1. Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most common adult leukemia in the world, is an oncohematological disease characterized by the abnormal accumulation and proliferation of a large number of small mature CD19+CD5+CD23+ B lymphocytes. Leukaemic B cells proliferate in the proliferative centres of the bone marrow and lymph nodes, and accumulate due to blocked apoptotic pathways [

1]. The accumulation of leukaemic cells results in reduced cellular and humoral immune responses and increased susceptibility to infections. These complications are further exacerbated by hypogammaglobulinemia, abnormalities in T cell subsets, defects in complement activity, neutropenia, an increased number of immunosuppressive monocytes, and microenvironment that promote CLL cell survival through direct cell−cell interactions and secreted factors. [

2]. Immunosuppression caused by the disease itself is aggravated by the treatment. The effects of cancer chemotherapy include bone marrow suppression resulting in neutropenia, mucosal barrier disruption, and suppressive effects on T cells and B cells. As a consequence, CLL patients suffer from various infectious diseases, which are the most common cause of death [

3].Modern targeted molecular therapies, have expanded the list of pathogens causing infection.

Infections in CLL patients are frequently caused by viruses, fungi, or bacteria. These infections can be monomicrobial, involving a single organism, or polymicrobial, involving multiple microbes. Common bacterial agents include

Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, etc. Some reports showed sporadical cases of

Candida and

Aspergillus infections, which may be related to therapies resulting in more prolonged periods of neutropenia, in patients with advanced disease [

4]. To the best of our knowledge there are no publications to date from Georgia specifically addressing the colonizing microbiota of patients with CLL.

Given the association between infection-related complications and increased mortality in CLL patients, there is significant interest in investigation of the microbes responsible for these infections. Research efforts focus on both the identification and characterization of pathogens, as well as the development of effective treatment strategies and preventive measures [

5]. Antibiotic therapy remains a primary treatment for bacterial infections in CLL patients. However, the growing global issue of antibiotic resistance complicates the selection of effective treatments. While the literature frequently reports data on the antibiotic susceptibility of infectious agents isolated from CLL patients [

6], there is limited practical data on the effectiveness of alternative antimicrobial means against these agents.

Phage therapy (PT) is a broadly applicable antimicrobial strategy with a high potential in the treatment of bacterial infections. Bacteriophages exist in all environments where bacteria thrive, including soil, water, food, and sewage. They are part of the microbiome network in humans and animals, being present in feces, urine, saliva, and serum. They are responsible for 10–80% of total bacterial mortality and play a crucial role in regulating bacterial populations in natural environments [

7]. Phages may also contribute to the organism's natural defenses against harmful bacteria. Some phages possess enzymes capable of degrading biofilms, the polysaccharide matrices considered to play a key role in many chronic infections. Moreover, as phages do not affect mammalian cells, they are suitable for use in patients with immunodeficiency [

8]. Notably, unlike many antibiotics, such is the specificity of phages that the commensal flora is left largely intact [

9], reducing adverse effects associated with the loss of commensal organisms. Phages may also act synergistically with antibiotics and there is some evidence that adjunctive phage therapy can “re-sensitise” bacteria to antibiotics [

10]. While preformulated phage cocktails may be able to meet most clinical needs, a library of phages can be used to devise personalised phage formulations. Phages can be engineered to specifically target damaged or malignant eukaryotic cells while leaving healthy cells unharmed. This is because each phage has a specific receptor that it can recognize and bind to on the surface of its target cell [

11]. Although phages are unlikely to completely replace conventional antibiotics, except in limited clinical circumstances, PT nonetheless has the potential to be as radically transformational to medicine as antibiotics once were.

In addition, our understanding of the interrelationship (cross-talk) between bacteriophages and the immune system remains incomplete. Phages initiate the production of anti-phage antibodies (APA) in humans predominantly belonging to the IgM isotype, though IgG and IgA responses are also induced [

12]. However, it should be noted that there is very little information regarding immunity to bacteriophages in patients with CLL. Here we hypothesized that CLL patients might have preexisting, naturally-occurring antibodies against various phages, including those commonly used in phage therapy. These antibodies could influence infections and immune system regulation, also the efficacy of phages if PT is initiated in CLL patients.

