1. Introduction

Proximal humerus fractures (PHFs) are among the most common fractures encountered in clinical practice, with an incidence that is expected to rise significantly due to the increasing aging population. Representing approximately 4-10% of all fractures [

1,

2], PHFs are the second most prevalent upper extremity fractures and the third most frequent fractures overall in the elderly. Epidemiological data indicate an incidence of 31 to 250 cases per 100,000 adults, with a steady increase correlating with aging demographics. According to Roux et al. [

3], the critical age for this type of fracture is 70 years, and the dominant arm is affected in 48% of cases.

Proximal humerus fractures follow a bimodal distribution, resulting from low-energy trauma (e.g., falls) in elderly individuals with osteoporosis and high-energy trauma (e.g., road accidents or sports injuries) in younger patients [

3,

4]. Studies report that in men, 55% of fractures result from simple falls, whereas 45% are due to high-energy trauma, while in women, 82% of fractures are attributed to low-energy falls [

5]. The mechanisms leading to PHFs involve direct trauma or an axial load transmitted to the humerus, often through the extended elbow, hand, or forearm [

6].

Approximately 80-85% of PHFs are non-displaced or minimally displaced and are managed conservatively, while the remaining 15-20% require surgical intervention, particularly when associated with glenohumeral dislocation. In displaced fractures, surgical treatment is recommended based on several key factors, including fracture pattern (number of fragments, displacement degree, risk of osteonecrosis), patient characteristics (age, functional demand, comorbidities, and bone quality), and surgeon expertise in shoulder trauma management [

7,

8,

9,

10].

A variety of surgical options are available for PHFs, including percutaneous K-wires, external fixation, minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO), open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) with locking plates or intramedullary nails, hemiarthroplasty, total shoulder arthroplasty, and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. However, there remains no universally accepted surgical algorithm, as clinical outcomes are influenced by multiple patient- and fracture-specific factors [

9,

11,

12].

Among the most used surgical techniques, locking plates and intramedullary nails have demonstrated good functional outcomes in properly selected patients. Locking plate osteosynthesis, particularly using Non-Contact Bridging (NCB) plates, is often favored for its ability to provide rigid fixation and preserve vascular supply, while intramedullary nail fixation offers a minimally invasive approach with biomechanical advantages [

8,

9,

13,

14].

Despite the widespread use of these techniques, comparative clinical evidence remains limited, and no definitive consensus exists regarding the optimal fixation method for displaced PHFs.

The objective of this study is to compare the clinical and functional outcomes of locking plate osteosynthesis (NCB plates) and intramedullary nail fixation in patients with displaced proximal humerus fractures. To achieve this, we analyzed DASH and Constant-Murley scores as measures of functional recovery, along with range of motion (ROM) at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. Additionally, we examined age distribution between the two groups and evaluated whether it influenced clinical outcomes. By focusing on these key aspects, this study aims to clarify the efficacy of both fixation techniques and provide a valuable contribution to the ongoing debate regarding the optimal surgical approach for displaced PHFs.

2. Materials and Methods

A total of 245 patients were initially screened. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 58 patients were excluded due to: pathological fractures (n = 12), open fractures (n = 9), previous surgery on the affected shoulder (n = 7), severe cognitive impairment (n = 10), and loss to follow-up before 12 months (n = 20). The final cohort consisted of 187 patients, divided into two treatment groups:

All data were retrieved from electronic medical records and patient charts. A flow diagram of the patient selection process is described in the results.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria:

Age ≥ 18 years;

Displaced proximal humerus fracture (Neer ≥ 2-part);

Surgical treatment with either an intramedullary nail or locking plate within 14 days of trauma;

Minimum clinical and radiographic follow-up of 12 months.

Exclusion criteria:

Pathological or open fractures;

Head-splitting fractures requiring primary arthroplasty;

Previous surgery on the affected shoulder;

Severe cognitive impairment;

Loss to follow-up before 12 months.

2.2. Surgical Technique

All surgical procedures were performed by orthopedic trauma surgeons experienced in upper limb fixation, with the patient in the beach chair position under general anesthesia.

Patients in this group were treated using the Citieffe® Proximal Humerus Nail (Citieffe, Bologna, Italy). The nail was inserted through an antegrade, rotator cuff–sparing approach. Proximal and distal locking screws were applied to ensure angular and axial stability according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Patients received a Non-Contact Bridging (NCB®) Proximal Humerus Plate (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA) via a standard deltopectoral approach. Anatomical reduction was achieved and stabilized with locking screws under fluoroscopic guidance.

Postoperative radiographs were taken in all patients to confirm appropriate implant positioning.

The choice of implant was based on a combination of factors, including fracture morphology (Neer classification), bone quality (Deltoid Tuberosity Index), patient characteristics (age, comorbidities), and surgeon preference. Both techniques were used across different fracture types, reflecting the heterogeneity of clinical decision-making.

2.3. Postoperative Rehabilitation Protocol

All patients followed a standardized rehabilitation program:

Weeks 0–3: Sling immobilization and early passive mobilization;

Weeks 3–6: Active-assisted ROM exercises;

After 6 weeks: Progressive strengthening and full active ROM;

After 12 weeks: Return to daily activities, and gradual return to sports when appropriate.

