1. Introduction

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) remains a cornerstone in managing obstructive jaundice, a complex condition that poses significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Jaundice, with its multifactorial etiologies ranging from malignant cholangiocarcinoma to benign biliary strictures, underscores the pivotal role of precision in diagnosis and treatment [

1,

2]. Historically, PTBD evolved from percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) to become an essential component of interventional radiology, thus allowing interventionists to offer both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. With its ability to provide direct access to the biliary system, PTBD is often employed when endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is unsuccessful or contraindicated due to altered anatomy such as postsurgical biliodigestive anastomoses, complex difficult-to-cross or hilar biliary strictures [

3,

4]. The indications for PTBD span a wide range, from malignant obstructions due to cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic cancer, ampullary malignancies and metastatic disease, to non-malignant conditions such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, iatrogenic strictures and biliary atresia [

5]. Advances in radiological imaging, including computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), have significantly refined the diagnosis and staging of biliary disease, allowing for tailored PTBD procedures based on individual patient anatomy and disease state [

6,

7]. In particular, MRCP has proven useful in delineating biliary anatomy without radiation exposure, complementing PTBD’s capabilities [

8]. Both fluoroscopy-guided and ultrasound-guided percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (F-PTBD and US-PTBD, respectively) procedures are available, with each technique presenting unique benefits and drawbacks. F-PTBD, the conventional approach, boasts a well-defined and standardised protocol. However, it is not without its risks, with a reported complication rate of approximately 10.2%, aligning with broader literature [

9]. These complications can encompass bleeding, pancreatitis, bile leaks, and infections, underscoring the inherent challenges of traversing the intricate biliary anatomy [

10,

11,

12]. The advent of US-PTBD has introduced the potential for reduced complication rates, particularly in terms of hepatic capsule puncture frequency and reduced radiation exposure, as measured by Dose Area Product (DAP) [

13,

14,

15]. This reduction aligns with growing efforts to mitigate radiation risks, especially given cumulative exposure concerns for both patients and healthcare providers [

16]. However, current literature provides limited evidence on the direct comparison between ultrasound-guided and fluoroscopy-guided PTBD, particularly regarding their safety profiles and cumulative radiation exposure to patients and operators, underscoring the need for further investigation to guide clinical decision-making.

This retrospective analysis directly compares US-PTBD and F-PTBD in patients suffering from obstructive jaundice due to malignancies, focusing on a detailed assessment of complication rates and radiation exposure, aiming to provide further insights into the comparative risks and benefits of these techniques and refine patient selection strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study is a retrospective observational single-center analysis of data collected from patients who underwent PTBD to manage obstructive jaundice from January 2018 to December 2024. The inclusion criteria, met by all patients, were as follows: I) diagnosis of obstructive jaundice due to malignancies; II) failed or unfeasible ERCP (Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography); III) evaluation by a multidisciplinary team consisting of oncologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, endoscopists, and interventional radiologists.

The exclusion criteria were: I) multiple metastases that prevent the placement of biliary drainage through healthy parenchyma; II) abundant ascitic effusion; III) compatible preprocedural coagulation testing, according to Society of Interventional Radiology consensus guidelines [

17].

The investigation was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed written informed consent before undergoing percutaneous treatment. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Protocol No. 209/ June 27, 2024 – Comitato Etico Territoriale Regione Calabria, Italy).

2.2. Treatment

In all cases, a preliminary abdominal CT or MRI scan was performed to plan the treatment. PTBD was performed in dedicated angiographic suites by experienced interventionists [

18]. The patient’s laboratory panel, including liver enzymes and coagulation tests, was preliminarily assessed in accordance with the Society of Interventional Radiology consensus guidelines to minimize the risk of bleeding as much as possible [

17]. Percutaneous puncture was performed using the

“Neff Percutaneous Access Set

” kit (Cook Medical) for both methods.