Considering all above mentioned, we aimed to evaluate the URT microflora in CLL patients, assess the sensitivity of bacterial isolates to antibiotics and phages, also to detect the presence of naturally occurring antibodies in the sera of these patients, and evaluate their phage-neutralization potential, which could reduce phage effectiveness.

2. Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

Peripheral blood samples, together with nasopharyngeal and throat swabs, were collected from 22 chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients (age 50-75 y, 10 males and 12 female) at the M. Zodelava Centre of Hematology in Tbilisi, Georgia, based on informed written consent and ethical approval. All patients were newly diagnosed and remained untreated at the time of sample collection. Fourteen healthy volunteers of matching age and sex were also enrolled in the study after providing informed consent.

Microbiological Analysis

The oropharyngeal swabs taken from the nose and throat of patients and healthy volunteers were processed by standard culture-based methodology. Briefly, swabs were streaked on sheep blood agar (SBA) plates by four quadrant method, also inoculated in the tubes with trypticase soy broth (TSB). After incubation at 37°C 24- 36 hours, sub-culturing was performed on commonly used selective media, with focus on isolation of S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, E. coli, K. pneumonia and etc. Phenotypic identification was based on cultural- morphological characteristics, Gram staining and microscopy, the growth on differential media and basic biochemical tests, and completed by using analytical profile index (API) identification systems - API Staph, API 20 NE, API 20E, API 20 STREP (Biomereux, France).

Assessment of Antibiotic and Bacteriophage Susceptibility

The following antibiotics were used: Tetracyclines, Tobramycin, Moxifloxacin and Levofloxacin, all effective against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria; Vancomycin and Cefuroxime, highly effective against gram-positive microorganisms

. The antibiotic susceptibility of isolated bacteria was tested on Mueller-Hinton agar by Kirby-Bauer disc-diffusion method, according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) standards (

http://www.eucast.org). For vancomycin and linezolid, determination of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) on solid and liquid media was also performed.

The susceptibility to bacteriophages was studied by the standard phage spot test, followed with titration by the double layer agar technique [

13,

14,

15]. The commercial preparations Pyo Bacteriophage, Staph Bacteriophage, Ses Bacteriophage, Intesti Bacteriophage, Fersisi Bacteriophage, Enko bacteriophage (all products of “Eliava Biopreprations”, Georgia) were used in the study along with

S. aureus specific phage- PSA-1 cloned from the Pyophage preparation on the host strain

S. aureus GMH17.

Detection of Naturally-Occurring Anti-phage Antibodies

The binding ability of sera from 10 randomly selected CLL patients and 14 age- and sex-matched healthy volunteers to an S. aureus PSA-1 phage was assessed using an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Briefly, Nunc MaxisorpC 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates were coated with 50 µL of semi-purified preparation of phage PSA-1 at a concentration of 10⁸ pfu/mL in 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (CBB, pH 9.6; Sigma, USA). The plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. Blocking was performed using Pierce™ Protein-Free Blocking Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Sera were serially diluted 1:25, 1:50, and 1:100 in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Fifty microliters of each dilution were added to the corresponding wells in duplicates. For detection, a mixture of goat anti-human IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Invitrogen, USA) was used along with the substrate 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The plates were read at an optical density (OD) of 450 nm using a spectrophotometer (Selecta, Spain).

Phage Neutralization Assay

The phage neutralization reaction [

13,

14] was used to determine the neutralization activity of naturally-occurring antibodies to

S. aureus phages in the sera from CLL patients. The rate of inactivation of

S. aureus specific phage – PSA-1 was determined in this assay. The test was carried out over a 10- and 30-minutes incubation at 37°C of the sera from 16 patients (sera dilutions1:50 and 1:100) with phage suspension, containing 1×10

6 plaque-forming units per mL (pfu/mL). After 100X dilution of the reaction sample in the cold saline the surviving phages were enumerated on the host strain by the double-agar layer method and the neutralization percent was determined.

