Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2. Section I: Abdominal Paracentesis in Patients with Ascites

2.1. Indications [1,2,3,4]

- Diagnostic: Differentiate ascitic fluid based on the serum–ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) into high (> 1.1 g/dL) and low (< 1.1 g/dL) SAAG.

- Diagnostic evaluation for SBP or suspected hepatocellular carcinoma transformation

- Symptomatic ascites, such as tense ascites causing respiratory compromise or abdominal discomfort

- Refractory ascites requiring repeated therapeutic drainage

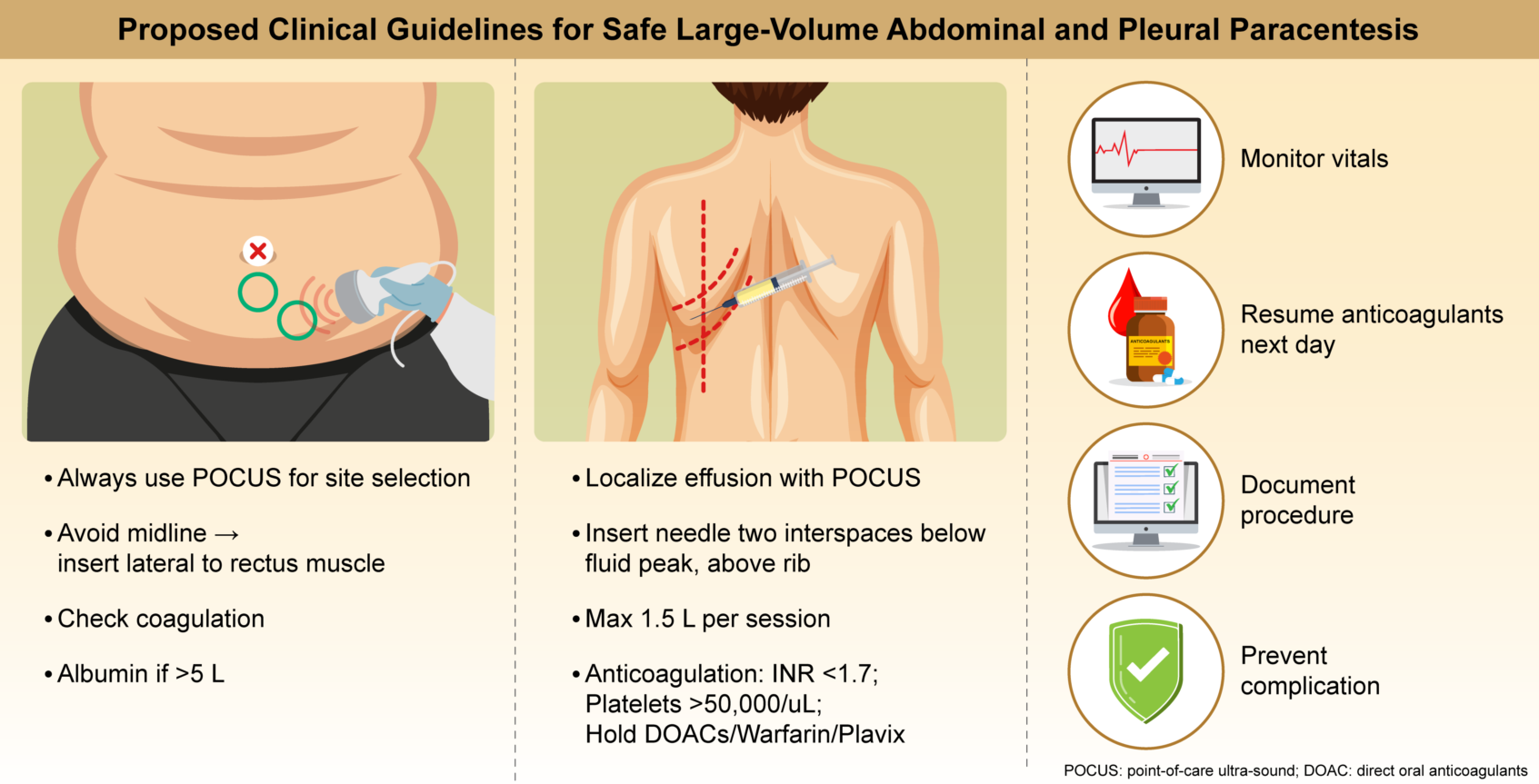

2.2. Clinical Recommendations for Peritoneal Paracentesis:

| Section | Recommendation |

| Preprocedural Recommendations | |

| Obtain verbal consent and document. Written consent should be obtained only if required by institutional policy. | |

