Submitted:

09 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Design

2.2. Participants

- Children with ASD: Fifteen children (ages 6–12 years) diagnosed by qualified physicians and psychologists, enrolled at the Jude Institute for Special Education (Ramallah and Al-Bireh, Palestine). From this population, ten children were purposively selected based on inclusion criteria: confirmed diagnosis of moderate ASD, regular attendance, absence of additional physical or cognitive impairments, ability to participate in training, and presence of clear motor behavior challenges.

- Caregivers: Ten female caregivers working at the same institute, all with direct daily contact with the selected children were recruited via comprehensive sampling to assess psychological variables via questionnaires.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Variables

- Independent Variable: Recreational training units program.

-

Dependent Variables:

- ⚬

- Psychological variables: Aggressive behavior, irrational behavior, and social communication.

- ⚬

- Motor behaviors: Eight of the most common stereotypical behaviors among the sample, identified via preliminary observation and video analysis (spinning in circles, hand flapping, repetitive clapping, jumping in place, rocking back and forth, repetitive foot tapping, covering ears when exposed to loud sounds, inappropriate object use).

2.5. Instruments

- Psychological Variables Scale: Adapted from recently published studies, containing 21 negatively worded items across three subscales (aggressive behavior, irrational behavior, social communication). Responses were rated on a 3-point Likert scale: always (3), sometimes (2), rarely (1) [31,32,33]. Content validity was confirmed by expert review, and reliability coefficients (ICC) ranged from 0.89 to 0.95.

- Motor Behavior Observation Protocol: Developed through a three-phase process—review of institutional behavioral records, direct classroom observation, and CCTV video analysis. Inter-rater reliability (ICC) ranged from 0.88 to 0.94 across behaviors.

2.6 Intervention – Recreational Training Units Program

- Warm-up (12 min): Story-based movement activities to engage attention.

- Main part (40 min): Targeted physical and play-based exercises designed to reduce specific motor stereotypies, incorporating progressive difficulty and variety (e.g., balancing games, guided ball activities, interactive group tasks).

- Cool-down (8 min): Breathing and relaxation exercises.

2.7. Pilot Study

2.8. Data Collection Procedures

-

Pre-test:

- ⚬

- Psychological variables: caregiver questionnaires administered on 10 March 2025.

- ⚬

- Motor behaviors: video-recorded observation sessions from 3–9 March 2025, one hour/day for seven days.

- Intervention: Implementation of the recreational units from 11 March to 11 May 2025.

-

Post-test:

- ⚬

- Psychological variables: questionnaires administered on 12 May 2025.

- ⚬

- Motor behaviors: video-recorded observation sessions from 12–21 May 2025, identical in timing and duration to pre-test procedures.

2.9. Equipment and Materials

- Physical activity equipment: plastic balls (n=10), small colored balls (n=10), balloons (various sizes/colors), hoops (various sizes/colors), adhesive tapes (5 cm width, various colors), whistle (n=1), building blocks (LEGO), double-surface exercise mats (n=2), chalk, measuring tape.

- Recording and timing devices: two Smart Cameras for continuous observation, stopwatch, medical scale, Casio calculator.

2.10. Reliability and Validity

2.11. Data Analysis

2.12. Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI)

