2.2. Composite Hydrogel Characterization

2.2.1. Rheological Evaluation

Among the six compositions, only two were selected for rheological evaluation. A formulation similar to the S1-S3 compositions, containing 8% gelatin and 7% alginate, was characterized in our previous work [

37]. Furthermore, this study focused on investigating the effects of CaP incorporation on the rheological properties of printable hydrogels. Specifically, we analyzed the polymer-only formulation containing 12% gelatin, 5% alginate, and 1% CMC, alongside the composite with an additional 3% monetite, to evaluate how the inclusion of the inorganic phosphate phase influenced the material behavior.

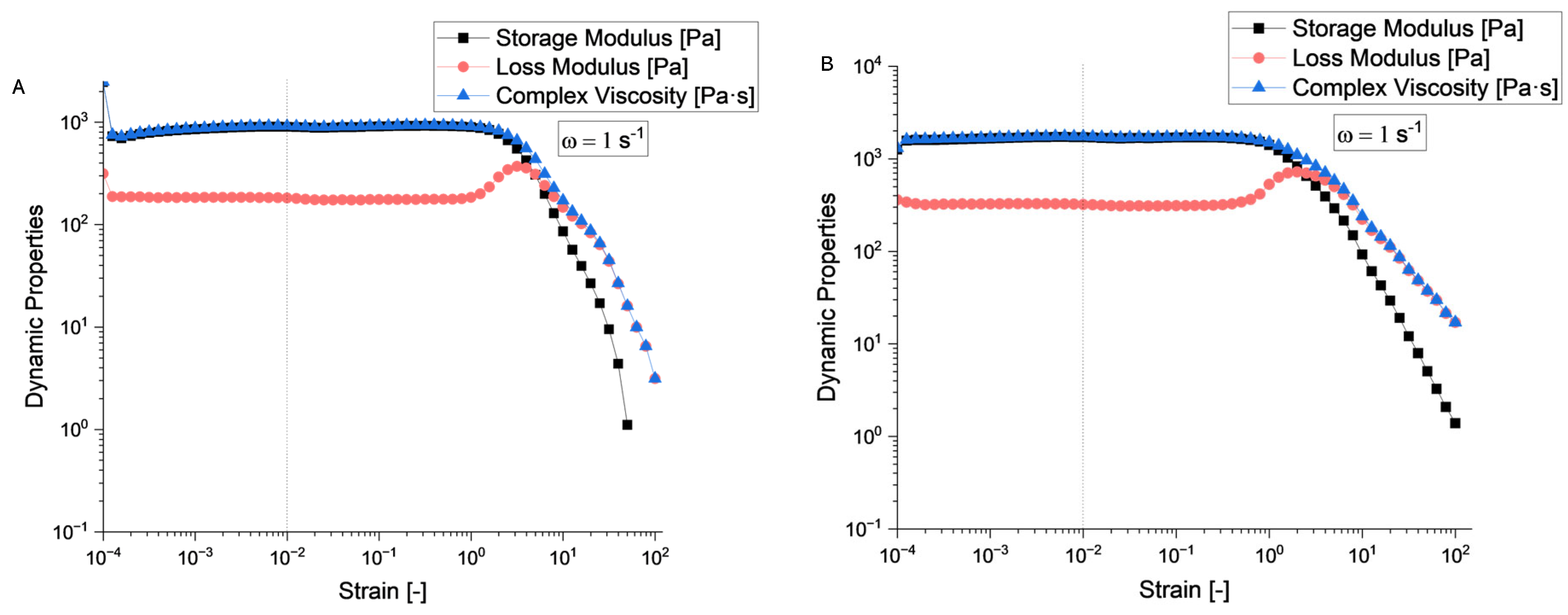

According to the rheological evaluation (

Figure 6 A and

Figure 7 A), sample S4 exhibits a well-defined linear viscoelastic plateau extending from approximately 10

−4 to 10

−1 strain units, where both storage modulus (

G’) and loss modulus (

G”) remain constant at approximately 10

3 Pa. The critical strain marking the end of the linear viscoelastic region (LVR) occurs around

γ = 0.1, beyond which both moduli begin to decrease significantly.

Sample S5 (

Figure 6 B and

Figure 7 B) demonstrates similar behaviour with a slightly more robust structure, maintaining linearity up to comparable strain levels. The storage modulus values are consistent with S4, indicating similar elastic properties in the undeformed state.

Beyond the LVR, both samples exhibit structural breakdown characterized by a rapid decrease in both G’ and G”. This behaviour is typical of structured fluids where increasing deformation amplitude disrupts the internal network structure. The crossover point where G’ = G” occurs at high strain values (around 101), indicating the transition from predominantly elastic to viscous behaviour.

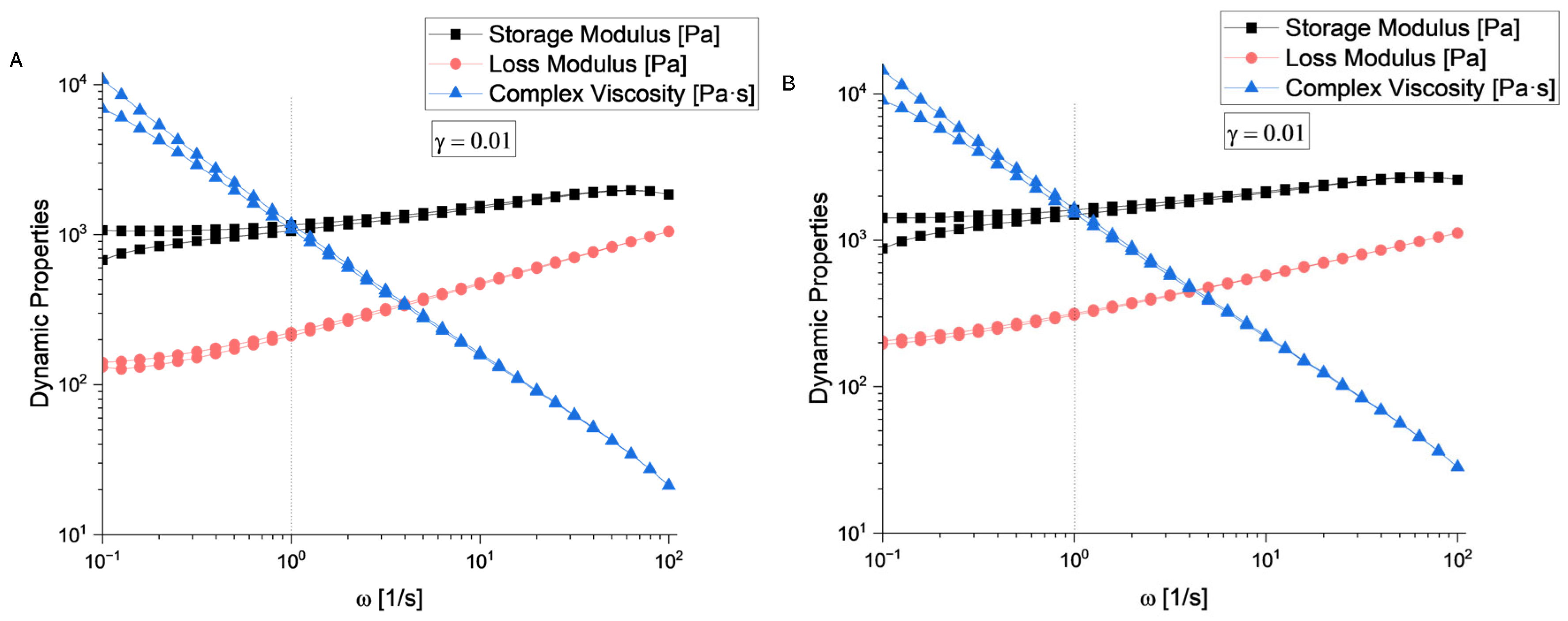

Sample S4 shows a crossover frequency at approximately 1 rad/s where G’ = G”. At low frequencies (long time scales), the loss modulus dominates (G” > G’), indicating liquid-like behaviour. At higher frequencies (short time scales), the storage modulus becomes dominant (G’ > G”), reflecting solid-like behaviour. Sample S5 exhibits a similar crossover pattern but with the intersection occurring at a slightly different frequency, suggesting variations in the characteristic relaxation time between the two samples.

The complex viscosity (η*) for both samples demonstrates typical shear-thinning behaviour across the frequency range. Based on the rheological fingerprints, both samples can be classified as viscoelastic materials with gel-like characteristics. The presence of well-defined LVR, frequency-dependent crossover behaviour, and structured breakdown patterns are consistent with materials possessing a weak gel structure that can be disrupted by moderate deformation, thixotropic potential suggested by the strain-dependent structural breakdown, and intermediate viscoelastic properties between purely elastic solids and viscous liquids.

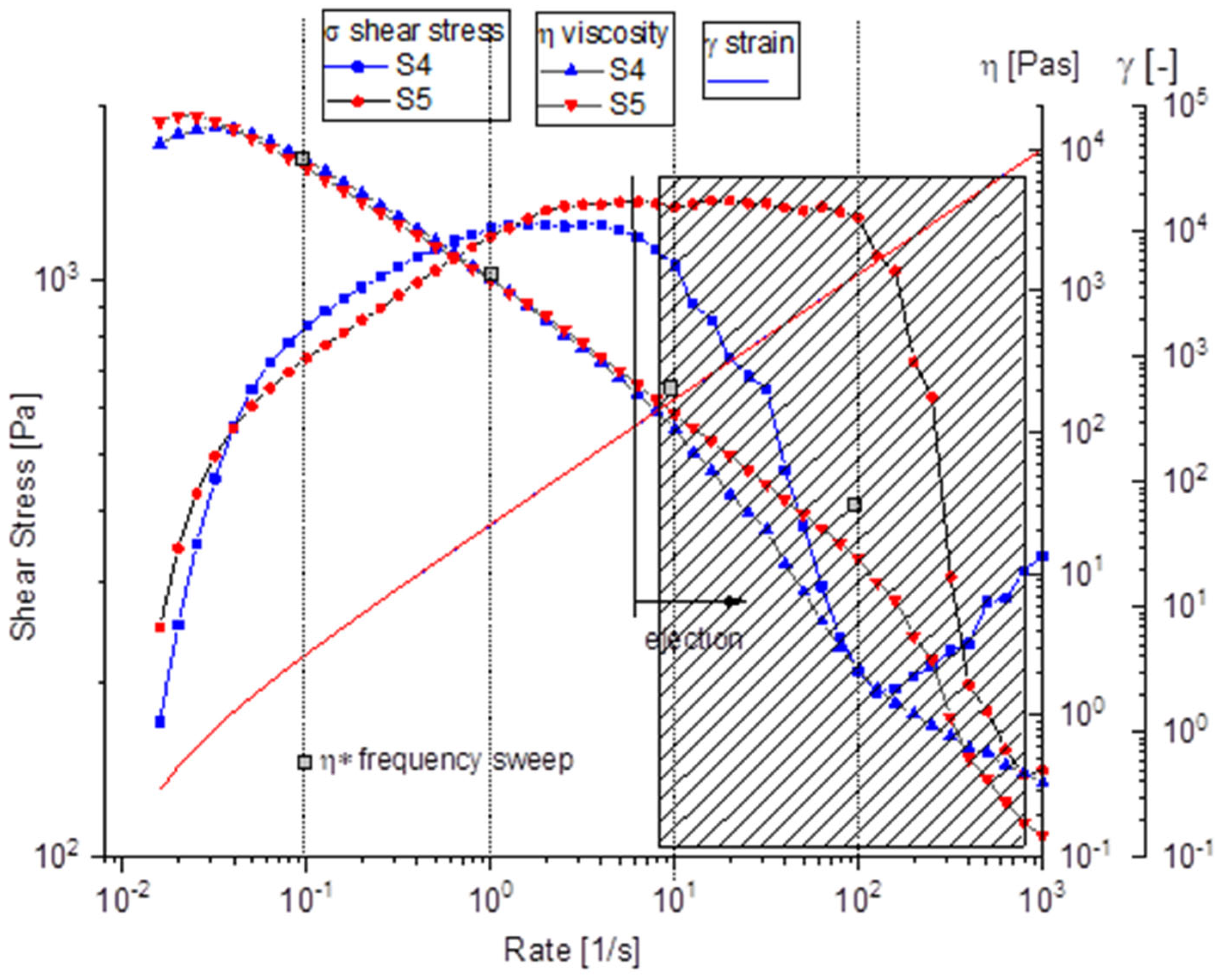

Both samples exhibited typical shear-thinning behavior, wherein viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate, which is typical for structured or polymeric materials. The viscosity profiles of the two samples closely overlapped, as shown in

Figure 8, indicating very similar rheological properties. At low to moderate shear rates, the materials maintained structural integrity, as evidenced by high and relatively stable viscosity and shear stress values. However, beyond a critical shear rate of approximately 100 s

−1, the data became increasingly scattered. This sudden decline corresponds directly to the phenomenon of “ejection from the gap,” during which the sample was visually observed to be expelled from between the rheometer plates at elevated shear rates, resulting in unreliable and artificially reduced measurements. Under the influence of strong centrifugal forces generated during rotation, localized dense regions or aggregates tend to detach from the bulk and are physically thrown outward, particularly at the edges of the plates. These expelled fragments compromise the sample’s integrity within the measurement gap, causing abrupt changes in shear stress at high shear rates and ultimately affecting the accuracy of the rheological assessment in that region [

38]. Both samples S4 and S5 demonstrate remarkably similar rheological signatures, suggesting comparable material compositions and structures, despite the addition of CaP powder in S5.

