Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Fungal spores’ calendars for Mexico are inexistent. This research represents the first fungal spores’ concentration data in the atmosphere of Hermosillo, Mexico, a city in the Sonoran Desert with high rates of allergies and public health problem. We used standardized sampling techniques frequently used by aerobiologists, including a Burkard spore trap to monitor airborne fungal spores daily for 2016-2019 and 2022-2023. Results are expressed as daily fungal spores’ concentration in air (spores/m3 air). The most common fungal outdoor spores corresponded to Cladosporium (44%), Ascospora (17%), Smut (14%), Alternaria (12%) and Diatrypaceae (7%) of the total 6 years data. High minimum temperatures produce an increasing of most important spores in air (Cladosporium and Alternaria), whereas precipitation increase Ascospores concentrations. The most important peak of Fungal spores’ concentration in air is recorded during summer-fall in all cases. Airborne fungal spores at Hermosillo had a greater impact on human health. This data will be of great help for prevention diagnostic and treatment of seasonally allergies in population and for agricultural sector that have problems with some pathogens of their crops caused by fungus.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Region

2.2. Sampling Airborne Fungal Spores

2.3. Fungal Spore Calendar Construction

2.3. Climatic Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Airborne Fungal Spores’ Diversity

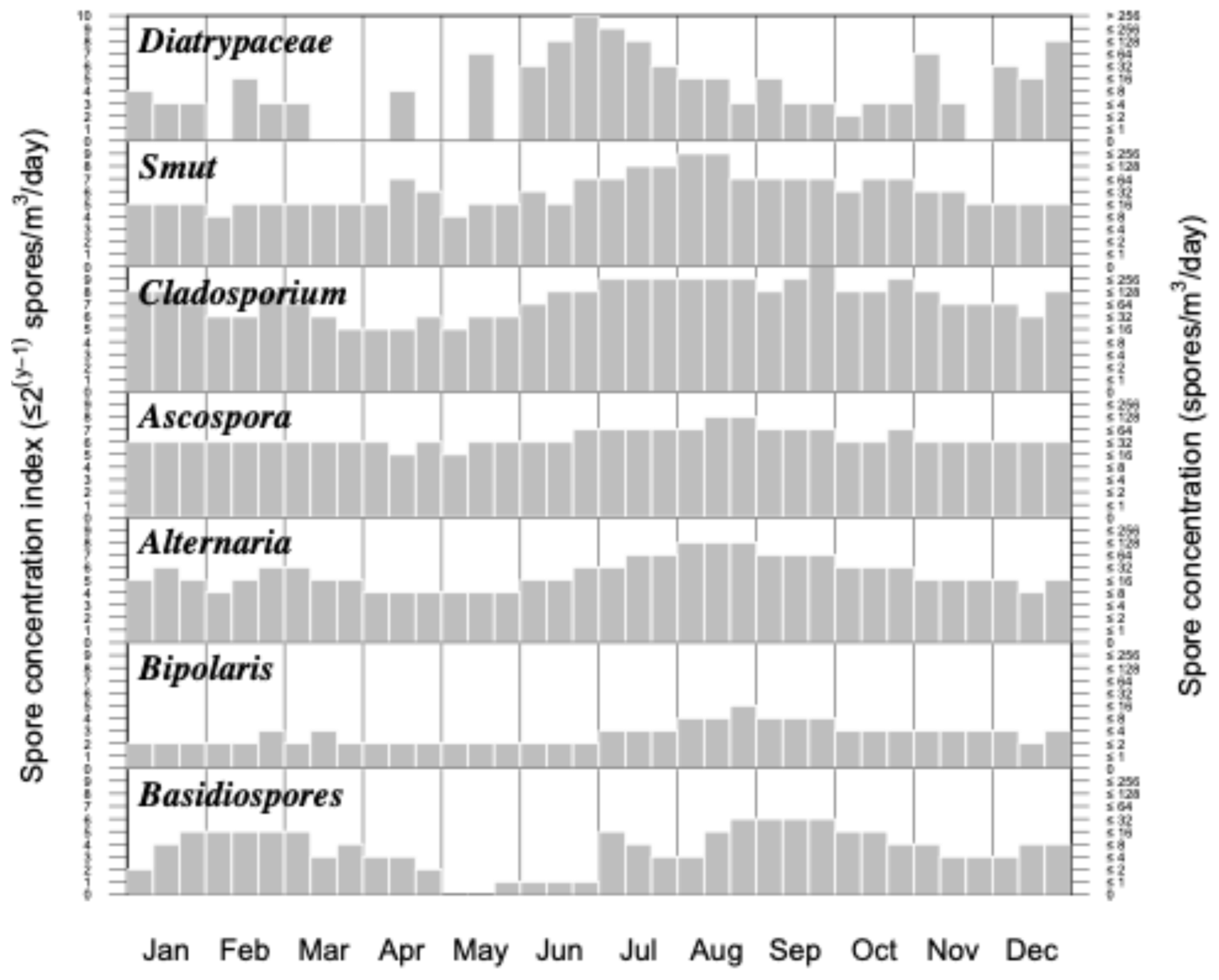

3.2. Fungal Spore Calendar

Diatrypaceae

Smut

Cladosporium sp.

