Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

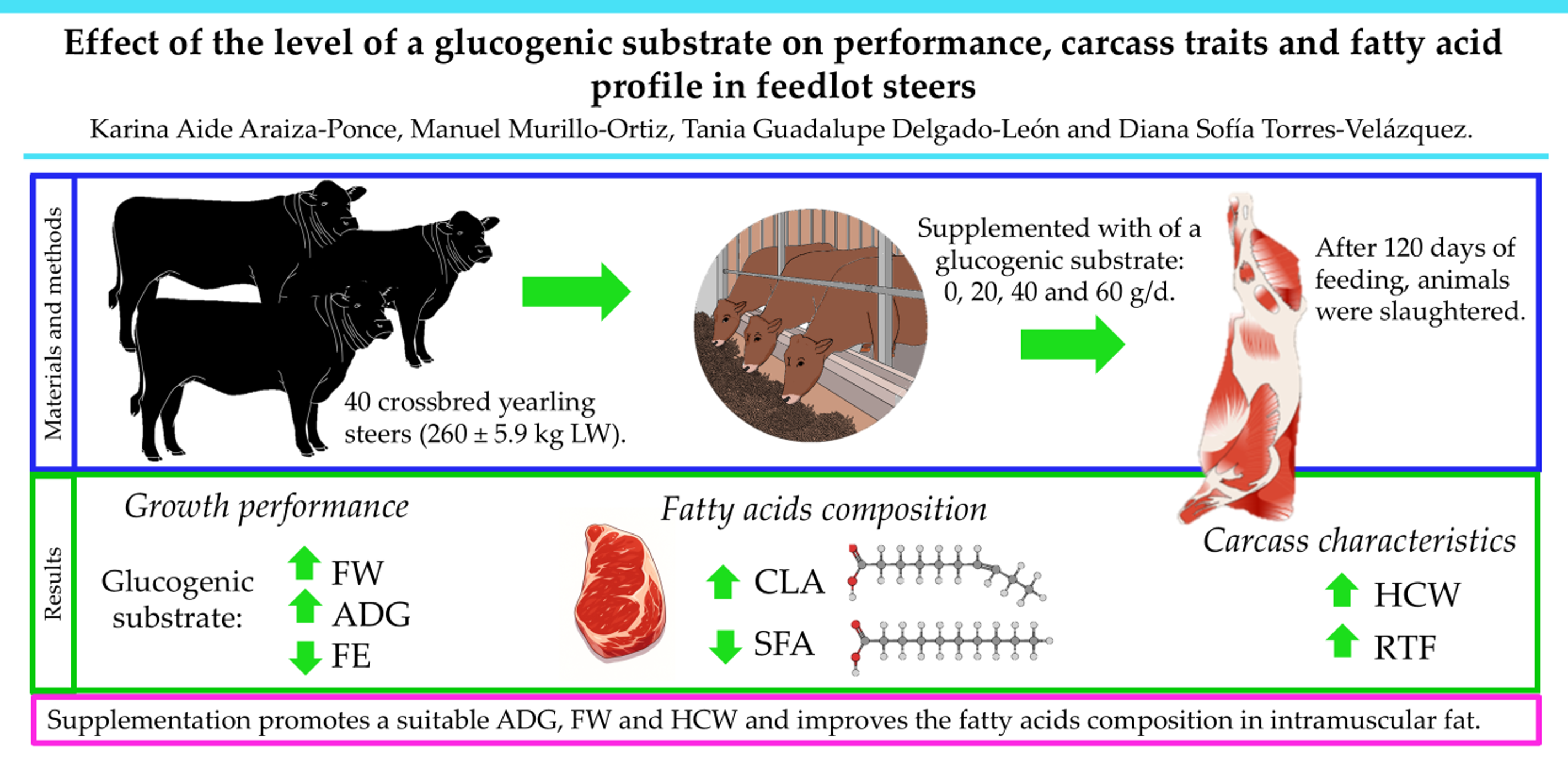

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Treatments

2.2. Growth Performance

2.3. Slaughter and Carcass Data

2.4. Fatty Acid Composition

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance and Carcass Characteristics

3.2. Fatty Acids Composition

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth Performance and Carcass Characteristics

