1. Introduction

Air pollutants, particularly atmospheric particulate matter, are a global concern due to their harmful effects on human health, as they can cause serious diseases (e.g., Goudie, 2014; Manisalidis et al., 2020; Chaparro et al., 2024a). Heavy metals are among the most toxic components of atmospheric dust (Zhang et al., 2022). In Latin America, emissions from mobile sources are a major contributor to air pollution. These emissions frequently contain potentially toxic elements (PTE) such as Pb, Cd, Cu, As, Ni, Zn, and Cr (Adamiec et al., 2016). In recent years, studies examining the environmental and public health impacts of total suspended particles (TSP) and particulate matter (PM) have largely focused on downtown areas of major cities or metropolitan zones with intensive industrial activity and heavy vehicular traffic (Fang et al., 2018; Ali et al., 2019; Cori et al., 2020; Yin., 2025).

However, this particulate matter is also present in urban parks—key spaces for recreation and essential urban ecosystem services. These green areas expose vulnerable populations to air pollutants derived from nearby traffic. Urban parks are often located along major city roads to improve accessibility and serve a larger number of people. Consequently, the heavy traffic surrounding these parks increases user exposure to vehicle-related air pollutants, including PM which raises the risk of adverse health effects (Tran et al., 2021), or even short-duration events with a high rate of PM emission into the atmosphere, such as recreational activities involving fireworks or even forest fires (Rodríguez-Trejo et al, 2024).

Urban parks are typically chosen for activities aimed at promoting health, leisure, and physical exercise, with users often expecting cleaner air. Nevertheless, air quality within a park can vary considerably depending on multiple factors, such as the amount and type of vegetation, nearby pollution sources, wind patterns, and climatic conditions. Trees within these parks can mitigate air pollution through various mechanisms, including the direct interception of airborne particles on their leaf surfaces, thereby improving ambient air quality. Vegetation is widely recognized as a natural filter for pollutants and plays a role in reducing PM levels (Chen et al., 2016). However, the effectiveness of vegetation in capturing atmospheric dust varies significantly by plant type and species (Liu et al., 2013). Numerous studies have demonstrated the capacity of vegetation to act as a physical barrier, altering pollutant dispersion patterns and contributing to localized air purification effects (Wang et al., 2024).

One species that has received attention for its PM accumulation capabilities is Tillandsia recurvata. This epiphytic bromeliad has been identified as a powerful bioaccumulator of atmospheric contaminants (Chaparro et al., 2015; Castañeda-Miranda et al., 2016; Kumar, 2024). Due to its specialized trichomes, T. recurvata absorbs a significant portion of its nutrients and moisture directly from the atmosphere, making it particularly sensitive to airborne pollutants and thus a suitable bioindicator for assessing air quality in urban environments (Sawidis et al., 2012).

However, evaluating air quality in urban parks presents challenges due to the heterogeneity of conditions across the landscape. High-resolution spatial assessments require simultaneous measurements at multiple locations. In Latin American cities, such efforts are often limited by equipment costs and the risk of vandalism. Traditional high-precision particle monitors are expensive and scarce, with many cities possessing only one to five monitoring units, as is the case in our study area. Consequently, alternative low-cost approaches such as magnetic monitoring have gained traction for urban air pollution studies (Hofman et al., 2017). Magnetic monitoring provides an efficient, cost-effective method for assessing air quality with high spatial resolution (Marie et al., 2018; Mejia Echeverry et al., 2018; Chaparro et al., 2024b), and has shown strong correlation with chemical analyses in previous studies.

In this study, we conduct magnetic monitoring of air quality in an urban park using native Tillandsia recurvata as biomonitors. We also present a quantitative analysis of tree species within the park, and report the results of magnetic characterization of the particles accumulated on the biomonitors after one year of exposure. Additionally, we provide spatial distribution and concentration maps of airborne particle pollutants across three distinct sections of the urban park in our study area. Our research highlights the dual application of T. recurvata as a bioaccumulator and magnetic monitoring as a viable tool for assessing air quality in urban green spaces.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study Area

