1.1. Motivation

In the new era of the highly developed society, the demand for energy has been increasing with the emergence of industrialization and the integration of information technology. A global shift towards more sustainable and environmentally friendly energy solutions is ongoing, particularly in the area of energy storage.

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have appeared as a key technology to meet these demands due to their high energy density, efficiency, long cycle life, and environmental compatibility. They have already become the backbone of many electronic devices and are increasingly being used in electric vehicles (EVs) and grid-scale energy storage systems, contributing significantly to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Despite their widespread adoption, LIBs have also brought safety issues such as thermal runaway (TR), which can lead to serious safety risks such as fires and explosions. [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]

Thermal runaway is a critical phenomenon where a battery cell undergoes an uncontrollable increase in temperature, triggering a cascade of exothermic reactions that rapidly liberate substantial energy in a short duration. This can result in a significant increase in temperature and pressure, which can lead to an explosion or fire [

1,

2,

3,

4,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. During TR, the increase in battery temperature not only causes electrolyte evaporation [

19], but also triggers reactions that produce a large volume of gases [

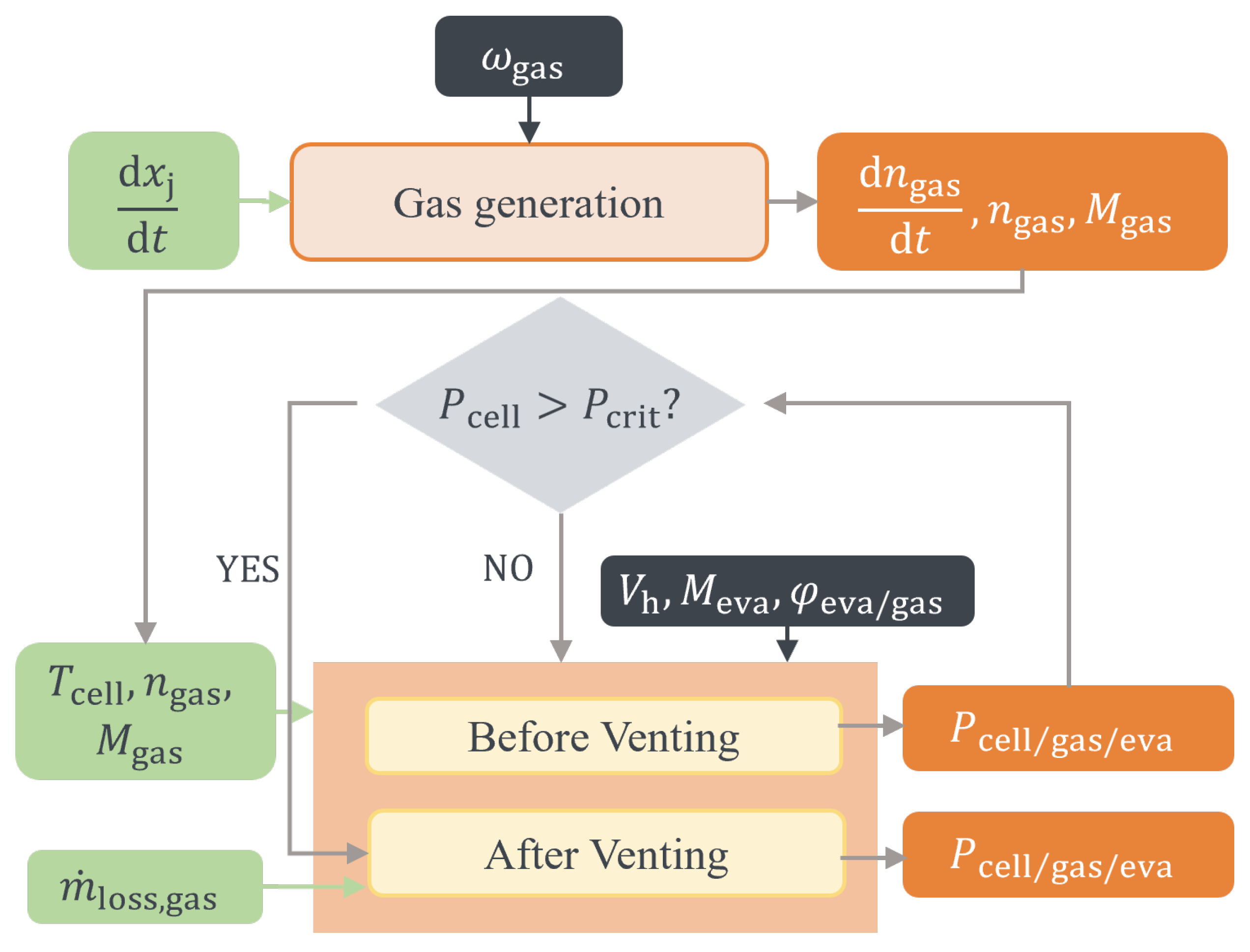

20]. This combination can result in a sharp increase in internal pressure, leading to expansion of the battery casing.