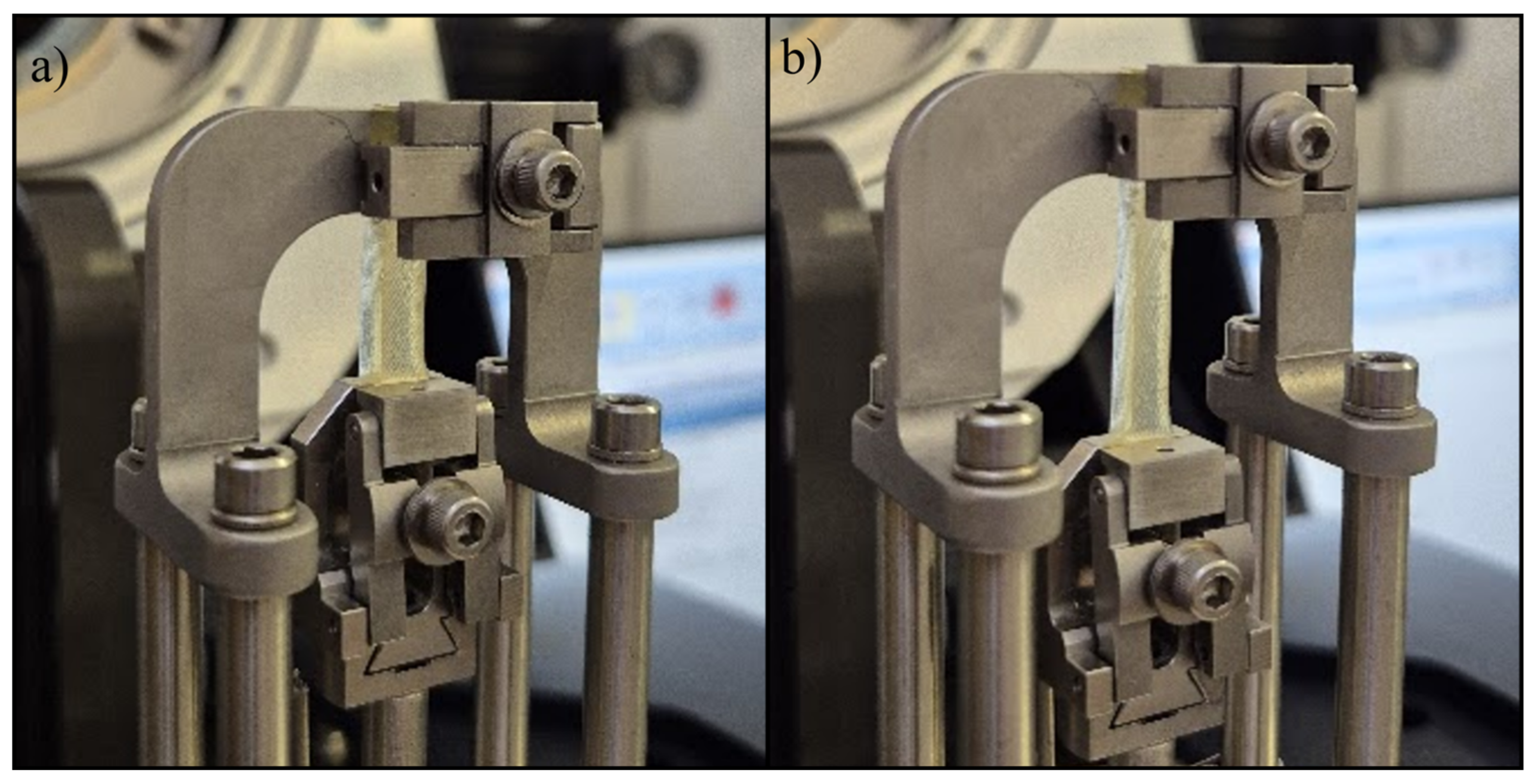

2.2.2. Filament Collapse Testing

Comparative analysis of images captured during 3D printing (

Figure 9) highlights the filament behaviour of sample S6, composed of 12 % gelatin, 5 % alginate, 1 % CMC, and 3 % brushite, which exhibited fracture when spanning gaps of 4 and 5 mm between supporting pillars. This instability is associated with high viscosity and dense paste-like behaviour, despite using a larger 22G nozzle. In contrast, samples S2 and S3, both containing 8 % gelatin, 7 % alginate, 1 % CMC, and 5 % calcium phosphate (monetite in S2, brushite in S3), extruded continuously and uniformly, demonstrating that a more fluid polymeric base supports uninterrupted flow.

Sample S1, consisting of 8 % gelatin, 7 % alginate, and 1 % CMC, without calcium phosphate, produced stable filaments, albeit with minor heterogeneities attributed to air bubble inclusion during preparation. For samples S4 and S5, both with 12 % gelatin and 5 % alginate, differences arose from the addition of 3 % monetite in S5, which did not significantly disrupt filament continuity compared to S4, suggesting that monetite up to this concentration is compatible with network stability. Compared to monetite in S5, brushite in S6 exhibited a more pronounced destabilizing effect, underscoring the importance of CaP type in selecting extrusion parameters.

2.2.3. Extrusion-Based 3D Bioprinting

Six scaffolds were obtained via extrusion-based bioprinting, as shown in

Figure 10, with different hydrogel composition, different degrees of translucidity, based on the amount of CaP powders introduced. Pristine polymeric matrices S1 and S4 are characterized by the presence of air bubbles in the bioprinter cartridge, while S2-S3 and S5-S6 illustrate a homogenous dispersion of the composite phase, with varying degrees of stability, as shown from the shape of the pores.

2.2.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

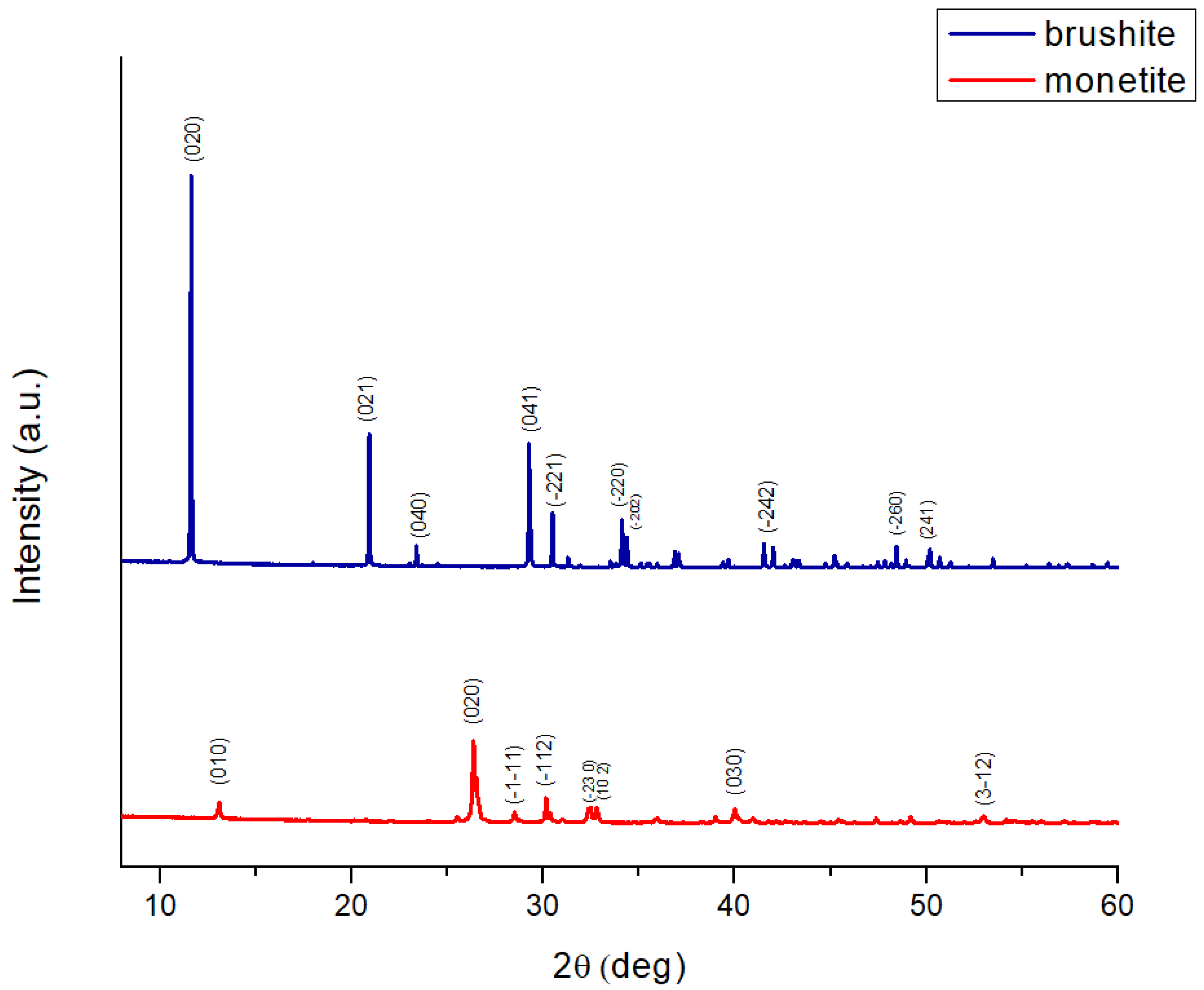

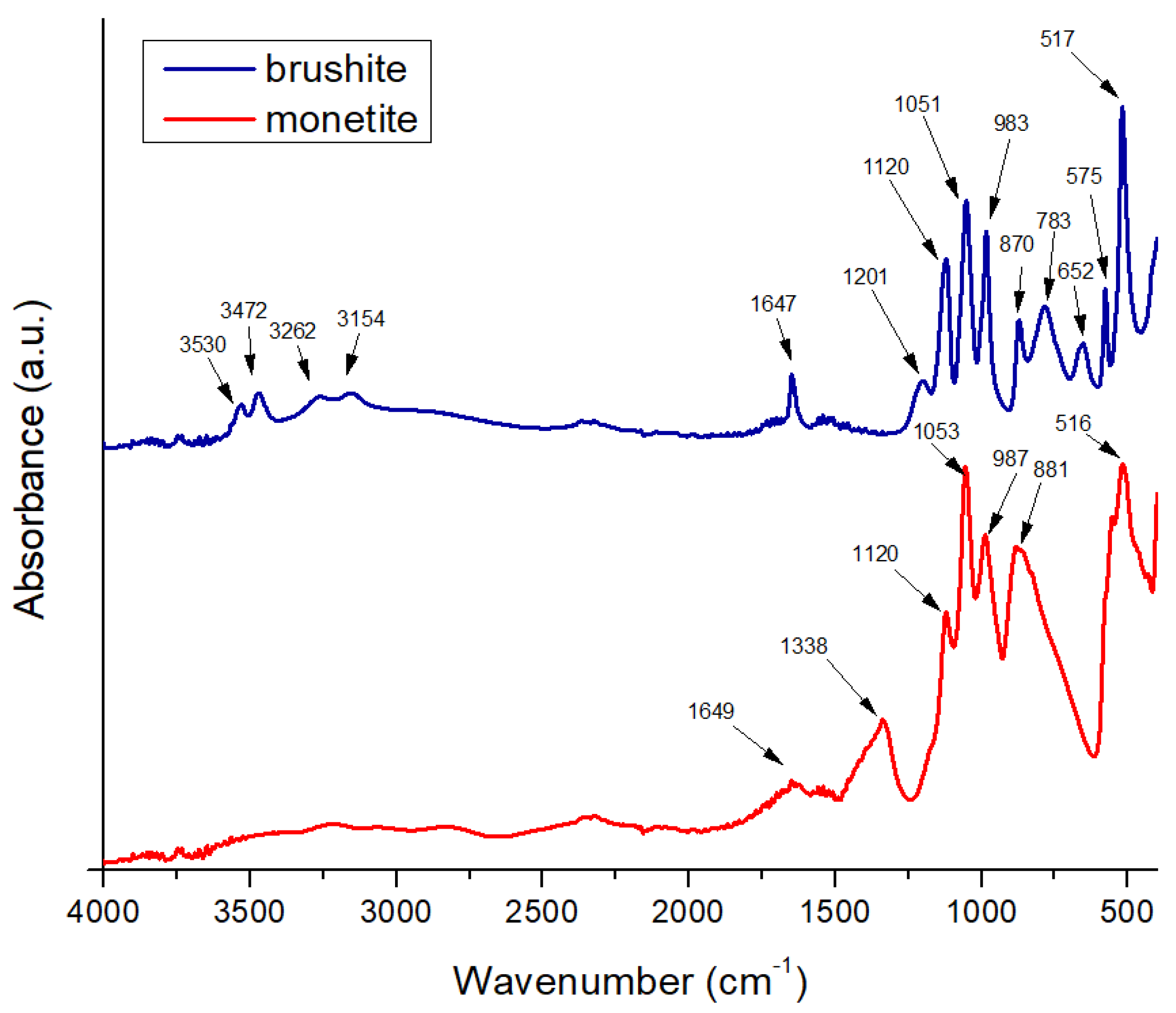

FTIR spectra of composite scaffolds based on gelatin, alginate, and CMC loaded with CaP (monetite, brushite) exhibit characteristic bands attributable to polymeric and mineral components, as shown in

Figure 11. In the 3600–3000 cm

−1 region, O–H and N–H stretching vibrations are observed, associated with gelatin, alginate, and CMC, as well as crystallization water in brushite. The 1750–1500 cm

−1 region contains bands corresponding to amide I and II from the proteinaceous gelatin, which become more pronounced with increasing gelatin content. Between 1616 and 1419 cm

−1, asymmetric and symmetric COO

− bands from alginate confirm polysaccharide integration, while CMC contributes C–O–C and C–O vibrations in the 1300–1000 cm

−1 range. The introduction of monetite and brushite generates additional bands specific to P–O bonds in the 1130–1030 cm

−1 region (P–O stretching vibrations) and fingerprint bands below 800 cm

−1 (associated with P–O–P and P–O(H) vibrations). Differences between monetite and brushite are reflected in the width and position of phosphate bands due to the presence of crystallization water in brushite and its distinct crystal structure.

