Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This comprehensive review gathers the current knowledge on the link between plastics wastes and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) selection and transmission in aquatic ecosystems that can lead to the ARG contamination of fishery products, a relevant source of MPs introduction in the food chain. Indeeed, plastic debris in aquatic environments aare covered by a biofilm (plastisphere) in which antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) are selected and the horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of ARGs is facilitated. The types of plastic wastes considered in this study for their role in ARG enrichment are mainly microplastics (MPs) but also nanoplastics (NPs) and macroplastics. Studies regarding freshwaters, seawaters, aquaculture farms and ARG accumulation favored by MPs in aquatic animals were considered. Most studies were focused on the identification of the microbiota and its correlation with ARGs in plastic biofilms and a few evaluated the effect of MPs on ARG selection in aquatic animals. An abundance of ARGs higher in the plastisphere than in the surrounding water or natural solid substrates such as sand, rocks and wood was repeatedly reported. The studies regarding aquatic animals showed that MPs alone or in association with antibiotics favored the increase of ARGs in the exposed organisms with the risk of their introduction in the food chain. Therefore, the reduction of plastic pollution in waterbodies and in aquaculture waters could mitigate the ARG threat. Further investigations focused on ARG selection in aquatic animals should be carried out to better assess the health risks and increase the awareness on this ARG transmission route to adopt appropriate countermeasures.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Antibiotic Adsorption on Plastic Polymers

3. Demonstrations of ARG HGT in the Plastisphere

4. Occurrence of ARGs and Bacterial Hosts on Plastic Fragments in Waterbodies

4.1. ARGs in the Plastisphere in Freshwater

4.1.2. The Effect of WWTP Effluents on the Plastisphere ARG Content

4.2. ARG Presence in the Plastisphere In Seawater

4.3. ARG Presence in the Plastisphere in Estuaries and Brackish Waters

4.4. The Role of Viruses in ARG Transmission in the Plastisphere

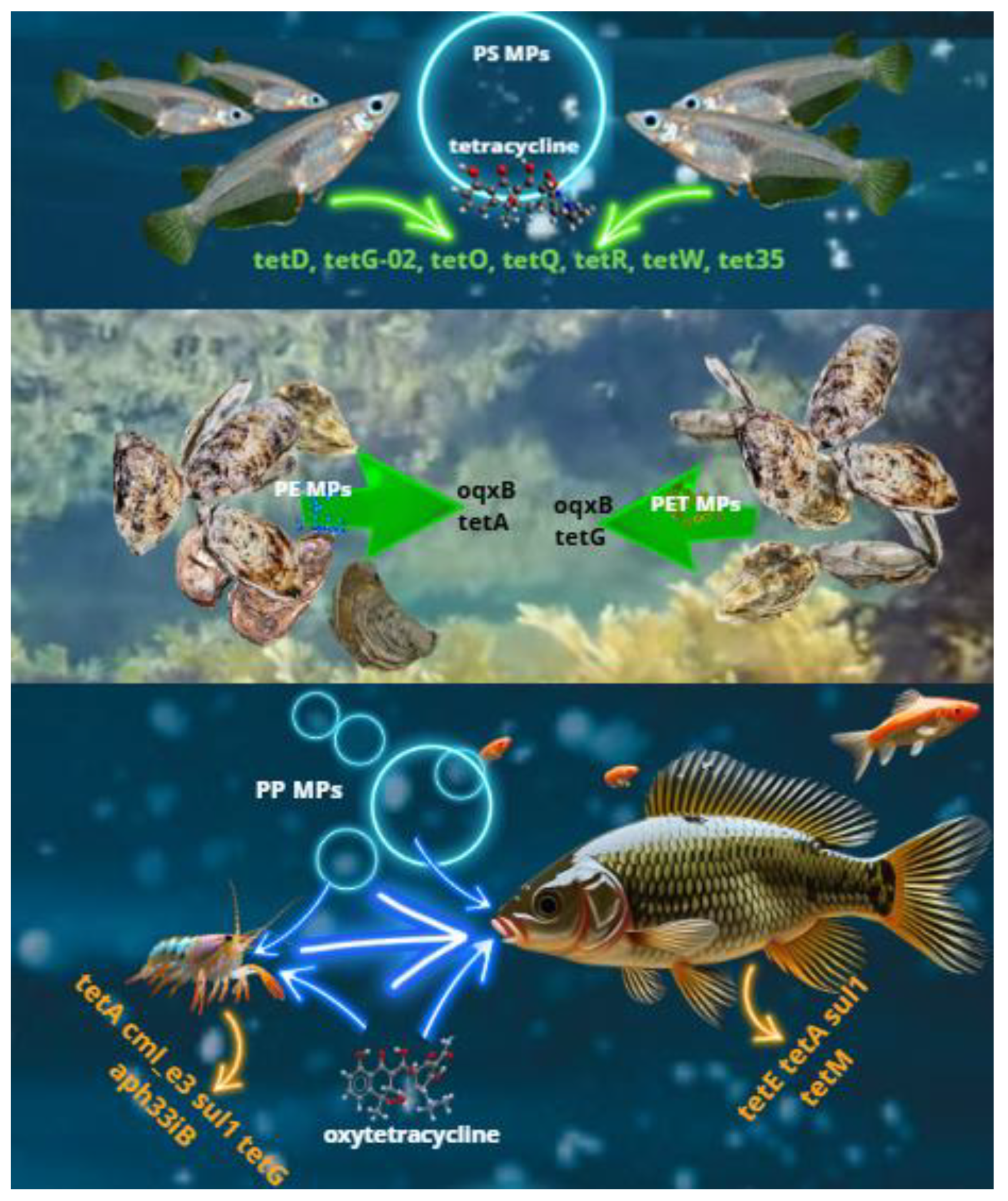

5. Effects of MPs on ARG Selection in Aquatic Animals and Fishery Products

5.1. Presence of ARGs in MPs in Aquaculture Farms

5.2. Selection of ARGs in Aquatic Animals Induced by MPs

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| ACE | Abundance-based Coverage Estimator |

| ADI | Acceptable daily intake |

| AHL | Acyl-homoserine lactones |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| APS | Artificial plastic substrate |

