Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

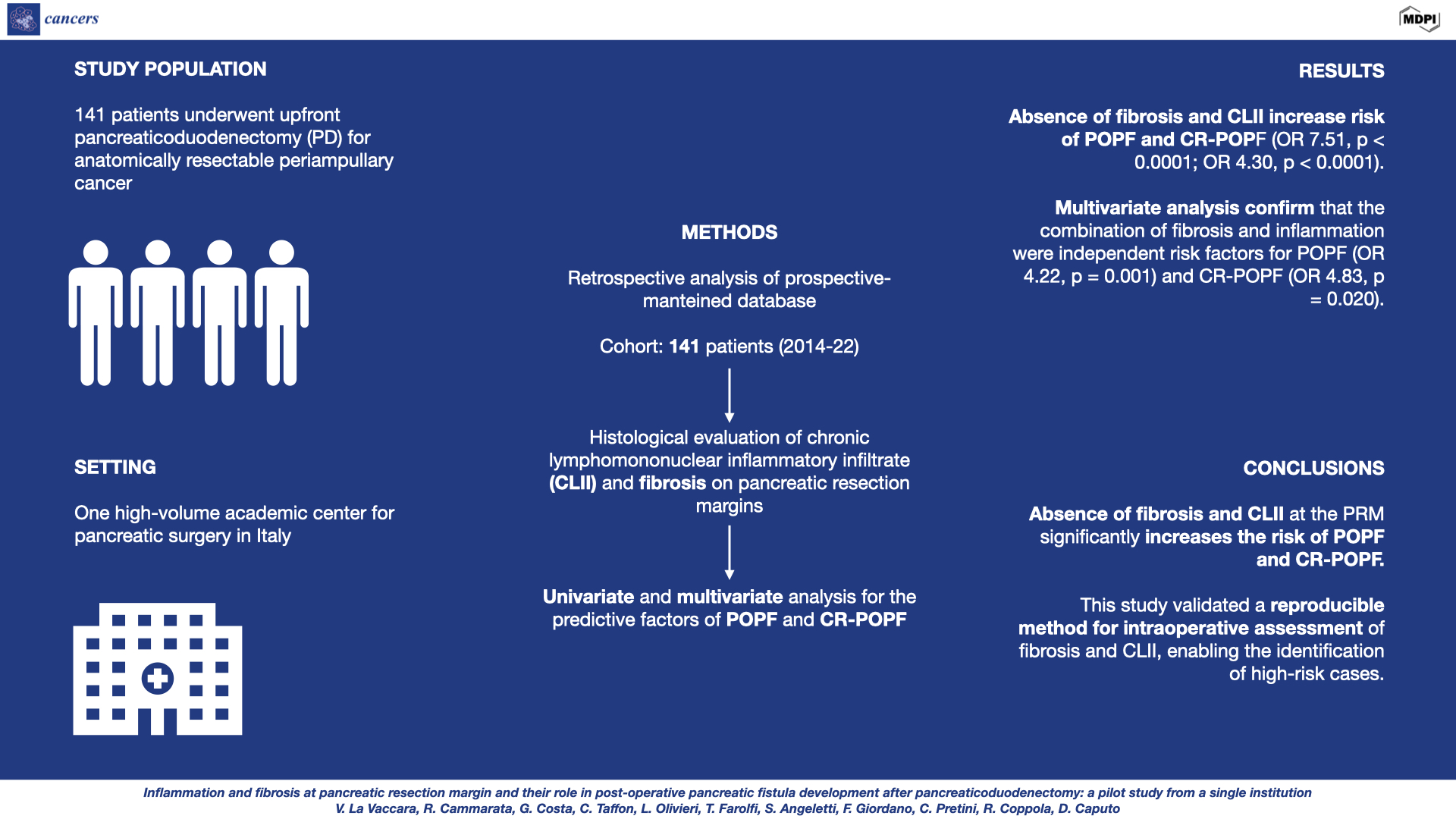

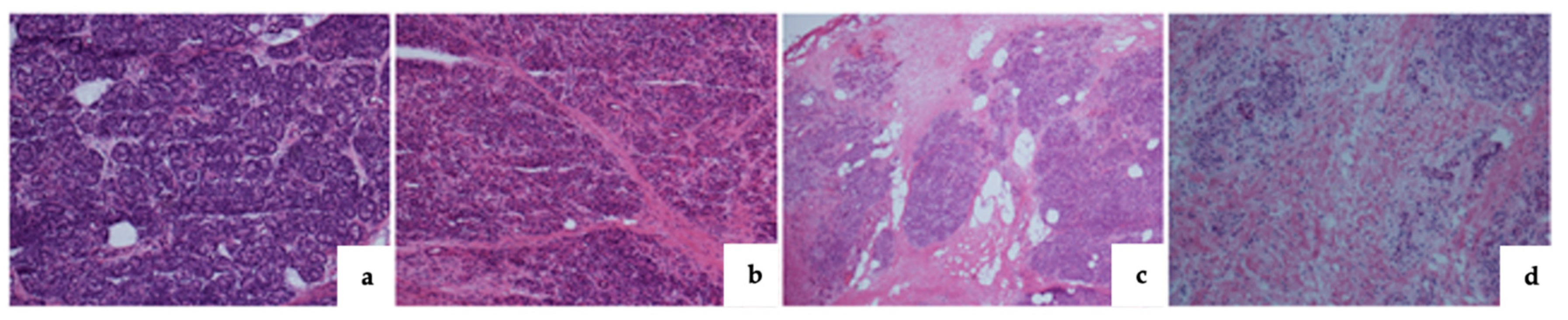

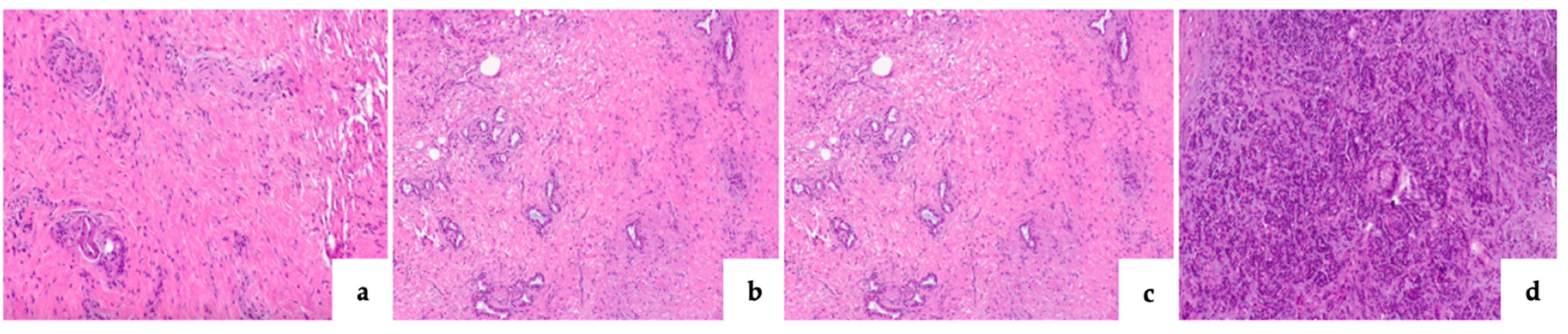

Background/Objectives: The absence of pancreatic fibrosis is a known risk factor for post-operative pancreatic fistula (POPF) following pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD). Emerging evidence suggests inflammation plays a role in anastomotic healing. This study aimed to assess the role of chronic lymphomononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (CLII) and fibrosis at the pancreatic resection margin (PRM) on POPF development and explored a method for its intraoperative prediction. Materials and Methods: Data from 141 patients who underwent PD between 2014 and 2022 were retrospectively analyzed. PRM were histologically evaluated for fibrosis and CLII. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify potential predictors of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) and clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula (CR-POPF). Results: The histopathological analysis of intraoperative frozen sections of the PRM showed a strong association between the absence of fibrosis and CLII and increased risk of POPF and CR-POPF (OR 7.51, p < 0.0001; OR 4.30, p < 0.0001). Multivariate analysis further identified a main pancreatic duct diameter of less than 3 mm, as well as the combined presence of fibrosis and inflammation, as independent risk factors for developing POPF (OR 4.22, p = 0.001) and CR-POPF (OR 4.83, p = 0.020). Conclusion: The absence of fibrosis and CLII