1. Introduction

Negative social experiences are linked to the development of social anxiety [

1]. Individuals with autism, a neurodevelopmental disorder marked by impaired social communication and interaction [

2], face more adverse social encounters, increasing their risk for social anxiety. Clinicians frequently report anxiety, especially social anxiety, in autistic individuals [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Due to neurobiological factors, early social deprivation, and poor social skills, these individuals may avoid social situations, reducing opportunities to practice and improve social functioning, thus creating a self-perpetuating cycle.

Theorists suggest autism’s strong genetic basis impacts brain circuits related to social interaction [

7]. Prenatal stress and elevated fetal stress hormones, particularly cortisol and sex steroids, have been linked to autism and may affect social and emotional development [

8]. For instance, higher fetal testosterone is associated with poorer empathy and emotion recognition [

9]. Since these prenatal hormonal differences may affect the development of abilities related to social interaction, anxiety, and cognition, the combination of decreased social abilities and elevated stress response may lead autistic individuals to become more socially anxious and engage less often in meaningful and productive social interaction throughout their development.

Beyond genetics, autistic individuals often struggle with emotional identification, expression, and regulation. Alexithymia—difficulty recognizing and verbalizing emotions—is common and can understandably contribute to emotional somatization due to poor symbolic processing [

10,

11]. Language is also thought to aid emotion regulation and self-reflection, and without it, bodily sensations of emotion can feel overwhelming and anxiety-inducing [

12]. This makes the experience of emotions more somatically negative and potentially more anxiety arousing.

Researchers and theorists have proposed that anxiety may be a central feature of autism. Singletary [

7] suggests that the allostatic load, or the long-term effects of repeated and chronic stress, can lead to or increase traits often observed in autistic individuals. In fact, in response to repeated stress, the brain alters to become more sensitive to stress, strengthening the stress response. As an individual experiences more negative social interactions and has less exposure to healthy and informative interactions during development, the more they will display social differences and social anxiety [

7]. Indeed, stress and anxiety seem to be prominent features in autism.

It may be because of this heightened stress response, namely related to social situations, that autistic individuals are more susceptible to social anxiety and begin withdrawing from social interaction and relationships early on. For example, autistic individuals often experience overarousal in response to eye contact, leading to gaze avoidance and thus increased social difficulties [

13]. As Singletary [

7] explains, “what starts as an adaptive response to perceived threat is maladaptive” (p. 35). Because of this, social skills and cognition, such as mentalization skills including empathic accuracy, are hindered.

People with Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) tend to misinterpret certain stimuli, particularly by misinterpreting emotions as more negative or less positive than they actually are [

14]. Thus, people with higher social anxiety levels may suffer from lower theory of mind abilities which could be related to these interpretation biases. Alvi et al. [

14] found that higher levels of social anxiety in a non-clinical sample negatively impacted theory of mind and empathic accuracy. In another study, individuals that meet clinical criteria for social anxiety disorder performed lower on a theory of mind (ToM) task than healthy controls, but still scored higher than individuals with ASD were found to perform [

15]. According to the cognitive-behavioral model, people with social anxiety disorder allocate too much attention and analysis to their own actions which may impede the acquisition of the ability to accurately analyze others’ states of minds during social interactions. Thus, as anxiety goes up, so does self-focused attention, meaning ToM accuracy goes down.

Individuals with ASD repeatedly show significant difficulty with ToM/emotion recognition and identification tasks across numerous studies [

16,

17]. This leaves the questions, since social cognitive differences tend to be present in autistic individuals, would social anxiety levels correlate with these differences? Indeed, autistic adults and children show higher than average levels of social anxiety. While social anxiety and ASD are repeatedly correlated in the literature, research has shown that the two conditions have unique features separate from each other; namely ASD emphasizes social difficulties as opposed to social anxiety, theory of mind differences, restricted interests, and rigid routines [

18]. Some research has suggested that lack of social/emotional awareness may buffer the effects of anxiety on some individuals with ASD [

3,

5]. Thus, the role of mentalization abilities, or the ability to accurately perceive one’s own and other’s mental states, intentions, and affects [

2] should be a point of interest when trying to determine more specifically why individuals with autism experience heightened levels of anxiety.