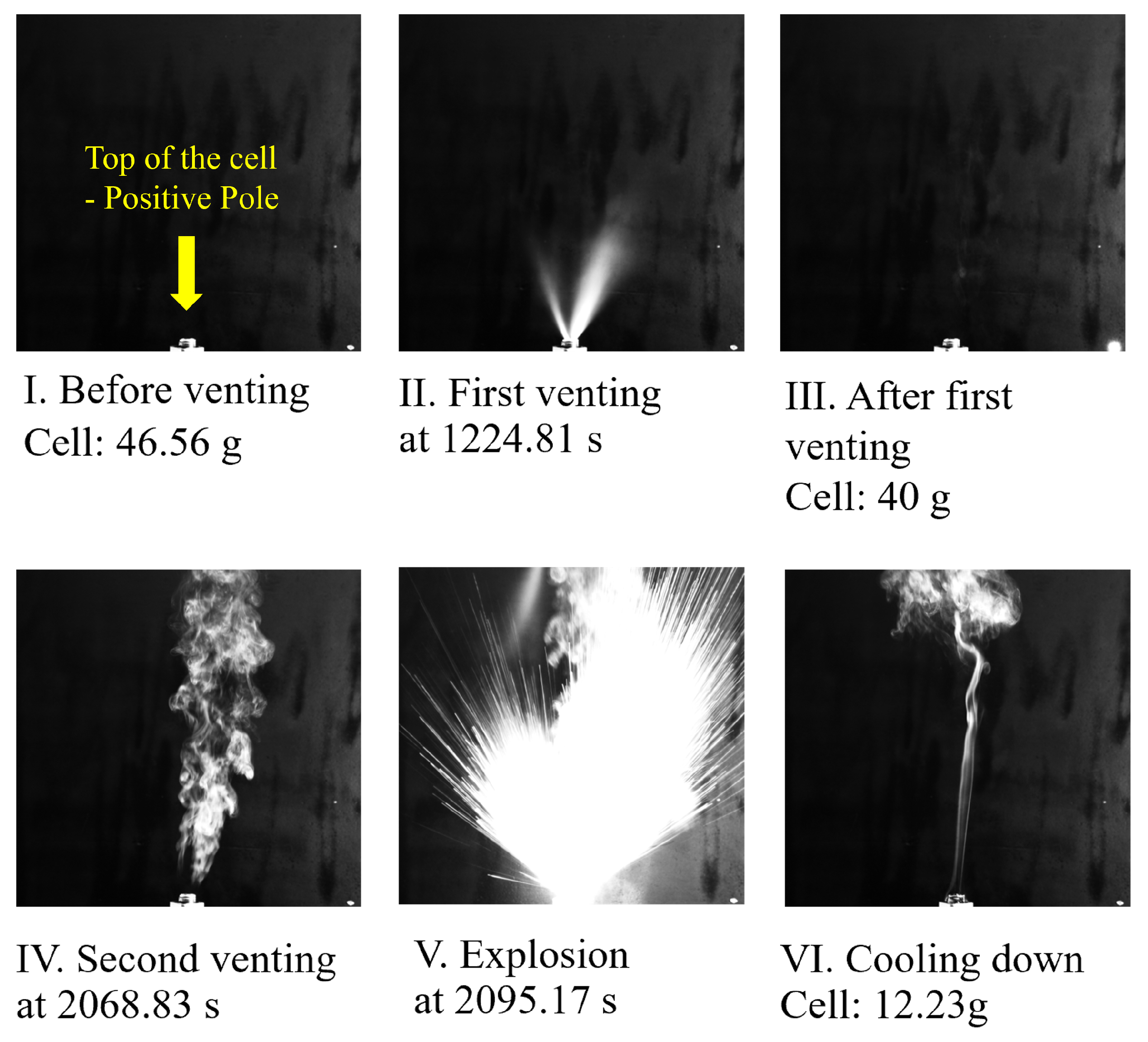

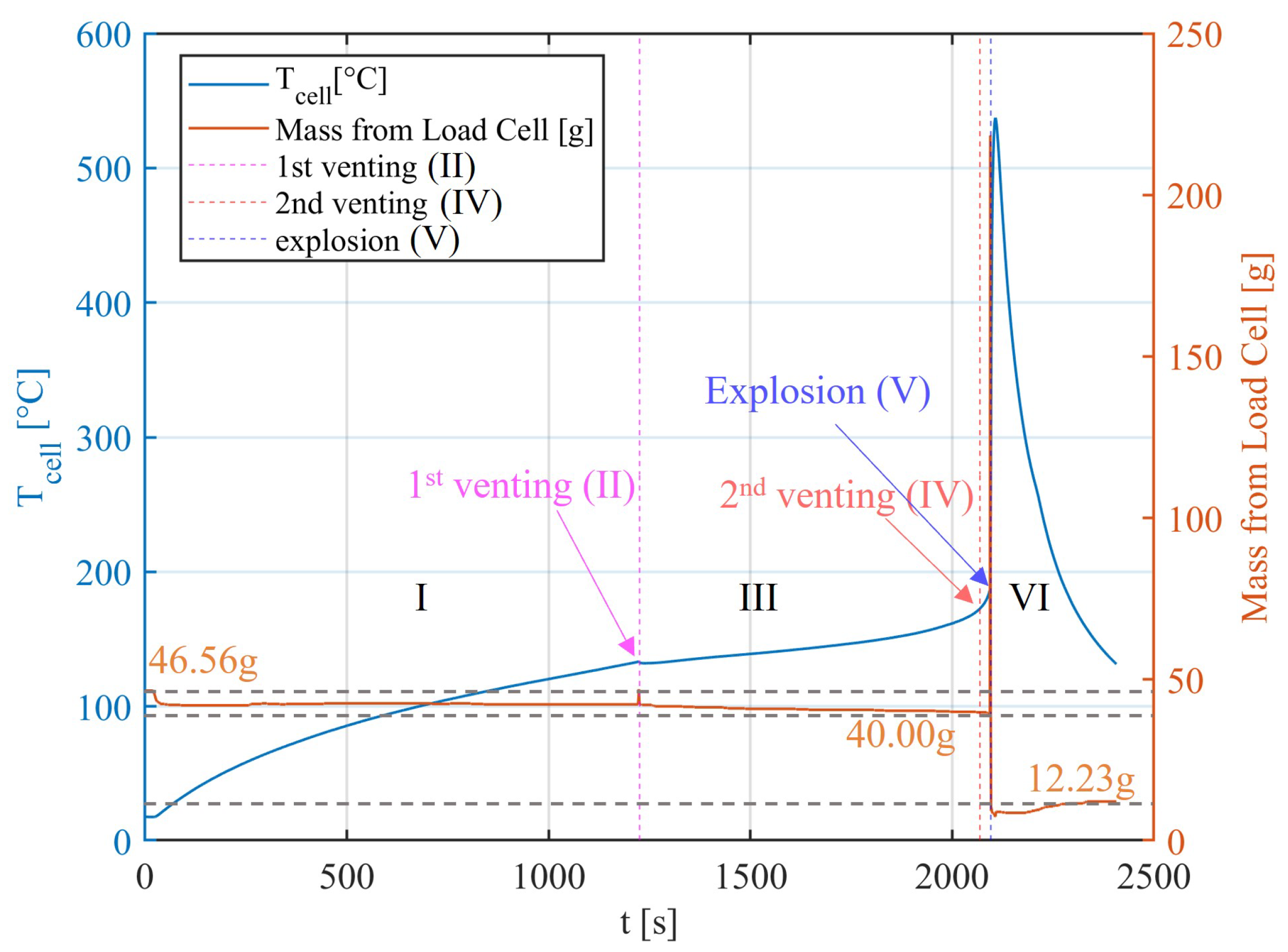

The venting process is a critical safety feature designed to mitigate the pressure build-up within a battery cell during TR [

19,

21]. As the internal pressure reaches a critical threshold in a battery equipped with a safety vent valve, this valve opens, releasing a mixture of electrolyte vapors, reactive gases, and solid particles into the surrounding environment [

22]. In the absence of the vent valve, a feature often omitted in pouch cell designs, the mixture typically leaks and bursts from the sealant edges of the battery [

21]. Together with the previous evaporation stage, this whole process consumes energy and partly cools the battery [

19]. However, it often cannot stop the process of TR, where the cell temperature continues to rise steeply. The high temperature and substantial proportion of flammable gas in the resulting mixture often lead to a second venting eruption in the form of explosions and fires, appearing as jet flames [

23]. The cell loses the most material during this process and shows a peak of its temperature. After consuming or losing the major mass of its active material, the TR reaches an end, where the battery is cooled by the ambient environment.

