Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

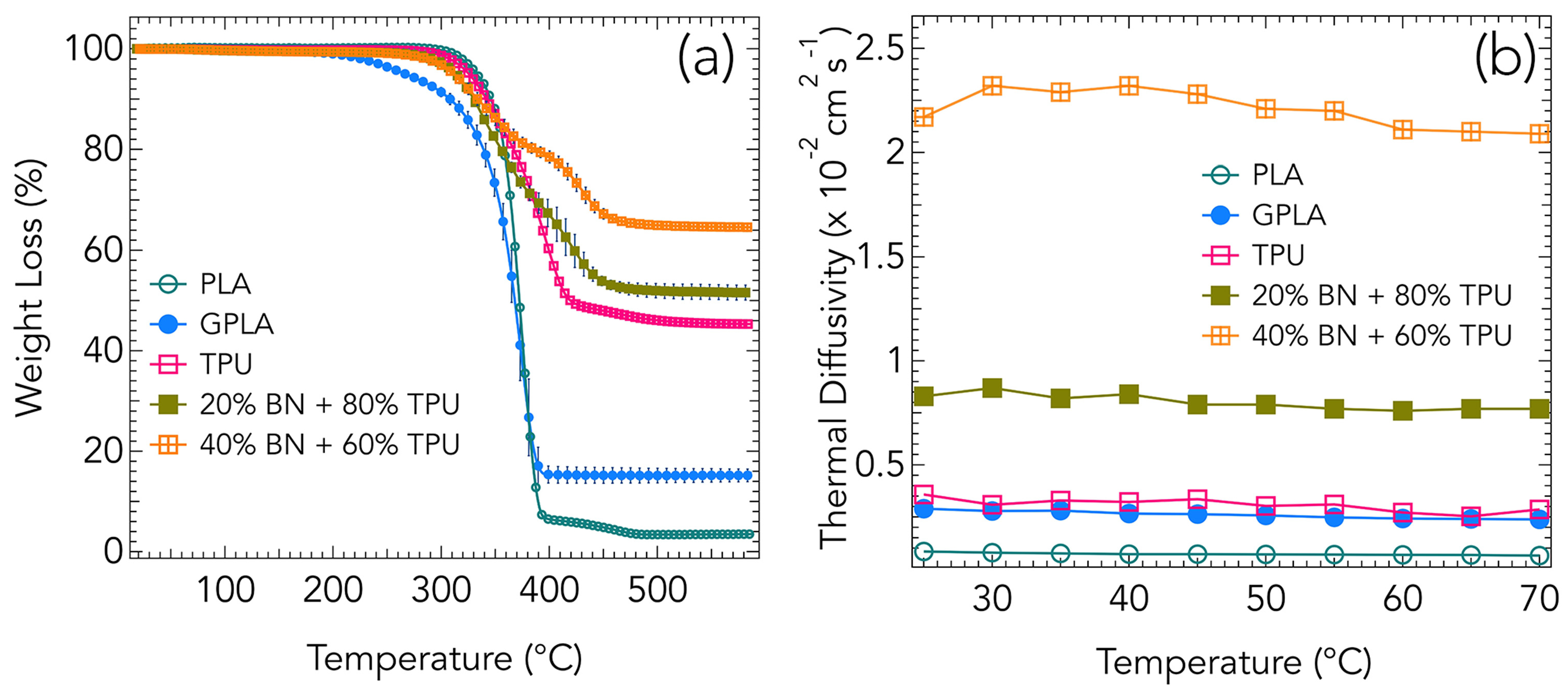

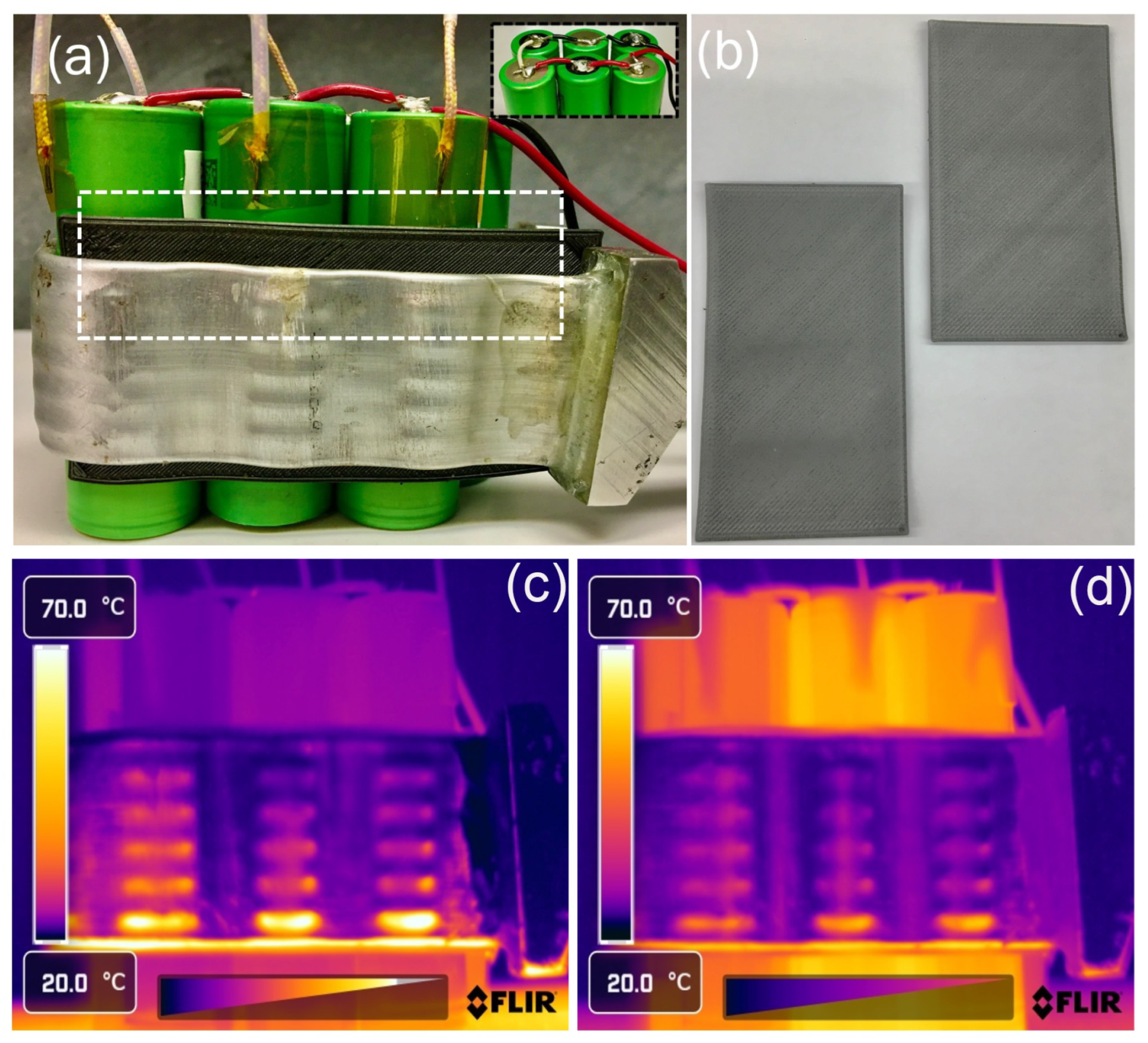

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Fabrication of Thermal Interface Materials