3. Results

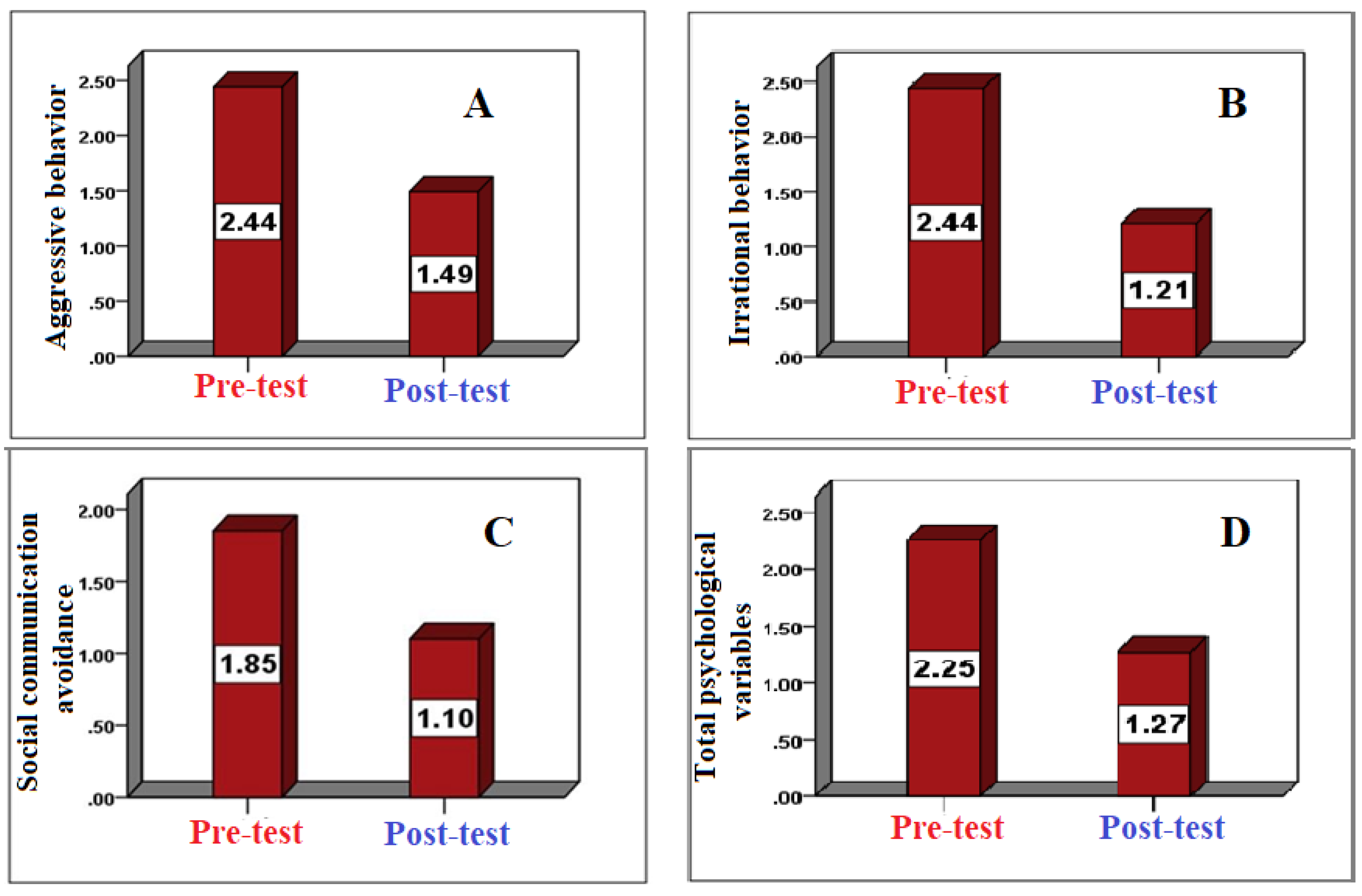

3.1. Psychological Variables

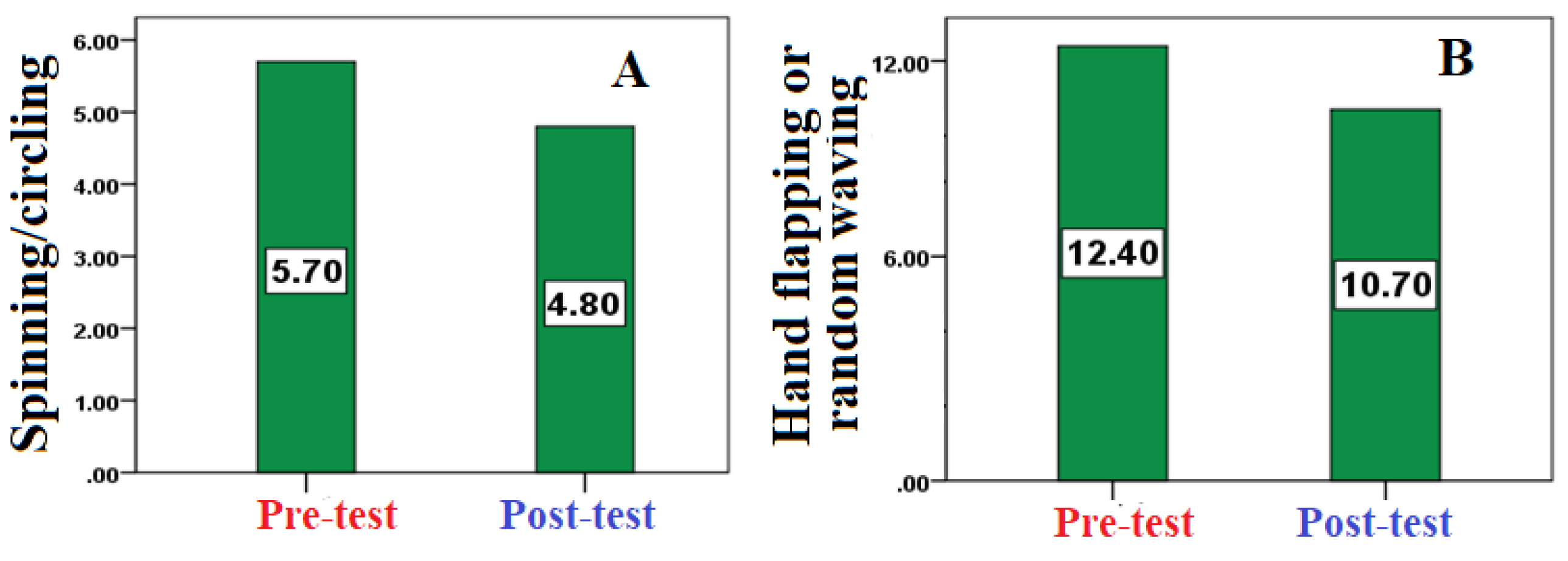

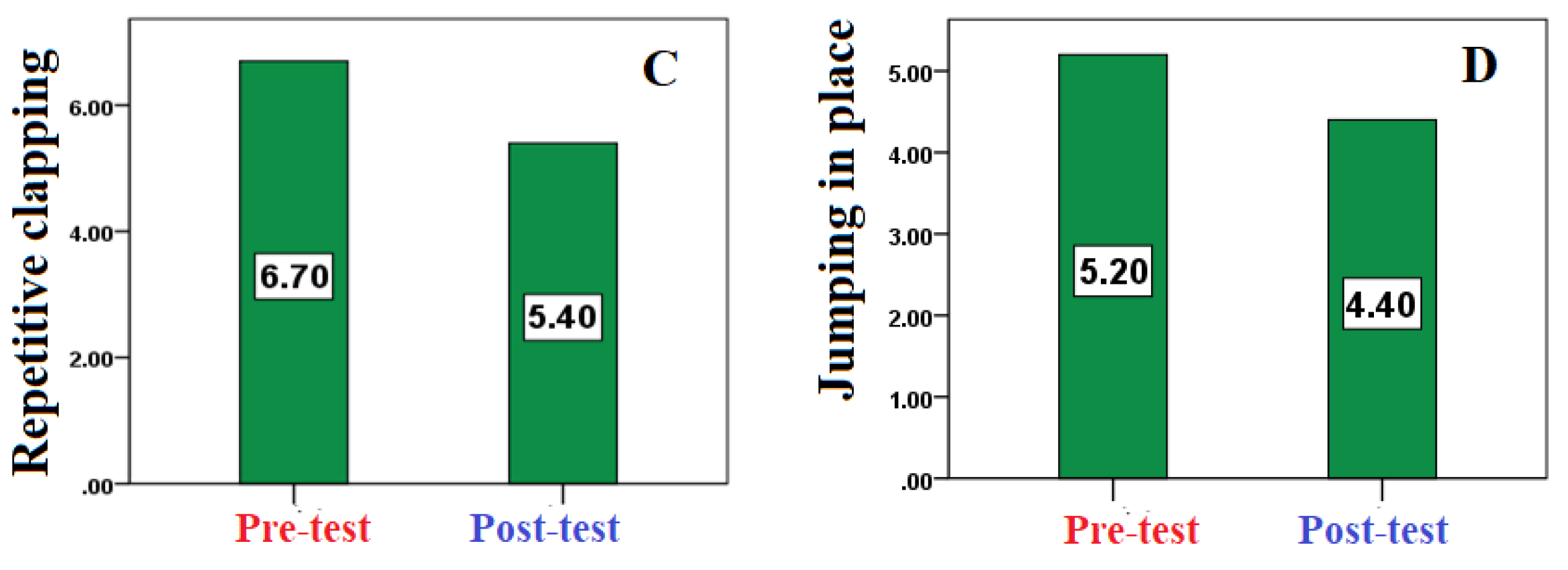

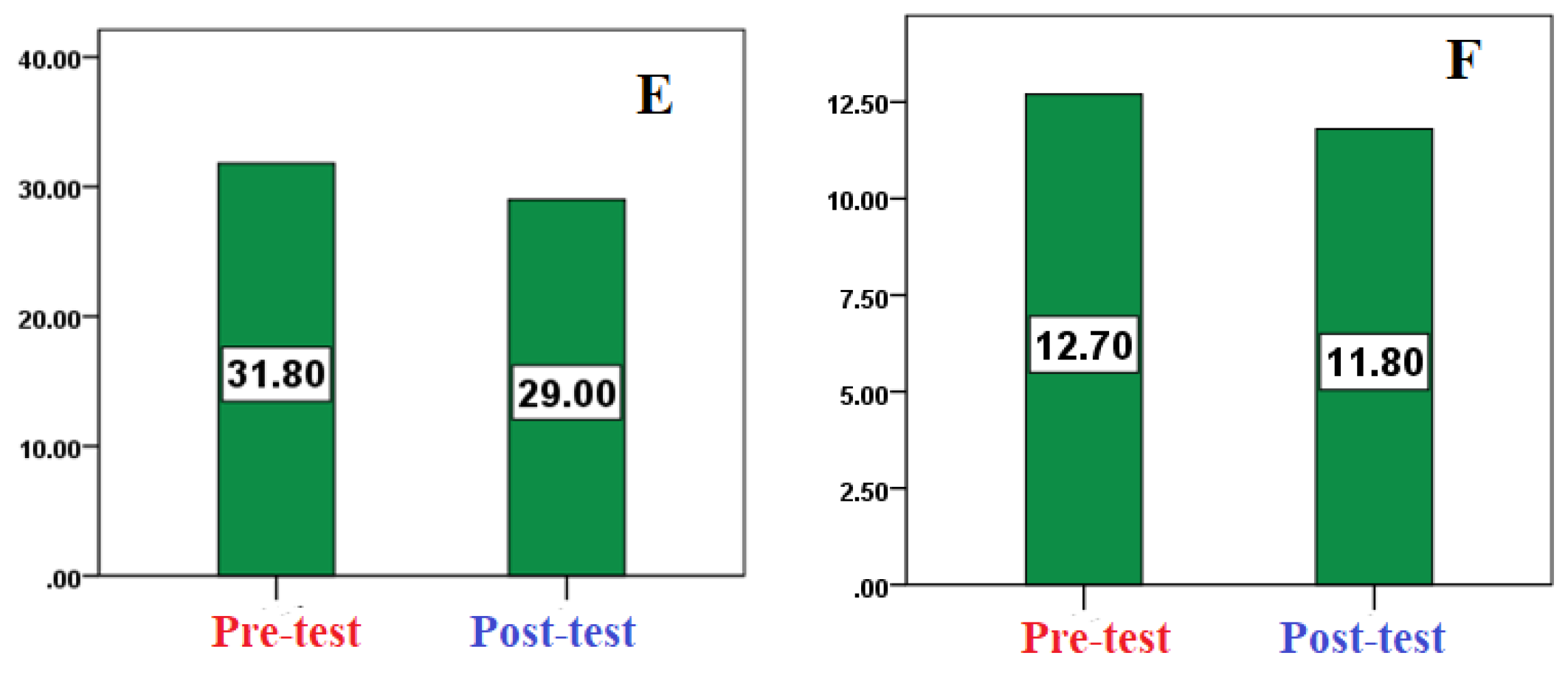

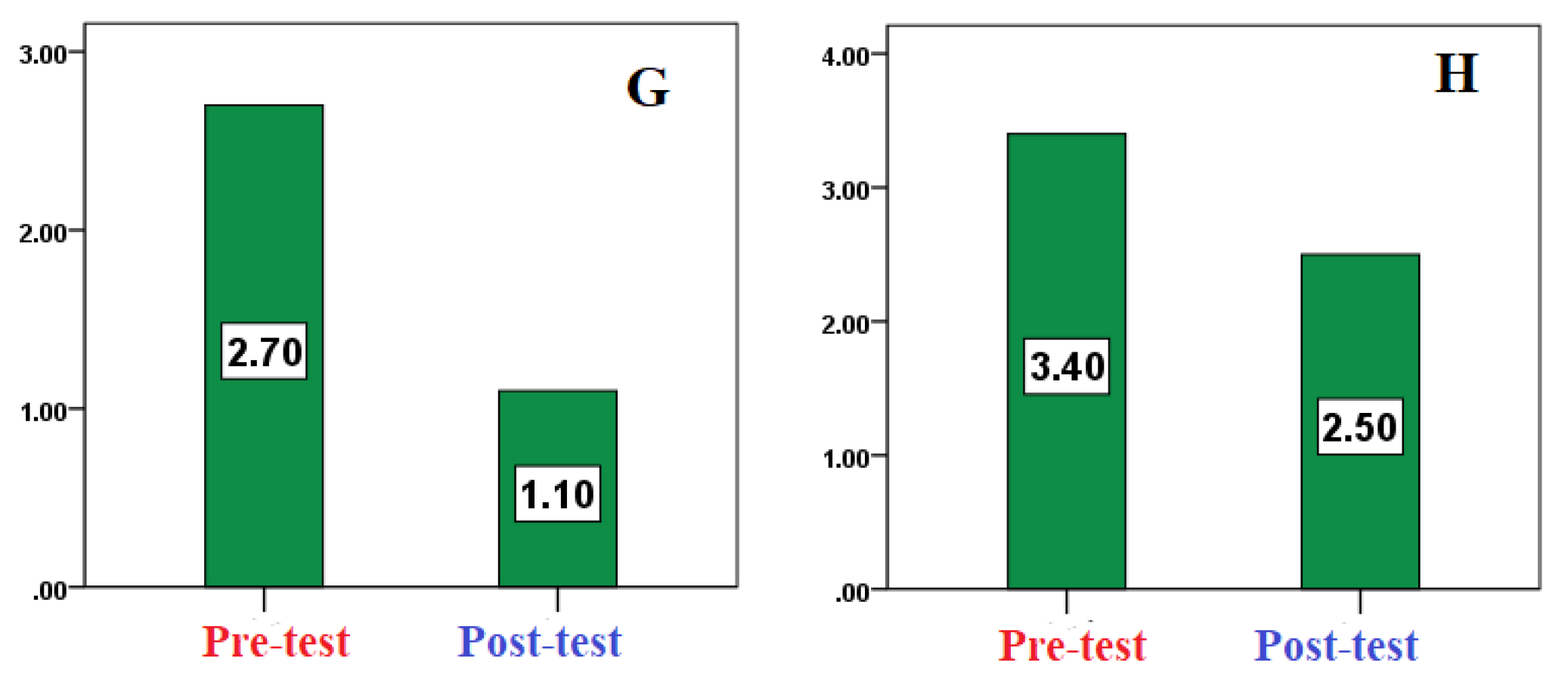

3.2. Motor Behaviors

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychological Outcomes

4.2. Motor Behavior Outcomes

4.3. Broader Implications

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| CCTV | Closed-Circuit Television |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Robert Jason Grant. Chapter 13: Play Therapy for Children with autism Spectrum Disorder. In Prescriptive play therapy : tailoring interventions for specific childhood problems; The Guilford Press: New York, United States of America, 2019; pp 213–230.

- Natasha Marrus; John Constantino. Chapter 8: Autism Spectrum Disorder. In Handbook of Preschool Mental Health: Development, Disorders, and Treatment; The Guilford Press: New York, United States of America, 2016; pp 187–219.

- DAWN LEE GARZON; NANCY BARBER STARR; JENNIFER CHAUVIN. Chapter 29: Neurodivergence and Behavioral and Mental Health Disorders. In Burns’ Pediatric Primary Care; Evolve-Elsevier, 2024; pp 419–455.

