1. Introduction

Water pollution is currently a serious worldwide concern caused largely by the haphazard release of many contaminants originating from industrial, agricultural, and domestic activities [

1]. Industrial wastewater is one of the major contributor because it tends to transport a mix of synthetic chemicals, heavy metals, and organics that cannot be degraded easily [

2,

3,

4]. Pharmaceutical compounds are also frequently detected in both surface water and groundwater due to improper disposal, leading to environmental residues that pose serious concerns [

5,

6]. Moreover, synthetic dyes (textile, leather, printing, carpet, and paper sectors) are also chemically persistent, tend to accumulate in aquatic environments, resulting in several environmental problems and health issues (such as carcinogenic) [

5,

7,

8,

9]. Similarly, the agricultural chemicals can contaminate water bodies and negatively affect aquatic life [

10]. The combined presence of such diverse contaminants has led to complex pollutant mixtures, and many of these so-called emerging contaminants are not yet addressed and continue to raise significant environmental concerns. This alarming trend has prompted extensive research and policy initiatives aimed at mitigating the risks posed by pollutants [

11].

Common treatment methods include aerobic biological treatments, ion exchange, membrane-based separations, adsorption, coagulation, and a range of advanced oxidation process (AOPs) such as photocatalysis, sonolysis, ozonation, electrocatalysis, electro-Fenton, and Photo-Fenton processes [

1,

12]. Conventional wastewater treatment processes are found to be insufficient for the mineralization of recalcitrant contaminants. For example, biological treatments, such as the activated sludge process, rely on microbial degradation but are ineffective against chemically stable or toxic substances that inhibit microbial activity [

13]. Adsorption using activated carbon (AC) can remove some contaminants, but lacks specificity and requires frequent replacement [

14]. Chlorination, although effective against pathogens, can produce harmful byproducts [

8]. These methods face practical challenges, including complex instrumentation, high costs, and significant energy demands, which limit their feasibility.

Among available technologies, AOPs have gained significant attention for their ability to break down persistent organic pollutants. AOPs that generate highly reactive species to drive oxidative degradation of water pollutants have emerged as the most compelling and sustainable alternative to the conventional wastewater treatment methodologies [

15]. Traditional AOPs, including the Fenton process, ozonation, and persulfate-based systems, predominantly rely on non-selective oxidative species, such as hydroxyl and sulfate radicals. Despite the high oxidation potential of these radicals, they suffer from rapid recombination, scavenging by background anions, and limited electron efficiency [

16,

17]. These limitations reduce their effectiveness in real-world water matrices and increase operational costs, necessitating the development of more selective and efficient oxidation strategies.

Recently, high-valent metal-oxo species (HMOS, for example Fe(IV)=O, Fe(V)=O, Mn(V)=O, Co(IV)=O, and Ru(VIII)) have emerged as promising oxidants in next-generation AOPs, owing to their unique reactivity, high selectivity, and resistance to interference [

18,

19,

20]. In contrast to products of radical-based reactions, high-valent metals employ defined, non-radical mechanisms, such as oxygen atom transfer (OAT) and hydride abstraction or electrophilic addition, allowing for the degradation of electron-rich organic functionalities with minimal side products [

21,

22]. For example, Fe(VI) and Fe(V) species generated in Fe(VI), or Fe(II)-dependent systems have been shown to oxidize sulfonamides, phenols, and antibiotics like sulfamethoxazole (SMX), notably over a wide pH range [

23,

24]. Similarly, Co(IV) formed in Co(II)/peroxymonosulfate (PMS) systems is thus described to demonstrate greater oxidation power in comparison to Fe(IV) due to its larger redox potential and stability towards acidic-neutral conditions [

25,

26,

27]. The experiments have been carried out on several catalytic systems in which the high-valent metals have been detected in the Fe(II)/peracetic acid (PAA), Co(II)/PAA, Fe (II)/periodate and Mn (II)/ PAA systems by the utilization of characterization methods like EPR (electron paramagnetic resonance), XAS (extended X-ray absorption spectroscopy), and isotopic labelling (18O) [

21,

28,

29,

30]. Cu(III)-mediated oxidation reactions exceeded the performance of small radical-dominated systems (27% Co

3O

4/PMS and 26% 1O

2) and showed an unrivalled electron efficiency of high-valent metal pathways and used 77% of the available electrons to mineralize contaminants [

18,

31,

32]. This efficiency can be further boosted in the non-radical systems where direct electron transfer between pollutants and the catalyst/oxidant occurs, and hence energy is not lost easily [

26].

Among these beneficiaries, high-valent metal species, which are produced in a controllable way, are stabilized and scalable in use, and are the key setbacks. Limited life times, pH sensitivity, and metal leaching vulnerabilities, especially in homogeneous systems, reduce the practical applicability of such systems in the long term [

20]. In the attempt to solve these problems, in recent years, considerable efforts have been devoted to the study of heterogeneous catalysts: metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), transition metal sulfides (TMSs), and single-atom catalysts (SACs), which could be more stable and easier to reuse, and accessible to active sites [

33,

34]. The development of multiple approaches has been used to generate and stabilize the high-valent states in the form of defect engineering, ligand modulation, and electrochemical regeneration, allowing prolonged catalytic cycles to operate [

20]. In addition to breaking down pollutants, high-valent metal-based AOPs support the idea of circular chemistry. They help separate heavy metals from organic complexes, making it possible to both remove contaminants and reuse heavy metals in industrial wastewater management processes [

35]. Moreover, the possibility to filter these systems allows transforming waste organics into value products according to the principles of green synthesis and upcycling wastes [

21,

36]. The amount of literature on high-valent metal-based systems and persulfate indicates widespread research on high-valent metal-based AOPs. Up to the present, there are few studies that examine the overall study of the high-valent metal applications in the treatment of water and circular chemistry [

21].

The current review provides a new insight into the high-valent metal-oxo species and their use as not only strong oxidants but as dynamic catalysts in closed-loop reagent cycles. Unlike the previous reviews that tend to separate the reaction mechanisms and environmental applications as distinct fields, this one fills the gaps by integrating the knowledge of coordination chemistry, catalyst design, and green engineering. The article presents a comprehensive review of the recent advancements in the mechanism of formation, reaction pathways, catalytic and environmental utilization of high-valent metals in AOPs, with a vision towards scalability, sustainability, and integration into the circular water economy. It defines a new classification scheme for hybrid AOPs, provides an extensive comparison of metal species redox behavior, and connects how these processes may contribute towards the advancement of circular water treatment strategies. By incorporating emerging approaches such as machine learning, Nano engineering, and bioinspired materials, the review points toward promising directions for future research. It aims to serve as a valuable resource for advancing interdisciplinary solutions in water purification and environmental remediation.

2. Advancing High-Valent Metals in AOPs: From Oxidants to Reaction Mediators

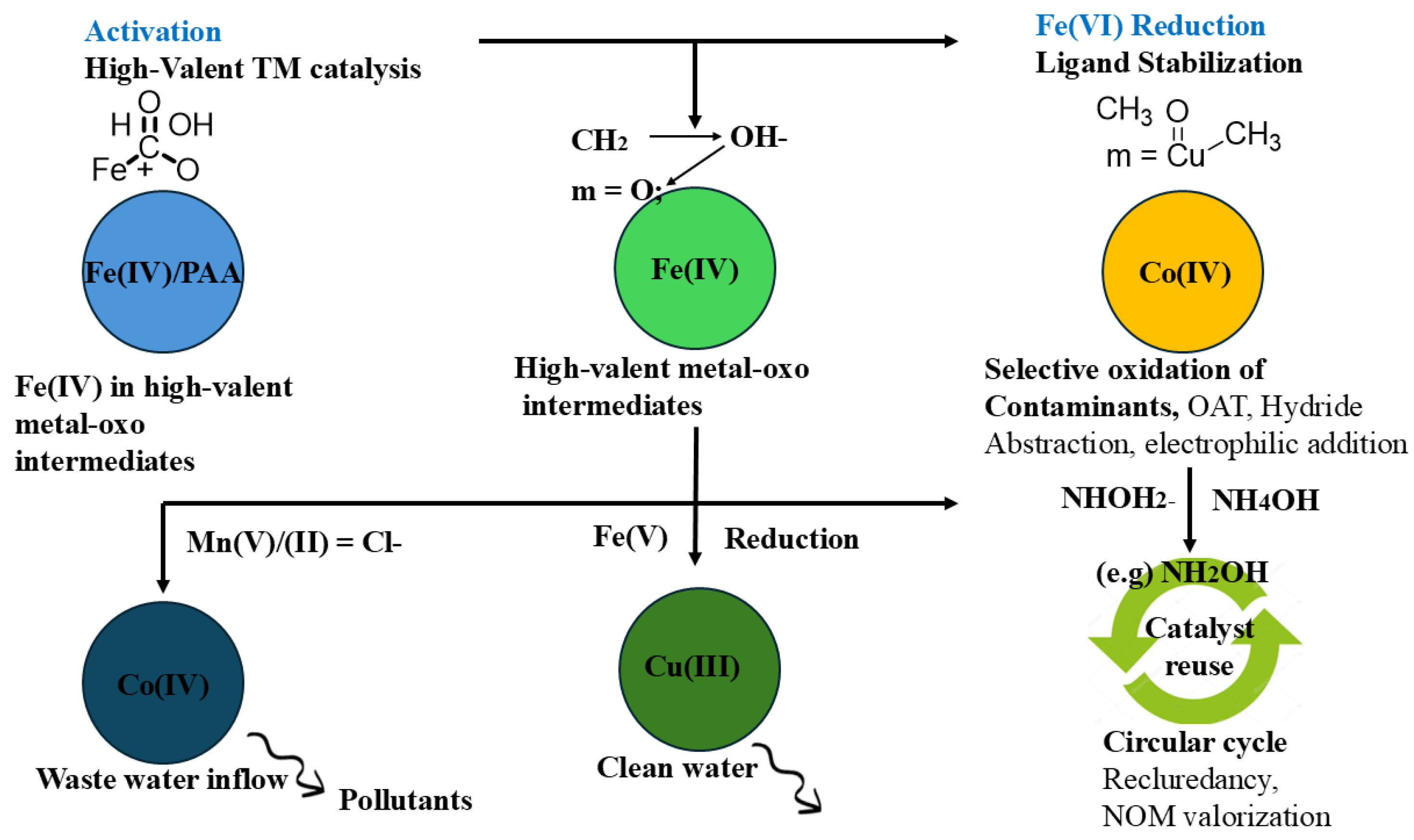

Traditionally, reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydroxyl (•OH) and sulfate (SO₄•⁻) radicals have been recognized as the major species for the degradation of pollutants in wastewater. Recent findings indicate that the catalytic cycles are guided by the presence of the high-valent metal-oxo species, such as Co(IV), Mn(V), Fe(VI), and Ru(VIII), which increases efficiency and selectivity through the oxidative conversion reactions [