2.3. Characterization Techniques

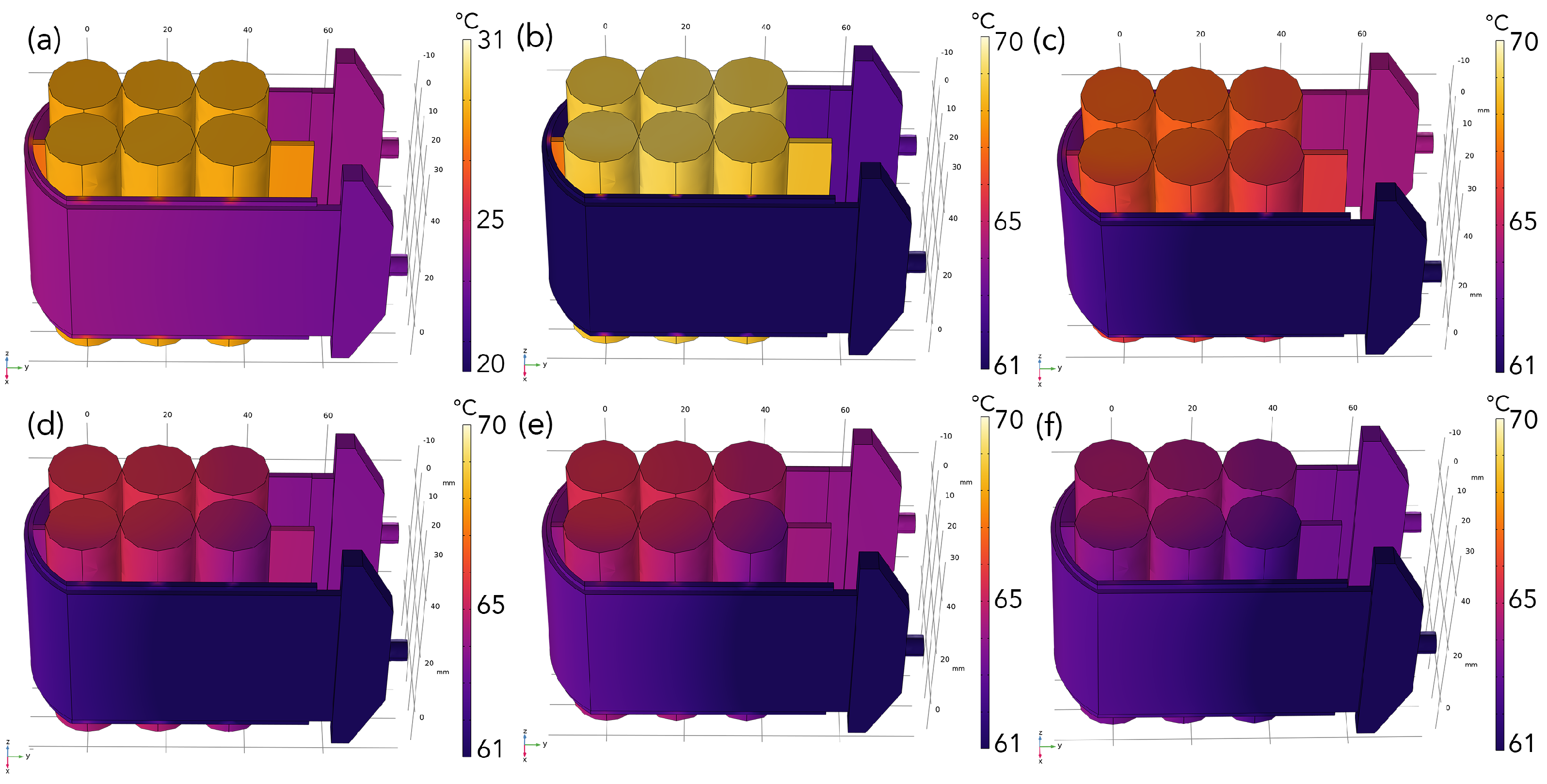

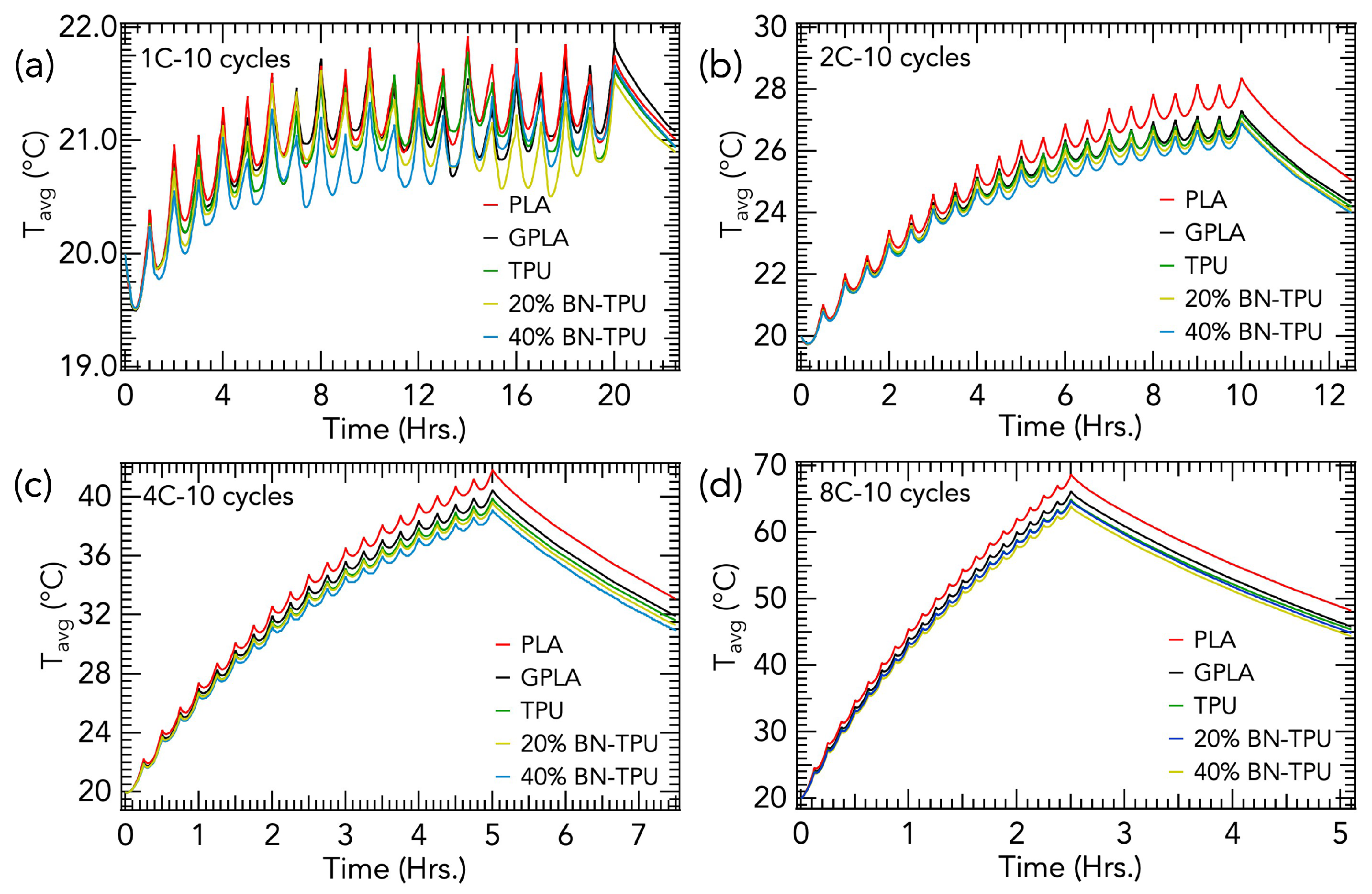

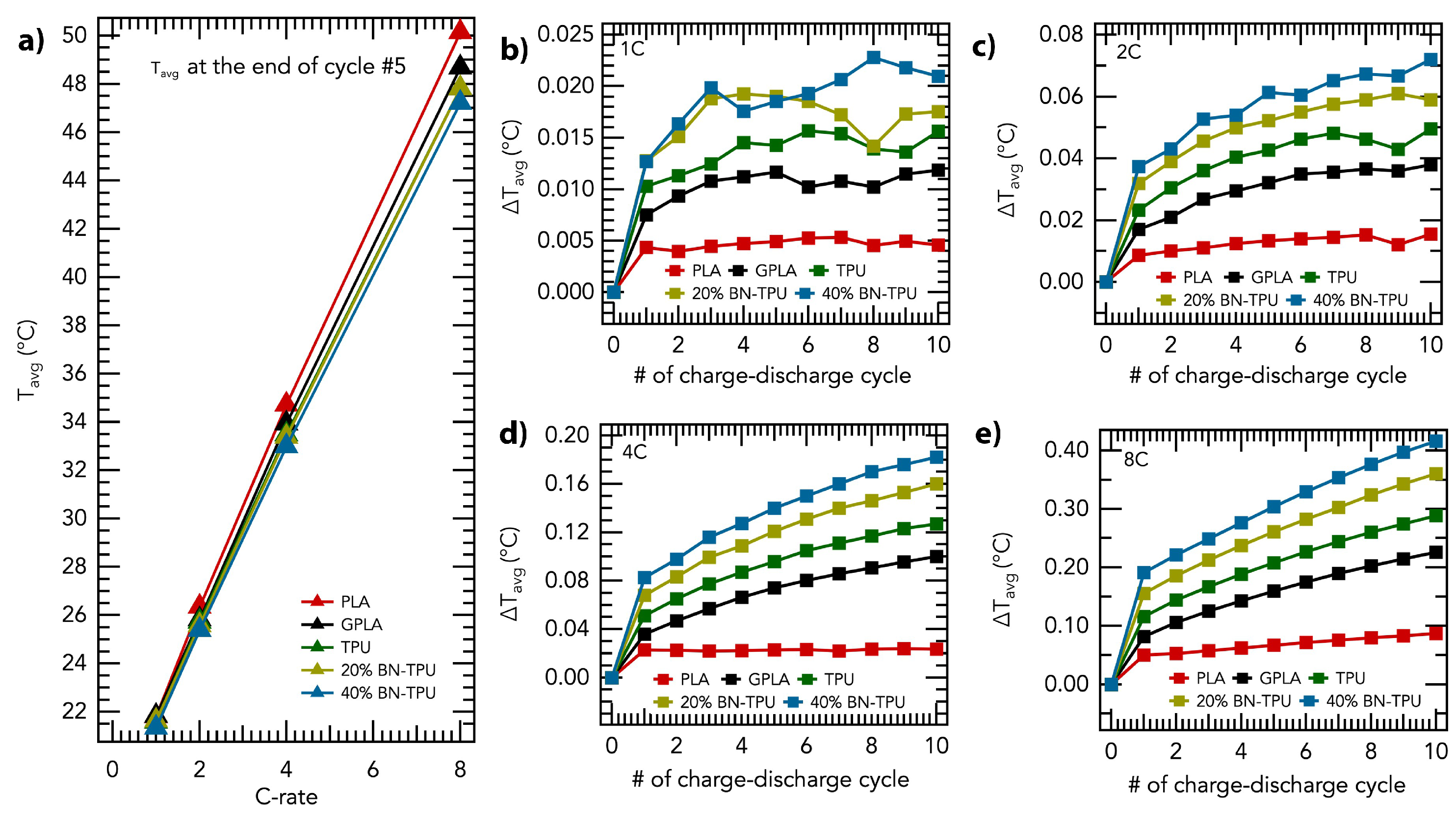

2.4. COMSOL Modeling