| 2. First-Time Paracentesis | Provide a full explanation of the risks in the patient’s native language. Document the explanation, clinician’s name, and language used. |

| 3. Exclude Acute Infection | Postpone the procedure if active infection is suspected. |

| 4. Management of Anticoagulants | Warfarin: Stop 5 d prior; confirm INR <1.7. DOACs/ Clexane (LMWH): Skip the last dose before the procedure. |

| 5. Laboratory Testing in Suspected Coagulopathy | If no known coagulopathy exists and recent laboratory test results show a platelet count of >20 000/μL and INR <1.7, omit repeat tests. If platelet count is <20 000/μL: Administer 6 units of platelets (~5000/unit) [1]. If INR >1.7: Administer up to 3 units of FFP (~0.3 INR correction per unit) [1]. |

| 6. Aspirin | No need to withhold before procedure. |

| 7. Clopidogrel (Plavix) | Withhold for 72 h before drainage. |

| 8. Baseline Vitals | Record temperature, pulse, BP, and oxygen saturation. |

| Technique Recommendations | |

| 1. Ultrasound Guidance | Mandatory for all procedures. |

| 2. Needle Placement | Avoid the midline. Insert 8 cm lateral to the midline and 5 cm above the pubic symphysis or 2 cm below the umbilicus. |

| 3. Drainage System | Use either an 8F Seldinger kit or 18G cannula. |

| 4. Volume | No restriction on the amount of peritoneal fluid drained (unlike pleural effusion). |

| 5. Diagnostic Fluid Sampling | Always analyze fluid for cell count. If neutrophil count is >250/mm3 → suspect SBP. If a catheter is in place → perform culture testing. |

| 6. Device Options | Either an 8F Seldinger set or 18G peripheral catheter is acceptable. |

| 7. Initial/Diagnostic Studies | Analyze fluid for: cell count, culture, albumin, TP, amylase, BNP (optional), cytology. |

| 8. Albumin Administration |

Administer 8 g albumin for each 1 L of drainage (only >5 L) (to prevent paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction) |

| Postparacentesis Care | |

| 1. Observation | Monitor patients for 1 h after catheter removal |

| 2. Bed Rest | Keep patient in bed for the first 30 min postremoval. |

| 3. Discharge Criteria | Discharge only after documentation of stable BP and HR. Ensure parameters are recorded. |

| 4. Leakage from Site . |

If leakage occurs, place a pressure bandage. If leakage does not stop, a single suture may be placed. Remove suture after 1 week. |

| 5. Resuming Anticoagulation | Resume anticoagulants (including clopidogrel) the day after the procedure. |

| Bleeding Management | |

| 1. Bloody Aspirate | Serosanguinous initial fluid is acceptable. If bloody fluid follows clear drainage → stop immediately. If the initial aspirate is blood → abort and remove the catheter. |

| 2. Bleeding Response | a. Monitor for 4 h with vitals assessed every hour. b. Repeat hemoglobin testing after 1 h. Perform blood type testing. |

| Admission Criteria Post-Paracentesis | |

| 1. SBP | Confirmed SBP diagnosis. |

| 2. Hemodynamic Instability | Hemodynamic changes or a drop in hemoglobin level >1 g/dL. |

| 3. Severe Pain or Hematoma | VAS ≥ 7 + expanding hematoma → consider urgent abdominal CT angiography. |

2.3. Major Complications [2,3,5,6]

3. Section II: Thoracocentesis in Patients with Pleural Effusion

3.1. Indications [13,19,20,21]

3.2. Clinical Recommendations for Thoracocentesis

| Section | Recommendation |

| Preprocedural Requirements and Recommendations | |

| 1. Imaging | Localize effusion using POCUS. |

| 2. Access Point | Two intercostal spaces below the fluid peak in the posterior mid-clavicular line with the patient seated, arms forward. Above the rib. |

| 3. Needle/Drainage Kit | 20–21G cannula or 6–8F Seldinger catheter. |

| 4. Coagulation Guidelines | No repeat tests if no coagulopathy history and normal test results in the past month. a. DOACs: Stop 48 h prior. b. Warfarin: Stop 5 d prior; confirm INR <1.7. c. Clexane (LMWH): Hold 24 h (2 doses). d. Aspirin: Continue [25]. e. Plavix: Stop 72 h prior [22,25]. f. Platelet count of <50 000/μL: Administer 6 units. g. INR >1.7: Administer ≤3 FFP units. h. TEG: Optional if available. |

