Introduction

Postoperative fluid collections (POFCs) are one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality after abdominal surgery [

1]. Even if they are usually asymptomatic, many cases have been reported to cause severe pain, gastric outlet obstruction, fistulas, intraabdominal infection, and sepsis, with mortality of undrained POFCs arising between 45 and 100% [

2,

3]. The incidence of POFCs varies depending on the type of surgery, with pancreatic surgery being one of the most common procedures associated with POFCs. In particular, postoperative pancreatic fluid collections (PPFCs) are a significant and relatively common adverse event following pancreatic surgery, with incidence rates varying depending on the specific procedure [

1,

4]. For instance, up to 25% of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy may develop these collections and this rate can increase to 43% following distal pancreatectomy and from 20 to 60% after central pancreatectomy and enucleation [

4].

PPFCs are caused by the leakage of pancreatic juice from the anastomosis [

5,

6] and they are classified by the International Study Group on Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) based on their severity and the required interventions. The ISGPF categorizes Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula (POPF) and PPFC that resolve spontaneously as Grade A or biliary leakage, PPFCs that require peristent drainage as grade B and PPFCs that require reoperation and that cause organ failure or death as Grade C [

7,

8].

Mutignani et al. have also identified three distinct types of pancreatic injury leading to pancreatic leak/fistula, according to the anatomic position of the leak and the injured duct (main pancreatic duct or small branch duct). This is an endoscopy-oriented classification and leak types are classified into three categories: type I (leakage from the small side branches or the very distal end of the pancreatic duct), type II (leakage from the main pancreatic duct, with disconnected/disrupted pancreatic duct syndrome), and type III (leakage after pancreatectomy) that is divided in type IIIP (after distal pancreasectomy) and type IIID (after duodenocephalopancreasectomy)[

9].

Most POFCs are asymptomatic and they are usually conservatively managed with fasting, total parenteral nutrition, antibiotic and/or somatostatin analogue. If symptoms related to the collection or complications occur, there is the indication for drainage and this happens in just 10% of cases [

10,

11].

Historically, PPFCs were managed with surgical re-exploration and drainage [

12,

13].

In recent years, endoscopic treatment options, particularly the use of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), have gained more and more popularity for the management of PPFCs [

14,

15,

16].

Here, we present a large retrospective multicenter case series of patients with POFCs managed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage (EUS-D) with the aim to report its efficacy and safety, accompanied by a comprehensive literature review on the subject.

2. Materials and Methods

In 2019, the Interventional Endoscopy and Ultrasound (i-EUS) group was created in Italy with the goal of supporting and promoting educational initiatives to optimize the clinical use of lumen apposing metal stents (LAMS). The group consists of centers from across Italy, each with varying levels of expertise in interventional endoscopy. A level of expertise was determined based on the annual volume of EUS and ERCP procedures, the total number of LAMS placements and type of indication for LAMS placement. Centers with less expertise were defined as those that performed fewer than 250 EUS/year, less than 200 ERCP/year at the time of the study and had placed an overall number of LAMS < 20. All centers in the i-EUS group that showed interest in participating were included in a multicenter, retrospective data collection involving all procedures of EUS-D with LAMS for three major indications (PFCs, gallbladder and biliary). [

17] The present retrospective multicenter case-series analysis included 13 Italian secondary and tertiary endoscopy units that performed EUS-guided procedures, including EUS-D of POFCsThe study aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of EUS-D as a treatment for POFCs. The period of study spanned eight years, from January 2013 to December 2020 and data were collected regarding demographics, imaging performed prior to stent placement, the type and size of POFC, the indications for collection drainage, the stent type and any adverse events during or after the procedure.Inclusion criteria were: patients > 18 years, ability to sign an informed consent form for the procedure, patients with a confirmed diagnosis of POFC based on imaging studies (CT or MRI), presence of symptoms related to fluid collection, such as abdominal pain, early satiety, or signs of infection (e.g., fever, elevated white blood cell count), collection that were anatomically accessible via EUS and deemed appropriate for drainage by the treating physician. Exclusion criteria were: patients < 18 years or not able to provide an adequate informed consent, fluid collections deemed asymptomatic, which could be managed conservatively.

