1. Introduction

Integrating quantum phenomena into gravitation motivates emergent and thermodynamic models of spacetime. Building on entropic gravity [

1], the idea of induced gravity [

2], and holographic paradigms [

3], we introduce an intrinsically irreversible, dissipative term in the gravitational field equations, analogous to viscosity in continuous media. This viscoelastic extension treats spacetime as an effective medium with memory, in which quantum vacuum fluctuations induce dissipation. Recent experimental searches at the LHC for exotic multiplets incompatible with string theory [ref] illustrate that traditional unification frameworks may face severe challenges. This further motivates the exploration of alternative approaches, such as the present viscoelastic emergent gravity model, which does not rely on fundamental string symmetries but instead introduces dissipation and irreversibility from first principles [

4].

In entropic gravity scenarios [

1,

5], gravity emerges from entropy gradients with a local temperature

. Quantum fluctuations and FDT then suggest a relaxation time of order

for spacetime perturbations. While naïve estimates at the Planck scale give extremely short

, coarse-graining to macroscopic scales inflates

to a huge value

(greater than the Hubble time) [

6]. This yields a tiny but finite

acting as an effective gravitational dissipation coefficient (a “quantum viscosity” of the vacuum) [

7]. Even such small dissipation could have interesting cumulative effects in principle (e.g., some have speculated it might affect the cosmological constant [

7]), but as we show, current data constrain

to be so large that any macroscopic effects are virtually negligible.

In fluid dynamics, viscoelastic materials exhibit both elastic (energy-conserving) and viscous (dissipative) responses, leading to frequency-dependent attenuation of waves. By analogy, we extend GR to include a dissipative term while ensuring general covariance and stability. The construction is guided by relativistic causal hydrodynamics (e.g., Israel–Stewart theory [

8]) so as to avoid acausality. In the low-dissipation limit

, standard GR is recovered exactly. Below we formulate this extension and explore its phenomenology for gravitational waves (GWs).