The neutralization constant was calculated by the formula: K = 2.3 X (D/T) X log (Po/Pt), where D is the reciprocal of the serum dilution, T - the time in minutes during which the reaction occurred (10 and 30 min in this case), Po - the phage titer at the start of the reaction, and Pt - the phage titer at time T.

Statistical Analysis

Microsoft Excel was used for data analysis. An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied to determine statistical significance. Statistical analysis of the groups examined in the neutralization test was conducted using the Mann–Whitney U-test for independent samples or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for paired samples. Results are presented as the mean phage inactivation rate (K) ± standard deviation (SD).

Statistical significance of p < 0.05 was used.

3. Results and Discussion

A total of 51 bacterial strains were isolated from 44 oropharyngeal swabs taken from the nose and throat of 22 CLL patients and identified at the species level. Among these, 42 strains were classified as opportunistic pathogens, of 17 species in total, such as Pseudomonas luteola (1 strain), S. epidermidis (8), S. salivarius (2), S. lentus (5), S. capitis (2), S. warneri (2), S. hominis (2), S. xylosus (1), S. heamolyticus (1), S. saprophyticus (1), S. cohnii (1), Kocuria varians/rosea (1), S.lentus (3), S.hominis (1), S.capitis (4), S.saprophyticus (1), Aerococcus. viridans (3), Bacillus subtilis (3). Nine isolates were identified as S. aureus. The great majority of above listed bacteria are capable to cause infections in immunocompromised patinets.

