Submitted:

30 May 2023

Posted:

01 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study setting

2.2. Patient enrollment

2.3. Surgical technique

2.4. Data collection

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

6. Limitation

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nordqvist, A.; Petersson, C.J. Incidence and causes of shoulder girdle injuries in an urban population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1995, 4, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnell, O.; Kanis, J.A. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 2006, 17, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Szabo, R.M.; Marder, R.A. Epidemiology of humerus fractures in the United States: nationwide emergency department sample, 2008. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012, 64, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horak, J.; Nilsson, B.E. Epidemiology of fracture of the upper end of the humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1975, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornetta, P., III. Rockwood and Green’s fractures in adults, 9th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, 2020; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.E.; et al. Trends and variation in incidence, surgical treatment, and repeat surgery of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011, 93, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, E.; et al. Nondisplaced proximal humeral fractures: high incidence among outpatient-treated osteoporotic fractures and severe impact on upper extremity function and patient subjective health perception. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011, 20, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siffri, P.C.; et al. Biomechanical analysis of blade plate versus locking plate fixation for a proximal humerus fracture: comparison using cadaveric and synthetic humeri. J Orthop Trauma 2006, 20, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, P.; et al. Mid-term results of internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures with the Philos plate. Injury 2009, 40, 1292–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkenheim, J.M.; Pajarinen, J.; Savolainen, V. Internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures with a locking compression plate: a retrospective evaluation of 72 patients followed for a minimum of 1 year. Acta Orthop Scand 2004, 75, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavuri, V.; et al. Complications Associated with Locking Plate of Proximal Humerus Fractures. Indian J Orthop 2018, 52, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, N.; et al. Complications encountered in proximal humerus fractures treated with locking plate fixation. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2010, 44, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Südkamp, N.; et al. Open reduction and internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures with use of the locking proximal humerus plate. Results of a prospective, multicenter, observational study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009, 91, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egol, K.A.; et al. Early complications in proximal humerus fractures (OTA Types 11) treated with locked plates. J Orthop Trauma 2008, 22, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamura, S.; et al. Bone resorption of the greater tuberosity after open reduction and internal fixation of complex proximal humeral fractures: fragment characteristics and intraoperative risk factors. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2021, 30, 1626–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spross, C.; et al. Deltoid Tuberosity Index: A Simple Radiographic Tool to Assess Local Bone Quality in Proximal Humerus Fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015, 473, 3038–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boileau, P.; et al. Tuberosity malposition and migration: reasons for poor outcomes after hemiarthroplasty for displaced fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002, 11, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannotti, J.P.; et al. The normal glenohumeral relationships. An anatomical study of one hundred and forty shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992, 74, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordin, M. Basic Biomechanics of the Musculoskeletal System, 5th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- CHARLES S NEER, II. Displaced Proximal Humeral Fractures: Part I. Classification and Evaluation. JBJS 1970, 52, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neer, C.S., 2nd. Four-segment classification of proximal humeral fractures: purpose and reliable use. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002, 11, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, T.; et al. Humeral insertion of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. New anatomical findings regarding the footprint of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008, 90, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavert, P.; et al. Pitfalls and complications with locking plate for proximal humerus fracture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010, 19, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zura, R.; et al. Epidemiology of Fracture Nonunion in 18 Human Bones. JAMA Surg 2016, 151, e162775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinonapoli, G.; et al. Obesity and Bone: A Complex Relationship. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 13662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; et al. Obesity and Bone Health: A Complex Link. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savvidis, C.; Tournis, S.; Dede, A.D. Obesity and bone metabolism. Hormones 2018, 17, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, E.A.; Lenzi, A.; Migliaccio, S. The obesity of bone. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2015, 6, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.J. Effects of obesity on bone metabolism. J Orthop Surg Res 2011, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlich, P.J.; Lanyon, L.E. Mechanical strain and bone cell function: a review. Osteoporos Int 2002, 13, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, B.L. The mechanisms of estrogen regulation of bone resorption. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2000, 106, 1203–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C.J.; Bouxsein, M.L. Mechanisms of disease: is osteoporosis the obesity of bone? Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2006, 2, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; et al. IL-1 mediates TNF-induced osteoclastogenesis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2005, 115, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosla, S. Minireview: the OPG/RANKL/RANK system. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 5050–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, Y.; et al. Interleukin-6-type cytokines stimulate mesenchymal progenitor differentiation toward the osteoblastic lineage. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 1998, 110, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Macchi, M.; et al. Obesity Increases the Risk of Tendinopathy, Tendon Tear and Rupture, and Postoperative Complications: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2020, 478, 1839–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate, M.; et al. Metabolic syndrome associated to non-inflammatory Achilles enthesopathy. Clin Rheumatol 2014, 33, 1517–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taş, S.; et al. Patellar tendon mechanical properties change with gender, body mass index and quadriceps femoris muscle strength. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2017, 51, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, M.; et al. Body Mass Index and Segmental Mass Correlation With Elastographic Strain Ratios of the Quadriceps Tendon. J Ultrasound Med 2019, 38, 2005–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, M. How obesity modifies tendons (implications for athletic activities). Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2014, 4, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancalana, A.; Veloso, L.A.; Gomes, L. Obesity affects collagen fibril diameter and mechanical properties of tendons in Zucker rats. Connect Tissue Res 2010, 51, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, J.E.; et al. Obesity/Type II diabetes alters macrophage polarization resulting in a fibrotic tendon healing response. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0181127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.A.; et al. Tendon repair is compromised in a high fat diet-induced mouse model of obesity and type 2 diabetes. PLoS One 2014, 9, e91234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, M.; et al. Achilles tendinopathy in amateur runners: role of adiposity (Tendinopathies and obesity). Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2012, 2, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wasim, M.; et al. Role of Leptin Deficiency, Inefficiency, and Leptin Receptors in Obesity. Biochem Genet 2016, 54, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarese, G.; et al. Regulatory T cells in obesity: the leptin connection. Trends Mol Med 2010, 16, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haanen, C.; Vermes, I. Apoptosis and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 1995, 4, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, M.; Sakaue, H. Adipocyte Death and Chronic Inflammation in Obesity. J Med Invest 2017, 64, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fankhauser, F.; et al. Cadaveric-biomechanical evaluation of bone-implant construct of proximal humerus fractures (Neer type 3). J Trauma 2003, 55, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kralinger, F.; et al. The Influence of Local Bone Density on the Outcome of One Hundred and Fifty Proximal Humeral Fractures Treated with a Locking Plate. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014, 96, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krappinger, D.; et al. Predicting failure after surgical fixation of proximal humerus fractures. Injury 2011, 42, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskesen, A.; et al. Effect of Osteoporosis on Proximal Humerus Fractures. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2020, 11, 2151459320985399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bue, M.; et al. Osteoporosis does not affect bone mineral density change in the proximal humerus or the functional outcome after open reduction and internal fixation of unilateral displaced 3- or 4-part fractures at 12-month follow-up. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2023, 32, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wunnik, B.P.; et al. Osteoporosis is not a risk factor for the development of nonunion: A cohort nested case-control study. Injury 2011, 42, 1491–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diederichs, G.; et al. Assessment of bone quality in the proximal humerus by measurement of the contralateral site: a cadaveric analyze. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2006, 126, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krappinger, D.; et al. Preoperative assessment of the cancellous bone mineral density of the proximal humerus using CT data. Skeletal Radiol 2012, 41, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, J.; et al. Proximal humerus cortical bone thickness correlates with bone mineral density and can clinically rule out osteoporosis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013, 22, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tingart, M.J.; et al. The cortical thickness of the proximal humeral diaphysis predicts bone mineral density of the proximal humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003, 85, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dheenadhayalan, J.; et al. Correlation of radiological parameters to functional outcome in complex proximal humerus fracture fixation: A study of 127 cases. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2019, 27, 2309499019848166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrend, M.D.; et al. Radiographic parameter(s) influencing functional outcomes following angular stable plate fixation of proximal humeral fractures. Int Orthop 2021, 45, 1845–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

