1. Introduction

High-density cities in subtropical hot-humid regions are increasingly challenged by intensifying heatwaves driven by urbanization and climate change [

1,

2]. The urban heat island (UHI) effect poses serious threats to human health, environmental quality, and vegetation growth [

3,

4]. Among UHI mitigation strategies, nature-based solutions (NbS) have received substantial research attention [

5]. A natural, low-cost and sustainable ecological approach is to leverage the evapotranspiration, albedo and shading effects of urban trees to achieve effective temperature cooling and thermal comfort improvement [

6,

7,

8]. While numerous studies highlight the shading effect of trees in alleviating heat stress [

9], the wind regulation mechanisms of individual trees and tree configurations with different morphologies remain less explored.

Wind is widely recognized as a critical factor in mitigating UHI intensity [

10]. Trees interact with wind by generating turbulence through canopy morphology and by modifying near-surface wind speed through their spatial configuration [

11,

12,

13]. Only sufficiently strong winds can prevent localized heat accumulation, as three-dimensional turbulence enhances advective heat transport [

14]. Conversely, even a modest increase in wind speed can significantly improve pedestrian thermal comfort [

15].

In wind and heat environment studies, mesoscale and microscale are two commonly adopted analytical levels [

3,

14]. According to the American Meteorological Society’s Glossary of Meteorology, the mesoscale refers to a horizontal range of 2–2000 km, whereas scales below 2 km are defined as microscale [

16]. Together, these scales describe the distribution of wind and heat across urban areas, from districts to blocks and down to the pedestrian level, each with distinct formation mechanisms and complex interactions [

17]. Mesoscale circulations are induced by pressure differences associated with UHI, shaped by prevailing winds and convective air currents at the tropospheric boundary [

18]. Urban structures and surface roughness further modulate these prevailing winds, creating diverse local wind environments [

14]. At the vertical level, research in Hong Kong has shown that podium-level (0–15 m) air permeability strongly influences urban ventilation and determines wind speeds at the pedestrian level (≈2 m) [

19]. In this context, wind at treetop height (≈5 m) affects airflow conditions and heat distribution at the block or mesoscale, whereas wind at 1.5 m directly governs convective heat exchange in the human microenvironment [

20,

21,

22].

Accordingly, examining wind speed at 5 m is essential for understanding block-scale heat accumulation, pollutant dispersion, and ventilation potential, while investigating wind regulation at 1.5 m is critical for improving pedestrian-level thermal comfort. However, most existing studies focus either on pedestrian thermal comfort at 1.5 m [

20,

21], or on ventilation at the canopy or urban scale [

18,

23]. , with limited attention to the differentiated effects of individual trees and tree groups across these two heights.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has proven to be an effective and flexible tool to simulate wind speed variations in urban environments [

14,

22]. It is widely applied to model buoyancy-driven flows in street canyons and to evaluate pedestrian thermal comfort, using platforms such as ANSYS, ENVI-met, and OpenFOAM [

24]. Although urban buildings are typically the dominant focus of CFD simulations, the aerodynamic effects of trees are equally important and warrant further investigation [

13,

16,

23,

25]. Among available CFD tools, WindPerfect DX offers specialized functions for modelling airflow and assessing the impacts of vegetation on the urban wind environment [

26]. Previous studies have explored tree impacts through variations in species, canopy diameter, bole length, porosity, and leaf area index (LAI) [

27,

28,

29]. However, these studies are often practice-oriented, providing planning guidelines [

30,

31], rather than systematically examining the micromechanical processes by which trees influence airflow.

To address this gap, the present study aims to elucidate the mechanisms by which tree crown morphology and layout regulate wind at different heights. Specifically, the objectives are to: 1) establish a parameterized CFD model based on typical crown morphologies (ellipsoidal, cylindrical, and conical) in a high-density, hot-humid city; 2) explain the differentiated effects of crown morphology and planting layout on wind at low altitude (≈5 m) and pedestrian height (≈1.5 m); and 3) propose tree-planting strategies for different planning scenarios (ventilation enhancement vs. wind protection) based on these mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

This study focuses on Macau, a high-density urban area located on the southeastern coast of China, which faces significant challenges related to UHI due to its limited land area, dense population, and scarce green spaces [

32,

33]. Situated in a hot-humid region, Macau experiences prolonged, extreme summer heat that imposes considerable stress on public health [

2,

34]. The summer season in Macau spans from June to September, as defined by the 25th-75th percentile thresholds [