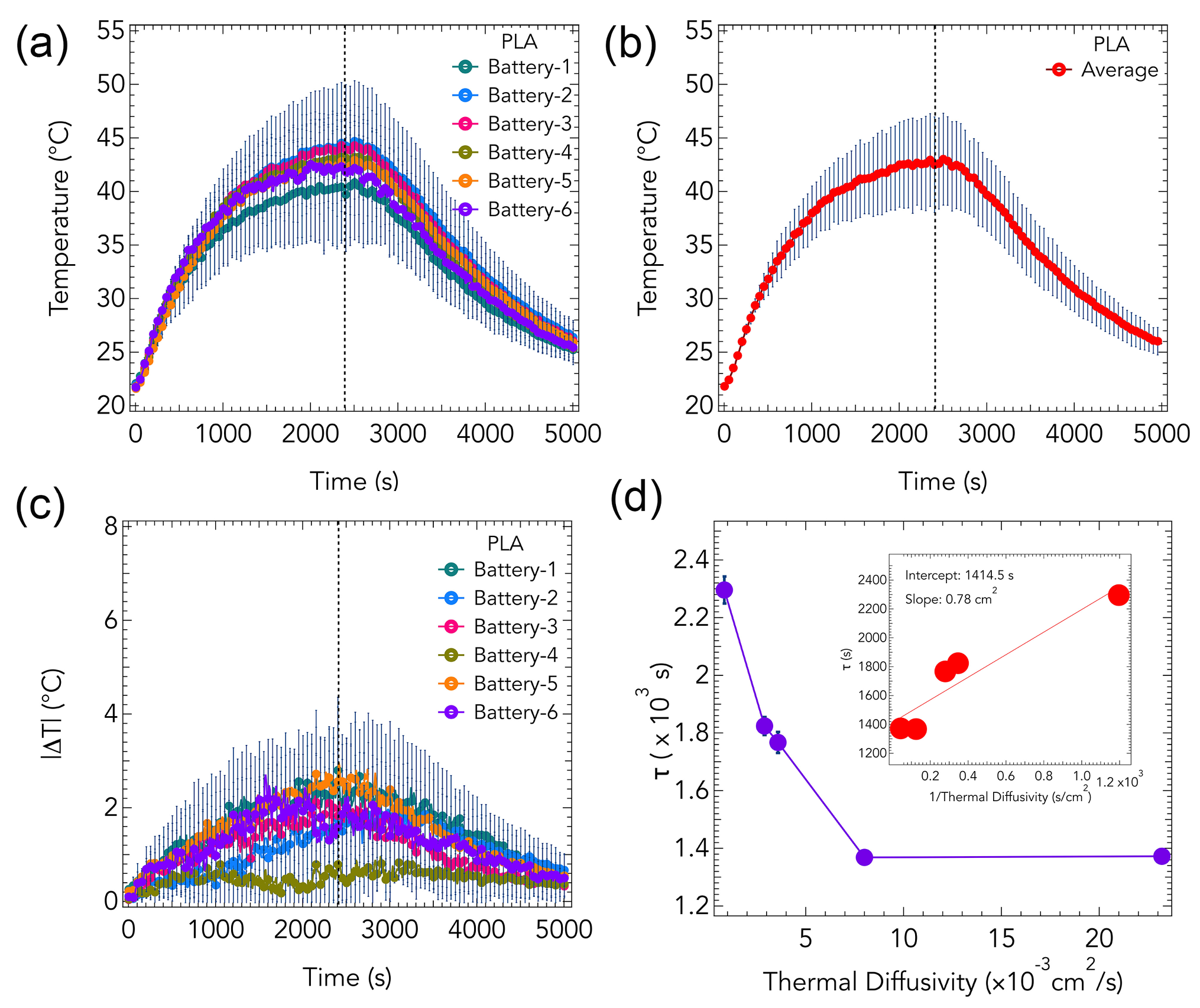

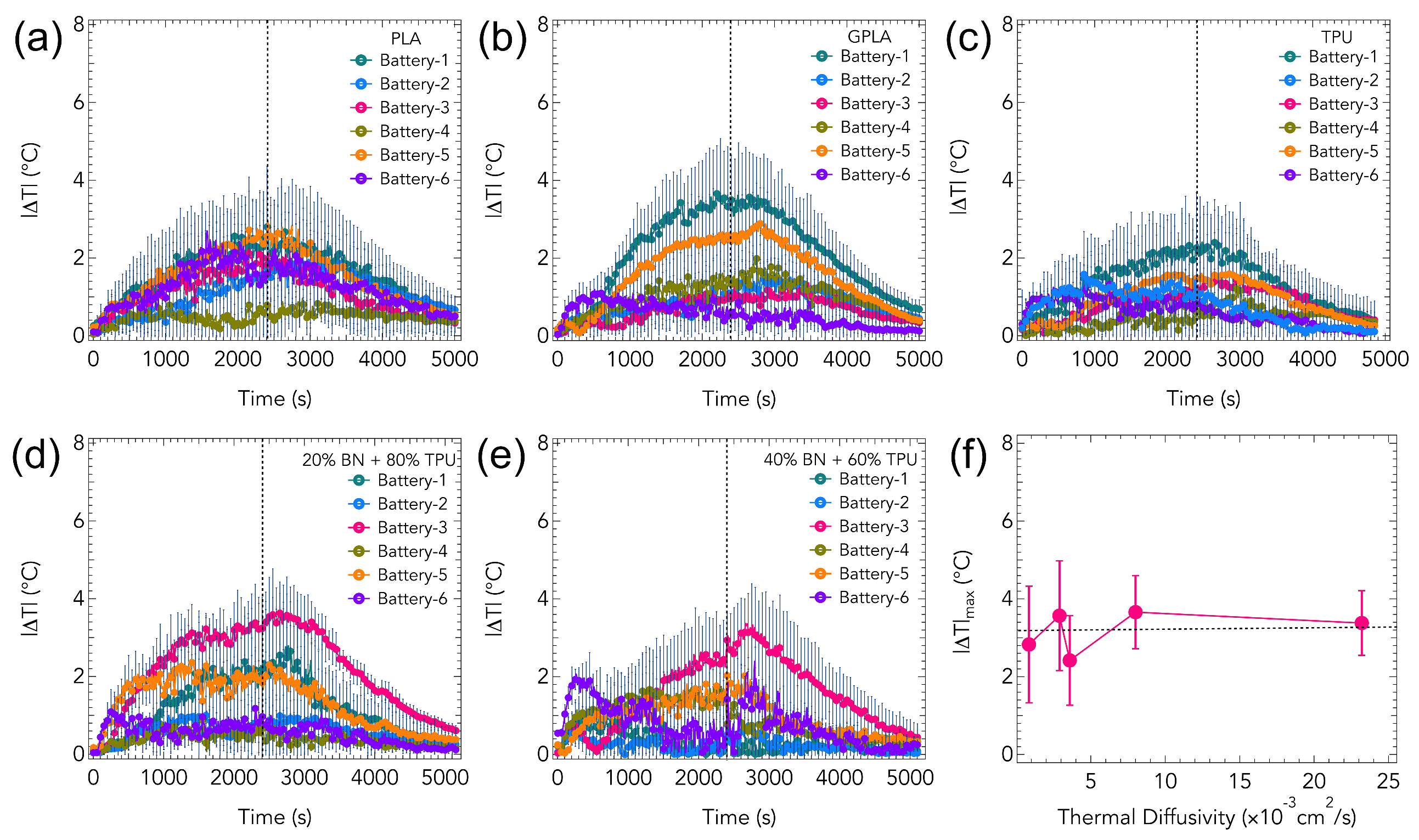

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LIB | Lithium-ion battery |

| TIMs | Thermal interface materials |

| PLA | Polylactic acid PLA |

| GPLA | Graphene-PLA |

| BN | Boron nitride |

| TPU | Thermoplastic polyurethane |

| EVs | Electric vehicles |

| BTMS | Battery thermal management systems |

| h-BN | Hexagonal boron nitride |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| DMF | N, N-dimethylformamide |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| FEM | Finite element method |