Patient selection

The present retrospective case series study included patients diagnosed with POFCs following abdominal surgery. Patients were selected based on biochemical and imaging evidence of POFCs along with the presence of clinical indications for drainage, such as symptoms of infection, abdominal pain, or signs of gastric outlet or biliary obstruction.Imaging techniques were useful in both the diagnosis and subsequent management of POFCs. Prior to the procedure, most patients underwent a contrast-enhanced CT scan to assess the size, location, and complexity of the fluid collection. In cases where CT was contraindicated or provided insufficient detail, an MRI was performed. MRI was particularly useful in evaluating the presence of internal necrosis and in characterizing the fluid content of the collections, which could influence the choice of drainage technique and stent. Patients were monitored using a combination of clinical assessments (in terms of pain, fever, and signs of infection), laboratory tests (including white blood cell count, serum amylase/lipase levels, C reactive protein/procalcitonin) and imaging during follow-up.

Technique

The EUS-guided drainage procedures were performed using a linear array echoendoscopes and carbon dioxide insufflation; patients were under deep sedation or general anesthesia at the discretion of the anesthesiologist. The choice of stent was at the discrection of the endoscopist, based on collection characteristics and operator’s experience and availability. Two main techiniques were used for accessing the collections:

− Single-Stage Procedure: an electrocautery-enhanced lumen-apposing metal stent (LAMS) was inserted directly into the PPFC under EUS guidance. The use of electrocautery allowed for simultaneous tissue penetration and stent deployment, simplifying the procedure and reducing the risk of complications. This technique was particularly favored for its ability to streamline the process and minimize the number of steps required for successful stent placement.

− Needle Plus Guidewire Technique: a stepwise approach in which initially, a 19-gauge needle was used to puncture the collection under EUS guidance. After successful puncture, a 0.035-inch guidewire was introduced through the needle and looped within the collection to provide stability. The puncture site was then enlarged using a cystotome, and over a guidewire, a covered metal stent or double pigtail plastic stents (DPPSs) were deployed.