2.2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy

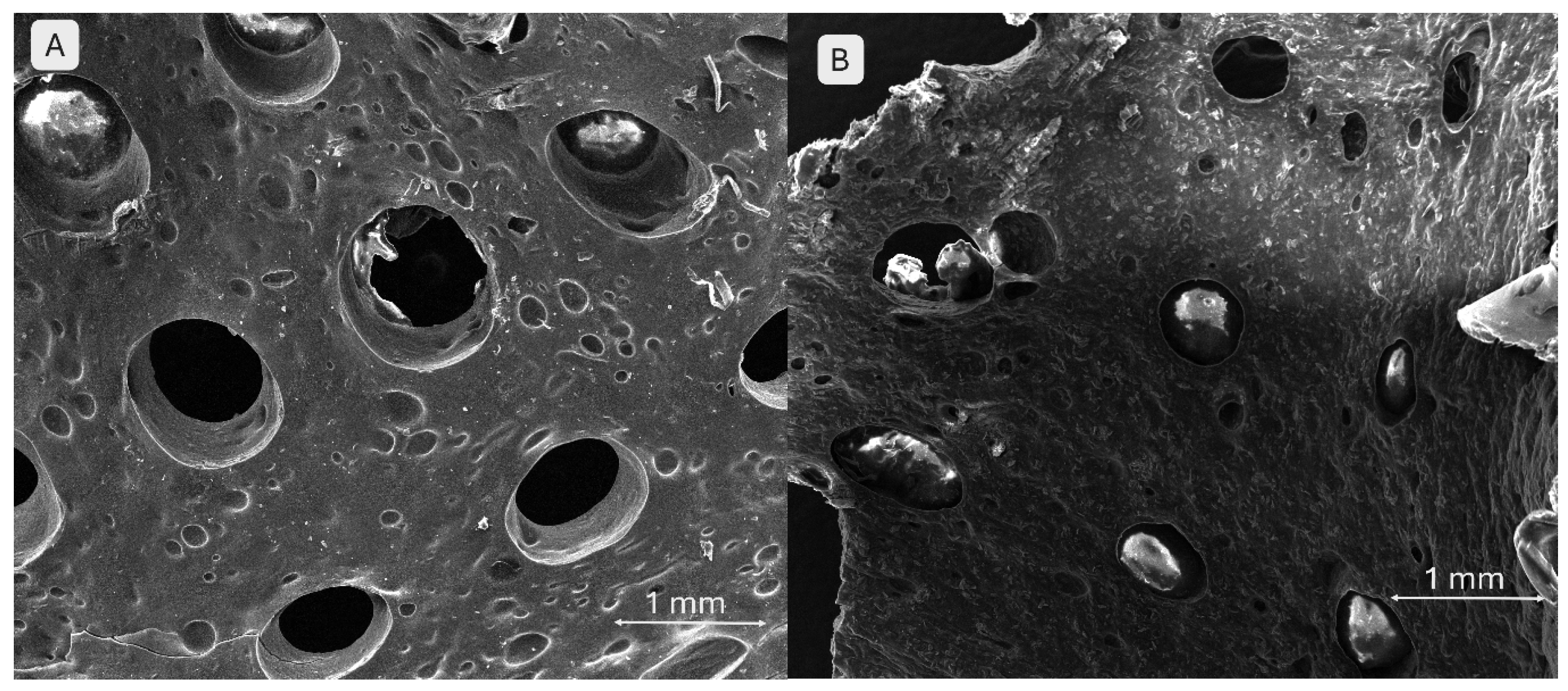

SEM images in

Figure 12 demonstrate well-defined filament and pore morphologies for polymeric compositions without phosphate additives. In image A (S1), thin walls, clearly delineated pore edges, and an aerated architecture with an open porous network are visible, suggesting good printability. Conversely, image B (S4) shows a more compact structure with thickened, slightly collapsed walls, indicating higher viscosity of the mixture and improved geometric fidelity.

The addition of monetite significantly affects scaffold architecture (

Figure 13). Image A (3 % monetite) shows well-defined pores with slightly irregular edges and a surface exhibiting fine but uneven mineral particle agglomerations, suggesting partial integration of monetite within the hydrogel matrix. Image B (5 % monetite) reveals a denser morphology with visibly reduced pore size. The pore edges appear deformed, likely due to increased mixture rigidity. The higher monetite content seems to enhance structural stability but at the expense of printing fidelity. Mineral particles are more prominent, potentially favouring scaffold osteoconductivity.

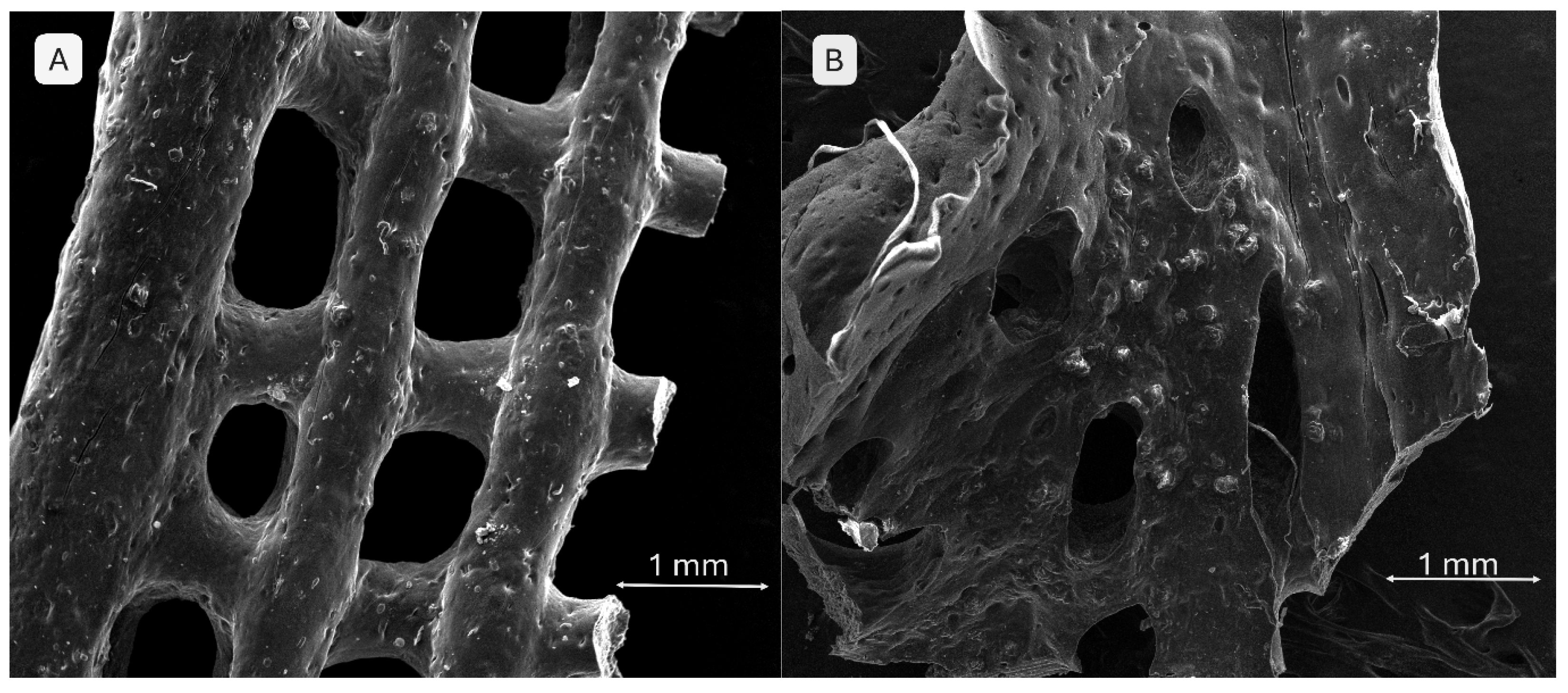

Brushite-containing scaffolds (

Figure 14) exhibit behaviour distinct from those containing monetite. In image A (3 % brushite), the network structure is well preserved, displaying a clear and relatively uniform porous architecture. The surface appears smoother, and brushite particles are less conspicuous at this concentration, suggesting a uniform distribution and weaker interaction with the polymer matrix. In image B (5 % brushite), an irregular morphology is observed, characterized by asymmetric pores and partial collapse of the structure in certain areas. The increased concentration of brushite appears to negatively affect structural fidelity and printing homogeneity. This composition exhibits apparently lower porosity and a more fragile structure, possibly due to weak interactions between the mineral phase and the polymer network.

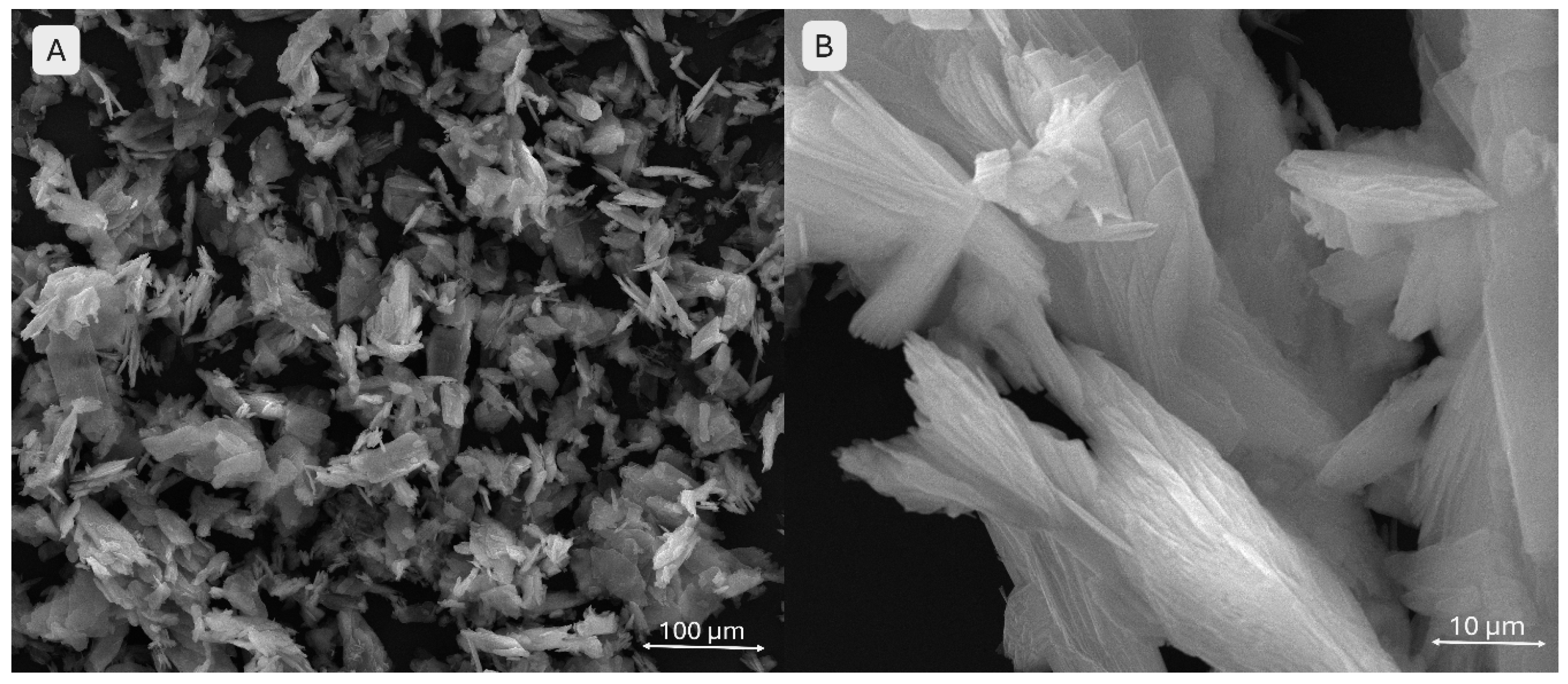

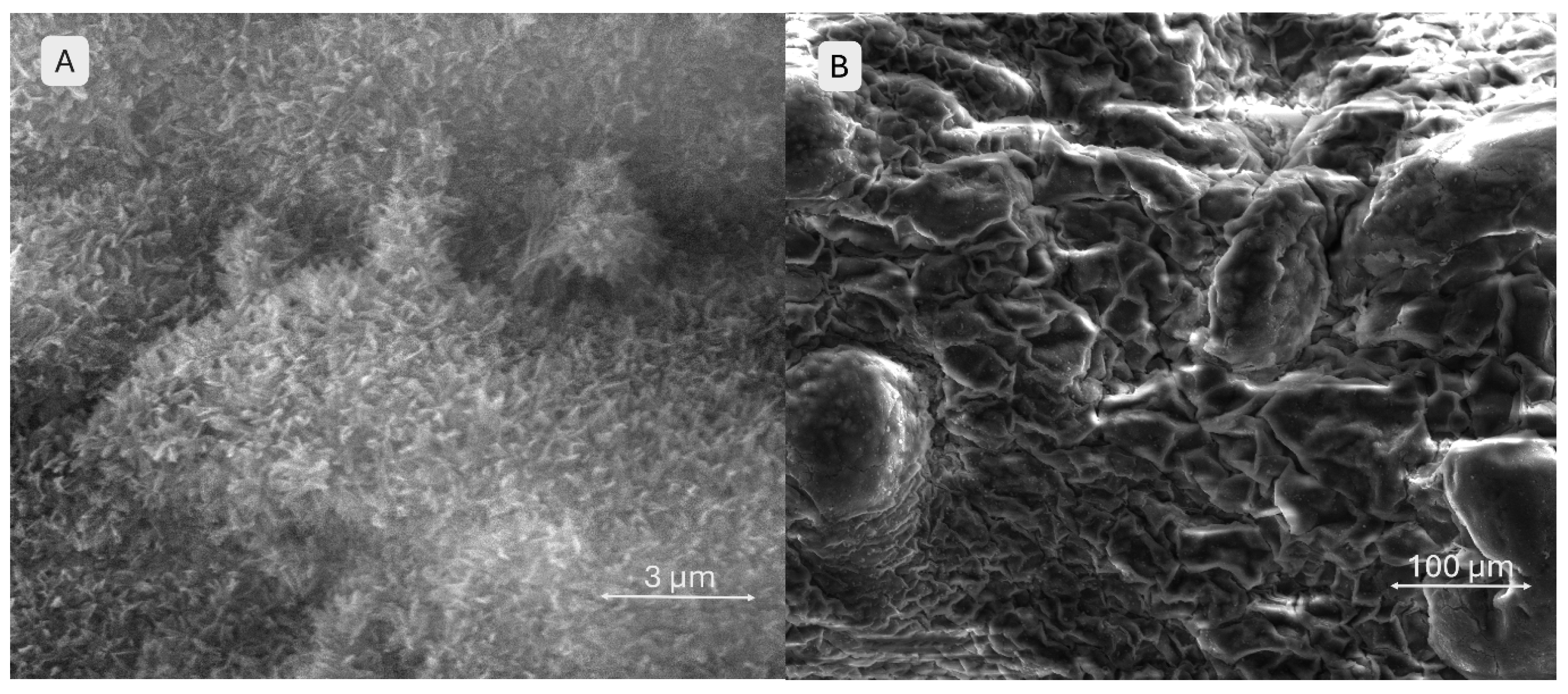

In

Figure 15, image A shows a surface characterized by numerous submicron filamentous protrusions, resembling a carpet of fine, grass-like fibres. This fibrillar texture indicates the predominance of the polymeric network (gelatin, alginate, CMC) and its interaction with the simulated body fluid (SBF) environment. Image B depicts the same scaffold at a larger scale, highlighting the clear contours of macroporous channels and pores. Since the material consists solely of alginate, gelatin, and CMC, the surface exhibits a slightly wavy texture with minor irregularities caused by polymer contraction and relaxation during drying, as well as interaction with SBF.

