Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Section 1. Phosphorus in Plant Nutrition

- Phosphorus is an essential plant nutrient required for energy transfers, photosynthesis, and cell division

- Plants have developed genetic strategies to access and efficiently utilize P

- Metabolically active P is a small proportion of the total plant P if P is not deficient

- Plant breeding may be able to improve phosphorus use efficiency by developing plants that are better able to access and utilize P

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Accumulation of P by the Plant

1.3. Phosphorus Deficiency Symptoms

1.4. Summary

Section 2. Phosphorus Use Efficiency

- Phosphorus use efficiency (PUE) can be measured through different methods that consider the short- and long-term use of P in the cropping system

- Selection of the most appropriate method of assessing phosphorus use efficiency depends on the goal

- Short-term assessments of PUE may miss legacy benefits from P applications

- Factors other than P supply that limit yield potential will decrease PUE

- Assessment of both fertility and physiologically based PUE can be important tools that plant breeders can use to improve the PUE of new cultivars

2.1. What is Phosphorus Use Efficiency?

2.2. Fertility Based Measurements of Phosphorus Use Efficiency

2.3. Physiologically Based Measurement of Phosphorus Use Efficiency

2.4. Interpretation of Phosphorus Use Efficiency

2.5. Summary

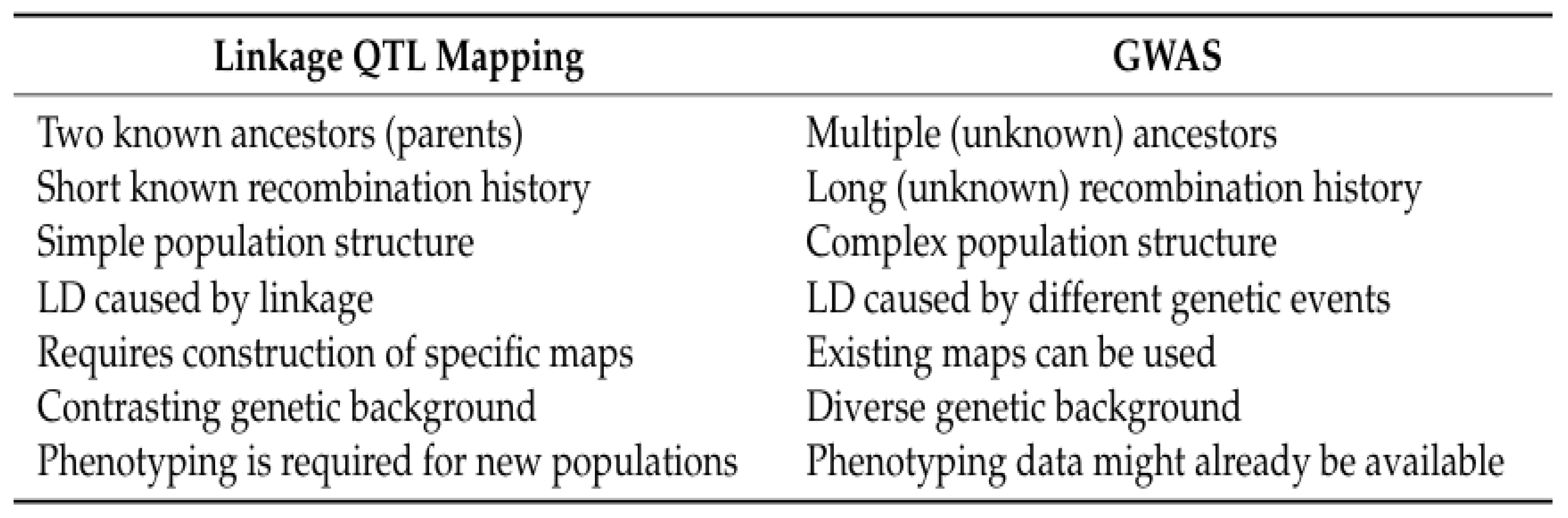

Section 3. Description of Genetic Techniques in Plant Breeding

- Plant breeding has improved crop yield, agronomic characteristics, disease resistance and nutritional quality

- Traditional plant breeding selected for superior physical characteristics that were present in the natural population

- The ability to rapidly assess the genetic composition of plants, to quickly measure physical traits and to analyse large amounts of data has improved the ability to breed for complex characteristics

- New molecular techniques can generate genetic diversity by moving genes between unrelated species or by precisely editing genes.

- Molecular techniques can allow the breeder to make selections early in the breeding process at the molecular, cellular, or tissue level

- Modern breeding techniques can shorten the time and reduce the costs for developing improved cultivars and breed for characteristics that are not normally found in the population

