Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

11 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Hubble function at redshift z | |

| Present Hubble constant | |

| Matter density parameter | |

| Radiation density parameter | |

| Effective curvature contribution (“curvature window”) | |

| Fractal Early Energy (entropy-driven early component) | |

| Buchert backreaction term replacing dark energy | |

| , | Present amplitude and scaling exponent of |

| Effective mass–fractal dimension | |

| Primordial (high-z) fractal dimension after UBH burst | |

| Steepness parameter of fractal dimension evolution | |

| a | Scale factor, |

| , | Center and width of curvature window |

| Transition scale of fractal early energy | |

| Amplitude parameter of | |

| Comoving distance, | |

| Curvature–dependent distance function | |

| Angular-diameter distance | |

| Transverse comoving distance | |

| Luminosity distance, | |

| Comoving sound horizon at recombination | |

| Acoustic angle at recombination | |

| M | Absolute magnitude calibration of SN-Ia sample |

| Offset between observed and theoretical magnitudes | |

| c | Speed of light |

2. Theoretical Framework and Methods

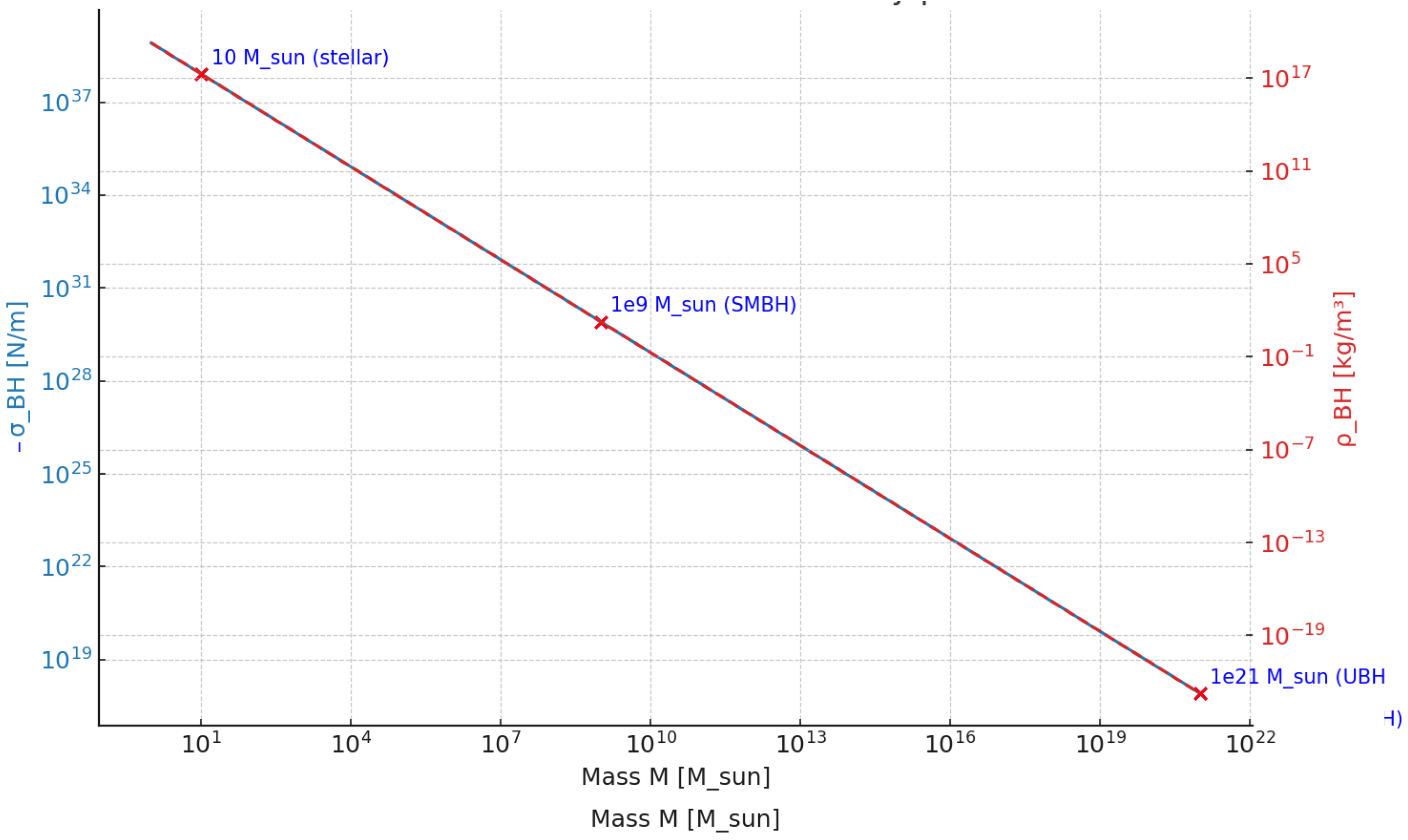

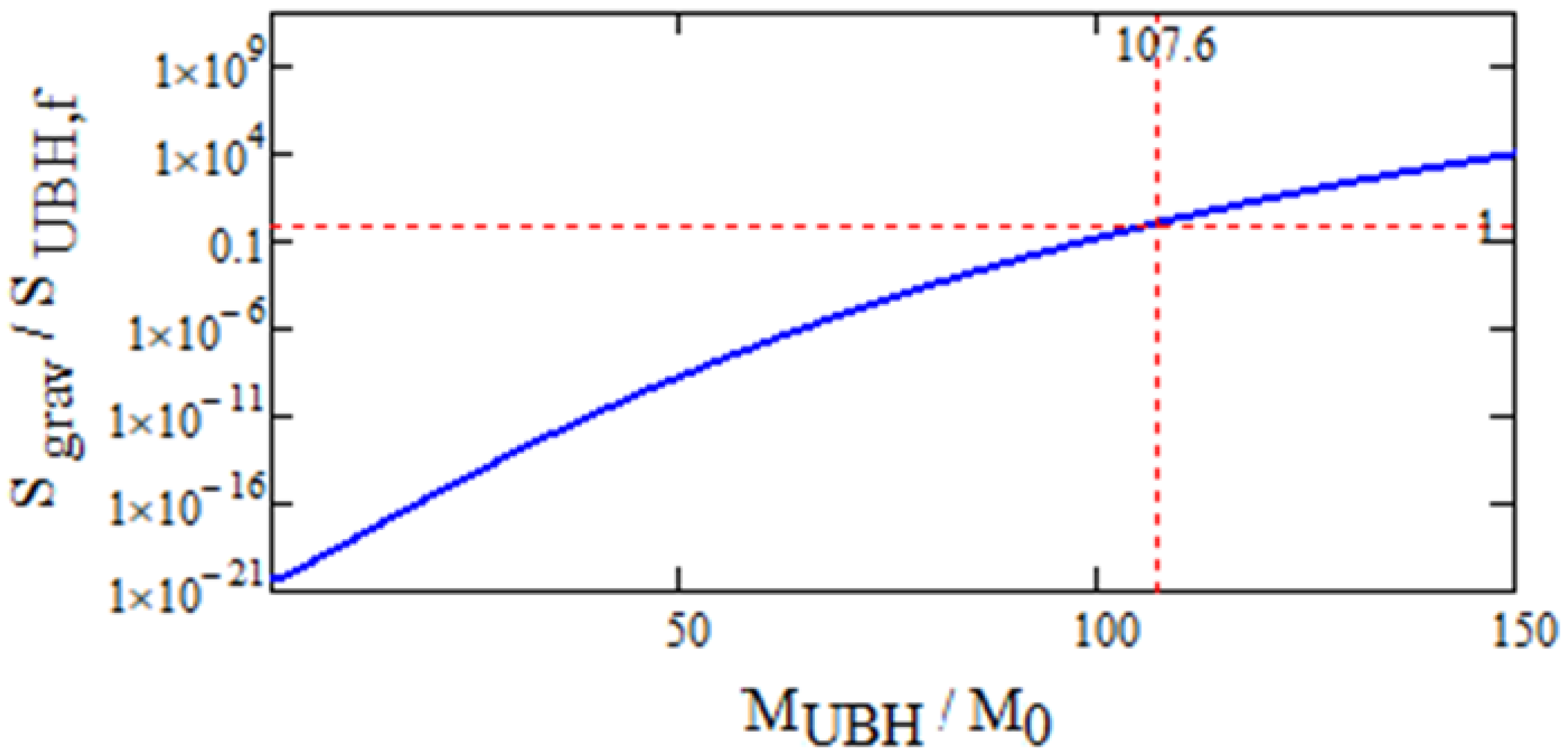

2.1. Fractal Horizon Concept, Entropy Scaling, and Critical UBH Mass

On the Physical Scale Ratio

2.2. Limitations of Redshift-from-Scattering Models