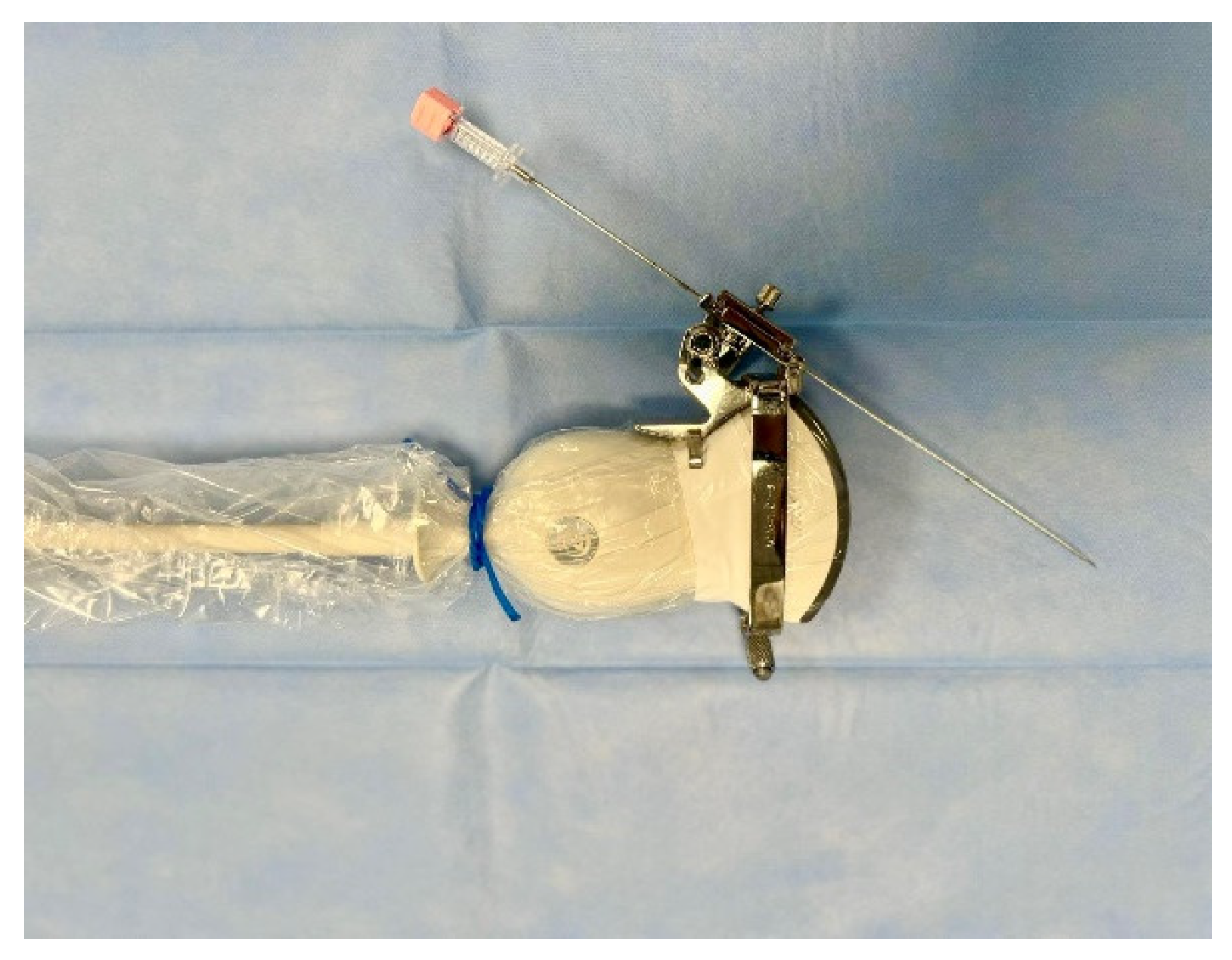

Before every intervention, the patient was induced into deep sedation by an anesthesiologist and, subsequently, a peripheral bile duct was punctured using the fluoroscopy or the ultrasound as guidance. The US-guided puncture was performed with a sterile 22G Chiba needle mounted laterally to the ultrasound probe within a needle guidance system, as shown in the figure (

Figure 1).

