1. Introduction

Hydrogels are three-dimensional networks of hydrophilic polymers capable of absorbing and retaining large amounts of water, making them one of the most versatile classes of biomaterials in biomedical science[

1]. Their high-water content, softness, and biocompatibility allow them to closely mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM) of biological tissues such as skin, cartilage, and mucosa, which has led to their widespread use in wound healing, drug delivery, tissue engineering, and biosensing applications [

2,

3]. Traditionally, bulk hydrogels have dominated the field due to their excellent swelling behavior, permeability, and responsiveness to environmental stimuli such as pH, temperature, and ionic strength [

4]. However, recent advances have shifted attention toward

hydrogel films—thin, flexible layers of hydrogel materials with thicknesses ranging from nanometers to micrometers—which offer unique advantages in biomedical contexts.[

5]

Hydrogel films represent a significant evolution in hydrogel technology [

6]. Their thin-film architecture allows for intimate contact with biological surfaces, enabling applications such as transdermal patches, implant coatings, ophthalmic devices, and bioelectronic interfaces [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Compared to bulk hydrogels, hydrogel films exhibit faster response times, greater surface adaptability, and enhanced integration with biomedical devices. These properties are particularly valuable in dynamic physiological environments where responsiveness and conformability are critical [

12].

The fabrication of hydrogel films has advanced significantly, with techniques such as

solvent casting [13], spin coating [14], layer-by-layer assembly [15],

photopolymerization [16], and

3D printing [17] enabling precise control over film thickness, architecture, and functionality [

18]. These methods allow for the incorporation of

stimuli-responsive elements, bioactive molecules, and

nanomaterials, transforming hydrogel films into smart systems capable of dynamic interaction with biological environments [

19]. For example, thermo-responsive hydrogels like poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm) exhibit phase transitions near body temperature, enabling on-demand drug release and real-time biosensing [

20].

Hydrogel films can be composed of

natural polymers such as chitosan, gelatin, and alginate, which offer excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability [

21,

22,

23], or

synthetic polymers like polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyacrylamide (PAAm), and polyethylene glycol (PEG), which provide tunable mechanical strength and chemical stability [

24,

25,

26]. Hybrid hydrogels that combine natural and synthetic components are increasingly used to balance bioactivity with durability [

27,

28]. Crosslinking mechanisms—whether physical, chemical, or enzymatic—play a crucial role in determining the mechanical and biological properties of hydrogel films. Physically crosslinked hydrogels formed via hydrogen bonding or ionic interactions are reversible and suitable for dynamic applications, while chemically crosslinked hydrogels offer permanent structures ideal for long-term implantation [

29,

30,

31].

In biomedical applications, hydrogel films have demonstrated exceptional promise [

32]. In

wound healing, they maintain a moist environment, absorb exudates, and deliver therapeutic agents, thereby accelerating tissue regeneration [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Self-healing hydrogel films that withstand mechanical stress during dressing changes further improve patient comfort and reduce secondary damage [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

In

drug delivery, hydrogel films serve as platforms for localized and sustained release, reducing systemic toxicity and improving therapeutic efficacy [

42,

43,

44,

45]. Their porous structure allows for high drug loading and controlled release kinetics, which can be tailored through polymer composition and crosslinking density. Stimuli-responsive hydrogel films can release drugs in response to environmental changes, such as pH shifts or temperature variations, enabling precision therapy [

46]. Commercial hydrogel products have already been developed for transdermal, ocular, and injectable drug delivery routes, demonstrating the clinical viability of hydrogel film technologies [

47].

In

tissue engineering, hydrogel films act as scaffolds that support cell growth and differentiation [

48,

49,

50]. Their ability to mimic the mechanical and biochemical properties of native tissues makes them suitable for regenerating skin, cartilage, and bone [

51,

52,

53]. Composite hydrogel films incorporating bioactive molecules like hydroxyapatite or collagen have shown improved osteogenic and angiogenic potential [

54]. Advanced fabrication techniques, such as 3D bioprinting, enable the creation of hydrogel films with complex architectures and spatial control over cell distribution, paving the way for personalized tissue constructs [

55].

Despite their promising applications, hydrogel films face several challenges. Mechanical fragility, limited scalability, and variable degradation rates can hinder clinical translation [

56,

57,

58]. Ensuring long-term biocompatibility and avoiding immune responses remain critical concerns. To address these issues, researchers are exploring

nanocomposite hydrogels, bioinspired designs, and

hybrid crosslinking strategies that enhance mechanical strength and biological performance [

59]. The integration of hydrogel films with electronic components for biosensing and soft robotics is another emerging frontier. These systems can monitor physiological signals, deliver drugs, and respond to stimuli in real time, offering new possibilities for

wearable and implantable medical devices [

60].

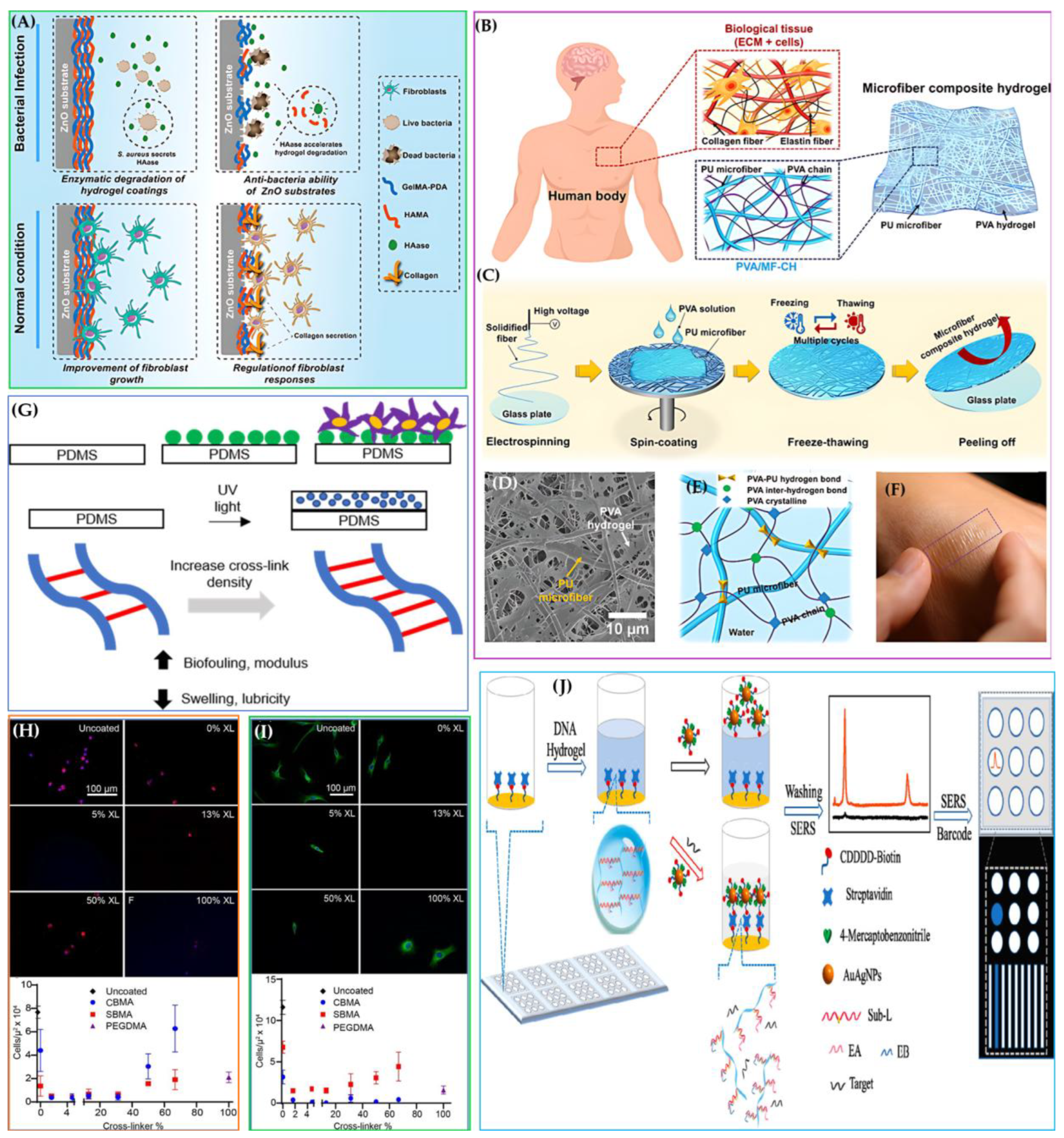

In summary, hydrogel films represent a transformative advancement in biomaterials science, offering a unique combination of biocompatibility, functional versatility, and engineering precision (

Scheme 1). Their ability to mimic biological tissues, respond to environmental cues, and deliver therapeutic agents positions them as key players in the future of personalized medicine, regenerative therapies, and bio-integrated technologies. As fabrication techniques and material designs continue to evolve, hydrogel films are poised to redefine the landscape of biomedical applications [

61,

62,

63].

To support this perspective, the present review provides a structured and comprehensive overview of hydrogel films, beginning with their unique physicochemical properties and fabrication strategies. We then explore their diverse biomedical applications—including wound dressings, drug delivery systems, tissue engineering scaffolds, ophthalmic devices, and implantable biosensors—highlighting both established uses and emerging innovations. Recent advances in stimuli-responsive and nanocomposite hydrogel films are discussed, followed by an analysis of current challenges such as mechanical durability, sterilization, and scalability. Finally, we present future directions for hydrogel film technologies, including personalized designs, AI-guided optimization, and clinical translation, aiming to illuminate their growing impact in next-generation biomedical solutions.