Ascospora

Alternaria sp.

Bipolaris sp.

Basidiospores

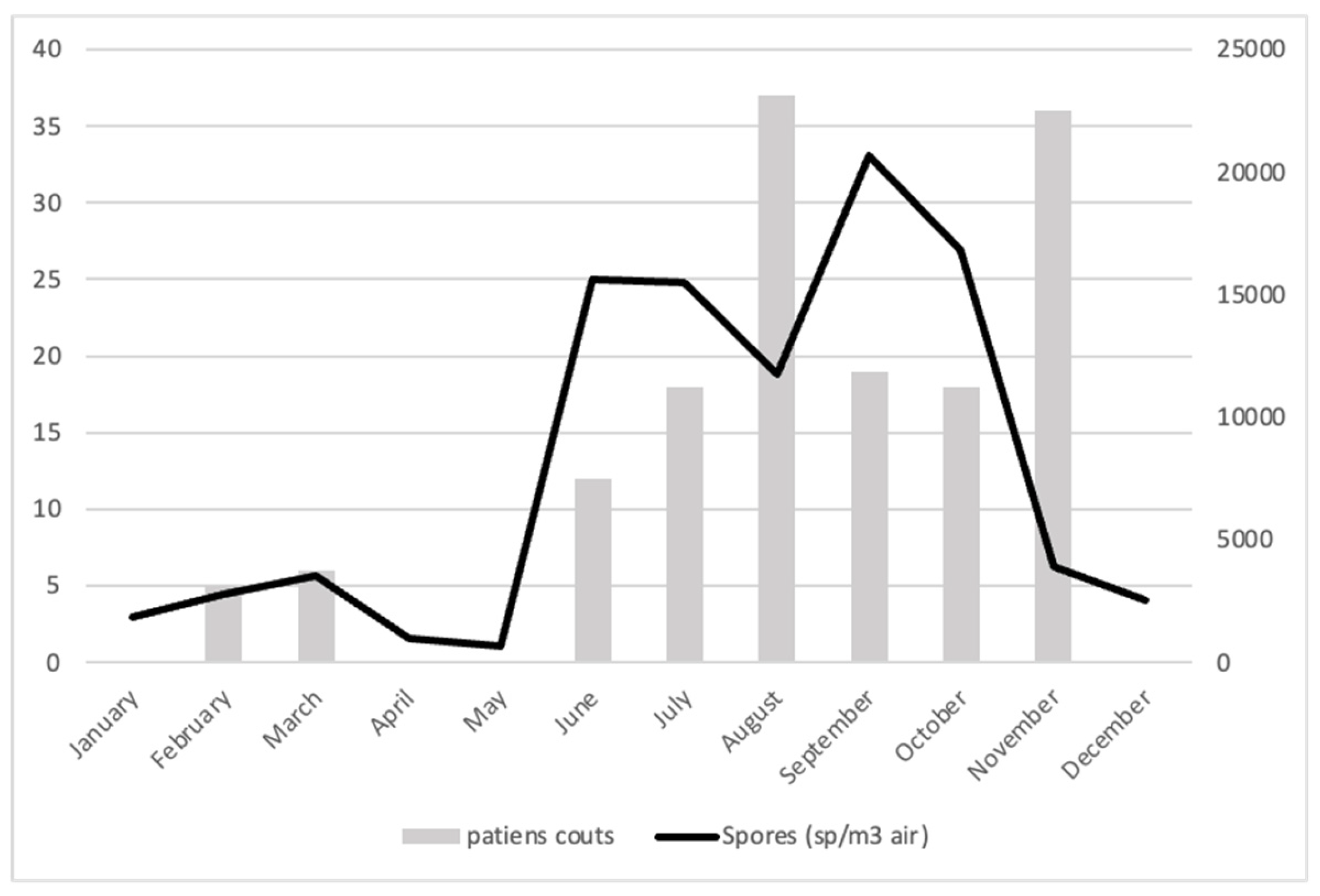

3.2. Climate and Spores’ Concentration in Air

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ortega Rosas, C.I.; Calderón-Ezquerro, M.D.C.; Gutiérrez-Ruacho, O.G. Fungal spores and pollen are correlated with meteorological variables: effects in human health at Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico. International journal of environmental health research 2020, 30, 677-695. [CrossRef]

- Sofiev, M.; Bergmann, K.-C. Allergenic pollen: a review of the production, release, distribution and health impacts. 2012.

