1. Introduction

Albendazole (ALB) and Ivermectin (IVM) are widely used worldwide for controlling internal or external parasites in farm animals, including camels [

1,

2,

3,

4]. At the same time, camel milk is more and more present on the market and consumed out of the traditional nomad camp [

5,

6]. Moreover, with the development of a more intensive dairy camel farming, antiparasitic prevention should be more systematic with higher risks of residues in camel products. A withdrawal period is applied for milk after antiparasitic treatment of camels but based on recommendations regarding cattle. Indeed, there is a lack of data regarding the residual risks in camel milk. Yet, it is known that the pharmacokinetics of these antiparasitics are depending on the animal species [

7].

Very few studies were available on Ivermectin or Albendazole residues in camel milk (see the review of Utemuratova et al., [

8]). Bengoumi et al, [

9] have investigated the pharmacokinetics of Eprinomectin, an antiparasitic drug derived from Avermectin, in camel plasma and milk. At our knowledge, there was no published study regarding Albendazole residue in camel milk, contrary to milk from other species as goat [

10] or sheep and cattle [

11].

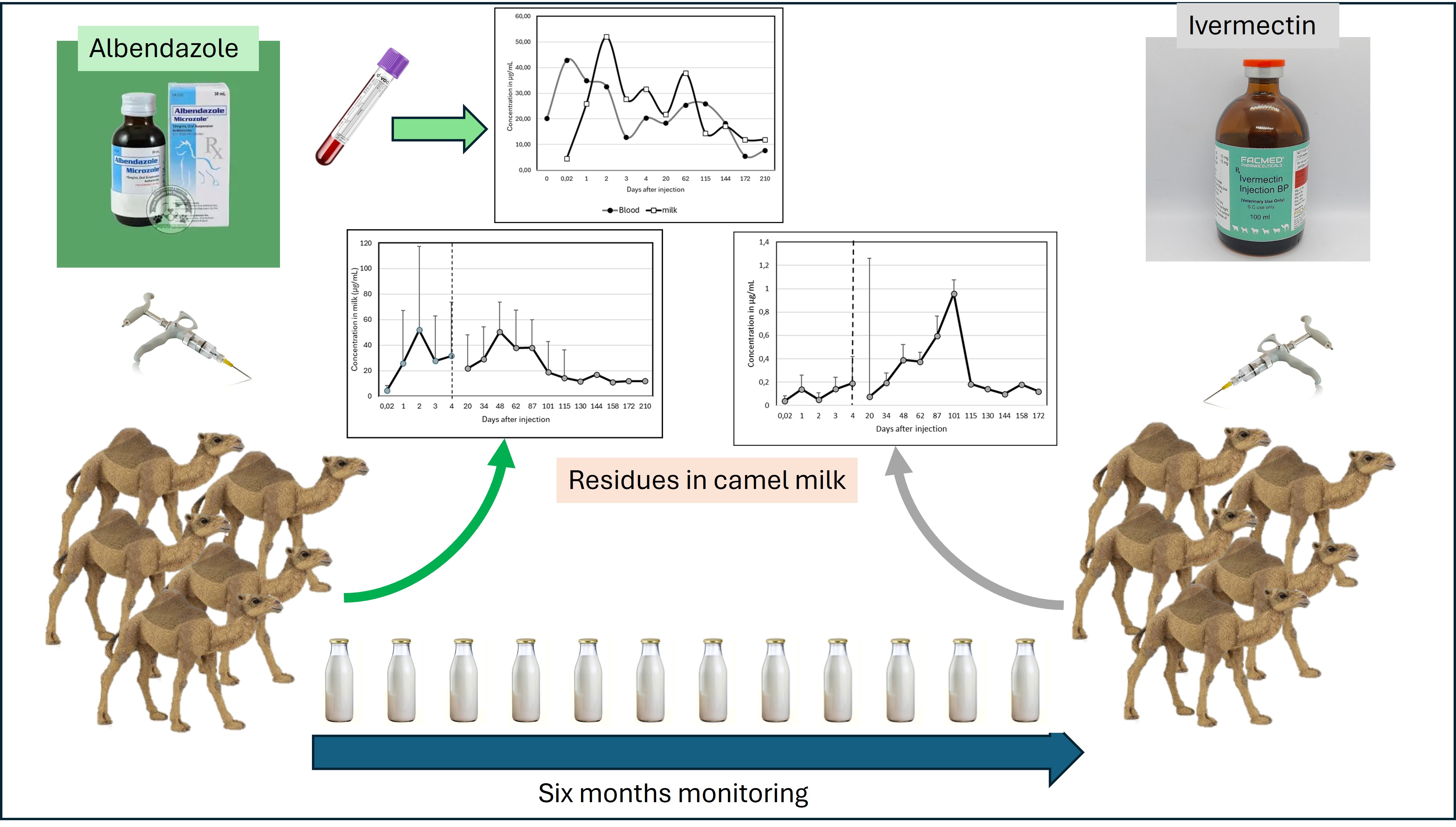

In order to assess the risk of antiparasitic residues in camel milk, an experiment was performed on dromedary (Camelus dromedarius) where the residues of Ivermectin and Albendazole were assessed in milk after injection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

A total of ten lactating one-humped camels (Camelus dromedarius, Aruana breed, dairy type), aged 6–7 years and at 5–6 months postpartum, were included in the study. The animals were divided into two treatment groups, with five camels receiving Albendazole (Ricobendazole) and five camels receiving Ivermectin, according to manufacturer instructions. All animals were clinically healthy at the beginning of the trial, although minor health fluctuations during the extended sampling period could not be excluded.

The camels were maintained under identical farm management conditions at Otemis-Ata farm (Akshi village, Yili district, Almaty region, Kazakhstan). They had continuous access to natural pasture supplemented with hay, and water was available ad libitum. Milking was performed manually twice daily during the autumn–winter months and three times daily in the spring–summer season, following local dairy practices. Individual daily milk yields were not recorded, as the focus was on milk quality and residue kinetics rather than productivity.

The animals were selected because Camelus dromedarius is the predominant dairy type in Kazakhstan and represents the main resource for milk production in the region. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with national guidelines for animal welfare, and the protocol complied with ethical standards for research on food-producing animals.

It started on August 28, 2023, and ended on February 19, 2024, with a control point on July 3, 2024. The total duration of the trial was six months.

2.2. Drugs and Treatment

2.2.1. Anthelmintic Drug

The preparation used was Ricazole®, an anthelmintic injection containing the active substance Albendazole sulfoxide (Ricobendazole). It is a new-generation injectable drug and the first of its kind based on the active metabolite of Albendazole. The treatment is generally administered once a year in the second half of September as a preventive measure. Ricazole® provides simultaneous action against all types of helminths, with an efficiency of 98–100%. It acts quickly, has high bioavailability, and effectively overcomes resistance to benzimidazoles.