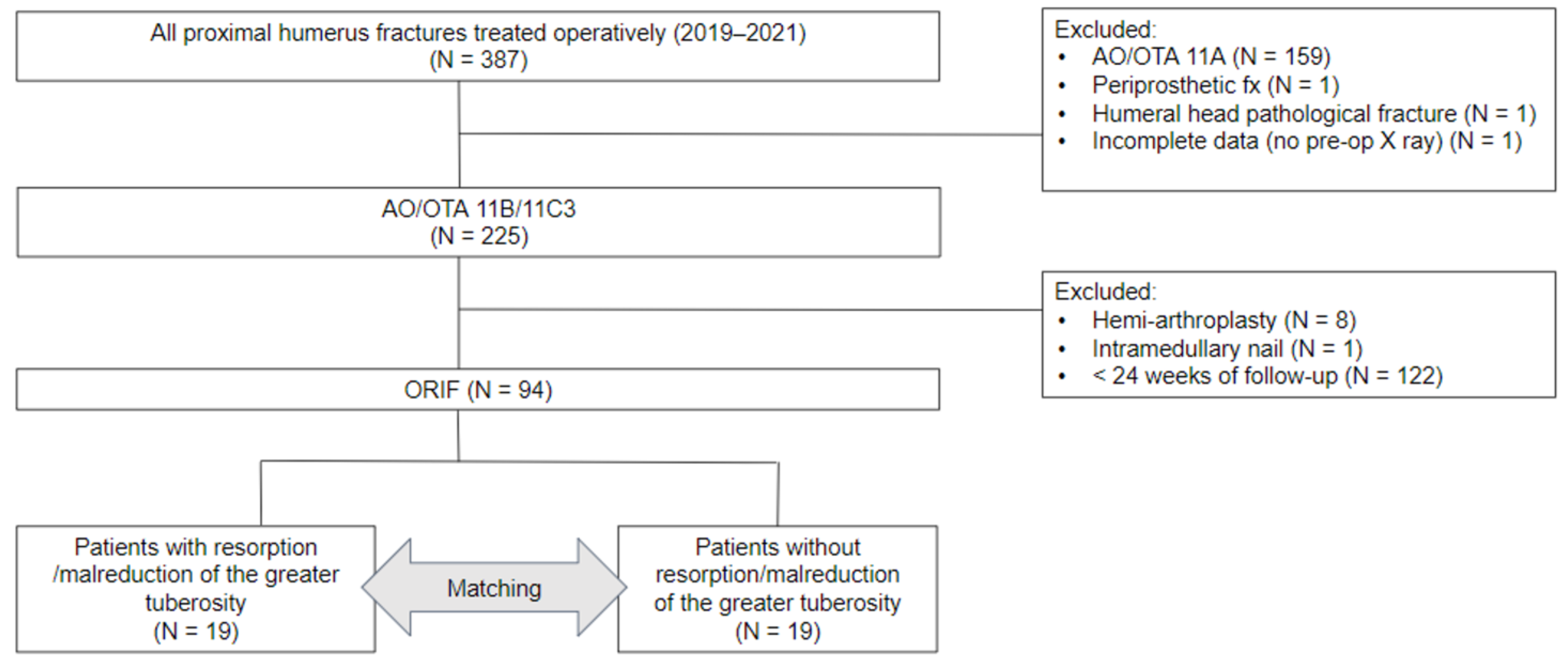

| Patients (n = 94) | Variables |

|---|---|

| Age (year) | 63.32 ± 14.6 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 31; 33% |

| Female | 63; 67% |

| Height (cm) | 159.16 ± 9.54 |

| Weight (Kg) | 63.94 ± 14.41 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 25.09 ± 4.53 |

