Submitted:

23 January 2024

Posted:

25 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PLA Microsphere Production (200 µm)

2.2. Microsphere Quality Control

2.3. Bioink Preparation

2.4. Three-Dimensional (3D) Printing

2.5. Vapor Sintering (Dichloromethane)

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.7. Micro-Computed Tomography

2.8. Mechanical Stability Testing

3. Results

3.1. Generation of 200 µm Diameter Microspheres

3.2.3. D-McMap Method/Guide

- a continuous uninterrupted printing cycle,

- printing stage temperature remained at 21 °C,

- extrusion pressure was unaltered,

- needle offsets were not varied.

- The pressure required to extrude the ink changed during the printing process, often increasing by 0.5 – 1 bar per extruded 0.25mL of bioink. An analysis of the material showed that the microsphere ink was drying out in the syringe, losing its flow characteristics. Altering the specified ratio of microspheres to CMC and/or altering the concentration of the CMC prevented the proper flow of the ink.

- After two layers, the added weight of subsequent layers onto previous ones caused the first two layers slowly to collapse, as the relative wettish nature of the bioink cannot withstand the pressure. During this process, any pores created by design and printed into the scaffolds were filled (Figure 3 A2, A3).

- On the non-heated print bed, the printed layers did not dry quickly enough to stabilize their shape to prevent the issues raised in point 2.

- Scaffolds printed on a polyimide tape for better adhesion during printing stuck strongly to the tape after 30 minutes drying time already and could not be removed from the platform without breakage.

- Cooling of the printhead with the microsphere/CMC bioink to 4 °C ensured that the bioink continued to properly lubricate the microspheres, which greatly reduced the need for extrusion pressures adjustments during printing. A small pressure change was required only after two layers had been printed. Thereafter, the extrusion pressure needed no further changes. It was observed that only the bioink at the tip of the extrusion syringe, which is outside the cooled area, dried out over time. This issue was counteracted by pausing the printing process as necessary and briefly dabbing it with a sterile water-wetted tissue paper for 5 sec.

- The print stage was kept between 50 °C and 60 °C, and the printing process was paused every two layers of each shape for up to 10 seconds. This action resulted in a distinct improvement in the stability of both external and internal geometric structures (Figure 3 B/C 1-3; Figure 4) despite the added weight of additional layers.

- The implementation of this drying step, however, also resulted in shrinkage of 0.1 – 0.15mm in the printed scaffold every two layers, causing the follow-on layers to be out of alignment. To compensate for this, a cylinder was designed comprised of multiple-cylinder sections, with each section being 2 layers thick and taking into consideration the 0.1 – 0.15mm shrinkage of the drying step. This ensured that all layers connected up properly and the final 3D structure maintained its overall shape-integrity producing a symmetrical 3D-printed shape, each time (Figure 3 B/C 1).

- The polyimide tape was replaced with aluminum foil. The printed structure could easily be removed from the foil, even if only partially dried after 30 minutes. This made the collection of scaffolds very simple.

