1. Introduction

Indeterminate biliary strictures (IBS) are regarded as such when the standard diagnostic work up turn out to be inconclusive, representing a diagnostic challenge for physicians [

1]. Standard diagnostic work-up includes cross sectional imaging with computer tomography (CT)-scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with brush cytology and/or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine needle aspiration (FNA) or biopsy (FNB).

Despite the application of the above-mentioned techniques, even in combination, biliary strictures can be easily mischaracterized and remain indeterminate in up to 20% of cases; moreover, one out of four surgically resected IBS demonstrate a benign histology [

1,

2].

The limits of standard diagnostic work up can lead to multiple, repeated procedures in order to obtain a diagnosis, which means extended time from clinical presentation to treatment (reducing the probability of a curative resection in patients with malignancy), but also increased risk for procedure-related adverse events (AEs) [

3,

4,

5,

6].

In the last decades several new diagnostic techniques have been developed in order to overcome these limitations; development of single-operator cholangioscopy (SOC) and the evolution to digital cholangioscopy (DSOC) permitted the direct visualization of the biliary mucosa and the evaluation of cholangioscopic features of malignancy, associated with the possibility of tissue acquisition under endoscopic view [

7].

Intraductal ultrasound (IDUS) can obtain real-time, cross-sectional images of ductal and periductal structures using a high-frequency ultrasound probe, inserted directly into the bile duct over a guidewire. Findings consistent with a malignant etiology include asymmetric wall thickening, disruption of layers, enlarged lymph nodes and hypoechoic sessile masses or nodules [

8]; findings associated with benign strictures include normal layering, smooth margins, homogenous and symmetric hyperechoic thickening of the biliary wall with loss of normal layering [

9]. Despite promising data from literature, the utilization of IDUS remains limited to few centers.

Due to the low sensitivity of standard diagnostic, a “one shot” approach may be offered in some referral centers, with a combination of ERCP and ancillary techniques in order to maximize the diagnostic yield and trying to reduce the need for multiple procedures [

10].

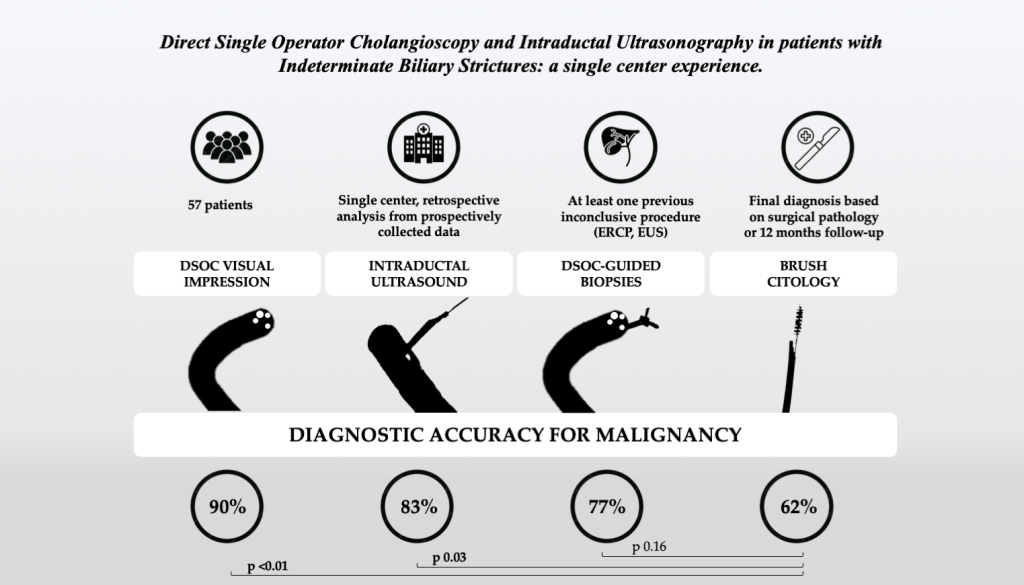

Aim of this study was to evaluate diagnostic performance (sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive and negative predictive values) of DSOC, DSOC-guided biopsy, IDUS and standard brush cytology in patients with IBS.

Secondary aims were the evaluation of the safety profile of the procedure, and the evaluation of the impact of a previous stenting on diagnostic accuracy.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a monocentric, retrospective, observational study on consecutive patients with IBS who underwent cholangioscopy and IDUS at the Endoscopy Unit of AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino (Turin, Italy), from January 2018 to December 2022.

