Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

11 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

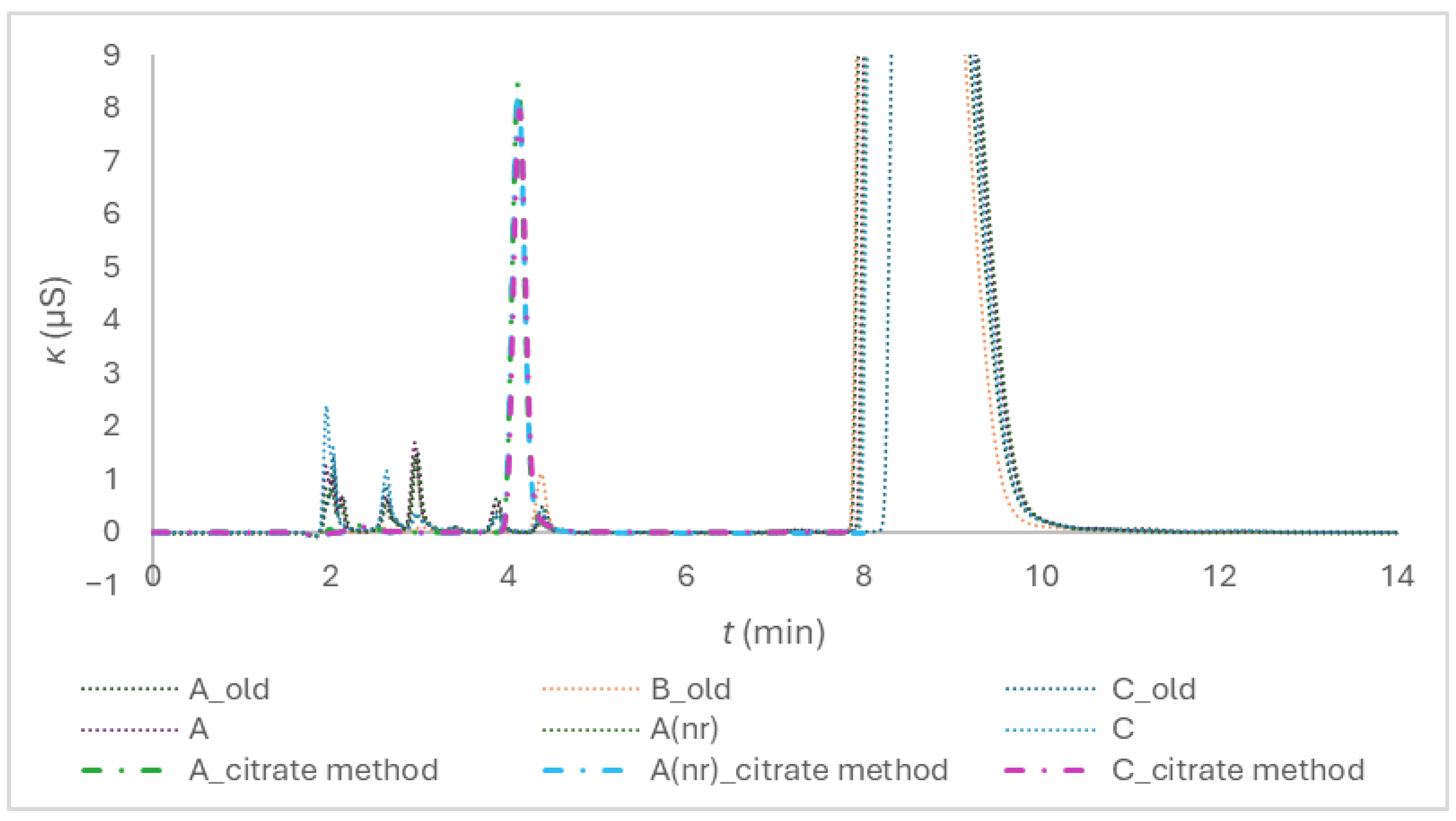

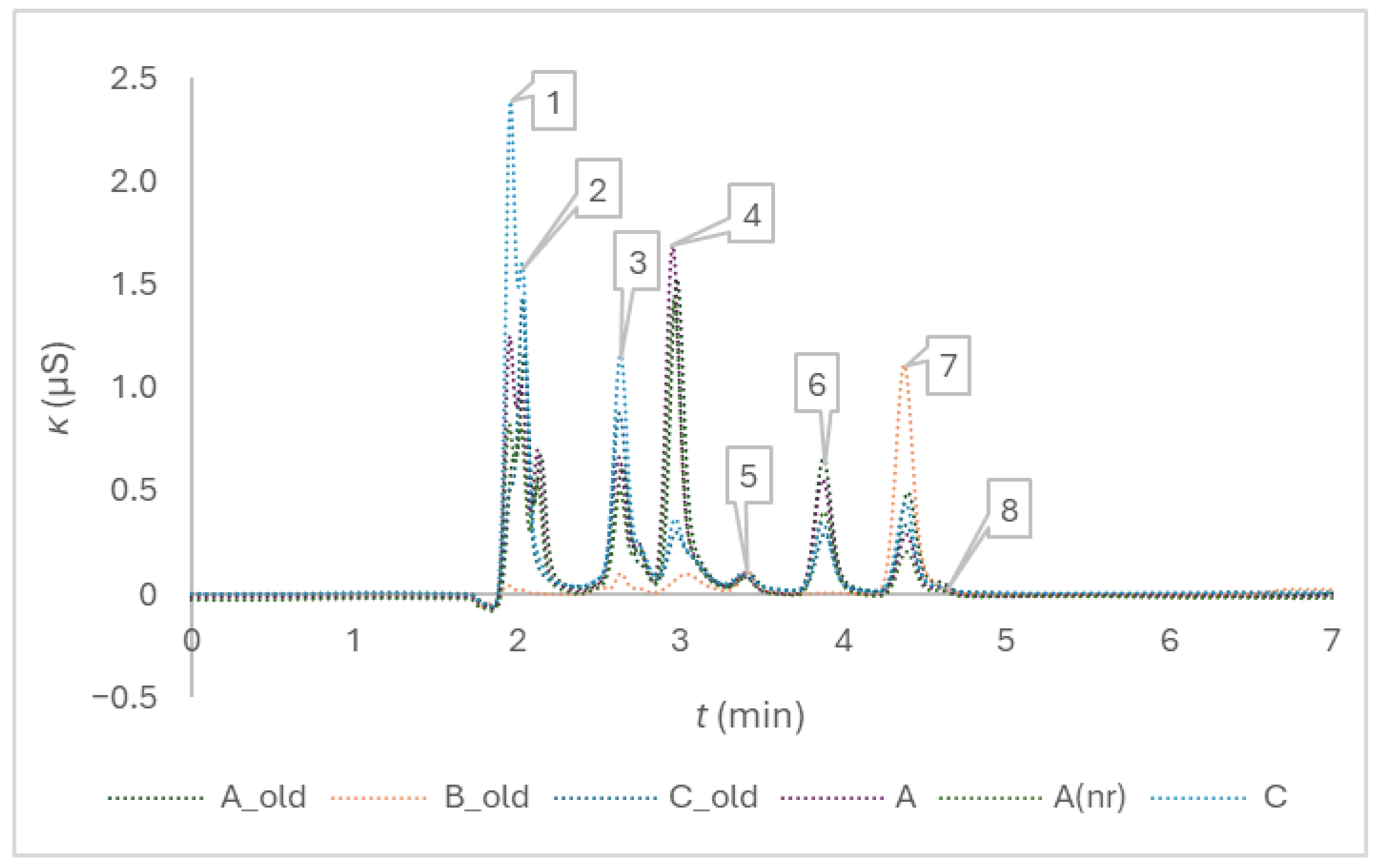

