1. Introduction

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is a widely performed procedure for administering enteral nutrition to patients who cannot maintain adequate oral intake. Introduced in the 1980s, PEG has transformed the field of nutritional support for critically ill patients, offering a minimally invasive and efficacious feeding method [

1].

In the intensive care unit (ICU), PEG is a frequently applied procedure for patients who require long-term nutritional support [

2]. These patients often present with a range of underlying conditions, including traumatic brain injury, stroke, advanced neurodegenerative disease, or severe respiratory conditions necessitating prolonged intubation. Malnutrition and its associated complications represent a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality in the ICU setting. PEG is critical in reducing these risks by ensuring adequate enteral caloric intake and improving clinical outcomes [

3]. The procedure requires inserting a feeding tube directly into the stomach through the abdominal wall with endoscopic guidance. This technique is particularly beneficial in conditions such as neurological disorders, prolonged mechanical ventilation, oropharyngeal dysphagia, and malignancies, of which oral intake is compromised chiefly for extended periods [

4].

Steatotic liver disease (SLD) is a highly prevalent condition characterized by fat accumulation within liver cells. It is frequently associated with metabolic conditions (i.e., obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia; recently named as metabolic associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in these conditions), drug use, genetic predisposition, and alcohol consumption [

5,

6]. In critically ill patients, hepatosteatosis has the potential to aggravate systemic inflammation and complicate metabolic homeostasis. Patients with hepatosteatosis are particularly at risk of complications related to nutrition and metabolism, including impaired hepatic function and an increased risk of sepsis [

7]. The Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index is a non-invasive diagnostic tool used to estimate the risk of liver fibrosis in patients with various liver diseases, including SLD and chronic viral hepatitis [

8]. The FIB-4 score is calculated using a combination of routine laboratory parameters: age, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and platelet count. Its diagnostic ability for hepatic steatosis and fibrosis has been found to be superior to ultrasonography. Thus, it is recommended that patients at high risk of liver fibrosis be screened with this score [

9,

10]. Higher FIB-4 scores indicate a higher risk for liver fibrosis, which is associated with worse clinical outcomes [

9,

10]. In the ICU setting, the FIB-4 index has been demonstrated to be a valuable prognostic tool, as liver fibrosis has been linked to an increased risk of organ dysfunction, infections, and mortality due to impairments in hepatic synthetic and metabolic functions, resulting in the development of hypoalbuminemia, coagulopathy, and altered immune responses [

11].

Recent studies have highlighted the correlation between elevated FIB-4 scores and adverse outcomes in ICU patients, underscoring the significance of early recognition and management of hepatic dysfunction in this population [

12,

13]. The question of why some patients can live longer after the PEG procedure remains unclear in the current literature. If we find some parameters suggesting high mortality risk before the PEG procedure in ICU patients, we can reduce their mortality risk and prolong their survival with comprehensive medical support. In this context, the relationship between PEG tubes and SLD and their role in predicting mortality might be essential to improving patient care in the ICU. The present study explores the associations between hepatic fibrosis risk, biochemical parameters, and mortality among ICU patients undergoing PEG.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We report a single-center retrospective study of PEG consultations sent from the intensive care units of our hospital to the endoscopy unit between January 1, 2022 and December 31, 2024 and followed up for at least 1 month. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of Giresun University Training and Research Hospital on April 16, 2025, with decision number 16.04.2025/03; data of all PEG patients were subsequently collected. Patients who were discharged or referred without follow-up after PEG application, patients who could not tolerate enteral nutrition despite PEG application, nephrotic patients with albuminuria, patients with previous parenchymal liver disease other than hepatosteatosis, patients using hepatotoxic agents or receiving medical treatment that may cause fluctuations in liver enzyme levels, patients with active or chronic hepatitis, and patients under 18 years of age were excluded from the study. Informed consent was not obtained due to the retrospective nature of the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki revised in 2013.

2.2. Data Collection

The demographic characteristics, laboratory and clinical data of these patients were collected during the consultation for the PEG procedure and analyzed retrospectively. The patients who were requested to undergo the PEG procedure were generally those who were hospitalized in the intensive care unit for a long time due to acute myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, pneumonia or malignancy, were intubated with tracheostomy or attempted to continue enteral feeding with a nasojejunal tube, or would need enteral feeding for more than 30 days. After data collection, the patients were divided into “survivors” and “non-survivors” groups. Patients who died in the hospital after the PEG procedure were classified as “non-survivors” regardless of the cause of death. Patients who were able to be discharged from the hospital after the PEG procedure were classified as “survivors”.