This study included patients with a previous inconclusive diagnostic work up for biliary stricture (with ERCP and brushing cytology and/or EUS ± FNA/FNB); patients were referred from other hospitals, or underwent previous procedures at our Unit.

All demographic, clinical, endoscopic, histologic and follow-up data were collected prospectively in an electronic database.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) patients with IBS undergoing DSOC for IBS between January 2018 and December 2022; (2) patients ≥ 18 years of age.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) indication to DSOC other than IBS; (2) coagulation disorder with a contraindication to invasive endoscopic maneuvers (INR >1.6, platelet count < 40x103/mm3); (3) refusal to give informed consent to the procedure and/or to the study.

All procedures were performed by highly experienced biliopancreatic endoscopists in both EUS and ERCP; endoscopists were not blinded to relevant clinical information before the procedures. ERCP was performed in standard fashion with a TJF-180 duodenoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with Propofol-induced deep sedation and patient in left lateral decubitus; antibiotic prophylaxis was administered to all patient before cholangioscopy (generally beta-lactam or fluoroquinolones) and rectal indomethacin or diclofenac (100 mg) were administered in all patients for post-ERCP pancreatitis prophylaxis, if not contraindicated. Patients stayed at least one night in hospital after procedure and blood tests, including lipases, were performed 6 hour after the procedure and the next morning.

IDUS examination was carried out with the introduction of a 20 MHz wire-guided miniprobe (UM-DP20-25R, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) above the stricture, and then gently passed through the stricture for the evaluation of ultrasonographic images.

Cholangioscope for DSOC (SpyGlass Discover™, Boston scientific, MA,USA) was introduced over a guidewire up to the stricture, for a visual inspection.

DSOC-guided biopsies were performed with dedicated forceps (SpyBite™, Boston Scientific; MA, USA) targeting suspicious areas of the IBS.

Brushing cytology was performed under fluoroscopic view, with a standard brush (Cytomax II Double-lumen Cytology Brush, Cook Medical, NC, USA).

