Introduction

Adipose mesenchymal stem cells are located in the hypodermis, and reticular dermis within the so-called dermal white adipose tissue (Driskell et al, 2014; Li et al, 2024) and release hundreds of types of molecules, including proteins, possibly microproteins (Bonilauri et al, 2021), peptides, noncoding RNA (the best evidence indicates mRNA and DNA are not present in the secretome), and lipids, that target multiple pathways when simultaneously released from the stem cell. To be clear, peptides are fundamentally different from microproteins in that they are synthesized as larger precursor protein molecules and are post-translationally processed and cleaved by proteases to generate their active peptide product. Microproteins are different, being made by short open reading frames (sORFs). All of these molecule types can potentially work synergistically at the same target, in time and in space, especially when the molecule types are packaged together into an exosome that brings a collection of molecules to the target at the same time, thus producing a systems-level effect (Maguire, 2014; Maguire, 2019). Alaniz et al (2023) have found the set of molecules present in ADSC secretome is consistent across donors. Thus this systems-level therapeutic effect can be achieved with ADSC secretome from all donor tissue, another hallmark in the superiority of ADSC over other stem cell types for therapeutic development (Zhang et al, 2020; Dong et al, 2023; Suchanecka et al, 2025).

2. Non-Reductionist Strategy of Therapeutic Development

In Goodman and Gilman's, “The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics,” we were all taught to search for the one molecule that targets a single pathway, and specifically targets only that one pathway, as the causal pathway underlying a disease or condition, and to optimally develop a therapeutic. However, diseases involve multiple pathways, often acting at proteins, including, for example, suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins (Cianciulli et al, 2024). For example, in psoriasis and eczema, the SOCS protein pathways are dysregulated such that these proteins no longer down regulate T-cell mediated inflammation. Diseases are little affected by genetics (Rappaport, 2016), rather are primarily a function of the exposome (Rappaport et al, 2014). For example, skin diseases result from perturbations in multiple pathways, not just one (Dong et al, 2024), and evidence suggests that psoriasis and atopic dermatitis are triggered by multiple environmental toxins (Kim, 2015), allergens (Venter et al, 2024), and pathogens (Wang et al, 2021), acting on multiple pathways. Therefore, optimal development of a therapeutic must act on those multiple pathways underlying the disease or condition, not just partially correct the underlying mechanisms of the condition by acting at only one pathway. In psoriasis and eczema, for example, a therapeutic using multiple molecules, the secretome from adipose mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs), can regulate SOCS pathways, and modulate JAK pathways to reduce inflammation (Wang et al, 2022; Ko et al, 2023). Further, the secretome from ADSCs increases SOCS3 expression and, thus, the persistent and uninhibited expression of STAT3, an anti-inflammatory STAT pathway (Murray, 2006). Increased SOCS3 effectively ameliorates tissue injury by promoting tissue regeneration and decreasing inflammation and apoptosis (Lee et al, 2016).

3. Diseases Arise from Environmental Perturbations

Diseases resulting from environmental conditions, rather than genetics, bode well for preventing and treating diseases. Genetic diseases are treated by expensive and risky gene editing procedures that rarely work well, such as in sickle cell anemia (Dovern et al, 2023; Ledford, 2024)) or merely treating the genetic disease’s symptoms, while environmental diseases can be prevented or treated by changing the person’s environment and restoring the patient’s physiology to normal. Ever since endosymbiosis and the development of mitochondria (Sagan, 1967), the complexity of cells and their interactions with one another to evolve complex vertebrates, multicellular organisms depend on a large collection of external molecules to maintain their normal function. Life does not work by genetic determinism (Noble and Noble, 2023; Ball, 2023), this notion now being unraveled by epigenetics (Lerner and Overton, 2017). Twenty-first-century biology rejects genetic determinism (Jamieson and Radick, 2017), yet it is how most people think and many physicians (Lane et al, 2023) think that life works. Indeed, conventional genome-wide association studies (GWAS) often overlook flexible and contextually responsive regulatory networks that coact with genetic and epigenetic factors, particularly in humans where controlling environmental variables is not possible. Genes influencing phenotypes operate within gene regulatory networks that respond flexibly, contextually, and stochastically, not deterministically given current methodologies for measurement that preclude knowing and measuring every relevant variable. For example, there are trillions of cells in the human body (Hatton et al, 2023) and billions of different types of proteins (Aebersold et al, 2018), each of which is highly regulated by the environment and may influence the phenotype to be measured. However, most genome-wide association studies (GWAS) describing phenotypes are not constructed to capture this complexity and dynamism. GWAS has been more successful when it is possible to precisely control the environment, as is often accomplished in plant and animal sciences. GWAS in humans is especially challenging for the study of phenotypes because of the lack of control scientists have over both the defined population and their environment. Although behavioral geneticists are aware of the importance of environmental influences on behavior and generally include caveats against overly genetically deterministic interpretations of their work, these caveats are often overlooked (Robinson et al, 2024).

4. Systems Therapeutics

Instead we need a much more complete and integrative model of how life works, remembering that endosymbiosis brought us the mitochondria, “the CEO of the cell” (Lee-Glover et al, 2025). Mitochondria are the most dynamic organelles within a cell undergoing physiological homoeostasis, maintaining a healthy mitochondrial population and controlling many processes in the cell (Zhang et al, 2023). For example, environmental influences, such as stress, can lead to nuclear mitochondrial insertions that change somatic DNA, including in the germline, that can lead to cellular dysfunction, including in fibroblasts (Zhou et al, 2024). This includes biogenesis, fission, fusion and mitophagy which are synergistically regulated. This is relevant to ADSCs given they are able to donate their mitochondria to the benefit of target cells (Mei et al, 2025). In this alternate model we characterize patterns of information that are carried and are transferred not just with molecules but with complex structures and resulting fields, and high dimensional rapidly changing environments (Murugan et al, 2021). Biology can be viewed as a quantum collective process within a structurally complex system, where quantum phenomena, such as coherence and collective phenomenon (Goldenfeld and Woese, 2011), play a crucial role in determining the state of an organism. The point is, life is not determined just by DNA, rather it’s a collective process involving the many chemical and structural facets of the organism and its environment that determine life. This is true for heredity too, where epigenetics (Svorcova, 2023), protein heredity (mitotic and meiotic progeny; Harvey et al, 2017), and cell structure heredity (Beisson, 2008) all contribute to the process, all of which are influenced by the environment.

I argue for a systems therapeutic approach (Maguire, 2014), acting at the multiple pathways underlying the disease or condition, that renormalizes the physiology (Maguire, 2020) of the skin as a safe and efficacious means for preventative and therapeutic strategies in skin disorders. This is where the systems therapeutic normalizes physiology and anatomy, something characteristic of the S2RM technology (Maguire, 2017; Traub et al, 2021) that I address. What I offer is a basic approach that is safe using natural and/or non-destructive means to renormalize physiology (e.g. Maguire and Friedman, 2020), and can be utilized for numerous tissues other than the skin, including the epithelial tissues such as the respiratory tract (Maguire, 2021), skin (Traub et al, 2021), the immune system (Maguire, 2021) and nervous system (Maguire, et al, 2019), including in the development of vaccines (Maguire, 2022). In the specific approach I offer here using the molecules released (secretome) from adipose mesenchymal stem cells, the methodology simply returns to the skin those molecules that were present when the skin was young and healthy.

Others, Drs. Allison and Honjo, have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for a similar approach (Huang and Chang, 2019). The new cancer therapeutics, called checkpoint inhibitors, use a similar “systems therapeutic for physiological renormalization” strategy where T-cells are returned to their normal physiological state so that they can attack and destroy cancer cells (Sanders, 2018) and are more efficacious when combined with polyphenolic compounds and low protein diets (Golonko et al, 2024).

More recently Umeda et al (2024) argued for this approach when treating Alzheimer’s. For example, Umeda et al (2024) argue that “These results support our previous hypothesis that hot water extraction cannot necessarily recover all active ingredients of medicinal herbs, rather, some functional components will be lost during the process. Identifying true active ingredients would be useful not only for the development of functional foods but also for that of pharmaceuticals to prevent neurodegenerative diseases.” They found that a simple crush as opposed to an extraction process, provided significantly more benefit and acted at more pathways to ameliorate neurodegeneration in a mouse model.

5. Physiological Renormalization Using Systems Therapeutics

To institute physiological renormalization of the skin using systems therapeutics means to return perturbed skin physiology to its normal state. This may include, for example, stem cell released molecules from skin derived stem cells, the three lipid types (Ceramide, free fatty acids, and cholesterol) found in the epidermis (Zhang et al, 2025), and the microbiota needed to restore the natural microbiome of the skin to regulate inflammation and barrier function (Uberoi et al, 2021; Yu and Yao, 2024). The system effect is profound in the skin, where, for example, the survival of microbes does not depend solely on the needs of individual microbes but on a hidden web of relationships that can be caused to collapse by even small structural or physiological changes, such as a small change in metabolites upon which certain bacteria feed (Clegg and Gross, 2025). Once again, we describe a collective phenomenon. A rich diversity of microbiota constitutes a healthy microbiome that supports the skin’s physiology and anatomy (Roux et al, 2022), including the skin’s microbiome supporting skin stem cells (Cha et al, 2025).