3.1. Introduction

3.2. Traditional Plant Breeding

3.2.1. Traditional Breeding in Self-Pollinated Crops

3.2.2. Traditional Breeding in Cross-Pollinated Crops

3.3. Molecular Plant Breeding Techniques

3.3.1. Marker Assisted Selection

|

3.3.2. Genomic Selection

3.3.3. Doubled Haploids

3.3.4. Plant Tissue Culture

3.3.5. Speed Breeding

3.4. Development of Variability in the Breeding Population

3.5. Analytical Techniques

3.6. Summary

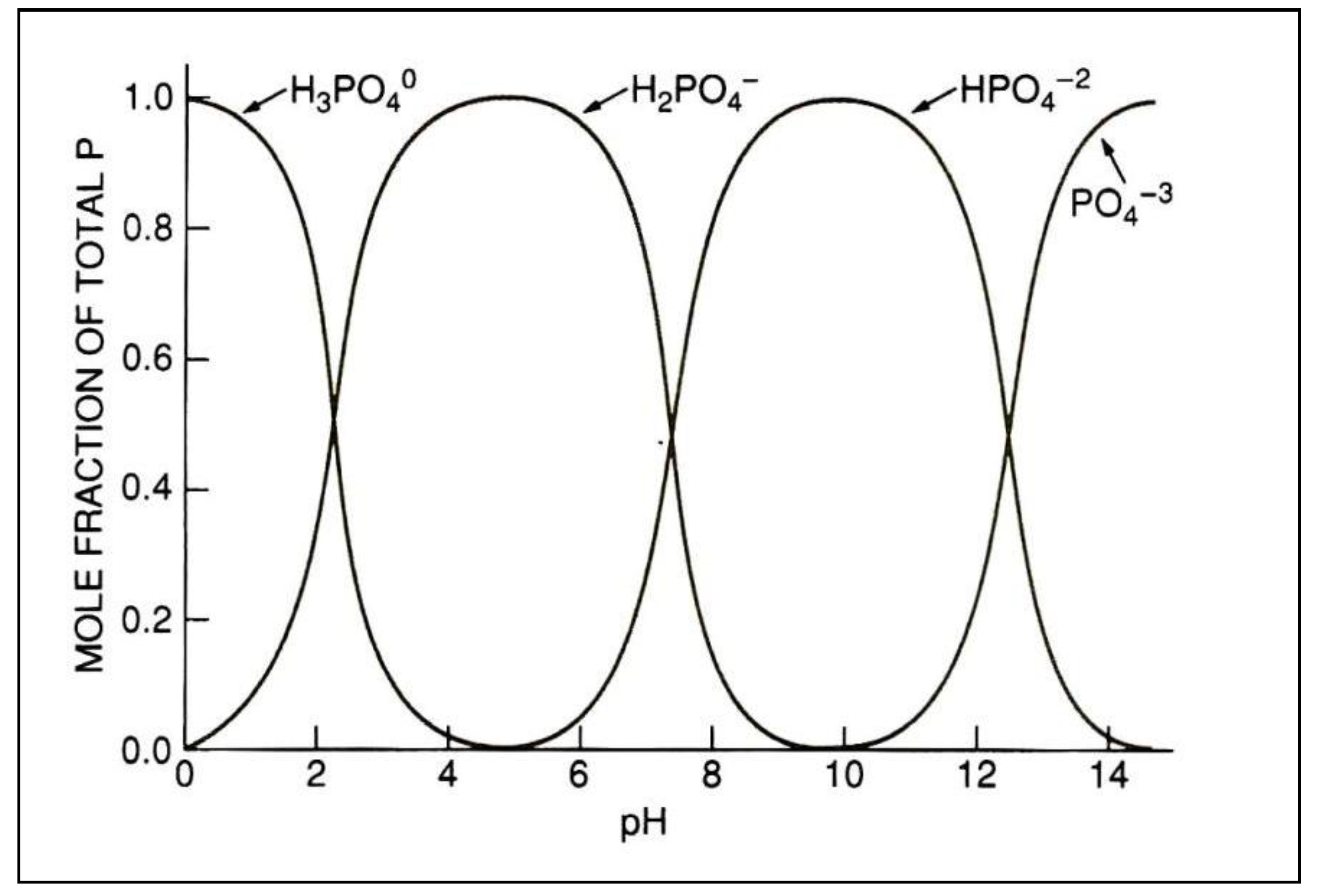

Section 4. Phosphorus Reactions in the Soil that Affect Phosphorus Availability

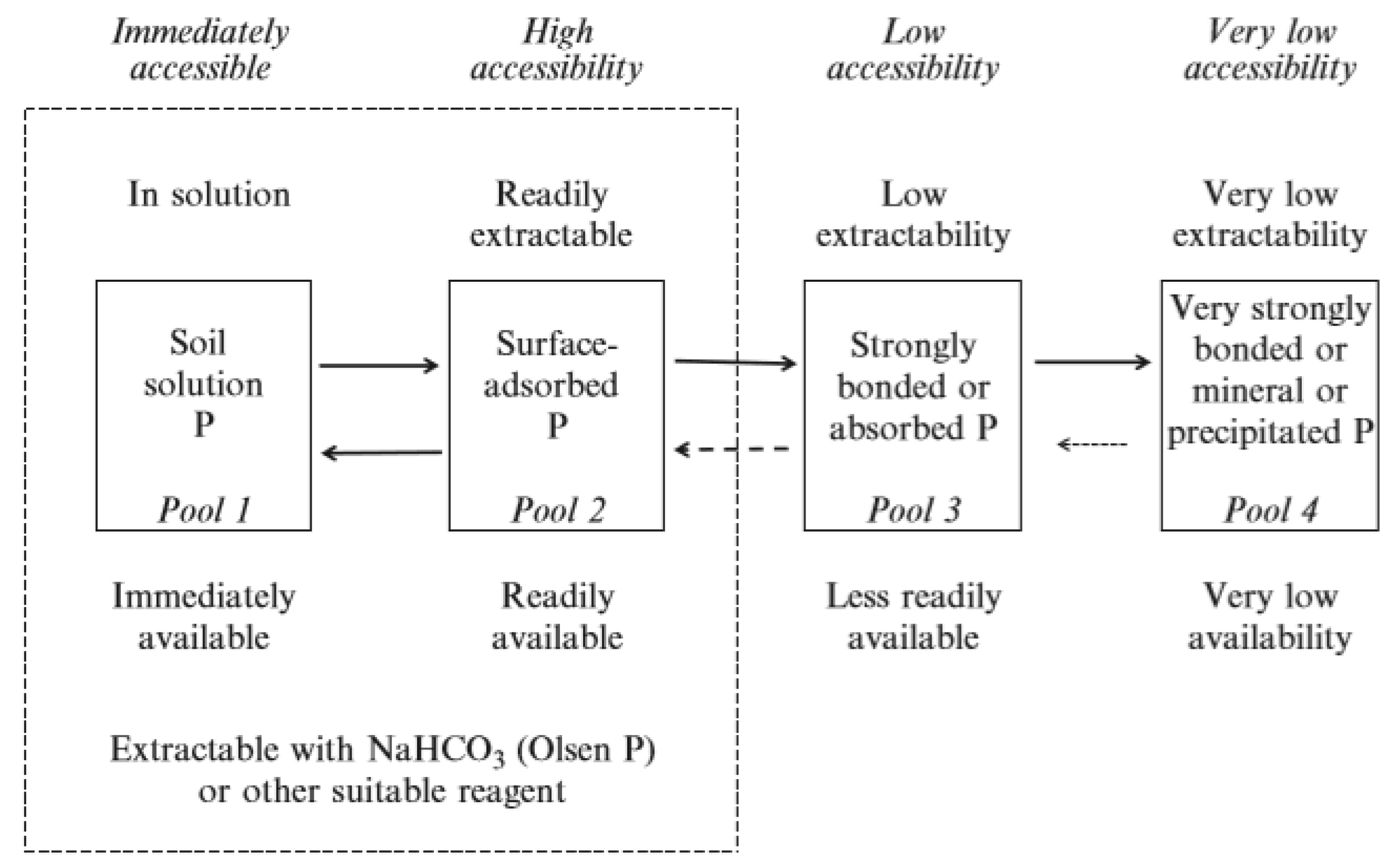

- Plants take up P from the soil solution as the inorganic orthophosphate ion (Pi)

- Phosphorus concentration in the soil solution is very low and must be replenished from other soil pools to meet plant demand

- Supply of Pi to the plant roots will be affected by the concentration of Pi at the root surface and the speed that the concentration can be replenished

- Water-soluble P fertilizer will undergo a series of adsorption and precipitation reactions that move it from solution into less soluble labile and non-labile pools of P in the soil. These reactions are reversible and respond to the concentration gradient

- Plants respond to P deficiency with strategies to increase Pi in the soil solution, the root area available for P uptake and the ability to take up and move P into and throughout the plant

- Plant breeding can select for genetic traits such as root growth and root exudation that address restrictions in soil Pi to improve phosphorus use efficiency

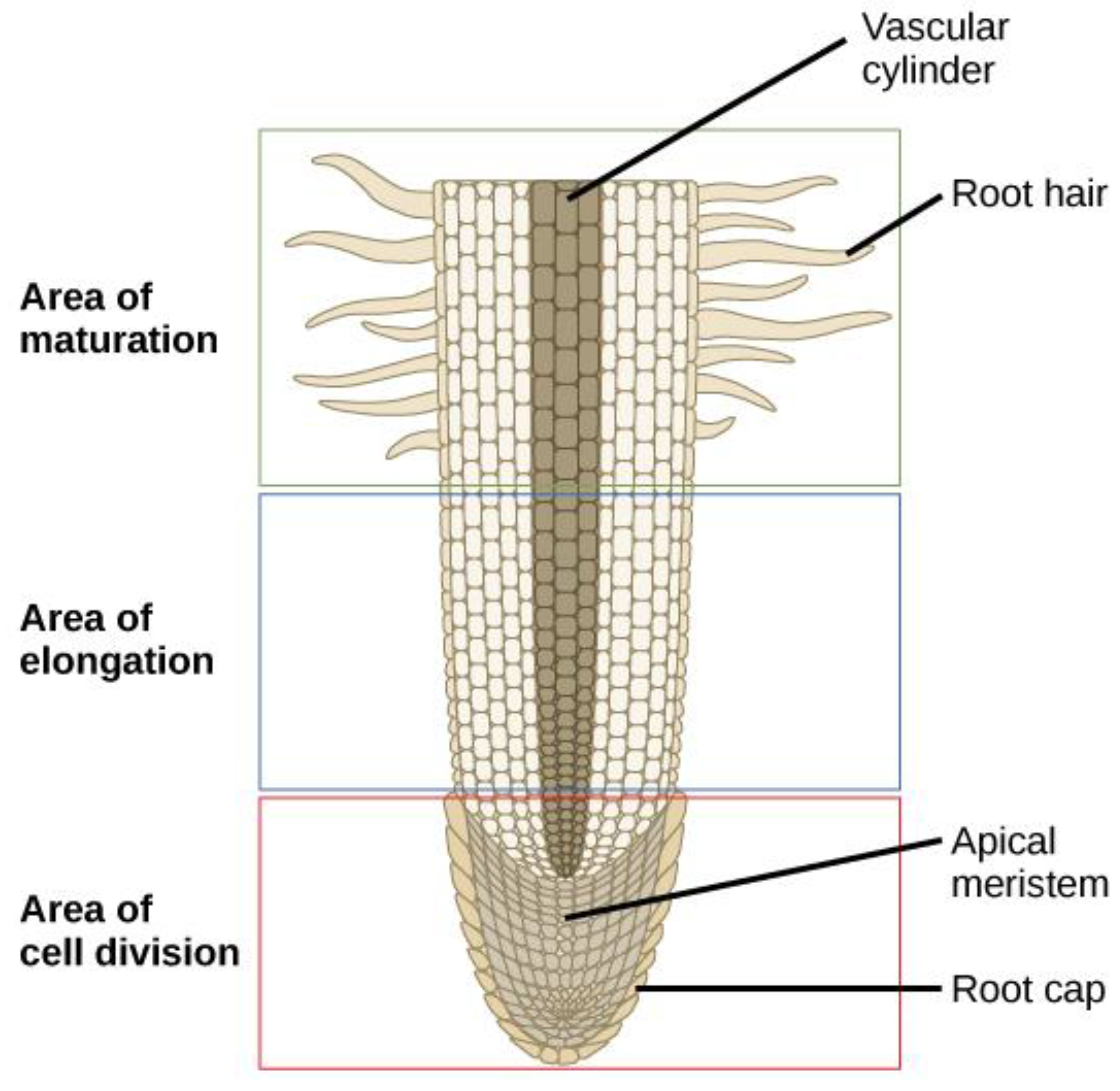

4.1. Uptake of P from the Soil Solution

4.2. Reactions of P in the Soil

4.3. Plant-Soil Interactions

- 1.

- Increasing root production and altering root architecture to increase the volume of soil explored and the root surface area available for P uptake.

- 2.

- Excretion of various organic acids and enzymes that can increase the amount of Pi that moves into the soil solution.

- 3.

- Increased activity of transporter proteins to more efficiently take up P from the soil solution, depleting the soil solution concentration of Pi and encouraging more movement of Pi into the soil solution and towards the root surface.

- 4.

- Enhanced mycorrhizal associations to further increase soil exploration for P in certain plant species.

4.4. Summary

Section 5. Phosphorus Accumulation and Utilization in Crops

- Plants require P for cell growth from the earliest stages of germination

- After seed reserves of P are depleted, plants rely on inorganic P from the soil solution to support growth

- Uptake of P from the soil solution is a function of the absorbing area of the root and the concentration of Pi in the soil solution at the root surface

- Root growth and architecture respond to P availability and are under genetic control

- Most plant species form mycorrhizal associations to improve access to soil P

- Plants secrete low molecular weight amino acids that increase P solubility and mobility, thus increasing its availability

- Uptake of Pi from the soil solution and its distribution throughout the plant is facilitated by transporter proteins whose production and function are affected by plant genetics

- Surplus Pi is stored in the vacuole and can be mobilized to maintain cytoplasmic Pi concentration when Pi supply is low

- The ability of the plant to mobilize and adjust the distribution of P among the various P forms present in the plant to maintain homeostasis is under genetic control and may be a target for breeding

- Reduction of phytate concentration in seeds could reduce P concentration in manure and sewage, improving both environmental sustainability and phosphorus use efficiency

5.1. Introduction

5.2. Root Exploration of the Soil

5.3. Transport of P into the root

5.4. Movement of P from the Root Throughout the Plant

5.5. Phosphorus Utilization in the Plant

5.6. Summary

Section 6. Genetic Improvement of Phosphorus Access From the Soil

- Plants have developed strategies to improve their ability to access P from the soil

- Genetic modification of the size and shape of the root system may increase the ability of the plant to access and absorb P from the soil solution