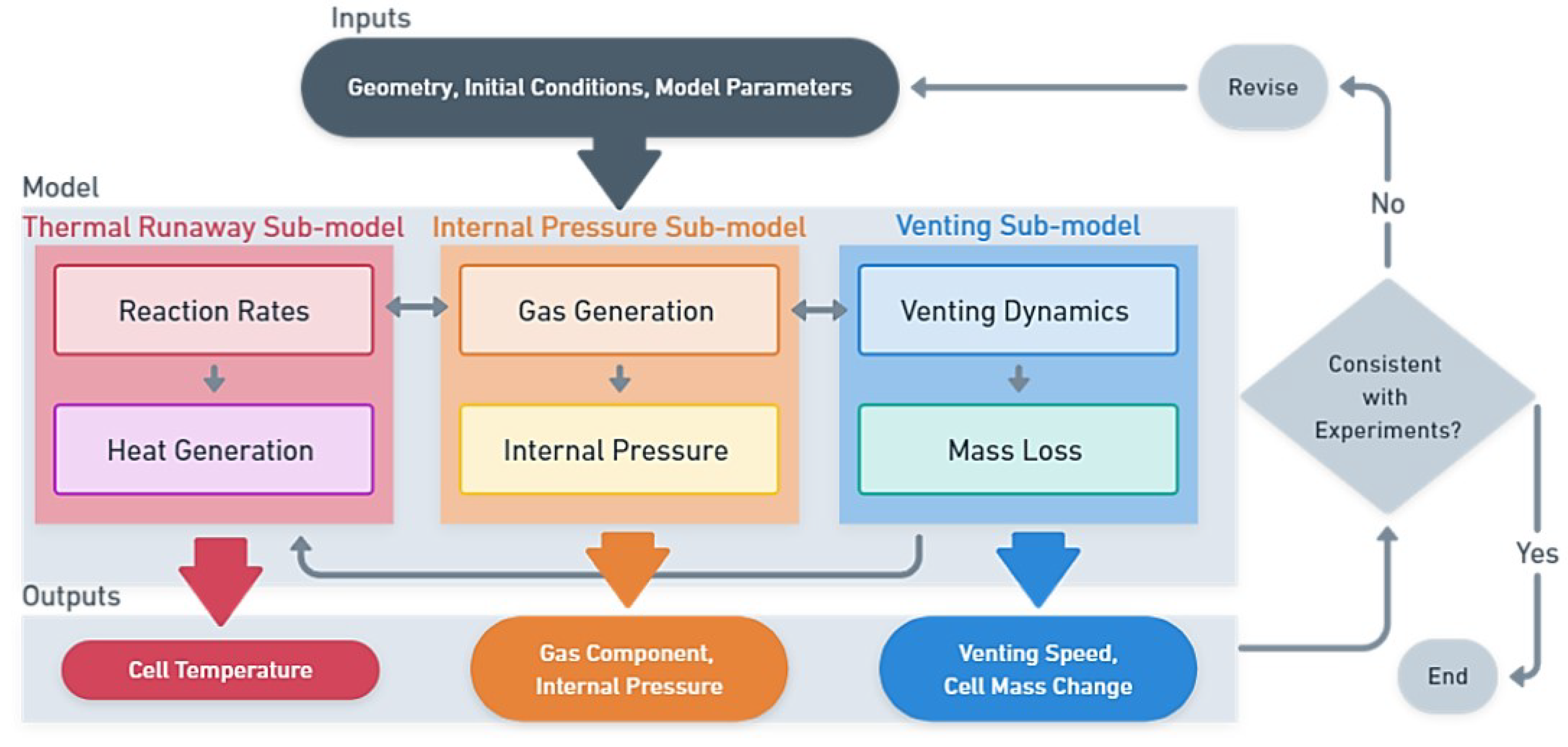

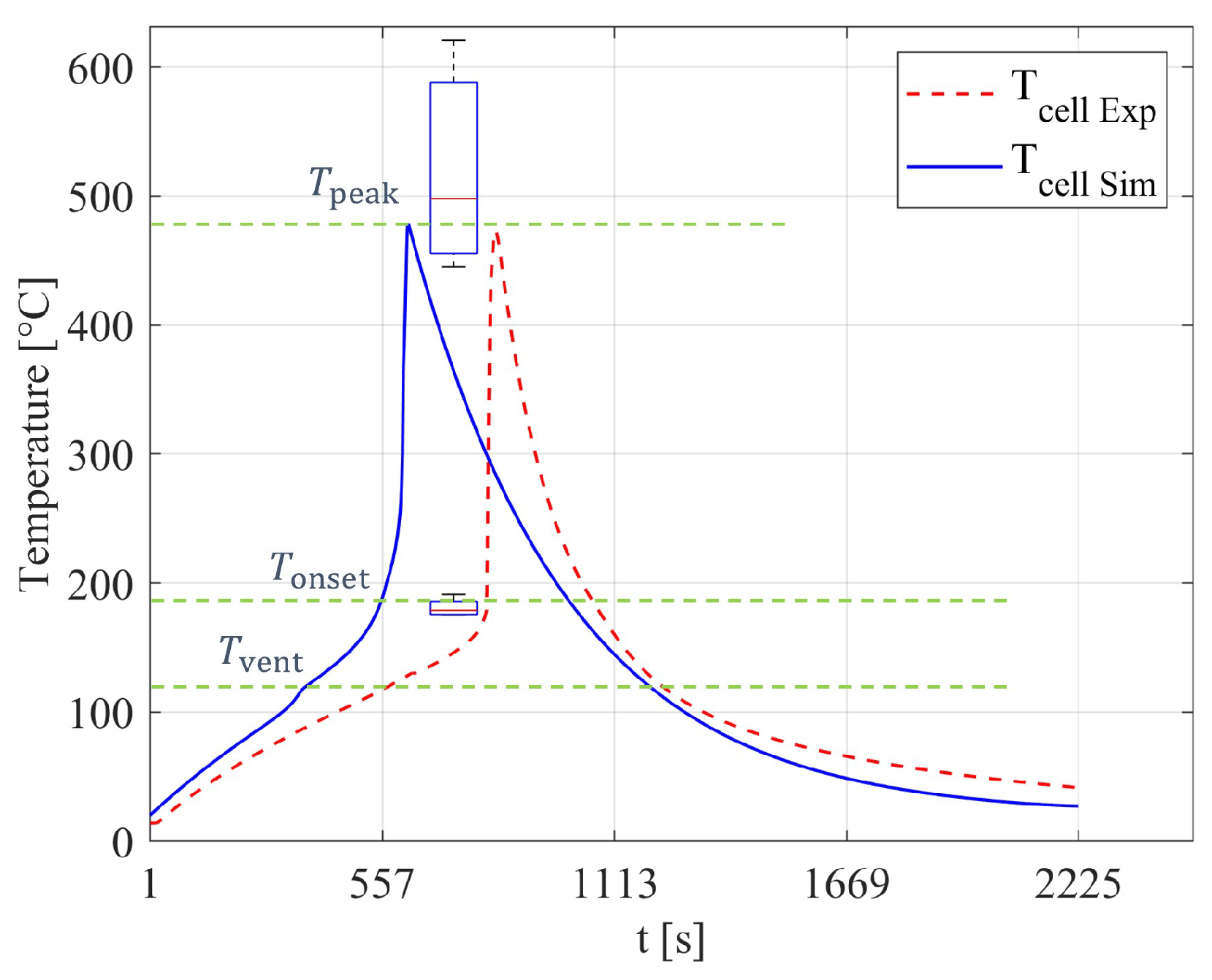

To optimize the cell and battery design in terms of safety and to gain a further understanding, models are useful tools. Therefore, accurate modeling of the venting process and mass loss is crucial for predicting the behavior of LIBs during TR and for developing strategies to lower the risks of causing greater hazard.

1.2. Relevant Literature

Several studies have made significant contributions to the understanding and prediction of TR [

2,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] and venting in LIBs [

5,

7,

19,

21,

23,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. A review of the literature related to the modeling of TR and venting with their purpose and researched parameters is shown in

Table 1. Researchers first focused on revealing the mechanism of TR by experimental studies and numerical modeling. Richard and Dahn [

8,

9] investigated the thermal stability of lithium-ion cells, focusing on lithiated mesocarbon microbead (MCMB) material in various electrolytes under adiabatic conditions. Utilizing an accelerated rate calorimetry (ARC), the study explored the effects of lithium content, electrode surface area, electrolyte type, and initial heating temperature on the thermal stability of these materials. Based on the acquired data, the exothermic reaction kinetics of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer’s decomposition and regeneration during TR on the negative electrode has been characterized, leading to the development of a simple lumped model to predict TR events. Following that, Hatchard et al. [

12] have introduced a more comprehensive one-dimensional thermal model incorporating the TR reactions in the positive electrode, which was based on oven exposure testing and was used for assessing the effectiveness of cell designs in heat dissipation. Kim et al. [

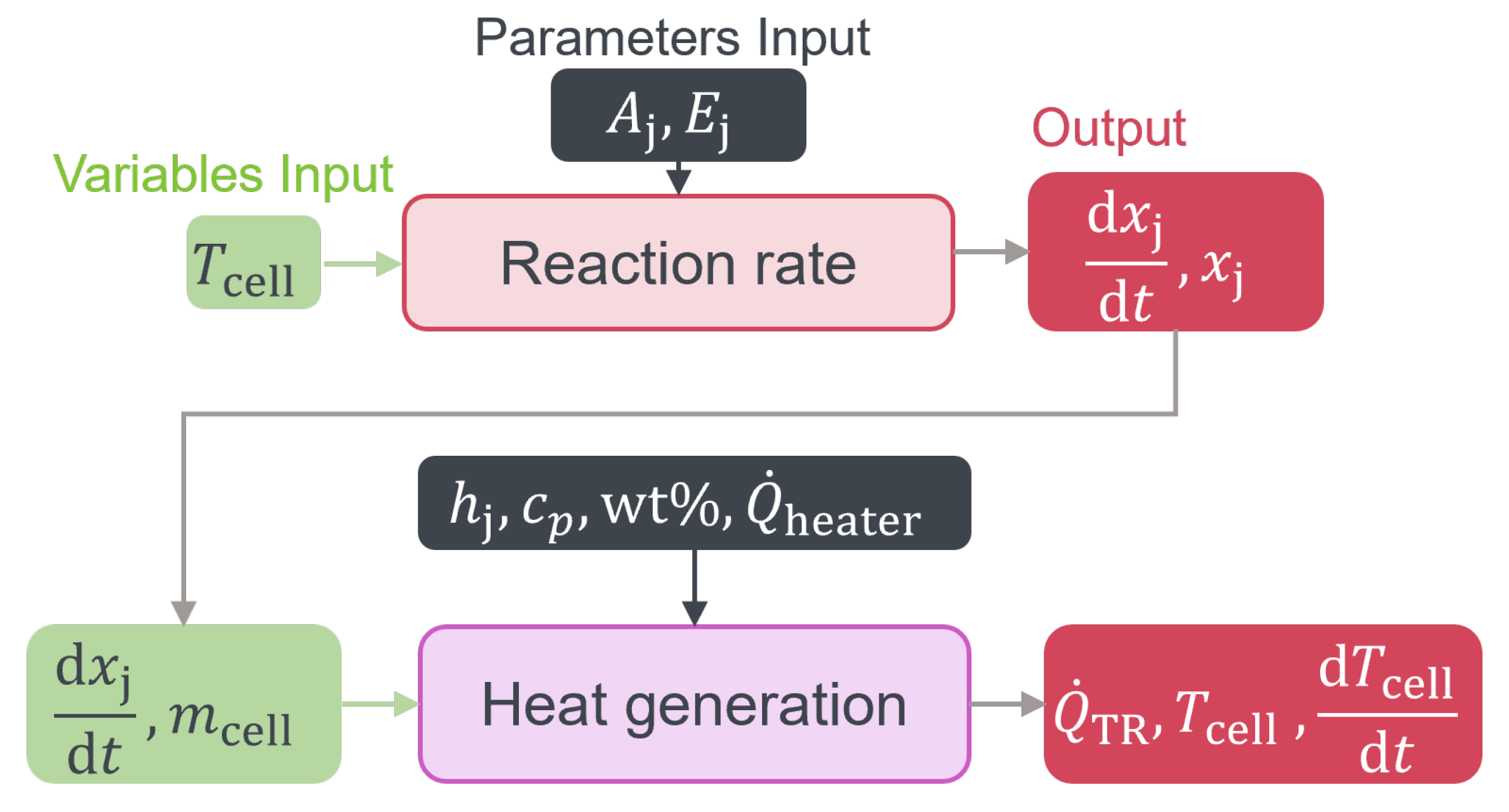

13] marked a significant advancement in TR modeling by moving beyond one-dimensional models to a comprehensive three-dimensional model, and integrating electrolyte and binder decomposition. Their study offered detailed formulations for several potential exothermic reactions within the battery with geometrical features, enabling simulations that reveal how heat propagates through a cell during TR. These research works have mainly focused on the heat generation and temperature change of the battery during TR process, providing a primary understanding to the TR mechanisms.