The Ricazole® was injected intramuscularly at 18 ml to each camel at a rate of 1 ml (4 mg) per 25 kilograms of body weight (according to the instructions). The weight of each camel varies from 460-480 kg.

2.2.2. Antiparasitic Drug

Ivermek®, containing the active ingredient Ivermectin, is administered to animals for therapeutic and preventive purposes in cases of arachno-entomoses and nematodoses. It is an antiparasitic drug in injectable form, with treatment conducted once a year in the second half of September as a preventive measure. The drug provides simultaneous action against all types of parasites, ensuring fast effectiveness and high bioavailability. It was administered intramuscularly at a dose of 10 mL per camel, based on a dosage of 1 mL per 50 kg of body weight, following the instructions. The weight of each camel ranged between 460 and 480 kg. No blood samples were taken in this group.

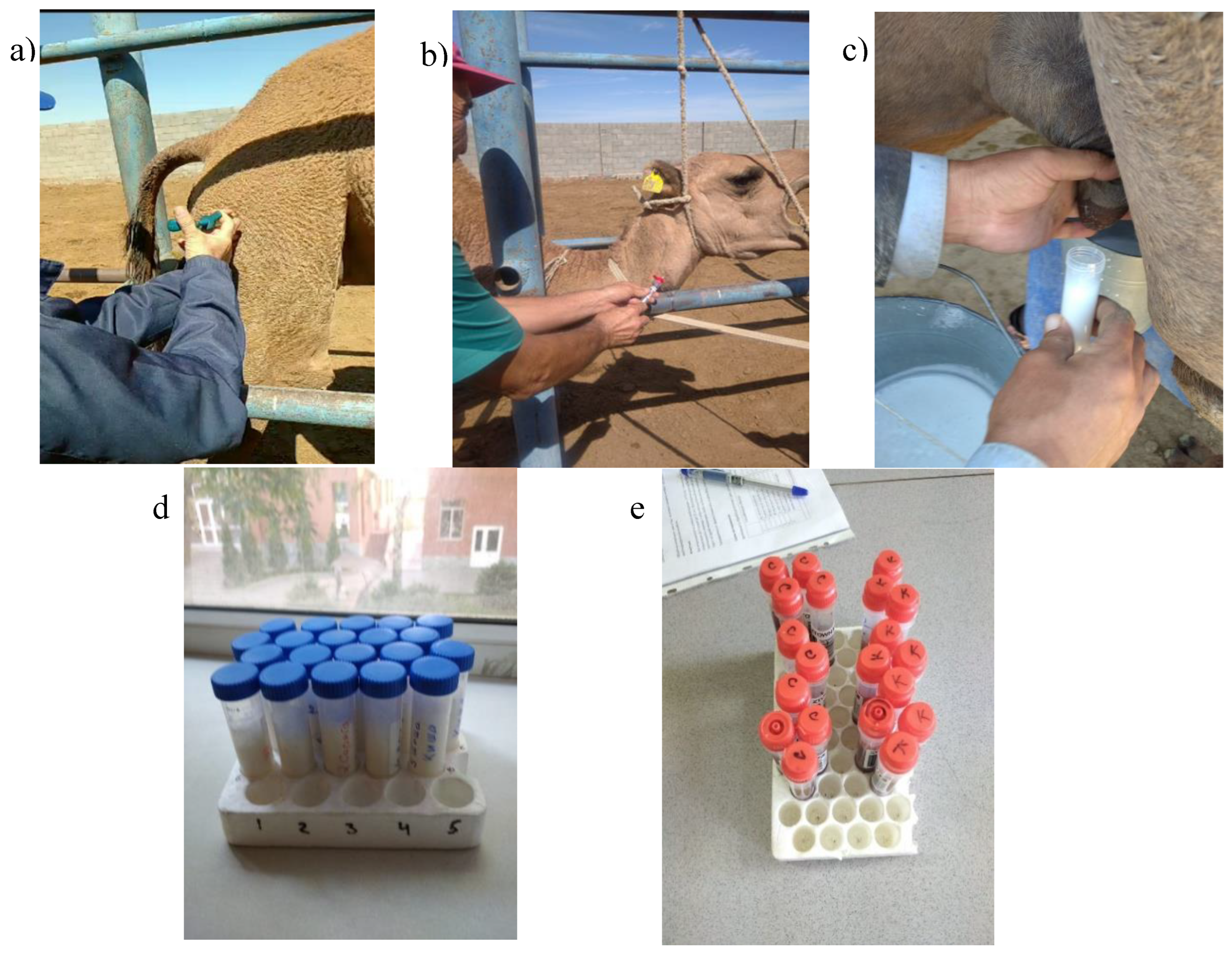

Figure 1.

Photos from the course of the experiment: a) intramuscular injection of the medication; b) blood sampling; c) milk collection during manual milking; d) milk samples; e) blood samples.

Figure 1.

Photos from the course of the experiment: a) intramuscular injection of the medication; b) blood sampling; c) milk collection during manual milking; d) milk samples; e) blood samples.

2.3. Chemicals and Reagents

The Albendazole sulfoxide, VETRANAL reference standard (CAS No.54029-12-8, purity ≥99.0 %) was acquired from Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Ivermectin, a reference standard (CAS No. 70288-86-7, purity ≥99.0%), was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Ltd. (USA). ACN was of HPLC grade and was provided by VWR, BDH Chemicals. Potassium phosphate and MeOH were of HPLC grade and was supplied by Sigma-Aldrich, Ltd. The water (18.25 MΩ*cm, 25 °C) used in the experiment was purified and generated by an automatic water purification system (Direct-Q3 UV, Merck Drugs & Biotechnology Co., Inc., Fairfield, OH, USA). The solution entered into the HPLC system was first degassed by an ultrasonic apparatus (621.06.006, Isolab Laborgerate GmbH, Germany).

2.4. Preparation of the Standard Stock

The standard stock solutions of albendazole sulfoxide was prepared individually at a concentration of 1 mg/mL by dissolving each target in ACN and then stored stably for two months in actinic glassware at −18 °C. The standard working solutions 0,5 mg/mL, 0,1 mg/mL, 0,05 mg/mL were prepared daily by gradually diluting the standard stock solutions with ACN.

Standard stock solutions of ivermectin were individually prepared at a concentration of 1 mg/mL by dissolving each target in ACN+H₂O (50:50) and were then stably stored for two months in amber glass containers at −18 °C. Standard working solutions of 0.5 mg/mL, 0.1 mg/mL, and 0.05 mg/mL were prepared daily by stepwise dilution of the stock solutions in ACN and were then stably stored for two months in amber glass containers at −18 °C. Standard working solutions of 0.5 mg/mL, 0.1 mg/mL, 0.05 mg/mL, and 0.01 mg/mL were prepared daily by stepwise dilution of the stock solutions in ACN.