2. Materials and Composition of Hydrogel Films

2.1. Natural Biopolymers: Chitosan, Alginate, Gelatin, and Others

Natural biopolymers remain at the forefront of hydrogel film development due to inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and favorable biological interactions. Chitosan, derived from the deacetylation of chitin, exhibits polycationic properties that enable the formation of electrostatic complexes with negatively charged polymers, enhancing mechanical strength and biological functionality. Chitosan’s chemistry facilitates biocompatibility and antimicrobial activity, making it ideal for wound dressings and drug delivery carriers. Chitosan-based hydrogel films have been extensively studied for these properties and their applications, showing promise across antibacterial dressings and sustained drug release matrices [

64,

65,

66].

Alginate, a polysaccharide obtained from brown seaweed, is widely used in wound healing due to its gel-forming ability in the presence of divalent cations like calcium. Alginate-based hydrogels are notable for their water absorption and swelling capacity, providing moist environments and hemostatic effects, which are beneficial in wound dressings. Optimizing alginate content and crosslinking agents allows tunable properties for various biomedical needs, including enhanced mechanical integrity and controlled degradation [

67,

68].

Gelatin, denatured collagen, offers cell-interactive sequences and biodegradability, making gelatin-containing hydrogels suitable as tissue support matrices, especially in cartilage and soft tissue engineering. These hydrogels support cellular adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, replicating natural extracellular matrix cues crucial for regenerative medicine applications [

68,

69].

2.2. Synthetic and Semi-Synthetic Polymers in Hydrogel Formulations

Synthetic polymers complement natural polymers by enhancing the mechanical strength, stability, and processability of hydrogel films. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) serves as a hydrophilic, biocompatible backbone often used in hydrogel formulations owing to its low toxicity and ability to confer swelling characteristics. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is employed for its film-forming capabilities and mechanical robustness. Copolymer systems incorporating these polymers provide flexibility in tailoring physical, chemical, and biological properties to specific biomedical applications. Several studies have demonstrated PEG and PVA-based hydrogel films with controlled drug release profiles and improved mechanical parameters suited for wound dressings and transdermal delivery [

70,

71,

72].

Polyurethane copolymers have been utilized to fabricate hydrophobic films with enhanced water resistance and mechanical durability. When surface-modified with hydrophilic polymers like polyvinyl pyrrolidone via chemical reactions, these films exhibit concurrent water permeation resistance and biocompatibility, allowing their use in implantable biomedical devices that require protection from internal body fluids while maintaining compatibility [

70,

73].

Hybrid composites and functional modifications represent an advanced approach to hydrogel film design. Incorporation of materials such as humic acids or citric acid-crosslinking agents introduces antibacterial properties and enhances physicochemical behavior without compromising biodegradability. These modifications allow tuning of water absorption, thermal stability, and mechanical integrity, critical for optimized biomedical performance [

74,

75].

2.3. Composite and Multifunctional Hydrogel Films

Composite hydrogel films integrate nanoparticles, emulsions, and bioactive compounds to augment functional properties. The inclusion of Pickering emulsions stabilized by nanomaterials such as oxidized cellulose nanocrystals and silver nanoparticles has been explored to achieve self-crosslinking networks with synergistic wound healing effects, combining antimicrobial and antioxidant activities alongside mechanical reinforcement [

76]. Similarly, nanocomposite films dispersing materials like sodium montmorillonite exhibit pH-responsive drug release and enhanced mechanical strength, making them suitable for anticancer drug delivery [

77].

Natural bioactive extracts, such as mangostin from mangosteen peel and curcumin complexed with cyclodextrins, have been successfully incorporated into hydrogel films to exploit their wound healing, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects. These composite systems improve therapeutic outcomes while maintaining film integrity and biocompatibility [

65,

78]

Further, composite hydrogel films have been engineered with conductive or structural enhancements using materials like carbon nanotubes and graphene, enabling applications in bioelectronics and tissue engineering. These composites demonstrate self-assembly into hierarchical fibrous structures and provide electrical conductivity without impairing biocompatibility, thereby broadening the utility of hydrogels in multifunctional biomedical devices [

79,

80]

3. Synthesis and Fabrication Techniques of Hydrogel Films

3.1. Chemical Crosslinking and Physical Gelation Methods

The synthesis of hydrogel films often employs chemical crosslinking and physical gelation techniques to establish stable polymer networks. Ionic crosslinking is widely used, particularly with biopolymers such as alginate and chitosan, where divalent cations or polyelectrolyte complexes facilitate network formation. Additionally, UV-induced polymerization enables spatial and temporal control over crosslink density, allowing the fabrication of films with tailored mechanical and swelling properties. Schiff base formation, a reaction between amino and aldehyde groups, has been utilized to create dynamic covalent crosslinks within chitosan-alginate networks, enhancing film stability and facilitating controlled degradation [

65,

81,

82].

Crosslinking agents such as glutaraldehyde, potassium persulfate, and sodium tripolyphosphate play critical roles in modulating the properties of hydrogel films. Their concentration and reaction conditions influence gelation time, mechanical strength, and swelling capacity. For example, potassium persulfate initiates free radical polymerizations, yielding biodegradable films with desirable hardness and swelling in biopolymeric systems. Crosslink density often inversely affects swelling but positively impacts mechanical robustness, reflecting the trade-offs that must be balanced during fabrication [

81,

83,

84].

3.2. Fabrication Methods of Hydrogel Films

The fabrication of hydrogel films is a critical determinant of their structural, mechanical, and functional properties. Various methods have been developed to tailor hydrogel films for specific biomedical applications, ranging from wound dressings and drug delivery systems to biosensors and tissue scaffolds. This section discusses both conventional and emerging fabrication techniques, supported by recent research.

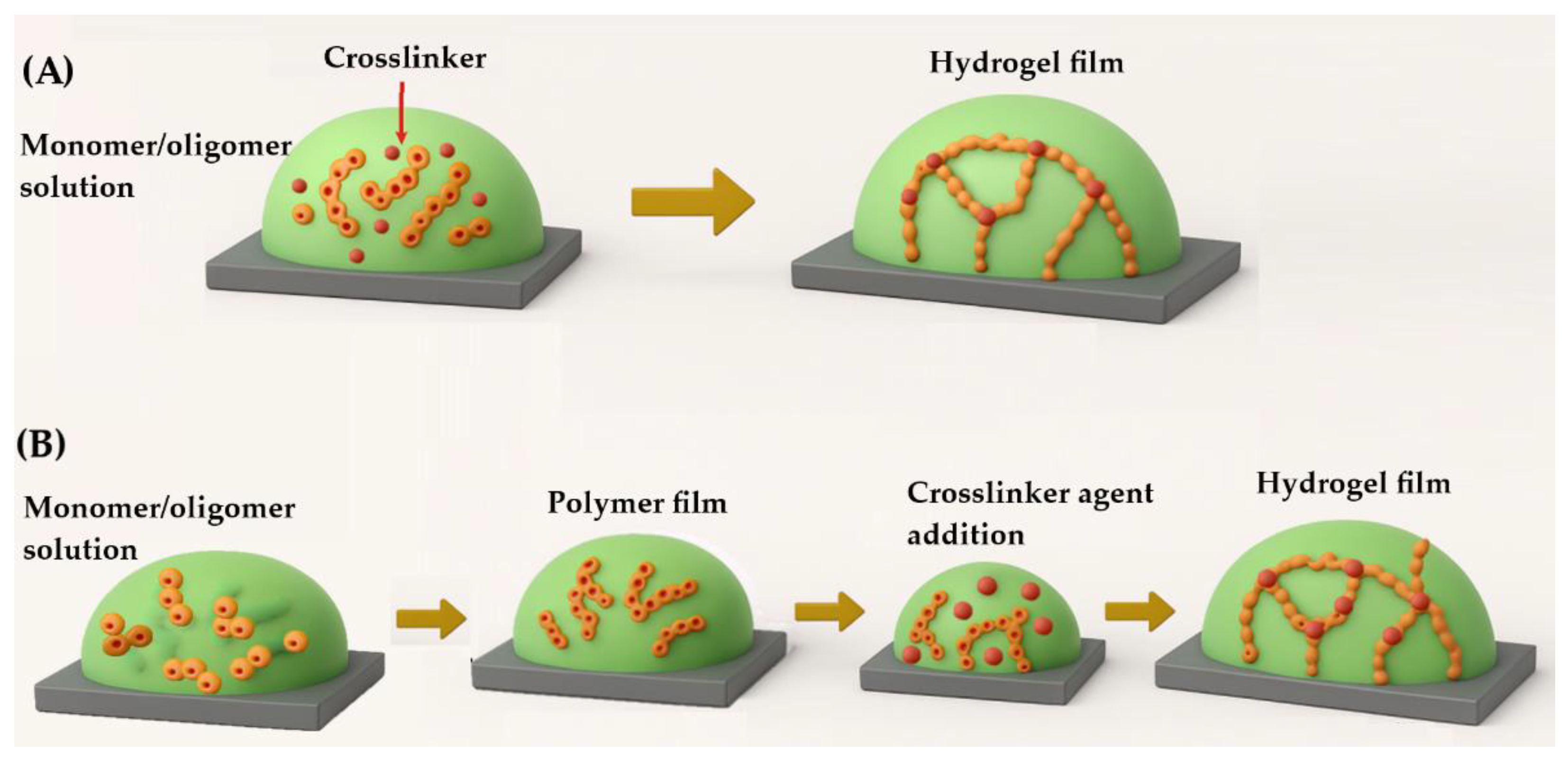

3.2.1. Film Formation

Hydrogel films can be fabricated using various techniques, which differ in their applicability depending on the material system and desired properties. These methods are generally categorized based on the timing of gelation relative to polymerization and film deposition. One key distinction is between in situ crosslinking and post-synthetic crosslinking. In the in situ approach, polymer chains are formed directly from monomers or oligomers during film deposition, with crosslinking occurring simultaneously to establish the hydrogel network [

85]. This process can be initiated by chemical agents or physical stimuli such as UV radiation

, plasma

, or thermal energy, which promote bond formation and network stabilization [

86].

