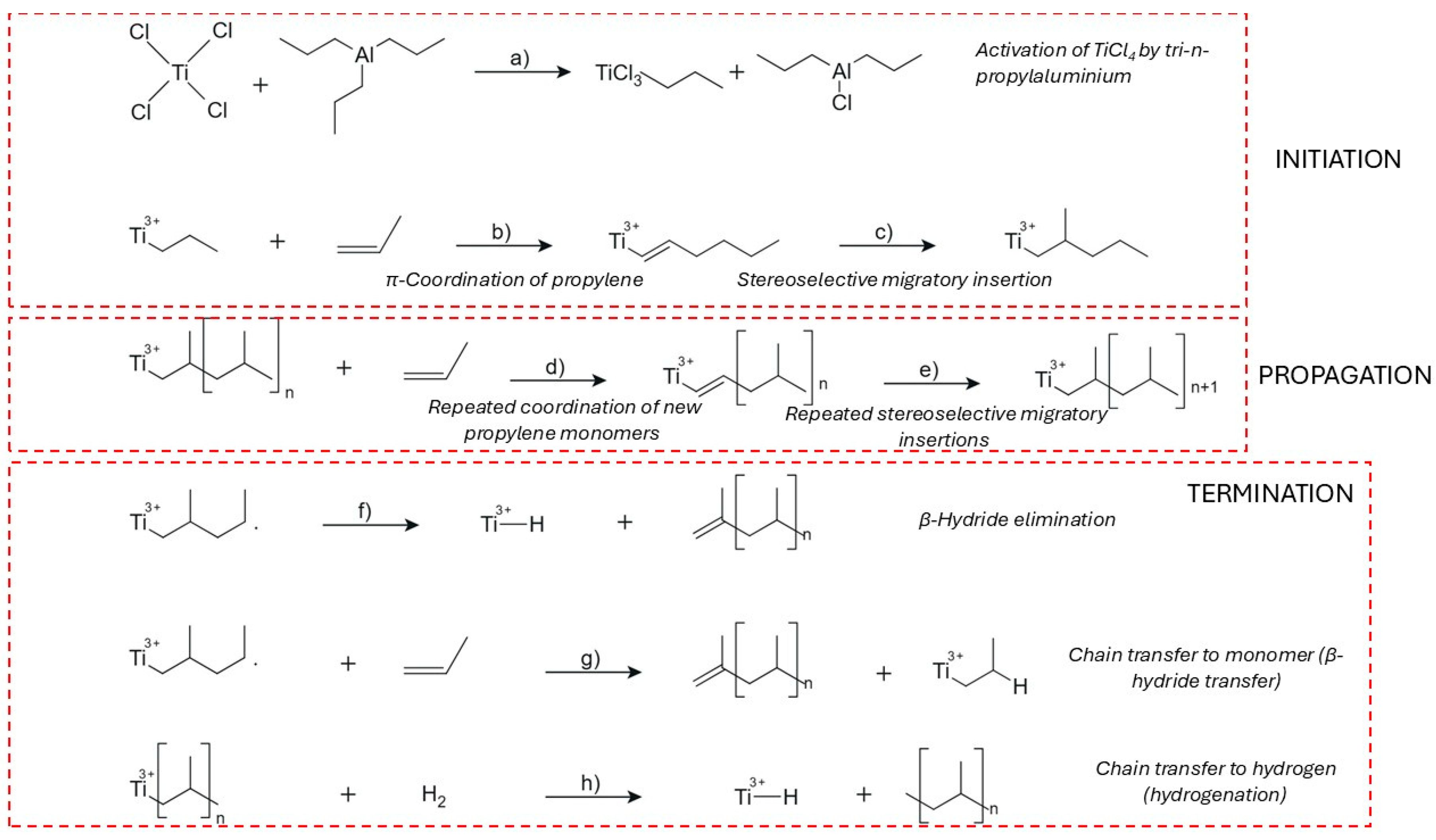

2.1. Coordination Polymerization Mechanism of HDPE and PP

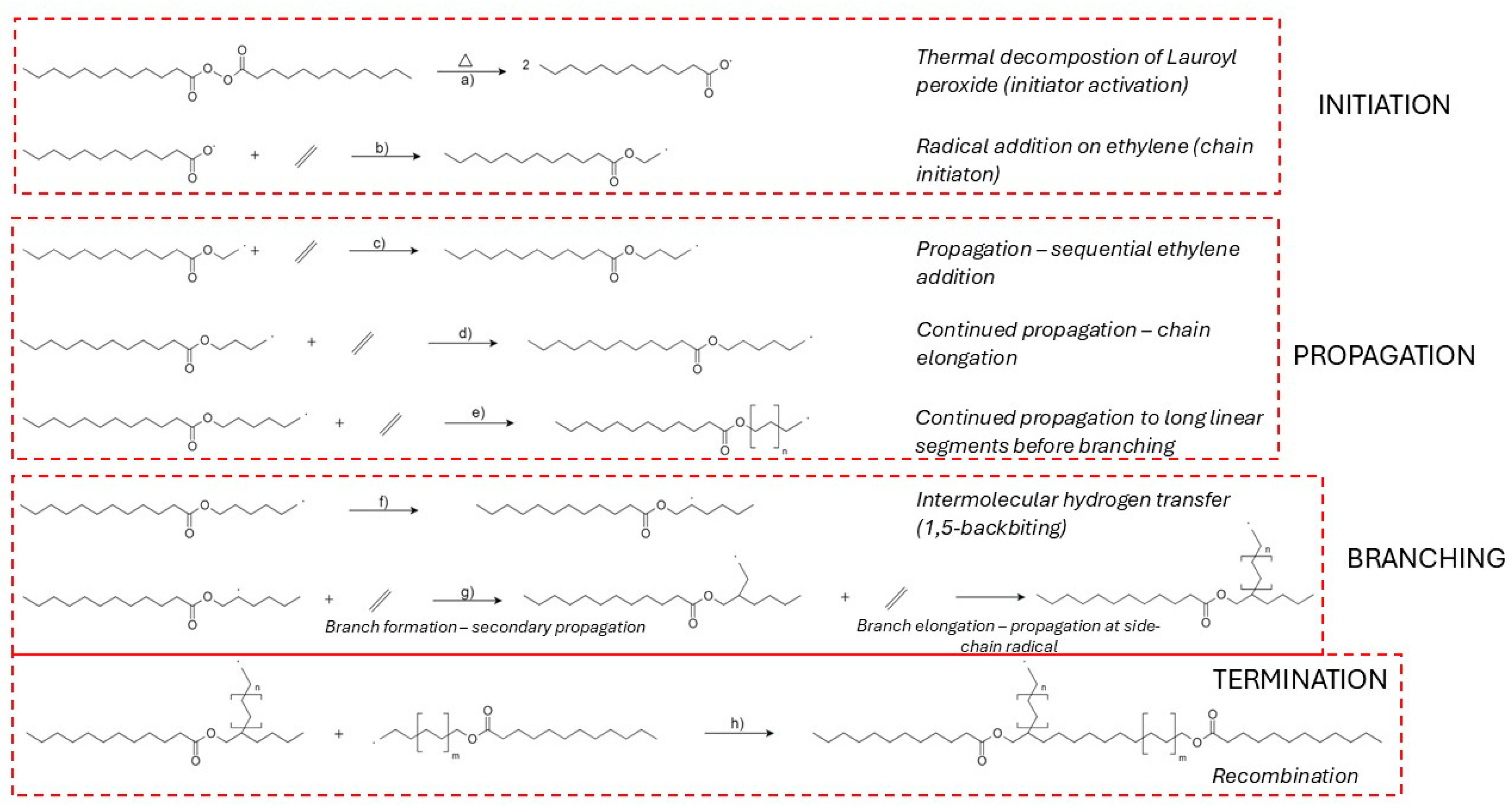

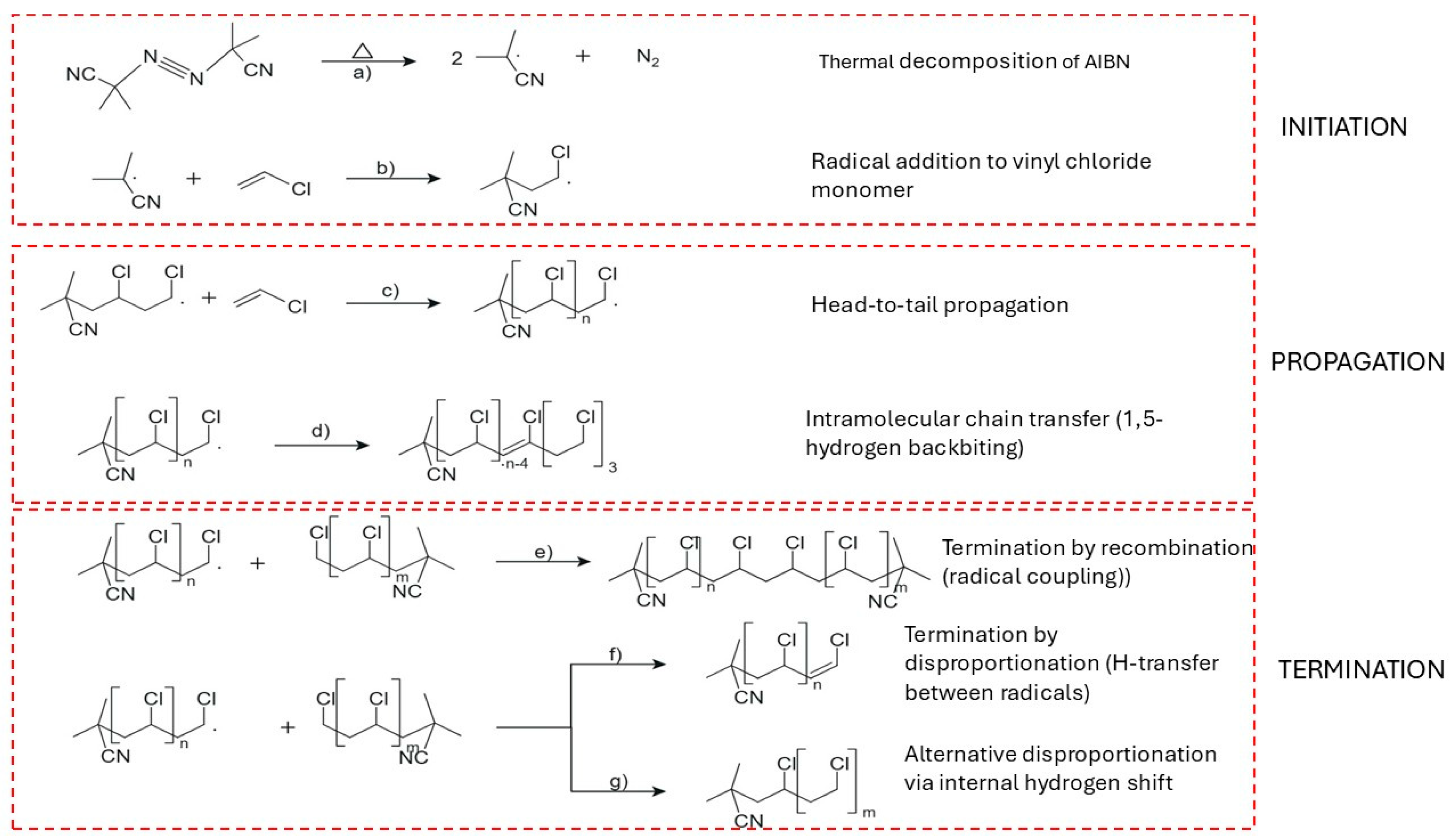

2.2. Free Radical Polymerization of LDPE and PVC

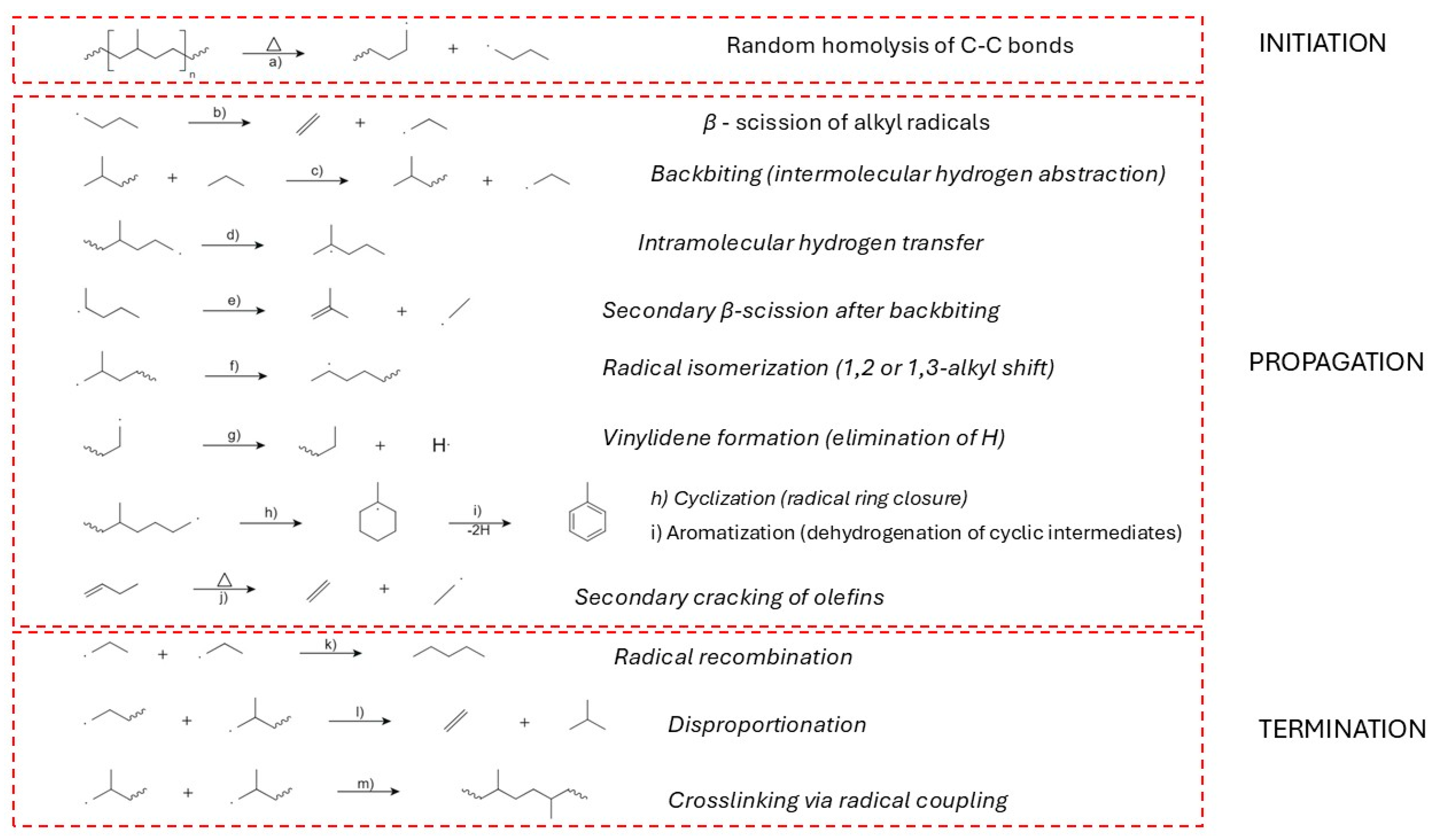

3. Mechanistic Pathways and Kinetic Features of Thermal Degradation in Polyolefins and PVC

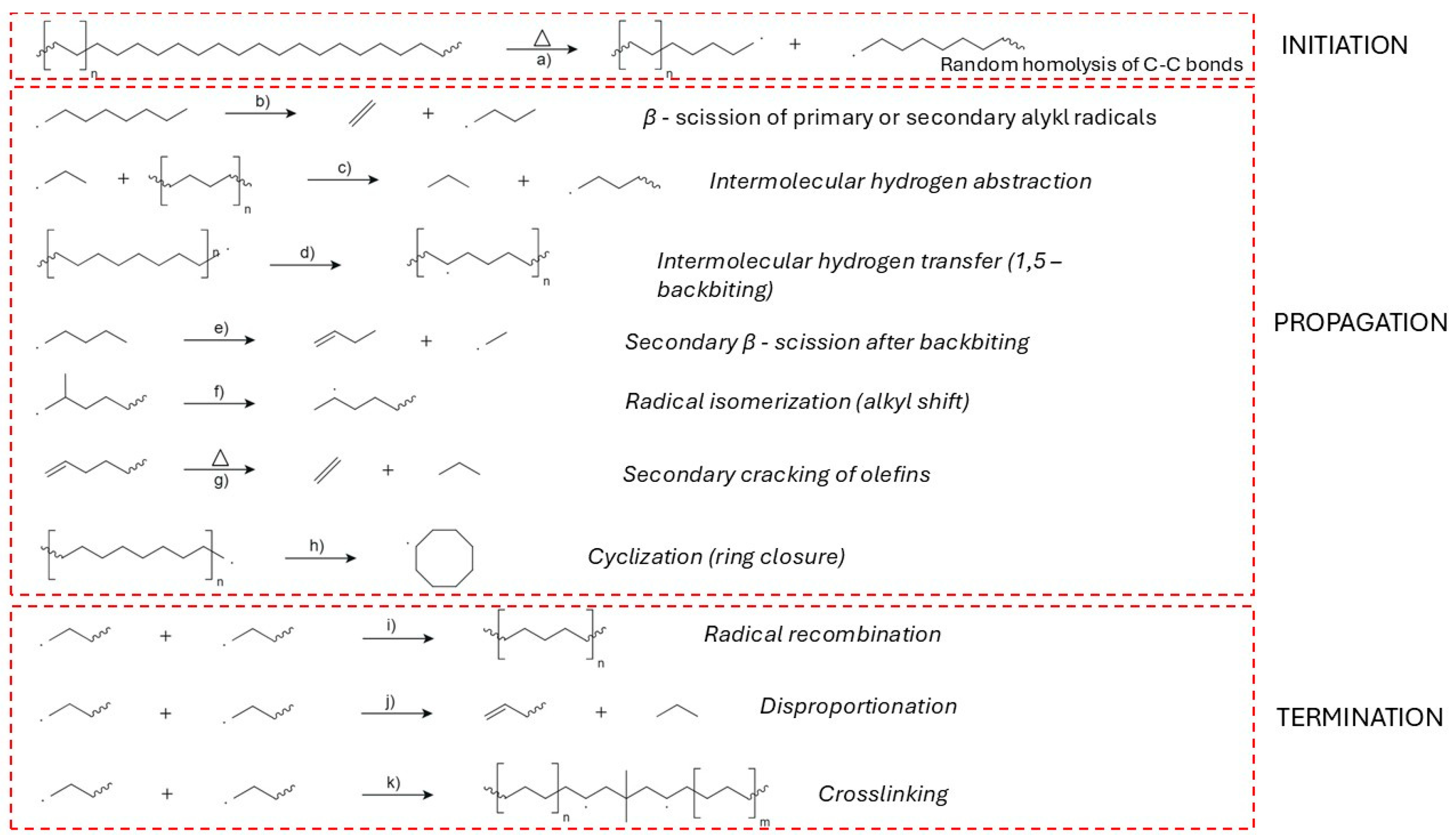

3.1. HDPE

3.2. LDPE

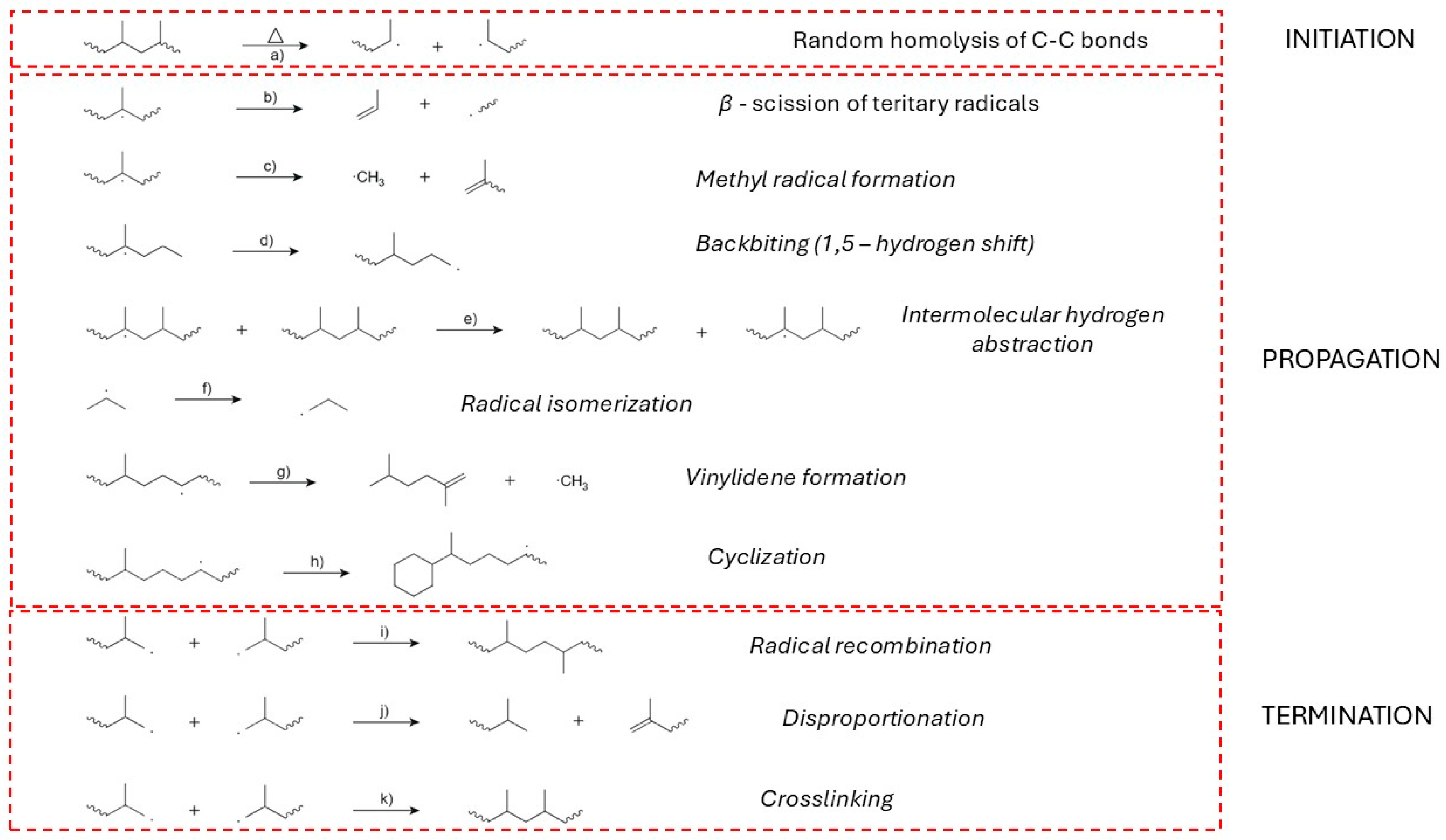

3.3. PP

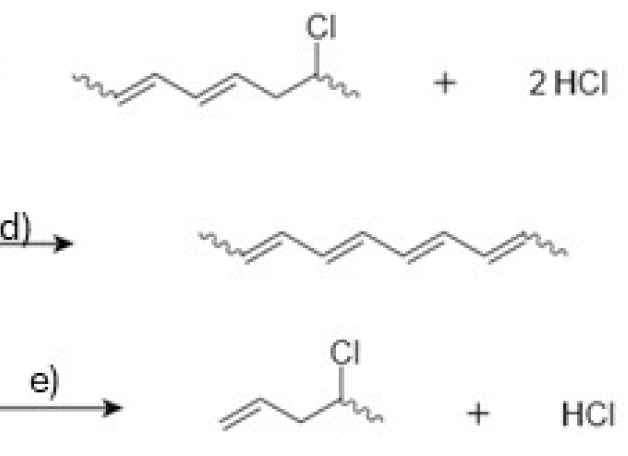

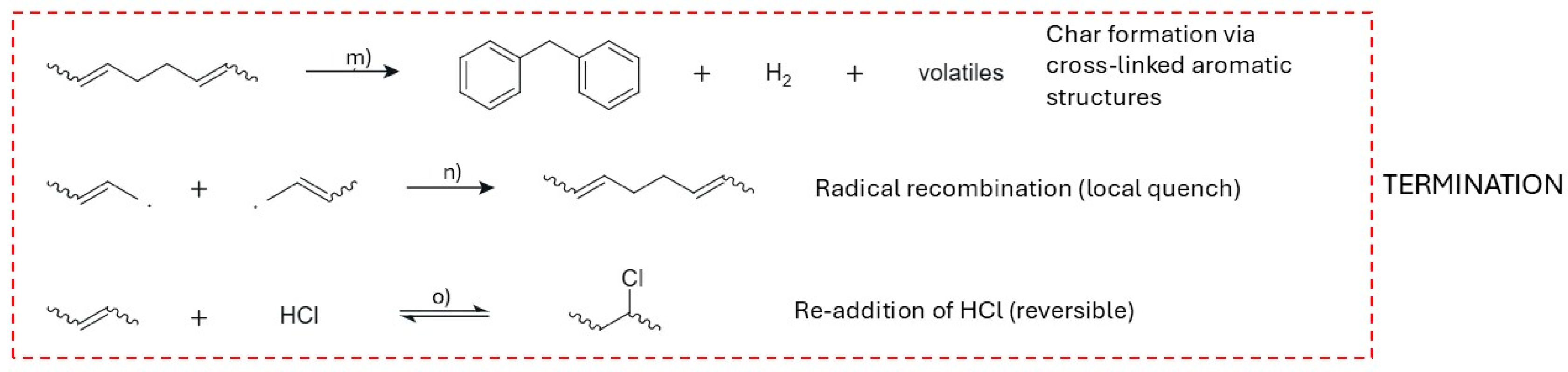

3.4. PVC

4. Tuning Thermal Degradation Pathways with Potential Catalysts and Initiators: Lowering Onset and Enabling Selective Termination

4.1. Polyolefins and PVC Inffluence of Catalyst, Initiators and Termiantion Procedures

4.1.1. Catalyst Effect for HDPE, LDPE, PP and PVC Pyrolysis

4.1.2. Initiator Effects for HDPE, LDPE, PP and PVC Pyrolysis

4.1.3. Termination Strategies for HDPE, LDPE, PP and PVC Pyrolysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, J.; Dong, J.; Gao, L.; Zhao, Y.-Q.; Moon, H.; Scott, S.L. Catalytic Upcycling of Polyolefins. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 9457–9579. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Tang, J.; Fu, L. Catalytic Strategies for the Upcycling of Polyolefin Plastic Waste. Langmuir 2024, 40, 3984–4000. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, K.; Denifl, P.; Hapke, M. Recent Advances in Catalytic Chemical Recycling of Polyolefins. ChemCatChem 2023, 15, e202300310. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, E.C.R. Pyrolysis of Polyvinyl Chloride, Polypropylene, and Polystyrene: Current Research and Future Outlook. Eng. Proc. 2023, 56, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Svadlenak, S.; Wojcik, S.; Ogunlalu, O.; Vu, M.; Dor, M.; Boudouris, B.W.; Wildenschild, D.; Goulas, K.A. Upcycling of Polyvinyl Chloride to Hydrocarbon Waxes via Dechlorination and Catalytic Hydrogenation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 338, 123065. [CrossRef]

- Kruse, T.M.; Wong, H.; Broadbelt, L.J. Mechanistic Modeling of Polymer Pyrolysis : Polypropylene. 2003, 36, 9594–9607. [CrossRef]

- Popov, K. V; Knyazev, V.D. Initial Stages of the Pyrolysis of Polyethylene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 11737–11760. [CrossRef]

- Gascoin, N.; Fau, G.; Gillard, P.; Mangeot, A. Flash Pyrolysis of High Density Polyethylene. 49th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Jt. Propuls. Conf. 2013, 1 PartF. [CrossRef]

- J V, J.; Perez, B.; Toraman, H. Parametric Study of Polyethylene Primary Decomposition Using a Micropyrolyzer Coupled with Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Jing, X.; Wen, H.; Xiang, S. Thermal Cracking of Virgin and Waste Plastics of PP and LDPE in a Semibatch Reactor under Atmospheric Pressure. Energy & Fuels 2015, 29, 2289–2298. [CrossRef]

- Marcilla, A.; Beltrán, M.I.; Navarro, R. Evolution of Products Generated during the Dynamic Pyrolysis of LDPE and HDPE over HZSM5. Energy & Fuels 2008, 22, 2917–2924. [CrossRef]

- Hujuri, U.; Ghoshal, A.; Gumma, S. Temperature-Dependent Pyrolytic Product Evolution Profile for Polypropylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 119, 2318–2325. [CrossRef]

- Danforth, J.D.; Spiegel, J.; Bloom, J. The Kinetics and Mechanism of the Thermal Dehydrochlorination of Poly(Vinyl Chloride). J. Macromol. Sci. Part A - Chem. 1982, 17, 1107–1127. [CrossRef]

