1. Introduction

Distal radial–ulnar fractures are common in toy-breed dogs and have traditionally been managed with surgical fixation. However, in breeds such as Toy Poodles and Pomeranians, the extremely small bone diameter and minimal soft tissue coverage make surgery technically demanding and prone to delayed or failed union [1–3]. Conventional casting, meanwhile, has limited indications and is generally unsuitable for complete fractures of the radius and ulna [4–6]. Both approaches require prolonged activity restriction, thereby reducing quality of life (QOL) for patients and increasing the burden on owners [4–6].

To overcome these limitations, we developed a patient-specific, custom-made three-dimensional (3D) cast in 2018. This device provides stable immobilization while permitting normal activity, promoting indirect bone healing through physiological axial loading. Importantly, it enables continuous radiographic visualization of the healing process, allowing objective assessment of union.

Although the clinical utility of this method has been previously demonstrated, age-related differences in fracture healing have not been quantitatively or radiographically analyzed in a large clinical population.

Age-dependent variation in bone regeneration has been well documented in humans and laboratory animals [7–9,14–16]; however, comparable large-scale clinical studies in dogs are scarce, particularly those conducted under a standardized treatment protocol.Clinically, fracture incidence in toy-breed dogs is not evenly distributed but markedly concentrated in Toy Poodles, Pomeranians, and Italian Greyhounds, which are known to have slender forelimbs and delicate bone structures.

Micro-CT analysis has further revealed that these breeds exhibit a reduced bone-volume fraction (BV/TV), thinner and more widely spaced trabeculae, and lower cortical density compared with other small-breed dogs, indicating a structurally fragile architecture [10].

Building upon our previous work, this study integrates radiographic visualization with statistical modeling to elucidate the relationship between age and fracture-healing dynamics in toy-breed dogs. A total of 191 limbs (179 cases) treated with the 3D cast between 2019 and 2025 were retrospectively analyzed. The goal was to establish an age-stratified model of fracture-healing time and to provide an evidence-based prognostic framework that can guide clinical decision-making and age-appropriate treatment strategies in small dogs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This study was a retrospective analysis of clinical cases treated at our hospital between 2019 and 2025. A total of 191 limbs from 179 toy-breed dogs with complete radial and ulnar fractures were included; 12 dogs with bilateral fractures were evaluated as independent fracture units.

Inclusion criteria were complete fracture of the radius and ulna, body weight ≤10 kg, presentation within 7 days after injury, and no previous fracture in the same forelimb [1–6].

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

Previous surgical history (70 limbs, 60 dogs)

Delayed presentation (>7 days) (33 limbs, 31 dogs)

Body weight >10 kg (6 limbs, 6 dogs)

Comminuted fracture (2 limbs, 2 dogs)

Isolated radial or ulnar fracture (11 limbs, 11 dogs)

Lost to follow-up (15 limbs, 15 dogs: near-healed n=5, early discontinuation n=4, long distance ≥180 km n=6)

Handover to another clinic (6 limbs, 6 dogs)

Refracture (5 limbs, 0 dogs; counted by limb because each refracture occurred in a dog already included in the cohort)

