1. Introduction

Emergency laparotomy (EL) remains one of the highest-risk procedures in general surgery, with consistently reported mortality rates between 10–20% and morbidity exceeding 40% in many cohorts [

1]. These outcomes stand in sharp contrast to comparable elective procedures, where perioperative pathways and prehabilitation programs have significantly improved recovery, reduced complications, and shortened hospital stays [

2]. Despite its frequency and impact, EL is often characterized by variability in perioperative care delivery, resource allocation, and postoperative trajectories, especially in elderly and frail populations [

3].

International societies have increasingly emphasized that structured perioperative pathways—most notably, the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) approach—should not be confined to elective settings but should also be adapted for urgent procedures as well [

4,

5,

6]. ERAS principles, including early nutrition, goal-directed fluid therapy, multimodal analgesia, pulmonary optimization, and early mobilization, have become the standard of care in elective surgery. Their translation into emergency contexts, however, requires modification to accommodate compressed timelines, diagnostic uncertainty, and the imperative not to delay definitive source control [

7,

8].

Meta-analysis and comparative cohort studies in emergency abdominal surgery suggest that ERAS-aligned pathways are both feasible and associated with beneficial outcomes, such as reduced length of stay, fewer postoperative complications, and improved functional recovery [

7,

8]. However, implementation remains inconsistent, and the “window of opportunity” for pre-optimization is often underused in emergency departments (EDs), where patients may spend hours awaiting diagnostic clarification, resuscitation, or operating room (OR) availability [

5,

9].

A targeted approach is essential. Sarcopenia and frailty are now well-recognized as strong, independent predictors of postoperative complications, prolonged length of stay, institutionalization, and mortality in emergency surgical populations [

10,

11,

12]. Sarcopenia may already be present before surgery or develop acutely in the perioperative course (“acute sarcopenia”), compounding vulnerability [

11]. Frailty assessment tools and rapid scoring systems, such as the Emergency Surgery Score (ESS), provide clinicians with a pragmatic way to stratify risk and allocate resources in busy emergency department (ED) settings [

13].

Moreover, oncological emergencies, such as obstructive colorectal cancer, present a frequent and particularly high-risk subset where the principles of ERAS can and should be adapted, provided that no-delay governance and structured handover into perioperative orders are guaranteed [

14].

Objective. The aim of this scoping review is to synthesize current evidence on emergency department (ED)-initiated perioperative care aligned with enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) for emergency laparotomy (EL), including standards and guidelines, comparative effectiveness, feasible pre-optimization components, targeting strategies using frailty, sarcopenia, and essential surgical skills (ESS), and contextual evidence from oncology emergencies. From this synthesis, we propose a minimal, pragmatic, ED-initiated bundle that is feasible, safe, and transferable to clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rationale and Design

A scoping review methodology was selected because the field of perioperative prehabilitation in the context of emergency laparotomy (EL) is heterogeneous, rapidly evolving, and insufficiently mapped for formal meta-analysis. Scoping reviews enable the identification of concepts, evidence gaps, and implementation opportunities across diverse study designs. The methodology followed Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, which was expanded by Levac et al., and conformed to the PRISMA-ScR checklist to enhance transparency and reproducibility.

2.2. Research Questions

The review was guided by the following questions:

What ERAS standards and guidelines currently exist for emergency laparotomy?

What evidence supports the feasibility and effectiveness of ERAS-aligned interventions in emergency surgery?

Which components of pre-optimization are feasible to initiate in the emergency department (ED) without delaying surgery?

Which tools (e.g., ESS, sarcopenia, frailty indices) are available for rapid risk stratification in ED settings?

What evidence exists regarding the contextual application in oncological emergencies, particularly in obstructive or complicated colorectal cancer?

2.3. Eligibility Criteria (PCC Framework)

Population: Adults (≥18 years) undergoing emergency gastrointestinal or hepatopancreatobiliary surgery, with an emphasis on EL.

