Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

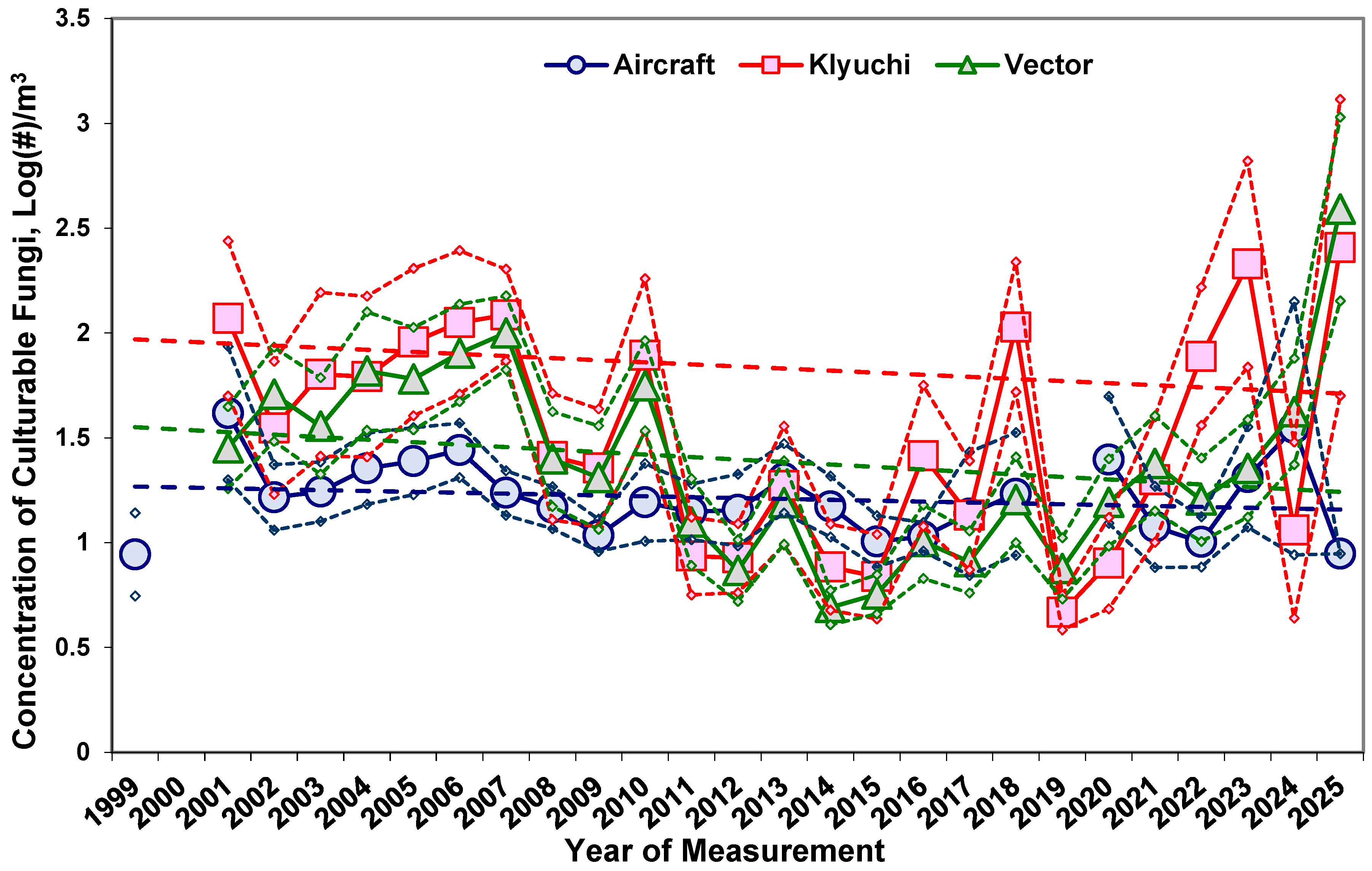

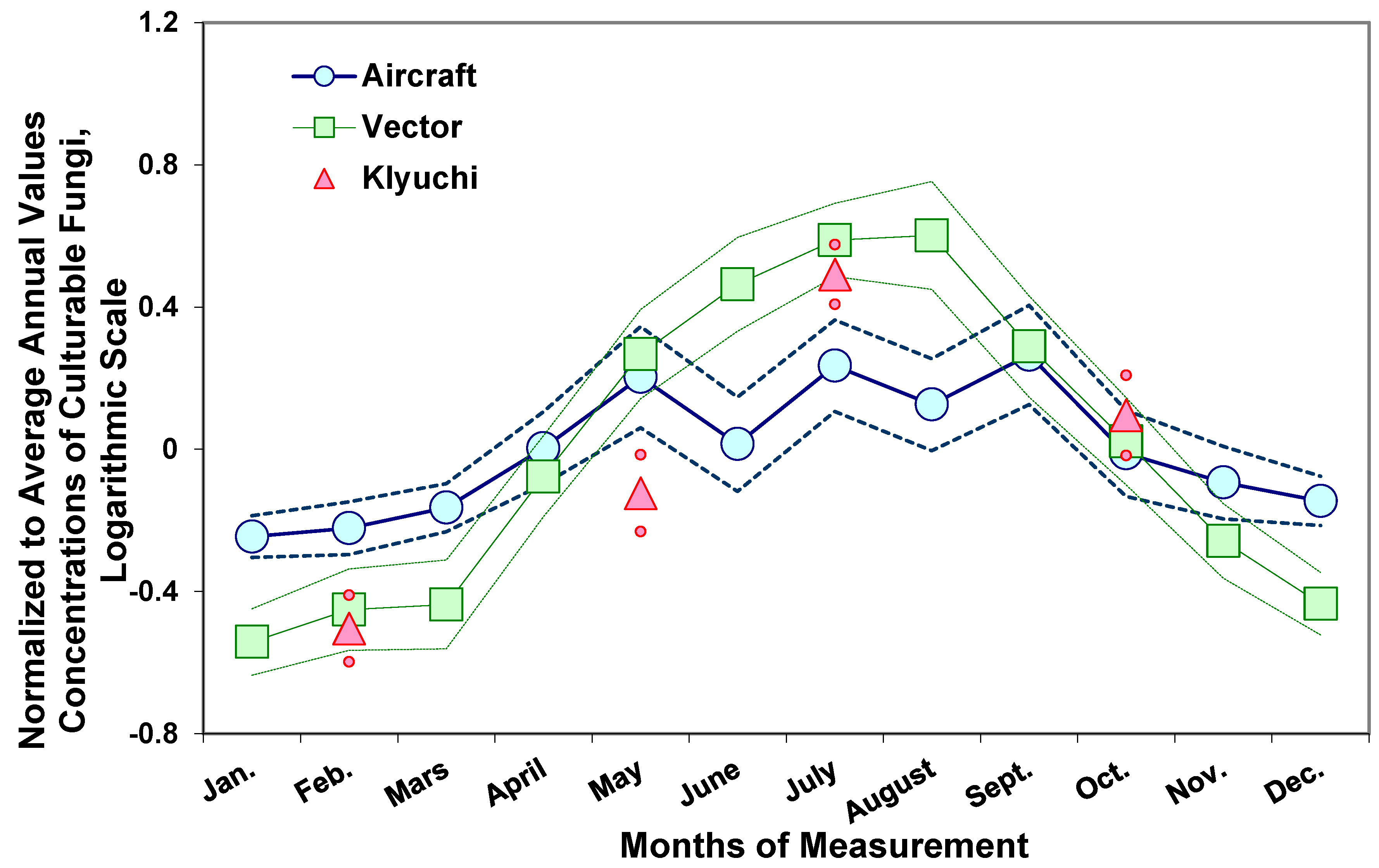

3. Fungi in Atmospheric Aerosols of Western Siberia

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Dampness and Mould. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789289041683 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Šantl-Temkiv, T.; Sikoparija, B.; Maki, T.; Carotenuto, F.; Amato, P.; Yao, M.; Morris, C.E.; Schnell, R.; Jaenicke, R.; Pöhlker, C.; et al. Bioaerosol field measurements: Challenges and perspectives in outdoor studies. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 520–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, P.H. Microbiology of atmosphere. Leonard Hill: London, Great Britain, 1961.

- Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J.; Pickersgill, D.A.; Després, V.R.; Pöschl, U. High diversity of fungi in air particulate matter. PNAS 2009, 106, 12814–12819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Després, V.R.; Huffman, J.A.; Burrows, S.M.; Hoose, C.; Safatov, A.S.; Buryak, G.; Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J.; Elbert, W.; Andreae, M.O.; Pöschl, U.; Jaenicke, R. Primary Biological Aerosols in the Atmosphere: A review. Tellus 2012, 64, 15598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J.; Burrows, S.M.; Xie, Z.; Engling, G.; Solomon, P.A.; Fraser, M.P.; Mayol-Bracero, O.L.; Artaxo, P.; Begerow, D.; Conrad, R.; et al. Biogeography in the air: Fungal diversity over land and oceans. Biogeoscience 2012, 9, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Li, Y.; Xie, W.; Lu, R.; Mu, F.; Bai, W.; Du, S. Temporal-spatial variations of fungal composition in PM2.5 and source tracking of airborne fungi in mountainous and urban regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 708, 135027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.K.M.; Hovmøller, M.S. Aerial dispersal of pathogens on the global and continental scales and its impact on plant disease. Science 2002, 297, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobziar, L.N.; Thompson, G.R., III. Wildfire smoke, a potential infectious agent. Bacteria and fungi are transported in wildland fire smoke emissions. Science 2020, 370, 1408–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewling, Ł.; Magyar, D.; Chłopek, K.; Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Gwiazdowska, J.; Siddiquee, A.; Ianovici, N.; Kasprzyk, I.; Wójcik, M.; Lafférsová, J.; et al. Bioaerosols on the atmospheric super highway: An example of long distance transport of Alternaria spores from the Pannonian Plain to Poland. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 819, 153148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodó, X.; Pozdniakova, S.; Borràs, S.; Matsuki, A.; Tanimoto, H.; Armengol, M.; Pey, I.; Vila, J.; Muñoz, L.; Santamaria, S.; et al. Microbial richness and air chemistry in aerosols above the PBL confirm 2,000-km long-distance transport of potential human pathogens. PNAS 2024, 121, e2404191121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobzar, B.N. Fungal spores and climate change. Meditsina Kyrgyzstana 2016, 3, 22–26, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Elbert, W.; Taylor, P.E.; Andreae, M.O.; Pöschl, U. Contribution of fungi to primary biogenic aerosols in the atmosphere: Wet and dry discharged spores, carbohydrates, and inorganic ions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007, 7, 4569–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, C.; Oliva, J.; Martínez de Aragón, J.; Alday, J.G.; Parladé, J.; Pera, J.; Bonet, J.A. Mushroom emergence detected by combining spore trapping with molecular techniques. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00600-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsante, A.N.; Thornton, D.C.O.; Brooks, S.D. Ocean Aerobiology. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 764178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duquenne, P.; Simon, X.; Coulais, C.; Koehler, V.; Degois, J.; Facon, B. Bioaerosol exposure during sorting of municipal solid, commercial and industrial waste: Concentration levels, size distribution, and biodiversity of airborne fungal. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryzhkin, D.V.; Elanskii, S.N.; Zheltikova, T.M. Monitoring the concentration of spores of Cladosporium and Alternaria fungi in the atmospheric air of Moscow. Atmosfera. Pulmanologiya i allergologiya 2002, 2, 30–31, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Lagomarsino Oneto, D.; Golan, J.; Mazzino, A.; Pringlec, A.; Seminara, A. Timing of fungal spore release dictates survival during atmospheric transport. PNAS 2020, 117, 5134–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fu, H. Fungal Spore Aerosolization at Different Positions of a Growing Colony Blown by Airflow. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 2826–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbs, N.; Barbosa, C.G.G.; Brill, S.; Walter, D.; Ditas, F.; de Oliveira Sá, M.; de Araújo, A.C.; de Oliveira, L.R.; Godoi, R.H.M.; Wolff, S.; et al. Aerosol measurement methods to quantify spore emissions from fungi and cryptogamic covers in the Amazon. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020, 13, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaimin, A.Z.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Shivanand, P. A critical review on bioaerosols—Dispersal of crop pathogenic microorganisms and their impact on crop yield. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 587–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, D.; Valencia, R.M.; Molnár, T.; Vega, A.; Sagüés, E. Daily and seasonal variations of Alternaria and Cladosporium airborne spores in León (North-West, Spain). Aerobiologia 1998, 14, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, M.; Levetin, E. Effects of meteorological conditions on spore plumes. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2002, 46, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safatov, A.S.; Teplyakova, T.V.; Belan, B.D.; Buryak, G.A.; Vorob’eva, I.G.; Mikhailovskaya, I.N.; Panchenko, M.V.; Sergeev, A.N. Atmospheric Aerosol Fungi Concentration and Diversity in the South of Western Siberia. Atmos. Oceanic Optics. 2010, 23, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aira, M.-J.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.-J.; Fernández-González, M.; Seijo, C.; et al. Spatial and temporal distribution spores in the Iberian Peninsula atmosphere, and meteorological relationships: 1993–2009. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2013. V. 57 (2). P. 265–274. [CrossRef]

