Submitted:

23 April 2025

Posted:

23 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Isolation, Growth Rate Determination

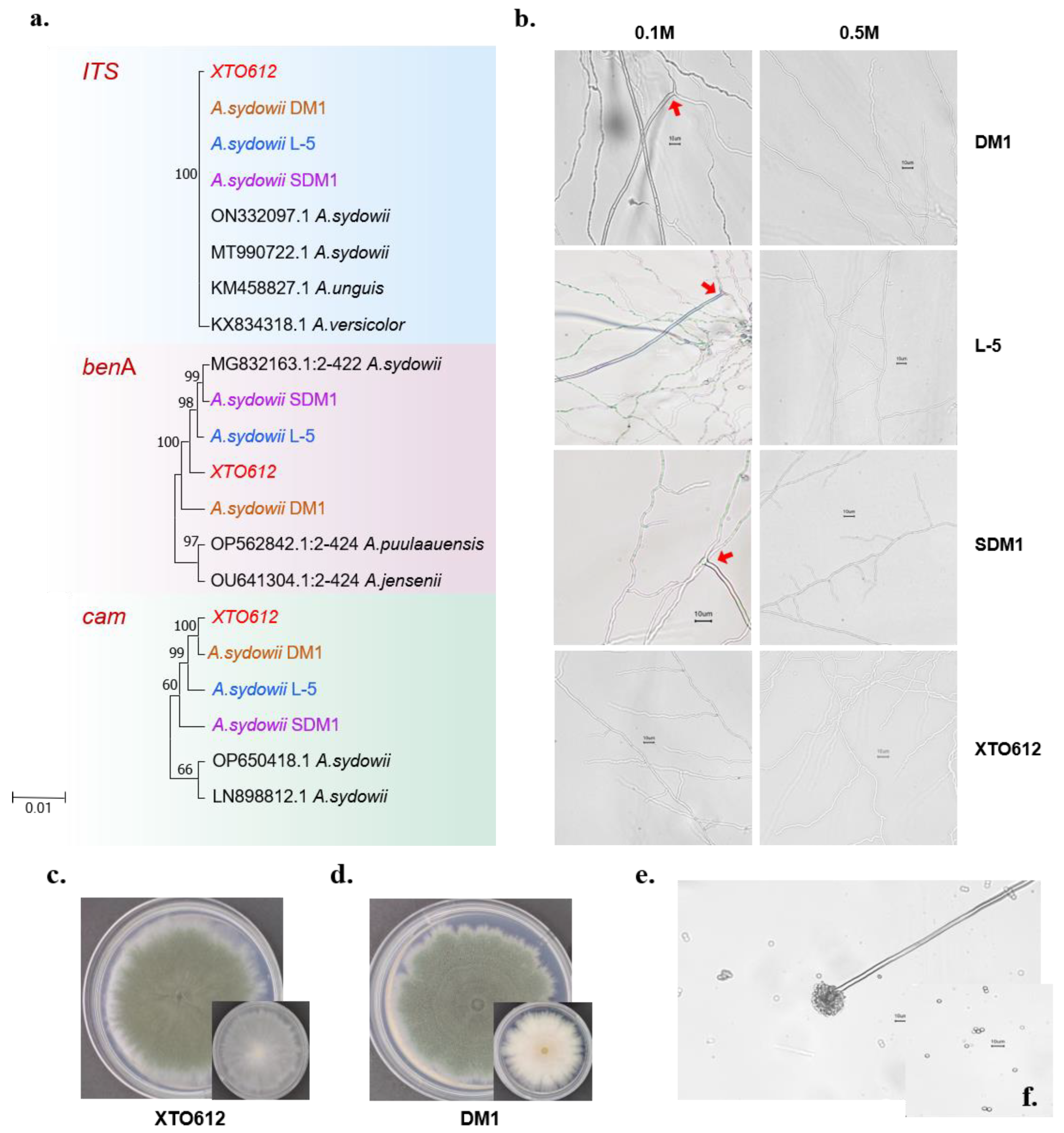

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.3. Morphological Characterization of A. sydowii