18,

21]. The pollutants degradation of through high-valent transition metal-oxo species is illustrated in

Figure 1, showing the activation, transformation, and reduction steps involving Fe(IV), Co(IV), and Cu(III) intermediates. The figure also shows catalyst stabilization and the reuse mechanisms which promote a circular and sustainable process of water treatment. The interesting features that possess, being electronically only, and redox reversible, modified them into their up-to-date role of the mechanistic mediators of the advanced oxidation process. Fe (VI) is no exception and in that regard will demonstrate to be a dual functional reagent in wastewater treatment with respect to coagulant behavior and strong oxidant behavior as its standard reduction potential is in the range of ~0.7-2.2 V which will be varied with respect to pH [

21,

37]. Fe(VI) generates reactive intermediates, i.e., Fe(V) and Fe(IV), which are spectroscopically confirmed by using the X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES), as it recovers stepwise [

23,

29]. These intermediate products are not simply byproducts but are crucial elements in the redox cascade to provide extra oxidative potential and enhance the efficiency of electron use. Here, Co(IV), which generates during the activation of PMS has greater redox potential than Fe(IV) and offers excellent performance in C-H bond activation and OAT reactions, as well as oxidation of recalcitrant organic compounds, especially for the activation of dysfunctional C-H bonds that are commonly a bottleneck step in the degradation of known pollutants in the environment [

19,

31,

38].

Recent research points out that the least frequently reported, Mn(V) and Ru(VIII) species, is the most selective and stable compared to the other species in terms of selectivity and stability. The Mn(V)=O species generated in the Mn(II)/per acetic acid (PAA) systems have been detected using the labeling experiments with 18O. The Mn(V) species are highly electrophilic and react most readily with highly electron-rich contaminants (phenols and sulfonamides) [

21,

39,

40]. Ruthenium in its highest oxidation state (Ru(VIII), typically in the form of RuO₄), exhibits strong oxidative power and has been explored for AOPs. Although the standard reduction potential of RuO₄ is typically reported around +0.59 to +1.4 V vs. SHE, depending on the specific redox couple-conditions, RuO₄ remains a potent oxidant capable of degrading and mineralizing persistent organic pollutants under mild aqueous conditions [

41]. The strong oxidation characteristics of this metal have rendered it a candidate for electrochemically driven (AOPs for total mineralization of contaminants such as endocrine-disrupting compounds and pharmaceuticals, even at modest potentials). In addition, its high-valent states have been stabilized via ligand engineering and coordination on a site in SACs where the localized electronic environment changes the distinct character of the metal to prevent over-oxidation or decomposition [

42].

The catalytic systems that regenerate Cu(IV) or Fe(VI) species through an electrochemical procedure, such as iodosyl benzene, are described as catalytic systems in the recent patents and allow the system to function in a closed-loop way, while reducing chemical consumption. For example, a low-concentration (traces of Cu(II)) show a unique ability to increase Fe(III)/PMS systems through regeneration of Fe(II) to promote the generation of Fe(IV) and catalytic turnover [

43]. These synergetic effects highlight the transformation of high-valent metals from stoichiometric oxidants to more dynamic, cycle-stabilizing catalysts proficient of catalyzing complex mechanistic pathways.

This emerging field fits well within two principles of green chemistry atom economy, and energy efficiency. High-valent metal uses of oxidants in comparison to traditional radical-based AOPs due to less slow radical pathways and faster direct electron transfer. For example, it has been shown that Cu(III) processes reach about 77% oxidant consumption, while radical-based AOPs like Fenton's operate around 15% effectiveness [

32,

44]. A comparison of redox potentials, times, mechanisms of action, and competences of electron transfer of Co(IV), Mn(V), Fe(VI), and Ru(VIII) across diverse oxidant systems (PMS, PAA, and periodate) can be found in

Table 1. The recent importance in AOPs research has increased investigations away from synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of high-valent species to engineering their catalytic efficiency. This transition of high-valent metals from oxidants to mechanistic mediators offers possibilities for efficient and sustainable wastewater remediation technologies.

3. Emergent Synthesis Pathways for Stable High-Valent Metal Complexes

Metal species of high-valence like Fe(IV), Co(IV), Mn(V), and Ru(VIII) are unstable and short-lived species in AOPs, limiting their practical use. The species are thermodynamically potent; their issue is generally restricted, minute catalytic turnover, little oxidative power because of rapid auto-decomposition, over-reduction or hydrolysis in aqueous solvents [

18,

29]. Many of these challenges have been overcome through new approaches to synthetic chemistry, employing novel binders that stabilize high-valent species through precise coordination of chemistry, and stabilize such species with operationally relevant conditions of chemistry.

Recent synthesis of the ligands of polydentate nitrogen and oxygen donors has been mentioned to be a breakthrough where the high-valent metals are thermodynamically and kinetically stabilized. Tetra amido macrocyclic ligands (TAMLs), pentadentate N-bases ligand (N4Py and Bn-TPEN), and N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands have been reported to destabilize the dimers, but stabilize the Fe(IV)=O and Mn(V)=O species by altering electron density and degradation by a particular solvent [

50,

51,

52,

53]. Tetradentate N-donor ligands stabilized Fe(IV)=O complexes were reported to have greater oxidation potential to degrade pollutants than their ligand-free counterparts, since they were more stable with long lifetimes in aqueous media [

54]. In a parallel fashion, Co(IV) species formed in Co(II)/PMS systems are stabilized by interaction with nitrogen atoms of pyridine and graphite within the nitrogen-doped carbon matrices, which increases electron mobility and suppresses metal leaching [

47].

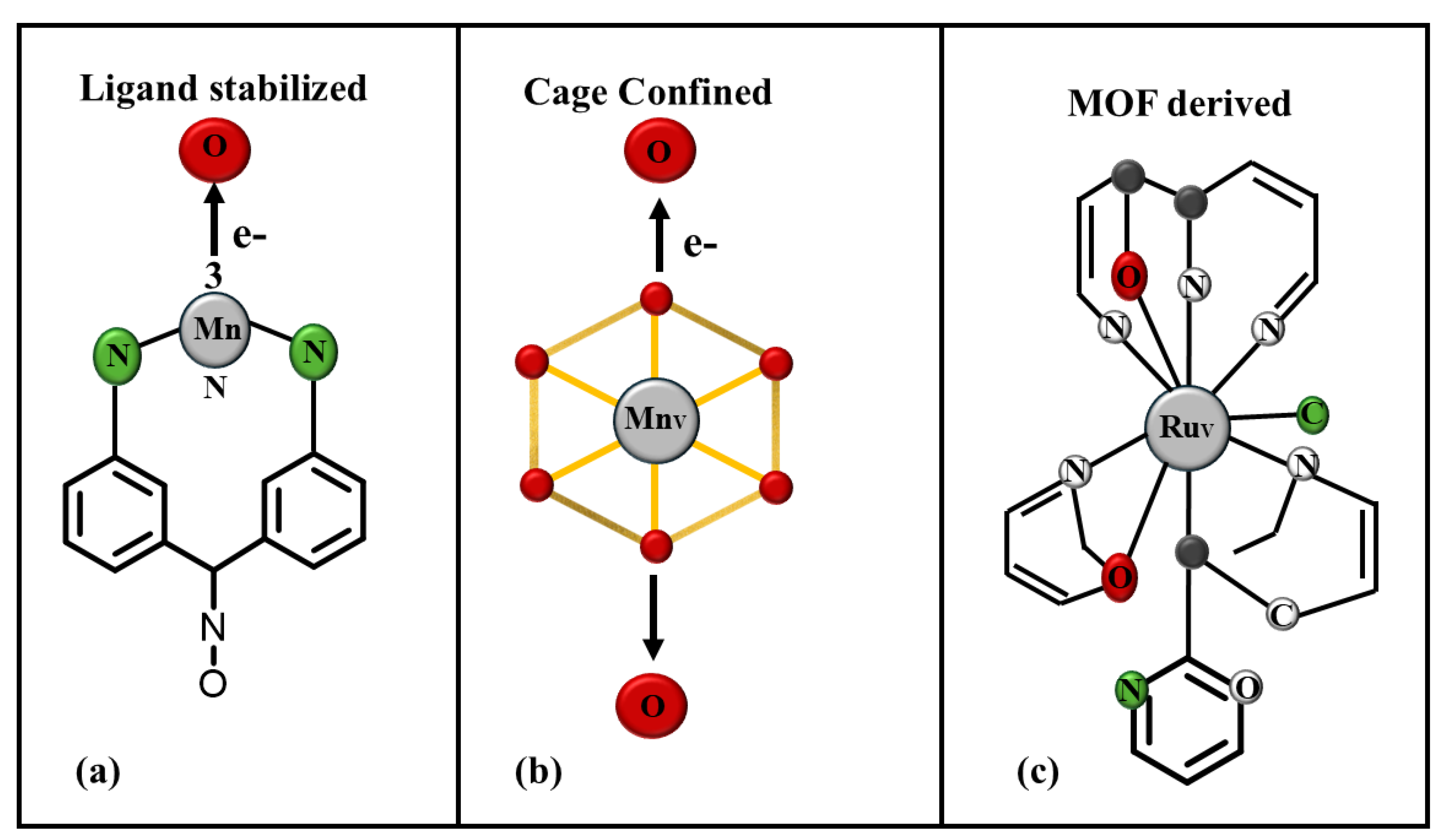

MOFs, self-assembled cages, and supramolecular structures are also becoming potentially useful materials to trap and stabilize high-valency compounds. The well-defined cavity and tunable environments in these structures exclude bulk free water and other competing nucleophiles from the reactive metal-oxo centers and their accessibility. Various MOF-based materials, including pristine MOFs (e.g., ZIF-67, MIL-53(Fe), MIL-88A(Fe)) and MOF-derived structures (e.g., FexCo₃−ₓO₄ nanocages, Co@C nanoboxes), have been used as catalysts in sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes (SR-AOPs) for wastewater treatment. Their porous structures enhance mass transfer and pollutant removal, while spatial confinement helps reduce metal ion leaching compared to traditional catalysts [

55]. XAS studies in situ prove the stability of Fe(IV)=O clusters in the MOF matrices under conditions of PAA activation, and therefore show the stabilizing capability of the crystalline framework [

21]. The

Figure 2 compares three types of SAC architectures, ligand-stabilized, cage-confined, and MOF-derived, illustrating their distinct coordination environments and electron transfer pathways for generating high-valent metal species. These structural variations play a very important part in the catalytic activity and stability of the metal centers.