2.5. Sample Acquisition and Preparation

2.5.1. Sample Acquisition

Milk and blood samples were taken before injection, then 20 min (0,02), 1, 2, 3, 4, 20, 34, 48, 62, 87, 101, 115, 130, 144, 158 and 172 days after injections. Milk was collected immediately into sterile 50 ml centrifuge tubes (40-45 ml x 2) during milking. Blood samples were taken from a blood vessel in the neck area directly into serological tubes. The agenda of blood sampling was day 0 (before injection), then 20 min (day 0.02), 1, 2, 3, 4, 20, 62, 115, 144, 172 and 210 days. Blood samples were transported to the laboratory warm for better coagulation. And milk samples were transported in refrigerated bags with coolants at a temperature of 5-7 °C. Then they were immediately placed in a freezer at -20 °C.

Upon receipt of blood samples in the laboratory, blood serum was isolated into clean tubes, then stored at a temperature of -20 °C

2.5.2. Sample Preparation

Sample preparation was done according to Blanco-Paniagua et. al, [

12]: 200 µL of ethyl acetate were added to each 100- µL aliquot of milk and plasma. The mix was vortexed horizontally for 1 min and then centrifuged at 1,200 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and evaporated to dryness under N2 at 30°C. 500 µL of hexane and 300 µL of acetonitrile were added to evaporated samples, and the mix was vortexed horizontally for 1 min and then centrifuged at 1,200 g for 10 min at 4°C. Hexane was eliminated, and the rest was evaporated to dryness under N2 at 30°C. Samples were resuspended in 100 µL of cold methanol and injected into the HPLC system. Samples from in vitro assays were injected directly into the HPLC system.

2.6. Instruments and Conditions LC

2.6.1. Ricazole

The conditions for HPLC analysis of albendazole sulfoxide were based on a method described by Blanco-Paniagua et al., [

12], with modifications. The mobile phase used was potassium phosphate (pH 7)-acetonitrile (75:25) with a flow rate of 1.20 mL/min and a UV absorbance of 225 nm.

2.6.2. Ivermectin

Chromatographic separation was performed on an LC-20 Prominence system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), with detection achieved using a UV detector (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The targets were retained using a BAKERBOND Q2100 Phenyl-Hexyl column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 3 microns). Instrument connection and condition control were managed using LabSolutions software (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The column thermostat temperature was maintained at room temperature, and the injection volume was 20 µL. The mobile phase consisted of MeOH:ACN (1:1) + 42 mL H2O with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The duration was 12 minutes, and the detection wavelength was set to 225 nm during this period.

2.7. Method Validation

For albendazole-related residues and ivermectin, calibration was linear within the concentration range of 0.05–0.5 mg/mL. For the calculation of precision, LOD, and LOQ, a blank camel milk sample free of target analytes was used. This blank sample (n = 3) was spiked with albendazole and ivermectin at 0.05 mg/mL. Additionally, recovery rates (R) were determined. The results of the validation parameters of the method are presented in

Table 1.