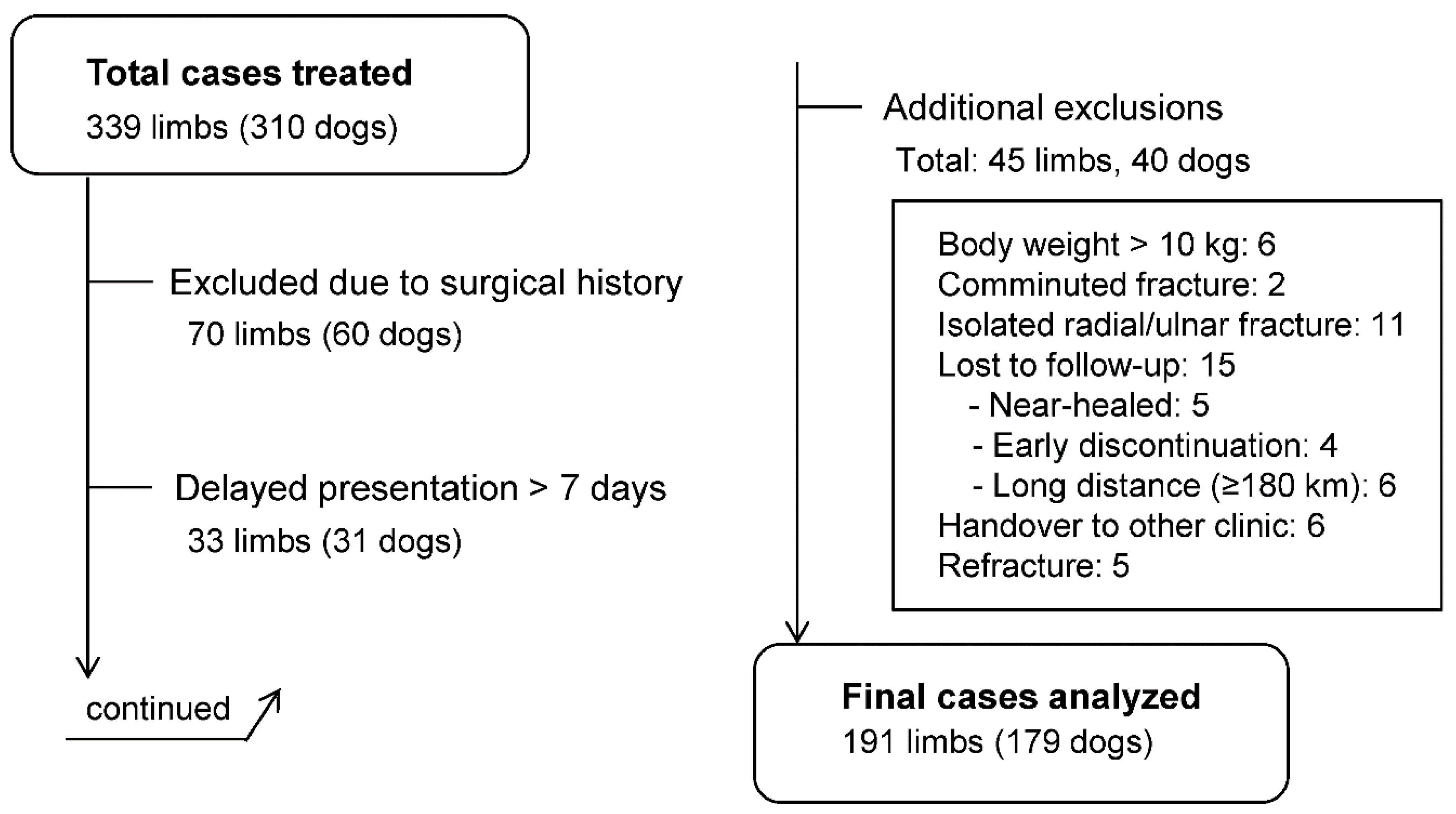

A total of 339 limbs (310 dogs) were initially treated with the 3D cast. After applying the exclusion criteria, 191 limbs (179 dogs) were included for final analysis (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow of case inclusion and exclusion. Among 339 limbs (310 dogs) treated with the 3D cast, 70 were excluded due to surgical history, 33 due to delayed presentation (>7 days), and 45 for other reasons (body weight >10 kg, comminuted fracture, isolated radial/ulnar fracture, lost to follow-up, handover to another clinic, or refracture). Finally, 191 limbs (179 dogs) were included for analysis. Cases with multiple exclusion criteria were categorized by a predefined hierarchy, prioritizing surgical history; cases involving surgical complications inherently included delayed presentation and were therefore classified under “surgical complications.”.

Figure 1.

Study flow of case inclusion and exclusion. Among 339 limbs (310 dogs) treated with the 3D cast, 70 were excluded due to surgical history, 33 due to delayed presentation (>7 days), and 45 for other reasons (body weight >10 kg, comminuted fracture, isolated radial/ulnar fracture, lost to follow-up, handover to another clinic, or refracture). Finally, 191 limbs (179 dogs) were included for analysis. Cases with multiple exclusion criteria were categorized by a predefined hierarchy, prioritizing surgical history; cases involving surgical complications inherently included delayed presentation and were therefore classified under “surgical complications.”.

Figure 1. Study flow diagram of case inclusion and exclusion. Among 339 limbs (318 dogs) initially treated with the 3D cast, 70 were excluded due to prior surgery, 33 due to delayed presentation (>7 days), and 45 for other reasons (body weight >10 kg, comminuted fracture, isolated radial or ulnar fracture, loss to follow-up, handover to another clinic, or refracture). In total, 191 limbs (179 dogs) were included in the final analysis.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population (n = 191 limbs, 179 dogs).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n = 191 limbs, 179 dogs). Values are expressed as median [interquartile range] or number of limbs (percentage). Dogs were stratified into four age groups: <6 months, 6–12 months, 1–2 years, and ≥2 years.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n = 191 limbs, 179 dogs). Values are expressed as median [interquartile range] or number of limbs (percentage). Dogs were stratified into four age groups: <6 months, 6–12 months, 1–2 years, and ≥2 years.

| Characteristic |

Median [IQR] or n (%) |

| Age (years) |

0.75 [0.42–1.00] |

| Body weight (kg) |

2.2 [1.6–3.0] |

| Age group (limbs) |

|

| <6 months |

49 (25.7) |

| 6–12 months |

75 (39.3) |

| 1–2 years |

38 (19.9) |

| ≥2 years |

29 (15.2) |

| Breed distribution (dogs) |

|

| Toy Poodle |

97 (50.8) |

| Pomeranian |

44 (23.0) |

| Italian Greyhound |

14 (7.3) |

| Mix |

16 (8.4) |

| Other small breeds |

20 (10.5) |

| Clinical course (days) |

|

| Injury to first visit |

1 [1–3] |

| Complete immobilization |

7 [6–9] |

| 3D cast application |

42 [31–56] |

| Fracture healing |

50 [39–66.5] |

Dogs were stratified into four age groups: <6 months, 6–12 months, 1–2 years, and ≥2 years [6]. Both age and body weight were included as explanatory variables to evaluate their potential effects on healing time.

2.2. Treatment Protocol

Fracture management followed the protocol established at our hospital for patient-specific, custom-made 3D cast treatment.

Initial manual reduction and traction were performed to correct alignment, followed by temporary splint immobilization.

A 3D cast was fabricated and applied 7–10 days after injury, and weight-bearing was permitted immediately thereafter [10].

Cast fitting and limb condition were checked weekly, with radiographic evaluations performed every 2 weeks.

Fracture union was defined as the presence of smooth bridging callus across the fracture line, confirmed on four radiographic views: anteroposterior, lateral, and two oblique projections [7–9].

2.3. Radiographic Image Processing

All radiographs were processed uniformly to ensure consistency across age groups. Radiographs of left limbs were mirrored for orientation, and brightness and contrast were adjusted in a standardized manner. Each image was cropped to highlight the fracture site while retaining key anatomical landmarks. A digital scale bar was generated in Fiji software using DICOM metadata, and final images were exported as 300 dpi TIFF files in accordance with journal guidelines.

