1. Introduction

The increasing concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO

2) has driven the need for sustainable technologies that can effectively reduce CO

2 emissions while simultaneously generating value-added products. Among these, the catalytic conversion of CO

2 into carbon monoxide (CO) through the reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) reaction has emerged as a promising pathway. CO, as a key building block for synthetic fuels and chemicals, plays a central role in the production of hydrocarbons via processes like Fischer-Tropsch synthesis. [

1,

2,

3,

4] Moreover, RWGS serves as a crucial step in the establishment of a closed carbon cycle, offering a practical route to recycle CO

2 and reduce environmental impacts.

Despite its potential, the RWGS reaction faces several challenges, particularly due to the competitive Sabatier reaction, which favors the production of methane (CH

4) at lower temperatures. [

5,

6] This competition often limits the efficiency and selectivity of CO production. [

7] Therefore, the development of catalysts that can selectively promote CO

2 reduction to CO, while suppressing undesirable side reactions, is critical. Such catalysts must exhibit high activity, robust stability, and precise control over reaction intermediates to achieve the desired selectivity under mild reaction conditions.

Transition metal-based catalysts, particularly nickel (Ni) and cobalt (Co), have been extensively explored for CO

2 reduction due to their favorable activity and tunable electronic properties. [

8,

9,

10,

11] However, their performance in RWGS reactions is often constrained by limited CO selectivity and poor stability under reaction conditions. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of structural and electronic modifications, such as the incorporation of oxygen vacancies and synergistic bimetallic interactions, in overcoming these limitations. [

12,

13,

14] Oxygen vacancies play a vital role in activating CO

2, facilitating its adsorption and dissociation, while adjacent active metal domains, such as Ni, are highly effective for H

2 splitting. [

15,

16]

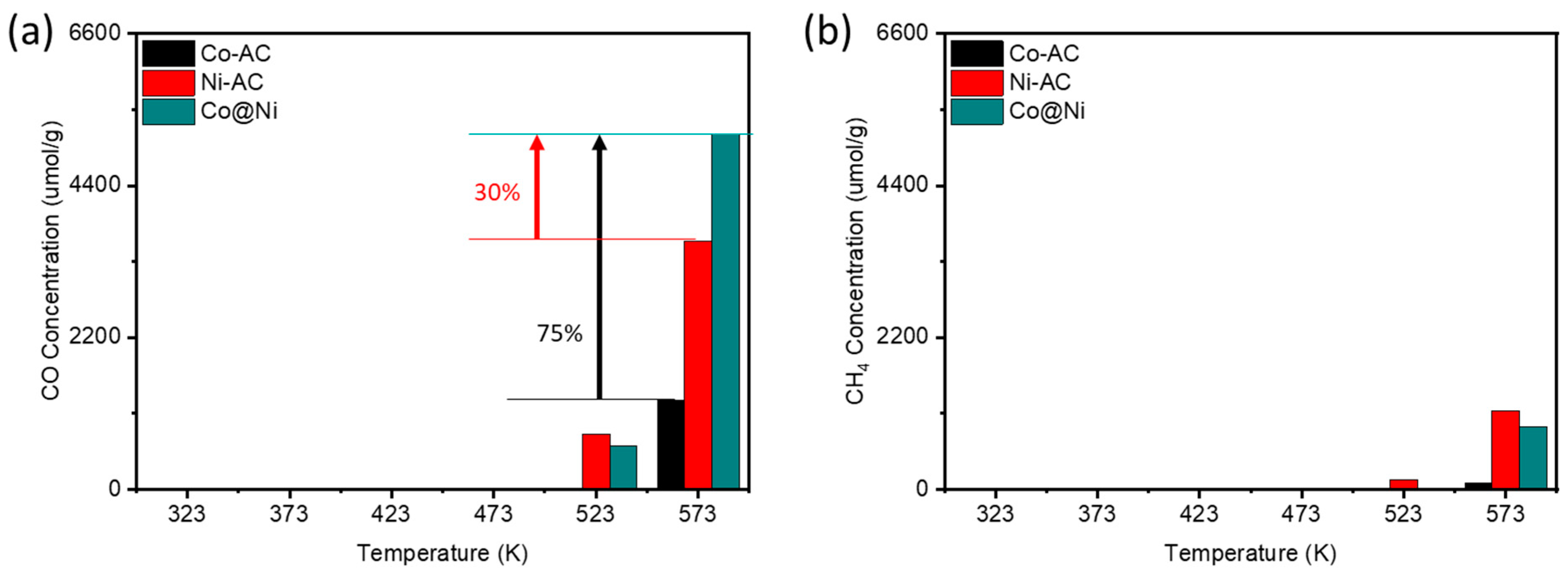

In this work, we address these challenges by developing a novel catalyst comprising nickel hydroxide nanoparticles supported on cobalt oxide enriched with oxygen vacancies (denoted as Co@Ni). This catalyst leverages the electronic and synergistic interplay between Co and Ni active sites to enhance both CO2 activation and H2 dissociation. Our results demonstrate that Co@Ni achieves a CO production yield of ~5144 μmolgcatalyst-1 at 573 K, outperforming carbon-supported Ni(OH)2 (Ni-AC) and CoO (Co-AC) catalysts by 30% and 70%, respectively. By integrating physical characterization with electrochemical analyses, we elucidate the mechanism behind this enhanced performance, providing valuable insights into the design of advanced catalysts for RWGS reactions.