2.4. Baseline Characteristics and Bone Quality

The following baseline variables were recorded:

Age, sex, ASA score;

Smoking status;

Type of trauma (low- or high-energy);

Side and dominance;

Deltoid Tuberosity Index (DTI) for bone quality assessment;

Time from trauma to surgery (mean: 5.2 ± 1.4 days);

Ongoing osteoporosis treatment at the time of fracture.

Fractures were classified according to the Neer classification system by two independent reviewers; discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

2.5. Clinical and Functional Assessment

Functional outcomes were evaluated at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively using:

DASH Score (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand);

Constant-Murley Score (CMS);

Range of Motion (ROM): forward flexion, abduction, internal rotation, and external rotation were measured with a goniometer.

2.6. Radiographic Evaluation and Complications

Radiographs (AP and lateral views) were taken at each follow-up. Radiographic outcomes included:

Union: defined as bridging callus on at least 3 cortices;

Non-union: absence of healing at 6 months;

Malunion: defined as angulation >20° or displacement >5 mm;

Avascular necrosis (AVN): diagnosed radiographically and confirmed with MRI when suspected.

All complications were recorded and categorized as:

Infections (superficial or deep),

Non-union or malunion,

AVN,

Hardware-related issues (e.g., screw loosening, nail migration),

Reinterventions (e.g., hardware removal, revision surgery).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All data were collected and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 30.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared with independent t-tests;

Categorical variables were analyzed using χ² or Fisher’s exact test;

Pearson’s correlation was used to explore associations between age and functional outcomes;

Multivariable linear regression models were used to adjust for potential confounders (age, fracture type, DTI, smoking status);

All tests were two-sided, with p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant;

95% confidence intervals were calculated for all primary outcomes.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

A total of 187 patients with surgically treated displaced proximal humerus fractures were included in the study: 96 in the intramedullary nail group (IM) and 91 in the locking plate group (LP). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the two cohorts are summarized in

Table 1.

The mean age was significantly higher in the IM group compared to the LP group (68.2 ± 7.0 vs 62.4 ± 9.0 years, p < 0.001). The gender distribution was comparable between the groups (IM: 39 males and 57 females; LP: 35 males and 56 females; p = 0.879).

Fractures were classified according to the Neer system. In the IM group, 36.5% were 2-part fractures, 41.5% 3-part, and 22.0% 4-part. In the LP group, 27.5% were 2-part, 44.0% 3-part, and 28.5% 4-part fractures. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in fracture pattern distribution.

Bone quality assessment based on the deltoid tuberosity index (DTI) revealed that 33.3% of patients in the IM group and 23.1% in the LP group had a DTI < 1.4, indicating low bone density (p = 0.108).

The average time from trauma to surgery was 5.1 ± 1.3 days in the IM group and 5.3 ± 1.4 days in the LP group, with no statistically significant difference (p = 0.392).

Other potential confounding variables—including smoking status, comorbidities such as diabetes, body mass index (BMI), and osteoporosis treatment—did not significantly differ between the groups and are reported in

Table 1.

3.2. Overall Functional Comparison Between Groups

Functional outcomes were assessed at 12 months postoperatively using the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score and the Constant-Murley Score (CMS).