4.2. Fatty Acids Composition

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cuchillo-Hilario, M.; Fournier-Ramírez, M.-I.; Díaz Martínez, M.; Montaño Benavides, S.; Calvo-Carrillo, M.-C.; Carrillo Domínguez, S.; Carranco-Jáuregui, M.-E.; Hernández-Rodríguez, E.; Mora-Pérez, P.; Cruz-Martínez, Y.R.; et al. Animal Food Products to Support Human Nutrition and to Boost Human Health: The Potential of Feedstuffs Resources and Their Metabolites as Health-Promoters. Metabolites 2024, 14, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.D.; Giromini, C; Givens, D.I. Animal-derived foods: consumption, composition and effects on health and the environment: an overview. Frontiers in Animal Science 2024. 5:1332694. [CrossRef]

- Perna, M.; Hewlings, S. Saturated Fatty Acid Chain Length and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper L, Martin N, Jimoh OF, Kirk C, Foster E, Abdelhamid AS. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD011737. [CrossRef]

- Scollan, N.D.; Dannenberger, D.; Nuernber, K.; Richardson, I.; MacKintosh, S.; Hocquette, J.F.; Moloney, A.P. Enhancing the nutritional and health value of beef lipids and their relationship with meat quality. Meat Science. 2014; 97:3:384-394. [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Duttaroy, A.K. Conjugated linoleic acid and its beneficial effects in obesity, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Nutrients 2020, 12(7), 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhamid, A.S.; Martin, N.; Bridges, C.; Brainard, J.S.; Wang, X.; Brown, T.J.; Hanson, S.; Jimoh, O.F.; Ajabnoor, S.M.; Deane, K.H.; et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018, 7, CD012345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krusinski, L., Sergin, S., Jambunathan, V.; Rowntree, J.E.; Fenton, J.I. Attention to the Details: How Variations in U.S. Grass-Fed Cattle-Feed Supplementation and Finishing Date Influence Human Health. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2022. 6:851494. [CrossRef]

- Nogoy, K.M.C.; Sun, B.; Shin, S.; Lee, Y.; Li, X.Z.; Choi, S.H; Park, S. Fatty acid composition of grain-and grass-fed beef and their nutritional value and health implication. Food science of animal resources 2022, 42 (1), 18. [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.; Magistrali, A.; Butler, G.; Stergiadis, S. Nutritional Benefits from Fatty Acids in Organic and Grass-Fed Beef. Foods 2022, 11, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponnampalam, E. N.; Jairath, G.; Alves, S. P.; Gadzama, I. U.; Santhiravel, S.; Mapiye, C.; Holman, B. W. Sustainable livestock production by utilising forages, supplements, and agricultural by-products: Enhancing productivity, muscle gain, and meat quality–A review. Meat Science 2025, 109921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, L.D.; Vasconcelos, A.B.; Lobo Júnior, A.R.; Rosado, G.L.; Bento, C.B. Effects of different additives on cattle feed intake and performance-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 2024, 96, e20230172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naves, K.R.S.; Moraes, K.A.K.; Cunha, L.O.d.; Petrenko, N.B.; Ortelam, J.C.; Sousa, J.N.; Covatti, C.F.; Nunes, D.; Chaves, C.S.; Menezes, F.L.d.; et al. Additives in Supplements for Grazing Beef Cattle. Animals 2024, 14, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondratovich Lucas B.; Jhones O. Sarturi; Carly A. Hoffmann; Michael A. Ballou; Sara J. Trojan; Pedro RB Campanili. Effects of dietary exogenous fibrolytic enzymes on ruminal fermentation characteristics of beef steers fed high-and low-quality growing diets. Journal of animal science 2019. 97, 7: 3089-3102. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle: Eighth Revised Edition. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2021. Chapter 16, Feed Additives. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Rathert-Williams, A. R.; Salisbury, C. M.; Lindholm-Perry, A. K.; Pezeshki, A.; Lalman, D. L.; Foote, A. P. Effects of increasing calcium propionate in a finishing diet on dry matter intake and glucose metabolism in steers. Journal of Animal Science 2021, 99(12), skab314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, T.M.; Beard, J.K.; Norman, M.M.; Wilson, H.C.; MacDonald, J.M.; Mulliniks, J.T. Effect of protein and glucogenic precursor supplementation on forage digestibility, serum metabolites, energy utilization, and rumen parameters in sheep. Translational Animal Science 2021. Dec 14;6(1):t xab229. [CrossRef]