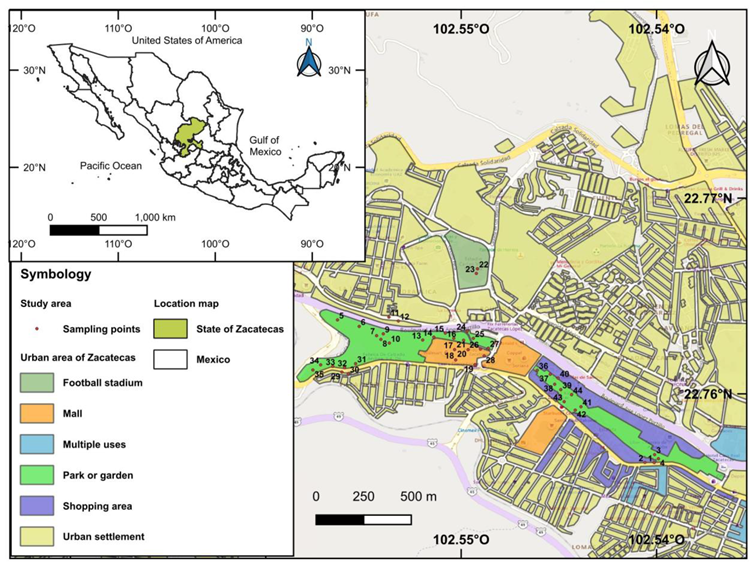

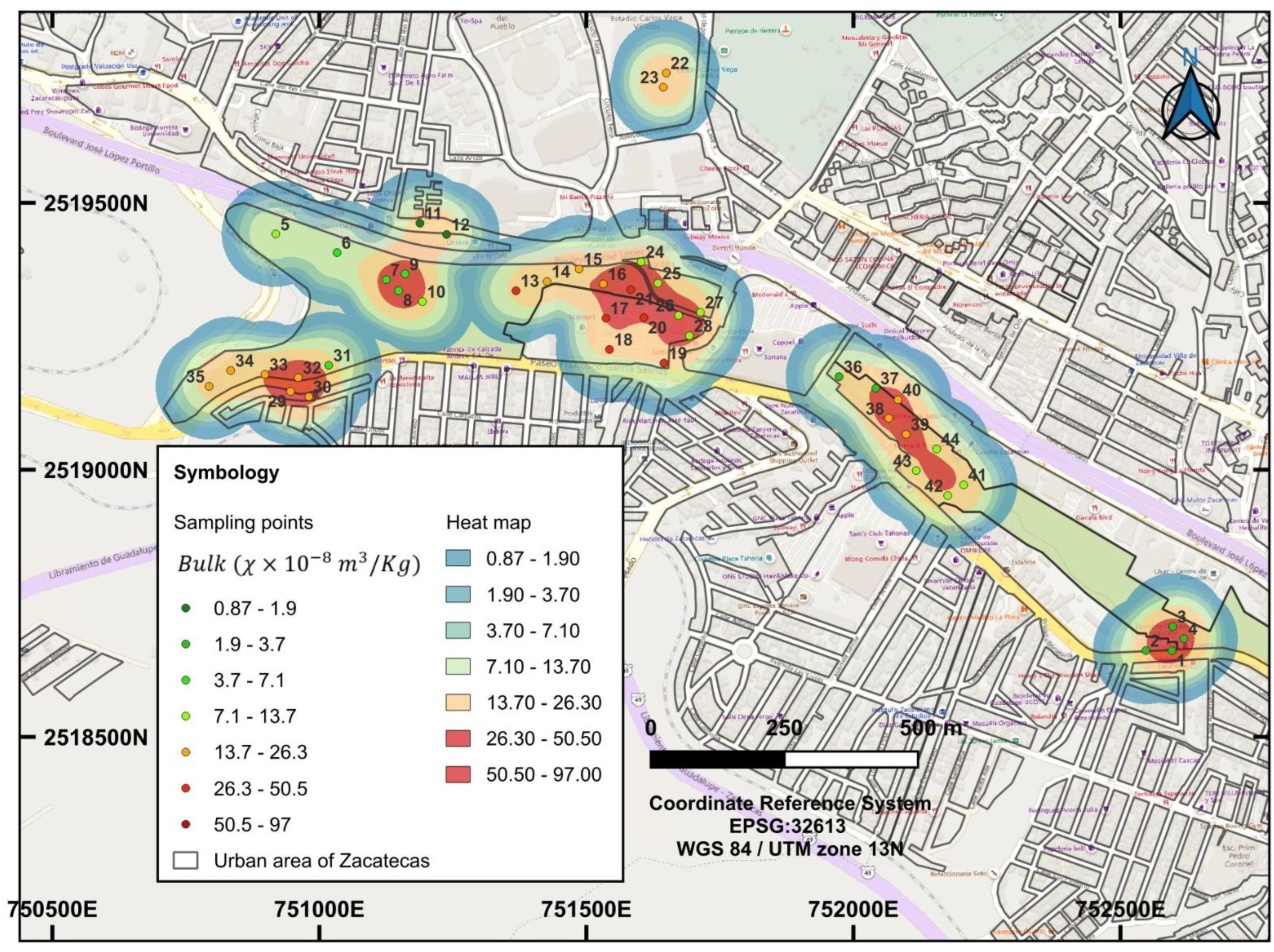

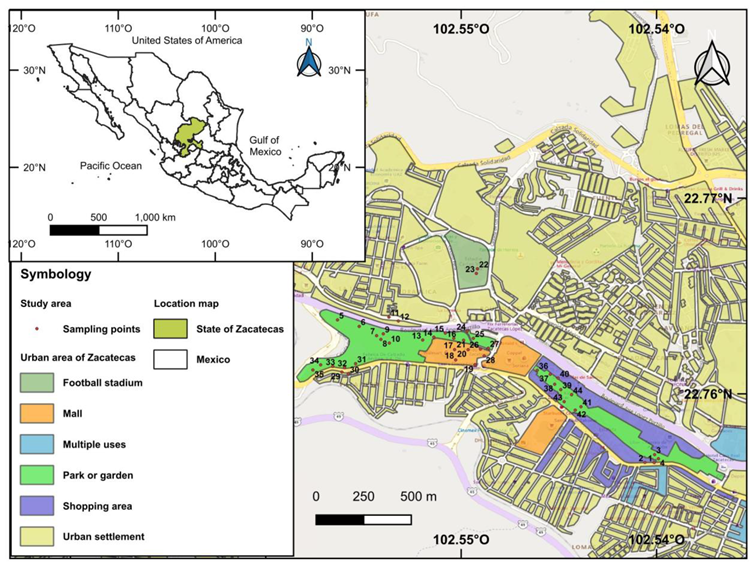

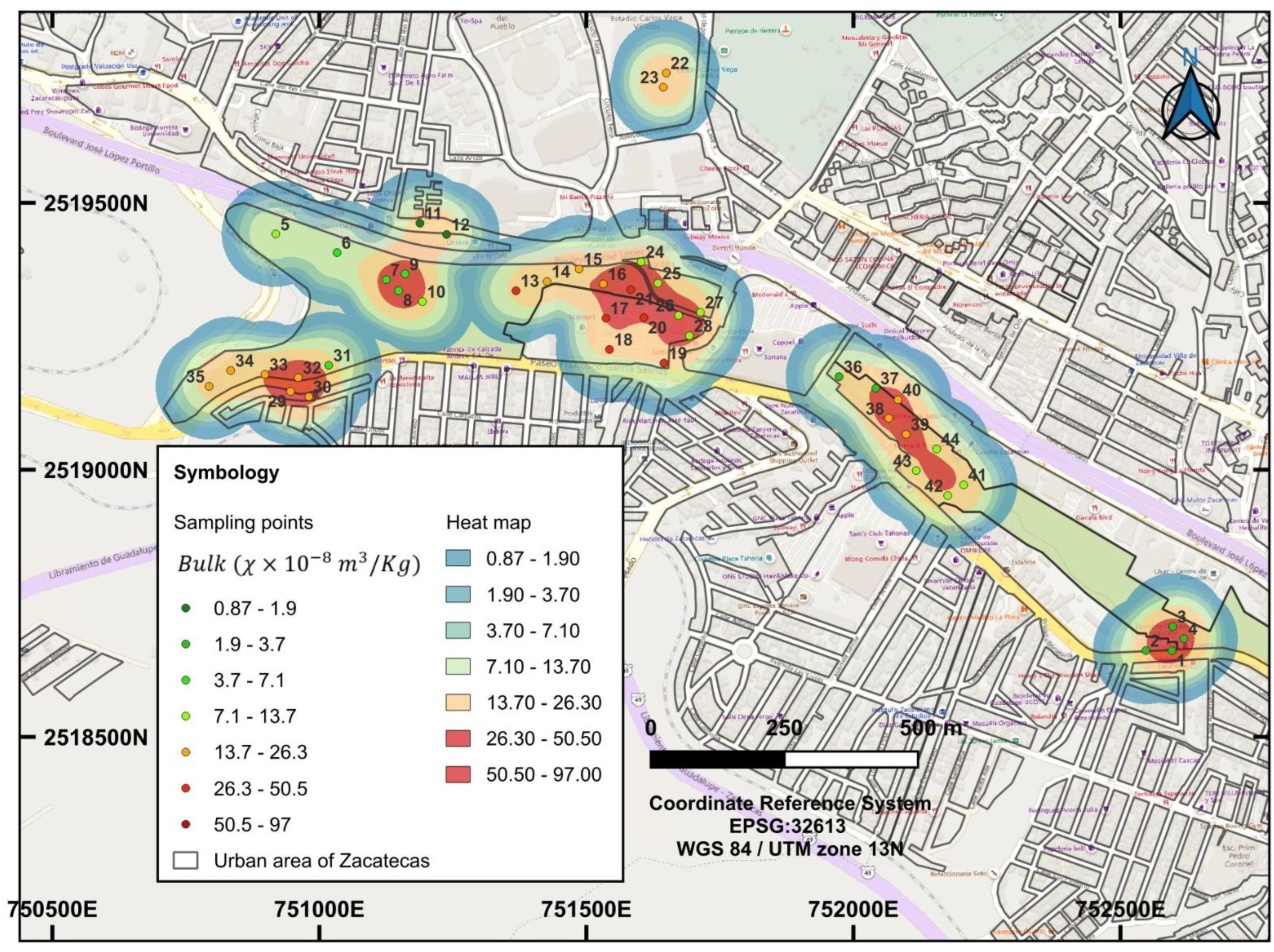

The study site is an urban park located in the metropolitan area of Zacatecas-Guadalupe, in the state of Zacatecas, Mexico (Figure 1). This park consists of three main sections intersected by two of the busiest roadways in the region: Adolfo López Mateos Blvd and José López Portillo Blvd, both forming part of Federal Highway 45 (also known as the Pan-American Highway). This road corridor carries a high volume of vehicular traffic, representing a significant source of air pollution in the area. The city of Zacatecas lies in north-central Mexico and exhibits a semi-arid temperate climate (BSh(w) in the Köppen classification), characterized by dry winters and moderate summer rainfall. The average annual temperature is 17 °C, with average highs reaching up to 30 °C in May and lows near 3 °C in January. Annual precipitation is approximately 510 mm, concentrated between June and September (INEGI, 2020; CONAGUA, 2023).

Water supply in this region relies heavily on the exploitation of aquifers, as surface water sources are scarce and insufficient to meet urban demand. Zacatecas suffers from severe aquifer overexploitation, particularly in the Guadalupe-Bañuelos and Calera systems, both classified as critical by the National Water Commission (CONAGUA, 2023). The state's meteorological monitoring infrastructure includes 38 automatic weather stations operated by SMN-CONAGUA, equipped with sensors to measure temperature, relative humidity, precipitation, wind speed and direction, solar radiation, and soil moisture. These stations generate data every 15 minutes. The nearest stations to the study site are Guadalupe (Academic Unit of Biology) and Zacatecas (Academic Unit of Agronomy), which provide key environmental data for atmospheric biomonitoring strategies.