References

- Kermani, J.R.; Taheri, M.M.; Pakzad, H.; Minaei, M.; Bijarchi, M.A.; Moosavi, A.; Shafii, M.B. Hybrid battery thermal management systems based on phase transition processes: a comprehensive review. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 86, 111227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, B.; Cai, S. A review of battery thermal management systems using liquid cooling and PCM. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 76, 109836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, S.; Vashisht, S.; Rakshit, D.; Wan, M.P. Recent advancements and performance implications of hybrid battery thermal management systems for Electric Vehicles. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yadav, S.; Salman, M.; Chavan, S.; Kim, S.C. Review of thermal coupled battery models and parameter identification for lithium-ion battery heat generation in EV battery thermal management system. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2024, 218, 124748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, F.S.; Confrey, T.; Reidy, C.; Picovici, D.; Callaghan, D.; Culliton, D.; Nolan, C. Review of battery thermal management systems in electric vehicles. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 192, 114171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.; Maghrabie, H.M.; Adhari, O.H.K.; Sayed, E.T.; Yousef, B.A.; Salameh, T.; Kamil, M.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Battery thermal management systems: Recent progress and challenges. International Journal of Thermofluids 2022, 15, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Yang, S. A review on recent progress, challenges and perspective of battery thermal management system. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2021, 167, 120834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalkhani, M.; Habibi, S. Review of the Li-ion battery, thermal management, and AI-based battery management system for EV application. Energies 2022, 16, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longchamps, R.S.; Yang, X.G.; Wang, C.Y. Fundamental insights into battery thermal management and safety. ACS Energy Letters 2022, 7, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, K.; Ge, M.; Gan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Chen, S. Thermal-responsive and fire-resistant materials for high-safety lithium-ion batteries. Small 2021, 17, 2103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Weng, L.; Ge, S.; Jiang, D.; Huang, M.; Mulvihill, D.M.; Chen, Q.; Guo, Z.; Jazzar, A.; et al. A roadmap review of thermally conductive polymer composites: critical factors, progress, and prospects. Advanced functional materials 2023, 33, 2301549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, B.; Song, M.; Wu, X. An air-cooled system with a control strategy for efficient battery thermal management. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 236, 121578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaf, O.; Solyali, D.; Asmael, M.; Zeeshan, Q.; Safaei, B.; Askir, A. Experimental and simulation study of liquid coolant battery thermal management system for electric vehicles: A review. International journal of energy research 2021, 45, 6495–6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Liu, C.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, P.; Ma, W.; Yue, Y.; Xie, H.; Larkin, L.S. Advanced thermal interface materials for thermal management. Engineered Science 2018, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhao, H.; Niu, H.; Ren, Y.; Fang, H.; Fang, X.; Lv, R.; Maqbool, M.; Bai, S. Highly thermally conductive 3D printed graphene filled polymer composites for scalable thermal management applications. Acs Nano 2021, 15, 6917–6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Gao, B.; Wang, M.; Yuan, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhao, J.; Feng, Y. Strategies for enhancing thermal conductivity of polymer-based thermal interface materials: A review. Journal of Materials Science 2021, 56, 1064–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Jiang, P.; Huang, X. Application-driven high-thermal-conductivity polymer nanocomposites. ACS nano 2024, 18, 3851–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.S.; Perrier, T.; Barani, Z.; Kargar, F.; Balandin, A.A. Thermal interface materials with graphene fillers: review of the state of the art and outlook for future applications. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 142003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akula, R.; Balaji, C. Thermal management of 18650 Li-ion battery using novel fins–PCM–EG composite heat sinks. Applied Energy 2022, 316, 119048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Ma, H.; Hussien, M.A.; Feng, Y. Development and challenges of thermal interface materials: a review. Macromolecular Materials and Engineering 2021, 306, 2100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, B. Interfacial thermal resistance: Past, present, and future. Reviews of Modern Physics 2022, 94, 025002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Wei, N.; Yang, J.; Pei, Q.X. Recent progress in the development of thermal interface materials: a review. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2021, 23, 753–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahil, K.M.; Balandin, A.A. Graphene–multilayer graphene nanocomposites as highly efficient thermal interface materials. Nano letters 2012, 12, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghibi, S.; Kargar, F.; Wright, D.; Huang, C.Y.T.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Barani, Z.; Salgado, R.; Balandin, A.A. Noncuring graphene thermal interface materials for advanced electronics. Advanced Electronic Materials 2020, 6, 1901303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Han, D.; Zhao, Y.H.; Bai, S.L. High-performance thermal interface materials consisting of vertically aligned graphene film and polymer. Carbon 2016, 109, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Choi, W. Hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets/graphene nanoplatelets/cellulose nanofibers-based multifunctional thermal interface materials enabling electromagnetic interference shielding and electrical insulation. Carbon 2024, 228, 119397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D. Performance of thermal interface materials. Small 2022, 18, 2200693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Lloyd, J.R. Enhancement of thermal energy transport across graphene/graphite and polymer interfaces: a molecular dynamics study. Advanced Functional Materials 2012, 22, 2495–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, J.; Jiang, W.; Nie, X. Massive enhancement in the thermal conductivity of polymer composites by trapping graphene at the interface of a polymer blend. Composites Science and Technology 2016, 129, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.F. Thermal conductivity of graphene-polymer composites: Mechanisms, properties, and applications. Polymers 2017, 9, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zeng, J.; Zhai, S.; Xian, Y.; Yang, D.; Li, Q. Thermal properties of graphene filled polymer composite thermal interface materials. Macromolecular Materials and Engineering 2017, 302, 1700068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.H.; Liu, J.; Shu, C.; Zhang, S.C.; Zhao, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Z.Z.; Li, X. Densifying conduction networks of vertically aligned carbon fiber arrays with secondary graphene networks for highly thermally conductive polymer composites. Advanced Functional Materials 2025, 35, 2417324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, L.; Yan, Q.; Yu, J.; Jiang, N.; Lin, C.T. 2D materials-based thermal Interface materials: structure, properties, and applications. Advanced Materials 2024, 36, 2311335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Han, S.; Dan, C.; Wu, T.; You, F.; Jiang, X.; Wu, Y.; Dang, Z.M. Boron Nitride-Polymer Composites with High Thermal Conductivity: Preparation, Functionalization Strategy and Innovative Structural Regulation. Small 2025, p. 2412447. [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; An, L.; Yu, L.; Pan, Y.; Fan, H.; Qin, L. Strategies for optimizing interfacial thermal resistance of thermally conductive hexagonal boron nitride/polymer composites: A review. Polymer Composites 2024, 45, 10587–10618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Huang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Pan, G.; Sun, J.; Zeng, X.; Sun, R.; Xu, J.B.; Song, B.; Wong, C.P. Polymer composite with improved thermal conductivity by constructing a hierarchically ordered three-dimensional interconnected network of BN. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2017, 9, 13544–13553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, V.; Varrla, E. Sustainable high-yield h-BN nanosheet production by liquid exfoliation for thermal interface materials. RSC Applied Interfaces 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhan, K.; Ding, S.; Zhu, J.; Liu, M.; Fan, W.; Duan, P.; Luo, K.; Ding, B.; Liu, B.; et al. A Malleable Composite Dough with Well-Dispersed and High-Content Boron Nitride Nanosheets. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 4886–4895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Pei, Y.; Chen, C.; Jiang, B.; Yao, Y.; Xie, H.; Jiao, M.; Chen, G.; Li, T.; Yang, B.; et al. General, Vertical, Three-Dimensional Printing of Two-Dimensional Materials with Multiscale Alignment. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 12653–12661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Ding, A.; Xu, P.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, P.; Chen, A.; et al. Thermal conductivity of epoxy composites containing 3D honeycomb boron nitride filler. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 489, 151170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Sun, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, P. Vertically Aligned and Interconnected Boron Nitride Nanosheets for Advanced Flexible Nanocomposite Thermal Interface Materials. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017, 9, 30909–30917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Jung, Y.H.; Lee, J.S.; Jeong, C.; Kim, J.U.; Lee, S.; Ryu, H.; Kim, H.; Ma, Z.; Kim, T. Anisotropic Thermal Conductive Composite by the Guided Assembly of Boron Nitride Nanosheets for Flexible and Stretchable Electronics. Advanced Functional Materials 2019, 29, 1902575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhu, W.; Deng, Y.; Hai, F.