3. Results

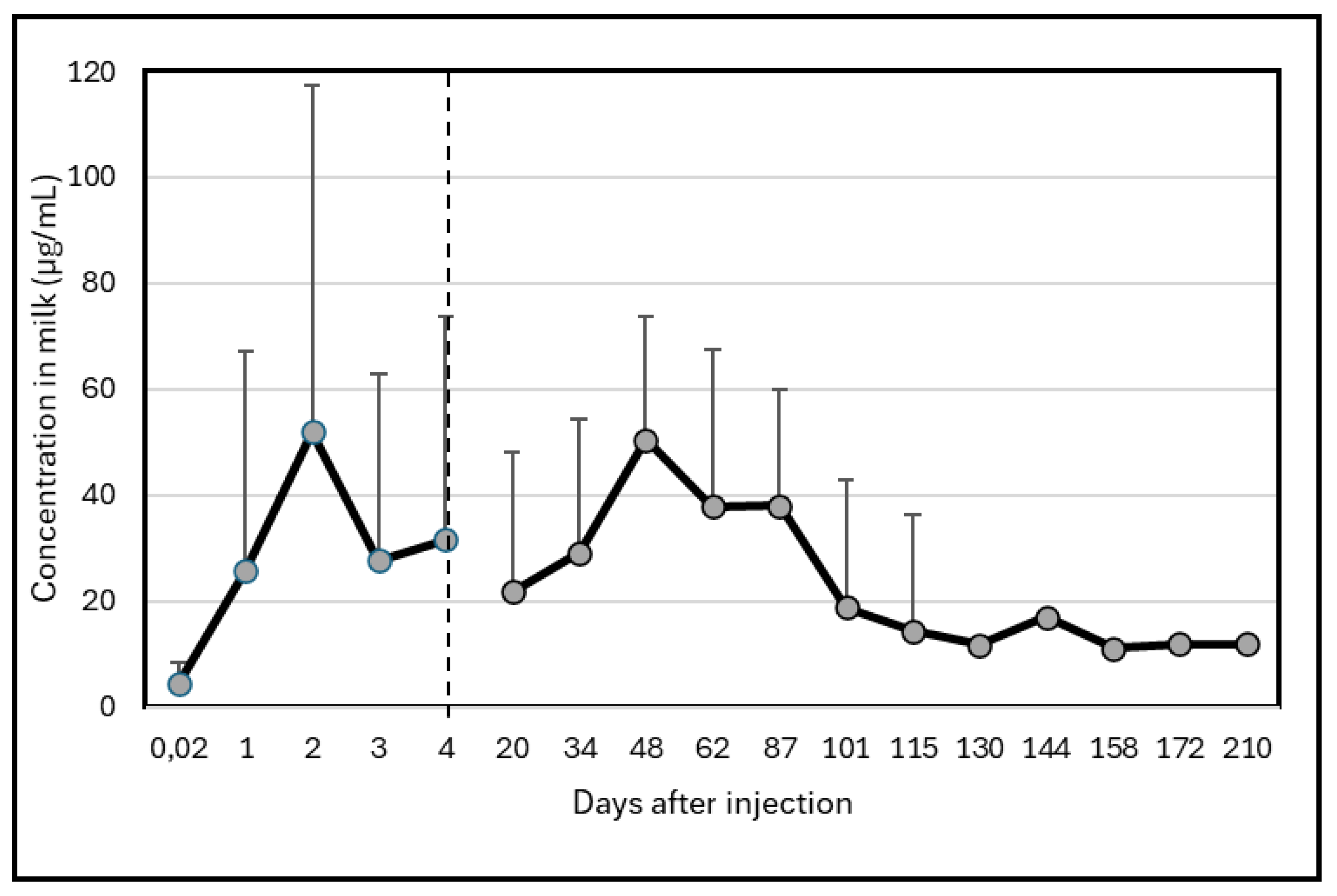

3.1. Albendazole Residues

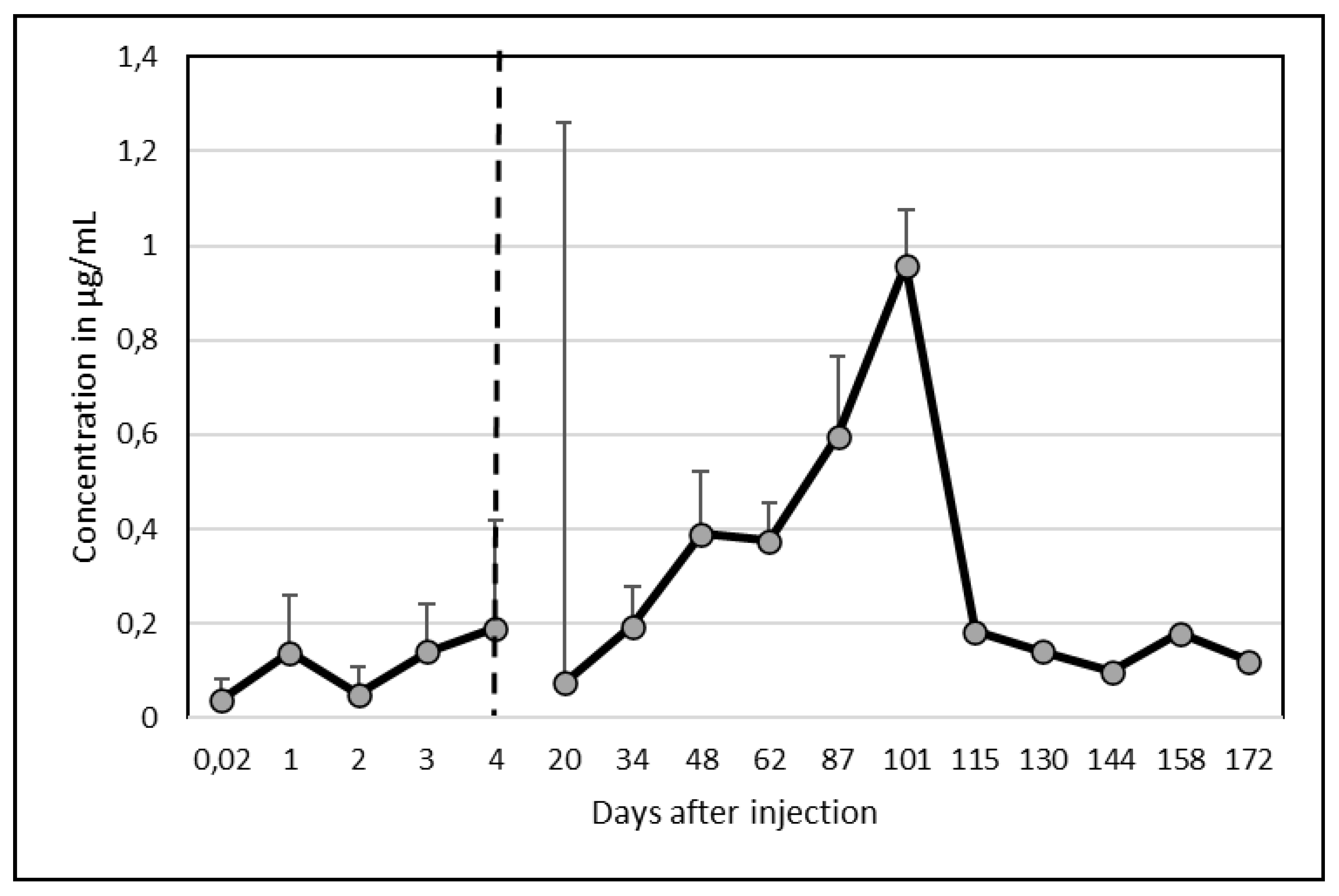

High variability between animals occurred. Two camels did not excrete high quantity of Albendazole molecule in milk with a maximum concentration at around 20 µg/mL while the 3 other camels presented an important peak of excretion above 100 µg/mL. However, the peak of excretion appeared at different times: at day 2 for two camels and at day 48 for the last one. One of the camel presenting a peak at day 2 showed a second one less important (but still above 100 µg/mL) on day 87. Consequently, the mean kinetic (Figure 1), showed maximum concentrations on day 2 (52 ± 65.2 µg/mL) and day 48 (50 ± 63.1 µg/mL). After 210 days, the residues of Albendazole remained at around 11 µg/mL, i.e. 2 to 5 times the concentration at day 0. □

Figure 1.

Changes in Albendazole concentrations (µg/mL) in camel milk after injection at day 0.

Figure 1.

Changes in Albendazole concentrations (µg/mL) in camel milk after injection at day 0.