| Alcohol consumption | 9/94 (9.57%) |

| Smoking | 8/94 (8.51%) |

| Deltoid tuberosity index | 1.41 ± 0.16 |

| Neer classification | |

| 2-part | 26/94 (27%) |

| 3-part | 60/94 (64%) |

| 4-part | 8/94 (9%) |

| AO/OTA classification | |

| 11B1.1 | 82/94 (87%) |

| 11C3 | 12/94 (13%) |

| Time to surgery (day) | 2.93 ± 5.40 |

| Time of follow up (weeks) | 45.55 ± 25.62 |

| Greater tuberosity resorption | 13/94 (13.82%) |

| Malreduction of greater tuberosity | 11/94 (11.7%) |

| Time from surgery to GT resorption or malreduction (week) | 8.77 ± 7.86 |

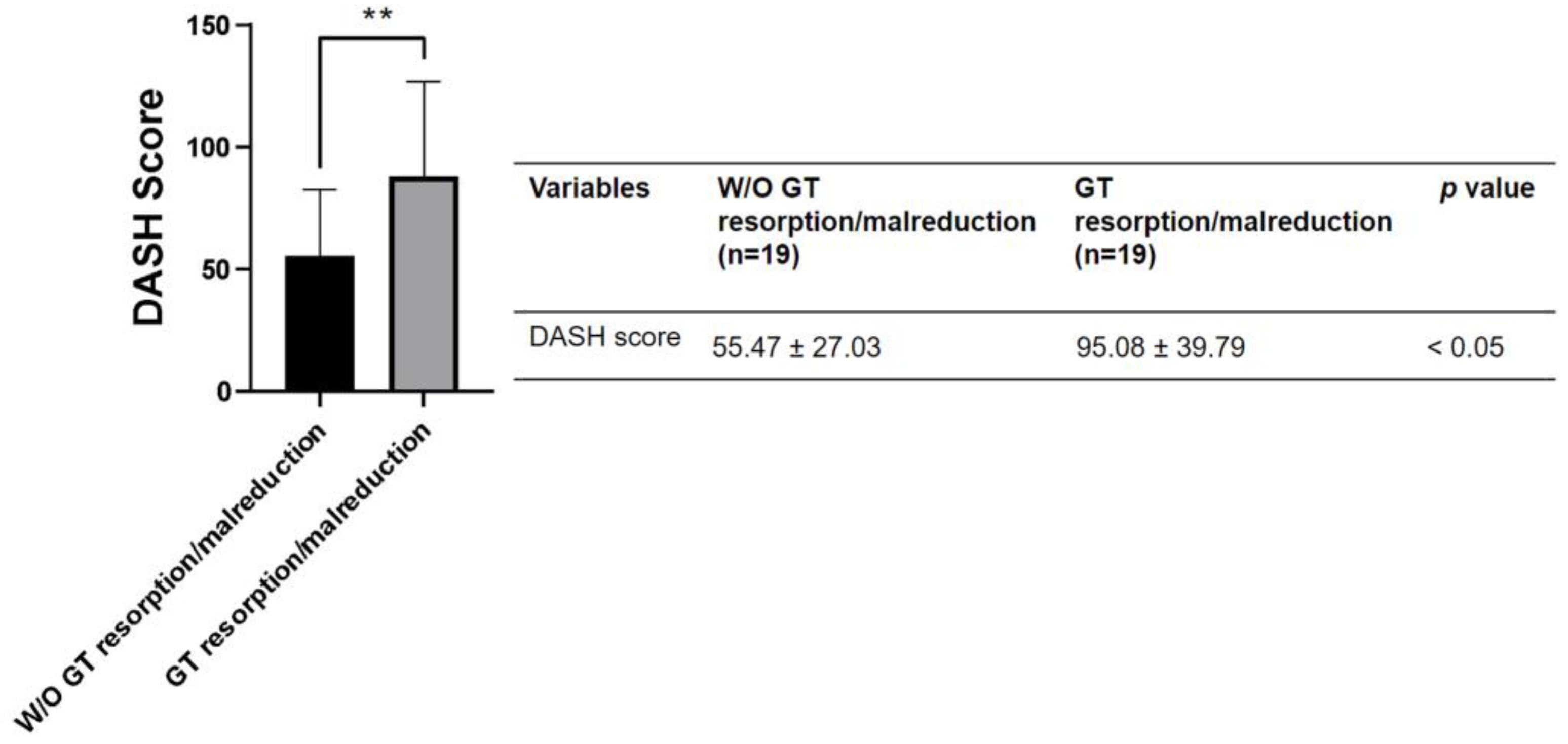

| Variables | W/O GT resorption/malreduction (n = 19) | GT resorption/malreduction (n = 19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 70.58 ± 10.62 | 70.68 ± 11.04 | n.s |

| Male | 4/19 (21%) | 4/19 (21%) | n.s |

| Female | 15/19 (79%) | 15/19 (79%) | n.s |

| Height (cm) | 157.42 ± 8.92 | 155.95 ± 7.71 | n.s |

| Weight (Kg) | 59.05 ± 9.16 | 67.16 ± 17.92 | n.s |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 23.85 ± 3.37 | 27.35 ± 6.03 | 0.0337 |

| Smoking | 0/19 (0%) | 1/19 (5%) | n.s |

| Alcohol consumption | 1/19 (5%) | 1/19 (5%) | n.s |

| Deltoid tuberosity index | 1.36 ± 0.15 | 1.41 ± 0.13 | n.s |

| Neer classification | |||

| 2-part | 6/19 (32%) | 6/19 (32%) | n.s |

| 3-part | 13/19 (68%) | 11/19 (58%) | n.s |

| 4-part | 0/19 (0%) | 1/19 (10%) | n.s |

| AO/OTA classification | |||

| 11B1.1 | 18/19 (95%) | 17/19 (89%) | n.s |

| 11C3 | 1/19 (5%) | 2/19 (11%) | n.s |

| Time to surgery (day) | 4.11 ± 7.02 | 4.32 ± 8.45 | n.s |

| Time of follow up (week) | 40.48 ± 26.22 | 42.23 ± 29.01 | n.s |

| Artificial bone graft use | 11/19 (58%) | 12/19 (63%) | n.s |

| Inadequate medial support | 0/19 (0%) | 3/19 (16%) | n.s |

| Variables | W/O GT resorption/malreduction (n = 19) | GT resorption/malreduction (n = 19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral humeral offset (cm) | 4.85 ± 0.44 | 4.56 ± 0.44 | n.s |

| Head diameter (cm) | 4.71 ± 0.45 | 4.5 ± 0.34 | n.s |

| Head height (cm) | 1.72 ± 0.2 | 1.68 ± 0.28 | n.s |

| Perpendicular height (cm) | 4.95 ± 0.6 | 4.69 ± 0.61 | n.s |

| Neck shaft angle (degree) | 138.27 ± 13.73 | 137.82 ± 9.6 | n.s |

| Superior displacement of GT above articular surface | 0/19 (0%) | 13/19 (68.42%) | 0.0463 |

| Medial gas > 4 mm | 0/19 (0%) | 5/19 (26.32%) | 0.0463 |

| Use of calcar specific screw | 19/19 (100%) | 16/19 (84.21%) | 0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).