- Nolan, K.; Shapiro, J. Presence of Dual Mechanism in Poly(Vinyl Chloride) Dehydrochlorination. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Symp. 2007, 55, 201–209. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Papanikolaou, K.G.; Cheng, F.; Addison, B.; Cuthbertson, A.A.; Mavrikakis, M.; Huber, G.W. Kinetic Study of Polyvinyl Chloride Pyrolysis with Characterization of Dehydrochlorinated PVC. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 7402–7413. [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Velazquez, A.; Calderon, H.S.; Brown, G.R. Studies of the Solid-State Thermal Degradation of PVC. I. Autocatalysis by Hydrogen Chloride. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1992, 46, 179–187. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.-H.; Liang, Y.C. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Polyvinylchloride in the Presence of Metal Chloride. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000, 77, 2464–2471. [CrossRef]

- Ballistreri, A.; Foti, S.; Maravigna, P.; Montaudo, G.; Scamporrino, E. Effect of Metal Oxides on the Evolution of Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Thermal Decomposition of PVC. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. Ed. 1980, 18, 3101–3110. [CrossRef]

- Lattimer, R.P.; Kroenke, W.J. Mechanisms of Formation of Volatile Aromatic Pyrolyzates from Poly(Vinyl Chloride). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1982, 27, 1355–1366. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.J.; Donaldson, J.D. Determination of HCl and VOC Emission from Thermal Degradation of PVC in the Absence and Presence of Copper, Copper(II) Oxide and Copper(II) Chloride. J. Chem. 2009, 6, 753835. [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y.; Hu, B.; Sun, H.; Li, J.; Lu, Q. Migration and Transformation Mechanism of Cl during Polyvinyl Chloride Pyrolysis: The Role of Structural Defects. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 224, 110750. [CrossRef]

- Beneš, M.; Milanov, N.; Matuschek, G.; Kettrup, A.; Plaček, V.; Balek, V. Thermal Degradation of PVC Cable Insulation Studied by Simultaneous TG-FTIR and TG-EGA Methods. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. - J THERM ANAL CALORIM 2004, 78, 621–630. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Sun, Z.; Hou, K.; Wang, G.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z. Quantifying the Modulation of Modified ZSM-5 Acidity/Alkalinity on Olefin Catalytic Pyrolysis to Maximize Light Olefin Selectivity. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 115, 101688. [CrossRef]

- Farah, E.; Demianenko, L.; Engvall, K.; Kantarelis, E. Controlling the Activity and Selectivity of HZSM-5 Catalysts in the Conversion of Biomass-Derived Oxygenates Using Hierarchical Structures: The Effect of Crystalline Size and Intracrystalline Pore Dimensions on Olefins Selectivity and Catalyst Deactivatio. Top. Catal. 2023, 66, 1310–1328. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Gong, Y.; Wang, P.; Zheng, A.; Wang, Z.; Sha, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Xin, M.; Cao, D.; Song, H.; et al. 3D-Printed Monolithic ZSM-5@nano-ZSM-5: Hierarchical Core-Shell Structured Catalysts for Enhanced Cracking of Polyethylene-Derived Pyrolysis Oils. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 79, 103890. [CrossRef]

- Rzepka, P.; Sheptyakov, D.; Wang, C.; van Bokhoven, J.A.; Paunović, V. How Micropore Topology Influences the Structure and Location of Coke in Zeolite Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 5593–5604. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Feng, X.; Lin, D.; Li, Y.; Shang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ma, Z.; et al. Regulating Framework Aluminum Location towards Boosted Light Olefins Generation in Ex-Situ Catalytic Pyrolysis of Low-Density Polyethylene. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149737. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lyu, W.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Xu, C.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, L. A Molecular Kinetic Model Incorporating Catalyst Acidity for Hydrocarbon Catalytic Cracking. AIChE J. 2023, 69, e18060. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, D.; He, H.; Zhao, L.; Gao, J.; Xu, C. Rational Tuning of Monomolecular, Bimolecular and Aromatization Pathways in the Catalytic Pyrolysis of Hexane on ZSM-5 from a First-Principles-Based Microkinetics Analysis. Fuel 2024, 366, 131368. [CrossRef]