2.3. The UBH Hubble Function with Backreaction

2.4. Fractal Early Energy (FEE)

2.5. Curvature Window and Fractal Scaling

2.6. UBH Hubble Function for all Redshift Values

2.7. Luminosity Distance in the UBH Cosmology

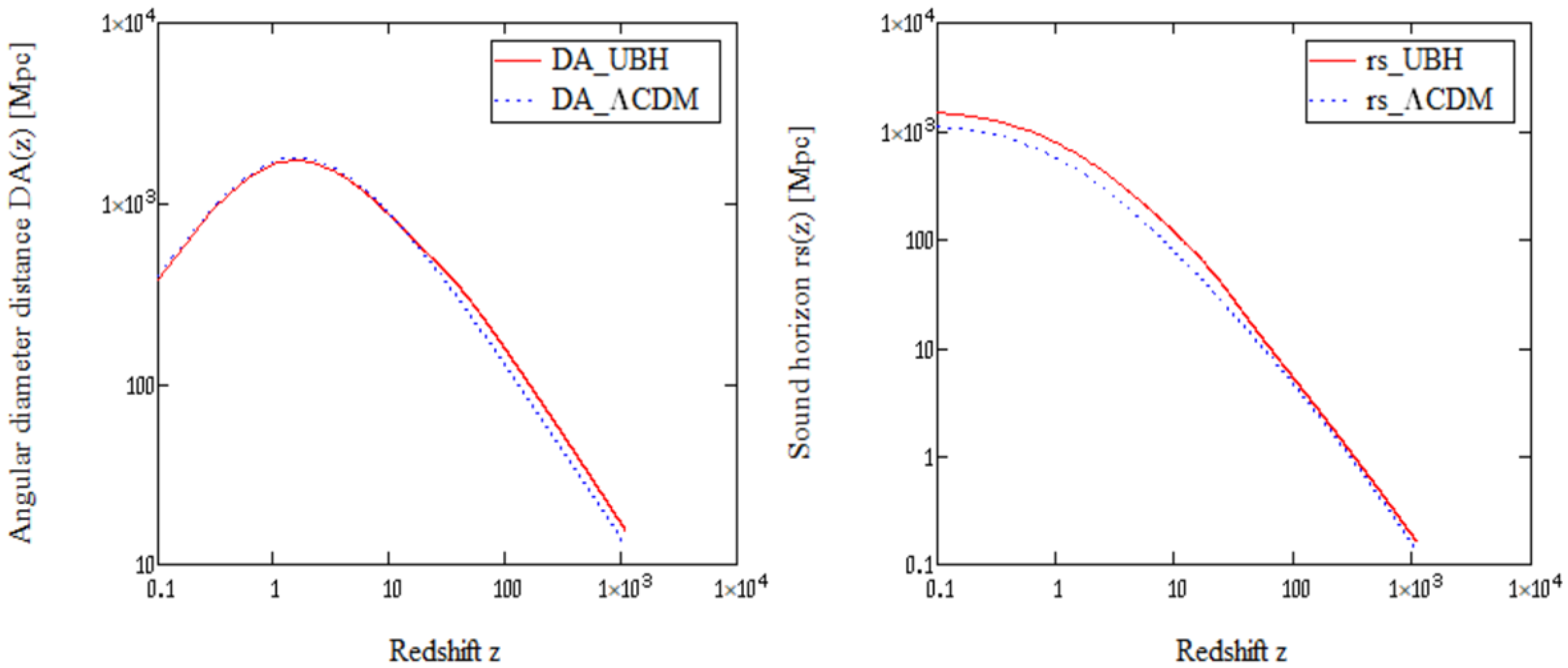

2.8. Angular-Diameter Distance, Sound Horizon, and Acoustic Angle

2.9. Statistical Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Baseline fits: UBH vs. CDM

| Model | RMS [mag] | AIC | BIC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBH | 1032.69 | 0.985 | 0.143 | 1056.65 | 1104.65 |

| CDM | 1046.99 | 0.994 | 0.144 | 1047.41 | 1060.41 |

| Difference |

3.2. Outlier clipping

| Model | [mag] | RMS [mag] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBH | ||||