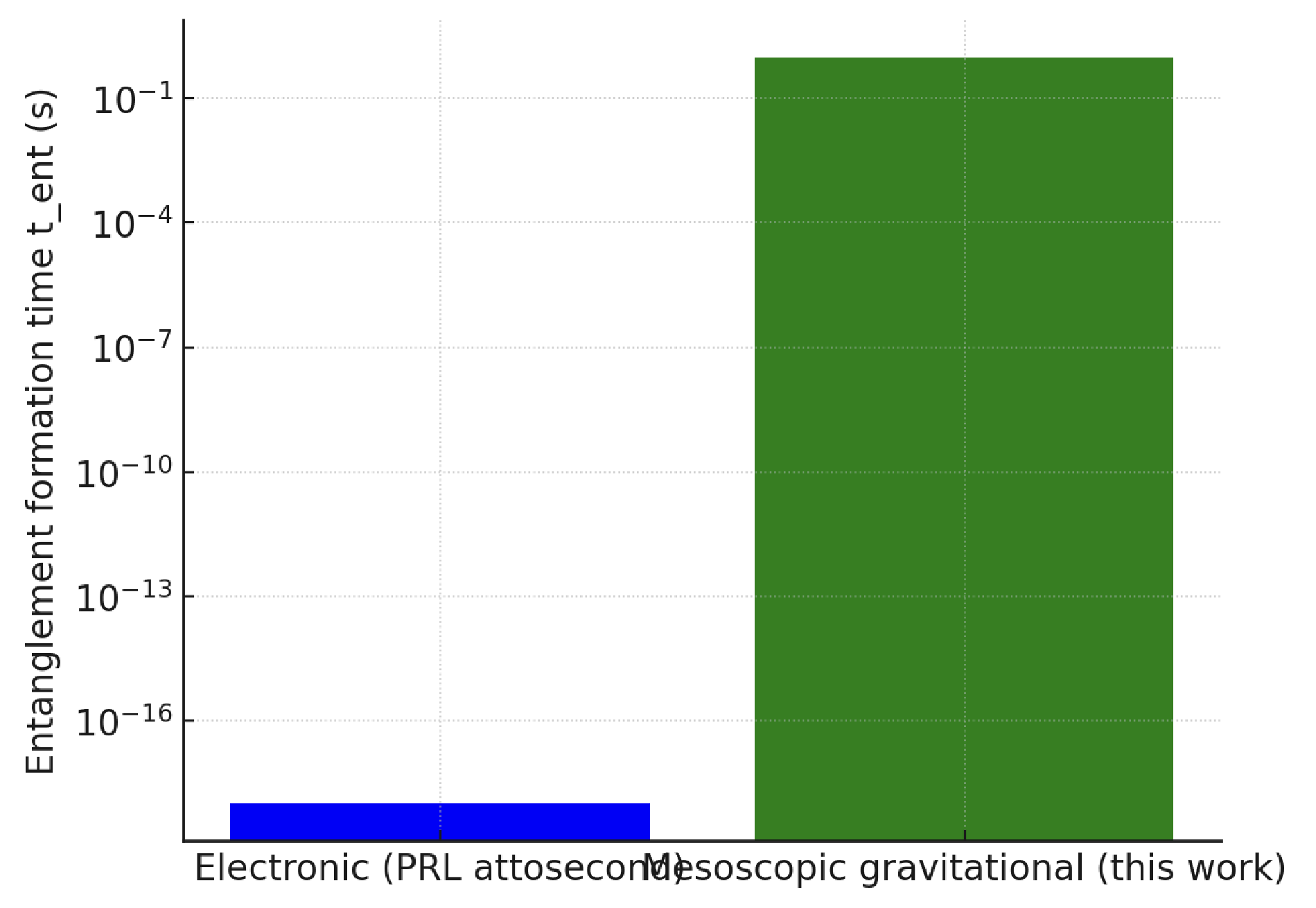

A recent study published in Physical Review Letters has demonstrated, via attosecond chronoscopy, that electronic entanglement develops over a finite “birth time” rather than appearing instantaneously. In our framework, the same principle naturally extends to the mesoscopic and gravitational regime: because the coherent coupling JJJ is many orders of magnitude weaker, the entanglement birth time shifts from attoseconds to seconds, provided that dissipation remains sufficiently small within the relevant time window.

2. Viscoelastic Extension of Einstein’s Equations

2.1. Causal Nonlocal Formulation (Memory Kernel)

A fully causal and dimensionally robust way to encode the dissipative response is to replace Eq. (

1) by a convolutional constitutive law,

with a retarded kernel

that vanishes for

. The minimal Kelvin–Voigt/Debye choice,

, yields in frequency space the susceptibility

and recovers Eq. (

1) as the leading term of a gradient expansion for

. This nonlocal form ensures causality (Kramers–Kronig), fixes dimensions unambiguously, and makes explicit that the effective description is that of an open system with a single relaxation scale

.

2.2. Preferred-Frame Constraints and SME/PPN Mapping

Introducing a timelike selects a global rest frame and must be consistent with precision tests of Lorentz symmetry. In a parametrized-post-Newtonian (PPN) language, this connects to preferred-frame parameters (e.g., , ), while in the Standard-Model Extension (SME), it maps to coefficients in the gravitational sector. Because our modification only perturbs propagation through a small, causal response ( today), the implied Lorentz-violation effects are suppressed by and remain below current bounds. A dedicated mapping of our linearized dispersion and radiation reaction to PPN/SME coefficients can be added in a companion note; here we restrict to the phenomenological statement that the bound inferred below renders any preferred-frame signals effectively negligible.

The standard Einstein field equation (with

included as needed) is:

where

is the Einstein tensor and

the stress-energy tensor. We modify this equation to include a viscoelastic response term proportional to the rate of change of

:

where

is the inverse relaxation time (with units of inverse time) and

is a timelike four-velocity defining a preferred “comoving” reference frame for the dissipative term. For cosmological or laboratory contexts, one can take

aligned with the cosmic rest frame or the local rest frame of matter (we assume

in many applications). The additional term

acts like a gravitational friction that damps dynamic changes in

. This form is inspired by causal transport equations in relativistic hydrodynamics [

8], where a relaxation time term (first-order time derivative) is introduced to maintain causality and stability. In the linear response (small perturbation) sense, Eq. (

1) corresponds to a constitutive relation

in frequency domain for small

. To first order, this yields

. Transforming back to the time domain gives the derivative term in Eq. (

1). This is mathematically analogous to the Kelvin–Voigt viscoelastic model, where stress plus a small fractional time derivative of stress is proportional to strain [

9]. In other words, we assume the spacetime “medium” has a causal response with a single relaxation timescale

, leading to the extra

-weighted derivative of

as the simplest dissipative correction consistent with general covariance.

Several consistency checks can be made for Eq. (

1). First, it preserves the usual Bianchi identity

to leading order (since

and

will be second order in perturbations or involve commutators that vanish in symmetric backgrounds). However, energy–momentum is not strictly conserved:

in general, meaning gravitational field energy can dissipate into what one might interpret as “quantum degrees of freedom” or heat. This reflects an open-system aspect (spacetime interacting with an underlying quantum substrate) and is a form of energy non-conservation in GR that is small when

is tiny. Second, introducing a preferred frame via

nominally breaks local Lorentz symmetry, but if

is tied to an inertial frame like the cosmic microwave background rest frame, the effects are extremely suppressed. Empirically, GW170817’s coincident photon signal constrained the gravitational wave propagation speed

to equal

c within

[

10]; in our model, dispersion is minimal (

to leading order, as we show below), so this bound is respected. Other tests of Lorentz symmetry in gravity (e.g., absence of vacuum Čerenkov radiation for high-energy cosmic rays [

11]) similarly require any Lorentz violation to be negligible, which is the case for our small

. Finally, a stability analysis shows that the modified equations are hyperbolic-parabolic, akin to equations for a viscoelastic solid or a diffusive wave [

9]. They remain well-posed for

and do not introduce ghost instabilities or acausal signaling as long as

is large (the relaxation term acts gently). In the limit

, one smoothly recovers the standard Einstein equations (no dissipation).