Concept: Interventions or care bundles aligned with ERAS and perioperative optimization, including nutrition, respiratory training, mobilization, delirium prevention, anemia/micronutrient correction, fluid and analgesia strategies, and implementation science. Also included were risk stratification tools (ESS, frailty, sarcopenia).

Context: EDs, acute surgical admission units, and perioperative emergency pathways (including oncological emergencies).

2.4. Sources of Evidence and Search Strategy

We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library (inception to February 2025) using terms related to “emergency laparotomy,” “ERAS,” “prehabilitation,” “pre-optimization,” “frailty,” “sarcopenia,” “emergency surgery score,” and “anemia.” The search was supplemented by manual scanning of guideline repositories (ERAS Society, World Society of Emergency Surgery), backward/forward citation chasing, and targeted grey literature.

2.5. Study Selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts and assessed full texts. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. A PRISMA-ScR flow diagram will be provided in

Supplementary Figure S1.

2.6. Data Extraction and Charting

Data were extracted into a structured template capturing study design, setting, population, intervention domains (nutrition, respiratory, mobilization, delirium prevention, anemia/micronutrients, analgesia/fluids, implementation), and outcomes (mortality, morbidity, LOS, discharge destination, functional recovery, transfusion, feasibility). Risk stratification tools were extracted separately.

2.7. Synthesis of Results

Given the heterogeneity, a narrative synthesis was undertaken. Evidence was grouped into five domains: (i) ERAS standards; (ii) comparative outcomes; (iii) ED-initiated pre-optimization; (iv) targeting and risk stratification; and (v) oncological emergencies. Gaps and implementation implications were identified.

3. Results

3.1. Evidence Base

The synthesis incorporated: ERAS Society guidelines for EL (Part 1: preoperative [

5]; Part 2: intra and postoperative [

6]); a systematic review of emergency laparotomy pathways [

4]; meta-analysis of ERAS protocols in emergency abdominal surgery [

7]; cohort evidence [

8]; a review of best practices for pre-optimization [

9]; international consensus on perioperative anemia and iron deficiency [

15]; systematic reviews on sarcopenia [

10,

11], frailty [

12,

16], and ESS [

13]; and contextual evidence from colorectal oncology [

14].

Population studies further describe the incidence, outcomes, and trends in elderly or frail patients undergoing emergency surgery [

17,

18,

19], while contemporary cohorts outline utilization patterns and mortality signals [

15,

18].

3.2. ERAS Standards for EL

The ERAS Society guidelines codify a structured, time-sensitive pathway that includes rapid diagnosis, senior-led assessment, risk stratification, targeted optimization, intraoperative multimodal strategies, and postoperative early feeding and mobilization [

5,

6]. These guidelines stress the principle of “no delay”: preoperative interventions should never compromise the time to source control.

3.3. Evidence of Effect

A meta-analysis of ERAS in emergency abdominal surgery demonstrated reduced LOS and complications [

7], and cohort studies have confirmed feasibility with signals for improved outcomes [

8]. A systematic review further identified common interventions (nutrition, early mobilization, multimodal analgesia, fluid balance) and outcome domains (LOS, complications, mortality, functional recovery) as priorities for adoption and audit [

4].

3.4. Pre-Optimization is Feasible in ED

Best-practice guidance supports pragmatic preoperative interventions that can be safely initiated without delay: multimodal analgesia and goal-directed fluids, early oral supplements if the risk of aspiration is low, respiratory preparation (incentive spirometer or brief inspiratory muscle training), and treatment of reversible comorbidities such as anemia [

9]. The 2017 international consensus on perioperative anemia supports early screening and IV iron in urgent pathways where logistics permit [

15]. These actions represent an opportunity to “buy back” physiological reserve during ED waits for diagnostics, OR slots, or senior review (