- Arita-Portillo, C. R.; Elizondo-Salazar, J. A. Efecto del uso de una mezcla de compuestos gluconeogénicos en vacas lecheras en transición. Agronomía Costarricense 2023, 47(2), 111-120. [CrossRef]

- Mikuła, R.; Pruszyńska-Oszmałek, E.; Kołodziejski, P.A.; Nowak, W. Propylene Glycol and Maize Grain Supplementation Improve Fertility Parameters in Dairy Cows. Animals 2020. Nov 18;10(11):2147. [CrossRef]

- NOM-062-ZOO-1999; Especificaciones Técnicas para la Producción, Cuidado y Uso de los Animales de Laboratorio. Norma Oficial Mexicana; Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, Mexico, 2001; pp. 128–134.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle: Eighth Revised Edition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- NOM-033-SAG/ZOO-2014; Métodos para dar muerte a los animales domésticos y silvestres. Norma Oficial Mexicana; Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; pp. 1-48.

- San Vito, E.; Lage, J. F.; Ribeiro, A. F.; Silva, R. A.; Berchielli, T. T. Fatty acid profile, carcass and quality traits of meat from Nellore young bulls on pasture supplemented with crude glycerin. Meat science 2015, 100, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, I.M.; Oliveira, K.A.; Cidrini, I.A.; de Abreu, M.J.; Sousa, L.M.; Batista, L.H.; Homem, B.G.; Prados, L.F.; Siqueira, G.R.; Resende, F.D. Performance, intake, feed efficiency, and carcass characteristics of young Nellore heifers under different days on feed in the feedlot. Animals 2023. Jul 7;13(13):2238. [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E. G., & Dyer, W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Canadian journal of biochemistry and physiology 1959, 37(8), 911-917. [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 21st ed.; AOAC: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K., Shui, Y.; Deng, M.; Guo, Y.; Sun, B.; Liu, G.; Liu, D., Li, Y. Effects of different dietary energy levels on growth performance, meat quality and nutritional composition, rumen fermentation parameters, and rumen microbiota of fattening Angus steers. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024. May 6; 15:1378073. [CrossRef]

- Honig, A.C.; Inhuber, V.; Spiekers, H.; Windisch, W., Götz, K.U.; Schuster, M.; Ettle, T. Body composition and composition of gain of growing beef bulls fed rations with varying energy concentrations. Meat science 2022 Feb 1; 184:108685. [CrossRef]

- Simioni, T.A.; Torrecilhas, J.A.; Messana, J.D., Granja-Salcedo, Y.T.; San Vito, E.; Lima, A.R.; Sanchez, J.M.; Reis, R.A.; Berchielli, T.T. Influence of growing-phase supplementation strategies on intake and performance of different beef cattle genotypes in finishing phase on pasture or feedlot. Livestock Science. 2021 Sep 1; 251:104653. [CrossRef]

- Lahart, B.; Prendiville, R.; Buckley, F.; Kennedy, E.; Conroy, S.B.; Boland, T.M.; McGee, M. The repeatability of feed intake and feed efficiency in beef cattle offered high-concentrate, grass silage and pasture-based diets. Animal. 2020 Nov;14(11):2288-97. [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.S.; Villela, S.D.; de Paula Leonel, F., Verardo, L.L.; Regina Paschoaloto, J.; Paulino, P.V.; de Almeida Matos, É.M.; de Almeida Martins, P.G.; Dallago, G.M.; Costa, P.M. Performance and economic analysis of Nellore cattle finished in feedlot during dry and rainy seasons. Livestock Science. 2022 Jun 1;260:104903. [CrossRef]

- San Vito, E.; Granja-Salcedo, Y.T.; Lage, J.F.; Oliveira, A.S.; Gionbelli, M.P.; Messana, J.D.; Dallantonia, E.E.; Reis, R.A.; Berchielli, T.T. Crude glycerin as an alternative to corn as a supplement for beef cattle grazing in pasture during the dry season. Semina: Ciências Agrárias. 2018 Aug 20;39(5):2215-32. [CrossRef]

- Nusri-Un, J.; Kabsuk, J.; Binsulong, B.; Sommart, K. Effects of cattle breeds and dietary energy density on intake, growth, carcass, and meat quality under Thai feedlot management system. Animals. 2024 Apr 15;14(8):1186. [CrossRef]