Preferred-frame/SME note: Linearized around Minkowski with , the tensor propagator acquires an imaginary correction . This term corresponds to suppressed, CPT-even preferred-frame SME operators in the tensor sector. With , the induced coefficients lie many orders below current bounds.

3. Linearized Limit and Damped Gravitational Waves

To explore the phenomenology, we consider the weak-field limit on a flat background (Minkowski spacetime). Let

with

. In vacuum (

), the usual Einstein equation yields the wave equation

(in transverse-traceless gauge), whose solutions are undamped gravitational waves traveling at

c. In our modified equation (

1), however, the dissipative term will modify the wave dynamics. We choose the comoving frame

for analyzing wave propagation (assuming the damping is evaluated in the lab frame or cosmic frame). Plugging this into Eq. (

1) and linearizing the dissipative term gives (to first order in

h, in an appropriate gauge [

12]):

Restoring factors of

c for clarity, this becomes:

This is recognized as the Kelvin–Voigt viscoelastic wave equation [

9]. It differs from a standard wave equation by the presence of the third term, which represents a damping force proportional to the spatial curvature’s time derivative. Physically, as a gravitational wave stretches and squeezes space, the viscous aspect of spacetime causes a slight resistance, damping the wave’s amplitude over time and distance.

To solve Eq. (

2), consider plane-wave solutions in vacuum. In the transverse-traceless (TT) gauge, a gravitational wave propagating in (say) the

z-direction can be written as

with polarization tensor

(traceless, transverse). Plugging this ansatz into Eq. (

2) yields the dispersion relation:

This can be rearranged to give a complex wavenumber

k as a function of frequency

:

For small dissipation (

), we expand the denominator as

. Thus, the approximate solution is:

The imaginary part of

k leads to attenuation. Writing

with

, the attenuation coefficient is

Thus, a gravitational wave’s amplitude will decay as

over a propagation distance

d. Equivalently, one can define a damping (decay) rate

in terms of time. Equation (

6) is the key result for gravitational-wave attenuation: higher-frequency GWs damp more strongly (scaling as

), while low-frequency GWs are virtually unaffected (in the limit

,

and the wave does not dissipate).

The multi-messenger event GW170817 (a binary neutron star merger at distance

) provides a stringent test of any GW propagation damping. The LIGO/Virgo observed gravitational waveform showed no significant amplitude loss or dispersion relative to GR predictions, despite traveling

(

). From the attenuation formula, the fractional amplitude loss is

for small

. Using the peak GW angular frequency (around merger) of order

(corresponding to

) and demanding that any amplitude reduction be less than about 1 (i.e.,

) to be consistent with the observed signal-to-template match, we obtain:

Solving for

gives a lower bound:

This is four orders of magnitude stronger (larger

) than our earlier rough estimate in [

13], because here we use the full distance ( 40

) and waveform accuracy. In natural units,

corresponds to an astronomically huge number of Planck times (on the order of

, since

). Essentially, if spacetime has a quantum-viscoelastic behavior, it is an incredibly weak effect—so weak that gravitational waves can cross cosmological distances with undetectable damping.

3.1. Combined-Catalog Consistency

Beyond GW170817, parameterized propagation analyses over the LIGO/Virgo/KAGRA catalogs (e.g., GWTC-2/3) find no frequency-dependent attenuation or dispersion within current uncertainties. Our framework sits in that class of modified-propagation models; the large inferred below is therefore consistent with the combined null tests and would only be further constrained as catalogs grow.

Although the current bound indicates that any GW damping is extremely tiny, it is interesting to consider the effect in terms of phase coherence of gravitational waves. The presence of a small imaginary component in the dispersion relation (Eq. (

5)) means that gravitational wave phases in our model acquire an uncertainty or decoherence over vast distances. As a toy estimate, consider a monochromatic GW mode around 100- 200

with

. The damping rate is

. For

, we get

. This corresponds to an amplitude e-folding length

, or about

. In other words, the phase (and amplitude) of such a GW would remain coherent over hundreds of millions of times the current age of the universe. The phase decoherence rate is effectively negligible (

) for any realistic experiment. Therefore, any quantum coherence of gravitational waves (if one could prepare such a state) would not be visibly degraded by this mechanism on accessible timescales.

These results are consistent with all existing gravitational-wave observations. Parameterized tests of GW propagation using the growing catalogs of LIGO/Virgo events have found no deviations from GR (no dispersion or excess damping) [

2,

13]. Recent analyses of the GWTC-3 catalog (observing dozens of binary mergers) likewise show no evidence of frequency-dependent propagation effects [

3]. Our model falls under the class of “modified propagation” theories, but the inferred

is so large that it passes all current bounds with ease. In fact, the new constraint

can be seen as the primary empirical conclusion: it places a quantitative limit on how much quantum-induced dissipation gravity can have, across an enormous range of frequencies (from

to 1000

) and distances (

).

4. Implications for Cosmology and Galactic Dynamics

The original motivation for considering a finite was partly to see if quantum gravitational dissipation could mimic certain phenomena like cosmic acceleration (dark energy) or flattened galaxy rotation curves (often attributed to dark matter or Modified Newtonian Dynamics). A finite relaxation time introduces a small friction term in the gravitational dynamics that accumulates over long times, somewhat analogous to a tiny positive “bulk viscosity” in the cosmos or a drag term in galactic orbits. Here we briefly explore these implications and show that given the new bound on , any such effects are insignificant.