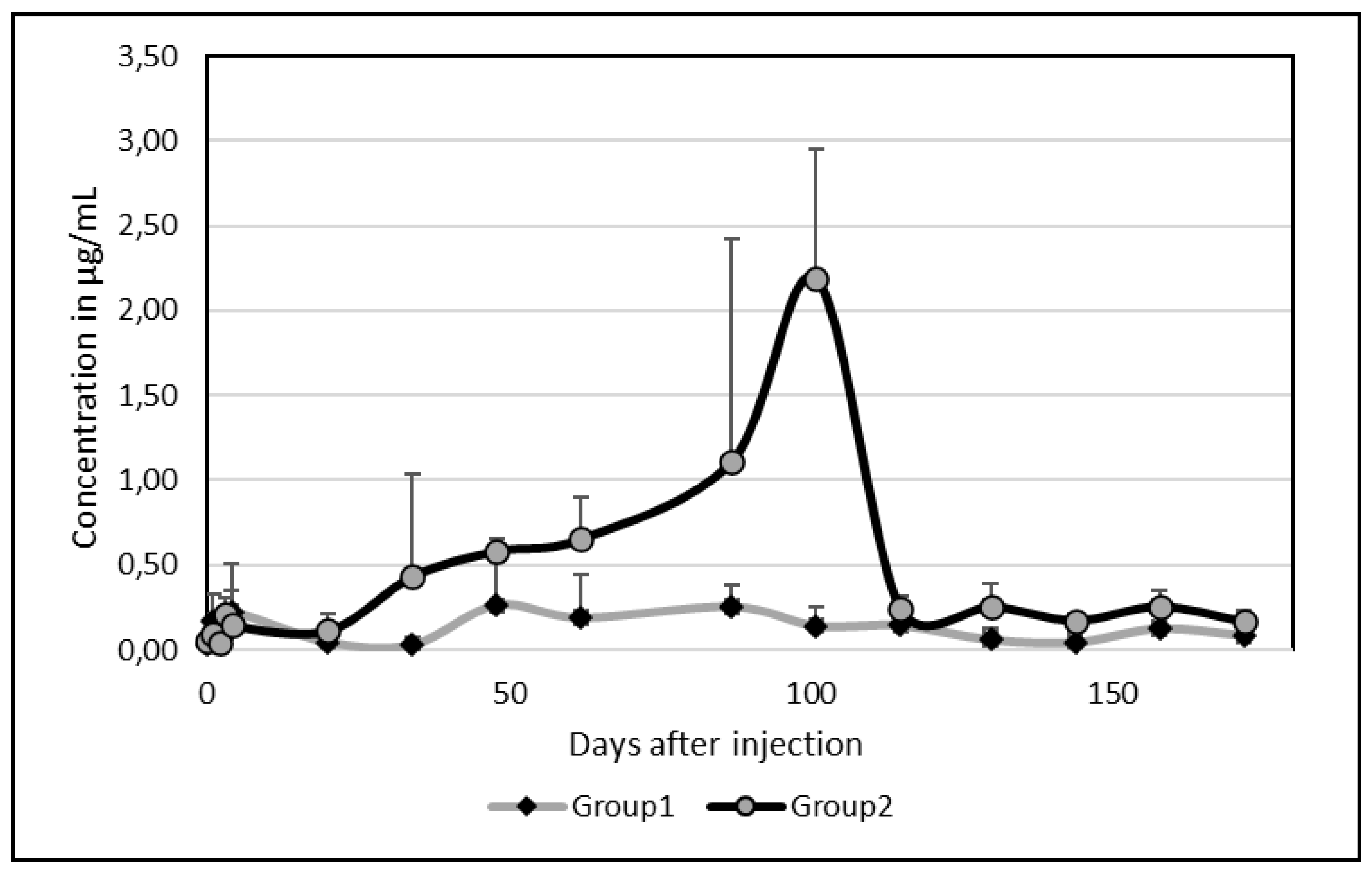

3.2. Ivermectin Residues

As for Albendazole, there was an important between-camel variability. Among the 5 camels, 2 presented an important peak of excretion in milk at day 87 and 101 with values above 2 µg/mL (2.04 and 2,72 µg/mL respectively). By comparison of the kinetics of these 2 groups without (group 1) or with (group2) peak of excretion, a clear difference was appearing (

Figure 2).

Contrary to Albendazole, however, on average, only one peak appeared at date 101 (0,96 ± 1,19 µg/mL). After 172 days, the mean concentration was still 0.12 µg/mL (

Figure 3) but ivermectin disappeared completely after 130 days in one camel and after 144 days in a second one.

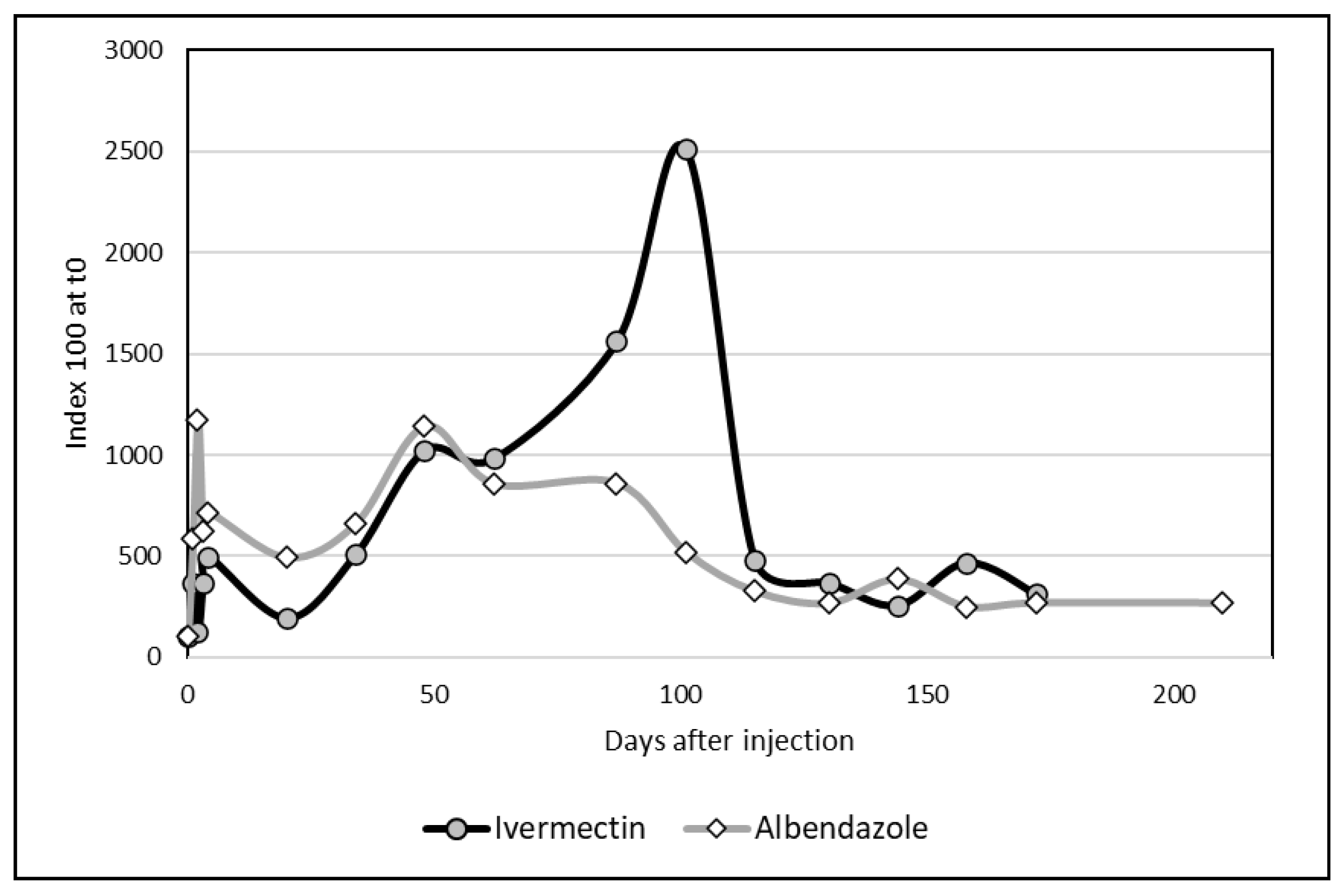

3.3. Comparative Kinetics

The two graphs regarding Albendazole and Ivermectin could be compared by using index (100 at d0 for the both molecules). If the kinetics appeared comparable until d48, the changes in ivermectin differed importantly due to a sharp peak at day101. However, the differences between the two distributions were not significant (

Figure 4) according to the non-parametric test of Kolmogorov-Smirnov.