The hepatosteatosis data of the patients were presented according to the abdominal ultrasonography (USG) findings routinely performed by the same radiologist before the PEG procedure. Regarding the degree of hepatosteatosis, patients with grade 1 and grade 2 were presented as “hepatosteatosis present” and those without hepatosteatosis were presented as “hepatosteatosis absent”. As recommended in the guidelines, a FIB-4 score of <1.3 indicates low fibrosis risk, a FIB-4 score between 1.3 and 2.67 indicates moderate fibrosis risk and a FIB-4 score>2.67 indicates high fibrosis risk (14).

2.3. PEG Tube Placement

The technique of PEG tube placement was performed in line with the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) practice guidelines [

15]. The same gastroenterologist performed PEG tube insertion using the pull technique under sterile conditions. Thirty minutes before the interventional procedure, 2 g ceftriaxone was administered intravenously as prophylaxis. Depending on the patient’s condition, weight-adjusted midazolam and propofol were administered when sedation was required. After a skin shave, a 1-cm skin incision before insertion of the PEG was applied after positive transillumination in all patients. The PEG tube insertion was performed using the PEG 24® Pull Method (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA). After inserting the PEG tube, the tube was fixed using an exterior retention plate without sutures. The dressing was changed three times a day for the first seven days after the procedure, and water was given through the PEG tube 24 hours after the tube placement. Initially, 100 mL of oral nutritional supplement (ONS) was administered if there were no complications following the PEG procedure. If this was tolerated, an additional 50 mL of ONS was added to the previous volume, as described by Jung et al. [

16].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 26.0 software. The descriptive characteristics of patients who underwent PEG were presented as a number and percentage. Non-normally distributed data were presented as median, minimum, and maximum, while normally distributed data were presented as mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum. The suitability of the data for normal distribution was determined by examining the skewness and kurtosis values. In accordance with standard practice, the reference value for normal distribution is between ±1.96. The remaining variables did not comply with the normal distribution rules except for age, cholesterol, HDL, LDL, ferritin, total protein, albumin, D-dimer, fibrinogen, leucocyte, and sodium values. A Chi-Square Test was employed to evaluate the correlation between mortality and three variables: gender, the presence of hepatosteatosis, and FIB-4 groups. Various numerical parameters concerning mortality were compared using an Independent Sample T-test for data that follows a normal distribution.

