Submitted:

30 October 2023

Posted:

31 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Fungal strains and culture conditions

2.2. Constructs for LeuRS knockdown and fungal transformation

2.3. Transcriptome sequencing and data analysis

2.4. UHPLC-Q-TOF/MS of metabolites and data analysis

2.5. Statistical analysis

2.6. Accession number(s)

3. Results

3.1. LeuRS influences mycelial growth, cleistothecium formation, and stress tolerance of A. montevidensis

3.2. Transcriptome profiles of the LeuRS mutant and the WT strain

3.3. Analysis of DEGs

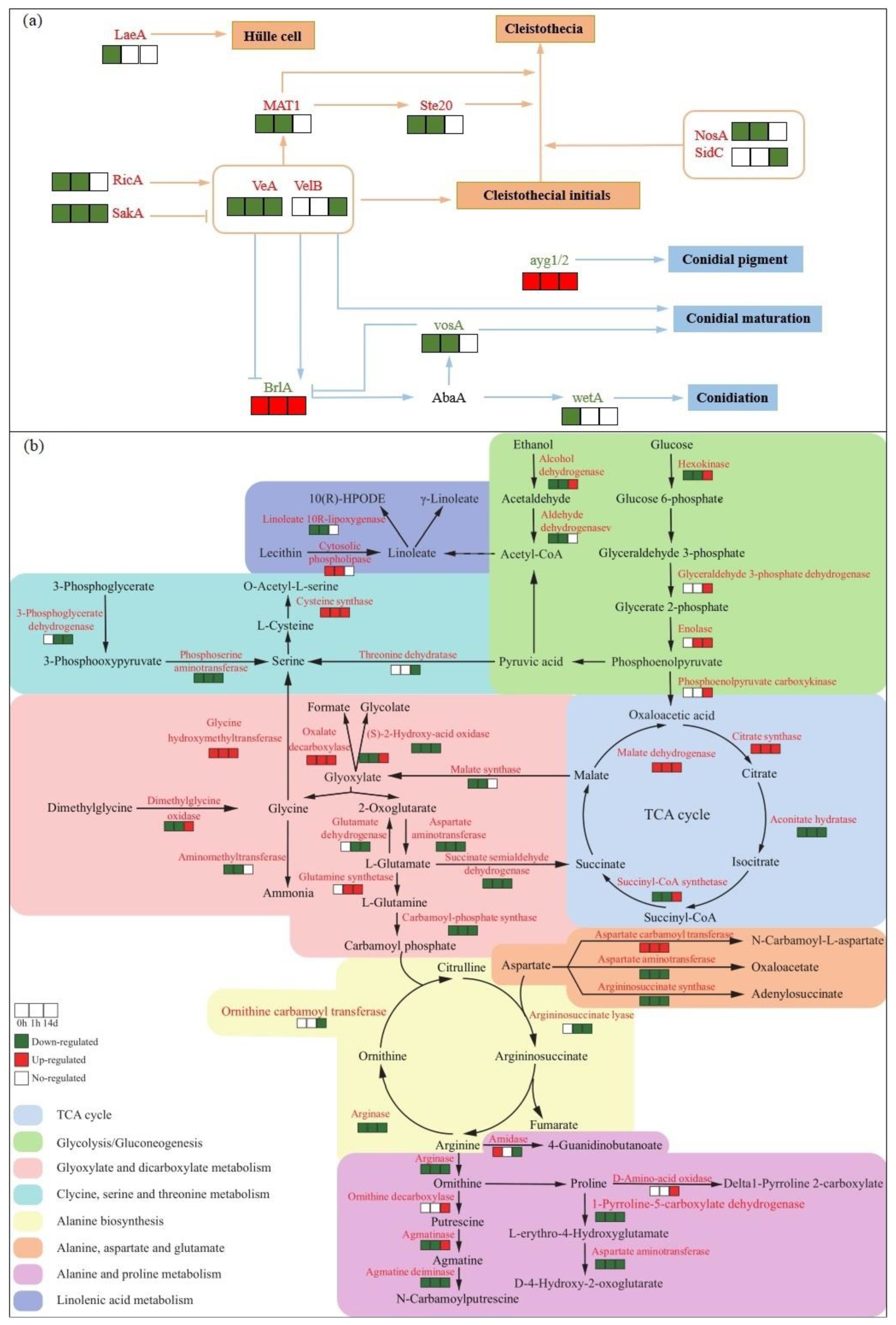

3.4. DEGs significantly related to ABC transporters, nitrogen and carbon metabolism, and sexual reproduction

3.5. Differentially accumulated metabolites regulated by LeuRS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, H.S.; Jun, S.C.; Han, K.H.; Hong, S.B.; Yu, J.H. Diversity, application, and synthetic biology of industrially important Aspergillus fungi. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 100, 161–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, S.; Nakabayashi, R.; Ogawa, C.; Kimura, Y.; Yokota, S.; Doi, M. Characterization of surface Aspergillus community involved in traditional fermentation and ripening of katsuobushi. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 327, 108654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copetti, M. V.; Iamanaka, B.T.; Frisvad, J.C.; Pereira, J.L.; Taniwaki, M.H. Mycobiota of cocoa: from farm to chocolate. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.A.; Kim, E.; Yang, S.M.; Lee, S.; Yoon, S.R.; Jang, K.S.; Kim, H.Y. High-throughput sequencing of the microbial community associated with the physicochemical properties of meju (dried fermented soybean) and doenjang (traditional Korean fermented soybean paste). LWT 2021, 146, 111473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Mao, Y.; Teng, J.; Xia, N.; Huang, L.; Wei, B.; Chen, Q. Evaluation of mycoflora and citrinin occurrence in Chinese Liupao Tea. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2020, 68, 12116–12123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Wei, B.Y.; Teng, J.W.; Huang, L.; Xia, N. Analyses of fungal community by Illumina MiSeq platforms and characterization of Eurotium species on Liupao tea, a distinctive post-fermented tea from China. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, A.; Wang, Y.; Wen, J.; Liu, P.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z. Fungal community associated with fermentation and storage of Fuzhuan brick-tea. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 146, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Liu, K.; Lu, Y.; Gong, G. Morphological, transcriptional, and metabolic analyses of osmotic-adapted mechanisms of the halophilic Aspergillus montevidensis ZYD4 under hypersaline conditions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 3829–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.H.; Ding, X.W.; Narsing Rao, M.P.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.G.; Liu, F.H.; Liu, B.B.; Xiao, M.; Li, W.J. Morphological and transcriptomic analysis reveals the osmoadaptive response of endophytic fungus Aspergillus montevidensis ZYD4 to high salt stress. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukalo, M.; Yaremchuk, A.; Fukunaga, R.; Yokoyama, S.; Cusack, S. The crystal structure of leucyl-tRNA synthetase complexed with tRNALeu in the post-transfer-editing conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krijgsheld, P.; Bleichrodt, R.; van Veluw, G.J.; Wang, F.; Müller, W.H.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Wösten, H.A.B. Development in aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 2013, 74, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, P.S.; O’Gorman, C.M. Sexual development and cryptic sexuality in fungi: insights from Aspergillus species. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 165–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojeda-López, M.; Chen, W.; Eagle, C.E.; Gutiérrez, G.; Jia, W.L.; Swilaiman, S.S.; Huang, Z.; Park, H.S.; Yu, J.H.; Cánovas, D.; Dyer, P.S. Evolution of asexual and sexual reproduction in the aspergilli. Stud. Mycol. 2018, 91, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condon, K.J.; Sabatini, D.M. Nutrient regulation of mTORC1 at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs222570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Mashkoor, M.; Grove, A. Yeast Crf1p: An activator in need is an activator indeed. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 20, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, I.; Lee, C.; Sichani, M.F.; Kang, J.S.; Kang, J.; Guo, M.; Lee, K.Y.; Han, G.; Kim, S.; Han, J.M. Coordination of the leucine-sensing Rag GTPase cycle by leucyl-tRNA synthetase in the mTORC1 signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, E5279–E5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Q.Q.; Fang, Z.P.; Ye, Q.; Chi, C.W.; Wang, E.D. Self-protective responses to norvaline-induced stress in a leucyl-tRNA synthetase editing-deficient yeast strain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 7367–7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, I.; Nam, M.; Kim, H.K.; Moon, H.S.; Kim, Sungmin, Jang, J.; Song, J.A.; Jeong, S.J.; Kim, S.B.; Cho, S., Kim, Y.H.; Lee, J.; Yang, W.S.; Yoo, H.C.; Kim, K., Kim, M.S.; Yang, A.; Cho, K.; Park, H.S.; Hwang, G.S.; Hwang, K.Y.; Han, J.M.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S. Glucose-dependent control of leucine metabolism by leucyl-tRNA synthetase 1. Science 2020, 367, 205–210. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhao, S.; Gong, J.; Huang, M.; Yu, W.; Zhang, K.; Hu, D. Dissipation and the effects of thidiazuron on antioxidant enzyme activity and malondialdehyde content in strawberry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 4331–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ding, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, W. Complete genome sequencing of halophilic endophytic Aspergillus montevidensis, strain ZYD4, isolated from alfalfa stems grown in saline-alkaline soils. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2022, 35, 867–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cao, Y.R.; Zhang, C.C.; Fan, H.F.; Guo, Z.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Chen, M.; Han, J.J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, K.Q.; Liang, L.M. An efficient gene disruption system for the nematophagous fungus Purpureocillium lavendulum. Fungal Biol. 2019, 123, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, Z.; Mauceli, E.; Hacohen, N.; Gnirke, A.; Rhind, N.; Di Palma, F.; Birren, B.W.; Nusbaum, C.; Lindblad-Toh, K.; Friedman, N.; Regev, A. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriya, Y.; Itoh, M.; Okuda, S.; Yoshizawa, A.C.; Kanehisa, M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W182-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trygg, J.; Wold, S. Orthogonal projections to latent structures (O-PLS). J. Chemom. 2002, 16, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostinčar, C.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. Overview of oxidative stress response genes in selected halophilic fungi. Genes (Basel) 2018, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoulou, F.L.; Kerr, I.D. ABC transporter research: going strong 40 years on. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.; Tampé, R. Structural and mechanistic principles of ABC transporters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2020, 89, 605–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Delgado, D.; Dadshani, S.; Schoof, H.; Oyiga, B.C.; Schneider, M.; Mathew, B.; Léon, J.; Ballvora, A. Transcriptome profiling at osmotic and ionic phases of salt stress response in bread wheat uncovers trait-specific candidate genes. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Hong, C.P.; Thak, E.J.; Park, S.G.; Lee, C.H.; Lim, J.Y.; Seo, J.A.; Kang, H.A. Integrated genomic and transcriptomic analysis reveals unique mechanisms for high osmotolerance and halotolerance in Hyphopichia yeast. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 3499–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; van’t Klooster, J.S.; Ruiz, S.J.; Poolman, B. Regulation of amino acid transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2019, 83, e00024-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, M.; Turkyilmaz Unal, B.; García-Caparrós, P.; Khursheed, A.; Gul, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Osmoregulation and its actions during the drought stress in plants. Physiol. Plant 2021, 172, 1321–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashmi, D.; Barvkar, V.T.; Nadaf, A.; Mundhe, S.; Kadoo, N.Y. Integrative omics analysis in Pandanus odorifer (Forssk.) Kuntze reveals the role of asparagine synthetase in salinity tolerance. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Yuan, Y.Z.; Ou, J.Q.; Lin, Q.H.; Zhang, C.F. Glutamine synthetase and glutamate dehydrogenase contribute differentially to proline accumulation in leaves of wheat (Triticum aestivum) seedlings exposed to different salinity. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 164, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi, Y.; Yoshiba, Y.; Sanada, Y.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Wada, K.; Shinozaki, K. Characterization of the gene for delta1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase and correlation between the expression of the gene and salt tolerance in Oryza sativa L. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997, 33, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushtaq, A.; Tariq, M.; Ahmed, M.; Zhou, Z.; Ali, I.; Mahmood, R.T. Carbamoyl phosphate synthase subunit CgCPS1 is necessary for virulence and to regulate stress tolerance in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Plant Pathol. J. 2021, 37, 414–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Shi, L.; Yang, R.; Guo, H.; Zhang, S.; Geng, G. Transcriptome analysis of Auricularia fibrillifera fruit-body responses to drought stress and rehydration. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hernández, A.I.; Scalschi, L.; Vicedo, B.; Marcos-Barbero, E.L.; Morcuende, R.; Camañes, G. Putrescine: A key metabolite involved in plant development, tolerance and resistance responses to stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Lu, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Fu, R. Transcriptional profiling provides new insights into the role of nitric oxide in enhancing Ganoderma oregonense resistance to heat stress. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.J.; Batista Fontes, E.P.; Modolo, L.V. Salinity-induced accumulation of endogenous H2S and NO is associated with modulation of the antioxidant and redox defense systems in Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Havana. Plant Sci. 2017, 256, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, H.; Jin, J.; Ma, X.; Li, K. Physiological and transcriptome analysis on diploid and polyploid Populus ussuriensis Kom. under salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thackray, P.D.; Moir, A. SigM, an extracytoplasmic function sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis, is activated in response to cell wall antibiotics, ethanol, heat, acid, and superoxide stress. J. Bacteriol. 185, 3491–3498. [CrossRef]