- Genetic modification of the ability of a plant to form a mycorrhizal association is possible, but may not provide a consistent enough benefit to warrant inclusion in a breeding program

- Plant root exudates may mobilize P into the soil solution and influence mycorrhizal colonization and/or rhizosphere; however, effects may not be persistent enough to justify breeding to modify exudation

6.1. Introduction

6.2. Breeding for an Improved Root System

6.3. Breeding for Enhanced Mycorrhizal Association

6.4. Rhizosphere Modification

6.5. Summary

Section 7. Genetic Improvement of Root Uptake of Phosphorus

- P must move from the soil solution into the plant against a concentration gradient using transporters that actively move Pi across the cell membrane

- Cross-membrane transport is also needed to move P within the plant inside cells, between cells, and between plant organs and organelles to support cellular functions and plant growth

- The genetic regulation of the P transporters involves response at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels

- A broader understanding of how genetic factors controlling P transport systems interact in representative environments is needed to be able to effectively manipulate their performance through plant breeding to improve phosphorus use efficiency

7.1. Introduction

7.2. Regulation of Phosphorus Uptake and Distribution

7.3. Genetic Manipulation of Transporter Systems

7.4. Summary

Section 8. Improvements in Physiological Efficiency of Phosphorus Use

- Plant strategies to improve physiological phosphorus use efficiency are under genetic control

- Most P in a well-nourished plant is stored in the vacuole, and remobilization of inorganic P (Pi) from the vacuole can mitigate short-term Pi deprivation and prevent Pi starvation

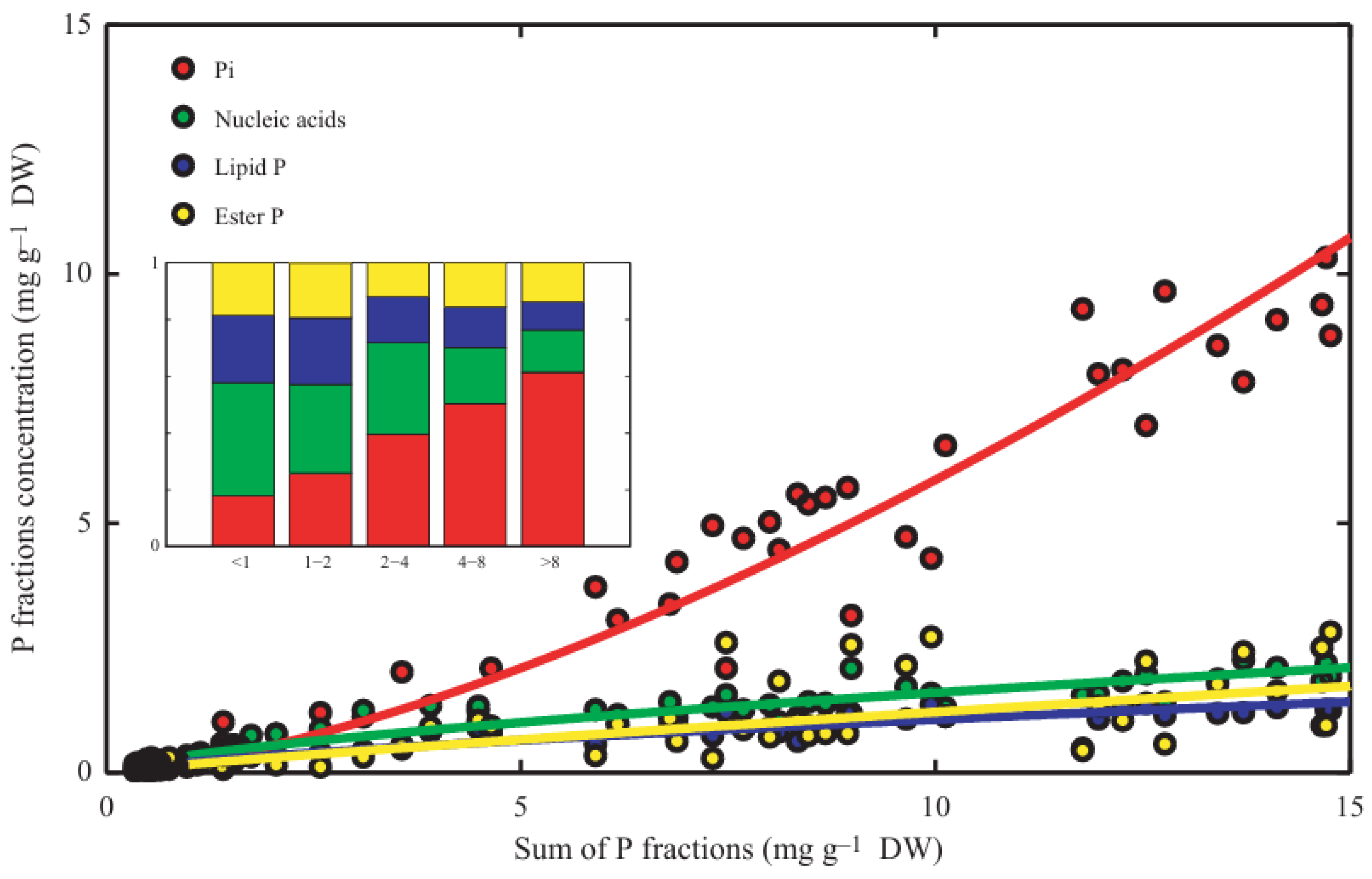

- Organic P in the plant is present as nucleic acids (mainly RNA) > phospholipids > P-esters > DNA > phosphorylated proteins

- Plants sense P supply locally at the root tip or systemically by the concentration of substances, such as inositol pyrophosphates and microRNA 399

- Some plants can replace the P-containing phospholipids with lipids that do not contain P to free up Pi for other metabolic uses

- Substituting enzymes that use inorganic pyrophosphate rather than ATP and Pi to catalyze critical reactions or by-passing Pi- or ATP-demanding enzymes and/or metabolic pathways could conserve Pi when it is limiting

- Pi can be mobilized and recycled from older to younger vegetative tissues to support growth and improved photosynthetic capacity

- RNA is a large reserve of Pi that can potentially be remobilized.

- Reducing phytate concentration in the seed can reduce P removal from the system and potentially reduce P moving into waste streams

- A greater understanding of physiological regulation and interactions of P in the plant and of genetic by environment interactions under field conditions is needed

8.1. Introduction

8.2. Sensing of P Status

8.3. Mobilization from the Vacuole

8.4. Modification of Phospholipids

8.5. Energy Reactions

8.6. Recycling of P

8.7. Regulation in Other Organelles

8.8. Phytate Level in the Seed

8.9. Use of Phosphite

8.10. Summary

Section 9. Fitting Genetic Technology into a Sustainable Phosphorus Management System

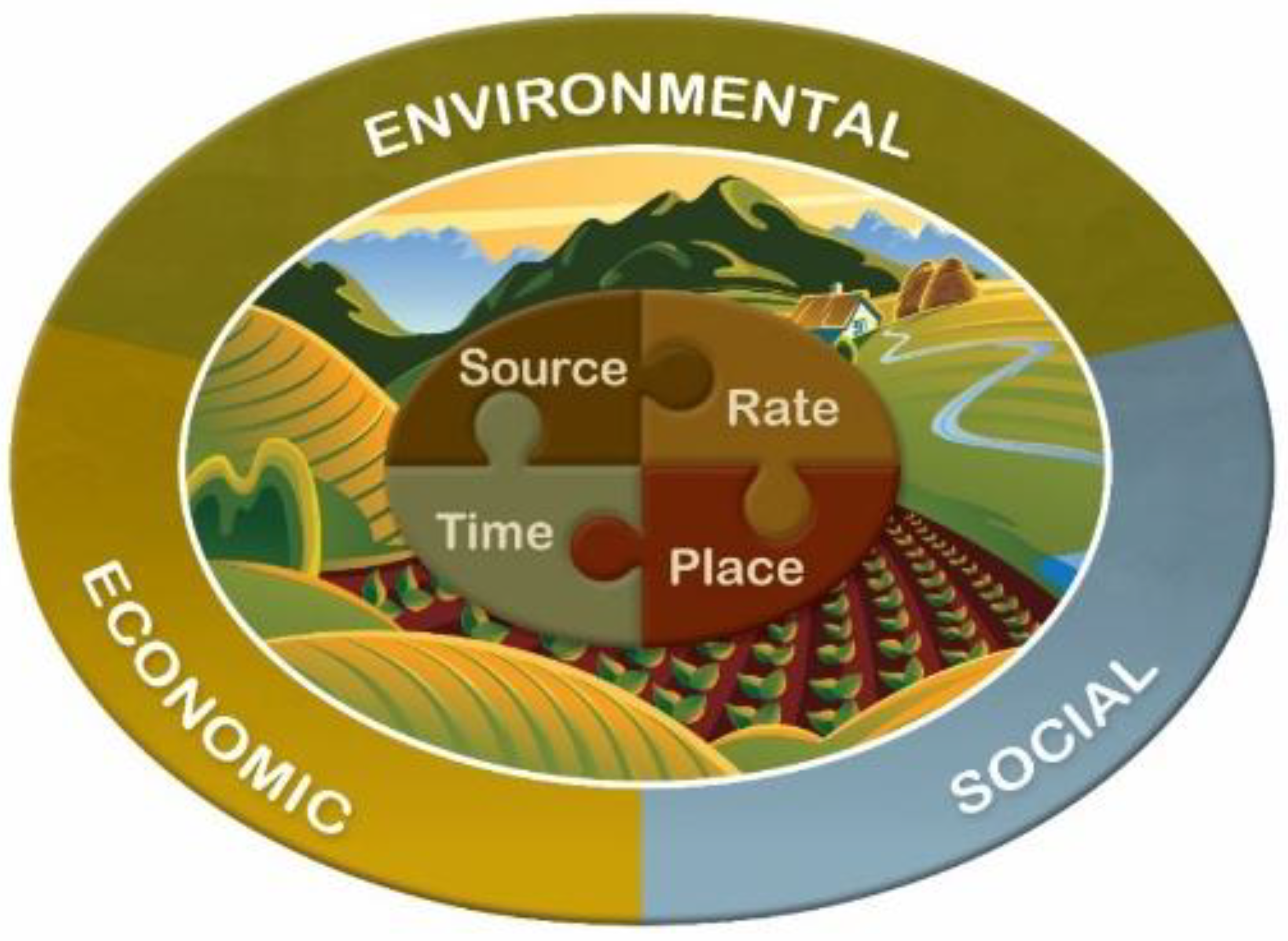

- The 4Rs of source, rate, time and place interact with one another, with other agronomic management practices, and with economic, environmental and social goals