| ARB | Antibiotic-resistant bacteria |

| ARG | Antibiotic resistance gene |

| ARISA | Automated ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis |

| BDP | Biodegradable plastic |

| BPA | Bisphenol A |

| CF | Cellophane |

| CR | Cancer risk |

| DBP | Dibutyl phthalate |

| DCFH-DA | 2′, 7′ - Dichlorofluorescein diacetate |

| DEGM | Dietary exposure dose for the human gut microbiome |

| DEHP | (2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate |

| EDI | Estimated daily intake |

| EPS | Extracellular polysaccharides |

| ESBL | Extended spectrum beta-lactamase |

| ESKAPE | E. faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp. |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared |

| GBDT | Gradient boosting decision tree |

| GHRI | Genotypic health risk index |

| HDPE | High-density PE |

| HGT | Horizontal gene transfer |

| HQ | Human health risk quotient |

| HT-qPCR | High throughput qPCR |

| HTS | High throughput sequencing |

| ICE | Integrative conjugative element |

| IHRI | Integrated health risk index |

| LDPE | Low-density PE |

| LGBM | Light Gradient Boosting machine |

| LSCM | Laser scanning confocal microscopy |

| MAG | Metagenome assembled genome |

| MALDI | Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization |

| MALDI-TOF | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight |

| MAR | Multiple antibiotic resistance |

| MARB | Multiresistant bacteria |

| MCDM | Multiple criteria decision making |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| MDRG | Multidrug resistance gene |

| MGE | Mobile genetic element |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MLP | Multilayer perceptron |

| MLR | Multiple linear regression |

| MLS | Macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin |

| MP | Microplastic |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant S aureus |

| MSC | Minimal Selective Concentration |

| NBP | Non-biodegradable plastic |

| NCM | Neutral community model |

| NP | Nanoplastic |

| OTU | Operational taxonomic unit |

| PA | Polyamide |

| PAH | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon |

| PBAT | Poly-butyleneadipate-co-terephthalate |

| PBD | Polybutadiene |

| PBS | Polybutylene succinate |

| PCB | Polychlorinated biphenyl |

| PCL | Polycaprolactone |

| PCoA | Principal coordinate analysis |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PET | Polyethylene therephthalate |

| PF | Phenol formaldehyde |

| PF | PE-fiber |

| PFP | Pentafluorophenyl acrylate |

| PFP | PE-fiber-PE |

| PHA | Polyhydroxyalkanoate |

| PHB | Polyhydroxybutyrate |

| PLA | Poly lactic acid |

| PLC | Polyisoprene chlorinated |

| PMMA | polymethyl methacrylate |

| PMMA | Polymethyl methacrylate |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| ppLFER | Poly-parameter Linear Free-Energy Relationships |

| PPR | Projection pursuit regression |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PTDL | Polytridecanolactone |

| PU | Polyurethane |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| QS | Quorum sensing |

| QSPR | Quantitative Structure Property Relationship |

| RF | Random forest |

| RM | Random forest |

| RMSD | Root-mean square deviation |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SAN | Styrene acrylonitrile resin |

| SC | Specific conductivity |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanation |

| SRA | Sequence Read Archive |

| SSA | Specific surface area |

| T4SS | Type IV secretion system |

| TAOC | Total antioxidant capacity |

| TDS | Total dissolved solids |

| THQ | Target hazard quotients |

| TOC | Total organic carbon |

| TWP | Tire wear particles |

| vOTU | Viral operational taxonomic unit |

| WGS | Whole genome sequencing |

| W-LDPE | Waste LDPE |

| WWTP | Wastewater treatment plant |

| XGB | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Global Burden of Disease 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance 1990-2021: A Systematic Analysis with Forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Assessment of agricultural plastics and their sustainability a call for action. Rome 2021. https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/94eb5786-232a-496f-8fcf-215a59ebb4e3 (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Khare, T.; Mathur, V.; Kumar, V. Agro-Ecological Microplastics Enriching the Antibiotic Resistance in Aquatic Environment. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2024, 37, 100534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigault, J.; Halle, A.T.; Baudrimont, M.; Pascal, P.-Y.; Gauffre, F.; Phi, T.-L.; El Hadri, H.; Grassl, B.; Reynaud, S. Current Opinion: What Is a Nanoplastic? Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberghini, L.; Truant, A.; Santonicola, S.; Colavita, G.; Giaccone, V. Microplastics in Fish and Fishery Products and Risks for Human Health: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonicola, S.; Volgare, M.; Rossi, F.; Castaldo, R.; Cocca, M.; Colavita, G. Detection of Fibrous Microplastics and Natural Microfibers in Fish Species (Engraulis Encrasicolus, Mullus Barbatus and Merluccius Merluccius) for Human Consumption from the Tyrrhenian Sea. Chemosphere 2024, 363, 142778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgare, M.; Santonicola, S.; Cocca, M.; Avolio, R.; Castaldo, R.; Errico, M.E.; Gentile, G.; Raimo, G.; Gasperi, M.; Colavita, G. A Versatile Approach to Evaluate the Occurrence of Microfibers in Mussels Mytilus Galloprovincialis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonicola, S.; Volgare, M.; Schiano, M.E.; Cocca, M.; Colavita, G. A Study on Textile Microfiber Contamination in the Gastrointestinal Tracts of Merluccius Merluccius Samples from the Tyrrhenian Sea. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2024, 13, 12216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ling, W.; Hou, C.; Yang, J.; Xing, Y.; Lu, Q.; Wu, T.; Gao, Z. Global Distribution Characteristics and Ecological Risk Assessment of Microplastics in Aquatic Organisms Based on Meta-Analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 491, 137977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, H. Adsorption of Antibiotics on Microplastics. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettler, E.R.; Mincer, T.J.; Amaral-Zettler, L.A. Life in the “Plastisphere”: Microbial Communities on Plastic Marine Debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7137–7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, T.S.; Cole, M.; Lewis, C. Interactions of Microplastic Debris throughout the Marine Ecosystem. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, J.; Li, W. Conjugative Antibiotic-Resistant Plasmids Promote Bacterial Colonization of Microplastics in Water Environments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 430, 128443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Huang, X.; Xie, Z.; Ding, Z.; Wei, H.; Jin, Q. A Review Focusing on Mechanisms and Ecological Risks of Enrichment and Propagation of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Mobile Genetic Elements by Microplastic Biofilms. Environ. Res. 2024, 251 Pt 2, 118737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ying, C.; Luo, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, R.; Li, J. Photoaging Processes of Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics Enhance the Adsorption of Tetracycline and Facilitate the Formation of Antibiotic Resistance. Chemosphere 2023, 320, 137820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberbeckmann, S.; Kreikemeyer, B.; Labrenz, M. Environmental Factors Support the Formation of Specific Bacterial Assemblages on Microplastics. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, M.J.; Ansari, A.J.; Hai, F.I. Antibiotic Sorption onto Microplastics in Water: A Critical Review of the Factors, Mechanisms and Implications. Water Res. 2023, 233, 119790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Kong, L.; Han, D.; Kuang, M.; Li, L.; Song, X.; Li, N.; Shi, Q.; Qin, X.; Wu, Y.; Wu, D.; Xu, Z. Deciphering the Adsorption Mechanisms between Microplastics and Antibiotics: A Tree-Based Stacking Machine Learning Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, S.; Raissi, H.; Farzad, F. The role of microplastics as vectors of antibiotic contaminants via a molecular simulation approach. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 27007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.D.; Kirtane, A.; Schefer, R.B.; Mitrano, D.M. EDNA Adsorption onto Microplastics: Impacts of Water Chemistry and Polymer Physiochemical Properties. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 7588–7599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Meng, X.; Dieketseng, M.Y.; Wang, X.; Yan, S.; Wang, B.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, G. A Neglected Risk of Nanoplastics as Revealed by the Promoted Transformation of Plasmid-Borne Ampicillin Resistance Gene by Escherichia Coli. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 4946–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, K.; Wang, J.; Feng, C.; Chen, Y.; Shi, J.; Ding, Y.; Deng, C.; Liu, X. Microplastic Biofilm: An Important Microniche That May Accelerate the Spread of Antibiotic Resistance Genes via Natural Transformation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Huang, C.; Yu, H.; Yang, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhao, B.; Zhong, T.; Zhang, L.; Peng, W.; Gong, W.; Ding, Y. Quorum Sensing Regulating the Heterogeneous Transformation of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Microplastic Biofilms. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Andres, M.; Klümper, U.; Rojas-Jimenez, K.; Grossart, H.-P. Microplastic Pollution Increases Gene Exchange in Aquatic Ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffer, Y.D.; Abdolahpur Monikh, F.; Uli, K.; Grossart, H.-P. Tire Wear Particles Enhance Horizontal Gene Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Aquatic Ecosystems. Environ. Res. 2024, 263 Pt 3, 120187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, T.; Li, B.; Liu, F.; Wu, B.; Dobson, P.S.; Yin, H.; Chen, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Huang, X. The Effects of Small Plastic Particles on Antibiotic Resistance Gene Transfer Revealed by Single Cell and Community Level Analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, N.; Bo, J.; Meng, X.; Chen, Y.; Qin, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, W. Microplastic Biofilms Promote the Horizontal Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Estuarine Environments. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 202, 106777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Pu, Q.; Ding, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Hou, J. Synergistic Effect of Horizontal Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes between Bacteria Exposed to Microplastics and per/Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: An Explanation from Theoretical Methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 492, 138208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Shao, M.; Wei, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Luo, X.; Li, F.; Zheng, H. Microplastics Enhance the Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Mariculture Sediments by Enriching Host Bacteria and Promoting Horizontal Gene Transfer. Eco Environ Health 2025, 4, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aßhauer, K.P.; Wemheuer, B.; Daniel, R.; Meinicke, P. Tax4Fun: Predicting Functional Profiles from Metagenomic 16S rRNA Data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2882–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Sachsenmeier, K.; Zhang, L.; Sult, E.; Hollingsworth, R.E.; Yang, H. A New Bliss Independence Model to Analyze Drug Combination Data. J. Biomol. Screen. 