Some research has already been done regarding the role of encoding empathy, that is the ability to empathically identify another’s feelings, and its effects on social anxiety levels in autistic adolescents. Anxiety levels in people with autism seem to rise along with empathic skills, meaning that empathy and social anxiety bear a positive correlation with each other. However, a threshold appears to pertain, such that upon attainment of a certain higher level of empathy, social anxiety lowers, creating an inverted U-shaped relationship between social anxiety and empathy [

4]. This is notably different from Alvi et al.’s [

14] and Hezel and McNally’s [

15] findings in participants without ASD, that higher social anxiety showed lower abilities across components of the larger mentalization construct such as ToM, emotion recognition, and empathic accuracy.

White et al. [

18] proposed that some autistic individuals who experience more social anxiety may do so because of particularly heightened insight and awareness of their social differences. Perhaps as mentalization skills increase, so does the ability to accurately pick up on others’ judgments, thus making a person more anxious. It can then be speculated that people without autism who present with social anxiety may think they have lower social skills than they do. Their belief that others are negatively evaluating them may hypothetically result from having lower mentalization abilities and misinterpreting others’ judgments and thoughts.

Zuckerman [

19] found that, in a sample of individuals diagnosed with ASD that a larger gap between a person’s social comprehension and their actual behavior (or social skills) were positively correlated with social anxiety. The participants with higher social comprehension actually avoid social situations more, possibly because of their anxiety. This suggests that those with autism who possess greater social awareness, who would be more likely to have higher mentalization abilities, are more aware of other people’s negative judgments, leading to more social anxiety.

Social anxiety disorder has been found to be correlated with more somatic complaints and conditions [

20,

21]. The authors point out that the presence of anxiety itself may be a risk factor for developing somatic complaints, which aligns with the heightening of tension in the body and disruption in digestive processes that often accompany anxiety. Additionally, the heightened self and body awareness that accompanies social anxiety may be contributing to increased somatic-symptom awareness as well [

20]. Given previous findings suggesting lower social cognition skills in individuals with social anxiety disorder [

14,

15] the role of social cognition in somatic symptoms may be important. Additionally, the findings and theories that reduced ability to recognize and process one’s own emotions can lead to higher somatization of emotions suggests a need for understanding mentalization and alexithymia’s role in somatic symptoms [

10,

22].

Increased neurological and immunological health issues have been observed in individuals with a diagnosis of ASD, namely neurological and immunological health issues, in a twin-study [

23]. It is unknown whether social anxiety contributes to the link between a diagnosis of ASD and increased somatic health problems. However, given the established relationship between social anxiety and somatic symptoms, and previous findings suggesting these are both heightened in autistic individuals, it is worth examining.

Indeed, people with somatoform disorders, somatic symptoms with no underlying physical causes, were found to have lower emotional awareness and theory of mind [

24]. The authors found a decreased ability to describe one’s own feelings and evaluate the feelings of others, suggesting social cognition skills serve as a protective factor against somatic somatology. Anxiety levels were also higher in individuals with somatoform disorders. The authors suggest a lack of understanding of emotions may lead to more somatic/physical expression and experience of the emotion rather than a conscious awareness and experience of the emotions, similar to other findings, suggestions, and theories [

10,

22]. A lack of theory of mind can also lead to more interpersonal and social distress, contributing to anxiety and somatic experiences related to anxiety [

24]. Thus far, no studies can be found on the relationship among somatic complaints, anxiety, and social cognition in autistic people.

Understanding these relationships may improve interventions for autistic individuals experiencing social anxiety and somatic symptoms. Clinicians may benefit from assessing social cognition when addressing anxiety and physical complaints in this population, as the patterns may differ from those without ASD.