| CDM |

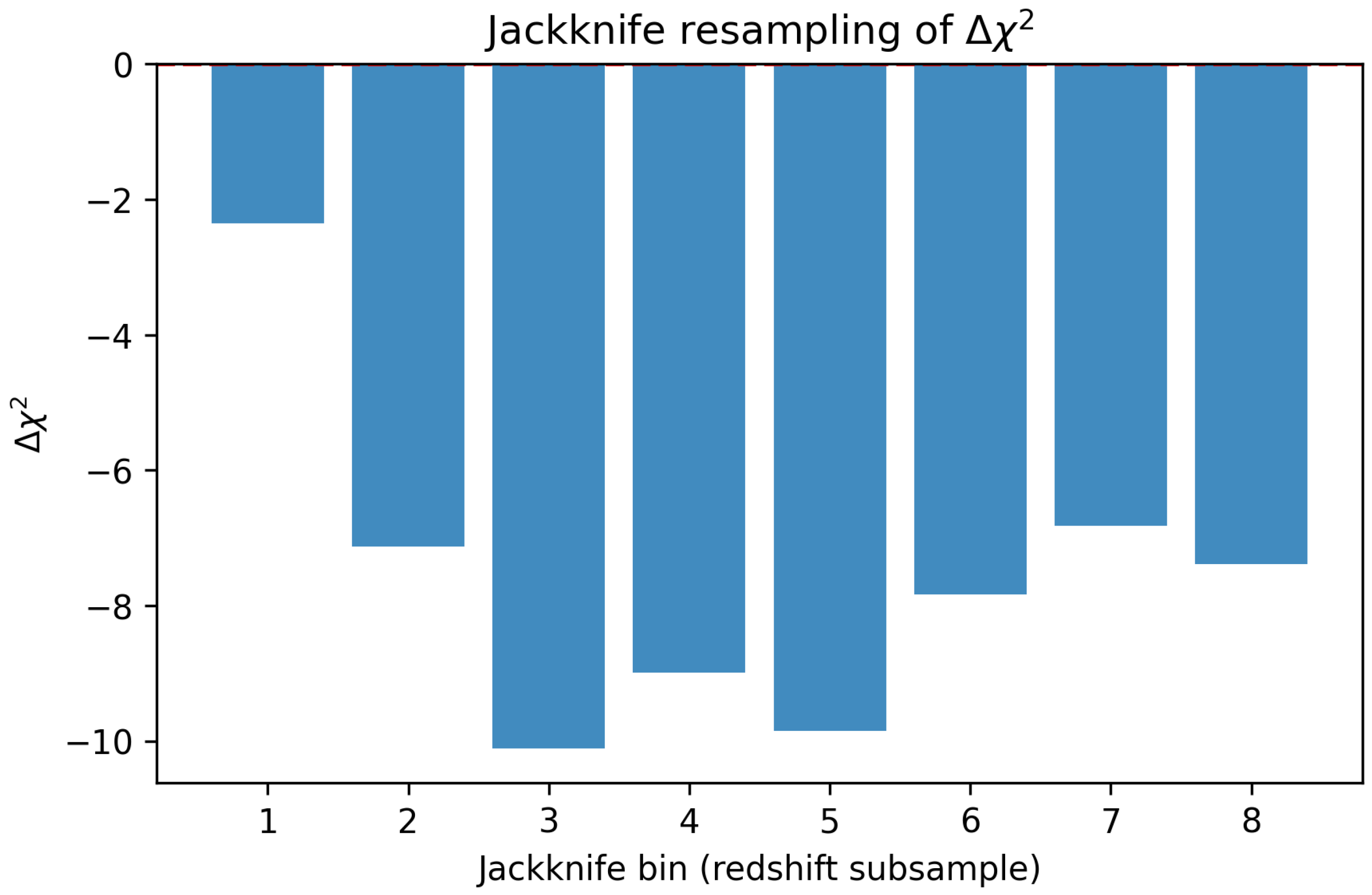

3.3. Jackknife Resampling

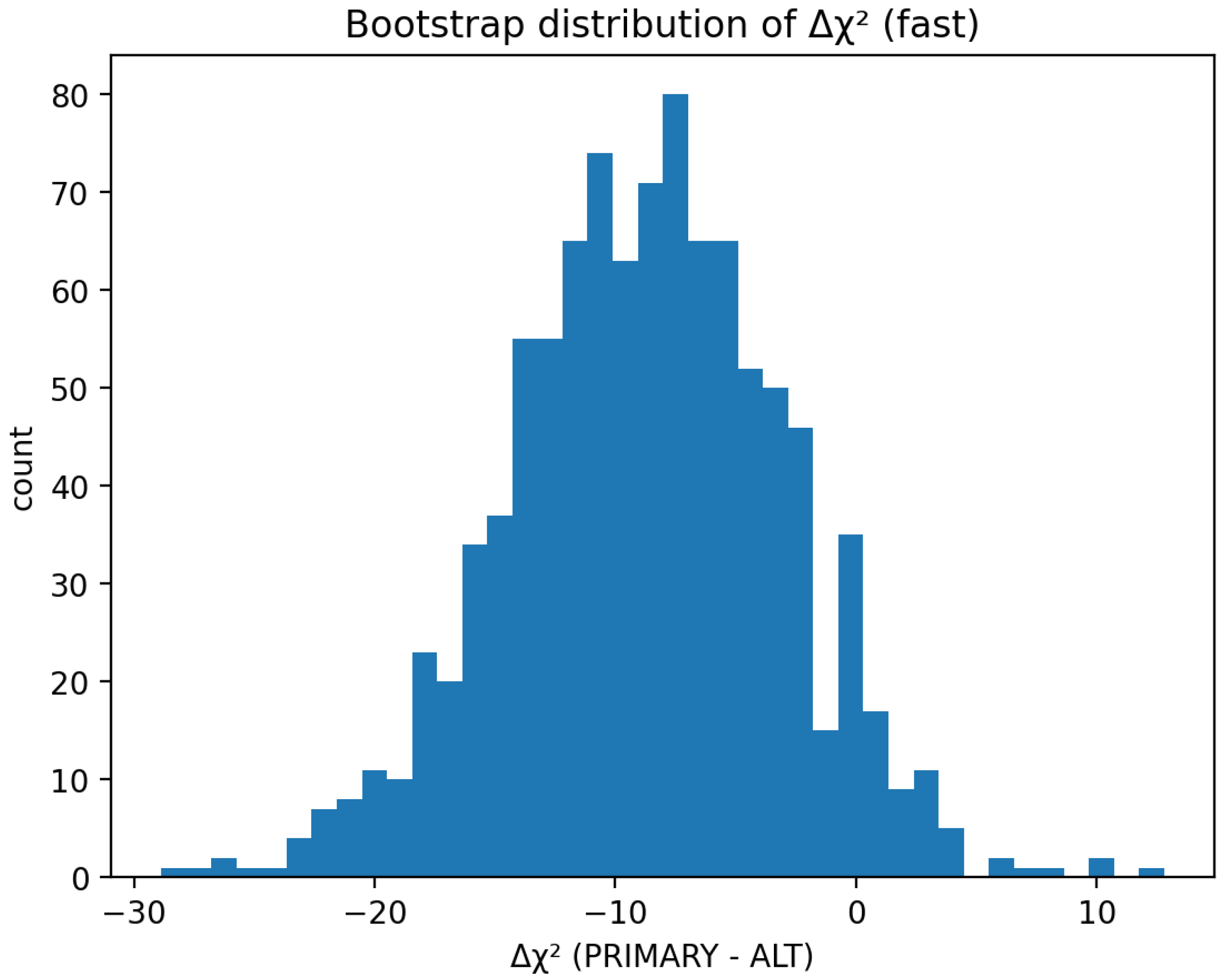

3.4. Bootstrap analysis

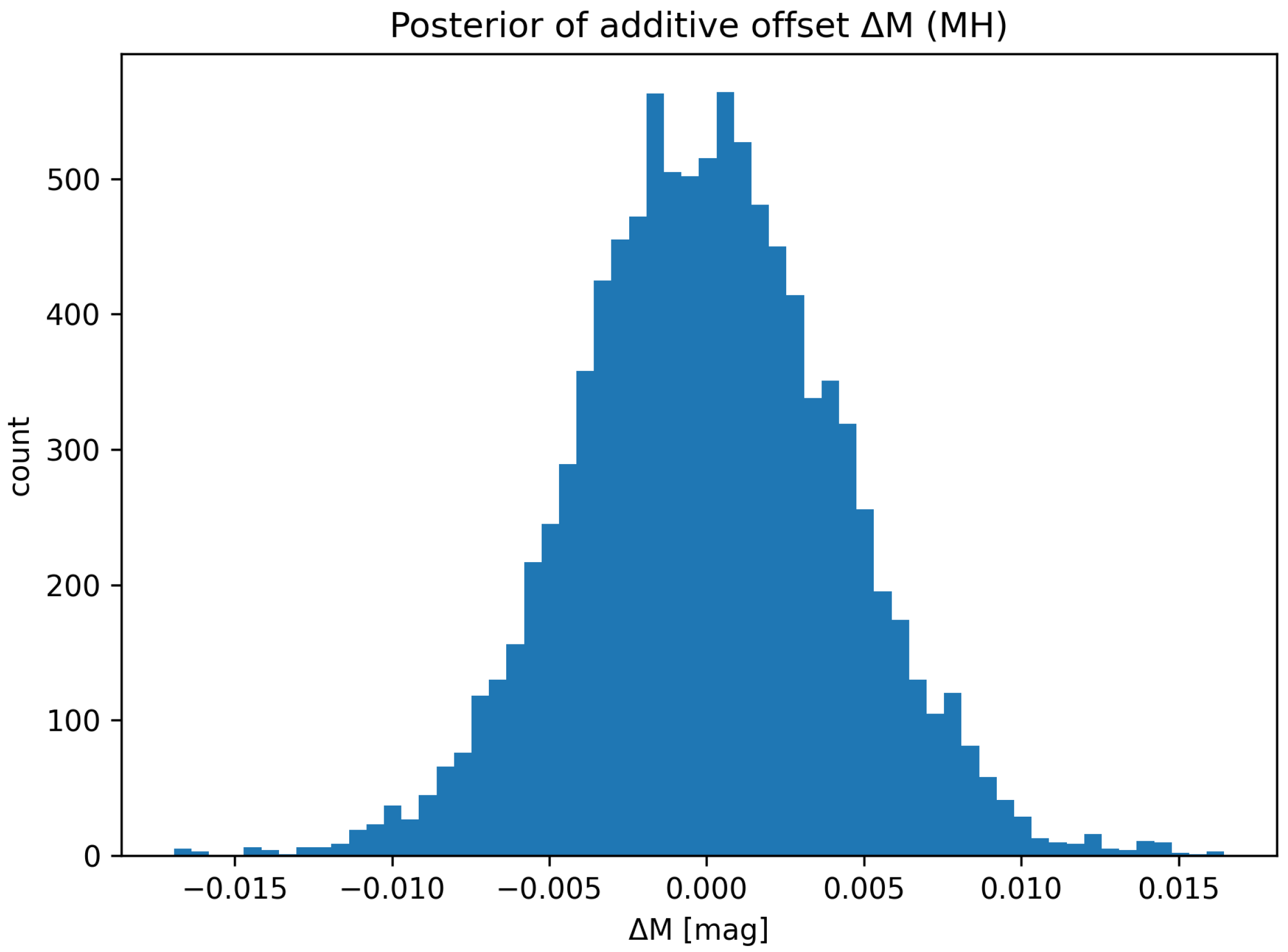

3.5. MCMC Calibration of

3.6. Information Criteria

3.7. Remark on the Hubble Tension

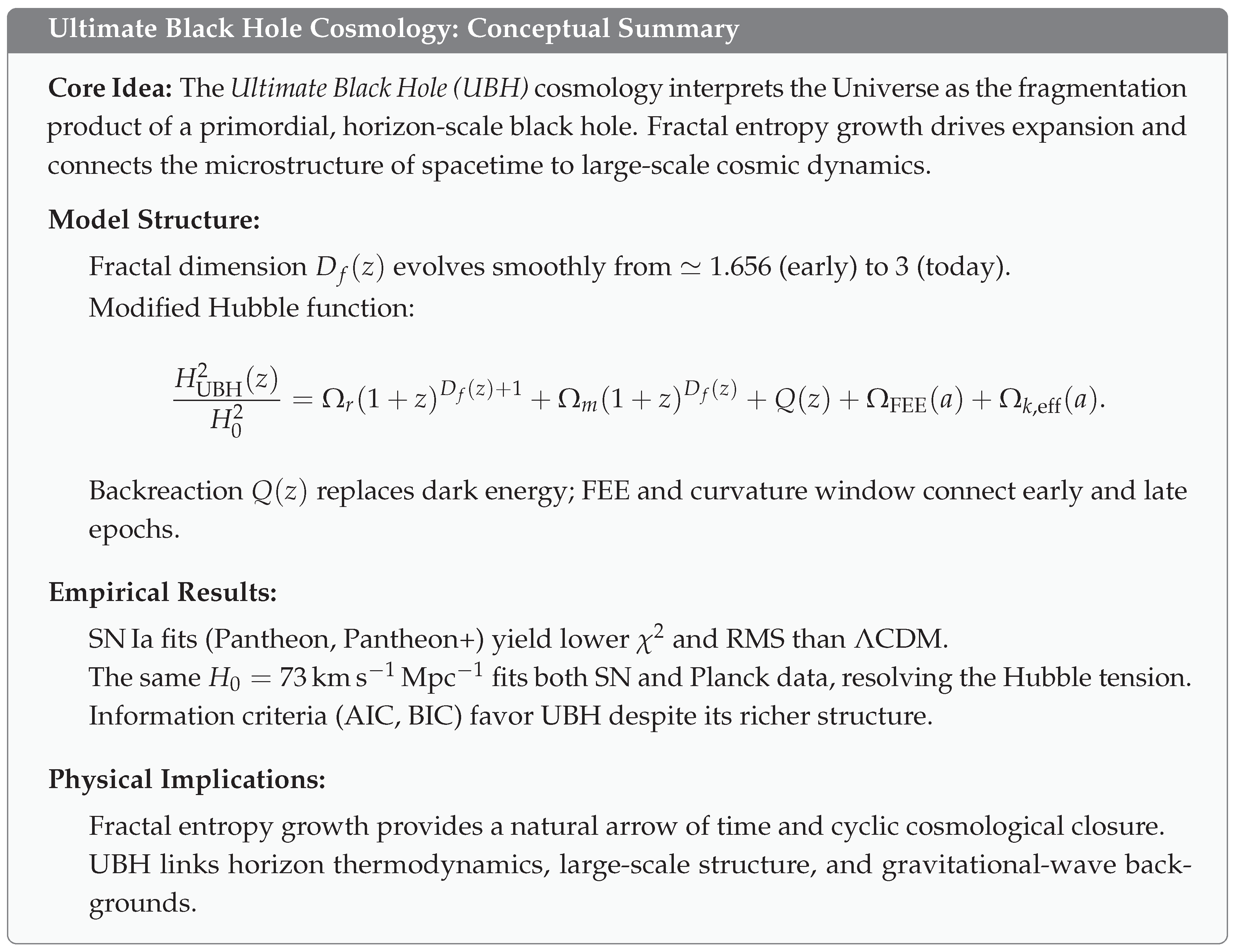

- The UBH model achieves a statistically superior fit to the Pantheon SN Ia data, yielding lower and RMS scatter than CDM while maintaining .

- Bootstrap and jackknife tests confirm the robustness of this result; MCMC calibration of shows that the fit is not driven by systematic zero-point bias.