2. Experimental

2.1. Preparation of Co@Ni Catalyst

The synthesis of carbon supported Co@Ni binary catalysts was carried out through a sequence of steps involving chemisorption, galvanic replacement, and wet chemical reduction of metal ions with precise control over reaction parameters on the active carbon support. Before synthesis the support material (i.e. active carbon (AC)) was surface functionalized by previously reported method. [

17] The synthesis process began by preparing a slurry with 3 g of AC, which was sonicated for 30 minutes. Following this, 0.1 M of 3.055 g aqueous cobalt chloride hexahydrate (CoCl

2·6H

2O) solution was added, and the mixture was sonicated for an additional 30 minutes. The solution was then stirred at 600 rpm for 4 hours. To facilitate reduction, an excess amount of sodium borohydride (NaBH

4) was introduced into the mixture. After that 0.1 M of 3.055 g of nickel chloride hexahydrate (NiCl

2·6H

2O) solution was added, which was reduced by the excess amount of NaBH

4 added in the previous step. The resulting product was separated via centrifugation and thoroughly washed sequentially with deionized water, ethanol, and acetone to ensure purity. Finally, the as-prepared material was dried in a vacuum at 70 °C for 24 hours. The resulting sample was labelled as Co@Ni.

2.2. Physical and Structural Characterizations

To analyze the physical properties of the control samples and Co@Ni catalyst, a combination of microscopy and X-ray spectroscopy techniques were utilized. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) was performed at the Electron Microscopy Center of the National Taipei University of Technology (NTUT), Taiwan, to examine the crystal structure and surface morphology of the synthesized materials in their pristine states. Crystallographic characteristics were studied using X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements, carried at beamline BL-O1C1 of the Taiwan Light Source (TLS) at the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC), Taiwan. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was performed at beamline BL-17C1 of the NSRRC to further explore the electronic structure and coordination environment of the samples.

2.3. CO2 Conversion Performance Analysis

The catalytic performance of the Co@Ni catalyst, along with the control samples, for CO

2 conversion was assessed following a protocol described in a previously published study. [

18] In detail, the gas chromatography (GC) analysis was conducted using an Agilent 7890 instrument equipped with a Valco PDHID detector (pulsed discharge helium ionization detector, model D-3-I-7890, VICI, USA). A test sample comprising 12 mg of catalyst and 23 mg of silicone gel was thoroughly mixed and loaded into a glass tube with dimensions of 100 mm in length, an inner diameter of 2 mm, and an outer diameter of 3 mm. The reaction was performed under constant pressure conditions, regulated by a pressure control module (PCM, Agilent). Ultra-high-purity helium (99.9995%) served as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 30 mL min⁻¹. The gas products, after passing through the packed reactor bed, were analyzed using the GC system, following a temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) protocol. The oven temperature was increased from 273 K to 573 K at a ramp rate of 20 K min⁻¹, and the separated components were detected by the PDHID detector. To eliminate any moisture from the reaction system, nitrogen gas (N

2) was first flowed through the reactor at 50 mL min⁻¹ for 1 hour at room temperature. Subsequently, a gas mixture containing CO

2-H

2 with a ratio of 1:3 was introduced into the reaction bed at a flow rate of 20 mL min⁻¹, with the temperature set between 273 K and 573 K. At each temperature step, the system was held isothermal for 30 minutes, and the resulting gas products were analyzed using the GC system.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physical Structure Inspections