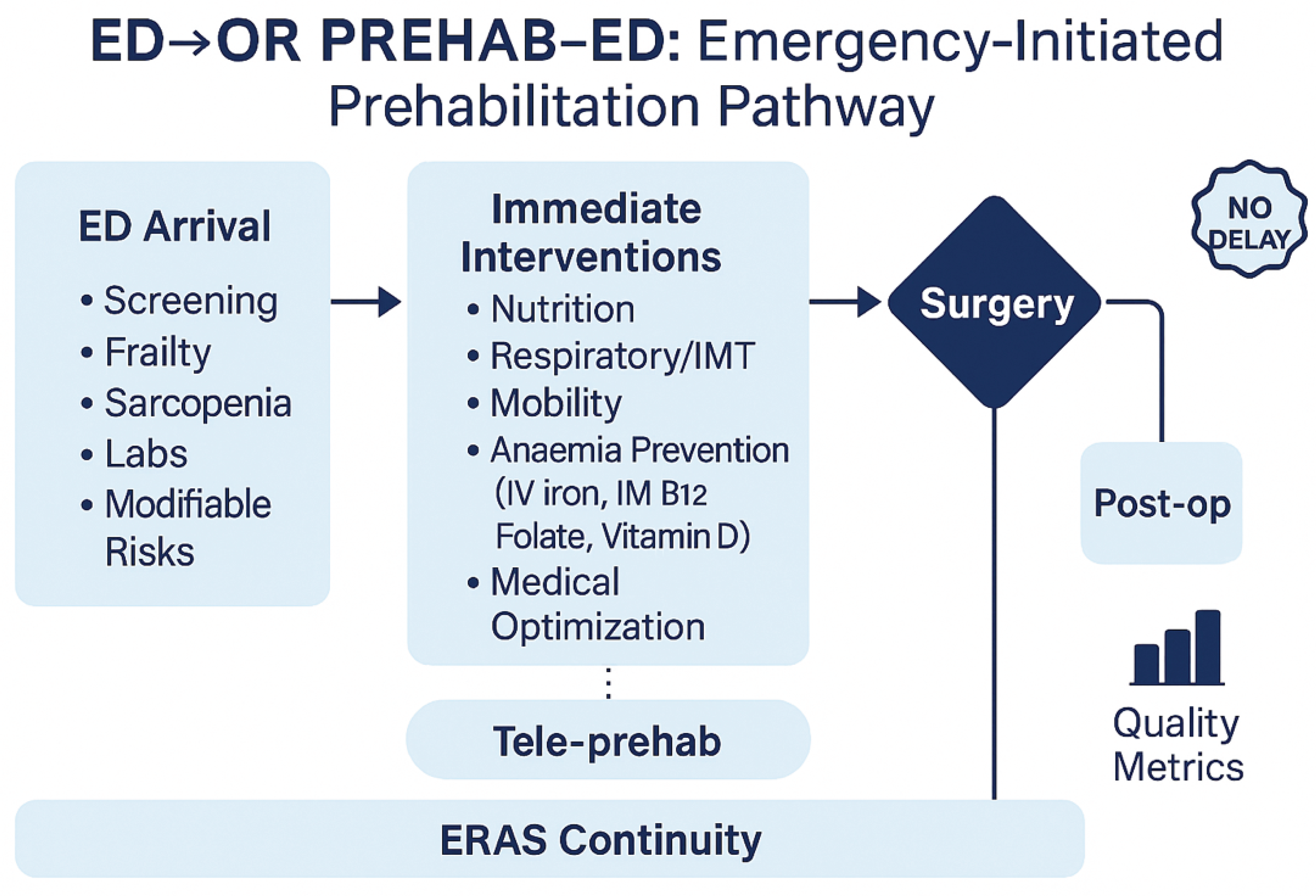

Figure 1).