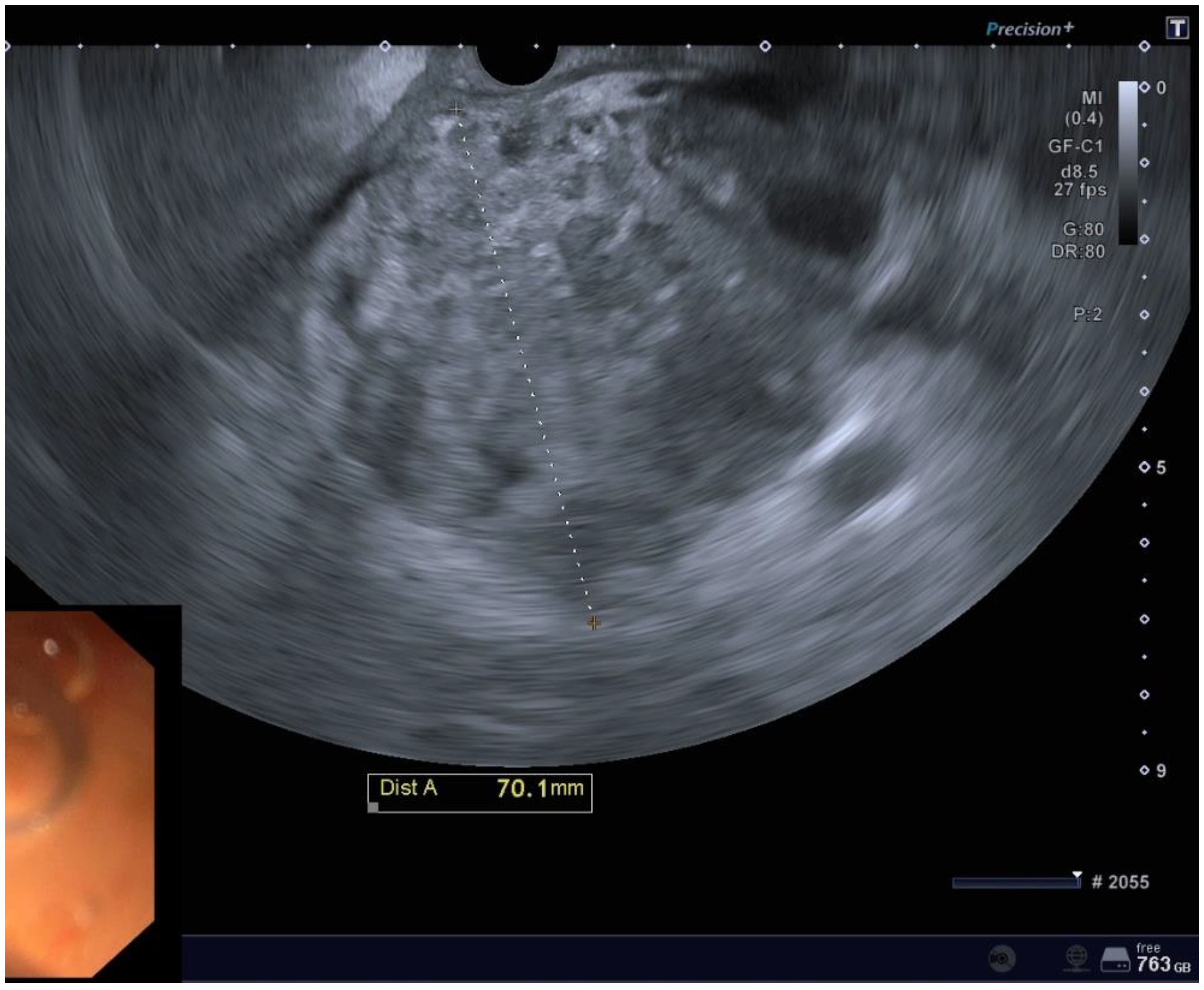

Figure 1.

EUS imaging of a POFC.

Figure 1.

EUS imaging of a POFC.

Endpoints

Primary Endpoint of this study was to provide the rate of technical and clinical success of EUS-D of POFCs. Technical success is defined as the successful placement of stent inside the collection; clinical success is defined as WON or pseudocyst decrease in size <2cm on axial imaging (range 2 weeks-6 months) after stent insertion without need for further endoscopic or surgical procedures.

Secondary endpoints were: type and rate of adverse events (AEs) with severity graded by the ASGE lexicon [

18], and rate of POFC recurrence, defined as the reappearance of a collection or symptoms after initial successful treatment. Recurrence rates were assessed to determine the long-term efficacy of EUS-guided drainage.

Statystical analysis

The data were entered into an Excel database as soon as they were submitted by the participating centers, ensuring patient anonymity. This process allowed for real-time data collection while maintaining anonymity to comply with privacy and data protection regulations. Descriptive statistics for nonparametric distribution were used. Means, medians and standard deviations were used to report the results, as appropriate

3. Results

This series included a total of 47 patients (38% women and 62% men) from 13 Italian centers and most POFCs were caused by pancreatic surgeries. Patients and their clinical characteristics are outlined in

Table 1.

In 40 patients (87%) a CT scan was performed prior the drainage, in 4 patients (9%) an MRI and in 3 cases (3%) both.

Among all the included patients, 19 (40%) were identified as having walled-off necrosis (WON), while the remaining were characterized by pseudocysts, which are typically more homogeneous and without a significant amount of necrotic debris. POFCs were mainly located near the pancreatic body (N 33, 70%), the rest at the level of the tail (N 11, 23%) or the head (N 3, 6%). Most of the collections were uniloculated (N 38, 81%).

The mean size of the POFCs on EUS evaluation was 88.8 mm in width (SD 61.8) and 77.2mm in length (SD 45.7).