at the PRM significantly increases the risk of POPF and CR-POPF. This study validated a reproducible method for intraoperative assessment of fibrosis and CLII, enabling the identification of high-risk cases. Such a tool could guide surgical strategies to mitigate POPF-related complications, improving patient outcomes after PD.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Correlation of Pancreatic Fibrosis, Lymphomononuclear Inflammatory Infiltrate, Main Pancreatic Duct Diameter and Pancreatic Texture with POPF

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| POPF | Post-operative Pancreatic Fistula |

| CR-POPF | Clinically Relevant Post-Operative Pancreatic Fistula |

| PD | Pancreaticoduodenectomy |

| PRM | Pancreatic Resection Margin |

| CLII | Chronic Lymphomononuclear Inflammatory Infiltrate |

| IFS | Intraoperative Frozen Sections |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists classification |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| PDAC | Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma |

| AC | Ampullary Carcinoma |

| CCA | Cholangiocarcinoma |

| NET | Neuroendocrine Tumor |

| IPMN | Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm |

| MCN | Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm |

| DGE | Delayed Gastric Emptying |

| PPH | Post-pancreatectomy Hemorrhage |

| PPAP | Post-pancreatectomy Acute Pancreatitis |

| NAT | Neoadjuvant Therapy |

| MPD | Main Pancreatic Duct |

References

- Smits F.J.; van Santvoort H.C.; Besselink M.G.; et al. Management of severe pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. JAMA Surg. 2017,152,540-548.