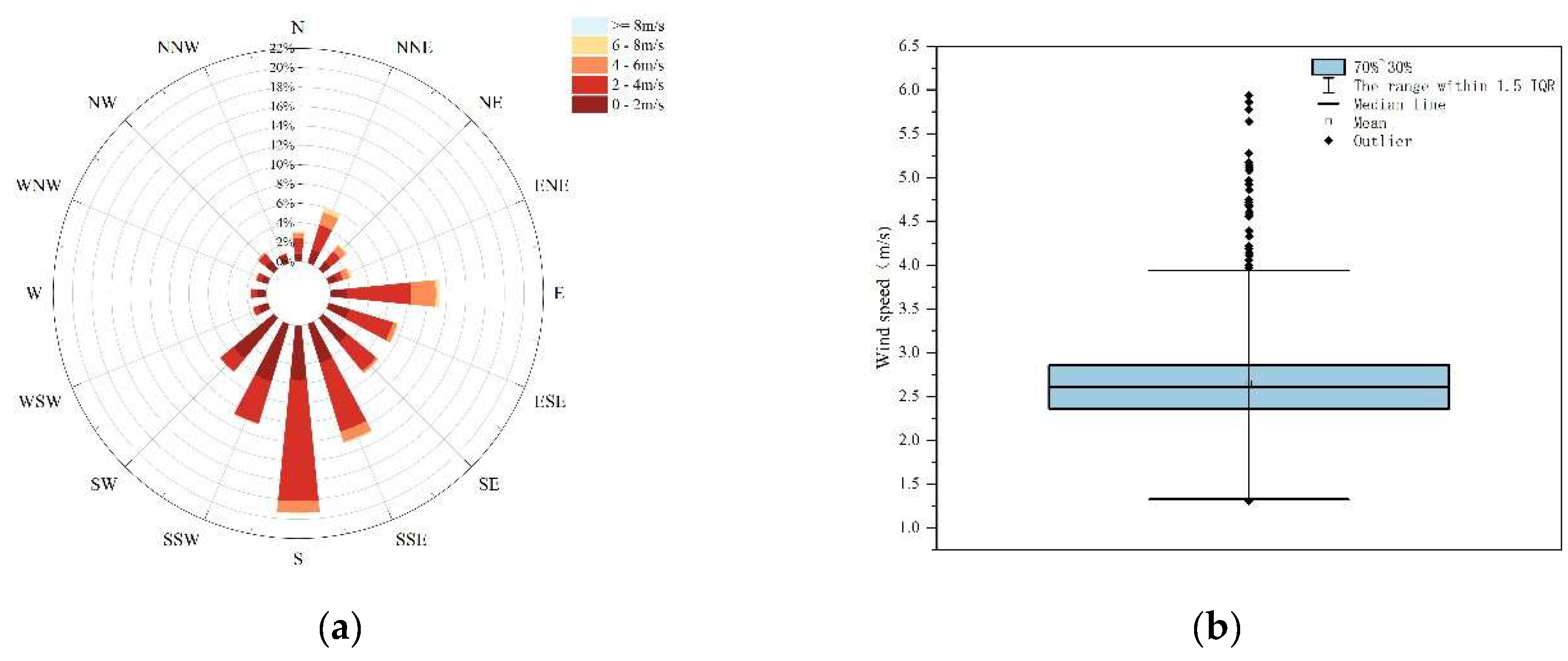

32]. According to records from the Macao Meteorological and Geophysical Bureau (2012–2021), the prevailing wind direction during the summer months is southerly, with wind speeds predominantly ranging from 2.36 to 2.86 m/s, as determined by the 30%-70% percentile thresholds (

Figure 1).

In Macau, street and park vegetation primarily consists of small- to medium-sized tree species (

Figure 2). While these trees provide limited shade, their impact on the wind environment remains insufficiently explored. In this compact and tourism-oriented city, the morphology and spatial arrangement of trees are particularly important for balancing aesthetic value with ecological cooling benefits. Therefore, this study adopts typical small- to medium-sized tree morphologies and the average summer wind speed as the basis for the numerical simulation.

2.2. CFD Simulation

To evaluate wind variation at different heights around tree crowns, this study employed WindPerfect, a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model designed for airflow simulation [

35]. The model uses a Cartesian finite volume method on structured grids, with a user-friendly interface for pre-processing and post-processing [

35,

36]. WindPerfect has been widely applied in thermal and wind environment studies [

13,

32].

Three common tree crown morphologies were selected for this study: ellipsoidal, cylindrical, and conical (

Table 1). These tree types represent species commonly found in Macau, such as Ficus variegata var. chlorocarpa, Syzygium cumini var. caryophyllifolium, and Cedrus atlantica, and are frequently used in urban settings like streets, parks, and courtyards. Corresponding planting configurations included single tree planting, paired planting, single row, double row, circular, and curved planting styles (

Table 2).