3.3. Multicomposite 3D-Printed Hemisphere

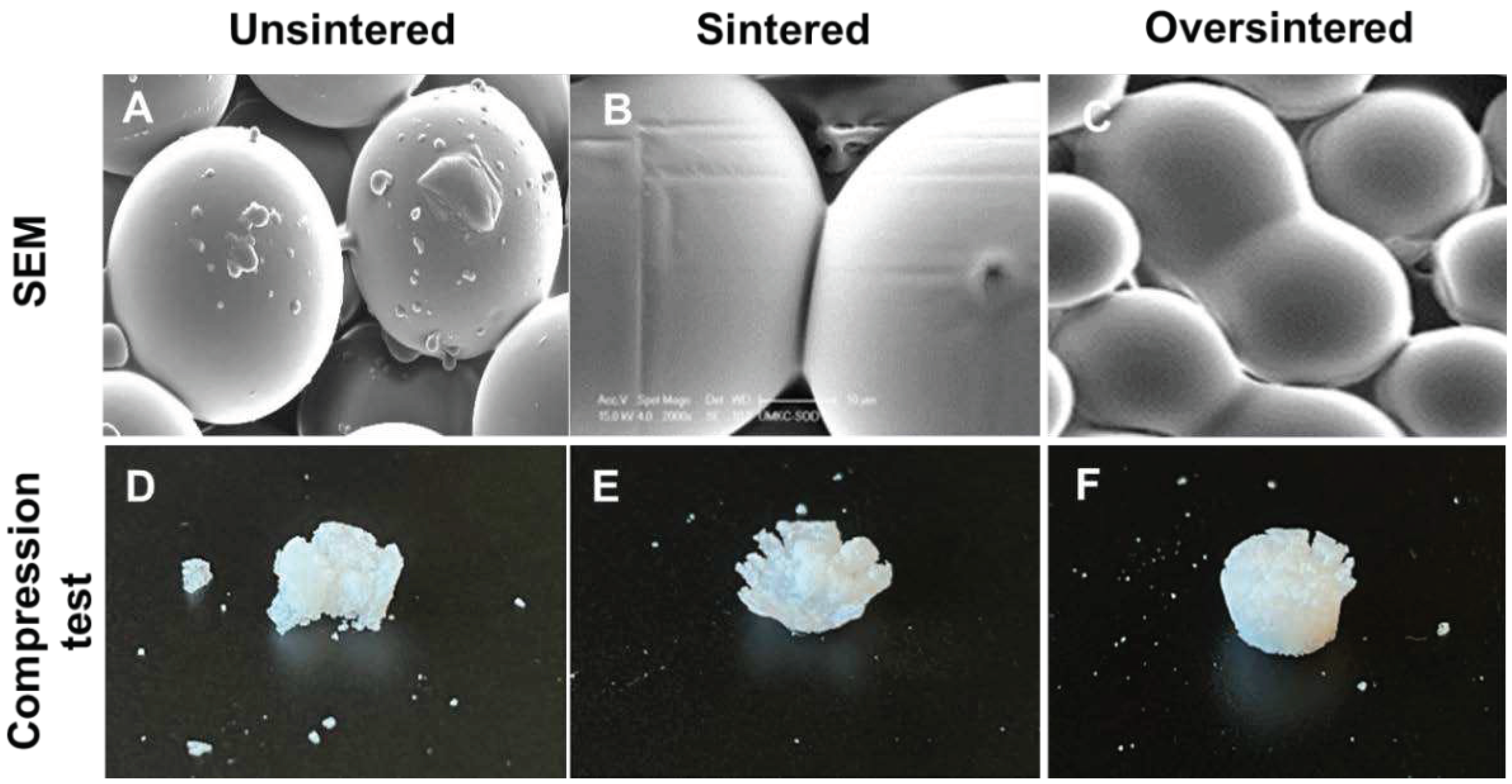

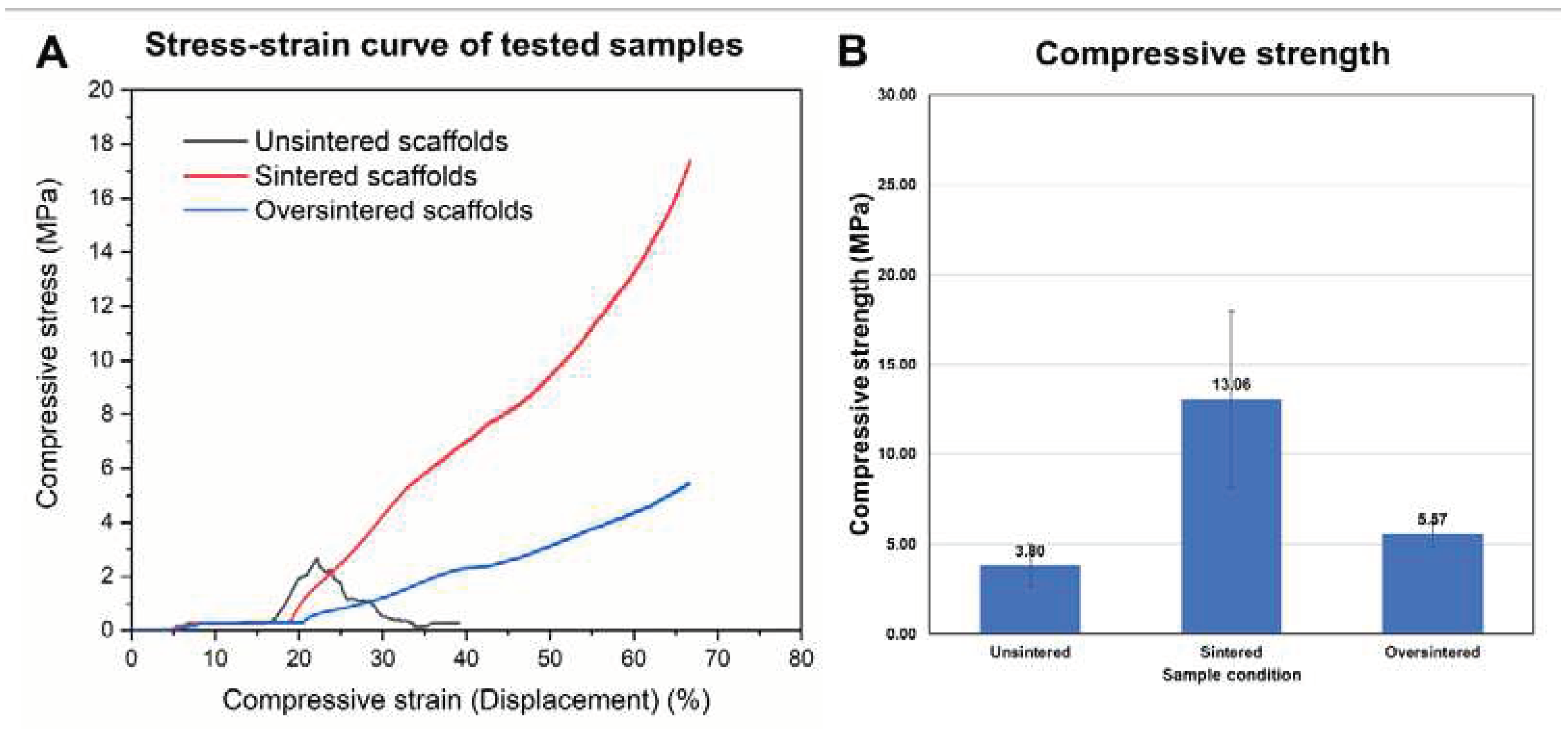

3.4. Sintering Periods and Mechanical Stability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| mm | millimeters |

| µm | micrometers |

| PLGA | Poly (lactic-co-glycolic) acid |

| PLA | Poly-(lactic) acid |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| MicroCT/µCT | Micro Computed Tomography |

| 3D | Three Dimensional |

| w/v | Weight/Volume (%) |

| v/v | Volume/Volume (%) |

| RPM | Revolutions Per Minute |

| PVA | Polyvinyl Alcohol |

| Hz | Hertz |

| Sec | Seconds |

| Min | Minutes |

| Amp | Amplitude |

| g | Grams |

| °C | Degrees Celsius |

| CMC | carboxymethyl cellulose |

| 16G/18G | 16 Gauge/18 Gauge |

| mm/s | millimeter/second |

| SE | secondary electron |

| XL30 ESEM-FEG | Environmental Scanning Electron Microscope |

| Au-Pd | gold-palladium |

| kV | kilovolts |

| μA | micro-ampere |

| mL | milliliters |

| DCM | dichloromethane |

| TGF | transforming Growth Factor |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| DNA | deoxyribose nucleic acid |