2.1. Definitions

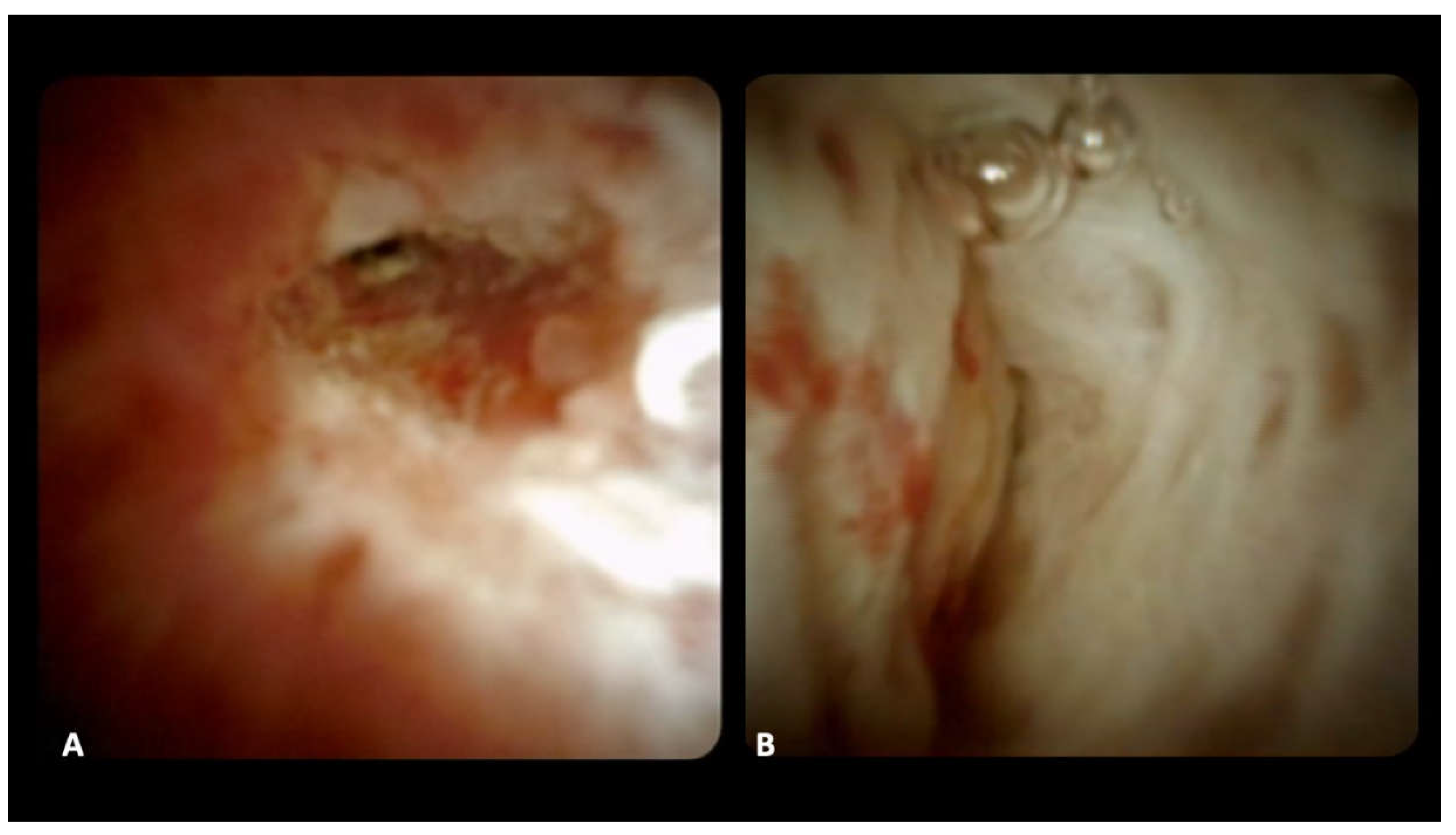

For DSOC-based diagnosis, the presence of the following criteria was evaluated: (1) stricture, (3) mucosal changes, (4) papillary projections, (5) ulceration, (6) mass or nodularity, and (7) vascularization [

11]; the final impression diagnosis of benign or malignant stricture was made during the procedure (

Figure 1).

IDUS-based diagnosis was made on the basis of previous published criteria: asymmetric wall thickening, disruption of layers, enlarged lymph nodes and/or hypoechoic sessile masses or nodules were considered consistent with malignant stricture[

8].

As reference diagnosis of malignancy, surgical specimen (when available), biopsy and/or cytology showing malignant cells were considered; a benign diagnosis required a minimum of 12 months of clinical and radiological follow-up with no masses or evolution seen on imaging, repeated sampling or death.

The length of follow up was calculated as the time between procedure and surgery in patients undergoing surgical resection; for the remaining patients, the time between procedure and death or the last clinical contact was considered.

AEs were investigated in electronic health records, and categorized by the onset (preprocedural, intraprocedural, post-procedural as <14 days and late as ≥ 14 days) and the severity (mild, moderate, severe and fatal) [

12].

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Demographic, clinical, procedural and pathology details were depicted using descriptive statistic, as mean and standard deviation (±SD) for continuous variables, or number and percentage for categorical variables.

Operating characteristics including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and diagnostic accuracy were calculated for each diagnostic technique.

Fisher’s exact test was applied for the comparison of the operating characteristics, Student’s t-test was used for comparison of continuous variables among subgroups.

P value of 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant; statistical analysis was performed with MedCalc Statistical Software version 19.2.6 (MedCalc Software bv, Ostend, Belgium).

The study protocol and consent form were approved by the local Institutional Review Board and the study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

A total of 57 patients were included, mostly male (39 patients, 68.4%) with a mean age of 67.2 ± 10.0 years. The majority of patients had comorbidities (34 patients, 59.6%), particularly cardiovascular diseases (24 patients, 42.1%), chronic liver diseases (7 patients, 12.3%) and pulmonary diseases (6 patients, 10.5%).

Only one patient had a previous diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis, and 11 patients (19.3%) had a history of previous or active tobacco consumption.

All patients had a previous inconclusive diagnostic procedure: 39 patients had previous ERCP (68.4%), with a mean number of previous procedures of 2.0 ± 1.4; 14 patients had a previous attempt of IBS characterization with EUS ± FNA/FNB (24.6%) and 4 patients (7.0%) had a previous attempt with percutaneous ultrasound transhepatic biliary tissue acquisition; 38 patients (66.7%) had a previous biliary sphincterotomy and 30 patients (52.6%) had a biliary stent in place.

Strictures were located along the whole biliary tree; the most common location of IBS in our cohort was the distal common bile duct (26 patients, 45.6%), followed by the common hepatic duct (13 patients, 22.8%), hepatic hilum (12 patients, 21.1%), intrahepatic ducts (5 patients, 8.8%) and the cystic duct (1 patient, 1.7%). Baseline characteristics of patients are reported in Table 1.