3.5. Targeting High-Risk Patients

Sarcopenia is a strong predictor of adverse outcomes after EL [

10], and acute sarcopenia has been described peri-operatively [

11]. Frailty similarly increases mortality and complications [

12,

16]. The ESS offers a rapid, validated risk stratification tool for triage and bundle activation in the ED [

13]. ED-based ultrasound of the rectus femoris muscle has been piloted as a feasible biomarker of sarcopenia, providing an immediate bedside measure [

20].

3.6. Oncology Emergencies and Local Programs

In obstructive colorectal cancer, ERAS-consistent measures are broadly applicable but must be tailored to aspiration risk, obstruction physiology, and sepsis. Narrative evidence supports the feasibility of ERAS in this setting [

14]. Contemporary prehabilitation programs demonstrate the feasibility of morphofunctional assessment and combined interventions (oral supplements + exercise) [

21], report cost savings from integrated prehabilitation [

22], and show improved postoperative outcomes after structured optimization [

23].

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of an emergency-initiated prehabilitation pathway. At ED arrival, patients undergo rapid screening (frailty, sarcopenia, labs, modifiable risks). Immediate interventions include nutrition, respiratory training, mobility, anaemia prevention (IV iron, IM B12, folate, vitamin D), and general medical optimisation. All actions operate under the principle of no delay and must be transferred to the operating room and postoperative care. ERAS continuity and tele-prehab strategies support adherence, with outcomes assessed via quality metrics.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of an emergency-initiated prehabilitation pathway. At ED arrival, patients undergo rapid screening (frailty, sarcopenia, labs, modifiable risks). Immediate interventions include nutrition, respiratory training, mobility, anaemia prevention (IV iron, IM B12, folate, vitamin D), and general medical optimisation. All actions operate under the principle of no delay and must be transferred to the operating room and postoperative care. ERAS continuity and tele-prehab strategies support adherence, with outcomes assessed via quality metrics.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings and Interpretation

This scoping review synthesizes guideline recommendations, comparative evidence, and best-practice reviews to propose a practical, emergency department-initiated, enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS)-aligned strategy for emergency laparotomy (EL). Across sources, three themes consistently emerge. First, ERAS standards for EL provide a coherent framework spanning rapid assessment and optimization, intraoperative management, and postoperative rehabilitation, with the explicit principle of “no delay” to source control [

5,

6]. Second, comparative data—though heterogeneous—generally favor ERAS-aligned pathways in emergency abdominal surgery, showing signals for reduced complications and a shorter length of stay (LOS) versus conventional care [

7,

8]. Third, risk targeting is essential: sarcopenia and frailty are prevalent and strongly predictive of adverse outcomes in EL populations, while pragmatic tools such as the Emergency Surgery Score (ESS) support rapid triage and resource allocation in pressured ED settings [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Together, these strands justify a minimal, time-efficient pre-optimization bundle that is initiated in the ED, explicitly does not delay the OR, and is seamlessly handed over to intra and postoperative care.

4.2. Why an ED-Initiated Bundle Matters

Systems-level work highlights high utilization and mortality after emergency general surgery (EGS), with wide variation by center—particularly in older adults [

1,

2]. Contemporary epidemiology points to a substantial, persistent burden of EGS admissions and operations arising directly from the ED [

16,

17,

18], including very elderly patients who experience steep functional decline after surgery [

18]. In this context, hours spent in the Emergency Department (ED) or on the acute surgical unit awaiting diagnostics, senior review, or the Operating Room (OR) represent a window to initiate small, safe, physiologically meaningful actions. The ERAS Part 1 guidance explicitly endorses rapid, structured preoperative optimization without postponing surgery[

5], while Part 2 emphasizes the continuity and accountability required to carry ED measures forward into the operating room and ward [

6]. This “ED-to-OR handover” concept is the keystone that converts opportunistic pre-optimization into an integrated pathway.