2014, 19, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zeng, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Yue, L.; Wang, C.; Chen, F.; Wang, Z. Biodegradable Microplastics and Dissemination of Antibiotic Resistance Genes: An Undeniable Risk Associated with Plastic Additives. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 372, 125952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Guo, S.; Ahmad, S.; Song, Y.; Gao, P.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Ding, N. Effects Comparison between the Secondary Nanoplastics Released from Biodegradable and Conventional Plastics on the Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes between Bacteria. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 317, 120680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.; Wang, L.; Tang, J. The Combination of Polystyrene Microplastics and Di (2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Promotes the Conjugative Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes between Bacteria. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 289, 117681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, N.; Muhvich, J.; Ching, C.; Gomez, B.; Horvath, E.; Nahum, Y.; Zaman, M.H. Effects of Microplastic Concentration, Composition, and Size on Escherichia Coli Biofilm-Associated Antimicrobial Resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e0228224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Yang, M.; Yin, K.; Wang, J.; Tang, L.; Lei, B.; Yang, L.; Kang, A.; Sun, H. Size- and Surface Charge-Dependent Hormetic Effects of Microplastics on Bacterial Resistance and Their Interactive Effects with Quinolone Antibiotic. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruti, V.C.; Kutralam-Muniasamy, G.; Pérez-Guevara, F. Diagnostic Toolbox for Plastisphere Studies: A Review. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2024, 181, 117996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Li, S.; Tao, C.; Chen, W.; Chen, M.; Zong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, B. Understanding the Mechanism of Microplastic-Associated Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Aquatic Ecosystems: Insights from Metagenomic Analyses and Machine Learning. Water Res. 2024, 268 Pt A, 122570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Pan, X. Microplastic Biodegradability Dependent Responses of Plastisphere Antibiotic Resistance to Simulated Freshwater-Seawater Shift in Onshore Marine Aquaculture Zones. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 331 Pt 2, 121828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qin, X.; Guo, J.; Jia, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y. Evidence of Selective Enrichment of Bacterial Assemblages and Antibiotic Resistant Genes by Microplastics in Urban Rivers. Water Res. 2020, 183, 116113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Chen, Q.-L.; Chen, M.-L.; Li, H.-Z.; Liao, H.; Pu, Q.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Cui, L. Temporal Dynamics of Antibiotic Resistome in the Plastisphere during Microbial Colonization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 11322–11332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughini-Gras, L.; van der Plaats, R.Q.J.; van der Wielen, P.W.J.J.; Bauerlein, P.S.; de Roda Husman, A.M. Riverine Microplastic and Microbial Community Compositions: A Field Study in the Netherlands. Water Res. 2021, 192, 116852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pleiter, M.; Velázquez, D.; Casero, M.C.; Tytgat, B.; Verleyen, E.; Leganés, F.; Rosal, R.; Quesada, A.; Fernández-Piñas, F. Microbial Colonizers of Microplastics in an Arctic Freshwater Lake. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Jin, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, C.; Qiu, Z. Distinct Profile of Bacterial Community and Antibiotic Resistance Genes on Microplastics in Ganjiang River at the Watershed Level. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Zhu, L.; Yang, K.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Cui, L. Impact of Urbanization on Antibiotic Resistome in Different Microplastics: Evidence from a Large-Scale Whole River Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 8760–8770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Luo, Q.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, P.; Yang, X.; Huang, Q.; Su, J. Watershed Urbanization Enhances the Enrichment of Pathogenic Bacteria and Antibiotic Resistance Genes on Microplastics in the Water Environment. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Lu, J.; Shen, C.; Wang, J.; Li, F. Deciphering the Mechanisms Shaping the Plastisphere Antibiotic Resistome on Riverine Microplastics. Water Res. 2022, 225, 119192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Qiu, P.; Chen, B.; Xu, C.; Dong, W.; Liu, T. Microplastics Can Selectively Enrich Intracellular and Extracellular Antibiotic Resistant Genes and Shape Different Microbial Communities in Aquatic Systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Bartlam, M.; Wang, Y. Integrated Metagenomic and Metatranscriptomic Analysis Reveals Actively Expressed Antibiotic Resistomes in the Plastisphere. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 430, 128418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Pan, X. Persistent versus Transient, and Conventional Plastic versus Biodegradable Plastic? -Two Key Questions about Microplastic-Water Exchange of Antibiotic Resistance Genes. Water Res. 2022, 222, 118899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferheen, I.; Spurio, R.; Mancini, L.; Marcheggiani, S. Detection of Morganella Morganii Bound to a Plastic Substrate in Surface Water. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 32, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Q.; Zhang, C.-M.; Yuan, Q.-Q.; Wu, K. New Insight into the Effect of Microplastics on Antibiotic Resistance and Bacterial Community of Biofilm. Chemosphere 2023, 335, 139151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Bai, R.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Guo, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, F. Metagenomic Insights into Ecological Risk of Antibiotic Resistome and Mobilome in Riverine Plastisphere under Impact of Urbanization. Environ. Int. 2024, 190, 108946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, R.; Zullo, R.; Di Cesare, A.; Piscia, R.; Musazzi, S.; Corno, G.; Volta, P.; Galafassi, S. Traditional and Biodegradable Plastics Host Distinct and Potentially More Hazardous Microbes When Compared to Both Natural Materials and Planktonic Community. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, F.; Österlund, T.; Boulund, F.; Marathe, N.P.; Larsson, D.G.J.; Kristiansson, E. Identification and Reconstruction of Novel Antibiotic Resistance Genes from Metagenomes. Microbiome 2019, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Cao, J.; Yu, J.; Jian, M.; Zou, L. Microplastics Exacerbate the Ecological Risk of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Wetland Ecosystem. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 372, 123359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Geng, J.; Sun, M.; Jiang, C.; Lin, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, Y. Distinct Species Turnover Patterns Shaped the Richness of Antibiotic Resistance Genes on Eight Different Microplastic Polymers. Environ. Res. 2024, 259, 119562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferheen, I.; Spurio, R.; Marcheggiani, S. Emerging Issues on Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Colonizing Plastic Waste in Aquatic Ecosystems. Antibiotics (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, R.; Wang, M.; Yuan, S.; Lu, G. Dynamic Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Plastisphere in the Vertical Profile of Urban Rivers. Water Res. 2024, 249, 120946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Ouyang, T.; Jiang, R.; Ma, J.; Lu, G.; Yuan, S.; Yan, Z. Reshaping the Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Plastisphere upon Deposition in Sediment-Water Interface: Dynamic Evolution and Propagation Mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, L.T.; Hien, V.T.T.; Tram, N.T.; Hieu, V.H.; Gutierrez, T.; Thi Thu Ha, H.; Dung, P.M.; Thi Thuy Huong, N. First Evidence of Microplastic-Associated Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL)-Producing Bacteria in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. J. Hazard. Mater. Lett. 2024, 5, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; Ouellette, M.; Outterson, K.; Patel, J.; Cavaleri, M.; Cox, E.M.; Houchens, C.R.; Grayson, M.L.; Hansen, P.; Singh, N.; Theuretzbacher, U.; Magrini, N.; Aboderin, A.O.; Al-Abri, S.S.; Awang Jalil, N.; Benzonana, N.; Bhattacharya, S.; Brink, A.J.; Burkert, F.R.; Cars, O.; Cornaglia, G.; Dyar, O.J.; Friedrich, A.W.; Gales, A.C.; Gandra, S.; Giske, C.G.; Goff, D.A.; Goossens, H.; Gottlieb, T.; Guzman Blanco, M.; Hryniewicz, W.; Kattula, D.; Jinks, T.; Kanj, S.S.; Kerr, L.; Kieny, M.