Radiographic Evaluation of Healing Patterns

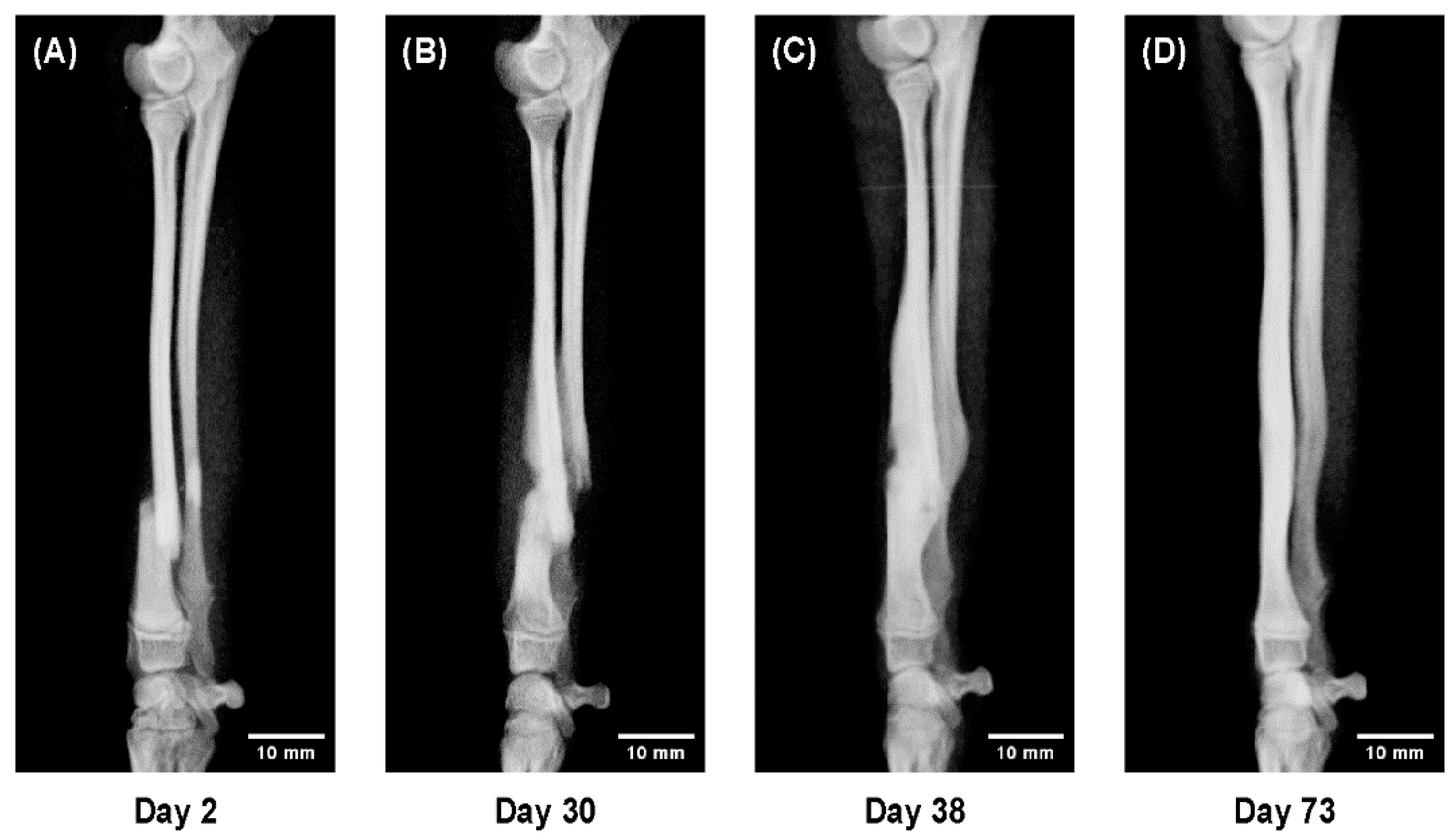

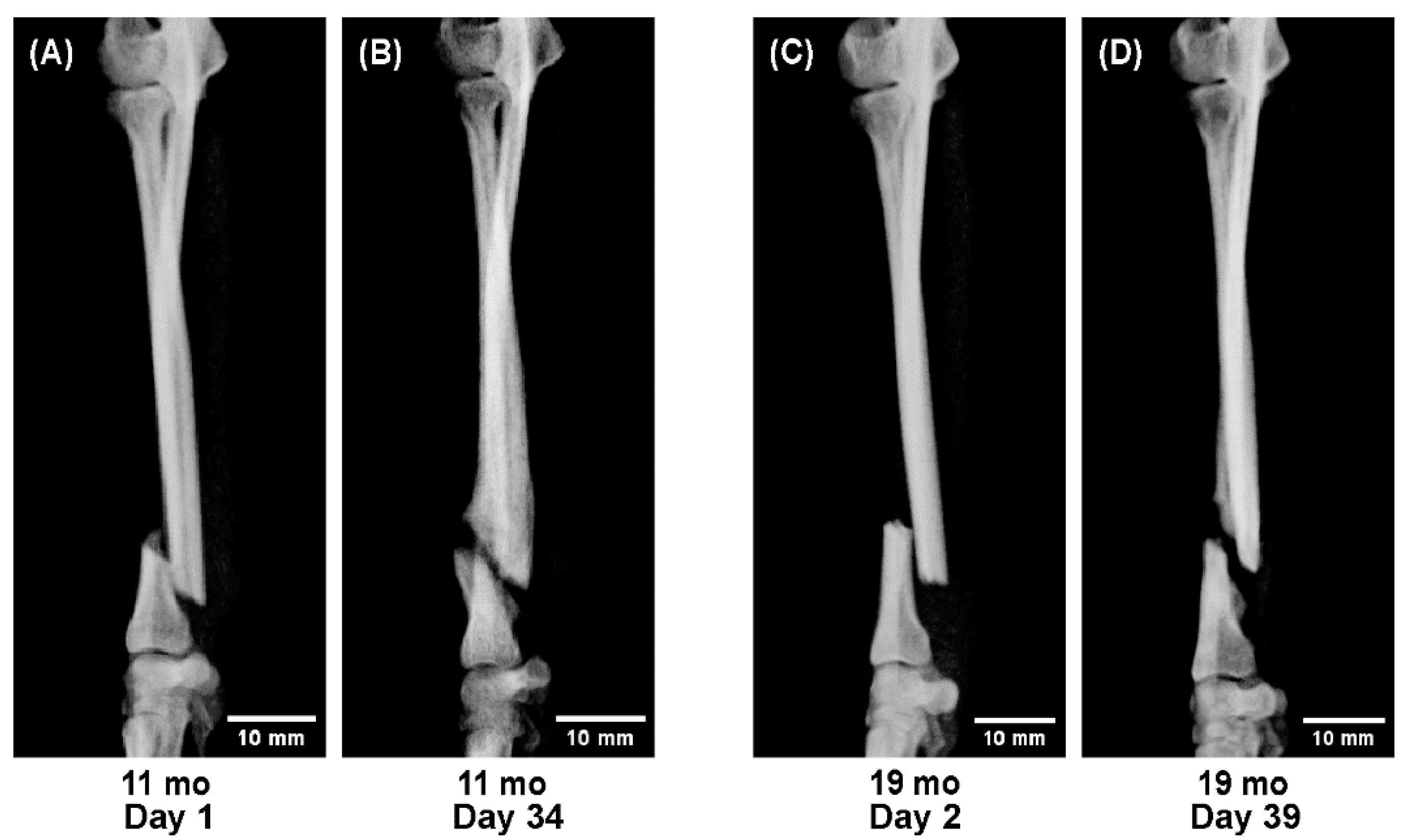

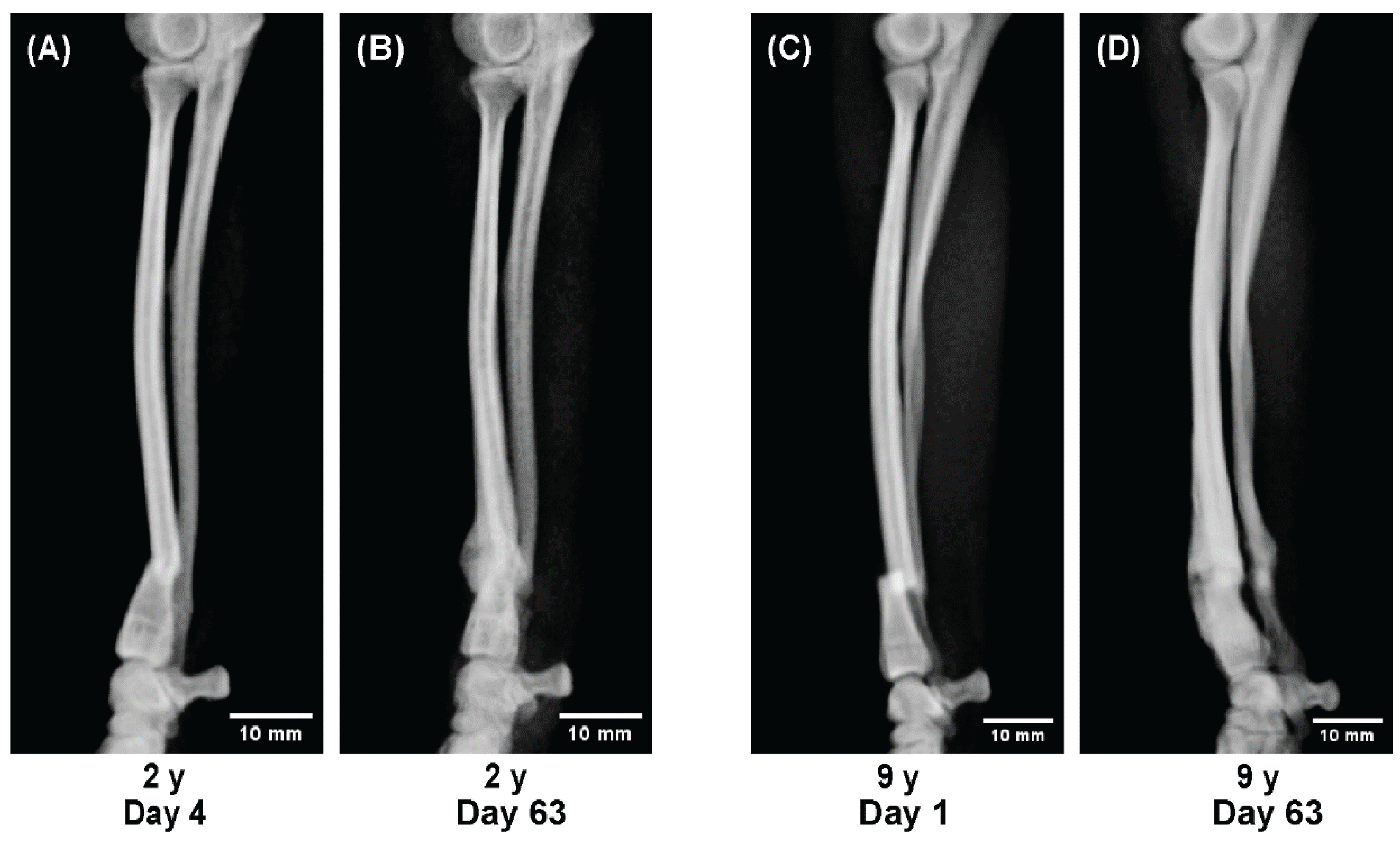

To evaluate age-related differences in bone healing dynamics, sequential radiographs were compared across representative cases from each age group.

All radiographs were obtained in four projections—anteroposterior, lateral, and two oblique views—at approximately two-week intervals throughout the treatment period.

Representative cases were selected to illustrate characteristic healing patterns observed at different life stages:

A 5-month-old dog showing rapid callus proliferation (juvenile stage),

Dogs aged 11 and 19 months showing reduced callus formation (adolescent stage), and

Dogs aged 2 and 9 years showing stable but slower consolidation (adult to senior stage).

These radiographic sequences (Figures 4–6) were analyzed qualitatively to visualize temporal differences in callus formation, cortical remodeling, and alignment correction under 3D cast management.

2.4. Outcome Measures

Fracture union was defined as the presence of smooth bridging callus across the fracture line, confirmed on four radiographic views: anteroposterior, lateral, and two oblique projections [7–10,13]. Indirect fracture healing was characterized by abundant callus formation, which subsequently remodeled toward the original bone contour.

The primary outcome was the time to radiographic union, defined as the number of days required for cortical continuity to be visible in all four projections. Healing time was summarized as the median with interquartile range (IQR). To compare healing dynamics, Kaplan–Meier survival curves and box-and-whisker plots were generated for the four predefined age groups (<6 months, 6–12 months, 1–2 years, and ≥2 years) [11].