4.3. Mechanistic Rationale for the Bundle

Four domains are consistently supported across the mapped literature:

Analgesia and fluids. Goal-directed fluid therapy and multimodal, opioid-sparing analgesia are core ERAS elements that attenuate physiological stress and reduce pulmonary and ileus-related complications [

5,

6,

7,

8]. In emergencies, the aim is not elaborate prehabilitation but fast, protocolized resuscitation and pain control that stabilize physiology without delaying source control [

5,

9].

Nutrition. Early, safe nutrition is linked to preserved lean mass and immune function in elective ERAS. In emergencies, oral nutritional supplements (ONS) can be initiated when the aspiration risk is acceptable and the obstruction physiology allows, with continuation postoperatively [

5,

9]. Recent program experience supports the feasibility of combined nutrition-exercise interventions and their potential to improve perioperative readiness [

21] and generate cost savings [

22].

Respiratory preparation. Incentive spirometer and brief inspiratory muscle training (IMT), when feasible, are low-risk and may reduce atelectasis-related complications, particularly in high-risk or painful upper-abdominal presentations [

9]. Given the compressed timelines, even short exposure alongside coaching can be justified if it does not interfere with OR timing.

Pragmatic comorbidity optimization (patient blood management, PBM). Anemia and iron deficiency are common and are associated with transfusions and adverse outcomes. The international consensus advocates early screening and intravenous iron (IVI) when timelines and logistics permit [

19]. In emergency pathways, a single-dose IVI strategy during ED/ward wait can be considered for iron-deficiency anemia when it will not delay OR. Where feasible and indicated, targeted correction of vitamin B12, folate, and vitamin D can be incorporated, recognizing that the evidence is extrapolated and the timing is short [

19]. The unifying principle is opportunism without delay.

4.4. Targeting: Who Stands to Benefit Most

Sarcopenia is consistently associated with complications, prolonged LOS, and mortality after EL [

10]. “Acute sarcopenia”—rapid, perioperative loss of muscle mass and function—further jeopardizes recovery trajectories [

11]. A Frailty meta-analysis in emergency surgery reinforces higher mortality and complications along the frailty spectrum [

12,

13,

14]. Operationalizing this in the ED requires tools that are fast and actionable. ESS provides a global risk estimate calibrated for EGS and is practical for triage and escalation decisions (e.g., senior review, HDU/ICU liaison, early physiotherapy and dietetics) [

14]. As a complementary approach, point-of-care ultrasound of the rectus femoris offers a feasible morphofunctional marker of sarcopenia in the ED and may help prioritize rehabilitation resources, though further validation for outcome prediction and change sensitivity is needed [

20]. In very elderly cohorts—including nonagenarians—functional decline after EGS is striking [

18], making proactive, risk-targeted supportive care ethically and clinically compelling.

4.5. Context: Oncological Emergencies

Obstructive or complicated colorectal cancer (CRC) constitutes a frequent, high-risk EL indication. Narrative evidence indicates that ERAS principles remain applicable if aspiration risk, obstruction physiology, and septic control are respected [

15]. These patients may be especially suitable for a short-course, multimodal ED bundle (e.g., ONS if safe, respiratory coaching, mobilization intent, anemia screening) coupled with explicit transfer of orders and early ICU planning where indicated. Contemporary ERAS-colorectal experience suggests that pathway adherence can reduce LOS and readmissions [

24]; local programmatic reports describe feasibility, economic benefits, and improved postoperative outcomes after structured optimization/prehabilitation [

22,

23].

4.6. Implementation: From Concept to Routine Practice

Heterogeneity in outcomes across centers [

2] and across income settings [

3] underscores the need for implementation science. Three enablers recur:

Triggers in the EHR. Embedding ESS and a brief sarcopenia/frailty screen as ED prompts can automatically trigger order sets (ONS when safe, incentive spirometer, mobilization intent, CBC/ferritin/TSAT) and a “no-delay” rule [

5,

6,

14].