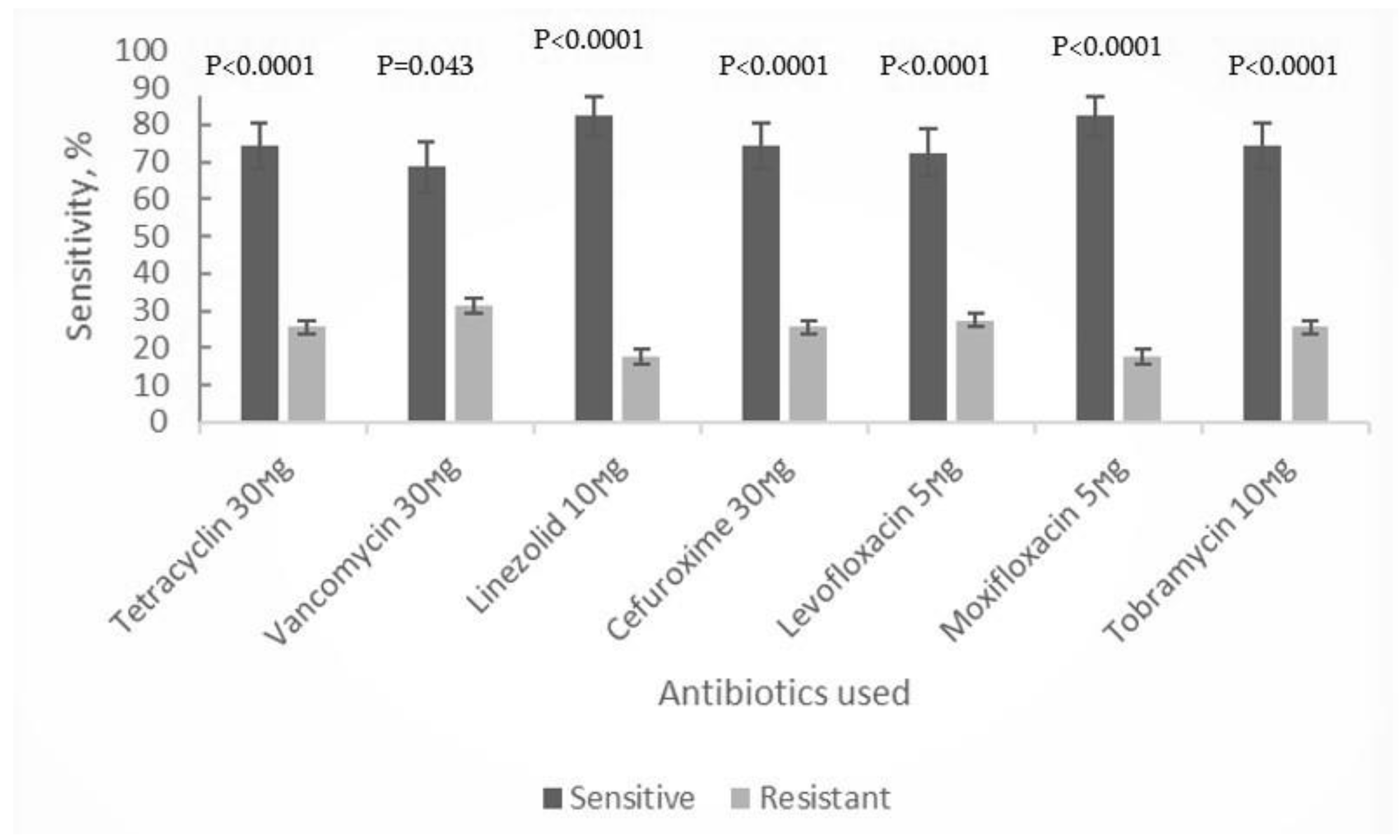

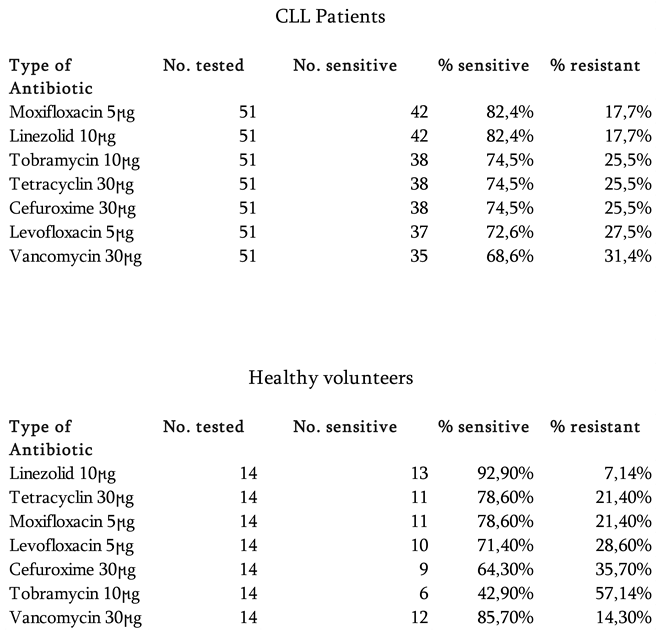

The antibiotic sensitivity testing involved the representatives of different antibacterial drug groups, namely tetracycline, vancomycin, linezolid, cefuroxime, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin and tobramycin. In our study, the collected isolates of abovementioned species, showed moderate to high susceptibility to all antibiotic groups (≥58%of all tested strains), with linezolid and moxifloxacin demonstrating the highest efficacy (82.35%). However, for strains of

S. aureus intermediate level resistance to glycopeptide vancomycin was observed, while susceptibility to other antibiotic groups remained high

(Table 1, Figure 1).

Fourteen bacterial strains were isolated from 12 nasopharyngeal swabs of healthy volunteers and among these, 11 strains were classified as opportunistic pathogens such as S. epidermidis (6 strains); S. salivarius (1), S. lentus (2), S. xylosus (2). The 3 isolates were identified as S. aureus, carriage of which can be observed in up to 20% of practically healthy population.