- Ureel, Y.; Alexopoulos, K.; Van Geem, K.M.; Sabbe, M.K. Predicting the Effect of Framework and Hydrocarbon Structure on the Zeolite-Catalyzed Beta-Scission. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 7020–7036. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dengguo, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Xiong, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Oboirien, B.O.; Xu, G. CO2-Assisted Catalytic Pyrolysis of Polyolefins to Aromatics over Mesoporous HZSM-5 and Ga/ZSM-5 Catalysts. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 13137–13148. [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Akin, O.; Ureel, Y.; Yazdani, P.; Li, L.; Varghese, R.J.; Geem, K.M. Van Enhancing Catalytic Pyrolysis of Polypropylene Using Mesopore-Modified HZSM-5 Catalysts: Insights and Strategies for Improved Performance. Front. Chem. Eng. 2024, 6. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.A.; Sahasrabudhe, C.A.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Yappert, R.; Heyden, A.; Huang, W.; Sadow, A.D.; Peters, B. Population Balance Equations for Reactive Separation in Polymer Upcycling. Langmuir 2024, 40, 4096–4107. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Han, J.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Z.; Wang, K.; Fang, X.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Z. Combined Strategies Enable Highly Selective Light Olefins and Para-Xylene Production on Single Catalyst Bed. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 8086–8097. [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Yi, X.; Fang, W.; Wang, H.; Wei, H.; Xu, S.; et al. Coking-Resistant Polyethylene Upcycling Modulated by Zeolite Micropore Diffusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14269–14277. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschenbacher, A.; Varghese, R.J.; Delikonstantis, E.; Mynko, O.; Goodarzi, F.; Enemark-Rasmussen, K.; Oenema, J.; Abbas-Abadi, M.S.; Stefanidis, G.D.; Van Geem, K.M. Highly Selective Conversion of Mixed Polyolefins to Valuable Base Chemicals Using Phosphorus-Modified and Steam-Treated Mesoporous HZSM-5 Zeolite with Minimal Carbon Footprint. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 309, 121251. [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, A.; Wu, X.; Meirow, M.; Howell, D.; Willmon, J.; Yu, J.; Lamb, J. V.; Delferro, M.; Luijten, E.; Huang, W.; et al. Two Mesoporous Domains Are Better Than One for Catalytic Deconstruction of Polyolefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 17936–17944. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, Y.; Miyakage, T.; Anzai, A.; Huang, M.; Ait El Fakir, A.; Toyao, T.; Nakasaka, Y.; Phuekphong, A.; Ogawa, M.; Kolganov, A.A.; et al. Conversion of Polypropylene to Light Olefins by HMFI Catalysts below Pyrolytic Temperature: Catalytic, Spectroscopic, and Theoretical Studies. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 1678–1691. [CrossRef]

- Ashuiev, A.; Allouche, F.; Wili, N.; Searles, K.; Klose, D.; Copéret, C.; Jeschke, G. Molecular and Supported Ti(Iii)-Alkyls: Efficient Ethylene Polymerization Driven by the π-Character of Metal-Carbon Bonds and Back Donation from a Singly Occupied Molecular Orbital. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 780–792. [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, Y.; Shiono, T. Coordination Polymerization (Olefin and Diene). In Encyclopedia of Polymeric Nanomaterials; Kobayashi, S., Müllen, K., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2021; pp. 1–6 ISBN 978-3-642-36199-9.

