1. Introduction

The 5-year mortality rate for patients undergoing hemodialysis (HD) is 50%, with most deaths attributed to cardiovascular causes, especially non-atherothrombotic events [

1]. Hemodiafiltration (HDF) offers a survival advantage over HD [

2,

3], but a significant residual risk remains. Inflammation, endothelial damage, vascular calcification, and myocardial structural changes are significant factors contributing to this high mortality rate. Therefore, it is essential for nephrologists to consistently seek strategies to improve the cardiovascular outlook for these patients.

The dialysate plays a crucial role in the HD treatment. Its components determine the direction and final concentration of solute diffusive exchange through the semipermeable membrane. One crucial component is the dialysate buffer. Although acetate is the most commonly used one, its use can elevate blood levels beyond the normal physiological range, leading to reduced dialysis tolerance [

4,

5], inflammation [

6,

7], oxidative stress [

8], hemodynamic instability [

4,

9], and cardiovascular alterations [

10,

11]. As a result, researchers have studied alternative buffers to replace acetate, with citrate being the most extensively researched and widely used.

Citrate offers several advantages beyond being an acetate-free dialysate. It has been associated with lower levels of inflammatory markers [

6,

12,

13,

14], improved dialysis tolerance [

4,

15,

16,

17], less dialyzer clotting [

18], and potential reduction of vascular calcification [

10,

19]. Despite these benefits, its use has not yet become widespread in centers, primarily due to concerns and uncertainties about the clinical effects of the citrate chelation of calcium and magnesium. For instance, 1 mmol/L of citrate can bind 1.5 mmol/L of both cations [

20]. It is through its calcium-chelating capacity that this dialysate manages to reduce heparin expenditure and dialyzer coagulation, as calcium plays a role in the coagulation pathway [

21].

There have been several observational studies that found a correlation between magnesium levels and mortality in patients undergoing HD. Concentrations of magnesium ranging from 2.5 to 2.8 mg/dL have been linked to improved survival [

22,

23]. The use of citrate instead of acetate can cause a marked reduction in blood magnesium levels [

24]. Therefore, magnesium supplementation during citrate dialysis could help prevent hypomagnesemia, potentially providing a survival advantage for these patients. However, this hypothesis has yet to be confirmed by interventional studies [

25].

Citrate is also believed to reduce inflammation by binding iron or copper, reducing their ability to act as cofactors in activating the complement pathway [

17,

26]. However, these beneficial effects have failed to prove improved survival outcomes [

24,

27]. Nevertheless, no data is available on this subject, and it is unknown whether the supplementation of another divalent metal will affect the amount of citrate-bonded calcium levels or other metals.

Some manufacturers offer a higher concentration of calcium and magnesium in citrate dialysates (CD) as an intention to supplement them and, thus, counteract citrate's ability to bind these two metals. Acetate dialysates (AD) are usually available with a calcium concentration of either 1.5 (AD-Ca1.5) or 1.25 (AD-Ca1.25) mmol/L and a fixed one of magnesium of 0.5 mmol/L. In contrast, CD are available with a calcium supplement of 1.5, 1.65, or 1.75 mmol/L and a variable magnesium supplement of either 0.5 (CD-Mg0.5) or 0.75 mmol/L (CD-Mg0.75).

This study aims to examine and compare the impact of CD with or without magnesium supplementation versus AD in HDF on chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD) biomarkers and other divalent metals with a potential role in inflammation.

2. Results

Seventy-two HDF sessions were performed in 18 patients, receiving each patient one session with each dialysate. Thirteen patients were male (72%), the median age was 80 (69 - 83) years, 12 had an AVF as vascular access (66.7%), and the causes for CKD were urologic (6, 33.3%), diabetes mellitus (3, 16.7%), glomerulonephritis (3, 16.7%), autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (1, 5.6%), multiple myeloma (1, 5.6%), cardiorenal (1, 5.6%), and unknown (3, 16.7%). Every patient used the FX60 CorDiax™ dialyzer. Low-molecular-weight heparin was the most used anticoagulant (55.5%), followed by unfractionated heparin (27.8%), and no anticoagulant being used in 16% of the sessions. There were no differences in the blood flow (Qb), dialysate fluid flow (Qd), dialysis session length, ultrafiltration, recirculation, replacement and total treated blood volume, anticoagulation dose used, lowest relative blood volume, and pre- and post-dialysis systolic and diastolic blood pressures. There were also no significant differences between pre- and post-dialysis creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and albumin, nor in their reduction ratios. Also, there were no statistically significant differences in Kt or blood pressure with either dialysate. Refer to

Table 1 for further details.