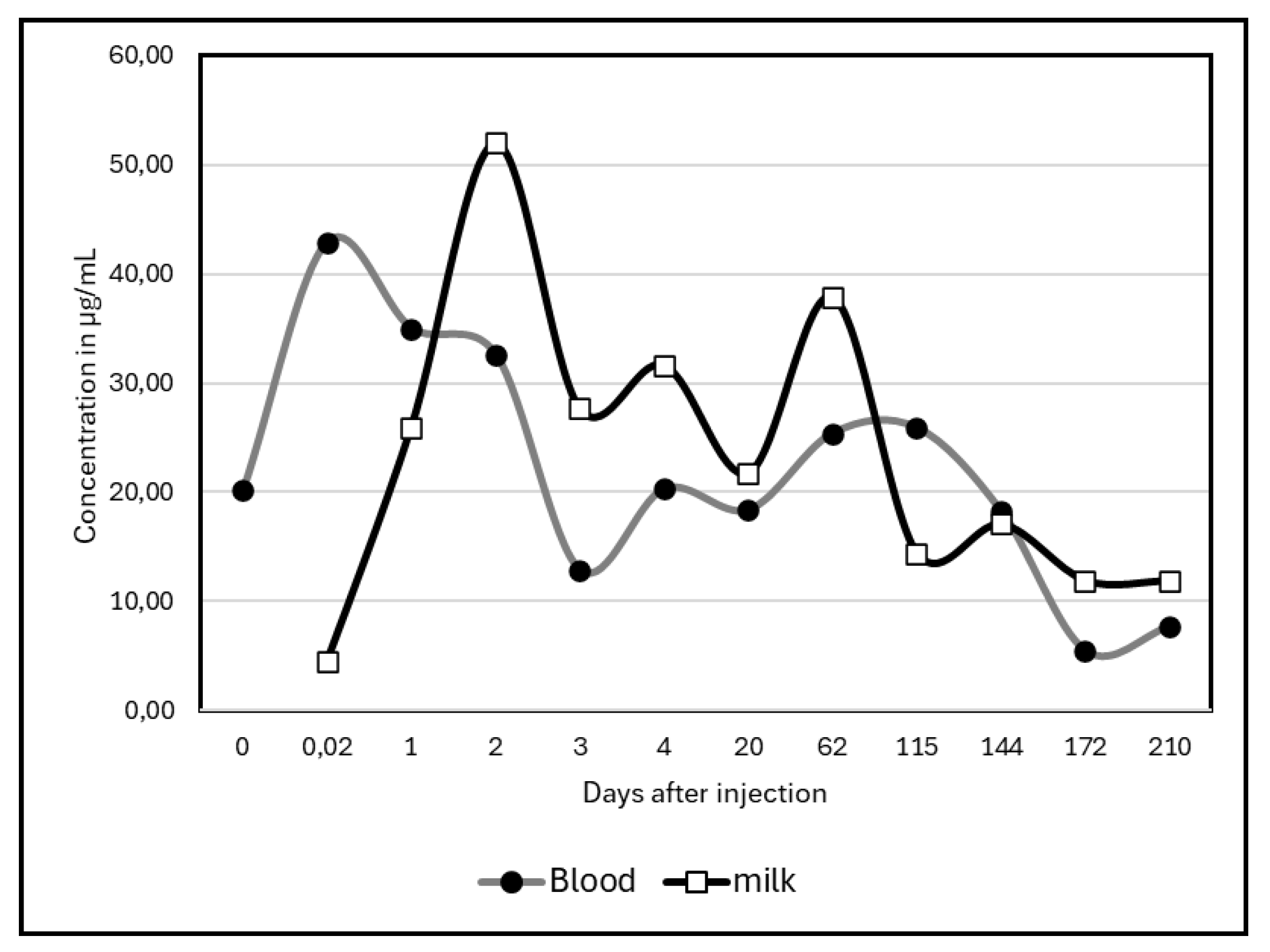

Regarding the comparison of kinetics in blood and milk, only study of Albendazole was available. Statistically non-significant (test of Kolmogorov-Smirnov), the two graphs showed however a slight gap between blood concentrations and milk concentrations during the first days of the experiment (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

If the antiparasitic residues in milk was widely investigated in different farm animals [

13] or in specific species as bovine [

14,

15,

16], ovine [

17], caprine [

18,

19,

20] or even in donkey [

21], most of these investigations were focused on the detection of residues in a panel of samples whatever the delay from antiparasitic distribution and the way of administration (injection, bolus or tablets). The rare references in the anthelmintic residues in camel are limited to their pharmacokinetic in plasma [

22]. At our knowledge, no reference regarding camel milk was available, except few studies regarding pharmacokinetic of ivermectin [

23] or close molecules [

9]. Moreover, the comparison with other species is difficult because the residues are depending on the species, the administration way and on the dose distributed [

24]. Another difficulty is due to the high variability in milk production which could impact the assessment of the drug concentrations because the potential dilution effect. Such high between-camel variability was observed also in our study although all the camels were at similar lactation stage. Indeed, due to the seasonal reproduction cycle in this species, all the camels were at the end of lactation (September) which is the month in which the anthelmintic treatment is generally administered at the entry of the autumn season.

4.1. Residues of Albendazole in Milk

Regarding Albendazole, the concentration in milk varied according to the metabolites of the molecules, notably Albendazole sulphoxide (ABZSO), Albendazole sulphone (ABZSO

2) and Albendazole 2-aminosulphone (NH2ABZSO²). In their study in sheep milk, De Liguoro et al., [

17] reported that the molecule of Albendazole was rapidly oxidized to ABZSO and then to ABZSO² after administration and were present in milk at high levels (1–4 µg/g) in the 24 hours after treatment. Although reported values by Santos et al. [

10] were 100 times higher than in other references, the highest Albendazole concentration observed in goat milk occurred 24 hours after administration with values of 101.20 ± 37.4 μg/mL, and the molecule was not detectable in 50% of the samples after 72 hours. After 4 days (96 hours), Albendazole was not detectable in 100% of the samples. According to Moreno et al., [

24], in cow milk the maximal concentration was observed 12 hours after administration, but at a level around 0.28 µg/mL after administration by SC injection while oral administration lead to higher residues in milk, up to 1.12 µg/mL. In goat milk again, the maximum concentration of Albendazole metabolites were also observed on the first day after administration with a rapid decline until the fourth day where the level of residue was below the MRL (0.1 µg/mL) leading to recommend a withdrawal period of four days [

19].

In an already old study including four cows receiving 10 mg/kg LW of Albendazole, Fletouris et al. [

25] found also higher concentrations of the metabolites after 12 hours, but with different patterns according to the metabolites involved: Albendazole sulfone reached its maximum at the 24h milking (on average 0.81 µg/mL) while Albendazole sulfoxide was higher 12hours after administration (on average 0.52 µg/mL). The third metabolite (2-aminosulfone Albendazole) appeared in lower quantity with the peak at 36h (0.13 µg/mL on average). In all the cases, a rapid elimination occurred, especially for sulfoxide and sulfone metabolites (below MRL after 48 hours), the third metabolite declining more slowly, reaching MRL after 3-4 days.