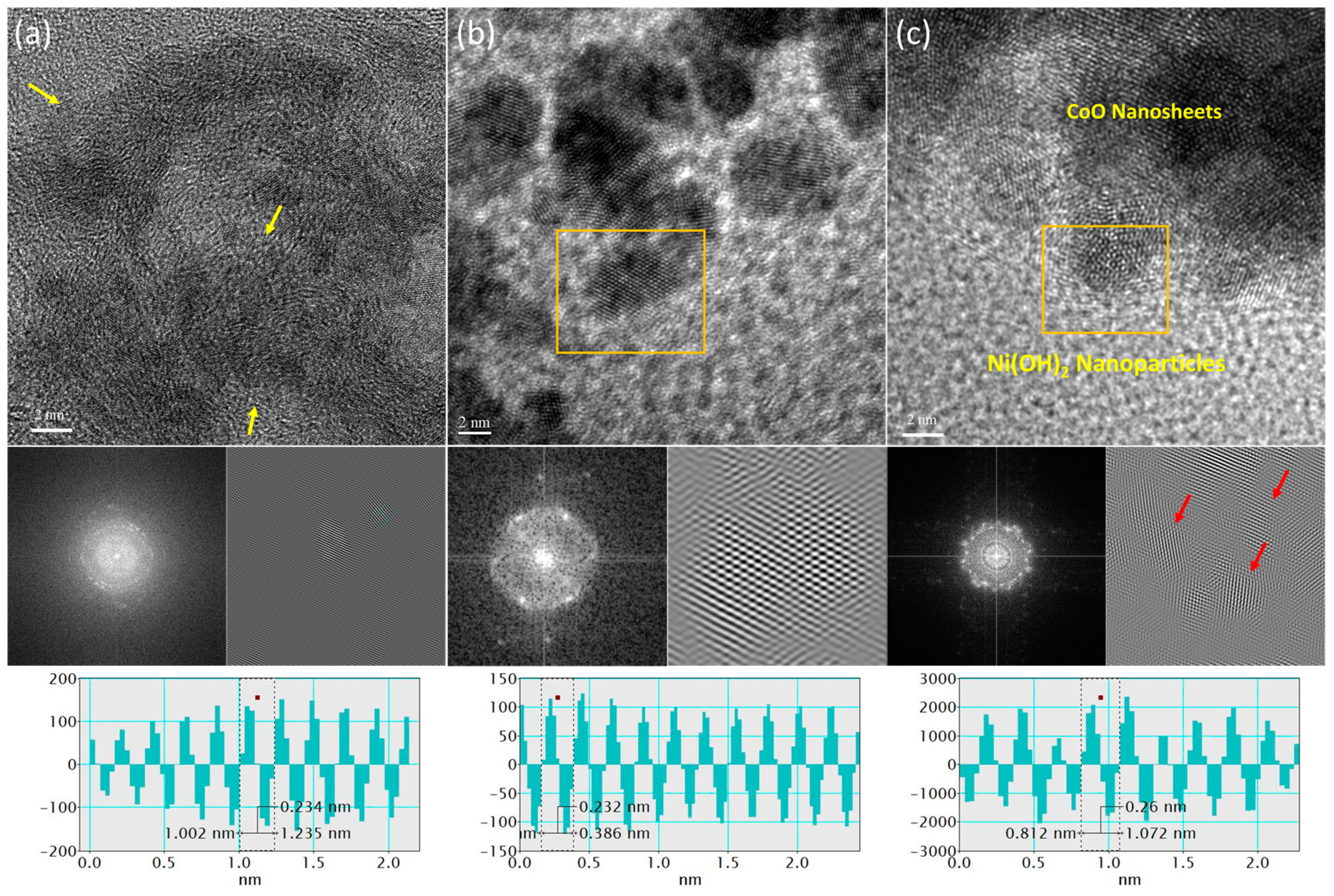

Figure 1a shows the HRTEM image of active carbon supported cobalt oxide (Co-AC). Accordingly, the cobalt oxide is grown in form of amorphous nanosheets on the AC support with a d-spacing of 0.234 nm, which is corresponding to the CoO (222) plane. [

19] The fuzzy Forward Fourier Transformation (FFT) pattern in the absence of clear bright spots further confirms the amorphous nature of CoO nanosheets. On the other hand, as shown in

Figure 1b, the nickel-hydroxide (Ni(OH)

2) nanoparticles with the d-spacing of 0.232 ( corresponds to the (013) plane of Ni(OH)

2) have been grown with more crystallinity. [

20] Such a scenario has been complimentary confirmed by the hexagonal FFT patterns with twin bright spots. For Co@Ni, it is evident from

Figure 1c that the Ni(OH)

2 nanoparticles (indicated by brown box) are grown on amorphous nanosheets. Herein its worth noticing that the Co@Ni exhibits increased d-spacing of 0.260 nm along with ring like FFT pattern with multiple bright spots. These two observations integrally confirm the limited extent of heteroatomic intermixing between Ni and Co domains.