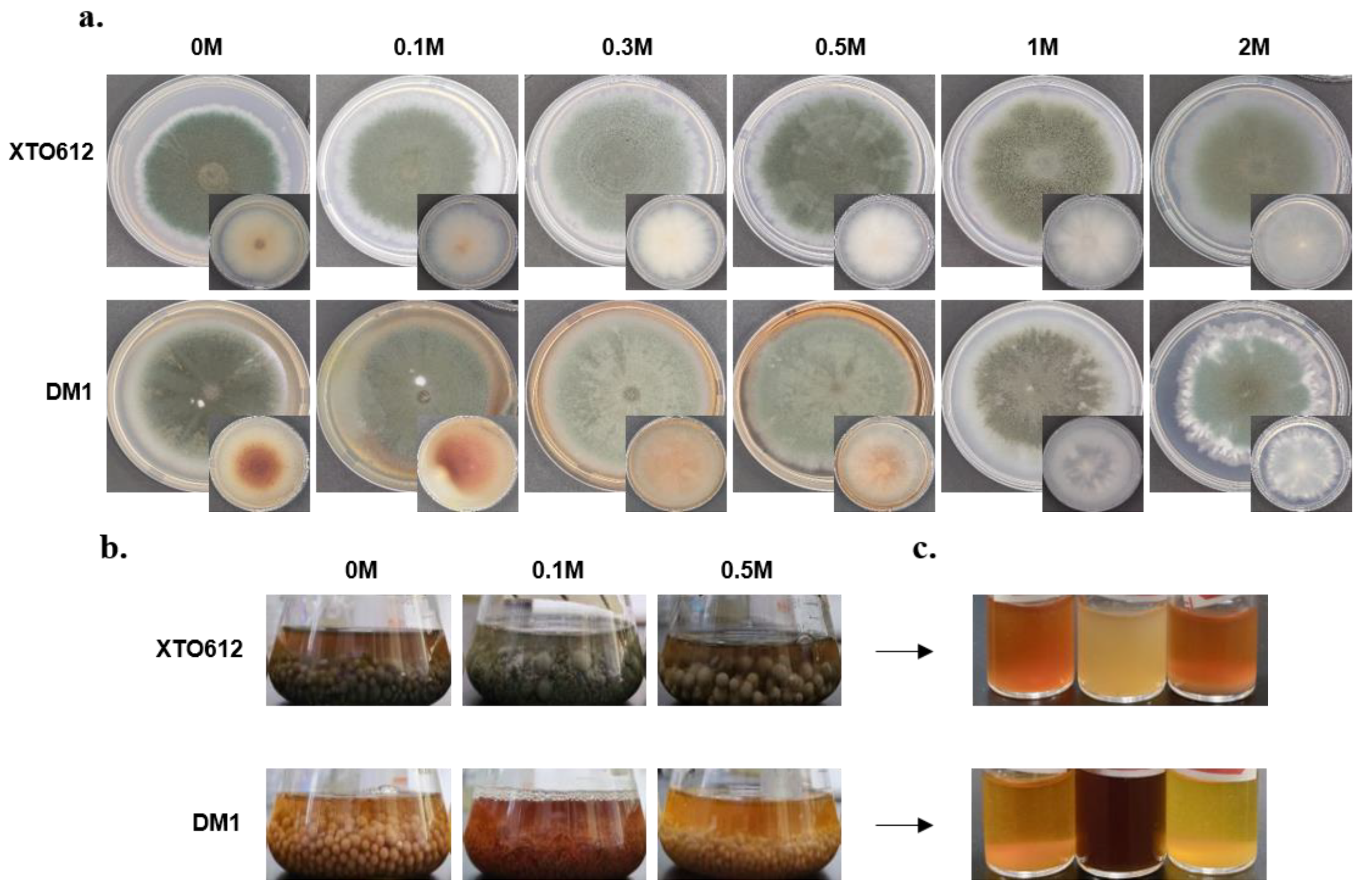

2.4. Secondary Metabolite Analysis of Two A. sydowii

2.5. Conidial Number and Evaluation of Metabolic Activity of Polarized Growth Conidia of A. sydowii

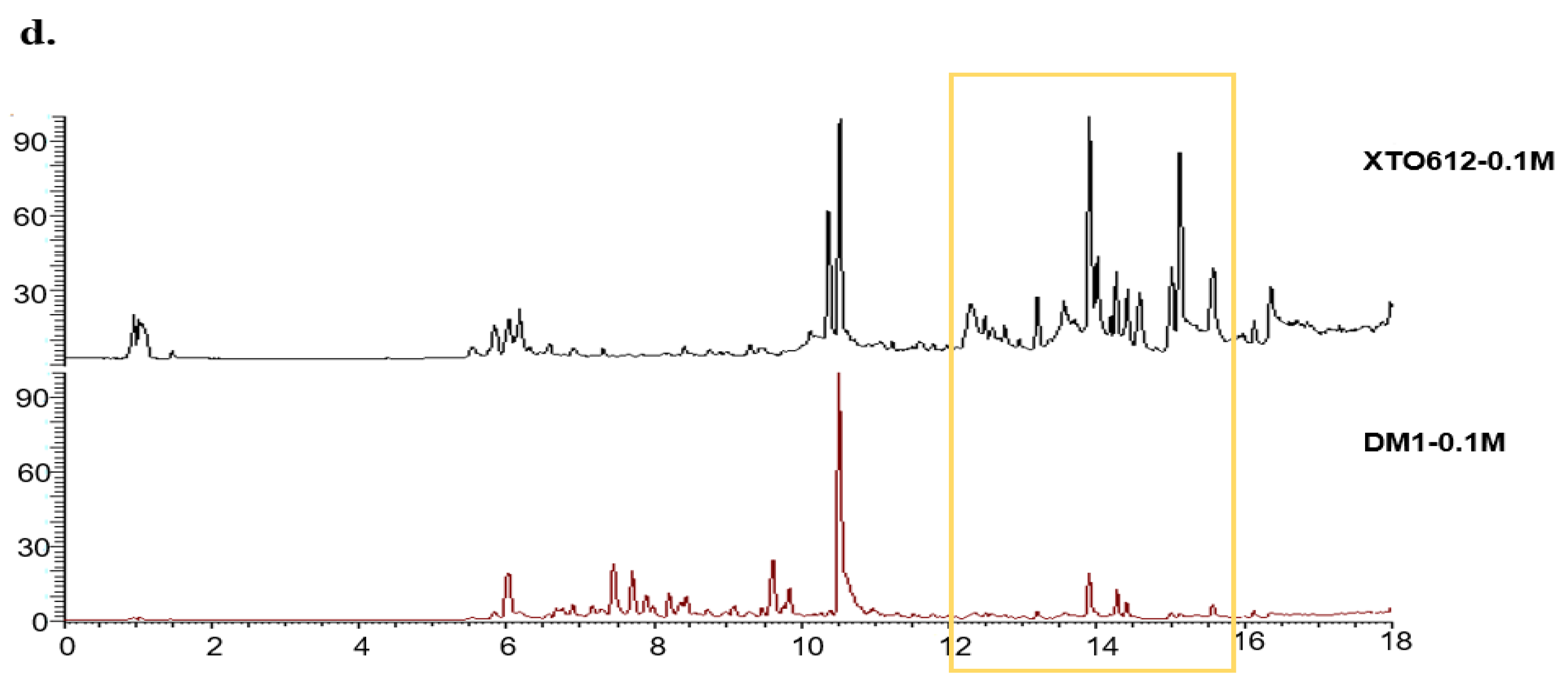

2.6. Determination of Mycelial Septum Length of Two A. sydowii

2.7. Reactive Oxygen Measurements of A. sydowii

2.8. RNA-Seq Analysis

3.0. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of A. sydowii XTO612 from the Gut of Hadal Amphipods