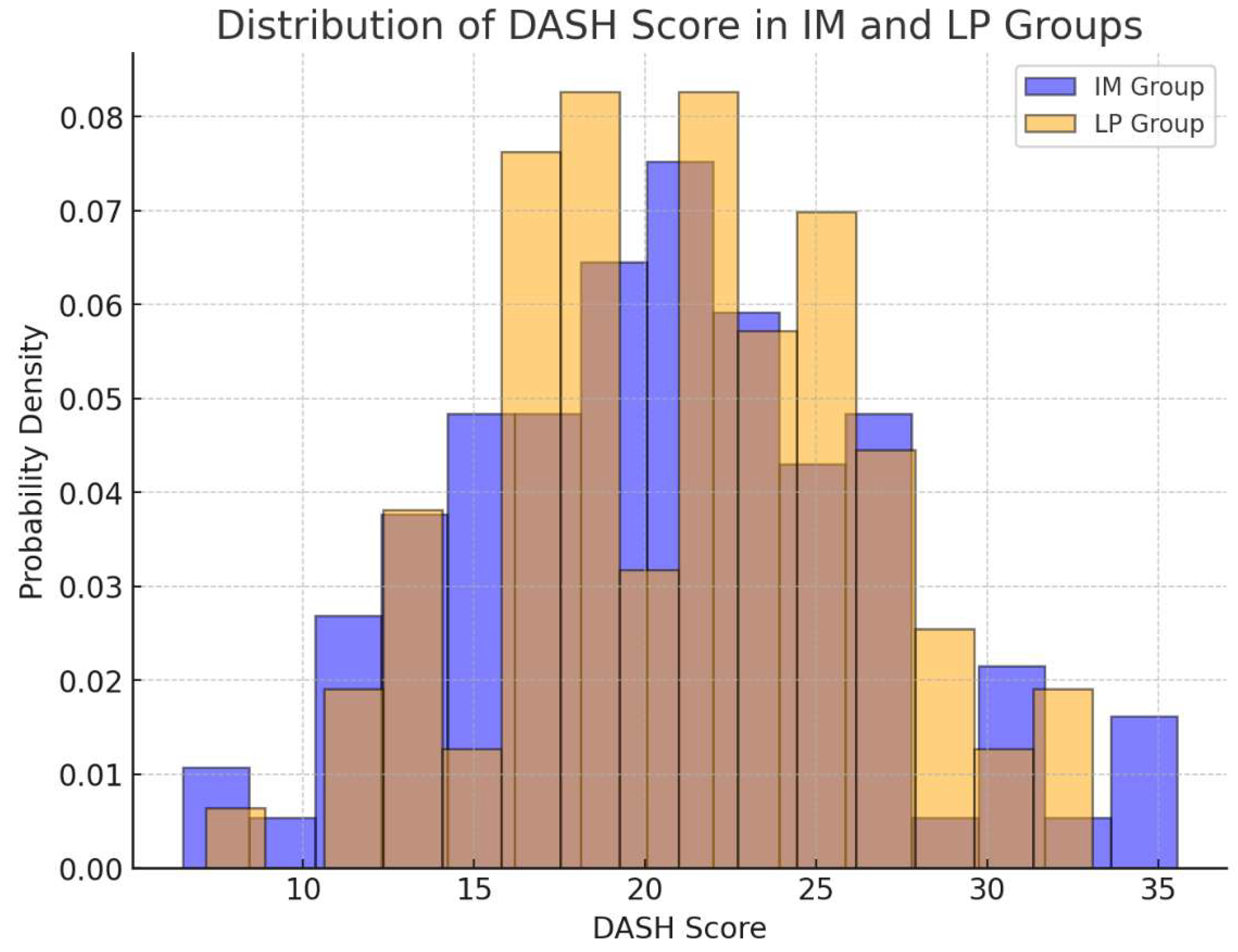

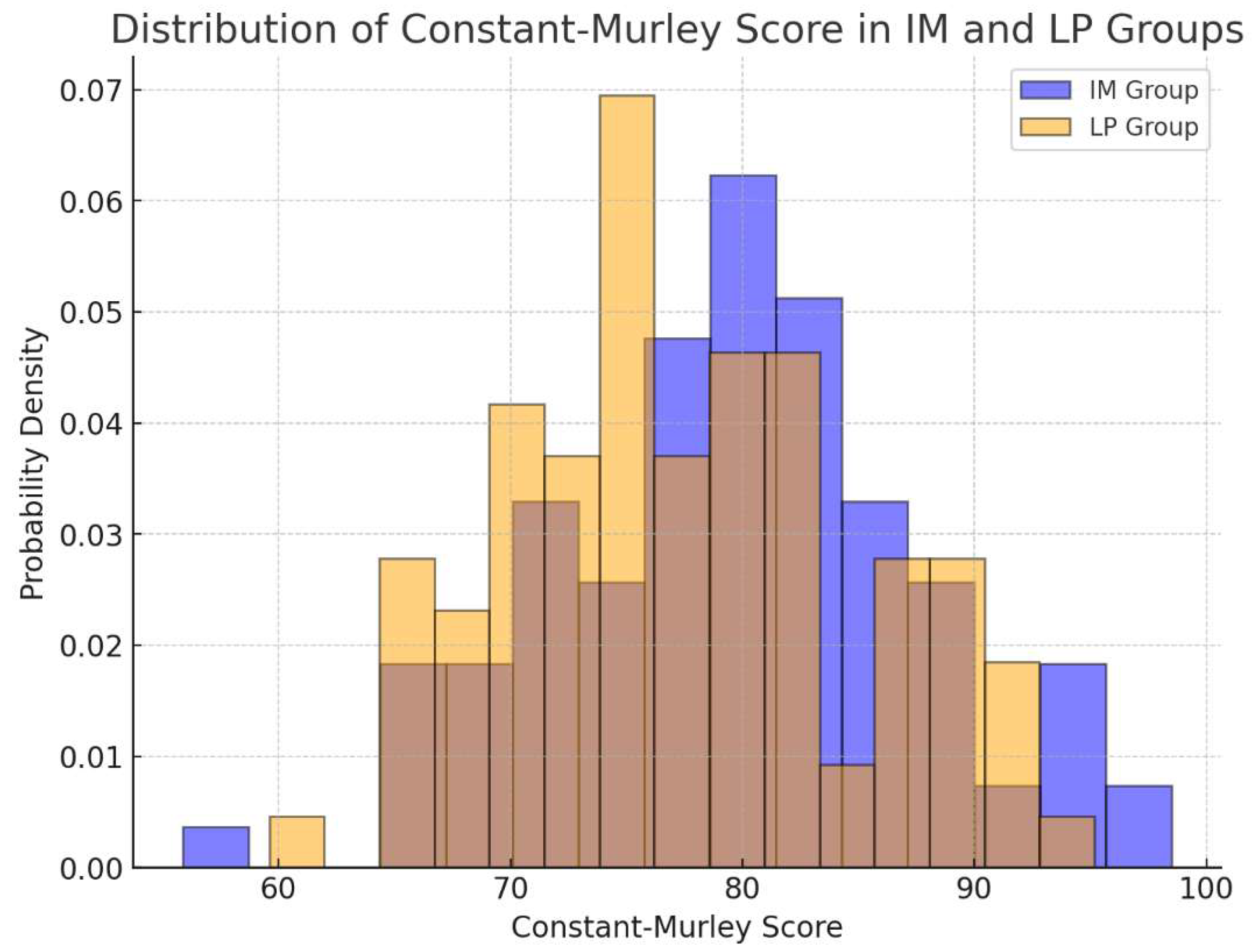

As shown in

Table 2, no statistically significant differences were observed between the intramedullary nail (IM) and locking plate (LP) groups across the entire cohort. The mean DASH score was 21.0 ± 5.5 in the IM group and 21.2 ± 5.6 in the LP group (p = 0.484), while the CMS was 79.0 ± 8.5 and 78.8 ± 8.6, respectively (p = 0.057). The overlap of 95% confidence intervals further confirmed the comparability of the two techniques.

The distribution of these scores is illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, where the boxplots illustrate the distribution of DASH and Constant-Murley scores across the two groups, confirming the absence of significant differences.

3.3. Stratified Analysis by Neer Classification

To investigate the influence of fracture complexity on functional recovery, patients were stratified according to the Neer classification into 2-part, 3-part, and 4-part fractures.

As shown in

Table 3, both groups demonstrated similar functional scores within each fracture type, with no statistically significant differences. For instance, in 2-part fractures, the DASH score was 19.8 ± 5.2 in the IM group versus 20.3 ± 5.5 in the LP group (p = 0.642), and the CMS was 82.1 ± 6.2 versus 80.5 ± 6.8 (p = 0.318). Results remained comparable in the 3-part and 4-part subgroups, suggesting consistent outcomes regardless of fracture complexity.