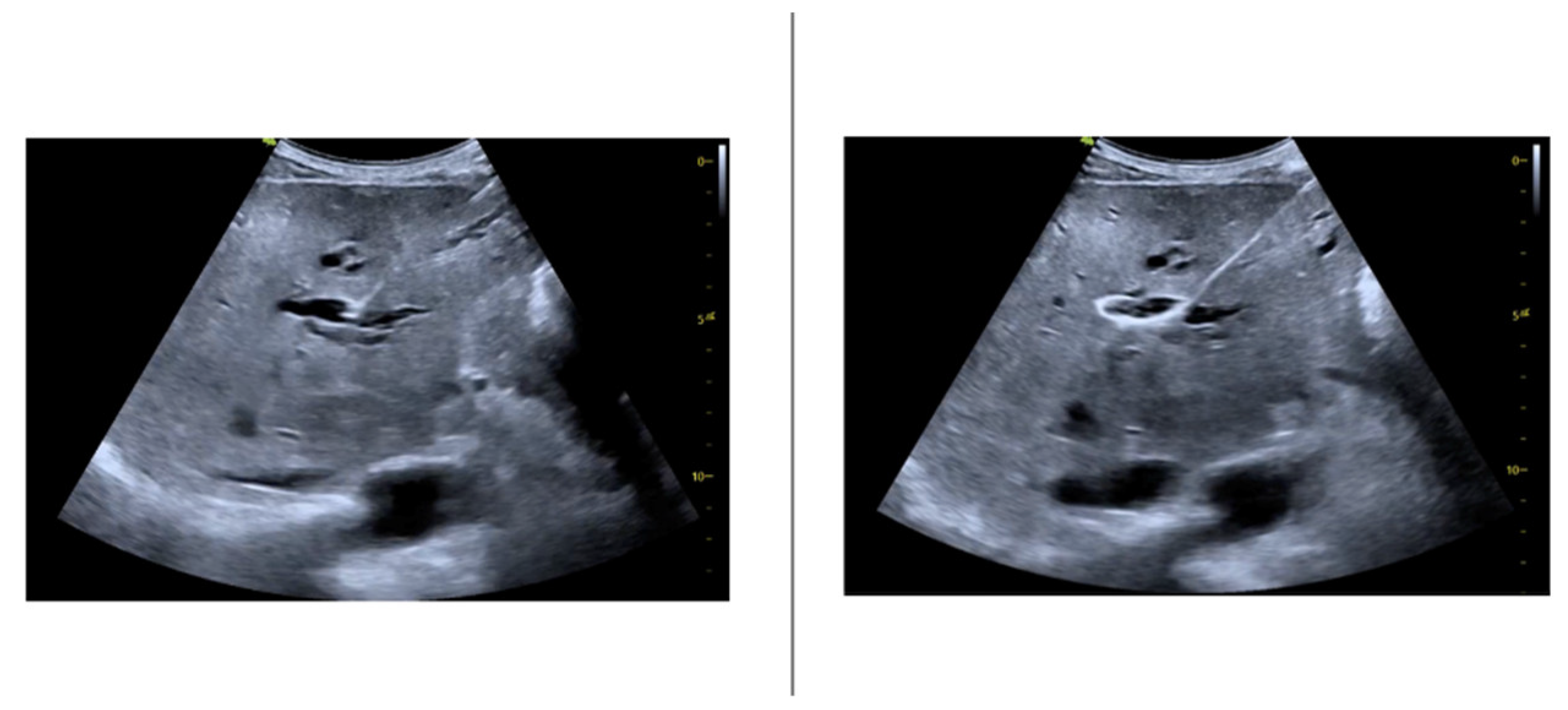

The ultrasound guidance has made possible the direct visualization of the ductal dilation degree (

Figure 2).

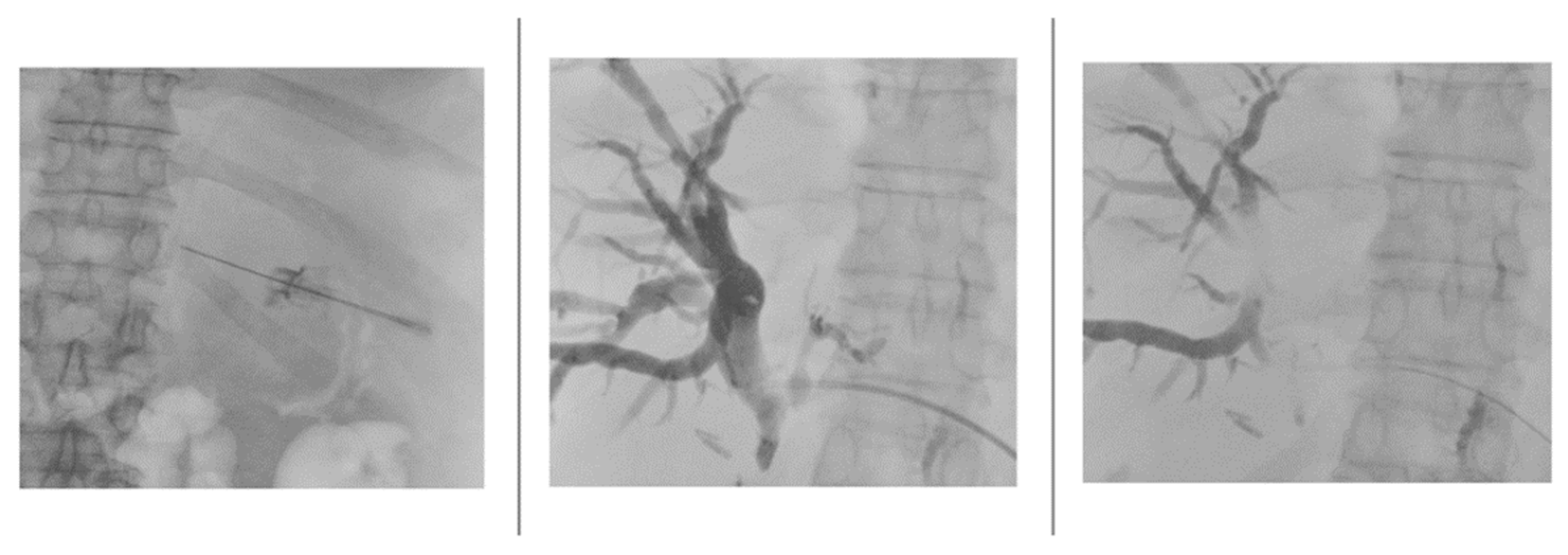

Once the lumen of the bile duct was penetrated and the needle stylet removed, the needle was disconnected from the needle guidance system to stably inject an iodinated contrast agent (Xenetix 250, Guerbet) mixed in a 1:1 ratio with saline to opacify the biliary tree under fluoroscopy guidance (

Figure 3).