In the Zacatecas-Guadalupe urban sprawl, two main traffic flows move in directions opposite to Federal Highway 45. The first is driven by commercial and service activities toward the city center; the second corresponds to bureaucratic and academic commuting, mainly toward the western sector. Both converge along Adolfo López Mateos Blvd, causing traffic saturation in the area where the park under study is located (González, 2022). Although Zacatecas experiences slower urban growth compared to other major Mexican cities such as Monterrey and Santiago de Querétaro, it has recorded a population increase of 8.27% over the past decade (INEGI, 2020). The main sources of air pollution in the region include vehicular traffic, brick kilns, forest fires, and mining tailings—typical of a city with a strong mining heritage and ongoing urban development.

2.2. Sampling

One individual of Tillandsia recurvata was collected from each of the 44 sites distributed across the three sections of the urban park. (Fig. 1) Several of these locations were subject to higher pollutant loads and exhibited variations in physical structure and tree density . For the sampling design, the park’s total length of 10 km was initially divided into 50 segments, corresponding to the predetermined number of sampling sites for detailed analysis. Consequently, a sampling interval of 200 meters was established. However, T. recurvata was not found at eight locations, resulting in a final total of 42 sites, along with two additional points (sites 22 and 23), for a complete set of 44 sampling points. Within each 200-meter segment, a sampling point was selected based on the availability of Tillandsia individuals.

The two additional samples (sites 22 and 23) were collected near the local football stadium; an adjacent urban area frequently used for recreational and athletic activities. These sites were included to enable a comparative analysis between the main park and neighboring urban zones with similar pedestrian density.

The dominant vegetation in the park is Schinus molle (Peruvian pepper tree), and accordingly, all T. recurvata samples were collected from this species. The selected S. molle individuals were mature trees, with heights ranging from 15 to 20 meters. Although not native to Mexico, S. molle has been widely naturalized and is commonly found in arid and semi-arid regions of the country, including the study area. Due to its drought tolerance and rapid growth, it has been extensively planted and has become a key component of both urban and rural landscapes.

T. recurvata samples were collected at heights above 1.5 meters to minimize the influence of resuspended urban soil particles. To avoid cross-contamination between sites, plastic scrapers and disposable gloves were used throughout the sampling process. Since this species consists of leaves with varying ages, individuals of similar estimated age were selected by choosing specimens approximately 10–12 cm in diameter, in order to reduce variability in exposure times.

Sampling was conducted in late October 2023, during what was considered an atypical climatic year for Mexico and various other regions worldwide, marked by unusually dry conditions. Although the rainy season typically spans from June to September, virtually no precipitation was recorded during that period. Instead, rainfall events began in October, coinciding with what is generally classified as the dry season. It is important to note that T. recurvata does not self-clean completely during rainfall events (Buitrago Posada et al., 2023). During precipitation, the plant closes its trichomes to avoid water loss and continues to accumulate atmospheric particles. Therefore, a single sampling campaign was conducted one week after the last precipitation event, following the methodological protocol established by Castañeda-Miranda et al. (2020). All material was placed in paper bags and stored at room temperature in the laboratory until subsequent magnetic and complementary analyses were carried out.

2.3. Magnetic Measurements

Biological specimens were enclosed in non-magnetic plastic capsules (8 cm3) and subsequently weighed, with masses reaching up to 3.2 g, prior to magnetic characterization. All magnetic analyses were performed at the Laboratory of Paleomagnetism and Rock Magnetism, located at the Geosciences Center of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

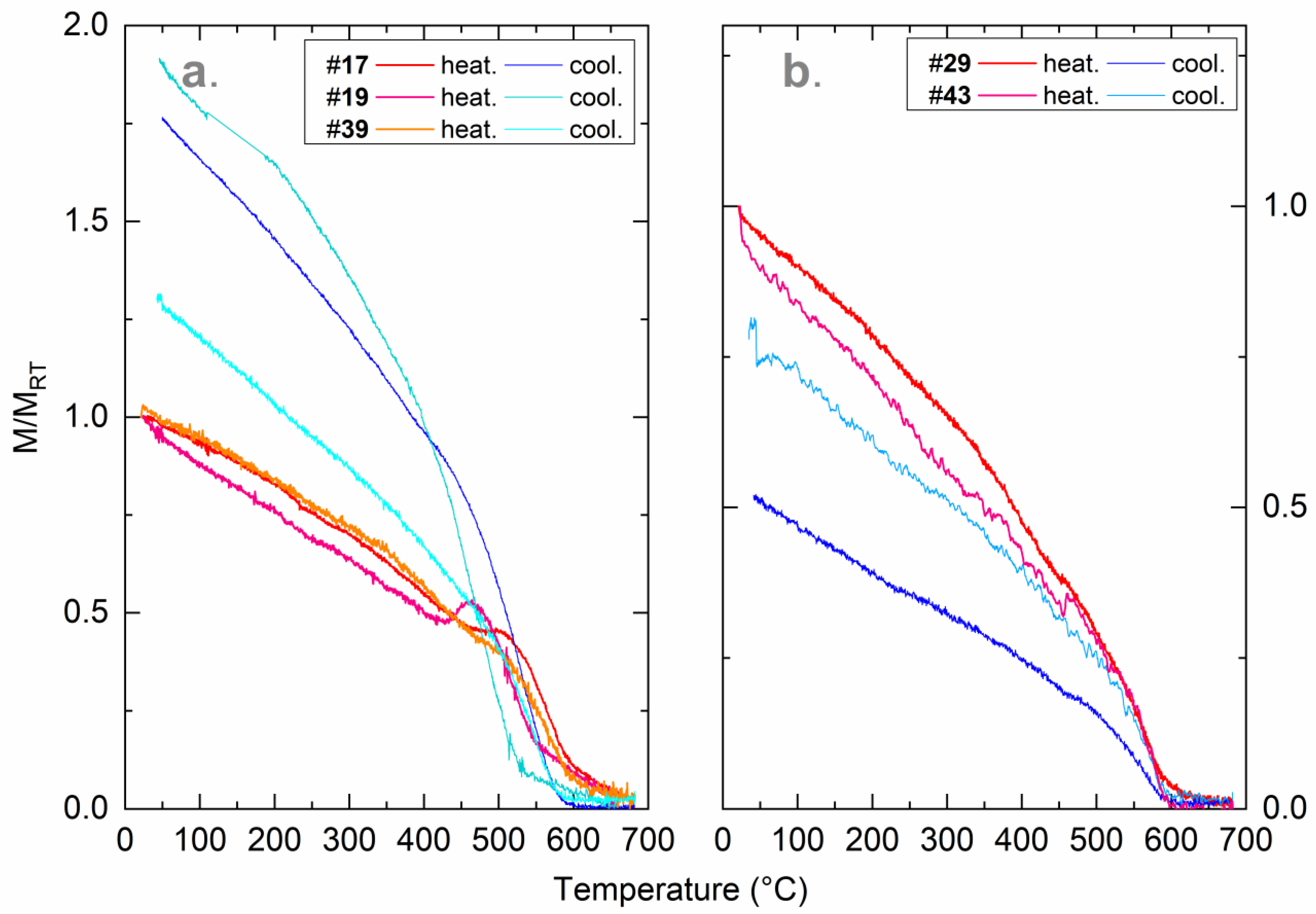

Complementary analyses were carried out on selected specimens (100–220 mg) using a custom-designed horizontal magnetic balance to generate thermomagnetic curves. An inducing magnetic field of 0.5 T was applied, and both heating and cooling procedures were performed in air at a controlled ramp rate of 30 °C·min−1. Samples were heated up to approximately 700 °C and then cooled to room temperature. The relative induced magnetization (M/MRT) was recorded as a function of temperature (T), and the resulting M/MRT–T curves are reported due to their significance in identifying thermal magnetic transitions. Low-field magnetic susceptibility was measured in both volumetric and mass-specific forms using a KLY-3 Kappabridge susceptometer (AGICO).