In addition, the second avenue to heterogeneous stabilization of the high-valence states is the SACs which are prepared via a pyrolysis pathway. These materials can embed isolated metal atoms (Fe, Co, and Mn) into nitrogen-doped carbon lattices prepared with MOF-precursory units to afford robust M = N4 coordination sites that permit persulfate or PAA activation to develop or sustain M(n + 2)=O higher-valence species [

56]. The heterolytic O-O Bond cleavage of oxidants such as PMS is encouraged by the electron-pulling character of the carbon matrix that leads to a preference for two-electron transfer processes that produce higher valent metal oxo species rather than radicals [

57].

A fundamental missing link here is that no systematic review has so far correlated the structural stability of the synthetic high valency complexes, which were quantified by lifetime, turnover frequency (TOF), and coordination number, with their performance characteristics in AOPs, including the rate of contaminant decay, the efficiency of oxidant utilization, and sensitivity to matrix effects. The current state of ligand and framework design has enhanced stability, but molecular-level controllability remains unrealizable to scale in energy-efficient water treatment processes because of an absence of structure-activity relationships (SARs). Although stabilized Fe(IV) in TAML systems demonstrates great reactivity with phenols, the method reported for its synthesis is carried out through multi-step organic pathways with low atom economy, which opens up the possibility of concerns over cost and environmental impact [

54].

Future work needs to fill the gap between synthetic chemistry and environmental engineering to provide predictive models that deliver ligand denticity/metal spin state/coordination geometry to AOP efficiency. Combining computational screening (DFT predicted redox potentials) with high-throughput experimental validation may both improve the pace at which next-generation stabilizing matrices, including bioinspired porphyrinoids or microbially produced ligands, can be discovered that balance reactivity, durability, and sustainability [

21].

4. Synergistic Hybrid AOPs: Integration of High-Valent Metals with Photocatalysis, Sono-Catalysis, and Fenton-like Systems

The quest to have efficient, scalable, and sustainable water remediation technologies has given rise to the creation of hybrid AOPs in which high-valent metal species are deliberately combined with complementary sources of energy (light, ultrasound, or electrochemical potential). These synergistic systems overcome these constraints of standalone AOPs by promoting high-valent metal-oxo reagent generation, stability, and reactivity (Fe(IV), Mn(V), and Co(IV)) as well as effecting enhanced oxidant utilization and reducing secondary pollution [

18,

58]. The recent developments have made it important to recategorize the hybrids AOPs in terms of the type of activation mechanism and the characteristics of high-valent metal participation, therefore generating a new categorization system [

59].

4.1. Proposed Three-Tier Classification Framework

4.1.1. Type I (Photo-Enhanced)

The energy input generated by the photocatalysis process is used to drive the flux of electrons (g-C

3N

4, TiO

2, MoS

2) to metal centers and enhances the regeneration of the low-valent metal state (e.g., Fe(II), Co(II), etc.) and continues the cycle of catalysis in the synthesis of high-valent species. As an example, photoexcitation electrons of a GO/g-C

3N

4/MoS

2 composite system can be used to reduce Co(III) to Co(II) to activate PMS to produce Co(IV)=O and improve the degradation of SMX with visible light to a great extent [

60]. In this type of heterojunction, the charge carriers are spatially separated, which inhibits charge recombination, boosting quantum efficiency and making functioning under solar irradiation possible.

4.1.2. System Type II (Sono-Catalytically-Driven)

It uses ultrasound to create localized hot spots (>5000 K) and micro turbulence, in order to accelerate homolytic cleavage of oxidants (represented by H

2O

2 PAA) and increase mass transfer to the catalyst surfaces. Sonolysis has been found to increase the rate of formation of Mn(V)=O species in Mn(II)/PAA systems, largely by enhancement of ligand exchange and accommodation of transient intermediates [

21]. The degradation of bisphenol A was unusually high (98% in 30 min) in a hybrid sonolysis/Fenton/UV system, as compared to any single technique, because of both concomitant •OH generation and formation of Fe(IV) under ultrasonic cavitation [

61].

4.1.3. Systems Type III (Multi-Oxidant Fenton-Like)

They are the most modern category, where multiple chemical oxidants (e.g., H

2O

2, PMS, and PAA) can be combined with Fenton-like catalysts to discriminate between high-valent metal pathways and radical pathways. As one case in point, the Fe(II)/PAA system produced Fe(IV) through the mode of a nucleophilic attack, whilst the addition of PMS changed the prevailing mode to producing Co(IV) or Fe(IV), based on the catalyst blend used [

62]. In particular, such systems can take advantage of tunability in reaction selectivity: high-valent metals will oxidize electron-rich contaminants (e.g., phenols, anilines), leading to fewer toxic halogenated byproducts that are abundant in processes based on radical chemistry [

63].

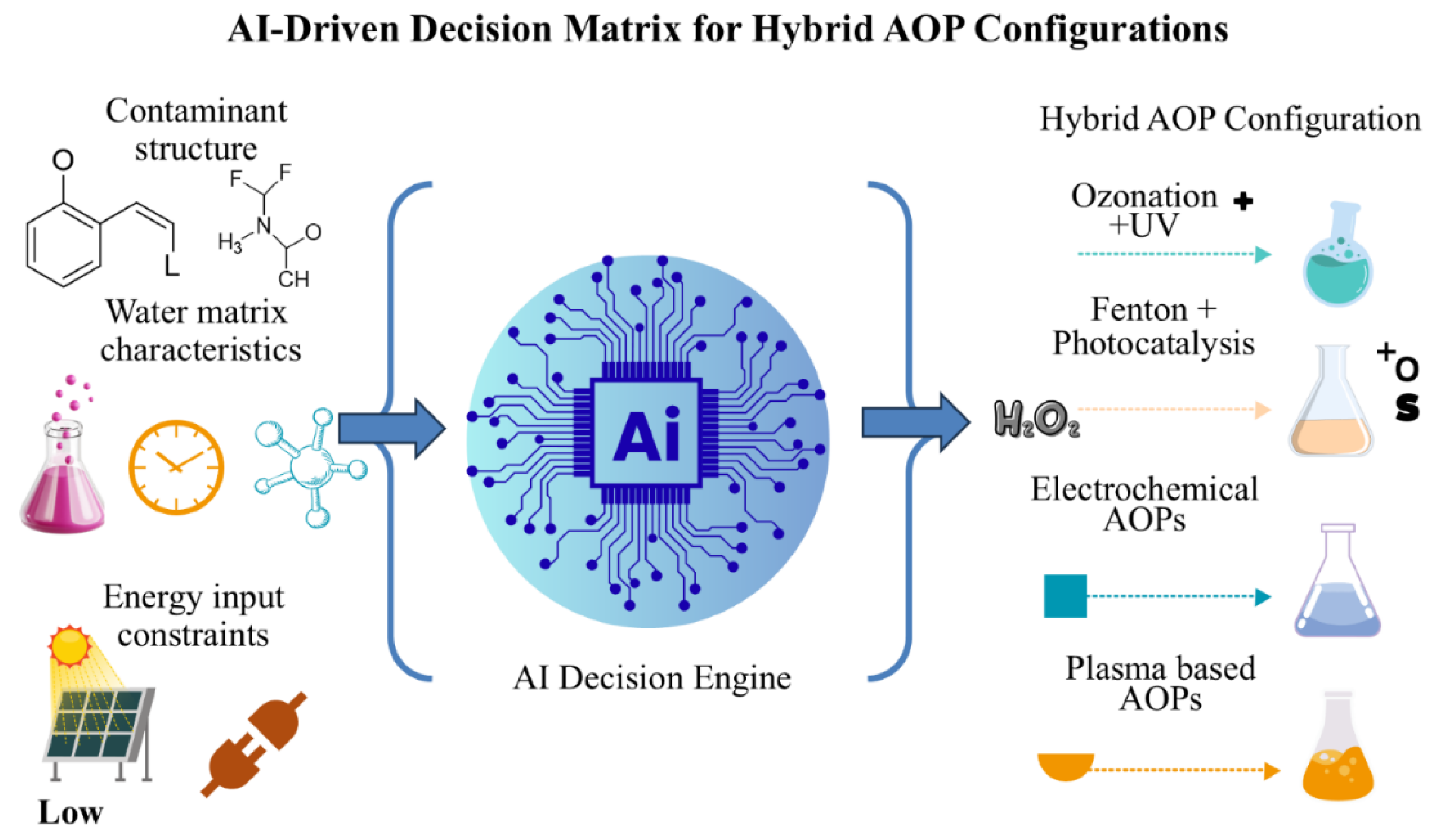

A new technology is using artificial intelligence (AI) to optimize the catalyst-oxidant pairings and parameters of operation. Machine learning (ML) models trained using descriptors derived by DFT (e.g., d-band center, oxidation potential, coordination number) have begun to predict suitable combinations (CoCu

10/PMS or FeS

2/PAA) to pollutants with exceptional accuracy, in combination with experimental kinetics [

64].

Figure 3 represents the AI-based decision matrix that is used to pick the best hybrid AOP settings, depending on the structure of contaminants, characteristics of water matrices, and energy input limitations. The method allows the development of custom treatment plans as it combines both data-driven and sophisticated oxidation technologies.

