Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Strain

2.2. Medium and Strain Culture

2.3. Monascus Pigments Production Under Salt Stress

2.4. Analysis of Monascus flavor with GC-IMS

2.5. Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

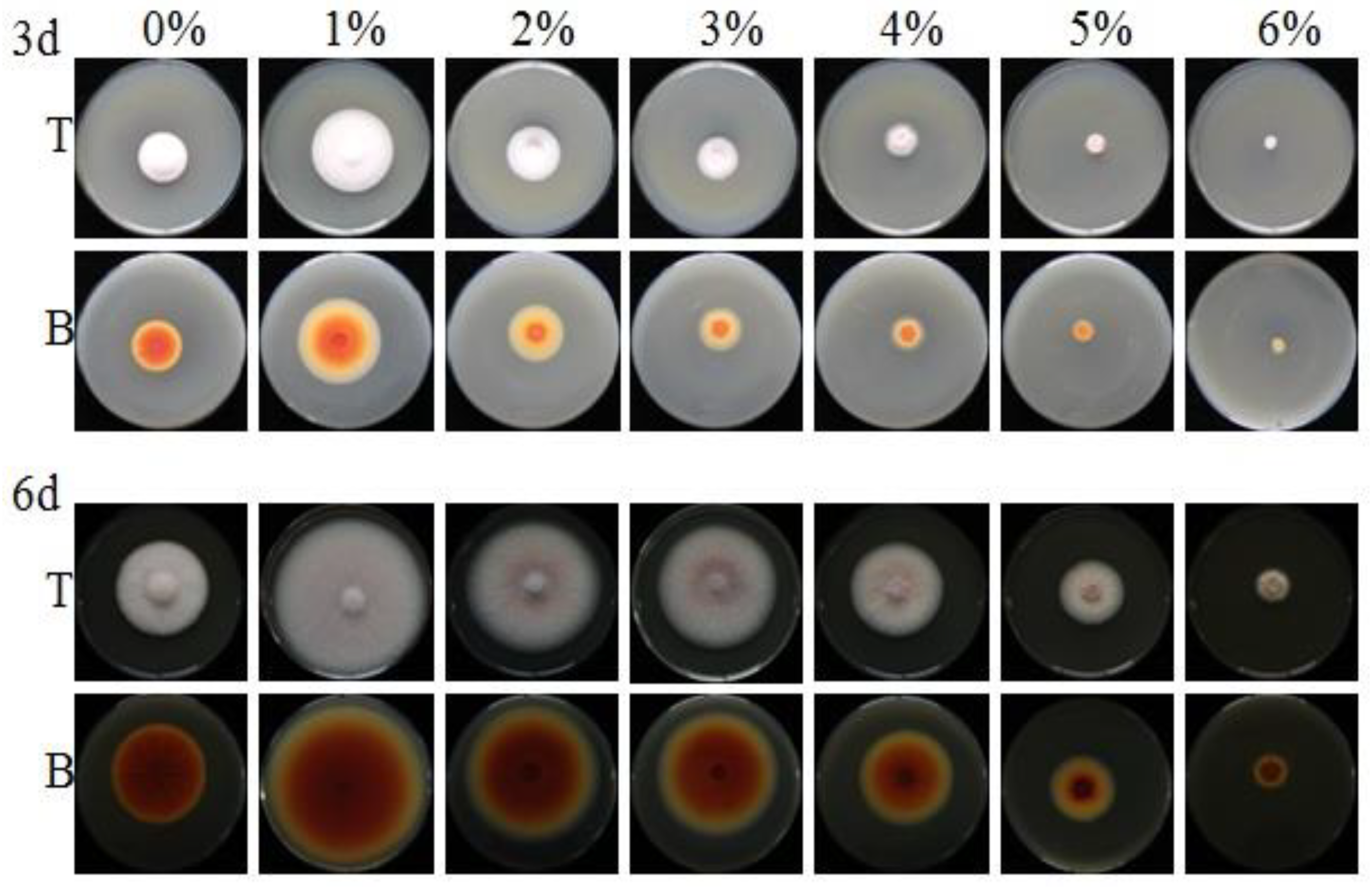

3.1. Effect of NaCl on the Growth in M. ruber CICC41233

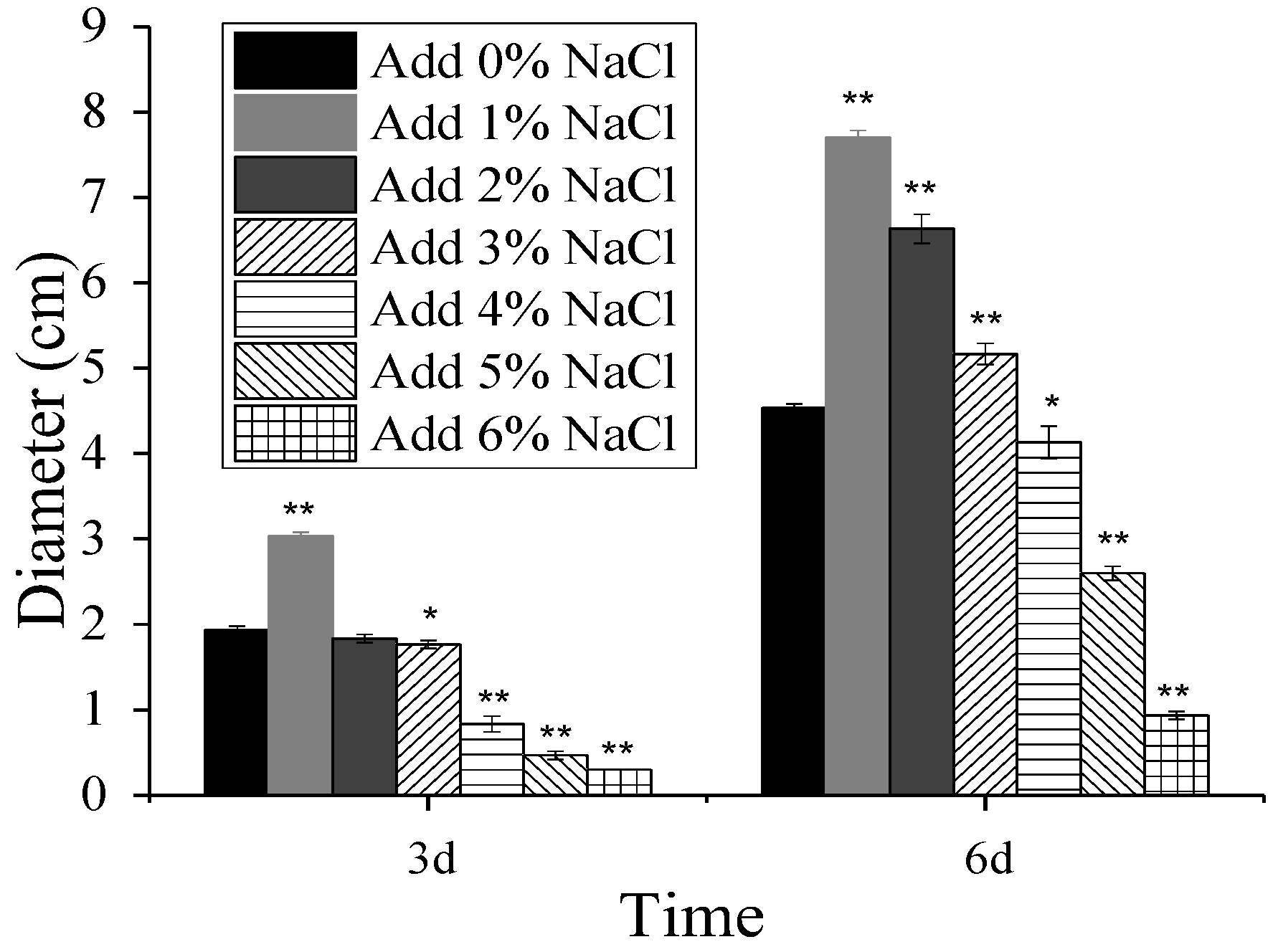

3.2. Effect of NaCl on Monascus Pigment Production

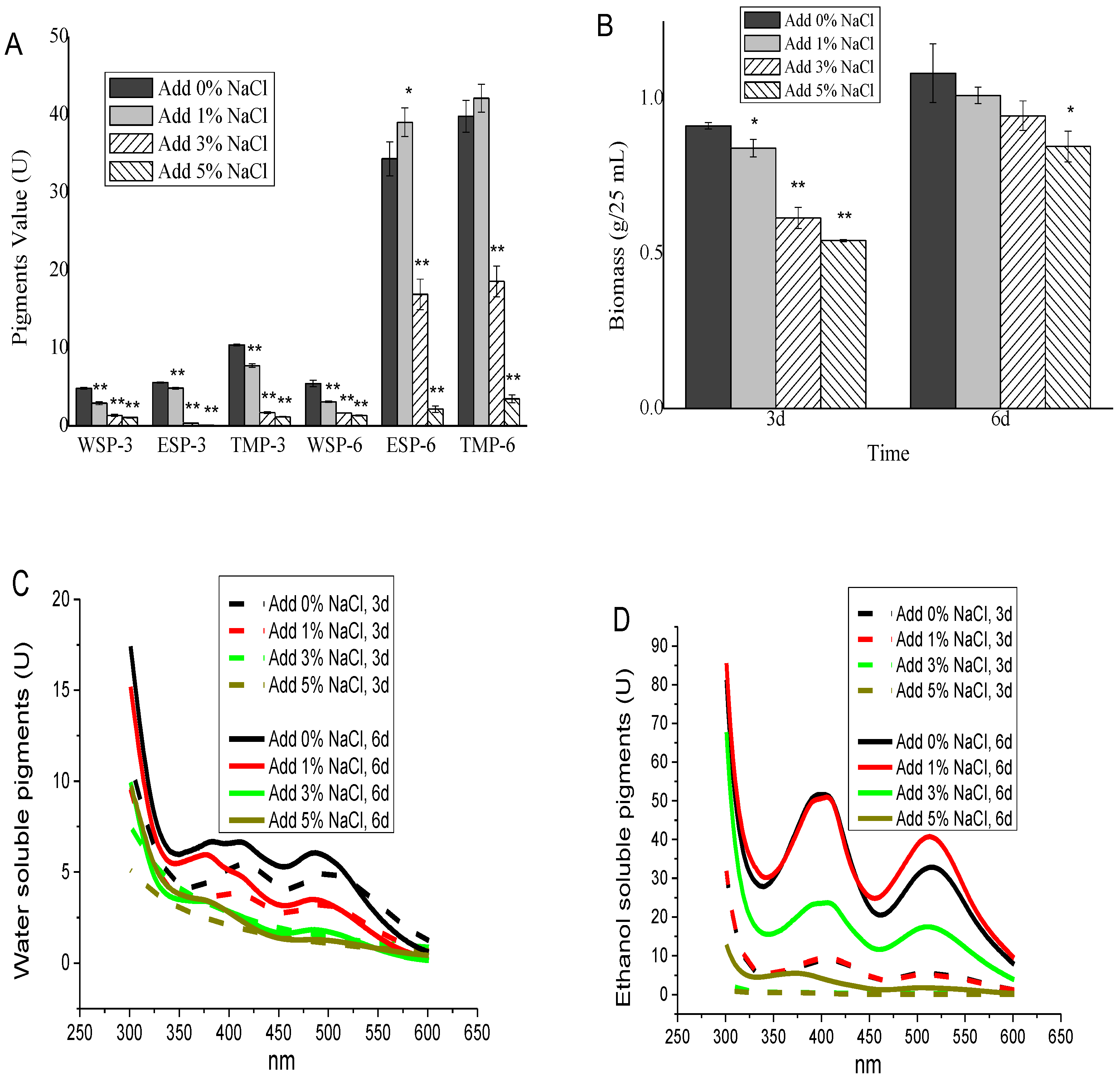

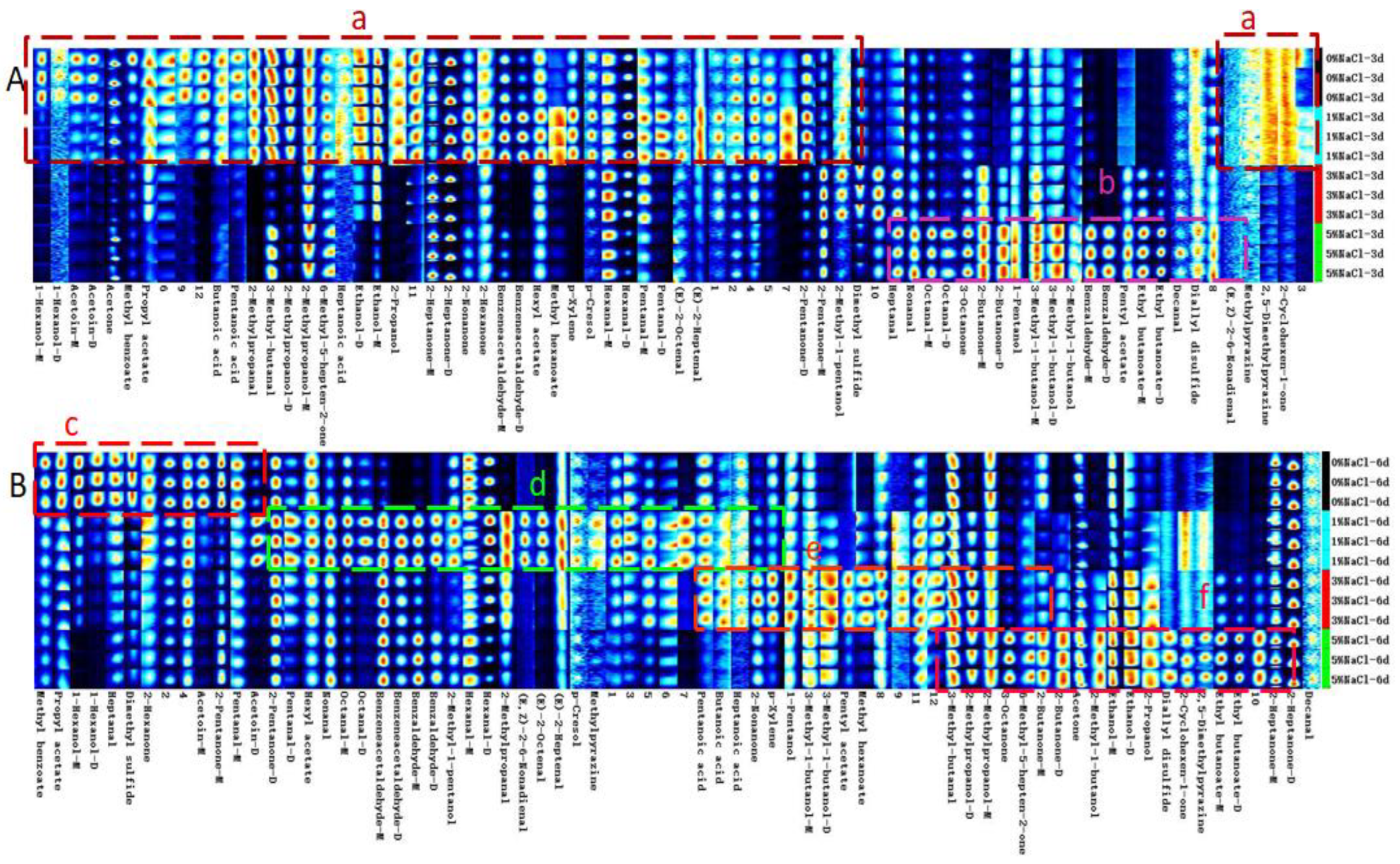

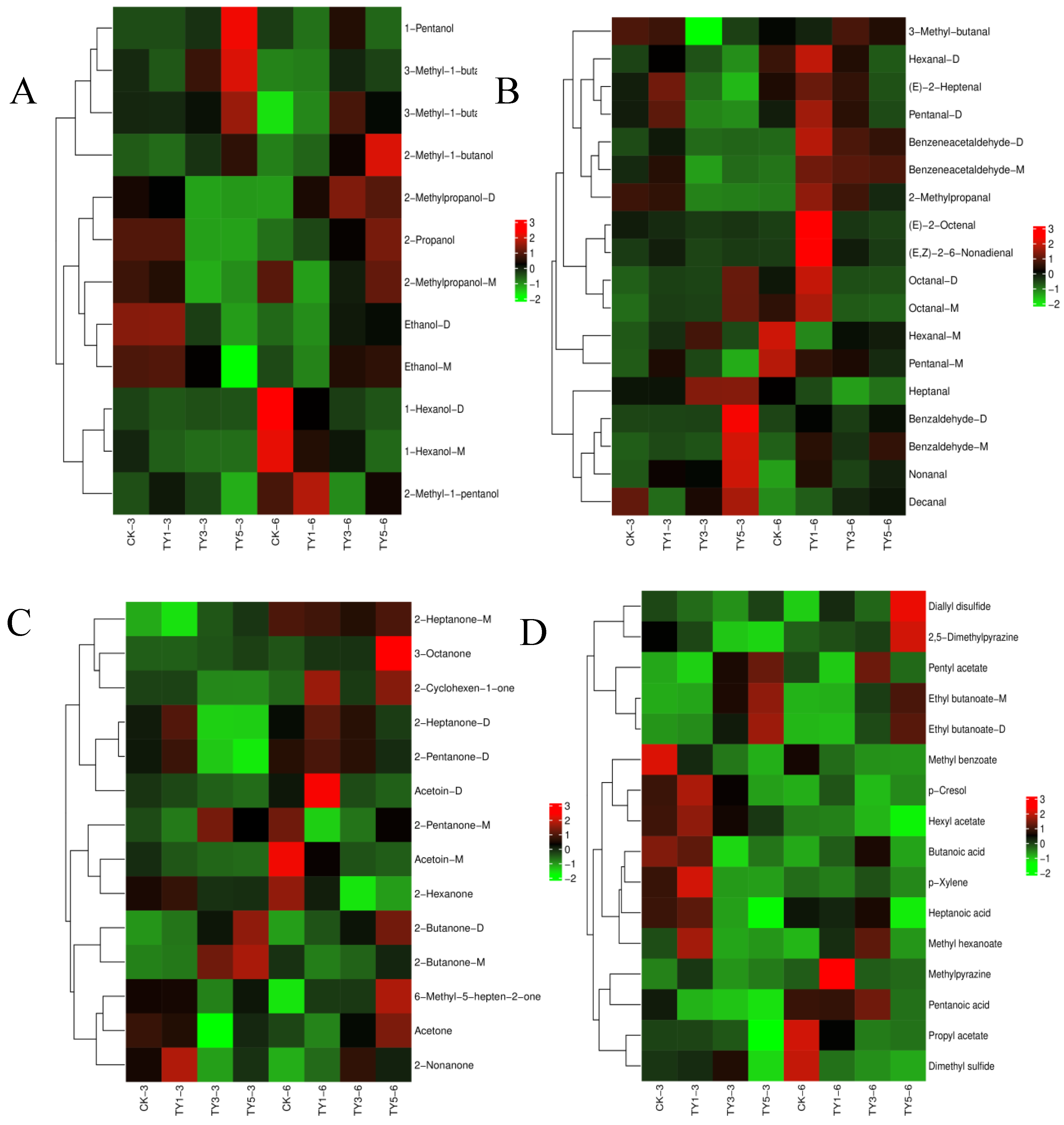

3.3. Effect of NaCl on Monascus Flavor Fingerprint

3.4. Transcriptomic Insights into the Metabolic Regulation of M. ruber Cultivated on Solid Substrate

3.5. Transcriptomic Insights into the Monascus Pigment Fermentation and Monascus flavor of M. ruber

3.6. Monascus Pigment Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Expression Under Salt Condition in M. ruber CICC41233

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, W.P.; Chen, R.F.; Liu, Q.P.; He, Y.; He, K.; Ding, X.L.; Kang, L.J.; Guo, X.X.; Xie, N.N.; Zhou, Y.X.; Lu, Y.Y.; Cox, R.J.; Molnár, I.; Li, M.; Shao, Y.C.; Chen, F.S. Orange, red, yellow: biosynthesis of azaphilone pigments in Monascus fungi. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 4917–4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xue, D. Enhancement of antioxidant activity of Radix Puerariae and red yeast rice by mixed fermentation with Monascus purpureus. Food Chem. 2017, 226, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Oyervides, L.; Ruiz-Sánchez, J. P.; Oliveira, J. C.; Sousa-Gallagher, M. J.; Méndez-Zavala, A.; Giuffrida, D.; Dufossé, L.; Montañez, J. Biotechnological approaches for the production of natural colorants by Talaromyces/Penicillium: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 43, 107601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.P.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y.X.; Shao, Y.C.; Feng, Y.L.; Li, M.; Chen, F.S. Edible Filamentous Fungi from the Species Monascus: Early Traditional Fermentations, Modern Molecular Biology, and Future Genomics. Compr Rev Food Sci F. 2015, 14, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farawahida, A.H.; Palmer, J.; Flint, S. The relationship between pH, pigments production, and citrinin synthesis by Monascus purpureus during red fermented rice fermentation. Food Biosci. 2025, 71, 107034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagou, E. Z.; Skandamis, P. N.; Nychas, G. J. Modelling the combined effect of temperature, pH and aw on the growth rate of Monascus ruber, a heat-resistant fungus isolated from green table olives. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 94, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. H.; Zhang, B. B.; Lu, L. P.; Huang, Y.; Xu. G. R. Enhanced production of pigments by addition of surfactants in submerged fermentation of Monascus purpureus H1102. J. Sci. Food Agr. 2013, 93, 3339–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Ma, Y.F.; Tian, Y.; Li, J. B.; Zhong, H. Y. Quantitative proteomics analysis by sequential window acquisition of all theoretical mass spectra–mass spectrometry reveals inhibition mechanism of pigments and citrinin production of Monascus response to high ammonium chloride concentration. J.Agr. Food Chem. 2019, 68, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J. L.; Wu, L.; Lu, J. Q.; Zhou, W. B.; Cao, Y. J.; Lv, W. L.; Liu, B.; Rao, P. F.; Ni, L.; Lv, X. C. Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals the regulatory effects of inorganic nitrogen on the biosynthesis of Monascus pigments and citrinin. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 5268–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, W.; Wu, X.; Li, W.; Cui, J.; Long, C. Transcriptome analysis revealed the molecular mechanism of acetic acid increasing Monascus pigment production in Monascus ruber CICC41233. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Tang, R.; Tian, X. F.; Qin, P.; Wu, Z. Q. Change of Monascus pigment metabolism and secretion in different extractive fermentation process. Bioproc. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 40, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Wang, M. H.; Shi, K.; Chen, G.; Tian, X. F.; Wu, Z. Q. Metabolism and secretion of yellow pigment under high glucose stress with Monascus ruber. AMB Express 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samapundo, S.; Deschuyffeleer, N.; Van Laere, D.; De Leyn, I.; Devlieghere, F. Effect of NaCl reduction and replacement on the growth of fungi important to the spoilage of bread. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendruscolo, F.; Bühler, R. M. M.; de Carvalho, J. C.; de Oliveira, D.; Moritz, D. E.; Schmidell, W.; Ninow, J. L. Monascus: a reality on the production and application of microbial pigments. Appl. Biochem. Biotech. 2016, 178, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Gu, T.; Wang, J.; Gao, M. Evaluation of differences in volatile flavor compounds between liquid-state and solid-state fermented Tartary buckwheat by Monascus purpureus. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C. N.; Liu, M. M.; Chen, X.; Wang, X. F.; Ai, M. Q.; Cui, J. J.; Zeng, B. The acyl-CoA binding protein affects Monascus pigment production in Monascus ruber CICC41233. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, K.; Song, D.; Chen, G.; Pistolozzi, M.; Wu, Z. Q.; Quan, L. Controlling composition and color characteristics of Monascus pigments by pH and nitrogen sources in submerged fermentation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2015, 120, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yang, S. Z.; Wang, C. T.; Shi, K.; Zhao, X. H.; Wu, Z. Q. Investigation of the mycelial morphology of Monascus and the expression of pigment biosynthetic genes in high-salt-stress fermentation. Appl. Microbiol, Biot. 2020, 104, 2469–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z. X.; Xiong, X. Q.; Liu, Y. B.; Zhang, J. L.; Wang, S. J.; Li, L.; Gao, M. X. NaCl inhibits citrinin and stimulates Monascus pigments and monacolin K production. Toxins 2019, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rühl, J.; Hein, E.-M.; Hayen, H.; Schmid, A.; Blank, L.M. The Glycerophospholipid Inventory of Pseudomonas putida Is Conserved between Strains and Enables Growth Condition-Related Alterations. Microb. Biotechnol. 2012, 5, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xia, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Xu, P.; Li, X.; Bai, L.; Zhou, X.L.; Xue, M. Lysophospholipid Acyltransferase-Mediated Formation of Saturated Glycerophospholipids Maintained Cell Membrane Integrity for Hypoxic Adaptation. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 3191–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzin, V.; Galili, G. New Insights into the Shikimate and Aromatic Amino Acids Biosynthesis Pathways in Plants. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 956–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Huang, B.; Jia, R. Diverse Effects of Amino Acids on Monascus Pigments Biosynthesis in Monascus purpureus. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 15, 13–951266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.P.; Shen, J.S.; Zhang, L.Q.; Zou, X.H.; Jin, L. Metabolomic and transcriptomic integration reveals the mechanism of aroma formation as strawberries naturally turn colors while ripening. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.P.; Zhang, L.N.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Xun, Z.L.; Dai, X.; Zhao, Q.F. Integrated Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Insights into Flavor-Related Metabolism in Grape Berries Across Cultivars and Developmental Stages. Metabolites 2025, 15, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shao, F.H.; Cao, J.; He, Y.F.; Zhang, L.T.; Zhang, B.; Jun, S.J.; Febrisiantosa, A.; Feng, A.G.; Yang, J.; Zhu, L.L.; Li, C. Multi-omics integration deciphered microbial and metabolite dynamics during flavor development of rapidly fermented golden pompano. Food Biosci. 2025, 73, 107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, F.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y. Formation of Aroma Active Volatiles from Thermal Degradation of 18 Amino Acids with or without Sugars in Low-Moisture Systems and the Modulation by Sucrose and Epigallocatechin Gallate. Food Res. Int. 2025, 194, 114686. [Google Scholar]