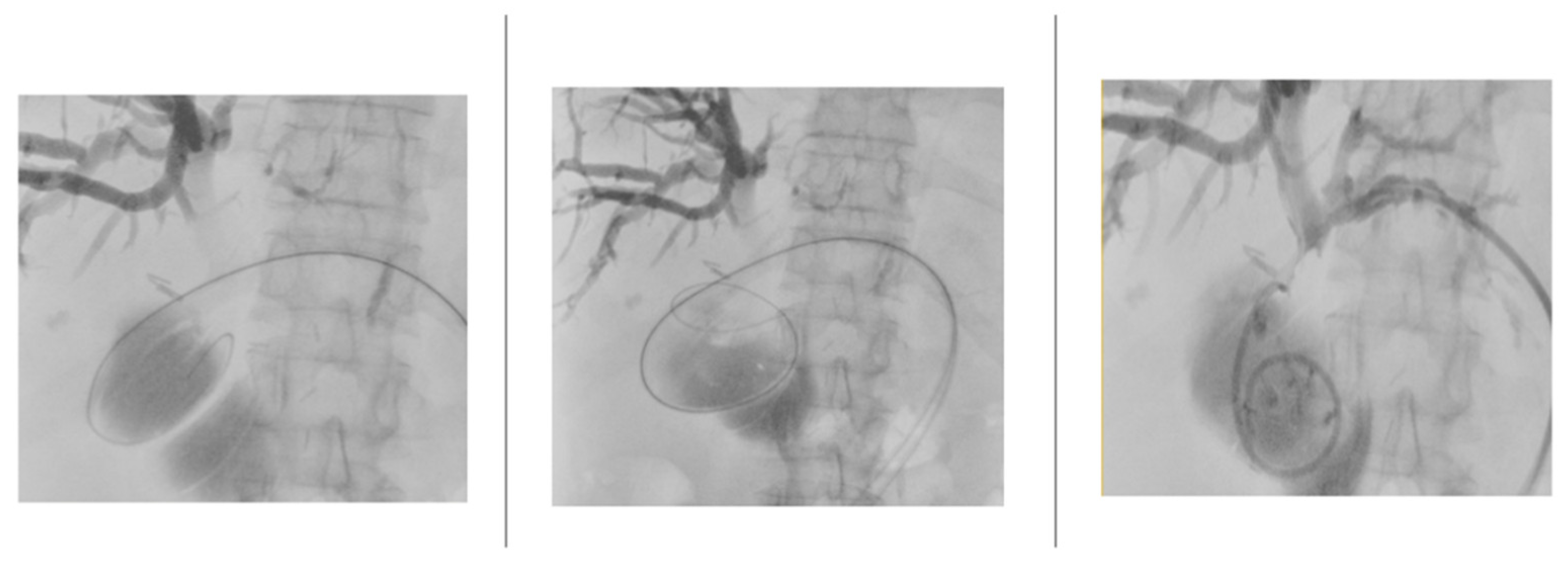

After fluoroscopic visualization of the biliary system, a .018” Cope Mandril Nitinol guidewire with platinum tip (Cook Medical) was inserted through the Chiba needle, followed by replacement with an introducer equipped on a tri-axial system to stabilize the access. Subsequently, the .018” guidewire was replaced by a standard-type 150 cm angled hydrophilic guidewire (Radifocus, Terumo) to cross the stenosis up to the duodenum. This guidewire was replaced by a .035” 145 cm Amplatz-type extra stiff guidewire, over which an 8/10/12 Fr internal-external biliary drainage catheter was positioned (

Figure 4).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

For categorical variables, absolute and relative percentage frequencies are shown [

19]. Continuous data are depicted as mean ± standard deviation [

20]. Statistical differences were assessed using an unpaired Student’s t-test for continuous normally distributed data, the Chi-squared/Fisher’s exact test for categorical data, and the Mann–Whitney test for continuous data that were not normally distributed, as appropriate [

21,

22].