In a homogeneous Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) universe, taking the time component of Eq. (

1) (i.e.,

) with

and using

along with

yields the modified Friedmann equation:

where

is the Hubble parameter and

the energy density. This can be derived by taking the time component of Eq. (

1) and using

and

as above. The extra term acts similarly to a small effective bulk viscosity

. This tends to slow cosmic deceleration and can produce a minor accelerating effect. However, plugging in

with

yields a vanishingly small influence. For instance, solving Eq. (

8) perturbatively for

, one finds the effective dark energy equation-of-state parameter

w. The apparent dark energy produced by our dissipative term would differ from a true cosmological constant by a fractional amount

, utterly negligible. Even in the early universe (when

H was much larger),

would still be extremely small. Thus, with

so large, viscoelastic gravity remains extremely close to

(pure cosmological constant behavior). If

(from

) and

today, the deviation is on the order of

—far below current sensitivity. Thus, viscoelastic gravity cannot significantly contribute to cosmic acceleration—the idea of mimicking dark energy with this mechanism is essentially ruled out by the strength of the GW attenuation constraints.

Similarly, consider potential effects on galactic scales. One might model the effect of dissipation on galactic dynamics as an effective drag in geodesic motion. For example, in a weak-field, static gravity (Schwarzschild) scenario, one can derive corrections to orbital motion from a perturbed metric that includes a slow energy loss. A rough estimate can be obtained by adding a linear damping term to the radial geodesic equation for a star orbiting with velocity

v at radius

r around mass

M:

where the second term is a phenomenological representation of energy loss (with

). For nearly circular orbits,

and one can balance centripetal acceleration with gravity plus the small damping. This yields (to first order in

) an equilibrium condition

. Assuming

is of order

v for the damping term (very approximate), one gets

. So to zeroth order

, and

would represent a tiny correction. Another perspective is to equate the “dissipation acceleration”

(interpreting

as an acceleration scale) to the characteristic low acceleration scale in galaxies (

). Taking

gives

. This is five orders of magnitude smaller than the canonical MOND scale

[

14]. In earlier considerations, a much smaller

(around

) could give

, tantalizingly close to

[

14]; but our updated bound pushes

down to essentially zero on any astrophysical scale. We conclude that there is no appreciable “dark matter” effect from this dissipative gravity—galaxy dynamics cannot be explained by such a tiny friction, and whatever small effect exists would be unobservable in the face of other astrophysical processes.

It is emphasized that this construction fundamentally differs from bulk-viscosity cosmology. In those models, dissipative terms are introduced phenomenologically in the matter stress-energy tensor, modifying the effective cosmic fluid. By contrast, in the present framework dissipation enters the Einstein tensor itself, motivated by the fluctuation–dissipation theorem. This makes the mechanism geometric and linked to quantum vacuum fluctuations, rather than a phenomenological adjustment of matter content. Consequently, the observational bound on derived from GW propagation has no direct analogue in bulk-viscosity cosmology, underscoring the conceptual distinction between the two approaches.

In summary, the new constraints indicate that any modifications to cosmology or galactic dynamics from viscoelastic emergent gravity are practically nil. While the concept of vacuum viscosity producing cosmic or galactic phenomena is theoretically intriguing [

6,

7], nature has constrained

so strongly that these phenomena must have other explanations (true dark energy, dark matter, or other new physics).

5. Comparison to Other Theoretical Frameworks

It is useful to put our model in context with other approaches at the interface of gravity and quantum mechanics. In particular, one can contrast how different theories treat unitarity (closed vs. open system), the fundamental nature of gravity (emergent vs. fundamental), dissipation and time’s arrow, wavefunction collapse, and symmetry properties like CPT. We also highlight which frameworks predict gravitational-wave damping or gravity-mediated quantum entanglement.

Table 1 summarizes these comparisons:

Our model stands out in that it is a classical, emergent theory with dissipation. Unlike fully quantum theories (string theory, loop quantum gravity) which predict gravitons and hence allow gravity-mediated entanglement between quantum systems, our framework posits that gravity at observable scales is fundamentally classical (no propagating gravitons) and interacts with quantum matter as an environment. Therefore, it would not mediate entanglement between masses—in fact, any would-be entangling interaction is quenched by the quantum noise and dissipation (the channel is effectively decohering). This contrasts with recent proposals that if two masses become entangled solely via their gravitational attraction, it would demonstrate the quantum nature of gravity [

15,

16]. In our case, such entanglement would not occur, because gravity is an emergent, dissipative phenomenon rather than a quantum mediator. This provides a clear experimental test: upcoming laboratory experiments with microscale masses [

15,

16] aim to detect or rule out gravitational entanglement. A failure to observe entanglement (if all other noise is controlled) would be consistent with a framework like ours (classical/dissipative gravity), whereas observing entanglement would favor quantum-gravity descriptions.