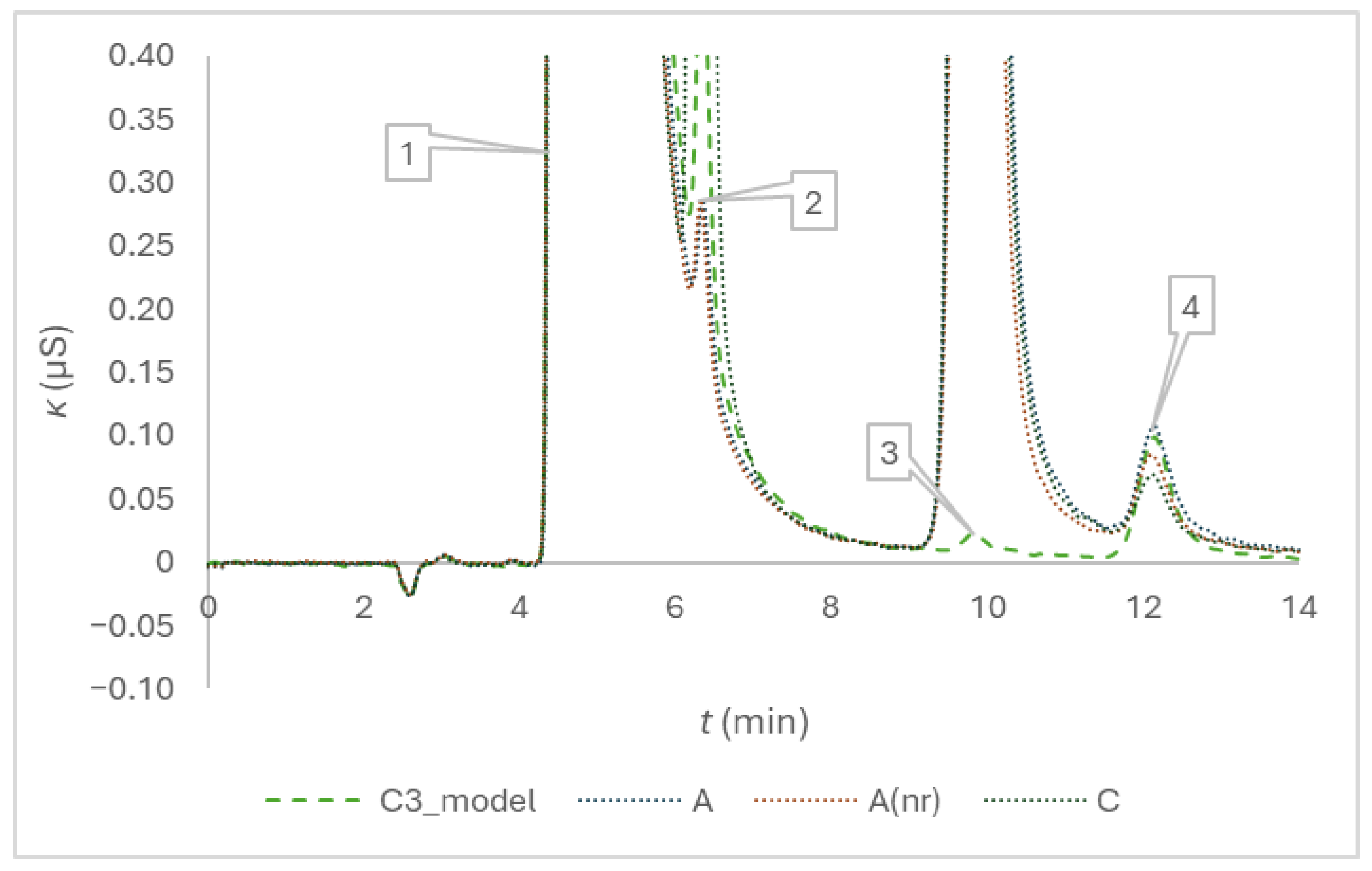

2.1. Anions Determination with Ion Exchange Chromatography—Method Development and Performance

2.2. Cations Determination with Ion Exchange Chromatography—Method