- Mattila, J.; Hietakangas, V. Regulation of carbohydrate energy metabolism in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 2017, 207, 1231–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Díaz, J.; Batista-Silva, W.; Almada, R.; Medeiros, D.B.; Arrivault, S.; Correa, F.; Bastías, A.; Rojas, P.; Beltrán, M.F.; Pozo, M.F.; Araújo, W.L.; Sagredo, B. Prunus hexokinase 3 genes alter primary C-metabolism and promote drought and salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis transgenic plants. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.; Rangani, J.; Parida, A.K. Comprehensive proteomic analysis revealing multifaceted regulatory network of the xero-halophyte Haloxylon salicornicum involved in salt tolerance. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 324, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, A.; Marín-Guirao, L.; Serra, I.A.; Spadafora, A.; Sandoval-Gil, J.M.; Bernardeau-Esteller, J.; Fernandez, J.M.R.; Mazzuca, S. The modulation of leaf metabolism plays a role in salt tolerance of Cymodocea nodosa exposed to hypersaline stress in mesocosms. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Zhou, R.; Wang, X.; Dossa, K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Gong, H.; Zhang, X.; You, J. Transcriptome and metabolome analyses of two contrasting sesame genotypes reveal the crucial biological pathways involved in rapid adaptive response to salt stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayram, Ö.; Krappmann, S.; Ni, M.; Jin, W.B.; Helmstaedt, K.; Valerius, O.; Braus-Stromeyer, S.; Kwon, N.J.; Keller, N.P.; Yu, J.H.; Braus, G.H. VelB/VeA/LaeA complex coordinates light signal with fungal development and secondary metabolism. Science 2008, 320, 1504–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Han, K.Y.; Kim, K.J.; Han, D.M.; Jahng, K.Y.; Chae, K.S. The veA gene activates sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2002, 37, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikaya Bayram, O.; Bayram, O.; Valerius, O.; Park, H.S.; Irniger, S.; Gerke, J.; Ni, M.; Han, K.H.; Yu, J.H.; Braus, G.H. LaeA control of velvet family regulatory proteins for light-dependent development and fungal cell-type specificity. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ge, Y.; Ren, X.; Ren, C.; Wang, Y.; Ren, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z. The role of the veA gene in adjusting developmental balance and environmental stress response in Aspergillus cristatus. Fungal Biol. 2018, 122, 952–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, N.J.; Park, H.S.; Jung, S.; Kim, S.C.; Yu, J.H. The putative guanine nucleotide exchange factor RicA mediates upstream signaling for growth and development in Aspergillus. Eukaryot. Cell 2012, 11, 1399–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).