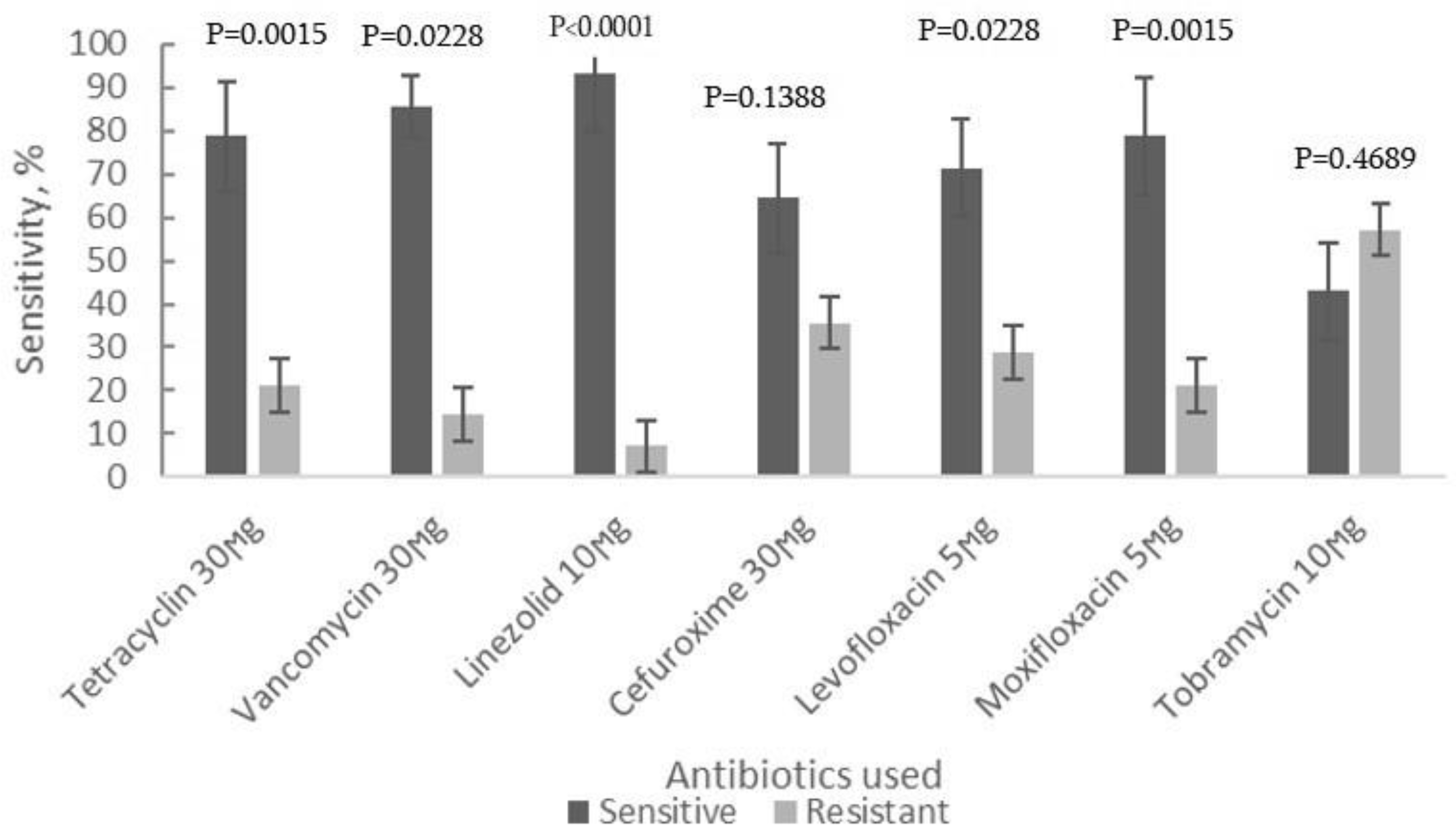

The antibiotic sensitivity testing of bacterial isolates from healthy control group was done using the same set of antibacterial drugs as for the strains of CLL patients. Moxifloxacin and linezolid appeared again the most effective antibiotics against these bacterial isolates with susceptibility rates ranging from 82.4% to 92.9%, with the Linezolid showing the highest efficacy

(Table 1, Figure 2).

To our knowledge, there have been no randomized trials evaluating the use of antibiotics in patients with CLL. In addition, no evidence-based guidelines for the antimicrobial treatment of these patients exist in Georgia. Our data on the high activity of antibiotics from the oxazolidinone group towards the majority of obtained bacterial isolates, both pathogenic and opportunistic microflora, indicates their potential in treatment of secondary bacterial infections, primarily caused by gram-positive bacteria, in CLL patients.