The secondary outcomes included:

Healing time stratified by body weight categories,

Multivariable analysis of age and body weight as independent predictors of healing time, and

Radiographic features of bone healing, such as callus formation and spontaneous alignment correction.

To illustrate age-related differences in regenerative capacity, representative cases were presented:

A sequential radiographic series of a 5-month-old dog,

Comparative observations between 11 and 19 months, and

Between 2 and 9 years.

In addition, the incidence and timing of refracture were recorded.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Healing time was summarized as the median with interquartile range (IQR).

Values are presented as median with interquartile range (IQR) unless otherwise specified. Regression coefficients (β) are shown with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Differences in healing time among age groups were evaluated using the Kaplan–Meier method with log-rank testing [11].

Kaplan–Meier curves and box-and-whisker plots were generated in R to illustrate the distribution and variability of healing time across groups [12].

Linear regression analysis was performed to assess the effects of age and body weight on healing time.

All statistical analyses and figure generation were conducted using R software (version 4.5.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with significance set at p < 0.05.

2.6. Ethical Approval and Owner Consent

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of Ishijima Animal Hospital (Kashiwa, Chiba, Japan).

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the hospital’s internal ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from all dog owners prior to treatment and inclusion in this retrospective study.

3. Results

3.1. Age-Stratified Analysis of Healing Time

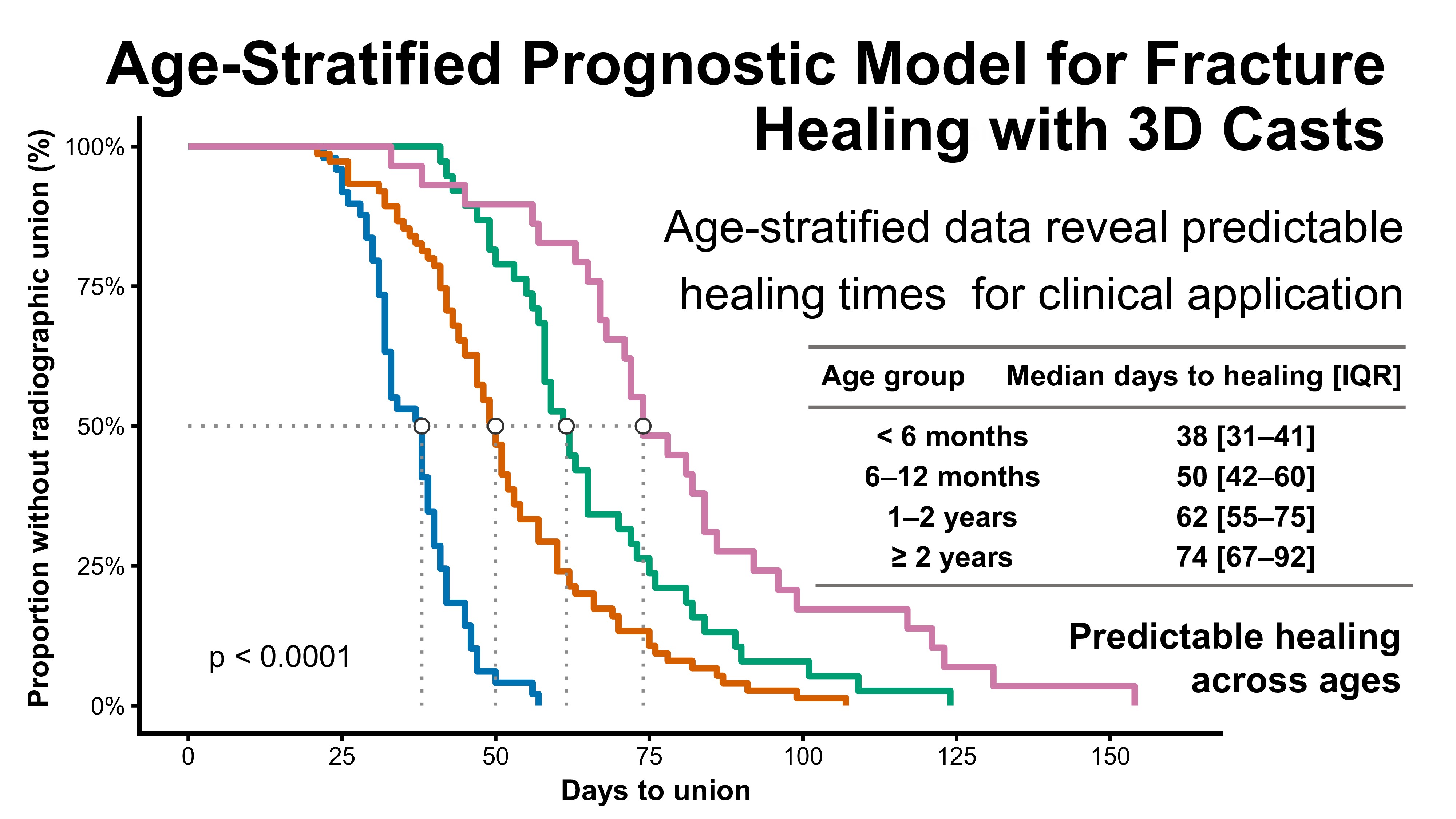

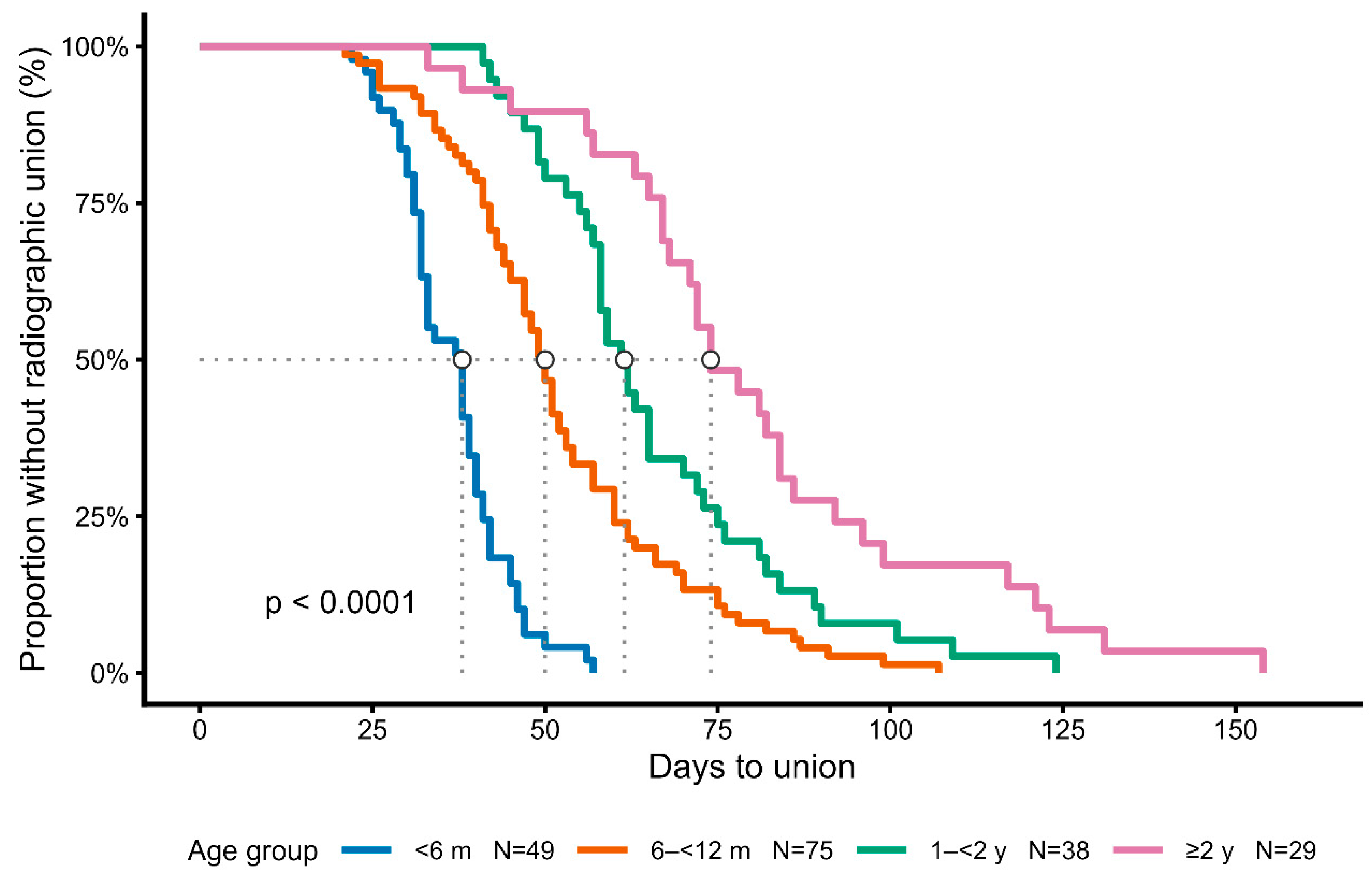

Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated significant differences in healing time among the four age groups (log-rank test, p < 0.0001) [11].

Younger dogs achieved union earlier, with median healing times of 38 days [IQR 31–41] in dogs <6 months (n = 49), 50 days [42–60] in those 6–12 months (n = 75), 62 days [55–75] in those 1–2 years (n = 38), and 74 days [67–92] in dogs ≥2 years (n = 29) (

Table 2).

These differences, showing progressively longer healing times in older dogs, are illustrated by the Kaplan–Meier survival curves (

Figure 2).

Median values and interquartile ranges are provided in

Table 2 for clarity.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of healing time stratified by age group. Healing time differed significantly among the four age groups (log-rank test,

p < 0.0001). Median healing times with interquartile ranges are summarized in

Table 2.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of healing time stratified by age group. Healing time differed significantly among the four age groups (log-rank test,

p < 0.0001). Median healing times with interquartile ranges are summarized in

Table 2.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier survival curves of fracture healing stratified by age group. Healing time differed significantly among the four age groups (log-rank test, p < 0.0001). Median healing times with interquartile ranges are summarized in

Table 2.

Table 2. Median healing time according to age group.

Table 2.

Median healing time according to age group. Values are expressed as median [interquartile range]. Healing time progressively increased with age, with statistically significant differences among the four groups (log-rank test, p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Median healing time according to age group. Values are expressed as median [interquartile range]. Healing time progressively increased with age, with statistically significant differences among the four groups (log-rank test, p < 0.0001).