- Vorob’eva, I.G.; Teplyakova, T.V.; Safatov, A.S.; Buryak, G.A. Complexes of microscopic fungi in air aerosols of the south of Western Siberia. Uspekhi meditsinskoy mikologii 2014, 13, 83–84, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Sadyś, M.; Strzelczak, A.; Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Kennedy, R. Application of redundancy analysis for aerobiological data. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2015, 59, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apangu, G.P.; Frisk, C.A.; Adams-Groom, B.; Petch, G.M.; Hanson, M.; Skjøth, C.A. Using qPCR and microscopy to assess the impact of harvesting and weather conditions on the relationship between Alternaria alternata and Alternaria spp. spores in rural and urban atmospheres. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2023, 67, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishwakarma, Y.K.; Ram, K.; Gogoi, M.M.; Banerjee, T.; Singh, R.S. Size-segregated characteristics of bioaerosols during foggy and non-foggy days of winter, meteorological implications, and health risk assessment. Environ. Sci.: Adv. 2024, 3, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidel, B.F.F.; Bouziane, H.; del Mar Trigo, M.; El Haskouri, F.; Bardei, F.; Redouane, A.; Kadiri, M.; Riadi, H.; Kazzaz, M. Airborne fungal spores of Alternaria, meteorological parameters and predicting variables. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2015, 59, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusareva, E.S.; Acerbi, E.; Lau, K.J.X.; Luhung, I.; Premkrishnan, B.N.V.; Kolundžija, S.; Purbojati, R.W.; Wong, A.; Houghton, J.N.I.; Miller, D.; et al. Microbial communities in the tropical air ecosystem follow a precise diel cycle. PNAS 2019, 116, 23299–23308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Alonso, M.; Boldeanu, M.; Koritnik, T.; Gonçalves, J.; Belzner, L.; Stemmler, T.; Gebauer, R.; Grewling, Ł.; Tummon, F.; Maya-Manzano, J.M.; et al. Alternaria spore exposure in Bavaria, Germany, measured using artificial intelligence algorithms in a network of BAA500 automatic pollen monitors. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 861, 160180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, K.J.; Jeong, S.B.; Lim, C.E.; Lee, G.W.; Lee, B.U. Diurnal Variation in Concentration of Culturable Bacterial and Fungal Bioaerosols in Winter to Spring Season. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaenicke, R.; Matthias-Maser, S.; Gruber, S. Omnipresence of biological material in the atmosphere. Environ. Chem. 2007, 4, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artaxo, P.; Maenhaut, W.; Storms, H.; van Grieken, R. Aerosol characteristics and sources for the Amazon basin during the wet season. J. Geophys. Res. 1990, 95, 16971–16985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artaxo, P.; Storms, H.; Bruynseels, F.; van Grieken, R.; Maenhaut, W. Composition and sources of aerosols from the Amazon basin. J. Geophys. Res. 1988, 93, 1605–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, J.A.; Sinha, B.; Garland, R.M.; Snee-Pollmann, A.; Gunthe, S.S.; Artaxo, P.; Martin, S.T.; Andreae, M.O.; Pöschl, U. Size distributions and temporal variations of biological aerosol particles in the Amazon rainforest characterized by microscopy and real-time UV-APS fluorescence techniques during AMAZE-08. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 11997–12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, С.L.; Spracklen, D.V. Atmospheric budget of primary biological aerosol particles from fungal spores. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, L09806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesartic, A.; Lohmann, U.; Storelvmo, T. Modelling the impact of fungal spore ice nuclei on clouds and precipitation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 014029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarakainen, P.; Meklin, T.; Rintala, H.; Hyvärinen, A.; Kärkkäinen, P.; Vepsäläinen, A.; Hirvonen, M.-R.; Nevalainen, A. Seasonal variation in airborne microbial concentrations and diversity at landfill, urban and rural sites. Clean 2008, 36, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.U.; Lee, G.; Heo, K.J. Concentration of culturable bioaerosols during winter. J. Aerosol Sci. 2016, 94, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tignat-Perrier, R.; Dommergue, A.; Thollot, A.; Magand, O.; Vogel, T.M.; Larose, C. Microbial functional signature in the atmospheric boundary layer. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 6081–6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C.; Reponen, T.; Lee, T.; Iossifova, Y.; Levin, L.; Adhikari, A.; Grinshpun, S.A. Temporal and spatial variation of indoor and outdoor airborne fungal spores, pollen and (1→3)-β-D-glucan. Aerobiologia 2009, 25, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ran, P.; Ho, K.; Lu, W.; Li, B.; Gu, Z.; Song, C.; Wang, J. Concentrations and size distributions of airborne microorganisms in Guangzhou during summer. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2012, 12, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, R.M.; Clements, N.; Emerson, J.B.; Wiedinmyer, C.; Hannigan, M.P.; Fierer, N. Seasonal variability in bacterial and fungal diversity of the near-surface atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 12097–12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, V.D.; Hoang, S.M.T.; Hung, N.T.Q.; Ky, N.M.; Gwi-Nam, B.; Ki-hong, P.; Chang, S.W.; Bach, Q.-V.; Nhu-Trang, T.-T.; Nguyen, D.D. Characteristics of airborne bacteria and fungi in the atmosphere in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam—A case study over three years. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 145, 104819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.L.T.; Bauer, H.; Cardoso, M.R.A.; Alves, M.R.; Pukinskas, S.; Matos, D.; Melhem, M.; Puxbaum, H. Indoor and outdoor atmospheric fungal spores in the São Paulo metropolitan area (Brazil): Species and numeric concentrations. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2010, 54, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya-Manzano, J.M.; Muñoz-Triviño, M.; Fernández-Rodríguez, S.; Silva-Palacios, S.I.; Gonzalo-Garijo, A.; Tormo-Molina, R. Airborne Alternaria conidia in Mediterranean rural environments in SW of Iberian Peninsula and weather parameters that influence their seasonality in relation to climate change. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrri, I.; Kapsanaki-Gotsi, E. Diversity and annual fluctuations of culturable airborne fungi in Athens, Greece: A 4-year study. Aerobiologia 2012, 28, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.J.; Sadyś, M.; Skjøth, C.A.; Healy, D.A.; Kennedy, R.; Sodeau, J.R. Atmospheric concentrations of Alternaria, Cladosporium, Ganoderma and Didymella spores monitored in Cork (Ireland) and Worcester (England) during the summer of 2010. Aerobiologia. 2014, 30, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Aghaei-Gharehbolagh, S.; Aslani, N.; Razzaghi-Abyaneh, M. Investigation on distribution of airborne fungi in outdoor environment in Tehran, Iran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2014, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgül, H.; Yılmazkaya, D.; Akata, I.; Tosunoğlu, A.; Bıçakçı, A. Determination of airborne fungal spores of Gaziantep (SE Turkey). Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindt, C.; Besancenot, J.-P.; Thibaudon, M. Airborne Cladosporium fungal spores and climate change in France. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irga, P.J.; Torpy, F.R. A survey of the aeromycota of Sydney and its correspondence with environmental conditions: Grass as a component of urban forestry could be a major determinant. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Blanco, X.; Tejera, L.; Beri, Á. First volumetric record of fungal spores in the atmosphere of Montevideo City, Uruguay: A 2-year survey. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Pereira, A.M.; De Linares, C.; Rosario, D.; Belmonte, J. Temporal trends of the airborne fungal spores in Catalonia (NE Spain), 1995–2013. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadyś, M.; Kaczmarek, J.; Grinn-Gofron, A.; et al. Dew point temperature affects ascospore release of allergenic genus Leptosphaeria. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, S.F.; de la Cruz, D.R.; Sánchez, J.S.; Reyes, E.S. Analysis of the airborne fungal spores present in the atmosphere of Salamanca (MW Spain): A preliminary survey. Aerobiologia 2019, 35, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Nowosad, J.; Bosiacka, B.; Camacho, I.; Pashley, C.; Belmonte, J.; de Linares, C.; Ianovici, N.; Manzano, J.M.M.; Sadyś, M.; et al. Airborne Alternaria and Cladosporium fungal spores in Europe: Forecasting possibilities and relationships with meteorological parameters. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarda-Estève, R.; Baisnée, D.; Guinot, B.; Sodeau, J.; O’Connor, D.; Belmonte, J.; Besancenot, J.-P.; Petit, J.-E.; Thibaudon, M.; Olive, G.; et al. Variability and Geographical Origin of Five Years Airborne Fungal Spore Concentrations Measured at Saclay, France from 2014 to 2018. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ščevková, J.; Hrabovský, M.; Kováč, J.; Rosa, S. Intradiurnal variation of predominant airborne fungal spore biopollutants in the Central European urban environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 34603–34612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewling, Ł.; Bogawski, P.; Szymanska, A.; Nowak, M.; Kostecki, Ł.; Smith, M. Particle size distribution of the major Alternaria alternata allergen, Alt a 1, derived from airborne spores and subspore fragments. Fungal Biology 2020, 124, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, Y.; Skjøth, C.A.; Hertel, O.; Rasmussen, K.; Sigsgaard, T.; Gosewinkel, U. Airborne Cladosporium and Alternaria spore concentrations through 26 years in Copenhagen, Denmark. Aerobiologia 2020, 36, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, M.A.; Berlin, A.; Boberg, J.; Oliva, J. Vegetation type determines spore deposition within a forest–agricultural mosaic landscape. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayad, R.K.; Al-Thani, R.F.; Al-Naemi, F.A.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.H. Diversity, Concentration and Dynamics of Culturable Fungal Bioaerosols at Doha, Qatar. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galán, C.; Smith, M.; Damialis, A.; Frenguelli, G.; Gehrig, R.; Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Kasprzyk, I.; Magyar, D.; Oteros, J.; Šaulienė, I.; et al. Airborne fungal spore monitoring: Between analyst proficiency testing. Aerobiologia 2021, 37, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk, I.; Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Ćwik, A.; Kluska, K.; Cariñanos, P.; Wójcik, T. Allergenic fungal spores in the air of urban parks. Aerobiologia 2021, 37, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Bogawski, P.; Bosiacka, B.; Nowosad, J.; Camacho, I.; Sadyś, M.; Skjøth, C.A.; Pashley, C.H.; Rodinkova, V.; Çeter, T.; et al. Abundance of Ganoderma sp. in Europe and SW Asia: Modelling the pathogen infection levels in local trees using the proxy of airborne fungal spore concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 793, 148509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageen, Y.; Asemoloye, M.D.; Põlme, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Ramteke, P.; Pecoraro, L.W. Analysis of culturable airborne fungi in outdoor environments in Tianjin, China. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageen, Y.; Wang, X.; Pecoraro, L. Seasonal variation of airborne fungal diversity and community structure in urban outdoor environments in Tianjin, China. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1043224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Pereira, A.M.; De Linares, C.; Canela, M.; Belmonte, J. Spatial distribution of fungi from the analysis of aerobiological data with a gamma function. Aerobiologia 2021, 37, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampopoulos, A.; Damialis, A.; Vokou, D. Spatiotemporal assessment of aeromycoflora under differing urban green space, sampling height, and meteorological regimes: The atmospheric fungiscape of Thessaloniki, Greece. Int J. Biometeorol. 2022, 66, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M.C.; Petch, G.M.; Ottosen, T.B.; Skjøth, C.A. Climate change impact on fungi in the atmospheric microbiome. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 830, 154491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya-Manzano, J.M.; Fernández-Rodríguez, S.; Hernández-Trejo, F.; Díaz-Pérez, G.; Gonzalo-Garijo, Á.; Silva-Palacios, I.; Muñoz-Rodrígue, A.F.; Tormo-Molina, R. Seasonal Mediterranean pattern for airborne spores of Alternaria. Aerobiologia 2012, 28, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantoani, M.C.; Emygdio, A.P.M.; Degobbi, C.; Ribeiro Sapucci, C.; Guerra, L.C.C.; Dias, M.A.F.S.; Dias, P.L.S.; Zanetti, R.H.S.; Rodrigues, F.; Araujo, G.G.; Silva, D.M.C.; Duo Filho, V.B.; Boschilia, S.M.; et al. Rainfall effects on vertical profiles of airborne fungi over a mixed land-use context at the Brazilian Atlantic Forest biodiversity hotspot. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 2023, 331, 109352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlogeloa, O.; Fitchett, J.M. Climate and human health: A review of publication trends in the trends in the International Journal of Biometeorology. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2023, 67, 933–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Blanco-Alegre, C.; Vega-Maray, A.M.; Valencia-Barrera, R.M.; Molnár, T.; Fernández-González, D. Effect of prevailing winds and land use on Alternaria airborne spore load. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, R.F.R.; Saltos, H.T.V. Airborne bacteria and fungi in coastal Ecuador: A correlation analysis with meteorological factors. Vis. Sustain. 2024, 22, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaz, E.; Menteşe, S.; Bayram, A.; Kara, M.; Elbir, T. Seasonal variability of airborne mold concentrations as related to dust in a coastal urban area in the Eastern Mediterranean. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 40717–40731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Espinosa, K.C.; Aira, M.J.; Fernández-González, M.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J. Airborne Alternaria Spores: 70 Annual Records in Northwestern Spain. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabıcak, S.; Bıyıklıoğlu, O.; Farooq, Q.; Oteros, J.; ·Galán, C.; Çeter, T. Investigating the relationship between atmospheric concentrations of fungal spores and local meteorological variables in Kastamonu, Türkiye. Aerobiologia 2025, 41, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Bosiacka, B. Effects of meteorological factors on the composition of selected fungal spores in the air. Aerobiologia 2015, 31, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troutt, C.; Levetin, E. Correlation of spring spore concentrations and meteorological conditions in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2001, 45, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stennett, P.J.; Beggs, P.J. Alternaria spores in the atmosphere of Sydney, Australia, and relationships with meteorological factors. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2004, 49, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshareef, F.; Robson, G.D. Prevalence, persistence, and phenotypic variation of Aspergillus fumigatus in the outdoor environment in Manchester, UK, over a 2-year period. Med. Mycol. 2014, 52, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, E.; Caeiro, E.; Todo-Bom, A.; Ferro, R.; Dionísio, A.; Duarte, A.; Gazarini, L. The influence of meteorological parameters on Alternaria and Cladosporium fungal spore concentrations in Beja (Southern Portugal): Preliminary results. Aerobiologia 2018, 34, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muafa, M.H.M.; Quach, Z.M.; Al-Shaarani, A.A.Q.A.; Nafis, M.M.H.; Pecoraro, L. The influence of car traffic on airborne fungal diversity in Tianjin. China Mycology 2024, 15, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, S.N.; Fatima, K.; Al-Frayh, A.; Al-Sedairy, S.T. Prevalence of airborne basidospores in three coastal cities of Saudi Arabia. Aerobiologia 2005, 21, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, A.D.; Ruiz, S.S.; Gutiérrez Bustillo, M.; Morales, P.C. Study of airborne fungal spores in Madrid, Spain. Aerobiologia 2006, 22, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, J.; Hutchenson, P.S.; Slavin, R.G. Aspergillus fumigatus spore concentration in outside air: Cardiff and St Louis compared. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1984, 14, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Antoni Zoppas, B.C.; Valencia-Barrera, R.M.; Vergamini Duso, S.M.; Fernández-González, D. Fungal spores prevalent in the aerosol of the city of Caxias do Sul, Grande do Sul, Brazil, over a 2-year period (2001-2002). Aerobiologia 2006, 22, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro, H.; Delgado, J.L.; Abreu, I. The effects of meteorological factors on airborne fungal spore concentration in two areas differing in urbanization level. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2009, 53, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaguer, M.; Rojas, T.I.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J.; Aira, M.-J. Airborne fungal succession in a rice field of Cuba. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2012, 133, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Gupta-Bhattacharya, S. Monitoring and assessment of airborne fungi in Kolkata, India, by viable and non-viable air sampling methods. Environ. Monitor. Assess. 2012, 184, 4671–4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaguer, M.; Aira, M.-J.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J.; Rojas, T.I. Temporal dynamics of airborne fungi in Havana (Cuba) during dry and rainy seasons: Influence of meteorological parameters. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014, 58, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ščevková, J.; Dušička, J.; Mičieta, K.; Aira, M.-J. The effects of recent changes in air temperature on trends in airborne Alternaria, Epicoccum and Stemphylium spore seasons in Bratislava (Slovakia). Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaguer, M.; Rojas-Flores, T.I.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J.; Aira, M.-J. Airborne basidiospores of Coprinus and Ganoderma in a Caribbean region. Aerobiologia 2014, 30, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Strzelczak, A. Changes in concentration of Alternaria and Cladosporium spores during summer storms. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2013, 57, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keishams, F.; Goudarzi, G.; Hajizadeh, Y.; Hashemzadeh, M.; Teiri, H. Influence of meteorological parameters and PM2.5 on the level of culturable airborne bacteria and fungi in Abadan, Iran. Aerobiologia 2022, 38, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk, I.; Kaszewski, B.M.; Weryszko-Chmielewska, E.; Nowak, M.; Sulborska, A.; Kaczmarek, J.; Szymanska, A.; Haratym, W.; Jedryczka, M. Warm and dry weather accelerates and elongates Cladosporium spore seasons in Poland. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadyś, M.; Kennedy, R.; West, J.S. Potential impact of climate change on fungal distributions: Analysis of 2 years of contrasting weather in the UK. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peternel, R.; Čulig, J.; Hrga, I. Atmospheric concentrations of Cladosporium spp. and Alternaria spp. spores in Zagreb (Croatia) and effects of some meteorological factors. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2004, 11, 303–307. [Google Scholar]