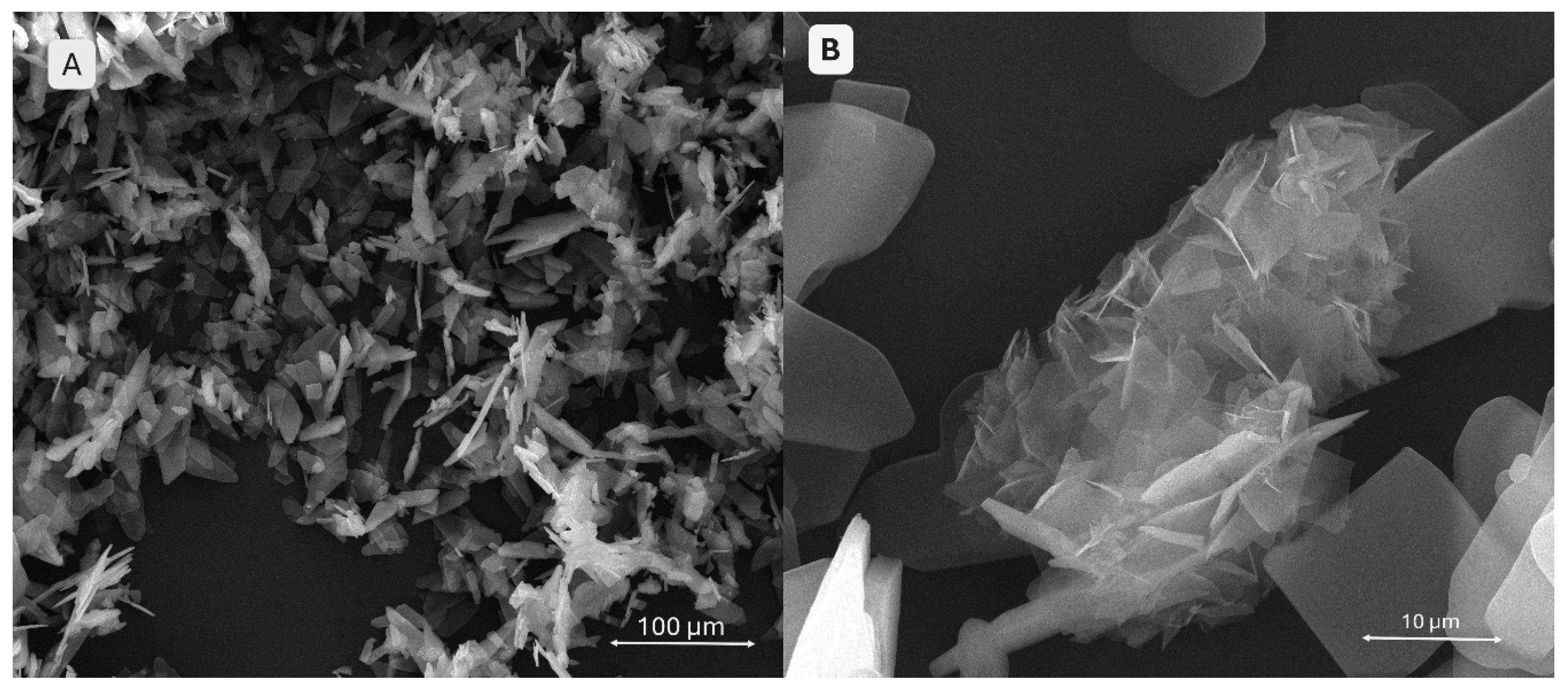

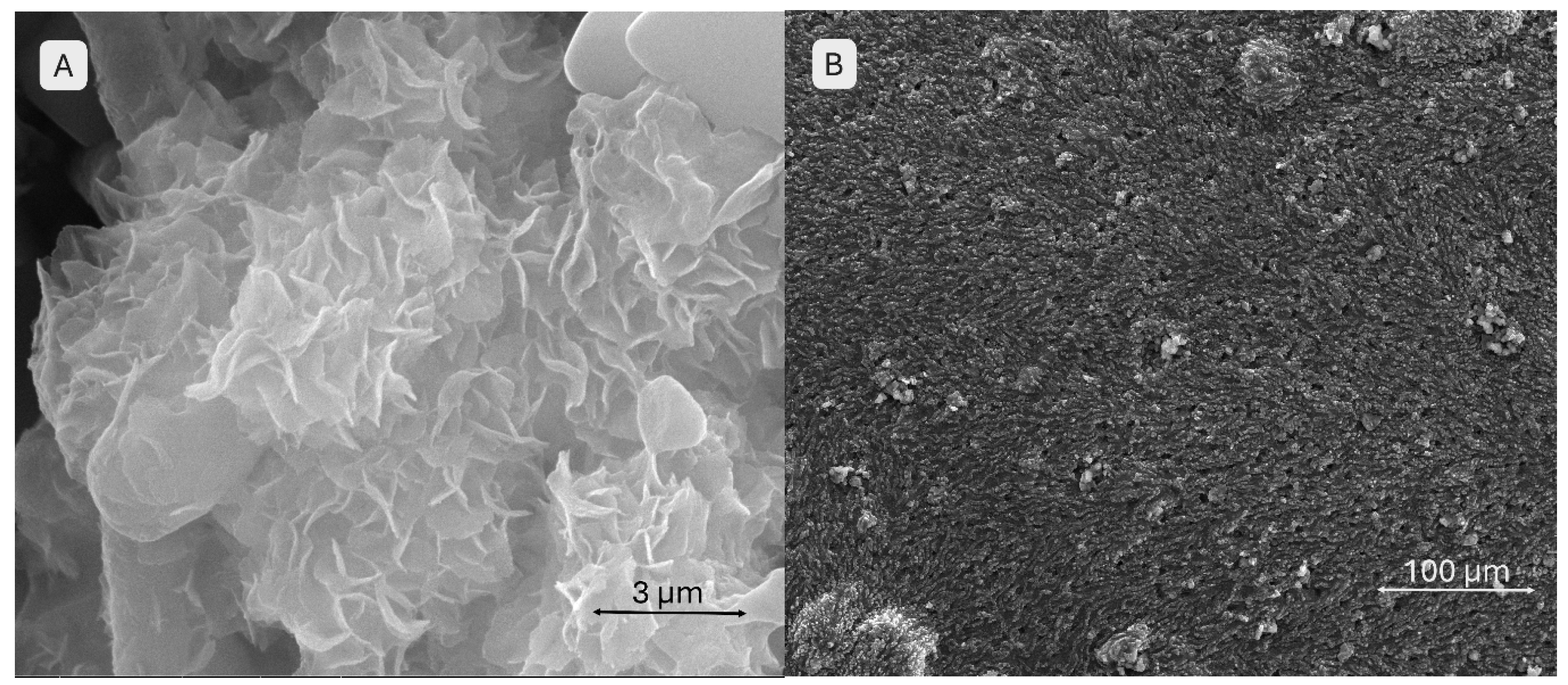

The SEM images (

Figure 16) provide a close-up view (image A) of the brushite-containing scaffold, where the surface appears as an assembly of thin, wavy, overlapping sheets resembling flower petals. This stratified and complex morphology suggests the presence and reactivity of mineral particles in contact with SBF, with brushite maintaining its initially fragmented structure. The high density of these sheets indicates enhanced bioactivity. Image B shows a surface densely covered by mineral particles arranged in a relatively ordered network, without obvious large pores. At this scale, aggregates overlap in an apparently organized manner. The particles appear uniformly distributed, forming a slightly irregular but consistent relief across the entire surface, suggesting homogeneous mineral deposition.