Nonetheless, there are problematic aspects of hybrid AOPs that include energy demand and toxic byproducts. Whereas high-valent metal pathways are more efficient as far as electron efficiency goes (77% in Cu(III)-based systems), the total energy consumption in hybrid systems (especially UV or ultrasound-based) may be cost-prohibitive on scale [

65]. Also, partial mineralization has the potential to cause the buildup of transformation products whose ecotoxicity is unknown. Partial oxidation may turn out to be more persistent and genotoxic intermediates when compared with the parent compound, such as sulfonamide antibiotics [

35]. Thus, the development in the future should include life-cycle assessment (LCA) and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) as a live by-product analytical technique.

The influencing factor on next-generation hybrid AOPs must be high-valent metal catalysis, which integrates with renewable energy and closed-loop oxidant regeneration to achieve maximum sustainability.

Table 2 shows comparisons of energy consumption (kWh/m

3), mineralization points (% COD removal), and toxicity decrease (through bioassays) in a sample of hybrid systems.

5. Synergistic Hybrid AOPs

Although increasingly well understood, the chemical and biological reactivity of high-valent metal species in AOPs is often accompanied by a much less well-studied area of post-reaction environmental fate. An in-depth view into the transformation pathways, stability, and final speciation of these species following electron transfer is crucial in determining the sustainability of these species for catalytic applications, as well as potential environmental hazards [

18,

19,

21]. The rich redox cascades that mediated reducing high-valent metals differ fundamentally, in structure, reactivity, and duration, from the persistent radicals or non-degradable organic pollutants to which they are often compared, and the consequences of these transformation products in the environment are scarcely mentioned in existing literature.

Once oxidation products of target contaminants are formed, high-valent metal ions are reduced by one-electron or 2-electron transfer pathways in the formation of lower-valent metal ions and hydrolysis products. As an example, Fe(VI) is reduced successively to Fe(V), then Fe(IV), and finally Fe(III), which then can hydrolyze to form Fe(OH)

3 or ferrihydrite in neutral and higher pH environments [

39,

72]. Such Fe(III) (oxy)hydroxides are not inert waste products and have much coagulation capability and can adsorb or precipitate inorganic anions (phosphate, arsenate) and colloidal organic matter, thus helping clarify the water [

71,

73]. Such dual capability has nevertheless brought about an appreciable balancing act: as much as there are the advantages of Fe(VI), having combined coagulation and oxidation advantages [

74], there are secondary water quality issues to consider: such as the resulting turbidity and increment of iron residuals, and even potentially troublesome byproducts created by the oxidation of the Mn(II): Mn(III), and so on [

39].

Correspondingly, Mn(V) species can be produced in Mn(II)/periodate systems or Mn(II)/PAA systems, and quickly reduced to Mn(III) and Mn(II), and the Mn(III) is frequently stabilized by organic ligands, including nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) or pyrophosphate [

46,

75]. Whereas the major form, Mn(II), is comparatively non-toxic and naturally commonplace in the aquatic environment, the intermediate, Mn(III), can act as a powerful oxidant or reductant depending on the surroundings, which could lead to redox cycling in other substances, such as Fe and C. Furthermore, there are long-term exposure bioavailability concerns over the mobilization of Mn oxides in sediments that could be a source of neurotoxicity in drinking water supplies and animal feeds if forms of Mn oxides are disproportionately converted to Mn(III) during formation under field conditions [

76]. Unanswered but critical is how the reduced metal species could be well recycled or regenerated in functional systems. Recent work indicates that electrochemical/chemical re-oxidation of Fe(III) to Fe(VI) is likely on anodic electrodes (e.g., Ni-Sb-SnO

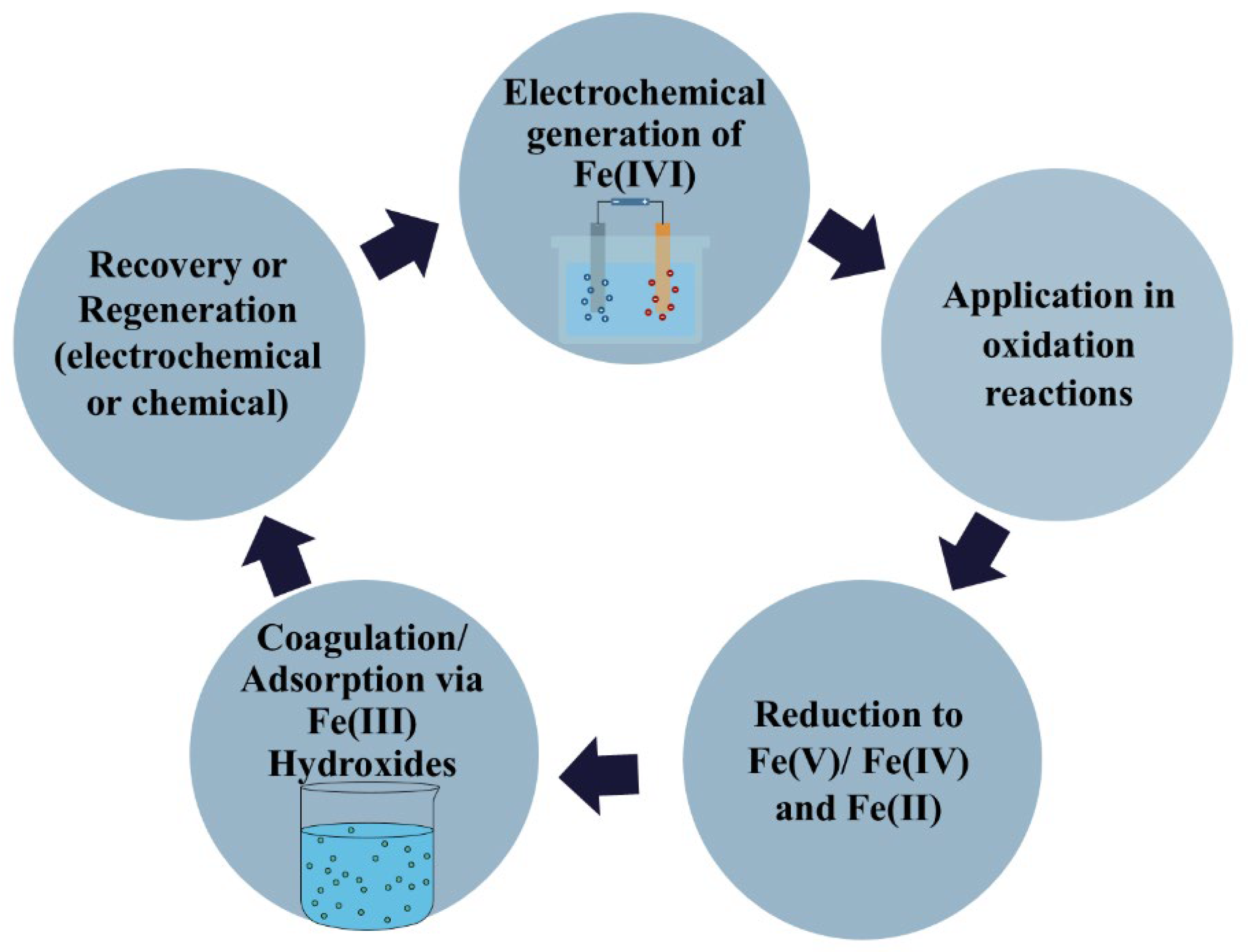

2), which provides a route to catalytic closure [

77].

Figure 4 demonstrates the life cycle of Fe(VI), early at electrochemical generation, its usage in oxidation, coagulation, and possible renaissance. This kind of process is energy-intensive and is still limited to laboratories.

Additional complexities of the environmental fate of the high-valent metals are associated with the interaction with natural organic matter (NOM) and real wastewater matrices. NOM is both a scavenger and a reductant that can accelerate the bacterial decay of Fe(VI) and Mn(V) by way of donating electrons [

21,

78]. While this may reduce the concentration of highly oxidizing species to degrade target pollutants, it is also representative of a natural attenuation process that would also constrain the species in the environment. Radicals (•OH) are typically considered non-selective, whereby reactions take place with halides and NOM simultaneously producing toxic halogenated by-products, whereas high valent metals have more selectivity and are less likely to produce hazardous intermediates, improving environmental compatibility [

18,

27].

Even though the resist durability, the bioaccumulation of residual metal ions, especially Co(II) and Cu(II), could be taken seriously. As a result, future research will need to combine ecotoxicological measurements with material flow analysis to differentiate between catabolically recycled metals against effluent-derived metals. Synthesizing the above, the environmental fate of high-valent metals is beyond the oxidative activity to post-reduction speciation, phenomena of coagulation, as well as regeneration. To promote their sustainable use in the treatment of water, a comprehensive perspective that would combine reaction chemistry and the environmental impact is crucial.

6. Synergistic Hybrid AOPs

Enhancing circular water-energy systems with AOPs is a paradigm shift in both processes, or product-oriented (scarcity-based) treatment to resource-recovery-based treatment. High-valent metal-mediated AOPs, which are catalyzed by species including Fe(IV), Mn(V), and Co(IV), are well-suited to drive this paradigm shift because of their rigor and selectivity, stability in complex matrices, and dual-function versatility with respect to oxidation of the contaminant as well as the synthesis of a co-product [

21,

79,

80]. In contrast to typical conventional radical-based pathways, whereby organics are mineralized blindly via the production of CO

2 and H

2O, high-valent metal mechanisms typically occur via controlled, step-wise oxidations in which functional groups are preserved, and hence the possibility to recover valuable intermediates or otherwise recycle waste streams.

The formation of recoverable forms of inorganic metal and oxidized organic ligands by complexification and conversion of heavy metal-organic complexes, which are ubiquitous in industrial effluents (e.g., tannery effluents, electroplating effluents, and pharmaceutical manufacturing effluents), constitutes one of the primary benefits of high-valent metal AOPs [

18,

35]. As an example, Cr(III)-organic complexes comprising more than 60% of chromium in tannery wastewater and highly recalcitrant to conventional treatment, may be broken down effectively through Fe(VI) or Mn(V) mediated oxidation to free Cr(III) that can then be precipitated and reused [

21]. Equally, degradation of EDTA- or citrate-complexed Cu(II) removes the organic ligand, and produces bioavailable Cu

2+, which is recoverable by electrochemical deposition or adsorption [

35]. This dual approach is in line with green chemistry postulates and principles by transforming hazardous waste into reusable material.