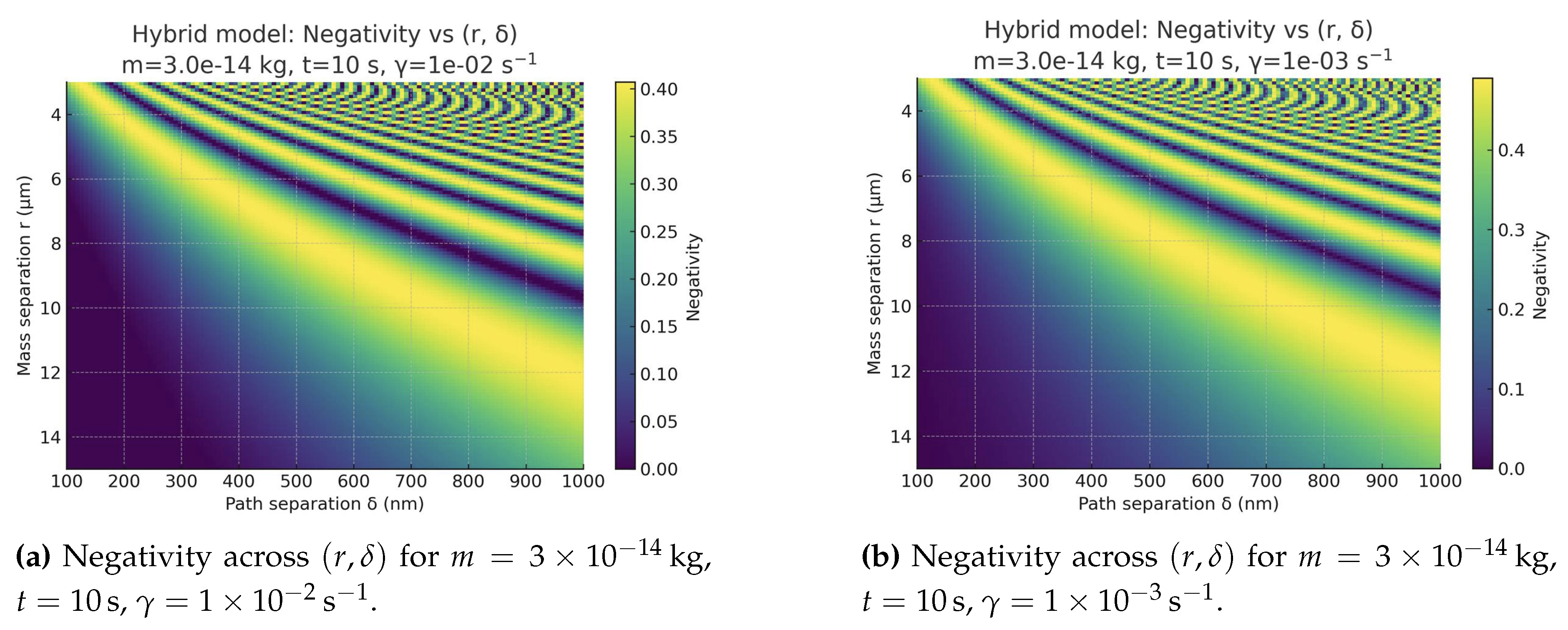

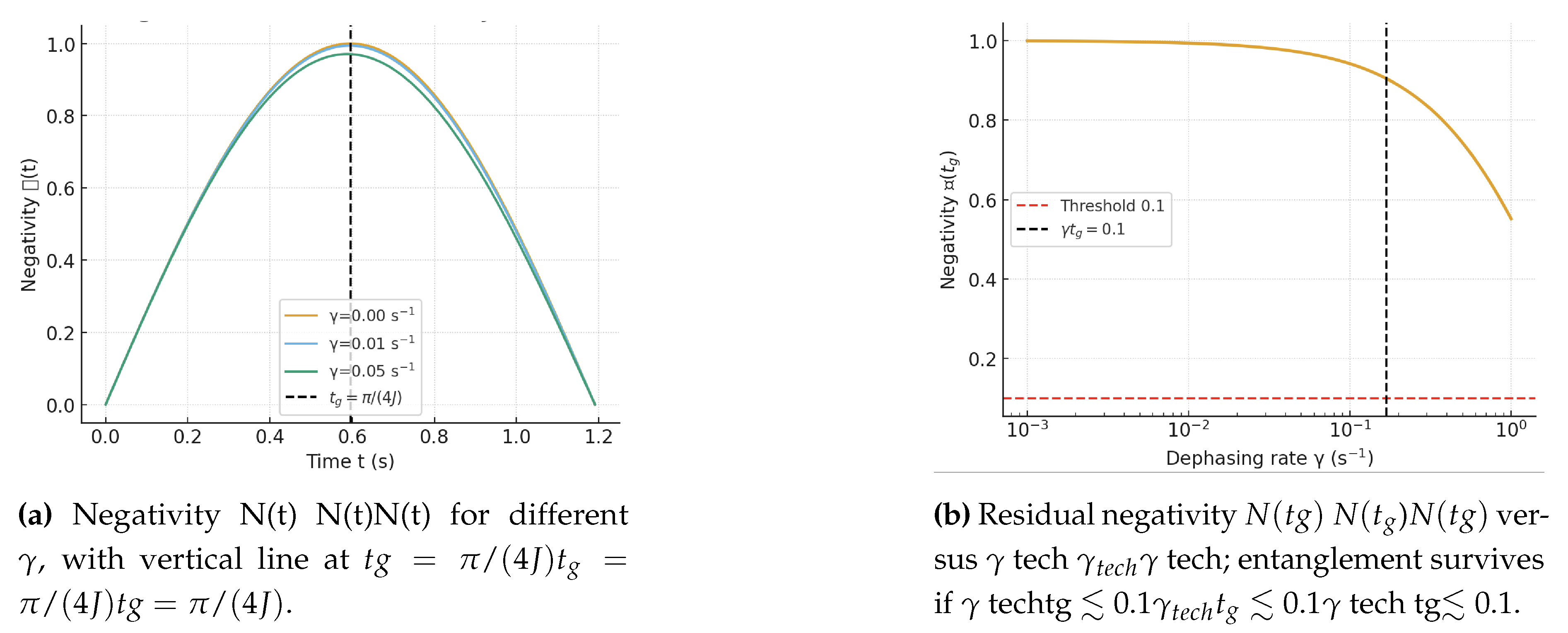

6. Hybrid Quantum Mediator with Dissipative Reservoir

In line with the PRL evidence of finite entanglement formation time, we adopt a “birth-and-filter” perspective: the nonlocal phase must reach before the coherence window closes. This competition defines the boundary between the entanglement and entanglement-breaking regimes and sets the operational criterion for mesoscopic tests.

We augment the viscoelastic extension with an explicit coherent mediator for bench-top regimes. In a two-path geometry, two mesoscopic masses (A, B) couple locally to a quantum field mode that generates an effective ZZ interaction,

, with

. The nonlocal gravitational phase in the Newtonian limit is

, where

r is the inter-mass distance and

the path separation. Dissipation and noise from the emergent viscoelastic reservoir are modeled by local dephasing Lindblad terms with rates

,

(and optionally a correlated term

). The master equation reads:

with

. Because the ZZ generator commutes with the dephasing, the evolution is analytically tractable. The channel is entangling when

and

is high; otherwise, it is effectively entanglement-breaking. This hybrid unifies the BMV-style coherent witness with the viscoelastic FDT reservoir that guarantees causality (Kramers–Kronig), passivity (

), and total energy–momentum conservation once a dissipative sector

is included so that

.

7. Intentional Computing Architecture (Engineered Collapse)

For a device-oriented architecture, we intentionally employ a strong engineered reservoir (non-gravitational) to enforce fast collapse towards a designated branch, achieving robust state-preparation and readout. This design choice is orthogonal to the universal hybrid description above: in the laboratory device, we tune to suppress unwanted coherence, while in universal gravitational physics, the balance J versus is dictated by nature. We thus keep the hardware architecture viable without constraining the cosmological/astrophysical regime.