6. A Paradigm Shift: Inflammation Not Needed for Wound Healing

The innate and adaptive immune systems are activated when the skin is wounded. Through evolution, the skin developed inflammation whenever wounded to fight the often present associated infection. Inflammation fights infection, but isn’t required for wound healing. Just the opposite is true – inflammation impedes wound healing. Chronic inflammation, as occurs in diabetic ulcers, impedes wound healing and yields wounds that can remain open for years. Key to wound healing is the extracellular matrix (ECM) and the cells that produce the ECM (Gomes et al, 2025), yielding no inflammation and scarless wound healing (Larson et al, 2010).

7. Teleology of Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Skin

As Galera et al (2024) have written, “AD-MSCs are a superior mesenchymal stromal cell source compared to bone marrow derived stromal cells (BM-MSCs) for several reasons.” Li et al (2015) have stated, “Adipose tissue-derived MSCs have biological advantages in the proliferative capacity, secreted proteins (basic fibroblast growth factor, interferon-γ, and insulin-like growth factor-1), and immunomodulatory effects.” Let’s consider, in greater detail, why ADSCs are superior to BMSCs for developing skin therapeutics.

Scientists think teleologically, often. It’s one of the ways we reason through the discovery, invention, and conceptualization of phenomenon (Perez-Escobar, 2024). Teleology is relating to or involving the explanation of phenomena in terms of the purpose they serve rather than of the cause by which they arise. In other words, teleology or finality is a branch of causality giving the reason or an explanation for something as a function of its end, its purpose, or its goal, as opposed to as a function of its cause. Why is this thing present, what is it doing? For example, Leibniz teleologically reasoned that the trajectories of rays of light were such for them to reach their end point by the easiest path (McDonough, 2009).

Adipose mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) remain multipotent in adults, even when harvested from adults they can transdifferentiate into neural lineage cells (Harley-Troxell et al, 2024) and have evolved to arise in the skin during the third trimester of fetal development and to be present throughout adult life. So ADSCs remain in the adult skin in a “perinatal state” having not differentiated into an adult state. These cells arise just before birth. So the teleological questions are, why do they arise just before birth, and what are the doing in the adult skin during a person’s lifetime?

The short answer is that ADSCs evolved to remain in the skin as a primordial cell that is specialized to reduce inflammation and to bias the skin towards a pro regenerative state where skin tissue is maintained and healed without scarring. For example, in wounded skin, platelets and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells perfuse the area of injury from the blood supply to fight infection by increasing inflammation and close the wound by inducing a high degree of proliferation. The ADSCs evolved to control this inflammatory process, and switch the immune system to an anti-inflammatory, regenerative state. One important factor secreted by ADSCs is TGF-β3 (Miao et al, 2025), which facilitates scarless wound healing (Wang et al, 2024). The three TGF-β isoforms are encoded by three different genes and exhibit different effects, but their family of mature ligands show strong conservation of amino acid sequences (Deng et al, 2024).

8. Bone Marrow (Adipose) Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Like adipose mesenchymal stem cells, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells reside in adipose tissue. The adipose tissue in bone marrow by early adulthood is 40% of total marrow tissue, which appears yellow due to the carotenoid in fat droplets. Red-to-yellow marrow conversion is normal, during which the fat content of bone marrow increases from 40% to 80% and vascularization decreases (Guillerman, 2013). The regional proximity of BMSCs and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) allows for their bidirectional communication in normal and obese states. The HSCs convey inflammation to MSCs to influence pro-adipogenic lineage determination with obesity, and BMSCs directly and indirectly home and maintain senescence of HSCs, which is disrupted in obese states (Boroumand et al, 2020). In other words, BMSCs acquire an inflammatory phenotype through conditioning by inflammatory HSCs. Further, BMSCs are a very heterogenous class of stem cells, the identify of which is difficult to discern (Woods and Guezguez, 2021).

Moreover, bone marrow is a preferred site for disseminated tumor cells and is considered to be a ‘metastatic niche’ (Shiozawa et al, 2015). The tumor cells that disseminate to bone marrow can then fuse with BMSCs and convert the BMSC to an oncogenic phenotype (Wang et al, 2018). Likewise, exosomes released from disseminated tumor cells can condition BMSCs in the bone marrow to become oncogenic (Xu et al, 2022), with the cancerous types hard to discern from normal types. Thus, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from donor tissue my be oncogenic, and so too may their secretome, something that does not bode well for therapeutic development (see Maguire, 2019).

9. Safety and Efficacy: Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cell (ADSC) Secretome Is Superior to Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell (BMSC) and Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell (UCSC) Secretomes

Listing Efficacy of ADSCs Versus BMSCs Versus UCMSCs

First,

Table 1 is a concise list of ADSC advantages over BMSCs and UMSCs. I’ll explain in more detail below the table, and go over the components of the secretome, both the exosomes and soluble fraction, something that is often overlooked given the current hype about exosomes.

| Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs), and the molecules they release, prolong and enhance inflammation by increasing survival and function of neutrophils (Casatella et al, 2011; Liang et al, 2024). BMSC secretome also reprograms hematopoietic stem cells to become inflammatory white blood cells (Ng et al, 2023). Under hypoxic conditions, which induces the activation of TRL4, BMSCs secrete pro-inflammatory factors and decrease the polarization of macrophages from the M1 to M2 phenotype, the M2 type being anti-inflammatory and therefore the BMSCs are promoting more inflammation (Faulknor et al, 2017; Waterman et al, 2010). Thus, BMSCs cultured in normal hypoxic conditions in the laboratory are secreting pro-inflammatory factors and when administered to wounded skin will induce inflammation by recruiting neutrophils and M1 type pro-inflammatory macrophages. |

| ADSCs have consistently exhibited much greater anti-inflammatory capabilities, phagocytic activity, anti-apoptotic capability activity and cell viability over BMSCs (Li et al, 2019). |

| ADSCs have been found to be highly immunomodulating cells, exceeding the suppressive effect of BMSCs by secreting more anti-inflammatory IL-6 and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) Ceccarelli et al (2020). |

| When compared with the BMSCs- and UCSCs-treated groups, the ADSCs-treated group exhibited markedly accelerated healing efficiency, characterized by increased wound closure rates, enhanced angiogenesis, and collagen deposition at the wound site in an animal model (Cao et al, 2024). |

| ADSCs have biological advantages over BMSCs in the proliferative capacity, secreted proteins (basic fibroblast growth factor, interferon-γ, and insulin-like growth factor-1), and immunomodulatory, ant-inflammatory effects (Li et al, 2015). |

| Differences in cytokine secretion cause ADSCs to have more potent immunomodulatory effects than BMSCs (Melief et al, 2013) |

| ADSCs are better at preventing fibrosis than BMSCs (Yoshida et al, 2023). |

| Adipose mesenchymal stem cell secretome is superior to that of BMSCs because it preferentially helps to rebuild the epidermis by stimulating basal keratinocytes (Ademi et al, 2023). |

| BMSCs express much CTHRC1 protein (Turlo et al, 2023), which may help to promote fibrosis (Liu et al, 2023). |

| ADSC exosomes contain SIRT1 (Huang et al, 2020) and activate SIRT1 in other cells (Liu et al, 2021) to reduce inflammation, improve mitochondrial function, and reduce senescence. |

| ADSC exosomes reduce inflammation in endothelial cells (Heo and Kim, 2022). |

| ADSCs are considered more powerful suppressors of immune response than mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from different tissue sources, including trabecular bone, bone marrow, dental pulp, and umbilical cord (Ribeiro et al., 2013; Nancarrow-Lei et al., 2017). |

| ADSCs immunomodulatory effects exceed that of BMSCs (Melief et al., 2013). |

| ADSCs secrete higher amount of immune suppressive cytokines, such as IL-6 and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) than do BMSCs (Soleymaninejadian et al., 2012; Melief et al., 2013; Montespan et al., 2014). |

| Bochev et al (2008) showed that ADSCs had a stronger ability to inhibit immunoglobulin (Ig) production by B cells than BMSCs. |

| Ivanova-Todorova E et al (2009) found that Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells are more potent suppressors of the adaptive immune response through limiting dendritic cells differentiation compared to bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. |

| ADSC secretome inhibits LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokines (Li et al, 2018) |

| Human ADSCs are key regulators of immune tolerance, with the capacity to suppress T cell and inflammatory responses and to induce the generation/activation of antigen-specific regulatory T cells (Gonzalez-Rey et al, 2010). |

| ADSC secretome can suppress the activation, proliferation, and function of CD8+ T cells, which are inflammatory killer T cells (Kuca-Warnawin et al, 2020). |

| ADSC secretome was able to elevate expression of M2 macrophages and modified their cytokine expression to an anti-inflammatory profile (Hu et al, 2016; Zomer et al, 2020) |

| Exosomes secreted by human adipose mesenchymal stem cells promote scarless cutaneous repair by regulating extracellular matrix remodeling (Wang et al, 2017). |

| ADSC exosomes reduce inflammation and alleviate keloids by promoting mitochondrial autophagy through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (Liu et al, 2024). |

| ADSC exosomes reduce injury through the transfer of mitochondria components to neighboring cells (Xia et al, 2022). |

| ADSC secretome expedited wound healing and reduced inflammation in an animal model (Ma et al, 2021). |

| ADSC secretome promotes wound healing without leaving visible scars and was found safe when injected (An et al, 2021). |

| ADSC secretome has positive effects on granulation tissue formation and vascularization, and helps prevent fibrosis in pressure ulcers (Alexandrushkina et al, 2020). |

| Human ADSCs secrete functional neprilysin-bound exosomes that can degrade β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) that is found in the skin - cutaneous amyloidosis (Katsuda et al, 2013; Kucheryavykh et al, 2018). |

| In psoriasis and eczema the secretome from adipose mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs), can regulate SOCS (suppressor of cytokine signaling) pathways, and modulate JAK pathways to reduce inflammation (Wang et al, 2022; Ko et al, 2023). Further, the secretome from ADSCs increases SOCS3 expression and, thus, the persistent and uninhibited expression of STAT3 by increased SOCS3 effectively ameliorates tissue injury by promoting tissue regeneration and decreasing inflammation and apoptosis (Lee et al, 2016). |

| ADSC and BMSC secretomes were characterized by the upregulation of proteins linked to ECM structure and organization and proteolytic processes compared to UCSCs, important to active involvement in tissue repair and microenvironment maintenance and suggesting their advantage for tissue-forming applications (Hodgson-Garms et al, 2025), but ADSCs are better at preventing fibrosis and reducing inflammation (Yoshida et al, 2023). |

| Fu et al (2025) found that hADSC-Exos are more effective in promoting hair follicle development compared to hUCMSC-Exos, and the secretome of ADSCs was more associated with growth processes such as nucleosome function than was the UCMSC secretome (Fu et al, 2025). |

10. Soluble Fraction is Important Part of Secretome in Addition to Exosomes

Soluble fraction of the ADSC secretome is key to anti-inflammatory effects – exosomes alone will not achieve optimal results in reducing inflammation (Carceller et al, 2021; González-Cubero et al, 2022). The soluble fraction in some studies has been found more powerful for immune modulation than the associated exosomes (Papait et al, 2022).