Procedural and technical characteristics are outlined in

Table 2.

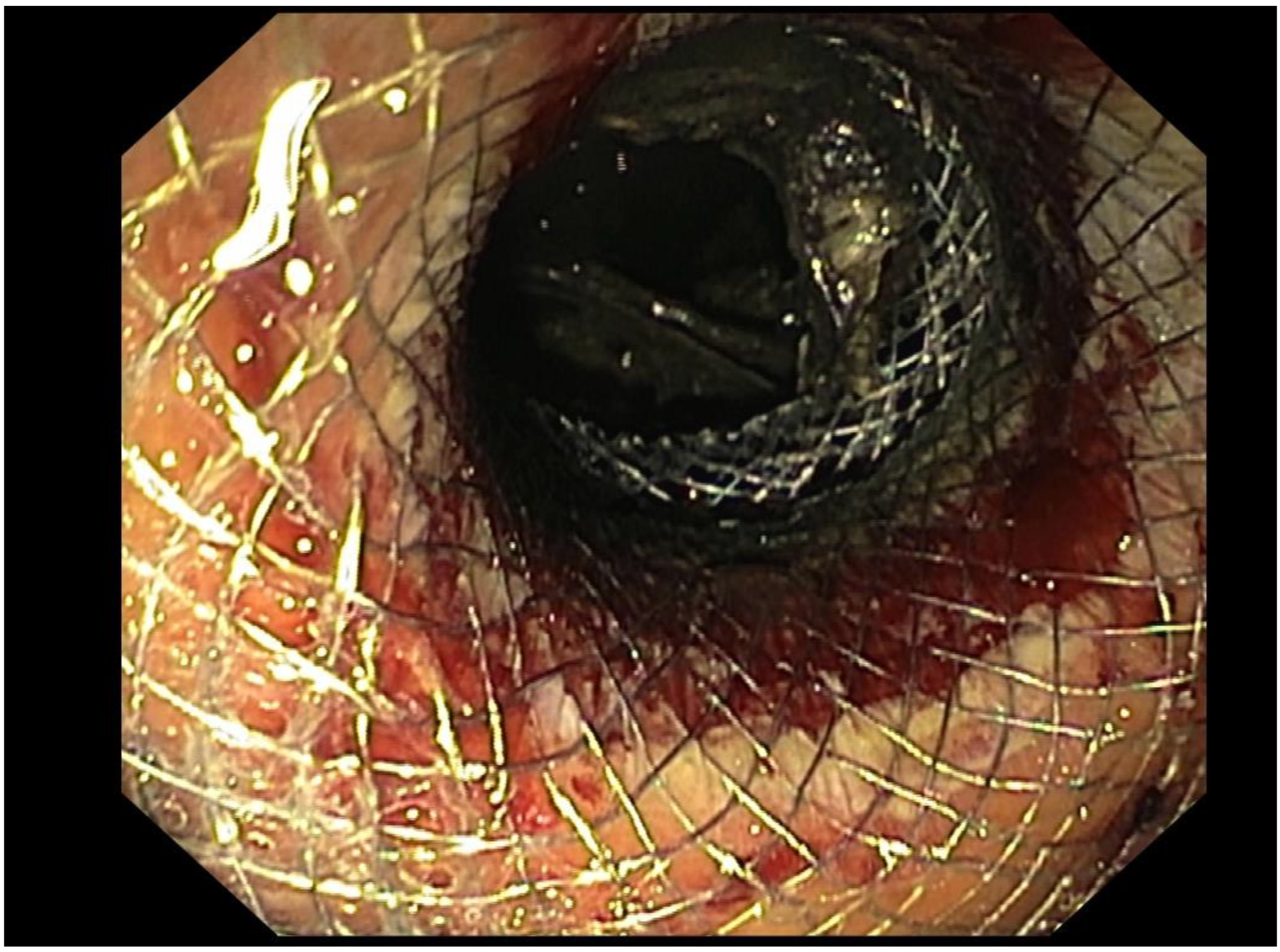

Figure 2.