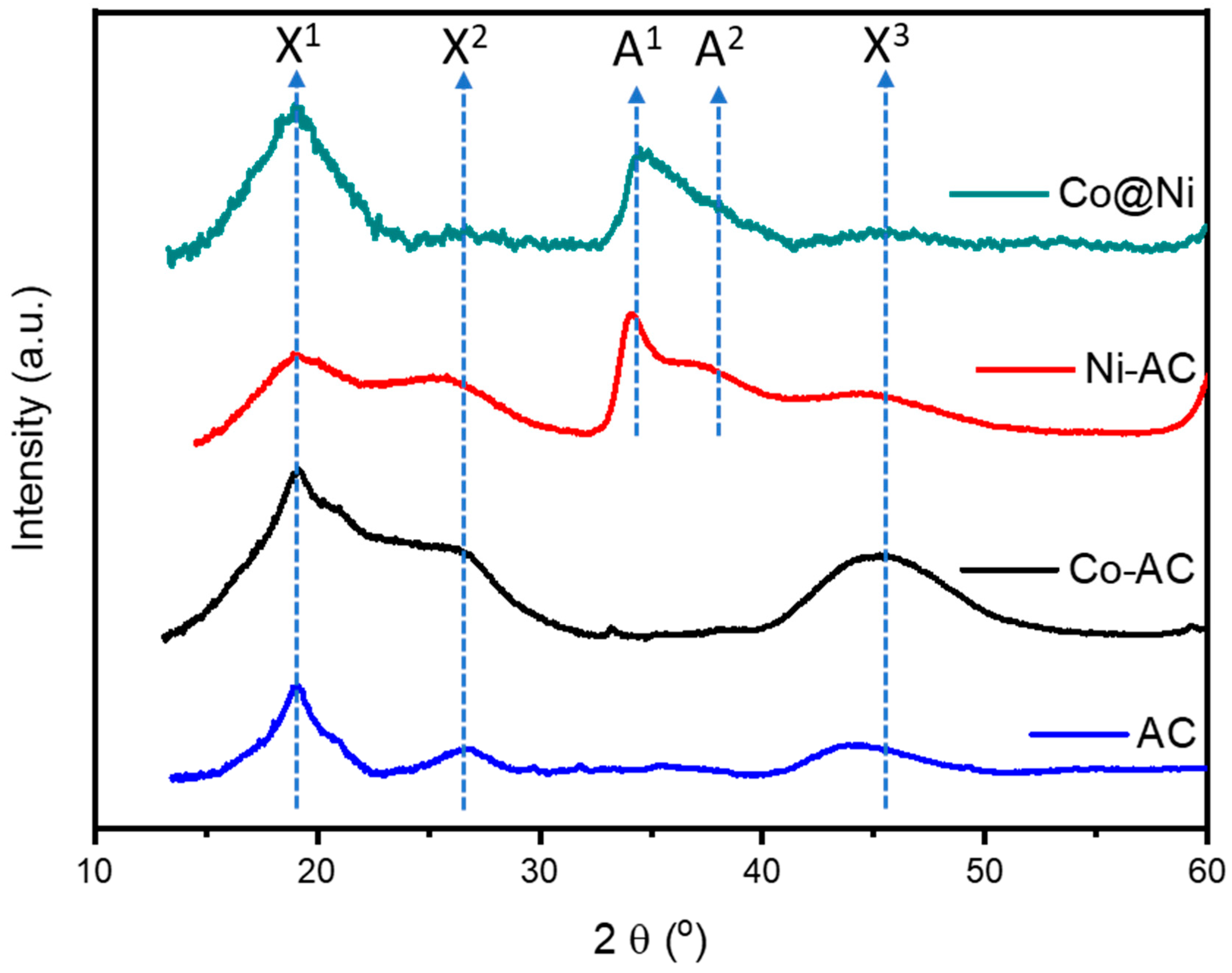

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra of control samples and Co@Ni were further analyzed to confirm the above discussed HRTEM observations about crystal structure. As shown in

Figure 2, the peaks X

1, X

2 and X

3 are corresponding to the different planes of active carbon support. Unsurprisingly, the Co-AC does not shows any additional diffraction signals compared to active carbon support, confirming that CoO nanosheets are grown in amorphous phase and consistent with aforementioned HRTEM observations. On the other hand, Ni-AC and Co@Ni samples exhibit prominent peaks A

1 and A

2, which are, respectively, corresponding to the (20-22) and (0004) planes of Ni(OH)

2. More interstingly, the suppressed peak intensities of Co@Ni as compared to Ni-AC can be attributed to the partial oxidation of Ni due to the heteratomic intermixing with CoO. These observations are in good agreement with HRTEM findings.