- Tran, T. V; Do, L.H. Tunable Modalities in Polyolefin Synthesis via Coordination Insertion Catalysis. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 142, 110100. [CrossRef]

- Fushimi, M.; Damma, D. Exploring Ti Active Sites in Ziegler-Natta Catalysts through Realistic-Scale Computer Simulations with Universal Neural Network Potential. Mol. Catal. 2024, 565, 114414. [CrossRef]

- Young, M.J.; Ma, C.C.M.; Ting, C. Activation Energy and Transition State Determination of the Olefin Insertion Process of Metallocene Catalysts Using a Semiempirical Molecular Orbital Calculation. Russ. J. Coord. Chem. Khimiya 2002, 28, 25–31. [CrossRef]

- Ehm, C.; Budzelaar, P.H.M.; Busico, V. Calculating Accurate Barriers for Olefin Insertion and Related Reactions. J. Organomet. Chem. 2015, 775, 39–49. [CrossRef]

- Clementi, E.; Giunchi, G.; Introduction, I. Theoretical Study on a Reaction Pathway of Ziegler-Natta- Type Catalysis. 1978, 68.

- Ortega, D.E.; Matute, R.A.; Toro-Labbé, A. Exploring the Nature of the Energy Barriers on the Mechanism of the Zirconocene-Catalyzed Ethylene Polymerization: A Quantitative Study from Reaction Force Analysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 8198–8209. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Rempel, G.L. Ziegler-Natta Catalysts for Olefin Polymerization: Mechanistic Insights from Metallocene Systems. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1995, 20, 459–526. [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Kang, X.; Dai, S. Stable Ultrahighly Branched Polyethylene Synthesis via Externally Robust Chain-Walking Polymerization. ACS Catal. 2024, 13531–13541. [CrossRef]

- Ashuiev, A.; Humbert, M.; Gajan, D.; Norsic, S.; Searles, K.; Klose, D.; Lesage, A.; Pintacuda, G.; Ashuiev, A.; Humbert, M.; et al. Spectroscopic Signature and Structure of Active Centers in Ziegler-Natta Polymerization Catalysts Revealed by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance To Cite This Version : HAL Id : Hal-03017383 Spectroscopic Signature and Structure of Active Centers in Ziegler-N. 2020. [CrossRef]

- So, L.C.; Faucher, S.; Zhu, S. Synthesis of Low Molecular Weight Polyethylenes and Polyethylene Mimics with Controlled Chain Structures. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 1196–1234. [CrossRef]

- Kissin, Y. V Active Centers in Ziegler–Natta Catalysts: Formation Kinetics and Structure. J. Catal. 2012, 292, 188–200. [CrossRef]

- Shiga, A. Theoretical Study of Ethylene Polymerization on Ziegler–Natta Catalysts and on Metallocene Catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 1999, 146, 325–334. [CrossRef]

- Koltzenburg, S.; Maskos, M.; Nuyken, O. Coordination Polymerization. In Polymer Chemistry; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2023; pp. 295–324 ISBN 978-3-662-64929-9.

- Yu, Y.; Fu, Z.; Fan, Z. Chain Transfer Reactions of Propylene Polymerization Catalyzed by AlEt 3 Activated TiCl 4/MgCl 2 Catalyst under Very Low Monomer Addition Rate. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2012, 363–364, 134–139. [CrossRef]

- Margl, P.; Deng, L.; Ziegler, T. A Unified View of Ethylene Polymerization by D0 and D0f(n) Transition Metals. 3. Termination of the Growing Polymer Chain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 154–162. [CrossRef]

- Talarico, G.; Budzelaar, P.H.M. A Second Transition State for Chain Transfer to Monomer in Olefin Polymerization Promoted by Group 4 Metal Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 4524–4525. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, T.; Kashiwa, N.; Mizuno, A. Effect of Hydrogen on Propene Polymerization with Ethylenebis(1-indenyl)Zirconium Dichloride and Methylalumoxane Catalyst System. Die Makromol. Chemie, Rapid Commun. 1990, 11, 565–570. [CrossRef]

- Kissin, Y. V.; Rishina, L.A.; Vizen, E.I. Hydrogen Effects in Propylene Polymerization Reactions with Titanium-Based Ziegler-Natta Catalysts. II. Mechanism of the Chain-Transfer Reaction. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2002, 40, 1899–1911. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, W.; Khan, A.; Fu, Z.; Xu, J.; Fan, Z. Kinetics and Mechanism of Metallocene-Catalyzed Olefin Polymerization: Comparison of Ethylene, Propylene Homopolymerizations, and Their Copolymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2017, 55, 867–875. [CrossRef]

- Naweephattana, P.; Walaijai, K.; Rungnim, C.; Luanphaisarnnont, T.; Watthanaphanit, A.; Patthamasang, S.; Phiriyawirut, P.; Surawatanawong, P. The Role of Organoaluminum and Electron Donors in Propene Insertion on the Ziegler–Natta Catalyst. Dalt. Trans. 2024, 53, 11050–11059. [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, J.; Gupta, V.K.; Vanka, K. Effect of Donors on the Activation Mechanism in Ziegler-Natta Catalysis: A Computational Study. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 1809–1818. [CrossRef]

- Kissin, Y. V.; Liu, X.; Pollick, D.J.; Brungard, N.L.; Chang, M. Ziegler-Natta Catalysts for Propylene Polymerization: Chemistry of Reactions Leading to the Formation of Active Centers. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2008, 287, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Magni, E.; Somorjai, G.A. Ethylene and Propylene Polymerization Catalyzed by a Model Ziegler-Natta Catalyst Prepared by Gas Phase Deposition of Magnesium Chloride and Titanium Chloride Thin Films. Catal. Letters 1995, 35, 205–214. [CrossRef]

- Fushimi, M.; Damma, D. The Role of External Donors in Ziegler-Natta Catalysts through Nudged Elastic Band Simulations on Realistic-Scale Models Employing a Universal Neural Network Potential. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 6646–6657. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Feng, H.; Liu, H.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, D. Effect of Dioldibenzoate Isomers as Electron Donors on the Performances of Ziegler–Natta Polypropylene Catalysts: Experiments and Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 2294–2302. [CrossRef]

- Tritto, I.; Sacchi, M.C.; Locatelli, P. Ziegler-Natta Polymerization of Propene: Cooperative Effects of Titanium Ligands on the Steric Control of the First Addition of Monomer. Die Makromol. Chemie 1986, 187, 2145–2151. [CrossRef]

- Resconi, L.; Piemontesi, F.; Franciscono, G.; Abis, L.; Fiorani, T. Olefin Polymerization at Bis(Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)Zirconium and -Hafnium Centers: Chain-Transfer Mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 1025–1032. [CrossRef]

- Ewen, J.A.; Elder, M.J.; Jones, R.L.; Haspeslagh, L.; Atwood, J.L.; Bott, S.G.; Robinson, K. Metallocene/Polypropylene Structural Relationships: Implications on Polymerization and Stereochemical Control Mechanisms. Makromol. Chemie. Macromol. Symp. 1991, 48–49, 253–295. [CrossRef]

- Busico, V.; Cipullo, R.; Pellecchia, R.; Ronca, S.; Roviello, G.; Talarico, G. Design of Stereoselective Ziegler-Natta Propene Polymerization Catalysts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 15321–15326. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busico, V.; Cipullo, R.; Ronca, S.; Budzelaar, P.H.M. Mimicking Ziegler-Natta Catalysts in Homogeneous Phase, 1: C2-Symmetric Octahedral Zr(IV) Complexes with Tetradentate [ONNO]-Type Ligands. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2001, 22, 1405–1410. [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.; Therukauff, G.; Vantomme, A.; Welle, A.; Haspeslagh, L.; Brusson, J.M.; Maron, L.; Carpentier, J.F.; Kirillov, E. A Theoretical Outlook on the Stereoselectivity Origins of Isoselective Zirconocene Propylene Polymerization Catalysts. Chem. - A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10784–10792. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, J.C.; Heere, J.J.R.; Sudmeijer, O. Factors Influencing Chain Transfer with Monomer and with Hydrogen in Propene Polymerization Using MgCl2-Supported Ziegler-Natta Catalysts. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2000, 201, 1846–1852. [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, L.; Guerra, G.; Corradini, P. Mechanisms of Propagation and Termination Reactions in Classical Heterogeneous Ziegler-Natta Catalytic Systems: A Nonlocal Density Functional Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 2428–2436. [CrossRef]

- Santoro, O.; Piola, L.; Mc Cabe, K.; Lhost, O.; Den Dauw, K.; Vantomme, A.; Welle, A.; Maron, L.; Carpentier, J.F.; Kirillov, E. Long-Chain Branched Polyethylene via Coordinative Tandem Insertion and Chain-Transfer Polymerization Using Rac-{EBTHI}ZrCl2/MAO/Al-Alkenyl Combinations: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 8847–8857. [CrossRef]

- Sifri, R.J.; Padilla-Vélez, O.; Coates, G.W.; Fors, B.P. Controlling the Shape of Molecular Weight Distributions in Coordination Polymerization and Its Impact on Physical Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 1443–1448. [CrossRef]

- Becker, P.; Buback, M.; Sandmann, J. Initiator Efficiency of Peroxides in High-Pressure Ethene Polymerization. 2002, 2113–2123.

- Davis, T.P. HANDBOOK OF RADICAL; ISBN 047139274X.

- Goller, A.; Obenauf, J.; Kretschmer, W.P.; Kempe, R. The Highly Controlled and Efficient Polymerization of Ethylene. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2023, 62. [CrossRef]

- Scorah, M.J.; Cosentino, R.; Dhib, R.; Penlidis, A. Experimental Study of a Tetrafunctional Peroxide Initiator: Bulk Free Radical Polymerization of Butyl Acrylate and Vinyl Acetate. Polym. Bull. 2006, 57, 157–167. [CrossRef]

- Koptelov, A.A.; Milekhin, Y.M.; Baranets, Y.N. Simulation of Thermal Decomposition of a Polymer at Random Scissions of C – C Bonds. 2012, 6, 626–633. [CrossRef]

- Poutsma, M.L. Reexamination of the Pyrolysis of Polyethylene : Data Needs , Free-Radical Mechanistic Considerations , and Thermochemical Kinetic Simulation of Initial Product-Forming Pathways. 2003, 8931–8957.

- Yeiser, T.M.; Kline, G.M.; Arnett, R.L.; Stacy, C.J. Kinetics of the Thermal Degradation of Linear Polyethylene Complete Description of Thermal Degradation Would. 1966.

- Ding, W.; Liang, J.; Anderson, L.L. Thermal and Catalytic Degradation of High Density Polyethylene and Commingled Post-Consumer Plastic Waste. 1997, 3820.

