Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. PFKFB3 is expressed in tumor microinvironment in colorecal cancer as well as in benign neoplasms

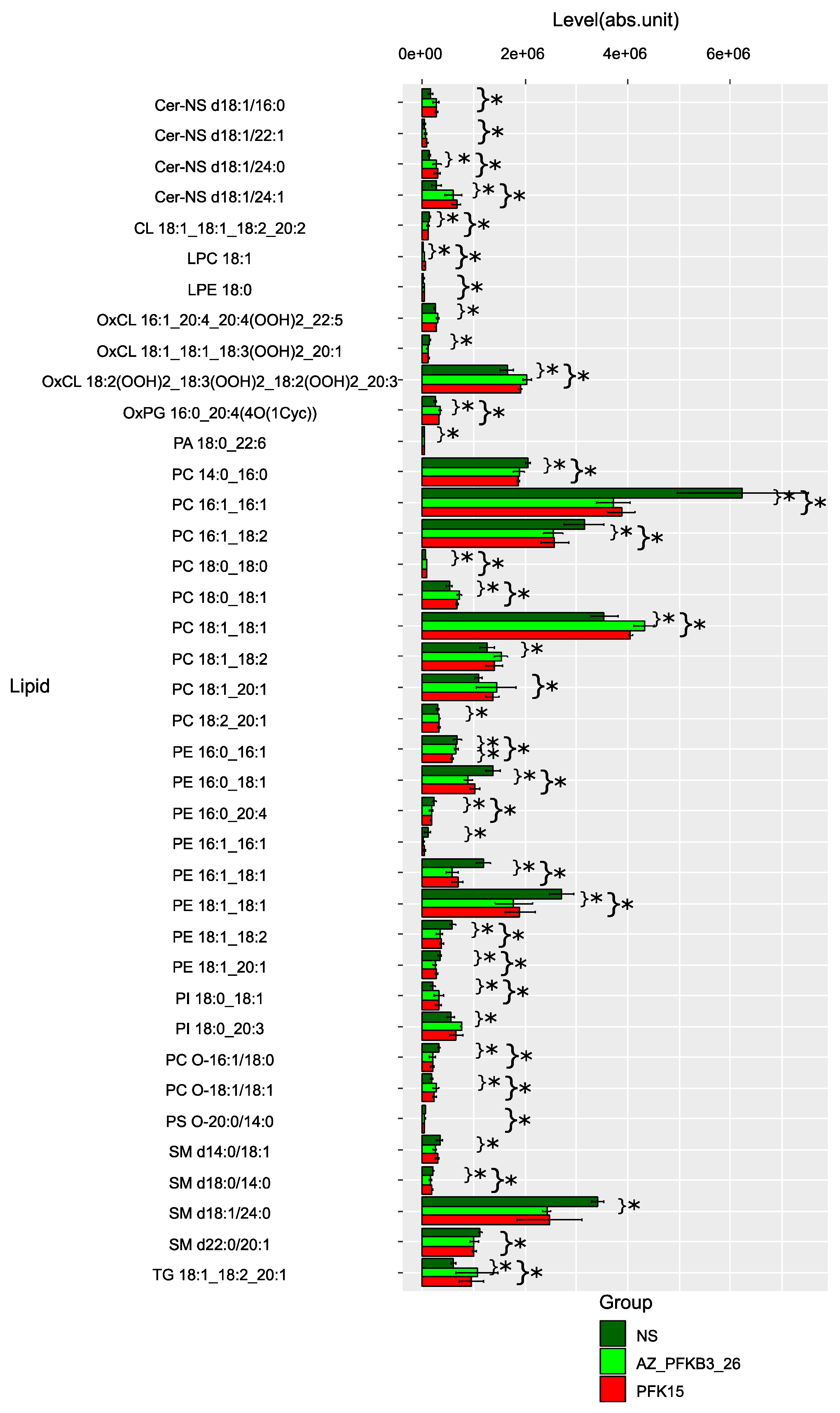

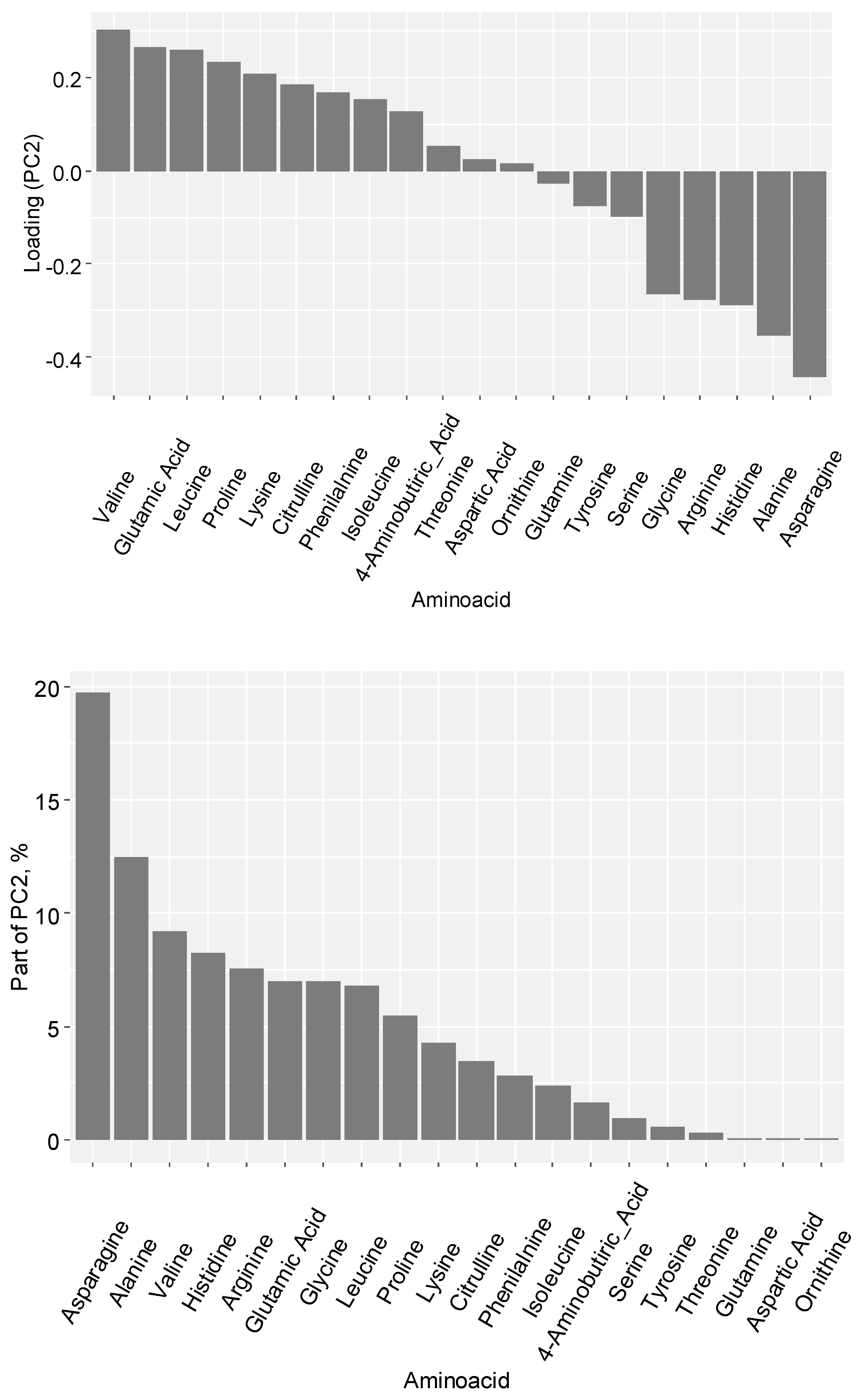

2.2. PFKFB3 inhibition shifts tumor-associated macrophage metabolism toward immunosuppressive sphingolipid and pro-inflammatory arachidonic acid pathways

| Name metabolic pathways | The total number of metabolites involved | The number of metabolites matching the experimental data | P | -LOG(P) | Effect on pathway |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 36 | 7 | 6.13E-10 | 9.2127 | 0.26922 |

| Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis | 14 | 2 | 0.003979 | 2.4002 | 0.1875 |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | 16 | 2 | 0.005207 | 2.2834 | 0.13636 |