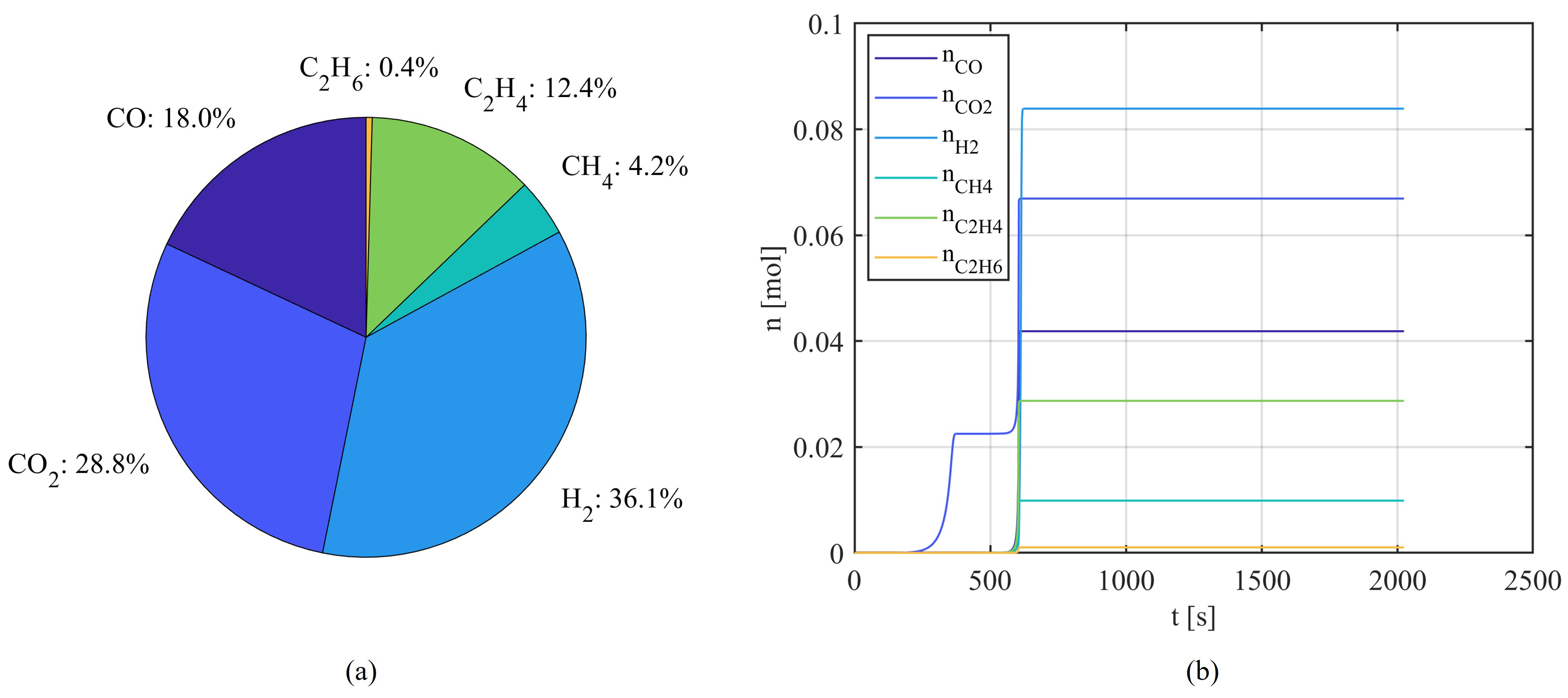

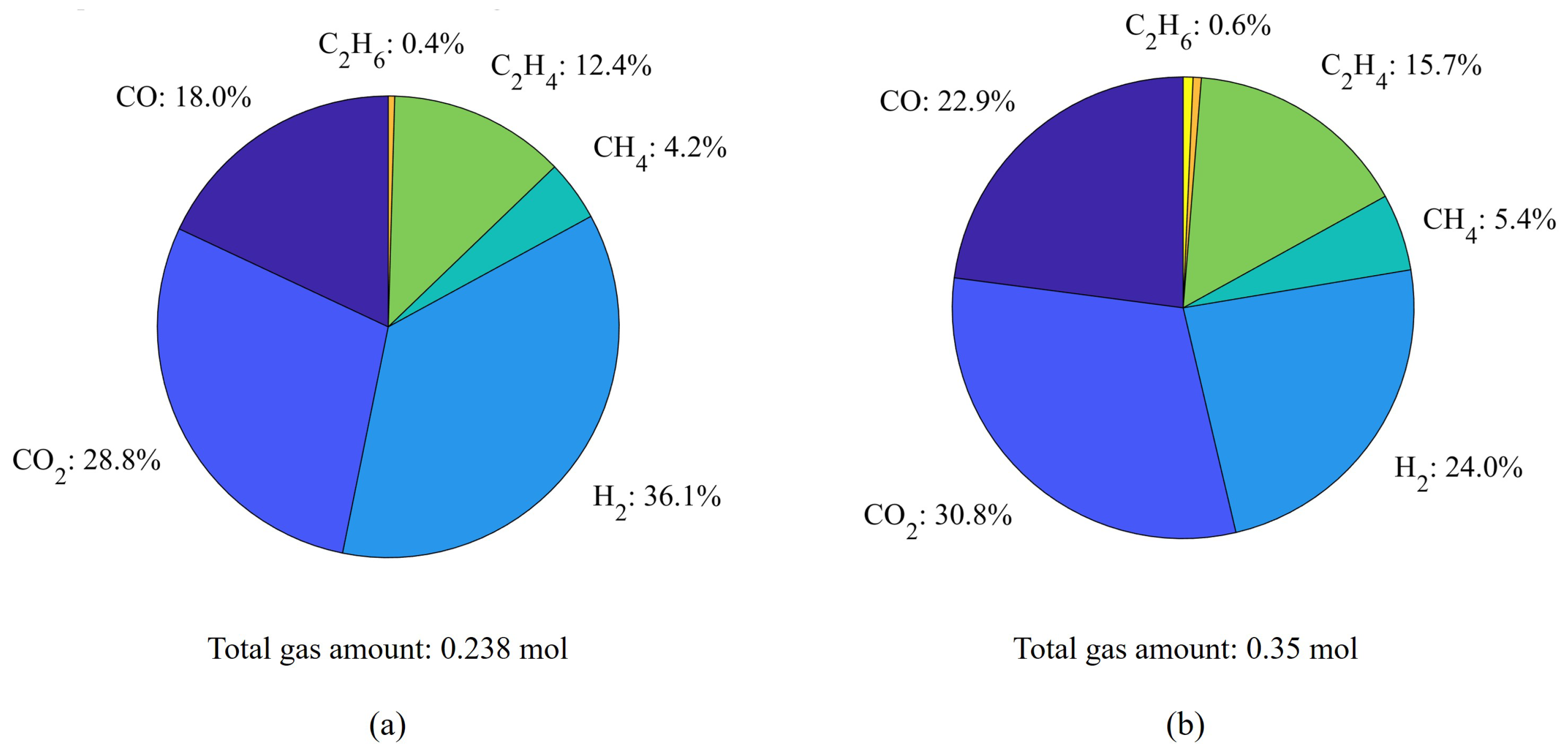

With the deepened study of the TR process, more attention has been paid to more detailed failures from TR. During TR, the rising temperature of the battery not only causes the evaporation of the electrolyte [

19] but also triggers reactions that produce a large volume of flammable or toxic gases, which contributes to the increase of the internal pressure of the cell and can lead to combustion or explosion under higher temperature [

20]. This mechanism has been extensively studied by experiments and quantification work by various researchers [

20,

36,

37,

38]. To first determine the composition of the main generated gases from TR, Golubkov et al. [

20] conducted a series of TR experiments on 18650 LIBs using various cathode materials: a combination of Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide (NMC) and Lithium Cobalt Oxide (LCO), NMC, and Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP), and quantified the gases with gas chromatography (GC) too. Subsequently, they further explored the TR characteristics of two commercially available types of 18650 LFP and Lithium Nickel Cobalt Aluminium Oxides (NCA) cells and estimated the mass inventory based on teardown results [

36]. Shen et al. designed experiments using an adiabatic explosion chamber (AEC) under an inert atmosphere to test prismatic LIBs with LFP and different NMC cathode materials [

37]. Besides the analysis of gas components, they also conducted the calculation of flammability limit based on the generation of

, and thus evaluated the hazard degree of TR from LIBs with different cathodes. These experimental studies have clarified the types and quantities of gases that can be generated during TR in specific types of LIBs, thereby enabling advanced modeling of TR events.