- Hajjaj, H.; François, J. M.; Goma, G.; Blanc, P. J. Effect of amino acids on red pigments and citrinin production in Monascus ruber. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, B.; Karki, S.; Chiu, S. H.; Kim, H. J.; Suh, J. W.; Nam, B.; Yoon, Y. M.; Chen, C. C.; Kwon, H. J. Genetic localization and in vivo characterization of a Monascus azaphilone pigment biosynthetic gene cluster. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2013, 97, 6337–6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample* | Alcohol | Aldehyde | Ketone | Ester | Acid | Pyrazine | Others |

| CK-Y3 | 21.30% | 33.34% | 41.63% | 1.92% | 0.36% | 0.09% | 1.35% |

| TY1-3 | 18.78% | 33.73% | 43.64% | 1.90% | 0.29% | 0.08% | 1.59% |

| TY3-3 | 25.71% | 17.73% | 51.28% | 3.36% | 0.32% | 0.12% | 1.47% |

| TY5-3 | 15.96% | 29.80% | 50.07% | 2.93% | 0.26% | 0.10% | 0.87% |

| CK-Y6 | 16.59% | 26.63% | 52.87% | 2.15% | 0.38% | 0.10% | 1.28% |

| TY1-6 | 11.38% | 44.00% | 42.22% | 1.32% | 0.27% | 0.09% | 0.71% |

| TY3-6 | 18.64% | 36.44% | 42.10% | 1.66% | 0.33% | 0.08% | 0.74% |

| TY5-6 | 20.84% | 31.17% | 45.18% | 1.68% | 0.20% | 0.11% | 0.82% |

| DEG Set* | DEG Number | Up-regulated | Down-regulated |

| CK-G3 vs TG1-3 | 199 | 99 | 100 |

| CK-G3 vs TG5-3 | 1351 | 336 | 1015 |

| CK-G6 vs TG1-6 | 356 | 172 | 184 |

| CK-G6 vs TG5-6 | 1319 | 315 | 1004 |

| CK-G3 vs CK-G6 | 623 | 523 | 100 |

| TG1-3 vs TG1-6 | 633 | 522 | 111 |

| TG5-3 vs TG5-6 | 696 | 581 | 115 |

| CK-Y3 vs TY1-3 | 1078 | 662 | 416 |

| CK-Y3 vs TY5-3 | 2873 | 1749 | 1124 |

| CK-Y6 vs TY1-6 | 3681 | 3264 | 417 |

| CK-Y6 vs TY5-6 | 3530 | 2426 | 1104 |

| CK-Y3 vs CK-Y6 | 2755 | 1510 | 1245 |

| TY1-3 vs TY1-6 | 4451 | 3340 | 1111 |

| TY5-3 vs TY5-6 | 2757 | 1784 | 973 |

| DEG Set | Pathway ID | KEGG Pathway | Number of Genes | p-value |

qvalue |

| CK-G3 vs TG1-3 | ko00785 | Lipoic acid metabolism | 1 | 0.020172 | 0.259847 |

| ko00564 | Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 2 | 0.046493 | 0.259847 | |

| CK-G3 vs TG5-3 | ko00380 | Tryptophan metabolism | 14 | 0.000009 |

0.000321 |

| ko00360 | Phenylalanine metabolism | 12 | 0.000011 | 0.000321 | |

| ko00620 | Pyruvate metabolism | 12 | 0.000088 | 0.001917 | |

| ko00350 | Tyrosine metabolism | 9 | 0.001026 | 0.017855 | |

| ko00500 | Starch and sucrose metabolism | 10 | 0.003144 | 0.045581 | |

| CK-G6 vs TG1-6 | ko00564 | Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 5 | 0.005180 | 0.126913 |

| ko00592 | alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism | 2 | 0.015765 | 0.229069 | |

| ko00052 | Galactose metabolism | 3 | 0.018699 | 0.229069 | |

| ko00591 | Linoleic acid metabolism | 1 | 0.043982 | 0.359187 | |

| CK-G6 vs TG5-6 | ko00360 | Phenylalanine metabolism | 10 | 0.000878 | 0.039661 |

| ko00520 | Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 12 | 0.001293 | 0.039661 | |

| ko00380 | Tryptophan metabolism | 11 | 0.002274 | 0.043861 | |

| ko00350 | Tyrosine metabolism | 9 | 0.002384 | 0.043861 | |

| CK-G3 vs CK-G6 | ko00520 | Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 8 | 0.000287 | 0.008184 |

| ko00500 | Starch and sucrose metabolism | 7 | 0.001016 | 0.019304 | |

| ko01212 | Fatty acid metabolism | 5 | 0.004113 | 0.046890 | |

| TG1-3 vs TG1-6 | ko00590 | Arachidonic acid metabolism | 3 | 0.000233 | 0.005547 |

| ko00592 | alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism | 4 | 0.000248 | 0.005547 | |

| ko00591 | Linoleic acid metabolism | 2 | 0.001552 | 0.023848 | |

| ko00561 | Glycerolipid metabolism | 6 | 0.001780 | 0.023848 | |

| ko00430 | Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism | 3 | 0.002910 | 0.031995 | |

| ko00500 | Starch and sucrose metabolism | 7 | 0.003343 | 0.031995 | |

| TG5-3 vs TG5-6 | ko00130 | Ubiquinone and other terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis | 5 | 0.000428 | 0.014330 |

| DEG Set | Pathway ID | KEGG Pathway | Number of Genes | p-value |

qvalue |

| CK-Y3 vs TY1-3 | ko01210 | 2-Oxocarboxylic acid metabolism | 11 | 0.000604 | 0.018919 |

| ko00010 | Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis | 13 | 0.000772 | 0.018919 | |

| ko01230 | Biosynthesis of amino acids | 22 | 0.001241 | 0.024325 | |

| ko00300 | Lysine biosynthesis | 5 | 0.003003 | 0.049051 | |

| CK-Y3 vs TY5-3 | ko00190 | Oxidative phosphorylation | 40 | 0.000000 | 0.000010 |

| ko00280 | Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation | 25 | 0.000146 | 0.003450 | |

| ko00310 | Lysine degradation | 21 | 0.000154 | 0.003450 | |

| ko00071 | Fatty acid degradation | 20 | 0.000175 | 0.003450 | |

| ko00380 | Tryptophan metabolism | 26 | 0.001690 | 0.024933 | |

| CK-Y6 vs TY1-6 | ko00360 | Phenylalanine metabolism | 28 | 0.000006 | 0.000459 |

| ko00380 | Tryptophan metabolism | 34 | 0.000008 | 0.000459 | |

| ko00330 | Arginine and proline metabolism | 34 | 0.000857 | 0.022708 | |

| CK-Y6 vs TY5-6 | ko00270 | Cysteine and methionine metabolism | 31 | 0.000851 |

0.021275 |

| ko00260 | Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | 36 | 0.002722 |