- S, J.; Arumugam, N.; Parasher, R. K. Effect of physical exercises on attention, motor skill and physical fitness in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders 2018, 11 (2), 125–137. [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.-Y.; Tsai, C.-L.; Chu, C.-H.; Sung, M.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Ma, W.-Y. Effects of physical exercise intervention on motor skills and executive functions in children with ADHD: a pilot study. Journal of Attention Disorders 2015, 23 (4), 384–397. [CrossRef]

- Bucik, K.; Vitulić, H. S.; Pavel, J. R. Effects of dance-movement therapy on the movement and self-concept of wheelchair users with intellectual disabilities. Hrvatska Revija Za Rehabilitacijska Istraživanja 2023, 59 (1), 59–76. [CrossRef]

- Reed, A. S. Mental health, availability to participate in social change, and social movement accessibility. Social Science & Medicine 2022, 313, 115389. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, R. Systematic review and randomized controlled trial meta-analysis of the effects of physical activity interventions and their components on repetitive stereotyped behaviors in patients with autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Psychology 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. P.; Ghiarone, T.; Júnior, C. R. C.; Furtado, G. E.; Carvalho, H. M.; Machado-Rodrigues, A. M.; Toscano, C. V. A. Effects of Physical Exercise on the Stereotyped Behavior of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Medicina 2019, 55 (10), 685. [CrossRef]

- Menggo, S.; Ndiung, S.; Midun, H. Integrating 21st-century skills in English material development: What do college students really need? Englisia Journal of Language Education and Humanities 2022, 9 (2), 165. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; You, Y.; Zhou, J. The impact of long-term exercise on motor skills in children with ADHD: a three-level meta-analysis. BMC Pediatrics 2025, 25 (1). [CrossRef]

- Ziereis, S.; Jansen, P. Effects of physical activity on executive function and motor performance in children with ADHD. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2015, 38, 181–191. [CrossRef]

- Kruger, G. R.; Silveira, J. R.; Marques, A. C. Motor skills of children with autism spectrum disorder. Brazilian Journal of Kinanthropometry and Human Performance 2019, 21. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C. E.; Da Silva, E.; Sodré, R.; Costa, F.; Trindade, A. S.; Bunn, P.; Silva, G. C. E.; Di Masi, F.; Dantas, E. The Effect of Physical Activity on Motor Skills of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19 (21), 14081. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, G.; Abdelbaky, A.; Adly, A.; Ezzat, D.; Hakeem, G. A.; Hassab, H.; Youssry, I.; Ragab, I.; Sherief, L. M.; Zakaria, M.; Hesham, M.; Salama, N.; Salah, N.; Afifi, R. a. A.; El-Ashry, R.; Makkeyah, S.; Adolf, S.; Amer, Y. S.; Omar, T. E. I.; Bussel, J.; Raouf, E. A. E.; Atfy, M.; Ellaboudy, M.; Florez, I. Egyptian Pediatric Guidelines for the Management of Children with Isolated Thrombocytopenia Using the Adapted ADAPTE Methodology—A Limited-Resource Country Perspective. Children 2024, 11 (4), 452. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, A. E.; Cervin, M.; Piqueras, J. A. Relationships between emotion regulation, social communication and repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2021, 52 (10), 4519–4527. [CrossRef]

- Ilkim, M.; Tanir, H.; Özdemi̇R, M.; Bozkurt, İ. The Effect of Physical Activity on Level of Anger among Individuals with Autism. Turkish Journal of Sport and Exercise 2018, 130–135. [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Wu, Z. The impact of sensory integration based sports training on motor and social skill development in children with autism spectrum disorder. Scientific Reports 2025, 15 (1). [CrossRef]

- Wuang, Y.-P.; Huang, C.-L.; Tsai, H.-Y. Sensory integration and perceptual-motor profiles in school-aged children with autistic spectrum disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2020, Volume 16, 1661–1673. [CrossRef]

- Ezzdine, L. B.; Dhahbi, W.; Dergaa, I.; Ceylan, H. İ.; Guelmami, N.; Saad, H. B.; Chamari, K.; Stefanica, V.; Omri, A. E. Physical activity and neuroplasticity in neurodegenerative disorders: a comprehensive review of exercise interventions, cognitive training, and AI applications. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2025, 19. [CrossRef]

- Al-Wardat, M.; Salimei, C.; Alrabbaie, H.; Etoom, M.; Khashroom, M.; Clarke, C.; Almhdawi, K. A.; Best, T. Exploring the Links between Physical Activity, Emotional Regulation, and Mental Well-Being in Jordanian University Students. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13 (6), 1533. [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, N.; Hamdadou, D. A multicriteria group decision support system. In IGI Global eBooks; 2021; pp 107–133. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Pang, H. Impact of Short-Duration aerobic exercise intensity on executive function and sleep. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.09077.