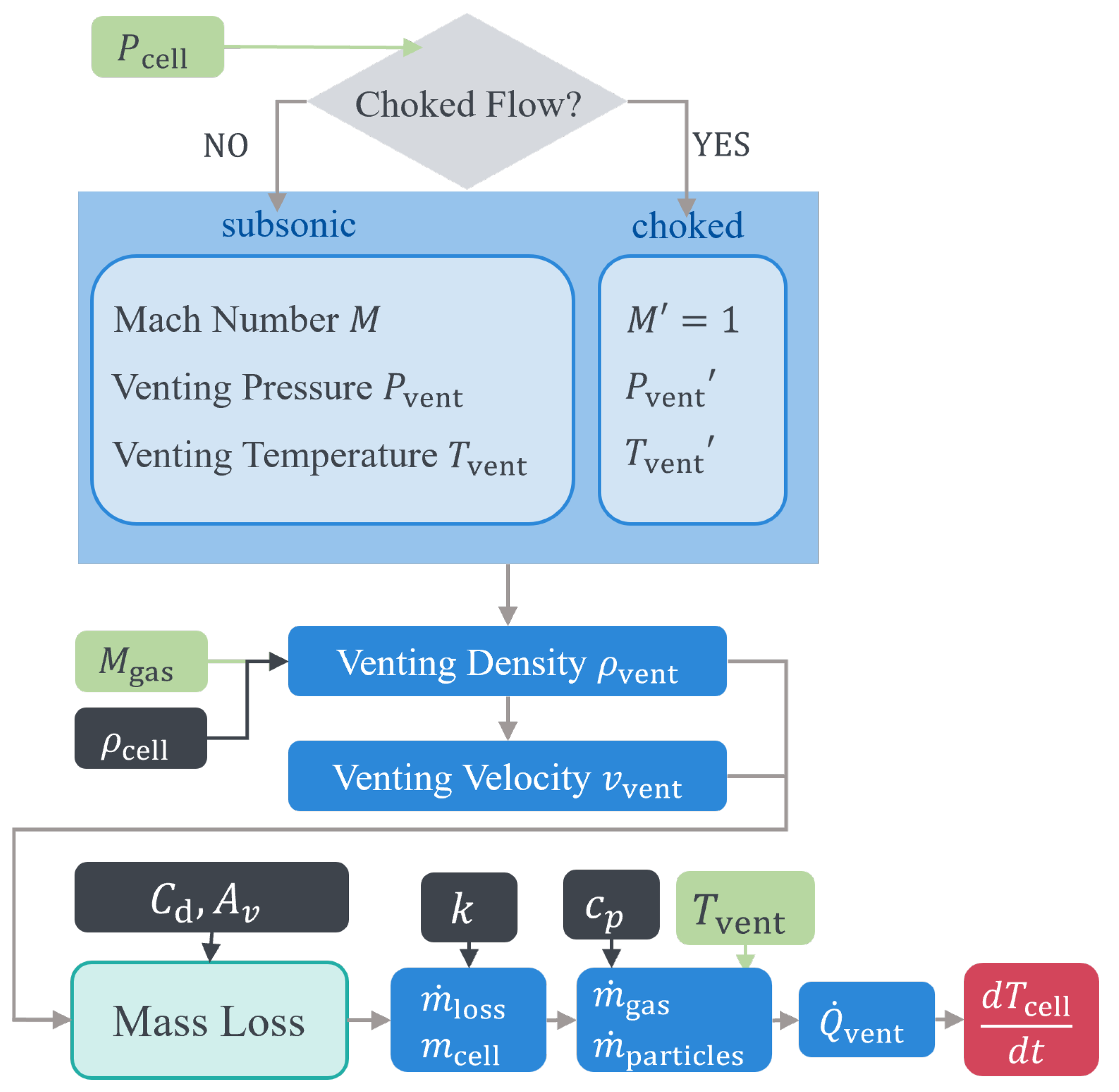

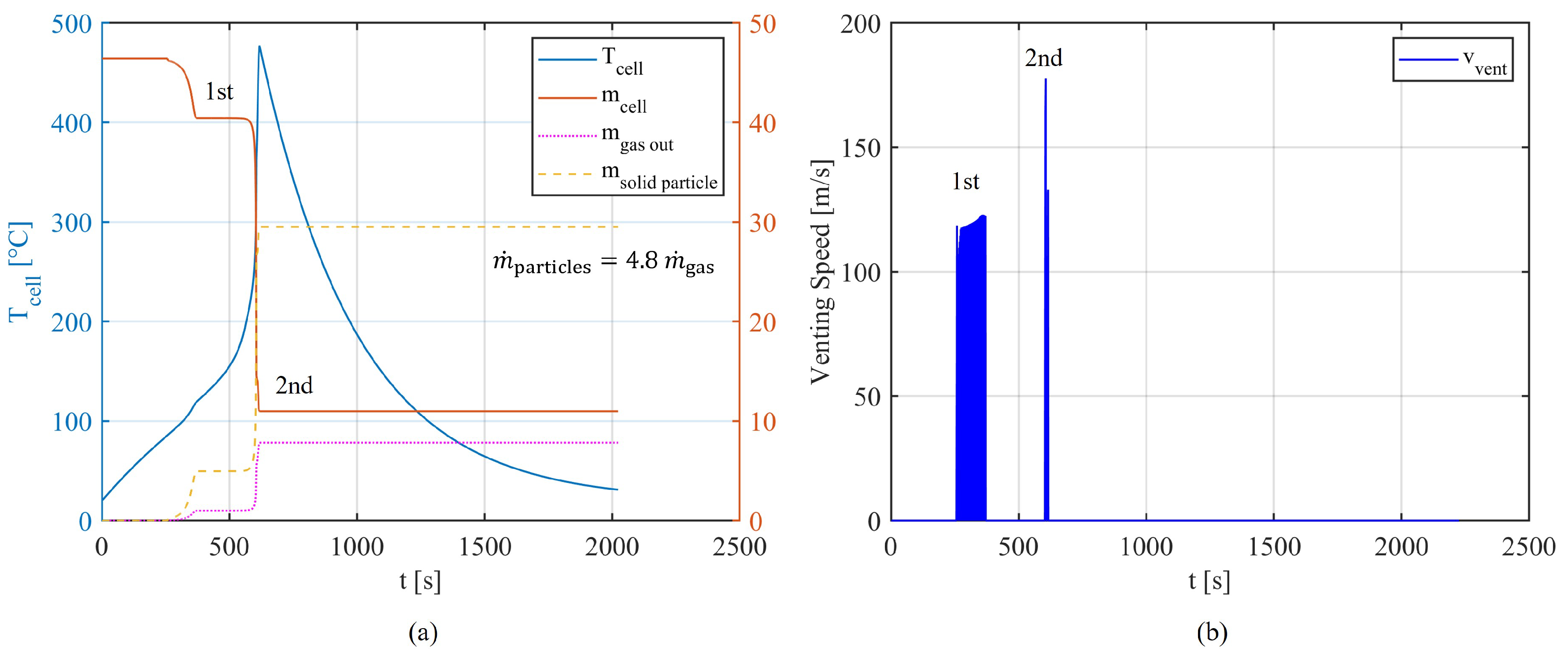

Coman et al. first developed a lumped model for TR in 18650 LIBs, taking into account the evaporation of the electrolyte and the ejection of contents from the jelly roll [

19]. They provided equations to describe the development of internal pressure and venting but also pointed out the difficulty of describing the mass loss directly with equations because of its unpredictability. Therefore, they estimated the mass loss rate based on statistical results from previous experiments. Mao et al. conducted experimental studies in both open environments and combustion chambers to investigate the combustion behavior of 18650 LIBs with NMC 532 cathodes. Their research focuses on the correlation between heat release, mass loss during TR, and the state of charge (SOC) of the LIBs [

39]. Based on this and the estimation of the generated gas components from other experimental studies, they subsequently developed a lumped model to characterize the jet flow and fire dynamics of these LIBs under TR [

23]. Similarly, Kong et al. developed a numerical model based on the assumption of gas generation to describe the venting dynamics and combustion behavior of 18650 LIBs with NCA cathodes. However, their model did not focus on solid particle ejection and mass loss [

7]. Wang’s team addressed this gap with their study by developing a multi-scale model for TR that integrates the ejection of solid particles and mass loss [

22]. They assumed that the mass loss from solid particle ejection is proportional to the total mass loss of the battery and conducted experiments in an open environment for venting flow analysis and in a sealed chamber to characterize the ejected particles.