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

During the study period (from January 2018 to December 2024), 133 patients (83 males, 50 females; mean age 69 years) underwent PTBD, for a total of 163 procedures, including 118 F-PTBD and 45 US-PTBD. Both groups were homogeneous in terms of age, gender, and health status. The most common causes of biliary obstruction due to malignancies were metastases (n=87; 53%), cholangiocarcinoma (n=42; 26%), and pancreatic cancer (n=34; 21%).

3.2. Procedure Data

Table 1 demonstrates significant differences between F-PTBD and US-PTBD. F-PTBD procedures were more frequently performed on the right side (91.5% vs. 31%, p < 0.001). F-PTBD procedures exhibited significantly higher dose-area product (DAP) (6.2 ± 1.5 Gycm² in F-PTBD versus 4.1 ± 1.9 Gycm² in US-PTBD; p < 0.001), procedure time (56.6 ± 6 minutes in F-PTBD versus 42 ± 7 minutes in US-PTBD; p < 0.001) and fluoroscopy time (17.4 ± 2.8 minutes in F-PTBD versus 13 ± 4.1 minutes in US-PTBD; p < 0.001), despite similar technical success rates (82.2% in F-PTBD versus 91.1% in US-PTBD; p=0.158). In 3 patients, access was switched from right to left and in 2 patients from left to right. The main reasons for US-PTBD failure were the inability to pass the guidewire into the biliary system due to a non-anatomically favorable needle position. Interestingly, a trend toward a higher complication rate in F-PTBD has been recorded, despite a statistically non-significant difference. In the US-PTBD group, only minor complications occurred. In the F-PTBD group, there were 4 cases of major bleeding (namely, a reduction in hemoglobin of at least 3 g/dL [

23]) and 8 cases of post-procedural cholangitis. The number of percutaneous punctures of the Glisson’s capsule was higher in the F-PTBD group (p=0.489).

3.3. Right Access Vs Left Access

Table 2 compares right-sided and left-sided PTBD access. While technical success rates were similar (85.2% right vs. 82.9% left, p=0.721), right-sided access was predominantly fluoroscopy-guided, leading to significantly higher radiation exposure (mean DAP 4.6 ± 3 Gycm² vs. 6 ± 1.1 Gycm², p<0.001), longer procedure times (55.4 ± 5.9 min vs. 44 ± 11.2 min, p<0.001), and longer fluoroscopy times (17 ± 2.2 min vs. 13.8 ± 5.9 min, p<0.001) compared to left-sided access. The complication rate did not differ significantly between the two approaches (p=0.268).

Table 3 and

Table 4 demonstrate that for both right-sided and left-sided PTBD, fluoroscopy-guided procedures (F-PTBD) exhibited significantly higher radiation exposure, longer procedure times, and longer fluoroscopy times compared to ultrasound-guided procedures (US-PTBD). Technical success rate was higher in the US-PTBD group only for left-sided access. Complication rates did not differ significantly between the two guidance methods, regardless of the access side.

4. Discussion

The medical innovations of recent years have undoubtedly expanded treatment options for patients with obstructive jaundice, yet they have not rendered percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) obsolete in clinical practice [

24]. PTBD continues to serve as a vital alternative to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) when ERCP is unsuccessful or infeasible, maintaining its utility particularly among patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy, such as biliodigestive anastomoses following major surgery [

25,

26,

27]. The present study provides a comprehensive analysis of ultrasound-guided and fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD), focusing on complication rates, procedural time, and radiation exposure. Our findings emphasize the advantages of ultrasound guidance, particularly in reducing radiation exposure and procedural time, with a comparable technical success rate to fluoroscopy. These insights are especially valuable given the scarcity of direct comparative studies on US-PTBD and F-PTBD.

Our study identified a trend toward a higher complication rate in the F-PTBD group (10.2%) compared to the US-PTBD group (6.7%), albeit without statistical significance (p = 0.489). A type II error shouldn’t be excluded, given the limited sample size of our population [

28]. Notably, major complications, including post-procedural cholangitis and significant bleeding, occurred only in the F-PTBD cohort. This observation aligns with findings from Kozlov et al. [

29], who reported a 17.6% complication rate in F-PTBD compared to 5.9% in US-PTBD. Additionally, Giurazza et al. (2019) highlighted the safety of US-PTBD, where minor complications were the predominant adverse events [

30]. Similarly, no difference regarding the overall interventional complication rate (10.6% vs. 9.1%) was observed by Nennstiel et al., but major complications were only encountered in F-PTBDs [

31]. The lower number of Glisson capsule punctures in US-PTBD compared to F-PTBD (1.23 ± 0.21 vs. 1.81 ± 0.19, p = 0.043) supports the hypothesis that real-time vascular and biliary anatomy visualization with ultrasound reduces procedure-related trauma. The significant absence of major bleeding events in the US-PTBD group underscores its safety profile, particularly in patients with coagulopathy or high-risk anatomy, a critical advantage over fluoroscopy-guided techniques. A systematic review of the literature also showed that US-PTBD has lower median rates of severe early complications (0% versus 8%) and procedural death (0% versus 1%) than F-PTBD [

32]. Conversely, in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, the US group didn’t show an improved bleeding rate in PTBD [

33]. Finally, future multicenter studies with larger populations may better demonstrate a possible advantage of the US over fluoroscopy in terms of overall complication and major complication rates.