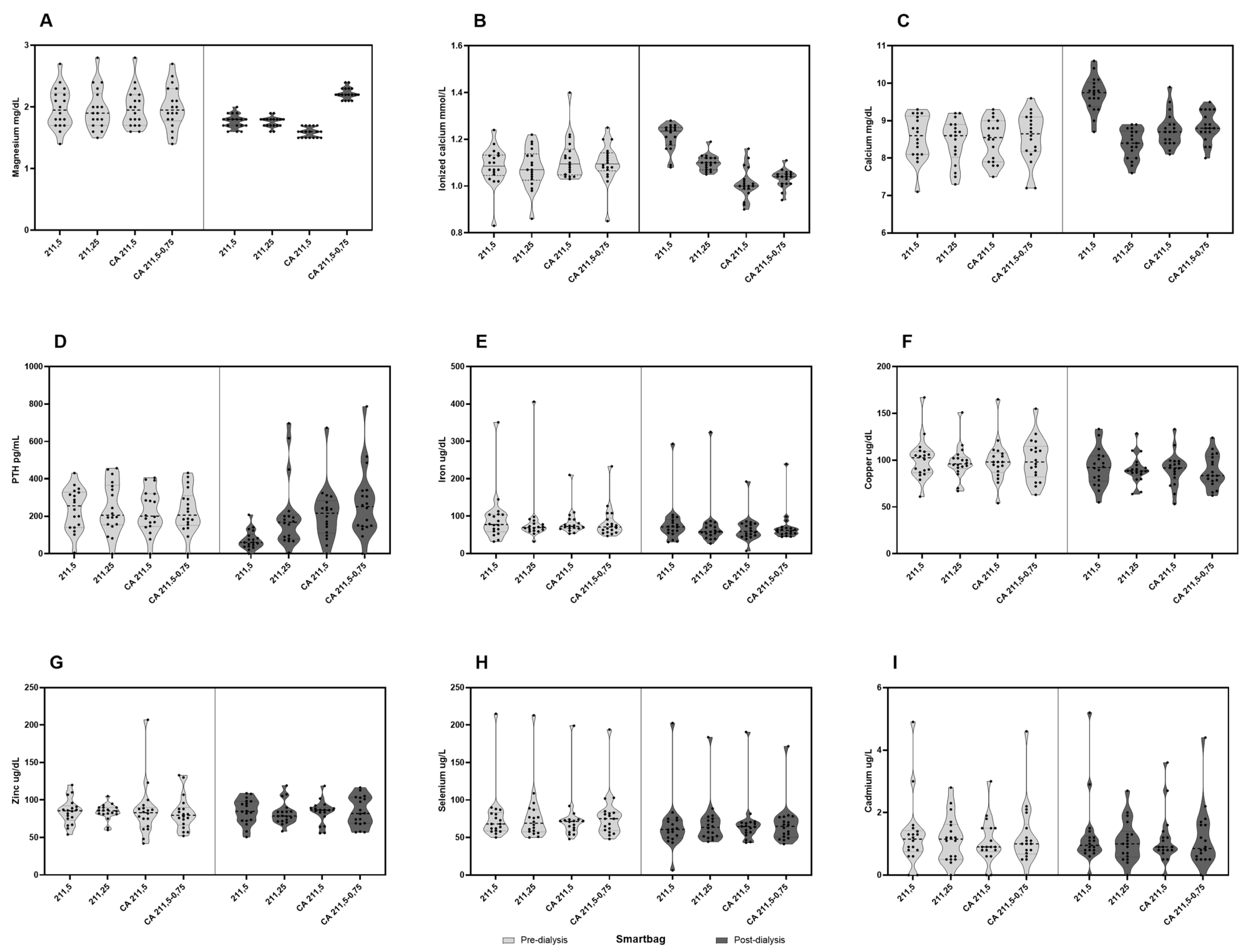

2.1. Calcium and CKD-MBD Biomarkers

There were no differences in pre-dialysis values of total and ionized calciums, intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), and phosphorus. Regarding post-dialysis values, we found that total calcium increased with AD-Ca1.5, CD-Mg0.5 (1.16 ± 0.66 and 0.28 ± 0.51 mmol/L, respectively, both with a p-value < 0.001), and CD-Mg0.75 (0.29 ± 0.55 mmol/L, p=0.006), while it decreased with AD-Ca1.25, though not significantly (-0,07 ± 0,48 mmol/L, p=0.224). In contrast, post-dialysis ionized calcium significantly decreased with both CD-Mg0.5 (-0.11 ± 0.1 mmol/L, p<0.001) and CD-Mg0.75 (-0.07 ± 0.09 mmol/L, p= 0.006), increased with AD-Ca1.5 (0.13 ± 0.08 mmol/L, p<0.001), and remained stable with AD-Ca1.25 (0,02 ± 0,08 mmol/L, p= 0.224). See

Figure 1.