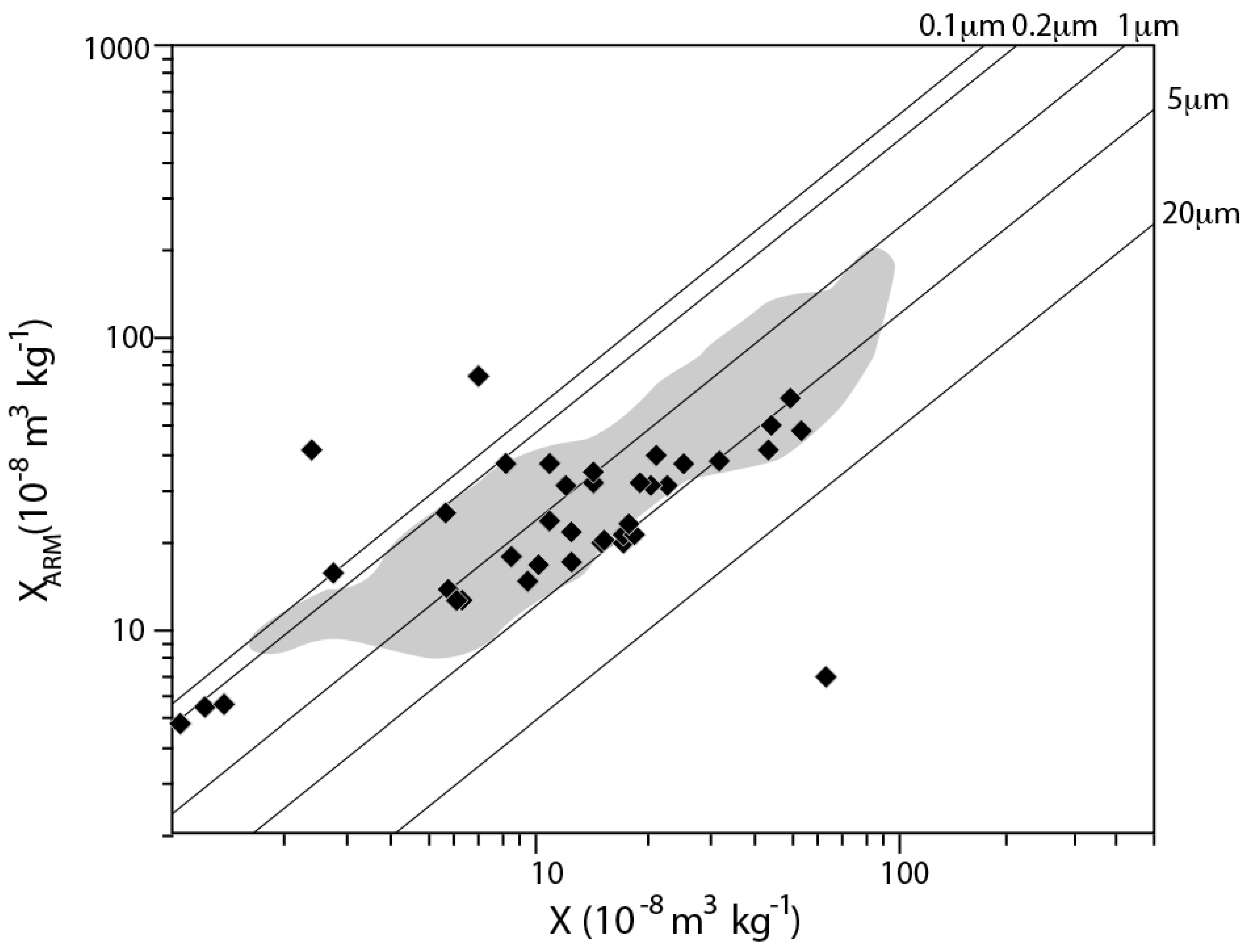

Finally, anhysteretic remanent magnetization (ARM) was imparted through the use of a custom-built alternating field (AF) demagnetizer. During the process, a DC bias field of 90 μT was superimposed on an alternating magnetic field with a peak amplitude of 100 mT. The induced ARM was then measured using a JR-5 induction magnetometer (AGICO), from which the anhysteretic susceptibility (χARM) was calculated. The relationship between χARM and low-field susceptibility (χ) was also explored through King’s plots (χARM vs. χ), following the method proposed by King et al. (1982), to assess variations in magnetic grain size.

2.4. Microscopy and Elemental Studies

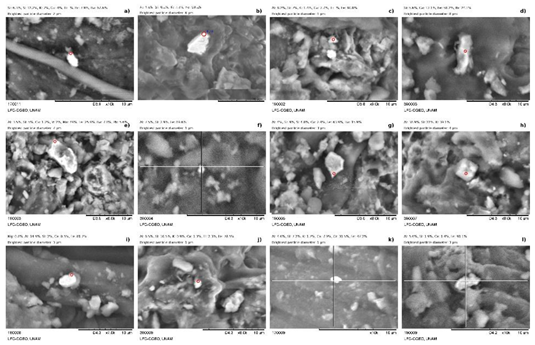

Several samples of Tillandsia individuals were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Philips XL30 microscope at the Institute of Geosciences, UNAM. Prior to imaging, all samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of graphite to improve electrical conductivity and enhance imaging contrast, particularly for metallic particles.

High-resolution micrographs were obtained to document surface morphology and particulate deposition. Special attention was given to the trichomes, where particulate matter was frequently observed embedded within their internal cavities. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was conducted using an integrated EDAX DX4 detector, with a detection threshold of approximately 0.5% by weight. This system enabled elemental characterization of both surface-bound and trichome-associated particles.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

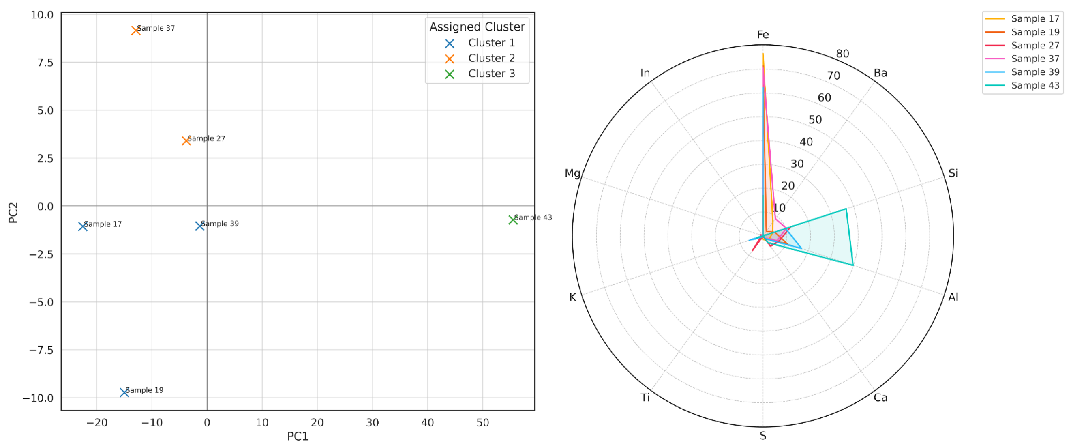

In order to identify patterns and reduce data dimensionality, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed using a combined dataset of magnetic and chemical variables. The magnetic variables included specific magnetic susceptibility (χ), anhysteretic remanent magnetization susceptibility (ARM) and the sample identification number. The chemical variables were obtained through energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX and included the following elements: Fe, Ba, Si, Cr, Al, Ca, S, Br, Ti, K, Cu, Mn, Pb, Mg, In, V, P, Nd, Ce, La, and W. All variables were z-score normalized prior to analysis to ensure comparability across different units and scales.

The PCA was executed in the R environment (version 4.3.1) using the FactoMineR and factoextra packages for both computation and visualization of the principal components. In parallel, a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was conducted using Ward’s linkage method and Euclidean distance as a dissimilarity metric. This clustering enabled the identification of natural groupings among the samples based on their multivariate composition. The resulting dendrograms were visualized using the ggdendro package. Additionally, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between magnetic and chemical variables to explore potential linear associations. Correlation matrices were generated with the corrplot package. All graphical outputs were created in RStudio.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Magnetic Properties

Magnetic parameters obtained from Tillandsia samples (see Supplementary Data) exhibited substantial variability, reflecting the diversity of pollution sources and intensities across the urban park. These parameters are critical for interpreting airborne particulate matter concentration, mineralogy, and grain size—key factors tightly linked to anthropogenic activity. Mass-specific magnetic susceptibility ranged from 0.87 to 40.00 × 10−8 m3·kg−1, with a mean value of 13.18 × 10−8 m3·kg−1 and a standard deviation of 10.07 × 10−8 m3·kg−1. Elevated χ values suggest an enrichment in ferrimagnetic minerals, most likely magnetite, commonly linked to vehicular emissions and urban dust sources. In contrast, near-zero or negative values suggest a dominance of diamagnetic or weakly magnetic materials, such as biological tissue or natural dust inputs.