- Holmstrom, A.; Sorvik, E.M. NITROGEN ATMOSPHERE OF LOW OXYGEN CONTENT . TYPES OF HIGH-DENSITY POLYETHYLENE. 1976, 53, 33–53.

- Lee, E.J.; Park, H.J.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, K.Y. Effect of Azo and Peroxide Initiators on a Kinetic Study of Methyl Methacrylate Free Radical Polymerization by DSC. Macromol. Res. 2018, 26, 322–331. [CrossRef]

- Pielichowski, K.; Njuguna, J.; Majka, T. Thermal Degradation of Polymers, Copolymers, and Blends. In; 2023; pp. 49–147 ISBN 9780128230237.

- Natta, G. Olefin Polymerization with Ziegler-Natta Catalyst. 1963, 1–6.

- Barta, J. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Applications of Azo Initiators. 2016, 5133–5145. [CrossRef]

- Scorah, M.J.; Dhib, R.; Penlidis, A. Use of a Novel Tetrafunctional Initiator in the Free Radical Homo- and Copolymerization of Styrene, Methyl Methacylate and α-Methyl Styrene. J. Macromol. Sci. - Pure Appl. Chem. 2005, 42 A, 403–426. [CrossRef]

- Luft, G.; Bitsch, H.; Seidl, H. Effectiveness of Organic Peroxide Initiators in the High-Pressure Polymerization of Ethylene. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A - Chem. 1977, 11, 1089–1112. [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.N. Initiators, Free-Radical. 2001, In Kirk-Ot. [CrossRef]

- Khubi-Arani, Z.; Salami-Kalajahi, M.; Najafi, M.; Roghani-Mamaqani, H.; Haddadi-Asl, V.; Ghafelebashi-Zarand, S.M. Simulation of Styrene Free Radical Polymerization over Bi-Functional Initiators Using Monte Carlo Simulation Method and Comparison with Mono-Functional Initiators. Polym. Sci. - Ser. B 2010, 52, 184–192. [CrossRef]

- Machi, S.; Kise, S.; Hagiwara, M.; Kagiya, T. Mechanisms of Propagation, Transfer, and Short-chain Branching Reactions in the Free-radical Polymerization of Ethylene. J. Polym. Sci. Part A-1 Polym. Chem. 1967, 5, 3115–3128. [CrossRef]

- Izgorodina, E.I.; Coote, M.L. Accurate Ab Initio Prediction of Propagation Rate Coefficients in Free-Radical Polymerization : Acrylonitrile and Vinyl Chloride. 2006, 324, 96–110. [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, A.; Clochard, M.C.; Coqueret, X.; Dispenza, C.; Driscoll, M.S.; Ulański, P.; Al-Sheikhly, M. Polymerization Reactions and Modifications of Polymers by Ionizing Radiation. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12, 1–67. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.A.; Sharma, N. Free Radical Polymerizations: LDPE and EVA ; 2023; ISBN 9783527843831.

- Mavroudakis, E.; Cuccato, D.; Moscatelli, D. Quantum Mechanical Investigation on Bimolecular Hydrogen Abstractions in Butyl Acrylate-Based Free Radical Polymerization Processes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 1799–1806. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, I.; Ewart, S.; Brown, H.; Eddy, C.; Mendenhall, J.; Munjal, S. Accurate Density Functional Theory (DFT) Protocol for Screening and Designing Chain Transfer and Branching Agents for LDPE Systems. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2018, 3, 228–242. [CrossRef]

- Beuermann, S.; Buback, M. Free-Radical Polymerization Under High Pressure. In High Pressure Molecular Science; Winter, R., Jonas, J., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1999; pp. 331–367 ISBN 978-94-011-4669-2.

- Seif, A.; Domingo, L.R.; Ahmadi, T.S. Calculation of the Rate Constants for Hydrogen Abstraction Reactions by Hydroperoxyl Radical from Methanol, and the Investigation of Stability of CH3OH.HO2 Complex. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2020, 1190, 113010. [CrossRef]

- Chabira, S.F.; Sebaa, M.; G’sell, C. Oxidation and Crosslinking Processes during Thermal Aging of Low-Density Polyethylene Films. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 124, 5200–5208. [CrossRef]

- Iedema, P.; Wulkow, M.; Hoefsloot, H. Modeling Molecular Weight and Degree of Branching Distribution of Low-Density Polyethylene. Macromolecules 2000, 33. [CrossRef]

- Odian, G. Radical Chain Polymerization. In Principles of Polymerization; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2004; pp. 198–349 ISBN 9780471478751.

- Barner-Kowollik, C.; Russell, G.T. Chain-Length-Dependent Termination in Radical Polymerization: Subtle Revolution in Tackling a Long-Standing Challenge. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2009, 34, 1211–1259. [CrossRef]

- de Kock, J.B.L. Chain-Length Dependent Bimolecular Termination in Free-Radical Polymerization : Theory, Validation and Experimental Application of Novel Model-Independent Methods; 1999; ISBN 90-386-2701-7.

- Alghamdi, M.M.; Russell, G.T. On the Activation Energy of Termination in Radical Polymerization , as Studied at Low Conversion. 2024.

- Barner-kowollik, C.; Buback, M.; Egorov, M.; Fukuda, T.; Goto, A.; Friedrich, O.; Russell, G.T.; Vana, P.; Yamada, B.; Zetterlund, P.B. Critically Evaluated Termination Rate Coefficients for Free-Radical Polymerization : Experimental Methods. 2005, 30, 605–643. [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, A.N.; Hutchinson, R.A. Determination of the Mode of Free Radical Termination from Pulsed Laser Polymerization Experiments. 2007, 29–42. [CrossRef]

- Cauter, K. Van; Speybroeck, V. Van; Waroquier, M. Ab Initio Study of Poly ( Vinyl Chloride ) Propagation Kinetics : Head-to-Head versus Head-to-Tail Additions. 2007, 541–552. [CrossRef]

- Cuccato, D.; Dossi, M.; Moscatelli, D.; Storti, G. A Density Functional Theory Study of Poly ( Vinyl Chloride ) ( PVC ) Free Radical Polymerization. 2011, 100–109. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Ali, Y.; Saad, H.; Amur, I. Kinetics and Mechanism of Bulk Polymerization of Vinyl Chloride in a Polymerization Reactor. J. Eng. Res. 2015, 12, 41–50. [CrossRef]

- De Roo, T.; Wieme, J.; Heynderickx, G.J.; Marin, G.B. Estimation of Intrinsic Rate Coefficients in Vinyl Chloride Suspension Polymerization. Polymer (Guildf). 2005, 46, 8340–8354. [CrossRef]

- Abreu, C.M.R.; Fonseca, A.C.; Rocha, N.M.P.; Guthrie, J.T.; Serra, A.C.; Coelho, J.F.J. Poly(Vinyl Chloride): Current Status and Future Perspectives via Reversible Deactivation Radical Polymerization Methods. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2018, 87, 34–69. [CrossRef]

- Bárkányi, Á.; Németh, S.; Lakatos, B.G. Modelling and Simulation of Suspension Polymerization of Vinyl Chloride via Population Balance Model. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2013, 59, 211–218. [CrossRef]

- Cuccato, D.; Dossi, M.; Moscatelli, D.; Storti, G. Quantum Chemical Investigation of Secondary Reactions in Poly ( Vinyl Chloride ) Free-Radical Polymerization. 2012, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Дeдoв, A. Modeling the Kinetics of the Extraction of Vinyl Chloride from Polyvinyl Chloride. Fibre Chem. 2012, 44. [CrossRef]

- Starnes, W.H. MECHANISM AND MICROSTRUCTURE IN THE FREE-RADICAL POLYHERIZATION OF VINYL CHLORIDE: HEAD-TO-HEAD ADDITION REVISITED 1 W. H. Starnes, Jr.,. B. 1993, 11, 1–11.

- Wieme, J.; Marin, G.B. Microkinetic Modeling of Structural Properties of Poly ( Vinyl Chloride ). 2009, 7797–7810. [CrossRef]

- Percec, V.; Popov, A. V; Ramirez-Castillo, E.; Weichold, O. Living Radical Polymerization of Vinyl Chloride Initiated with Iodoform and Catalyzed by Nascent Cu0/Tris(2-aminoethyl)Amine or Polyethyleneimine in Water at 25 °C Proceeds by a New Competing Pathways Mechanism. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2003, 41, 3283–3299. [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, K.F.D.; Agostini, M.; Bruinsma, M.; Vorenkamp, E.J.; Schouten, A.J.; Coote, M.L. Experimental and Theoretical Evaluation of the Reactions Leading to Formation of Internal Double Bonds in Suspension PVC. 2008, 5527–5539.

- Purmova, J.; Pauwels, K.F.D.; Zoelen, W. Van; Vorenkamp, E.J.; Schouten, A.J.; Coote, M.L. New Insight into the Formation of Structural Defects in Poly ( Vinyl Chloride ). 2005, 6352–6366.

- Heuts, J.P.A.; Heuts, J.P.A.; Sudarko; Gilbert, R.G. First-principles Prediction and Interpretation of Propagation and Transfer Rate Coefficients. Macromol. Symp. 1996, 111, 147–157. [CrossRef]

- Buback, M.; Egorov, M.; Gilbert, R.G.; Kaminsky, V.; Olaj, O.F.; Russell, G.T.; Vana, P.; Zifferer, G. Critically Evaluated Termination Rate Coefficients for Free-Radical Polymerization , 1 The Current Situation. 2002, 2570–2582.

- Phillips, E.O.; Pino, P.; Mazzanti, J.; Anderson, A.W.; Ashby, C.E.; Ford, B.M.; Jeselson, M.; Tsvetkova, V.I.; Chirkov, N.M.; Sendel, E.B.; et al. THE MECHANISM OF CHAIN TERMINATION IN THE FREE-RADICAL POLYMERIZATION OF VINYL CHLORIDE BY 14C-LABELLED INITIATORS *. 1961, 1020–1025.

- Buback, M.; Russell, G.T. Detailed Analysis of Termination Kinetics in Radical Polymerization. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yamin, N.; Tosaka, M.; Yamago, S. Elucidation of the Termination Mechanism of the Radical Polymerization of Isoprene. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Moad, G.; Solomon, D.H. 5 - Termination. In The Chemistry of Radical Polymerization (Second Edition); Moad, G., Solomon, D.H., Eds.; Elsevier Science Ltd: Amsterdam, 2005; pp. 233–278 ISBN 978-0-08-044288-4.

- Dubikhin, V. V; Knerel’man, E.I.; Nazin, G.M.; Prokudin, V.G.; Stashina, G.A.; Shastin, A. V; Shunina, I.G. Solvent and External Pressure Effects on the Ratio of the Cyanoisopropyl Radical Recombination and Disproportionation Rates. Kinet. Catal. 2013, 54, 404–407. [CrossRef]

- Starnes, W. Structural Defects in Poly(Vinyl Chloride) and the Mechanism of Vinyl Chloride Polymerization: Comments on Recent Studies. Procedia Chem. 2012, 4, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Seifali, M.; Abadi, A. The Effect of Process and Structural Parameters on the Stability , Thermo - Mechanical and Thermal Degradation of Polymers with Hydrocarbon Skeleton Containing PE , PP , PS , PVC , NR , PBR and SBR. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Natesakhawat, S.; Weidman, J.; Garcia, S.; Means, N.C.; Wang, P. Pyrolysis of High-Density Polyethylene: Degradation Behaviors, Kinetics, and Product Characteristics. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 116, 101738. [CrossRef]

- N.A. Slovokhotova, M.A. Magrupov, V.A.K. Thermal Degradation of Polyethylene. 1979, 1974–1979.

- Holmstrom, A. Thermal Degradation of Polyethylene in a Nitrogen Atmosphere of Low Oxygen Content . 11 . Structural Changes Occurring in Low-Density Polyethylene at an Oxygen Content. 1974, 18, 761–778. [CrossRef]

- Kuzema, P.O.; Bolbukh, Y.M.; Tertykh, V.A.; Laguta, I. V. Vacuum Thermal Decomposition of Polyethylene Containing Antioxidant and Hydrophilic/Hydrophobic Silica. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2015, 121, 1167–1180. [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiyat, Y.; Sumit, K. Thermal Decomposition Products of Polyethylene *. 1968, 6, 415–424.