DSOC was successfully performed in all patient; 52 patients underwent DSOC-guided tissue acquisition. In 5 patients, DSOC-guided biopsy was not performed (in 2 patients because of the evidence of extra-ductal lesion, in 3 patients for technical failure in bringing the forceps out from the cholangioscope channel); the technical success rate of DSOC-guided biopsy was then 94.5%.

Fifty-two patients (91.2%) underwent IDUS: the passage of the miniprobe through the stricture was not possible in 3 patients, while in the other 2 cases IDUS was temporary unavailable. The technical success rate of IDUS was 94.5%. Lastly, 39 patients underwent also brush cytology; in 3 patient brush cytology was not performed due to the evidence of extra-ductal lesion, in 15 patients because specimen collected by DSOC-guided biopsies were considered sufficient.

Final diagnosis was consistent with malignancy in 35 patients (61.4%), and cholangiocarcinoma was the most common etiology (77.1%), followed by intraductal papillary biliary neoplasm with high grade dysplasia (4 patients, 11.4%), ampullary adenocarcinoma (3 patients, 8.6%) and pancreatic cancer (1 patient, 2.9%). The final diagnosis of malignancy was confirmed by surgical pathology in 22 patients (62.9%), by evidence of malignancy in cytology and/or DSOC-guided biopsies in 9 patients (25.7%) and by clinical and radiological follow up in 4 patients (11.4%).

A benign etiology of IBS was found in 22 patients, confirmed by surgical pathology in one patient and by clinical and radiological follow up in 21 of them. The mean follow-up of patients was 18.2 ± 18.1 months; in patient with a final diagnosis of benign strictures was 24.1 ± 18.6 months, while the mean follow-up of patients with malignant strictures was 14.5 ±17.1 months.

3.1. Diagnostic performance

Diagnostic yields of different techniques are shown in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Diagnostic yield of different techniques.

Table 2.

Diagnostic yield of different techniques.

| Techniques |

Sensitivity

(CI 95%)

|

Specificity

(CI 95%)

|

Accuracy

(CI 95%)

|

NPV

(CI 95%)

|

PPV

(CI 95%)

|

| DSOC visualization |

85.7%

(76.6 – 94.8%) |

95.5%

(90.0 – 100%) |

89.5%

(81.5 – 97.4%) |

80.8%

(70.5 – 91%) |

96.8%

(92.2 – 100%) |

| IDUS |

84.4%

(74.5 – 94.2%) |

80.0%

(69.1 – 90.9%) |

82.7%

(72.4 – 93.0%) |

76.2%

(64.6 – 87.8%) |

87.1%

(78.0 – 96.2%) |

| DSOC targeted biopsy |

63.6%

(51.1 – 76.1%) |

100%

(83.0 – 100%) |

76.9%

(66.0 – 87.9%) |

61.3%

(48.6 – 73.9%) |

100%

(85.0 – 100%) |

| Brush cytology |

51.6%

(38.6 – 64.6%) |

100%

(78 – 100%) |

61.5%

(48.9 – 74.2%) |

34.8%

(22.4 – 47.1%) |

100%

(82 – 100%) |

DSOC showed a sensitivity of 85.7% (CI 95% 76.6 – 94.8%), a specificity of 95.5% (CI 95% 90 – 100%) and an overall diagnostic accuracy of 89.5% (CI 95% 81.5 – 97.4%); NPV was 80.8% (CI 95% 70.5% - 91%) and PPV was 96.8% (CI 95% 92.2.- 100%).

IDUS showed similar characteristics, with a sensitivity of 84.4% (CI 95% 74.5 – 94.2%), a specificity of 80% (CI 95% 69.1 – 90.9%) and an accuracy of 82.7% (CI 95% 72.4 – 93%). NPV and PPV were respectively 76.2% (64.6% - 87.8%) and 87.1% (CI 95% 78 – 96.2%).

DSOC-guided biopsies had lower sensitivity (63.6%, CI 95% 51.1% - 76.1%) and a specificity of 100% (83 – 100%); the diagnostic accuracy of targeted biopsies was 76.9% (CI 95% 66 – 87.9%).

Brush cytology showed a sensitivity of 51.6% (CI 95%38.6 – 64.6%) and a specificity of 100% (CI 95% 68 – 100%). The accuracy of this technique was 61.5% (CI 95% 48.9 – 74.2%).

DSOC visualization and IDUS outperformed cytology in terms of sensitivity (p< 0.01, p= 0.03, p< 0.01 respectively) and accuracy (p< 0.01, p= 0.047, p= 0.03 respectively); NPV was significantly higher for DSOC and IDUS compared to cytology (p< 0.01). Finally, DSOC sensitivity was significantly higher than targeted biopsies (p= 0.05).