- Masri, A. T.; Nasir, A. K.; Irshaid, A. G.; Irshaid, F. Y.; Alomari, F. K.; Khatib, F. A.; Al-Qudah, A. A.; Nafi, O. A.; Almomani, M. A.; Bashtawi, M. A. Autism services in low-resource areas. Neurosciences 2023, 28 (2), 116–122. [CrossRef]

- Meimand, S. E.; Amiri, Z.; Shobeiri, P.; Malekpour, M.; Moghaddam, S. S.; Ghanbari, A.; Tehrani, Y. S.; Varniab, Z. S.; Langroudi, A. P.; Sohrabi, H.; Mehr, E. F.; Rezaei, N.; Moradi-Lakeh, M.; Mokdad, A. H.; Larijani, B. Burden of autism spectrum disorders in North Africa and Middle East from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Brain and Behavior 2023, 13 (7). [CrossRef]

- Wahdan, M. M.; Malak, M. Z.; Al-Amer, R.; Ayed, A.; Russo, S.; Berte, D. Z. Effect of incredible years autism spectrum and language delays (IY-ASD) program on stress and behavioral management skills among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder in Palestine. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2023, 72, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M. M. A.; Abusharkh, W.; Jundi, W. A. Factors Associated with Improvement of Autistic Spectrum Children on Different Behavior Therapy Programs. Journal of Adolescent and Addiction Research 2023, 2 (1). [CrossRef]

- Autism Superhero Palestine, programs and activities. https://www.autismsuperpali.org (accessed 2025-09-03).

- Gaza Community Mental Health Programme. https://archive.unescwa.org/gaza-community-mental-health-programme (accessed 2025-09-03).

- Assaf, M.; Al-Hayeh, H. Family Culture in Dealing with Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (Analytical Study). jes.ejournal.unri.ac.id 2024, 534–546. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.-Z. The effect of a psychomotor program on the degree of Self-Concept of the mentally handicapped. Assiut Journal of Sport Science and Arts /Assiut Journal of Sport Science and Arts 2020, 2020 (1), 112–122. [CrossRef]

- Vandoni, M.; Giuriato, M.; Pirazzi, A.; Zanelli, S.; Gaboardi, F.; Pellino, V. C.; Gazzarri, A. A.; Baldassarre, P.; Zuccotti, G.; Calcaterra, V. Motor Skills and Executive Functions in Pediatric Patients with Down Syndrome: A Challenge for Tailoring Physical Activity Interventions. Pediatric Reports 2023, 15 (4), 691–706. [CrossRef]

- Maryam, T. M. S.; Poushaneh, K.; Akbar, K. B. A.; Reza, R. Z. H. Citizenship Education Curriculum for Students with Special Needs. lss.artahub.ir 2023. [CrossRef]

- Skavås, M. R.; Rognlid, M.; Kildahl, A. N. Case study: bipolar disorder and catatonia in an adult autistic male with intellectual disability and Phelan-McDermid syndrome (22q13.33 deletion syndrome): psychopharmacological treatment and symptom trajectories. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities 2024, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Novitski, P., I. Special olympics movement for persons with intellectual disabilities. https://rep.vsu.by/handle/123456789/33711.

- Toscano, C. V. A.; Barros, L.; Lima, A. B.; Nunes, T.; Carvalho, H. M.; Gaspar, J. M. Neuroinflammation in autism spectrum disorders: Exercise as a “pharmacological” tool. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2021, 129, 63–74. [CrossRef]

- Sarabzadeh, M.; Azari, B. B.; Helalizadeh, M. The effect of six weeks of Tai Chi Chuan training on the motor skills of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2019, 23 (2), 284–290. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Chen, S. The Effects of Structured Physical Activity Program on Social Interaction and Communication for Children with Autism. BioMed Research International 2018, 2018, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, L.; Cordier, R.; Munro, N.; Joosten, A. A randomized controlled trial of a Play-Based, Peer-Mediated pragmatic language intervention for children with autism. Frontiers in Psychology 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Tse, C. Y. A.; Pang, C. L.; Lee, P. H. Choosing an Appropriate Physical Exercise to Reduce Stereotypic Behavior in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Non-randomized Crossover Study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2017, 48 (5), 1666–1672. [CrossRef]

- Kamio, Y.; Haraguchi, H.; Miyake, A.; Hiraiwa, M. Brief report: large individual variation in outcomes of autistic children receiving low-intensity behavioral interventions in community settings. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2015, 9 (1). [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, L.; Smith, E. R.; Barlow, J.; Livingstone, N.; Herath, N. I.; Wei, Y.; Spreckelsen, T. F.; Macdonald, G. Video feedback for parental sensitivity and attachment security in children under five years. Cochrane Library 2019, 2019 (11). [CrossRef]

- Bagaiolo, L. F.; Bordini, D.; Da Cunha, G. R.; Sasaki, T. N. D.; Nogueira, M. L. M.; Pacífico, C. R.; Braido, M. Implementing a community-based parent training behavioral intervention for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Psicologia - Teoria E Prática 2019, 21 (3). [CrossRef]

- Kreslins, A.; Robertson, A. E.; Melville, C. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2015, 9 (1). [CrossRef]

- Vivanti, G.; Kasari, C.; Green, J.; Mandell, D.; Maye, M.; Hudry, K. Implementing and evaluating early intervention for children with autism: Where are the gaps and what should we do? Autism Research 2017, 11 (1), 16–23. [CrossRef]

- Pickles, A.; Couteur, A. L.; Leadbitter, K.; Salomone, E.; Cole-Fletcher, R.; Tobin, H.; Gammer, I.; Lowry, J.; Vamvakas, G.; Byford, S.; Aldred, C.; Slonims, V.; McConachie, H.; Howlin, P.; Parr, J. R.; Charman, T.; Green, J. Parent-mediated social communication therapy for young children with autism (PACT): long-term follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2016, 388 (10059), 2501–2509. [CrossRef]