Anhysteretic remanent magnetization, a proxy for low-coercivity, fine ferrimagnetic grains, ranged from 1.06 to 9.38 × 10−3 A·m2·kg−1 (mean: 3.04 × 10−3 A·m2·kg−1). The wide range reflects spatial heterogeneity in the intensity of magnetic particle deposition, likely influenced by proximity to traffic routes, topographical configuration, and vegetative cover.

Figure 2 (King’s plot) shows the logarithmic relationship between χ and χARM. Most samples fall between the 0.1 μm and 1 μm isolines, corresponding to fine, submicron particles in the respirable range. These grains are of concern due to their ability to penetrate the alveolar region, cross epithelial barriers, and transport toxic metals—such as Pb, Cd, and As—into systemic circulation. Their large surface area promotes reactive oxygen species generation, leading to oxidative stress, inflammation, and neurotoxicity, particularly in children and vulnerable populations.

Scheme 0.

m isoline, indicating the presence of ultrafine particles (UFPs), which are often produced by high-temperature combustion. UFPs can bypass physiological barriers and have been linked to neurodevelopmental deficits, cognitive decline, and systemic inflammation. On the opposite end, a few samples approach the 5 μm and 20 μm lines, suggesting the presence of coarse dust from soil, mechanical abrasion, or resuspension. These may deposit in the upper airways but still pose risks through metal adsorption and respiratory irritation. The coexistence of particles ranging from <0.1 to >10 μm within a recreational park is concerning, especially considering its use for physical exercise and children's play. Increased respiratory activity during exercise heightens the inhalation of fine and ultrafine particles, exacerbating potential health risks. Children are particularly susceptible due to higher ventilation rates per unit body mass and developmental sensitivity.

Scheme 0.

m isoline, indicating the presence of ultrafine particles (UFPs), which are often produced by high-temperature combustion. UFPs can bypass physiological barriers and have been linked to neurodevelopmental deficits, cognitive decline, and systemic inflammation. On the opposite end, a few samples approach the 5 μm and 20 μm lines, suggesting the presence of coarse dust from soil, mechanical abrasion, or resuspension. These may deposit in the upper airways but still pose risks through metal adsorption and respiratory irritation. The coexistence of particles ranging from <0.1 to >10 μm within a recreational park is concerning, especially considering its use for physical exercise and children's play. Increased respiratory activity during exercise heightens the inhalation of fine and ultrafine particles, exacerbating potential health risks. Children are particularly susceptible due to higher ventilation rates per unit body mass and developmental sensitivity.

Table 3. revealed two distinct magnetic behaviors. Group (a) displayed abrupt drops in magnetization near 580 °C, typical of magnetite. These samples were predominantly located in hightraffic and densely used sectors of the park (e.g., sites 17–20 and 34–39), consistent with elevated χ values shown in the magnetic susceptibility map (Figure 8). This pattern suggests substantial anthropogenic influence. In contrast, group (b) showed progressive demagnetization between 675–700 °C, characteristic of hematite. Samples 29 and 43 belonged to this group and exhibited paramagnetic behavior at high temperatures, likely due to oxidation processes. Field inspection confirmed their proximity to rusted metal barbecue structures, which may act as localized sources of oxidized iron particles.

Principal 5.

a–b) supported this interpretation. Sample 43 separated clearly along PC1, driven by high levels of Si, Al, and Ca—elements associated with mineral dust and thermal degradation. The agreement between magnetic and chemical data underscores the mineralogical heterogeneity of particles across the park. Overall, the spatial segregation of magnetic phases—magnetite near roads, hematite near rusted infrastructure—highlights the importance of considering both mineralogy and toxicological potential in urban air quality assessments. These findings reinforce the relevance of magnetic biomonitoring in identifying localized pollution sources in spaces frequented by vulnerable populations.

Principal 5.

a–b) supported this interpretation. Sample 43 separated clearly along PC1, driven by high levels of Si, Al, and Ca—elements associated with mineral dust and thermal degradation. The agreement between magnetic and chemical data underscores the mineralogical heterogeneity of particles across the park. Overall, the spatial segregation of magnetic phases—magnetite near roads, hematite near rusted infrastructure—highlights the importance of considering both mineralogy and toxicological potential in urban air quality assessments. These findings reinforce the relevance of magnetic biomonitoring in identifying localized pollution sources in spaces frequented by vulnerable populations.

3.2. SEM Observations and Elemental Content

The analysis performed via SEM-EDS on the composite image (Figure 4) reveals a wide diversity of suspended magnetic particles collected in the Zacatecas urban park. The particles exhibit varied morphologies and compositions, indicative of multiple anthropogenic sources.

Barium (Ba)-bearing particles were frequently identified, mainly as angular or semi-spherical grains ranging between 1 and 3 µm in diameter (Figures 4a, 4g). The most likely origin of these Ba-containing particles is vehicular activity, specifically brake pad wear and diesel fuel additives. The presence of barite (BaSO4) with characteristic cleavage has been previously documented in urban centers such as Italy (Varrica et al., 2013), Querétaro, Mexico (Castañeda-Miranda et al., 2014), and Warsaw, Poland (Górka et al., 2015). Due to their small size, these particles significantly contribute to the PM2.5 fraction, representing a health risk upon inhalation.

Iron-rich (Fe) particles dominate the SEM-EDS field and display both spheroidal and irregular morphologies. Spherical Fe oxides (e.g., magnetite), as observed in images 5f and 5j, are typical of high-temperature processes such as combustion and welding (Halvorsen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023). Irregular particles associated with Cr (Figure 4k) suggest mechanical abrasion and the degradation of vehicular components. These morphologies have also been reported in cities such as Singapore (Gupta et al.) and Tandil, Argentina (Marie et al., 2010).

Notably, titanium (Ti)-bearing particles were detected in several samples (e.g., figures 4b, and 4j), frequently associated with Fe and Al. The presence of Ti—commonly originating from paints, pigments (e.g., TiO2), or vehicular abrasion—raises concerns due to its capacity to form ultrafine particles with photocatalytic properties. These particles may promote the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon exposure to sunlight, exacerbating oxidative stress and cellular damage in the respiratory system.

In some cases, the Fe-rich particles displayed a high oxygen content and an irregular platy morphology, which is compatible with hematite (Fe2O3), particularly in figures 4d and 4l. Hematite is typically formed through oxidative processes and has been reported in environments with intense vehicular emissions and atmospheric aging. Although less magnetically responsive than magnetite, hematite contributes to the particulate matter burden and may be a marker of long-range transport or secondary atmospheric processes. Its presence in a park environment suggests infiltration from nearby traffic corridors or regional pollution events.

Lead (Pb)-bearing particles, as seen in figure 5e, appear as irregular bright grains, possibly composed of PbO or PbS. These particles are commonly associated with fossil fuel combustion, deteriorating paint, and wear on metal structures. Their high toxicity, particularly due to their small size, raises concerns considering that the park is a recreational zone frequently visited by children. Even trace exposure to lead has been linked to irreversible neurodevelopmental effects, especially in young populations.

Aluminum 4. b, 4c, 4h, and 4l) were also observed, likely originating from construction dust or soil resuspension. A critical finding is the small size of most particles (<4 µm), placing them within the respirable fraction (PM2.5 and PM1). These fractions are associated with severe health effects, including respiratory inflammation, cardiovascular diseases, and neurological impacts (Pope & Dockery, 2006; WHO, 2021).

Table 2. where most data points are concentrated in the region corresponding to particles ranging from 0.2 to 5 µm, typical of ultrafine particles. More than 60% of the particles fall within this range, which is particularly alarming in a recreational urban environment. Particles of these dimensions exhibit high pulmonary penetration capability and can reach the bloodstream, increasing the risk of chronic diseases.