In addition to metal recovery, high-valent metal AOPs may provide a window of opportunity to valorize organic carbon. Specific oxidation of recalcitrant organics-like phenols, dyes, and pharmaceuticals, may produce carboxylic acids or aldehydes or quinones that can be used as chemical feedstocks [

20,

21]. To illustrate, production of low-molecular-weight organic acids such as oxalic acid and acetic acid through partial oxidation of bisphenol. A through Co(IV)=O can unlock the production of energy using microbial fuel cells [

81]. Moreover, the coagulating potential of the Fe(III) hydroxides, produced as the end products of the Fe(VI) reduction reaction, allows the simultaneous removal of nutrients by means of phosphorus precipitation as vivianite or by means of its fixation to iron oxides, which represents a possibility of recovery of nutrients using wastewater [

29].

Closed-loop catalyst management is required to accomplish actual circularity. Although homogeneous systems are difficult to recover, heterogeneous platforms (including SACs, TMSs, and MOF-derived composites) are both highly reusable and have limited leaching. As an example, hierarchical reactors made of Co

3O

4 remain catalytically active and over 90 percent effective even after five cycles in the PMS activation process, exhibiting almost negligible cobalt leaching (<0.1 mg/L), and thus can be used over a long period of time [

69].

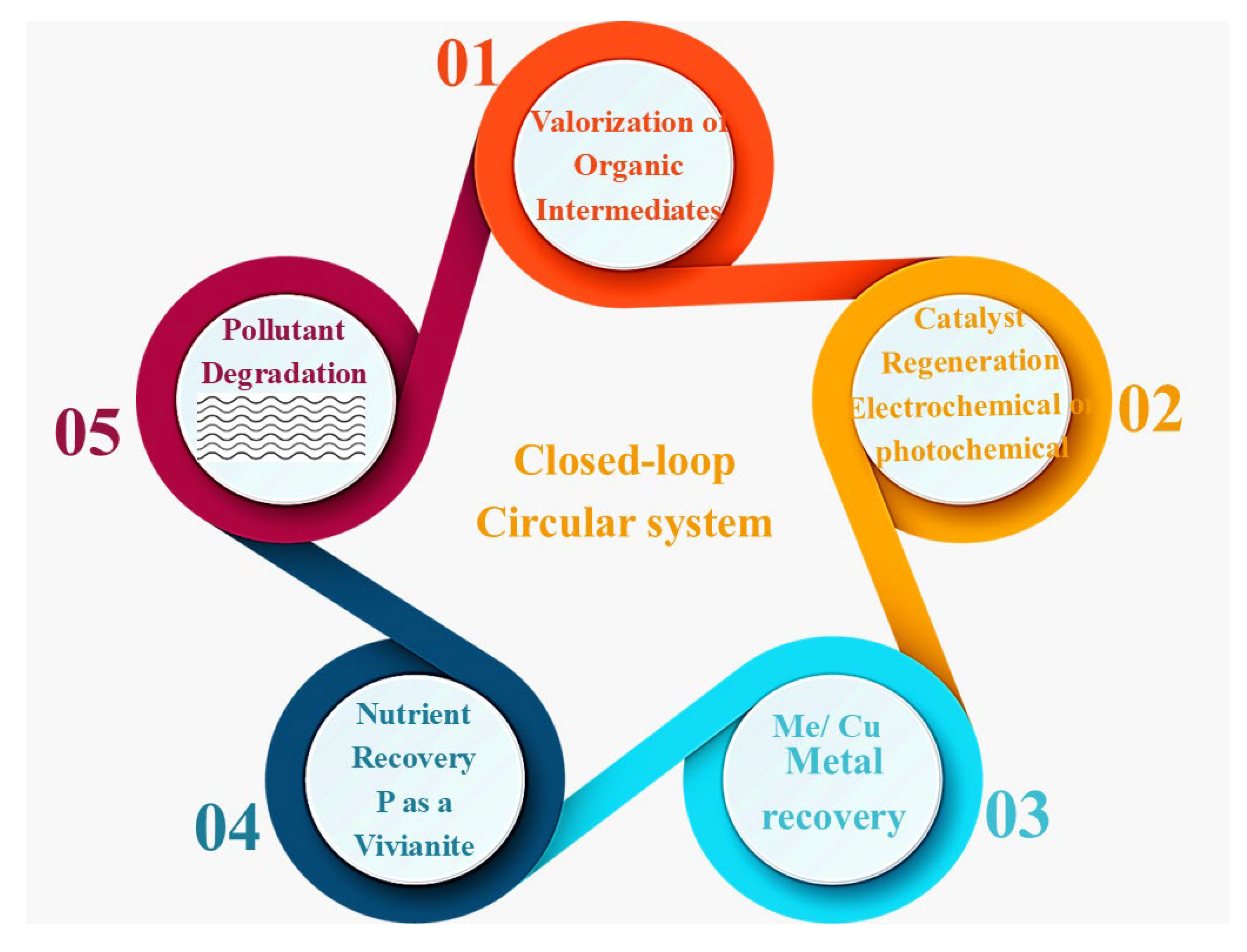

Figure 5 describes a closed-loop circular system that combines the high-valent metal AOPs with catalyst regeneration, recycling of the metal, and valorization of the organic compounds.

SnO₂–Sb-based anodes have emerged as promising materials for electrochemical wastewater treatment due to their high oxidative potential and stability. Recent advances focus on enhancing ROS generation, including O₃ and H₂O₂, through material modification. These electrodes offer scalable, sustainable solutions for degrading recalcitrant organic pollutants in industrial effluents [

82]. Together with renewable energy sources, solar- or wind-driven electrolyzers, this solution enables energy self-sufficient applications in the field of water treatment with a small carbon footprint [

18]. In spite of these breakthroughs, comprehensive deployment does not extend beyond pilot scale due to the absence of pilot scale validation and techno-economic evaluation. The majority of research would be only laboratory-based based on model pollutants, with limited information gathered on mineralization rates, byproduct toxicity and scalability of the process [

21].

7. Challenges

Although high-valent metal-based AOPs show great promise for treating contaminated water, several real-world challenges still stand in the way of their practical use. One major issue is that high-valent metal species like Fe(IV), Mn(V), and Co(IV) are often short-lived and unstable in water. They tend to break down or lose their effectiveness quickly unless carefully stabilized. While techniques like ligand design, supramolecular confinement, and SAC engineering have helped extend their stability, applying these methods at scale is still costly and technically complex. Another hurdle is the balance between selectivity and versatility. These metal-based systems are highly effective at targeting certain types of pollutants, particularly electron-rich ones, but may struggle to degrade tougher or more water-repellent compounds. In some systems, metal ions, for example cobalt or copper, can transfer into the water. The presence of these ions can create potential issues for secondary pollution or compliance with environmental regulations. The demand of Energy gives a reason for concern. Characteristically, these approaches depend on numerous types of energy input such as ultrasound, electricity, or UV-light. When using an energy input that is not derived from a renewable source, these contributions not only be expensive, but it can also add to our carbon footprint. Moreover, there are harmful byproducts that can be produced by incomplete pollutants degradation (e.g., aldehydes, quinones) that can be harm to ecological health. Scientifically, the clear research gaps are the absence of clear structure–activity relationships that connect the design of a catalyst to its effectiveness, which based on trial and error and not knowledge-based design, scientists are regularly left to design better systems. Most research studies to-date are still accomplished in laboratory using simple pollutants and controlled environment. There is a clear gap in assessing the efficiency of these systems at pilot-scale in complex real wastewater to know how these systems act in actual. Until these practical, financial, and environmental questions are addressed, the potential of high-valent metal AOPs remains just out of reach.

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

In this section, where applicable, authors are required to disclose details of how generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been used in this paper (e.g., to generate text, data, or graphics, or to assist in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation). The use of GenAI for superficial text editing (e.g., grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting) does not need to be declared.

8. Nano-Engineered, Bioinspired, and Machine-Learned High-Valent Systems

The next-generation high-valent metal based AOPs at the interface of nanoengineering, bioinspired design and AI, will enter a phase where they can be explored and applied beyond an empirical catalyst design, which has been a major approach towards their development. As the limitations of trial-and-error approaches continue to be unveiled, scientists will increasingly embrace approaches that are predictive and rational in nature, thus allowing a much greater control over the generation, stability and reactivity of high-valent redox-active compounds (i.e., Fe(IV)). These developments offer not only improved efficiencies for degradation processes, but also tunable selectivity, reduced energy consumption, and increased scalability to real-world, strip-water treatment.

A systematic revolution from these developments is the application of ML and quantitative structure-activity relationship models to predict and optimize the redox behavior of metal center-coordinate metal ions -high valency. While classical approaches can provide mechanistic detail based on empirical evidence (e.g. density functional theory, DFT), they are often too computationally intensive to allow for high-throughput applications. Instead, ML algorithms have been trained using datasets of metal coordination landscapes, ligand electronegativity, oxidation state, and reaction kinetics, which can be used almost instantaneously to find the best catalyst-oxidant combinations to destroy chemically specific target pollutants [

83]. Specifically, a DFT-augmented ML model was developed recently to predict the formation energy and oxidation potential of Fe(IV)=O with an overall precision of >90 percent within nitrogen-doped carbon matrices to enable the design of tailored redox window catalysts [

83].

Bioinspired mimicry also enlarges the design space by adopting nature to come up with evolutionary solutions to selective oxidation. Multicopper oxidases of manganese-oxidizing bacteria and cytochrome P450 systems use carefully tuned metal chelates to generate and stabilize high-valent intermediates in the very non-oxidative conditions encountered in the ambient environment [

84,

85].