Ready-to-use kits and roles. Respiratory devices at triage bays, ONS stock, patient leaflets, and a one-page protocol reduce friction. Role clarity (ED nursing, physiotherapy, dietetics, anesthesia, surgery) mitigates “everyone/no-one” ownership problems and aligns with ERAS Part 2 accountability [

6,

9].

Handover and escalation. A templated “ED→OR→ward” handover (checklist plus named owner) preserves fidelity. For high-risk flags (ESS high, severe frailty/sarcopenia), pre-defined escalation (senior surgical review, anesthesia/ICU consult) shortens the time to definitive decisions [

6,

14].

4.7. Measurement and Learning

Adoption benefits from concise metrics that are easy to capture and meaningful for both teams and managers. Process indicators include: completion rates of ESS and sarcopenia/frailty screens; time to antibiotics and to the operating room; initiation of ONS/respiratory coaching when eligible; and documentation of handover orders. Early clinical outcomes include pulmonary complications, delirium proxies, LOS, discharge destination, transfusion exposure, and 30-day readmission; functional outcome tracking is desirable where feasible [

4,

6,

7,

8,

21,

23]. Regular audit-feedback cycles can progressively reduce variation and strengthen adherence, addressing the center-to-center variability documented in EGS [

2]. Program reports demonstrating cost savings from prehabilitation can be leveraged to sustain institutional support [

22].

4.8. Equity and Context Sensitivity

Outcomes after EGS are particularly vulnerable to resource constraints, with LMIC settings facing structural barriers to guideline implementation[

3]. The proposed ED-initiated bundle is intentionally minimal, low-cost, and designed to fit varied contexts: it prioritizes screening and supportive actions that are quick, safe, and likely to yield benefits even when specialist staffing is limited. Point-of-care approaches (e.g., rectus femoris ultrasound) may democratize risk assessment where CT-based body composition is unavailable [

20]. Nevertheless, successful implementation in constrained settings requires local adaptation, phased roll-out, and explicit attention to supply chains (e.g., ONS, IV iron availability).

4.9. Safety Considerations and “No-Delay” Governance

The single most important guardrail is that pre-optimization must never delay source control. All elements in the bundle are optional and opportunistic; they should be aborted or deferred at the first hint of interference with time-to-OR targets. Nutrition is initiated only when the aspiration risk is low; respiratory training must not impede necessary analgesia, imaging, or transport; PBM actions (e.g., IV iron) are pursued only when they are logistically neutral to OR timing[

5,

6,

9,

19] . Embedding the “no-delay” rule into the EHR order set reduces the risk of mission creep.

4.10. How This Review Advances the Field

Compared with existing guidance and reviews, our synthesis (i) integrates ED-specific feasibility with ERAS standards, (ii) explicitly prioritizes risk-targeted deployment using ESS and sarcopenia/frailty, and (iii) translates the evidence into a minimal, handover-anchored bundle suitable for immediate adoption. By situating pre-optimization in the ED and defining practical enablers and metrics, the review bridges the gap between elective prehabilitation paradigms and the realities of urgent care.

4.11. Limitations of the Evidence Base and of This Review

Evidence supporting ERAS in emergencies is heterogeneous and often observational, with variability in pathway composition and fidelity [

7,

8]. Randomized evidence for individual pre-optimization components in true emergency timelines is scarce; PBM recommendations are consensus-based and largely extrapolated from elective pathways [

19]. The prognostic role of sarcopenia/frailty is clear, but the demonstration of reversibility within the limited ED-to-OR window remains limited [

10,

11,

12,

13]. As a scoping review, our synthesis privileges breadth and transferability over pooled effect sizes and does not perform risk-of-bias grading. These limitations reinforce the need for pragmatic implementation research.

4.12. Practice Recommendations

We recommend:

Activate a minimal, ED-initiated, ERAS-aligned bundle comprising multimodal analgesia, goal-directed fluids, early safe nutrition, respiratory preparation, mobilization intent, and pragmatic PBM (CBC, ferritin/TSAT; consider IV iron when indicated/logistically neutral; correct B12/folate/vitamin D as appropriate) under an explicit no-delay rule [

5,

6,

9,

15].