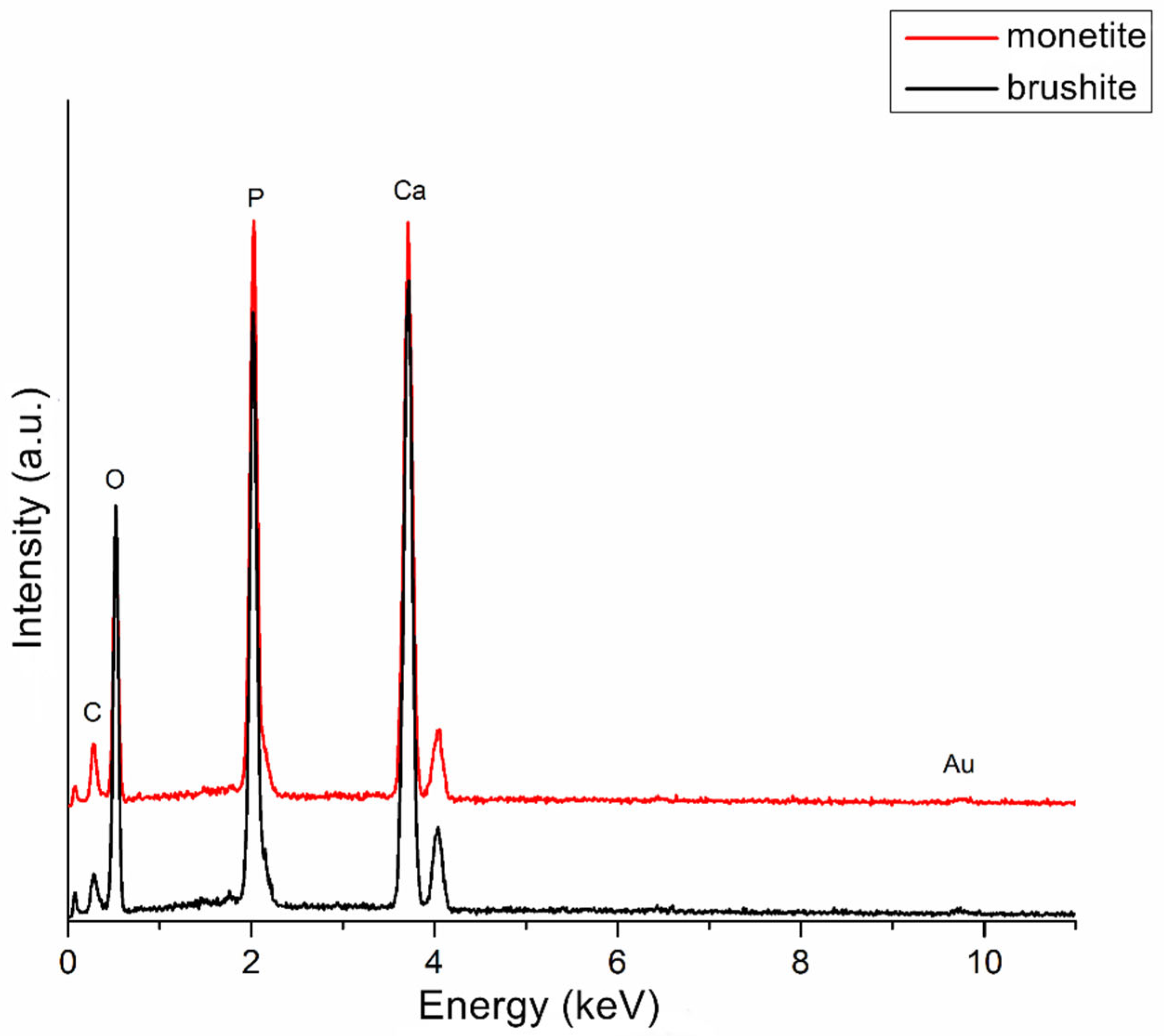

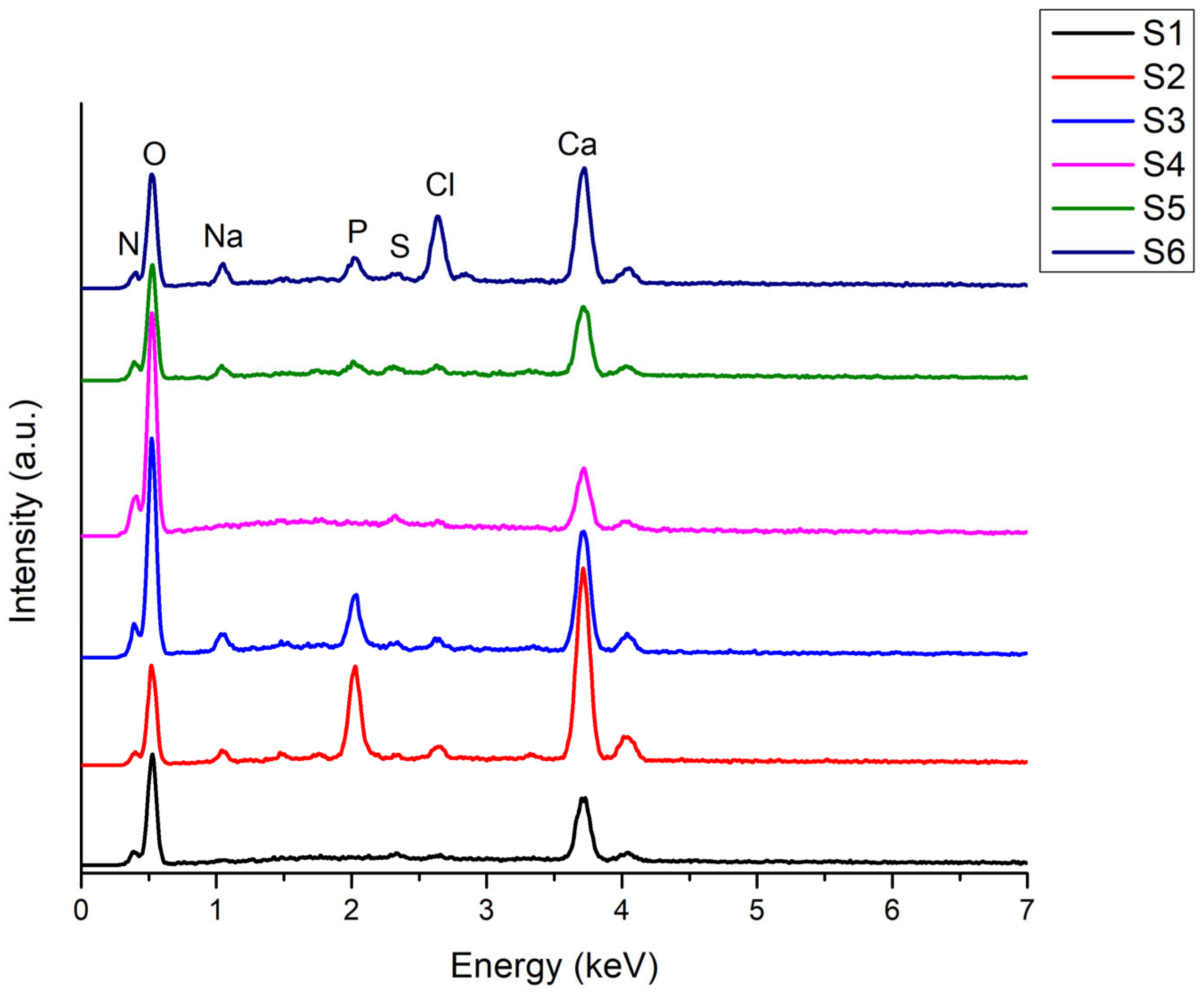

EDS analysis of the 3D-printed scaffolds (

Figure 17) reveals the presence of several elements: calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), sodium (Na), sulphur (S), and chlorine (Cl). The strong oxygen peak in all samples reflects the hydrogel composition (gelatin and alginate), both polymers containing oxygenated groups (hydroxyl, carbonyl). In mineral-containing samples, oxygen also originates from phosphate groups [PO

4]

3− and, in the case of brushite, from crystallization water. Nitrogen is specific to amidic bonds from gelatin, confirming its incorporation. The nitrogen signal intensity slightly increases in samples with 12 % gelatin (S4–S6) compared to those with 8 % gelatin (S1–S3), reflecting a higher proportion of amino groups. The phosphorus peak is absent in samples without calcium phosphate (S1, S4) and present in samples containing monetite and brushite, as expected. The intensity of the phosphorus signal correlates with the CaP content: samples with 5 % CaP (S2, S3) show stronger signals than those with 3 % CaP (S5, S6), confirming mineral phase incorporation. Chlorine appears in the spectra due to the use of the crosslinking solution, an aqueous CaCl

2 solution; Cl

− ions may remain in the network after gelation and incomplete washing. The intensity of the chlorine signal can be higher immediately after crosslinking and decrease after multiple washing steps. Comparing samples, a weak chlorine signal suggests efficient washing, while a stronger signal may indicate retention of Cl

− ions within the gel structure. The calcium peak confirms the presence of the CaP phase in samples S2, S3 and S5, S6. Its intensity reflects the CaP percentage: S2 and S3 (5 % CaP) exhibit higher intensity, while S5 and S6 (3 % CaP) show lower intensity. In samples without CaP (S1, S4), calcium originates from CaCl

2 crosslinking. The sodium peak derives from sodium alginate used in the hydrogel composition.

2.2.6. Printing Accuracy

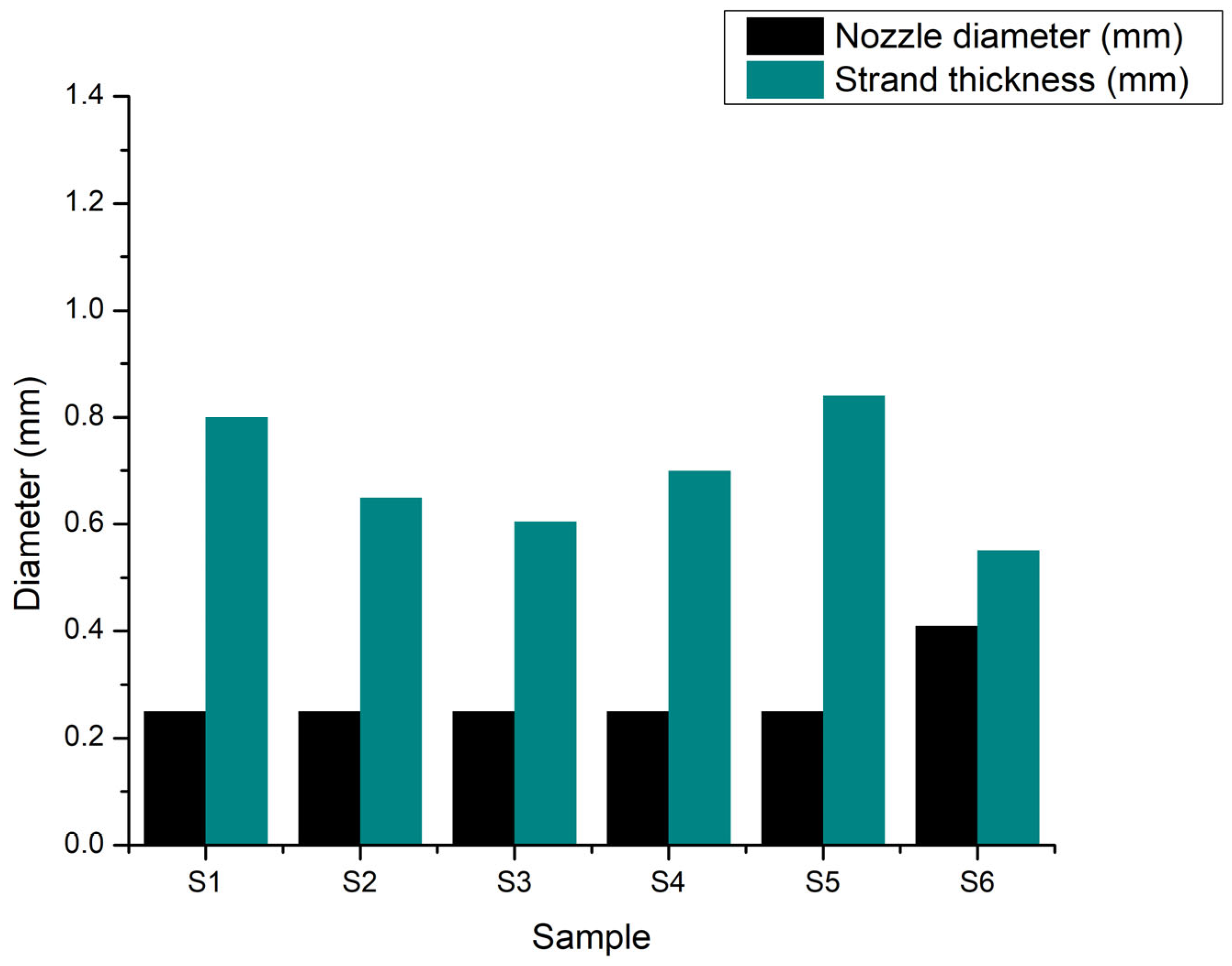

To highlight how composition influences the geometric characteristics of the extruded filaments, the comparison of filament diameters presented in

Figure 18 provides valuable insights into the role of each component. Filaments produced by samples S1 (8 % gelatin, 7 % alginate, 1 % CMC) and S2 (8 % gelatin, 7 % alginate, 1 % CMC, 5 % monetite) exhibited similar diameters around 0.80–0.85 mm, indicating that the addition of monetite did not significantly alter the non-Newtonian behaviour of the base hydrogel. In contrast, sample S3 (8 % gelatin, 7 % alginate, 1 % CMC, 5 % brushite) showed a slightly reduced expansion, with filament diameters close to 0.70 mm, suggesting that brushite, due to its distinct crystalline structure, imparts additional rigidity to the network, limiting radial swelling.

Turning to samples with increased gelatin content (12 %), S4 (12 % gelatin, 5 % alginate, 1 % CMC) produced filaments approximately 0.75 mm in diameter, indicating that a higher gelatin proportion promotes increased viscosity and slightly reduces filament expansion. The addition of monetite in S5 (12 % gelatin, 5 % alginate, 1 % CMC, 3 % monetite) resulted in an average filament diameter of about 0.85 mm, similar to S1 and S2, demonstrating that moderate monetite content does not counteract gelatin effect on filament swelling. Conversely, sample S6 (12 % gelatin, 5 % alginate, 1 % CMC, 3 % brushite), printed with a 22G nozzle, exhibited a filament diameter of approximately 0.55 mm; this outcome reflects both the influence of the larger nozzle and the more pronounced stiffening effect of brushite.

Overall, these comparisons reveal two distinct trends: the gelatin content and presence of CMC significantly increase filament swelling by raising hydrogel viscosity, while the type and concentration of calcium phosphate (monetite versus brushite) influence network rigidity, with monetite exerting a milder effect on swelling compared to brushite.