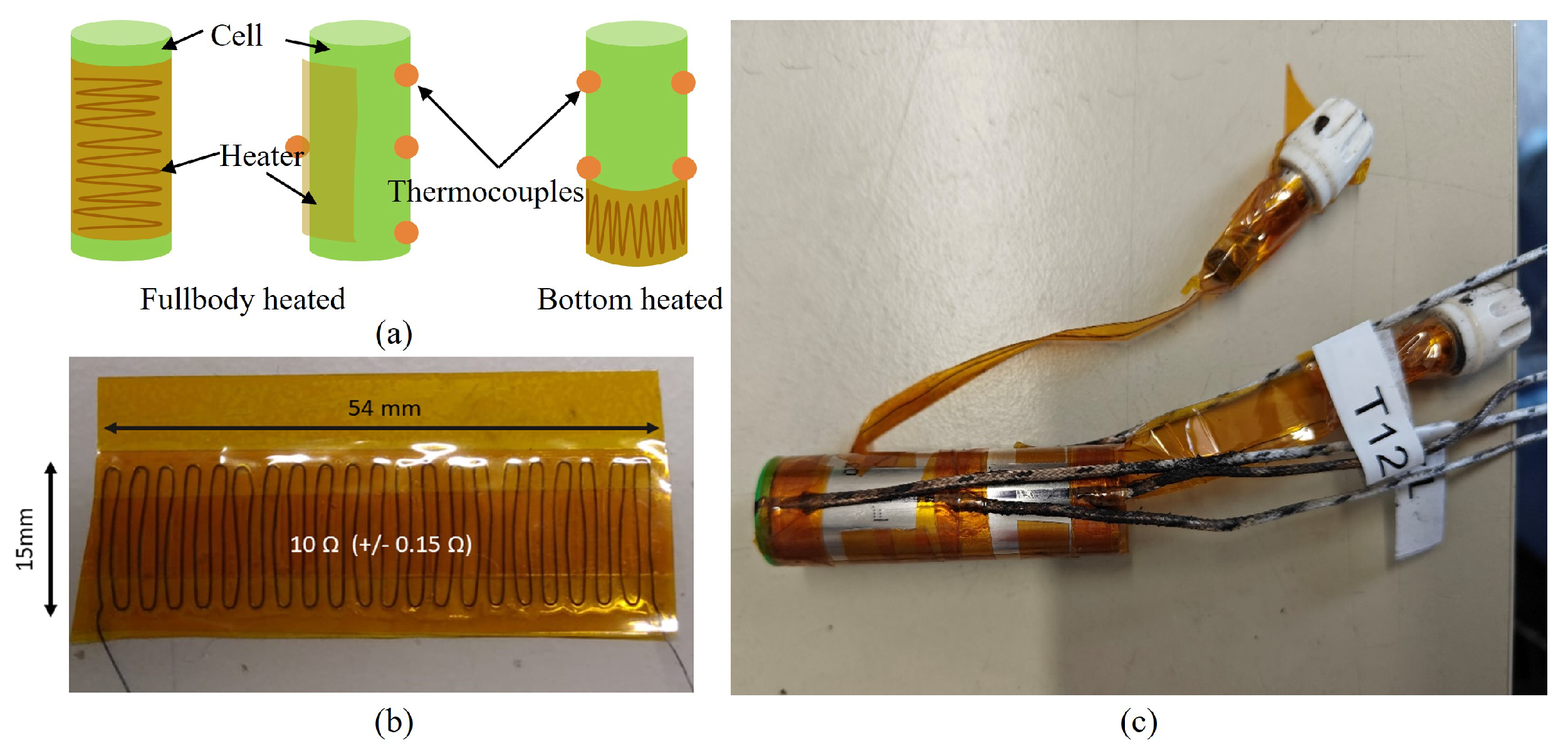

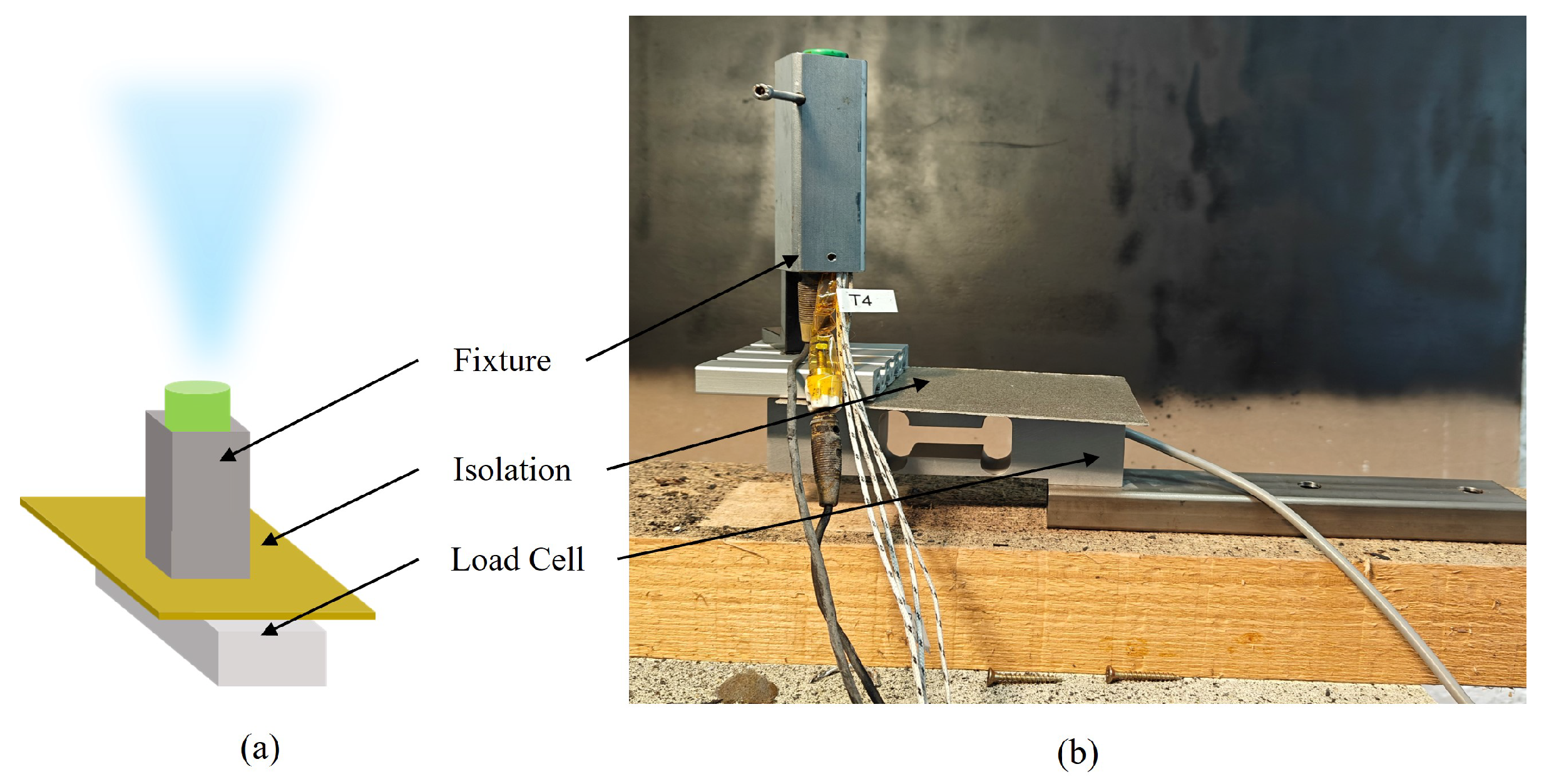

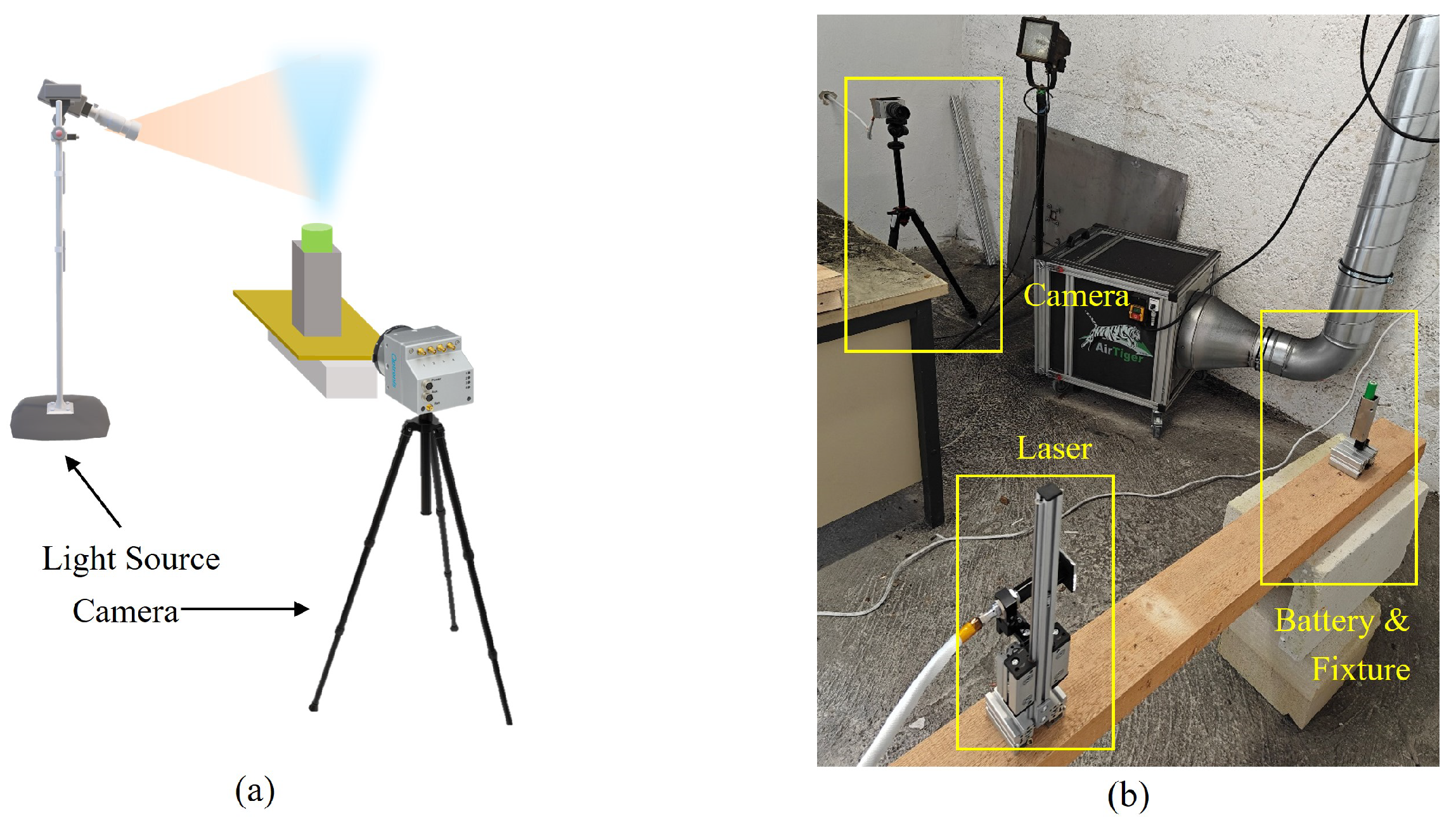

The above literature review clearly indicates that the current trend in the field of TR modeling has shifted from detailing heat generation mechanisms to predicting TR behavior. While thermal behavior, such as temperature change and heat release, remain primary focuses, there is growing attention to venting and combustion behavior, including gas generation and release, particle ejection, venting flow dynamics, and mass loss rate in recent years. To characterize and quantify the venting behavior of cylindrical LIBs and sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) during TR events, Fedoryshyna et al. developed a custom test bench equipped with shear