Submitted:

03 September 2023

Posted:

05 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

3. Results and discussions

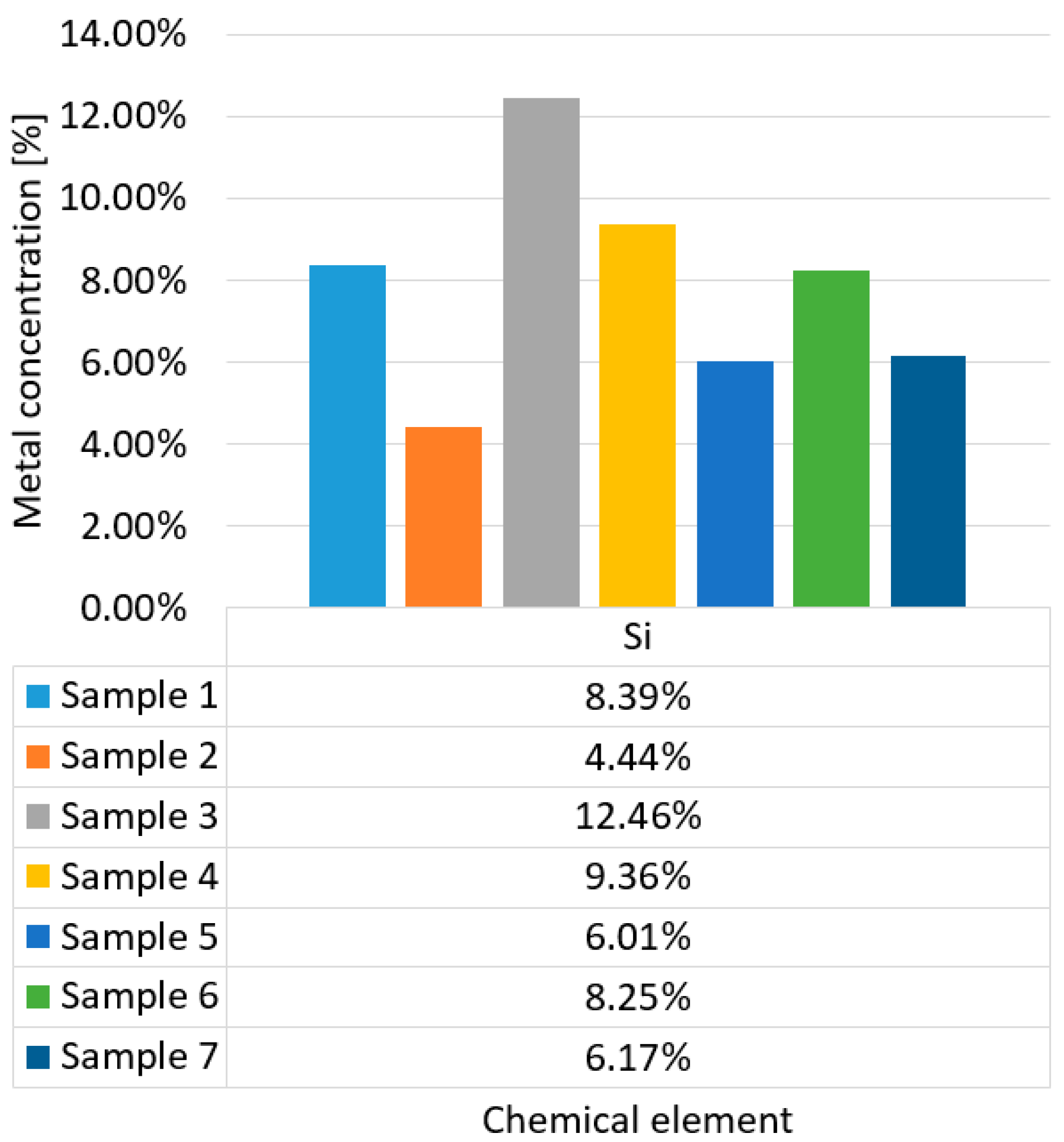

3.1. Determination of metal concentrations from dust samples

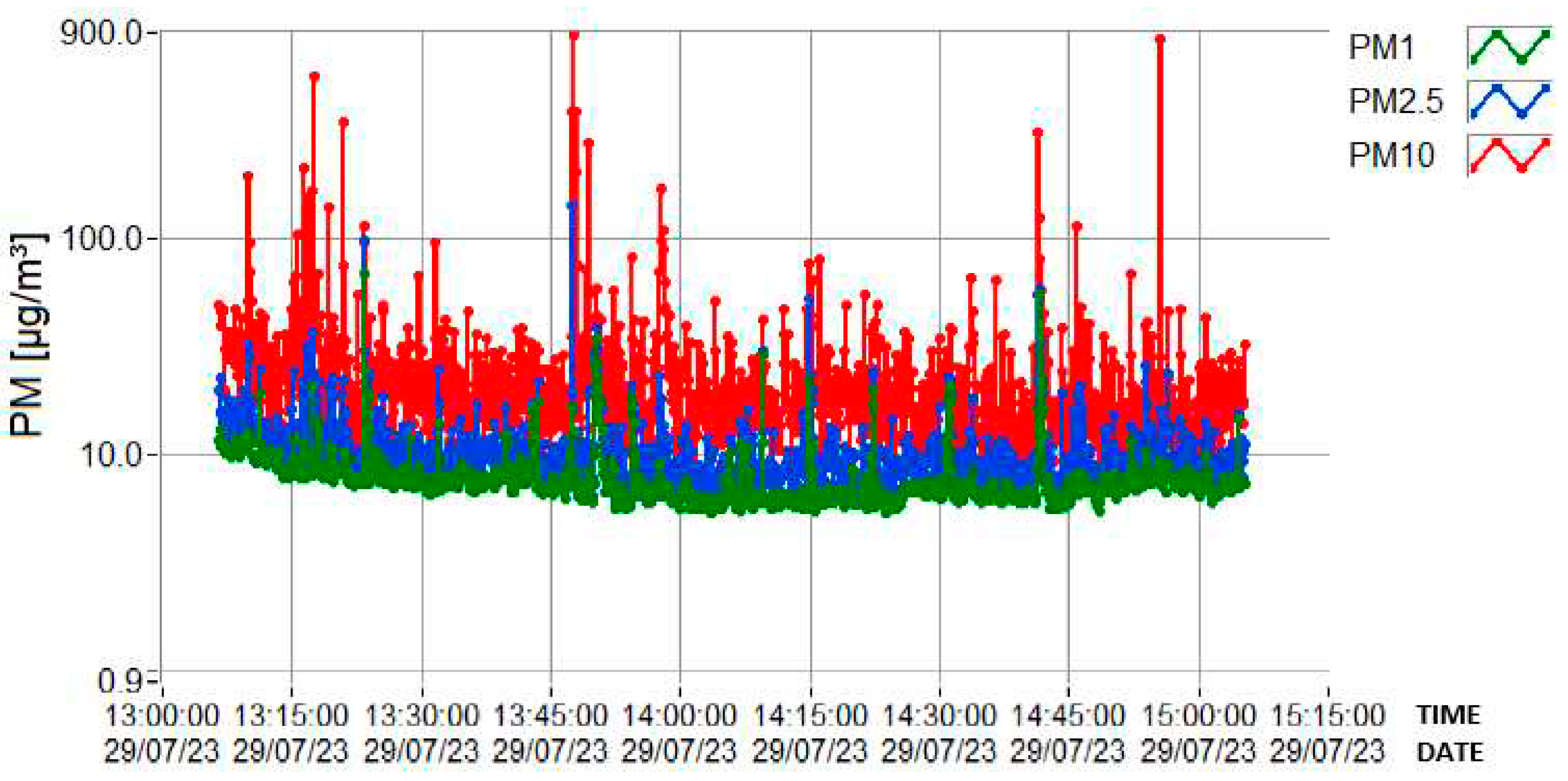

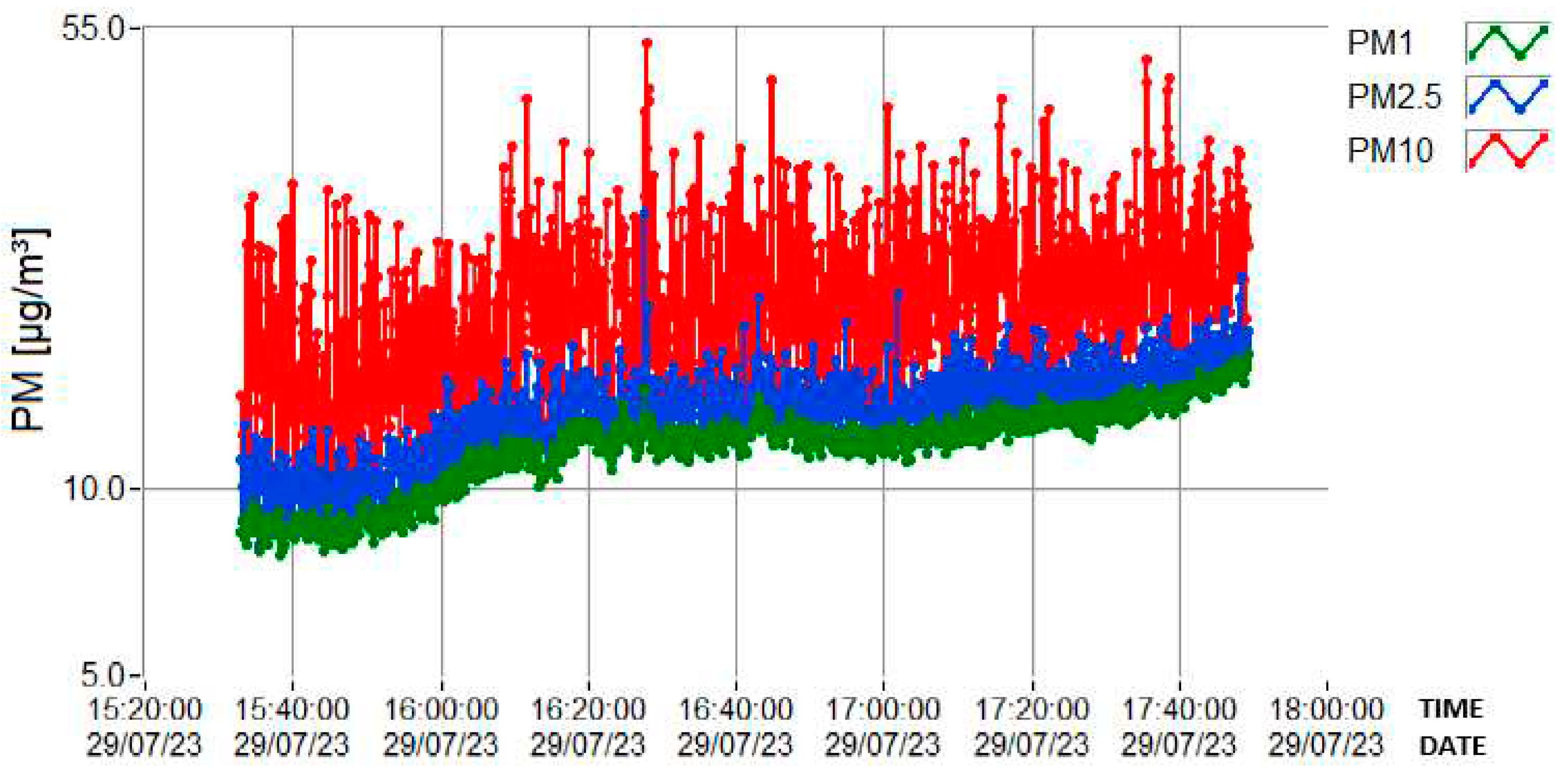

3.2. Determination of PM concentrations using DLS spectrometer

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thorpe A., Harrison R. M., Sources and proprieties of non-exhaust particulate matter from road traffic: a review – 2008 The Science of the total environment 08/2008, 400, 270-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2208.06.007. [CrossRef]

- Harrison R. M., Beddows D., Efficacy of Recent Emissions Controls on Road Vehicles in Europe and Implications for Public Health, Scientific Reports 7, 12/2017, 1152. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01135-2. [CrossRef]

- Harrison R. M., Pant P., Estimation of the contribution of road traffic emissions to particulate matter concentrations from field measurements: A review – 2013, Atmospheric Environment 2013, 77, 78-97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.04.028. [CrossRef]

- “OECD-iLibrary,” [Online]. Available: https://www.oecd.org/environment/non-exhaust-particulate-emissions-from-road-transport-4a4dc6ca-en.htm [Accesed 20.05.2023].