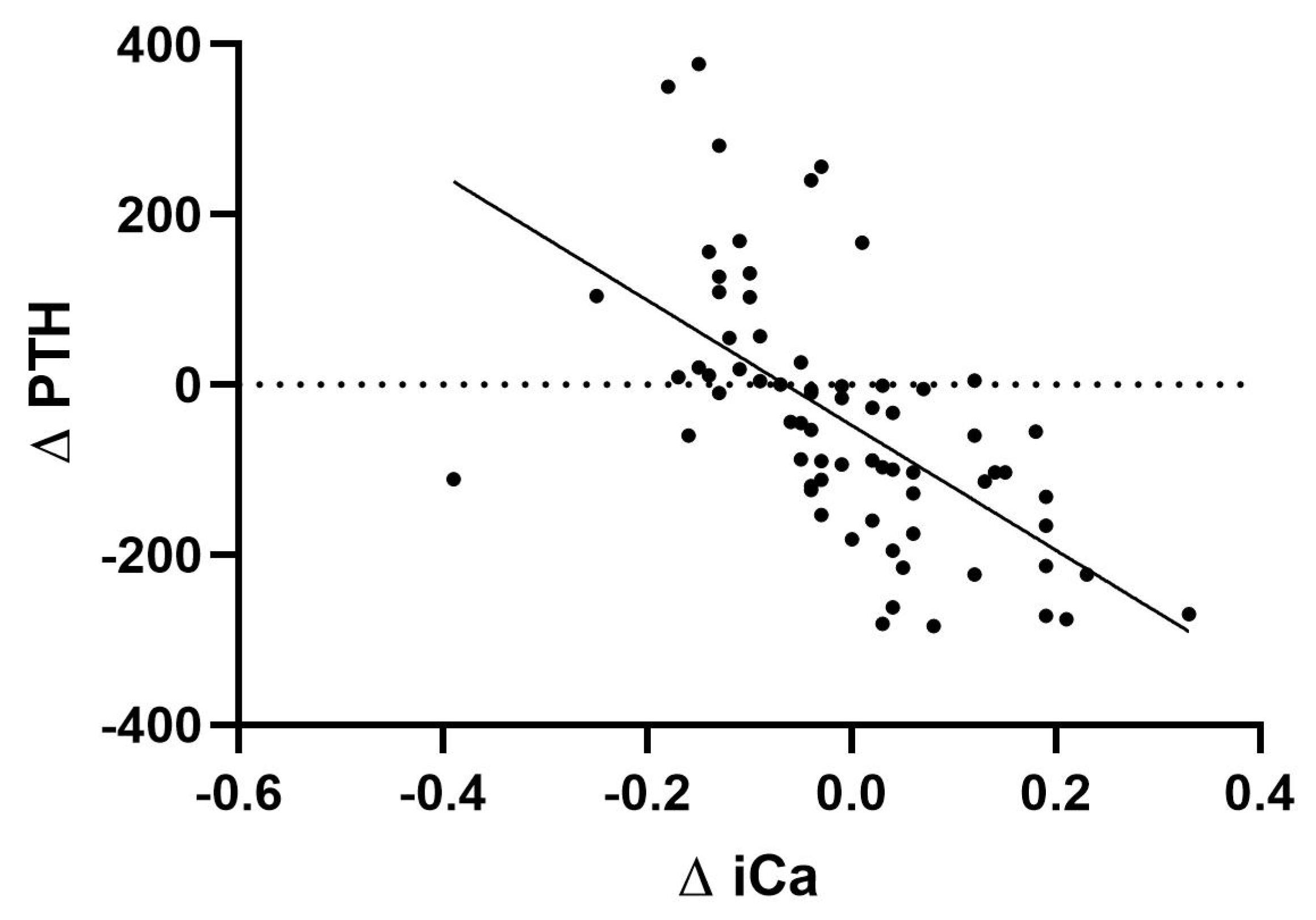

Regarding iPTH levels, we found that they remained stable, without significant differences between the pre- and post-dialysis values with CD-Mg0.5 (228.78 ± 27.14 and 214.28 ± 34.97, p= 0.33), CD-Mg0.75 (229.83 ± 27.21 and 269.5 ± 43.53, p= 0.28), and AD-Ca1.25 dialysates (244.83 ± 31.83 and 207.78 ± 44.79, p= 0.33). It was only significantly lowered with AD-Ca1.5 (238.44 ± 26.46 and 74.28 ± 11.93, p<0.001). Notably, there were four instances with post-dialysis iPTH values above 600 pg/mL, three from the same patient. There was a significant correlation between the difference between pre- and post-dialysis iPTH values and pre- and post-dialysis ionized calcium values (

Figure 2) (r

2=0.378, p<0.001).

Finally, post-dialysis phosphorus levels significantly decreased compared with pre-dialysis ones (-2.28 ± 2.1, -2.47 ± 0.18, -2.53 ± 0.18, and -2.19 ± 0.37, with all comparisons with a p-value < 0.001) without differences between the four studied dialysates (AD-Ca1.5, AD-Ca1-25, CD-Mg0.5, and CD-Mg0.75, respectively). The main results on CKD-MBD variables are summarized in

Table 2.

2.2. Magnesium

There were no significant differences between magnesium pre-dialysis values. However, its post-dialysis levels were significantly reduced with AD-Ca1.5 (-0.22 ± 0.07, p= 0.006), AD-Ca1.25 (-0.21 ± 0.07, p= 0.006), and CD-Mg0.5 (-0.39 ± 0.07, p<0.001). The latter was significantly lower than the former (p<0.001). In the case of the magnesium-supplemented citrate dialysate (CD-Mg0.75), post-dialysis magnesium levels increased significantly from the pre-dialysis ones (0.23 ± 0.07, p= 0.005).

2.3. Cadmium, Selenium, Copper, Zinc, and Iron

There were no differences among the pre-dialysis values for any of these metals. When analyzing by each dialysate (AD-Ca1.5, AD-Ca1.25, CD-Mg0.5, and CD-Mg0.75), selenium (-11.33 ± 3.47, -9.19 ± 1.99, -6.14 ± 1.65, -11.21 ± 1.71), copper (-8.56 ± 1.84, -7.72 ± 1.66, -8.64 ± 1.88, -12.01 ± 1.93), and iron (-14.07 ± 19.09, -14.24 ± 22.02, -16.63 ± 15.69, -11.46 ± 13.93) serum levels significantly decreased post-dialysis with all dialysates with no differences between them. Cadmium and zinc remained similar after dialysis, with all four dialysates having no differences between them.