- Phosphorus supply should be balanced with phosphorus removal over the long term to avoid excess depletion or accumulation

- Matching root system architecture with P distribution in the soil and fertilizer management systems may improve system efficiency

- Reduction in phytic acid concentration in the seed could reduce P removal and the risk of damage from excess P in manures and wastes

9.1. Sustainable Phosphorus Management

9.2. Role of Plant Genetics in Sustainable P Management

9.2. Summary

Section 10. Summary and Need for Future Work

- Modern breeding techniques can shorten the time and reduce the costs for developing improved cultivars, and allow breeders to select for characteristics that are not normally found in the population

- Root growth and architecture are key targets for breeding to improve PUE

- Uptake of P from the soil solution and its distribution across cell membranes throughout the plant against a concentration gradient is facilitated by transporter proteins whose production and function may be improved through plant breeding

- The ability of the plant to mobilize and adjust the distribution of P among the various P forms present in the plant to maintain homeostasis is under genetic control and may be a target for breeding

- Reduction of phytate concentration in seeds could reduce P removal from the field and decrease P concentration in manure and sewage, improving both environmental sustainability and phosphorus use efficiency

- Mycorrhizal associations and plant root exudates could be modified by plant breeding; however, benefits may not be consistent enough to justify inclusion in a breeding program

- A broader understanding of how genetic factors controlling PUE interact in representative environments is needed to be able to effectively manipulate their performance through plant breeding

10.1. Summary

References

- Abel S (2017) Phosphate scouting by root tips. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 39:168-177. [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye B, Akinremi OO, Hu Y, Flaten DN (2007) Phosphorus speciation of sequential extracts of organic amendments using nuclear magnetic resonance and x-ray absorption near-edge structure spectroscopies. J Environ Qual 36 (6):1563-1576. [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye B, Akinremi OO, Hu Y, Jürgensen A (2008) XANES speciation of phosphorus in organically amended and fertilized Vertisol and Mollisol. Soil Sci Soc Am J 72 (5):1256-1262. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar S, Rao E, Uike A, Saatu M (2023) Plant Breeding Strategies: Traditional and Modern Approaches. In: Genetic Revolution in Agriculture: Unleashing the Power of Plant Genetics vol 1. Elite Publishing House, Delhi, pp 21-43.

- Amiteye S (2021) Basic concepts and methodologies of DNA marker systems in plant molecular breeding. Heliyon 7 (10):e08093. [CrossRef]

- Anghinoni Ia, Barber S (1980) Phosphorus influx and growth characteristics of corn roots as influenced by phosphorus supply. Agron J 72 (4):685-688.

- Argaye S (2021) Development and the Role of Tissue Culture in Plant Breeding: A review. International Journal of Research Studies in Agricultural Sciences.

- Ashworth J, Mrazek K (1995) “Modified Kelowna” test for available phosphorus and potassium in soil. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 26 (5-6):731-739. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson JA, Pound MP, Bennett MJ, Wells DM (2019) Uncovering the hidden half of plants using new advances in root phenotyping. Curr Opin Biotech 55:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson JA, Wingen LU, Griffiths M, Pound MP, Gaju O, Foulkes MJ, Le Gouis J, Griffiths S, Bennett MJ, King J, Wells DM (2015) Phenotyping pipeline reveals major seedling root growth QTL in hexaploid wheat. J Exp Bot 66 (8):2283-2292. [CrossRef]

- Bagshaw R, Vaidyanathan LV, Nye PH (1972) The supply of nutrient ions by diffusion to plant roots in soil - V. Direct determination of labile phosphate concentration gradients in a sandy soil induced by plant uptake. Plant Soil 37 (3):617-626.

- Barber S (1995) Soil Nutrient Availability. A Mechanistic Approach. 2nd edn. Wiley, New York.

- Barber SA (1977) Application of phosphate fertilizers: Methods, rates and time of application in relation to the phosphorus status of soils. Phosphorus Agric 70:109-115.

- Barber SA (1980) Soil-plant interactions in the phosphorus nutrition of plants. In: Khasawneh FE, Sample EC, Kamprath EJ (eds) The Role of Phosphorus in Agriculture. ASA, CSSA, and SSSA Books. ASA, CSSA, and SSSA Madison, WI, pp 591-615. [CrossRef]

- Barber SA, Walker JM, Vasey EH (1963) Mechanisms for the movement of plant nutrients from the soil and fertilizer to the plant root. J Agric Food Chem 11 (3):204-207.

- Bayuelo-Jiménez JS, Ochoa-Cadavid I (2014) Phosphorus acquisition and internal utilization efficiency among maize landraces from the central Mexican highlands. Field Crop Res 156:123-134. [CrossRef]

- Bernardino KC, Pastina MM, Menezes CB, de Sousa SM, Maciel LS, Jr GC, Guimarães CT, Barros BA, da Costa e Silva L, Carneiro PCS, Schaffert RE, Kochian LV, Magalhaes JV (2019) The genetic architecture of phosphorus efficiency in sorghum involves pleiotropic QTL for root morphology and grain yield under low phosphorus availability in the soil. BMC Plant Biol 19 (1):87. [CrossRef]

- Bertrand I, McLaughlin MJ, Holloway RE, Armstrong RD, McBeath T (2006) Changes in P bioavailability induced by the application of liquid and powder sources of P, N and Zn fertilizers in alkaline soils. Nutr Cycling Agroecosyst 74 (1):27-40.

- Bolan NS (1991) Critical review on the role of mycorrhizal fungi in the uptake of phosphorus by plants. Plant Soil 141:1-11.

- Borkert C, Barber S (1983) Effect of supplying P to a portion of the soybean root system on root growth and P uptake kinetics. J Plant Nutr 6 (10):895-910.

- Bovill W, Huang C-Y, McDonald G (2013) Genetic approaches to enhancing phosphorus-use efficiency (PUE) in crops: Challenges and directions. Crop Pasture Sci 64:179. [CrossRef]

- Brenchley WE (1929) The phosphate requirement of barley at different periods of growth. Ann Bot 43:89-112.

- Carkner MK, Gao X, Entz MH (2023) Ideotype breeding for crop adaptation to low phosphorus availability on extensive organic farms. Front Plant Sci 14:1225174. [CrossRef]

- Chang MX, Gu M, Xia YW, Dai XL, Dai CR, Zhang J, Wang SC, Qu HY, Yamaji N, Feng Ma J, Xu GH (2019) OsPHT1;3 mediates uptake, translocation, and remobilization of phosphate under extremely low phosphate regimes. Plant Physiol 179 (2):656-670. [CrossRef]

- Chen A, Liu T, Wang Z, Chen X (2022) Plant root suberin: A layer of defence against biotic and abiotic stresses. Front Plant Sci 13:1056008. [CrossRef]

- Chmielewska B, Janiak A, Karcz J, Guzy-Wrobelska J, Forster BP, Nawrot M, Rusek A, Smyda P, Kedziorski P, Maluszynski M, Szarejko I (2014) Morphological, genetic and molecular characteristics of barley root hair mutants. J Appl Genet 55 (4):433-447. [CrossRef]

- Close DC, Beadle CL (2003) The ecophysiology of foliar anthocyanin. The Botanical Review 69 (2):149-161.

- Colasuonno P, Marcotuli I, Gadaleta A, Soriano JM (2021) From genetic maps to QTL cloning: an overview for durum wheat. Plants (Basel) 10 (2). [CrossRef]

- Dakora FD, Phillips DA (2002) Root exudates as mediators of mineral acquisition in low-nutrient environments. Plant Soil 245 (1):35-47. [CrossRef]

- Davies JP, Kumar S, Sastry-Dent L (2017) Chapter Three - Use of Zinc-Finger Nucleases for Crop Improvement. In: Weeks DP, Yang B (eds) Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, vol 149. Academic Press, pp 47-63. [CrossRef]

- De Vita P, Avio L, Sbrana C, Laidò G, Marone D, Mastrangelo AM, Cattivelli L, Giovannetti M (2018) Genetic markers associated to arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization in durum wheat. Scientific Reports 8 (1):10612. [CrossRef]

- Deja-Muylle A, Parizot B, Motte H, Beeckman T (2020) Exploiting natural variation in root system architecture via genome-wide association studies. J Exp Bot 71 (8):2379-2389. [CrossRef]

- Dinh LT, Ueda Y, Gonzalez D, Tanaka JP, Takanashi H, Wissuwa M (2023) Novel QTL for lateral root density and length improve phosphorus uptake in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rice 16 (1):37. [CrossRef]

- Dissanayaka DMSB, Plaxton WC, Lambers H, Siebers M, Marambe B, Wasaki J (2018) Molecular mechanisms underpinning phosphorus-use efficiency in rice. Plant, Cell & Environment 41 (7):1483-1496. [CrossRef]

- Drew M, Saker L (1978) Nutrient supply and the growth of the seminal root system in barley: III. Compensatory increases in growth of lateral roots, and in rates of phosphate uptake, in response to a localized supply of phosphate. J Exp Bot 29 (2):435-451.