Use of a LAMS for EUS-D of POFC.

Figure 2.

Use of a LAMS for EUS-D of POFC.

The most common type of access to the collection was the single-stage procedure (29/47, 62%), and the type of stents used was the Hot Axios stent in all cases (N 29/29, 100%).

18 POFCs (18%) were drained using the needle plus guidewire technique and the stents utilized were: Axios stent (N 1/18, 6%), Spaxus stent (N 1/18, 6%), double pigtail plastic stent (DPPS) (N 1/18, 6%), Nagi stent (N 10/18, 55%) and Hanarostent (N 5/18, 28 %).

The majority of the procedures (N 44,94%) were performed using a transgastric approach, while in a smaller number of cases (N 3, 6%), a transduodenal one, which is typically reserved for collections located near the head of the pancreas or when the transgastric approach is not feasible.

Among six patients who underwent positioning of electrocautery LAMS, 4 patients received also one 10Fr pigtail stent, one patient a 8Fr pigtail stent and one patient a 7 Fr pigtail stent in 1.

Technical success was achieved in 46/47 patients (98%); The only patient in which technical success was not achieved, because of technical complexity, was subsequently surgically treated. The mean of hospital stay following stent placement was 17 days (SD 22).

Clinical success was achieved in 45/47 patients (96%). No patients needed for concomitant percutaneous drainage.

In some cases, additional interventions were required, such as direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN), that was performed in a total of 7 patients who did not achieve full resolution of the collection with stent placement alone, with a mean of three sessions DEN (SD 2.6 sessions); in particular one patient needed 6 sessions, three patients needed 2 sessions each and the remaining three patients needed 1 session each.

In 34 patients (72%) the stent was removed, with a mean time between the stent positioning and removal of 48.9 days (SD 64).

The rate of AEs was 11% (5/47). The most common AE was bleeding in 60% of cases (3/5), followed by stent occlusion (1/5, 20%) and buried stent syndrome (1/5, 20%). There was a case of bleeding that was graded as severe, which occurred 19 days after the procedure and was managed by angiographic embolization. The other two cases of bleeding were one moderate, resolved with stent replacement, and one self-limiting. The case of buried syndrome was managed conservatively, while the case of stent occlusion, that occurred 20 days after the stent placement, was treated by placing two pigtail stents within the LAMS.

4. Discussion

The present study confirms that EUS-D for POFC has high clinical and technical success, in line with the current literature on this specific topic, with acceptable complication rates.

POFCs remain a major cause of postoperative morbidity following abdominal surgery, in particular pancreatic surgery. They can cause symptoms such as severe pain and gastric outlet obstruction and can lead to complications such as infectiosn, which is the most common and it is associated with high mortality and morbidity rates, or vascular erosion, caused by enzymatic action of pancreatic juice which erodes the walls of major arteries, causing potentially life-threatening hemorrhages. This complication, known as pseudoaneurysm, requires immediate intervention in about 9% of cases [

4,

17], often in the form of angiographic embolization or, in extreme cases, emergency surgery.

Several studies have demonstrated that preoperative pancreatic duct stenting can reduce the incidence of POPF following distal pancreatectomy suggesting that managing pancreatic duct pressure effectively could play a crucial role in mitigating the risk of POPF formation, but despite these theoretical benefits of prophylactic preoperative pancreatic duct stenting, this procedure is not currently recommended in clinical practice due to the lack of robust evidence from well-designed, large-scale clinical trials and the potential risks associated with the procedure [

19].

Historically, both surgery and PCD have been the mainstays of treatment for symptomatic POFCs. However, these methods are associated with significant drawbacks.