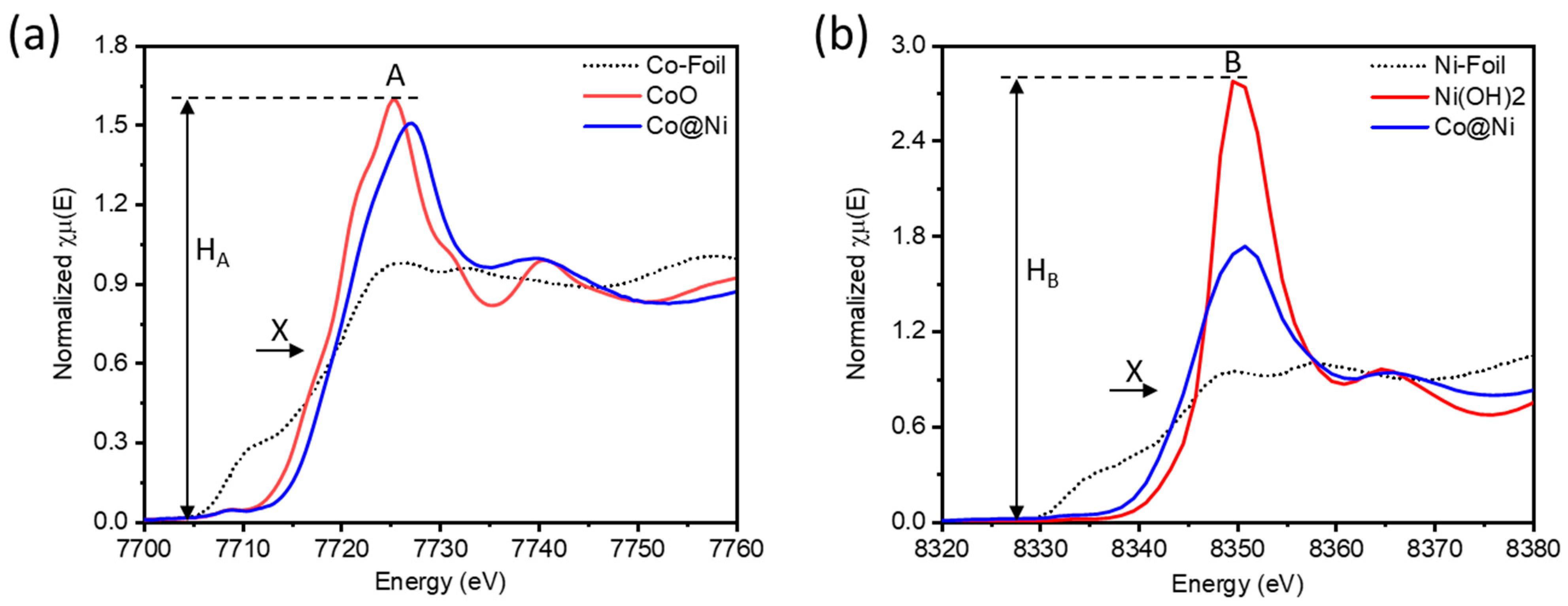

The electronic localization from Co-to-Ni domains in Co@Ni catalyst was elucidated by conducting X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS)at Co and Ni K-edges.

Figure 3a shows the normalized X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) at Co K-edge. Notably, compared to the CoO, the shift of inflection point X to higher energy values confirms the severe electron relocation from Co-to adjacent domains (Ni in this case). [

21] Given that the whiteline intensity is directly related to the presence of surface chemisorbed oxygen on the surface of catalyst. [

22] However, the Co@Ni catalyst exhibits the suppressed whiteline intensity (H

A) as compared to standard CoO. With the additional Ni(OH)

2 in Co@Ni system, such an observation indicates the presence of abundant oxygen vacancies in cobalt-oxide support. [

23] The aforementioned scenarios are further confirmed by analyzing the XANES spectra of Co@Ni catalyst at Ni K-edge. As shown in

Figure 3b, as compared to standard Ni(OH)

2, the shift of inflection point X position to the lower energy values along with suppressed whitleline intensity (H

B), confirms the increased electron density around Ni-atoms in Co@Ni and can be attributed to the stron electron relocation from Co-to-Ni domains. [

22] These observations are in good agreement with the results of Co K-edge XAS analysis. Moreover, the Co@Ni share the similar peak positions with Ni(OH)

2 in XANES as well as Fourier-transformed extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) spectra (

Figure S1) confirming that Ni is present in form of Ni(OH)

2. [

24]