This study hypothesizes that:

participants with ASD will display lower social perception skills, higher social anxiety levels, and higher somatic symptomology than those without ASD

higher social anxiety levels and lower social perceptive skills will be correlated with higher somatic symptoms

social perception skills will mediate the relationship between ASD and higher social anxiety levels

social cognition skills and social anxiety levels will mediate the relationship between ASD and heightened somatic symptomology, with increased social cognition skills being associated with decreased somatic symptoms and increased social anxiety levels being associated with increased somatic symptoms.

Post-hoc analyses were performed when relevant regarding potential sex differences in findings.

4. Discussion

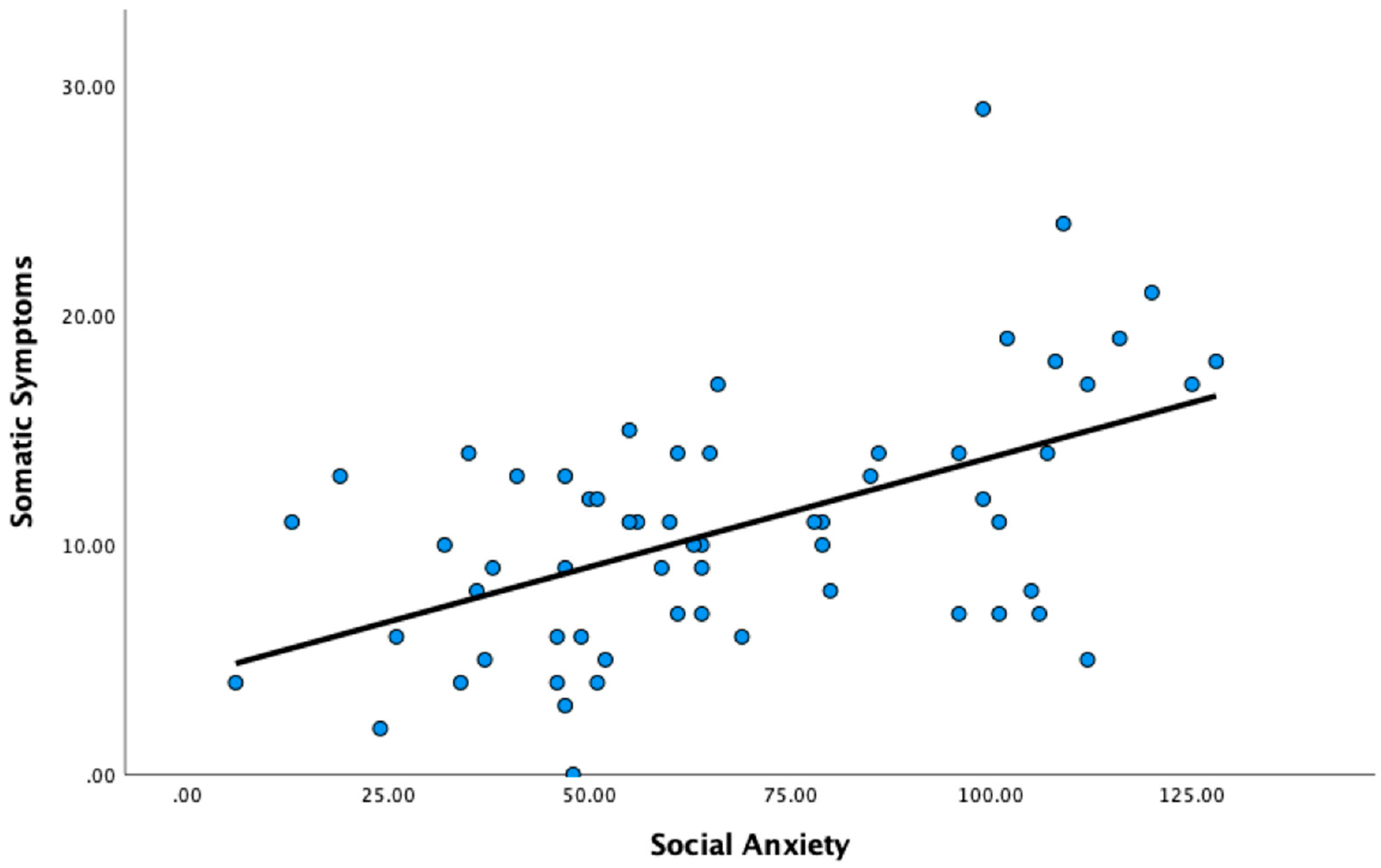

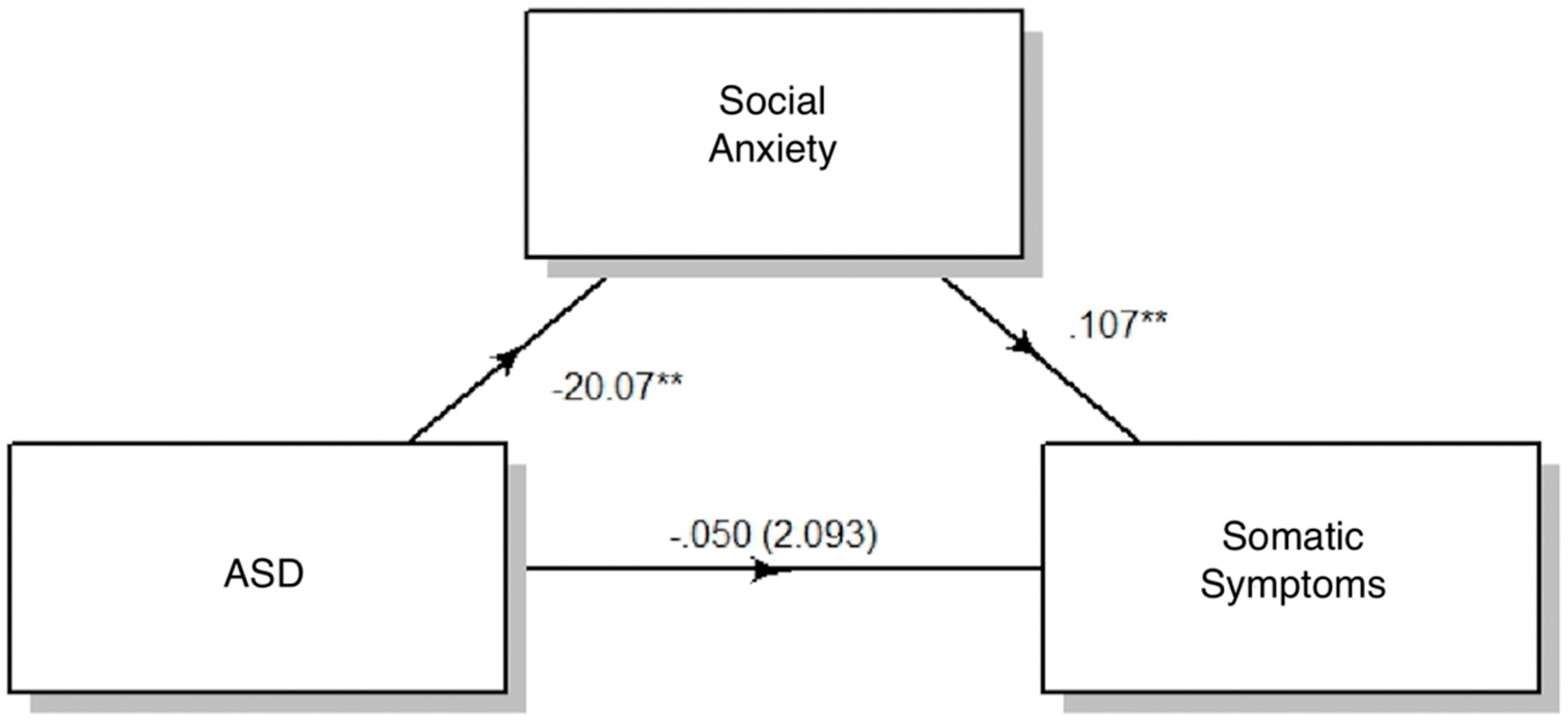

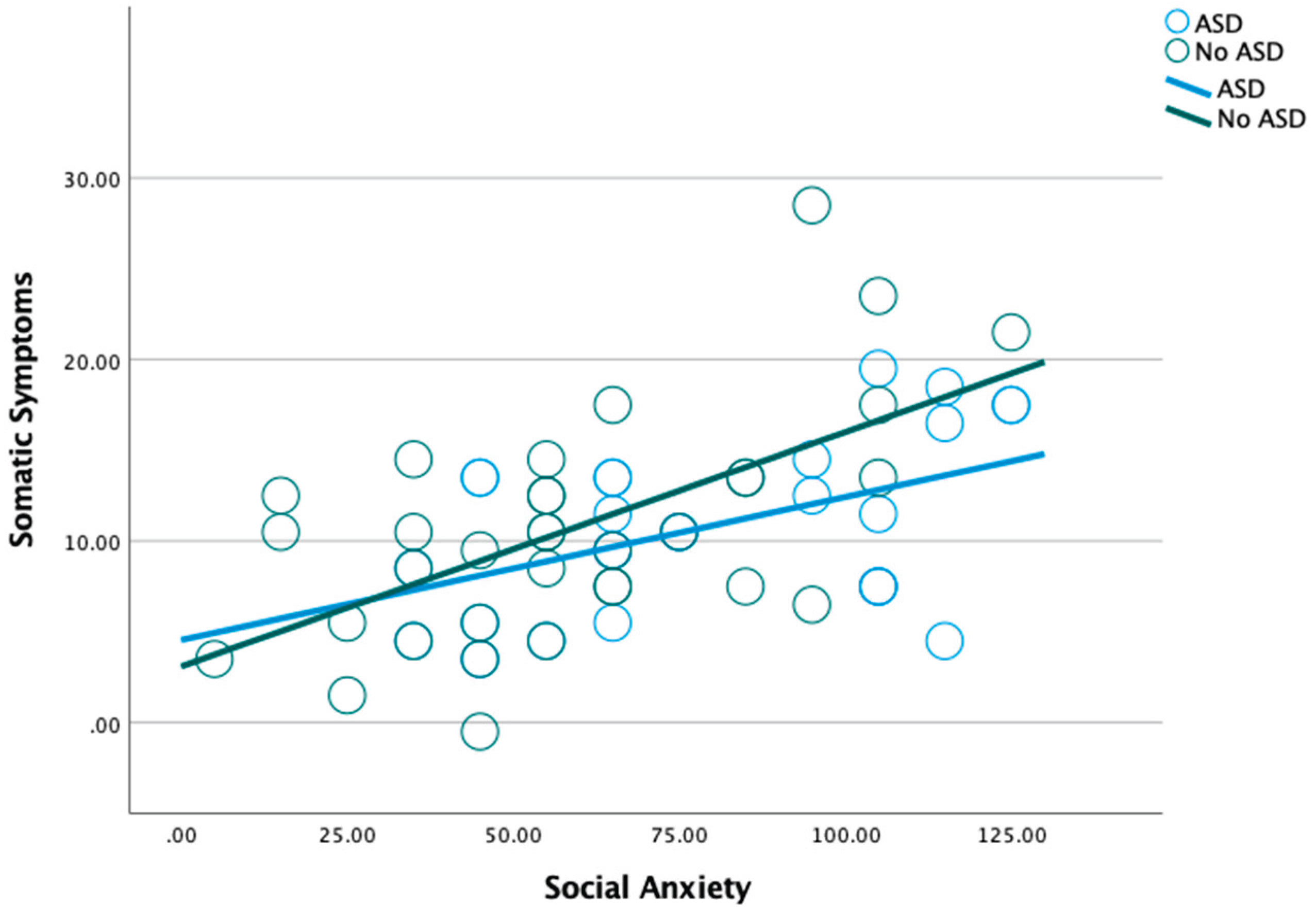

The major findings from this study that align with our hypotheses include the findings that participants with ASD did have higher social anxiety levels. Higher social anxiety levels were also correlated with higher somatic symptoms, as predicted. Interestingly, social anxiety was more strongly correlated with somatic symptoms for individuals without ASD, although not significantly; regardless, social anxiety levels still contributed to the relationship for both groups overall.