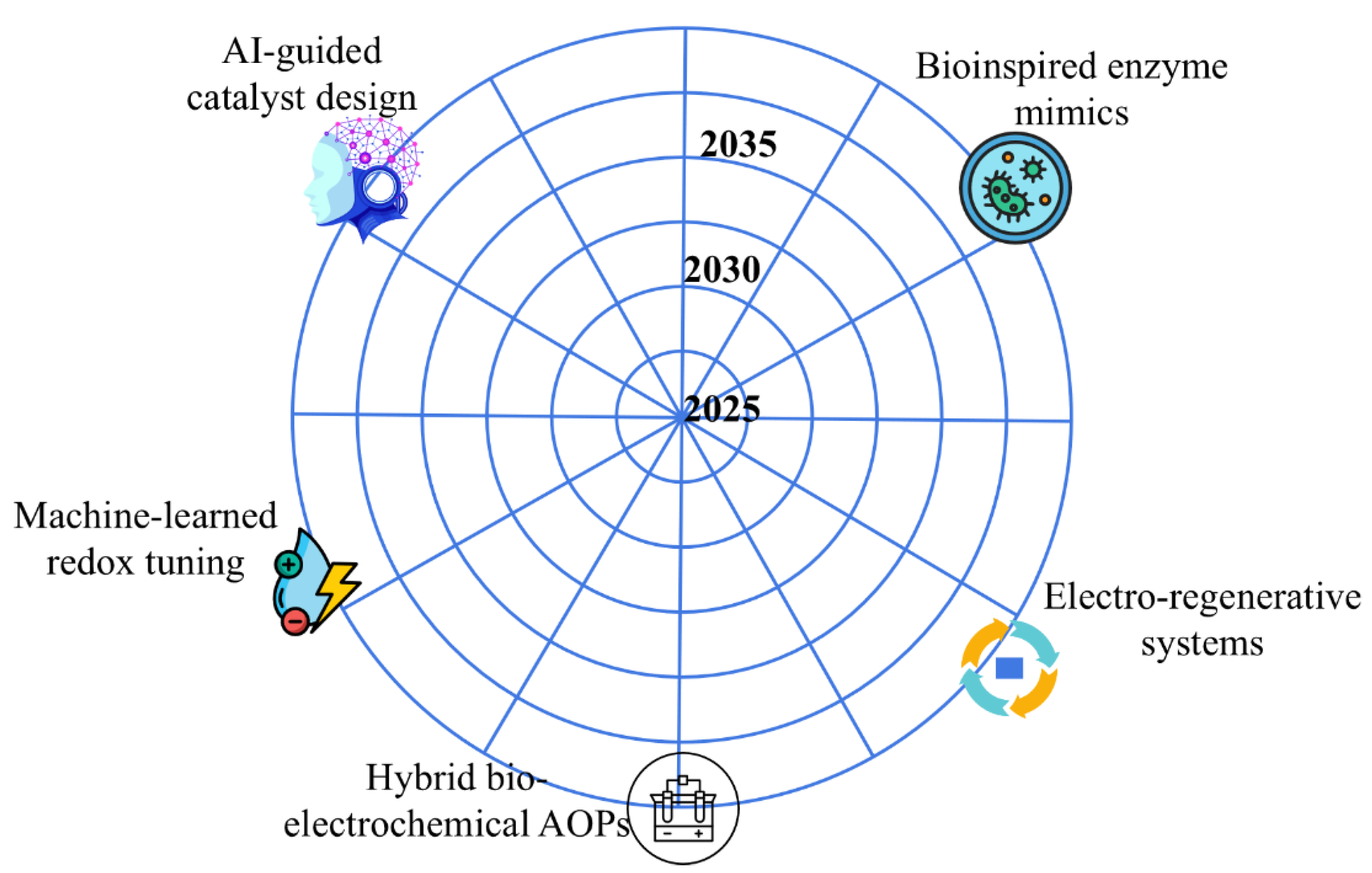

Figure 6 shows a technology known as radar forecast that displays the maturity of select innovations- such as ML-guided catalyst design, single-atom systems, and bio-hybrid reactors - until 2025; it is based on already existing publication rates/trends and pilot-scale confirmations of efficacy.

Ligand engineering, including the introduction of regular histidine-like N-donor sites [

86] in MOF or carbon supports, is now replicating these motifs specifically to stabilize Mn(V)=O and Fe(IV)=O species [

87]. As an example, Co-N-C catalysts based on MOFs with a laccase-like active site incorporating pyridinic nitrogen vacancies enable two-electron activation of PMS and high-valent cobalt-oxo reaction products formation [

88,

89]. Not only do these biohybrid designs serve to increase catalytic efficiency, but they also serve to increase the selectivity towards the more electron-rich contaminants, reducing undesired peripheral reactions.

At the atomic level, nanoengineering has provided a new ability to control the environment of high-valent atoms comprising metals. Isolated, well-defined, active sites for maximum atom utilization can be found in the M1-N-C structures (M = Fe, Co, Mn) of SACs, thus inhibiting dimerization or over-oxidation [

90,

91]. Defect engineering applied later, the inclusion of oxygen vacancies, carbon vacancies or heteroatom doping, also modify the electronic structure of the metal center and promotes heterolytic O-O bond cleavage across oxidants such as PMS and PAA, to enable high-valent metal pathways in place of the radical route [

83,92].

Despite these advancements, challenges still exist in scaling more complex engineered systems and thus the selection of high-valent metal SACs for AOPs will likely remain limited. SACs are often made via high temperature pyrolysis, which often induces agglomeration of the metalloid and non-uniform distributions of sites. Secondly, the long-term stability of bioinspired ligands in oxidative and acidic environments will need to be ascertained. Lastly, lab-level advancements will need to be relevant to the field in future studies by collectively using accelerated aging tests to demonstrate operational conditions with in situ characterizations (operando XAS or EPR), and data-driven modeling techniques such as life-cycle assessment. Overall, merging of nanoengineering, biology, and data-based modeling is evolving the landscape of AOPs of high-valent metals. By using prediction over replication, and innovation over quick mechanisms will achieve the elusive answer to sustainable smart systems of water treatments.

Table 3.

Comparison performance of high-valent metal based AOPs.

Table 3.

Comparison performance of high-valent metal based AOPs.

| Hybrid AOP System |

Primary Energy Input |

Specific Energy Consumption (kWh/m³) |

Mineralization Efficiency (% COD/TOC) |

Dominant Reactive Species |

Key Transformation Byproducts |

Ecotoxicity Change (Post-Treatment) |

references |

|

| Fe(VI)/UV |

Sulfamethoxazole |

98% |

65% |

Fe(V)/Fe(IV) |

0.8 |

No radical scavenging; dual oxidation–coagulation |

High Fe(VI) synthesis cost |

[24] |

| Mn(V)/Periodate |

Phenol |

95% |

70% |

Mn(V)=O |

0.5 |

High selectivity; low chloride interference |

Requires ligand stabilization (e.g., NTA) |

[46] |

| Co(IV)/PMS |

Bisphenol A |

99% |

78% |

Co(IV)=O |

1.2 |

High oxidation potential; fast kinetics |

Cobalt leaching at low pH |

[93] |

| Cu(III)/PAA |

Carbamazepine |

97% |

60% |

Cu(III) |

1.0 |

High electron efficiency (77%) |

Limited oxidant stability |

[18] |

| Fe(IV)/PMS–LDH |

Sulfamethoxazole |

96% |

68% |

Fe(IV)=O |

0.9 |

Heterogeneous, reusable, neutral pH operation |

Complex synthesis of LDH supports |

[94] |

| Ru(VIII)/O₃ |

Diclofenac |

94% |

82% |

Ru(VIII), •OH |

2.1 |

Complete mineralization |

High cost; rare metal |

[95] |

| UV/H₂O₂ (Radical AOP) |

Atrazine |

80% |

45% |

•OH |

1.5 |

Mature technology; scalable |

Radical scavenging by NOM; low selectivity |

[96] |

Table 4.

High-Valent Metal Catalyst Classes.

Table 4.

High-Valent Metal Catalyst Classes.