Repeating surgery is an invasive method associated with a high risk of morbidity and mortality, particularly in patients already weakened by a previous major surgical procedure, so it is reserved only to selected few cases. A valid treatment method is PCD in which a catheter is inserted into the collection under ultrasound or CT guidance. Although it has shown better outcomes compared to surgical therapies [

14], PCD has a success rate at first attempt of only 65%. Clear disadvantages of this option are that the tube needs to be maintained in place until the resolution of POFC, with an impaired quality of life, a risk of continuous external pancreatic fistula [

1,

4] and it is less successful in infected collection, especially in the presence of necrosis, which can lead to tube obstruction [

1].

Since the first description of EUS-D of pseudocyst by Giovannini et al., interventional EUS has expanded its indications becoming the first line therapy for drainage of symptomatic collections, mainly those following an acute pancreatitis, whose literature is redundant, but also from other etiology such as bilomas, subphrenic or pelvic abscess [

13,

20], as well as POFC, owing its provided safety and efficacy [

21], and our study confirms that EUS-D for POFC has a high clinical (96%) and technical success (98%) in line with the current literature.

A comparative study published by Téllaz-Avila et al. between EUS-D and PCD demonstrates that EUS-D is at least as effective and safe as PCD in patients with POFC, with a comparable technical success (100% vs 91%; P = 0.25), clinical success (100% vs 84%; P = 0.13), recurrence (31% vs 25%; P = 0.69), hospital stay days (median 22 vs 27; P = 0.35), complications (0% vs 6%; P = 0.3), and mortality (8% vs 6%; P = 0.9), with the advantage of not requiring external drainage [

21].

Another recent meta-analysis by Khizar et al. showed that EUS-D is safe and efficient for PFC, whatever its etiology, with higher clinical success rate OR 2.23 (95% CI 1.45, 3.41), lower mortality rate OR 0.24 (95% CI 0.09, 0.67) and re-interventions OR 0.25 (95% CI 0.16, 0.40) compared with PCD [

22].

Traditionally, the EUS-D of POFCs has relied on tools originally developed for EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and the use of wires and DPPSs designed for ERCP [

23]. Although DPPSs offer some advantages, such as reducing the risk of stent migration and being relatively cost-effective, their use presents several significant limitations [

24,

25].

One of the primary challenges associated with DPPSs is their small stent diameter, which makes them particularly susceptible to occlusion. Moreover, the placement of these stents is technically demanding, as it requires repeated wire access across the collection, a process that is not only time-consuming but also increases the procedural complexity for the physician.

In addition, draining POFCs using DPPSs may involve the placement of multiple stents to achieve adequate drainage, especially in cases of WON [

26] and achieving resolution in such cases often requires multiple revisions and stent exchanges, further adding to the procedural burden and increasing the overall risk of complications.

Theoretically, the wider lumen of the LAMS has been thought to offer a faster resolutione compared with plastic stents, with a better infection control, however, any difference in clinical efficacy between the two methods has yet been established. [

27].

To the best of our knowledge, only two randomised studies were conducted to compare the outcomes of LAMS and DPPSs.

The first one was published in 2019 by Bang

et al, and it failed to demonstrate any significant difference in terms of clinical or technical success, including the number of procedures needed [

28]. The second and more recent was published in 2023 by Kastensen et al. including only large WON (>15 cm) affecting 42 patients. The results showed that LAMS were not superior to DPPSs in terms of clinical success, the need for necrosectomy, length of hospital stay, or AE rates. Both techniques proved effective, with an overall mortality rate of 5%. The study concludes that DPPS remains a viable alternative, particularly in resource-limited settings [

27].

Most of the patients in our study underwent electrocautery-enhanced LAMS placement (N 29/47, 62%), likely due to its ease of use and efficiency, demonstrating a good clinical efficacy and safety, with a technical success of 100% (N 30/30), a clinical success of 97% (N 29/30) and rate of AEs of 13% (N 4/30), mostly graded as mild (N 3/4, 75%), in line with the current literature.