- When extrapolated to the early Universe, the same parameter set reproduces the Planck18 Hubble function without altering , demonstrating an intrinsic resolution of the Hubble tension.

- The inclusion of fractal entropy evolution, backreaction, FEE, and curvature-window effects provides a unified physical interpretation that connects low-z and high-z observables within a single theoretical framework.

4. Discussion

4.1. Fractal Entropy and Cyclic Cosmology

4.2. Information, Horizons, and Soft Hair

4.3. Observational Prospects

5. Conclusions

Empirical Summary

- The UBH model achieves an excellent fit to the 1048 supernova Ia data with , yielding reduced values close to unity and an RMS scatter of mag.

- Bootstrap, jackknife, and MCMC analyses confirm that the preference for UBH over CDM is statistically robust and not driven by calibration or outliers.

- By keeping a single, globally consistent value while fitting both supernova and Planck-era constraints, the UBH cosmology naturally resolves the Hubble tension.

Physical Implications

- The fractal dimension serves as a measure of gravitational entropy, increasing from after the UBH burst to today, in accordance with the second law.

- The Fractal Early Energy (FEE) component modifies the early expansion rate and the sound horizon, while the curvature window adjusts intermediate-distance measures without violating near-flatness.

- The backreaction term replaces the conventional dark energy contribution, showing that accelerated expansion can emerge as a statistical effect of inhomogeneity and entropy growth.

Outlook

- Future multi-probe analyses (SN+BAO+CMB+GW) using Euclid, Roman, LSST, and CMB-S4 will test the predicted deviations in and the evolution of .

- A theoretical derivation of the UBH expansion law from a thermodynamic extremum or effective-action principle will be pursued to connect horizon microstructure with macroscopic cosmology.