| Catalyst Class |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

Opportunities |

Threats |

|

Homogeneous(e.g., Fe²⁺, Mn²⁺, Co²⁺) |

High activity; well-understood mechanisms; rapid activation kinetics |

Metal leaching; narrow pH range; non-reusable; secondary pollution |

Ligand stabilization (e.g., TAMLs); synergistic co-catalysts (e.g., Cu²⁺) |

Regulatory limits on metal discharge; negative public perception |

|

Heterogeneous Oxides(e.g., Co₃O₄, MnO₂, Fe₂O₃) |

Reusable; stable; scalable synthesis |

Limited active sites; particle aggregation; radical-dominated mechanisms |

Morphology control (e.g., nanowires); defect engineering |

Competition from carbon-based and single-atom catalyst systems |

|

Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs)(e.g., M–N–C) |

Maximized atom efficiency; tunable metal coordination; high selectivity |

Complex synthesis; long-term stability challenges |

AI-guided design; dual-atom sites (e.g., Fe–Ni) |

Scalability barriers; high pyrolysis temperature and precursor cost |

|

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)& Derivatives |

High surface area; tunable porosity; platform for in situ SACs |

Hydrolytic instability; poor electrical conductivity |

Pyrolysis to form encapsulated catalysts; MOF-carbon hybrid composites |

The framework collapses under acidic or oxidative AOP conditions |

|

Bioinspired Complexes(e.g., TAMLs, Porphyrins) |

High selectivity; environmentally friendly ligands; mild reaction conditions |

High synthetic cost; short operational lifespan |

Support immobilization; enzyme-mimetic reactor integration |

Ligand degradation; unclear regulatory pathways |

5. Conclusions

Metal agents with high oxidation states, such as Fe(IV), Mn(V), Co(IV), and Cu(III), are providing great advances in AOPs that are now being driven away from the radical-based systems of the past, and toward more selective, effective, and safer strategies. These metals will undergo a different oxidative pathway to break down persistent, electron-rich contaminants by transitioning through aggregate transformations, such as oxygen atom transfer and hydride abstraction, instead of relying on generating unwanted products. New advances in stabilizing these reactive species, with switching towards the direction of the future in the appearance of distributed reactive sites with ligand design, the use of single-atom catalysts, and other MOFs will allow for unique innovations in treating complicated water contaminants. This has been reviewed and how the combination of high-valence metals with energy-assisted processes such as photocatalysis, sonocatalysis, and electrochemical regeneration is not only effective to enhance performance but also factors in to circular models of water treatment. These hybrid systems do more than just degrade pollutants; they also enable the recovery of valuable resources, such as nutrients and trace metals, turning waste into something useful. However, several hurdles still need to be addressed. The short lifespan of high-valent species in water, the risk of metal leaching, the energy demands of certain systems, and the lack of clear links between catalyst structure and performance are ongoing challenges. Moreover, most current research is limited to lab-scale experiments using model pollutants, leaving a gap in our understanding of how these systems perform in real, complex wastewater environments. Looking to the future, promising solutions are emerging. Bioinspired catalysts and microbially derived ligands offer potential for stabilizing high-valent species under mild conditions, while data-driven approaches like machine learning could speed up the discovery of better catalyst-oxidant combinations. These innovations may help overcome the current limitations and bring these technologies closer to practical, large-scale use. Ultimately, by treating high-valent metals not just as one-time-use oxidants but as reusable, central players in catalytic cycles, we move closer to achieving sustainable and circular water treatment systems. With the right integration of chemistry, engineering, and environmental thinking, these advanced oxidation processes could become a key part of the solution to global water pollution and resource recovery challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Q.; validation, M.I.N. and S.H. investigation, R.W.; resources, C.G.J and M.I.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Q; writing—review and editing, M.Q, M.I.N, C.G.J. and J.S-H.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, S.M.; funding acquisition, J.S.H., and C.G.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the students of Food Technology and Innovation Research Center of Excellence, School of Agricultural Technology and Food Industry, Walailak University for their assistance. J. S-H acknowledges ANID-FONDECYT/Post-Doctoral Grant No. 3230179.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nabeel, M.I.; Hussain, D.; Ahmad, N.; Najam-Ul-Haq, M.; Musharraf, S.G. Recent advancements in the fabrication and photocatalytic applications of graphitic carbon nitride-tungsten oxide nanocomposites. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 5214–5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicataldo, G.; Desmond, P.; Al-Maas, M.; Adham, S. Feasibility and application of membrane aerated biofilm reactors for industrial wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2025, 280, 123523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabeel, M.I.; Gulzar, T.; Kiran, S.; Ahmad, N.; Raza, S.A.; Batool, U.; Rehan, Z.A. Tailoring Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4) for Multifunctional Applications: Strategies for Overcoming Challenges in Catalysis and Energy Conversion. Int. J. Energy Res. 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., A.K. Singh, and R. Chandra, Recent advances in physicochemical and biological approaches for degradation and detoxification of industrial wastewater. Emerging treatment technologies for waste management, 2021: p. 1-28.

- Nabeel, M.I.; Hussain, D.; Ahmad, N.; Xiao, H.-M.; Ahmad, W.; Musharraf, S.G. Facile one-pot synthesis of metal and non-metal doped g-C3N4 photocatalyst for rapid acetaminophen remediation. Carbon 2025, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simarro-Gimeno, C.; Pitarch, E.; Albarrán, F.; Rico, A.; Hernández, F. Ten years of monitoring pharmaceuticals and pesticides in the aquatic environment nearby a solid-waste treatment plant: Historical data, trends and risk assessment. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 366, 125496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, A. Environmental Impact of Textile Materials: Challenges in Fiber–Dye Chemistry and Implication of Microbial Biodegradation. Polymers 2025, 17, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghernaout, D. Water treatment chlorination: An updated mechanistic insight review. Chemistry Research Journal 2017, 2, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, S. , et al., Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of Sulfur–Nitrogen Co-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles Synthesized using Dactylorhiza hatagirea Root Extract. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e01568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, K.; Sohail, M.; Rind, K.H.; Habib, S.S. Agrochemical contamination and fish health: eco-toxicological impacts and mitigation strategies. Chem. Ecol. 2025, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- i Quer, A.M.; Gholipour, A.; Plestenjak, G.; Carvalho, P.N. Emerging contaminants in sludge treatment reed beds: Removal, persistence, or accumulation? Water Res. 2025, 287, 124423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Ramísio, P.J.; Puga, H. A Comprehensive Review on Various Phases of Wastewater Technologies: Trends and Future Perspectives. Eng 2024, 5, 2633–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NI, B.-J.; Yu, H.-Q. Microbial Products of Activated Sludge in Biological Wastewater Treatment Systems: A Critical Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 42, 187–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.Y.; Aroua, M.K.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Review of modifications of activated carbon for enhancing contaminant uptakes from aqueous solutions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007, 52, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, M.; Román, M.F.S.; Ortiz, I.; Irabien, A. Overview of the PCDD/Fs degradation potential and formation risk in the application of advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) to wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2015, 118, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, M.; Evgenidou, E.; Lambropoulou, D.; Konstantinou, I. A review on advanced oxidation processes for the removal of taste and odor compounds from aqueous media. Water Res. 2014, 53, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, D.; Yi, M.; Chang, F.; Li, H.; Du, Y. A Review of Sulfate Radical-Based and Singlet Oxygen-Based Advanced Oxidation Technologies: Recent Advances and Prospects. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J. High-valent metals in advanced oxidation processes: A critical review of their identification methods, formation mechanisms, and reactivity performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Dong, H.; Zhou, G.; Ma, J.; Sharma, V.K.; Guan, X. Degradation of Organic Contaminants by Reactive Iron/Manganese Species: Progress and Challenges. Water Res. 2022, 221, 118765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, Y.; Zeng, J.; Ren, W.; Xiao, X.; Luo, X. Activation of High-Valent Metal Oxidants on Carbon Catalysts: Mechanisms, Applications and Challenges. ACS ES&T Eng. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiang, H.; Li, S.; Wang, D.; Yang, B. A review on the role of high-valent metals in peracetic acid-based advanced oxidation processes. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Um, I.-H.; Yoon, J. Arsenic(III) Oxidation by Iron(VI) (Ferrate) and Subsequent Removal of Arsenic(V) by Iron(III) Coagulation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 5750–5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Shao, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Shao, B.; Xu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, W.; Wu, D. Enhanced Oxidation of Organic Contaminants by Iron(II)-Activated Periodate: The Significance of High-Valent Iron–Oxo Species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 7634–7642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Luo, M.; Zhou, P.; Liu, Y.; Du, Y.; He, C.; Yao, G.; Lai, B. Enhanced ferrate(VI)) oxidation of sulfamethoxazole in water by CaO2: The role of Fe(IV) and Fe(V). J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 128045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; He, Y.-L.; Peng, J.; Duan, X.; Lu, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; He, C.-S.; Xiong, Z.; Ma, T.; et al. High-valent metal-oxo species transformation and regulation by co-existing chloride: Reaction pathways and impacts on the generation of chlorinated by-products. Water Res. 2024, 257, 121715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.; Sun, H.; Shao, Z.; Wang, S. Nonradical reactions in environmental remediation processes: Uncertainty and challenges. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2018, 224, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wei, Z.; Duan, X.; Long, M.; Spinney, R.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Xiao, R.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Merits and Limitations of Radical vs. Nonradical Pathways in Persulfate-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 12153–12179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Zou, J.; Cai, H.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Xiao, J.; Yuan, B.; Ma, J. Hydroxylamine enhanced Fe(II)-activated peracetic acid process for diclofenac degradation: Efficiency, mechanism and effects of various parameters. Water Res. 2021, 207, 117796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qiu, W.; Pang, S.-Y.; Guo, Q.; Guan, C.; Jiang, J. Aqueous Iron(IV)–Oxo Complex: An Emerging Powerful Reactive Oxidant Formed by Iron(II)-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes for Oxidative Water Treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 1492–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S. , et al., Fe2+/HClO reaction produces FeIVO2+: an enhanced advanced oxidation process. Environmental Science & Technology 2020, 54, 6406–6414. [Google Scholar]