force sensors and a high-speed camera to capture detailed data on venting dynamics, including gas velocity, mass flow rate, and temperature variations [

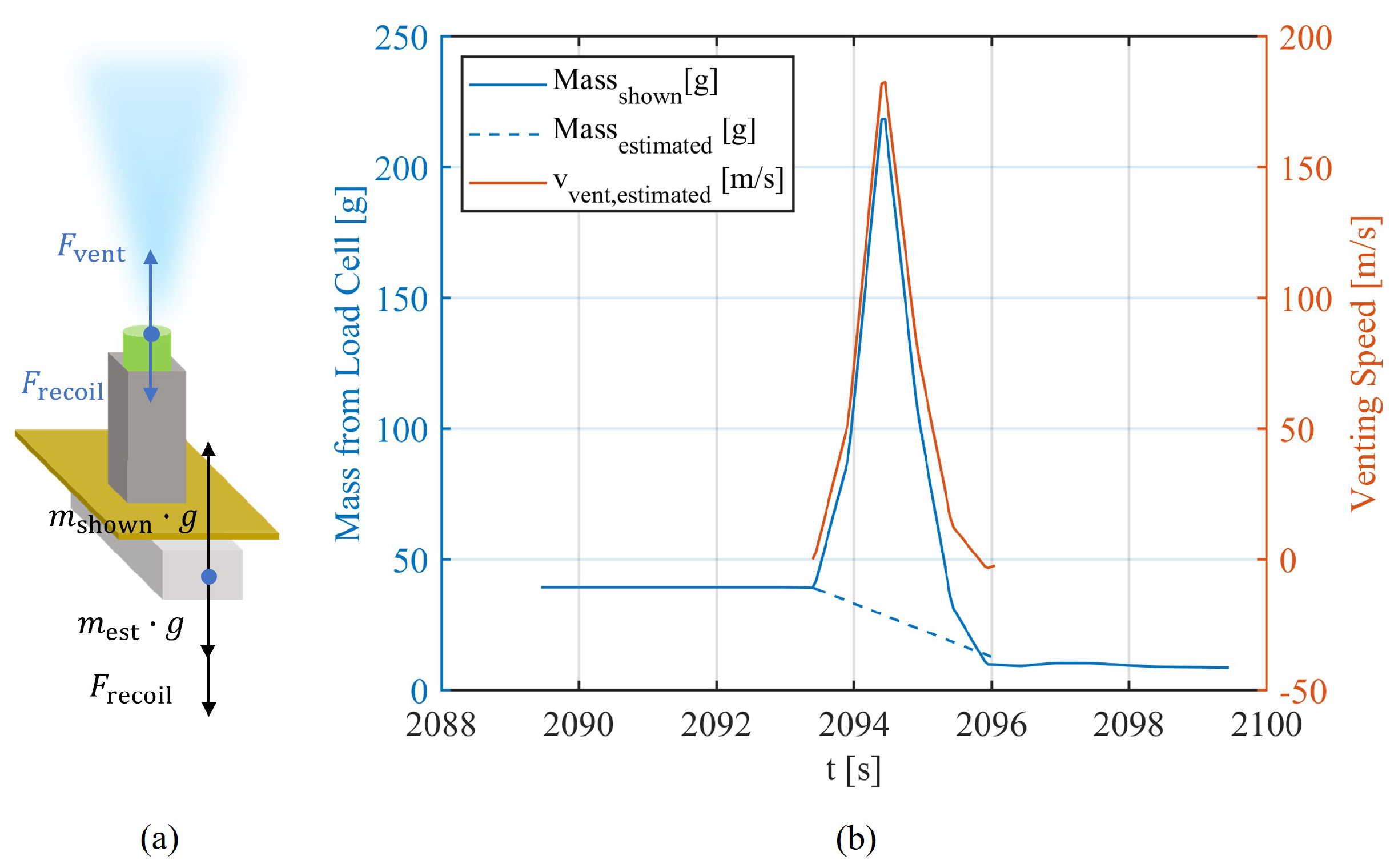

33]. They tested 21700 and 18650 LIBs with NMC811/SiC chemistry and 18650 SIBs with

/HC chemistry, all at a 100 % SOC. TR was triggered through continuous heating, and measurements focused on gas ejection velocity, recoil force, venting gas temperature, and mass loss during TR. Gillich et al. also developed a mechanical measurement approach to analyze venting behavior during TR in 18650 LIBs [

34]. Using a 3-axis force sensor and high-frequency data logging, the setup enables precise measurements of recoil force and gas flow rates during TR in both high-power and high-energy 18650 cells.