| Procedure Guidelines | |

| 1. Bilateral Drainage | Do not perform on the same day. |

| 2. Volume Limit | Do not exceed 1.5 L drainage per session [19]. |

| 3. Drainage Method | Use gravity drainage. Avoid vacuum suction [2]. |

| 4. Anesthesia | Use 1% lidocaine for local anesthesia [19]. |

| 5. Diagnostic Testing | Send pleural fluid for pH, LDH, glucose, protein, cytology, and BNP assessments. |

| Postprocedure Care | |

| 1. Vital Signs | Monitor hourly for 2 h. |

| 2. Imaging | Chest radiography (AP + LAT) 1 h postprocedure [19]. |

| 3. Anticoagulation | Restart the next day. |

| Documentation Checklist | |

| 1. Indication | Document the indication for the procedure. |

| 2. Consent | Obtain and document verbal or written consent. |

| 3. Physical/POCUS Findings | Record the physical exam and POCUS findings. |

| 4. Technique | Document the insertion technique. |

| 5. Vital Signs | Record pre- and postprocedure vital signs. |

| 6. Anticoagulation | Document anticoagulation status and last dose timing. |

| 7. Laboratory test results | Include relevant laboratory test results and hemostasis assessment. |

3.2. Complications

- Reexpansion pulmonary edema: This is a rare but potentially serious complication, with an incidence of <0.1%, and is associated with rapid or large-volume fluid removal, especially if pleural pressures fall below −20 cm H2O or if >1.5 L is removed quickly. Symptom-limited drainage is recommended to mitigate this risk [4].

- Secondary infections: Complications following thoracentesis include empyema (pus in the pleural space), parapneumonic effusion (infected pleural fluid associated with pneumonia), and, less commonly, cellulitis or soft tissue infection at the puncture site. These complications are rare when sterile technique is used. Empyema and complicated parapneumonic effusion are clinically significant and often require antimicrobial therapy and drainage. According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology, the most common pathogens in pleural space infections are Streptococcus anginosus, Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant S. aureus in hospital-acquired cases), anaerobes, and Enterobacterales. Hospital-acquired infections are more likely to involve resistant gram-negative bacteria [13].

- Hemorrhage: Hemorrhage is a recognized but rare complication of pleural effusion paracentesis (thoracentesis) with a risk of significant bleeding (including hemothorax or puncture site bleeding) of approximately ≤1%, as indicated in large meta-analyses and cohort studies. The primary mechanism is misplaced needle or catheter insertion, resulting in laceration of the intercostal artery or its branches, which can lead to chest wall hematoma or hemothorax. Injury to other vascular structures or inadvertent puncture of abdominal organs (e.g., the liver and spleen) is rare but possible, especially for low-lying effusions or with improper techniques. Lack of ultrasound guidance, poor knowledge of the local anatomy, and multiple needle passes increase the risk. Vascular ultrasonography with color Doppler can help avoid vessel injury [22,24].

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHF | congestive heart failure |