The combination of the soluble fraction and exosome fraction of the secretome from adipose mesenchymal stem cells is better at reducing inflammation, wound healing, and preventing fibrotic scarring than either of the two alone (Michel et al, 2019).

ADSC secretome enhanced the proliferative and migratory abilities of various cellular components of the dermis, such as dermal fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and endothelial cells, in vitro by activating PI3K/Akt and FAK-ERK1/2 signaling (Park et al, 2017)

ADSCs may induce proliferation of a subset of CD5 + regulatory B cells that secrete immunosuppressive IL-10. This cytokine inhibits the production of other inflammatory cytokines by activated T cells and could be relevant in the therapeutic treatment of autoimmune diseases (Kalampokis et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2015).

11. Most Proteins in Secretome are Secretory, Not in Exosome or Ectosome

In ADSC secretome, 75% of the proteins identified were predicted as secretory; of these, 57% were predicted to contain signal peptides and were thus secreted through the classical secretory pathway (Shin et al, 2021). In other words, the use of isolated exosomes for therapeutic development will exclude 75% of the proteins found in the whole secretome of ADSCs.

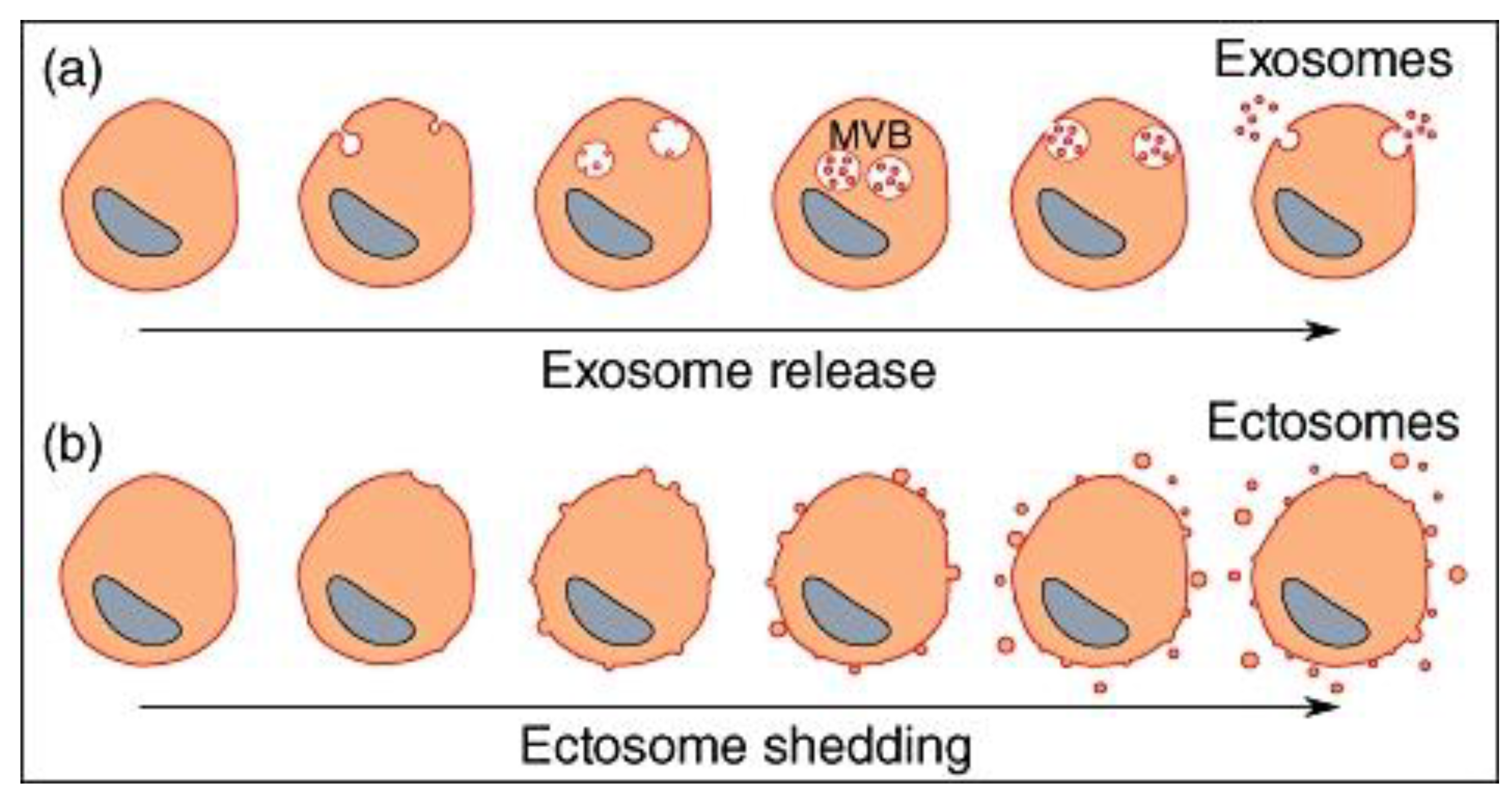

Considering different types of vesicles released from cells, whereas their formation, release, size, and biological function may be different, one common point between all vesicles that are released is that they bud from a membrane, whether this occurs at the cell surface or in a vesicular compartment inside the cell. Exosomes and ectosomes are microvesicles budding from a membrane. Exosomes are produced by inward budding into the late endosomal compartment, called multi-vesicular bodies (MVB). When MVB fuse with the cell membrane, exosomes are released as preformed vesicles. Ectosomes are small membrane vesicles shed by many cells by budding directly from the cell membrane.

12. Exosomes

Upon his discovery of extracellular vesicles being “exfoliated” from cells (MacDonald and Salem, 2023), Dr. Eberhard Trams, Ph.D., first coined the term exosome in 1981 (Trams et al, 1981). Exosomes are a thermodynamically favorable configuration of lipids in a solution, forming a very stable lipid bilayer structured vesicle of about 50-80nm in diameter. These are very flexible structures, that can squeeze through narrow openings but are resistant to damage unless encountering high shear forces (Maguire, 2016). ADSC-derived EVs, including exosomes, carry proteins, microRNAs (such as miR-21 and miR-26), and other signaling molecules that enhance collagen synthesis. These EVs have been shown to increase the production of type I and III collagen in wound healing models (Hu et al, 2016), and facilitate antifibrotic, scarless wound healing (Wang et al, 2017).

Exosomes are released from most cells, both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, including plants and animals. Some of the RNA are small, non-coding RNA that have been glycolated, called glycoRNA (Disney, 2021), RNA that have been glycolated and thus sorted for exosomal inclusion (Sharma et al, 2025). One study (Femminò et al, 2019) found mRNA in ADSC exosomes using RT-PCR; however, RT-PCR techniques are notorious for false positive (Li et al, 2022), so we must use caution in interpreting the results of one study. For example, Mitchel et al (2019) looked very carefully at RNA in ADSCs using PicoRNA chips and identified the presence of small RNAs with no molecules larger than 30 nucleotides, suggesting that the RNA components are exclusively miRNAs. Further, there is no evidence that exosomes from ADSCs contain DNA. Clearly, non-coding RNA, such as circRNA (Cao et al, 2022), are present in ADSC exosomes, but the presence of mRNA and DNA has not been established.

In a recent study by Kim et al (2017), the application of exosomes, derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC-Exos) obtained from human umbilical cord blood, on the skin were found to penetrate the stratum corneum and induce collagen formation in the dermis. Studies of the topical application of exosomes and their penetration into the skin are difficult, and while many review studies have been performed, more experimental data is needed to understand under what conditions exosomes best penetrate the skin.

13. Ectosomes

Ectosomes originate from the plasma membrane by outward budding, while exosomes are formed inside the cell from late endosomes called multivesicular bodies (MVBs) that then fuse with the plasma membrane for release. This difference in origin—directly from the cell surface for ectosomes versus through an internal, endosomal pathway for exosomes—is the key distinction between them (Sadallah et al, 2011). The major characteristics of ectosomes released by various cells are the expression of phosphatidylserine and to have anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive activities similarly to apoptotic cells. Ectosomes are larger than exosomes, and very large ectosomes have been called blebbisomes and can contain organelles, such as mitochondria. Both exosomes and ectosomes derived from adipose-derived stromal cells to promote tissue regeneration and reduction of inflammation (Xu et al, 2024).