Enhancement and Performance

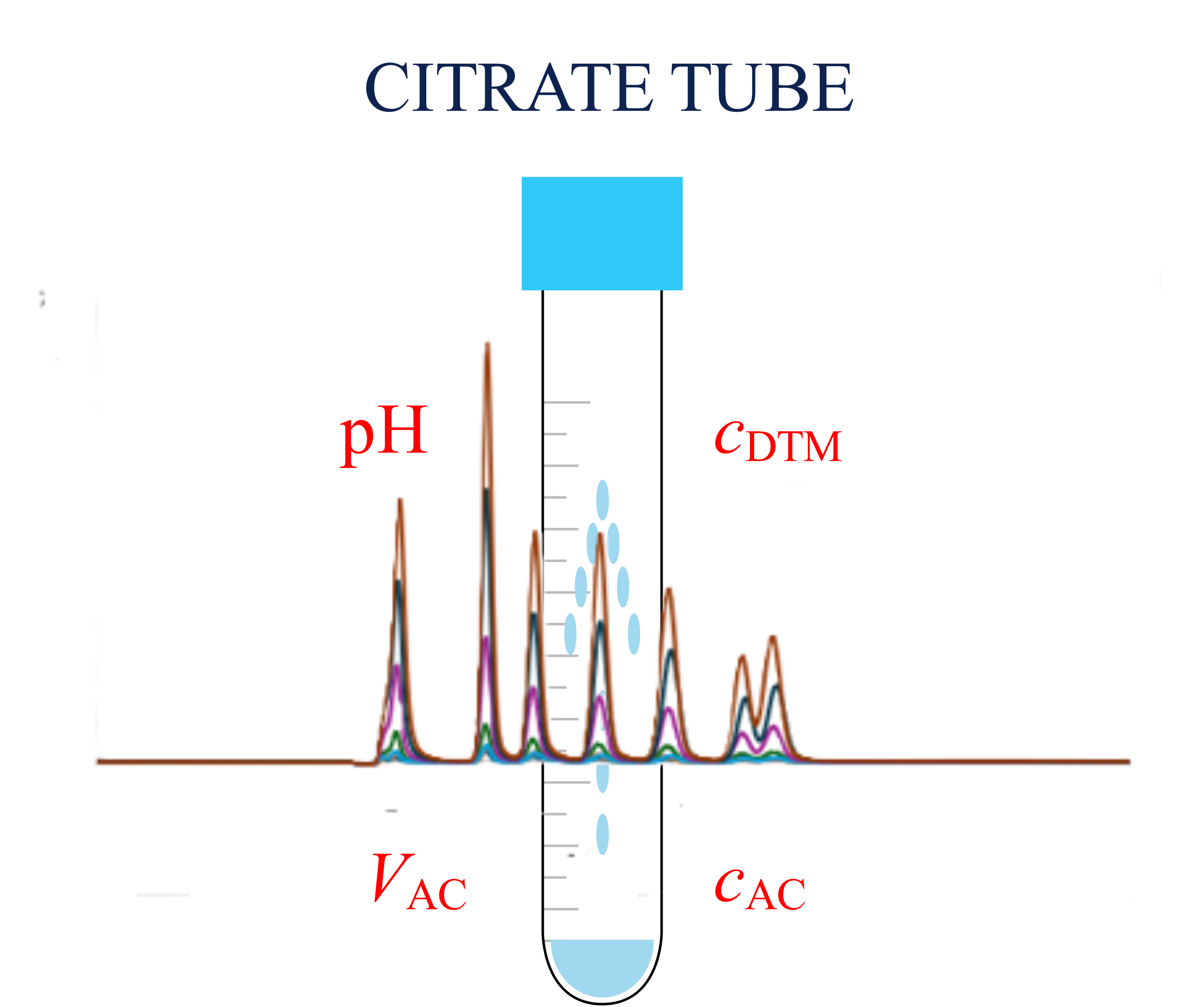

2.4. Determination of Anticoagulant Solution Volume

- Preparation of a working dye solution from a stock dye solution.