| Age group |

n |

Median days to healing [IQR] |

| <6 months |

49 |

38 [31–41] |

| 6–12 months |

75 |

50 [42–60] |

| 1–2 years |

38 |

62 [55–75] |

| ≥2 years |

29 |

74 [67–92] |

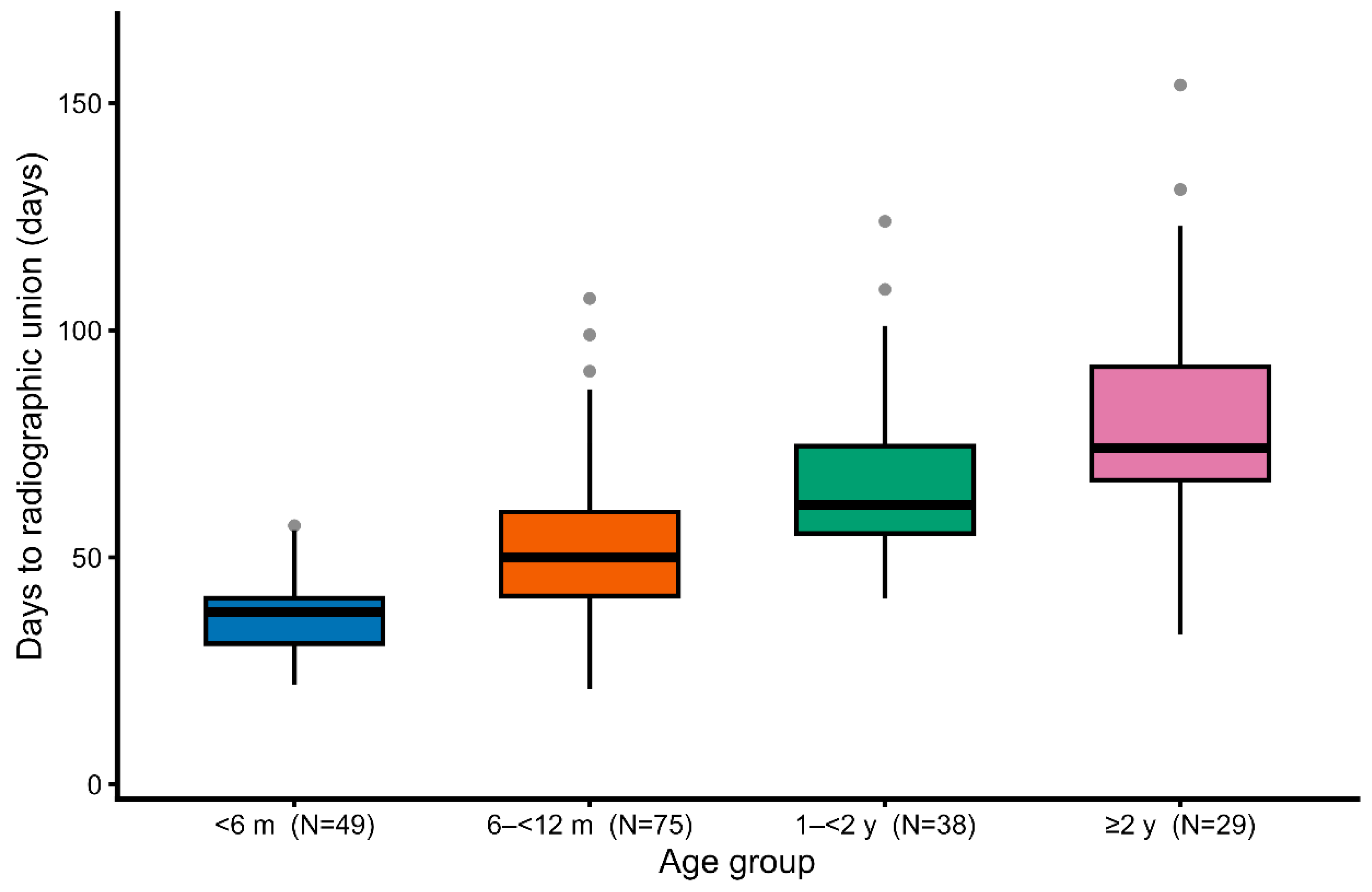

3.2. Box Plots of Healing Time

Boxplot analysis further illustrated this trend, showing not only the progressive prolongation of healing time with age but also a wider interquartile range in older dogs (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Boxplots of healing time stratified by age group. With increasing age, both the median time to union and the variability in healing duration became greater.

Figure 3.

Boxplots of healing time stratified by age group. With increasing age, both the median time to union and the variability in healing duration became greater.

Figure 3. Box-and-whisker plots of healing time stratified by age group. With increasing age, both the median healing time and the variability in healing duration increased.

3.3. Regression Analysis

Regression analysis (n = 191 limbs) demonstrated that age was independently associated with longer healing time (β = 4.6 days per year; 95% CI, 3.1–6.2; p < 0.001), whereas body weight showed no significant effect (β = 1.0 days per kg; 95% CI, –2.3–4.3; p = 0.54) (

Table 3).

Table 3. Linear regression analysis of time to radiographic union (days).

Table 3.

Linear regression analysis of time to radiographic union (days). Analysis was performed on 191 limbs, with the outcome defined as time to radiographic union (days). Age was significantly associated with longer healing time, whereas body weight showed no significant effect.

Table 3.

Linear regression analysis of time to radiographic union (days). Analysis was performed on 191 limbs, with the outcome defined as time to radiographic union (days). Age was significantly associated with longer healing time, whereas body weight showed no significant effect.

| Variable |

β (days) |

95% CI |

p-value |

| Age (per 1 year) |

4.6 |

3.1 – 6.2 |

<0.001* |

| Weight (per 1 kg) |

1.0 |

–2.3 – 4.3 |

0.54 |

Analysis was performed on 191 limbs. Outcome was defined as time to radiographic union (days).95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

3.4. Body Weight Analysis

In addition, scatter plots were generated to visualize the relationships between explanatory variables and healing time.

Furthermore, age and body weight demonstrated no significant collinearity, supporting their use as independent variables in the regression model (

Supplementary Figure S2).

This finding indicates that regenerative capacity is primarily age-dependent, rather than influenced by body mass within the ≤10 kg toy-breed population.

3.5. Radiographic Comparison by Age

Sequential radiographs of representative cases demonstrated clear age-dependent differences in the bone healing process under 3D cast management (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

In a 5-month-old dog, rapid callus proliferation bridged the fracture line within 2 weeks, temporarily doubling bone diameter before remodeling toward normal morphology (

Figure 4).

At 11 months of age, abundant callus formation was still evident; however, by 19 months, callus volume was clearly reduced, with slower consolidation and delayed cortical remodeling (

Figure 5).

Beyond 2 years of age, regenerative capacity appeared relatively stable; both a 2-year-old Toy Poodle and a 9-year-old Pomeranian achieved union with comparable healing dynamics, although callus formation was less pronounced than in juveniles (

Figure 6).

These sequential radiographs provide direct visual evidence of the age-related reduction in regenerative potential that corresponds to the quantitative results of the Kaplan–Meier and regression analyses.

4. Discussion

This large-scale clinical study demonstrated clear, age-dependent differences in fracture healing among toy-breed dogs treated with patient-specific 3D cast therapy. Reliable union was achieved in all 191 limbs, confirming the reproducibility and clinical practicality of this conservative method. Healing progressed extremely rapidly in dogs under 6 months of age, remained efficient in those up to 12 months, and became gradually slower between 1 and 2 years, after which it stabilized.