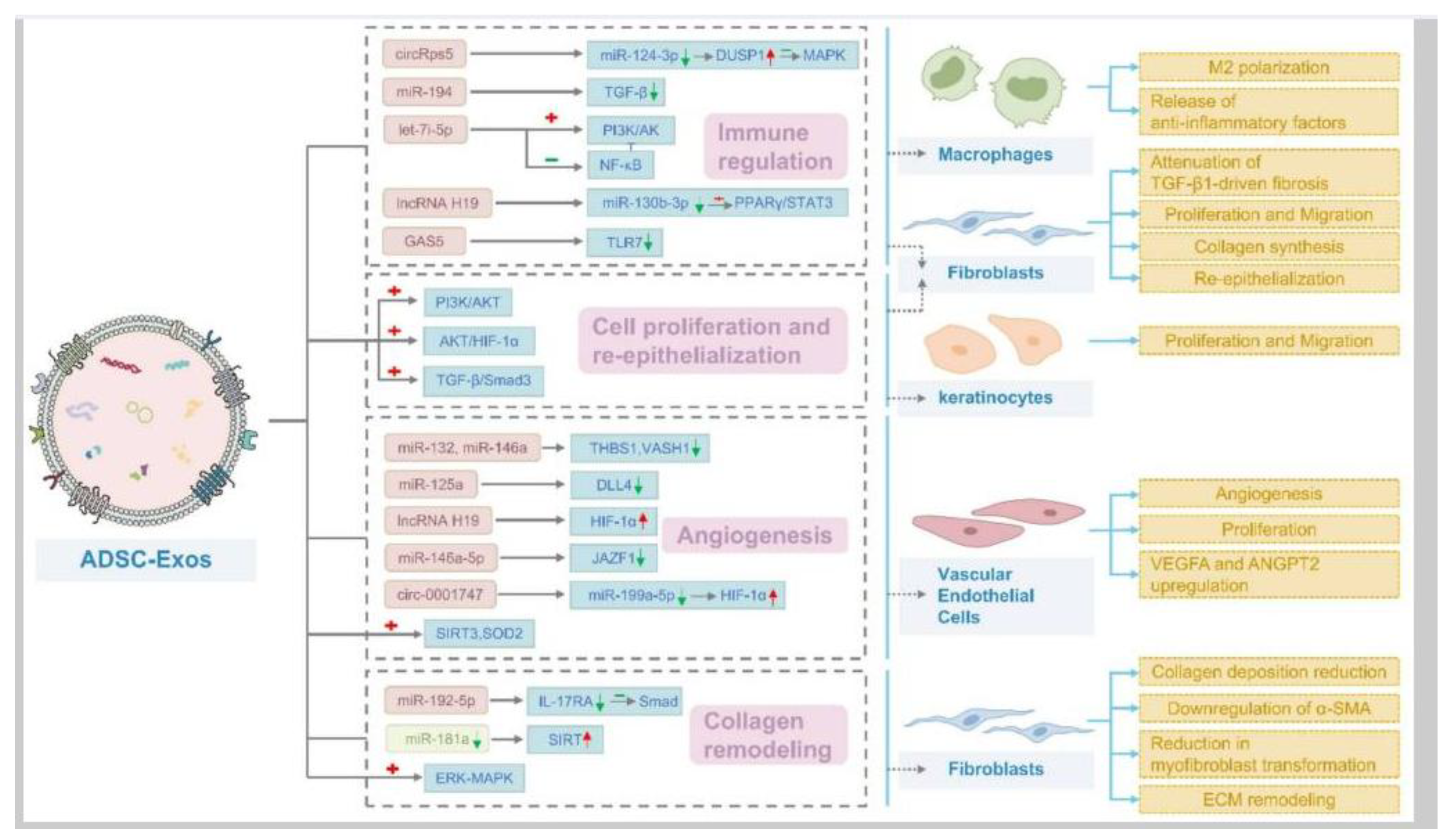

14. ADSC Secretome Contains microRNA, circRNA, and lncRNA

Defining these 3 types of ncRNA, circRNA functions as a miRNA sponge. This means it can bind to specific miRNAs, such as miR-151a, and thus inhibit their activity. By sponging miRNAs, circRNAs like circRps5 can indirectly regulate the expression of target mRNAs that would otherwise be regulated by those miRNAs (Misir et al, 2022). miRNA are short, linear strands of nucleotides, usually about 20 nucleotides in number. They are very diverse, about 2,000 types in mammals, and very powerful. miRNAs primarily function by binding to messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and inhibiting protein production by inducing mRNA degradation or repressing translation, but can also modulate transcription if delivered to the nucleus (Diener et al, 2024). lncRNAs exhibit a wider range of regulatory mechanisms. They can interact with DNA, RNA, and proteins to regulate gene expression at various levels: epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional. Some lncRNAs can act as miRNA sponges by binding to miRNAs and preventing them from targeting mRNAs, effectively indirectly regulating gene expression. They can also be precursors of miRNAs (Mattick et al, 2023).

Yang et al (2022) found that hypoxic preconditioned ADSCs can promote the biasing of macrophage from M1 to M2 in brain injury by releasing exosomes containing high levels of circRps5. Circular RNAs (circRNAs) such as circRps5 are a type of endogenous noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) with single-stranded closed-loop RNA molecules lacking terminal 5’ caps and 3’ poly-adenylated tails (Zhou et al, 2020). A microRNA, miR-124-3p, is a downstream target of circRps5 and downregulation of miR-124-3p can promote macrophage M2 polarization in nerve injury. Yin and Shen (2024) found that ADSCs exosomes regulate macrophage polarization to promote diabetic wound healing via the circRps5/miR-124-3p axis. Although ADSC exosomes contain circRps5, in the Yin and Shen (2024) study ADSCs were transfected with circRps5 overexpression (OE-circRps5) plasmids to increase the level of circRps5, while empty plasmids were used as negative controls (OE-NC).

In vitro and in vivo studies in mice found that ADSCs-derived exosomal miR-19b promotes skin wound healing by targeting CCL1 and regulating TGF-β pathway (Cao et al, 2020).

15. ADSC Secretome Contains Many Protein Types

Table 1.

Some of the proteins found in ADSC secretome.

Table 1.

Some of the proteins found in ADSC secretome.

| Molecule/Factor |

Description |

| Angiogenin |

Proangiogenic |

| CCL2 |

Proangiogenic |

| Collagens: COL1A1, COL1A2, COL6A1, COL6A2, COL6A3 |

Extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins |

| CT HRC1 |

Collagen triple helix repeat containing-1, involved in tissue repair |

| CXCL8 |

Proangiogenic |

| EGF |

Growth factor |

| FGF-2 |

Growth factor |

| Fibronectin |

ECM protein |

| Fibulin 2 |

Matrix protein, basement membrane integrity |

| FLNA |

Filamin A, maintains cytoskeletal and matrix structure |

| Gal-9 (Galectin-9) |

Negatively regulates Th1/Th17 immunity, promotes M2 macrophage polarization |

| HAPLN-1 |

Hyaluronic and proteoglycan link protein, important for ECM structure/flexibility |

| HGF |

Hepatocyte growth factor |

| Ho-1 |

Heme oxygenase 1, anti-inflammatory, possibly secreted by ADSCs |

| HSP 105 |

Heat shock protein |

| HSP 60 |

Heat shock protein, protects and repairs proteins |

| HSP 70 |

Heat shock protein, protects and repairs proteins |

| HSP 90 |

Heat shock protein |

| IGF-1 |

Growth factor |

| IL-10 |

Inhibits NF-κB, reduces inflammation |

| IL-6 |

Promotes anti-inflammatory Th2 differentiation/cytokine secretion |

| IL1RA |

Anti-inflammatory, inhibits Beta-cell differentiation |

| Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) |

Activates aryl hydrocarbon receptor to reduce skin inflammation |

| ITIH2 |

Stabilizes matrix |

| Kynurenic acid |

(Tryptophan metabolite) Activates aryl hydrocarbon receptor, reduces skin inflammation |

| Kynurenine |

(Tryptophan metabolite) Activates aryl hydrocarbon receptor, reduces skin inflammation |

| LAMP2 |

Aids in recycling proteins via the lysosome |

| LGALS3BP |

Promotes integrin-mediated cell adhesion; stimulates host defense |

| MANF |

Protects from cellular stress; aids wound healing |

| MARCKSL1 |

Regeneration of tissue |

| MFAP5 |

Microfibrillar-associated protein 5; ECM component |

| MMP-9-+ |

Migration |

| NGF |

Nerve growth factor |

| PDGF |

Growth factor |

| PRELP |

Glycoprotein secreted into ECM, collagen-rich tissues |

| SFRP4 |

Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein 4; reduces inflammation/oxidative stress |

| SIRT1 |

Cell metabolism, survival, anti-senescence, DNA repair, proliferation |

| SOD2 |

Superoxide dismutase, antioxidant |

| TGF-β |

Growth factor |

| TIMP-1 |

Migration |

| TNC |

Tenascin, matrix protein |

| TSG-6 |

Anti-inflammatory/tissue protective; improves wound healing |

| VEGF |

Growth factor |

16. ADSC Secretome Contains Many Bioactive Lipid Types

Although the lipidomics of ADSC secretome has not been as well studied as the proteomics and RNA omics, a number of bioactive lipids and their beneficial roles in physiology have been reported. For example, the in vitro effect of 2AG and PEA, at the concentrations quantified in ADSC secretome, in a cellular model of osteoarthritis , was found beneficial (Casati et al, 2022).