-P.; Kim, Y.S.; Kozlov, R.S.; Labarca, J.; Laxminarayan, R.; Leder, K.; Leibovici, L.; Levy-Hara, G.; Littman, J.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Manchanda, V.; Moja, L.; Ndoye, B.; Pan, A.; Paterson, D.L.; Paul, M.; Qiu, H.; Ramon-Pardo, P.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Sanguinetti, M.; Sengupta, S.; Sharland, M.; Si-Mehand, M.; Silver, L.L.; Song, W.; Steinbakk, M.; Thomsen, J.; Thwaites, G.E.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; Van Kinh, N.; Vega, S.; Villegas, M.V.; Wechsler-Fördös, A.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Wesangula, E.; Woodford, N.; Yilmaz, F.O.; Zorzet, A. Discovery, Research, and Development of New Antibiotics: The WHO Priority List of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and Tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.-N.; Gaston, J.M.; Dai, C.L.; Zhao, S.; Poyet, M.; Groussin, M.; Yin, X.; Li, L.-G.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Topp, E.; Gillings, M.R.; Hanage, W.P.; Tiedje, J.M.; Moniz, K.; Alm, E.J.; Zhang, T. An Omics-Based Framework for Assessing the Health Risk of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Shi, J.; Wang, C.; Mai, W.; Li, G.; An, T. Selective Enrichment of High-Risk Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Priority Pathogens in Freshwater Plastisphere: Unique Role of Biodegradable Microplastics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 135901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Luo, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Chen, J.; Ren, P.; Tang, Y.; Suo, Z.; Chen, K. Potential Risk of Microplastics in Plateau Karst Lakes: Insights from Metagenomic Analysis. Environ. Res. 2025, 270, 120984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, J.; Hou, S.; Cao, H.; Liu, X.; Cai, W.; Zeng, Y.; Luo, X.; Tu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Chen, Z. Spread Performance and Underlying Mechanisms of Pathogenic Bacteria and Antibiotic Resistance Genes Adhered on Microplastics in the Sediments of Different Urban Water Bodies. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Fan, L.; Liang, B.; Guo, J.; Gao, S.-H. Determining Antimicrobial Resistance in the Plastisphere: Lower Risks of Nonbiodegradable vs Higher Risks of Biodegradable Microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 7722–7735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Lin, H.; Yang, Y. Microplastics Are a Hotspot for Antibiotic Resistance Genes: Progress and Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, C.; Han, W.; Gu, P.; Jing, R.; Yang, Q. Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Virulence Factors in the Plastisphere in Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluent: Health Risk Quantification and Driving Mechanism Interpretation. Water Res. 2025, 271, 122896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdogan, Z.; Guven, B. Microplastics in the Environment: A Critical Review of Current Understanding and Identification of Future Research Needs. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254 Pt A, 113011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, P.; Jia, H. Microplastics Exacerbated Conjugative Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes during Ultraviolet Disinfection: Highlighting Difference between Conventional and Biodegradable Ones. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, L.; Messer, L.F.; Ormsby, M.J.; White, H.L.; Fellows, R.; Quilliam, R.S. Exploiting Microplastics and the Plastisphere for the Surveillance of Human Pathogenic Bacteria Discharged into Surface Waters in Wastewater Effluent. Water Res. 2025, 281, 123563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, E.M.; Di Cesare, A.; Kettner, M.T.; Arias-Andres, M.; Fontaneto, D.; Grossart, H.-P.; Corno, G. Microplastics Increase Impact of Treated Wastewater on Freshwater Microbial Community. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 234, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Peng, C.; Dai, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiao, S.; Ma, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, L. Slower Antibiotics Degradation and Higher Resistance Genes Enrichment in Plastisphere. Water Res. 2022, 222, 118920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadjelovic, V.; Wright, R.J.; Borsetto, C.; Quartey, J.; Cairns, T.N.; Langille, M.G.I.; Wellington, E.M.H.; Christie-Oleza, J.A. Microbial Hitchhikers Harbouring Antimicrobial-Resistance Genes in the Riverine Plastisphere. Microbiome 2023, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perveen, S.; Pablos, C.; Reynolds, K.; Stanley, S.; Marugán, J. Growth and Prevalence of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in Microplastic Biofilm from Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluents. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856 Pt 2, 159024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.; Rodrigues, E.T.; Tacão, M.; Henriques, I. Microplastics Accumulate Priority Antibiotic-Resistant Pathogens: Evidence from the Riverine Plastisphere. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 332, 121995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.; Tacão, M.; Henriques, I. Wastewater Discharges and Polymer Type Modulate the Riverine Plastisphere and Set the Role of Microplastics as Vectors of Pathogens and Antibiotic Resistance. J. Water Proc.engineering 2025, 71, 107419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Campos, S.; González-Pleiter, M.; Rico, A.; Schell, T.; Vighi, M.; Fernández-Piñas, F.; Rosal, R.; Leganés, F. Time-Course Biofilm Formation and Presence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes on Everyday Plastic Items Deployed in River Waters. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443 Pt B, 130271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eytcheson, S.A.; Brown, S.A.; Wu, H.; Nietch, C.T.; Weaver, P.C.; Darling, J.A.; Pilgrim, E.M.; Purucker, S.T.; Molina, M. Assessment of Emerging Pathogens and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Biofilm of Microplastics Incubated under a Wastewater Discharge Simulation. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 27, e70103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, M.A.; Nomalihle, M.; Featherston, J.; Kumar, A.; Amoah, I.D.; Ismail, A.; Bux, F.; Kumari, S. Comprehensive Profiling and Risk Assessment of Antibiotic Resistomes in Surface Water and Plastisphere by Integrated Shotgun Metagenomics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 487, 137180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Fan, Y.; Qian, X.; Zhang, Y. Unraveling the Role of Microplastics in Antibiotic Resistance: Insights from Long-Read Metagenomics on ARG Mobility and Host Dynamics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 490, 137804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, N.; Qiu, J.; Ge, W.; Guo, X.; Zhu, D.; Wang, N.; Luo, Y. Fibrous and Fragmented Microplastics Discharged from Sewage Amplify Health Risks Associated with Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Aquatic Environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 15919–15930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Song, W.; Ye, C.; Lin, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, W. Plastics in the Marine Environment Are Reservoirs for Antibiotic and Metal Resistance Genes. Environ. Int. 2019, 123, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radisic, V.; Nimje, P.S.; Bienfait, A.M.; Marathe, N.P. Marine Plastics from Norwegian West Coast Carry Potentially Virulent Fish Pathogens and Opportunistic Human Pathogens Harboring New Variants of Antibiotic Resistance Genes. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucato, A.; Vecchioni, L.; Savoca, D.; Presentato, A.; Arculeo, M.; Alduina, R. A Comparative Analysis of Aquatic and Polyethylene-Associated Antibiotic-Resistant Microbiota in the Mediterranean Sea. Biology 2021, 10, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaanderen, E.J.; Ghaly, T.M.; Moore, L.R.; Focardi, A.; Paulsen, I.T.; Tetu, S.G. Plastic Leachate Exposure Drives Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence in Marine Bacterial Communities. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 327, 121558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; de Haan, W.P.; Cerdà-Domènech, M.; Méndez, J.; Lucena, F.; García-Aljaro, C.; Sanchez-Vidal, A.; Ballesté, E. Detection of Faecal Bacteria and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Biofilms Attached to Plastics from Human-Impacted Coastal Areas. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 319, 120983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yoo, K. Marine Plastisphere Selectively Enriches Microbial Assemblages and Antibiotic Resistance Genes during Long-Term Cultivation Periods. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 344, 123450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, A.; Sathicq, M.B.; Sbaffi, T.; Sabatino, R.; Manca, D.; Breider, F.; Coudret, S.; Pinnell, L.J.; Turner, J.W.; Corno, G. Parity in Bacterial Communities and Resistomes: Microplastic and Natural Organic Particles in the Tyrrhenian Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 203, 116495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sababadichetty, L.; Miltgen, G.; Vincent, B.; Guilhaumon, F.; Lenoble, V.; Thibault, M.; Bureau, S.; Tortosa, P.; Bouvier, T.; Jourand, P. Microplastics in the Insular Marine Environment of the Southwest Indian Ocean Carry a Microbiome Including Antimicrobial Resistant (AMR) Bacteria: A Case Study from Reunion Island. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 198, 115911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Tang, J.; Tang, K.; An, M.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Cao, X.; He, C. Selective Enrichment of Bacteria and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Microplastic Biofilms and Their Potential Hazards in Coral Reef Ecosystems. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, W.; Danioux, A.; Oueslati, A.; Santana-Rodríguez, J.J.; Sire, O.; Sedrati, M.; Ben Mansour, H. Dissemination of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Associated with Microplastics Collected from Monastir and Mahdia Coasts (Tunisia). Microb. Pathog. 2024, 198, 107193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, G.; Azzaro, M.; Dell’Acqua, O.; Papale, M.; Lo Giudice, A.; Laganà, P. Plastic Polymers and Antibiotic Resistance in an Antarctic Environment (Ross Sea): Are We Revealing the Tip of an Iceberg? Microorganisms 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghsodian, Z.; Sanati, A.M.; Ramavandi, B.; Ghasemi, A.; Sorial, G.A. Microplastics Accumulation in Sediments and Periophthalmus Waltoni Fish, Mangrove Forests in Southern Iran. Chemosphere 2021, 264 Pt 2, 128543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.; He, L.; Li, T.; Dai, Z.; Sun, S.; Ren, L.; Liang, Y.-Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C. Impact of the Surrounding Environment on Antibiotic Resistance Genes Carried by Microplastics in Mangroves. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 837, 155771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Li, T.; Qiu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Dai, Z.; Liao, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, S.; Li, C. Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes Carried by Plastic Waste from Mangrove Wetlands of the South China Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 161111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-Q.; Wang, W.-L.; Shen, Y.-J.; Su, J.-Q. Mangrove Plastisphere as a Hotspot for High-Risk Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Pathogens. Environ. Res. 2025, 274, 121282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.-P.; Sun, X.-L.; Chen, Y.-R.; Hou, L.; Liu, M.; Yang, Y. Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Biofilms on Plastic Wastes in an Estuarine Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 140916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, A.; Pinnell, L.J.; Brambilla, D.; Elli, G.; Sabatino, R.; Sathicq, M.B.; Corno, G.; O’Donnell, C.; Turner, J.W. Bioplastic Accumulates Antibiotic and Metal Resistance Genes in Coastal Marine Sediments. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Xu, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Q. Marine Microplastics Enrich Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs), Especially Extracellular ARGs: An Investigation in the East China Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 209 Pt B, 117260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Niu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R. Exploring the Dynamics of Antibiotic Resistome on Plastic Debris Traveling from the River to the Sea along a Representative Estuary Based on Field Sequential Transfer Incubations. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yashir, N.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ma, M.; Wang, D.; Feng, Y.; Song, X. Co-Occurrence of Microplastics, PFASs, Antibiotics, and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Groundwater and Their Composite Impacts on Indigenous Microbial Communities: A Field Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 961, 178373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guruge, K.S.; Goswami, P.; Kanda, K.; Abeynayaka, A.; Kumagai, M.; Watanabe, M.; Tamamura-Andoh, Y. Plastiome: Plastisphere-Enriched Mobile Resistome in Aquatic Environments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 471, 134353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Cao, S.; Wu, Q.; Xu, F.; Li, R.; Cui, L. Size Effects of Microplastics on Antibiotic Resistome and Core Microbiome in an Urban River. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Xu, F.; Xing, X.; Wei, J.; Chen, Q.-L.; Su, J.-Q.; Cui, L. Microplastics Pose an Elevated Antimicrobial Resistance Risk than Natural Surfaces via a Systematic Comparative Study of Surface Biofilms in Rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhu, L.; Cui, L.; Zhu, Y.-G. Viral Diversity and Potential Environmental Risk in Microplastic at Watershed Scale: Evidence from Metagenomic Analysis of Plastisphere. Environ. Int. 2022, 161, 107146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dong, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, B.; Ma, H.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Ran, S.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Y.; Li, J. Diversity and Functional Roles of Viral Communities in Gene Transfer and Antibiotic Resistance in Aquaculture Waters and Microplastic Biofilms. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 381, 126636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Yin, X.; Balcazar, J.L.; Huang, D.; Liao, J.; Wang, D.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Yu, P. Bacterium-Phage Symbiosis Facilitates the Enrichment of Bacterial Pathogens and Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in the Plastisphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 2948–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Presence of Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Food, with Particular Focus on Seafood. EFSA J. 2016, 14, e04501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, H.; Dutta, J.; Karnwal, A.; Kumar, G. Microplastic Contamination in Fish: A Systematic Global Review of Trends, Health Risks, and Implications for Consumer Safety. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 219, 118279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhou, W.; Tang, Y.; Shi, W.; Shao, Y.; Ren, P.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, G.; Sun, H.; Liu, G. Microplastics Aggravate the Bioaccumulation of Three Veterinary Antibiotics in the Thick Shell Mussel Mytilus Coruscus and Induce Synergistic Immunotoxic Effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 145273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Wang, R.; Yang, G.; Xie, S.; Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Huang, W.; Zhang, T.; Feng, Z. Pollution Concerns in Mariculture Water and Cultured Economical Bivalves: Occurrence of Microplastics under Different Aquaculture Modes. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 406, 136913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Xu, W.; Hu, X.; Xu, Y.; Wen, G.; Cao, Y. The Impact of Microplastics on Antibiotic Resistance Genes, Metal Resistance Genes, and Bacterial Community in Aquaculture Environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W.; Guo, L.; Huang, C.; Xie, B.