| Sphingolipid metabolism | 21 | 2 | 0.008937 | 2.0488 | 0.1875 |

| Phosphatidylinositol signaling system | 28 | 2 | 0.015655 | 1.8053 | 0.12766 |

| Linoleic acid metabolism | 5 | 1 | 0.035028 | 1.4556 | 0.25 |

| alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism | 13 | 1 | 0.08876 | 1.0518 | 0.125 |

| Ether lipid metabolism | 20 | 1 | 0.13353 | 0.87443 | 0.05263 |

| Inositol phosphate metabolism | 30 | 1 | 0.19402 | 0.71216 | 0.05 |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | 36 | 1 | 0.22844 | 0.64122 | 0.02778 |

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

4.2. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis

4.3. Immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy

4.4. Isolation of monocytes and model of primary human TAMs

4.5. Macrophage lipidome analysis

4.6. Amino acid profile analysis

4.7. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riabov, V.; Gudima, A.; Wang, N.; Mickley, A.; Orekhov, A.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Role of Tumor Associated Macrophages in Tumor Angiogenesis and Lymphangiogenesis. Front Physiol 2014, 5 MAR. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kzhyshkowska, J.; Shen, J.; Larionova, I. Targeting of TAMs: Can We Be More Clever than Cancer Cells? Cellular & Molecular Immunology 2024 21:12 2024, 21, 1376–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kzhyshkowska, J.; Yin, S.; Liu, T.; Riabov, V.; Mitrofanova, I. Role of Chitinase-like Proteins in Cancer. Biol Chem 2016, 397, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, I.; Kazakova, E.; Gerashchenko, T.; Kzhyshkowska, J. New Angiogenic Regulators Produced by TAMs: Perspective for Targeting Tumor Angiogenesis. 2021, 13, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lian, J.; Lu, H. The Role of SPP1+TAMs in Cancer: Impact on Patient Prognosis and Future Therapeutic Targets. Int J Cancer 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakova, E.; Iamshchikov, P.; Larionova, I.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Macrophage Scavenger Receptors: Tumor Support and Tumor Inhibition. Front Oncol 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larionova, I.; Tuguzbaeva, G.; Ponomaryova, A.; Stakheyeva, M.; Cherdyntseva, N.; Pavlov, V.; Choinzonov, E.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Human Breast, Colorectal, Lung, Ovarian and Prostate Cancers. Front Oncol 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimova, A.F.; Khalitova, A.R.; Suezov, R.; Markov, N.; Mukhamedshina, Y.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Huber, M.; Simon, H.U.; Brichkina, A. Immunometabolism of Tumor-Associated Macrophages: A Therapeutic Perspective. Eur J Cancer 2025, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, I.; Kazakova, E.; Patysheva, M.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Transcriptional, Epigenetic and Metabolic Programming of Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowski, K.; Rosik, J.; Machaj, F.; Supplitt, S.; Wiczew, D.; Jabłońska, K.; Wiechec, E.; Ghavami, S.; Dzięgiel, P. Role of Pfkfb3 and Pfkfb4 in Cancer: Genetic Basis, Impact on Disease Development/Progression, and Potential as Therapeutic Targets. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillo, S.M.; Gatesman, T.A.; Chilukuri, A.; Varadharajan, S.; Johnson, B.J.; David Premkumar, D.R.; Jane, E.P.; Plute, T.J.; Koncar, R.F.; Stanton, A.C.J.; et al. An ERK5-PFKFB3 Axis Regulates Glycolysis and Represents a Therapeutic Vulnerability in Pediatric Diffuse Midline Glioma. Cell Rep 2024, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.P.; Ning, W.R.; Jiang, Z.Z.; Peng, Z.P.; Zhu, L.Y.; Zhuang, S.M.; Kuang, D.M.; Zheng, L.; Wu, Y. Glycolytic Activation of Peritumoral Monocytes Fosters Immune Privilege via the PFKFB3-PD-L1 Axis in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Hepatol 2019, 71, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, I.; Patysheva, M.; Iamshchikov, P.; Kazakova, E.; Kazakova, A.; Rakina, M.; Grigoryeva, E.; Tarasova, A.; Afanasiev, S.; Bezgodova, N.; et al. PFKFB3 Overexpression in Monocytes of Patients with Colon but Not Rectal Cancer Programs Pro-Tumor Macrophages and Is Indicative for Higher Risk of Tumor Relapse. Front Immunol 2023, 13, 1080501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, I.; Kiselev, A.; Kazakova, E.; Liu, T.; Patysheva, M.; Iamshchikov, P.; Liu, Q.; Mossel, D.M.; Riabov, V.; Rakina, M.; et al. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Respond to Chemotherapy by Detrimental Transcriptional Reprogramming and Suppressing Stabilin-1 Mediated Clearance of EGF. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1000497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, R. de F.; Andrade, L.N. de S.; Bustos, S.O.; Chammas, R. Phosphatidylcholine-Derived Lipid Mediators: The Crosstalk Between Cancer Cells and Immune Cells. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 768606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabold, K.; Aschenbrenner, A.; Thiele, C.; Boahen, C.K.; Schiltmans, A.; Smit, J.W.A.; Schultze, J.L.; Netea, M.G.; Adema, G.J.; Netea-Maier, R.T. Enhanced Lipid Biosynthesis in Human Tumor-Induced Macrophages Contributes to Their Protumoral Characteristics. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8, e000638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Weir, J.D.; Hartung, R. The Composition of Linoleic Acid and Conjugated Linoleic Acid Has Potent Synergistic Effects on the Growth and Death of RAW264.7 Macrophages: The Role in Anti-Inflammatory Effects. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, T.; Adhikary, T.; Wortmann, A.; Finkernagel, F.; Lieber, S.; Schnitzer, E.; Legrand, N.; Schober, Y.; Nockher, W.A.; Toth, P.M.; et al. Deregulation of PPARβ/δ Target Genes in Tumor-Associated Macrophages by Fatty Acid Ligands in the Ovarian Cancer Microenvironment. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 13416–13433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, W.S.; Müller, S.; Yang, J.-S.; Innes-Gold, S.; Das, S.; Reinhardt, F.; Sigmund, K.; Phadnis, V. V.; Wan, Z.; Eaton, E.; et al. Ether Lipids Influence Cancer Cell Fate by Modulating Iron Uptake. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.G.; Zhang, X.M.; Wu, X.; Zhou, C.K.; Liu, Z.Z.; Luo, X.Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W.; Yang, Y.J. Covalent Organic Frameworks-Delivered Reuterin Drives Trained Immunity in Tumor-Associated Macrophages to Enhance Melanoma Immunotherapy via Glycerophospholipid Metabolism. Advanced Science 2025, e04784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Bai, F.; Ren, X.; Sun, R.; Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; et al. Phosphoinositide-Binding Protein TIPE1 Promotes Alternative Activation of Macrophages and Tumor Progression via PIP3/Akt/TGFb Axis. Cancer Res 2022, 82, 1603–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Geng, X.; Jia, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, H. Arachidonic Acid Metabolism Controls Macrophage Alternative Activation Through Regulating Oxidative Phosphorylation in PPARγ Dependent Manner. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 618501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, K.; Shen, H.; Yang, P.; Li, S.; et al. Quantitative Profiling of Glycerophospholipids during Mouse and Human Macrophage Differentiation Using Targeted Mass Spectrometry. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, K.; Shen, H.; Yang, P.; Li, S.; et al. Quantitative Profiling of Glycerophospholipids during Mouse and Human Macrophage Differentiation Using Targeted Mass Spectrometry. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, J.P.; Casas, J.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Bioactive Lipid Signaling and Lipidomics in Macrophage Polarization: Impact on Inflammation and Immune Regulation. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1550500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, W.Y.; Zhou, Q.D.; York, A.G.; Williams, K.J.; Scumpia, P.O.; Kronenberger, E.B.; Hoi, X.P.; Su, B.; Chi, X.; Bui, V.L.; et al. Toll-Like Receptors Induce Signal-Specific Reprogramming of the Macrophage Lipidome. Cell Metab 2020, 32, 128–143.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Benign intestinal neoplasms (1) | Colorectal cancer (2) | Rectal cancer (3) | Colon cancer (4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 78,22±35,54 (n=50) p1,2<0,00001 |