- Preparation of calibration solutions from the working dye solution.

- Dye dilution of the working dye solution involving either the examined model solutions or the blood collection tubes.

- Spectrometric measurements, calibration line equation definition, interpolation of the dye mass concentrations from the absorbance measurements pertaining to the examined model solutions or to the blood collection tubes by using the calibration line equation.

- Calculation of the anticoagulant volumes by regarding the experimentally obtained dye dilution insight.

2.4.1. Dye Choice and Calibration

2.4.2. Volume Prediction – Proof-of-Concept and Method Performance

2.4.3. Anticoagulant Volume Determination in Blood Collection Tubes

2.5. Anionic-Cationic Composition

3. Discussion

3.2. Determination of Anticoagulant Solution Volume

- The approach should enable direct spectrometric measurements in blood collection tubes.

- The spectra of a selected dye should not be influenced by changes in citrate media.

- Citrate should be added to the calibration solutions, model solutions, and a blank to mimic the composition of anticoagulant in blood collection tubes to avoid differences in the optical density. The composition should be adjusted so that a dilution with Milli-Q water in a proportion of one to nine results in a solution of pH 6.0. The nominal anticoagulant concentration and volume are assumed to be compliant with the declaration, and the required anticoagulant amount is derived from them.

- The calibration range should be selected so that the linearity of the absorbance dependence on the dye mass concentration is confirmed. The absorbance of the dye solutions corresponding to the dilution with the nominal anticoagulant volume should be evaluated close to the middle of the range and as close to 0.434 as possible.

- Differentiation of volumes around the nominal anticoagulant volume of 200 µL is essential.

3.3. Anionic-Cationic Composition

3.4. Synthesis of Results of the Blood Collection Tubes Quality Evaluation

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Trisodium Citrate, Purified Water, and Evacuated Blood Collection Tubes

4.2. Ion Chromatography

4.2.1. Determination of Anions with Ion Exchange Chromatography

4.2.2. Determination of Cations with Ion Exchange Chromatography

4.3. Determination of pH

4.4. Spectrometric Determination of Anticoagulant Volume Accuracy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mrazek, C.; Lippi, G.; Keppel, M.H.; Felder, T.K.; Oberkofler, H.; Haschke-Becher, E.; Cadamuro, J. Errors within the total laboratory testing process, from test selection to medical decision-making - A review of causes, consequences, surveillance and solutions. Biochemia Medica 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, S.; Adcock, D.M.; Dauer, R.; Kristoffersen, A.H.; Lippi, G.; Mackie, I.; Marlar, R.A.; Nair, S. International Council for Standardization in Haematology (ICSH) recommendations for processing of blood samples for coagulation testing. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2021, 43, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchen, S.; Adcock, D.M.; Dauer, R.; Kristoffersen, A.H.; Lippi, G.; Mackie, I.; Marlar, R.A.; Nair, S. International Council for Standardisation in Haematology (ICSH) recommendations for collection of blood samples for coagulation testing. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2021, 43, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gros, N.; Klobucar, T.; Gaber, K. Accuracy of Citrate Anticoagulant Amount, Volume, and Concentration in Evacuated Blood Collection Tubes Evaluated with UV Molecular Absorption Spectrometry on a Purified Water Model. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gros, N.; Stopar, T. Preanalytical Quality Evaluation of Citrate Evacuated Blood Collection Tubes-Ultraviolet Molecular Absorption Spectrometry Confronted with Ion Chromatography. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patscheke, H. SHAPE AND FUNCTIONAL-PROPERTIES OF HUMAN-PLATELETS WASHED WITH ACID CITRATE. Haemostasis 1981, 10, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germanovich, K.; Femia, E.A.; Cheng, C.Y.; Dovlatova, N.; Cattaneo, M. Effects of pH and concentration of sodium citrate anticoagulant on platelet aggregation measured by light transmission aggregometry induced by adenosine diphosphate. Platelets 2018, 29, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadle, O.W.; Ferguson, T.B.; Gregg, D.E.; Gilford, S.R. EVALUATION OF A NEW CUVETTE DENSITOMETER FOR DETERMINATION OF CARDIAC OUTPUT. Circulation Research 1953, 1, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Gleason, W.L.; McIntosh, H.D. COMPARISON OF CARDIAC OUTPUT DETERMINATION BY DIRECT FICK METHOD AND DYE-DILUTION METHOD USING INDOCYANINE GREEN DYE AND A CUVETTE DENSITOMETER. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1962, 59, 345. [Google Scholar]