- Harrison R. M., Allan J. D., Carruthers D., Williams A., Heal M. R., Alastair C, Lewis, Marner B., Murells P., Non-Exhaust Vehicle Emissions of Particulate Matter and VOC froam Road Traffic: A review – 2021 Atmospheric Environment 2021, 262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2021.118592. [CrossRef]

- Celo V., Yassine M. Y.,Dabek E. – Insights into Elemental Composition and Sources of Fine and Coarse Particulate Matter in Dense Traffic Areas in Toronto and Vancouver, Canada 10/2021, 9(10), 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics9100264. [CrossRef]

- Badaloni C., Cesaroni G., Cerza F., Davoli M., Brunekreef B., Forastiere F. - Effects of long-term exposure to particulate matter and metal components on mortality in the Rome longitudinal study – 07/2017 Environmental International, 109, 146-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.09.005. [CrossRef]

- Eeftens M., Hoek G., Gruzieva O., Moelter A., Agius R., Beelen R., Brunekreef B., Custovic A., Cyrys J., Fuertes E., – Elemental Composition of Particulate Matter and the Association with Lung Function – 07/2014 Epidemiology, 25, 648-657. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000136. [CrossRef]

- Thomson E.M., Breznan D., Karthikeyan S., MacKinnon-Roy C., Charland J-P., Zlotorzynska E. D., Celo V., Kumarathasan P., Brook J.R., and Vincent R.- Cytotoxic and inflammatory potential of size-fractionated particulate matter collected repeatedly within a small urban area – Particle and fibre toxicology – 2015, 12:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12989-015-0099-z. [CrossRef]

- Garg B., Cadle S. H., Mulawa P. A., Groblicki P. - Brake Wear Particulate Matter Emissions - Environmental Science and Technology 2000, 34, 21, 4463–4469. https://doi.org/10.1021/es001108h. [CrossRef]

- Sanders P., Xu N., Dalka T., Maricq M. - Airborne brake wear debris: size distributions, composition, and a comparison of dynamometer and vehicle tests – Environmental science and technology – 2003, 37, 18, 4060–4069. https://doi.org/10.1021/es034145s. [CrossRef]

- Mosleh M., Blau P. J., Dumitrescu D.- Characteristics and morphology of wear particles from laboratory testing of disk brake materials – WEAR – 2004, 256, 1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2003.07.007. [CrossRef]

- Rødland E. S., Lind O. C., Reid M. J., Heier L., Okoffo E., Rauert C., Thomas K., Meland S. - Occurrence of tire and road wear particles in urban and peri-urban snowbanks, and their potential environmental implications - Science of The Total Environment – 06/2022, 824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153785. [CrossRef]

- Kukutschová J., Moravec P., Tomášek V., Matějka V., Smolík J., Schwarz J., Seidlerová J., Safářová K., Filip F.- On airborne nano/micro-sized wear particles released from low-metallic automotive brakes – Environmental Pollution – 2011, 159, 998-1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2010.11.036. [CrossRef]

- Harrison R. M., Jones A. M., Gietl J., Yin J., Green D. - Estimation of the contributions of brake dust, tire wear, and resuspension to nonexhaust traffic particles derived from atmospheric measurements – Environmental Science and technology – 2012, 46(12), 6523-6529. https://doi.org/10.1021/es300894r. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P., Pirjola L., Ketzel M., Harrison R.M.- Nanoparticle emissions from 11 non-vehicle exhaust sources – A review – Atmospheric Environment – 2013, 67, 252-277, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.11.011. [CrossRef]