- Fruet, A.P., Stefanello, F.S.; Trombetta, F.; De Souza, A.N.; Júnior, A.R., Tonetto, C.J., Flores, J.L.; Scheibler, R.B.; Bianchi, R.M.; Pacheco, P.S.; De Mello, A. Growth performance and carcass traits of steers finished on three different systems including legume–grass pasture and grain diets. Animal. 2019 Jul;13(7):1552-62. [CrossRef]

- Ladeira, M.M.; Carvalho, J.R.; Chizzotti, M.L.; Teixeira, P.D.; Dias, J.C.; Gionbelli, T.R.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Oliveira; D.M. Effect of increasing levels of glycerin on growth rate, carcass traits and liver gluconeogenesis in young bulls. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 2016 Sep 1;219:241-8. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Niehues, M.B.; Tomaz, L.A.; Baldassini, W.; Ladeira, M.; Arrigoni, M.; Martins, C.L.; Gionbelli, T.; Paulino, P.; Neto, O.R. Dry matter intake, performance, carcass traits and expression of genes of muscle protein metabolism in cattle fed increasing levels of de-oiled wet distillers grains. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 2020 Nov 1;269:114627. [CrossRef]

- Van Cleef, E.H.; Uwituzem, S.; Alvarado-Gilis, C.A.; Miller, K.A., Van Bibber-Krueger, C.L.; Aperce, C.C., Drouillard, J.S. Elevated concentrations of crude glycerin in diets for beef cattle: feedlot performance, carcass traits, and ruminal metabolism. Journal of Animal Science. 2019 Oct 3;97(10):4341-8. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Reed, D.D., Jr.; Young, J.M.; Eshkabilov, S.; Berg, E.P.; Sun, X. Beef Quality Grade Classification Based on Intramuscular Fat Content Using Hyperspectral Imaging Technology. Applied Sciences. 2021, 11, 4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, R.; Loveday, D. Understanding yield grades and quality grades for value-added beef producers and marketers. Institute of Agriculture, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. 2013 Dec 1.

- Castagnino, P.S.; Fiorentini, G.; Dallantonia, E.E.; San Vito, E.; Messana, J.D.; Torrecilhas, J.A.; Sobrinho, A.G.; Berchielli, T.T. Fatty acid profile and carcass traits of feedlot Nellore cattle fed crude glycerin and virginiamycin. Meat science. 2018 Jun 1; 140:51-8. [CrossRef]

- Pilarczyk, R.; Wójcik, J. Fatty acids profile and health lipid indices in the longissimus lumborum muscle of different beef cattle breeds reared under intensive production systems. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Zootechnica. 2015. 14(1), 109–126.

- Maciel, I.C.; Schweihofer, J.P.; Fenton, J.I.; Hodbod, J.; McKendree, M.G.; Cassida, K.; Rowntree, J.E. Influence of beef genotypes on animal performance, carcass traits, meat quality, and sensory characteristics in grazing or feedlot-finished steers. Translational Animal Science. 2021 Oct 1;5(4):txab214. [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Wang, L.; Lambo, M.T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Effect of changing the proportion of C16: 0 and cis-9 C18: 1 in fat supplements on rumen fermentation, glucose and lipid metabolism, antioxidation capacity, and visceral fatty acid profile in finishing Angus bulls. Animal Nutrition. 2024 Sep 1;18:39-48. [CrossRef]

- Ladeira, M.M.;, Schoonmaker, J.P.; Gionbelli, M.P.; Dias, J.C.; Gionbelli, T.R.; Carvalho, J.R.; Teixeira, P.D. Nutrigenomics and beef quality: a review about lipogenesis. International journal of molecular sciences. 2016 Jun 10;17(6):918. [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhan, T.; Teng, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ma, L.; Bu, D. Different sources of DHA have distinct effects on the ruminal fatty acid profile and microbiota in vitro. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research. 2025; 21:101875. [CrossRef]

- Toral, P.G.; Monahan, F.J.; Hervás, G.; Frutos, P.; Moloney, A.P. Modulating ruminal lipid metabolism to improve the fatty acid composition of meat and milk. Challenges and opportunities. Animal. 2018. Dec;12(s2):s272-81.