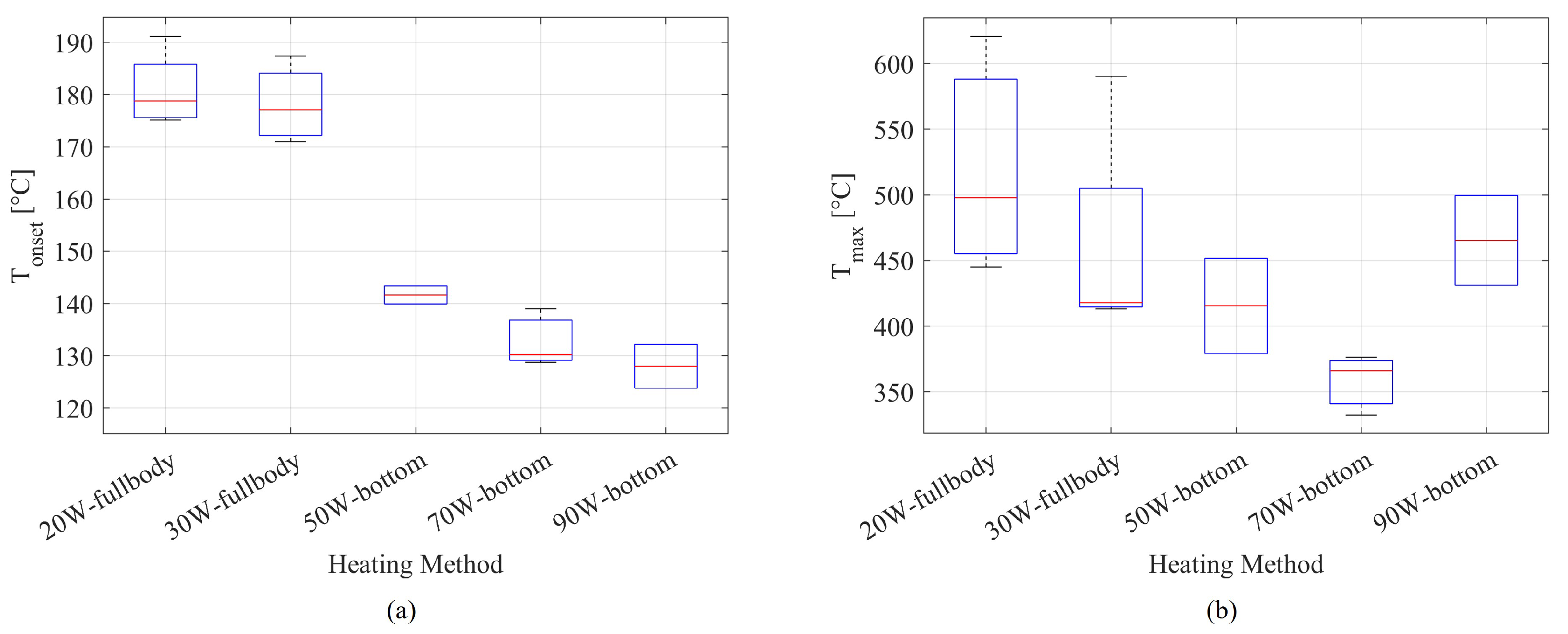

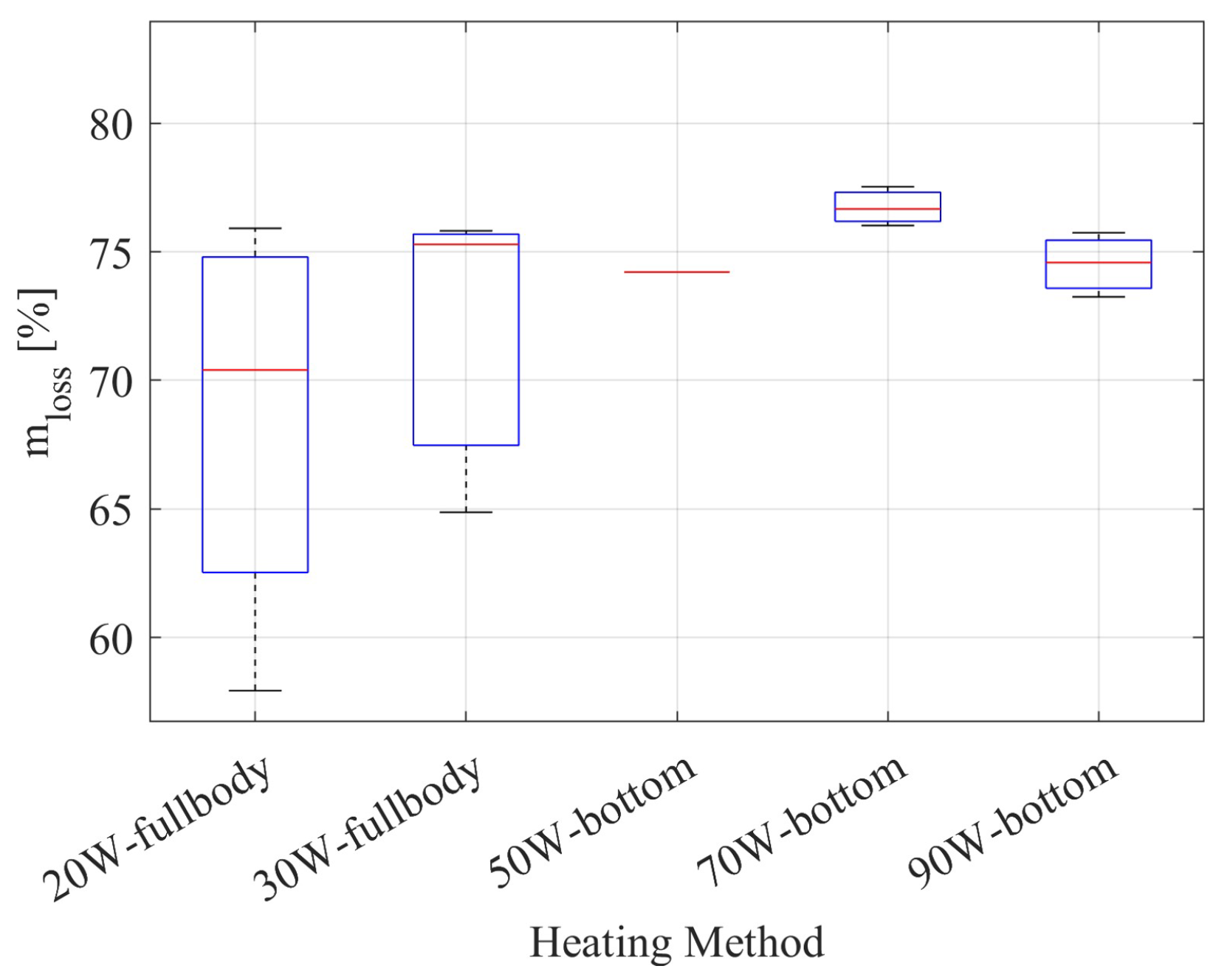

Among these, predicting particle ejection and mass loss rate poses the greatest difficulties due to the randomness of ejection and explosion, which also brings challenges to the reliability of the experiments for validation [

40]. Therefore, the impact of the experiment setup on the TR and venting process has also become a study focus, including the triggering method of TR, the SOC, the cell format etc. Willstrand et al. investigated how test setups, SOC, and trigger methods influence the TR characteristics and gas release in large-format lithium-ion cells (157 Ah) [

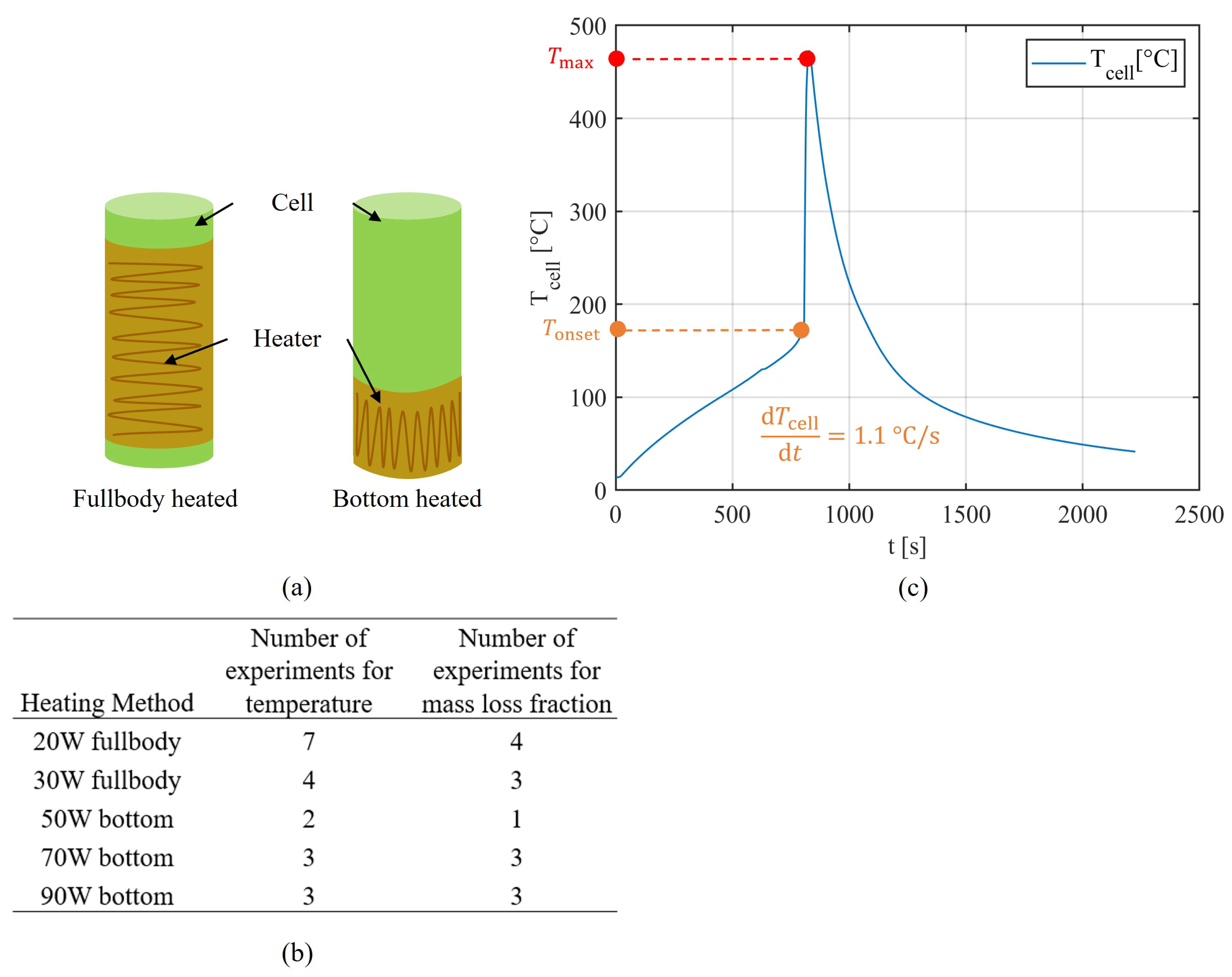

40]. They conducted 37 tests on large-format prismatic cells in both closed and open setups with six trigger methods, including heating, local heating, nail penetration, overcharge, and external fire, and with varied SOC levels. Their test results demonstrated a significant impact from various TR trigger methods and different SOC levels, particularly on gas production rate, mass loss, and peak temperatures. They also noted that the trigger methods did not notably influence the total gas generation or gas composition, and the heating rate had minimal effect on the TR onset temperature.