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z. Enhanced through-plane thermal conductivity and high electrical insulation of flexible composite films with aligned boron nitride for thermal interface material. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2019, 127, 105654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Wang, T.; Xiang, D. Efficient construction of boron nitride network in epoxy composites combining reaction-induced phase separation and three-roll milling. Composites Part B: Engineering 2020, 198, 108232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Li, W.; Zhu, S.; Chu, Z.; Gan, W. 3D-network of hybrid epoxy-boron nitride microspheres leading to epoxy composites of high thermal conductivity. Journal of Materials Science 2022, 57, 11698–11713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Shi, J. Preparation of a 3D BN network structure by a salt template assisted method filled with epoxy resin to obtain high thermal conductivity nanocomposites. Polymer Composites 2023, 44, 3610–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X.; Xiao, C.; Chen, L.; Su, Z.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, X.; Tian, X. An efficient approach for constructing 3-D boron nitride networks with epoxy composites to form materials with enhanced thermal, dielectric, and mechanical properties. High Performance Polymers 2019, 31, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.W.; Kim, J.M.; Yoon, H.W.; Nam, K.M.; Kwon, Y.E.; Jeong, S.; Baek, Y.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Chang, S.J.; Yi, G.R.; et al. Solution-processable thermally conductive polymer composite adhesives of benzyl-alcohol-modified boron nitride two-dimensional nanoplates. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 361, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Hu, J.; Liao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Wei, S.; Li, Z. Improved out-of-plane thermal conductivity of boron nitride nanosheet-filled polyamide 6/polyethylene terephthalate composites by a rapid solidification method. Materials Advances 2023, 4, 1490–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Gao, W.; Bai, H. Isotropically Ultrahigh Thermal Conductive Polymer Composites by Assembling Anisotropic Boron Nitride Nanosheets into a Biaxially Oriented Network. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 18959–18967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, K.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, Z.; et al. Low thermal contact resistance boron nitride nanosheets composites enabled by interfacial arc-like phonon bridge. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lim, J.; Yan, W.; Guo, F.; Liang, Y.; Chen, H.; Lambourne, A.; Hu, X. Salt template assisted BN scaffold fabrication toward highly thermally conductive epoxy composites. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 16987–16996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; Li, Q.; Zhang, W.; Dong, J.; Su, F.; Murugadoss, V.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Naik, N.; Guo, Z. Highly thermal conductive epoxy nanocomposites filled with 3D BN/C spatial network prepared by salt template assisted method. Composites Part B: Engineering 2021, 209, 108609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; et al. Ultra-high thermal conductivity multifunctional composites with uniaxially oriented boron nitride sheets for future wireless charging technology. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials 2025, 8, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Gong, W.; Tian, W.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Hu, M.; Fan, X.; Yao, Y. Hot-pressing induced alignment of boron nitride in polyurethane for composite films with thermal conductivity over 50 W/mK. Composites Science and Technology 2018, 160, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, V.; Chandrashekar, A.; Prabhu, T.N.; Varrla, E. SPI-modified h-BN nanosheets-based thermal interface materials for thermal management applications. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2024, 16, 34367–34376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Chen, S.; Li, P. Lithium-ion battery pack thermal management under high ambient temperature and cyclic charging-discharging strategy design. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 80, 110391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Cockerill, T.; de Boer, G.; Voss, J.; Thompson, H. Heat Transfer Modeling and Optimal Thermal Management of Electric Vehicle Battery Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Wang, C.Y. Power and thermal characterization of a lithium-ion battery pack for hybrid-electric vehicles. Journal of power sources 2006, 160, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; White, R.E. Mathematical modeling of a lithium ion battery with thermal effects in COMSOL Inc. Multiphysics (MP) software. Journal of Power Sources 2011, 196, 5985–5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.; Wang, C.Y. Analysis of electrochemical and thermal behavior of Li-ion cells. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2002, 150, A98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weragoda, D.M.; Tian, G.; Burkitbayev, A.; Lo, K.H.; Zhang, T. A comprehensive review on heat pipe based battery thermal management systems. Applied thermal engineering 2023, 224, 120070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).