The commercial bacteriophages (Pyo, Ses, Enko, Intesti, Pyophage, and Staph-phage) didn’t show activity against the collected bacterial isolates, that can be mainly explained by the species composition of this group of bacterial isolates. The great majority of strains, based on phenotypic identification, belongs to miscellaneous

Staphylococcus species, phages specific to which are not included in the currently commercial phage cocktails. Insensitivity of 9 isolates of

S. aureus to commercial phage products containing staphylococcal phages seems to be quite unusual since the

S. aureus strains of different origin generally are highly susceptible to Staph phages [

17]. These results indicate the need for more clarification regarding specifics of

S.aureus strains from CLL patients, in terms of cell wall receptors and bacterial host defense systems. Interestingly, the individual phage cloned from the “Pyophage” preparation and propagated on the host strain S. aureus GMH17, appeared to be lytic to all strains of

S. aureus. A number of isolates of coagulase negative staphylococci were found to be weakly sensitive to this cloned phage (data not shown here). Our findings emphasize the need for further research to identify the most effective phages against bacteria commonly associated with CLL patients in Georgia.

Many studies have shown that phage administration can trigger a phage-specific humoral immune response. However, the mechanisms regulating this response and their potential impact on treatment efficacy remain poorly understood [

12,

18,

19,

20]. Additionally, case reports on the use of phage therapy in humans have provided conflicting evidence regarding whether phage-specific antibodies inhibit the efficacy of phages [

21,

22].