- Stępalska, D.; Wołek, J. Intradiurnal periodicity of fungal spore concentrations Alternaria, Botrytis, Cladosporium, Didymella, Ganoderma) in Cracow, Poland. Aerobiologia 2009, 25, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J.; Iglesias, I.; Jato, V. Variation assessment of airborne Alternaria and Cladosporium spores at different bioclimatical conditions. Mycol. Res. 2005, 109, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Rapiejko, P. Occurrence of Cladosporium spp. and Alternaria spp. spores in Western, Northern and Central-Eastern Poland in 2004-2006 and relations to some meteorological factors. Atmos. Res. 2009, 93, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro, H.; Delgado, J.L.; Abreu, I. Seasonal and intradiurnal variation of allergenic fungal spores in urban and rural areas of the North of Portugal. Aerobiologia 2009, 25, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio, M.; Trigo, M.M.; Docampo, S.; Melgar, M.; García-Sánchez, J.; Bootello, L.; Cabezudo, B. Analysis of the predicting variables for daily and weekly fluctuations of two airborne fungal spores: Alternaria and Cladosporium. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Strzelczak, A.; Stępalska, D.; Myszkowska, D. A 10-year study of Alternaria and Cladosporium in two Polish cities (Szczecin and Cracow) and relationship with the meteorological parameters. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianovici, N. Atmospheric concentrations of selected allergenic fungal spores in relation to some meteorological factors, in Timişoara (Romania). Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjøth, С.A.; Damialis, A.; Belmonte, J.; de Linares, C.; Fernández-Rodríguez, S.; Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Jędryczka, M.; Kasprzyk, I.; Magyar, D.; Myszkowska, D.; et al. Alternaria spores in the air across Europe: Abundance, seasonality and relationships with climate, meteorology and local environment. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadyś, M.; Skjøth, C.A.; Kennedy, R. Forecasting methodologies for Ganoderma spore concentration using combined statistical approaches and model evaluations. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2016, 60, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Strzelczak, A. Artificial neural network models of relationships between Alternaria spores and meteorological factors in Szczecin (Poland). Int. J. Biometeorol. 2008, 52, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glagolev, M.V.; Sabrekov, A.F.; Faustova, E.V.; Marfenina, O.E. Modelling of concentration dynamics of fungal aerosols in the atmospheric boundary layer: I. Basic processes and equations. Environ. dynamics global climate change 2016, 7, 85–102, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrego, N.; Furneaux, B.; Hardwick, B.; Somervuo, P.; Palorinne, I.; Aguilar-Trigueros, C.A.; Andrew, N.R.; Babiy, U.V.; Bao, T.; Bazzano, G.; et al. Airborne DNA reveals predictable spatial and seasonal dynamics of fungi. Nature 2024, 631, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk, I.; Rodinkova, V.; Šaulienė, I.; Ritenberga, O.; Grinn-Gofron, A.; Nowak, M.; Sulborska, A.; Kaczmarek, J.; Weryszko-Chmielewska, E.; Bilous, E.; Jedryczka, M. Air pollution by allergenic spores of the genus Alternaria in the air of central and eastern Europe. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 9260–9274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Strzelczak, A. Hourly predictive artificial neural network and multivariate regression tree models of Alternaria and Cladosporium spore concentrations in Szczecin (Poland). Int. J. Biometeorol. 2009, 53, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katial, R.K.; Zhang, Y.; Jones, R.H.; Dyer, P.D. Atmospheric mold spore counts in relation to meteorological parameters. Int. J. Biometeorol. 1997, 41, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantoani, M.C.; Ribeiro Sapucci, C.; Guerra, L.C.C.; Andrade, M.F.; Dias, M.A.F.S.; Dias, P.L.S.; Ifanger Albrecht, R.; Pereira Silva, E.; Rodrigues, F.; Araujo, G.G.; et al. Airborne fungal spore concentrations double but diversity decreases with warmer winter temperatures in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest biodiversity hotspot. The Microbe 2025, 7, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanin, S.S. Epiphytotiology of cereal rusts: Modeling, monitoring, control. D. Sci. Thesis, All-Russian Research Institute of Plant Protection, St. Petersburg, November 1998. (In Russ.).