In contrast, post-synthetic crosslinking involves first depositing a polymer film from a soluble precursor onto a substrate, followed by a separate crosslinking step. This secondary process may involve chemical crosslinkers or physical treatments like heat or irradiation, depending on the material and application [

87].

Figure 1 presents a schematic representation outlining the two possible methods for film preparation.

Interestingly, even when strong covalent bonds are present within the hydrogel matrix, the adhesion between the hydrogel film and the substrate is often governed by van der Waals interactions. These weak forces between polymer chains and the substrate surface allow hydrogel coatings to adhere without requiring specific surface functionalization or pre-treatment, making them compatible with a wide range of materials [

88].

Beyond conventional crosslinking methods, microwave-assisted synthesis has emerged as a promising alternative. This technique uses microwave irradiation to induce crosslinking in aqueous polymer solutions, offering advantages such as shorter reaction times

, reduced chemical waste, and higher product yields [

89,

90]. For example, Sun et al. utilized this method to fabricate carbon dot-crosslinked sodium alginate hydrogel films, while Thongsuksaengcharoen et al. applied it to prepare PVA/PVP/CA hydrogel systems

[89,91].

Microwave irradiation not only facilitates efficient crosslinking but also minimizes the need for chemical crosslinkers, potentially resulting in safer and cleaner hydrogel products. This makes it particularly attractive for biomedical applications where biocompatibility and purity are essential.

3.2.2. Preparation Methods

The selection of a suitable method for hydrogel film fabrication depends on several factors, including the chemical nature of the polymer, its adhesion behavior with the substrate, reaction kinetics, and overall cost-effectiveness of the process. Regardless of the specific route chosen, most hydrogel films are formed by applying a precursor solution onto a substrate, followed by drying or curing, which removes the solvent and promotes polymer crosslinking, resulting in a solid film.

A variety of techniques have been developed for this purpose. Below are some commonly used methods:

Solvent Casting [

92]: This straightforward technique involves dissolving the polymer in a solvent, casting the solution onto a substrate, and allowing the solvent to evaporate. The evaporation process leads to film formation and, in the case of hydrogels, is followed by gelation.

Dip Coating [

93]: The substrate is immersed in a polymer solution and withdrawn at a controlled rate, forming a thin film as the solution adheres to the surface.

Spin Coating [

14]: A small volume of polymer solution is dropped onto the center of a substrate, which is then rotated at high speed. Centrifugal force spreads the solution evenly, forming a uniform thin film.

Spray Coating [

94]: The polymer solution is atomized and sprayed onto the substrate, allowing for rapid and scalable film deposition.

Blade Coating [

95]: A blade is used to spread the polymer solution across the substrate, controlling film thickness through blade height and solution viscosity.

Bar Coating [

96]: Similar to blade coating, but uses a cylindrical bar wrapped with wire to distribute the solution evenly across the substrate.

Slot Die Coating [

97]: The polymer solution is dispensed through a narrow slit (die) directly onto the moving substrate, allowing for precise control over film thickness and uniformity.

Photolithography [

98]: A photosensitive polymer is exposed to UV light through a patterned mask, enabling the creation of microstructured hydrogel films with high spatial resolution.

3D Printing [

99]: Hydrogel structures are built layer-by-layer using techniques such as extrusion-based printing or stereolithography (SLA), which uses light to polymerize photosensitive resins with high precision.

These methods can be applied in both in situ crosslinking and post-synthetic crosslinking workflows, depending on the material system and desired film properties. Each technique offers unique advantages, but not all are universally compatible with every polymer type.

Solvent Casting Method

Solvent casting is one of the most accessible and widely used techniques for fabricating hydrogel films. The process begins by dissolving a polymer—along with any necessary additives—into a suitable solvent to form a homogeneous solution. This solution is then applied to a substrate, either by pouring or spreading, and left to dry under controlled conditions. As the solvent evaporates, the polymer chains align and consolidate into a solid film. In hydrogel systems, this is typically followed by a gelation step, which stabilizes the network structure [

Figure 2A][

100]. This method is favored for its simplicity, low cost, and minimal equipment requirements, making it suitable for both laboratory-scale and industrial applications. It also offers flexibility in terms of polymer selection and additive incorporation. The thickness and uniformity of the resulting film can be finely tuned by adjusting the solution concentration, volume, and drying conditions. However, solvent casting does have limitations. The use of organic solvents can pose toxicity risks, and residual solvent may remain trapped within the film matrix, potentially compromising biocompatibility and purity—especially in biomedical applications. Additionally, films produced via this method often exhibit lower mechanical strength compared to those fabricated using more advanced techniques.

Despite these drawbacks, solvent casting remains a valuable method for producing hydrogel films, particularly when ease of fabrication and material versatility are prioritized.

Dip Coating Method

Dip coating is a widely used and straightforward technique for producing thin hydrogel films. The process involves immersing a substrate into a container filled with

a polymer precursor solution, then withdrawing it at a controlled speed. After removal, the coated substrate is typically dried either by air drying, heating, or baking to solidify the film [

Figure 2B]. [

85,

94]. This method is popular due to its simplicity

, scalability, and potential for automation, making it suitable for both laboratory and industrial applications. The thickness of the resulting film is influenced by several factors, including the viscosity of the solution and the withdrawal speed. Generally, a faster withdrawal rate results in a thicker coating, while slower rates produce thinner films.

As the solvent evaporates, the liquid film on the substrate begins to thin and form a wedge-like profile, ending in a distinct drying line. When the speed of the drying front matches the withdrawal speed, the system reaches a steady-state condition. In hydrogel systems, gelation typically occurs in the upper region of the film, where polymer concentration and crosslinking agent levels are highest due to solvent loss and molecular accumulation.

This method allows for uniform coating on complex geometries and is compatible with various polymers and crosslinking strategies. A schematic illustration of the dip coating process is typically used to visualize the dynamics of film formation and drying.

Spin Coating Method

Spin coating is a widely adopted and efficient technique for producing uniform and thin films on flat substrates. The process involves placing a liquid precursor solution—typically containing polymers or hydrogel-forming agents—onto the center of a substrate. The substrate is then rotated at high speeds, typically ranging from 500 to 4000 rpm, which spreads the solution outward due to centrifugal force [

101] [

Figure 2C]. The solution can be applied either while the substrate is stationary or during slow rotation. Once dispensed, the substrate is rapidly accelerated to the desired spin speed. As the substrate spins, the liquid film thins out and begins to dry, forming a solid layer. The final film thickness is influenced by several key parameters:

Spin speed: Higher speeds generally produce thinner films.

Viscosity of the solution: More viscous solutions tend to yield thicker coatings.

Solvent evaporation rate: Faster evaporation can lead to quicker solidification and thinner films.

Volume of the applied solution: Larger volumes may result in thicker layers.

This method is particularly useful for creating hydrogel films with controlled thickness and surface uniformity. It is compatible with both in situ and post-synthetic crosslinking approaches, depending on the formulation and desired properties. A schematic diagram is often used to illustrate the spin coating process and its stages.

Spray Coating and Blade Coating Methods

Spray coating is a versatile technique used to fabricate hydrogel films by applying a fine mist of polymer precursor solution onto a substrate [

102]. This method is particularly effective for producing thin, uniform, and potentially porous coatings, and it can be adapted to substrates with complex geometries, making it suitable for a wide range of biomedical and industrial applications [

Figure 2D]. The process involves atomizing the precursor solution using a pressurized gas stream, which disperses the liquid into fine droplets through a spray nozzle or gun. These droplets are deposited onto the substrate in a controlled manner. As the solvent evaporates, a thin layer of polymer remains, which can then be crosslinked—either chemically or physically—to form a stable hydrogel network. Parameters such as gas pressure, nozzle design, and spray duration can be adjusted to control the thickness, surface roughness, and porosity of the final film. Depending on the formulation and process settings, the resulting hydrogel film may be porous or non-porous, offering flexibility for different functional requirements. Spray coating is valued for its scalability, cost-efficiency, and adaptability, making it suitable for both small-scale research and large-scale production. The ability to fine-tune coating parameters also allows for precise control over film characteristics.

Blade Coating and Bar Coating Methods

Blade coating, also known as doctor blade coating, is a straightforward and efficient technique for fabricating hydrogel films [

103]. In this method, a blade is moved across the surface of a substrate to evenly distribute a polymer solution. A small gap between the blade and the substrate determines the wet film thickness, which is influenced by factors such as the viscosity of the solution, coating speed, and blade geometry [

Figure 2E]. After the solution is spread, it undergoes drying, resulting in a solid hydrogel film. The angle of the blade plays a crucial role in controlling the final film thickness and uniformity:

A 90° blade angle generates high shear, ideal for producing thin and uniform coatings.

A 45° angle offers a balance between removing excess material and retaining some on the surface, yielding medium-thickness films.

Angles between 15° and 30° reduce shear pressure, allowing for thicker coatings, which are beneficial when working with high-viscosity formulations.

Blade coating is compatible with a wide range of polymer viscosities and can be applied to both rigid and flexible substrates. It is also scalable, making it suitable for industrial production of hydrogel films. However, it may not be ideal for producing films thinner than several microns, and the reproducibility of film thickness can be a challenge. Compared to other methods, blade-coated films may exhibit less uniformity, depending on the process parameters and material properties.