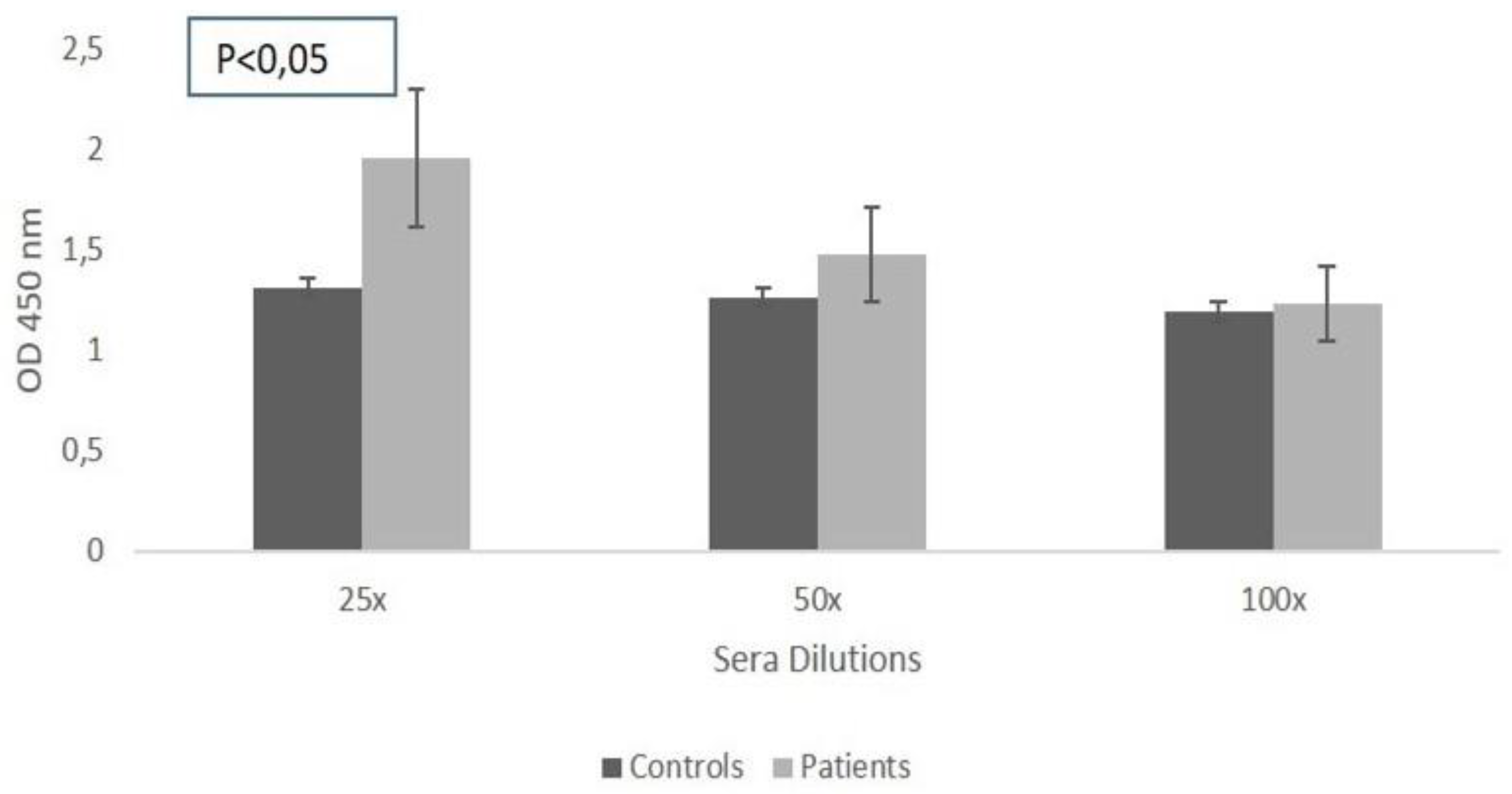

Therefore, the next phase of our study was focused on examining the presence of naturally occurring antibodies against phage from the Pyophage cocktail propagated on

S. aureus, in the sera of patients and healthy volunteers. The study revealed a certain, moderately high, binding rate of circulating naturally occurring antibodies to the tested phages in both, CLL patients

(Figure 3) and healthy individuals.

It’s understandable, that antibodies have different effector functions, and not all of them are neutralizing. This also applies to naturally-occurring anti-phage

antibodies detected by us. Their role in phage neutralization depends on various specific factors, such as the antibody's binding site on the phage, its isotype, and its interactions with both the phage and the host immune system [18,23]. To evaluate the neutralizing ability of the detected antibodies, a phage neutralization assay according to classical methodology [

13,

14] was performed.