- Muroke, V.; Jalanko, M.; Simonen, P.; Holmström, M.; Ventilä, M.; Sinisalo, J. Non-invasive dye dilution method for measuring an atrial septal defect shunt size. Open Heart 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, H.; Goodall, S.R.; Hainsworth, R. REEVALUATION OF EVANS BLUE-DYE DILUTION METHOD OF PLASMA-VOLUME MEASUREMENT. Clin. Lab. Haematol. 1995, 17, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zivkovic, V.; Ridge, N.; Biggs, M.J. Experimental study of efficient mixing in a micro-fluidized bed. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 127, 1642–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, P.K.; Lazarow, A. CALIBRATION OF MICROPIPETTES. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1961, 58, 499. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rideout, J.M.; Renshaw, A.; Snook, M. SWIZZLESTICK - NOVEL POSITIVE DISPLACEMENT MICROLITER DILUTING DEVICE. Anal. Biochem. 1978, 90, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangegaard, M.; Hansen, A.J.; Froslev, T.G.; Morling, N. A Simple Method for Validation and Verification of Pipettes Mounted on Automated Liquid Handlers. Jala 2011, 16, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, C.; Tran, K.; Szewczak, A.A. High-Throughput Quality Control of DMSO Acoustic Dispensing Using Photometric Dye Methods. Jala 2013, 18, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, T.; Hirano, M.; Ishige, Y.; Adachi, S. Development of Liquid Handling Technology for Single Blood Drop Analysis. Bunseki Kagaku 2020, 69, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantakokko, P.; Mustonen, S.; Yritys, M.; Vartiainen, T. Ion chromatographic method for the determination of selected inorganic anions and organic acids from raw and drinking waters using suppressor current switching to reduce the background noise. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Rel. Technol. 2004, 27, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.B.; Sun, X.M.; Shi, C.O.; Zhang, Y.X. Determination of tricarboxylic acid cycle acids and other related substances in cultured mammalian cells by gradient ion-exchange chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection. Journal of Chromatography A 2003, 1012, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.M.; Zhang, S.F.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z.B. Determination of organic acids in the presence of inorganic anions by ion chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection. Journal of Chromatography A 2008, 1192, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenke, D.; Sadain, S.; Nunez, K.; Byrne, F. Performance characteristics of an ion chromatographic method for the quantitation of citrate and phosphate in pharmaceutical solutions. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2007, 45, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, J.B.; Genzel, Y.; Reichl, U. High-performance anion-exchange chromatography using on-line electrolytic eluent generation for the determination of more than 25 intermediates from energy metabolism of mammalian cells in culture. Journal of Chromatography B-Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences 2006, 843, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBorba, B.M.; Rohrer, J.S.; Bhattacharyya, L. Development and validation of an assay for citric acid/citrate and phosphate in pharmaceutical dosage forms using ion chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2004, 36, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waithaisong, K.; Robin, A.; Martin, A.; Clairotte, M.; Villeneuve, M.; Plassard, C. Quantification of organic P and low-molecular-weight organic acids in ferralsol soil extracts by ion chromatography. Geoderma 2015, 257, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, E.H.; Zacharowski, K.; Hintereder, G.; Zierfuss, F.; Raimann, F.; Meybohm, P. Validation of a New Small-Volume Sodium Citrate Collection Tube for Coagulation Testing in Critically Ill Patients with Coagulopathy. Clinical Laboratory 2018, 64, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H. Comparison of Low Voleme and Conventional Sodium Citrate Tubes for Routine Coagulation Testing. Clinical Laboratory 2021, 67, 1555–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagno, G.L.; Demonte, D.; Poli, G.; Favaloro, E.J.; Lippi, G. Impact of low volume citrate tubes on results of first-line hemostasis testing. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2019, 41, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, R.G. Revised Standard Values for Ph Measurements from 0 to 95 Degrees C. J Res Nbs a Phys Ch 1962, 66, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.J.; Zheng, O.Y.; Liu, J.; Jemal, M. The use of a dual dye photometric calibration method to identify possible sample dilution from an automated multichannel liquid-handling system. Clin. Lab. Med. 2007, 27, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, A.C.; Lovich, M.A.; Parker, M.J.; Zheng, H.; Peterfreund, R.A. Delivery interaction between co-infused medications: an in vitro modeling study of microinfusion. Pediatric Anesthesia 2013, 23, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousvaros, G.A.; Sekelj, P.; McGregor, M.; Palmer, W.H. COMPARISON OF CENTRAL AND PERIPHERAL INJECTION SITES IN ESTIMATION OF CARDIAC OUTPUT BY DYE DILUTION CURVES. Circulation Research 1963, 12, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.C.; Carroll, R.L. Anticoagulant Solution for Use in Blood Chemistry-Related Techniques and Apparatus. 5,667,963, 1997.