Bar Coating Methods

Bar coating is a film deposition technique closely related to blade coating, where a cylindrical rod, typically wrapped with wire, is used to spread a polymer solution across a substrate [

95,

103]. As the rod moves over the surface, the gap between the wire and the substrate determines how much solution is deposited, directly influencing the film thickness. This gap can be adjusted to control the coating outcome, and other parameters such as rod pressure, solution viscosity, and deposition rate can be optimized for better performance. Bar coating is appreciated for its simplicity, low cost, and scalability, especially for large-area coatings. However, it is generally limited to producing films with thicknesses above 10 microns, and the process tends to be slower due to reliance on capillary filling. Additionally, it is not suitable for creating gradient patterns or highly precise structures [

Figure 2F].

Slot Die Coating Methods

Slot die coating is a precision technique used to apply thin films by metering a liquid solution through a narrow slit onto a moving substrate [

97,

104]. The solution flows through a specially designed coating head, forming a controlled meniscus or liquid curtain that ensures uniform deposition. The wet film thickness is determined by the volume of solution dispensed, while other parameters such as flow rate, substrate speed, coating width, and solution viscosity can be fine-tuned to achieve consistent and stable coatings [

Figure 2G]. This method supports both high- and low-viscosity solutions, making it versatile for various materials, including polymers and hydrogels. Slot die coating is highly scalable and suitable for high-speed production, although it requires complex equipment and careful optimization of multiple variables. A schematic diagram typically illustrates the flow dynamics and coating head configuration.

Photolithography Methods

Photolithography is a modern technique widely used in microfabrication and nanotechnology to create patterned hydrogel films [

105]. It involves applying a photosensitive polymer layer—often prepared via spin coating—onto a substrate. When exposed to electromagnetic radiation (e.g., UV light or X-rays), the polymer undergoes chemical changes, such as crosslinking, in the illuminated regions [

Figure 2H]. By using masks, selective exposure can be achieved, allowing for the creation of complex surface patterns. Additionally, by layering polymers with different optical properties, vertical patterning is possible. This method enables high-resolution structuring of hydrogel films, making it ideal for applications in biosensors, microfluidics, and tissue engineering. A schematic typically includes the substrate, light source, mask, and movement axes.

3D Printing Techniques

Three-dimensional (3D) printing enables the rapid fabrication of hydrogel films and structures, allowing for swift design iterations and customization without the need for expensive molds. This technique supports the creation of intricate geometries and complex architectures that are often unachievable through conventional manufacturing methods. A key advantage of 3D printing is its material efficiency—it deposits only the required amount of material, thereby minimizing waste compared to subtractive manufacturing approaches. However, its scalability remains limited, making it more suitable for prototyping or small-batch production rather than mass manufacturing. A schematic overview of the principles of 3D printing applied to hydrogel film fabrication is illustrated in [

Figure 2I] [

106].

Selecting the best method is challenging, as it depends on the film’s application, material properties, cost factors, and often simply on the equipment available to the researchers or organization.

Table 1 shows a comparison of the main characteristics of these methods.

4. Unique Properties of Hydrogel Films

Hydrogel films possess a distinctive combination of physicochemical and biological properties that make them highly suitable for biomedical applications. Their thin-film format, high water content, permeability control, and tissue-conforming behavior enable them to function effectively in wound healing, drug delivery, tissue engineering, and biosensing.

4.1. Thin-Film Architecture and Flexibility

Hydrogel thin films, typically fabricated with micrometer-scale thicknesses, have emerged as a versatile platform for biomedical applications due to their ability to conform intimately to soft, irregular biological surfaces. This thin-film architecture not only enhances tissue contact and drug absorption but also improves mechanical adaptability, making it ideal for applications requiring minimal invasiveness and high biocompatibility.

The flexibility of hydrogel films is largely attributed to their high water content and polymeric network structure, which mimics the extracellular matrix (ECM). These properties allow them to maintain softness

, stretchability

, and permeability, essential for dynamic biological environments. For instance, Gong et al. emphasized the importance of double-network hydrogels in achieving both toughness and flexibility, which has inspired the design of thin-film variants for wearable and implantable devices [

110].

Recent advancements have focused on optimizing the mechanical strength of thin hydrogel films without compromising their flexibility. Nguyen et al. introduced a novel thin-film hydrogel (TFH) with a thickness of approximately 100 µm and 60% water content, synthesized via hydrophobic benzene–benzene interactions [

111]

. These TFHs exhibited remarkable mechanical properties, including a tensile strength of 2.35 MPa and a Young’s modulus of 4.7 MPa

, along with excellent environmental stability

, making them suitable for use as biological membranes and scaffolds

. Moreover, thin-film hydrogels have been explored for ocular applications, such as corneal patches, where transparency, oxygen permeability, and conformability are critical. For example, Maulvi et al. (2016) developed a hydrogel-based contact lens for sustained drug delivery to the eye, demonstrating the potential of thin-film hydrogels in ophthalmology [

112].

In transdermal drug delivery, thin hydrogel films serve as adhesive patches that can deliver therapeutic agents through the skin in a controlled manner. Their moisture-retaining and non-irritating nature makes them superior to traditional patches. Studies by Ngo et al. have shown that incorporating nanocarriers into hydrogel films can further enhance drug loading and release profiles [

113].

Additionally, implant coatings made from hydrogel films can reduce foreign body responses and improve integration with host tissues. Their ability to be functionalized with bioactive molecules or antimicrobial agents adds another layer of utility in regenerative medicine and infection control.

In summary, the thin-film architecture of hydrogels offers a unique combination of mechanical compliance, biocompatibility, and functional versatility, making them indispensable in next-generation biomedical devices and therapies.

4.2. High Water Content

Hydrogels are composed of three-dimensional, hydrophilic polymer networks capable of absorbing and retaining substantial amounts of water—often exceeding 90% by weight. This high water content closely mimics the extracellular matrix (ECM) of natural tissues, creating a moist, nutrient-rich, and mechanically compliant environment that supports cellular functions and tissue regeneration.

The water-rich nature of hydrogels plays a pivotal role in their biocompatibility. As highlighted by researchers, the porous and hydrated structure of hydrogels facilitates oxygen and nutrient diffusion, promotes cell adhesion and proliferation, and minimizes mechanical mismatch with soft tissues. These characteristics make hydrogels particularly suitable for applications in wound healing

, tissue engineering

, and implantable devices [

114]. Moreover, the low interfacial tension between hydrogel surfaces and biological tissues reduces the risk of inflammation and immune rejection. Studies have shown that hydrogels can modulate the foreign body response by minimizing fibrotic encapsulation, especially when engineered with bioinert or bioactive surface chemistries [

115],[

116]. Wei et al. further emphasized that the elastic moduli of many hydrogels are comparable to those of soft biological tissues (ranging from a few kPa to hundreds of kPa), which is critical for maintaining mechanical harmony with the host environment [

117]. This mechanical compatibility is essential in applications such as drug delivery systems, where the hydrogel must deform with tissue movement, and in biological electrodes, where soft interfaces reduce tissue damage and improve signal fidelity. In addition, hydrogels can be functionalized with peptides, growth factors, or nanoparticles to enhance their bioactivity and targeted therapeutic performance. For example, Britton et al. developed a hydrogel with embedded exosomes for enhanced skin regeneration, demonstrating how water-rich matrices can serve as both structural and biochemical scaffolds [

118].

Therefore, the high water content of hydrogels is not merely a structural feature but a biomimetic advantage that underpins their biocompatibility, mechanical tunability, and therapeutic potential across a wide range of biomedical applications.

4..3. Permeability and Diffusion Control

Hydrogel films are uniquely suited for biomedical applications due to their selective permeability and diffusion-regulating capabilities. Their hydrated polymer networks allow for the controlled transport of gases, nutrients, and therapeutic agents, which is essential for applications such as sustained drug release, biosensing, wound healing, and tissue regeneration.

The diffusion behavior in hydrogels is governed by several factors, including polymer composition, crosslinking density, pore size, and hydration level. These parameters can be finely tuned to achieve precise control over molecular transport, enabling the design of hydrogels that respond to specific physiological or environmental stimuli. Lavrentev et al. conducted a comprehensive review of diffusion-limited processes in hydrogels, emphasizing their role in drug encapsulation, nutrient delivery, and stimuli-responsive systems [

119]. Their findings highlighted how denser crosslinking reduces pore size and slows diffusion, while loosely crosslinked networks allow for faster transport. This tunability is critical for designing time-controlled drug delivery systems and biosensors that require consistent analyte exchange.

In a complementary study, Kanduč et al. used molecular dynamics simulations to demonstrate that molecular shape, size, and chemistry significantly influence hydrogel permeability [

120]. Their work revealed that collapsed hydrogel states, often induced by environmental triggers (e.g., pH, temperature, ionic strength), exhibit high selectivity by restricting the passage of larger or hydrophobic molecules. This property can be exploited to create smart hydrogels that release drugs only under specific conditions, enhancing therapeutic precision and minimizing side effects.

Furthermore, stimuli-responsive hydrogels—also known as “intelligent” or “smart” hydrogels—have been developed to dynamically alter their permeability in response to external cues. For example, thermo-responsive hydrogels based on poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) undergo a volume phase transition near body temperature, enabling on-demand drug release [

121]. Similarly, pH-sensitive hydrogels have been used in gastrointestinal drug delivery, where they remain stable in the acidic stomach but swell and release their payload in the more neutral intestines [

122].

In tissue engineering, oxygen and nutrient diffusion through hydrogel scaffolds is vital for maintaining cell viability and tissue integration. Hydrogels with gradient permeability or multi-layered structures have been engineered to mimic natural tissue interfaces, such as the skin or cornea, where different layers require distinct transport properties [

123].

Hence, the permeability and diffusion control of hydrogel films are a cornerstone of their functionality in biomedical applications. Through careful design of their network architecture and responsive behavior, hydrogels can be tailored to meet the complex demands of controlled release, biosensing, and regenerative medicine.