Comparison of operating characteristics of each test are reported in

Table 3.

3.2. Secondary Aim: Effect of Previous Stenting

Twenty-nine out 57 patients (50.9%) underwent the procedure with a previous stent in place, removed before starting DSOC, and all but one were plastic stents. Twenty-eight patients (49.1%) did not have stent in place.

The two groups were comparable in terms of age (respectively 66.5 ± 11.0 vs 68.0 vs 9.2, p = 0.58), gender (male were 62.1% and 75% respectively, p = 0.27) and etiology (malignant stricture in 55.2% and 67.9% of cases, p = 0.42).

Presence of a stent did not affect the diagnostic accuracy of DSOC-visualization (89.7% in the stent group, 92.9% in the no-stent group, p >0.99), while the diagnostic accuracy of IDUS in stented patients demonstrated a trend towards a slight decrease (74.1% vs 92%), but the reduction was not statistically significant (p = 0.14).

3.3. Secondary Aim: Safety

Ten patients out of 57 experienced 11 AEs (17.5%); 5 AEs were mild, 5 moderate and 1 fatal. The most common AE was cholangitis (5 cases, 8.8%), followed by acute pancreatitis (4 cases, 7.0%) and one case of aspiration pneumonia; only in one case of cholangitis a new endoscopic intervention was required, with replacement of malfunctioning plastic stent, while the others were managed with medical therapy. In all cases the hospital stay was prolonged for less than 7 days.

A patient with a previous history of coronary artery disease developed a myocardial infarction four days after cholangioscopy, which was judged not related to endoscopic procedure; he underwent to percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and died during the hospitalization. All AEs are reported in Table 4.

4. Discussion

The goal of an accurate diagnosis of IBS is crucial due to the potentially vastly different prognosis based on etiology [

13]. Because of the suboptimal diagnostic accuracy of conventional ERCP-based tissue acquisition, DSOC has emerged as a promising innovation that could have a role in the diagnosis of IBS [

14]. Our results confirm these findings: DSOC showed nearly 90% diagnostic accuracy, significantly higher when compared with brush cytology (61.5%) which is a current standard in many endoscopy units.

The direct visualization of the characteristics of a stricture results in the possibility to recognize endoscopic features of malignancy, such as papillary projections and tortuous vessels, with a specificity comparable with histological specimen but a higher sensitivity.

Interestingly, an optical diagnosis seems to perform better in term of sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy compared to DSOC-guided biopsies. This “paradox” can be partially explained by biological characteristics of cholangiocarcinoma, which is the leading cause of IBS in our cohort: desmoplastic nature of tumors, associated fibrosis and the submucosal spread exhibit by bile duct tumors could particularly lower the yield of superficial sampling method. Lastly, cancers extrinsic to the bile duct such as pancreatic cancers and metastatic tumors are expectedly more difficult to sample from within the duct [

15]. In addition, size and shape of the DSOC-dedicated forceps may be implicated in the lack of sensitivity of targeted biopsy; as previously described [

16,

17], the small specimens collected by the forceps have to be carefully manipulated to avoid loss of material during the standard formalin fixation and paraffin embedding, and new dedicated processing protocols should be individuated in order to maximize the diagnostic yield [

18].

Unlike in EUS-guided tissue acquisition [

19], the procedure is still lacking of a standardized protocol of sampling, and the minimum number of biopsies to optimize the diagnostic performance of the technique has not been defined. However, in a prospective study, Bang and colleagues found that in the absence of on-site cytopathology evaluation, performing 3 biopsies can make the correct diagnosis for the 90% of cases, comparable to the on-site approach [

20]. Indeed, when available, the “rapid on-site evaluation of touch imprint cytology”(ROSE-TIC) may improve the diagnostic yield of DSOC-guided biopsies [

21].

Our results are in line with literature, where the visual accuracy during DSOC has been reported to range between 80 and 97%.7,22 Initially, some concerns were raised on the poor interobserver agreement for the correct classification of some cholangioscopic features [

23], based more on impressions provided by the investigators rather than reference to standardized, validated definitions [

24,

25].

The evolution of cholangioscopy to a digital platform with improved imaging quality [

26] and the introduction of different classification systems (the Monaco classification and the Robles-Medranda Criteria) [

27,

28] helped to overcome these limitations, as demonstrated recently by Kahaleh and colleagues [

29].