- Gracida-alvarez, U.R.; Mitchell, M.K.; Sacramento-rivero, J.C.; Shonnard, D.R. Effect of Temperature and Vapor Residence Time on the Micropyrolysis Products of Waste High Density Polyethylene. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.; Schoors, L. Van; Benzarti, K.; Colin, X.; Cruz, M.; Schoors, L. Van; Benzarti, K.; Thermo-oxidative, X.C. Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of Additive Free Polyethylene . Part I . Analysis of Chemical Modifications at Molecular and Macromolecular Scales To Cite This Version : HAL Id : Hal-02291131. 2019.

- Rychlý, J.; Rychlá, L. Polyolefins: From Thermal and Oxidative Degradation to Ignition and Burning. In; Springer, Cham, 2016; pp. 285–314.

- Andersson, T.; Stålbom, B.; Wesslén, B. Degradation of Polyethylene during Extrusion. II. Degradation of Low-Density Polyethylene, Linear Low-Density Polyethylene, and High-Density Polyethylene in Film Extrusion. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 91, 1525–1537. [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, A.; Gaan, S.; Price, D.; Horrocks, A.R. Thermal Decomposition of Flame Retardant Polymers. In; Informa, 2024; pp. 11–35.

- Chen, X.; Zhuo, J.; Jiao, C. Thermal Degradation Characteristics of Fl Ame Retardant Polylactide Using TG-IR. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 2143–2147. [CrossRef]

- Vesely, D.; Castro-Diaz, L. Diffusion Controlled Oxidative Degradation of Un-Stabilised Polyethylene. 2016, 4, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Harlin, A.L.I.; Heino, E. Comparison of Rheological Properties of Cross-Linked and Thermal-Mech Anically Degraded HDPE. 1995, 479–486.

- Sa, T.; Allen, N.S.; Liauw, C.M.; Johnson, B. Effects of Type of Polymerization Catalyst System on the Degradation of Polyethylenes in the Melt State Part 1 : Unstabilized Polyethylenes ( Including Metallocene Types ). [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, L.A.; Chinelatto, M.A.; Canevarolo, S. V The Role of Chain Scission and Chain Branching in High Density Polyethylene during Thermo-Mechanical Degradation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2004, 86, 445–453. [CrossRef]

- del Teso Sánchez, K.; Allen, N.S.; Liauw, C.M.; Johnson, B. Effects of Type of Polymerization Catalyst System on the Degradation of Polyethylenes in the Melt State. Part 1: Unstabilized Polyethylenes (Including Metallocene Types). J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2011, 17, 28–39. [CrossRef]

- Rideal, G.R.; Padget, J.. C. The Thermal-Mechanical Degradation of High Density Polyethylene. J. polym. sci., C Polym. symp 1976, 15, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, D.; Kumar, P.; Mathur, G.N. Aging Characteristics of Ternary Blends of Polyethylenes. I. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2001, 16, 419–425. [CrossRef]

- Dickens, B. Thermally Degrading Polyethylene Studied by Means of Factor- Jump Thermogravimetry. 1982, 20, 1065–1087.

- Popov, K. V; Knyazev, V.D. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of C − C Bond Scission in Polyethylene and Linear Alkanes : E Ff Ects of the Condensed Phase. 2014.

- Peterson, J.D.; Vyazovkin, S.; Wight, C.A. Kinetics of the Thermal and Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of Polystyrene, Polyethylene and Poly(Propylene). Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2001, 202, 775–784. [CrossRef]

- Smagala, T.G.; McCoy, B.J. Mechanisms and Approximations in Macromolecular Reactions: Reversible Initiation, Chain Scission, and Hydrogen Abstraction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 2461–2469. [CrossRef]

- Kiran, E.; Gillham, J.K. Pyrolysis-Molecular Weight Chromatography: A New on-Line System for Analysis of Polymers. II. Thermal Decomposition of Polyolefins: Polyethylene, Polypropylene, Polyisobutylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1976, 20, 2045–2068. [CrossRef]

- Seeger, M.; Cantow, H.-J. Theory of Thermal Decomposition and Volatilization of Normal Alkanes and Linear Polyethylene. Polym. Bull. 1979, 1, 347–354. [CrossRef]

- David A. Anderson, E.S.; Freeman The Kinetics o f the Thermal Degradation of Polystyrene and Polyethylene. 1961, 253–260.

- Jellinek, H.H.G. Thermal Degradation of Polystyrene and Polyethylene. Part III. J. Polym. Sci 1949, 4, 13–36. [CrossRef]

- Sawaguchi, T.; Ikemura, T.; Seno, M. Thermal Degradation of Polymers in the Melt, 2. Kinetic Approach to the Formation of Volatile Oligomers by Thermal Degradation of Polyisobutylene. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 1996, 197, 215–222. [CrossRef]

- Wedlake, M.D.; Kohl, P.A. Thermal Decomposition Kinetics of Functionalized Polynorbornene. J. Mater. Res. 2002, 17, 632–640. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.S.; Kumar, V.R.; Madras, G. Continuous Distribution Kinetics for the Thermal Degradation of LDPE in Solution. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002, 84, 681–690. [CrossRef]

- Pielichowski, K.; Njuguna, J.; Majka, T. Mechanisms of Thermal Degradation of Polymers. In; 2023; pp. 9–11 ISBN 9780128230237.

- Madorsky, S.L. Rates of Thermal Degradation of Polystyrene and Polyethylene in a Vacuum. J. Polym. Sci. 1952, 9, 133–156. [CrossRef]

- Kruse, T.M.; Woo, O.S.; Wong, H.; Khan, S.S.; Broadbelt, L.J. Mechanistic Modeling of Polymer Degradation : A Comprehensive Study of Polystyrene. 2002, 7830–7844.

- Sohma, J. Radical Migration as an Elementary Process in Degradation. 1983, 55, 1595–1601. [CrossRef]

- Timpe, H.-J.; Kronfeld, K.-P. Kinetic Treatment of Termination Processes at Radical Polymerizations. Acta Polym. 1991, 42, 415–419. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.K. Fundamental Aspects of the Radiolysis of Solid Polymers: Crosslinking and Degradation. ChemInform 2009, 40. [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.; Bracco, P. Mechanisms of Cross-Linking, Oxidative Degradation, and Stabilization of UHMWPE. In; Elsevier BV, 2016; pp. 467–487.

- Davis, T.E.; Tobias, R.L.; Peterli, E.B. Thermal Degradation of Polypropylene. J. Polym. Sci. 1962, 56, 485–499. [CrossRef]

- Dickens, B. Thermal Degradation Study of Isotactic Polypropylene Using Factor-Jump Thermogravimetry. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 1982, 20, 1169–1183. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Ohkawa, T.; Suzuki, M.; Tsuchiya, T.; Takeda, K. Semiquantitative Analysis of the Thermal Degradation of Polypropylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 88, 1465–1472. [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, Y.; Sumi, K. Thermal Decomposition Products of Polypropylene. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 1969, 7, 1599–1607. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Madras, G. Thermal Degradation Kinetics of Isotactic and Atactic Polypropylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90, 2206–2213. [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Igarashi, T.; Nitta, K. Thermal Degradation Behavior of Polypropylene in the Melt State : Molecular Weight Distribution Changes and Chain Scission Mechanism. 2011, 1661–1670. [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, N.; Mastalski, I.; Zolghadr, A.; Patel, B.; Uppili, S.; Go, T.; Maduskar, S.; Wang, Z.; Neurock, M.; Dauenhauer, P.J. On the Intrinsic Reaction Kinetics of Polypropylene Pyrolysis. Matter 2023, 6, 3413–3433. [CrossRef]

- Bresler, S.E.; Os’minskaia, A.T.; Popov, A.G. The Thermal Degradation of Stereoregular Polypropylene. Polym. Sci. U.s.s.r. 1961, 2, 224–227. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Sun, Q.; Hua, F.; Yang, S.; Ji, Y.; Cheng, Y. A Molecular-Level Kinetic Model for the Primary and Secondary Reactions of Polypropylene Pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 175, 106182. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, B. Effect of Diatomite on the Thermal Degradation Behavior of Polypropylene and Formation of Graphene Products. 2022.

- Rätzsch, M.; Arnold, M.; Borsig, E.; Bucka, H.; Reichelt, N. Radical Reactions on Polypropylene in the Solid State. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2002, 27, 1195–1282. [CrossRef]

- Sawaguchi, T.; Seno, M. On the Stereoisomerization in Thermal Degradation of Isotactic Poly(Propylene). Macromol. Chem. Phys. 1996, 197, 3995–4015. [CrossRef]

- Straznicky, J.I.; Iedema, P.D.; Remerie, K.; Mcauley, K.B. A Deterministic Model to Predict Tacticity Changes During Controlled Degradation of Polypropylene. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 293, 120064. [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, P.-M.; Zhu, N.; Zhu, X.; Yan, D. In Situ Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Study of the Thermal Degradation of Isotactic Poly(Propylene). Appl. Spectrosc. 2005, 59, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S. Revising the Mechanism of Polyolefin, Degradation and Stabilisation: Insights from Chemiluminescence, Volatiles and Extractables. Manchester Metrop. Univ. 2019.

- Shibryaeva, L. Thermal Oxidation of Polypropylene and Modified Polypropylene - Structure Effects. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Yoshiga, A.; Otaguro, H.; Parra, D.F.; Lima, L.F.C.P.; Lugão, A.B. Controlled Degradation and Crosslinking of Polypropylene Induced by Gamma Radiation and Acetylene. Polym. Bull. 2009, 63, 397–409. [CrossRef]

- Troitskii, B.B.; Troitskaya, L.S.; Myakov, V.N.; Lepaev, A.F. Mechanism of the Thermal Degradation of Poly(Vinyl Chloride). J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Symp. 2007, 42, 1347–1361. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Liu, J.; Luo, Z.; Wang, H.; Wei, Z. Construction of Chain Segment Structure Models, and Effects on the Initial Stage of the Thermal Degradation of Poly(Vinyl Chloride). RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 37268–37275. [CrossRef]

- Abbås, K.B.; Sörvik, E.M. On the Thermal Degradation of Poly(Vinyl Chloride). IV. Initiation Sites of Dehydrochlorination. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1976, 20, 2395–2406. [CrossRef]

- Lukáš, R.; Přádová, O. Thermal Dehydrochlorination of Poly(Vinyl Chloride), 2. Transiently and Permanently Acting Structural Defects. Die Makromol. Chemie 1986, 187, 2111–2122. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Peng, X. Theoretical Study on the Thermal Dehydrochlorination of Model Compounds for Poly(Vinyl Chloride). J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 2009, 896, 34–37. [CrossRef]

- Bacaloglu, R.; Fisch, M.H. Reaction Mechanism of Poly(Vinyl Chloride) Degradation. Molecular Orbital Calculations. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 1995, 1, 241–249. [CrossRef]

- Rogestedt, M.; Hjertberg, T. Structure and Degradation of Commercial Poly(Vinyl Chloride) Obtained at Different Temperatures. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Troitskii, B.B.; Troitskaya, L.S. Some Aspects of TheThermal Degradation of Poly(Vinyl Chloride). Int. J. Polym. Mater. 1998, 41, 285–324. [CrossRef]

- Hujuri, U.; Ghoshal, A.K.; Gumma, S. Temperature-Dependent Pyrolytic Product Evolution Profile for Polypropylene. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Fisch, M.H.; Bacaloglu, R. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Thermal Degradation of Poly(Vinyl Chloride). J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 1995, 1, 233–240. [CrossRef]

- Krongauz, V. V Kinetics of Plasticized Poly(Vinyl Chloride) Thermal Degradation, Induction, Autocatalysis, Glass Transition, Diffusion. Chemistryselect 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Yanborisov, V.M.; Borisevich, S.S. Quantum-Chemical Modeling of the Mechanism of Autocatalytic Dehydrochlorination of PVC. Theor. Exp. Chem. 2005, 41, 352–358. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.; Basu, S.; Palit, S.K.; Maiti, M.M. A Reexamination of the Degradation of Polyvinylchloride by Thermal Analysis. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 1994, 32, 1225–1236. [CrossRef]

- Yanborisov, V.; Borisevich, S. Mechanism of Initiation and Growth of Polyene Sequences during Thermal Degradation of Poly(Vinyl Chloride). Polym. Sci. - Ser. A 2005, 47, 844–854.