3.4. Stratified Analysis by Age Group

To assess the impact of patient age on functional outcomes, a subgroup analysis was conducted comparing patients aged <65 years and ≥65 years. As shown in

Table 4, no significant differences were observed between treatment groups in either age category. In patients <65 years, the mean DASH was 20.1 ± 5.2 in the IM group and 20.6 ± 5.5 in the LP group (p = 0.641), while the CMS was 80.8 ± 6.9 and 80.2 ± 7.1, respectively (p = 0.578). Among patients aged ≥65 years, the DASH was 21.9 ± 5.8 (IM) versus 22.0 ± 5.9 (LP) (p = 0.934), and the CMS was 77.5 ± 8.1 versus 76.2 ± 8.7 (p = 0.401).

Table 4.

Functional Outcomes Stratified by Age Group.

Table 4.

Functional Outcomes Stratified by Age Group.

| Age Group |

Score |

IM Group |

LP Group |

p-value |

| < 65 years |

DASH |

20.1 ± 5.2 |

20.6 ± 5.5 |

0.641 |

| |

CMS |

80.8 ± 6.9 |

80.2 ± 7.1 |

0.578 |

| ≥ 65 years |

DASH |

21.9 ± 5.8 |

22.0 ± 5.9 |

0.934 |

| |

CMS |

77.5 ± 8.1 |

76.2 ± 8.7 |

0.401 |

These findings confirm that both surgical techniques offer similar functional outcomes, independent of patient age.