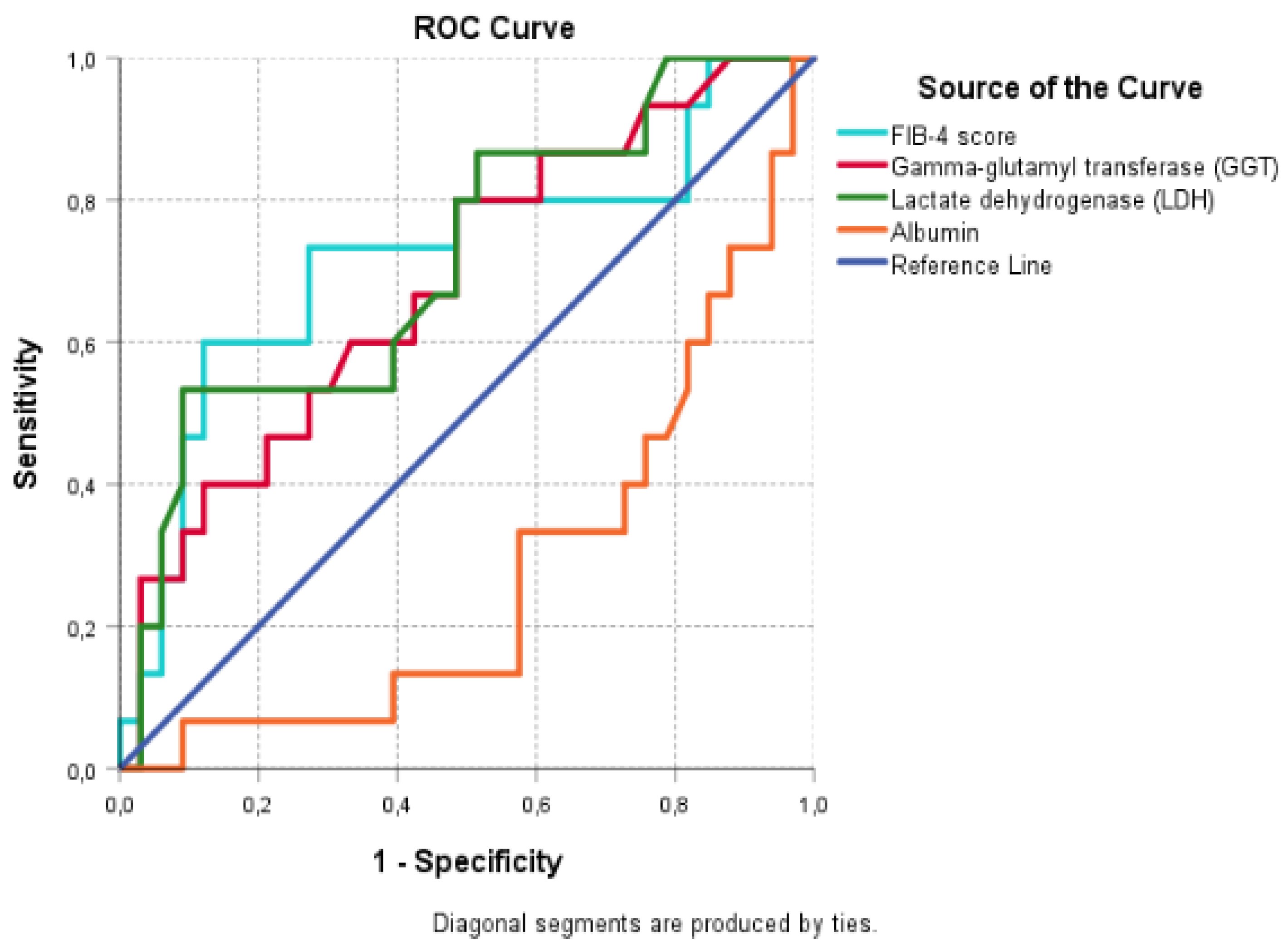

Furthermore, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare the various numerical parameters concerning mortality in non-normally distributed data. The relationships between mortality and all other variables were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient, assuming normality. The correlation coefficient was evaluated as indicating a low-level relationship (0.00-0.30), a medium-level relationship (0.30-0.70), or a high-level relationship (0.70-1.00). A ROC analysis was conducted to assess the mortality risk in patients based on the duration of PEG use, FIB-4, GGT, LDH, and albumin levels. The ROC analysis demonstrates that the size of the area under the ROC curve is a statistically significant predictor of risk of death and probability of survival in patients. The ROC analysis revealed that when there is no ability to discriminate between the probability of patients being exitus or survivors, the expected value of the area under the ROC curve is 0.50. In a perfect test, these values are 1.00. The values under the curve are interpreted as follows: 0.90-1.00 = excellent, 0.80-0.90 = good, 0.70-0.80 = moderate, 0.60-0.70 = poor and 0.50-0.60 = failure. Throughout the study, a significance level of 0.05 and 0.01 was maintained.

3. Results

A total of 155 patients were included in this study, and 6 patients were excluded due to lack of data. The study was completed by analyzing the data of 149 patients, 88 of whom were in the survivor group and 61 in the non-survivor group. The mean age of the survivor group was significantly lower than the non-survivor group (72.94±18.52 vs. 80.11±15.63). The distributions of gender and the presence of hepatosteatosis were not significantly different between the groups. However, there was a difference in the distribution of FIB-4 levels according to the presence of mortality (p<0.05). These data show that the proportion of patients with low fibrosis risk was significantly higher in the survivor group (52.3% vs. 24.6%). The non-survivor group had a significantly higher rate of high fibrosis risk compared to the survivor group (44.3% vs. 10.2%). There was no significant difference regarding the comorbidity numbers of the patients between the groups. The distribution of patients who underwent PEG according to demographic and disease characteristics and the presence of mortality is shown in

Table 1.