30,19±25,33 (n=111) |

24,72±21,53 (n=49) p1,3<0,00001 p3,4<0,045 |

34,50±27,37 (n=62) p1,2<0,00001 |

| Name metabolic pathways | The total number of metabolites involved | The number of metabolites matching the experimental data | P | LOG(P) | Effect on pathway |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 36 | 7 | 6.13E-10 | 9.2127 | 0.26922 |

| Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis | 14 | 2 | 0.003979 | 2.4002 | 0.1875 |

| Sphingolipid metabolism | 21 | 2 | 0.008937 | 2.0488 | 0.1875 |

| Linoleic acid metabolism | 5 | 1 | 0.035028 | 1.4556 | 0.25 |

| alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism | 13 | 1 | 0.08876 | 1.0518 | 0.125 |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | 16 | 1 | 0.1082 | 0.96578 | 0.09091 |

| Ether lipid metabolism | 20 | 1 | 0.13353 | 0.87443 | 0.05263 |

| Phosphatidylinositol signaling system | 28 | 1 | 0.18224 | 0.73936 | 0.10638 |

| Inositol phosphate metabolism | 30 | 1 | 0.19402 | 0.71216 | 0.05 |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | 36 | 1 | 0.22844 | 0.64122 | 0.02778 |

| Inhibitor | Lipid Class | Specific Lipids | Regulation | Pathway | Effects of PFKFB3 inhibitors on TAMs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFK15 | Glycerophospholipids | Phosphatidylcholines, PCs (PC 14:0_16:0, PC 16:1_16:1, PC 16:1_18:2, PC 18:0_18:0, PC 18:0_18:1, PC 18:1_18:1, PC 18:1_18:2, PC 18:1_20:1, PC 18:2_20:1, PC O-16:1/18:0, PC O-18:1/18:1) | ↓ | Glycerophospholipid metabolism | Membrane destabilization Impairing of phagocytosis, monocyte migration and production of pro-inflammatory citokine production (Tumor-suppressive) [15] |

| Sphingolipids | Ceramides, Cer (Cer-NS d18:1/16:0, Cer-NS d18:1/22:1, Cer-NS d18:1/24:0, Cer-NS d18:1/24:1) | ↑ | Sphingolipid metabolism | •Anti-inflammatory skewing •M2-like polarization (Tumor-promotive) [16] |

|

| Fatty Acids | Linoleic acid derivatives, PCs (LPC 18:2, PC 16:1_18:2, PC 18:1_18:2, PC 18:2_20:1, PE 18:1_18:2, OxCL 18:1_18:1_18:3(OOH)2_20:1, OxCL 18:2(OOH)2_18:3(OOH)2_18:2(OOH)2_20:3) | ↑ | Linoleic acid metabolism | •Increasing of pro-inflammatory mediators [17,18] |

|

| Ether Lipids | Plasmalogens (PC O-16:1/18:0, PC O-18:1/18:1, PS O-20:0/14:0) | ↓ | Ether lipid metabolism | •Diminished antioxidant capacity [19] |

|

| AZ PFKFB3 26 | Glycerophospholipids | Phosphatidylethanolamines (PE 16:0_16:1, PE 16:0_18:1, PE 16:0_20:4, PE 16:1_16:1, PE 16:1_18:1, PE 18:1_18:1, PE 18:1_18:2, PE 18:1_20:1) | ↓ | Glycerophospholipid metabolism | • Supression of M1 activation • Tumor-promotive effects [20] |

| Phosphoinositides | PIP2, PIP3 | ↓ | PI signaling system of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway | Reduction of inflammatory responses [21] | |

| Oxidized Lipids | Oxidized phosphatidylcholines (OxPC 16:0_20:4(4O(1Oye)), OxPC 18:1_18:3(OOH)2_20:1, OxPC 18:2(OOH)2_18:3(OOH)2_18:2(OOH)2_20:3) | ↑ | Arachidonic acid metabolism | Suppression of lipid peroxidation and reduction of pro-inflammatory mediators, which may lead to attenuation of oxidative stress and modulation of the inflammatory response [22]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).