Considering palmitoyl ethanolamine, PEA’s multiple mechanisms of action generate therapeutic benefits in many disorders, including allergic reactions, influenza, common cold, chronic pain, joint pain, psychopathologies, enhanced muscle recovery, and neurodegeneration (Clayton et al, 2021). Endogenous PEA is generally insufficient to counter chronic allostatic load as seen in chronic inflammatory disorders (Hauer et al, 2012), making exogenous administration, such as administration of ADSC secretome, a therapeutic strategy to supplement endogenous levels and restore bodily homeostasis.

17. BMSCs Age More quickly Than ADSCs

When comparing experimental data of BMSCs to ADSCs from the same human donor, “ADSCs have a “younger” phenotype,” according to stem cell scientists (Burrow et al, 2017). Indeed, a number of studies (Burrow et al, 2017; Wu et al, 2018; Ismail et al, 2018) found that BMSCs have, among other negative attributes compared to ADSCs, an increased level of senescence compared to matched ADSCs. Trotzier et al (2024) found that the secretome and its positive effects in wound healing, including angiogenesis, was not affected by the donor’s age of the ADSC. Senescent cells develop the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), a pro-inflammatory set of molecules where the local tissue effects of a SASP or specific SASP components have been found to be involved in a wide variety of age-related pathologies in vivo such as hyperplastic diseases, including cancer. During senescence, aging-induced immunosenescence predisposes inflammatory disturbances of the skin, including pruritic dermatoses and type 2 inflammation (Chen et al, 2022). This immunosenescence is characterized by a chronic release of pro-inflammatory cytokines driving type 2 inflammatory (Th2 cells) dermatoses.

BMSCs reside in fatty tissue within the marrow and the status of the fat (aging, adiposity) can significantly reduce the BMSCs regenerative capacity (Ambrosi et al, 2017).

18. Transfer of Mitochondria in EVs Contained in Secretome from ADSC

EVs isolated from ADSCs were demonstrated to have potent anti-inflammatory properties in an experimental TMJOA (temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis) model by transferring functional mitochondria (Mei et al, 2025). The target cell was found capable of internalizing both ADSCs-EVs and their mitochondria both in vivo and in vitro, a step that is vital for the therapeutic outcome. ADSC-derived mitochondrial transplantation has been found to reduce levels of ROS, mtROS and cleaved-caspase 3 and increase the levels of superoxide dismutase and ATP (Zhai et al, 2024).

19. Heat Shock Proteins and GPRs in ADSC Secretome – Including Soluble Fraction

Stress-inducible intracellular chaperones include heat shock proteins (HSP) and glucose-regulated proteins (GPR). Mitchell et al (2019) detected many proteins in the soluble fraction that have previously been described in the MSC secretome, including Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) (HSP60, HSP90, HSP105). ADSC secretome was significantly more effective at increasing the production of GRPs in lung epithelial cells than was BMSC secretome (Shologu et al, 2018). Heat shock proteins can protect cells from stress and help to indirectly repair damaged proteins, including collagen (Hu et al, 2020).

20. Skin Longevity

Skin longevity focuses on the root causes of deterioration associated with aging at the molecular and tissue levels to help prevent or minimize senescence. Clinical studies demonstrate that topical or intradermal application of ADSC secretome, using technologies like microneedling or fractional laser, leads to significant improvements in skin aging features, such as reduction of wrinkles and hyperpigmentation. These treatments enhance skin rejuvenation, as measured by clinical scales and imaging systems (Yusharyahya et al, 2023).

Laboratory studies have found that ADSC secretome, rich in growth factors (like TGF-β, IGF, PDGF, HGF), antioxidants (e.g., SOD2), cytokines, and other bioactive components, protects human dermal fibroblasts from UVB-induced and intrinsic aging damage, by: Increasing cell proliferation, decreasing cell apoptosis and senescence, restoring collagen and elastin gene expression, and promoting extracellular matrix synthesis and reducing inflammation (Wang et al, 2015). ADSC secretome has also been found to reduce reactive oxygen species levels in UV-damaged human fibroblasts, upregulate the expression of HAS1 and COL1, and inhibit MMP2 (Shin et al, 2023)

21. Activation of PPAR-ϓ

Administration of ADSCs exerted a significant protective effect against Ischemia-Reperfusion Lung Injury in mice, and the effect is attributed to the activation of the PPARγ/NF-κB pathway (Miyashita et al, 2024), which then decreases inflammation. While we can’t rule out cellular contact, the mechanisms of action were likely due to paracrine factors.

22. Safety of ADSCs

ADSC secretome has been found to inhibit cancer, including inhibiting growth of drug resistant triple negative breast cancer cells (Nadesh et al, 2021). ADSC-EVs possess antitumor properties, reducing glioblastoma cell proliferation and invasiveness, and are being studies as anticancer therapeutics and medicine carriers (Gečys et al, 2023). ADSCs derived from cancer patients have been found to be safe for therapeutic development (Garcia et al, 2014). ADSC secretome has an anti-tumorigenic effect on B16 melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo (Lee et al, 2015). Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit melanoma growth in vitro and in vivo (Ahn et al, 2015). Reza et al (2016) found that human ADSC-derived conditioned medium (CM) exhibited inhibitory effects on A2780 human ovarian cancer cells by blocking the cell cycle, and activating mitochondria-mediated apoptosis signalling. They found that ADSC exosomes inhibit proliferation, wound-repair and colony formation ability of A2780 and SKOV-3 cancer cells. Further, they found that ncRNA contained in the exosomes from ADSCs was important for inhibiting cancer cell proliferation.

ADSCs and fat grafting for treating breast cancer-related lymphedema is safe and efficacious during a one year follow-on, where patient-reported outcomes improved significantly with time (Toyserkani et al, 2019).

23. Tumorigenicity of BMSCs and UMSCs

In Vitro studies have found umbilical cord MSCs and their exosomes promoted a malignant phenotype of polyploid NSCLC cells through the AMPK signaling pathway (Wang et al, 2022).

Long-term cultures of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells frequently undergo spontaneous malignant transformation (Rosland et al, 2009).

Exosomes from BMSCs can transmit oncogenic signals to target cells (Zhu et al, 2012), and in particular, exosomes from BMSCs that have been educated by cancer cells can transmit oncogenic signals to target cells (Zhou et al, 2018). BMSCs can become mobile and circulate through the blood, including to sites of wounded skin (Sasaki et al, 2008). As they circulate, BMSCs can fuse with cancer cells, becoming carcinogenic (Zhang et al, 2024). For example, multiple myeloma cells can fuse with BMSCs (Wang et al, 2018), as can bladder cancer cells (Tajima et al, 2022).

Bone is the most frequent destination of metastatic breast cancer cells and is also the most common site of first distant relapse of breast cancer. Breast cancer cells that spread to the bone form bone metastases or reside in bone marrow as dormant disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) or micrometastases. In bone, the fates of cancer cells are determined by the interaction of cancer cells with resident cells and cytokines in the bone microenvironment. Cancer cells not only educate the bone microenvironment to become a suitable soil for their survival, but also represent metastatic seeds for secondary dissemination invigorated by the bone microenvironment (Huang et al, 2023).

Considering one type of cancer, the bone is the most common site of breast cancer (BC) metastasis and BMSCs can attain phenotypic characteristics of BC as a result (Lung et al, 2019). Once a tumor cell disseminates into the BM, the cancer cell often displays phenotypic characteristics of BMSCs rendering cancer cells difficult to distinguish from BMSCs (Sai and Xiang, 2018). Studies indicate that BMSCs can fuse with cancer cells, forming hybrid cells with characteristics of both cell types. BMSCs are also found outside of the niche in peripheral blood (Chong et al, 2012) and home into sites of injury (Ponte et al, 2009) and cancer tissue where they are educated into becoming a pro-cancerous phenotype (Sai et al, 2019). Recirculated melanoma and myelogenous leukemia cells (Ishikawa et al, 2007) in BM interact with BMSCs to change the phenotype of the BMSC to one that is cancer promoting by enhancing their proliferation, migration, and invasion and altering the production of proteins involved in the regulation of the cell cycle (Ma et al, 2019). Indeed, melanoma tumor cells start to disseminate to BM during the initial steps of tumor development (Rocken, 2010). In breast cancer patients, detection of recirculated cancer cells that disseminated in BM predicts recurrence of the cancer (Tjensvoll et al, 2019). Cancer cells can fuse with BMSCs and change their phenotype (Terada et al, 2002), or release exosomes to change the phenotype of BMSCs to cancer promoting (Nakata et al, 2017). Indeed breast tumor cells fuse spontaneously with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (Noubissi et al, 2015). This fusion may facilitate the exchange of cellular material from the cancer cell to the BMSC rendering the fused cell more oncogenic (Chitwood et al, 2018). Further, others have found the same result of this fusion and exchange of cellular material, which has been found to increase metastasis. For example, Li et al (2014), found that human hepatocellular carcinoma cells with a low metastatic potential exhibit a significantly increased metastatic potential following fusion with BMSCs in vitro and in xenograft studies. In the end, the BMSCs and their molecules/exosomes (Vallabhaneni et al, 2015), having been conditioned by tumor cells, were found to increase the probability of cancer in human patients (Medyouf et al, 2014). The various phenotypes of BMSCs, including the cancerous phenotypes are difficult to distinguish (Joose et al, 2015). In contrast, even ADSCs derived from cancer patients have been found to be safe for therapeutic development (Garcia et al, 2014).