There was no significant difference regarding indirect bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), amylase, ALT, total protein, glucose, lactate, cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, D-dimer, fibrinogen, leucocyte, sodium, and potassium levels between the groups. However, AST, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, GGT, LDH, ferritin, CRP, procalcitonin, INR, and PT levels were significantly higher (p=0.031, 0.002, 0.001, 0.024, 0.000, 0.001, 0.000, 0.015, 0.001, 0.01 respectively), whereas albumin, platelet and calcium levels were lower in the non-survivor group (p=0.000, 0.005, 0.02 respectively). Laboratory parameters of the groups are compared in

Table 2.

Age, FIB-4 score, AST, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, GGT, LDH, CRP, INR and PT levels showed low and moderate positive correlations with mortality. Albumin, platelet and calcium levels showed low and moderate negative correlations with mortality. No correlation was observed between other parameters and mortality. The results of the correlation analysis between mortality and the parameters of the groups are presented in

Table 3.

A ROC analysis was performed using the FIB-4 score, GGT, LDH, and albumin values to determine the patients’ mortality risk. We excluded variables with a significant but weak correlation (a correlation coefficient below 0.3) from the analysis. Variables with a correlation value above 0.3 (moderate correlation) were included in the ROC analysis.

Table 4 and

Figure 1 present the results of the ROC analysis for mortality prediction of patients who underwent PEG procedures in the ICU.

The ROC analysis revealed that FIB-4, GGT, and LDH levels were significant in predicting the risk of death, and albumin level was significant in predicting the survival probability (p= 0.015, 0.042, 0.019, and 0.000, respectively). The FIB-4 score, GGT, and LDH levels were found to be moderately effective in predicting the risk of death of the patients, while albumin levels were moderately effective in predicting the survival probability of the patients. The FIB-4 cut-off value was 1.50, with a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 58%. The cut-off values for both GGT and LDH were 28.50 and 194.50, respectively. Both variables showed sensitivity and specificity values of 80% and 52%, respectively. The cut-off value for albumin was 28.20, with a sensitivity and specificity of 63% and 73%, respectively. When we compared the predictive ability of the FIB-4 score, GGT, and LDH levels for mortality, FIB-4 was superior to GGT and LDH levels (AUC: 0.72, 0.69, and 0.71, respectively).

4. Discussion

This study analyzes the prognostic indicators associated with mortality in ICU patients undergoing PEG. Considering hepatic fibrosis risk, as evaluated by the FIB-4 index, and pivotal laboratory variables, including GGT, LDH, and albumin, our findings contribute to the expanding knowledge base on critical care nutrition and hepatology. The findings highlight the complex relationship between hepatic dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and nutritional support in critically ill patients. The analysis revealed a significant association between older age and increased mortality in PEG patients. This finding is consistent with that of previous studies which have documented the impact of age-related physiological decline and comorbidities on ICU outcomes [

17]. Furthermore, gender was found to exert no significant influence on mortality, which aligns with existing literature that suggests minimal sex-based differences in PEG-related outcomes.

One noteworthy finding is the strong correlation between elevated FIB-4 scores and mortality rates. Patients with higher FIB-4 scores, indicative of advanced hepatic fibrosis risk, were significantly more likely to die. This observation is consistent with prior research, demonstrating that liver fibrosis increases systemic inflammation, impairs hepatic metabolism, and predisposes patients to multi-organ dysfunction. Recent studies suggesting chronic inflammation as one of the key pathophysiologic factors for MASLD might explain this potential bi-directional relationship between hepatic fibrosis risk and critical illness. For example, a study by Li X et al. reported similar associations between high FIB-4 levels and adverse outcomes in critically ill patients, underscoring the benefit of using the FIB-4 score as a prognostic tool [

18,

19,

20].

The elevated GGT, LDH, CRP, and ferritin levels observed in non-survivors indicate underlying inflammatory and metabolic derangements. These markers are involved in oxidative stress and cellular injury, which are aggravated in the ICU setting. The protective role of higher albumin levels, as observed in our study, is consistent with its well-established functions in maintaining oncotic pressure, modulating inflammation, and serving as a nutritional marker [

21,

22].