US-PTBD demonstrated markedly shorter procedural and fluoroscopy times than F-PTBD, with an average procedural time of 42 ± 7 minutes versus 56.6 ± 6 minutes (p < 0.001). In terms of radiation exposure, US-PTBD offers a significant advantage, with a mean dose-area product (DAP) of 4.1 ± 1.9 Gy·cm² compared to 6.2 ± 1.5 Gy·cm² for F-PTBD (p < 0.001). Our findings are consistent with those observed by Park et al. on 50 PTBD procedures with US guidance (mean total DAP=5.2 ± 3.8 Gycm²) [

34]. A study by Schmitz et al. reported a similar radiation exposure [

35]. This reduction has critical implications for patient safety, particularly in repeated procedures, and for healthcare providers routinely exposed to ionizing radiation [

36]. Real-time ultrasound guidance enhances procedural accuracy, facilitating precise needle placement, thus minimizing procedural time and radiation exposure, which is especially advantageous in anatomically complex cases.

The technical success rates for US-PTBD (91.1%) and F-PTBD (82.2%) in our study did not differ significantly (p = 0.158). Interestingly, US-PTBD demonstrated a higher technical success rate in left-sided access (93.1% vs. 58.3%, p = 0.007), suggesting that ultrasound guidance may be particularly advantageous in anatomically complex cases. These findings are consistent with Nennstiel et al. [

31], who reported a similar overall technical success rate of 85-90% for both methods, albeit with some variability depending on the access side. Wagner et al. observed that US-PTBD was technically successful in 94% of attempts with a mean of 2.2 needle passes [

32].

While our findings highlight the potential benefits of US-PTBD, certain limitations warrant consideration. This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective design introduces potential selection biases, particularly in access route and guidance modality, which were determined by operator preference. Second, the relatively small sample size of US-PTBD procedures, particularly for right-sided access, may limit the generalizability of our findings. Third, long-term outcomes, such as patient survival, were not evaluated, precluding a comprehensive assessment of clinical efficacy. Finally, operator expertise with ultrasound-guided procedures may have influenced the outcomes, as proficiency in this technique varies significantly among interventional radiologists. Addressing these limitations through multicenter studies involving a larger, diverse patient population could offer a more comprehensive validation of observed trends. Moreover, standardized protocols across different facilities would be beneficial in mitigating variability and ensuring consistency in outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the advantages of US-PTBD over F-PTBD in terms of reduced radiation exposure, shorter procedural times, and lower complication rates, particularly for left-sided access. While technical success rates were comparable, the observed benefits of ultrasound guidance advocate for its broader adoption in clinical practice. Future prospective studies with larger cohorts and long-term follow-up are warranted to further validate these findings and assess their impact on patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G and D.L.; methodology, M.G.; software, M.G..; validation, M.G., R.M., C.B., G.C., N.D.R., C.F., F.M., D.L.; formal analysis, C.B.; investigation, M.G.; resources, D.L; data curation, D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G., R.M., C.B., G.C., N.D.R., C.F., F.M., D.L.; writing—review and editing, R.M. and G.C.; visualization, M.G., R.M., C.B., G.C., N.D.R., C.F., F.M., D.L.; supervision, D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Protocol No. 209/ June 27, 2024 – Comitato Etico Territoriale Regione Calabria).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PTBD |

Percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage |

| F-PTBD |

Fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage |

| US-PTBD |

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage |

| PTC |

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography |

| ERCP |

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

References

- Shlansky-Goldberg, R.; Weintraub, J. Cholangiography. Semin Roentgenol 1997, 32, 150–160. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-L.; Wu, S.-H.; Hsu, S.-H.; Liou, B.-Y.; Chen, H.-L.; Chang, M.-H. Jaundice Revisited: Recent Advances in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Inherited Cholestatic Liver Diseases. J Biomed Sci 2018, 25, 75. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.; Samant, H. Jaundice. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Dumonceau, J.-M.; Tringali, A.; Blero, D.; Devière, J.; Laugiers, R.; Heresbach, D.; Costamagna, G.; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Biliary Stenting: Indications, Choice of Stents and Results: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy 2012, 44, 277–298. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Yelamanchi, R. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: A Review of Recent Paradigms and Advances in Epidemiology, Clinical Diagnosis and Management. World J Gastroenterol 2021, 27, 3158–3181. [CrossRef]

- Bratu, A.M.; Cristian, D.A.; Sălcianu, I.A.; Zaharia, C.; Iana, G.; Popa, B.V.; Ştefănescu, V. Semiological Characters and Morphopathological-Radiological Correlations in Duodenal Malignancy. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2015, 56, 1017–1025.