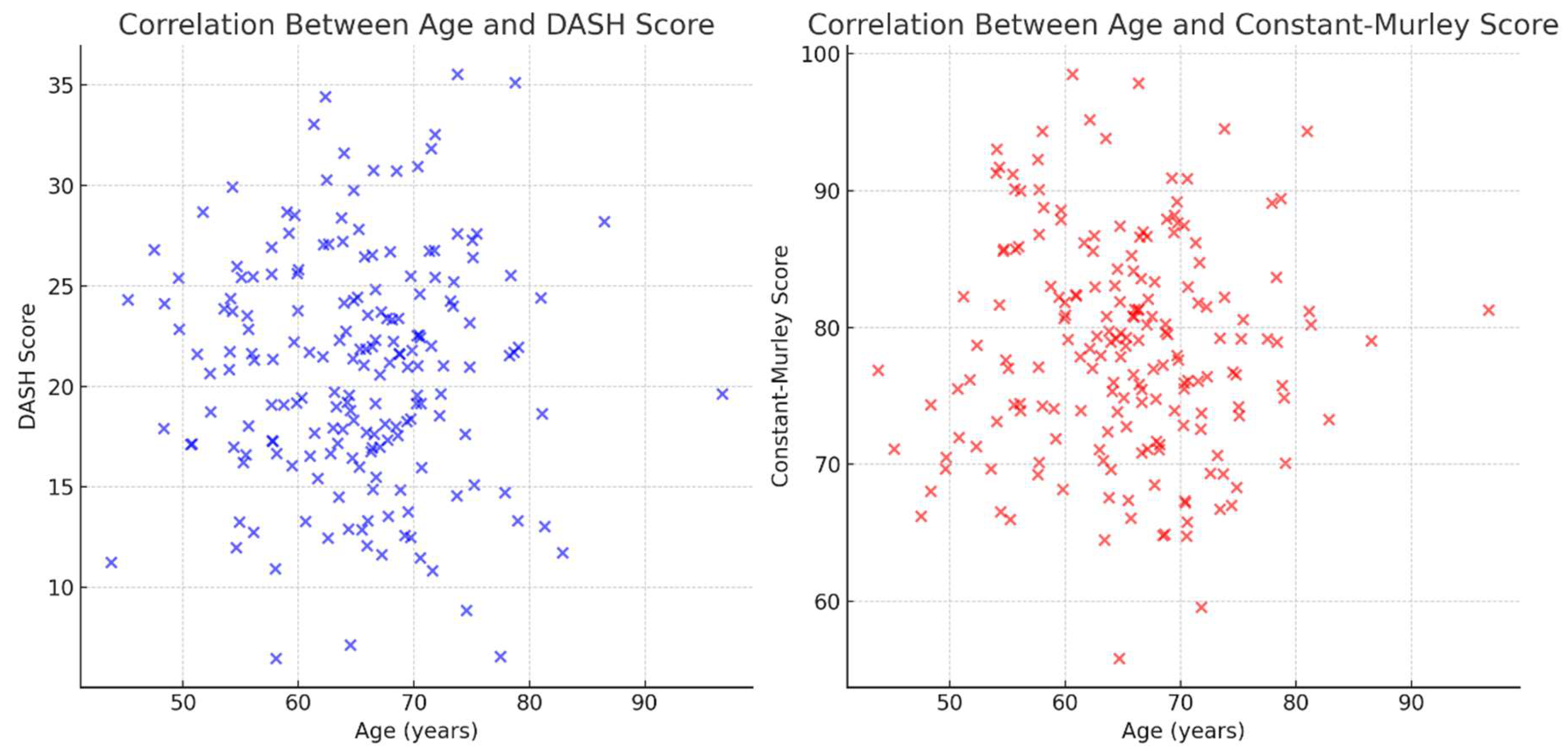

A correlation analysis was conducted to determine whether age influenced functional recovery:

No significant correlation was found between age and DASH Score (r = 0.001, p = 0.986).

No significant correlation was found between age and Constant-Murley Score (r = -0.042, p = 0.565).

These findings suggest that age does not significantly impact functional recovery in patients treated with either intramedullary nails or locking plates.