- Bera, M.; Kaur, S.; Keshari, K.; Santra, A.; Moonshiram, D.; Paria, S. Structural and Spectroscopic Characterization of Copper(III) Complexes and Subsequent One-Electron Oxidation Reaction and Reactivity Studies. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 5387–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Miao, J.; Ge, J.; Lang, J.; Yu, C.; Zhang, L.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Long, M. Ultrahigh Peroxymonosulfate Utilization Efficiency over CuO Nanosheets via Heterogeneous Cu(III) Formation and Preferential Electron Transfer during Degradation of Phenols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 8984–8992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mageed, A.M.; Rungtaweevoranit, B. Metal-organic frameworks-based heterogeneous single-atom catalysts (MOF-SACs) – Assessment and future perspectives. Catal. Today 2024, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishmael, A.; Nasser, M.; Abdel-Nasser, M.; Hossni, H.; Abdel-Hamed, Y.; Abdel-Salam, M.; Abdel-Gawad, S.; El-Sherif, R. Eco-friendly and cost-effective recycling of batteries for utilizing transition metals as catalytic materials for purifying tannery wastewater through Advanced Oxidation Techniques: A critical review. Nanotechnol. Appl. Sci. J. 2025, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Lai, B. Decontamination of heavy metal complexes by advanced oxidation processes: A review. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 2575–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiadou, A. From Organic Wastes to Bioenergy, Biofuels, and Value-Added Products for Urban Sustainability and Circular Economy: A Review. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J. Advances in the development and application of ferrate(VI) for water and wastewater treatment. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2013, 89, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Fu, K.; Fu, Y.; Liu, X.; Luo, S.; Yin, K.; Luo, J. Manipulating High-Valent Cobalt-Oxo Generation on Co/N Codoped Carbon Beads via PMS Activation for Micropollutants Degradation. ACS ES&T Eng. 2023, 3, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Tang, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, L.; Fu, Y. Enhanced Mn(II)/peracetic acid by nitrilotriacetic acid to degrade organic contaminants: Role of Mn(V) and organic radicals. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Yue, K.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Yan, Y.; Cao, R.; Zhang, W. Electrocatalytic water oxidation with manganese phosphates. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhu, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Ni, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, L.; et al. Customized reaction route for ruthenium oxide towards stabilized water oxidation in high-performance PEM electrolyzers. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Kim, J.-H. Outlook on Single Atom Catalysts for Persulfate-Based Advanced Oxidation. ACS ES&T Eng. 2022, 2, 1776–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, D. Tremendously enhanced catalytic performance of Fe(III)/peroxymonosulfate process by trace Cu(II): A high-valent metals domination in organics removal. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 147, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzayani, B.; Lomba-Fernández, B.; Fdez-Sanromán, A.; Elaoud, S.C.; Sanromán, M.Á. Advancements in Copper-Based Catalysts for Efficient Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species from Peroxymonosulfate. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Pang, S.-Y.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Y.-M.; Jiang, J. Quantitative evaluation of relative contribution of high-valent iron species and sulfate radical in Fe(VI) enhanced oxidation processes via sulfur reducing agents activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Dong, H.; Lian, L.; Guan, X. Selective and rapid degradation of organic contaminants by Mn(V) generated in the Mn(II)-nitrilotriacetic acid/periodate process. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Li, J.; Tan, J.; Lyu, L.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, T. High-valent cobalt-oxo species triggers singlet oxygen for rapid contaminants degradation along with mild peroxymonosulfate decomposition in single Co atom-doped g-C3N4. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Dai, R.; Wang, Z. Unraveling the Co(IV)-Mediated Oxidation Mechanism in a Co3O4/PMS-Based Hierarchical Reactor: Toward Efficient Catalytic Degradation of Aromatic Pollutants. ACS ES&T Eng. 2022, 2, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Shi, M.; Yin, Q.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, L. Organically coordinated Cu(II) activated peroxymonosulfate for enhanced degradation of emerging contaminants. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.J.; Ryabov, A.D. Targeting of High-Valent Iron-TAML Activators at Hydrocarbons and Beyond. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 9140–9162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanda, A. , et al. (TAML) FeIV O Complex in Aqueous Solution: Synthesis and Spectroscopic and Computational Characterization. Inorganic chemistry 2008, 47, 3669–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigoni, G.; Nylund, P.V.S.; Albrecht, M. Manganese(iii) complexes stabilized with N-heterocyclic carbene ligands for alcohol oxidation catalysis. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 7992–8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, M.; Nimir, H.; Demeshko, S.; Bhat, S.S.; Malinkin, S.O.; Haukka, M.; Lloret-Fillol, J.; Lisensky, G.C.; Meyer, F.; Shteinman, A.A.; et al. Nonheme Fe(IV) Oxo Complexes of Two New Pentadentate Ligands and Their Hydrogen-Atom and Oxygen-Atom Transfer Reactions. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 7152–7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, W. High-Valent Iron(IV)–Oxo Complexes of Heme and Non-Heme Ligands in Oxygenation Reactions. Accounts Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yao, G.; Lai, B. Synthesis strategies and emerging mechanisms of metal-organic frameworks for sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation process: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Duan, X.; Xu, X.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Qiu, H.; Wang, S.; Cao, X. Persulfate Oxidation of Sulfamethoxazole by Magnetic Iron-Char Composites via Nonradical Pathways: Fe(IV) Versus Surface-Mediated Electron Transfer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 10077–10086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, B.; Yang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Shih, K.; Li, H.; Wu, D.; Zhang, L. Mechanistic insight into the generation of high-valent iron-oxo species via peroxymonosulfate activation: An experimental and density functional theory study. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhan, P.; Zhao, F.; Dai, H.; Hu, Y.; Hu, F.; Peng, X. Generation and regulation of high-valent metal species in advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Funct. Mater. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Rui, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Kubuki, S.; Yong, Y.-C.; Zhang, L. Geometric and electronic perspectives on dual-atom catalysts for advanced oxidation processes. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 4968–5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Siddique, M.S.; Guo, Y.; Wu, M.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H. Low-crystalline bimetallic metal-organic frameworks as an excellent platform for photo-Fenton degradation of organic contaminants: Intensified synergism between hetero-metal nodes. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2021, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Rodriguez-Seco, C.; Hayati, F.; Ma, D. Sonophotocatalysis with Photoactive Nanomaterials for Wastewater Treatment and Bacteria Disinfection. ACS Nanosci. Au 2023, 3, 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Xiao, L.; Gao, S.; Abdukayum, A.; Kong, Q.; Hu, G.; Dubal, D.; Zhou, Y. From Fundamentals to Mechanisms: Peroxyacetic acid catalysts in emerging pollutant degradation. Mater. Today 2025, 87, 197–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; von Gunten, U.; Kim, J.-H. Persulfate-Based Advanced Oxidation: Critical Assessment of Opportunities and Roadblocks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3064–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolluru, A.; Shuaibi, M.; Palizhati, A.; Shoghi, N.; Das, A.; Wood, B.; Zitnick, C.L.; Kitchin, J.R.; Ulissi, Z.W. Open Challenges in Developing Generalizable Large-Scale Machine-Learning Models for Catalyst Discovery. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 8572–8581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakma, S.; Moholkar, V.S. Investigations in Synergism of Hybrid Advanced Oxidation Processes with Combinations of Sonolysis + Fenton Process + UV for Degradation of Bisphenol A. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 6855–6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Control Effect of Peracetic Acid on Chlorinated DBP Formation and the Application of PAA Pre-oxidation in Drinking Water Treatment. 2021.

- Zhang, J., M. Chen, and L. Zhu, Activation of persulfate by Co3O4 nanoparticles for orange G degradation. 2015.

- Osabuohien, F.O.; Djanetey, G.E.; Nwaojei, K.; Aduwa, S.I. Wastewater treatment and polymer degradation: Role of catalysts in advanced oxidation processes. World J. Adv. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2023, 9, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. , et al. Novel nonradical oxidation of sulfonamide antibiotics with Co(II)-doped g-C3N4-activated peracetic acid: role of high-valent cobalt–oxo species. Environmental Science & Technology 2021, 55, 12640–12651. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, Y. Revisiting the role of reactive oxygen species for pollutant abatement during catalytic ozonation: The probe approach versus the scavenger approach. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2021, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Von Gunten, U. Oxidative transformation of micropollutants during municipal wastewater treatment: Comparison of kinetic aspects of selective (chlorine, chlorine dioxide, ferrate VI, and ozone) and non-selective oxidants (hydroxyl radical). Water Research 2010, 44, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Guan, X. Unlocking the potential of ferrate(VI) in water treatment: Toward one-step multifunctional solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 464, 132920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.K., et al., Physicochemical treatment consisting of chemical coagulation, precipitation, sedimentation, and flotation, in Integrated natural resources research. 2021, Springer. p. 265-397.

- Sharma, V.K.; Zboril, R.; Varma, R.S. Ferrates: Greener Oxidants with Multimodal Action in Water Treatment Technologies. Accounts Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Yue, Y.; Deng, S.; Xu, B.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, X.; Lv, G.; Jiang, Q.; Xiao, H.; Wang, D.; et al. Enhanced Decontamination in Mn(II)/Periodate Systems with EDTA: Mechanistic Insights into Self-Accelerating Degradation of Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 14170–14181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K. Oxidation of inorganic contaminants by ferrates (VI, V, and IV)–kinetics and mechanisms: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1051–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhu, S.; Duan, Y.; Pi, C.; Zhang, X.; Woldu, A.R.; Jian, J.-X.; Chu, P.K.; Tong, Q.-X.; Hu, L.; et al. Insights into ionic association boosting water oxidation activity and dynamic stability. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 89, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Cheng, C.; Shao, P.; Luo, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Duan, X. Origins of Electron-Transfer Regime in Persulfate-Based Nonradical Oxidation Processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.; Tayyab, A.; Umair, M.; Naveed, M.R.; Yaseen, H.R.; Qasim, M.; Muzammal, M.; Saif, S.; Ali, M.A.; Sultan, M.A. Recent Progress in Wastewater Treatment: Exploring the Roles of Zero-Valent Iron and Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles. Indus J. Biosci. Res. 2025, 3, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.-S.; Zhong, S.; Cheng, C.; Zhou, H.; Sun, H.; Duan, X.; Wang, S. Microenvironment Engineering of Heterogeneous Catalysts for Liquid-Phase Environmental Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 11348–11434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makatsa, T.J.; Baloyi, J.; Ntho, T.; Masuku, C.M. Catalytic wet air oxidation of phenol: Review of the reaction mechanism, kinetics, and CFD modeling. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 51, 1891–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T., X. Chen, and L. Yin, Recent advancements in modified SnO2–Sb electrodes for electrochemical treatment of wastewater. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2024, 12, 4397–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Yang, B.; Feng, X.; Liao, Z.; Shi, H.; Jiang, W.; Wang, C.; Ren, N. Density Functional Theory and Machine Learning-Based Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Models Enabling Prediction of Contaminant Degradation Performance with Heterogeneous Peroxymonosulfate Treatments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 3951–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shugrue, C.R.; Miller, S.J. Applications of Nonenzymatic Catalysts to the Alteration of Natural Products. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11894–11951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, K.D.; Shaik, S. Cytochrome P450—The Wonderful Nanomachine Revealed through Dynamic Simulations of the Catalytic Cycle. Accounts Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Yan, J.; Cui, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Du, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X.; Li, B. Nanozymes in Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Diseases: From Design and Preclinical Studies to Clinical Translation Prospects. Small Struct. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Weng, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Ou, X.; Xu, X.; Cai, Y.; Jiang, J.; Han, B.; et al. Coordination engineering of heterogeneous high-valent Fe(IV)-oxo for safe removal of pollutants via powerful Fenton-like reactions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, W.; Gan, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, S. Laccase immobilization with metal-organic frameworks: Current status, remaining challenges and future perspectives. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 52, 1282–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Akram, W.; Liu, H.-Y. Reactive Cobalt–Oxo Complexes of Tetrapyrrolic Macrocycles and N-based Ligand in Oxidative Transformation Reactions. Molecules 2018, 24, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.; Su, Y.; Li, F.; Shen, W.; Chen, Z.; Tang, Q. Understanding activity origin for the oxygen reduction reaction on bi-atom catalysts by DFT studies and machine-learning. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 24563–24571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, C.; Xiong, Z.; Pan, Z.; Yao, G.; Lai, B. Recent advances in single-atom catalysts for advanced oxidation processes in water purification. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).