- Semelka, R.C.; Kelekis, N.L.; John, G.; Ascher, S.M.; Burdeny, D.; Siegelman, E.S. Ampullary Carcinoma: Demonstration by Current MR Techniques. J Magn Reson Imaging 1997, 7, 153–156. [CrossRef]

- Arrivé, L.; Hodoul, M.; Arbache, A.; Slavikova-Boucher, L.; Menu, Y.; El Mouhadi, S. Magnetic Resonance Cholangiography: Current and Future Perspectives. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2015, 39, 659–664. [CrossRef]

- Ring, E.J.; Oleaga, J.A.; Freiman, D.B.; Husted, J.W.; Lunderquist, A. Therapeutic Applications of Catheter Cholangiography. Radiology 1978, 128, 333–338. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, Y.; Lu, X. Should Preoperative Biliary Drainage Be Routinely Performed for Obstructive Jaundice with Resectable Tumor? Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2013, 2, 266–271. [CrossRef]

- Sewnath, M.E.; Karsten, T.M.; Prins, M.H.; Rauws, E.J.A.; Obertop, H.; Gouma, D.J. A Meta-Analysis on the Efficacy of Preoperative Biliary Drainage for Tumors Causing Obstructive Jaundice. Ann Surg 2002, 236, 17–27. [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Gaa, J.; Rosca, B.; Born, P.; Neu, B.; Schmid, R.M.; Prinz, C. Complications of Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage in Patients with Dilated and Nondilated Intrahepatic Bile Ducts. Eur J Radiol 2009, 72, 412–417. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Mayr, C.; Kiesslich, T.; Berr, F.; Friesenbichler, P.; Wolkersdörfer, G.W. Reduced Complication Rates of Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage with Ultrasound Guidance. J Clin Ultrasound 2017, 45, 400–407. [CrossRef]

- Makuuchi, M.; Bandai, Y.; Ito, T.; Watanabe, G.; Wada, T.; Abe, H.; Muroi, T. Ultrasonically Guided Percutaneous Transhepatic Bile Drainage: A Single-Step Procedure without Cholangiography. Radiology 1980, 136, 165–169. [CrossRef]

- Sukigara, M.; Taguchi, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Koshizuka, S.; Koyama, I.; Omoto, R. Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage Guided by Color Doppler Echography. Abdom Imaging 1994, 19, 147–149. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.L.; Vañó, E.; Bartal, G.; Balter, S.; Dixon, R.; Padovani, R.; Schueler, B.; Cardella, J.F.; Baère, T. de Occupational Radiation Protection in Interventional Radiology: A Joint Guideline of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe and the Society of Interventional Radiology. Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology 2009, 33, 230. [CrossRef]

- Patel, I.J.; Rahim, S.; Davidson, J.C.; Hanks, S.E.; Tam, A.L.; Walker, T.G.; Wilkins, L.R.; Sarode, R.; Weinberg, I. Society of Interventional Radiology Consensus Guidelines for the Periprocedural Management of Thrombotic and Bleeding Risk in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Image-Guided Interventions-Part II: Recommendations: Endorsed by the Canadian Association for Interventional Radiology and the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2019, 30, 1168-1184.e1. [CrossRef]

- Ring, E.J.; Oleaga, J.A.; Freiman, D.B.; Husted, J.W.; Lunderquist, A. Therapeutic Applications of Catheter Cholangiography. Radiology 1978, 128, 333–338. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Talarico, M.; Pascale, A.; Pascale, V.; Minici, R.; Boriani, G. Low Levels of Vitamin D and Silent Myocardial Ischemia in Type 2 Diabetes: Clinical Correlations and Prognostic Significance. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 2572. [CrossRef]

- BRACALE, U.M.; Peluso, A.; Panagrosso, M.; Cecere, F.; Del Guercio, L.; Minici, R.; Giannotta, N.; Ielapi, N.; Licastro, N.; Serraino, G.F.; et al. Ankle-Brachial Index Evaluation in Totally Percutaneous Approach vs. Femoral Artery Cutdown for Endovascular Aortic Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Chirurgia (Turin) 2022, 35, 349–354. [CrossRef]

- Minici, R.; Venturini, M.; Fontana, F.; Guzzardi, G.; Pingitore, A.; Piacentino, F.; Serra, R.; Coppola, A.; Santoro, R.; Laganà, D. Efficacy and Safety of Ethylene-Vinyl Alcohol (EVOH) Copolymer-Based Non-Adhesive Liquid Embolic Agents (NALEAs) in Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) of Acute Non-Neurovascular Bleeding: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59, 710. [CrossRef]