- Bettens, T.; Eeckhoudt, J.; Hoffmann, M.; Alonso, M.; Geerlings, P.; Dreuw, A.; Proft, F. Designing Force Probes Based on Reversible 6π-Electrocyclizations in Polyenes Using Quantum Chemical Calculations. J. Org. Chem. 2021, XXXX. [CrossRef]

- Starnes, W.H.; Ge, X. Mechanism of Autocatalysis in the Thermal Dehydrochlorination of Poly(Vinyl Chloride). Macromolecules 2004, 37, 352–359. [CrossRef]

- TÜDŐS, F.; KELEN, T. INVESTIGATION OF THE KINETICS AND MECHANISM OF PVC DEGRADATION. In Macromolecular Chemistry–8; SAARELA, K., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann, 1973; pp. 393–412 ISBN 978-0-408-70516-5.

- Ye, L.; Li, T.; Hong, L. Understanding Enhanced Char Formation in the Thermal Decomposition of PVC Resin: Role of Intermolecular Chlorine Loss. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 26, 102186. [CrossRef]

- Lattimer, R.P.; Kroenke, W.J. 15 - STUDIES OF VOLATILE PYROLYZATE, SMOKE, AND CHAR FORMATION IN POLY(VINYL CHLORIDE). In Analytical Pyrolysis; Voorhees, K.J., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann, 1984; pp. 453–473 ISBN 978-0-408-01417-5.

- Brauman, S.K. Char Formation in Polyvinyl Chloride. III. Mechanistic Aspects of Isothermal Degradation of PVC Containing Some Dehydrochlorination/Charring Agents. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1981, 26, 353–371. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, T.; Iván, B.; Turcsányi, B.; Kelen, T.; Tüdös, F. Crosslinking, Scission and Benzene Formation during PVC Degradation under Various Conditions. Polym. Bull. 1980, 3, 613–620. [CrossRef]

- Kelen, T. Secondary Processes of Thermal Degradation of PVC. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A 1978, 12, 349–360. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.P.; Pierre, L.E. St. Thermal Degradation of Poly(Vinyl Chloride). II. Degradation Mechanism Based on Decomposition Energetics. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 1973, 11, 1841–1850. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Fonseca, I.M.; Matos, I.; Marques, M.M.; Botelho do Rego, A.M.; Lemos, M.A.N.D.A.; Lemos, F. Catalytic Degradation of Low and High Density Polyethylenes Using Ethylene Polymerization Catalysts: Kinetic Studies Using Simultaneous TG/DSC Analysis. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 374, 170–179. [CrossRef]

- Artetxe, M.; Lopez, G.; Amutio, M.; Elordi, G.; Bilbao, J.; Olazar, M. Cracking of High Density Polyethylene Pyrolysis Waxes on HZSM-5 Catalysts of Different Acidity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 10637–10645. [CrossRef]

- Marcilla, A.; Beltrán, M.I.; Navarro, R. Thermal and Catalytic Pyrolysis of Polyethylene over HZSM5 and HUSY Zeolites in a Batch Reactor under Dynamic Conditions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 86, 78–86. [CrossRef]

- van de Minkelis, J.H.; Hergesell, A.H.; van der Waal, J.C.; Altink, R.M.; Vollmer, I.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Polyethylene with Microporous and Mesoporous Materials: Assessing Performance and Mechanistic Understanding. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202401141. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.W.; Park, Y.-K. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Polyethylene and Polypropylene over Desilicated Beta and Al-MSU-F. Catalysts 2018, 8, 501. [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.A.H.S.; Dehaghani, A.H.S. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Plastic Waste to Gasoline, Jet Fuel and Diesel with Nano MOF Derived-Loaded Y Zeolite: Evaluation of Temperature, Zeolite Crystallization and Catalyst Loading Effects. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 299, 117825. [CrossRef]

- Psarreas, A.; Tzoganakis, C.; McManus, N.T.; Penlidis, A. Nitroxide-Mediated Controlled Degradation of Polypropylene. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2007, 47, 2118–2123. [CrossRef]

- Kharitontsev, V.; Tissen, E.; Matveenko, E.; Mikhailov, Y.; Tretyakov, N.; Zagoruiko, A.; Elyshev, A. Estimating the Efficiency of Catalysts for Catalytic Pyrolysis of Polyethylene. Katal. v promyshlennosti 2023, 23, 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Manos, G.; Garforth, A.; Dwyer, J. Catalytic Degradation of High-Density Polyethylene on an Ultrastable-Y Zeolite. Nature of Initial Polymer Reactions, Pattern of Formation of Gas and Liquid Products, and Temperature Effects. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2000, 39, 1203–1208. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Costa, L.; Marques, M.D.M.; Fonseca, I.; Lemos, M.A.; Lemos, F. Using Simultaneous DSC/TG to Analyze the Kinetics of Polyethylene Degradation-Catalytic Cracking Using HY and HZSM-5 Zeolites. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2010, 99, 5–15. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, S.R.; Minsker, K.S.; Zaikov, G.E. Catalytic Degradation of Polyolefins. Oxid. Commun. 2002, 25, 325–349. [CrossRef]

- Marcilla, A.; Beltrán, M.I.; Navarro, R. Evolution of Products during the Degradation of Polyethylene in a Batch Reactor. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2009, 86, 14–21. [CrossRef]

- Marcilla, A.; Beltrán, M.I.; Navarro, R. Evolution with the Temperature of the Compounds Obtained in the Catalytic Pyrolysis of Polyethylene over HUSY. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 6896–6903. [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, K.; Pinto, J.; Pacheco, H. Assessment of Performance and Deactivation Resistance of Catalysts in the Pyrolysis of Polyethylene and Post-Consumer Polyolefin Waste. Macromol. React. Eng. 2024, 18. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Peng, P.; Guo, H.; Song, H.; Li, Z. The Catalytic Pyrolysis of Waste Polyolefins by Zeolite-Based Catalysts: A Critical Review on the Structure-Acidity Synergies of Catalysts. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 222, 110712. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F.; Costa, P.; Gulyurtlu, I.; Cabrita, I. Pyrolysis of Plastic Wastes. 2. Effect of Catalyst on Product Yield. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1999, 51, 57–71. [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Vedachalam, S.; Dalai, A.K.; Saxena, S.; Dally, B.; Roberts, W.L. Review on Production of Liquid Fuel from Plastic Wastes through Thermal and Catalytic Degradation. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 114, 101661. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, G.; Hu, W.; Niu, B.; Long, D.; Zhang, Y. Highly Selective Upgrading of Polyethylene into Light Aromatics via a Low-Temperature Melting-Catalysis Strategy. ACS Catal. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hesse, N.D.; Lin, R.; Bonnet, E.; Cooper, J.; White, R.L. In Situ Analysis of Volatiles Obtained from the Catalytic Cracking of Polyethylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 82, 3118–3125. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, W.; Zheng, J.; Du, Y.; Wang, Q.; Hedin, N.; Qin, B.; Li, R. Selective and Controllable Cracking of Polyethylene Waste by Beta Zeolites with Different Mesoporosity and Crystallinity. Adv. Sci. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Marcilla, A.; Beltrán, M.I.; Navarro, R. Study of the Deactivation Process of HZSM5 Zeolite during Polyethylene Pyrolysis. Appl. Catal. A-general 2007, 333, 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, S.; Zhang, H. Efficient Pyrolysis of Low-Density Polyethylene for Regulatable Oil and Gas Products by ZSM-5, HY and MCM-41 Catalysts. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Sung, S.; Lee, Y.; Gu, S.; Choi, J.W.; Yoo, C.J.; Suh, D.J.; Choi, J.; Ha, J.M. Chemical Upcycling of PVC-Containing Plastic Wastes by Thermal Degradation and Catalysis in a Chlorine-Rich Environment. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 342, 123074. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.Z.; Ortega, M.; Miller, S.A.; Hullfish, C.W.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Hu, W.; Hu, J.; Lercher, J.A.; Koel, B.E.; et al. Catalytic Consequences of Hierarchical Pore Architectures within MFI and FAU Zeolites for Polyethylene Conversion. ACS Catal. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Upare, D.P.; Lee, C.W.; Lee, D.K.; Kang, Y.S. Effect of Acidity of Solid Acid Catalysts during Non-Oxidative Thermal Decomposition of LDPE. Carbon Lett. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Mondal, B.K.; Ahmed, N.; Hossain, M.D. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Waste High-Density (HDPE) and Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) to Produce Liquid Hydrocarbon Using Silica-Alumina Catalyst. J. Bangladesh Acad. Sci. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pyra, K.; Tarach, K.A.; Janiszewska, E.; Majda, D.; Góra-Marek, K. Evaluation of the Textural Parameters of Zeolite Beta in LDPE Catalytic Degradation: Thermogravimetric Analysis Coupled with FTIR Operando Studies. Molecules 2020, 25, 926. [CrossRef]

- TOMASZEWSKA, K.; KalŁuzna-CZAPLIŃSKA, J.; JOZWIAK, W. Thermo-Catalytic Degradation of Low Density Polyethylene over Clinoptilolite - The Effect of Carbon Residue Deposition. Polimery/Polymers 2010, 55, 222–226. [CrossRef]

- Okonsky, S.T.; Krishna, J.V.J.; Toraman, H.E. Catalytic Co-Pyrolysis of LDPE and PET with HZSM-5{,} H-Beta{,} and HY: Experiments and Kinetic Modelling. React. Chem. Eng. 2022, 7, 2175–2191. [CrossRef]

- Inayat, A.; Inayat, A.; Schwieger, W.; Klemencova, K.; Lestinsky, P. Chemical Recycling of Waste Polypropylene via Thermo-catalytic Pyrolysis over HZSM-5 Catalysts. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2023, 46, 1289–1297. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, O.D.; Toraman, H.E. Conversion of Polypropylene into Light Hydrocarbons and Aromatics by Metal Exchanged Zeolite Catalysts. Langmuir 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.Y.; Fu, S.; Lee, J. Enhancement of Light Hydrocarbon Production from Polypropylene Waste by HZSM-11-Catalyzed Pyrolysis. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bautista, A.S.; Rivera, K.N.O.; Suratos, T.A.K.M.; Dimaano, M. Conversion of Polypropylene (PP) Plastic Waste to Liquid Oil through Catalytic Pyrolysis Using Philippine Natural Zeolite. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Irawan, A.; Kurniawan, T.; Nurkholifah, N.; Melina, M.; Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Firdaus, M.A.; Alwan, H.; Bindar, Y. Pyrolysis of Polyolefins into Chemicals Using Low-Cost Natural Zeolites. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2023, 14, 1705–1719. [CrossRef]

- Heng, J.Z.X.; Tan, T.T.Y.; Li, X.; Loh, W.W.; Chen, Y.; Xing, Z.; Lim, Z.; Ong, J.L.Y.; Lin, K.S.; Nishiyama, Y.; et al. Pyrolytic Depolymerization of Polyolefins Catalysed by Zirconium-Based UiO-66 Metal–Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202408718. [CrossRef]

- Nisar, J.; Farid, R.; Ali, G.; Muhammad, F.; Shah, A.; Farooqi, Z.H.; Shah, F. Kinetics and Fuel Properties of the Oil Obtained from the Pyrolysis of Polypropylene over Cobalt Oxide. Clean. Chem. Eng. 2022, 4, 100083. [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.K.; Tiwari, A.C. Comparative Study of Catalytic Pyrolysis of Waste Polypropylene(PP) Using Silica Alumina, Kaolin Clay and Calcium Bentonite Catalyst. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2020.