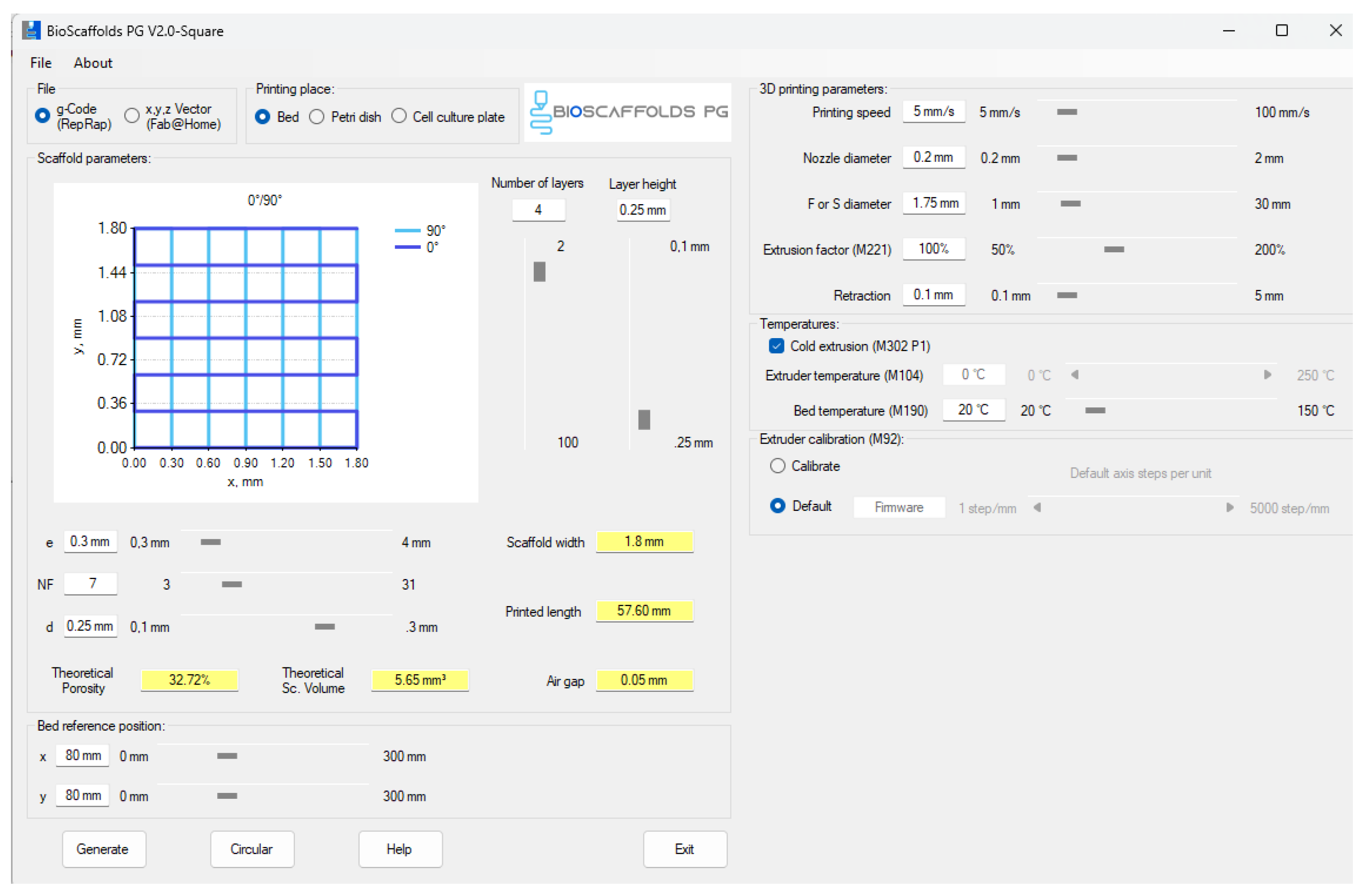

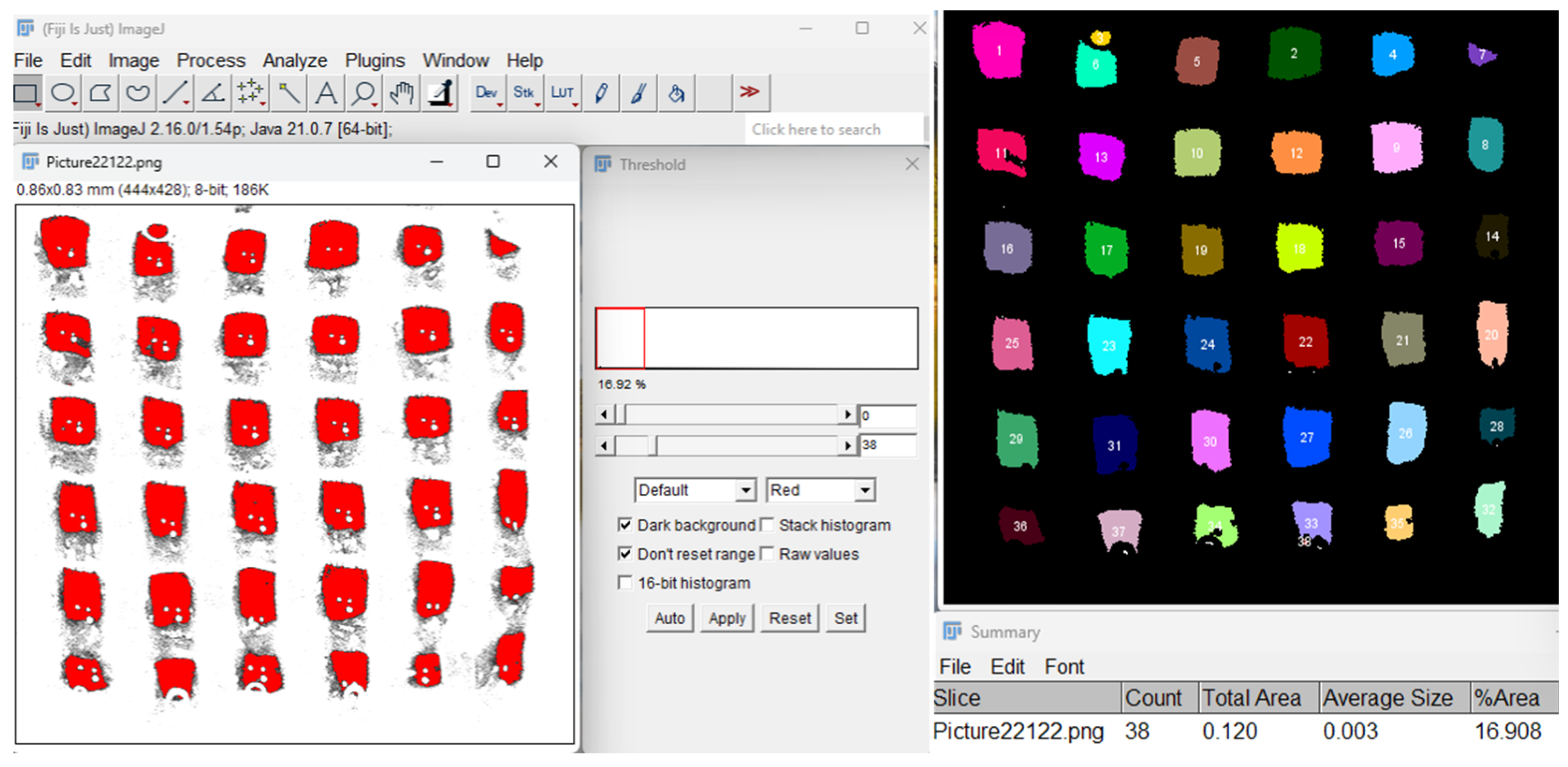

2.2.7. Porosity Evaluation

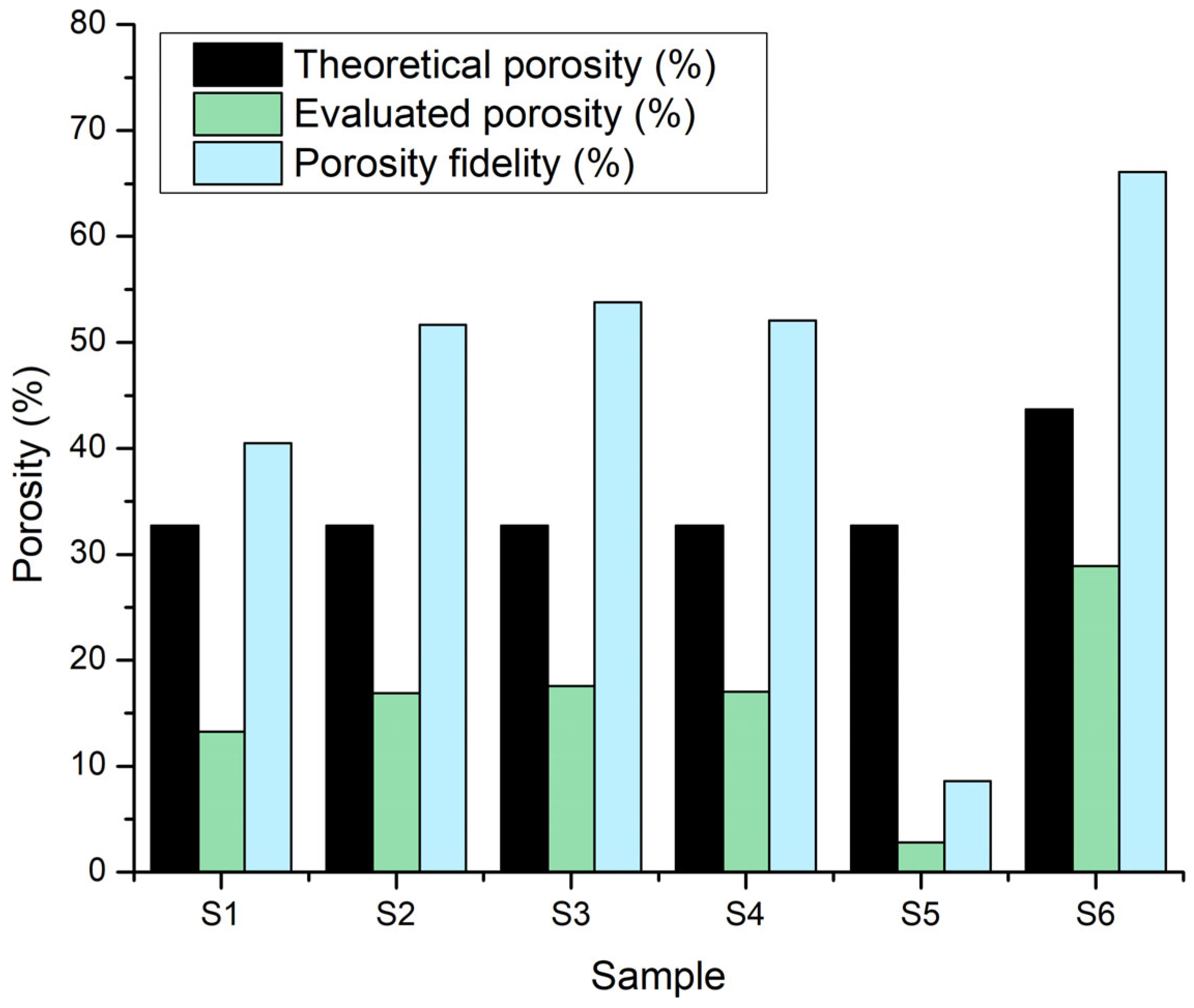

The comparative graph of theoretical porosity (calculated using the BioScaffolds V2 application based on printing parameters and designed geometry) and experimentally measured porosity (

Figure 19) reveals how the actual behaviour of hydrogels and hydrogel–CaP composites affects scaffold architecture. The theoretical porosity remains constant at approximately ~ 32 % for samples S1–S5 and increases to about 43 % for sample S6, due to the use of a larger diameter printing nozzle for this sample. However, the experimentally measured porosity is significantly lower for all samples, indicating partial blockage of inter-filament spaces and layer fusion resulting from filament swelling and hydrogel–CaP interactions.

Specifically, for sample S1, the experimental evaluation indicated approximately 13 %, due to the non-Newtonian behaviour of the hydrogel, which causes increased filament swelling during printing and subsequent layer fusion, thus reducing the designed pore spaces. For samples S2 and S3, containing 5 % monetite and 5 % brushite respectively, the evaluated porosity was reduced to about 17–18 %. The addition of the mineral phase stiffens the network and moderates some swelling effects, but sufficient filament expansion remains to significantly reduce the projected porosity.

Sample S4, without CaP and with a higher gelatin proportion, exhibited measured porosity in the same range (~17 %), due to the higher polymer network density, conferred by the increased gelatin content. In contrast, sample S5, containing 3 % monetite and a high gelatin proportion, recorded the lowest measured porosity (~2–3 %), indicating nearly complete layer fusion, likely due to the combined influence of gelatin-associated filament swelling and the reinforcing effect of monetite particles creating a dense network. For sample S6, which has the same CaP percentage as S5 (3 %) but with brushite and printing performed with a larger nozzle, the experimental determined porosity was 28% compared to the theoretic value of 43%.

Porosity fidelity, defined as a percentage of the ratio between evaluated and theoretical porosity, highlights these discrepancies quantitatively. Across all samples, porosity fidelity values were well below 100%, confirming that significant pore occlusion and morphological deviations occur during and after printing. S6 exhibited the highest porosity fidelity (~66%), indicating that its printing strategy most closely preserved the originally designed architecture. In contrast, S5 had the lowest porosity fidelity (under 9%), revealing extensive pore loss. The moderate fidelity of S1–S4 (around 40–53%) reflects the persistent challenge of maintaining open, interconnected porosity, especially in softer or highly swelling hydrogel systems.

2.2.8. Swelling Degree

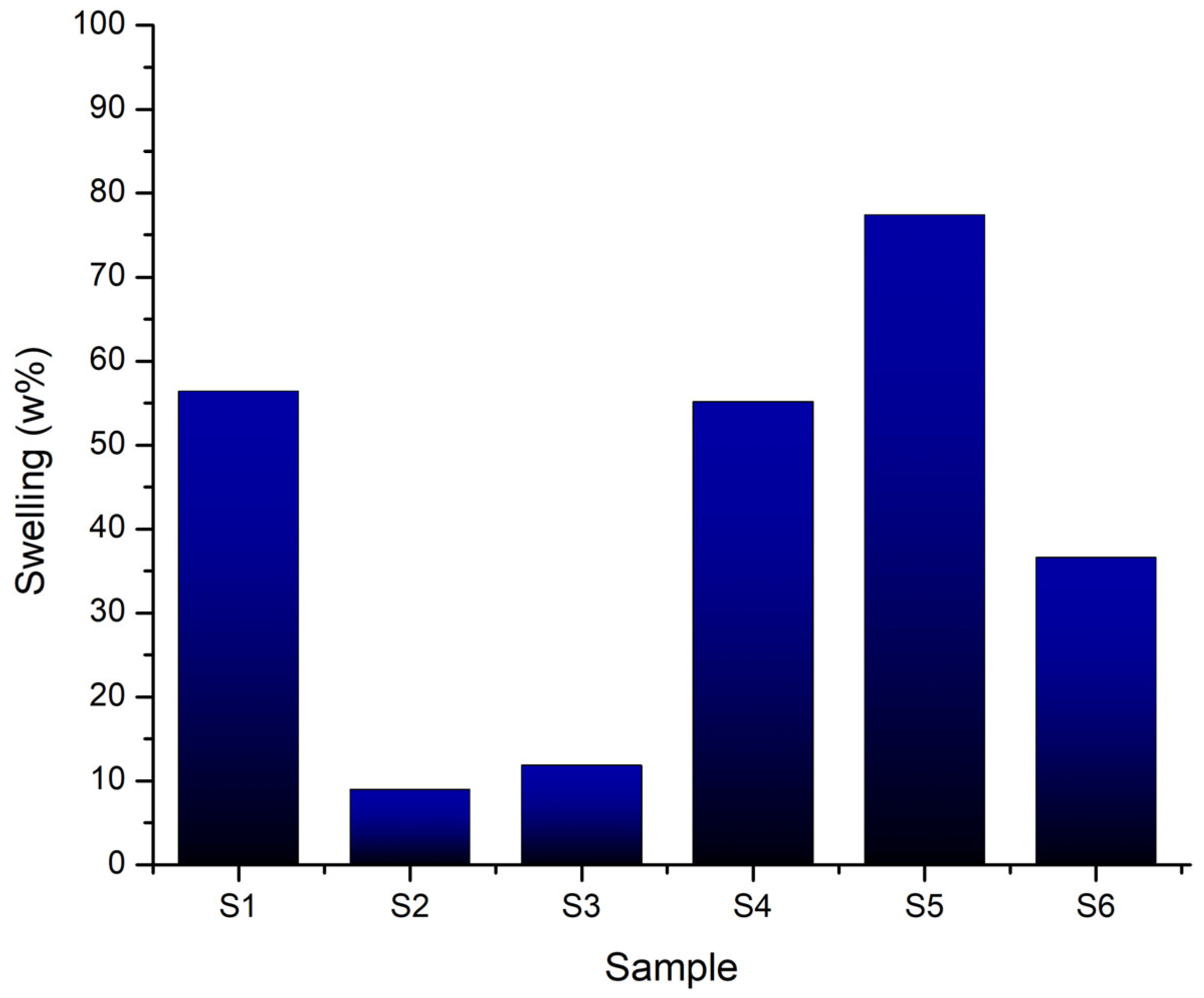

The swelling rate, expressed as a percentage, reflects each sample capacity to absorb and retain fluid. The graph in

Figure 20 clearly illustrates the influence of each component on the final volume. In the absence of the mineral phase, sample S1 (8 % gelatin, 7 % alginate, 1 % CMC) exhibits a high swelling rate of approximately 56 %, indicating an open, flexible polymer network capable of expanding intermolecular spaces to absorb fluid rapidly.