Table 2.

CKD-MBD parameters.

Table 2.

CKD-MBD parameters.

| Variable |

SmartBag

211,25 |

SmartBag

211,5 |

SmartBag

CA 211,5 |

SmartBag

CA 211,5-0,75 |

P value |

| Total calcium (mg/dL) |

448.89 ± 1.11 |

444.44 ± 3.81 |

447.22 ± 2.78 |

446.11 ± 2.93 |

0.364 |

| Pre-dialysis |

8.44 ± 0.59 |

8.54 ± 0.59 |

8.49 ± 0.56 |

8.55 ± 0.67 |

0.139 |

| Post-dialysis |

8.38 ± 0.4 |

9.71 ± 0.47 |

8.77 ± 0.46 |

8.84 ± 0.41 |

< 0.001 |

| Variation |

-0.07 ± 0.48 |

1.16 ± 0.66 |

0.28 ± 0.51 |

0.29 ± 0.55 |

< 0.001 |

| Ionized calcium (mmol/L) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Pre-dialysis |

1.08 ± 0.09 |

1.08 ± 0.09 |

1.12 ± 0.09 |

1.1 ± 0.09 |

0.114 |

| Post-dialysis |

1.1 ± 0.03 |

1.21 ± 0.06 |

1.01 ± 0.07 |

1.03 ± 0.04 |

<0.001 |

| Variation |

0.02 ± 0.08 |

0.13 ± 0.08 |

-0.11 ± 0.1 |

-0.07 ± 0.09 |

<0.001 |

| Parathormone (pg/mL) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Pre-dialysis |

244.83 ± 31.83 |

238.44 ± 26.46 |

228.78 ± 27.14 |

229.83 ± 27.21 |

0.785 |

| Post-dialysis |

207.78 ± 44.79 |

74.28 ± 11.93 |

214.28 ± 34.97 |

269.5 ± 43.53 |

<0.001 |

| Variation |

-37.06 ± 36.96 |

-164.17 ± 21.73 |

-12.5 ± 26.02 |

39.67 ± 35.55 |

<0.001 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Pre-dialysis |

3.86 ± 0.21 |

3.81 ± 0.23 |

3.82 ± 0.21 |

3.85 ± 0.18 |

0.984 |

| Post-dialysis |

1.39 ± 0.06 |

1.53 ± 0.07 |

1.28 ± 0.06 |

1.66 ± 0.33 |

0.424 |

| Variation |

-2.47 ± 0.18 |

-2.28 ± 2.1 |

-2.53 ± 0.18 |

-2.19 ± 0.37 |

0.622 |

| Magnesium (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Pre-dialysis |

1.97 ± 0.08 |

1.98 ± 0.8 |

1.98 ± 0.08 |

1.99 ± 0.08 |

0.862 |

| Post-dialysis |

1.76 ± 0.02 |

1.77 ± 0.03 |

1.59 ± 0.02 |

2.22 ± 0.02 |

< 0.001 |

| Variation |

-0.21 ± 0.07 |

-0.22 ± 0.07 |

-0.39 ± 0.07 |

0.23 ± 0.07 |

< 0.001 |

3. Discussion

Many experts have expressed concerns about citrate's ability to bind calcium and cause hypocalcemia [

29]. However, several studies, including our own, have shown that citrate does not significantly increase the risk of symptomatic hypocalcemia [

15]. In our research, the only dialysate that reduced post-dialysis total calcium concentration was AD-Ca1.25, while the others showed no differences.

We found that ionized calcium levels were higher after dialysis when using acetate dialysates and slightly but significantly lower when using citrate dialysates. Using CD may help decrease the amount of calcium gain during dialysis treatments. Despite the decrease in ionized calcium, we did not observe a significant increase in adverse events reported with citrate compared to acetate. In fact, reductions in ionized calcium are minimal or non-existent as shown in previous publications [

10,

30] and ionic calcium levels actually increase about 30 to 60 minutes after the session ends, as calcium citrate is metabolized. This release of calcium occurs in hepatocytes, making hepatic failure an important factor in citrate accumulation and toxicity [

20,

31]. Interestingly, the use of citrate has been linked with a lower risk of vascular calcification due to the lack of calcium loading [

19,

32,

33].

We found that post-dialysis blood levels of iPTH did not significantly differ from pre-dialysis levels, except when using acetate as the dialysate buffer with a calcium concentration of 1.5 mmol/L, as noted by Argilés et al. [

34]. These results suggest that the difference observed in post-dialysis iPTH between acetate and citrate dialysates is due to an inhibitory effect driven by hypercalcemia when patients used the acetate buffer containing 1.5 mmol/L of calcium, rather than iPTH stimulation by citrate or relative hypocalcemia as reported in previous works [

35,

36].

The significance of studying different magnesium levels in the dialysate has evolved. A lower magnesium dialysis concentration was believed to have biochemical advantages by correcting hypermagnesemia and maintaining average erythrocyte potassium concentrations [

37,

38]. However, later research found that higher serum magnesium levels may be linked to a lower mortality rate [

22,

23], making the previous arguments less critical.