Higher sulfone metabolites concentrations in cow milk, 12 hours after injection, were also reported recently by Imperiale and Lanusse [

26] respectively 0.86 µg/mL for sulphone and 0.28 µg/mL for sulfoxide, followed by a rapid elimination after 24 hours.

Compared to the other species, the pattern of Albendazole excretion in camel milk appeared quite different. It is notably marked by a slow decline, and, even if a peak was observed 48 hours after injection, a second occurred at day 48 which was never observed in other species. Probably, being at the end of lactation, the daily milk production could vary considerably, explaining anormal concentrations of residues.

The Albendazole residue in plasma appeared early than in milk in our study. Similar observation was done in sheep plasma for long time [

27], but with difference between the metabolites, Albendazole sulphoxide appearing more rapidly (peak at 1.98 µg/mL less than 8 hours after administration) while sulphone appeared in plasma more slowly with a maximum of 0.5 µg/mL, 24 h after intraruminal administration. In an experiment in calf receiving also albendazole by intraluminal injection, the main metabolite (sulphone) appeared within 21 hours after [

28] with a peak between 1.89 and 2.53 µg/mL according to the type of diet. Sulphoxide metabolite appeared also sooner (between 11 and 18 hours post-administration according to the diet. The plasma kinetic was similar between sheep and goat [

29].

4.2. Residues of Ivermectin in Milk

The pattern of ivermectin excretion in milk of camel was quite different with a maximum excretion long time after administration, in our case after more than 3 months, that was never observed on other species. Even if this peak was due to the exceptional maximum concentration in 2 camels among 5, the global ivermectin residue remained important even up to 5 months (172 days) and above the MRL (0.01 µg/mL).

In cattle treated with microdose of Ivermectin, Alvinerie et al. [

30] found a maximum in plasma concentration (0.46 ± 0.20 ng/ml) on the first day after administration, and in milk (0.27 ± 0.16 ng/ml) at day 3. In goat, the same authors [

18] observed a slight different pattern with a maximum both in plasma (6.12 ng/mL) and milk (7.26 ng/mL) after 2.8 days with half-life absorption of 1.2 days. However, globally, there was high variability between the references and species, regarding milk, both for the values of the maximum residue (Cmax) and the time of maximum (tmax). Thus, in cow milk, Cmax could vary between 0.27 and 75 ng/mL and tmax 1.8 to 8 days, in sheep milk, 10-22.7 ng/mL and 1-1.3 days, in goat 3-24 ng/mL and 1 to 3 days respectively [

21].

The only reference involving camel milk is that of Oukessou et al., [

23]. In their study, these authors found a Cmax of 2.74 ng/mL and a tmax of 17.3 days. Thus, even if our results differ from that of these authors, it seems that ivermectin molecule is excreted in camel milk quite later than for the other species, leading to consider a longer withdrawal period in lactating camel.

4.3. Risks for Consumers

Due to the lipophilicity of molecules as ivermectin, even with dose below the MRL, the risk of chronic contamination may occur in consumers, and can have a deleterious effect on the consumers, especially when the molecules are detectable several days or even months after administration. Ivermectin notably can persist in goat and cow milk until 25 days, 3 weeks in sheep milk and according to our observation almost 6 months in camel milk.

The main risk for consumers is allergic reactions such as skin rashes and respiratory issues, and endocrine and neurological disruptions [

31]. Anthelminthic residues could act also on the immune system of the children affecting their development and their health. Albendazole could have even teratogenic effect detected on pregnant mice [

32]. Long-term exposure to low doses could also contribute to drug resistance, affecting future antiparasitic treatments of the consumers.

5. Conclusions

The regulations regarding the commercialization of camel milk cannot be based on the knowledge in pharmacokinetics of antiparasitic treatment or prevention obtained in milk from other species. The persistence of the residues, especially Ivermectin appeared quite longer, increasing the risk exposure for the regular consumers. Clear guidelines and more research on residue dynamics according the way of administration, the quantity of administered medicine and the type of camel (Bactrian or dromedary) are necessary to ensure consumer safety. .

Author Contributions

GK: Conceptualization, project administration and team supervision, funding acquisition and revised writing; ZB: Sampling and part of analyses, material and methods writing, data collection; NA: conceptualization and supervision; SA: investigation and methodology; ZM: investigation and sampling.; FA: Laboratory analyses and supervision; ZK and DU: bibliography and analyses; BF: data analysis, first writing, validation.

Funding

This study was financed by Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the frame of project BR22886598.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Camel antiparasitic treatment was conducted strictly in accordance with ethics committee guidelines of Co Antigen LTD (protocol 10, from October 18, 2022) and based on the order of the Minister of Agriculture of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated November 19, 2009, No. 744 for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

The study was conducted with the agreement of the camel owner. The antiparasitic injections were achieved in accordance with the current veterinary practices, all animals remaining under their normal management and husbandry conditions throughout the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available under Excel table at reasonable demand to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Auteurs would like to acknowledge Mr Makhanov Otemis and Mr Makhanov Talgat camel breeders for their kind cooperation and availability.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors GK, ZB, NA, ZM, FA, ZK and DU, although they are working fully or partially in private company LLP-Antigen declare to have never received personal grants from funding agencies, to be supported from commercial sources of funding by companies, to get honoraria for speaking at symposia or to hold a position on advisory board. Moreover, no patent is expected.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABZSO |

Albendazole Sulfoxide |

| ABZSO2 |

Albendazole sulphone |

| ALB |

Albendazole |

| ACN |

Acetonitryl |

| HPLC |

High Pressure Liquid Chromatography |

| IVM |

Ivermectin |

| LOD |

Limit of Detection |

| LOQ |

Limit of Quantification |

| LRE |

Linear Regression Equation |

| LW |

Life Weight |

| MRL |

Maximum Residue Limit |

| NH2ABZSO² |

Albendazole 2-Aminosulphone |

References

- Mouldi, S.M.; Olfa, B.T.; Najet, Z.; Imed, S.; Touhami, K. Effects of two anthelmintics on gastrointestinal infestation by parasitic worms in camels. Emir. J Food Agric. 2015, 27, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.I.; Azhar Maqbool, A.M.; Anjum, S.; Kamran Ashraf, K.A.; Khan, M.S.; Shah, S.S.; Sabila Afzal, S.A. Efficacy of ivermectin against sarcoptic mange in camel. Pakistan J. Zool. 2016, 48, 301–302. [Google Scholar]

- Darwish, A.A.; Eldakroury, M.F. The effect of ivermectin injection on some clinicopathological parameters in camels naturally infested with scabies. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2020, 8(s2), 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, S.; Aregawi, W.G.; Fekadu, G.; Beksisa, U.; Juhar, T. Commonly Used Anthelmintics Efficacy against Dromedary Camel Gastrointestinal Parasites at Amibara, Afar Region, Ethiopia. In: Livest. Res. Res., F. Feyissa, G. Kitaw, T. Jembere (Eds), EIAR Publ., Adiis-Abeba, Ethiopia, 2021, 9, 38–47.