- McMillan M.T.; Soi S.; Asbun H.J. et al. Risk-adjusted outcomes of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula following pancreatoduodenectomy: a model for performance evaluation. Ann Surg. 2016, 264, 344-352.

- Harnoss J.C.; Ulrich A.B.; Harnoss J.M.; et al. Use and results of consensus definitions in pancreatic surgery: a systematic review. Surgery 2014, 155, 47–57.

- Bassi C.; Dervenis C.; Butturini G.; et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005, 138(1), 8-13.

- Bassi C.; Marchegiani G; Dervenis C.; et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery 2017,161(3), 584-591.

- Chen J.Y.; Feng J.; Wang X.Q.; Cai S.W.; Dong J.H.; Chen Y.L.; Risk scoring system and predictor for clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015, 21(19), 5926-5933.

- Mungroop T.H.; van Rijssen L.B.; van Klaveren D.; et al. Alternative Fistula Risk Score for Pancreatoduodenectomy (a-FRS): Design and International External Validation. Ann Surg. 2019, 269(5), 937-943.

- La Vaccara V.; Coppola A.; Cammarata R.; Olivieri L.; Farolfi T.; Coppola R.; Caputo D.; Right hepatic artery anomalies in pancreatoduodenectomy - a risk for arterial resection but not for postoperative outcomes. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2023, 14(5), 2158-2166.

- Caputo D.; Coppola A.; La Vaccara V.; Passa R.; Carbone L.; Ciccozzi M.; Angeletti S.; Coppola R.; Validations of new cut-offs for surgical drains management and use of computerized tomography scan after pancreatoduodenectomy: The DALCUT trial. World J Clin Cases 2022, 10(15), 4836-4842.