Hypomagnesemia has been associated with a higher risk of death in hemodialysis patients [

25]. Some researchers have suggested specific target values of 2.5 and 2.8 mg/dL, which they found to improve survival rates [

22,

23]. However, this finding has only been observed in HD patients, not in HDF, especially when acetate is used as the primary dialysis buffer. Only one study by Pérez-García et al. [

24] included some HDF patients to compare survival rates between citrate and acetate dialysates. This study identified a higher occurrence of hypomagnesemia in patients using citrate dialysate with the standard magnesium concentration of 0.5 mmol/L compared to those using acetate. The study suggested that hypomagnesemia might have been a confounding factor in their mortality outcomes, masking improved survival rates of CD versus AD. Our study found that using a magnesium dialysate concentration of 0.5 mmol/L, regardless of whether acetate or citrate were used as buffers, resulted in post-dialysis magnesium levels < 2 mg/dL. This was overcome by supplementing with 0.75 mmol/L magnesium concentration, which increased post-dialysis levels compared to pre-dialysis ones. This is an important finding as it achieves levels above the cut-off value for survival advantage established by Pérez-García et al. of 2.1 mg/dL [

24].

The ability of citrate to bind to other divalent ions has led to the hypothesis that certain metallic elements, such as iron or copper, could explain the beneficial effect of CD on inflammation or endothelial damage [

17,

26]. This study could not demonstrate this hypothesis, as the levels of these elements did not differ among dialysates.

Additionally, evidence suggests the stability of selenium and zinc in HDF patients [

39] and a link between cadmium levels and inflammation and malnutrition in dialysis patients [

40]. However, the chelating effect of citrate on these elements in the hemodialysis setting has not been fully described [

41,

42,

43,

44]. In our results, only selenium, copper, and iron were significantly removed by dialysis. On the other hand, copper and zinc levels in the blood remained unchanged compared to pre-dialysis levels. Further research is needed in this area.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, we cannot draw definite conclusions about the long-term effects of different calcium concentrations on CKD-MBD biomarkers since we only evaluated these dialysates on a few sessions. Additionally, using AD with 1.25 mmol/L of calcium is known to increase PTH levels and worsen secondary hyperparathyroidism over time. In our study, we only collected blood samples 10 minutes after dialysis and did not assess the complete kinetics of calcium and magnesium. However, it is known that citrate is metabolized entirely in bicarbonate from 30 to 60 minutes after the end of the dialysis session, releasing calcium and magnesium ions. Although it is unlikely, further assessment at the 3- and 6-month marks would be necessary to confirm the consistency of this effect on calcium chelation with AD with 1.25 mmol/L of calcium. Thirdly, this study involved a small group of patients from one center, and we only measured the total concentration of some of the divalent metals, not the ionized forms. Therefore, there may be a concentration difference that our assay was unable to detect. Finally, in our cohort, all patients were on post-dilution HDF. It's generally understood that, for a given concentration gradient between blood and dialysate, calcium balance in pre-dilution HDF will be lower than in high-flux HD, and often negative, especially with higher ultrafiltration rates [

45]. Therefore, when switching from HD or post-dilution HDF to pre-dilution HDF, an increase in dialysate calcium of approximately 0.5 mEq/L is recommended [

46]. Further studies will need to assess the calcium balance in those situations. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into the behavior and effects of citrate dialysate, which can help tailor hemodialysis treatments to better suit our patients.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Setting

This is a prospective crossover study carried out in a single center. All patients from our center’s hemodialysis morning shift were considered for inclusion. Included patients had to be on a thrice-weekly online HDF program for at least three months, have less than 250 mL of urine output, have an available well-functioning vascular access (capable of > 350 mL/min of prescribed blood flow), and provide informed consent. Patients with a scheduled living donor kidney transplant within the next month, severe (< 7.0 mg/dL) or symptomatic hypocalcemia, taking oral magnesium supplements, or with active cancer or infection were excluded. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

4.2. Dialysates

In this study, four types of dialysates were compared. Two of them were acetate-based: SmartBag® 211.5 (AD-Ca1.5) and SmartBag® 211.25 (AD-Ca1.25), with a calcium concentration of 1.5 and 1.25 mmol/L, respectively. The other two were citrate-based: SmartBag® CA 211.5 (CD-Mg0.5) and SmartBag® CA 211.5-0,75 (CD-Mg0.75), both with 1.5 mmol/L calcium concentrations but differing in 0.5 and 0.75 mmol/L magnesium concentrations, respectively. Fresenius Medical Care, Bad-Homburg, Germany, manufactures all these dialysates. Details on each dialysate's composition can be found in

Table 3.

Each patient was randomized to one of four groups where each session would be conducted with one dialysate on the mid-dialysis weekday in the following order:

- (a)

Week 1: SmartBag 211.5, week 2: SmartBag 211.25, week 3: SmartBag CA 211.5, week 4: SmartBag CA 211.5-0.75

- (b)

Week 1: SmartBag 211.25, week 2: SmartBag CA 211.5, week 3: SmartBag CA 211.5-0.75, week 4: SmartBag 211.5

- (c)

Week 1: SmartBag CA 211.5, week 2: SmartBag CA 211.5-0.75, week 3: SmartBag 211.5, week 4: SmartBag 211.25

- (d)

Week 1: SmartBag CA 211.5-0.75, week 2: SmartBag 211.5, week 3: SmartBag 211.25, week 4: SmartBag CA 211.5

4.3. Variables

Demographic and medical history were obtained from electronic health records. During each dialysis session, the following variables were recorded: dialyzer used, anticoagulant type and dose, Qb, Qd, real dialysis time, Kt, total treated volume, replacement volume, ultrafiltration, vascular access recirculation, minimal relative blood volume (obtained from the Fresenius Medical Care® Blood Volume Monitor®), and blood pressure before and after each HDF session. Also, patients were encouraged to report the appearance of any symptoms (e.g., muscle cramps, headaches, or tingling) during the hemodialysis session and were asked on the next session if they had presented any unusual symptoms at home.