4.4. Surface Adhesion and Conformability to Tissues

One of the most compelling features of hydrogel films is their ability to adhere to moist biological surfaces without the need for external adhesives. This intrinsic adhesion, combined with their softness and flexibility, allows hydrogel films to conform intimately to irregular tissue geometries, which is critical for enhancing therapeutic efficacy, sensor accuracy, and mechanical integration in biomedical applications.

Hydrogels achieve this conformability through their low elastic modulus

, hydrated polymeric structure

, and interfacial compatibility with biological tissues. These properties enable them to form tight, non-irritating interfaces with soft organs such as the brain, heart, lungs, and skin. The ability to maintain stable contact even under dynamic physiological conditions makes hydrogel films ideal for implantable devices

, wound dressings

, and bioelectronic interfaces

. A notable example is the work by Chen et al.

, who developed a gelatin-based metamaterial hydrogel film with a tunable elastic modulus ranging from 20 to 420 kPa and a Poisson’s ratio from −0.25 to 0.52 [

124]. These tunable mechanical properties allowed the hydrogel to match the mechanical behavior of ultra-soft tissues, such as the myocardium and pulmonary tissue. The films were successfully used to monitor cardiac deformation and respiratory signals, demonstrating their potential in implantable bioelectronics and real-time physiological monitoring

.

In parallel

, Bovone et al. reviewed advanced strategies for engineering hydrogel adhesion through chemical junction design, including covalent bonding, supramolecular interactions, and dynamic reversible bonds [

125]

. These approaches significantly enhance adhesion strength and durability

, especially in wet and mechanically active environments

. For instance, catechol-functionalized hydrogels, inspired by mussel adhesive proteins, have shown strong and reversible adhesion to wet tissues, making them promising candidates for surgical glues

, biosensors

, and wearable electronics

[126]. Furthermore

, bioinspired adhesion mechanisms—such as those mimicking gecko feet or octopus suckers—have been integrated into hydrogel designs to improve reusability

, directional adhesion, and detachment control. These innovations are particularly valuable in soft robotics

, flexible electronics

, and dynamic tissue interfaces [

127,

128].

Therefore, the surface adhesion and conformability of hydrogel films are key enablers of their success in non-invasive, implantable, and wearable biomedical technologies. By tailoring their mechanical properties and interfacial chemistry, hydrogel films can be engineered to achieve stable, biocompatible, and functional integration with a wide range of biological tissues.

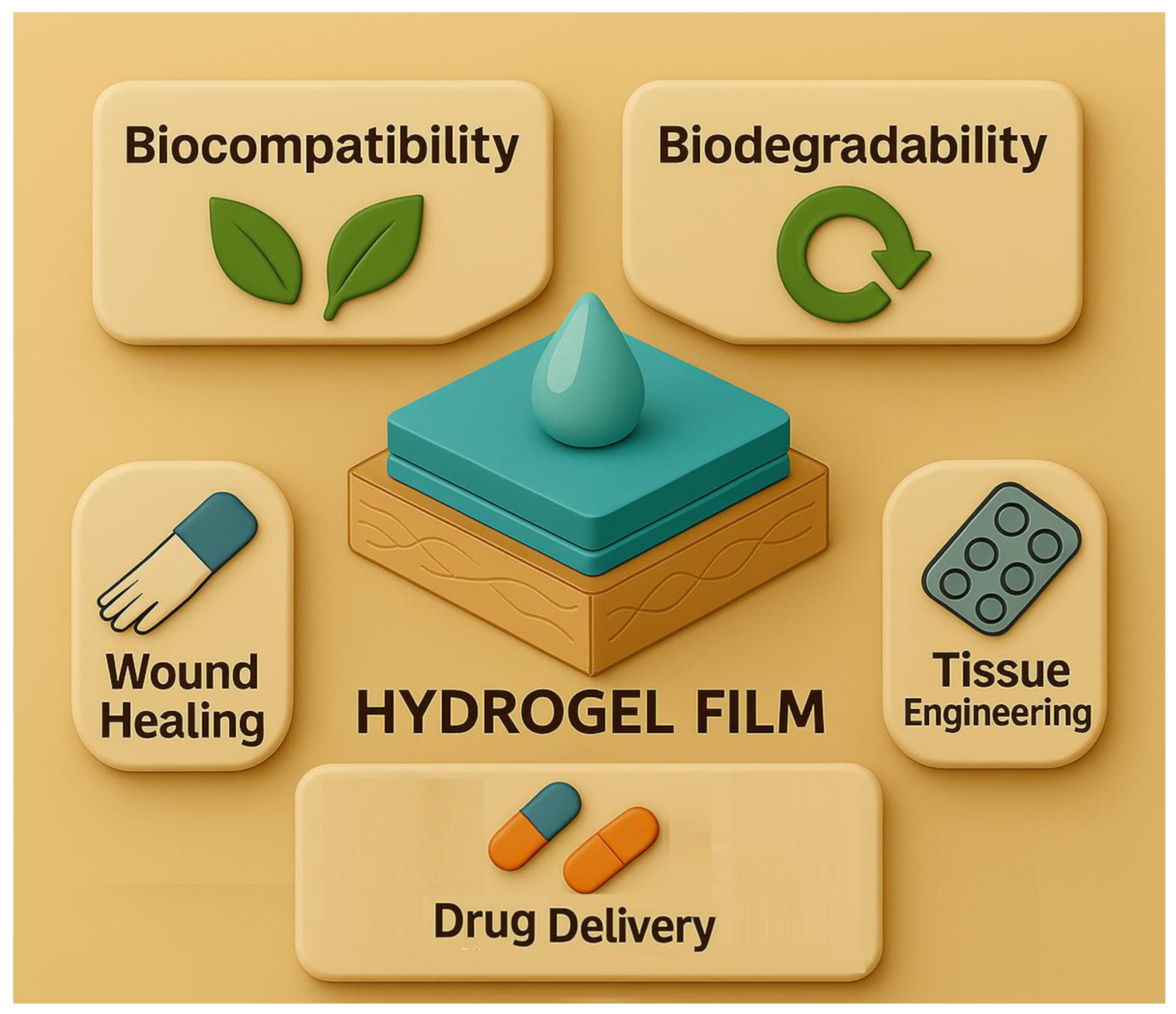

4.5. Biocompatibility of Hydrogel Films for Biomedical Applications

Hydrogel films are extensively used in biomedical applications due to their outstanding biocompatibility, which arises from their high water content, soft mechanical properties, and tunable chemical composition. These features allow hydrogels to mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM), promoting cell adhesion, proliferation, and tissue integration [

129]. Structurally, hydrogels are three-dimensional polymeric networks capable of absorbing over 90% of their weight in water, facilitating nutrient diffusion and reducing mechanical mismatch with soft tissues, thereby minimizing inflammation. Both natural (e.g., gelatin, alginate, hyaluronic acid) and synthetic polymers (e.g., PEG, PVA, polyacrylamide) are commonly used to fabricate biocompatible hydrogel films [

108,

130].

Polymer selection, crosslinking methods, and surface functionalization are critical in enhancing hydrogel-tissue interactions. Hydrogels crosslinked via dynamic covalent bonds or supramolecular interactions show improved tissue adhesion and mechanical resilience while maintaining cytocompatibility [

31,

131,

132,

133]. In vitro studies using cell lines such as L929 fibroblasts and HeLa cells consistently report low cytotoxicity, while in vivo applications demonstrate minimal immune response and favorable tissue remodeling, especially when bioactive or anti-inflammatory agents are incorporated [

134].

Hydrogels are tailored for specific biomedical applications. In drug delivery, they enable localized and sustained release of therapeutics, reducing systemic toxicity. For instance, PAM/CNT nanocomposite hydrogel films exhibit excellent cytocompatibility and hemocompatibility, making them effective carriers for doxorubicin in cancer therapy [

44]. In tissue engineering, hydrogels act as scaffolds that support cell infiltration, angiogenesis, and matrix deposition, with tunable biodegradability and mechanical properties suited to regenerating tissues [

33,

135,

136]. For implantable devices, hydrogel coatings reduce foreign body responses and enhance biointegration, as demonstrated by gelatin-based metamaterial hydrogels compatible with soft organs like the heart and lungs [

137].

Recent advances focus on multifunctional hydrogels that combine biocompatibility with antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, or immunomodulatory properties [

138,

139,

140]. Phenylboronic acid-modified chitosan hydrogels, for example, offer both cytocompatibility and antibacterial activity, making them ideal for wound healing [

141]. Additionally, smart hydrogels responsive to environmental stimuli (e.g., pH, temperature, enzymes) are being developed for precision medicine, enabling adaptive tissue interaction and on-demand therapeutic delivery [

142,

143].

4.6. Biodegradability of Hydrogel Films for Biomedical Applications

Biodegradability is a critical property of hydrogel films used in biomedical applications such as tissue engineering, drug delivery, and wound healing [

2,

4,

144,

145]. Biodegradable hydrogels are designed to safely degrade within the body through enzymatic, hydrolytic, or stimuli-responsive mechanisms, eliminating the need for surgical removal and reducing long-term complications [

1]. These materials align with tissue regeneration timelines or drug release schedules, improving therapeutic outcomes and patient compliance [

146].

Hydrogel degradation occurs via hydrolysis (common in synthetic polymers like PLA, PGA, and PEG-based copolymers), enzymatic breakdown (typical in natural polymers such as gelatin, chitosan, alginate, and hyaluronic acid), or stimuli-responsive mechanisms triggered by pH, temperature, enzymes, light, or oxidative stress [

147,

148,

149,

150,

151]. Design strategies for tunable biodegradability include adjusting crosslinking density, blending fast-degrading natural polymers with stable synthetic ones, and incorporating stimuli-responsive elements for spatiotemporal control over degradation and drug release [

148,

149].