- Coppola A.; La Vaccara V.; Angeletti S.; Spoto S.; Farolfi T.; Cammarata R.; Maltese G.; Coppola R.; Caputo D.; Postoperative procalcitonin is a biomarker for excluding the onset of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2023, 14(2), 1077-1086.

- Coppola A.; La Vaccara V.; Farolfi T.; Fiore M.; Cascone C.; Ramella S.; Spoto S.; Ciccozzi M.; Angeletti S.; Coppola R.; Caputo D.; Different Biliary Microbial Flora Influence Type of Complications after Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Single Center Retrospective Analysis. J Clin Med. 2021, 10(10), 2180.

- Clavien P.A.; Barkun J.; de Oliveira M.L.; et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009, 250, 187-96.

- Timme S.; Kayser G.; Werner M.; et al. Surgeon vs Pathologist for Prediction of Pancreatic Fistula: Results from the Randomized Multicenter RECOPANC Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2021, 232(6), 935-945.

- Wellner U.F.; Kayser G.; Lapshyn H.; et al. A simple scoring system based on clinical factors related to pancreatic texture predicts postoperative pancreatic fistula preoperatively. HPB 2010, 12(10), 696-702.

- Malgras B.; Dokmak S.; Aussilhou B.; Pocard M.; Sauvanet A.; Management of postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Visc Surg. 2023, 160(1), 39-51.

- McMillan M.T.; Allegrini V.; Asbun H.J.; et al. Incorporation of procedure-specific risk into the ACS-NSQIP surgical risk calculator improves the prediction of morbidity and mortality after pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2017, 265, 978e986.

- Pedrazzoli S.; Pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) and postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF): a systematic review and analysis of the POPF-related mortality rate in 60.739 patients retrieved from the English literature published between 1990 and 2015. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017, 96e6858.

- Balzano G.; Zerbi A.; Aleotti F.; Capretti G.; Melzi R.; Pecorelli N.; Mercalli A.; Nano R.; Magistretti P.; Gavazzi F.; De Cobelli F.; Poretti D.; Scavini M.; Molinari C.; Partelli S.; Crippa S.; Maffi P.; Falconi M.; Piemonti L.; Total Pancreatectomy With Islet Autotransplantation as an Alternative to High-risk Pancreatojejunostomy After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Ann Surg. 2023, 277(6), 894-903.

- Parray A.M.; Chaudhari V.A.; Shrikhande S.V.; Bhandare M.S.; Mitigation strategies for post-operative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy in high-risk pancreas: an evidence-based algorithmic approach"- a narrative review. Chin Clin Oncol. 2022, 11(1), 6.

- Tajima Y.; Kuroki T.; Tsuneoka N.; et al. Anatomy-specific pancreatic stump management to reduce the risk of pancreatic fistula after pancreatic head resection. World J Surg. 2009, 33(10), 2166-2176.

- Schuh F.; Mihaljevic A.L.; Probst P.; et al. A Simple Classification of Pancreatic Duct Size and Texture Predicts Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula: A classification of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery. Ann Surg. 2023, 277(3), 597e608.

- Marchegiani G.; Barreto S.G.; Bannone E.; Sarr M.; Vollmer C.M.; Connor S.; Falconi M.; Besselink M.G.; Salvia R.; Wolfgang C.L.; Zyromski N.J.; Yeo C.J.; Adham M.; Siriwardena A.K.; Takaori K.; Hilal M.A.; Loos M.; Probst P.; Hackert T.; Strobel O.; Busch O.R.C.; Lillemoe K.D.; Miao Y.; Halloran C.M.; Werner J.; Friess H.; Izbicki J.R.; Bockhorn M.; Vashist Y.K.; Conlon K.; Passas I.; Gianotti L.; Del Chiaro M.; Schulick R.D.; Montorsi M.; Oláh A.; Fusai G.K.; Serrablo A.; Zerbi A.; Fingerhut A.; Andersson R.; Padbury R.; Dervenis C.; Neoptolemos J.P.; Bassi C.; Büchler M.W.; Shrikhande S.V.; International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery. Postpancreatectomy Acute Pancreatitis (PPAP): Definition and Grading From the International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Ann Surg. 2022, 275(4), 663-672.