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Liang, H. A Systematic Review of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs) in Mariculture Wastewater: Antibiotics Removal by Microalgal-Bacterial Symbiotic System (MBSS), ARGs Characterization on the Metagenomic. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 930, 172601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Du, H.; Huang, Y.; Yin, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Selective Adsorption of Antibiotics on Aged Microplastics Originating from Mariculture Benefits the Colonization of Opportunistic Pathogenic Bacteria. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Luo, Y. Effects of Microplastics on Distribution of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Recirculating Aquaculture System. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 184, 109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Luo, Y. Potential Risks of Microplastics Combined with Superbugs: Enrichment of Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria on the Surface of Microplastics in Mariculture System. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 187, 109852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, J. Metagenomic Analysis on Resistance Genes in Water and Microplastics from a Mariculture System. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Dai, W.; Pang, K.; Liu, Y.; Wu, R. Bacterial Community Succession and the Enrichment of Antibiotic Resistance Genes on Microplastics in an Oyster Farm. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 194 Pt A, 115402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, Q.; Wu, C. Microplastic and Antibiotic Proliferated the Colonization of Specific Bacteria and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Phycosphere of Chlorella Pyrenoidosa. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 455, 131618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naudet, J.; d’Orbcastel, E.R.; Bouvier, T.; Godreuil, S.; Dyall, S.; Bouvy, S.; Rieuvilleneuve, F.; Restrepo-Ortiz, C.X.; Bettarel, Y.; Auguet, J.-C. Identifying Macroplastic Pathobiomes and Antibiotic Resistance in a Subtropical Fish Farm. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 194 Pt B, 115267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Peng, L.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, N.; Li, S.; Feng, Y. Biodegradable Microplastics Amplify Antibiotic Resistance in Aquaculture: A Potential One Health Crisis from Environment to Seafood. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 498, 139932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Q.; Dong, S.; Wang, X.; Yan, C. Combined Effects of Micro-/Nano-Plastics and Oxytetracycline on the Intestinal Histopathology and Microbiome in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 843, 156917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lu, G.; Sun, Y.; Yan, Z.; Dang, T.; Liu, J. Metagenomic Analysis Explores the Interaction of Aged Microplastics and Roxithromycin on Gut Microbiota and Antibiotic Resistance Genes of Carassius Auratus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 127773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lu, G.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Yan, Z. Aged Microplastics Change the Toxicological Mechanism of Roxithromycin on Carassius Auratus: Size-Dependent Interaction and Potential Long-Term Effects. Environ. Int. 2022, 169, 107540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Lu, W.; Avellán-Llaguno, R.D.; Liao, X.; Ye, G.; Pan, Z.; Hu, A.; Huang, Q. Gut Microbiota Related Response of Oryzias Melastigma to Combined Exposure of Polystyrene Microplastics and Tetracycline. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Qiu, D.; Zhou, T.; Zeng, L.; Yan, C. Biofilm Enhances the Interactive Effects of Microplastics and Oxytetracycline on Zebrafish Intestine. Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 270, 106905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zeng, J.; Zheng, N.; Ge, C.; Li, Y.; Yao, H. Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics in the Aquatic Environment Enrich Potential Pathogenic Bacteria and Spread Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Fish Gut. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 475, 134817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, G.; Cortimiglia, C.; Belloso Daza, M.V.; Greco, E.; Bassi, D.; Cocconcelli, P.S. Microplastic-Mediated Transfer of Tetracycline Resistance: Unveiling the Role of Mussels in Marine Ecosystems. Antibiotics (Basel) 2024, 13, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; You, L.; Gin, K.Y.-H.; He, Y. Impact of Microplastics Pollution on Ciprofloxacin Bioaccumulation in the Edible Mussel (Perna Viridis): Implications for Human Gut Health Risks. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 36, 103860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Han, Y.; Tang, Y.; Shi, W.; Du, X.; Sun, S.; Liu, G. Microplastics Aggravate the Bioaccumulation of Two Waterborne Veterinary Antibiotics in an Edible Bivalve Species: Potential Mechanisms and Implications for Human Health. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 8115–8122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Lv, C.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wang, S.; Li, R.; Chen, K.; Zhu, F.; Wang, D.; Qiu, Z.; Ding, C. Promotion of Microplastic Degradation on the Conjugative Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Gut of Macrobenthic Invertebrates. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 293, 117999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Li, B.; Dong, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, H.; Ye, Y.; Ma, H.; Ran, S.; Li, J. Impact of Microplastics Exposure on the Reconfiguration of Viral Community Structure and Disruption of Ecological Functions in the Digestive Gland of Mytilus Coruscus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Qian, J.; Wang, W.; Xie, M.; Tan, Q.-G.; Chen, R. Effects of Aged Microplastics on the Abundance of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Oysters and Their Excreta. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 210, 107284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lu, G.; Sun, Y.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J. Effect of Microplastics on Oxytetracycline Trophic Transfer: Immune, Gut Microbiota and Antibiotic Resistance Gene Responses. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 470, 134147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitiot, A.; Rolin, C.; Seguin-Devaux, C.; Zimmer, J. Fighting Antibiotic Resistance: Insights into Human Barriers and New Opportunities: Antibiotic Resistance Constantly Rises with the Development of Human Activities. We Discuss Barriers and Opportunities to Get It under Control: Antibiotic Resistance Constantly Rises with the Development of Human Activities. We Discuss Barriers and Opportunities to Get It under Control. Bioessays 2025, 47, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husna, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Badruzzaman, A.T.M.; Sikder, M.H.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.T.; Alam, J.; Ashour, H.M. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases (ESBL): Challenges and Opportunities. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cui, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, H.; Song, M.; Wu, H.; Hu, Z.; Liang, S.; Zhang, J. The Critical Role of Microplastics in the Fate and Transformation of Sulfamethoxazole and Antibiotic Resistance Genes within Vertical Subsurface-Flow Constructed Wetlands. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shen, M.; Li, M.; Tao, S.; Li, T.; Yang, Z. Removal of Microplastics and Resistance Genes in Livestock and Aquaculture Wastewater: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewińska, P.; Wojnarowski, K.; Szeligowska, N.; Pokorny, P.; Hussein, W.; Hasegawa, Y.; Dobicki, W.; Palić, D. Presence of Microplastic Particles Increased Abundance of Pathogens and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Microbial Communities from the Oder River Water and Sediment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Plastic polymer | Site | Bacterial host | ARG | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBAT, PET |