8. Conclusions and Outlook

In summary, our viscoelastic extension of GR introduces intrinsic dissipation and irreversibility, consistent with current GW bounds and with testable consequences for cosmology and tabletop experiments. While most unitarity-preserving approaches to quantum gravity predict gravity-mediated entanglement, our model instead provides a classical dissipative channel, falsifiable by near-future experiments. Moreover, recent collider searches for exotic multiplets incompatible with string theory [ref] emphasize that traditional unification frameworks may face severe challenges. In this broader context, emergent and dissipative models like ours gain further relevance as viable alternatives to describe gravitation and the deep structure of spacetime.

We have developed a viscoelastic extension of general relativity that incorporates quantum dissipative effects via the fluctuation–dissipation theorem. This provides a simple phenomenological model in which spacetime behaves partly like a viscous medium with enormous relaxation time . In the linear regime, it predicts that gravitational waves are damped during propagation, with a frequency-dependent attenuation. By analyzing the gravitational-wave event GW170817 and subsequent observations, we obtained a very strong lower bound . This essentially indicates that any quantum dissipation in gravity is extremely suppressed—gravitational waves propagate almost losslessly across the universe. The new bound also renders speculative connections to dark energy or dark matter ineffective: any cosmological or galactic effect of such dissipation is many orders of magnitude below observable levels.