Blood samples were taken before the start and 10 minutes after finishing each dialysis. The following values were analyzed: blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, albumin, ionized and total calcium, phosphorus, iPTH measured by Immulite Decentralised Procedure assay, magnesium, pH, total carbon dioxide, and bicarbonate, as well as iron, selenium, zinc, copper, cadmium pre- and post-dialysis values, along with their reduction ratios. Post-dialysis concentrations were adjusted for ultrafiltration [

29].

4.4. Statistical Analysis

A repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used to determine differences in the mean concentrations at different time points and between dialysates. Post hoc analyses with a Bonferroni adjustment were then used to determine statistically significant differences between pairs. The results are expressed as the arithmetic mean ± standard deviation, and a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS software version 23 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

5. Conclusions

While there have been concerns about citrate's ability to bind calcium and magnesium, our study, along with others, suggests that citrate dialysates could help reduce calcium buildup during dialysis and, thus, positively impact vascular calcification. We also found that differences in iPTH levels between acetate and citrate dialysates are caused by high calcium levels when patients use acetate dialysate rather than stimulation of iPTH by citrate dialysates. Furthermore, the link between magnesium levels and mortality in hemodialysis patients emphasizes the importance of adjusting magnesium concentrations in dialysates when using citrate dialysates. Current nephrology practices need to focus on personalized treatments to improve cardiovascular outcomes in dialysis patients, and citrate appears to hold promise in reducing the high residual cardiovascular risk.

Author Contributions

D.R.-E., J.J.B., and F.M. participated in the research design. D.R.-E., J.J.B, and F.M. participated in writing the first version of the manuscript. D.R.-E., J.J.B, E.C.-P., E.M.-M., M.T., and R.M.F.-A. participated in the performance of the research. G.C. and M.R.-G. contributed to diagnostic tools. D.R.-E., J.J.B, and E.C.-P. participated in data analysis. All authors contributed to and approved the final version.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínic of Barcelona (HCB/2024/0173).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon reasonable request to corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

F.M. has received expenditures on travel and hospitality and conference fees from Fresenius Medical Care. J.J.B. has received expenditures on travel and hospitality from Fresenius Medical Care. The rest of the authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Sarnak, M.J.; Amann, K.; Bangalore, S.; Cavalcante, J.L.; Charytan, D.M.; Craig, J.C.; Gill, J.S.; Hlatky, M.A.; Jardine, A.G.; Landmesser, U.; et al. Chronic Kidney Disease and Coronary Artery Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019, 74, 1823–1838. [CrossRef]

- Blankestijn, P.J.; Bots, M.L. Effect of Hemodiafiltration or Hemodialysis on Mortality in Kidney Failure. Reply. N Engl J Med 2023, 389, e42. [CrossRef]

- Maduell, F.; Moreso, F.; Pons, M.; Ramos, R.; Mora-Macià, J.; Carreras, J.; Soler, J.; Torres, F.; Campistol, J.M.; Martinez-Castelao, A. High-Efficiency Postdilution Online Hemodiafiltration Reduces All-Cause Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013, 24, 487–497. [CrossRef]

- Daimon, S.; Dan, K.; Kawano, M. Comparison of Acetate-Free Citrate Hemodialysis and Bicarbonate Hemodialysis Regarding the Effect of Intra-Dialysis Hypotension and Post-Dialysis Malaise. Ther Apher Dial 2011, 15, 460–465. [CrossRef]

- Pizzarelli, F.; Cerrai, T.; Dattolo, P.; Ferro, G. On-Line Haemodiafiltration with and without Acetate. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006, 21, 1648–1651. [CrossRef]

- Kuragano, T.; Kida, A.; Furuta, M.; Yahiro, M.; Kitamura, R.; Otaki, Y.; Nonoguchi, H.; Matsumoto, A.; Nakanishi, T. Effects of Acetate-Free Citrate-Containing Dialysate on Metabolic Acidosis, Anemia, and Malnutrition in Hemodialysis Patients. Artif Organs 2012, 36, 282–290. [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, M.; Macconi, D.; Fernández, N.G.; Ghilardi, M.; Anabaya, A.; Binda, E.; Morigi, M.; Cattaneo, D.; Perticucci, E.; Remuzzi, G.; et al. Effect of Acetate-Free Biofiltration and Bicarbonate Hemodialysis on Neutrophil Activation. Am J Kidney Dis 2002, 40, 783–793. [CrossRef]