- Ortega-Rosas, C.; Meza-Figueroa, D.; Vidal-Solano, J.; González-Grijalva, B.; Schiavo, B. Association of airborne particulate matter with pollen, fungal spores, and allergic symptoms in an arid urbanized area. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2021, 43, 1761-1782. [CrossRef]

- Gioulekas, D.; Damialis, A.; Papakosta, D.; Spieksma, F.; Giouleka, P.; Patakas, D. Allergenic fungi spore records (15 years) and sensitization in patients with respiratory allergy in Thessaloniki-Greece. Journal of Investigational Allergology and Clinical Immunology 2004, 14, 225-231.

- Fukutomi, Y.; Taniguchi, M. Sensitization to fungal allergens: resolved and unresolved issues. Allergology International 2015, 64, 321-331. [CrossRef]

- Sztandera-Tymoczek, M.; Szuster-Ciesielska, A. Fungal Aeroallergens—The Impact of Climate Change. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 544. [CrossRef]

- Ščevková, J.; Kováč, J. First fungal spore calendar for the atmosphere of Bratislava, Slovakia. Aerobiologia 2019, 35, 343-356. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Soto, R.; Navarrete-Rodríguez, E.; Del-Rio-Navarro, B.E.; Sienra-Monge, J.L.; Meneses-Sánchez, N.; Saucedo-Ramírez, O. Fungal Allergy: Pattern of sensitization over the past 11 years. Allergologia et immunopathologia 2018, 46, 557-564. [CrossRef]

- Zureik, M.; Neukirch, C.; Leynaert, B.; Liard, R.; Bousquet, J.; Neukirch, F. Sensitisation to airborne moulds and severity of asthma: cross sectional study from European Community respiratory health survey. Bmj 2002, 325, 411. [CrossRef]

- Twaroch, T.E.; Curin, M.; Valenta, R.; Swoboda, I. Mold allergens in respiratory allergy: from structure to therapy. Allergy, asthma & immunology research 2015, 7, 205-220. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Asthma Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/asthma/?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAjwmaO4BhAhEiwA5p4YLyseQOE2Dfp9Fn_p5eo9iU-ZLTIRzB8LUqQDTiWQotcqfOVY9JsM7xoCtgIQAvD_BwE (accessed on 6 may 2024).

- Moreno-Sarmiento, M.; Peñalba, M.C.; Belmonte, J.; Rosas-Pérez, I.; Lizarraga-Celaya, C.; Ortega-Nieblas, M.M.; Villa-Ibarra, M.; Lares-Villa, F.; Pizano-Nazara, L.J. Airborne fungal spores from an urban locality in southern Sonora, Mexico. Revista mexicana de micología 2016, 44, 11-20.

- Sánchez-Reyes, E.; Rodríguez de la Cruz, D.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J. First fungal spore calendar of the middle-west of the Iberian Peninsula. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 529-539. [CrossRef]

- Bednarz, A.; Pawlowska, S. A fungal spore calendar for the atmosphere of Szczecin, Poland. Acta agrobotanica 2016, 69. [CrossRef]

- Molina Freaner, F.E., Van Devender, T. R. . DIVERSIDAD BIOLÓGICA DE SONORA.

- INEGI. Conociendo Sonora. 2013.

- Galán Soldevilla, C.; Cariñanos González, P.; Alcázar Teno, P.; Domínguez Vilches, E. Spanish Aerobiology Network (REA): management and quality manual. Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad de Córdoba 2007, 184, 1-300.

- Galán, C.; Ariatti, A.; Bonini, M.; Clot, B.; Crouzy, B.; Dahl, A.; Fernandez-González, D.; Frenguelli, G.; Gehrig, R.; Isard, S. Recommended terminology for aerobiological studies. Aerobiologia 2017, 33, 293-295. [CrossRef]

- Spieksama, F.T.M. Regional European pollen calendars.[In:] G. D’Amato, F. Th. M. Spieksma, S. Bonini (eds). Allergenic pollen and pollinosis in Europe. 1991.

- Fahrmeir, L.; Kneib, T.; Lang, S.; Marx, B.; Fahrmeir, L.; Kneib, T.; Lang, S.; Marx, B. Regression models; Springer: 2013.

- Team, R.C. A language and environment for statistical computing, 2021.