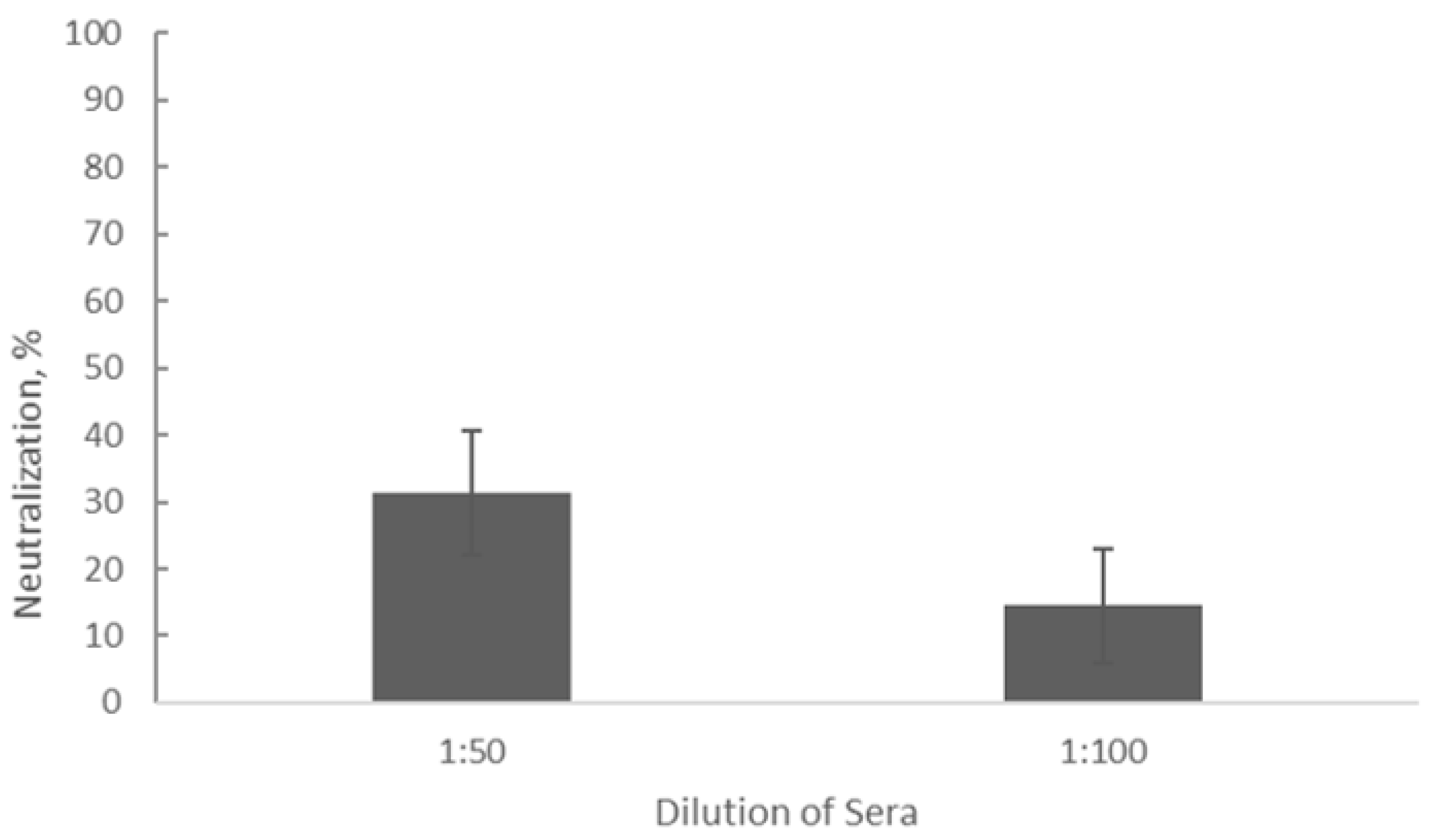

Figure 4.

Inhibition of phage activity by sera from CLL patients (n = 16) assessed by the Phage Neutralization Reaction. Dilutions of 1:100 and 1:50 were analyzed.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of phage activity by sera from CLL patients (n = 16) assessed by the Phage Neutralization Reaction. Dilutions of 1:100 and 1:50 were analyzed.

Our results showed the average neutralization rate of detected antibodies was 14.59% ± 0.05 (p < 0.05) at a serum dilution of 1:100 and the average neutralization constant was calculated as K = 0.65 ± 0.22 (p < 0.05). At a serum dilution of 1:50, the average neutralization rate was 31.4% ± 0.05 (p < 0.05) and the average neutralization constant K comprised 0.63 ± 0.13 (p < 0.05). This indicates that at this low dilution of sera, compared to the control tube (without sera), approximately one-third of phage negative plaques were developed on the plates with the host stain due to the presence of antibodies in the sera of CLL patients. This means that the naturally occurring antibodies circulating in the blood of CLL patients and capable of binding to the tested phage particles, only partially inhibit phage activity. Based on these preliminary data and also a number of indicators of the virulent nature of the phage PSA- 1 (data not shown here), it can be considered as one of the candidates for further studies on phage application for treating URT bacterial infections of staphylococcal origin in CLL patients, alone or in combination with antibiotics.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates still high possibility of elimination of bacterial colonization in CLL patients (diagnosed, but non-treated for CLL) through the rational use of antibiotics. Additionally, phage therapy should be considered as part of a broader, multidisciplinary approach to managing bacterial infections in CLL patients, in conjunction with appropriate antibiotic treatments, to optimize patient outcomes and address the growing challenge of antibiotic resistance. Effective PT can be achieved by selecting active phages (monophages or phage mixtures) from the large phage collections, such as Eliava Institute’s collection, to be used for preparation of customized phages (autophages). Furthermore, during the selection process in preclinical studies and also in the course of PT, it is recommended to monitor occurrence of neutralizing antibodies to assess the probability of therapeutic phage neutralization in vivo, that might impact the treatment outcome.