- Drew MC, Saker LR, Barber SA, Jenkins W (1984) Changes in the kinetics of phosphate and potassium absorption in nutrient-deficient barley roots measured by a solution-depletion technique. Planta 160 (6):490-499. [CrossRef]

- Du K, Yang Y, Li J, Wang M, Jiang J, Wu J, Fang Y, Xiang Y, Wang Y (2023) Functional analysis of Bna-miR399c-PHO2 regulatory module involved in phosphorus stress in Brassica napus. Life 13 (2):310.

- El Mazlouzi M, Morel C, Chesseron C, Robert T, Mollier A (2020a) Contribution of external and internal phosphorus sources to grain P loading in durum wheat (Triticum durum L.) grown under contrasting P levels. Frontiers in Plant Science Volume 11 - 2020. [CrossRef]

- El Mazlouzi M, Morel C, Robert T, Yan B, Mollier A (2020b) Phosphorus uptake and partitioning in two durum wheat cultivars with contrasting biomass allocation as affected by different P supply during grain filling. Plant and Soil 449 (1):179-192. [CrossRef]

- Elliott DE, Reuter DJ, Reddy GD, Abbott RJ (1997) Phosphorus nutrition of spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). 2. Distribution of phosphorus in glasshouse-grown wheat and the diagnosis of phosphorus deficiency by plant analysis. Aust J Agr Res 48 (6):869-881.

- Essigmann B, Güler S, Narang RA, Linke D, Benning C (1998) Phosphate availability affects the thylakoid lipid composition and the expression of SQD1, a gene required for sulfolipid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 (4):1950-1955. [CrossRef]

- Fixen P, Brentrup F, Bruulsema T, Garcia F, Norton R, Zingore S (2015) Nutrient/fertilizer use efficiency: measurement, current situation and trends. In: Drechsel P, Heffer P, Magen H, Mikkelsen R, Wichelns D (eds) Managing water and fertilizer for sustainable agricultural intensification, vol 8. International Fertilizer Industry Association (IFA), International Water Management Institute (IWMI), International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI), and International Potash Institute (IPI). , Paris, France,.

- Fixen P, Ludwick A, Olsen S (1983) Phosphorus and potassium fertilization of irrigated alfalfa on calcareous soils: II. Soil phosphorus solubility relationships 1. Soil Sci Soc Am J 47 (1):112-117.

- Foehse D, Jungk A (1983) Influence of phosphate and nitrate supply on root hair formation of rape, spinach and tomato plants. Plant Soil 74 (3):359-368.

- Fradgley N, Evans G, Biernaskie JM, Cockram J, Marr EC, Oliver AG, Ober E, Jones H (2020) Effects of breeding history and crop management on the root architecture of wheat. Plant Soil 452 (1):587-600. [CrossRef]

- Francis B, Aravindakumar CT, Brewer PB, Simon S (2023) Plant nutrient stress adaptation: A prospect for fertilizer limited agriculture. Environ Exp Bot 213:105431. [CrossRef]

- Fujii K (2024) Plant strategy of root system architecture and exudates for acquiring soil nutrients. Ecological Research 39 (5):623-633. [CrossRef]

- Gaume A, Mächler F, De León C, Narro L, Frossard E (2001) Low-P tolerance by maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes: Significance of root growth, and organic acids and acid phosphatase root exudation. Plant Soil 228 (2):253-264. [CrossRef]

- George TS, Gregory PJ, Hocking P, Richardson AE (2008) Variation in root-associated phosphatase activities in wheat contributes to the utilization of organic P substrates in vitro, but does not explain differences in the P-nutrition of plants when grown in soils. Environ Exp Bot 64 (3):239-249. [CrossRef]

- Glass ADM, Beaton JD, Bomke A (1980) Role of P in plant nutrition. Proceedings of the Western Canada Phosphate Symposium:357-368.

- Glassop D, Smith S, Smith F (2005) Cereal phosphate transporters associated with the mycorrhizal pathway of phosphate uptake into roots. Planta 222:688-698. [CrossRef]

- Grant C, Bittman S, Montreal M, Plenchette C, Morel C (2005) Soil and fertilizer phosphorus: Effects on plant P supply and mycorrhizal development. Can J Plant Sci 85 (1):3-14.

- Grant CA, Bailey LD (1994) The effect of tillage and KCl addition on pH, conductance, NO3-N, P, K and Cl distribution in the soil profile. Can J Soil Sci 74 (3):307-314.

- Grant CA, Flaten DN, Tomasiewicz DJ, Sheppard SC (2001) The importance of early season phosphorus nutrition. Can J Plant Sci 81 (2):211-224.

- Grant CA, Lafond GP (1994) The effects of tillage systems and crop rotations on soil chemical properties of a Black Chernozemic soil. Can J Soil Sci 74 (3):301-306.

- Green DG, Ferguson WS, Warder FG (1973) Accumulation of toxic levels of phosphorus in the leaves of phosphorus-deficient barley. Can J Plant Sci 53:241-246.

- Griffin AJ, Jungers JM, Bajgain P (2025) Root phenotyping and plant breeding of crops for enhanced ecosystem services. Crop Sci 65 (1):e21315. [CrossRef]

- Gu M, Chen A, Sun S, Xu G (2016) Complex regulation of plant phosphate transporters and the gap between molecular mechanisms and practical application: what is missing? Molecular Plant 9 (3):396-416. [CrossRef]

- Gunes A, Ali I, Mehmet A, and Cakmak I (2006) Genotypic variation in phosphorus efficiency between wheat cultivars grown under greenhouse and field conditions. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 52 (4):470-478. [CrossRef]

- Guo-Liang J (2013) Molecular Markers and Marker-Assisted Breeding in Plants. In: Sven Bode A (ed) Plant Breeding from Laboratories to Fields. IntechOpen, Rijeka, p Ch. 3. [CrossRef]

- Guo Z, Zhang C, Zhao H, Liu Y, Chen X, Zhao H, Chen L, Ruan W, Chen Y, Yuan L, Yi K, Xu L, Zhang J (2025) Vacuolar phosphate efflux transporter ZmVPEs mediate phosphate homeostasis and remobilization in maize leaves. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 67 (2):311-326. [CrossRef]

- Hamdan MF, Tan BC (2024) Genetic modification techniques in plant breeding: A comparative review of CRISPR/Cas and GM technologies. Horticultural Plant Journal. [CrossRef]

- Hamel C, Strullu D-G (2006) Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in field crop production: potential and new direction. Can J Plant Sci 86 (4):941-950.

- Han Y, White PJ, Cheng L (2021) Mechanisms for improving phosphorus utilization efficiency in plants. Ann Bot 129 (3):247-258. [CrossRef]

- Havlin JL, Tisdale SL, Nelson WL, Beaton JD (2014) Soil Fertility and Fertilizers: An Introduction to Nutrient Management. 8th edn. Pearson, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA.

- Hedley M, McLaughlin M (2005) Reactions of phosphate fertilizers and by-products in soils. In: Sims JT, Sharpley AN (eds) Phosphorus: Agriculture and the Environment. vol 46. American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, Soil Science Society of America, Madison, WI, pp 181-252.

- Hettiarachchi GM, Lombi E, McLaughlin MJ, Chittleborough D, Self P (2006) Density changes around phosphorus granules and fluid bands in a calcareous soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J 70 (3):960-966.

- Heuer S, Gaxiola R, Schilling R, Herrera-Estrella L, López-Arredondo D, Wissuwa M, Delhaize E, Rouached H (2017) Improving phosphorus use efficiency: a complex trait with emerging opportunities. The Plant Journal 90 (5):868-885. [CrossRef]

- Hidaka A, Kitayama K (2013) Relationship between photosynthetic phosphorus-use efficiency and foliar phosphorus fractions in tropical tree species. Ecology and Evolution 3 (15):4872-4880. [CrossRef]

- Hinsinger P (1998) How do plant roots acquire mineral nutrients? Chemical processes involved in the rhizosphere. Adv Agron 64:225-265.

- Hinsinger P (2001) Bioavailability of soil inorganic P in the rhizosphere as affected by root-induced chemical changes: A review. Plant Soil 237 (2):173-195.

- Hinsinger P, Gilkes R (1995) Root-induced dissolution of phosphate rock in the rhizosphere of lupins grown in alkaline soil. Soil Res 33 (3):477-489. [CrossRef]

- Hodge A (2004) The plastic plant: root responses to heterogeneous supplies of nutrients. New Phytol 162 (1):9-24. [CrossRef]

- Hoffland E, Findenegg GR, Nelemans JA (1989) Solubilization of rock phosphate by rape - II. Local root exudation of organic acids as a response to P-starvation. Plant Soil 113 (2):161-165.

- Holloway RE, Bertrand I, Frischke AJ, Brace DM, McLaughlin MJ, Shepperd W (2001) Improving fertiliser efficiency on calcareous and alkaline soils with fluid sources of P, N and Zn. Plant Soil 236 (2):209-219.

- Hopkins BG (2015) Phosphorus. In: Barker AV, Pilbeam DJ (eds) Handbook of Plant Nutrition. second edn. CRC press, Boca Ratan, FL, pp 65 -126.

- Hoppo SD, Elliott DE, Reuter DJ (1999) Plant tests for diagnosing phosphorus deficiency in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Aust J Exp Agr 39 (7):857-872.

- IPNI (2016 ) 4R Plant Nutrition Manual: A Manual for Improving the Management of Plant Nutrition. In: Bruulsema TW, Fixen PE, Sulewski GD (eds). International Plant Nutrition Institute, Peachtree Corners, GA, USA,.

- Jakobsen I (1986) Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza in field-grown crops. III. Mycorrhizal infection and rates of phosphorus inflow in pea plants. New Phytol 104:573-581.