The findings have significant implications for clinical practice. Firstly, the admission FIB-4 score might be used to evaluate ICU patients undergoing PEG to determine their mortality risk and its increased levels alarm the clinicians for appropriate management strategies. Patients with elevated FIB-4 scores may benefit from closer monitoring, early nutritional intervention, and tailored therapies to reduce hepatic and systemic inflammation. Secondly, incorporating laboratory markers, including GGT, LDH, and albumin, into risk assessment protocols can enhance the predictive accuracy for mortality and inform clinical decision-making. Although previous studies have examined the prognostic value of hepatic biochemical markers in various clinical settings, Our study is one of the studies investigating these parameters in the context of PEG use in critically ill patients. [

23,

24]. These findings align with the observations made by Fix et al., who also identified comparable trends in patients with advanced liver disease [

25].

The study’s retrospective nature may introduce biases affecting the reliability of the findings. The results may not apply elsewhere due to the single-institution study design and differences in patient characteristics. The sample of 149 patients is valuable, but more extensive studies may offer more robust and generalizable conclusions. The analysis might not account for all confounding factors, such as ICU management, comorbidity, etiologic heterogeneity of ICU patients, or nutrition, which could influence outcomes. The study focuses on ICU mortality and PEG usage. Long-term outcomes and complications were not assessed. Heterogeneity in PEG placement indications among patients (e.g., neurological disorders, malignancies) may confound mortality predictor analysis. The study includes key biochemical parameters but could be more detailed with additional markers. It is observational and does not evaluate specific interventions on patient outcomes.

Despite the abovementioned limitations, this study might open a new insight into the existing literature by emphasizing the prognostic importance of hepatic fibrosis risk and hepatic biochemical markers in ICU patients undergoing PEG. By demonstrating the utility of the FIB-4 score and related parameters, our findings provide a foundation for future research to refine risk stratification and develop targeted interventions.

5. Conclusion

This study identifies FIB-4 score, GGT, LDH, and albumin as valuable prognostic mortality indicators in ICU patients undergoing PEG. These findings underscore the potential role of hepatic biochemical parameters in guiding clinical decision-making and provide evidence for the necessity of comprehensive risk assessment in this high-risk population. By integrating these findings into routine practice, clinicians can improve outcomes and facilitate future critical care nutrition and hepatology advancements. However, these findings should be verified by randomized controlled studies conducted with larger patient populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.D. and S.A.; methodology, G.A. and E.K.; software, A.M., K.İ., and S.A.; validation, S.A., E.K., and K.İ.; formal analysis, A.M., S.A., and G.A.; research, K.İ., S.A., and E.K.; resources, A.C.D., G.A., and A.M.; data curation, E.K., S.A., K.İ., and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and S.A.; writing—review and editing, K.İ., E.K., and G.A.; visualization, S.A.; supervision, G.A.; and project administration, A.C.D. and G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures specified in the study protocol are part of routine care, and ethical approval has been obtained for this study. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set by institutional and national research committees, the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Since this study is a retrospective study, informed consent was not obtained.

Data Availability Statement

The data reported in the study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request. Due to confidentiality, the data are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the healthcare professionals in the Gastroenterology Unit at Giresun Education and Research Hospital for their dedicated work and efforts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PEG |

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy |

| GGT |

Gamma glutamyl transferase |

| LDH |

Lactate dehydrogenase |

| ALT |

Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST |

Aspartate aminotransferase |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| FIB-4 |