0.049153 | |

| ko00620 | Pyruvate metabolism | 28 | 0.003539 | 0.049153 |

|

| CK-Y3 vs CK-Y6 | ko01212 | Fatty acid metabolism | 20 | 0.000155 | 0.004560 |

| ko00010 | Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis | 28 | 0.000756 | 0.014868 | |

| ko00380 | Tryptophan metabolism | 25 | 0.001093 | 0.018430 | |

| ko00310 | Lysine degradation | 18 | 0.001823 | 0.026888 | |

| ko00071 | Fatty acid degradation | 17 | 0.002322 | 0.030442 | |

| ko00520 | Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 25 | 0.004086 | 0.040182 | |

| TY1-Y3 vs TY1-6 | ko01212 | Fatty acid metabolism |

27 | 0.000087 | 0.003112 |

| ko00010 | Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis | 41 | 0.000154 | 0.003843 | |

| ko00260 | Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | 42 | 0.000934 | 0.013805 | |

| ko00350 | Tyrosine metabolism | 27 | 0.000982 | 0.013805 | |

| ko00071 | Fatty acid degradation | 24 | 0.000994 | 0.013805 | |

| ko00280 | Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation | 30 | 0.001707 | 0.021336 | |

| ko00360 | Phenylalanine metabolism | 27 | 0.003465 | 0.039377 | |

| TY5-Y3 vs TY5-6 | ko03008 | Ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes | 41 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| ko03020 | RNA polymerase | 17 | 0.000011 | 0.000654 |

| NO. | M. ruber PKS cluster | CK-Y3 | TY1-3 | TY5-3 | CK-Y6 | TY1-6 | TY5-6 |

| 1 | Contig6.564 | 3.59 | 4.29 | 3.67 | 4.16 | 15.92 | 4.33 |

| 2 | Contig6.565 | 18.95 |

18.04 |

89.2 |

88.74 |

241.36 |

34.06 |

| 3 | Contig6.566 | 388.7 |

555.47 |

234.37 |

0.76 |

↑2.88 |

↑149.04 |

| 4 | Contig1.632 | 5.4 |

6.17 |

5.9 |

5.81 |

10.96 |

7.92 |

| 5 | Contig6.567 | 698.17 |

1160.71 |

↓202.36 |

1.64 |

3.46 |

↑208.39 |

| 6 | Contig3.926 | 2.34 |

↓1.06 |

↑17.03 |

3.3 |

6.35 |

↓1.55 |

| 7 | Contig9.114 | 84.13 |

↓33.53 |

64.54 |

30.13 |

56.12 |

31.84 |

| 8 | Contig6.568 | 7870.3 |

↑16165. 92 |

3023.02 |

10.64 |

12.76 |

↑4851. 14 |

| 9 | Contig6.569 | 493.42 |

838.2 |

700.63 |

30.01 |

40.42 |

↑340.48 |

| 10 | Contig8.37 | 0.24 |

↑0.71 |

↑0.48 |

0.58 |

↑2.21 |

↑1.67 |

| 11 | Contig6.571 | 2587.31 |

1896.89 |

↓176.57 |

1005.73 |

1101.42 |

↓334.17 |

| 12 | Contig6.572 | 3028.21 |

2036.55 |

↓359.36 |

1632.78 |

2079.7 |

↓623.97 |

| 13 | Contig9.526 | 59.75 |

45.12 |

90.99 |

222.59 |

238.44 |

145.63 |

| 14 | Contig6.573 | 182.56 |

283.66 |

142.07 |

2.04 |

3.32 |

↑90.62 |

| 15 | Contig5.231 | 10.96 |

9.99 |

9.43 |

16.58 |

29.98 |

15.8 |

| 16 | Contig6.574 | 2.95 |

5.77 |

2.68 |

0.8 |

3.52 |

1.97 |

| 17 | Contig1.420 | 37.69 |

55.92 |

154.97 |

27.63 |

31.07 |

70.48 |

| 18 | Contig6.575 | 3.31 |

2.72 |

3.04 |

2.68 |

5.92 |

3.19 |

| 19 | Contig6.576 | 1.03 |

0.34 |

1.03 |

0.89 |

1.36 |

0.88 |

| 20 | Contig2.99 | 2.4 |

2.17 |

1.84 |

2.32 |

5.67 |

2.66 |

| 21 | Contig6.578 | 11.92 |

7.85 |

10.68 |

5.62 |

10.93 |

3.04 |

| 22 | Contig6.579 | 585.88 |

507.92 |

↓219.4 |

0.67 |

↑1.58 |

↑165.35 |

| 23 | Contig6.580 | 2455.46 |

↑4927.89 |

↓718.85 |

2.02 |

↑4.69 |

↑814.05 |

| 24 | Contig6.581 | 863.66 |

1561.22 |

885.15 |

5.57 |

8.95 |

↑579.8 |

| 25 | Contig6.582 | 1142.83 |

1053.13 |

↓245.26 |

241.3 |

348.49 |

298.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).