Our hypotheses that individuals with ASD would have lower social cognitive skills and higher somatic symptoms were not supported, distinct from previous findings examining social cognitive skills [16, 17] and somatic health [

23] in individuals with ASD. The hypothesis that social cognition would mediate the relationship between autism and both social anxiety and somatic symptoms was also not supported by our findings, once again inconsistent with previous findings [3, 5, 24]. In fact, our measurement for social cognition did not correlate with autism, social anxiety, nor somatic symptoms.

These findings suggest that the aspect of social cognition applied in this study (measured by the DANVA-2), given its limited scope in seeking visual-facial emotion recognition (matching pictured face to verbal label) does not contribute to the higher levels of social anxiety in individuals with ASD. It is important to note that the partial application of the DANVA-2 (not applying the prosodic/auditory portion), only measures one aspect of social cognition, and other aspects of social cognition, such as determining the purpose behind another’s actions or predicting the emotions or actions of others, likely do apply to the relationship between ASD and social anxiety. Since social anxiety levels were higher in individuals with ASD, this would suggest that other factors may be mediating this effect; other studies have found intolerance of uncertainty, alexithymia, and sensory hypersensitivity to be significant mediators between ASD and social anxiety [

29]. The findings that the social cognitive differences assessed are not contributing to increased somatic symptoms leave other social cognitive factors in need of exploration. Additional factors contributing to the somatic health problems seen more so in individuals with ASD [

23] also invite further study based upon prior findings. Alexithymia and emotion dysregulation were associated with somatoform disorders, although this was true for both individuals with and without ASD. However, researchers did find that for individuals with ASD, interoceptive sensibility was more strongly linked to somatoform disorders compared to individuals without ASD [

30].

Findings also suggest that the presence of social anxiety symptoms significantly changes the relationship between a diagnosis of ASD and somatic symptoms, with the presence of social anxiety decreasing the relationship between an ASD diagnosis and somatic symptomology and increasing the relationship between having no ASD diagnosis and somatic symptomology. This suggests that additional factors not measured in this study, such as interoceptive sensibility, are contributing to the overall higher somatic symptoms in individuals with ASD more so than individuals without ASD [

30], while social anxiety can be attributed to having a slightly larger effect on the presence of somatic symptoms in the non-ASD population, as supported by our moderation analysis. The finding of a notable sex difference in post-hoc analysis, indicating that the correspondence between social anxiety (LSAS) and somatic symptomatology (PHQ) was only true for females subjects, and not males with ASD also suggests that for males with ASD specifically, something other than social anxiety is contributing to somatic symptoms more so than other populations, while highlighting that social anxiety affects the somatic well-being of females with ASD more so than their male counterparts. A review on sex-differences in anxiety disorders suggests that females with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) experience more somatic symptoms than males with GAD and describes that females tend to experience internalization of their problems more than men [

31]. Both anxiety and somatization are internalization problems. It is also therefore possible that due to the distress caused by social anxiety, women with ASD tend to internalize their distress into somatic symptoms more so than men with ASD. As this was not the focus of our study, and research on these sex differences particularly within the ASD population is sparse; thus, this finding calls for more research examining sex differences between somatization of anxiety in people with ASD. Clinical/therapeutic implications would follow from understanding that the link between social anxiety and somatic health is distinct in males and females with ASD.