- Bogdanova, V.V.; Goloshchapov, A.P.; Evseev, V.V. Monitoring the mass of phytopathogenic fungi spores. Agrarian Bulletin of the Urals 2010, 2, 52–54, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Shamanin, V.P.; Morgunov, A.I.; Chursin, A.S.; Merkeshina, N.N.; Shtubey, T.Y.; Levshunov, M.A.; Karakoz, I.I. Is stem rust a threat to wheat crops in Western Siberia? Adv. Curr. Nat. Sci. 2011, 2, 56–60. Available online: https://natural-sciences.ru/ru/article/view?id=15926 (accessed on 29 September 2025). (In Russ.).

- Andreeva, I.S.; Borodulin, A.I.; Buryak, G.A.; Zhukov, V.A.; Zykov, S.V.; Marchenko, Y.V.; Marchenko, V.V.; Olkin, S.E.; Petrishchenko, V.A.; Pyankov, O.V.; et al. Biogenic Component of Atmospheric Aerosol in the South of West Siberia. Chem. Sustain. Develop. 2002, 10, 523–537. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, B.G. Phytopathological and immunological bases for reducing damage from brown rust of wheat in Western Siberia. D. Sci. Thesis, Ukranian Research Institute of Plant Protection, Kiev, 1984. (In Russ.).