3.2. Secondary Metabolism of A. sydowii Differs Under Hypotonic Stress from Different Habitats

3.3. Enhanced Growth of A. sydowii XTO612 Under Hypoosmotic Stress

3.4. Enhanced Metabolic Activity of A. sydowii XTO612 Under Hypoosmotic Stress

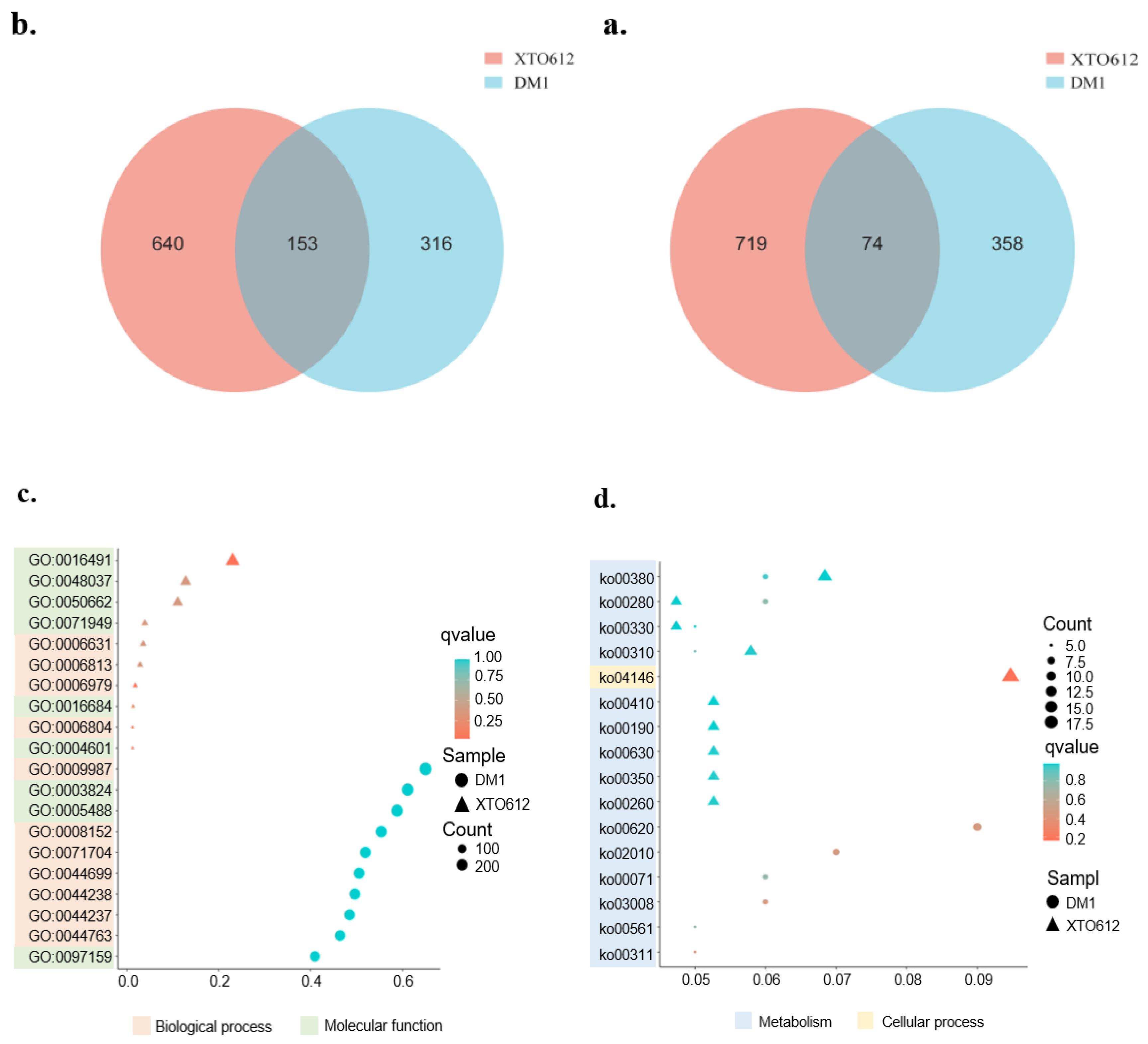

3.5. Transcriptome Overview, Differentially Expressed Genes, and Enrichment Analysis

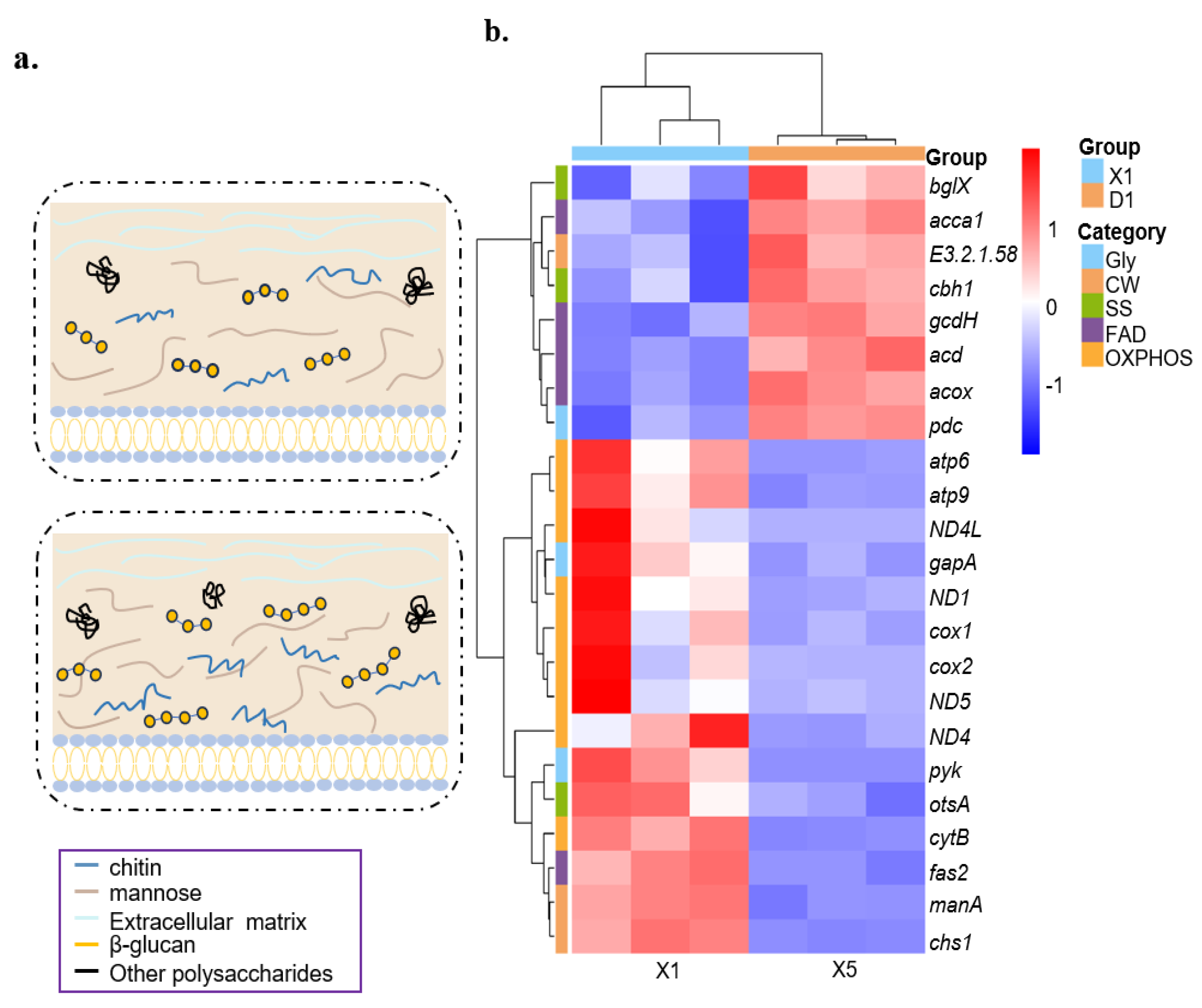

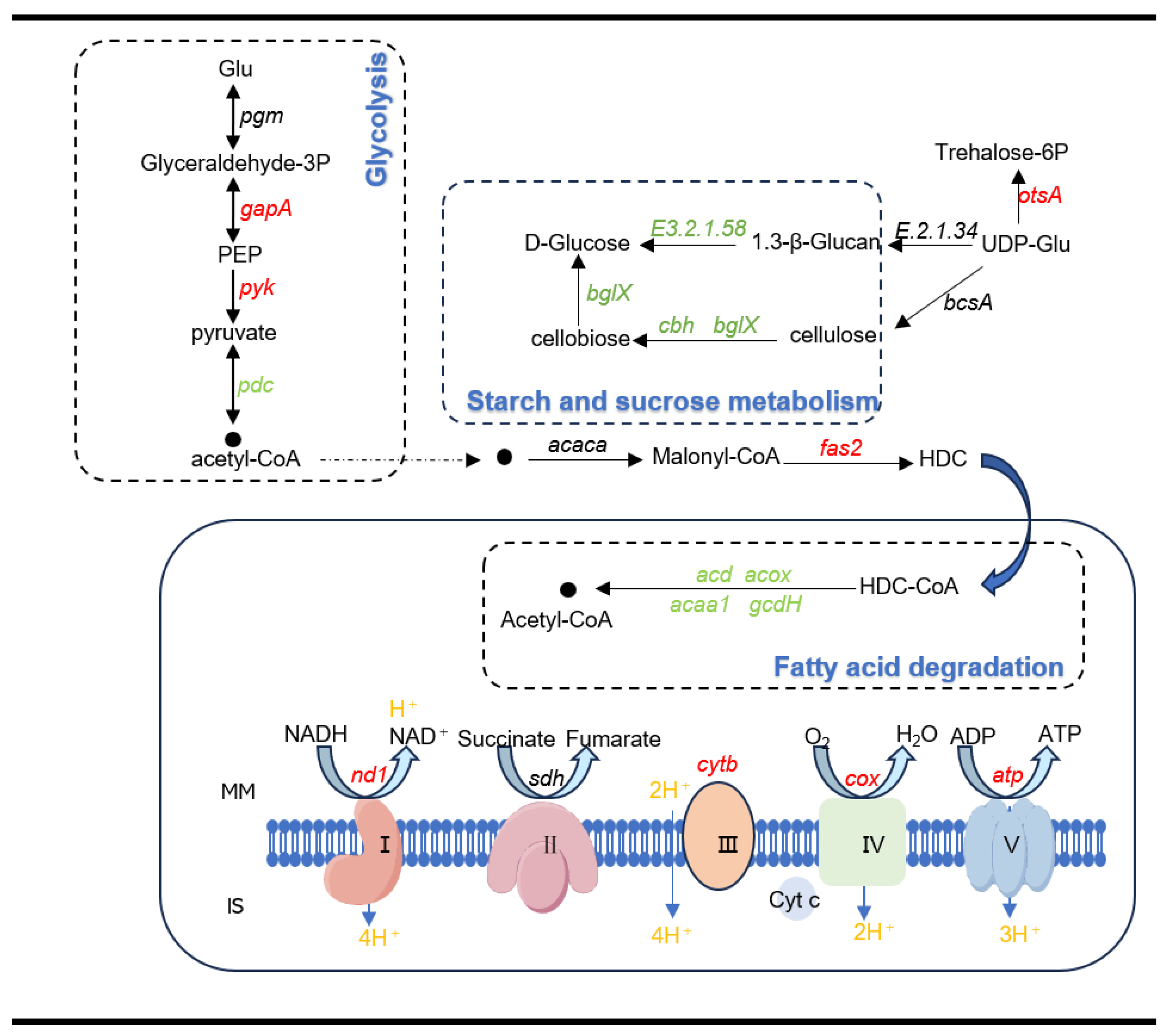

3.6. Cell Wall Composition Shows Variations Under Hypotonic Stress

3.7. Energy Metabolic Pathways Shows Variations Under Hypotonic Stress

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, C.; Pan, H.; Zhou, H.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Lin, Y.; Li, L. Marine microbial applications and prospects. science and technology information 2010, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Lyla, P.S.; Khan, S.A. Marine microbial diversity and ecology: importance and future perspectives. Current Science 2006, 90, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. ; Qin, Y, The Characteristic of Deep Sea Hydrothermal Ecosystem and Their Impact