3.3. Statistical Analysis.

Table 1. The PCA projection (Fig. 5a) explained a substantial proportion of the total variance, enabling a clear visual segregation of the samples into three interpretable clusters, which were confirmed via compositional radar plots (Fig. 5b).

Cluster 1, composed of Samples 17, 19, and 30, was grouped closely within the PCA space (Fig. 5a) and exhibited high relative concentrations of Fe, as shown in the radar diagram (Fig. 5b), indicating a strong magnetic signal and a dominant influence from vehicular activity and combustion-related sources. These samples displayed abrupt magnetization drops around 580 °C in their thermomagnetic curves (Fig. 3), consistent with the presence of magnetite. The sampling points for this cluster are located adjacent to heavily trafficked roads and dense commercial corridors, where little or no vegetation is available to buffer pollutant dispersion. Additionally, recent observations of welding and metallic cutting during building maintenance in nearby commercial structures support the hypothesis that Fe-rich aerosols were emitted and deposited at these sites.

Similar findings were reported in urban parks in Barcelona, where Moreno et al. (2019) observed that magnetite-rich particles originating from traffic emissions dominated the magnetic signal in green areas close to major roads. Likewise, Gonet and Maher (2019) demonstrated the high concentration of ultrafine magnetite particles in roadside tree leaves, linking them to vehicular emissions and oxidative stress markers. In Mexico, Castañeda-Miranda et al. (2016) also documented high χ and IRM values in Tillandsia recurvata near highways, directly associated with traffic intensity. These parallels reinforce the interpretation that the elevated magnetic parameters in Cluster 1 are primarily traffic-related. From a health perspective, magnetite nanoparticles are particularly concerning due to their submicron size and redox-active surface. Their inhalation facilitates translocation to the brain via the olfactory nerve and bloodstream, promoting neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and the aggregation of amyloid plaques (Maher et al., 2019). Given that children and elderly individuals widely use urban parks—two especially vulnerable groups—the presence of such particles demands urgent mitigation efforts.

Cluster 2, comprising Samples 27 and 37, presented lower Fe content and greater compositional heterogeneity. The radar plots (Figure 5b) revealed elevated concentrations of Ti, P, In, and Ba. These sites, also situated in commercial areas, may reflect the influence of ongoing construction, handling of composite materials, and diffuse emissions from nearby businesses, rather than direct industrial sources. Although no heavy industry is located near the park, the presence of small-scale workshops and building activity could explain the diversity of elemental signatures observed. Similar results were obtained in studies from Massachusetts, United States (Apeagyei et al., 2011), where commercial zones showed elevated Ba and Ti levels in deposited dust due to vehicular wear and civil works. The moderate magnetic signals of this group may indicate the presence of particles that are less enriched in ferrimagnetic phases but are still potentially hazardous upon inhalation.

Cluster 3, represented solely by Sample 43, was markedly distinct in both compositional and spatial terms. The elemental profile was dominated by Al and Si, indicating a mineral origin consistent with urban soil resuspension or clay-derived dust. Its thermomagnetic curve (Figure 3) confirmed the presence of hematite, which, along with that of Sample 29, likely resulted from surface oxidation of iron-containing silicates rather than anthropogenic combustion. Notably, Sample 43 was collected in a green zone physically isolated from traffic by tall walls and vegetation, confirming the protective role of urban design. This observation aligns with findings from the Triangle Area Barriers Study (TABS), where Hagler et al. (2012) demonstrated that tree cover and physical barriers significantly reduced magnetic loadings in soil and vegetation near highways.

3.4. Magnetic Monitoring

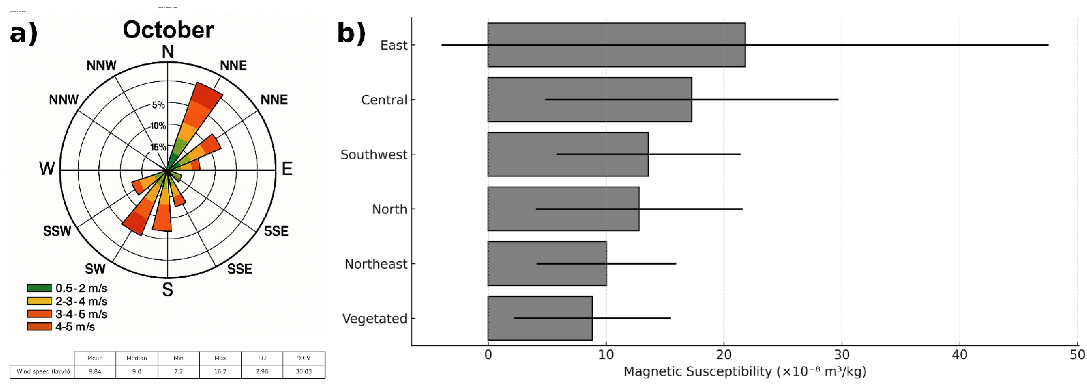

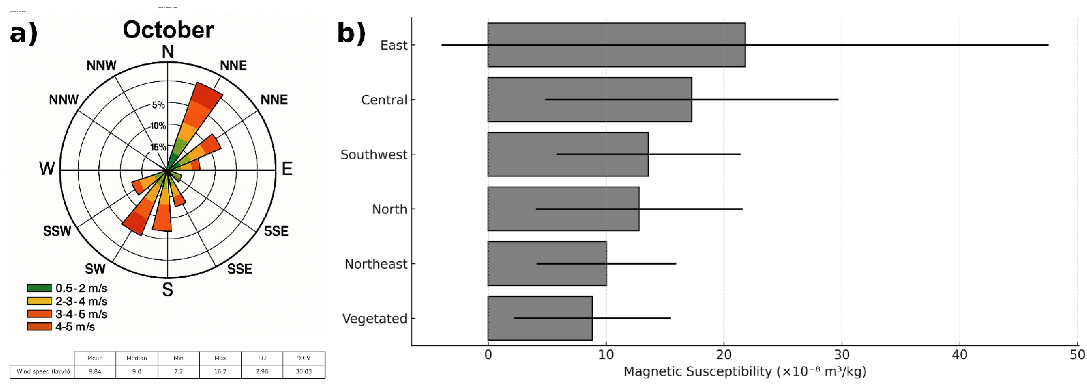

The spatial distribution of magnetic susceptibility within the Zacatecas urban park reflects a heterogeneous deposition pattern of magnetically responsive particles, with strong spatial dependence on atmospheric transport mechanisms and local geomorphology. According to the interpolated heat map (Figure 6), the central and southeastern park sectors—corresponding to sampling points 17–21 and 36–43—exhibited χ values exceeding 50.5 ×10

−8 m

3·kg

−1, forming distinct accumulation hotspots near high-density traffic corridors and zones of high human activity. As detailed in the sectorial average chart (Figure 7b), the central zone exhibited the highest mean χ values (34.1 ×10

−8 m

3·kg

−1), followed by the northeast (32.5 ×10

−8 m

3·kg

−1) and southwest sectors (31.8 ×10

−8 m

3·kg

−1). These areas are intensively used by the population for recreational purposes, including jogging, playgrounds, and informal sport activities. In contrast, the north (χ = 8.3 ×10

−8 m

3·kg

−1), east (χ = 7.9 ×10

−8 m

3·kg

−1), and vegetated buffer zones (10.2 ×10

−8 m

3·kg

−1) displayed the lowest magnetic loading, suggesting effective mitigation due to canopy cover and greater distance from emission sources.

Wind 7.

a, revealing dominant flows from the south (S to SSW) and the north-northeast (NNE), with wind speeds categorized between 0.5 and 5.0 m·s−1. These directions are consistent with the orientation of primary emission sources surrounding the park. The overlapping of wind corridors and areas of high χ further suggests that prevailing wind patterns actively shape advective transport and subsequent surface deposition of magnetically susceptible particles. Notably, the sampling campaign was conducted during the transition to the cold-dry season in Zacatecas, a period characterized by lower ambient temperatures, with mean daily values ranging from 10 to 15 °C, according to long-term climatological records from SMN-CONAGUA (Servicio Meteorológico Nacional de México, 2024). These meteorological conditions favor the development of thermal inversion layers and a shallow planetary boundary layer, which reduces turbulent mixing and limits the vertical dispersion of suspended particles. As a result, particles remain concentrated near the surface, leading to enhanced deposition rates on biological and artificial collectors—particularly in topographic depressions and wind-sheltered sectors of the park.