- Vida, C.; Carracedo, J.; de Sequera, P.; Bodega, G.; Pérez, R.; Alique, M.; Ramírez, R. Increasing the Magnesium Concentration in Various Dialysate Solutions Differentially Modulates Oxidative Stress in a Human Monocyte Cell Line. Antioxidants 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Noris, M.; Todeschini, M.; Casiraghi, F.; Roccatello, D.; Martina, G.; Minetti, L.; Imberti, B.; Gaspari, F.; Atti, M.; Remuzzi, G. Effect of Acetate, Bicarbonate Dialysis, and Acetate-Free Biofiltration on Nitric Oxide Synthesis: Implications for Dialysis Hypotension. Am J Kidney Dis 1998, 32, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Broseta, J.J.; López-Romero, L.C.; Cerveró, A.; Devesa-Such, R.; Soldevila, A.; Bea-Granell, S.; Sánchez-Pérez, P.; Hernández-Jaras, J. Improvements in Inflammation and Calcium Balance of Citrate versus Acetate as Dialysate Buffer in Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Unicentric, Cross-Over, Prospective Study. Blood Purif 2021, 50, 914–920. [CrossRef]

- Azpiazu, D.; González-Parra, E.; Ortiz, A.; Egido, J.; Villa-Bellosta, R. Impact of Post-Dialysis Calcium Level on Ex Vivo Rat Aortic Wall Calcification. PLoS One 2017, 12. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, R.; Ramírez Chamond, R.; de Sequera Ortiz, P.; Albalate, M.; Puerta Carretero, M.; Ortega, M.; Ruiz Caro, M.C.; Alcazar Arroyo, R. Citrate Dialysate Does Not Induce Oxidative Stress or Inflammation in Vitro as Compared to Acetate Dialysate. Nefrologia 2017, 37, 630–637. [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.W.; Kim, D.R.; Cho, K.S.; Seo, J.W.; Moon, H.; Park, E.J.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, T.W.; Ihm, C.G.; Jeong, D.W.; et al. Effects of Dialysate Acidification With Citrate Versus Acetate on Cell Damage, Uremic Toxin Levels, and Inflammation in Patients Receiving Maintenance Hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2019, 73, 432–434. [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama, K.; Tomo, T.; Kadota, J.I. Acetate-Free Blood Purification Can Impact Improved Nutritional Status in Hemodialysis Patients. J Artif Organs 2011, 14, 112–119. [CrossRef]

- Quinaux, T.; Pongas, M.; Guissard, É.; Ait-Djafer, Z.; Camoin-Schweitzer, M.C.; Ranchin, B.; Vrillon, I. Comparison between Citrate and Acetate Dialysate in Chronic Online Hemodiafiltration: A Short-Term Prospective Study in Pediatric Settings. Nephrol Ther 2020, 16, 158–163. [CrossRef]

- Molina Nuñez, M.; De Alarcón, R.; Roca, S.; Álvarez, G.; Ros, M.S.; Jimeno, C.; Bucalo, L.; Villegas, I.; García, M.Á. Citrate versus Acetate-Based Dialysate in on-Line Haemodiafiltration. A Prospective Cross-over Study. Blood Purif 2015, 39, 181–187. [CrossRef]

- Grundström, G.; Christensson, A.; Alquist, M.; Nilsson, L.G.; Segelmark, M. Replacement of Acetate with Citrate in Dialysis Fluid: A Randomized Clinical Trial of Short Term Safety and Fluid Biocompatibility. BMC Nephrol 2013, 14, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.C.W.; Tai, D.J.; Ravani, P.; Quinn, R.R.; Scott-Douglas, N.; MacRae, J.M. Citrate vs. Acetate Dialysate on Intradialytic Heparin Dose: A Double Blind Randomized Crossover Study. Hemodial Int 2016, 20, 537–547. [CrossRef]

- Villa-Bellosta, R.; Hernández-Martínez, E.; Mérida-Herrero, E.; González-Parra, E. Impact of Acetate- or Citrate-Acidified Bicarbonate Dialysate on Ex Vivo Aorta Wall Calcification. Sci Rep 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Petitclerc, T.; Diab, R.; Le Roy, F.; Mercadal, L.; Hmida, J. [Acetate-Free Hemodialysis: What Does It Mean?]. Nephrol Ther 2011, 7, 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Barmore W, Bajwa T, Burns B. Biochemistry, Clotting Factors. [Updated 2023 Feb 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507850/.

- Ishimura, E.; Okuno, S.; Yamakawa, T.; Inaba, M.; Nishizawa, Y. Serum Magnesium Concentration Is a Significant Predictor of Mortality in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. Magnes Res 2007, 20, 237–244. [CrossRef]

- Shimohata, H.; Yamashita, M.; Ohgi, K.; Tsujimoto, R.; Maruyama, H.; Takayasu, M.; Hirayama, K.; Kobayashi, M. The Relationship between Serum Magnesium Levels and Mortality in Non-Diabetic Hemodialysis Patients: A 10-Year Follow-up Study. Hemodialysis International 2019, 23, 369–374. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, R.; Jaldo, M.T.; Puerta, M.; Ortega, M.; Corchete, E.; de Sequera, P.; Martin-Navarro, J.A.; Albalate, M.; Alcázar, R. Hypomagnesemia in Hemodialysis Is Associated with Increased Mortality Risk: Its Relationship with Dialysis Fluid. Nefrología 2020, 40, 552–562. [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, Y.; Fujii, N.; Shoji, T.; Hayashi, T.; Rakugi, H.; Isaka, Y. Hypomagnesemia Is a Significant Predictor of Cardiovascular and Non-Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Kidney Int 2014, 85, 174–181. [CrossRef]