Recent innovations include multi-layered hydrogel films with sequential degradation behavior, enabling phase-specific drug delivery. For example, a double-layer hydrogel system with curcumin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles and pirfenidone-encapsulated gelatin microspheres demonstrated synchronized degradation and drug release aligned with wound healing stages, promoting scar-free regeneration in vivo [

152].

In drug delivery, biodegradable hydrogels act as temporary depots, releasing therapeutic agents over time and degrading into non-toxic byproducts, thereby enhancing bioavailability and minimizing side effects [

153]. In tissue engineering, they serve as scaffolds that support cell infiltration, angiogenesis, and ECM deposition, then degrade to leave behind newly formed tissue [

154]. In wound healing, biodegradable films maintain a moist environment, protect against infection, and degrade in synchrony with tissue repair, eliminating the need for dressing removal [

152,

155].

However, safety concerns remain. Partial degradation can produce toxic monomers or oligomers [

156]. For instance, while PEG is generally safe, its monomer ethylene glycol is nephrotoxic and neurotoxic [

157]. Short-chain degradation products may accumulate in organs or cross the blood-brain barrier, posing risks [

158]. Therefore, evaluating the biocompatibility of degradation byproducts is essential, especially for long-term or implantable applications.

In summary, the biodegradability of hydrogel films is a key enabler of their success in biomedical applications. Through rational material design, stimuli-responsive engineering, and toxicity-aware formulation, hydrogel films can be tailored to degrade in harmony with therapeutic needs while ensuring safety, efficacy, and patient comfort [

159,

160]

In contemporary biomedical practice, hydrogel films serve a multifaceted role across a spectrum of applications encompassing wound dressings, sustained drug delivery systems, and scaffolds for tissue engineering. Their water absorption capabilities and biocompatibility allow hydrogel films to create optimal microenvironments for cell growth and regeneration [

65]. Moreover, hydrogels facilitate the controlled release of therapeutic agents, enhancing treatment efficacy while reducing systemic side effects [

66]. The versatility of these systems extends to complex wound care, including chronic and burn wounds, where traditional dressings often fall short. Compared to conventional materials, hydrogel films possess distinct advantages such as the ability to maintain moisture balance, conform to irregular wound surfaces, and provide enhanced patient comfort [

161]. Innovations in polymer design and surface modification have further improved the integration of hydrogel films with biological tissues, minimizing foreign body reactions and promoting healing outcomes [

73]. Looking ahead, the continual development of hydrogel films is anticipated to align with personalized medicine trends, incorporating smart, responsive materials that adapt dynamically to changes in the wound or tissue milieu, thereby offering tailored therapeutic interventions [

162,

163].

4.7. Wound Dressings: Moisture Retention, Antimicrobial, Anti-Inflammatory Incorporation, and Smart Monitoring

Hydrogel films have emerged as versatile platforms in wound care due to their ability to maintain a moist healing environment, deliver therapeutic agents, support tissue regeneration, and enable real-time monitoring. Their hydrophilic nature, biocompatibility, and tunable mechanical properties make them ideal for treating both acute and chronic wounds, including burns, diabetic ulcers, and pressure sores [

164,

165,

166].

Maintaining optimal hydration at the wound site is critical for epithelialization, autolytic debridement, and minimizing scarring. Hydrogel films mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM), facilitating cell migration, proliferation, and angiogenesis [

108,

137,

167]. Commercial products such as Healoderm and Intrasite Gel exemplify clinically successful hydrogel dressings that promote granulation and re-epithelialization while reducing pain and infection risk [

168,

169,

170].

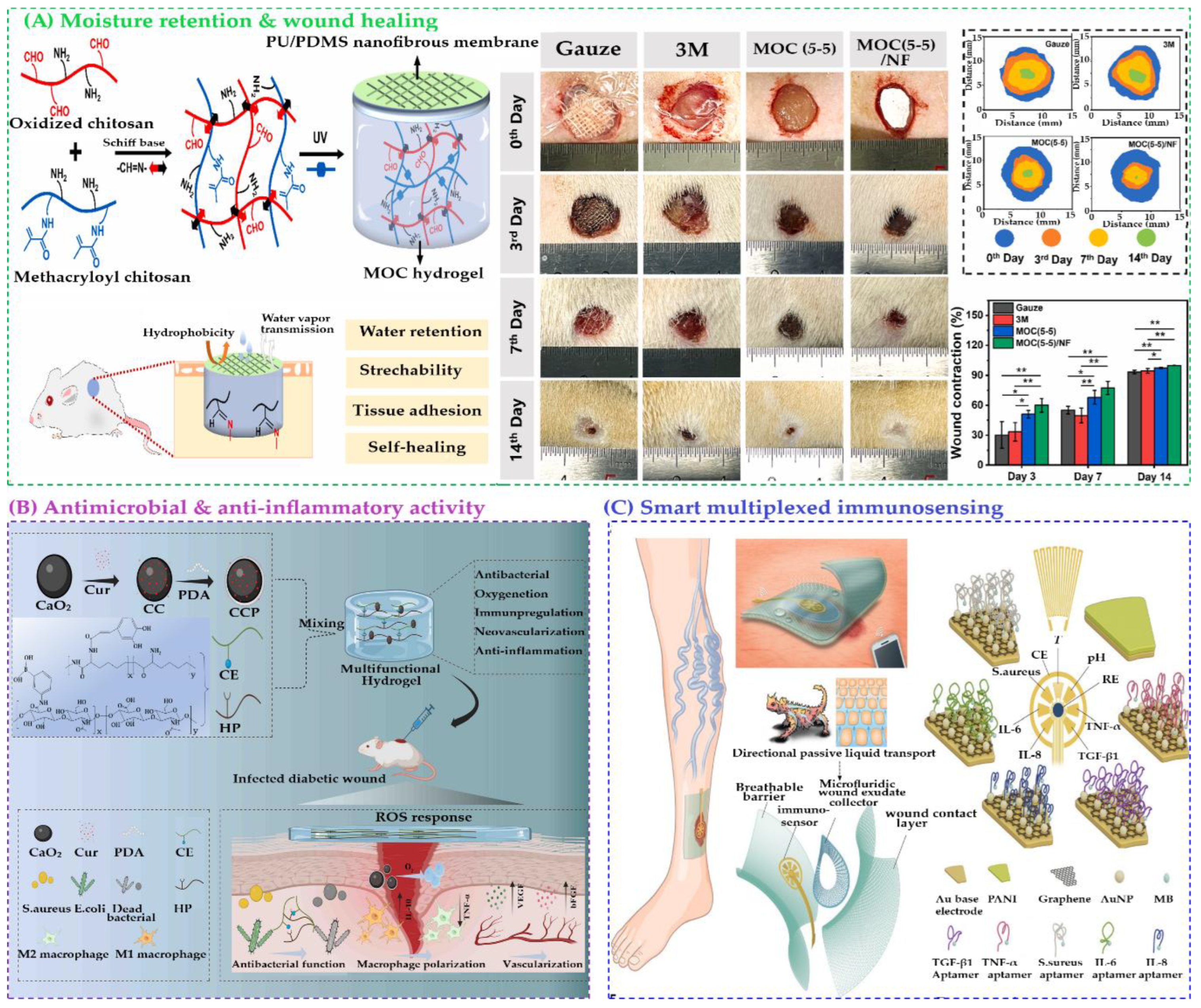

Recent innovations have focused on hydrogel/nanofibrous membrane composites, which combine the moisture-retaining properties of hydrogels with the mechanical strength of nanofibers. Li et al. developed a bilayered PU/PDMS nanofibrous membrane with a self-healing chitosan-based hydrogel, showing enhanced stretchability and water retention (

Figure 3A) [

171]. Cheng et al. introduced a ZIF-8-encapsulated alginate hydrogel/polylactic acid nanofiber (CAH/PLANF) composite with photodynamic antibacterial properties and extracellular matrix (ECM) -like architecture, accelerating healing in infected wounds [

172]. Ruan et al. further reviewed nanohybrid hydrogels integrating antibacterial agents, antioxidants, and stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems [

173].

To address infection and inflammation—two major impediments to wound healing—hydrogel films have been engineered to incorporate antimicrobial agents, anti-inflammatory drugs, and natural bioactives. Ullah et al. developed a collagen-based hydrogel with Sr/Fe-substituted hydroxyapatite nanoparticles, ciprofloxacin, and dexamethasone, demonstrating antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and osteogenic effects [

174]. Pratinthong et al. modified CMC/PVA hydrogel films with citric acid and glutaraldehyde to enhance the anti-inflammatory efficacy of triamcinolone acetonide [

175]. Xi et al. incorporated Fructus Ligustri Lucidi polysaccharide into PVA/pectin hydrogels, resulting in enhanced antibacterial activity, collagen deposition, and reduced inflammation [

176].

Natural extracts have also been widely explored. Chuysinuan et al. formulated CMC/silk sericin hydrogel films with turmeric extract, showing strong antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects [

177]. Fan et al. designed a multifunctional curcumin-loaded PVA/chitosan/sodium alginate hydrogel with potent antimicrobial, antioxidative, and angiogenic properties, promoting macrophage polarization and collagen synthesis in diabetic wound models [

170]. Ahmady et al. embedded thymol-loaded alginate microparticles into chitosan-gelatin films, achieving controlled drug release, broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, and enhanced epithelialization in vivo [

178].