- Madden, J. M.; Lakoma, M. D.; Lynch, F. L.; Rusinak, D.; Owen-Smith, A. A.; Coleman, K. J.; Quinn, V. P.; Yau, V. M.; Qian, Y. X.; Croen, L. A. Psychotropic Medication Use among Insured Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2016, 47 (1), 144–154. [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, M.; Baxter, J.; Grayson, Z.; Johnston, L.; O’Hare, A. Visual supports at home and in the community for individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A scoping review. Autism 2019, 24 (2), 447–469. [CrossRef]

- McCambridge, J.; Witton, J.; Elbourne, D. R. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2013, 67 (3), 267–277. [CrossRef]

- Dolan, B. K.; Van Hecke, A. V.; Carson, A. M.; Karst, J. S.; Stevens, S.; Schohl, K. A.; Potts, S.; Kahne, J.; Linneman, N.; Remmel, R.; Hummel, E. Brief Report: Assessment of Intervention Effects on In Vivo Peer Interactions in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2016, 46 (6), 2251–2259. [CrossRef]

- Amal AL Nadaf. A Proposed Strategy for Developing Professional Services Provided to Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder Fromthe Perspective of Service Providers in Jordan. Zanco Journal of Humanity Sciences 2024, 28 (s3). [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Hamshere, M. L.; Stergiakouli, E.; O’Donovan, M. C.; Thapar, A. Neurocognitive abilities in the general population and composite genetic risk scores for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2014, 56 (6), 648–656. [CrossRef]

- Madden, J. M.; Lakoma, M. D.; Lynch, F. L.; Rusinak, D.; Owen-Smith, A. A.; Coleman, K. J.; Quinn, V. P.; Yau, V. M.; Qian, Y. X.; Croen, L. A. Psychotropic Medication Use among Insured Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2016, 47 (1), 144–154. [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.; Auyeung, B.; Wang, X.; Lin, L.; Li, H.; Zhan, X.; Jin, C.; Jing, J.; Li, X. Empathizing, systemizing, empathizing-systemizing difference and their association with autistic traits in children with autism spectrum disorder, with and without intellectual disability. Autism Research 2022, 15 (7), 1348–1357. [CrossRef]

- Divan, G.; Hamdani, S. U.; Vajartkar, V.; Minhas, A.; Taylor, C.; Aldred, C.; Leadbitter, K.; Rahman, A.; Green, J.; Patel, V. Adapting an evidence-based intervention for autism spectrum disorder for scaling up in resource-constrained settings: the development of the PASS intervention in South Asia. Global Health Action 2015, 8 (1), 27278. [CrossRef]

- Divan, G.; Vajaratkar, V.; Cardozo, P.; Huzurbazar, S.; Verma, M.; Howarth, E.; Emsley, R.; Taylor, C.; Patel, V.; Green, J. The Feasibility and Effectiveness of PASS Plus, a lay health worker delivered comprehensive intervention for autism spectrum disorders: pilot RCT in a rural low and middle income country setting. Autism Research 2018, 12 (2), 328–339. [CrossRef]

- Sandbank, M.; Bottema-Beutel, K.; Crowley, S.; Cassidy, M.; Dunham, K.; Feldman, J. I.; Crank, J.; Albarran, S. A.; Raj, S.; Mahbub, P.; Woynaroski, T. G. Project AIM: Autism intervention meta-analysis for studies of young children. Psychological Bulletin 2019, 146 (1), 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Eapen, V.; Črnčec, R.; Walter, A. Clinical outcomes of an early intervention program for preschool children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in a community group setting. BMC Pediatrics 2013, 13 (1). [CrossRef]

- Paynter, J.; Trembath, D.; Lane, A. Differential outcome subgroups in children with autism spectrum disorder attending early intervention. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2018, 62 (7), 650–659. [CrossRef]

- Bremer, E.; Crozier, M.; Lloyd, M. A systematic review of the behavioural outcomes following exercise interventions for children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2016, 20 (8), 899–915. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Liang, Z.; Ma, G.; Qureshi, A.; Ran, X.; Feng, C.; Liu, X.; Yan, X.; Shen, L. Autism spectrum disorder: pathogenesis, biomarker, and intervention therapy. MedComm 2024, 5 (3). [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Gresa, P.; Gil-Gómez, H.; Lozano-Quilis, J.-A.; Gil-Gómez, J.-A. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality for Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Evidence-Based Systematic Review. Sensors 2018, 18 (8), 2486. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ding, H.; Naumceska, M.; Zhang, Y. Virtual Reality Technology as an Educational and Intervention Tool for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Current Perspectives and Future Directions. Behavioral Sciences 2022, 12 (5), 138. [CrossRef]

- Sokołowska, B. Being in Virtual Reality and its Influence on Brain Health—An Overview of Benefits, Limitations and Prospects. Brain Sciences 2024, 14 (1), 72. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, G. G.; Newbutt, N. N.; Lorenzo-Lledó, A. A. Designing virtual reality tools for students with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies 2023, 28 (8), 9557–9605. [CrossRef]

- Shire, S. Y.; Shih, W.; Bracaglia, S.; Kodjoe, M.; Kasari, C. Peer engagement in toddlers with autism: Community implementation of dyadic and individual Joint Attention, Symbolic Play, Engagement, and Regulation intervention. Autism 2020, 24 (8), 2142–2152. [CrossRef]