- Crea, F.; De Stefano, C.; Millero, F.J.; Crea, F. Dissociation constants for citric acid in NaCl and KCl solutions and their mixtures at 25°C. J. Solution Chem. 2004, 33, 1349–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, R.C.; Bowyer, A.; Favaloro, E.J.; Johnsen, J.M.; Lippi, G.; Marlar, R.A.; Neeves, K.; Rollins-Raval, M.A. Guidance on the critical shortage of sodium citrate coagulation tubes for hemostasis testing. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 2857–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lito, M.; Camoes, M.; Covington, A.K. Effect of citrate impurities on the reference pH value of potassium dihydrogen buffer solution. Anal. Chim. Acta 2003, 482, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Repetition | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | s | sr(%) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tubes | tr (min) | |||||||

| A | 4.243 | 4.220 | 4.227 | 4.230 | 4.230 | 4.230 | 0.008 | 0.2 |

| C | 4.163 | 4.213 | 4.170 | 4.217 | 4.217 | 4.196 | 0.03 | 0.6 |

| A(nr) | 4.173 | 4.183 | 4.173 | 4.177 | 4.193 | 4.180 | 0.008 | 0.2 |

| Tubes | Peak area (AU) | |||||||

| A | 1.4506 | 1.4455 | 1.4414 | 1.4538 | 1.4509 | 1.4484 | 0.0049 | 0.34 |

| C | 1.3729 | 1.3692 | 1.3726 | 1.3729 | 1.3728 | 1.3732 | 0.00099 | 0.07 |

| A(nr) | 1.4595 | 1.4618 | 1.4623 | 1.4598 | 1.4624 | 1.4612 | 0.0014 | 0.10 |

| Date | a | sa | b | sb | sy/x | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 April 2025 | 0.0639 | 0.0013 | 0.1039 | 0.0290 | 0.0276 | 0.9988 |

| 3 April 2025 | 0.0654 | 0.0017 | 0.0741 | 0.0392 | 0.0374 | 0.9979 |

| 7 April 2025 | 0.0653 | 0.0012 | 0.0969 | 0.0265 | 0.0253 | 0.9990 |

| 8 April 2025 | 0.0640 | 0.0021 | 0.1207 | 0.0476 | 0.0454 | 0.9968 |

| 9 April 2025 | 0.0645 | 0.0017 | 0.1179 | 0.0382 | 0.0364 | 0.9980 |

| 10 April 2025 | 0.0639 | 0.0010 | 0.0448 | 0.0234 | 0.0223 | 0.9992 |

| 11 April 2025 | 0.0652 | 0.0015 | 0.0877 | 0.0349 | 0.0333 | 0.9983 |

| 15 April 2025 | 0.0638 | 0.0011 | 0.1109 | 0.0260 | 0.0248 | 0.9990 |

| 7 May 2025 | 0.0586 | 0.0011 | 0.0778 | 0.0256 | 0.0244 | 0.9989 |

| 8 May 2025 | 0.0600 | 0.0008 | 0.0840 | 0.0184 | 0.0175 | 0.9995 |

| 9 May 2025 | 0.0595 | 0.0009 | 0.0946 | 0.0205 | 0.0195 | 0.9993 |

| 14 May 2025 | 0.0601 | 0.0013 | 0.1073 | 0.0291 | 0.0277 | 0.9987 |

| 3 June 2025* | 0.0624 | 0.0009 | 0.1184 | 0.0202 | 0.0192 | 0.9994 |

| 4 June 2025* | 0.0631 | 0.0013 | 0.0967 | 0.0286 | 0.0272 | 0.9988 |

| 5 June 2025* | 0.0626 | 0.0012 | 0.0961 | 0.0267 | 0.0254 | 0.9990 |

| 6 June 2025* | 0.0636 | 0.0012 | 0.0796 | 0.0265 | 0.0253 | 0.9990 |

| 16 June 2025* | 0.0641 | 0.0014 | 0.1099 | 0.0308 | 0.0293 | 0.9987 |

| 23 July 2025* | 0.0614 | 0.0011 | 0.0991 | 0.0255 | 0.0243 | 0.9990 |

| 24 July 2025* | 0.0624 | 0.0012 | 0.1046 | 0.0265 | 0.0253 | 0.9990 |

| 25 July 2025* | 0.0622 | 0.0011 | 0.1056 | 0.0244 | 0.0233 | 0.9991 |

| Date | τ (mmol/L) | Mean (mmol/L) (n = 3) | s (mmol/L) | sx0/x0 | B (mmol/L) | Br(%) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 April 2025 | 0.0655 | 0.0650 | 0.0002 | 0.038 | −0.0005 | −0.8 |

| 16 June 2025 | 0.1092 | 0.1108 | 0.0003 | 0.016 | 0.0016 | 1.4 |

| 14 May 2025 | 0.1525 | 0.1532 | 0.0007 | 0.013 | 0.0007 | 0.4 |

| 3 June 2025 | 0.1092 | 0.1113 | 0.0007 | 0.011 | 0.0021 | 1.9 |

| 25 July 2025 | 0.1091 | 0.1108 | 0.0002 | 0.013 | 0.0017 | 1.6 |

| Repetition | 1. | 2. | 3. | s | sr(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tubes | tr (min) | |||||

| A | 5.25 | 5.24 | 5.25 | 5.247 | 0.006 | 0.1 |

| C | 5.21 | 5.22 | 5.22 | 5.217 | 0.006 | 0.1 |

| A(nr) | 5.26 | 5.26 | 5.27 | 5.263 | 0.006 | 0.1 |

| Tubes | Peak area (AU) | |||||

| A | 2.401 × 108 | 2.393 × 108 | 2.407 × 108 | 2.400 × 108 | 7.2 × 105 | 0.30 |

| C | 2.237 × 108 | 2.275 × 108 | 2.280 × 108 | 2.264 × 108 | 2.4 × 106 | 1.0 |

| A(nr) | 2.371 × 108 | 2.381 × 108 | 2.387 × 108 | 2.380 × 108 | 8.4 × 105 | 0.35 |