References

- Su, Y.; Zhang, B.; Sun, R.; Liu, W.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Chen, C. PLGA-based biodegradable microspheres in drug delivery: recent advances in research and application. Drug Deliv 2021, 28, 1397–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.A. The manufacturing techniques of various drug loaded biodegradable poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) devices. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2475–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Votruba, A.R.; Farokhzad, O.C.; Langer, R. Nanotechnology in drug delivery and tissue engineering: from discovery to applications. Nano Lett 2010, 10, 3223–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wenk, E.; Zhang, X.; Meinel, L.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G.; Kaplan, D.L. Growth factor gradients via microsphere delivery in biopolymer scaffolds for osteochondral tissue engineering. J Control Release 2009, 134, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.M.; Rodrigues, M.T.; Silva, S.S.; Malafaya, P.B.; Gomes, M.E.; Viegas, C.A.; Dias, I.R.; Azevedo, J.T.; Mano, J.F.; Reis, R.L. Novel hydroxyapatite/chitosan bilayered scaffold for osteochondral tissue-engineering applications: Scaffold design and its performance when seeded with goat bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 6123–6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalumon, K.T.; Sheu, C.; Fong, Y.T.; Liao, H.T.; Chen, J.P. Microsphere-Based Hierarchically Juxtapositioned Biphasic Scaffolds Prepared from Poly(Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid) and Nanohydroxyapatite for Osteochondral Tissue Engineering. Polymers (Basel) 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, J.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Hu, L.; Chen, Z.; Backman, L.J.; Zhang, W. Topographic Orientation of Scaffolds for Tissue Regeneration: Recent Advances in Biomaterial Design and Applications. Biomimetics (Basel) 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Khan, Y.; Berkland, C.J.; Laurencin, C.T.; Detamore, M.S. Microsphere-Based Scaffolds in Regenerative Engineering. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2017, 19, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, M.P.; Chavali, M.S. Recent advances in biomaterials for 3D scaffolds: A review. Bioact Mater 2019, 4, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, L. Controlled dual delivery of low doses of BMP-2 and VEGF in a silk fibroin-nanohydroxyapatite scaffold for vascularized bone regeneration. J Mater Chem B 2017, 5, 6963–6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafder, S.; Koch, A.; Jun, Y.; Chou, C.; Awadallah, M.R.; Lee, C.H. Micro-precise spatiotemporal delivery system embedded in 3D printing for complex tissue regeneration. Biofabrication 2016, 8, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legemate, K.; Tarafder, S.; Jun, Y.; Lee, C.H. Engineering Human TMJ Discs with Protein-Releasing 3D-Printed Scaffolds. Journal of Dental Research 2016, 95, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito Corcione, C.; Gervaso, F.; Scalera, F.; Padmanabhan, S.K.; Madaghiele, M.; Montagna, F.; Sannino, A.; Licciulli, A.; Maffezzoli, A. Highly loaded hydroxyapatite microsphere/ PLA porous scaffolds obtained by fused deposition modelling. Ceramics International 2019, 45, 2803–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, L.E.; Dang, H.P.; Knackstedt, M.A.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Tran, P.A. 3D printed Polycaprolactone scaffolds with dual macro-microporosity for applications in local delivery of antibiotics. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2018, 87, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, H.P.; Shabab, T.; Shafiee, A.; Peiffer, Q.C.; Fox, K.; Tran, N.; Dargaville, T.R.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Tran, P.A. 3D printed dual macro-, microscale porous network as a tissue engineering scaffold with drug delivering function. Biofabrication 2019, 11, 035014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hing, K.A.; Annaz, B.; Saeed, S.; Revell, P.A.; Buckland, T. Microporosity enhances bioactivity of synthetic bone graft substitutes. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Riley, L.; Schirmer, L.; Segura, T. Granular hydrogels: emergent properties of jammed hydrogel microparticles and their applications in tissue repair and regeneration. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2019, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, Q.L.; Choong, C. Three-dimensional scaffolds for tissue engineering applications: role of porosity and pore size. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2013, 19, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaji, N., Sheibat-Othman, N., Saadaoui, H., Elaissari, A., Fessi, H. Colloidal and physicochemical characterization of proteincontaining poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) microspheres before and after drying. e-Polymers 2009, 9, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Diggle, B.; Tan, M.L.; Viktorova, J.; Bennett, C.W.; Connal, L.A. Extrusion 3D Printing of Polymeric Materials with Advanced Properties. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2020, 7, 2001379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava-Arzaluz, M.G.; Piñón-Segundo, E.; Ganem-Rondero, A. Sucrose Esters as Transdermal Permeation Enhancers. In Percutaneous Penetration Enhancers Chemical Methods in Penetration Enhancement; 2015; pp. 273-290.