- Jeong K, Mattes N, Catausan S, Chin JH, Paszkowski U, Heuer S (2015) Genetic diversity for mycorrhizal symbiosis and phosphate transporters in rice. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 57 (11):969-979. [CrossRef]

- Jha UC, Nayyar H, Parida SK, Beena R, Pang J, Siddique KHM (2023) Breeding and genomics approaches for improving phosphorus-use efficiency in grain legumes. Environ Exp Bot 205:105120. [CrossRef]

- Johnston AE, Poulton PR, Fixen PE, Curtin D (2014) Phosphorus: its efficient use in agriculture. In: Advances in Agronomy, vol 123. Elsevier, pp 177-228.

- Joung JK, Sander JD (2013) TALENs: a widely applicable technology for targeted genome editing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14 (1):49-55. [CrossRef]

- Jungk A, Barber SA (1974) Phosphate uptake rate of corn roots as related to the proportion of the roots exposed to phosphate. Agron J 66:554-557.

- Jungk A, Seeling B, Gerke J (1993) Mobilization of different phosphate fractions in the rhizosphere. Plant Soil 155-156 (1):91-94.

- Kaeppler SM, Parke JL, Mueller SM, Senior L, Stuber C, Tracy WF (2000) Variation among maize inbred lines and detection of quantitative trait loci for growth at low phosphorus and responsiveness to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Crop Sci 40 (2):358-364. [CrossRef]

- Kar G, Peak D, Schoenau JJ (2012) Spatial distribution and chemical speciation of soil phosphorus in a band application. Soil Sci Soc Am J 76 (6):2297-2306.

- Kirk A, Entz M, Fox S, Tenuta M (2011) Mycorrhizal colonization, P uptake and yield of older and modern wheats under organic management. Can J Plant Sci 91 (4):663-667. [CrossRef]

- Konesky D, Siddiqi M, Glass A, Hsiao A (1989) Wild oat and barley interactions: varietal differences in competitiveness in relation to phosphorus supply. Can J Bot 67 (11):3366-3371.

- Kucey R, Janzen H, Leggett M (1989) Microbially mediated increases in plant-available phosphorus. In: Advances in agronomy, vol 42. Elsevier, pp 199-228.

- Kumpf RP, Nowack MK (2015) The root cap: a short story of life and death. J Exp Bot 66 (19):5651-5662. [CrossRef]

- Lambers H (2022) Phosphorus acquisition and utilization in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 73 (Volume 73, 2022):17-42. [CrossRef]

- Lambers H, Cawthray GR, Giavalisco P, Kuo J, Laliberté E, Pearse SJ, Scheible W-R, Stitt M, Teste F, Teste F, Turner BL (2012) Proteaceae from severely phosphorus-impoverished soils extensively replace phospholipids with galactolipids and sulfolipids during leaf development to achieve a high photosynthetic phosphorus-use-efficiency. The New phytologist 196 (4):1098-1108. [CrossRef]

- Lambers H, Cramer MD, Shane MW, Wouterlood M, Poot P, Veneklaas EJ (2003) Structure and functioning of cluster roots and plant responses to phosphate deficiency. Plant Soil 248 (1-2):ix-xix.

- Lee HY, Chen Z, Zhang C, Yoon GM (2019) Editing of the OsACS locus alters phosphate deficiency-induced adaptive responses in rice seedlings. J Exp Bot 70 (6):1927-1940. [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre DD, Glass ADM (1982) Regulation of phosphate influx in barley roots: Effects of phosphate deprivation and reduction of influx with provision of orthophosphate. Physiol Plant 54:199-206.

- Li X, Chen Y, Xu Y, Sun H, Gao Y, Yan P, Song Q, Li S, Zhan A (2024) Genotypic variability in root morphology in a diverse wheat genotypes under drought and low phosphorus stress. Plants 13.

- Lim S, Borza T, Peters RD, Coffin RH, Al-Mughrabi KI, Pinto DM, Wang-Pruski G (2013) Proteomics analysis suggests broad functional changes in potato leaves triggered by phosphites and a complex indirect mode of action against Phytophthora infestans. Journal of proteomics 93:207-223.

- Lipton DS, Blanchar RW, Blevins DG (1987) Citrate, malate, and succinate concentration in exudates from P-sufficient and P-stressed Medicago sativa L. seedlings 1. Plant Physiol 85 (2):315-317. [CrossRef]

- Lisch D (2013) How important are transposons for plant evolution? Nature Reviews Genetics 14 (1):49-61.

- Liu T-Y, Huang T-K, Yang S-Y, Hong Y-T, Huang S-M, Wang F-N, Chiang S-F, Tsai S-Y, Lu W-C, Chiou T-J (2016) Identification of plant vacuolar transporters mediating phosphate storage. Nature Communications 7 (1):11095. [CrossRef]

- Lombi E, McLaughlin MJ, Johnston C, Armstrong RD, Holloway RE (2004) Mobility and lability of phosphorus from granular and fluid monoammonium phosphate differs in a calcareous soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J 68 (2):682-689.

- Lombi E, McLaughlin MJ, Johnston C, Armstrong RD, Holloway RE (2005) Mobility, solubility and lability of fluid and granular forms of P fertiliser in calcareous and non-calcareous soils under laboratory conditions. Plant Soil 269 (1-2):25-34.

- Lombi E, Scheckel KG, Armstrong RD, Forrester S, Cutler JN, Paterson D (2006) Speciation and Distribution of Phosphorus in a Fertilized Soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J 70 (6):2038-2048. [CrossRef]

- Loneragan JF, Asher CJ (1967) Response of plants to phosphate concentration in solution culture: II. Rate of phosphate absorption and its relation to growth. Soil Sci 103 (5):311-318.

- López-Bucio J, de la Vega OM, Guevara-García A, Herrera-Estrella L (2000) Enhanced phosphorus uptake in transgenic tobacco plants that overproduce citrate. Nat Biotechnol 18 (4):450-453. [CrossRef]

- Lopez G, Ahmadi SH, Amelung W, Athmann M, Ewert F, Gaiser T, Gocke MI, Kautz T, Postma J, Rachmilevitch S, Schaaf G, Schnepf A, Stoschus A, Watt M, Yu P, Seidel SJ (2022) Nutrient deficiency effects on root architecture and root-to-shoot ratio in arable crops. Front Plant Sci 13:1067498. [CrossRef]

- Lynch JP (2007a) Rhizoeconomics: the roots of shoot growth limitations. HortScience 42 (5):1107-1109.

- Lynch JP (2007b) Roots of the second green revolution. Australian Journal of Botany 55 (5):493-512.

- Lynch JP (2013) Steep, cheap and deep: an ideotype to optimize water and N acquisition by maize root systems. Ann Bot 112 (2):347-357.

- Lynch JP (2022) Harnessing root architecture to address global challenges. The Plant Journal 109 (2):415-431. [CrossRef]

- Lynch JP, Brown KM (2001) Topsoil foraging–an architectural adaptation of plants to low phosphorus availability. Plant Soil 237:225-237.

- Mabagala FS, Mng'ong'o ME (2022) On the tropical soils; The influence of organic matter (OM) on phosphate bioavailability. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 29 (5):3635-3641. [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes JV, de Sousa SM, Guimaraes CT, Kochian LV (2017) Chapter 7 - The role of root morphology and architecture in phosphorus acquisition: physiological, genetic, and molecular basis. In: Hossain MA, Kamiya T, Burritt DJ, Tran L-SP, Fujiwara T (eds) Plant Macronutrient Use Efficiency. Academic Press, pp 123-147. [CrossRef]

- Maharajan T, Ceasar SA, Ajeesh krishna TP, Ramakrishnan M, Duraipandiyan V, Naif Abdulla AD, Ignacimuthu S (2018) Utilization of molecular markers for improving the phosphorus efficiency in crop plants. Plant Breed 137 (1):10-26. [CrossRef]

- Malhi SS, Johnston AM, Schoenau JJ, Wang ZH, Vera CL (2006) Seasonal biomass accumulation and nutrient uptake of wheat, barley and oat on a Black Chernozem soil in Saskatchewan. Can J Plant Sci 86 (4):1005-1014.

- Malhi SS, Johnston AM, Schoenau JJ, Wang ZH, Vera CL (2007a) Seasonal biomass accumulation and nutrient uptake of canola, mustard, and flax on a Black Chernozem soil in Saskatchewan. J Plant Nutr 30 (4):641-658.

- Malhi SS, Johnston AM, Schoenau JJ, Wang ZH, Vera CL (2007b) Seasonal biomass accumulation and nutrient uptake of pea and lentil on a Black Chernozem soil in Saskatchewan. J Plant Nutr 30 (5):721-737.

- Malhotra H, Vandana, Sharma S, Pandey R (2018) Phosphorus Nutrition: Plant Growth in Response to Deficiency and Excess. Plant Nutrients and Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Manna M, Achary VMM, Islam T, Agrawal PK, Reddy MK (2016) The development of a phosphite-mediated fertilization and weed control system for rice. Scientific Reports 6 (1):24941. [CrossRef]

- Manske GGB, Ortiz-Monasterio JI, Van Ginkel M, González RM, Rajaram S, Molina E, Vlek PLG (2000) Traits associated with improved P-uptake efficiency in CIMMYT's semidwarf spring bread wheat grown on an acid Andisol in Mexico. Plant Soil 221 (2):189-204. [CrossRef]

- Marschner H, Kirkby EA, Cakmak I (1996) Effect of mineral nutritional status on shoot-root partitioning of photoassimilates and cycling of mineral nutrients. J Exp Bot 47 (SPEC. ISS.):1255-1263.

- McBeath TM, Armstrong RD, Lombi E, McLaughlin MJ, Holloway RE (2005) Responsiveness of wheat (Triticum aestivum) to liquid and granular phosphorus fertilisers in southern Australian soils. Aust J Soil Res 43 (2):203-212.