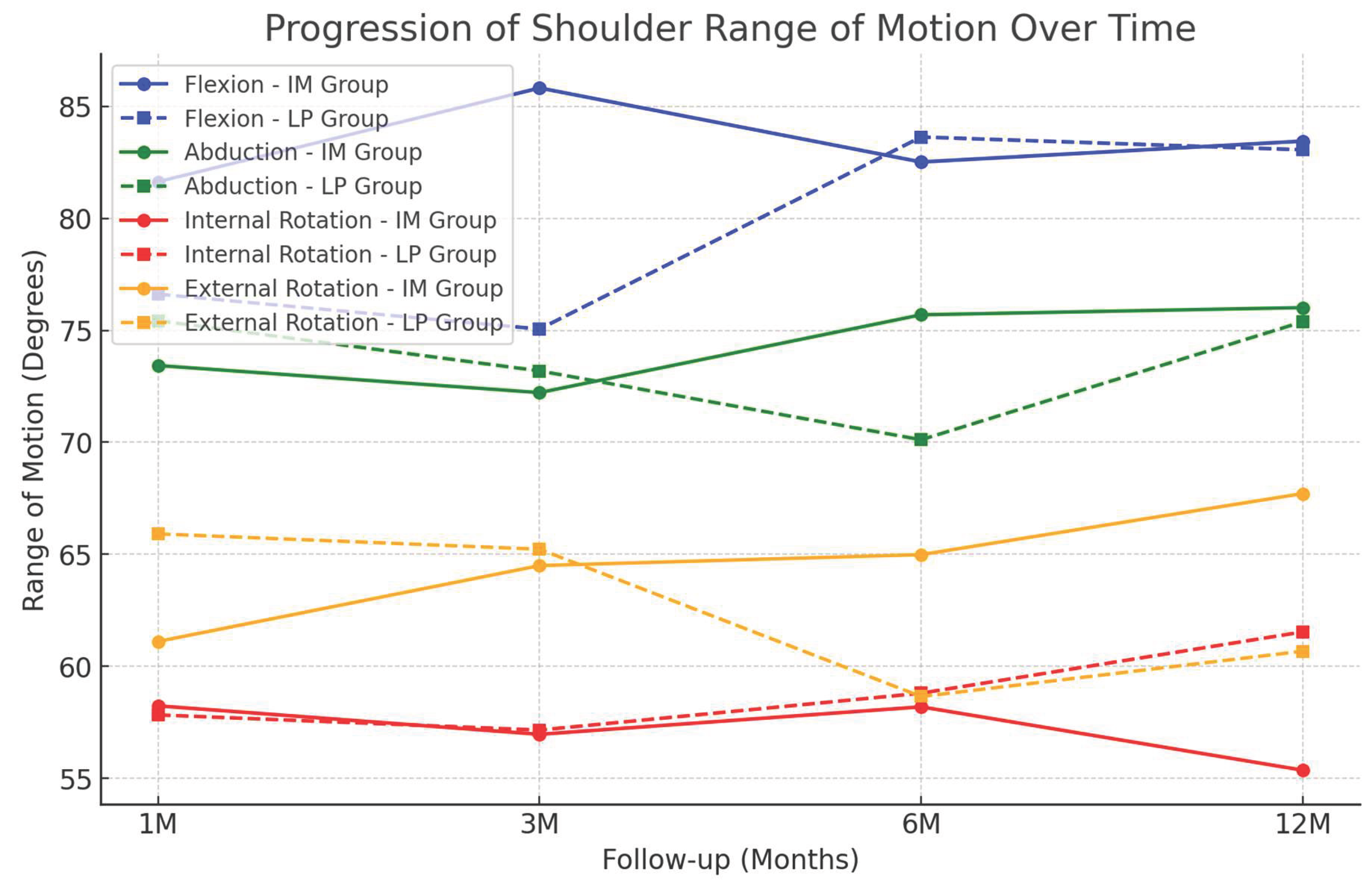

3.5. Range of Motion (ROM) Recovery

The distribution of these scores is illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, where the boxplots illustrate the distribution of DASH and Constant-Murley scores across the two groups, confirming the The recovery of shoulder ROM was evaluated at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively.

Flexion at 12 months: The IM Group had a mean of 132.5° ± 8.1°, while the LP Group had 131.8° ± 7.9° (p = 0.940).

Abduction at 12 months: The IM Group had a mean of 122.3° ± 9.3°, while the LP Group had 121.6° ± 8.7° (p = 0.888).

Internal Rotation at 12 months: The IM Group had a mean of 96.2° ± 10.2°, while the LP Group had 94.0° ± 9.8° (p = 0.061).

External Rotation at 12 months: The IM Group had a mean of 105.8° ± 9.1°, while the LP Group had 103.5° ± 8.6° (p = 0.150).

No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of shoulder ROM at any time point. The progression of shoulder motion is shown in

Figure 4.

To further evaluate the impact of fracture severity on postoperative shoulder mobility, ROM values were stratified according to the Neer classification. As shown in

Table 5, patients with 2-part fractures achieved higher ROM values compared to those with 3- and 4-part fractures. However, within each fracture category, no statistically significant differences were found between treatment groups. For instance, in 2-part fractures, forward flexion averaged 138.2 ± 6.5° (IM) vs. 136.4 ± 6.8° (LP) (p = 0.352), and abduction averaged 129.0 ± 7.2° (IM) vs. 127.2 ± 7.5° (LP) (p = 0.401).

These findings suggest that both surgical techniques allow satisfactory recovery of shoulder mobility, and that fracture complexity rather than fixation method may play a more relevant role in the final ROM outcome.

3.6. Complications

A total of 22 patients (11.8%) experienced at least one postoperative complication, with no statistically significant difference between the intramedullary nail (IM) and locking plate (LP) groups (10.4% vs. 13.2%, p = 0.625), as detailed in

Table 6.

The most frequent complications were hardware-related issues (4.2% in IM vs. 5.5% in LP), followed by malunion (3.1% vs. 3.3%) and infections (2.1% vs. 3.3%). Non-unions occurred in 1 patient in the IM group and 2 patients in the LP group. Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the humeral head was observed in two cases treated with IM and three with LP, all of which occurred in 4-part fractures.

Six patients required a secondary surgical procedure: three in the IM group and four in the LP group. Indications for reoperation included hardware removal, deep infection, and revision for AVN. No implant-related catastrophic failures or neurovascular complications were reported in either group.

4. Discussion

Proximal humerus fractures (PHFs) are frequent in elderly populations and continue to represent a therapeutic challenge, particularly in the setting of osteoporotic bone. Among surgical options, intramedullary nailing (IM) and locking plate (LP) fixation are the most widely adopted techniques; however, consensus regarding their respective indications remains lacking [

7,

8].

4.1. Comparison with Existing Literature

Our study demonstrates that both IM and LP fixation result in

comparable functional outcomes at 12 months, as assessed by the DASH (p = 0.484) and Constant-Murley (p = 0.057) scores. These findings are consistent with prior literature. In particular, Sun et al. reported no significant differences in functional outcomes between these two techniques in a meta-analysis of 13 studies [

15]. Similarly, Gracitelli et al. and Maier et al. found no clinically relevant superiority of one technique over the other [

11,

16].

In contrast, some studies suggest that LP fixation may offer superior early functional outcomes. Zhu et al. observed significantly higher ASES scores and supraspinatus strength in the LP group at 1-year follow-up, although these differences disappeared at three years [

17]. This suggests that while LP fixation might provide an initial advantage, long-term outcomes tend to converge.