- Ait El Alia, O.; Zine-Eddine, Y.; Chaji, S.; Boukrouh, S.; Boutoial, K.; Faye, B. . Global camel milk industry: A comprehensive overview of production, consumption trends, market evolution, and value chain efficiency. Small Rumin. Res. 2025, 243, 107441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, B.; Corniaux, C. Le lait de chamelle au risque de l’économie politique : de l’économie du don à l’économie marchande. Rev. Elev. Méd. Vét. Pays Trop. 2024, 77, 37263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifschitz, A.; Pis, A.; Alvarez, L.; Virkel, G.; Sanchez, S.; Sallovitz, J.; Kujanek, R.; Lanusse, C. Bioequivalence of ivermectin formulations in pigs and cattle. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Therap. 1999, 22, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utemuratova, D.; Konuspayeva, G.; Kabdullina, Z.; Akhmetsadykov, N.; Amutova, F. Assessment of milk biosafety for the content of antiparasitic drugs used for human consumption in different countries. In BIO Web of Conferences, EDP Sciences, 2024, 100, 02034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoumi, M.; Hidane, K.; Bengone-Ndong, F.; Alvinerie, M. Short Communication Pharmacokinetics of Eprinomectin in Plasma and Milk in Lactating Camels (Camelus dromedarius). Vet. Res. Comm. 2007, 31, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, P.S.; Cruz, J.F.D.; Santos, J.S.D.; Mottin, V.D.; Teixeira, M.R.; Souza, J.F. Ivermectin and albendazole withdrawal period in goat milk. Rev. Brasil. Saúde Prod. Anim, 2019; 20, e0112019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedziniak, P; Olejnik, M; Rola, J. G; Szprengier-Juszkiewicz, T.). Anthelmintic residues in goat and sheep dairy products. J. Vet. Res. 2015; 59, 515–518. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Paniagua, E; Álvarez-Fernández, L; Rodríguez-Alonso, A; Millán-Garcia, A; Álvarez, A.I; Merino, G.. Role of the Abcg2 transporter in secretion into milk of the anthelmintic clorsulon: interaction with ivermectin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e00095-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiboukis, D; Sazakli, E; Jelastopulu, E; Leotsinidis, M. Anthelmintics residues in raw milk. Assessing intake by a children population. Polish J. Vet. Sci, /, 2013; 16, 85–91. [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, F; Sallovitz, J; Lifschitz, A; Lanusse, C. Determination of ivermectin and moxidecin residues in bovine milk and examination of the effects of these residues on acid fermentation of milk. Food Addit. Contam. 2002, 19, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobato, V; Rath, S; Reyes, F.G.R. Occurrence of ivermectin in bovine milk from the Brazilian retail market. Food Addit. Contam. 2006, 23, 668–673. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L; Du, S; Wu, X; Zhang, J; Gan, Z. Analysis, occurrence and exposure evaluation of antibiotic and anthelmintic residues in whole cow milk from China. Antibiot, 2023; 12, 1125. [CrossRef]

- De Liguoro, M; Longo, F; Brambilla, G; Cinquina, A; Bocca, A; Lucisano, A. Distribution of the anthelmintic drug albendazole and its major metabolites in ovine milk and milk products after a single oral dose. J. Dairy Res. 1996, 63, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvinerie, M; Sutra, J.F; Galtier, P. Ivermectin in goat plasma and milk after subcutaneous injection. Vet. Res. 1993, 24, 417–421, https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/2s2y0f2.

- Romero, T; Althaus, R; Moya, V. J; del Carmen Beltrán, M; Reybroeck, W; Molina, M.P. (2017). Albendazole residues in goat's milk: Interferences in microbial inhibitor tests used to detect antibiotics in milk. J. food drug anal, 2017; 25, 302–305. [CrossRef]

- Porto Filho, J. M; Costa, R G; Araújo, A.C.P; Albuquerque, E.C; Cunha, A.N; Cruz, G.R.B.D. Determining anthelmintic residues in goat milk in Brazil. Rev. Brasil. Saúde Prod. Anim, 2019, 20, e04102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passantino, A; Russo, C; Passantino, L; Conte, F. Ivermectin residues in milk of lactating donkey (Equus asinus): current regulation and challenges for the future. J. Verbrauch. Lebensmitt. 2011, 6, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oukessou, M; Toutain, P. L; Galtier, P; Alvinerie, M. Etude pharmacocinétique comparée du triclabendazole chez le mouton et le dromadaire. Rev. Elev. Méd. Vét. Pays Trop 1991, 44, 447–452. [CrossRef]

- Oukessou, M; Berrag, B; Alvinerie, M. (1999). A comparative kinetic study of ivermectin and moxidectin in lactating camels (Camelus dromedarius). Vet. Parasitol. 1999, 83, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, L; Imperiale, F; Mottier, L; Alvarez, L; Lanusse, C. Comparison of milk residue profiles after oral and subcutaneous administration of benzimidazole anthelmintics to dairy cows. Analyt. Chim. Acta, 2005; 536, 91–99. [CrossRef]

- Fletouris, D.J; Botsoglou, N.A; Psomas, I.E; Mantis, A.I. Albendazole-related drug residues in milk and their fate during cheesemaking, ripening, and storage. J. food Protec. 1998, 61, 1484–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperiale, F; Lanusse, C. The pattern of blood–milk exchange for antiparasitic drugs in dairy ruminants. Animals, 2021; 11, 2758. [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, D.R; Steel, J. W; Lacey, E; Eagleson, G.K; Prichard, R.K. The disposition of albendazole in sheep. J Vet. Pharmacol. Therap, 1989; 12, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, S. F; Alvarez, L. I; Lanusse, C. E. Nutritional condition affects the disposition kinetics of albendazole in cattle. Xenobiotica, 1996; 26, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksit, D; Yalinkilinc, H. S; Sekkin, S; Boyacioğlu, M; Cirak, V. Y; Ayaz, E; Gokbulut, C. Comparative pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of albendazole sulfoxide in sheep and goats, and dose-dependent plasma disposition in goats. BMC Vet. Res. 2015; 11, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Alvinerie, M; Sutra, J. F; Galtier, P; Toutain, P. L., Micro-assay of ivermectin in the dairy cow: plasma concentrations and milk residues. Rev. Méd. Vét, 1994; 145, 761–764.

- Chandler, R. E. Serious neurological adverse events after ivermectin—do they occur beyond the indication of onchocerciasis? . Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 98, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capece, B.P.S; Navarro, M; Arcalis, T; Castells, G; Toribio, L; Perez, F; Carretero, A.; Ruberte, J.; Arboix, M.; Cristòfol, C.. Albendazole sulphoxide enantiomers in pregnant rats embryo concentrations and developmental toxicity. Vet. J. 2003; 165, 266–275.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).