- McGonigle TP, Hutton M, Greenley A, Karamanos R (2011) Role of mycorrhiza in a wheat–flax versus canola–flax rotation: A case study. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 42 (17):2134-2142. [CrossRef]

- McGrail RK, Van Sanford DA, McNear DH (2023) Breeding milestones correspond with changes to wheat rhizosphere biogeochemistry that affect P acquisition. Agronomy 13 (3):813.

- McLaughlin MJ, McBeath TM, Smernik R, Stacey SP, Ajiboye B, Guppy C (2011) The chemical nature of P accumulation in agricultural soils—implications for fertiliser management and design: an Australian perspective. Plant Soil 349 (1-2):69-87.

- Mikwa EO, Wittkop B, Windpassinger SM, Weber SE, Ehrhardt D, Snowdon RJ (2024) Early exposure to phosphorus starvation induces genetically determined responses in Sorghum bicolor roots. Theor Appl Genet 137 (10). [CrossRef]

- Miller MH (2000) Arbuscular mycorrhizae and the phosphorus nutrition of maize: A review of Guelph studies. Can J Plant Sci 80 (1):47-52.

- Mills HA, Jones JB, Jr. (1996) Plant Analysis Handbook II. MicroMacro Publishing, Inc., Jefferson City, MO.

- Mohamed GES, Marshall C (1979) The pattern of distribution of phosphorus and dry matter with time in spring wheat. Ann Bot 44 (6):721-730.

- Monreal MA, Grant CA, Irvine RB, Mohr RM, McLaren DL, Khakbazan M (2011) Crop management effect on arbuscular mycorrhizae and root growth of flax. Can J Plant Sci 91 (2):315-324. [CrossRef]

- Morel C, Plenchette C (1994) Is the isotopically exchangeable phosphate of a loamy soil the plant-available P? Plant Soil 158 (2):287-297.

- Morel C, Tunney H, Plenet D, Pellerin S (2000) Transfer of phosphate ions between soil and solution: Perspectives in soil testing. J Environ Qual 29 (1):50-59.

- Moussa AA, Mandozai A, Jin Y, Qu J, Zhang Q, Zhao H, Anwari G, Khalifa MAS, Lamboro A, Noman M, Bakasso Y, Zhang M, Guan S, Wang P (2021) Genome-wide association screening and verification of potential genes associated with root architectural traits in maize (Zea mays L.) at multiple seedling stages. BMC Genomics 22 (1):558. [CrossRef]

- Müller J, Toev T, Heisters M, Teller J, Moore Katie L, Hause G, Dinesh Dhurvas C, Bürstenbinder K, Abel S (2015) Iron-dependent callose deposition adjusts root meristem maintenance to phosphate availability. Developmental Cell 33 (2):216-230. [CrossRef]

- Murovec J, Bohanec B (2012) Haploids and Doubled Haploids in Plant Breeding. In: Abdurakhmonov IY (ed) Plant Breeding. IntecOpen, pp 87-106.

- Nadeem M, Mollier A, Morel C, Vives A, Prud’homme L, Pellerin S (2011) Relative contribution of seed phosphorus reserves and exogenous phosphorus uptake to maize (Zea mays L.) nutrition during early growth stages. Plant Soil 346 (1):231-244. [CrossRef]

- Nahampun HN, López-Arredondo D, Xu X, Herrera-Estrella L, Wang K (2016) Assessment of ptxD gene as an alternative selectable marker for Agrobacterium-mediated maize transformation. Plant Cell Rep 35 (5):1121-1132. [CrossRef]

- Navea IP, Yang S, Tolangi P, Sumabat RM, Zhang W, Chin JH (2024) Enhancement of rice traits for the maintenance of the phosphorus balance between rice plants and the soil. Current Plant Biology 38:100332. [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Rivera JO, Alejo-Jacuinde G, Nájera-González H-R, López-Arredondo D (2022) Prospects of genetics and breeding for low-phosphate tolerance: an integrated approach from soil to cell. Theor Appl Genet 135 (11):4125-4150. [CrossRef]

- Oo AZ, Tsujimoto Y, Mukai M, Nishigaki T, Takai T, Uga Y (2024) Significant interaction between root system architecture and stratified phosphorus availability for the initial growth of rice in a flooded soil culture. Rhizosphere 31:100947. [CrossRef]

- Ouma E, Dickson L, Matonyei T, Were B, Joyce A, Too E, Augustino O, Gudu S, Peter K, John O, Caleb O (2012) Development of maize single cross hybrids for tolerance to low phosphorus. African Journal of plant science 6:394-402. [CrossRef]

- Ozanne PG (1980) Phosphate nutrition of plants - A general treatise. The Role of Phosphorus in Agriculture:559-589.

- Pan X-w, Li W-b, Zhang Q-y, Li Y-h, Liu M-s (2008) Assessment on phosphorus efficiency characteristics of soybean genotypes in phosphorus-deficient soils. Agr Sci China 7 (8):958-969. [CrossRef]

- Pan Y, Song Y, Zhao L, Chen P, Bu C, Liu P, Zhang D (2022) The genetic basis of phosphorus utilization efficiency in plants provide new insight into woody perennial plants improvement. Int J Mol Sci 23 (4). [CrossRef]

- Pandeya D, López-Arredondo DL, Janga MR, Campbell LM, Estrella-Hernández P, Bagavathiannan MV, Herrera-Estrella L, Rathore KS (2018) Selective fertilization with phosphite allows unhindered growth of cotton plants expressing the ptxD gene while suppressing weeds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (29):E6946-E6955. doi:doi:10.1073/pnas.1804862115.

- Penn CJ, Camberato JJ (2019) A critical review on soil chemical rocesses that control how soil pH affects phosphorus availability to plants. Agriculture 9 (6):120.

- Pierre W, Parker F (1927) Soil phosphorus studies: II. The concentration of organic and inorganic phosphorus in the soil solution and soil extracts and the availibility of the organic phosphorus to plants. Soil Sci 24 (2):119-128.

- Pierzynski GM, McDowell RW (2005) Chemistry, cycling, and potential movement of inorganic phosphorus in soils. Phosphorus: agriculture and the environment (phosphorusagric):53-86.

- Plaxton W, Lambers H (2015) Phosphorus: back to the roots. Annual plant reviews 48:3-15.

- Poirier Y, Jaskolowski A, Clúa J (2022) Phosphate acquisition and metabolism in plants. Current Biology 32 (12):R623-R629. [CrossRef]

- Raboy V (2002) Progress in breeding low phytate crops. J Nutr 132 (3):503S-505S. [CrossRef]

- Rajamanickam V, Sevanthi AM, Swarbreck SM, Gudi S, Singh N, Singh VK, Wright TIC, Bentley AR, Muthamilarasan M, Das A, Chinnusamy V, Pandey R (2024) High-throughput root phenotyping and association analysis identified potential genomic regions for phosphorus use efficiency in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Planta 260 (6):142. [CrossRef]

- Raven PH, Evert RF, Eichhorn SE (2005) Biology of Plants. Seventh edn. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York.

- Ribeiro CAG, de Sousa Tinoco SM, de Souza VF, Negri BF, Gault CM, Pastina MM, Magalhaes JV, Guimarães LJM, de Barros EG, Buckler ES, Guimaraes CT (2023) Genome-wide association Sstudy for root morphology and phosphorus acquisition efficiency in diverse maize panels. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24 (7):6233.

- Richardson AE (2001) Prospects for using soil microorganisms to improve the acquisition of phosphorus by plants. Funct Plant Biol 28 (9):897-906. [CrossRef]

- Richardson AE, Hocking PJ, Simpson RJ, George TS (2009) Plant mechanisms to optimise access to soil phosphorus. Crop Pasture Sci 60 (2):124-143.

- Richardson AE, Lynch JP, Ryan PR, Delhaize E, Smith FA, Smith SE, Harvey PR, Ryan MH, Veneklaas EJ, Lambers H, Oberson A, Culvenor RA, Simpson RJ (2011) Plant and microbial strategies to improve the phosphorus efficiency of agriculture. Plant Soil 349 (1):121-156. [CrossRef]

- Roberts TL, Johnston AE (2015) Phosphorus use efficiency and management in agriculture. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 105:275-281. [CrossRef]

- Rose T, Liu L, Wissuwa M (2013) Improving phosphorus efficiency in cereal crops: Is breeding for reduced grain phosphorus concentration part of the solution? Frontiers in Plant Science 4. [CrossRef]

- Rossnagel BG, Zatorski T, Arganosa G, Beattie AD (2008) Registration of ‘CDC Lophy-I’ Barley. Journal of Plant Registrations 2 (3):169-173. [CrossRef]

- Rouached H, Arpat AB, Poirier Y (2010) Regulation of phosphate starvation responses in plants: signaling players and cross-talks. Molecular Plant 3 (2):288-299.

- Ryan MH, Graham JH (2002) Is there a role for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in production agriculture? Plant Soil 244 (1-2):263-271.

- Ryan MH, Kirkegaard JA (2012) The agronomic relevance of arbuscular mycorrhizas in the fertility of Australian extensive cropping systems. Agr Ecosyst Environ 163:37-53. [CrossRef]

- Ryan MH, Small DR, Ash JE (2000) Phosphorus controls the level of colonisation by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in conventional and biodynamic irrigated dairy pastures. Aust J Exp Agr 40 (5):663-670.

- Salas-González I, Reyt G, Flis P, Custódio V, Gopaulchan D, Bakhoum N, Dew TP, Suresh K, Franke RB, Dangl JL (2021) Coordination between microbiota and root endodermis supports plant mineral nutrient homeostasis. Science 371 (6525):eabd0695.