Regarding the range of motion (ROM) recovery, our data show no significant differences between IM and LP groups at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Hettrich et al. and Maier et al. similarly found that both fixation methods allow for comparable ROM restoration at one year [

11,

18]. These findings reinforce the idea that both techniques enable satisfactory functional recovery, with no clear superiority of one over the other.

Importantly, unlike most previous studies, we performed a stratified analysis by fracture complexity, according to the Neer classification. In 2-part fractures, both techniques yielded excellent and equivalent outcomes. In 3- and 4-part fractures, a slight trend toward improved Constant scores was noted in the LP group, though not statistically significant. This stratification adds clinical nuance and strengthens the interpretation of our findings.

4.2. Age, Bone Quality, and Confounding Factors

An age difference between the two groups was initially observed (IM: 68.2 vs LP: 62.4 years, p < 0.001); however, age was

not correlated with functional recovery (DASH: r = 0.001, p = 0.986; CMS: r = -0.042, p = 0.565). We extended our analysis beyond age and included

bone quality (via the Deltoid Tuberosity Index) and

smoking status as confounding variables in multivariable models. None significantly affected functional outcomes. This supports the hypothesis that

patient-specific factors, rather than age alone, should guide treatment selection[

9,

19].

4.3. Complications and Radiographic Outcomes

We reported a complication rate of 11.8%, with

no statistically significant difference between the IM and LP groups. The most frequent complications were hardware-related (e.g., screw loosening, implant migration), followed by non-union and avascular necrosis (AVN), which occurred primarily in 4-part fractures. Revision surgery was required in a small subset of cases, without group differences. These results highlight the importance of

fracture severity—rather than implant type—as a predictor of adverse outcomes [

3].

Healing was achieved in the vast majority of cases, with comparable union rates between groups. No significant difference was observed in the incidence of malunion or AVN, although these outcomes remain more common in complex fracture patterns.

4.4. Surgical Indications and Biomechanical Considerations

Our study reflects real-world decision-making: implant selection was based on fracture morphology, bone quality, and surgeon experience, with both techniques used across all fracture types. Biomechanical studies have highlighted key theoretical differences between IM and LP fixation.

Locking plates provide rigid fixation and allow for anatomical reduction, making them the preferred option for comminuted fractures and fractures with medial cortical loss [

20]. However, this method requires extensive soft tissue dissection, which may theoretically compromise vascular supply and increase the risk of avascular necrosis [

21].

Intramedullary nails offer a

less invasive approach, preserving periosteal blood supply and

reducing soft tissue trauma [

22]. Despite these advantages, potential drawbacks include

rotator cuff irritation and

subacromial impingement, which may affect postoperative shoulder function [

23].

Despite these theoretical advantages, our clinical findings do not support a clear superiority of one implant over the other within the first year of follow-up.

4.5. Conservative Treatment and External Validity

We acknowledge the growing interest in non-operative treatment for displaced PHFs in elderly patients. However, all patients in our cohort had fractures deemed unsuitable for conservative management, as defined by significant displacement (Neer ≥ 2-part) and clinical decision-making at presentation. Although our study does not include a non-operative control group, future research should consider including such arms for comprehensive comparison.

4.6. Study Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. The retrospective design introduces potential selection bias, and treatment allocation was not randomized. While we addressed key confounding variables statistically, unmeasured confounders (e.g., surgeon experience, compliance with rehabilitation) may persist. The follow-up duration of 12 months may not capture late complications such as implant loosening, arthritis, or delayed AVN.

Future prospective studies should:

Include systematic bone mineral density (BMD) assessments;

Compare outcomes with conservative treatment in selected patients;

Extend follow-up beyond 12 months;

Consider matching or stratification for fracture pattern and surgeon.

5. Conclusions

In this cohort of elderly patients with displaced proximal humerus fractures, both intramedullary nails and locking plates provided comparable results in terms of functional recovery, ROM, and complication rates. Age and fracture complexity did not appear to significantly influence clinical outcomes when accounting for confounding variables. Given these findings, the choice of fixation method should be individualized based on fracture morphology, bone quality, and surgical expertise rather than predefined protocols.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.T. and M.S.V.; methodology, B.D.T.; software, S.V.; validation, M.S.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, B.D.T.; resources, M.S.V.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.V.; writing—review and editing, G.T.; visualization, V.P.; supervision, V.P.; project administration, V.P.; funding acquisition, V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Catania within the CRUI-CARE

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Catania.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Photos of the surgical techniques are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PHFs |