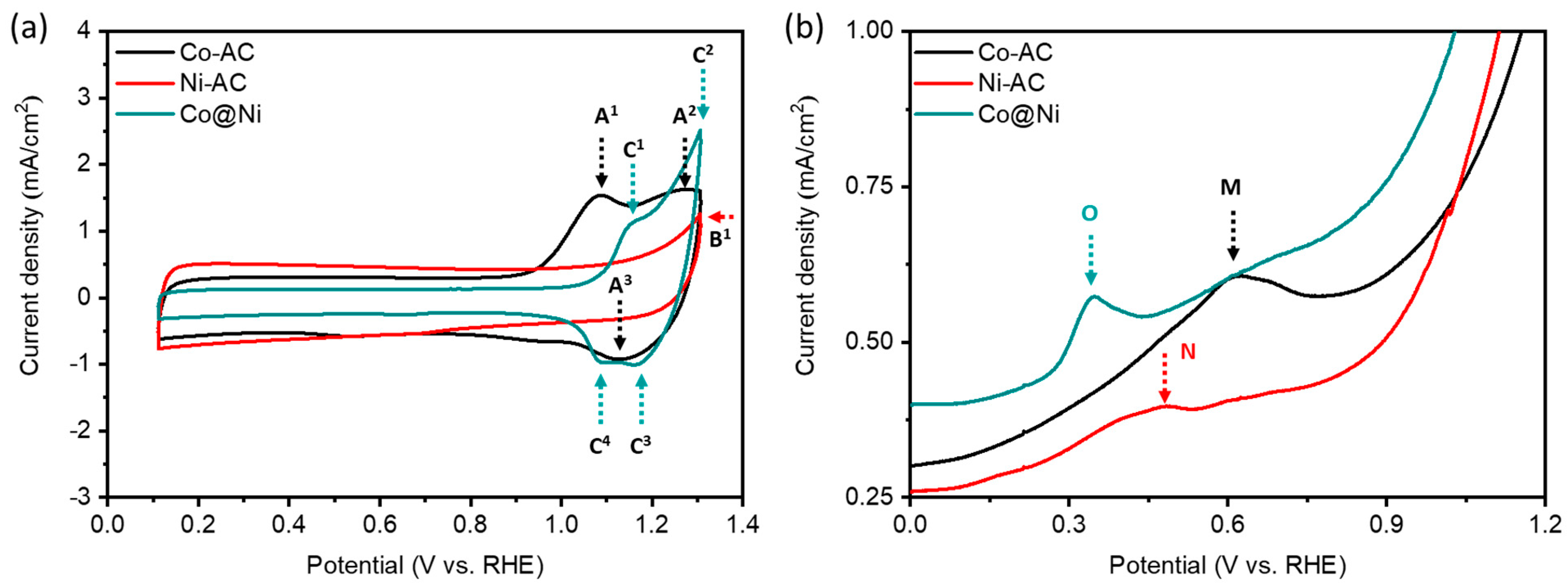

The surface chemcial identities and structural configuration of Co@Ni were further confirmed by the electrochemical analysis

Figure 4a represents the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of control samples and Co@Ni samples. All the CV curves were obtained in the N

2 saturated 0.1 M KOH electrolyte. Accordingly, all the three samples show flattened CV profiles upto 0.90 V vs RHE. Suggesting their inert nature. Such a scenario is obvious due to severe surface oxidation. At higher potential regions, the prominent peaks in the forward scan are correspond to the oxide/hydroxide formation, while the oxide reduction in the backward scan. Herein, it’s worth noticing that the Co@Ni samples shows peaks (C

1-C

3-C

4) corresponding to the Co-AC (A

1-A

3) as well as corresponding to the Ni-AC (B

1), confirming that Ni(OH)

2 nanoparticles are grown on CoO nanosheets. Furthermore, the CO-tolerance of Co@Ni is confirmed by the CO-stripping curves. As shown in

Figure 4b, the Co@Ni catalyst shows the CO oxidation peak (O) at lowest potential as compared to Co-AC (M) and Ni-AC (N), indicating the better CO tolerance of Co@Ni.

3.2. Catalytic Activity in CO2 Conversion

The catalytic activites of Co@Ni as well as Co-AC and Ni-AC in CO

2 conversion performances were assessed with the help of a flow reactor system within the temperature range of 273 K to 573 K under atmospheric pressure and reaction gas atmosphere of H

2/CO

2 (3/1). As shown in

Figure 5a, At 573 K, Co-AC demonstrates a significantly higher CO production yield, while the CH₄ concentration is almost null (

Figure 5b), indicating the predominance of the reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) reaction over CO₂ methanation. This behavior is likely due to the absence of active sites for H₂ dissociation in Co-AC. It is well-documented that metal oxides with abundant oxygen vacancies are effective in facilitating CO₂ activation but are generally inactive for H₂ splitting. [

16] In contrast, a significant rise in CH₄ production yield (1142 μmol g⁻¹ of catalyst) is observed for Ni-TiO₂, suggesting that Ni sites favours the H

2 splitting. Previous studies have highlighted the role of oxygen vacancies in promoting CO₂ dissociation, while Ni-hydro(oxide) nanoparticles are known to reduce to metallic Ni at 573 K in a hydrogen-rich environment. [