Regarding practical applications of the data, the results suggest that social anxiety levels could be a promising factor to focus on treating individuals, both with and without ASD, who present with somatic symptoms. An important component of Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of social anxiety focuses on teaching patients to recognize when somatic symptoms are related to or resulting from their anxiety and how to alleviate such symptoms along with relieving their anxiety [

32]. There are not many papers assessing the reduction of somatic symptoms in anxiety treatments for the ASD population specifically. While Spek et al. [

33] found that similar Mindfulness Based Treatments have reduced a number of co-occurring symptoms including both anxiety and somatic symptoms simultaneously, it is hard to determine the connection or causal relationship between somatic and anxiety symptoms in this study. While we hypothesized that social cognitive differences would contribute to the social anxiety levels and somatic symptoms, the facet of social cognition that was measured in this study did not appear to contribute, suggesting that focusing on compensating for or increasing visual emotion recognition will not be effective in treating social anxiety or somatic symptoms in either population. Other studies have found associations between additional social cognitive skills, namely theory of mind; most studies find stronger correlations between empathic accuracy (which pertains to predicting how a character would feel in a certain scenario), and theory of mind tasks (which pertain to inferring the mental state, desires, and intentions of another person), as opposed to purely visual emotion recognition tasks [14, 15]. The current finding also does not align with previous studies that have found social cognitive skills training helps reduce social anxiety in young people with ASD [

34].

Limitations

This study had several limitations that may explain why our findings differed from previous research. Notably, neither social cognition nor somatic symptoms were significantly correlated with an ASD diagnosis. This may be due to limited sensitivity in the measures used and the sample of participants who inherently must be able to read and use a computer independently, which could have reduced detectable group differences. Prior research suggests that some social cognition measures have weaker reliability in non-clinical samples, and that face/emotion processing tasks—used here—tend to show smaller effects than mentalizing tasks, requiring larger samples to detect differences [

35]. Additionally, we did not include other social cognition measures like dynamic facial emotion tasks, social relationship vignettes, or theory of mind assessments, which may have been more sensitive [

35], nor did we measure identification of nonverbal emotional messaging such as prosodic sensitivity [

36,

37].

The measurement for somatic symptoms may also have been too broad; perhaps specific somatic symptoms are more common in individuals with ASD, however the measurement used for this study may have been inadequate significantly demonstrate differences between those with and without ASD, although the PHQ has been suggested as a useful measurement for assessing somatic symptoms in individuals with and without autism [

38].

Another limitation was the small sample size (N = 61), which limited statistical power. Additionally, all ASD diagnoses were self-reported and not independently verified, and we did not assess for varying trait levels. Since participants needed sufficient reading and cognitive ability to complete the study, our ASD sample likely skewed toward individuals who can read and use their computer independently, limiting generalizability. It is possible that larger differences in social cognitive skills and somatic symptoms would have been found if our study had more variance in the presentation of ASD. Due to the nature of social cognition measurements and self-reported somatic symptom measurements, literature on the correlation to the severity of one’s autism with their social cognitive differences and somatic symptomology is scarce.

An additional methodological consideration involves the use of online survey data to collect responses for this study. One strength of online surveys is that they can increase accessibility and participation, especially among populations who may face challenges with in-person participation, such as individuals with ASD. Online platforms allow for flexible timing, anonymity, and reduced social pressures, which can be particularly helpful when collecting data on sensitive topics like social anxiety and somatic symptoms. Online formats can also streamline data collection across a wide sample reach, increasing generalizability [

39]. However, this approach has limitations. It precludes the ability to verify ASD diagnoses through clinical records or standardized diagnostic tools, relying instead on self-report, which may reduce diagnostic accuracy. Additionally, environmental distractions, lack of researcher oversight, and potential misunderstanding of survey instructions can compromise response validity. The use of online surveys also introduces a response bias, selecting only for participants who chose to respond [

39]. Response quality and attentiveness may vary, especially for longer surveys, and without a controlled setting, factors such as mood, fatigue, or external influences may bias responses. Finally, those who choose to participate in online surveys may not be representative of the broader ASD population, particularly those with more severe impairments or lower access to technology, which can introduce sampling bias.

Future research should explore whether other forms of anxiety, beyond social anxiety, contribute to somatic symptoms in ASD. It would also be useful to examine different subtypes of social anxiety and their relation to autism and specific somatic complaints. Studying distinct somatic symptoms, rather than somatic symptomology as a whole, could help identify which are most relevant to ASD and more amenable to treatment. Additionally, future work should include participants with a broader range of ASD traits to better understand how these factors interact with anxiety, social cognition, and somatic symptoms.