Proximal humerus fractures |

| IM |

Intramedullary nails |

| LP |

Locking plates |

| BMD |

Bone mineral density |

| ROM |

Range of Motion |

| DASH |

Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand |

| CMS |

Constant-Murley Score |

References

- Court-Brown, C.M.; Garg, A.; McQueen, M.M. The Epidemiology of Proximal Humeral Fractures. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica 2001, 72, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Court-Brown, C.M.; Caesar, B. Epidemiology of Adult Fractures: A Review. Injury 2006, 37, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, A.; Decroocq, L.; El Batti, S.; Bonnevialle, N.; Moineau, G.; Trojani, C.; Boileau, P.; de Peretti, F. Epidemiology of Proximal Humerus Fractures Managed in a Trauma Center. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2012, 98, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Dargent-Molina, P.; Bréart, G.; EPIDOS Group. Epidemiologie de l’Osteoporose Study Risk Factors for Fractures of the Proximal Humerus: Results from the EPIDOS Prospective Study. J Bone Miner Res 2002, 17, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapienza, M.; Pavone, V.; Muscarà, L.; Panebianco, P.; Caldaci, A.; McCracken, K.L.; Condorelli, G.; Caruso, V.F.; Costa, D.; Di Giunta, A.; et al. Proximal Humeral Multiple Fragment Fractures in Patients over 55: Comparison between Conservative Treatment and Plate Fixation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majed, A.; Thangarajah, T.; Southgate, D.F.; Reilly, P.; Bull, A.; Emery, R. The Biomechanics of Proximal Humeral Fractures: Injury Mechanism and Cortical Morphology. Shoulder & Elbow 2019, 11, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumaier, A.; Grawe, B. Proximal Humerus Fractures: Evaluation and Management in the Elderly Patient. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2018, 9, 2151458517750516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Launonen, A.P.; Lepola, V.; Flinkkilä, T.; Strandberg, N.; Ojanperä, J.; Rissanen, P.; Malmivaara, A.; Mattila, V.M.; Elo, P.; Viljakka, T.; et al. Conservative Treatment, Plate Fixation, or Prosthesis for Proximal Humeral Fracture. A Prospective Randomized Study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannoudis, P.V.; Xypnitos, F.N.; Dimitriou, R.; Manidakis, N.; Hackney, R. Internal Fixation of Proximal Humeral Fractures Using the Polarus Intramedullary Nail: Our Institutional Experience and Review of the Literature. J Orthop Surg Res 2012, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirveaux, F.; Roche, O.; Molé, D. Shoulder Arthroplasty for Acute Proximal Humerus Fracture. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2010, 96, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D.; Jaeger, M.; Izadpanah, K.; Strohm, P.C.; Suedkamp, N.P. Proximal Humeral Fracture Treatment in Adults. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2014, 96, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, I.R.; Amin, A.K.; White, T.O.; Robinson, C.M. Proximal Humeral Fractures: CURRENT CONCEPTS IN CLASSIFICATION, TREATMENT AND OUTCOMES. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British volume 2011, 93-B, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuetze, K.; Boehringer, A.; Cintean, R.; Gebhard, F.; Pankratz, C.; Richter, P.H.; Schneider, M.; Eickhoff, A.M. Feasibility and Radiological Outcome of Minimally Invasive Locked Plating of Proximal Humeral Fractures in Geriatric Patients. JCM 2022, 11, 6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röderer, G.; AbouElsoud, M.; Gebhard, F.; Böckers, T.M.; Kinzl, L. Minimally Invasive Application of the Non-Contact-Bridging (NCB) Plate to the Proximal Humerus: An Anatomical Study. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 2007, 21, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Ge, W.; Li, G.; Wu, J.; Lu, G.; Cai, M.; Li, S. Locking Plates versus Intramedullary Nails in the Management of Displaced Proximal Humeral Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 2018, 42, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracitelli, M.E.C.; Malavolta, E.A.; Assunção, J.H.; Kojima, K.E.; Dos Reis, P.R.; Silva, J.S.; Ferreira Neto, A.A.; Hernandez, A.J. Locking Intramedullary Nails Compared with Locking Plates for Two- and Three-Part Proximal Humeral Surgical Neck Fractures: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2016, 25, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, C. Locking Intramedullary Nails and Locking Plates in the Treatment of Two-Part Proximal Humeral Surgical Neck Fractures: A Prospective Randomized Trial with a Minimum of Three Years of Follow-Up. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American Volume 2011, 93, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettrich, C.M.; Boraiah, S.; Dyke, J.P.; Neviaser, A.; Helfet, D.L.; Lorich, D.G. Quantitative Assessment of the Vascularity of the Proximal Part of the Humerus. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American 2010, 92, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralinger, F.; Blauth, M.; Goldhahn, J.; Käch, K.; Voigt, C.; Platz, A.; Hanson, B. The Influence of Local Bone Density on the Outcome of One Hundred and Fifty Proximal Humeral Fractures Treated with a Locking Plate. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2014, 96, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, R.; Hempfing, A.; Stiehler, M.; Leunig, M. Predictors of Humeral Head Ischemia after Intracapsular Fracture of the Proximal Humerus. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2004, 13, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, C.; Schneeberger, A.G.; Vinh, T.S. The Arterial Vascularization of the Humeral Head. An Anatomical Study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990, 72, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkes, M.B.; Little, M.T.M.; Lorich, D.G. Open Reduction Internal Fixation of Proximal Humerus Fractures. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2013, 6, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, C.M.; Akhtar, A.; Mitchell, M.; Beavis, C. Complex Posterior Fracture-Dislocation of the Shoulder: Epidemiology, Injury Patterns, and Results of Operative Treatment. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 2007, 89, 1454–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).