| Date | a | sa | b | sb | sy/x | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 June 2025 | 3.779 × 105 | 1.174 × 104 | −3.723 × 106 | 4.193 × 106 | 1.857 × 106 | 0.9971 |

| 4 June 2025 | 3.785 × 105 | 1.717 × 103 | −1.575 × 106 | 6.129 × 105 | 2.714 × 105 | 0.9999 |

| 5 June 2025 | 3.597 × 105 | 6.208 × 103 | 4.023 × 106 | 2.217 × 106 | 9.815 × 105 | 0.9991 |

| 23 July 2025 | 3.550 × 105 | 2.511 × 103 | 1.754 × 106 | 8.966 × 105 | 3.970 × 105 | 0.9999 |

| 24 July 2025 | 3.563 × 105 | 4.198 × 103 | 1.795 × 106 | 1.499 × 106 | 6.637 × 105 | 0.9996 |

| 25 July 2025 | 3.576 × 105 | 2.799 × 103 | 1.287 × 106 | 9.994 × 105 | 4.426 × 105 | 0.9998 |

| Date | τ (mmol/L) | Mean (mmol/L) (n = 3) | s (mmol/L) | sx0/x0 | B (mmol/L) | Br(%) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 June 2025* | 15.22 | 15.17 | 0.06 | 0.0012 | −0.05 | −0.3 |

| 4 June 2025* | 15.22 | 15.16 | 0.03 | 0.00018 | −0.06 | −0.4 |

| 5 June 2025* | 15.22 | 15.23 | 0.04 | 0.00069 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| 23 July 2025** | 16.36 | 16.18 | 0.30 | 0.00027 | −0.18 | −1.1 |

| 24 July 2025** | 16.36 | 16.40 | 0.005 | 0.00045 | 0.04 | 0.2 |

| 25 July 2025** | 16.36 | 16.09 | 0.46 | 0.00030 | −0.27 | −1.7 |

| pH | A | A(nr) | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured | 5.948 | 5.901 | 6.115 |

| 5.964 | 5.896 | 6.125 | |

| 5.940 | 5.891 | 6.122 | |

| 5.900 | 5.903 | 6.157 | |

| 5.912 | 5.878 | 6.134 | |

| Mean Standard deviation |

5.93 | 5.89 | 6.13 |

| 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Series | a | sa | b | sb | sy/x | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tartrazine, citrate | 0.0462 | 0.0005 | −0.0364 | 0.0060 | 0.0035 | 0.9994 |

| Tartrazine, citrate, pH | 0.0437 | 0.0012 | −0.0080 | 0.0146 | 0.0085 | 0.9962 |

| Erioglaucine, citrate | 0.1234 | 0.0035 | −0.0233 | 0.0144 | 0.0144 | 0.9960 |

| Erioglaucine, citrate, pH | 0.1206 | 0.0021 | 0.0076 | 0.0088 | 0.0056 | 0.9984 |

| Series 0 | 0.1205 | 0.0010 | −0.0106 | 0.0042 | 0.0027 | 0.9997 |

| Series 1 | 0.1164 | 0.0035 | 0.0006 | 0.0144 | 0.0092 | 0.9956 |

| Series 2 | 0.1179 | 0.0035 | −0.0021 | 0.0143 | 0.0092 | 0.9957 |

| Series 3 | 0.1134 | 0.0011 | 0.0134 | 0.0046 | 0.0030 | 0.9995 |

| Parameter | 150 μL | 180 μL | 200 μL | 220 μL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAC_1_esitmated (μL) | 157.83 | 197.05 | 213.54 | 229.59 |

| VAC_2_esitmated (μL) | 163.27 | 183.77 | 208.36 | 217.47 |

| VAC_3_esitmated (μL) | 146.22 | 177.92 | 198.28 | 216.15 |

| VAC_4_esitmated (μL) | − | 181.42 | 198.28 | 213.54 |

| n | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Mean | 155.8 | 185.0 | 204.6 | 219.2 |

| s | 8.7 | 8.4 | 7.6 | 7.1 |

| sr(%) (%) | 5.6 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 3.3 |

| B (µL) | 5.77 | 5.04 | 4.62 | −0.81 |

| Br(%) (%) | 3.85 | 2.80 | 2.31 | −0.37 |

| tcalculated | 1.148 | 1.206 | 1.213 | 0.226 |

| p-value | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.83 |

| Series | 150 μL | 180 μL | 200 μL | 220 μL | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | −9.4 | 1.6 | −2.3 | 0.6 |