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the synthesis and applications of (A) a polyurethane/polydimethylsiloxane (PU/PDMS) nanofibrous (NF) membrane composite and methacrylated chitosan/oxidized chitosan (MOC (5–5))/NF hydrogel composites for wound healing. Reproduced with permission from [

171], Elsevier; (B) HP-CE@CCP hydrogel dressings, highlighting their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory mechanisms in accelerating the healing of infected diabetic wounds. Reproduced with permission from [

179], American Chemical Society; (C) Flexible microfluidic multiplexed immunosensing platform for point-of-care, in situ profiling of wound microenvironment, inflammation, and infection through multiplexed biomarker detection. Reproduced with permission from [

180], American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the synthesis and applications of (A) a polyurethane/polydimethylsiloxane (PU/PDMS) nanofibrous (NF) membrane composite and methacrylated chitosan/oxidized chitosan (MOC (5–5))/NF hydrogel composites for wound healing. Reproduced with permission from [

171], Elsevier; (B) HP-CE@CCP hydrogel dressings, highlighting their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory mechanisms in accelerating the healing of infected diabetic wounds. Reproduced with permission from [

179], American Chemical Society; (C) Flexible microfluidic multiplexed immunosensing platform for point-of-care, in situ profiling of wound microenvironment, inflammation, and infection through multiplexed biomarker detection. Reproduced with permission from [

180], American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Cadinoiu et al. created chitosan/PVA biocomposite films with silver nanoparticles and ibuprofen, showing synergistic antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects, validated through in vitro and in vivo studies [

181]. Hashempur et al. developed a chitosan xerogel film with Nigella sativa extract using deep eutectic solvents, demonstrating strong antioxidant and antimicrobial activity against multiple pathogens [

182].

To address chronic infected wounds, which are often exacerbated by persistent inflammation and reactive oxygen species (ROS), Tang et al. developed an ROS-responsive injectable hydrogel composed of ε-polylysine grafted with caffeic acid (EPL-CA) and hyaluronic acid grafted with phenylboronic acid (HP)

. The hydrogel was loaded with CaO

2@Cur-PDA (CCP) nanoparticles

, combining calcium peroxide (CaO

2)

, curcumin (Cur)

, and polydopamine (PDA) (

Figure 3B) [

179]. Upon exposure to the wound microenvironment, the hydrogel gradually dissociates, enabling sequential release of therapeutic agents. Initially, caffeic acid-grafted ε-polylysine (CE) provides antibacterial and antioxidant effects, while hyaluronic acid (HA) mimics the extracellular matrix. Subsequently, CCP decomposes, releasing Cur, which promotes angiogenesis. This multi-phase release strategy aligns with the dynamic stages of wound healing, demonstrating effective bacterial clearance, ROS scavenging, and tissue regeneration in vivo. Boateng et al. formulated Polyox/carrageenan films loaded with streptomycin and diclofenac, achieving sustained drug release, high fluid absorption, and synergistic antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects [

183].

In addition to therapeutic functionalities, smart hydrogel films have been developed for real-time wound monitoring, particularly pH-responsive systems [

184]. These dressings detect changes in wound pH—a key biomarker for infection and healing progression—and respond accordingly. Chronic wounds often exhibit elevated pH levels (above 7.0), indicating bacterial colonization and inflammation, while healing wounds maintain an acidic environment (pH 4.0–6.0) [

185].

Wound pH is a reliable indicator of infection, with elevated levels (7.5–9.0) often signaling bacterial colonization and impaired healing. Gamerith et al. developed a silane-anchored bromocresol purple sensor that changes color from yellow to blue with increasing pH, enhancing visual contrast for infection detection [

186]. Eskilson et al. improved spatial resolution using bacterial nanocellulose dressings embedded with mesoporous silica nanoparticles carrying pH-sensitive dyes, maintaining optimal wound dressing properties [

187]. Electrochemical sensing offers real-time quantification. Rahimi et al. created a flexible pH sensor using laser-scribed ITO electrodes functionalized with polyaniline, achieving −55 mV/pH sensitivity across pH 4–10 and enabling wireless smartphone readout via NFC [

188].

Hydrogel films have emerged as a promising platform for smart, multiplexed immunosensing in chronic wound care due to their biocompatibility, flexibility, and ability to interface directly with biological tissues. Chronic wounds, often caused by disrupted healing mechanisms, require continuous monitoring of multiple biomarkers to guide personalized treatment. Traditional diagnostic methods are limited in scope and accessibility, prompting the development of integrated biosensing systems. To address the complexity of chronic wounds, Gao et al. developed a graphene-based microfluidic immunosensor array that simultaneously detects tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), and transforming growth factor–β1 (TGF-β1)],

S. aureus, pH, and temperature. Clinical trials showed strong correlation between these biomarkers and delayed healing over five weeks (

Figure 3C) [

180]. A notable advancement is the creation of a flexible, hydrogel-based microfluidic platform capable of simultaneously detecting inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, TGF-β1), microbial burden (

Staphylococcus aureus), and physicochemical parameters (pH and temperature). This system, exemplified by the VeCare device, incorporates microdrop functionalization, novel aptamer sequences, and wireless electronics for real-time, smartphone-based data readout. The hydrogel film serves as both a sensing matrix and a wound interface, enabling in situ, point-of-care diagnostics. Clinical validation in animal models and human wound exudates demonstrates its potential to transform chronic wound management by enabling timely, personalized interventions and improving healing outcomes.

Han et al. categorized pH-responsive hydrogel mechanisms into morphological changes via dynamic bonds (e.g., Schiff base, catechol–Fe coordination), swelling behavior through protonation/deprotonation, degradation control using ester or imine bonds, and drug release modulation based on ion concentration and drug-polymer affinity [

189]. These systems integrate optical indicators and electrochemical sensors, enabling color change or electrical signal generation in response to pH fluctuations. Representative studies include Mariani et al.’s textile-based smart bandage with a semiconducting polymer/IrOx pH sensor [

190], and Kaewpradub et al.’s fully-printed wearable bandage-based electrochemical sensor with pH correction [

191]. Du et al. developed dual drug-loaded GelMA/HA-CHO hydrogels with pH-responsive release of gentamicin and lysozyme [

192], while Zhao et al. designed a multilayer hydrogel film (K-E-AGB) for diabetic wounds with glucose-responsive EGF release and early anti-inflammatory action [

193]. Moeinipour et al. created a stimuli-responsive hydrogel film based on hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks (HOFs) for temperature and pH-triggered drug release [

194].

These smart systems not only monitor the wound microenvironment but also actively respond to pathological changes, offering a personalized and proactive approach to wound care. Future directions include multi-parameter sensing (e.g., combining pH with temperature and bacterial load) [

195], personalized therapy through responsive drug release [

185], AI-guided analytics, and 3D bioprinting for customizable hydrogel architectures.

4.8. Hydrogel Films as Cell Culture

Hydrogel films have gained prominence as dynamic platforms for cell culture due to their tunable physicochemical properties, biocompatibility, and ability to mimic the native extracellular matrix. Recent innovations in hydrogel design have focused on enhancing cellular interactions, spatial organization, and mechanical stability to support both mono- and co-culture systems.

One notable approach involves photocrosslinkable dextran-based hydrogel films, which utilize benzophenone-functionalized carboxymethyl dextran (BP-CMD) to form stable networks upon UV irradiation. These films can be reinforced with silica nanoparticles and gelatin microparticles, offering improved mechanical integrity and porosity. Importantly, the covalent immobilization of bioactive molecules such as BMP-2 enables targeted stimulation of cell growth. This system has demonstrated excellent support for both osteoblast and endothelial cell proliferation, making it highly suitable for bone tissue engineering and vascularization studies [

196].

Complementing this, surface-patterned hydrogel films present a versatile scaffold for 2D and 3D co-culture. By integrating magnetic silica rods on the hydrogel surface, these films allow spatial separation and simultaneous culture of different cell types—one embedded within the hydrogel matrix and another adhered to the patterned surface. This dual-architecture mimics tissue interfaces and facilitates the study of cell-cell interactions in a controlled microenvironment. The fabrication process is simple and scalable, offering potential for applications in organ-on-a-chip systems and multi-layered tissue constructs.

Together, these hydrogel film technologies represent a significant advancement in cell culture engineering. Their modularity, bioactivity, and spatial control capabilities make them promising tools for regenerative medicine, tissue modeling, and drug screening platforms [

197].

Hydrogels have a physical structure similar to the natural extracellular matrix, making them excellent materials for cell culture. A novel method was demonstrated by Moreau et al. for encapsulating cells in freestanding poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) hydrogel films

, formed spontaneously through swelling-induced gelation

. Mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3) were suspended in a PVA solution containing growth medium and fetal bovine serum, then poured into wells with dry, un–cross-linked PEG substrates. As the PEG swelled and dissolved, it triggered the formation of freestanding PVA hydrogel membranes (

Figure 4, A-M) [

198].

This process minimized the need for direct handling and maintained aseptic conditions. The resulting films exhibited a thickness gradient (2 mm at edges to 0.5 mm at center). Epifluorescence imaging showed efficient cell encapsulation, with viability reaching ~70% for cells located more than 1 mm from the PEG interface after 24–48 hours. Cells near the interface experienced reduced survival, likely due to hypertonic stress during swelling. This hydrogel environment offers a gentle, supportive, biocompatible and scalable approach for the in vitro cell culture applications.

Hydrogel films designed to replicate the topography and mechanical compliance of the basement membrane offer a biologically relevant substrate for cell culture. These films aim to simulate the native microenvironment that cells experience in vivo, which is critical for maintaining physiological cell behavior.

Garland et al. developed a substrate with nano- to microscale surface features and tissue-like softness, closely resembling the basement membrane. This biomimetic design supports cell adhesion, spreading, and differentiation, particularly for epithelial and stem cells (

Figure 4, N,O) [

199]. The substrate’s compliance and topographical cues were shown to influence cellular mechanotransduction, guiding cell morphology and function more effectively than conventional rigid culture surfaces. Such hydrogel-based substrates provide a more accurate platform for in vitro modeling of tissue behavior, drug testing, and regenerative medicine, bridging the gap between traditional cell culture systems and the complexity of living tissues

4.9. Drug Delivery Systems via Hydrogel Films

Hydrogel films have garnered substantial interest in drug delivery applications due to their unique combination of biocompatibility

, high water content

, and tunable physicochemical properties

. These films, composed of three-dimensional hydrophilic polymer networks, can encapsulate a wide range of therapeutic agents—including small molecules, proteins, peptides, and nanoparticles—making them highly adaptable for various administration routes [

200].