Peinado et al (2012) found transfer of the MET oncoprotein from tumor-derived exosomes to BM progenitor cells promote the metastatic process in vivo. Importantly, they demonstrated that exosomes can alter the BM in a durable manner; these results suggest that genetic or epigenetic changes could be involved in this phenomenon as BM cells retain the “educated” phenotype following engraftment into a new host.

24. No Immune Triggering by MHC Proteins

ADSC exosomes are characterized by the absence of immune triggering proteins such as MHC class I and II and co-stimulatory molecules. Regarding to MHC class I, the hADSCs cell lines contains very low levels of MHC class I and the expression of this molecule in ADSC exosomes has not been found (Blazquez et al (2014).

ADSCs ameliorate bone marrow aplasia related with graft-versus-host disease in animal models (Nishi et al, 2019).

25. Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells Dampen Inflammation

Teleologically thinking, the ADSCs are present following birth to dampen inflammation that may arise in the baby’s new hostile, non-sterile environment that presents after birth. The ADSCs are not needed in the sterile (Kennedy et al, 2023), fetal environment because inflammation is not needed in this case to fight infection. Without the possibility of infection, inflammation to fight infection is not required. The ADSCs arise as tissue specific stem cells in the skin that have developed during the third trimester. Differences between tissues are not strongly driven by gene expression but are more due to tissue-specific subcellular components and processes, i.e. tissue specific networks (Laman Trip et al, 2025). The stem cell niche of the skin will help to direct these ADSCs to develop in a manner that is tissue specific and serves to resolve inflammation in that adult skin. Inflammation releases cytotoxic molecules that damage the host tissue (Arnhold, 2023) that must be suppressed when no infection is present.

Following birth, the skin is under constant insult from traumatic injuries, toxins, antigens, allergens, UV, and pathogens. Those are signals for inflammation. When the skin is compromised by these factors, evolution has given the skin an inflammatory response to fight associated infection. Any of these factors can lead to barrier disruption and an eventual infection, and the inflammatory response is the key to fighting infection. But inflammation is damaging. Not only does infection fight invading pathogens, but inflammation also damages our own cells and tissues.

Cell metabolites reflect the biochemical phenotype of the mesenchymal stem cells. Li et al (2018) conducted a comprehensive investigation into the metabolic differences between ADSCs and BMSCs. They found that ADSCs differ from BMSCs in the components of the linoleic acid pathway, including bovinic acid, 12,13-EpOME, 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid, and 9,10-epoxyoctadecenoic acid. Metabolites in the linoleic acid pathway have been found to protect against inflammation by reducing oxidative stress (Hassan Eftekhari et al, 2013). Thus, considering this pathway alone, the higher concentration of linoleic acid pathway metabolites in ADSCs suggests that they may have a greater therapeutic potential for treating inflammatory skin diseases compared to BMSCs.

Considering fibroblasts, which are related to ADSCs (Denu et al, 2016), Gopee et al (2024) found that all adult fibroblast subsets expressed high levels of inflammatory cytokines and receptors (for example, IL6 and IL1RA) and genes involved in antigen presentation (for example, HLA-A), innate immune and inflammatory responses (for example, CD55 and PTGES) and cellular senescence (CDKN1A). In contrast, prenatal skin fibroblasts had upregulated genes involved in immune suppression (CD200), regulation of inflammation (for example, RAMP2) and tissue regeneration (MDK). Thus, fetal fibroblasts are optimized for anti-inflammatory, scarless wound healing, while adult fibroblasts develop to induce inflammation and rapidly close wounds. The results of Gopee et al (2024) provide further evidence of the progressive acquisition of scar-promoting gene expression in later gestation and after birth, consistent with the clinical observation of scarring in adults and third trimester skin (Longaker and Adzick, 1991). Gopee et al (2024) also found that yolk sac macrophages contributed to skin development, including angiogenesis through macrophage-related factors that drive GATA2 activity and downstream VEGF receptor expression. This is similar to M2 macrophages that have been polarized to the M1 subtype by the secretome of ADSCs (Zhu et al, 2020; Wang et al, 2022) in adult skin to drive angiogenesis.

26. Bone Marrow and Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Don’t Dampen Inflammation

This sort of skin tissue specific development of mesenchymal stem cells doesn’t happen in the bone marrow or the umbilical cord. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells enter the skin during wounding of the skin. Brought in through the blood supply, BMSCs serve to recruit inflammatory immune cells, leading to inflammation, and rapidly close the wound, leading to fibrotic scarring.

There’s much hype about cytokines from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs), and the molecules they release, prolong and enhance inflammation by increasing survival and function of neutrophils (Castella et al, 2011; Liang et al, 2024). BMSC secretome also reprograms hematopoietic stem cells to become inflammatory white blood cells (Ng et al, 2023). Under hypoxic conditions, which induces the activation of TRL4, BMSCs secrete pro-inflammatory factors and decrease the polarization of macrophages from the M1 to M2 phenotype, the M2 type being anti-inflammatory and therefore the BMSCs are promoting more inflammation (Faulknor et al, 2017; Waterman et al, 2010). Thus, BMSCs cultured in normal hypoxic conditions in the laboratory are secreting pro-inflammatory factors and when administered to wounded skin will induce inflammation by recruiting neutrophils and M1 type pro-inflammatory macrophages. ADSCs have consistently exhibited much greater anti-inflammatory capabilities, phagocytic activity, anti-apoptotic capability activity and cell viability over BMSCs (Li et al, 2019).

So inflammation has to be dampened, otherwise, if it is prolonged, necroinflammation ensues and our tissues become necrotic or otherwise damaged. Without inflammation being reduced, the damaging inflammatory pathways cause more inflammation and scale-up the damage. And what is present in adult skin to resolve inflammation? It’s the adipose mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) and the molecules that they release. In this case, the molecules from ADSCs can help the healing process by a number of mechanisms, including angiogenesis and reducing inflammation. The molecules from ADSCs induce an anti-inflammatory pro-regenerative state in the skin. Diabetic ulcers are example, where the necrotic tissue, such as Necrotizing fasciitis, has to be removed to reduce the inflammation. In these conditions, the ADSCs are no longer present at the site of open wound, and inflammation is hard to control. Addition of ADSC secretome facilitates the healing of the diabetic ulcer through a number of mechanisms, including the reduction of inflammation.

ADSCs are preferred over, 1. bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and platelets, which serve to induce inflammation and rapid fibrotic scarring, and 2. over umbilical cord or placental mesenchymal stem cells, that have evolved to operate in the sterile conditions of the womb to form the cord, which is unlike skin structure and function, and since it’s a sterile environment, not dampen inflammation.

While the data for human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell secretome and exosomes is sparse, reports from clinical trials that use their exosomes topically, have reported poor results. For example, one subject was quoted as saying, “I don’t think I’d recommend it. The results were very underwhelming” (Hamzelou, 2024). The subject received three treatments, three months apart, as part of a trial her dermatologist was participating in. As a participant, Sarah didn’t have to pay for her treatment. In each of the sessions, the physician numbed Sarah’s face with lidocaine cream before microneedling it. Then the physician applied the exosomes on the skin that has been microneedled using a syringe.

27. ADSCs Have Better Regenerative Capacity Than Do BMSCs

When compared to BMSCs, El-Badawy et al (2016) found that ADSCs displayed higher resistance to hypoxia-induced apoptosis, and to oxidative stress-induced senescence, and showed more potent proangiogenic activity. mRNA expression analysis showed that ASCs had a higher expression of Oct4 and VEGF than BMSCs, and that ADSCs had a remarkably higher telomerase activity, and thus superior self-renewal capacity (Morrison et al, 1996). Bone marrow fat (BMF) is located in the bone marrow cavity and accounts for 70% of adult bone marrow volume (Wang et al, 2018). BMSCs reside in the fatty tissue of bone marrow, and may be influenced by the inflammatory nature of the fatty tissue (Marinelli et al, 2024; Hardaway et al, 2014; Bi et al, 2021), including inflammatory T-cells and cancer cells that circulate to the bone marrow. Bone marrow provides favorable conditions for tumor cell proliferation and growth (Mishra et al, 2011; Yang et al, 2024) and fusion of cancer cells with BMSCs cause the BMSCs to shift to glycolysis for energy, the “Warburg Effect,” yielding a pro-inflammatory phenotype (Mawaribuchi et al, 2024).

28. Safety And Efficacy Considerations: ADSCs Preferred Over BMSCs and UCMSCs

When compared with the BMSCs- and UCMSCs-treated groups, the ADSCs-treated group exhibited markedly accelerated healing efficiency, characterized by increased wound closure rates, enhanced angiogenesis, and collagen deposition at the wound site in an animal model (Cao et al, 2024). ADSCs are also better at preventing fibrosis than BMSCs (Yoshida et al, 2023), and the ADSC secretome has been found to alleviate fibrosis associated with scleroderma (Xiao et al, 2025). ADSC-Exosomes perform antifibrotic actions through the miR-181a-5p/Smad2 pathways (Shao et al, 2023). When addressing safety and efficacy concerns of stem cells, we must consider tissue-specific stem cells, first described by Dr. Elly Tanaka, a professor of science at the IMP in Vienna. Choosing the appropriate stem cell type to match the condition to be treated is critical not only to efficacy, but most importantly, safety of the therapeutic. Beyond the genetic and epigenetic factors that influence stem cell phenotype as embryonic stem cells differentiate into somatic stem cells, the immediate niche of the stem cell will have profound influence on the cell’s phenotype. For regenerating the skin, then use tissue specific stem cells from the skin. For example, we know that adipose mesenchymal stem cell secretome is superior to that of BMSCs because it preferentially helps to rebuild the epidermis by stimulating basal keratinocytes (Ademi et al, 2023) and rebuild matrix by releasing clusterin and decorin (Matukumalli et al, 2017). ADSCs and their secretome is efficacious and safe. Even ADSCs from cancer patients can been safely used for therapeutic purposes. Further, ADSC secretome has been found to inhibit cancer, including inhibiting growth of drug resistant triple negative breast cancer cells (Nadesh et al, 2021).

Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UMSCs) because they are not tissue specific to the skin, and they didn’t evolve to work in adult tissue where inflammation needs to be inhibited. In Vitro studies have found umbilical cord MSCs MSCs and their exosomes promoted a malignant phenotype of polyploid NSCLC cells through the AMPK signaling pathway (Wang et al, 2022). Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) do appear in the skin, but only transiently in the skin during open wounds to close the wound quickly (yielding fibrotic scarring). induce inflammation (destructive to tissue) and cause high rates of proliferation (pro-oncogenic). Considering their role in wound closure, the BMSCs appear transiently during an open wound to fight infection by inducing inflammation, and closing the open wound quickly by hyper-proliferation of cells. BMSCs and their released molecules didn’t evolve to be present in the skin for long periods of time – only transiently. Applying BMSC molecules for an extended time will induce too much inflammation and too much proliferation, leading to long term inflammation, fibrotic scarring, and a pro-oncogenic state. For example, BMSCs express much CTHRC1 protein (Turlo et al, 2023), which may help to promote fibrosis (Liu et al, 2023).

Beyond their suboptimal efficacy profile, I’ll briefly explain some of the mechanisms underlying the choice of not using BMSCs because of a poor safety profile. The complexity of the bone marrow (BM) niche can lead to many stem cell phenotypes, whether we consider hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) or bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs). Here I will discuss the properties of BMSCs, not HSCs. Because of the complexity, many BMSC phenotypes exist, including disease causing phenotypes that are varied and hard to distinguish – a part of the problem in using BMSC for therapeutic development. This complication, unlike that for ADSCS, includes recirculated cells, particularly recirculated cancer cells. Once a tumor cell disseminates into the BM, the cancer cell often displays phenotypic characteristics of BMSCs rendering cancer cells difficult to distinguish from BMSCs (Sai and Xiang, 2018). BMSCs are also found outside of the niche in peripheral blood (Chong et al, 2012) and home into sites of injury (Ponte et al, 2007) and cancer tissue where they are educated into becoming a pro-cancerous phenotype (Sai et al, 2019). Recirculated melanoma and myelogenous leukemia cells (Ishikawa et al, 2007) in BM interact with BMSCs to change the phenotype of the BMSC to one that is cancer promoting by enhancing their proliferation, migration, and invasion and altering the production of proteins involved in the regulation of the cell cycle. Indeed, melanoma tumor cells start to disseminate to BM during the initial steps of tumor development (Rocken et al, 2010). In breast cancer patients, detection of recirculated cancer cells that disseminated in BM predicts recurrence of the cancer (Tjensvoll et al, 2019). Cancer cells can fuse with BMSCs and change their phenotype (Terada et al, 2002), or release exosomes to change the phenotype of BMSCs to cancer promoting (Nakata et al, 2017). Indeed breast tumor cells fuse spontaneously with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (Noubissi et al, 2015). This fusion may facilitate the exchange of cellular material from the cancer cell to the BMSC rendering the fused cell more oncogenic (Chitwood et al, 2018). Further, others have found the same result of this fusion and exchange of cellular material, which has been found to increase metastasis. For example, Li et al (2014) found that human hepatocellular carcinoma cells with a low metastatic potential exhibit a significantly increased metastatic potential following fusion with BMSCs in vitro and in xenograft studies. In the end, the BMSCs and their molecules/exosomes, having been conditioned by tumor cells, were found to increase the probability of cancer in human patients (Medyouf et al, 2014). The various phenotypes of BMSCs, including the cancerous phenotypes are difficult to distinguish (Joosse et al, 2015). In contrast, even ADSCs derived from cancer patients have been found to be safe for therapeutic development (Garcia-Contreras, 2014).

One of many reasons why ADSCs are preferred compared to BMSCs is that ADSCs express a low level of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules and do not express MHC class II and costimulatory molecules. Even the exosomes of BMSCs express MHC class II proteins (Conese et al, 2020). These problems in BMSCs are amplified when using donor, allogeneic BMSCs that have been replicated many times, essentially aging the cells, during expansion to develop the therapeutic. This is in contradistinction to ADSCs. Critically, when comparing experimental data of BMSCs to ADSCs from the same human donor, “ADSCs have a “younger” phenotype,” according to stem cell scientists [

130]. Indeed, Burrow et al found that BMSCs have, among other negative attributes compared to ADSCs, an increased level of senescence compared to matched ADSCs. Senescent cells develop the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), a pro-inflammatory set of molecules where the local tissue effects of a SASP or specific SASP components have been found to be involved in a wide variety of age-related pathologies in vivo such as hyperplastic diseases, including cancer. During senescence, aging-induced immunosenescence predisposes inflammatory disturbances of the skin, including pruritic dermatoses and type 2 inflammation (Chen et al, 2022). This immunosenescence is characterized by a chronic release of pro-inflammatory cytokines driving type 2 inflammatory (Th2 cells) dermatoses.

Whereas the use of BMSC transplants has a history of medical adverse events, including the induction of cancer in the recipient (Maguire, 2019), fat grafting, along with its constituent ADSCs, have a long history of safety in medical procedures dating back to 1893 when the German surgeon Gustav Neuber transplanted adipose tissue from the arm to the orbit of the eye in an autologous procedure to fill the depressed space resulting from a postinfectious scar (Mazzola and Mazzola, 2013). Fat grafting’s long history of being safe, regardless of the harvesting techniques used in patients (Agostini et al, 2012), has been recently reviewed by physician-scientists at Baylor College of Medicine (Raj et al, 2020). Furthermore, physician-scientists at Stanford University School of Medicine have recently reviewed the safety and efficacy of using ADSCs to augment the outcomes of autologous fat transfers (Zielins et al, 2016). Toyserkani et al (2019) have found that ADSCs and fat grafting for treating breast cancer-related lymphedema is safe and efficacious during a one year follow-on, where patient-reported outcomes improved significantly with time. In a randomized, comparator-controlled, single-blind, parallel-group, multicenter study in which patients with diabetic foot ulcers were recruited consecutively from four centers, ADSCs in a hydrogel was compared to hydrogel control. Complete wound closure was achieved for 73% in the treatment group and 47% in the control group at week 8. Complete wound closure was achieved for 82% in the treatment group and 53% in the control group at week 12. The Kaplan–Meier (a non-parametric statistic used for small samples or for data without a normal distribution) median times to complete closure were 28.5 and 63.0 days for the treatment group and the control group, respectively (Moon et al, 2019). Treatment of patients undergoing radiotherapy with adult ADSCs from lipoaspirate were followed for 31 months and patients with “otherwise untreatable patients exhibiting initial irreversible functional damage” were found to have systematic improvement or remission of symptoms in all of those evaluated (Rigotti et al, 2007). In animal models with a full thickness skin wound, administration of ADSCs, either intravenously, intramuscularly, or topically, accelerates wound healing, with more rapid reepithelialization and increased granulation tissue formation (Kim et al, 2019), and topically applied the ADSCs improved skin wound healing by reducing inflammation through the induction of macrophage polarization from a pro-inflammatory (M1) to a pro-repair (M2) phenotype (Zomer et al, 2020).

Thus, adipose mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) have a long history of safety and efficacy and unlike stem cells from tissues other than the skin (BMSCs and UMSCs) and stem cells from non-adult sources in the womb (UMSCs), evolved to work in the skin of adults to inhibit inflammation and to reset the innate and adaptive immune systems of the skin to a anti-inflammatory, pro-regenerative healing state to maintain and regenerate normal, non-fibrotic skin structure and function.

29. BMSC Induced Inflammation

Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs) and the molecules they release prolong and enhance inflammation by increasing survival and function of neutrophils (Castella et al, 2011). Under hypoxic conditions, which induces the activation of TRL4, BMSCs secrete pro-inflammatory factors and decrease the polarization of macrophages from the M1 to M2 phenotype (Faulknor et al, 2017; Waterman et al, 2010). Therefore, BMSCs cultured in normal hypoxic conditions in the laboratory are secreting pro-inflammatory factors and when administered to wounded skin will induce inflammation by recruiting neutrophils and M1 type pro-inflammatory macrophages. When BMSC secretome is applied to the skin, these are the pro-inflammatory molecules damaging your skin. In contradistinction, consider the molecules in the secretome of ADSCs. The phenotype of the cell and the stem cell released molecules (also called the secretome) from skin-derived adipose mesenchymal stem cells (AMSCs) are largely unaffected by prolonged hypoxia, not recruiting neutrophils (Kalinina et al, 2015), and the molecules released from ADSCs were found to better induce the effects of the anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage phenotype than the molecules released from BMSCs (Sukho et al, 2018). These results provide strong evidence that the molecules released from AMSC are more beneficial than those from BMSCs to induce appropriate wound healing processes through the shift from a pro-inflammatory state to an anti-inflammatory, pro-healing state.