Target deployment using ESS and a brief sarcopenia/frailty screen; consider rectus femoris ultrasound to refine prioritization where feasible [

10,

11,

12,

13,

20].

Embed EHR triggers, ready-to-use kits, and named ownership for ED→OR→ward handover; pre-define escalation for high-risk flags [

6,

13].

Monitor a concise metric set and feed results back to teams; leverage economic and outcome gains from local programs to maintain support [

4,

7,

8,

22,

23,

24].

4.13. Research Agenda

Priorities include: cluster-pragmatic evaluations of the ED bundle versus usual care; fidelity, cost, and equity reporting; core outcome sets aligned with emergency ERAS audits; operational validation of ED rectus femoris ultrasound as a risk and response biomarker; implementation of urgent PBM algorithms with time-to-OR neutrality; and dedicated evaluations in oncological emergencies, especially obstructive CRC [

4,

6,

14,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Studies should deliberately include very elderly and frail cohorts given their disproportionate risk [

12,

16,

17,

18,

19].

5. Conclusions

A targeted, ED-initiated, no-delay bundle that is explicitly integrated with ERAS intra- and postoperative care is biologically plausible, guideline-concordant, implementable, and supported by favourable signals in the emergency literature. By aligning risk stratification with pragmatic pre-optimisation and reliable handover, centres can reasonably expect to reduce complications and LOS while addressing unwarranted variation in EL outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the staff of the Emergency Department of the Infanta Cristina University Hospital for their collaboration and patience during the data collection process. Special thanks to the nursing team and nursing assistants for their continued support and involvement throughout the ultrasound assessments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASA-PS |

American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification |

| CFS |

Clinical Frailty Scale |

| ED |

Emergency Department |

| EL |

Emergency Laparotomy |

| ERAS |

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery |

| ESS |

Emergency Surgery Score |

| HPB |

Hepatopancreatobiliary |

| LOS |

Length of Stay |

| mNUTRIC |

Modified Nutrition Risk in Critically Ill score |

| ONS |

Oral Nutritional Supplements |

| OR |

Operating Room |

| p-POSSUM |

Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enumeration of Mortality and Morbidity |

| PREHAB-ED |

Prehabilitation bundle initiated in the Emergency Department |

| RCT |

Randomised Controlled Trial |

| SARC-F |

Strength, Assistance with walking, Rise from a chair, Climb stairs, and Falls questionnaire |