One of the key advantages of hydrogel films is their ability to provide controlled and sustained drug release, which enhances therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects. Hydrogel films offer precise control over drug release kinetics, maintaining therapeutic levels while minimizing dosing frequency and side effects [

200]. Their ability to localize drug delivery reduces systemic toxicity, making them ideal for applications such as wound care and localized chemotherapy [

201]. These systems also address challenges like burst release and premature drug degradation, ensuring a stable therapeutic window [

108].

The adjustable crosslinking and mesh size of hydrogels enable sustained release that is tailored to drug properties and clinical requirements [

202]. For example, ciprofloxacin-loaded hydrogels demonstrated prolonged antibacterial activity and controlled release over 10 hours, following first-order kinetics [

203]. Additionally, effective osteochondral repair requires simultaneous regeneration of both cartilage and subchondral bone, which is often limited by single-agent delivery systems. To address this, Kang et al. developed a supramolecular hydrogel film capable of co-delivering two distinct therapeutic agents: kartogenin@polydopamine (KGN@PDA

) nanoparticles for cartilage regeneration and miRNA@calcium phosphate (miRNA@CaP) nanoparticles for bone repair (

Figure 5A) [

204]. These agents were in situ deposited onto a patterned UPy-modified gelatin hydrogel via metal ion coordination, enabling spatially organized and targeted delivery. The hydrogel system supports controlled release of both KGN and miR-26a, promoting chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation through the JNK/RUNX1 and GSK-3β/β-catenin pathways, respectively. In vivo, the cylindrical hydrogel plug mimicking the Haversian canal structure facilitated integrated regeneration of cartilage and bone, demonstrating enhanced tissue formation and functional restoration.

Transdermal hydrogel patches exploit controlled permeability to deliver drugs systemically while bypassing gastrointestinal degradation and first-pass metabolism, enhancing bioavailability and patient adherence [

206].

Abedini et al. developed dual-anionic hydrogel films using alginate and quince seed gum to deliver curcumin transdermally [

207]. To improve compatibility with the hydrophilic matrix, curcumin was modified with stearic acid, enabling uniform dispersion and sustained release over 48 hours. This system enhanced wound healing markers, demonstrating the potential of combining natural polymers and surface modification for effective transdermal delivery of hydrophobic drugs.

Mucosal films for oral and ocular drug delivery benefit from the adhesive, hydrating, and sustained release properties of hydrogel films, improving therapeutic outcomes in sensitive tissue environments [

200]. The flexibility and conformability of such films greatly increase patient compliance, especially in chronic conditions requiring long-term treatment [

108]. For example, to enhance sublingual delivery of antifungal agents, researchers developed multilayered mucoadhesive hydrogel films incorporating nystatin [

208]. The system combined Ocimum basilicum seed mucilage, thiolated alginate, and dopamine-modified hyaluronic acid, with a polydopamine (PDA) coating to improve adhesion and drug retention. This layered structure enabled controlled and sustained release of nystatin, improving mucosal permeability and therapeutic efficacy. The study highlights the potential of multifunctional hydrogel films for localized delivery of bioactive agents in oral applications.

Özakar et al. developed fast-dissolving hydrogel-based oral thin films incorporating pregabalin and methylcobalamin for improved management of neuropathic pain (

Figure 5B) [

205]. Designed for patients with swallowing difficulties, the films enable rapid disintegration and targeted delivery. The dual-drug system ensures simultaneous release of both agents, enhancing therapeutic efficacy while maintaining biocompatibility and ease of administration. This approach highlights the potential of oral thin films for delivering multiple active compounds in a patient-friendly format.

Hydrogel films have emerged as a promising platform for multi-drug delivery due to their high water content, biocompatibility, and tunable network structures. These properties enable controlled release profiles and spatial separation of therapeutic agents, which are critical for complex treatment regimens such as wound healing, cancer therapy, and immunosuppression.

Recent studies have explored diverse strategies for multi-drug incorporation. Yoon et al. reviewed hydrogel–nanoparticle composites that enable dual-drug delivery through physical embedding, covalent integration, and layer-by-layer assembly [

209]. These designs allow for programmable, multi-phase release, enhancing therapeutic synergy and reducing side effects. Similarly, Manghnani et al. demonstrated how Michael addition-based PEG hydrogels can be chemically tuned to control the release of micro-crystalline fenofibrate [

210]. By altering the crosslinking chemistry, the release duration was modulated from 4 hours to 10 days, offering precise temporal control over drug availability.

Zhang et al. designed a biodegradable double-layer hydrogel film for scar-free wound healing, enabling multi-drug loading and sequential release kinetics (

Figure 5C) [

152]. The lower layer contained curcumin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles for early anti-inflammatory action, while the upper layer housed pirfenidone-encapsulated gelatin microspheres for delayed anti-fibrotic effects. The distinct degradation rates and mechanical properties of each layer facilitated phase-specific drug release, aligning with the wound healing stages. This controlled, time-resolved delivery strategy accelerated tissue regeneration and minimized scarring, demonstrating the hydrogel’s potential for multi-phase therapeutic regulation.

Hu et al. provided a comprehensive review of hydrogel drug delivery systems, emphasizing the role of polymer-drug interactions, crosslink density, and external stimuli (e.g., pH, temperature) in shaping release kinetics [

202]. Their work highlights how hydrogels can be engineered to respond to physiological conditions, enabling site-specific and sustained drug release across various tissues.

Despite these advances, challenges remain in achieving reproducible multi-drug loading, precise spatial control, and predictive modeling of in vivo release behavior. Future research is expected to focus on integrating real-time monitoring systems and developing smart hydrogels capable of adaptive release in response to dynamic biological environments.

4.10. Tissue Engineering

Hydrogel films have garnered significant attention within tissue engineering due to their ability to closely mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM), which is crucial for directing cellular behavior and tissue regeneration. The ECM is inherently hydrated and exhibits a porous, soft, and viscoelastic nature, providing both physical support and biochemical signaling to resident cells. Hydrogel films reproduce this soft, hydrated environment through their three-dimensional polymeric networks, offering a microenvironment conducive to promoting cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. Notably, they ensure sufficient nutrient and gas exchange, necessary for cell viability and function, by virtue of their porous structure [

64,

65].

In contrast to traditional scaffolds made from rigid or synthetic materials, hydrogel films provide enhanced mechanical compliance, which better recapitulates the physiological stiffness of soft tissues, thereby minimizing foreign body reactions and fibrosis risks post-implantation. Their intrinsic biocompatibility allows for seamless integration with host tissues, enabling more effective tissue regeneration. These advantages not only aid in improving cell-matrix interactions but also facilitate the dynamic remodeling characteristic of natural tissues, thus reinforcing the utility of hydrogel films in regenerative medicine [

69].

Hydrogel films have become indispensable in tissue engineering due to their ability to mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM), support cellular functions, and serve as barrier layers or scaffolds for tissue regeneration. Their high water content, biocompatibility, and tunable mechanical properties make them ideal for both soft and hard tissue applications, including skin, bone, cartilage, and mucosal tissues

Barrier-forming hydrogel films are designed to protect damaged tissues

, prevent infection, and regulate biochemical exchange at wound or implant interfaces. These films act as bioadhesive interfaces, promoting tissue integration while preventing microbial infiltration and fluid loss. Recent innovations include Janus hydrogels, which feature asymmetric surfaces—one side optimized for adhesion and integration, the other for anti-fouling and protection [

124]. These structures mimic natural biological barriers and have shown promise in skin and mucosal wound repair

, hemostasis

, and post-surgical sealing

[211]. Biocompatible hydrogel films also demonstrated promising applications in tissue adhesives and sealants as a potential alternative or adjunct to sutures or staples in various clinical indications [

212,

213,

214,

215]. However, traditional adhesive hydrogels often struggle to stick to wet tissues and cannot prevent unwanted tissue adhesion after surgery.

To solve this problem, Cui et al. developed a Janus hydrogel

—a film with two different surfaces: one sticky and one non-sticky (

Figure 6A) [

216]. This was achieved by dipping one side of a negatively charged hydrogel into a solution containing positively charged oligosaccharides. The dipping process created a gradient of electrostatic interactions, resulting in two distinct surfaces. The lightly treated side became highly adhesive, even underwater, due to increased hydrophobicity and better water drainage. It could strongly bond to wet tissues like pig skin, stomach, and intestine. In contrast, the heavily treated side became non-adhesive because the chemical groups responsible for sticking were neutralized. This design allowed the hydrogel to seal internal wounds while preventing external tissue from sticking, which is important for avoiding complications after surgery. In animal tests, the Janus hydrogel successfully repaired stomach perforations in rabbits and degraded naturally over 14 days. Its ability to heal itself in water and its safe interaction with tissues make it a promising material for future medical applications in internal tissue repair and anti-adhesion barriers.

Hydrogels are widely used in wound healing due to their ability to maintain a moist environment and adhere well to tissues, which helps stop bleeding and promote healing. However, traditional hydrogels with uniform structure can cause unwanted tissue adhesion, leading to secondary injuries. To overcome this, Fang et al. developed a Janus hydrogel with two distinct sides using a one-pot fabrication method. This hydrogel, called JPs@PAA-PU, is made from polyacrylic acid (PAA) and polyurushiol (PU), stabilized by special Janus particles. It has a water–oil layered structure without a separate adhesive layer, giving it unique physical and chemical properties (Figure B-F) [