In contrast, the introduction of CaP significantly alters this behaviour: S2 (with 5 % monetite) shows a low rate (~ 9 %) due to network rigidification, while S3 (5 % brushite) has a slightly higher swelling (~ 12 %), reflecting different polymer-mineral interactions.

In formulations with increased gelatin (12 %) and lower alginate (5 %), these trends are more pronounced. S4 swells about 50%, slightly less than S1, due to a denser polymer network. Interestingly, S5 (3 % monetite) shows a high swelling rate (~ 75 %), suggesting that moderate mineral content combined with higher gelatin concentration allows considerable expansion before rigidity limits swelling. S6 swells to ~ 36 %, indicating that even at 3 %, brushite imposes a much stronger constraint on network expansion compared to monetite, reflecting how the nature of the phosphate influences hydrophilic properties.

Overall, swelling behavior depends on both mineral type and content, as well as polymer composition. Scaffolds without mineral or with low monetite in gelatin-rich matrices are suited for applications needing high expansion, whereas those with brushite or higher mineral content provide dimensional stability by limiting swelling.

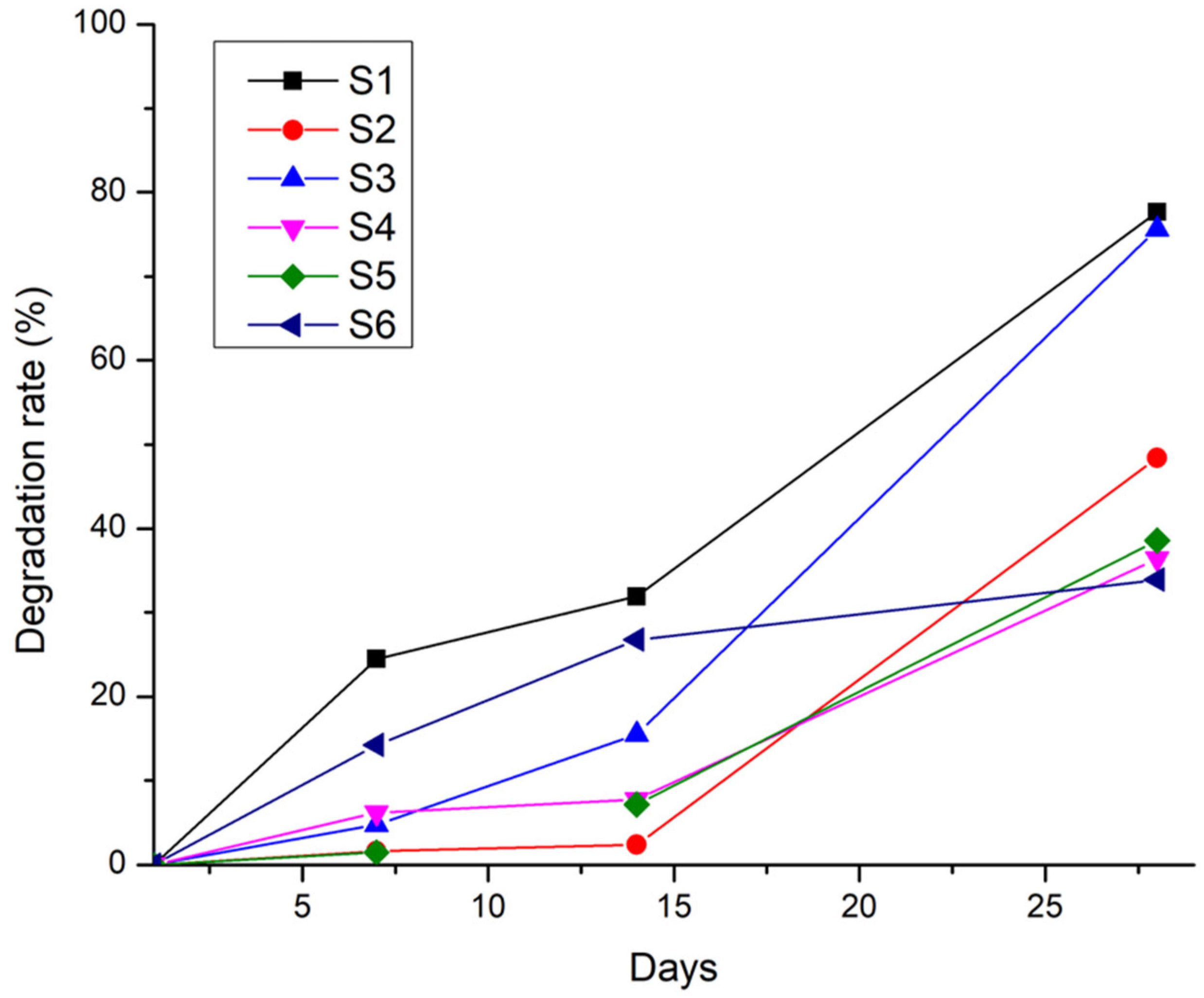

2.2.9. Degradation Rate

Degradation tests performed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37 °C over 28 days demonstrated that the scaffold stability is strongly influenced by the interplay between the polymeric and inorganic phases. The hydrogel-only sample S1 (8 % gelatin, 7 % alginate, 1 % CMC) exhibited rapid degradation, losing more than 50 % of its initial mass within the first week and surpassing 90 % mass loss by day 28. In contrast, sample S4 (12 % gelatin, 5 % alginate, 1 % CMC) showed a more gradual degradation profile, with approximately 30 % mass loss in the first 7 days and around 80 % by day 28, resulting from the higher gelatin content.

Monetite-containing samples (S2 and S5) degraded more slowly, losing only 15–20% mass in the first week and about 60% by day 28, likely due to monetite reinforcing the composite network. Brushite-containing samples (S3 and S6) exhibited intermediate degradation, with ~40% mass loss in the first week and ~80% by day 28. Despite brushite’s higher solubility, its interaction with gelatin and alginate appears to accelerate degradation after two weeks.

The degradation profile illustrated in

Figure 21 highlights that the presence of the mineral phase delays the onset of rapid degradation, while the specific type of CaP modulates the long-term resorption rate of the scaffolds.

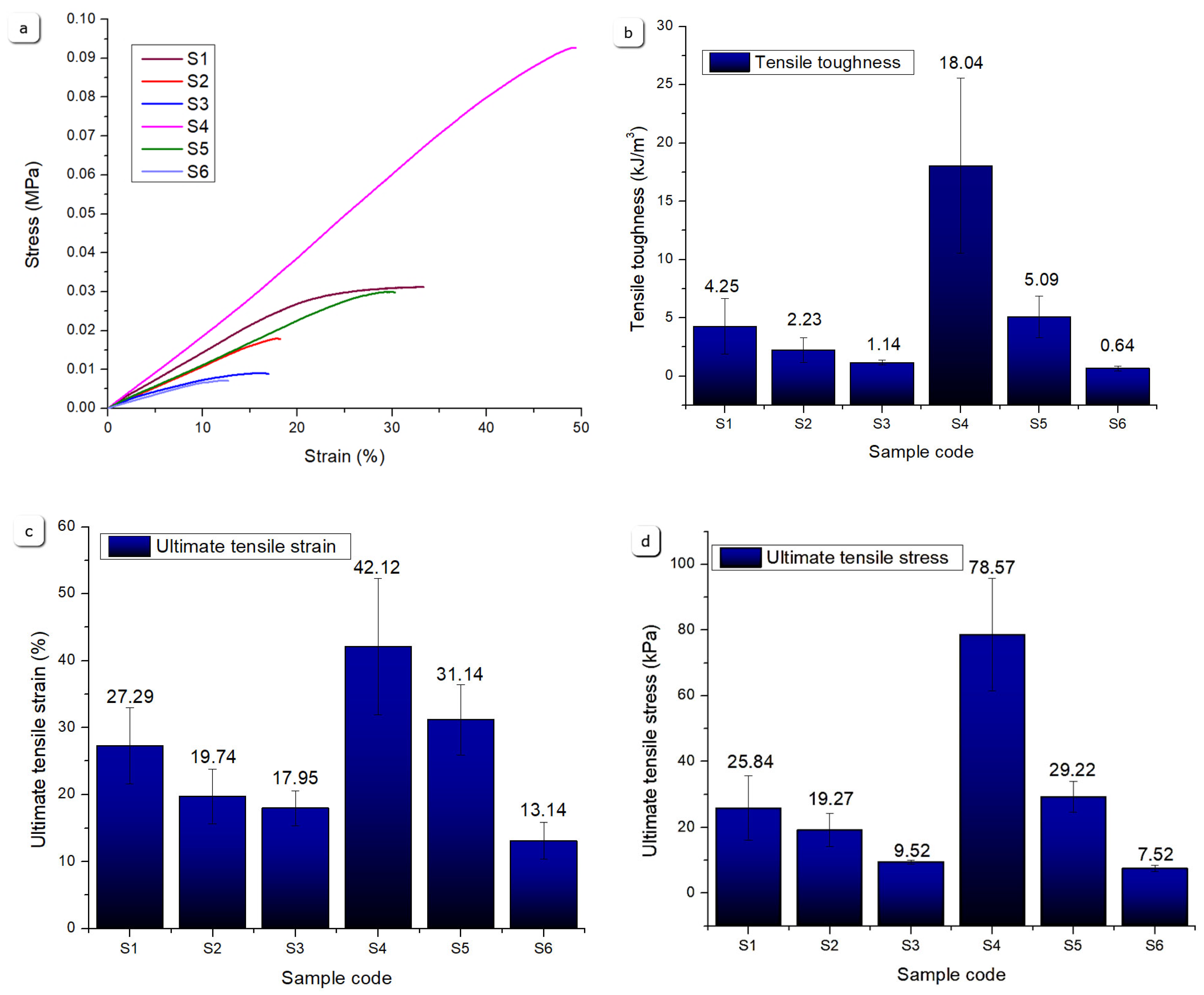

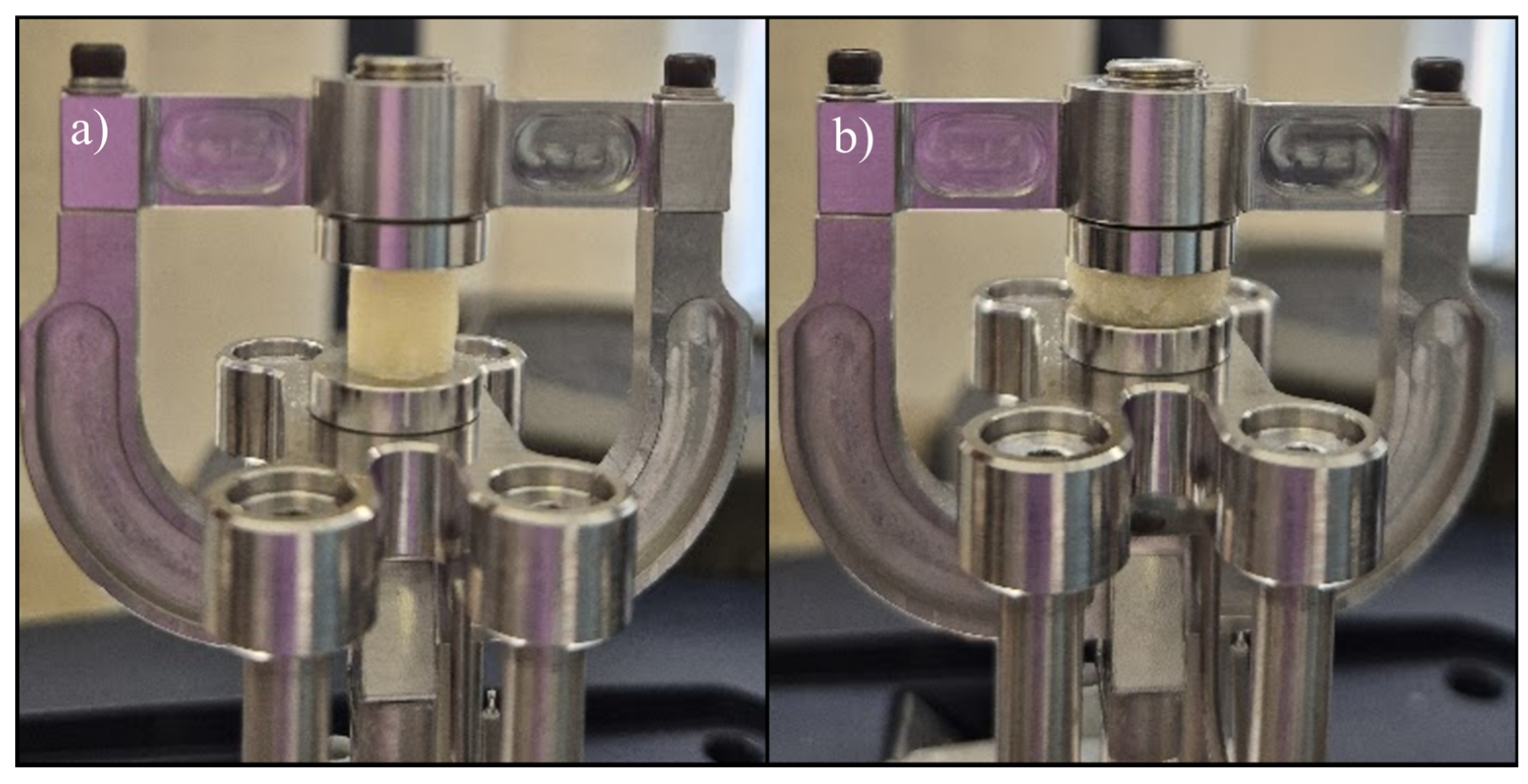

2.2.10. Mechanical Properties

Figure 22 presents a comparative analysis of the uniaxial tensile test results, providing a structured framework for evaluating the mechanical properties of the printed scaffolds under tensile stress. The stress-strain comparisons highlight that Sample S4 exhibits superior mechanical performance, achieving the highest ultimate tensile stress among all tested specimens. This enhanced performance can be attributed to its composition containing 12% gelatin, 5% alginate, and 1% CMC without mineral reinforcement, resulting in a denser polymer network with strong intermolecular interactions and increased crosslink density. The higher gelatin concentration contributes to improved elasticity and tensile strength by providing a more cohesive matrix capable of sustaining greater deformation and load.