The present study showed similar diagnostic yield for IDUS, with sensitivity and specificity above 80%, significantly higher compared to cytology; IDUS showed also a trend for a better sensitivity compared to targeted biopsies (84.4% vs 63.6%, p = 0.09). This technique has not proliferated, and nowadays very few endoscopists performing ERCP are trained in IDUS. In our experience, it is a fast and reliable tool in the evaluation of strictures, residual lithiasis and compression of the bile ducts from extra-ductal lesions, which can be hard to assess by fluoroscopy; moreover, it permits an evaluation of longitudinal extension of cholangiocarcinoma, and provides an accurate assessment of hepatic artery and portal vein infiltration, which is crucial for surgical candidates [

30,

31]. Not least, compared to cholangioscopy, IDUS is safer and less expensive. In fact, miniprobes are reusable and can last up to 50 examinations when properly handled, which made IDUS particularly beneficial in limited-resource settings [

32].

An interesting finding of our study is the impact of biliary stenting on diagnostic accuracy. Diagnostic accuracy of DSOC with or without a stent in place is comparable (respectively 89.7 vs 92.9), while diagnostic accuracy of IDUS in patient with stent in place was slightly decreased (74.1% of accuracy in the stent group, compared to 92% in patient without biliary stenting).

The difference, although not significant, show how prior endoscopic manipulation of biliary stricture alters the biliary epithelium, likely resulting in inflammation and architectural distortion which can negatively impact accuracy.

In addition to the diagnostic yield, we focused on safety of procedure; AEs rate of our study was 17.5%, which is comprised in the wide range (from 1.7% to 25.4%) published in previous studies [

26,

33,

34]; this variation depends to a certain extent to different definitions of AEs in previous published studies, with higher rates in papers with more detailed definitions. Despite the administration of antibiotic prophylaxis in all patients, the most common AE was cholangitis (8.8%), probably due to the intermittent irrigation to obtain adequate visualization of the biliary mucosa, with a retrograde bacterial flow in the biliary tree [

35]. Currently, European guidelines consider cholangioscopy as a procedure at high risk for post-ERCP cholangitis and suggest antibiotic prophylaxis when performing it [

36]. With this in mind, more studies, including randomized controlled trials, are necessary to precisely define possible measure to prevent this complication, maybe investigating a possible role of a longer course of antibiotic therapy after cholangioscopy, instead of only procedural antibiotic dose, in reducing cholangitis rate.

Acute pancreatitis was the second most common AE in our study , occurring in 7% of patients. This rate seems greater when compared to the 2-4% risk of acute pancreatitis following standard ERCP [

37].

A possible pathogenic mechanism can be found in the mechanical irritation and subsequent swelling of the papilla due to the passage of the cholangioscope, as previously described for other rigid catheter such as IDUS miniprobes [

38]. Interestingly, the association of the two techniques (DSOC and IDUS) in our cohort did not lead to an increased risk when compared to previous published studies on DSOC [

26,

34]. Furthermore, all cases of post-procedural acute pancreatitis observed were mild and moderate, managed with medical therapy and with limited extension of the hospital stay. Since post-procedural lipase levels were routinely determined in all patients, even mild cases of pancreatitis were less likely to be missed.

Before drawing definite conclusions, we need to address some limitations to our study. First of all, endoscopists were not blinded to the previous imaging, laboratory results and clinical history when they were evaluating biliary strictures, hence IDUS and DSOC visual evaluation could have been biased; however, our patients were referred due to still indeterminate biliary strictures despite previously performed diagnostics, and this is more representative of the clinical practice. Secondly, this is a monocentric experience, with procedures performed by expert endoscopists in a high volume referral hospital; although European guidelines recommend that IBS should be assessed and managed in tertiary referral centers [

39,

40], it is unclear whether similar results would be reproduced if less-experienced endoscopists performed these procedures. Lastly, the number of patients is still relatively small; this explains the wide confidence intervals in our diagnostic operating characteristics and may limit our results given that one false negative or false positive examination can significantly change our findings.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, DSOC visualization and IDUS demonstrated an optimal diagnostic yield in the differentiation of indeterminate biliary strictures; the high sensitivity of these techniques compared to standard sampling methods helped to correctly diagnose 90% of IBS in our cohort. A multimodal approach, with the possibility to perform different diagnostics in the same session with a tailored procedure, can help endoscopists in the management of this challenging disease. DSOC showed the highest diagnostic accuracy, and should be the method of choice in the evaluation of IBS; when technically unfeasible due to the position or angulation of the stricture, the use of IDUS can come to the rescue, providing a reliable results in more than 80% of the patients and reducing the need of multiple procedures, shortening the time to reach an accurate diagnosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MS and CGD; methodology, MS , MB and CGD; software, MS; formal analysis, MS, MG; investigation, MS, MAG, MTS, ED, SC, SD, CC, AC, FM, RCS, SG; data curation, MS and MG.; writing—original draft preparation, MS; writing—review and editing, GMS, MB, CGD; supervision, CGD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino (ref. 142.984, prot. 0011607).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, MS, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