- Minici, R.; Ammendola, M.; Talarico, M.; Luposella, M.; Minici, M.; Ciranni, S.; Guzzardi, G.; Laganà, D. Endovascular Recanalization of Chronic Total Occlusions of the Native Superficial Femoral Artery after Failed Femoropopliteal Bypass in Patients with Critical Limb Ischemia. CVIR Endovasc 2021, 4, 68. [CrossRef]

- Minici, R.; Serra, R.; Maglia, C.; Guzzardi, G.; Spinetta, M.; Fontana, F.; Venturini, M.; Laganà, D. Efficacy and Safety of Axiostat® Hemostatic Dressing in Aiding Manual Compression Closure of the Femoral Arterial Access Site in Patients Undergoing Endovascular Treatments: A Preliminary Clinical Experience in Two Centers. J Pers Med 2023, 13, 812. [CrossRef]

- Glenn, F.; Evans, J.A.; Mujahed, Z.; Thorbjarnarson, B. Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiography. Ann Surg 1962, 156, 451–462. [CrossRef]

- Bapaye, A.; Dubale, N.; Aher, A. Comparison of Endosonography-Guided vs. Percutaneous Biliary Stenting When Papilla Is Inaccessible for ERCP. United European Gastroenterol J 2013, 1, 285–293. [CrossRef]

- Artifon, E.L.A.; Aparicio, D.; Paione, J.B.; Lo, S.K.; Bordini, A.; Rabello, C.; Otoch, J.P.; Gupta, K. Biliary Drainage in Patients with Unresectable, Malignant Obstruction Where ERCP Fails: Endoscopic Ultrasonography-Guided Choledochoduodenostomy versus Percutaneous Drainage. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012, 46, 768–774. [CrossRef]

- Sharaiha, R.Z.; Kumta, N.A.; Desai, A.P.; DeFilippis, E.M.; Gabr, M.; Sarkisian, A.M.; Salgado, S.; Millman, J.; Benvenuto, A.; Cohen, M.; et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage versus Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage: Predictors of Successful Outcome in Patients Who Fail Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc 2016, 30, 5500–5505. [CrossRef]

- Columb, M.; Atkinson, M. Statistical Analysis: Sample Size and Power Estimations. BJA Education 2016, 16, 159–161. [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, A.V.; Polikarpov, A.A.; Oleshchuk, N.V.; Tarazov, P.G. [Comparative assessment of percutaneous transhepatic cholangiodrainage under roentgenoscopy and ultrasound guidance]. Vestn Rentgenol Radiol 2002, 30–33.

- Giurazza, F.; Corvino, F.; Contegiacomo, A.; Marra, P.; Lucarelli, N.M.; Calandri, M.; Silvestre, M.; Corvino, A.; Lucatelli, P.; De Cobelli, F.; et al. Safety and Effectiveness of Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage: A Multicenter Experience. J Ultrasound 2019, 22, 437–445. [CrossRef]

- Nennstiel, S.; Treiber, M.; Faber, A.; Haller, B.; von Delius, S.; Schmid, R.M.; Neu, B. Comparison of Ultrasound and Fluoroscopically Guided Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage. Digestive Diseases 2018, 37, 77–86. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Mayr, C.; Kiesslich, T.; Berr, F.; Friesenbichler, P.; Wolkersdörfer, G.W. Reduced Complication Rates of Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage with Ultrasound Guidance. J Clin Ultrasound 2017, 45, 400–407. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-T.; Yen, K.-C.; Liang, P.-C.; Wu, C.-H. Procedure-Related Risk Factors for Bleeding after Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Formos Med Assoc 2022, 121, 1680–1688. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.E.; Nam, I.C.; Baek, H.J.; Ryu, K.H.; Lim, S.G.; Won, J.H.; Kim, D.R. Effectiveness of Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage to Reduce Radiation Exposure: A Single-Center Experience. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0277272. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, D.; Weller, N.; Doll, M.; Weingärtner, S.; Pelaez, N.; Reinmuth, G.; Hetjens, S.; Rudi, J. An Improved Method of Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage Combining Ultrasound-Guided Bile Duct Puncture with Metal Stent Implantation by Fluoroscopic Guidance and Endoscopic Visualization as a One-Step Procedure: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Interventional Radiology ISVIR 2018, 02, 135–143. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.L.; Vañó, E.; Bartal, G.; Balter, S.; Dixon, R.; Padovani, R.; Schueler, B.; Cardella, J.F.; de Baère, T.; Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe; et al. Occupational Radiation Protection in Interventional Radiology: A Joint Guideline of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe and the Society of Interventional Radiology. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010, 21, 607–615. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).