Based on the tensile test results, Sample S4 demonstrates the most favorable mechanical characteristics, consistently surpassing other samples in terms of stress-strain response. Its high tensile toughness suggests an improved capacity for energy absorption under tensile loading, indicative of a well-balanced polymeric structure.

Samples S5 and S1 also exhibit notable mechanical resilience, showing comparable tensile toughness values. Sample S5 contains 12 % gelatin, 5 % alginate, 1 % CMC, and 3 % monetite, where the incorporation of monetite particles reinforces the polymer matrix and restricts excessive deformation. This composite effect enhances strength but slightly reduces elasticity compared to S4. Sample S1, a hydrogel-only formulation (8 % gelatin, 7 % alginate, 1% CMC), has a more flexible but less dense polymer network, affording reasonable tensile toughness but limited ultimate stress compared to S4, due to a lower crosslink density and absence of reinforcing minerals.

In contrast, Samples S2, S3, and S6 show inferior performance across tensile parameters. Sample S2 (8 % gelatin, 7 % alginate, 1 % CMC, 5 % monetite) and S3 (8 % gelatin, 7 % alginate, 1% CMC, 5% brushite) contain higher mineral content but lower gelatin concentration, resulting in a stiffer yet more brittle matrix prone to fracture under tensile stress. Sample S6 (12 % gelatin, 5 % alginate, 1 % CMC, 3 % brushite), despite higher gelatin, incorporates brushite which interacts differently with the polymer matrix, likely creating localized stress concentrations that reduce tensile toughness and strain capacity. The lower ultimate tensile strain and stress observed in Sample S6 reflect reduced structural integrity and mechanical robustness.

Overall, the tensile test results designate Sample S4 as the most mechanically robust under tensile loads, followed by the polymer-mineral composite S5, while mineral-rich samples with either low gelatin or brushite exhibit diminished tensile resistance, due to the increased porosity generated by the incorporation of air bubbles in the preparation stage. These findings underscore the role of polymer composition—particularly gelatin content—and mineral phase type and concentration in tuning tensile performance.

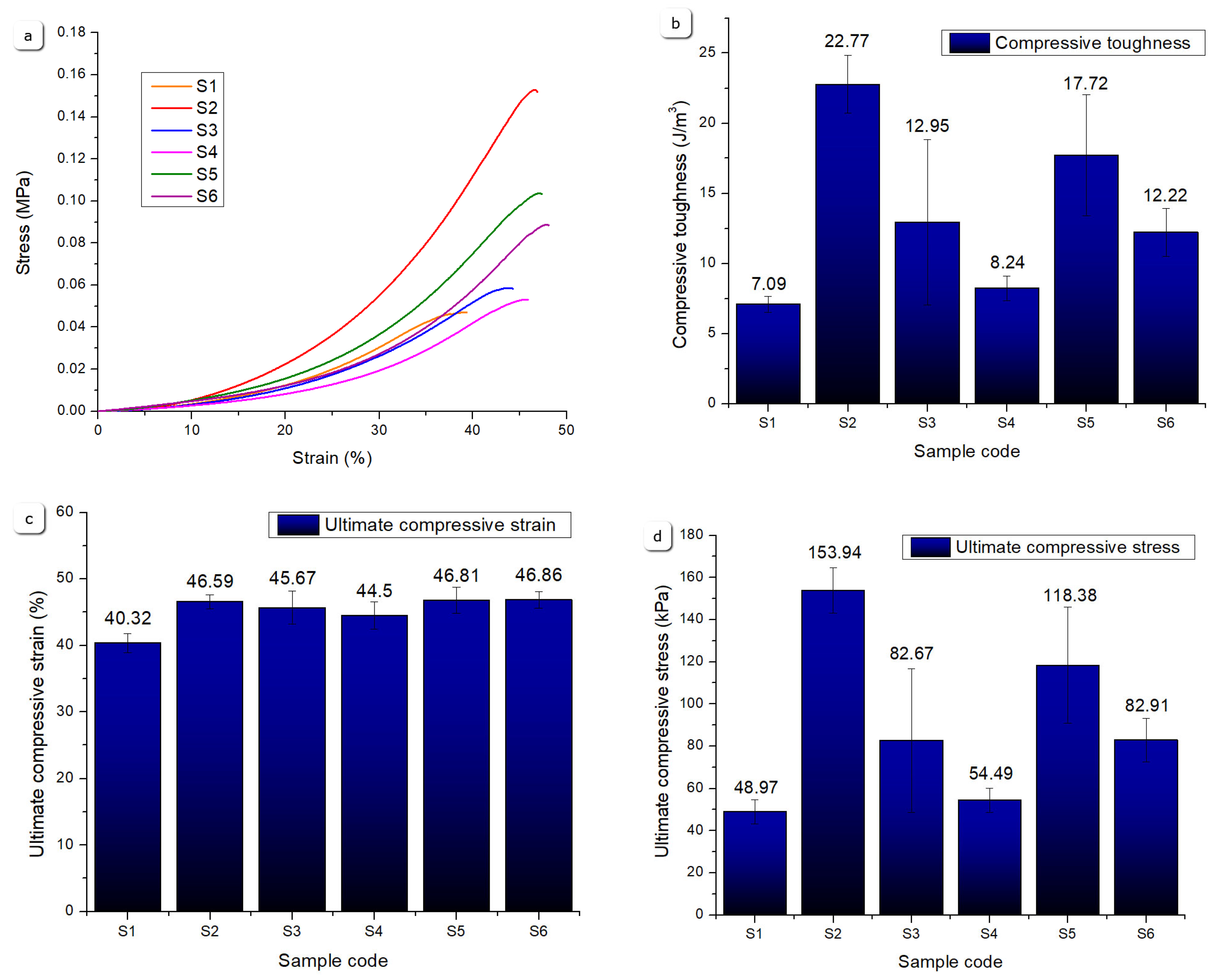

Figure 23 summarizes compression test results, revealing notable variations in mechanical resistance under compressive loading. Sample S2 demonstrates the highest compressive robustness, exhibiting superior compressive toughness and ultimate compressive stress at ~45 % strain. This enhanced behavior arises from its composite formulation of 8 % gelatin, 7 % alginate, 1 % CMC, and 5 % monetite, where monetite acts as a reinforcing agent, stiffening the network and improving load-bearing capacity. The moderate gelatin content allows a balance between flexibility and strength under compression.

Sample S5 also shows strong compressive performance, benefiting from higher gelatin content (12 %) combined with 3 % monetite. The greater gelatin concentration contributes to polymer network density enhancing elasticity, while monetite maintains reinforcement, yielding high compressive toughness and stress values.

Sample S6, with 3 % brushite and the same polymer base as S5, displays lower ultimate compressive stress, possibly due to brushite’s different interaction with the polymer matrix leading to reduced stiffness and earlier failure under compression.

Samples S1, S3, and S4 exhibit lower compressive resistance. Sample S1, without mineral addition and with lower gelatin content, shows the lowest ultimate compressive stress and toughness, reflecting a looser polymer network vulnerable to deformation. Sample S3, despite mineral content, has low gelatin and includes brushite, resulting in a comparatively brittle structure. Sample S4, while outstanding in tensile metrics, shows reduced compressive resistance, likely due to its polymer-only nature and higher elasticity which allows more deformation under compressive loads. These differences highlight how variations in polymer content and mineral phase type govern compressive mechanics, enabling tailored scaffold design depending on loading requirements, and are consistent with literature data [

39].

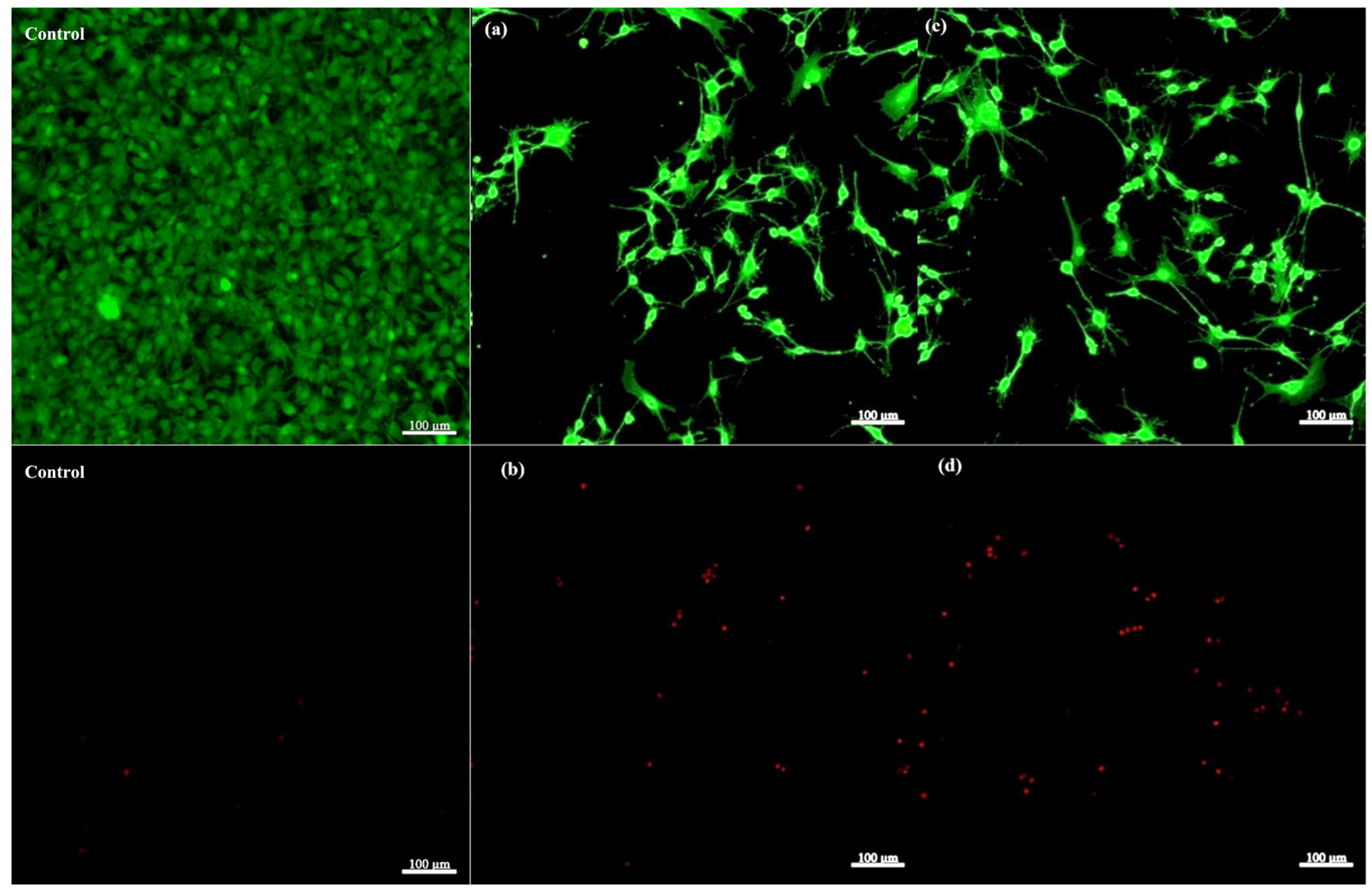

2.2.11. LIVE/DEAD Viability Assay

Figure 24 shows results from the LIVE/DEAD fluorescence microscopy assay used to assess the viability of osteoblasts cultured on a 2D control flask substrate and the composite scaffold S5, which was selected due to its promising mechanical performance and favorable degradation, stability, and swelling profiles identified in preliminary evaluations, making it a representative candidate for biocompatibility assessment. Two different regions from the same scaffold sample were imaged to capture spatial variability, accounting for potential heterogeneity in cell distribution. Additionally, z-stacking was employed to visualize the three-dimensional arrangement of cells within the scaffold, allowing evaluation of viability both on the surface and deeper within the material.

Notably, the control group exhibited a higher density of clustered cells compared to the scaffold. This is primarily due to the 2D nature of the control substrate, where all cells grow as a monolayer confined to the same focal plane. In contrast, the three-dimensional topography and porous architecture of the scaffold support cell distribution throughout its volume, resulting in less apparent clustering in any single image plane. Moreover, the scaffold 3D structure promotes cellular extension and network formation—features absent in the 2D control group, where the osteoblasts lacked extended adhesion or cellular processes. This limited spreading and network formation is a known disadvantage of 2D culture systems, which fail to replicate the complex three-dimensional microenvironment. Furthermore, a small number of dead cells were observed in the 2D control group, where the rigid, flat surface could limit nutrient diffusion and alter adhesion dynamics compared to the scaffold, contributing to localized cell death.

In the calcein AM channel images (

Figure 24. a, c), there is a high density of green fluorescent cells, indicating a predominantly viable osteoblast population on the scaffold, where the cells exhibit a well-spread morphology with extended processes, characteristic of healthy adherent osteoblasts on a supportive substrate, with cell-binding properties that may be enhanced through surface engineering.

Images (b, d) illustrate a small number of red fluorescent cells, suggesting a low proportion of non-viable (dead) osteoblasts, with one possible explanation for this cell death being represented by the insufficient removal of residual glutaraldehyde following the crosslinking step. Glutaraldehyde is known for its cytotoxicity, and inadequate washing after crosslinking can result in residual amounts within the scaffold, negatively affecting cell viability [

40].

Overall, the LIVE/DEAD assay demonstrates that the composite scaffold supports good osteoblast viability, with a large proportion of cells alive and morphologically healthy, and minimal cell death observed across the tested surfaces suggesting the scaffold has favourable cytocompatibility, making it suitable for bone tissue engineering applications.