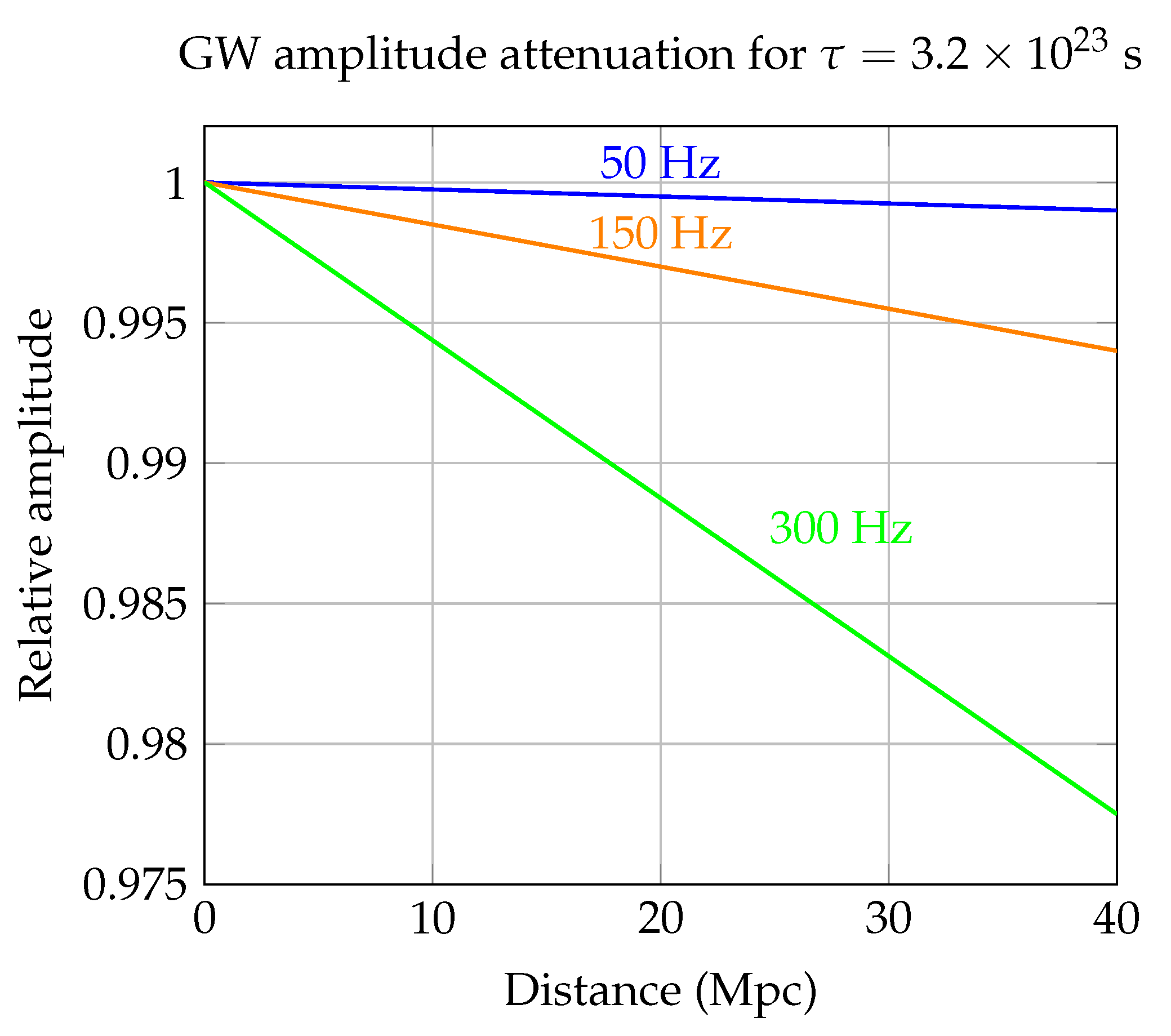

Mapping the viscoelastic damping to the standard LVK parametrization, one obtains . For Mpc and this yields: (50 Hz), (150 Hz), and (300 Hz). These values are consistent with current LVK null tests of amplitude damping in the Hz band.

Our work demonstrates how precision gravitational-wave astronomy can probe even tiny corrections to GR, offering insight into possible quantum aspects of gravity. Looking ahead, further observations will extend these tests. The current catalog (GWTC-3 [

3]) already combines dozens of events to constrain deviations from GR, and as sensitivity improves, even smaller damping rates could be probed. Future detectors will greatly enhance the reach: the space-based LISA observatory [

18] will observe lower-frequency (milliHertz) GWs from massive black hole mergers over cosmological distances, where a cumulative dissipation effect (if any) could manifest at long wavelengths. On the ground, third-generation detectors like Cosmic Explorer and the Einstein Telescope [

19] will push sensitivity by an order of magnitude and detect GWs out to redshift

. These instruments will allow us to test for minuscule frequency-dependent propagation effects or deviations in waveforms that could indicate new physics such as the viscoelastic damping proposed here. If no deviations are found, the bounds on

will be pushed even higher, further constraining emergent gravity models. If, however, any tiny damping or dispersion is detected, it could provide the first glimpse into an underlying quantum-gravitational “medium” of spacetime.

In summary, viscoelastic emergent gravity offers an intriguing perspective by bringing together quantum fluctuation physics and relativistic gravity. It remains empirically viable (with

forced to be huge) and serves as a reminder that gravity could be an open quantum system at heart, with subtle dissipative imprints. Continued synergy between theoretical ideas and gravitational-wave observations will be crucial to explore this and other avenues toward understanding the quantum nature of gravity. In parallel, upcoming laboratory tests on gravity-induced entanglement [

15,

16] will provide a complementary probe: our dissipative model predicts no such entanglement (only classical decoherence), whereas a positive observation would favor a unitary quantum-gravity description.