- Aisien, Felix Aibuedefe; Aisien, E.T. Liquid Fluids from Thermo-Catalytic Degradation of Waste Low-Density Polyethylene Using Spent Fcc Catalyst. Detritus 2022, 75–83. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.N.; Riaz, S.; Ahmad, N.; Jaseer, E.A. Pioneering Aromatic Generation from Plastic Waste via Catalytic Thermolysis: A Minireview. Energy and Fuels 2024, 38, 11363–11390. [CrossRef]

- Miandad, R.; Rehan, M.; Barakat, M.A.; Aburiazaiza, A.S.; Khan, H.; Ismail, I.M.I.; Dhavamani, J.; Gardy, J.; Hassanpour, A.; Nizami, A.S. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Plastic Waste: Moving toward Pyrolysis Based Biorefineries. Front. Energy Res. 2019, 7, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Wootthikanokkhan, J.; Jaturapiree, A.; Meeyoo, V. Effect of Metal Compounds and Experimental Conditions on Distribution of Products from PVC Pyrolysis. J. Polym. Environ. 2003, 11, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Iida, T.; Nakanishi, M.; Goto, K. Investigations on Poly(Vinyl Chloride) - 1. Evolution of Aromatics on Pyrolysis of Poly(Vinyl Chloride) and Its Mechanism. J Polym Sci Part A-1 Polym Chem 1974, 12, 737–749. [CrossRef]

- Lattimer, R.P.; Kroenke, W.J. The Functional Role of Molybdenum Trioxide as a Smoke Retarder Additive in Rigid Poly(Vinyl Chloride). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1981, 26, 1191–1210. [CrossRef]

- Loong, G.K.M.; Okada, K.; Morishige, N.; Konakahara, N.; Yokota, M.; Tanoue, K. Investigation of the Uptake and Catalytic Effect of Calcium and Potassium-Based Additives under Low-Temperature Pyrolysis of Polyvinyl Chloride. Environ. Prog. \& Sustain. Energy 2024, 43, e14352. [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, A.A.; Chekryshkin, Y.S.; Rudometova, O. V.; Vnutskikh, Z.A. Application of Inorganic Compounds at the Thermal Processing of Polyvinylchloride. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2008, 81, 1673–1685. [CrossRef]

- Glas, D.; Hulsbosch, J.; Dubois, P.; Binnemans, K.; Vos, D. De End-of-Life Treatment of Poly(Vinyl Chloride) and Chlorinated Polyethylene by Dehydrochlorination in Ionic Liquids. ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 610–617. [CrossRef]

- Triacca, V.J.; Gloor, P.E.; Zhu, S.; Hrymak, A.N.; Hamielec, A.E. Free Radical Degradation of Polypropylene : Random Chain Scission. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1993, 33, 445–454. [CrossRef]

- Kurt Dr. Rauer, P.D. Degradation of Polyethylene by Means of Agents Generating Free Radicals. Eur. Pat. Off. 1987.

- Uebe, J.; Zukauskaite, A.; Kryzevicius, Z.; Vanagiene, G. Use of 2-Ethylhexyl Nitrate for the Slow Pyrolysis of Plastic Waste. Processes 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.S.; Fernandes, A.; Muñoz, M.; Ribeiro, M.R.; Silva, J.M. Analyzing HDPE Thermal and Catalytic Degradation in Hydrogen Atmosphere: A Model-Free Approach to the Activation Energy. Catalysts 2024. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Costa, L.; Marques, M.M.; Fonseca, I.; Lemos, M.A.N.D.A.; Lemos, F. The Effect of ZSM-5 Zeolite Acidity on the Catalytic Degradation of High-Density Polyethylene Using Simultaneous DSC/TG Analysis. Appl. Catal. A-general 2012, 413, 183–191. [CrossRef]

- Koç, A. Thermal Pyrolysis of Waste Disposable Plastic Syringes and Pyrolysis Thermodynamics. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 12, 96–113. [CrossRef]

- Karaduman, A.; Koçak, M.Ç.; Bilgesü, A.Y. Flash Vacuum Pyrolysis of Low Density Polyethylene in a Free-Fall Reactor. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2003, 42, 181–191. [CrossRef]

- Kayacan, İ.; Doğan, Ö.M. Pyrolysis of Low and High Density Polyethylene. Part I: Non-Isothermal Pyrolysis Kinetics. Energy Sources Part A-recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2008, 30, 385–391. [CrossRef]

- Khaghanikavkani, E.; Farid, M. Thermal Pyrolysis of Polyethylene: Kinetic Study. Energy Sci. Technol. 2011, 2, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Audisio, G.; Bertini, F.; Beltrame, P.L.; Carniti, P. Catalytic Degradation of Polyolefins. Macromol. Symp. 1992, 57, 191–209. [CrossRef]

- Anene, F.; Fredriksen, B.; Sætre, K.A.; Tokheim, L.-A. Experimental Study of Thermal and Catalytic Pyrolysis of Plastic Waste Components. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Huang, G.; Guo, L.; Chen, Y.; Ding, C.; Ding, C.; Liu, C. Enhancement of Catalytic Combustion and Thermolysis for Treating Polyethylene Plastic Waste. 2021, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.P.; Mustafa, I.; Gopanna, A.; Thomas, S.P. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Waste Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) Carry Bags to Fuels: Experimental and Exergy Analyses. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Scorah, M.J.; Zhu, S.; Psarreas, A.; McManus, N.T.; Dhib, R.; Tzoganakis, C.; Penlidis, A. Peroxide-controlled Degradation of Polypropylene Using a Tetra-functional Initiator. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2009, 49, 1760–1766. [CrossRef]

- Masai, Y.; Kiyotsukuri, T. Effects of Additves on the Thermal Decomposition of Polypropylene. Sen-i Gakkaishi 1991, 47, 37–43. [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Matsuoka, S.; Hisano, S. Studies on Reactions of Polypropylene. VIII. The Thermal Degradation of Polypropylene Accelerated by Polyglycidyl Methacrylate. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1967, 40, 1526–1530. [CrossRef]

- Zorriqueta, I.J. Pyrolysis of Polypropylene by Ziegler-Natta Catalysts. 2006.

- Hu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, N.; Yuan, H.; Guo, Q.; Jiao, L.; Ma, Z. Catalytic Stepwise Pyrolysis for Dechlorination and Chemical Recycling of PVC-Containing Mixed Plastic Wastes: Influence of Temperature, Heating Rate, and Catalyst. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168344. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cao, Z.; Fang, Z.; Guo, Z. Influence of Fullerene on the Kinetics of Thermal and Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of High-Density Polyethylene by Capturing Free Radicals. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 114, 1287–1294. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.S.; Saber, M.G. Thermal and Catalytic Degradation Kinetics of High-Density Polyethylene Over NaX Nano-Zeolite. J. Chem. Pet. Eng. 2016, 17, 33–43.

- Zaggout, F.R.; Mughari, A.R. Al; Garforth, A. Catalytic Degradation of High Density Polyethylene Using Zeolites. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. Part A-toxic/hazardous Subst. Environ. Eng. 2001, 36, 163–175. [CrossRef]

- Anggoro, D.D. Optimization of Catalytic Degradation of Plastic to Aromatics Over HY Zeolite. 2005.

- Lee, K.-H.; Jeon, S.-G.; Kim, K.-H.; Noh, N.-S.; Shin, D.-H.; Seo, Y.-H.; Yee, J.-J.; Kim, G.-T. Thermal and Catalytic Degradation of Waste High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) Using Spent FCC Catalyst. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2003, 20, 693–697. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Shin, D.-H. Catalytic Degradation of Waste Polyolefinic Polymers Using Spent FCC Catalyst with Various Experimental Variables. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2003, 20, 89–92. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Sadhukhan, A.K.; Gupta, P.; Singh, R.K.; Ruj, B. Recovery of Enhanced Gasoline-Range Fuel from Catalytic Pyrolysis of Waste Polypropylene: Effect of Heating Rate, Temperature, and Catalyst on Reaction Kinetics, Products Yield, and Compositions. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 188, 793–806. [CrossRef]

- Prabha, B.; Ramesh, D.; Sriramajayam, S.; Uma, D. Optimization of Pyrolysis Process Parameters for Fuel Oil Production from the Thermal Recycling of Waste Polypropylene Grocery Bags Using the Box–Behnken Design. Recycling 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Aremanda, R.B.; Singh, R.K. Conversion of Waste Polypropylene Disposable Cups into Liquid Fuels by Thermal and Catalytic Pyrolysis Using Activated Carbon. Sustinere J. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 6, 79–91. [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Li, X.; Shao, S.; Cai, Y. Jet Fuel Range Hydrocarbon Generation from Catalytic Pyrolysis of Lignin and Polypropylene with Iron-Modified Activated Carbon. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024. [CrossRef]

- Faisal, F.; Rasul, M.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Jahirul, M.I. Optimisation of Process Parameters to Maximise the Oil Yield from Pyrolysis of Mixed Waste Plastics. Sustainability 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jaydev, S.D.; Martín, A.J.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Direct Conversion of Polypropylene into Liquid Hydrocarbons on Carbon-Supported Platinum Catalysts. ChemSusChem 2021. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zaidi, B.Y.; Almukhtar, R.; Hamawand, I. Optimization of Polypropylene Waste Recycling Products as Alternative Fuels through Non-Catalytic Thermal and Catalytic Hydrocracking Using Fresh and Spent Pt/Al2O3 and NiMo/Al2O3 Catalysts. Energies 2023, 16, 4871. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Tadauchi, M. Pyrolytically Decomposing Waste Plastic, e.g. PVC 1994.

- Castro, A.; Carneiro, C.; Vilarinho, C.; Soares, D.; Maçães, C.; Sousa, C.; Castro, F. Study of a Two Steps Process for the Valorization of PVC-Containing Wastes. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2013, 4, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, G.; Stalpaert, M.; Skorynina, A.A.; Bugaev, A.L.; Janssens, K.; Emelen, L. Van; Lemmens, V.; Colemonts, C.M.C.J.; Sakellariou, D.; Vos, D. De Catalytic Tandem Dehydrochlorination–Hydrogenation of PVC towards Valorisation of Chlorinated Plastic Waste. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 4401–4412. [CrossRef]

- Scalfani, V.; Ezendu, S.; Ryoo, D.; Shinde, P.S.; Anderson, J.L.; Szilvási, T.; Rupar, P.A.; Bara, J.E. PVC Modification through Sequential Dehydrochlorination–Hydrogenation Reaction Cycles Facilitated via Fractionation by Green Solvents. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Figge, K.; Findeiß, W. Untersuchungen Zum Mechanismus Der PVC-Stabilisierung Mit Organozinn-Verbindungen. Angew. Makromol. Chemie 1975, 47, 141–179. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; ur Rehman, H.; Ali, S.; Sarwar, M.I. Thermal Degradation of Poly (Vinyl Chloride)-Stabilization Effect of Dichlorotin Dioxine. Int. J. Polym. Mater. 2000, 46, 547–559. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Qadeer, R. Effects of Alkaline Earth Metal Stearates on the Dehydrochlorination of Poly(Vinyl Chloride). J. Therm. Anal. 1994, 42, 1167–1173. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yan, X.Y.; Shibata, K.; Uda, T.; Tada, M.; Hirasawa, M. Thermogravimetric-Mass Spectrometric Analysis of the Reactions between Oxide (ZnO, Fe2O3 or ZnFe2O4) and Polyvinyl Chloride under Inert Atmosphere. Mater. Trans. JIM 2000, 41, 1342–1350. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).