0.21 |

| 2.2 | 0.3 | −6.2 | 5.7 | ||

| −4.6 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.3 | ||

|

S2 |

1.6 | 4.9 | 0.4 | −5.9 |

0.26 |

| 2.9 | 0.3 | −2.3 | −2.3 | ||

| 0.3 | −4.1 | 1.7 | −1.6 | ||

|

S3 |

1.0 | −3.2 | 1.9 | −1.3 |

0.81 |

| −2.2 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.4 | ||

| 2.9 | −1.3 | −2.9 | 2.4 | ||

| p-value | 0.24 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.06 |

| Tube-brands | Count | Sum | Average | Variance | Differences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 9 | 1708 | 189.8 | 27.4 | * | ||||

| C | 9 | 1600 | 177.8 | 257 | * | ||||

| A(nr) | 9 | 1725 | 191.7 | 23.6 | * | ||||

| Tubes | Sodum ion, cNa (mmol/L) | Citrate, cDTM (mmol/L) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 27.980 | 29.040 | 28.531 | 28.215 | 28.743 | 27.918 | 11.71 | 11.65 | 11.57 | 11.35 | 11.15 | 11.56 |

| A(nr) | 28.986 | 26.366 | 27.400 | 28.195 | 28.591 | 27.922 | 12.25 | 10.74 | 11.16 | 11.78 | 11.46 | 11.56 |

| C | 26.699 | 27.545 | 26.617 | 26.877 | 26.744 | 28.748 | 11.11 | 10.94 | 10.71 | 10.90 | 10.78 | 11.37 |

| Tubes | sx0/x0 | |||||||||||

| A | 4 × 10−3 | 4 × 10−3 | 6 × 10−3 | 6 × 10−3 | 4 × 10−3 | 4 × 10−3 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| A(nr) | 4 × 10−3 | 4 × 10−3 | 7 × 10−3 | 6 × 10−3 | 4 × 10−3 | 4 × 10−3 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| C | 4 × 10−3 | 4 × 10−3 | 7 × 10−3 | 7 × 10−3 | 5 × 10−3 | 4 × 10−3 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Tubes | Year |

c (C2H3O2−) ± s (n = 3) |

c (HCOO−) ± s (n = 3) |

c (Cl−) ± s (n = 3) |

c (NO2−) ± s (n = 3) |

c (SO42−) ± s (n = 3) |

c (C2O42−) ± s (n = 3) |

c (Br−) ± s (n = 3) |

c (NO3−) ± s (n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tR (min) | 1.980 | 2.045 | 2.650 | 2.972 | 3.418 | 3.885 | 4.392 | 4.601 | |

| A_old | 2024 | (6 ± 1) ×10 | 34 ± 2 | 41 ± 5 | 76 ± 4 | 7 ± 2 | 21 ± 3 | 31 ± 4 | 5.6 ± 0.2 |

| C_old | 2023 | 8 ± 1 | − | 48 ± 2 | − | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 8.6 ± 0.2 | 14.3 ± 0.3 |

| B_old | 2024 | − | − | − | − | 6.95 ± 0.04 | − | 7.39 | − |

| C | 2025 | 1.72 | − | 56.3 ± 0.9 | − | 7.3 ± 0.9 | 3 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 | 14 ± 2 |

| A | 2026 | 114 ± 7 | 24 ± 1 | 31 ± 3 | 66.9 ± 0.2 | 3.63 ± 0.02 | 16.01 ± 0.02 | 21 ± 1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 |

| A(nr) | 2026 | 71 ± 3 | 21.4 ± 0.5 | 19.62 ± 0.08 | 56.5 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 12.0 ± 0.3 | 17.9 ± 0.1 | − |

| Parameter | A | A(nr) | C | τ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEAN cDTM (mmol/L) | 11.5 | 11.5 | 11.0 | 10.9 |

| s (mmol/L) | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | — |

| sr(%) (%) | 1.8 | 4.5 | 2.2 | — |

| Br(%) (%) | 5.5 | 5.4 | 0.6 | — |

| MEAN VAC (µL) | 190 | 192 | 178 | 200 |

| s (µL) | 5 | 5 | 16 | — |

| sr(%) (%) | 2.8 | 2.5 | 9.0 | — |

| Br(%) (%) | −5.1 | −4.2 | −11 | — |

| MEAN fAC_dil (1) | 10.5 | 10.4 | 11.1 | 10 |

| Br(%) (%) | 4.8 | 3.9 | 11 | |

| MEAN cAC (mmol/L) | 121 | 119 | 122 | 109 |

| s (mmol/L) | 2 | 5 | 3 | — |

| sr(%) (%) | 1.8 | 4.5 | 2.2 | — |

| Br(%) (%) | 11 | 9.5 | 12 | — |

| MEAN nAC (µmol) | 22.9 | 22.9 | 21.7 | 21.8 |

| Br(%) (%) | 5.0 | 5.0 | −0.5 | — |

| MEAN cK (mol/L) | * | * | 0.131 (n = 6)** | — |

| MEAN cMg (mmol/L) | * | * | 0.233 (n = 4)** | — |

| MEAN cCa(mmol/L) | 0.007 (n = 3)** | 0.004 (n = 3)** | 0.004 (n = 1)** | — |

| Abbreviation | Anticoagulant c (mmol/L) |

Expiration Date | Draw Volume (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A_old** | 109 | 4 July 2024 | 1.8 |

| B_old** | 109 | 31 January 2024 | 1.8 |

| C_old** | 109* | 31 December 2023 | 1.8 |

| A | 109 | 1 February 2026 | 1.8 |

| A(nr) | 109 | 1 February 2026 | 1.8 |

| C | 109* | August 2025 | 1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).