- Dellepiane, S.; Medica, D.; Guarena, C.; Musso, T.; Quercia, A.D.; Leonardi, G.; Marengo, M.; Migliori, M.; Panichi, V.; Biancone, L.; et al. Citrate Anion Improves Chronic Dialysis Efficacy, Reduces Systemic Inflammation and Prevents Chemerin-Mediated Microvascular Injury. Sci Rep 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Urena-Torres, P.; Bieber, B.; Guebre-Egziabher, F.; Ossman, R.; Jadoul, M.; Inaba, M.; Robinson, B.M.; Port, F.; Jacquelinet, C.; Combe, C. Citric Acid-Containing Dialysate and Survival Rate in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney360 2021, 2, 666–673. [CrossRef]

- Bergström, J.; Wehle, B. No Change in Corrected Β2-Microglobulin Concentration after Cuprophane Haemodialysis. The Lancet 1987, 14, 628–629. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Sternby, J.; Gundstrom, G.; Alquist Hegbrant, M. Citrate Dialysis Fluid and Calcium Mass Balance (Abstract). Neph Dial Transplantation 2013, 28, Issue suppl_1.

- Panichi, V.; Fiaccadori, E.; Rosati, A.; Fanelli, R.; Bernabini, G.; Scatena, A.; Pizzarelli, F. Post-Dilution on Line Haemodiafiltration with Citrate Dialysate: First Clinical Experience in Chronic Dialysis Patients. ScientificWorldJournal 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Dao, M.; Touam, M.; Joly, D.; Mercadal, L. [Acetate-Free Bicarbonate Dialysate: Which Acid in the Dialysis Buffer?]. Nephrol Ther 2019, 15 Suppl 1, S91–S97. [CrossRef]

- Steckiph D, Bertucci A, Petraulo M, Baldini C, Calabrese G, Gonella M. Calcium mass balances in on-line hemodiafiltration using citrate-containing acetate-free and regular dialysis concentrates. Neph Dial Transplantation 2013, 28, Issue suppl_1.

- Pérez-García, R.; Albalate, M.; Sequera, P.; Ortega, M. El Balance de Calcio Es Menor Con Un Líquido de Diálisis Con Citrato Que Con Acetato. Nefrología 2017, 37, 109–110. [CrossRef]

- Argilés, A.; Mion, C.M. Calcium Balance and Intact PTH Variations during Haemodiafiltration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1995, 10, 2083–2089.

- Ficociello LH, Zhou M, Mullon C, Anger MS, Kossmann RJ. Effect of Citrate-Acidified Dialysate on Intact Parathyroid Hormone in Prevalent Hemodialysis Patients: A Matched Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kuragano, T.; Furuta, M.; Yahiro, M.; Kida, A.; Otaki, Y.; Hasuike, Y.; Matsumoto, A.; Nakanishi, T. Acetate Free Citrate-Containing Dialysate Increase Intact-PTH and BAP Levels in the Patients with Low Intact-PTH. BMC Nephrol 2013, 14. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, W.K.; Fleming, L.W. The Effect of Dialysate Magnesium on Plasma and Erythrocyte Magnesium and Potassium Concentrations during Maintenance Haemodialysis. Nephron 1973, 10, 222–231. [CrossRef]

- Gonella, M.; Bonaguidi, F.; Buzzigoli, G.; Bartolini, V.; Mariani, G. On the Effect of Magnesium on the PTH Secretion in Uremic Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis. Nephron 1981, 27, 40–42. [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.; Davenport, A. Does Online Hemodiafiltration Lead to Reduction in Trace Elements and Vitamins? Hemodial Int 2011, 15, 509–514. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.W.; Lin, J.L.; Lin-Tan, D.T.; Yen, T.H.; Huang, W.H.; Ho, T.C.; Huang, Y.L.; Yeh, L.M.; Huang, L.M. Association of Environmental Cadmium Exposure with Inflammation and Malnutrition in Maintenance Haemodialysis Patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009, 24, 1282–1288. [CrossRef]

- Kefalas, E.T.; Dakanali, M.; Panagiotidis, P.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Terzis, A.; Mavromoustakos, T.; Kyrikou, I.; Karligiano, N.; Bino, A.; Salifoglou, A. PH-Specific Aqueous Synthetic Chemistry in the Binary Cadmium(II)-Citrate System. Gaining Insight into Cadmium(II)-Citrate Speciation with Relevance to Cadmium Toxicity. Inorg Chem 2005, 44, 4818–4828. [CrossRef]

- Rode, S.; Henninot, C.; Vallières, C.; Matlosz, M. Complexation Chemistry in Copper Plating from Citrate Baths. J Electrochem Soc 2004, 151, C405. [CrossRef]

- Mattar, G.; Haddarah, A.; Haddad, J.; Pujola, M.; Sepulcre, F. Are Citric Acid-Iron II Complexes True Chelates or Just Physical Mixtures and How to Prove This? Foods 2023, 12, 410. [CrossRef]

- Bai, K.; Hong, B.; Hong, Z.; Sun, J.; Wang, C. Selenium Nanoparticles-Loaded Chitosan/Citrate Complex and Its Protection against Oxidative Stress in d-Galactose-Induced Aging Mice. J Nanobiotechnology 2017, 15, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, C.W. Calcium Balance during Hemodialysis. Semin Dial 2008, 21, 38–42. [CrossRef]

- Malberti, F.; Ravani, P. The Choice of the Dialysate Calcium Concentration in the Management of Patients on Haemodialysis and Haemodiafiltration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003, 18 Suppl 7. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).