- Elbeltagi, R.; Al-Beltagi, M.; Saeed, N. K.; Alhawamdeh, R. Play therapy in children with autism: Its role, implications, and limitations. World Journal of Clinical Pediatrics 2023, 12 (1), 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Dückers, M. L. A.; Witteveen, A. B.; Bisson, J. I.; Olff, M. The association between disaster vulnerability and post-disaster psychosocial service delivery across Europe. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 2015, 44 (4), 470–479. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.; Oosterbeek, M.; Tummers, L. G.; Noordegraaf, M.; Yzermans, C. J.; Dückers, M. L. A. The organization of post-disaster psychosocial support in the Netherlands: a meta-synthesis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 2019, 10 (1). [CrossRef]

- Chan, J. C. N.; Lim, L.-L.; Wareham, N. J.; Shaw, J. E.; Orchard, T. J.; Zhang, P.; Lau, E. S. H.; Eliasson, B.; Kong, A. P. S.; Ezzati, M.; Aguilar-Salinas, C. A.; McGill, M.; Levitt, N. S.; Ning, G.; So, W.-Y.; Adams, J.; Bracco, P.; Forouhi, N. G.; Gregory, G. A.; Guo, J.; Hua, X.; Klatman, E. L.; Magliano, D. J.; Ng, B.-P.; Ogilvie, D.; Panter, J.; Pavkov, M.; Shao, H.; Unwin, N.; White, M.; Wou, C.; W, R. C., MA; Schmidt, M. I.; Ramachandran, A.; Seino, Y.; Bennett, P. H.; Oldenburg, B.; Gagliardino, J. J.; Luk, A. O. Y.; Clarke, P. M.; Ogle, G. D.; Davies, M. J.; Holman, R. R.; Gregg, E. W. The Lancet Commission on diabetes: using data to transform diabetes care and patient lives. The Lancet 2020, 396 (10267), 2019–2082. [CrossRef]

- Pellicano, E.; Houting, J. D. Annual Research Review: Shifting from ‘normal science’ to neurodiversity in autism science. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2021, 63 (4), 381–396. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skewness |

| Age (years) | 8.43 | 1.9 | 0.12 |

| Height (cm) | 127.43 | 5.41 | -0.04 |

| Body Mass (kg) | 36.11 | 5.06 | -0.93 |

| Psychological Variable | ICC Reliability | Self-Validity |

| Aggressive behavior | 0.93* | 0.964 |

| Irrational behavior | 0.91* | 0.953 |

| Social communication | 0.89* | 0.943 |

| Overall scale | 0.95* | 0.974 |

| *Statistically significant at α ≤ 0.05 | ||

| Motor Behavior | ICC Reliability | Self-Validity |

| Spinning and circling (rotating around oneself) | 0.88* | 0.938 |

| Hand flapping or random waving | 0.93* | 0.964 |

| Repetitive clapping | 0.92* | 0.959 |

| Jumping up and down in the same spot | 0.91* | 0.953 |

| Rocking back and forth while sitting or standing | 0.89* | 0.943 |

| Repetitive foot tapping on the ground | 0.94* | 0.969 |

| Covering ears when hearing loud sounds or loud music | 0.90* | 0.948 |

| Inappropriate object use (e.g., breaking or damaging items) | 0.91* | 0.953 |

| *Statistically significant at α ≤ 0.05 | ||

| Psychological Variables | Pre-test Mean ± SD | Post-test Mean ± SD | t-value | Sig. (p) | % Change |

| Aggressive behavior | 2.44 ± 0.22 | 1.49 ± 0.12 | 10.3 | 0.000* | -38.93 |

| Irrational behavior | 2.44 ± 0.13 | 1.21 ± 0.22 | 13.91 | 0.000* | -50.4 |

| Social communication avoidance | 1.85 ± 0.39 | 1.10 ± 0.17 | 7.12 | 0.000* | -40.54 |

| Total score | 2.25 ± 0.14 | 1.27 ± 0.08 | 21.32 | 0.000* | -43.56 |

| *Significant at α ≤ 0.05. | |||||

| Motor Behaviors | Pre-test Mean ± SD | Post-test Mean ± SD | t-value | Sig. (p) | % Change |

| Spinning/circling (spinning around self) | 5.70 ± 1.89 | 4.80 ± 1.62 | 3.86 | 0.004* | -15.79 |

| Hand flapping or random waving | 12.40 ± 3.34 | 10.70 ± 2.83 | 4.64 | 0.001* | -13.39 |

| Repetitive clapping | 6.70 ± 1.89 | 5.40 ± 1.84 | 3.88 | 0.004* | -19.4 |

| Jumping in place | 5.20 ± 2.25 | 4.40 ± 2.07 | 3.21 | 0.011* | -15.38 |

| Rocking back and forth while sitting or standing | 31.80 ± 12.55 | 29.00 ± 12.07 | 5.47 | 0.000* | -8.8 |

| Repetitive foot tapping | 12.70 ± 2.41 | 11.80 ± 2.39 | 3.25 | 0.010* | -7.08 |

| Covering ears when exposed to loud sounds/music | 2.70 ± 1.34 | 1.10 ± 0.70 | 6 | 0.000* | -59.25 |

| Inappropriate object use (breaking/damaging items) | 3.40 ± 1.90 | 2.50 ± 1.65 | 3.25 | 0.010* | -26.47 |

| *Significant at α ≤ 0.05. | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).