- Woo S-H.,Jang H., Lee S-B., Lee S. - Comparison of total PM emissions emitted from electric and internal combustion engine vehicles: An experimental analysis – Science of The Total Environment, 2022, 842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156961. [CrossRef]

- Liu T., Wang X., Deng W., Zhang Y. - Role of ammonia in forming secondary aerosols from gasoline vehicle exhaust – Science China-Chemistry – 05/2015, 58, 1377–1384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11426-015-5414-x. [CrossRef]

- Wu D., Ding X., Li Q., Sun J., Huang C., Yao L., Wang X., Ye X., Chen Y., He H., Chen J-M. - Pollutants emitted from typical Chinese vessels: Potential contributions to ozone and secondary organic aerosols - Journal of Cleaner Production – 2019, 238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117862. [CrossRef]

- Boucher J., Billard G., Simeone E. and Sousa J. - The marine plastic footprint - IUCN, Global Marine and Polar Program , 2020.

- Ulrike B., Stein U., Hannes S. - Analysis of Microplastics - Sampling, preparation and detection methods - Status Report within the framework program Plastics in the Environment, 2021.

- Baensch-Baltruschat B., Kocher B., Kochleus C., Stock F., Reifferscheid G. - Tyre and road wear particles - A calculation of generation, transport and release to water and soil with special regard to German roads - The Science of The Total Environment, 2021, 752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141939. [CrossRef]

- Baensch-Baltruschat B., Kocher B., Kochleus C., Stock F., Reifferscheid G - Tyre and road wear particles (TRWP) - A review of generation, properties, emissions, human health risk, ecotoxicity, and fate in the environment - The Science of The Total Environment, 2020, 733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137823. [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand T., Toussaint D., Böhm E. - Discharges of copper, zinc and lead to water and soil -analysis of the emission pathways and possible emission reduction measures - ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH OF THE FEDERAL MINISTRY OF THE ENVIRONMENT, NATURE CONSERVATION AND NUCLEAR SAFETY, 2018, 202 242 20/02.

- Leifheit E. F., Kissener H. L., Faltin E., Ryo M., Rillig M. C. - Tire abrasion particles negatively affect plant growth even at low concentrations and alter soil biogeochemical cycling - Soil Ecology Letters, 2022, 4, 409-415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42832-021-0114-2. [CrossRef]

- Luo Z., Zhou X., Su Y., Wang H., Yu R., Zhou S., Xu E. G., Xing B. - Environmental occurrence, fate, impact, and potential solution of tire microplastics: Similarities and differences with tire wear particles - The Science of The Total Environment, 2021, 795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148902. [CrossRef]

- Unice K. M., Weeber M. P., Abramson M. M., Reid R. C. D., van Gils J. A. G., Markus A. A., Vethaak A. D., Panko J. M. - Characterizing export of land-based microplastics to the estuary - Part I: Application of integrated geospatial microplastic transport models to assess tire and road wear particles in the Seine watershed - The Science of The Total Environment, 2019, 646, 1639-1649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.368. [CrossRef]

- Unice, K. M.; Weeber, M. P.; Abramson, M. M.; Reid, R. C.D.; van Gils, J. A.G.; Markus,A. A.; Vethaak, A. D.; Panko, J. M. - Characterizing export of land-based microplastics to the estuary - Part II Sensitivity analysis of an integrated geospatial microplastic transport modeling assessment of tire and road wear particles - The Science of The Total Environment, 2019, 646, 1650-1659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.301. [CrossRef]

- Kawecki D. and Nowack B. - Polymer-Specific Modeling of the Environmental Emissions of Seven Commodity Plastics As Macro- and Microplastics – Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53, 9664-9676, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b02900. [CrossRef]

- Lebreton L., van der Zwet J., Damsteeg J., Slat B., Andrady A., Reisser J. - River plastic emissions to the world’s oceans – Nature communications, 2017, 8, 15611. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15611. [CrossRef]

- Denny M., Baskaran M., Burdick S., Tummala C., Dittrich T. - Investigation of pollutant metals in road dust in a post-industrial city: Case study from Detroit, Michigan – Environmental Scientific, 2022, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.974237. [CrossRef]