- Koishybaev, M. Features of the spread of especially dangerous wheat diseases in Kazakhstan, resistance of varieties and intraspecific diversity of pathogens. Immunogenetic Protect. Agric. Crops Dis.: Theory Practice 2012, 118–126. (In Russ.).

- Koishybaev, M. Risk of spread of brown, stem and yellow rust on cereal crops. In: Atlas of Natural and Man-Made Hazards and Risks of Emergencies in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2010, 206–208. (In Russ.).

- Marfenina, O.E.; Ivanova, A.E.; Kul’ko, A.B. Features of the spread of opportunistic fungi in the external environment. In Proceedings Modern mycology in Russia. Moscow, Russia, 2002, p. 68. (In Russ.).

- Marfenina, O.E.; Kolosova, E.D.; Glagolev, M.B. Number of fungal diaspores deposited from surface air layers at the areas with different vegetation cover in Moscow city. Mycology Phytopathology 2016, 50, 379–385, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Teplyakova, T.V.; Vorobyeva, I.G.; Vechkanov, V.A.; Andreeva, I.S.; Safatov, A.S.; Buryak, G.A.; Simonenkov, D.V.; Belan, B.D. Complexes of microscopic fungi in atmospheric aerosols of Southwestern Siberia at the altitudes of 500-7000 m in 2014. In Proceedings European Aerosol Conference 2015, Milano, Italy, September 6-11, 2015, P. 2AAS_P063.

- Belan, B.D.; Ancellet, G.; Andreeva, I.S.; Antokhin, P.N.; Arshinova, V.G.; Arshinov, M.Y.; Balin, Y.S.; Barsuk, V.E.; Belan, S.B.; Chernov, D.G.; et al. Integrated airborne investigation of the air composition over the Russian Sector of the Arctic. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 3941–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, I.S.; Solovyanova, N.A.; Vechkanov, V.A.; Morozova, V.V.; Tikunova, N.V. Psychrotolerant yeasts in atmospheric aerosols of Western Siberia. Inter-Medical 2015, 7, 105–111, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, L.; Camacho, I.C.; Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Camacho, R. Monitoring of anamorphic fungal spores in Madeira region (Portugal), 2003–2008. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, Y.; Gosewinkel, U.B.; Skjøth, C.A.; Hertel, O.; Rasmussen, K.; Sigsgaard, T. Regional variation in airborne Alternaria spore concentrations in Denmark through 2012–2015 seasons: The influence of meteorology and grain harvesting Aerobiologia 2019, 35, 533–551. [CrossRef]

- Balandina, S.Y.; Semerikov, V.V.; Shvarts, K.G. The implementation of microbiological monitoring of the concentration of mold spores in the atmospheric air. Medicus 2015, 4, 43–46, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Balandina, S.Y.; Semerikov, V.V.; Shvarts, K.G. A study of seasonal dynamics of micromycetes content in outdoor air near a medical institution. Bull. Udmurt Univer. Ser. Biol. Earth Sci. 2015, 25, 7–10, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Bracero, M.; Markey, E.; Clancy, J.H.; McGillicuddy, E.J.; Sewel, G.; O’Connor, D.J. Airborne Fungal Spore Review, New Advances and Automatisation. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk, I.; Rzepowska, B.; Wasylów, M. Fungal spores in the atmosphere of Rzeszów (South-East Poland). Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2004, 11, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, A.M.; Kirtsideli, I.Y. Microfungi complexes in the air of Saint-Petersburg. Mycology Phytopathology 2007, 41, 40–47, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko, M.I.; Zaika, Y.I. Comparative estimation of the specific variety of microscopic fungi in the atmosphere of different functional zones of the city of Belgorod. Belgorod State Univer. Sci. Bull. Nat. Sci. 2011, 14, 42–48, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Grinn-Gofroń, A. Airborne Aspergillus and Penicillium in the atmosphere of Szczecin, (Poland) (2004–2009). Aerobiologia 2010, 27, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safatov, A.S.; Andreeva, I.S.; Buryak, G.A.; Olkin, S.E.; Reznikova, I.K.; Belan, B.D.; Panchenko, M.V.; Simonenkov, D.V. Long-Term Studies of Biological Components of Atmospheric Aerosol: Trends and Variability. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).