- Klar, R.M. The Induction of Bone Formation: The Translation Enigma. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2018, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BaoLin, G.; Ma, P.X. Synthetic biodegradable functional polymers for tissue engineering: a brief review. Sci China Chem 2014, 57, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.M.; Liu, X. Advancing biomaterials of human origin for tissue engineering. Prog Polym Sci 2016, 53, 86–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Seitz, D.; Konig, F.; Muller, P.E.; Jansson, V.; Klar, R.M. Induction of Articular Chondrogenesis by Chitosan/Hyaluronic-Acid-Based Biomimetic Matrices Using Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Hausdorf, J.; Niethammer, T.R.; Jansson, V.A.; Klar, R.M. Temporal TGF-beta Supergene Family Signalling Cues Modulating Tissue Morphogenesis: Chondrogenesis within a Muscle Tissue Model? Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Muller, P.E.; Aszodi, A.; Klar, R.M. Osteochondrogenesis by TGF-beta3, BMP-2 and noggin growth factor combinations in an ex vivo muscle tissue model: Temporal function changes affecting tissue morphogenesis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2023, 11, 1140118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, S.; Zhang, Q. Preparation of chitosan/nano hydroxyapatite organic-inorganic hybrid microspheres for bone repair. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2015, 134, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chang, B.; Dong, H.; Liu, X. Functional microspheres for tissue regeneration. Bioact Mater 2023, 25, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, J.; Rodriguez, M.; Leal, D.; Noris-Suarez, K.; Gonzalez, G. Chitosan-collagen-hydroxyapatite membranes for tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2022, 33, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faruq, O.; Kim, B.; Padalhin, A.R.; Lee, G.H.; Lee, B.T. A hybrid composite system of biphasic calcium phosphate granules loaded with hyaluronic acid-gelatin hydrogel for bone regeneration. J Biomater Appl 2017, 32, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Lee, B.T. A combination of biphasic calcium phosphate scaffold with hyaluronic acid-gelatin hydrogel as a new tool for bone regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A 2014, 20, 1993–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; King, M.W. Biodegradable Polymers as the Pivotal Player in the Design of Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Adv Healthc Mater 2020, 9, e1901358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, R.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Shan, M.; Zhong, X.; Xing, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Cartilage Extracellular Matrix Scaffold With Kartogenin-Encapsulated PLGA Microspheres for Cartilage Regeneration. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8, 600103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims-Lucas, S., Good, M., Vainio, S.J. Organogenesis: From Development to Disease; 2017.

- Safavi, H.R.; Amiri, A.; Baniassadi, M.; Zolfagharian, A.; Baghani, M. An anisotropic constitutive model for fiber reinforced salt-sensitive hydrogels. Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures 2023, 30, 4814–4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Bodaghi, M.; Xiang, Y.; Zolfagharian, A. 3D-Printed Phase-Change Artificial Muscles with Autonomous Vibration Control. Advanced Materials Technologies 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M., Morris, C.P., Ellis, R.J., Detamore, M.S., Berkland, C. Microsphere-Based Seamless Scaffolds Containing Macroscopic Gradients of Encapsulated Factors for Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2008, 14, 299–309. [CrossRef]

- Kacarevic, Z.P.; Rider, P.M.; Alkildani, S.; Retnasingh, S.; Smeets, R.; Jung, O.; Ivanisevic, Z.; Barbeck, M. An Introduction to 3D Bioprinting: Possibilities, Challenges and Future Aspects. Materials (Basel) 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, S.; Mandal, S.S.; Bauri, S.; Maiti, P. 3D bioprinting and its innovative approach for biomedical applications. MedComm (2020) 2023, 4, e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, V.; Rustgi, A.K. Metaplasia: tissue injury adaptation and a precursor to the dysplasia-cancer sequence. Nat Rev Cancer 2017, 17, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgovnick, A.; Schumacher, B. DNA repair mechanisms in cancer development and therapy. Front Genet 2015, 6, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gungor-Ozkerim, P.S.; Inci, I.; Zhang, Y.S.; Khademhosseini, A.; Dokmeci, M.R. Bioinks for 3D bioprinting: an overview. Biomater Sci 2018, 6, 915–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, A.; Levato, R.; D'Este, M.; Piluso, S.; Eglin, D.; Malda, J. Printability and Shape Fidelity of Bioinks in 3D Bioprinting. Chem Rev 2020, 120, 11028–11055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.C.; Gillispie, G.; Prim, P.; Lee, S.J. Physical and Chemical Factors Influencing the Printability of Hydrogel-based Extrusion Bioinks. Chem Rev 2020, 120, 10834–10886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, T.S.; Datta, P.; Nesaei, S.; Ozbolat, V.; Ozbolat, I.T. 3D Coaxial Bioprinting: Process Mechanisms, Bioinks and Applications. Prog Biomed Eng (Bristol) 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlberg, B.; Ghuman, H.; Liu, J.R.; Modo, M. Ex vivo biomechanical characterization of syringe-needle ejections for intracerebral cell delivery. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 9194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.J. The significance and use of the friction coefficient. Tribology Intern 2001, 34, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartlick, O., Kicheva, A.,; Gonzalez-Gaitan, M. Morphogen gradient formation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2009, 1, a001255. [CrossRef]

- Shifrin, Y.; Pinto, V.I.; Hassanali, A.; Arora, P.D.; McCulloch, C.A. Force-induced apoptosis mediated by the Rac/Pak/p38 signalling pathway is regulated by filamin A. Biochem J 2012, 445, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).