Moreover, data from literature supports the use of LAMSs for WON, due to the possibility of allowing entry the cyst cavity and to perform DEN and intensive lavage as well [

29,

30]. Seven patients in our study underwent at least one necrosectomy session due to the presence of solid debris in the collection.The rate of overall AEs in our study was 11%, with no evidence of fatal ones. Most of the AEs occurred during the endoscopic procedure, and their severity was mostly mild (only one severe). Bleeding was the most common complication, in line with the rate of AEs on this specific topic of the most recent studies. One patient experienced buried stent syndrome, a relatively rare complication where the stent becomes embedded in the tissue becoming difficult to remove. This condition can potentially lead to chronic infection or abscess formation and may require surgical intervention to resolve as reported in our study.

EUS-D, while offering numerous benefits, has its own limitations and challenges; first of all the technical complexity of the procedure, which requires a high level of expertise of the endoscopist, influencing the rate of positive procedural outcome, particularly in complex cases involving large or multiloculated collections, or collections located in difficult-to-access areas such as far away from the gastrointestinal wall [

31]. Another issue is represented by the higher procedural costs compared to PCD. Despite these aspects, EUS- D offers some important advantages, like providing the opportunity to visualize anatomically relevant structures, such as the involvement of surrounding organs and vessels by the collection. In addition to its technical feasibility and safety, EUS-D has also been shown to improve quality of life and reduce the risk of infection. Even in patients with infectious POFC, draining the fluid into the stomach via EUS-D did not result in fever, gastroenteritis, or retrograde infection. Furthermore, EUS-D prevents fluid and electrolyte loss, which can occur after PCD, and reduces the risk of persistent collections and fistula. [

14].

Patients who do not respond to minimally invasive endoscopic or radiologic treatments are usually managed surgically. However, emerging endoscopic approaches using agents like N-Butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) —a non-biologic glue already used in vascular and gastrointestinal procedures— in combined or not with a metallic coil to prevent glue migration, have shown promise for closing pancreatic fistulas [

32,

33]. Although based on limited data, this combined method could offer a viable alternative for challenging cases.

While our study provides valuable insights into the management of POFCs, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The retrospective nature of the study may introduce selection bias. Additionally, the lack of a control group (e.g., patients managed with percutaneous drainage or surgery) limits the ability to directly compare the efficacy of EUS-guided drainage with other treatment modalities.Furthermore our study did not provide any results about the timing of EUS-D, which still remains an open issue [

4], conversely to PFCs after acute pancreatitis in which a lot of evidence has been created. Storm et al. compared clinical outcomes in acute (<2 weeks), early (<4 weeks), and delayed EUS-D for POFCs and found no significant differences in clinical success (95%, 93%, and 94%, respectively) and AEs (21.4%, 15.0%, and 30.3%, respectively) [

34]. Oh et al. also evaluated clinical outcomes according to the presence of encapsulation in addition to the timing of EUS-D. Technical success, clinical success, and AE rates were also similar between early and delayed interventions [

35]. It is fair to say that, while encapsulation is emphasized in PFCs after acute pancreatitis to determine the timing of interventions, it is still unclear whether encapsulation of POFCs might favorably affect the clinical outcomes, especially the safety, of early drainage and further prospective studies are needed to evaluate the appropriate timing.

Data are also lacking regarding the role of ERCP in managing POFCs. ERCP can be also an option for POFCs due to pancreatic disruption or leak after distal pancreatectomy but it is less frequently reported than EUS-D [

4]. Treatment options are represented by pancreatic sphincterotomy, nasopancreatic duct tube placement, plastic stent placement, or a combination of these. Furthermore, conventional ERCP is not always technically possible owing to the surgically altered anatomy (e.g. after duodenocephalopancreasectomy), and balloon enteroscope-assisted ERCP (BE-ERCP) is necessary, but data on BE-ERCP are limited, with a technical success rates of BE-ERCP for pancreatic indications that are not as high as those for biliary indications. Thus, expertise in both BE-ERCP and EUS-guided pancreatic duct drainage is important for managing cases after pancreaticoduodenectomy[

4].

Further and more comprehensive studies are needed to strongly confirm EUS-D as first line therapy for POPFs and its balance between pros and cons.