Wind 7.

a, revealing dominant flows from the south (S to SSW) and the north-northeast (NNE), with wind speeds categorized between 0.5 and 5.0 m·s−1. These directions are consistent with the orientation of primary emission sources surrounding the park. The overlapping of wind corridors and areas of high χ further suggests that prevailing wind patterns actively shape advective transport and subsequent surface deposition of magnetically susceptible particles. Notably, the sampling campaign was conducted during the transition to the cold-dry season in Zacatecas, a period characterized by lower ambient temperatures, with mean daily values ranging from 10 to 15 °C, according to long-term climatological records from SMN-CONAGUA (Servicio Meteorológico Nacional de México, 2024). These meteorological conditions favor the development of thermal inversion layers and a shallow planetary boundary layer, which reduces turbulent mixing and limits the vertical dispersion of suspended particles. As a result, particles remain concentrated near the surface, leading to enhanced deposition rates on biological and artificial collectors—particularly in topographic depressions and wind-sheltered sectors of the park.

While 2020. reported χ values between 30 and 60 ×10−8 m3·kg−1 near arterial roads in southern China, while Pietrelli et al. (2025) documented similar levels in parks adjacent to traffic corridors in Italy. Likewise, Castanheiro et al. (2016) observed magnetically enriched particles in urban green spaces in Antwerp, Belgium, with SIRM values ranging from 19 to 40 × 10−8 m3·kg−1, depending on the distance from roadways and vegetation coverage.

4. Conclusions

This study provides compelling evidence that Tillandsia recurvata is a reliable bioindicator for detecting spatial variability in airborne particulate pollution within urban parks. The combined use of magnetic monitoring and multivariate analyses enabled the identification of distinct pollution hotspots, characterized by elevated magnetic parameters—particularly χ and ARM—concentrated in areas adjacent to high-traffic corridors. These parameters correlated with elevated concentrations of Fe, Ba, Ti, and Pb, suggesting multiple anthropogenic sources, including vehicular abrasion, combustion, and surface material degradation.

King’s plots and SEM-EDS confirmed the predominance of (sub)micron magnetite-rich particles, many of which fall within the PM2.5 and PM1 ranges. The detection of ultrafine particles with redox-active properties is particularly concerning given the presence of vulnerable groups, such as children and the elderly, in these recreational areas. The thermomagnetic and morphological evidence further highlights the coexistence of magnetite and hematite particles, which are linked, respectively, to vehicular activity and localized corrosion sources.

Magnetic susceptibility mapping revealed that conventional linear transect sampling may underestimate exposure variability in open urban spaces. By deploying a surface-based grid with multiple sampling points, this study captured fine-scale deposition gradients driven by wind transport, site morphology, and the presence of vegetation buffers. Such methodology offers a more accurate assessment of real exposure scenarios faced by park users.

Ultimately, the findings reinforce the need for non-invasive, cost-effective tools in urban air quality assessment, especially in under-monitored regions. Magnetic biomonitoring with T. recurvata emerges as a scalable and sensitive approach for identifying pollution gradients and supporting decision-making processes aimed at improving environmental equity and public health in urban green spaces.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by project IG-101921. We thank Marina Vega González for her assistance with the SEM analyses, and Jorge Antonio Escalante González and Héctor Enrique Ibarra Ortega for their support in the magnetism laboratory. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions, which greatly improved this manuscript.

Data availability

Data available on demand.

Funding

This work was funded by: UNAM-DGAPA PAPITT IG-101921.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adamiec, E.; Jarosz-Krzemińska, E.; Wieszała, R. Heavy metals from non-exhaust vehicle emissions in urban and motorway road dusts. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2016, 188, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.U.; Liu, G.; Yousaf, B.; Ullah, H.; Abbas, Q.; Munir, M.A.M. A systematic review on global pollution status of particulate matter-associated potential toxic elements and health perspectives in urban environment. Environmental geochemistry and health 2019, 41, 1131–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apeagyei, E.; Bank, M.S.; Spengler, J.D. Distribution of heavy metals in road dust along an urban-rural gradient in Massachusetts. Atmospheric Environment 2011, 45, 2310–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago Posada, D.; Chaparro, M.A.; Duque-Trujillo, J.F. Magnetic assessment of transplanted Tillandsia spp.: Biomonitors of air particulate matter for high rainfall environments. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheiro, A.; Samson, R.; De Wael, K. Magnetic and particle-based techniques to investigate metal deposition on urban green. Science of the Total Environment 2016, 571, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda-Miranda, A.G.; Böhnel, H.N.; Molina-Garza, R.S.; Chaparro, M.A. Magnetic evaluation of TSP-filters for air quality monitoring. Atmospheric environment 2014, 96, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Miranda, A.G.; Chaparro, M.A.; Chaparro, M.A.; Böhnel, H.N. Magnetic properties of Tillandsia recurvata L. and its use for biomonitoring a Mexican metropolitan area. Ecological Indicators 2016, 60, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Miranda, A.G.; Chaparro, M.A.; Pacheco-Castro, A.; Chaparro, M.A.; Böhnel, H.N. Magnetic biomonitoring of atmospheric dust using tree leaves of Ficus benjamina in Querétaro (Mexico). Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2020, 192, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, M.A.E.; Chaparro, M.A.E.; Castañeda Miranda, A.G.; Böhnel, H.N.; Sinito, A.M. (2015). An interval fuzzy model for magnetic biomonitoring using the species Tillandsia recurvata L.

- Chaparro, M.A.; Posada, D.B.; Chaparro, M.A.; Molinari, D.; Chiavarino, L.; Alba, B.; Marié, D.C.; Natal, M.; Böhnel, H.N.; Vaira, M. Urban and suburban airborne magnetic particles accumulated on Tillandsia capillaris. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 907, 167890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, M.A.E.; Chaparro, M.A.E.; Molinari, D.A. A fuzzy-based analysis of air particle pollution data: An index IMC for magnetic biomonitoring. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, C.; Zou, R.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Z. Experimental examination of the effectiveness of vegetation as a bio-filter of particulate matter in the urban environment. Environmental Pollution 2016, 208, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional del Agua. Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. (2023). Boletines climatológicos y pronósticos diarios de precipitación. Gobierno de México. Recuperado de https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/.

- CONAGUA. (2023). Programa Hídrico Regional Visión 2030: Región Hidrológica Administrativa VI - Río Bravo. Comisión Nacional del Agua. https://www.gob.mx/conagua.

- Cori, L.; Donzelli, G.; Gorini, F.; Bianchi, F.; Curzio, O. Risk perception of air pollution: A systematic review focused on particulate matter exposure. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, G.C.; Zhuang, Y.J.; Cho, M.H.; Huang, C.Y.; Xiao, Y.F.; Tsai, K.H. Review of total suspended particles (TSP) and PM2.5 concentration variations in Asia during the years of 1998–2015. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2018, 40, 1127–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargiulo, J.D.; Kumar, R.S.; Chaparro, M.A.; Chaparro, M.A.; Natal, M.; Rajkumar, P. Magnetic properties of air-suspended particles in 38 cities from South India. Atmospheric Pollution Research 2016, 7, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givehchi, R.; Arhami, M.; Tajrishy, M. Contribution of the Middle Eastern dust source areas to PM10 levels in urban receptors: Case study of Tehran, Iran. Atmospheric environment 2013, 75, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonet, T.; Maher, B.A. Airborne, vehicle-derived Fe-bearing nanoparticles in the urban environment: A review. Environmental Science & Technology 2019, 53, 9970–9991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, L. (2022). Diagnóstico de movilidad urbana en Zacatecas-Guadalupe. Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas.