| SARC-CalF |

SARC-F questionnaire plus calf circumference measurement |

| US |

Ultrasound |

References

- Lee, K.C.; Sturgeon, D.; Lipsitz, S.; Weissman, J.S.; Mitchell, S.; Cooper, Z. Mortality and health care utilization among Medicare patients undergoing emergency general surgery vs those with acute medical conditions. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingraham, A.M.; Cohen, M.E.; Raval, M.V.; Ko, C.Y.; Nathens, A.B. Variation in quality of care after emergency general surgery procedures in the elderly. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2011, 212, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.A.; Haider, A.H.; Riviello, R.; Zogg, C.K.; Zafar, S.N.; Latif, A.; et al. Geriatric emergency general surgery: survival and outcomes in a low-middle income country. Surgery 2015, 158, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harji, D.P.; Griffiths, B.; Stocken, D.; Pearse, R.; Blazeby, J.; Brown, J.M. Key interventions and outcomes in perioperative care pathways in emergency laparotomy: a systematic review. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2025, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peden, C.J.; Aggarwal, G.; Aitken, R.J.; Anderson, I.D.; et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Emergency Laparotomy Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations: Part 1—Preoperative. World J. Surg. 2021, 45, 1272–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.J.; Aggarwal, G.; Aitken, R.J.; Anderson, I.D.; et al. Consensus Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Emergency Laparotomy Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations Part 2—Intra- and Postoperative Care. World J. Surgery 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibandeh, S.; Hajibandeh, S.; Bill, V.; Satyadas, T. Meta-analysis of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Protocols in Emergency Abdominal Surgery. World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 1296–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisely, J.C.; Barclay, K.L. Effects of an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery programme on emergency surgical patients. ANZ J. Surg. 2016, 86, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulton, T.; Murray, D. Pre-optimisation of patients undergoing emergency laparotomy: a review of best practice. Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphry, N.; Jones, M.; Goodison, S.; Carter, B.; Hewitt, J. The Effect of Sarcopenia on Postoperative Outcomes Following Emergency Laparotomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Frailty Aging 2023, 12, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Dani, M.; Kemp, P.; Fertleman, M. Acute Sarcopenia after Elective and Emergency Surgery. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiner, T.; Nemeth, D.; Hegyi, P.; Ocskay, K.; Virag, M.; Kiss, S.; et al. Frailty and emergency surgery: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 811524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, P.; Nair, A. Emergency Surgery Score as an Effective Risk Stratification Tool for Patients Undergoing Emergency Surgeries: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e26226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailescu, A.A.; Gradinaru, S.; Kraft, A.; Blendea, C.D.; Capitanu, B.S.; Neagu, S.I. Enhanced rehabilitation after surgery: principles in the treatment of emergency complicated colorectal cancers—A narrative review. J. Med. Life 2025, 18, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz, M.; Acheson, A.G.; Auerbach, M.; Besser, M.; Habler, O.; Kehlet, H.; et al. International consensus statement on the peri-operative management of anaemia and iron deficiency. Anaesthesia 2017, 72, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halle-Smith, J.M.; Naumann, D.N.; Powell, S.L.; Naumann, L.K.; Griffiths, E.A. Improving outcomes for elderly patients following emergency surgery: a cutting-edge review. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 2021, 11, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehlmann, C.A.; Taljaard, M.; McIsaac, D.I.; Suppan, L.; Anderegg, E.; Dupuis, A.; et al. Incidence and outcomes of emergency department patients requiring emergency general surgery: a 5-year retrospective cohort study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2024, 154, 3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Lee, K.G.; Kim, M.K. Trends and outcomes of emergency general surgery in elderly and highly elderly population in a single regional emergency center. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2023, 104, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, K.; Yamanaka, K.; Kurimoto, M.; Aoki, H.; Shinkura, A.; Hanabata, Y.; et al. Effect of emergency general surgery on postoperative performance status in patients aged over 90 years. Surg. Open Sci. 2024, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Sanchez, F.J.; Souviron-Dixon, V.E.; Roque-Rojas, F.; Mudarra-Garcia, N. Assessment of Sarcopenia Using Rectus Femoris Ultrasound in Emergency Patients—A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudarra-Garcia, N.; Roque-Rojas, F.; Nieto-Ramos, A.; Izquierdo-Izquierdo, V.; Garcia-Sanchez, F.J. Feasibility of a Pre-Operative Morphofunctional Assessment and the Effect of an Intervention Program with Oral Nutritional Supplements and Physical Exercise. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudarra-Garcia, N.; Roque-Rojas, F.; Izquierdo-Izquierdo, V.; Garcia-Sanchez, F.J. Prehabilitation in Major Surgery: An Evaluation of Cost Savings in a Tertiary Hospital. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Sanchez, F.J.; Mudarra-Garcia, N. Evaluation of Postoperative Results after a Presurgical Optimisation Programme. Perioper. Med. 2024, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.M.; Johnston, L.; Sarosiek, B.; Harrigan, A.; Friel, C.M.; Thiele, R.H.; Hedrick, T.L. Reducing Readmissions While Shortening Length of Stay: The Positive Impact of an Enhanced Recovery Protocol in Colorectal Surgery. Dis. Colon Rectum 2017, 60, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).