These pro-inflammatory signals from BMSC cytokines are in addition to their likelihood of containing pro-oncogenic signals that are absent in AMSCs, that I have previously reviewed in multiple, peer-reviewed, National Library of Medicine journal articles (Maguire, 2019; 2021; 2022). For example, BMSCs promote multiple myeloma growth and confer drug resistance (Wang et al, 2023).

30. Regenerative Versus Reparative Healing of the Skin: Why You Don’t Need Inflammation to Heal Your Skin

Inflammation is for fighting pathogens, and it is destructive to the skin. Inflammation is not needed to regenerate the skin or induce collagen production, and actually slows and impedes the healing process. There is a potent and safe means to inhibit the inflammatory pathways and promote regenerative healing in the skin using the released molecules from skin derived adipose mesenchymal stem cells.

I continuously hear that inflammation is needed to heal the skin and to produce collagen and rebuild the matrix (

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/21660-inflammation). This is false, and I’ll tell you why, and tell you the differences in two healing processes, i.e 1. non-inflammatory

regenerative healing versus, 2. inflammatory

reparative healing. Collagen production in the skin to aid in healing, is mainly derived from fibroblasts, but also by keratinocytes (Oguchi et al, 1985) and anti-inflammatory, M2 type macrophages (Simões et al, 2020). Fibroblasts have evolved to regulate their synthesis of collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins in response to mechanical tension (Fisher et al, 2008). Fibroblasts are also induced to secrete collagen by the molecules released from ADSCs (Sondargaard et al, 2022). It’s not inflammation that stimulates the production of collagen.

Once we’ve exited the sterile or nearly sterile womb, most postnatal wounds heal through reparative healing, which is a complex biological process involving cells, signaling molecules such as growth factors and other cytokines, and the extracellular matrix (ECM). Wound healing has been oversimplified and described as occurring in four overlapping, highly coordinated stages: hemostasis, inflammatory, proliferation, and remodeling. In the womb, where there are no pathogens, inflammation is not needed to fight infection – there’s no pathogens present to infect the skin. In the fetus, the immune system in the skin is only beginning to develop and is not robust, and platelets that normally rush into wounded skin are not yet fully developed, and the blood cells are being produced in the liver and not in the bone marrow. Wound healing in the fetus is vastly different from that in the adult. Adipose mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) arise later in fetal development in order to control and resolve the newly formed inflammatory mechanisms in the skin that are important in the adult to fight infection using an inflammatory response.

Whether it is macrophages or T cells, including γδ T-cell subsets, or other immune cells, it is the ADSCs that serve to calm the early-onset inflammation by polarizing the immune cells from an inflammatory type to an anti-inflammatory, pro-regenerative type. This is in contrast to bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), which are a major source of IL-7, thus producing inflammation, and playing a pathological role in the maintenance of inflammatory CD4 memory T-cells that are involved in autoimmunity and chronic inflammation. BMSCs and the molecules they release also have oncogenic potential, another reason why they are an inferior choice for therapeutic development.

31. Regenerative Non-Inflammatory Healing Versus Reparative-Inflammatory Healing

Fetal wounds heal in utero through regenerative healing; postnatal microenvironments with an attenuated inflammatory response, such as the oral mucosa, also heal with regenerative characteristics, including a reduced immune response and scarring. Regenerative healing occurs in a manner similar to the same four stages of reparative healing, with some key differences. The key difference is that compared with reparative healing, the inflammatory response in regenerative healing is attenuated. Many of the cells involved in both innate and adaptive immunity, such as mast cells, macrophages, and neutrophils, are not yet differentiated or are not responsive to the wound where regenerative healing occurs. Therefore, levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are reduced or absent in regenerative healing.

Increased expression of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in postnatal regenerative healing helps decrease the inflammatory response. Adipose mesenchymal stem cells are a key source of the IL-10 secreted into the skin, and thus promoting regenerative healing. A number of studies suggests that IL-10 not only indirectly modulates fibrosis via its anti-inflammatory properties but may also stimulate fetal-like fibroblast behavior and thus fetal-like ECM production. If scar tissue is to be of normal structure, regenerative healing must take place. The secretion of IL-10 from ADSCs is key to inducing regenerative healing in adult skin. One mechanism to explain the ability of IL-10 to inhibit inflammation is that it inhibits NF-κB activity by inhibiting nuclear translocation of NF-κB by blocking IκBα, an inhibitor of NF-kB, degradation in response to TNF stimulation. The signaling pathway used by the IL-10 receptor, the signal transducer, to generate the anti-inflammatory response requires STAT3, the activator of transcription (Murray, 2006). Further, Janus kinases, JAK3, is recruited by IL-10 signaling, which then activates STAT transcription factors, predominantly STAT3 in this pathway (Niemand et al, 2003).

Without this IL-10 mechanism, fibrosis may progress where excess secreted ECM compresses and obliterates surrounding capillaries, then reducing blood flow and oxygen delivery, diminishing tissue water mobility, and reducing oxygen consumption (Martin et al, 2024). These responses further induce profibrotic stimuli that drive a fibrogenic positive feedback loop. Similar to chronic inflammation, fibrosis likely reflects an early evolutionary protective mechanism, in the case of fibrosis, to wall off organs from infection, as seen in tuberculous granulomas, a highly organized structure selected for in the preantibiotic era and widespread among vertebrates (Ravimohan et al, 2018).

32. Collagen Production in Wound Healing – Inflammation Degrades Collagen, Not Produce It

Collagen production in the skin to aid in healing, is mainly derived from fibroblasts, but also by ADSCs and keratinocytes. Fibroblasts have evolved to regulate their synthesis of collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins in response to mechanical tension. Fibroblasts are also induced to secrete collagen by the molecules released from AMSCs. It’s not inflammation that stimulates the production of collagen. Tissue damage caused by inflammation from an infection or an autoimmune disease triggers degradation of collagen in the extracellular matrix (ECM), which further enhances inflammation. So inflammation is degrading collagen, not producing it. Also know that dermal collagen has a half-life of about 15 years, a very long-lived protein, a feature that predisposes collagen to accumulate lesions such as advanced glycosylation end products (AGE), which have damaging effects on the molecules they bind. So with much collagen in the skin lasting for decades, accumulating damage through inflammation is occurring. The secretome from AMSCs can protect these long-lived collagen proteins from inflammatory damage, while also helping to replace damaged collagen.

33. ADSC Secretome and Collagen Production

The capability of ADSCs to enhance wound healing and reduce fibrosis suggests actions that modulate the ECM (Søndergaard et al, 2022; Renu, 2025). The secretome of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs) enhances collagen production through several mechanisms involving the secretion of growth factors, cytokines, exosomes, and other bioactive molecules. These components collectively stimulate extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and collagen synthesis. The ASC secretome is rich in growth factors such as transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2). TGF-β1plays a crucial role in stimulating fibroblasts to produce type I and III collagen that are essential components of the ECM (Young-Hyeon et al, 2021). ASC-derived EVs, including exosomes, carry proteins, microRNAs (such as miR-21 and miR-26), and other signaling molecules that enhance collagen synthesis. These EVs have been shown to increase the production of type I and III collagen in wound healing models. The ASC secretome contains matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors (TIMPs), which regulate ECM turnover. This balance promotes the deposition of new collagen while preventing excessive fibrosis. Regeneration in mammals is complex process, involving, for example, direct action of retinoid receptors by retinoic acid or its derivatives, but not retinol (Lin et al, 2025). The combined action of cytokines, growth factors, and EVs in the ASC secretome facilitates angiogenesis, recruits progenitor cells, and stimulates fibroblast activity. This creates a favorable microenvironment for ECM regeneration and collagen production

34. Targeting YAP

Higher levels of collagen III yield smaller, reticular structures with more basket-weave than collagen I and contribute toward regenerative wound healing. ADSC-exos treatment on full thickness rat wounds significantly reduced the number of EN1+ fibroblasts; thus, the effects of ADSC-exos on wound regeneration are likely achieved through inhibiting EN1+ fibroblast activation (Zhang et al, 2022)

ADSC-exos effectively inhibited expression of EN1 may be due to substances that can specifically target the YAP signaling pathway. It is known that the “cargos” carried by exosomes are crucial to their function, and miRNA is reported to be one of the most important substances

Activation of the YAP signaling pathway promotes renal fibrosis, pulmonary fibrosis and liver fibrosis and YAP degradation treated by ADSC-derived exosomes blocks the progression of fibrosis (Ji et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Liang et al., 2022) and both let-7 and miR-195 specifically target YAP as predicted by Targetscan (

https://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/).

For the ADSCs, the highly expressed miRNAs were found to be regulating osteogenesis (let-7/98, miR-10/100, miR-125, miR-196, miR-199, miR-615-3p, mir-22-3p, mir-24-3p, mir-27a-3p, mir-193b-5p, mir-195-3p) (Kauer et al, 2018).

35. ADSC Secretome Promotes Re-Epithelialization in Wound Healing

Barrier function of the epidermis of the skin is critical in maintaining the viability of deeper tissue structures and allowing proper wound healing processes to occur. Thus, a critical step of wound healing after an injury is the process of re-epithelialization (epidermal regeneration), which is carried out by epidermal keratinocytes, adipocytes (Merrick and Seale, 2020) and ADSCs (Huang et al, 2013) with the endpoint of reestablishing the skin's external barrier properties.

36. ADSC Secretome for Rosacea

TRPV1 activation induces neurogenic inflammation in rosacea (Lee et al, 2023). ADSC secretome significantly reduced TRPV1 expression, intracellular calcium ions influx and the release of inflammatory factors in a rosacea animal model (Zhou et al, 2024).

37. ADSC Secretome for Acne