C.G.D. is a scientific consultant for Boston Scientific; other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xie C, Aloreidi K, Patel B, et al. Indeterminate biliary strictures: a simplified approach. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12(2):189-199. [CrossRef]

- Gerhards MF, Vos P, van Gulik TM, Rauws EAJ, Bosma A, Gouma DJ. Incidence of benign lesions in patients resected for suspicious hilar obstruction. Br J Surg. 2002;88(1):48-51. [CrossRef]

- Dalal A, Gandhi C, Patil G, Kamat N, Vora S, Maydeo A. Safety and efficacy of different techniques in difficult biliary cannulation at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Hosp Pract. 1995;50(1):61-67. [CrossRef]

- Junior CC de C, Bernardo WM, Franzini TP, et al. Comparison between endoscopic sphincterotomy vs endoscopic sphincterotomy associated with balloon dilation for removal of bile duct stones: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;10(8):130-144. [CrossRef]

- Goyal H, Sachdeva S, Sherazi SAA, et al. Early prediction of post-ERCP pancreatitis by post-procedure amylase and lipase levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2022;10(07):E952-E970. [CrossRef]

- Cirocchi R, Kelly MD, Griffiths EA, et al. A systematic review of the management and outcome of ERCP related duodenal perforations using a standardized classification system. Surg. 2017;15(6):379-387. [CrossRef]

- Almadi MA, Itoi T, Moon JH, et al. Using single-operator cholangioscopy for endoscopic evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures: results from a large multinational registry. Endoscopy. 2020;52(7):574-582. [CrossRef]

- Sun B, Hu B. The role of intraductal ultrasonography in pancreatobiliary diseases. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5(5):291. [CrossRef]

- Farrell RJ, Agarwal B, Brandwein SL, Underhill J, Chuttani R, Pleskow DK. Intraductal US is a useful adjunct to ERCP for distinguishing malignant from benign biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(5):a128918. [CrossRef]

- De Angelis CG, Dall’Amico E, Staiano MT, et al. The Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography and Endoscopic Ultrasound Connection: Unity Is Strength, or the Endoscopic Ultrasonography Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Concept. Diagnostics. 2023;13(20):3265. [CrossRef]

- Manta R, Frazzoni M, Conigliaro R, et al. SpyGlass® single-operator peroral cholangioscopy in the evaluation of indeterminate biliary lesions: a single-center, prospective, cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(5):1569-1572. [CrossRef]

- Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(3):446-454. [CrossRef]

- Novikov A, Kowalski TE, Loren DE. Practical Management of Indeterminate Biliary Strictures. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2019;29(2):205-214. [CrossRef]

- Angsuwatcharakon P, Kulpatcharapong S, Moon JH, et al. Consensus guidelines on the role of cholangioscopy to diagnose indeterminate biliary stricture. Hpb. 2022;24(1):17-29. [CrossRef]

- Korc P, Sherman S. ERCP tissue sampling. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(4):557-571. [CrossRef]

- Fugazza A, Gabbiadini R, Tringali A, et al. Digital single-operator cholangioscopy in diagnostic and therapeutic bilio-pancreatic diseases: A prospective, multicenter study. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54(9):1243-1249. [CrossRef]

- Onoyama T, Hamamoto W, Sakamoto Y, et al. Peroral cholangioscopy-guided forceps biopsy versus fluoroscopy-guided forceps biopsy for extrahepatic biliary lesions. JGH Open. 2020;4(6):1119-1127. [CrossRef]

- Baars JE, Keegan M, Bonnichsen MH, et al. The ideal technique for processing SpyBite tissue specimens: a prospective, single-blinded, pilot-study of histology and cytology techniques. Endosc Int Open. 2019;07(10):E1241-E1247. [CrossRef]

- Polkowski M, Jenssen C, Kaye P, et al. Technical aspects of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Guideline – March 2017. Endoscopy. 2017;49(10):989-1006. [CrossRef]