- Badawy, S.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M.; Liu, Z.; Xie, C.; Marawan, M.A.; Ares, I.; Lopez-Torres, B.; Martinez, M.; Maximiliano, J.E.; Martinez-Larranaga, M.R. Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) as a functional food: Is it beneficial or not?. Food Research International. 2023 Oct 1;172:113158. [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.T.; To, K.V.; Schilling, M.W. Fatty acid composition of meat animals as flavor precursors. Meat and Muscle Biology. 2021 Aug 10;5(1). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.V.; Nguyen, O.C.; Malau-Aduli, A.E. Main regulatory factors of marbling level in beef cattle. Veterinary and Animal Science. 2021. Dec 1;14: 100219. [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. An increase in the omega- 6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio increases the risk for obesity. Nutrients. 2016; 8:3:128. [CrossRef]

| Treatments | ||||

| Ingredients | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 |

| Alfalfa hay (%) | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Oat hay (%) | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Cottonseed meal (%) | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Rolled corn (%) | 47.0 | 47.0 | 47.0 | 47.0 |

| Mineral premix* (%) ж Calcium carbonate (%) ж Monensin (g) ж Glucogenic substrate† (g/a/d) | 1.0 ж 2.0 ж 2 ж 0 | 1.0 ж 2.0 ж 2 ж 20 | 1.0 ж 2.0 ж 2 ж 40 | 1.0 ж 2.0 ж 2 ж 60 |

| Chemical composition (g/kg) | ||||

| Organic matter | 940 | 940 | 940 | 940 |

| Crude protein | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 |

| Ether extract | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 490 | 490 | 490 | 490 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 195 | 195 | 195 | 195 |

| Fatty acids (g/100 g total fatty acids) | ||||

| C16:0 | 40.9 | 40.9 | 40.9 | 40.9 |

| C14:0 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 |

| C16:1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| C18:1 (c9) | 49.9 | 49.9 | 49.9 | 49.9 |

| C18:2 (c9, c12) | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| Treatments | |||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | SEM | |

| FW, kg | 422.7±8.23b | 488.3±5.04ab | 461.2±10.03ab | 499.3±13.8a | 36.09 |

| ADG, kg/d | 1.1±0.01c | 1.7±0.07b | 1.9±0.04b | 2.1±0.01a | 0.15 |

| DMI, kg/d | 11.5±1.51a | 10.7±1.53a | 11.4±1.25a | 11.1±1.10a | 0.75 |

| FE | 0.11±0.006a | 0.09±0.004b | 0.11±0.005a | 0.11±0.009a | 0.004 |

| Treatments | |||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | SEM | |

| RTF, mm | 3.7±1.00b | 6.8±1.09a,b | 6.5±1.00a,b | 8.2±1.06a | 3.31 |

| RA, cm2 | 91.4±4.23a | 96.5±4.63a | 94.4±4.23a | 94.2±4.49a | 14.02 |

| DP, % | 57.6±0.89a | 59.4±0.98a | 59.8±0.90a | 59.56±0.95a | 2.98 |

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | SEM | P< | |

| 10:0 | 0.01b | 0.09a | 0.03b | 0.03b | 0.005 | 0.05 |

| 14:0 | 2.01b | 2.47b | 3.66a | 2.08b | 0.449 | 0.05 |

| 16:0 | 29.34a | 24.71b | 29.20a | 28.01a | 0.338 | 0.05 |

| 18:0 | 18.51a | 18.35ab | 17.42ba | 17.01b | 0.228 | 0.05 |

| Cis 9 16:1 | 2.12c | 2.63c | 4.72a | 3.64b | 0.520 | 0.05 |

| Cis 9 18:1 | 37.21a | 37.15a | 37.26a | 37.82a | 0.571 | 0.05 |

| Cis cis 9, 12 18:2 | 2.74b | 3.92a | 4.26a | 3.78a | 0.434 | 0.05 |

| Cis 9 trans 11 18:2 | 0.37c | 0.41c | 0.51b | 0.62a | 0.207 | 0.05 |

| Cis cis cis 9,12,15 18:3 | 0.35c | 0.42c | 0.48b | 0.59a | 0.063 | 0.05 |

| SFA | 49.87a | 45.62c | 50.31a | 47.13b | 0.229 | 0.05 |

| MUFA | 39.33a | 39.78a | 41.98a | 41.46a | 0.430 | 0.05 |

| PUFA | 3.46a | 4.75a | 5.25a | 4.99a | 0.237 | 0.05 |

| Ω6/Ω3 | 7.82b | 9.30a | 8.87a | 6.40b | 0.655 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).