| LVP | large-volume paracentesis |

| PICD | post-paracentesis circulatory dysfunction |

| SBP | spontaneous bacterial peritonitis |

| SAAG | serum–ascites albumin gradient |

References

- Moore, K.P.; Aithal, G.P. Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. Gut 2021, 70, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biggin, S.W.; Angeli, P.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Ginès, P.; Ling, S.C.; Nadim, M.K.; Wong, F.; Kim, W.R. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome: 2021 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2021, 74, 1014–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, P.S.; Runyon, B.A. Treatment of patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pose, E.; Piano, S.; Juanola, A.; Ginès, P. Hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 588–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyon, B.A. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: Update 2012. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1651–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, J.; Bufalini, J.; Dreer, J.; Shah, V.; King, L.; Wang, L.; Evans, M. Paracentesis in anticoagulated patients. Intern Med J 2025, 55, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.L.; Lokan, T.; Chinnaratha, M.A.; Veysey, M. Risk of bleeding after abdominal paracentesis in liver disease: A meta-analysis. JGH Open 2024, 8, e70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intagliata, N.M.; Davitkov, P.; Allen, A.M.; Falck-Ytter, Y.T.; Stine, J.G. AGA technical review on coagulation in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1630–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Dong, J.; Weng, Z.; Shao, L.; Chen, J.; Jiang, J. Hemorrhagic complications following abdominal paracentesis. Medicine 2015, 94, e2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dorin, S.; Schwartz, A.; Tudas, R.; Sanchez, K.; Amarneh, M.; Kuperman, E. Bleeding risks with apixaban during paracentesis. Cureus 2025, 17, e80299. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J.T.; Matthay, M.A.; Harris, H.W. Secondary peritonitis: Principles of diagnosis and intervention. BMJ 2018, 361, k1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusumano, G.; La Via, L.; Terminella, A.; Sorbello, M. Re-expansion pulmonary edema as a life-threatening complication in massive, long-standing pneumothorax: A case series and literature review. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbert, R.M.; Atwell, T.D.; Lekah, A.; Patel, M.D.; Carter, R.E.; McDonald, J.S.; Rabatin, J.T. Safety of ultrasound-guided thoracentesis in patients with abnormal preprocedural coagulation parameters. Chest 2013, 144, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paparoupa, M.; Wege, H.; Creutzfeldt, A.; Sebode, M.; Uzunoglu, F.G.; Boenisch, O.; Nierhaus, A.; Izbicki, J.R.; Kluge, S. Perforation of the ascending colon during implantation of an indwelling peritoneal catheter: A case report. BMC Gastroenterol 2020, 20, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.L.; Holroyd-Leduc, J.; Thorpe, K.E.; Straus, S.E. Does this patient have bacterial peritonitis or portal hypertension? How do I perform a paracentesis and analyze the results? JAMA 2008, 299, 1166–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, G.; Castellote, J.; Alvarez, C.; Girbau, A.; Gordillo, J.; Baliellas, C.; Casas, M.; Pons, C.; Román, E.M.; Maisterra, S.; Xiol, X. Secondary bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: A retrospective study of clinical and analytical characteristics, diagnosis and management. J Hepatol 2010, 52, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.M.; Binnicker, M.J.; Campbell, S.; Carroll, K.C.; Chapin, K.C.; Gilligan, P.H.; Gonzalez, M.D.; Jerris, R.C.; Kehl, S.C.; Patel, R.; Pritt, B.S. Guide to utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2024 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin Infect Dis 2024, ciae104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchot, J.W.; Kalva, S.P.; Majdalany, B.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Ahmed, O.; Asrani, S.K.; Cash, B.D.; Eldrup-Jorgensen, J.; Kendi, A.T.; Scheidt, M.J.; Sella, D.M. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® radiologic management of portal hypertension. JACR 2021, 18, S153–S173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asciak, R.; Bedawi, E.O.; Bhatnagar, R.; Clive, A.O.; Hassan, M.; Lloyd, H.; Reddy, R.; Roberts, H.; Rahman, N.M. British Thoracic Society clinical statement on pleural procedures. Thorax 2023, 78, s43–s68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, M.E.; Chong, C.A.; Stanbrook, M.B.; Tricco, A.C.; Wong, C.; Straus, S.E. Does this patient have an exudative pleural effusion? The Rational Clinical Examination systematic review. JAMA 2014, 311, 2422–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yataco, A.C.; Soghier, I.; Hébert, P.C.; Belley-Cote, E.; Disselkamp, M.; Flynn, D.; Halvorson, K.; Iaccarino, J.M.; Lim, W.; Lindenmeyer, C.C.; Miller, P.J. Transfusion of fresh frozen plasma and platelets in critically ill adults: An American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline. Chest 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, K.; Epelbaum, O. Percutaneous pleural drainage in patients taking clopidogrel: Real danger or phantom fear? JAMA 2014, 311, 2422–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaralingam, A.; Bedawi, E.O.; Harriss, E.K.; Munavvar, M.; Rahman, N.M. The frequency, risk factors, and management of complications from pleural procedures. Chest 2022, 161, 1407–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, A.E.S.; Landaeta, M.F.; Adrianza, A.M.; Aldana, G.L.; Pozo, L.; Armas-Villalba, A.; Toquica, C.C.; Larson, A.J.; Vial, M.R.; Grosu, H.B.; Ost, D.E. Complications following symptom-limited thoracentesis using suction. Eur Respir J 2020, 56, 1902356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangers, L.; Giovannelli, J.; Mangiapan, G.; Alves, M.; Bigé, N.; Messika, J.; Morawiec, E.; Neuville, M.; Cracco, C.; Béduneau, G.; Terzi, N. Antiplatelet drugs and risk of bleeding after bedside pleural procedures: A national multicenter cohort study. Chest 2021, 159, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).