- Bang JY, Navaneethan U, Hasan M, Sutton B, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Optimizing Outcomes of Single-Operator Cholangioscopy–Guided Biopsies Based on a Randomized Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(2):441-448.e1. [CrossRef]

- Varadarajulu S, Bang JY, Hasan MK, Navaneethan U, Hawes R, Hebert-Magee S. Improving the diagnostic yield of single-operator cholangioscopy-guided biopsy of indeterminate biliary strictures: ROSE to the rescue? (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(4):681-687. [CrossRef]

- Parsa N, Khashab MA. The Role of Peroral Cholangioscopy in Evaluating Indeterminate Biliary Strictures. Clin Endosc. 2019;52(6):556-564. [CrossRef]

- Sethi A, Widmer J, Shah NL, et al. Interobserver agreement for evaluation of imaging with single operator choledochoscopy: What are we looking at? Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46(6):518-522. [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa T, Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y, Sugiyama H, Miyazaki M, Yokosuka O. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of peroral video-cholangioscopic visual findings and cholangioscopy-guided forceps biopsy findings for indeterminate biliary lesions: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77(2):219-226. [CrossRef]

- Ramchandani M, Reddy DN, Gupta R, et al. Role of single-operator peroral cholangioscopy in the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary lesions: a single-center, prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(3):511-519. [CrossRef]

- Lenze F, Bokemeyer A, Gross D, Nowacki T, Bettenworth D, Ullerich H. Safety, diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic efficacy of digital single-operator cholangioscopy. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(6):902-909. [CrossRef]

- Robles-Medranda C, Valero M, Soria-Alcivar M, et al. Reliability and accuracy of a novel classification system using peroral cholangioscopy for the diagnosis of bile duct lesions. Endoscopy. 2018;50(11):1059-1070. [CrossRef]

- Sethi A, Tyberg A, Slivka A, et al. Digital Single-operator Cholangioscopy (DSOC) Improves Interobserver Agreement (IOA) and Accuracy for Evaluation of Indeterminate Biliary Strictures: The Monaco Classification. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56(2):1-4. [CrossRef]

- Kahaleh M, Raijman I, Gaidhane M, et al. Digital Cholangioscopic Interpretation: When North Meets the South. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(4):1345-1351. [CrossRef]

- Venezia L, Rizza S, Pablo CV, De Angelis CG. Intraductal ultrasound (IDUS) for second-level evaluation of biliary and ampullary stenosis: experience from the Turin center. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50(2):e214-e215. [CrossRef]

- Kim DC, Moon JH, Choi HJ, et al. Usefulness of Intraductal Ultrasonography in Icteric Patients with Highly Suspected Choledocholithiasis Showing Normal Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(8):1902-1908. [CrossRef]

- Fusaroli P, Caletti G. Intraductal Ultrasound for High-Risk Patients: When Will the Last Be First? Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(8):1676-1678. [CrossRef]

- Almadi MA, Itoi T, Moon JH, et al. Using single-operator cholangioscopy for endoscopic evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures: results from a large multinational registry. Endoscopy. 2020;52(07):574-582. [CrossRef]

- Laleman W, Verraes K, Van Steenbergen W, et al. Usefulness of the single-operator cholangioscopy system SpyGlass in biliary disease: a single-center prospective cohort study and aggregated review. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(5):2223-2232. [CrossRef]

- Yodice M, Choma J, Tadros M. The Expansion of Cholangioscopy: Established and Investigational Uses of SpyGlass in Biliary and Pancreatic Disorders. Diagnostics. 2020;10(3):132. [CrossRef]

- Dumonceau JM, Kapral C, Aabakken L, et al. ERCP-related adverse events: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2020;52(2):127-149. [CrossRef]

- Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G, et al. Incidence Rates of Post-ERCP Complications: A Systematic Survey of Prospective Studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(8):1781-1788. [CrossRef]

- Meister T, Heinzow H, Heinecke A, Hoehr R, Domschke W, Domagk D. Post-ERCP pancreatitis in 2364 ERCP procedures: Is intraductal ultrasonography another risk factor? Endoscopy. 2011;43(4):331-336. [CrossRef]

- Tringali A, Lemmers A, Meves V, et al. Intraductal biliopancreatic imaging: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) technology review. Endoscopy. 2015;47(8):739-753. [CrossRef]

- Pouw RE, Barret M, Biermann K, et al. Endoscopic tissue sampling - Part 1: Upper gastrointestinal and hepatopancreatobiliary tractsEuropean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2021;53(11):1174-1188. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).