- Górka-Kostrubiec, B. The magnetic properties of indoor dust fractions as markers of air pollution inside buildings. Building and Environment 2015, 90, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudie, A.S. Desert dust and human health disorders. Environment international 2014, 63, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. (2019). Vehicle-generated heavy metal pollution in an urban environment and its distribution into various environmental components. In Environmental Concerns and Sustainable Development: Volume 1: Air, Water and Energy Resources (pp. 113–127). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Hagler, G.S.; Lin, M.Y.; Khlystov, A.; Baldauf, R.W.; Isakov, V.; Faircloth, J.; Jackson, L.E. Field investigation of roadside vegetative and structural barrier impact on near-road ultrafine particle concentrations under a variety of wind conditions. Science of the Total Environment 2012, 419, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, J.Ø. (2021). Exposure assessment and particle characterization of workplace aerosols in Norwegian metal laser-cutting industry (Doctoral dissertation, Norwegian University of Life Sciences).

- Hofman, J.; Maher, B.A.; Muxworthy, A.R.; Wuyts, K.; Castanheiro, A.; Samson, R. Biomagnetic monitoring of atmospheric pollution: A review of magnetic signatures from biological sensors. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51, 6648–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, J.; Marx, S.K.; May, J.H.; Lupo, L.C.; Kulemeyer, J.J.; Pereira, E.D.L. Á. . & Zawadzki, A. Dust deposition tracks late-Holocene shifts in monsoon activity and the increasing role of human disturbance in the Puna-Altiplano, northwest Argentina. The Holocene 2020, 30, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. (2020). Anuario estadístico y geográfico de Zacatecas 2020. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=889463541662.

- King, J.W.; Banerjee, S.K.; and Marvin, J. A new rock-magnetic approach to selecting samples for geomagnetic paleointensity studies: Applications to paleointensity for the last 4000 years. Journal of Geophysical Research 1983, 88, 5911–5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. (2024). Epiphytes as a Sustainable Biomonitoring Tool for Environmental Pollutants. In Biomonitoring of Pollutants in the Global South (pp. 359–390). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- LEE, I.S.R. (2007). Design and Development of a Passive Large Particle.

- Li, S.; Wang, G.; Geng, Y.; Wu, W.; Duan, X. Lung function decline associated with individual short-term exposure to PM1, PM2.5 and PM10 in patients with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 851, 158151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.Y.; Peng, Z.X.; Zhang, B.W.; Wang, S.K.; Wang, X.S. Morphology, mineralogical composition, and heavy metal enrichment characteristics of magnetic fractions in coal fly ash. Environmental Earth Sciences 2023, 82, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Liu, F.; Huang, K.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Xiao, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Cao, J.; Shen, C.; et al. Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter and cardiovascular disease in China. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020, 75, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guan, D.; Peart, M.R.; Wang, G.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z. The dust retention capacities of urban vegetation—A case study of Guangzhou, South China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2013, 20, 6601–6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Gui, J.; Zhang, B.; Yang, H.; Lu, D.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Q.; Li, Z.; Jiang, G. Traffic-derived magnetite pollution in soils along a highway on the Tibetan Plateau. Environmental Science: Nano 2022, 9, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, B.A. Magnetic properties of some synthetic sub-micron magnetites. Geophysical Journal International 1988, 94, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, B.A. Airborne magnetite-and iron-rich pollution nanoparticles: Potential neurotoxicants and environmental risk factors for neurodegenerative disease, including Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2019, 71, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manisalidis, I.; Stavropoulou, E.; Stavropoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and health impacts of air pollution: A review. Frontiers in public health 2020, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marié, D.C.; Chaparro, M.A.; Gogorza, C.S.; Navas, A.; Sinito, A.M. Vehicle-derived emissions and pollution on the road Autovia 2 investigated by rock-magnetic parameters: A case study from Argentina. Studia Geophysica et Geodaetica 2010, 54, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marié, D.C.; Chaparro, M.A.; Lavornia, J.M.; Sinito, A.M.; Miranda, A.G.C.; Gargiulo, J.D.; Böhnel, H.N. Atmospheric pollution assessed by in situ measurement of magnetic susceptibility on lichens. Ecological Indicators 2018, 95, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, B.A. Airborne magnetite-and iron-rich pollution nanoparticles: Potential neurotoxicants and environmental risk factors for neurodegenerative disease, including Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2019, 71, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Echeverry, D.; Chaparro, M.A.E.; Duque-Trujillo, J.F.; Chaparro, M.A.E.; Castañeda-Miranda, A.G. Magnetic biomonitoring of air pollution in a tropical valley using a Tillandsia sp. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 283. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.G.C.; Chaparro, M.A.; Chaparro, M.A.; Böhnel, H.N. Magnetic properties of Tillandsia recurvata L. and its use for biomonitoring a Mexican metropolitan area. Ecological Indicators 2016, 60, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedźwiedź, T.; Łupikasza, E.B.; Małarzewski, Ł.; Budzik, T. Surface-based nocturnal air temperature inversions in southern Poland and their influence on PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations in Upper Silesia. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2021, 146, 897–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y.; Gilbreath, S.; Barakatt, E. Respiratory outcomes of ultrafine particulate matter (UFPM) as a surrogate measure of near-roadway exposures among bicyclists. Environmental Health 2017, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrelli, L.; Di Vito, S.; Lacolla, E.; Piozzi, A.; Scocchera, E. Characterization of urban park litter pollution. Waste Management 2025, 193, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, C.A.; Dockery, D.W. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: Lines that connect. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2006, 56, 709–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prendez Bolívar, M.M.; Carvallo, C.; Godoy, N.; Egas, C.; Aguilar Reyes, B.O.; Calzolai, G.; Fuentealba, R.; Lucarelli, F.; Nava, S. Magnetic and elemental characterization of the particulate matter deposited on leaves of urban trees in Santiago, Chile. Environ. Geochem. Heal. 2023, 45, 2629–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Trejo, A.; Böhnel, H.N.; Ibarra-Ortega, H.E.; Salcedo, D.; González-Guzmán, R.; Castañeda-Miranda, A.G.; Sánchez-Ramos, L.E.; Chaparro, M.A. Air Quality Monitoring with Low-Cost Sensors: A Record of the Increase of PM2.5 during Christmas and New Year’s Eve Celebrations in the City of Queretaro, Mexico. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawidis, T.; Krystallidis, P.; Veros, D.; Chettri, M. A study of air pollution with heavy metals in Athens city and Attica basin using evergreen trees as biological indicators. Biological trace element research 2012, 148, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Kumar, P. Integrated dispersion-deposition modelling for air pollutant reduction via green infrastructure at an urban scale. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 723, 138078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.T.; Adam, M.G.; Tham, K.W.; Schiavon, S.; Pantelic, J.; Linden, P.F.; Sofianopoulou, E.; Sekhar, S.C.; Cheong, D.K.W.; Balasubramanian, R. Assessment and mitigation of personal exposure to particulate air pollution in cities: An exploratory study. Sustainable Cities and Society 2021, 72, 103052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varrica, D.; Bardelli, F.; Dongarra, G.; Tamburo, E. Speciation of Sb in airborne particulate matter, vehicle brake linings, and brake pad wear residues. Atmospheric environment 2013, 64, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashist, M.; Kumar, T.V.; Singh, S.K. A comprehensive review of urban vegetation as a Nature-based Solution for sustainable management of particulate matter in ambient air. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2024, 31, 26480–26496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Peng, C.; Peng, C. Effects of street plants on atmospheric particulate dispersion in urban streets: A review. Environmental Reviews 2024, 32, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). WHO global air quality guidelines: Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228.

- Wróblewska, K.; Jeong, B.R. Effectiveness of plants and green infrastructure utilization in ambient particulate matter removal. Environmental Sciences Europe 2021, 33, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.Y. A Review on PM 2.5 Sources, Mass Prediction, and Association Analysis: Research Opportunities and Challenges. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, H.; Luo, X.S.; Huang, W.; Pang, Y.; Yang, J.; Tang, M.; Mehmood, T.; Zhao, Z. Toxicity assessment and heavy metal components of inhalable particulate matters (PM2.5 & PM10) during a dust storm invading the city. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2022, 162, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).