- Patel, T.Y.; Buttner, M.; Rivas, D.; Cross, C.; Bazylinski, D.A.; Seggev, J. Variation in airborne fungal spore concentrations among five monitoring locations in a desert urban environment. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2018, 190, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Sen, M.M.; Gupta-Bhattacharya, S.; Chanda, S. Airborne viable, non-viable, and allergenic fungi in a rural agricultural area of India: a 2-year study at five outdoor sampling stations. Science of the Total Environment 2004, 326, 123-141. [CrossRef]

- ROCHA ESTRADA, A.; ALVARADO VÁZQUEZ, M.A.; GUTIÉRREZ REYES, R.; SALCEDO MARTÍNEZ, S.M.; MORENO LIMÓN, S. Variación temporal de esporas de Alternaria, Cladosporium, Coprinus, Curvularia y Venturia en el aire del área metropolitana de Monterrey, Nuevo León, México. Revista internacional de contaminación ambiental 2013, 29, 155-165.

- Solomon, G.M.; Hjelmroos-Koski, M.; Rotkin-Ellman, M.; Hammond, S.K. Airborne mold and endotoxin concentrations in New Orleans, Louisiana, after flooding, October through November 2005. Environmental Health Perspectives 2006, 114, 1381-1386. [CrossRef]

- Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Strzelczak, A. Hourly predictive artificial neural network and multivariate regression tree models of Alternaria and Cladosporium spore concentrations in Szczecin (Poland). International Journal of Biometeorology 2009, 53, 555-562. [CrossRef]

- NOAA. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Available online: https://www.noaa.gov/ (accessed on May 2024).

| Taxa | Total spores | Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cladosporium | 298,357 | 43.70 |

| Ascospora | 115,629 | 16.93 |

| Smut | 95,903 | 14.05 |

| Alternaria | 80,451 | 11.78 |

| Diatrypaceae | 49,279 | 7.22 |

| Basidiospores | 12,093 | 1.77 |

| Bipolaris | 8,820 | 1.29 |

| Myxomicetes | 5,639 | 0.83 |

| Pithomyces | 5,046 | 0.74 |

| Agaricus | 4,954 | 0.73 |

| Arthrinium | 2,562 | 0.38 |

| Curvularia | 1,856 | 0.27 |

| Torula | 862 | 0.13 |

| Periconia | 500 | 0.07 |

| Sporidesmium | 310 | 0.05 |

| Boerlagella | 291 | 0.04 |

| Spegazzinia | 117 | 0.02 |

| Leptosphaeria | 116 | 0.02 |

| Peronospora | 6 | 0.00 |

| Beltrania | 1 | 0.00 |

| Fuligo | 1 | 0.00 |

| ASIn | 682,793 1 | 100% |

| Taxa | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2023 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cladosporium | 73,205 | 44,876 | 55,439 | 36,455 | 80,510 1 | 58,097 |

| Ascospora | 15,837 | 13,265 | 7,520 | 5,633 | 6,8241 | 22,099 |

| Smut | 50,601 | 24,662 | 10,661 | 9,161 | 0 | 19,017 |

| Alternaria | 20,252 | 18,279 | 12,905 | 9,716 | 17,487 | 15,728 |

| Diatrypaceae | 22,021 | 11,990 | 5,183 | 2,758 | 7,296 | 9,850 |

| Basidiospores | 96 | 2,410 | 1,583 | 1,439 | 6,121 | 2,330 |

| Bipolaris | 1,249 | 856 | 1,367 | 1,304 | 3,663 | 1,688 |

| Myxomicetes | 2,481 | 1,420 | 854 | 764 | 0 | 1,104 |

| Pithomyces | 322 | 115 | 104 | 73 | 4,431 | 1,009 |

| Agaricus | 3,817 | 1,133 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 990 |

| Arthrinium | 855 | 845 | 409 | 414 | 0 | 505 |

| Curvularia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,851 | 370 |

| Torula | 356 | 224 | 169 | 101 | 0 | 170 |

| Periconia | 8 | 102 | 186 | 186 | 0 | 96 |

| Sporidesmium | 93 | 86 | 69 | 56 | 0 | 61 |

| Boerlagella | 116 | 79 | 48 | 45 | 0 | 58 |

| Spegazzinia | 21 | 47 | 27 | 19 | 0 | 23 |

| Leptosphaeria | 116 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| Peronospora | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 |

| Beltrania | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fuligo | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ASIn | 191,448 | 120,390 | 96,524 | 68,130 | 189,600 | 133,218 |

| Parameter (lag in days) |

Cladosporium | Ascospora | Smut | Alternaria |

| Min. Temp. (0) | + + + | + | + + + | + + + |

| Min. Temp. (1) | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Min. Temp. (2) | + + | + + + | + + | + + |

| Max. Temp. (0) | − − − | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Max. Temp. (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Max. Temp. (2) | – – | − − − | − − − | − − − |

| Precipitation (0) | 0 | + + + | 0 | 0 |

| Precipitation (1) | 0 | + + + | 0 | 0 |

| Precipitation (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).