on the Extreme Microorganism. Advances in Earth Science 2017, 32, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustace, R.M.; Kilgallen, N.M.; Lacey, N.C.; Jamieson, A.J. Population Structure of the Hadal Amphipod Hirondellea Gigas (Amphipoda: Lysianassoidea) from the Izu-Bonin Trench. Journal of Crustacean Biology 2013, 33, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, M.; Abramović, Z.; Plemenitaš, A.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. Salt stress and plasma-membrane fluidity in selected extremophilic yeasts and yeast-like fungi. FEMS Yeast Research 2007, 7, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauceo, J.M.; Blankenship, J.R.; Fanning, S.; Hamaker, J.J.; Deneault, J.-S.; Smith, F.J.; Nantel, A.; Mitchell, A.P. Regulation of the Candida albicans Cell Wall Damage Response by Transcription Factor Sko1 and PAS Kinase Psk1. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2008, 19, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, S.; Wysong, D.; Debeaupuis, J.-P.; Shibuya, K.; Philippe, B.; Diamond Richard, D.; Latgé, J.-P. Catalases of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infection and Immunity 2003, 71, 3551–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, A.J.; Fujii, T.; Mayor, D.J.; Solan, M.; Priede, I.G. Hadal trenches: the ecology of the deepest places on Earth. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Li, Y.; Deng, L.; Fang, J.; Yu, X. High hydrostatic pressure shapes the development and production of secondary metabolites of Mariana Trench sediment fungi. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 11436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pupo, E.C.; Pérez-Llano, Y.; Tinoco-Valencia, J.R.; Sánchez, N.S.; Padilla-Garfias, F.; Calahorra, M.; Sánchez, N.D.C.; Sánchez-Reyes, A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, M.D.R.; Peña, A.; et al. Osmolyte Signatures for the Protection of Aspergillus sydowii Cells under Halophilic Conditions and Osmotic Shock. Journal of Fungi 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajc, J.; Zalar, P.; Plemenitaš, A. Biology of Marine Fungi. Progress in Molecular and Subcellular Biology, vol 53. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp. 133–158. [CrossRef]