- Seraphim P.M.; Leal E.C.; Moura J.; Gonçalves P.; Gonçalves J.P.; Carvalho E.; Lack of lymphocytes impairs macrophage polarization and angiogenesis in diabetic wound healing. Life Sci 2020, 254, 117813.

- Wynn T. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol 2008, 214(2),199-210.

- Long H.; Lichtnekert J.; Andrassy J.; Schraml B.U.; Romagnani P.; Anders H.J.; Macrophages and fibrosis: how resident and infiltrating mononuclear phagocytes account for organ injury, regeneration or atrophy. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1194988.

- Coppola A.; La Vaccara V.; Caggiati L.; et al. Utility of preoperative systemic inflammatory biomarkers in predicting postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy: Literature review and single center experience. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021,13(10), 1216-1225.

- McMillan M.T.; Malleo G.; Bassi C.; et al. Multicenter, Prospective Trial of Selective Drain Management for Pancreatoduodenec,tomy Using Risk Stratification. Ann Surg 2017, 265, 1209-18.

- Marchegiani G.; Perri G.; Burelli A.; Zoccatelli F.; Andrianello S.; Luchini C.; Donadello K.; Bassi C.; Salvia R.; High-risk Pancreatic Anastomosis Versus Total Pancreatectomy After Pancreatoduodenectomy: Postoperative Outcomes and Quality of Life Analysis. Ann Surg 2022, 276(6), e905-e913.

- Zaghal A.; Tamim H.; Habib S.; Jaafar R.; Mukherji D.; Khalife M.; Mailhac A.; Faraj W.; Drain or No Drain Following Pancreaticoduodenectomy: The Unsolved Dilemma. Scand J Surg 2020, 109(3), 228-237.

- Hilst J.; D'Hondt M.; Ielpo B.; Keck T.; Khatkov I.E.; Koerkamp B.G.; Lips D.J.; Luyer M.D.P.; Mieog J.S.D.; Morelli L.; Molenaar I.Q.; van Santvoort H.C.; Sprangers M.A.G.; Ferrari C.; Berkhof J.; Maisonneuve P.; Abu Hilal; Besselink M.G.; European Consortium on Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery (E-MIPS). Minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic and peri-ampullary neoplasm (DIPLOMA-2): study protocol for an international multicenter patient-blinded randomized controlled trial. Trials 2023, 24(1), 665.

| Variable | Total | POPF-no | POPF-yes | P-value | CR-POPF-no | CR-POPF-yes | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 141 (100) | 81 (57.4) | 60 (42.5) | 109 (77.3) | 32 (22.7) | ||

| Age, y, (median) | 72 | 72 | 71.5 | 0.6601 | 72 | 71 | 0.765 |

| Sex, n (%) • Female • Male |

63 (44.6) 78 (55.3) |

36 (44.4) 45 (55.5) |

27 (45) 33 (55) |

0.9477 |

49 (44.9) 60 (55) |

14 (437) 18 (56.2) |

0.9041 |

| ASA n (%) • I • II • III • IV |

1 (1.23) 39 (48) 37 (45.6) 4 (4.9) |

1 (1.66) 28 (46.6) 24 (40) 7 (11.6) |

0.5090 |

1 (0.91) 53 (48.6) 50 (45.8) 5 (4.5) |

1 (3.1) 14 (43.7) 11 (34.3) 6 (18.7) |

0.0441* |

|

| BMI, kg/m2 (mediana) | 28 | 28 | 28.5 | 0.6456 | 28 | 28.5 | 0.2353 |

| Alcoholic Habit, n (%) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (3.3) | 0.3932 | 1 (0.9) | 2 (6.25) | 0.6568 |