Fibrosis-4 |

| ICU |

Intensive care unit |

| MASLD |

Steatotic liver disease associated with metabolic dysfunction |

References

- Roche, V. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Clinical care of PEG tubes in older adults. Geriatrics 2003, 58, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rahnemai-Azar, A.A.; Rahnemaiazar, A.A.; Naghshizadian, R.; Kurtz, A.; Farkas, D.T. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: indications, technique, complications and management. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 7739–7751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Kim, T.G.; Cho, K.B.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, J.W.; Jeon, J.W.; Lim, S.G.; Kim, C.G.; Park, H.J.; Kim, T.J.; et al. A Multicenter Survey of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy in 2019 at Korean Medical Institutions. Gut Liver 2024, 18, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrag, S.P.; Sharma, R.; Jaik, N.; Schrag, S.P.; Sharma, R.; Jaik, N.P.; Seamon, M.J.; Lukaszczyk, J.J.; Martin, N.D.; Hoey, B.A.; et al. Complications related to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. A comprehensive clinical review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2007, 16, 407–418. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Xu, H.; Gao, P. Fibrosis Index Based on 4 Factors (FIB-4) Predicts Liver Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Patients. Med Sci Monit 2019, 25, 7243–7250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Stepanova, M.; Felix, S.; Jeffers, T.; Younossi, E.; Goodman, Z.; Racila, A.; Lam, B.P.; Henry, L. The combination of the enhanced liver fibrosis and FIB-4 scores to determine significant fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2023, 57, 1417–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholankeril, G.; Kramer, J.R.; Chu, J.; Yu, X.; Balakrishnan, M.; Li, L.; El-Serag, H.B.; Kanwal, F. Longitudinal changes in fibrosis markers are associated with risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2023, 78, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.H.; Kim, I.Y.; Jang, G.S.; Song, S.H.; Seong, E.Y.; Lee, D.W.; Lee, S.B.; Kim, H.J. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors of mortality in liver cirrhosis patients on continuous renal replacement therapy in two tertiary hospitals in Korea. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2021, 40, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 4. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, S59–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, T.Y.; Liang, P.C.; Jun, D.W.; Jung, J.H.; Toyoda, H.; Wang, C.W.; Yuen, M.F.; Cheung, K.S.; Yasuda, S.; Kim, S.E.; et al. Pretreatment gamma-glutamyl transferase predicts mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis B treated with nucleotide/nucleoside analogs. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2024, 40, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Xia, Y.H.; Zhang, X.H.; Cai, X.X.; Pan, J.Y.; Dong, Y.H. FIB-4 index is associated with mortality in critically ill patients with alcohol use disorder: Analysis from the MIMIC-IV database. Addict Biol 2024, 29, e13361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, C.H.; Huang, W.M.; Yu, W.C.; Cheng, H.M.; Chang, H.C.; Hsu, P.F.; Chiang, C.E.; Chen, C.H.; Sung, S.H. The fibrosis-4 score is associated with long-term mortality in different phenotypes of acute heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest 2022, 52, 13856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinella, M.E.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Caldwell, S.; Barb, D.; Kleiner, D.E.; Loomba, R. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1797–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaby, D.; Young, A.; O’Toole, P.; Smith, G.; Sanders, D.S. The provision of a percutaneously placed enteral tube feeding service. Gut 2010, 59, 1592–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.O.; Moon, H.S.; Kim, T.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kang, S.H.; Sung, J.K.; Jeong, H.Y. Nutritional Impact of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy: A Retrospective Single-center Study. Korean J Gastroenterol 2022, 79, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Liu, M.Y.; Liu, T.H.; Kuo, C.Y.; Hung, K.C.; Tsai, Y.W.; Lai, C.C.; Hsu, W.H.; Chuang, M.H.; Huang, P.Y.l.; et al. Clinical efficacy of enteral nutrition feeding modalities in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Clin Nutr 2023, 77, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poynard, T.; Ngo, Y.; Perazzo, H.; Munteanu, M.; Lebray, P.; Moussalli, J.; Thabut, D.; Benhamou, Y.; Ratziu, V. Prognostic value of liver fibrosis biomarkers: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011, 7, 445–454. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Xu, H.; Gao, P. Fibrosis Index Based on 4 Factors (FIB-4) Predicts Liver Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Patients. Med Sci Monit 2019, 25, 7243–7250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lau, H.C.; Yu, J. Pharmacological treatment for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and related disorders: Current and emerging therapeutic options. Pharmacol Rev. 2025, 77, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Pouri, A.; Ghojazadeh, M.; Estakhri, R.; Somi, M. Non-invasive serum fibrosis markers: A study in chronic hepatitis. Bioimpacts 2015, 5, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motola, D.L.; Caravan, P.; Chung, R.T.; Fuchs, B.C. Noninvasive Biomarkers of Liver Fibrosis: Clinical Applications and Future Directions. Curr Pathobiol Rep 2014, 2, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Kim, S.U.; Ahn, S.H. Non-invasive prediction of forthcoming cirrhosis-related complications. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 2613–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tujios, S.; Stravitz, R.T.; Lee, W.M. Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2022. Semin Liver Dis 2022, 42, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fix, O.K.; Liou, I.; Karvellas, C.J.; et al. Development and Pilot of a Checklist for Management of Acute Liver Failure in the Intensive Care Unit. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0155500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).