microcosm |

Afipia, Rhizobiaceae | qnrS | [39] |

| Bacillus spp. | sul2, blaQ | |||

|

Gemmobacter, Conexibacter, Lamia |

tetA, tetC, tetX, ereB | |||

| PE, PP, PBD | Ganjiang river (China) | Streptococcus mitis | ermF, ermB | [44] |

| Mixed polymers | Huangpu River (China) | Afipia spp. | aac(2′)-I, arr, cat, mexI, blaTEM-1, tetV | [45] |

| PVC, PLA | freshwater microcosm with tetracycline |

Pseudomonas spp., Flavobacteriaceae, Actinobacteria |

tetA, tetC, tetM, and tetX | [21] |

| PET, PVC | freshwater microcosm with tetracycline | Genera Pseudomonas, Solobacterium, Achromobacter, Aeromonas, Beggiatoa, Propionivibrio, and Paludibacter |

tetA, tetC, sul1, tetO | [48] |

| Mixed polymers | Haihe River (China) | Enterobacter cloacae | tetG | [49] |

| APSs | Bracciano Lake (Italy) | Morganella morganii | tetC, sul1, sul3, cmlA1, cmxA, blaCTX-M-01, blaCTX-M-02 | [51] |

| Mixed polymers | Mondego river (Portugal) |

E. coli, Citrobacter spp., Enterobacter spp., Klebsiella pneumonia, Shigella spp. |

aacA4-cr, qnrS, qnrB, qnrVC, blaCTX-M, blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-32, blaCTX-M-55 | [77] |

| PE, PP | Poyang Lake (China) | A. veronii | blaOXA-12, cphA6, cphA8, cphA3 | [23] |

| Arthrobacter spp. | mdsB, novA, rphA, emrK | |||

| BDPs | Lakes in Wuhan (China) | Riemerella anatipestifer | novA, macB, mdsB, sav1866, taeA, arnC, mfd | [57] |

| Vibrio campbellii | novA, blaCRP, taeA, pmrE, tet4 | |||

| V. cholerae | pbp1a, murA, efrA, mtrA, tetPB | |||

| Mixed polymers |

Lake water |

Lysinibacillus spp., Exiguobacterium acetylicum, K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, K. michiganensis |

blaTEM (shared by all bacteria), blaSHV, adeA, tetA, acrB, sul1, mecA, tetW, acrF, cmxA, sul2 | [58] |

| Mixed polymers |

Red River (Vietnam) | Aeromonas spp. | blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTXM | [61] |

| PHA | Central Lake (China) | Proteobacteria | bacA, mecA, qacA, tolC, dfrA1, mphA, mphB | [64] |

| Mixed polymers | treated wastewater microcosm | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | sul1 | [80] |

| PET, PLA | Treated wastewater | Candidatus Microthrix | tetA48, kdpE, rpoB2 | [69] |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 44 ARGs including aadA, ksgA, aph(3′)-I | |||

| Mixed polymers | Jiuxiang River and Taihu Lake (China) |

Variovorax, Rubrivivax, Thauera |

ARGs for tetracycline | [71] |

|

Herbaspyrillum, Limnohabitans |

ARGs for MLS, elfamycin and tetracyclines | |||

| Not specified |

Urban lake in Chengdu (China) | Gammaproteobacteria, Pseudomonadota, Acidobacteriota, Actinomycetota | bacA, sul1 | [66] |

| Urban river trait Chengdu (China) | Deltaproteobacteria, Desulfobacterales | sul1, sul2, acrB, ant(2″)-Ia | ||

| Rural lake Chengdu (China) | Gammaproteobacteria | sul 1, sul 2, smeE | ||

| Not specified |

Yangtze river (China) | genera CAMDGX01, PHCI01, Shewanella |

bacA, novA, mexF, mcr-4,3, blaOXA-541 |

[83] |

| genera Pseudomonas, Serratia |

bacA, arnA, mexB, muxB, aac(6’)-Ic, acrD |

| Plastic polymer | Site | Bacterial host | ARG | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed polymers | Vestland county, Norway | A. salmonicida, M. morganii, A. beijerinckii | class C beta-lactamases, catB | [85] |

| A. salmonicida | cphA | |||

| Aeromonas spp. | qnrA | |||

| A. beijerinckii | class A beta-lactamase, aminoglycoside acetyltransferase, cat |

|||

| PBAT, PET | microcosm |

Labrenzia, Vicinamibacteraceae |

tetA, blaQ | [39] |

| PBAT, PET | microcosm |

Labrenzia, Vicinamibacteraceae, Acidobacteriota, Coxiella, Croceibacter, Tumebacillus |

qnrB | |

| Not specified among PE, PP, PS and PVC | Busan City (South Korea) | Coxiella spp. | tetA | [89] |

| Pseudahrensia spp. | tetQ | |||

| Genera Fuerstia, Methylotenera, Halioglobus, Ahrensia, Rubritalea, Algibacter |

ermB | |||

| Mixed polymers | Tyrrhenian Sea (Italy) | Rhizobiales | bacA | [90] |

| Photobacterium spp. | tolC, acrB, tet34 | |||

| Pleurocapsa spp. | vatF | |||

| PET | Coral reef, Hainan (China) | Nine bacterial genera | sul2 | [92] |

| Vibrio spp. | sul1 | |||

| Mixed polymers | Monastir, Mahdia (Tunisia) |

Shewanella arctica | blaTEM | [93] |

| Plastic polymer | Site | Bacterial host | ARG | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed polymers | Laguna Madre (Mexico) | Bacillus cereus | ARGs for 10 antibiotic classes | [100] |

| B. thuringiensis | ARGs for 20 antibiotic classes | |||

| Mixed polymers | Yangtze, Sheyang, Guanhe and Xinyi rivers (China) | Proteobacteria | blaNDM-1, tetA, tetX, sul1, sul2 | [101] |

| Bacteroidota | blaTEM, ermB, ereA, tetX, sul1 | |||

| Mixed polymers | Tokyo, Saitama, Chiba (Japan) | Genera Citrobacter, Aeromonas, Sulfitobacter, Lacinutrix | bacA, acrAB-TolC, mutated marR, acrAB inducer marA, vanG, adeF, qacG, vanH | [104] |

| K. pneumoniae | kpnF |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).