| Smoking Habit, n(%) | 43 (30.4) | 23 (28.3) | 20 (33.3) | 0.5289 | 31 (28.4) | 12 (37.5) | 0.3277 |

| DM (%) | 31 (21.9) | 20 (24.6) | 11 (18.3) | 0.3674 | 25 (22.9) | 6 (18.7) | 0.6152 |

| Hypertension (%) | 70 (49.6) | 41 (50.6) | 29 (48.3) | 0.0766 | 54 (49.5) | 16 (50) | 0.9636 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment (%) | 10 (7.0) | 7 (8.6) | 3 (5) | 0.4049 | 10 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0.0755 |

| Type of disease (%) • PDAC • AC • CCA • NET • IPMN • MCN • Clear cells |

110 (78.0) 3 (2.1) 11 (7.8) 7 (4.9) 6 (4.2) 3 (2.1) 1 (0.7) |

68 (83.9) 1 (1.2) 3 (3.7) 2 (2.4) 4 (4.9) 3 (3.7) 0 (0) |

42 (70) 2 (3.3) 8 (13.3) 5 (8.3) 2 (3.3) 0 (0) 1 (1.6) |

0.0480* 0.3932 0.0350* 0.1130 0.6406 0.1319 0.2436 |

88 (80.7) 2 (1.83) 5 (4.5) 5 (4.5) 5 (4.5) 3 (2.7) 1 (0.9) |

22 (68.7) 1 (3.1) 6 (18.7) 2 (6.2) 1 (3.1) 0 (0) 0 (0) |

0.1501 0.6566 0.0086* 0.7034 0.7186 0.3428 0.5866 |

| Intraoperative bleeding, mL, (median) | 300 | 300 | 300 | 0.3233 | 300 | 300 | 0.4021 |

| Operative time, median | 375 | 371 | 376.5 | 0.6060 | 364 | 382.5 | 0.6501 |

| DGE (%) | 50 (35.4) | 21 (25.9) | 29 (48.3) | 0.0060* | 28 (25.6) | 22 (68.7) | <0.0001* |

| PPH (%) | 24 (17.0) | 4 (4.9) | 20 (33.3) | <0.0001* | 8 (7.3) | 15 (46.8) | <0.0001* |

| 90 days mortality (%) | 17 (12.0) | 6 (7.4) | 11 (18.3) | 0.0488* | 11 (10) | 6 (18.7) | 0.1860 |

| Tipe of surgery (%) • Whipple • Traverso |

41 (29) 100 (71) |

21 (25.9) 60 (74) |

20 (33.3) 40 (66.6) |

0.3383 |

31 (28.4) 78 (71.5) |

10 (31.2) 22 (68.7) |

0.7583 |

| Reintervention (%) | 19 (13.4) | 6 (7.4) | 13 (21.6) | 0.5609 | 10 (9.1) | 9 (28.1) | 0.0058* |

| Length of Stay (%) | 13 (9.2) | 9 (11.1) | 19.5 (32.5) | 0.0001* | 11 (10) | 27 (84.3) | 0.0001* |

| ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification; BMI, body Max Index; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; AC, ampullary carcinoma; CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; NET, neuroendocrin tumor; IPMN, Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm; MCN, mucinous cystic neoplasm; DGE, Delayed Gastric Empty; PPH, Post-Pancreatectomy Hemorrage. | |||||||

| Variable | POPF-no n (%) |

POPF-yes n (%) |

P-value | CR-POPF-no n (%) |

CR-POPF-yes n (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPD diameter < 3 mm > 3 mm |