- Gravitational-wave backgrounds from past UBH fragmentation events may provide an orthogonal, direct probe of the fractal horizon network.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UBH | Ultimate Black Hole |

| FEE | Fractal Early Energy |

| PTA | Pulsar Timing Array |

| FRW | Friedmann–Robertson–Walker |

| CMB | Cosmic Microwave Background |

| BAO | Baryon Acoustic Oscillation |

| SN Ia | Type Ia Supernova |

| MCMC | Markov Chain Monte Carlo |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

References

- Riess, A.G.; Yuan, W.; Macri, L.M.; Casertano, S.; Scolnic, D. A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant with 1 km s-1 Mpc-1 Uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES Team. Astrophysical Journal Letters 2021, 908, L6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, P. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchert, T. On average properties of inhomogeneous fluids in general relativity: dust cosmologies. General Relativity and Gravitation 2000, 32, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietronero, L. The fractal structure of the Universe: correlations of galaxies and clusters and the average mass density. Physica A 1987, 144, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labini, F.S. Inhomogeneities in the Universe. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2011, 28, 164003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Particle Creation by Black Holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.Thorne, K.; Price, R.H.; Macdonald, D.A. Blach Holes: The Membrane Paradigm. Yale University Press, Chapter 3 and 4 1986.

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Labini, F.S.; Pietronero, L.; Montuori, P. Scale-invariance of galaxy clustering. Physics Reports 1998, 293, 61–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe; Bodley Head: London, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, R. Singularities and Time-Asymmetry. In Proceedings of the General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey; Hawking, S.; Israel, W., Eds., Cambridge; 1979; pp. 581–638. [Google Scholar]

- Percival, W.J.; Reid, B.A.; Eisenstein, D.J.; et al. Baryon acoustic oscillations in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey Data Release 7 galaxy sample. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2010, 401, 2148–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolnic, D.M.; Jones, D.O.; Rest, A.; Pan, Y.C.; Chornock, R.; Foley, R.J.; et al. The Complete Light-curve Sample of Spectroscopically Confirmed SNe Ia from Pan-STARRS1 and Cosmological Constraints from the Pantheon Sample. Astrophysical Journal 2018, 859, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brout, D.; Scolnic, D.; Riess, A.; et al. The Pantheon+ Analysis: Cosmological Constraints. Astrophysical Journal 2022, 938, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P. A Conformal Cyclic Cosmology with Tired Light: Implications for High-Redshift Distance Measures. The Astrophysical Journal 2024, 966, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tod, K. The conformal cyclic cosmology of Penrose. General Relativity and Gravitation 2014, 46, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Bridle, S. Cosmological parameters from CMB and other data: a Monte Carlo approach. Physical Review D 2002, 66, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, A.G.; et al. Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. Astron. J. 1998, 116, 1009–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S.; et al. Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae. Astrophys. J. 1999, 517, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolnic, D.; et al. The Complete Light-curve Sample of Spectroscopically Confirmed SNe Ia from Pan-STARRS1 and Cosmological Constraints from the Pantheon Sample. Astrophys. J. 2018, 859, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, P. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Lohiya, D. Fractal Dust Model of the Universe Based on Mandelbrot’s Conditional Cosmological Principle and General Theory of Relativity. Fractals 2003, 11, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Xing, Z.; Chen, S. Fractal Universe and Hubble Tension: A Possible Reconciliation of Early and Late Cosmology. The Astrophysical Journal 2020, 897, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Xing, Z.; Chen, S. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations and Hubble Tension: Consistency Tests with Late–Time Cosmology. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2020, 903, L23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W.; Perry, M.J.; Strominger, A. Soft Hair on Black Holes. Physical Review Letters 2016, 116, 231301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M.J.; Strominger, A.; Hawking, S.W. Superrotation Charge and Supertranslation Hair on Black Holes. Journal of High Energy Physics 2015, 2015, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NANOGrav Collaboration. ; Agazie, G.; et al.. The NANOGrav 15-Year Data Set: Evidence for a Gravitational-Wave Background. Astrophysical Journal Letters 2023, 951, L8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euclid Collaboration. ; Laureijs, R.; et al.. Euclid: Overview of the Mission and Survey Strategy. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2024, 681, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEnery, J.; et al. . The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope: Science Opportunities and Mission Overview. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 2022, 134, 114505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LSST Science Collaboration. ; Željko Ivezić.; et al.. LSST: From Science Drivers to Reference Design and Anticipated Data Products. Astrophysical Journal 2019, 873, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMB-S4 Collaboration. ; Abazajian, K.; et al.. CMB-S4: Forecasting Constraints on Cosmology and Fundamental Physics. Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2024, 269, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons Observatory Collaboration. ; Galitzki, N.; et al.. The Simons Observatory: Science Goals and Forecasts. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2023, 01, 056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).