- Apeagyei E., Bank M., Spengler J. - Distribution of heavy metals in road dust along an urban-rural gradient in Massachusetts - Atmospheric Environment, 2011, 45, 2310-2323, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.11.015. [CrossRef]

- Mustata D. M., Popa R. M., Ionel I., Dughir C., Bisorca D. - A study on particulate matter from an area with high traffic intensity – Applied Sciences, 13(15), 8824 https://doi.org/10.3390/app13158824. [CrossRef]

- Horiba. Available online: https://www.horiba.com/gbr/scientific/technologies/dynamic-light-scattering-dls-particle-size-distribution-analysis/dynamic-light-scattering-dls-particle-size-distribution-analysis/#:~:text=Particle%20size%20can%20be%20determined,elastic%20light%20scattering%20(QELS) (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Aguilera A., Cortes J. L., Delgado C., Aguilar Y., Aguilar D., Cejudo R., Quintana P., Goguitchaichvili A., Bautista F. - Heavy Metal Contamination (Cu, Pb, Zn, Fe, and Mn) in Urban Dust and its Possible Ecological and Human Health Risk in Mexican Cities - Sec. Toxicology, Pollution and the Environment, 14.03.2022, 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.854460. [CrossRef]

- 362/2010 Coll Decree of the Ministry of Agriculture, Environment and Regional Development of the Slovak Republic, Which Lays Down Requirements for Fuel Quality and Keeping Operational Records on Fuels. [(accessed on 16 August 2023)]. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2010/362/vyhlasene_znenie.html.

- Shi G., Chen Z., Xu S., Zhang J., Wang L., Bi C., Teng J. - Potentially toxic metal contamination of urban soils and roadside dust in Shanghai, China. Environ. Pollution. 2008; 156:251–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2008.02.027. [CrossRef]

- American Chemical Society. “U.S. Synthetic Rubber Program - National Historic Chemical Landmark,” accessed on 16 August 2023. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/syntheticrubber.html.

- Shailendra K., Ranjeet K., Krishnakant K., Siddarth S. - Concentration, sources and health efects of silica in ambient respirable dust of Jharia Coalfelds Region, India – Environmental Sciences Europe, 2022, 34:68, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00651-x. [CrossRef]

- NIOSH, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (1994) Manual of analytical methods; method 7602, silica crystalline by IR. 4th (ed) Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Steenland K, Mannetje A, Bofetta P, Stayner L, International Agency for Research on Cancer et al (2001) Pooled exposure response analyses and risk assessment for lung cancer in 10 cohorts of silica-exposed workers: an IARC multicentre study. Cancer Causes Control 12:773–784, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1012214102061. [CrossRef]

- Background document for silica, crystalline (respirable size) (1998) Report on carcinogens. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services, National Toxicology Program Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709, USA. https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/newhomeroc/other_background/silica_no_app_508.pdf. Accessed 17 August 2023.

- Adeyanju E., Okeke C. A. - Exposure effect to cement dust pollution: a mini review, Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019, 1:1572 | https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1583-0. [CrossRef]

- Meteo blue. Available online: https://www.meteoblue.com/ro/vreme/archive/export/dumbr%c4%83vi%c8%9ba_rom%c3%a2nia_678688?fcstlength=1m&year=2023&month=7 (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Romanian Law no. 104 from 15 June 2011 in Relation to Air Quality (Original in Romanian: LEGE nr. 104 Din 15 Iunie 2011 Privind Calitatea Aerului Înconjurător) Parliament of Romania. Available online: http://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/129642 (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- European Union Directive Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on Ambient Air Quality and Cleaner Air for EUROPE.

| Variable | PM1 (µg/m3) | PM2.5 (µg/m3) | PM10 (µg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 5.4 | 6.1 | 6.1 |

| Maximum | 68.6 | 143 | 889.8 |

| Mean | 7.9 | 10.7 | 27.1 |

| Variable | PM1 (µg/m3) | PM2.5 (µg/m3) | PM10 (µg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 7.8 | 8.1 | 8.4 |

| Maximum | 16.4 | 27.7 | 52.3 |

| Mean | 11.7 | 13.3 | 20.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).