- Alker, A.P.; Smith, G.W.; Kim, K. Characterization of Aspergillus sydowii (Thom et Church), a fungal pathogen of Caribbean sea fan corals. Hydrobiologia 2001, 460, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman Brian, C.; Chen, C.; Yu, X.; Nielsen, L.; Peterson, K.; Beattie Gwyn, A. Physiological and Transcriptional Responses to Osmotic Stress of Two Pseudomonas syringae Strains That Differ in Epiphytic Fitness and Osmotolerance. Journal of Bacteriology 2013, 195, 4742–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, R.; Cary, J.W.; Calvo, A.M. Role of the Osmotic Stress Regulatory Pathway in Morphogenesis and Secondary Metabolism in Filamentous Fungi. Toxins 2010, 2, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, D.E.N.; Finlay, R.D.; Hallsworth, J.E.; Dadachova, E.; Gadd, G.M. Fungal strategies for dealing with environment- and agriculture-induced stresses. Fungal Biology 2018, 122, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijksterhuis, J.; de Vries, Ronald, P. Compatible solutes and fungal development. Biochemical Journal 2006, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, M.; Méjanelle, L.; Šentjurc, M.; Grimalt, J.O.; Gunde-Cimerman, N.; Plemenitaš, A. Salt-induced changes in lipid composition and membrane fluidity of halophilic yeast-like melanized fungi. Extremophiles 2004, 8, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralj Kunčič, M.; Kogej, T.; Drobne, D.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. Morphological Response of the Halophilic Fungal Genus Wallemia to High Salinity. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2009, 76, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, A.M.; Wilson, R.A.; Bok, J.W.; Keller, N.P. Relationship between secondary metabolism and fungal development. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2002, 66, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiser, D.M.; Taylor, J.W.; Ritchie, K.B.; Smith, G.W. Cause of sea fan death in the West Indies. Nature 1998, 394, 137–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Fadil, S.A.; Fadil, H.A.; Eshmawi, B.A.; Mohamed, S.G.A.; Mohamed, G.A. Fungal Naphthalenones; Promising Metabolites for Drug Discovery: Structures, Biosynthesis, Sources, and Pharmacological Potential. Toxins (Basel) 2022, 14, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-N.; Mou, Y.-H.; Dong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, B.-Y.; Bai, J.; Yan, D.-J.; Zhang, L.; Feng, D.-Q.; Pei, Y.-H.; et al. Diphenyl Ethers from a Marine-Derived Aspergillus sydowii. Marine Drugs 2018, 16, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, K.K.S.A.; Albuquerque, W.W.C.; Costa, R.M.P.B.; Batista, J.M.S.; Marques, D.A.V.; Bezerra, R.P.; Herculano, P.N.; Porto, A.L.F. Biotechnological potential of a novel tannase-acyl hydrolase from Aspergillus sydowii using waste coir residue: Aqueous two-phase system and chromatographic techniques. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2020, 23, 101453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwan, S.H.; Ammar, M.S.; Mohawed, S.M. Lipases from Aspergillus sydowi. Zentralblatt für Mikrobiologie 1986, 141, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Llano, Y.; Rodríguez-Pupo, E.C.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Chenthamara, K.; Cai, F.; Gunde-Cimerman, N.; Zalar, P.; Gostinčar, C.; Kostanjšek, R.; Folch-Mallol, J.L.; et al. Stress Reshapes the Physiological Response of Halophile Fungi to Salinity. Cells 2020, 9, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, M.; Li, Y.; Deng, L.; Fang, J.; Yu, X. Insight into the adaptation mechanisms of high hydrostatic pressure in physiology and metabolism of hadal fungi from the deepest ocean sediment. mSystems 2023, 9, e01085–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ji, P.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Fang, J.; Yu, X. Microbial community structure and functional traits involved in the adaptation of culturable bacteria within the gut of amphipods from the deepest ocean. Microbiology Spectrum 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zhong, M.; Li, Y.; Hu, G.; Zhang, C.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, J.; Yu, X. High hydrostatic pressure harnesses the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites via the regulation of polyketide synthesis genes of hadal sediment-derived fungi. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yan, F.; Cui, Y.; Du, J.; Hu, G.; Zhai, W.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, J.; Chen, L.; et al. A symbiotic bacterium of Antarctic fish reveals environmental adaptability mechanisms and biosynthetic potential towards antibacterial and cytotoxic activities. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Li, Y.; Fang, J.; Yu, X. Effects of Epigenetic Modification and High Hydrostatic Pressure on Polyketide Synthase Genes and Secondary Metabolites of Alternaria alternata Derived from the Mariana Trench Sediments. Marine Drugs 2023, 21, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Wan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L. Synergistic Antifungal Effect of a Combination of Iron Deficiency and Calcium Supplementation. Microbiology Spectrum 2022, 10, e01121–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Koopmann, B.; von Tiedemann, A. Methods for Assessment of Viability and Germination of Plasmodiophora brassicae Resting Spores. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bairoch, A.; Apweiler, R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Research 2000, 28, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Bateman, A.; Clements, J.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Heger, A.; Hetherington, K.; Holm, L.; Mistry, J.; :, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. : the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, D222–D230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.J.; Julien, P.; Kuhn, M.; von Mering, C.; Muller, J.; Doerks, T.; Bork, P. eggNOG: automated construction and annotation of orthologous groups of genes. Nucleic Acids Research 2008, 36 (Suppl. 1), D250–D254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gene Ontology, C. The Gene Ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Research 2004, 32 (suppl_1), D258–D261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peidro-Guzmán, H.; Pérez-Llano, Y.; González-Abradelo, D.; Fernández-López, M.G.; Dávila-Ramos, S.; Aranda, E.; Hernández, D.R.O.; García, A.O.; Lira-Ruan, V.; Pliego, O.R.; et al. Transcriptomic analysis of polyaromatic hydrocarbon degradation by the halophilic fungus Aspergillus sydowii at hypersaline conditions. Environ Microbiol 2021, 23, 3435–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25 4, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Wang, B.G. Secondary Metabolites from the Marine Algal-Derived Endophytic Fungi: Chemical Diversity and Biological Activity. Planta Medica 2016, 82, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennicke, C.; Cochemé, H.M. Redox metabolism: ROS as specific molecular regulators of cell signaling and function. Molecular Cell 2021, 81, 3691–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown Alistair, J.P.; Cowen Leah, E.; di Pietro, A.; Quinn, J. Stress Adaptation. Microbiology Spectrum 2017, 5, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.I.; Waters, M. 1 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate Dehydrogenase. In The Enzymes, Boyer, P.D. Ed. Academic Press: 1976; Vol. 13, pp 1-49. [CrossRef]