Sequential radiographs provided visual confirmation of these quantitative findings. In dogs under one year, callus formation was remarkably active and remodeling occurred within weeks. Between 1 and 2 years of age, healing patterns shifted toward a more mature, stable process with reduced callus formation—representing a physiological transition rather than a pathological decline. Notably, refractures (2.6%) occurred mainly during this transitional stage, coinciding with the radiographic reduction in callus production. This overlap suggests that the remodeling shift occurring in late adolescence may temporarily weaken structural resilience, a finding consistent with developmental changes described in other species [7–9,13–15].

The statistical results and radiographic observations were highly consistent, reinforcing the reliability of this model. By combining numerical analysis with direct visual evidence, the study provides a level of clarity and clinical relevance that purely statistical or descriptive approaches alone could not achieve. The ability to interpret healing behavior both quantitatively and visually gives veterinarians a deeper understanding of patient recovery and a rational basis for predicting healing duration.

Regression analysis identified age, but not body weight, as an independent determinant of healing time.This finding indicates that slender bones themselves are not biologically prone to delayed union, but rather that the observed fracture tendency in toy breeds arises from their mechanical and structural characteristics.

Fracture occurrence was predominantly observed in Toy Poodles, Pomeranians, and Italian Greyhounds—breeds known to possess narrow medullary canals and limited periosteal coverage, resulting in reduced resistance to bending and torsional stress. Micro-CT analysis further revealed that these breeds have sparse and thin trabeculae with a high cortical-to-trabecular ratio, indicating lower capacity for internal energy absorption and thus greater susceptibility to fracture under normal loading [10].

Historically, the difficulty in treating toy-breed radius–ulna fractures arose from technical challenges of fixation, not from poor healing capacity. Under stable, physiological loading with the 3D cast, slender bones demonstrated equivalent regenerative potential, overturning the long-held assumption that “small means fragile.” This finding allows prognosis to be guided primarily by patient age, providing a simple and objective indicator that can be applied directly in clinical decision-making. Although this was a single-center, retrospective study limited to toy breeds (≤10 kg), the combination of a standardized treatment protocol, consistent radiographic follow-up, and large sample size enabled a robust age-based analysis. This approach revealed for the first time, in a real-world clinical setting, how bone healing capacity evolves from the high regenerative state of juveniles to the steady maintenance phase of adults.

Overall, the integration of statistical analysis and sequential imaging established a practical, reproducible framework for predicting fracture healing time in toy-breed dogs. This model not only improves clinical planning and owner communication but also contributes valuable insight into the biological basis of age-dependent bone regeneration.

Future prospective and cellular-level studies are warranted to elucidate the biological mechanisms underlying the rapid bone healing observed in juvenile dogs, particularly the regenerative potential of bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells during early growth. This clinical evidence may serve as a translational link between radiographic healing dynamics and the cellular biology of bone regeneration, providing a foundation for future collaborative studies on mesenchymal stem cell function in dogs.

5. Conclusions

This study established an age-stratified, evidence-based model for accurately predicting fracture healing time in toy-breed dogs treated with patient-specific 3D cast therapy.

By integrating large-scale statistical analysis with continuous radiographic visualization, it provided both quantitative and visual confirmation of age-dependent healing dynamics.

The results clarified the physiological transition from the highly regenerative juvenile phase to the stable adult phase, offering practical prognostic indicators directly applicable to clinical decision-making.

3D cast therapy thus represents a reliable and minimally invasive treatment that enhances patient welfare, reveals fundamental mechanisms of physiological bone regeneration, and may help define future standards of conservative fracture management in small animals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Shigeo Ishijima performed all aspects of the study, including conceptualization, methodology, data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, because it was based on retrospective analysis of clinical case records.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all owners for the treatment of their animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the staff of Ishijima Animal Hospital for their assistance in data collection and patient care.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Harasen G. Radius and ulna fractures in dogs and cats: a review. Can Vet J. 2003;44:475–6.

- Beever L, Gemmill T, et al. Review of radial and ulnar fractures in toy breeds: outcomes and complications. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2019;32:201–9.

- Gemmill T, McCartney W. Management of radial and ulnar fractures in small breed dogs. Companion Anim. 2020;25:142–50.

- Aikawa T, Shimizu J, Takahashi T, et al. Treatment of distal radial and ulnar fractures in miniature- and toy-breed dogs using a free-form multiplanar type II external skeletal fixator. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2019;254:1303–10.

- Pozzi A, Risselada M, Winter MD. Assessment of fracture healing after minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis or open reduction and internal fixation of coexisting radius and ulna fractures in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;241:744–53. [CrossRef]

- Dvořák M, Horák M, Bečvář J, et al. Complications of long bone fracture healing in dogs. Acta Vet Brno. 2000;69:107–14. [CrossRef]

- Einhorn TA. The cell and molecular biology of fracture healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;355 Suppl:S7–21. [CrossRef]

- Marsell R, Einhorn TA. The biology of fracture healing. Injury. 2011;42:551–5. [CrossRef]

- Wehrli BM, Stoupis C, Boos N, et al. Age-dependent changes in fracture healing. Bone. 2010;46:1173–80. [CrossRef]

- Planner F, Feichtner J, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Comparative microcomputed tomographic structural analysis of the trabecular and cortical bone architecture of radius and ulna in toy dog breeds. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2021;34(3):182–91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33761436/.

- O’Sullivan ME, Bronk JT, Chao EY, Kelly PJ. Experimental study of the effect of weight bearing on fracture healing in the canine tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;302:273–83. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81.

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time-to-Event Data. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2008.

- Claes L, Recknagel S, Ignatius A. Fracture healing under healthy and inflammatory conditions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:133–43. [CrossRef]

- Morgan EF, et al. Mechanobiology of bone healing. J Orthop Res. 2018;36:313–23. [CrossRef]

- Gerstenfeld LC, et al. Age-related changes in fracture healing. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17(Suppl 10):S21–9. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, et al. Mechanobiology of indirect bone fracture healing under conditions of relative stability. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:942885. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).