- Sample EC, Soper RJ, Racz GJ (1980) Reaction of phosphate fertilizers in soils. In: Khasawneh FE, Sample EC, Kamprath EJ (eds) The Role of Phosphorus in Agriculture. ASA, CSSA, and SSSA, Madision, , WI, pp 262-310. [CrossRef]

- Schachtman DP, Reid RJ, Ayling SM (1998) Phosphorus uptake by plants: from soil to cell. Plant Physiol 116 (2):447-453. [CrossRef]

- Schjørring JK, Jensén P (1984) Phosphorus nutrition of barley, buckwheat and rape seedlings. I. Influence of seed-borne P and external P levels on growth, P content and P/P-fractionation in shoots and roots32 31. Physiol Plant 61:577-583.

- Schneider A, Morel C (2000) Relationship between the isotopically exchangeable and resin-extractable phosphate of deficient to heavily fertilized soil. Eur J Soil Sci 51 (4):709-715.

- Schroeder JI, Delhaize E, Frommer WB, Guerinot ML, Harrison MJ, Herrera-Estrella L, Horie T, Kochian LV, Munns R, Nishizawa NK (2013) Using membrane transporters to improve crops for sustainable food production. Nature 497 (7447):60.

- Sharma S, Pinson SRM, Gealy DR, Edwards JD (2021) Genomic prediction and QTL mapping of root system architecture and above-ground agronomic traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.) with a multitrait index and Bayesian networks. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 11 (10). [CrossRef]

- Shen J, Yuan L, Zhang J, Li H, Bai Z, Chen X, Zhang W, Zhang F (2011) Phosphorus dynamics: from soil to plant. Plant Physiol 156 (3):997-1005. [CrossRef]

- Shen Y, Zhou G, Liang C, Tian Z (2022) Omics-based interdisciplinarity is accelerating plant breeding. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 66:102167. [CrossRef]

- Slatkin M (2008) Linkage disequilibrium--understanding the evolutionary past and mapping the medical future. Nat Rev Genet 9 (6):477-485. [CrossRef]

- Smith SE, Jakobsen I, Grønlund M, Smith FA (2011) Roles of arbuscular mychorrhizas in plant phosphorus nutrition: Interactions between pathways of phosphorus uptake in arbuscular mycorrhizal roots have important implications for understanding and manipulating plant phosphorus acquisition. Plant Physiol 156 (3):1050-1057. [CrossRef]

- Sparvoli F, Cominelli E (2015) Seed biofortification and phytic acid reduction: a conflict of interest for the plant? Plants (Basel) 4 (4):728-755. [CrossRef]

- Stetter MG, Schmid K, Ludewig U (2015) Uncovering genes and ploidy involved in the high diversity in root hair density, length and response to local scarce phosphate in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One 10 (3):e0120604. [CrossRef]

- Strong WM, Soper RJ (1974a) Phosphorus utilization by flax, wheat, rape, and buckwheat from a band or pellet-like application. I. Reaction zone proliferation. Agron J 66:597-601.

- Strong WM, Soper RJ (1974b) Phosphorus utilization by flax, wheat, rape, and buckwheat from a band or pellet-like application. II. Influence of reaction zone phosphorus concentration and soil phosphorus supply. Agron J 66:601-605.

- Sultenfuss J, Doyle W (1999) Functions of phosphorus in plants. Better Crops 83 (1):6-7.

- Sutton PJ, Peterson GA, Sander DH (1983) Dry matter production in tops and roots of winter wheat as affected by phosphorus availability during various growth stages. Agron J 75:657-663.

- Syers J, Johnston A, Curtin D (2008) Efficiency of soil and fertilizer phosphorus use., FAO Fertilizer and Plant Nutrition Bulletin No. 18.(FAO: Rome).

- Tao J, Bauer DE, Chiarle R (2023) Assessing and advancing the safety of CRISPR-Cas tools: from DNA to RNA editing. Nature Communications 14 (1):212. [CrossRef]

- Theodorou ME, Plaxton WC (1993) Metabolic adaptations of plant respiration to nutritional phosphate deprivation. Plant Physiol 101 (2):339-344. [CrossRef]

- Tomasiewicz DJ (2000) Advancing the understanding and interpretation of plant and soil tests for phosphorus in Manitoba. University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB.

- van de Wiel CC, van der Linden CG, Scholten OE (2016) Improving phosphorus use efficiency in agriculture: opportunities for breeding. Euphytica 207:1-22.

- Vance CP, Uhde-Stone C, Allan DL (2003) Phosphorus acquisition and use: critical adaptations by plants for securing a nonrenewable resource. New Phytol 157 (3):423-447. [CrossRef]

- Veneklaas EJ, Lambers H, Bragg J, Finnegan PM, Lovelock CE, Plaxton WC, Price CA, Scheible W-R, Shane MW, White PJ, Raven JA (2012) Opportunities for improving phosphorus-use efficiency in crop plants. New Phytol 195 (2):306-320. [CrossRef]

- Veršulienė A, Hirte J, Ciulla F, Camenzind M, Don A, Durand-Maniclas F, Heinemann H, Herrera JM, Hund A, Seidel F, da Silva-Lopes M, Toleikienė M, Visse-Mansiaux M, Yu K, Bender SF (2024) Wheat varieties show consistent differences in root colonization by mycorrhiza across a European pedoclimatic gradient. Eur J Soil Sci 75 (4):e13543. [CrossRef]

- Vlčko T, Ohnoutková L (2020) Allelic variants of CRISPR/Cas9 induced mutation in an inositol trisphosphate 5/6 kinase gene manifest different phenotypes in barley. Plants 9 (2):195.

- Wachsman G, Sparks EE, Benfey PN (2015) Genes and networks regulating root anatomy and architecture. New Phytol 208 (1):26-38. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Deng M, Xu J, Zhu X, Mao C (2018) Molecular mechanisms of phosphate transport and signaling in higher plants. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 74:114-122. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Liu D (2018) Functions and regulation of phosphate starvation-induced secreted acid phosphatases in higher plants. Plant Sci 271:108-116. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Cheng L, Xiong C, Whalley WR, Miller AJ, Rengel Z, Zhang F, Shen J (2024) Understanding plant–soil interactions underpins enhanced sustainability of crop production. Trends Plant Sci 29 (11):1181-1190. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Whalley WR, Miller AJ, White PJ, Zhang F, Shen J (2020) Sustainable cropping requires adaptation to a heterogeneous rhizosphere. Trends Plant Sci 25 (12):1194-1202. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Krogstad T, Clarke JL, Hallama M, Øgaard AF, Eich-Greatorex S, Kandeler E, Clarke N (2016) Rhizosphere organic anions play a minor role in improving crop species' ability to take up residual phosphorus (P) in agricultural soils low in P availability. Front Plant Sci 7:1664. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Lambers H (2020) Root-released organic anions in response to low phosphorus availability: recent progress, challenges and future perspectives. Plant Soil 447 (1):135-156. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Wang F, Lu H, Liu Y, Mao C (2021) Phosphate uptake and transport in plants: An elaborate regulatory system. Plant Cell Physiol 62 (4):564-572. [CrossRef]

- Watson A, Ghosh S, Williams MJ, Cuddy WS, Simmonds J, Rey MD, Asyraf Md Hatta M, Hinchliffe A, Steed A, Reynolds D, Adamski NM, Breakspear A, Korolev A, Rayner T, Dixon LE, Riaz A, Martin W, Ryan M, Edwards D, Batley J, Raman H, Carter J, Rogers C, Domoney C, Moore G, Harwood W, Nicholson P, Dieters MJ, DeLacy IH, Zhou J, Uauy C, Boden SA, Park RF, Wulff BBH, Hickey LT (2018) Speed breeding is a powerful tool to accelerate crop research and breeding. Nat Plants 4 (1):23-29. [CrossRef]

- White PJ, Veneklaas EJ (2012) Nature and nurture: the importance of seed phosphorus content. Plant Soil 357 (1):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Yadav S, Ross EM, Aitken KS, Hickey LT, Powell O, Wei X, Voss-Fels KP, Hayes BJ (2021) A linkage disequilibrium-based approach to position unmapped SNPs in crop species. BMC Genomics 22 (1):773. [CrossRef]

- Yamaji N, Takemoto Y, Miyaji T, Mitani-Ueno N, Yoshida KT, Ma JF (2017) Reducing phosphorus accumulation in rice grains with an impaired transporter in the node. Nature 541 (7635):92-95. [CrossRef]

- Yan J, Wang X (2023) Machine learning bridges omics sciences and plant breeding. Trends Plant Sci 28 (2):199-210. [CrossRef]

- Yang S-Y, Grønlund M, Jakobsen I, Grotemeyer MS, Rentsch D, Miyao A, Hirochika H, Kumar CS, Sundaresan V, Salamin N, Catausan S, Mattes N, Heuer S, Paszkowski U (2012) Nonredundant regulation of rice arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis by two members of the PHOSPHATE TRANSPORTER1 gene family. The Plant Cell 24 (10):4236-4251. [CrossRef]

- Yang S-Y, Huang T-K, Kuo H-F, Chiou T-J (2017) Role of vacuoles in phosphorus storage and remobilization. J Exp Bot 68 (12):3045-3055.

- Yang S-Y, Lin W-Y, Hsiao Y-M, Chiou T-J (2024) Milestones in understanding transport, sensing, and signaling of the plant nutrient phosphorus. The Plant Cell 36 (5):1504-1523. [CrossRef]

- Yuan P, Liu H, Wang X, Hammond JP, Shi L (2023) Genome-wide association study reveals candidate genes controlling root system architecture under low phosphorus supply at seedling stage in Brassica napus. Mol Breed 43 (8). [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Kaeppler SM, Lynch JP (2005) Topsoil foraging and phosphorus acquisition efficiency in maize (Zea mays). Funct Plant Biol 32 (8):749-762. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).