22 (27.1) 59 (72.8) |

36 (60) 23 (38.3) |

0.0001* |

38 (34.8) 71 (65.1) |

20 (62.5) 11 (34.3) |

0.00031* |

| Pancreatic texture (evaluation by surgeon) Soft Hard |

41 (50.6) 40 (49.3) |

41 (68.3) 19 (31.6) |

0.0350* |

63 (57.7) 46 (42.2) |

19 (59.3) 13 (40.6) |

0.8737 |

| New ISGPS classification A (hard + ≥3 mm) B (hard + <3 mm) C (soft + ≥3 mm) D (soft + <3 mm) |

27 (33.3) 13 (16.0) 32 (39.5) 9 (11.1) |

8 (13.3) 11 (18.3) 15 (25) 26 (43.3) |

0.0005* | 30 (27.5) 16 (14.6) 41 (37.6) 22 (20.1) |

5 (15.6) 8 (25) 6 (18.7) 13 (40.6) |

0.0206* |

| Pancreatic fibrosis Grade 0 Grade I Grade II Grade III |

12 (14.8) 17 (20.9) 16 (19.7) 34 (41.9) |

34 (56.6) 17 (28.3) 8 (13.3) 1 (1.6) |

<0.0001* |

27 (24.7) 26 (23.8) 20 (18.3) 34 (31.1) |

19 (59.3) 8 (25) 4 (12.5) 1 (3.1) |

0.0062* |

| CLII Grade 0 Grade I Grade II Grade III |

39 (48.1) 32 (39.5) 7 (8.6) 1 (1.2) |

48 (80) 11 (18.3) 1 (1.6) 0 (0) |

0.0049* |

61 (55.9) 38 (34.8) 7 (6.4) 1 (0.9) |

26 (81.2) 5 (15.6) 1 (3.1) 0(0) |

0.0934 |

| *Statistically significant; MPD, main pancreatic duct CLII, chronic lymphomononuclear inflammatory infiltrate; POPF, post-operative pancreatic fistuale; CR-POPF, clinically relevant POPF | ||||||

| Variable | POPF-no Vs. POPF-yes | CR-POPF-no Vs. CR-POPF-yes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Grade 0 fibrosis | 7.51 | 3.08 – 18.3 | <0.0001* | 4.43 | 1.85 – 10.6 | 0.0003* |

| Grade 0 CLII | 4.30 | 1.90 – 9.73 | 0.0001* | 3.40 | 1.26 – 9.19 | 0.0099* |

| Grade 0 fibrosis and CLII | 5.20 | 2.23 – 12.1 | <0.0001* | 4.83 | 1.27 – 18.3 | 0.0200* |

| Histopathological evaluation | Surgeon evaluation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic fibrosis | Pancreatic texture | ||

| Soft (82) | Hard (59) | P-value | |

| <0.0001* | |||

| Grade 0 | 10 (12.1) | 36 (61.0) | |

| Grade I | 9 (11.1) | 25 (42.3) | |

| Grade II | 17 (20.7) | 7 (11.8) | |

| Grade III | 23 (28.0) | 12 (20.3) | |

| *Statistically significant. | |||

| Variable | No POPF Vs. POPF | No CR-POPF Vs. CR-POPF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age, y | 1.02 | 0.97-1.07 | 0.329 | 0.99 | 0.94-1.04 | 0.754 |

| Sex, male Vs. female | 1.35 | 0.59-3.04 | 0.467 | 1.48 | 0.58-3.75 | 0.404 |

| BMI > 30 kg/m2 | 2.61 | 0.71-9.59 | 0.148 | 3.12 | 0.59-16.4 | 0.178 |

| NAT, yes Vs. not | 1.35 | 0.52-3.50 | 0.536 | 1 | ||

| Operative time | 1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.377 | 0.99 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.453 |

| Blood loss, >300 mL | 0.99 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.415 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.512 |

| MPD < 3mm | 4.22 | 1.80-9.88 | 0.0001* | 3.1 | 1.19-8.07 | 0.020* |

| No fibrosis and CLII | 5.44 | 2.11-14.00 | 0.0001* | 4.83 | 1.27-18.3 | 0.020* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).