- Zoraghi, R.; Worrall, L.; See, R.H.; Strangman, W.; Popplewell, W.L.; Gong, H.; Samaai, T.; Swayze, R.D.; Kaur, S.; Vuckovic, M.; et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Pyruvate Kinase as a Target for Bis-indole Alkaloids with Antibacterial Activities*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 44716–44725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enriqueta Muñoz, M.; Ponce, E. Pyruvate kinase: current status of regulatory and functional properties. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2003, 135, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.; Kenney, L.J. A New Role of OmpR in Acid and Osmotic Stress in Salmonella and E. coli. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; George, S.M.; Métris, A.; Li, P.L.; Baranyi, J. Lag Phase of Salmonella enterica under Osmotic Stress Conditions. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2011, 77, 1758–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margesin, R.; Schinner, F. Potential of halotolerant and halophilic microorganisms for biotechnology. Extremophiles 2001, 5, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, S.; Krantz, M.; Nordlander, B. Chapter Two - Yeast Osmoregulation. In Methods in Enzymology, Academic Press: 2007; Vol. 428, pp 29-45. [CrossRef]

- Roeßler, M.; Müller, V. Osmoadaptation in bacteria and archaea: common principles and differences. Environ Microbiol 2001, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.R.; Copp, B.R.; Davis, R.A.; Keyzers, R.A.; Prinsep, M.R. Marine natural products. Natural Product Reports 2020, 37, 175–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghukumar, C.; Muraleedharan, U.; Gaud, V.R.; Mishra, R. Xylanases of marine fungi of potential use for biobleaching of paper pulp. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2004, 31, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, A.M. The VeA regulatory system and its role in morphological and chemical development in fungi. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2008, 45, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouriño-Pérez, R.R. Septum development in filamentous ascomycetes. Fungal Biology Reviews 2013, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Rubio, R.; de Oliveira, H.C.; Rivera, J.; Trevijano-Contador, N. The Fungal Cell Wall: Candida, Cryptococcus, and Aspergillus Species. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).