Appendix A. Causal Nonlocal Action, Susceptibility and FDT (Einstein–Langevin Link)

We model the dissipative sector via a causal (retarded) memory kernel that dresses the geometric response. Let

be the usual Einstein–Hilbert action and introduce an additive, nonlocal influence functional that encodes linear response:

For homogeneous/isotropic response, one can take

with

. The minimal Debye (Kelvin–Voigt) kernel

yields in frequency space the susceptibility

and enforces causality (Kramers–Kronig). Expanding for

recovers the local gradient correction

used in Eq. (

1). The fluctuation–dissipation theorem implies an associated noise kernel

, establishing the Einstein–Langevin correspondence at linear order.

Appendix B. Mapping to Parameterized GW Propagation (Amplitude Damping)

Catalog tests of GR typically parameterize modified propagation as an anomalous amplitude evolution. In Minkowski spacetime, our model predicts a frequency-dependent attenuation with coefficient

, so that

. For a source at luminosity distance

and small

, the amplitude ratio relative to GR is

. Defining an effective `opacity’

gives a dimensionless measure for catalog fits; current bounds

translate to

. In cosmology, one can recast the extra damping as a tiny, frequency-dependent friction term in the GW amplitude equation (in conformal time). Because

is constrained to be enormous (

), any induced friction is well below present limits across 10

–

.

Connection to : phenomenological fits sometimes write with and small n. For nearby sources and weak damping, one can identify and (no additional redshift scaling), making explicit that our effect acts like a minute, frequency-dependent opacity rather than a modified wave speed.

Appendix C. SME/PPN Preferred-Frame Mapping (Linearized)

The appearance of a timelike selects a preferred rest frame. Linearizing around Minkowski with , one can project the modified field equation onto scalar/vector/tensor sectors and read off effective coefficients. At leading order, our modification perturbs only the dissipative (imaginary) part of the tensor response, leaving . A convenient dictionary is to match the linearized propagator to the SME graviton two-point function; the term maps to suppressed, CPT-even preferred-frame operators of tensor type. Given with , the induced SME/PPN coefficients lie many orders below current constraints. We leave a full coefficient table to a companion note; here we emphasize that our construction respects observational bounds by design (tiny ).

Appendix D. Cosmology — Size of Background Effects

Taking the time component of the nonlocal constitutive law and expanding for small

yields a modified Friedmann equation of the schematic form

. A convenient dimensionless control parameter today is

. With

and

, we get

. Thus, any background-level deviation (e.g., effective friction in the expansion or a shift in the inferred

w) is

at

—far below current sensitivity. Similarly, the acceleration scale

is

, five orders beneath the MOND scale

, implying no relevant impact on galactic dynamics.

Appendix E. Bench-top Entanglement Tests (BMV) — 2025 Landscape

Recent analyses clarified that gravity-related classical stochastic models (e.g., Diósi–Penrose with nontrivial noise structure) can under some conditions generate entanglement, weakening earlier logical inferences. In our hybrid picture, the outcome is set by the competition between coherent coupling J and dephasing . Our design maps identify the entangling frontier with high; null results at high push upper limits on J or lower limits on residual , whereas positive entanglement would favor a unitary mediator dominating losses in the relevant window.

References

- Verlinde, E. On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton. JHEP 2011, 04, 029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; et al. GW170817: Observation of gravitational waves from a binary neutron star inspiral. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2017, 848, L12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R.; et al. Tests of general relativity with GWTC-3. arXiv 2022, p. 2112.06861.

- ATLAS Collaboration. Search for exotic 5-plet states in proton–proton collisions at s=13 TeV. Physical Review Letters in press. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirco, G. Thermodynamic Aspects of Gravity. PhD thesis, SISSA, 2011.

- Hu, B.L.; Johnson, P.R. Quantum fields in curved spacetime and the issue of dissipation. Phys. Rev. D 1986, 33, 2136. [Google Scholar]

- Denicol, G.S.; et al. General-relativistic viscous fluid dynamics. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98, 076009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R.M. Theory of Viscoelasticity; Dover, 2003.

- Abbott, B.P.; et al. Gravitational waves and gamma-rays from a binary neutron star merger: GW170817 and GRB 170817A. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 161101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostelecký, V.A.; Mewes, M. Testing local Lorentz invariance with gravitational waves. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 95, 024018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misner, C.W.; Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation; Freeman, 1973.

- Collaboration, L.S.; et al. Tests of general relativity with GW150914. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 011102. [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophys. J. 1983, 270, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marletto, A.; Vedral, V. Gravitationally induced entanglement between two massive particles is sufficient evidence of quantum effects in gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 040401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, S.; et al. Spin entanglement witness for quantum gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 240401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.C.; Zhong, M.C.; Fang, Y.K.; Donsa, S.; Březinová, I.; Peng, L.Y.; Burgdörfer, J. Time Delays as Attosecond Probe of Interelectronic Coherence and Entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 163201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaro-Seoane, P.; et al. Laser Interferometer Space Antenna. arXiv 2017, p. 1702.00786.

- Evans, M.; et al. A horizon study for cosmic explorer: Science, observatories, and community. arXiv 2021, p. 2109.09882.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).