15] Thus, it can be inferred that during CO₂ methanation on Ni-TiO₂, oxygen vacancies aid CO₂ dissociation, while adjacent metallic Ni domains facilitate H₂ dissociation. The Co@Ni catalyst shows a 30% increase in CO production yield with the CO selectivity of 77% as compared to Ni-TiO₂, likely due to the additional CO₂ activation sites provided by CoO.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the catalytic conversion of carbon dioxide (CO₂) into carbon monoxide (CO) through the reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) reaction offers a promising pathway for establishing a sustainable carbon cycle. This study successfully developed a cobalt-oxide-supported nickel-hydroxide nanoparticle catalyst (Co@Ni), which demonstrated remarkable performance, achieving a CO production yield of approximately 5144 μmol g⁻¹ at 573 K with a CO selectivity of 77%. This performance represents a significant improvement by 30% and 70% higher than those of carbon-supported Ni(OH)₂ (Ni-AC) and cobalt oxide (Co-AC) nanoparticles, respectively. Detailed physical and electrochemical analyses indicate that the exceptional catalytic activity of Co@Ni stems from the electronic interactions between its active sites. Specifically, cobalt-oxide domains act as electron donors, enhancing hydrogen dissociation at nickel sites, while oxygen vacancies in cobalt oxide promote CO₂ adsorption and subsequent dissociation. These results highlight the potential of rationally designing catalysts with synergistic active sites to achieve enhanced efficiency and selectivity for the RWGS reaction.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, 1. The electrochemical analysis methods-note-1; 2. The FT-EXAFS spectra at Ni K-edge; Figure.S1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-Y.C.; methodology, D.B. and T.F.L.; software, D.B..; validation, D.B., A.B., and A.B.; formal analysis, D.B.; investigation, D.B., T.-Y.C; resources, T-Y.C..; data curation, D.B., T.F.L., A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B.; writing—review and editing, D.B., A.B., A.B., and T.-Y.C.; visualization, D.B.; supervision, T.-Y.C.; project administration, T.-Y.C.; funding acquisition, T.-Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the staff of the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC), Hsinchu, Taiwan for the help in various synchrotron-based measurements. T.-Y. Chen acknowledges the funding support from the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (NSTC 113-2112-M-007-014-) and the industrial collaboration projects from the MA-tek (MA-tek 2023-T-004) and the Taiwan Space Agency (TASA-S-1120691). Dinesh Bhalothia acknowledges the funding support (Enhanced Seed Grant) from Manipal University Jaipur.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Triviño, M.L.T.; Arriola, N.C.; Kang, Y.S.; Seo, J.G. Transforming CO2 to valuable feedstocks: Emerging catalytic and technological advances for the reverse water gas shift reaction. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 487, 150369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, P.; Kumar, A.; Khraisheh, M. A Review of CeO2 Supported Catalysts for CO2 Reduction to CO through the Reverse Water Gas Shift Reaction. Catalysts 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalothia, D.; Hsiung, W.-H.; Yang, S.-S.; Yan, C.; Chen, P.-C.; Lin, T.-H.; Wu, S.-C.; Chen, P.-C.; Wang, K.-W.; Lin, M.-W.; et al. Submillisecond Laser Annealing Induced Surface and Subsurface Restructuring of Cu–Ni–Pd Trimetallic Nanocatalyst Promotes Thermal CO2 Reduction. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2021, 4, 14043–14058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalothia, D.; Yang, S.-S.; Yan, C.; Beniwal, A.; Chang, Y.-X.; Wu, S.-C.; Chen, P.-C.; Wang, K.-W.; Chen, T.-Y. Surface anchored atomic cobalt-oxide species coupled with oxygen vacancies boost the CO-production yield of Pd nanoparticles. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2023, 7, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinet-Chinaglia, C.; Shafiq, S.; Serp, P. Low Temperature Sabatier CO2 Methanation. ChemCatChem 2024, n/a, e202401213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacariza, M.C.; Spataru, D.; Karam, L.; Lopes, J.M.; Henriques, C. Promising Catalytic Systems for CO2 Hydrogenation into CH4: A Review of Recent Studies. Processes 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, P.K.; Bhalothia, D.; Beniwal, A.; Tsai, C.-H.; Liu, P.-Y.; Chen, T.-Y.; Ku, H.-M.; Chen, P.-C. Adjacent Reaction Sites of Atomic Mn2O3 and Oxygen Vacancies Facilitate CO2 Activation for Enhanced CH4 Production on TiO2-Supported Nickel-Hydroxide Nanoparticles. Catalysts 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, F.; Rettenmaier, C.; Jeon, H.S.; Roldan Cuenya, B. Transition metal-based catalysts for the electrochemical CO2 reduction: from atoms and molecules to nanostructured materials. Chemical Society Reviews 2020, 49, 6884–6946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, S.; Jha, A.; Shende, P.; Maskara, R.; Das, A.K. Catalytic performance of Co and Ni doped Fe-based catalysts for the hydrogenation of CO2 to CO via reverse water-gas shift reaction. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2019, 7, 102911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Ai, X.; Xie, F.; Zhou, G. Efficient Ni-based catalysts for low-temperature reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) reaction. Chemistry – An Asian Journal 2021, 16, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, P.K.; Bhalothia, D.; Huang, G.-H.; Beniwal, A.; Cheng, M.; Chao, Y.-C.; Lin, M.-W.; Chen, P.-C.; Chen, T.-Y. Sub-Millisecond Laser-Irradiation-Mediated Surface Restructure Boosts the CO Production Yield of Cobalt Oxide Supported Pd Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobadilla, L.F.; Santos, J.L.; Ivanova, S.; Odriozola, J.A.; Urakawa, A. Unravelling the Role of Oxygen Vacancies in the Mechanism of the Reverse Water–Gas Shift Reaction by Operando DRIFTS and Ultraviolet–Visible Spectroscopy. ACS Catalysis 2018, 8, 7455–7467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Arandiyan, H.; Bartlett, S.A.; Trunschke, A.; Sun, H.; Scott, J.; Lee, A.F.; Wilson, K.; Maschmeyer, T.; Schlögl, R.; et al. Inducing synergy in bimetallic RhNi catalysts for CO2 methanation by galvanic replacement. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2020, 277, 119029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Xia, Z.; Hu, X.; Ma, Y.; Qu, Y. Influence of oxygen vacancies of CeO2 on reverse water gas shift reaction. Journal of Catalysis 2022, 414, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Wang, C.-H.; Lin, M.; Bhalothia, D.; Yang, S.-S.; Fan, G.-J.; Wang, J.-L.; Chan, T.-S.; Wang, Y.-l.; Tu, X.; et al. Local synergetic collaboration between Pd and local tetrahedral symmetric Ni oxide enables ultra-high-performance CO2 thermal methanation. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2020, 8, 12744–12756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.-H.; Tu, F.-Y.; Chiu, T.-A.; Wu, T.-T.; Yu, W.-Y. Critical Roles of Surface Oxygen Vacancy in Heterogeneous Catalysis over Ceria-based Materials: A Selected Review. Chemistry Letters 2021, 50, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalothia, D.; Beniwal, A.; Yan, C.; Wang, K.-C.; Wang, C.-H.; Chen, T.-Y. Potential synergy between Pt2Ni4 Atomic-Clusters, oxygen vacancies and adjacent Pd nanoparticles outperforms commercial Pt nanocatalyst in alkaline fuel cells. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 483, 149421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Bhalothia, D.; Huang, G.-H.; Saravanan, P.K.; Wu, Y.; Beniwal, A.; Chen, P.-C.; Tu, X.; Chen, T.-Y. Sub-millisecond pulsed laser engineering of CuOx-decorated Pd nanoparticles for enhanced catalytic CO2 hydrogenation. Catalysis Today 2024, 441, 114891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, H.; Zou, R.; Mahmood, A.; Liang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Gao, S.; Qu, C.; Guo, W.; Guo, S. A Universal Strategy for Hollow Metal Oxide Nanoparticles Encapsulated into B/N Co-Doped Graphitic Nanotubes as High-Performance Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1705441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zhou, G.; Gao, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Zhao, P.; Gao, F. α- and β-Phase Ni-Mg Hydroxide for High Performance Hybrid Supercapacitors. Nanomaterials 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniwal, A.; Bhalothia, D.; Chen, Y.-R.; Kao, J.-C.; Yan, C.; Hiraoka, N.; Ishii, H.; Cheng, M.; Lo, Y.-C.; Tu, X.; et al. Incorporation of atomic Fe-oxide triggers a quantum leap in the CO2 methanation performance of Ni-hydroxide. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 493, 152834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalothia, D.; Lin, C.-Y.; Yan, C.; Yang, Y.-T.; Chen, T.-Y. H2 Reduction Annealing Induced Phase Transition and Improvements on Redox Durability of Pt Cluster-Decorated Cu@Pd Electrocatalysts in Oxygen Reduction Reaction. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 971–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Bhalothia, D.; Chang, H.-W.; Yan, C.; Beniwal, A.; Chang, Y.-X.; Wu, S.-C.; Chen, P.-C.; Wang, K.-W.; Dai, S.; et al. Oxygen vacancies endow atomic cobalt-palladium oxide clusters with outstanding oxygen reduction reaction activity. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 454, 140289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalothia, D.; Yan, C.; Hiraoka, N.; Ishii, H.; Liao, Y.-F.; Chen, P.-C.; Wang, K.-W.; Chou, J.-P.; Dai, S.; Chen, T.-Y. Pt-Mediated Interface Engineering Boosts the Oxygen Reduction Reaction Performance of Ni Hydroxide-Supported Pd Nanoparticles. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2023, 15, 16177–16188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).