WindPerfect simplifies wind environment analysis for both small-scale and large-scale models using a four-step workflow. First, the tree model is imported in STL format. Next, meshing is applied to accurately capture wind resistance and acceleration around the tree. A 5m x 5m horizontal grid around the tree crown is divided into approximately 100 cells, with a grid resolution of 0.05m. For the vertical areas, 50 grid cells are used in a 2m zone around the trunk, and 100 cells in a 4m zone around the crown, resulting in a vertical grid resolution of 0.04m. A focal grid refinement method is employed, with grid size gradually increasing from the center outward, yielding a total grid count ranging from 7,011,900 to 17,523,000 cells. The wind direction is set to south, with the inflow wind speed set to 2.9 m/s at the same height as the weather station (10 meters). The 2.9 m/s wind speed, which corresponds to the 70th percentile of Macau Meteorological Station’s long-term observations, represents typical medium-to-high wind conditions, providing a more reliable and significant representation of wind speed variations and minimizing the impact of extreme events. Finally, the simulation is performed.

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Tree Crown Morphology on the Wind Environment

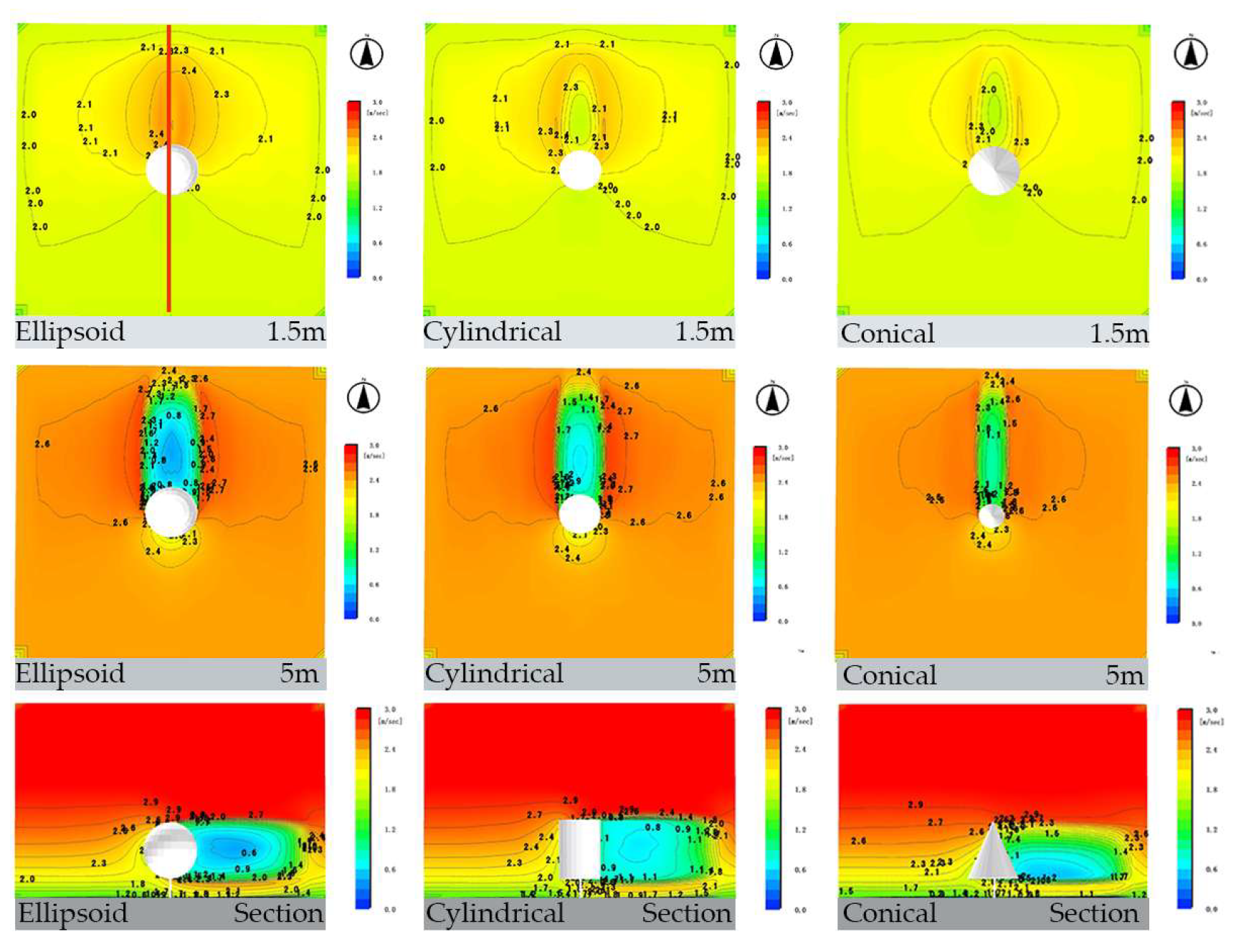

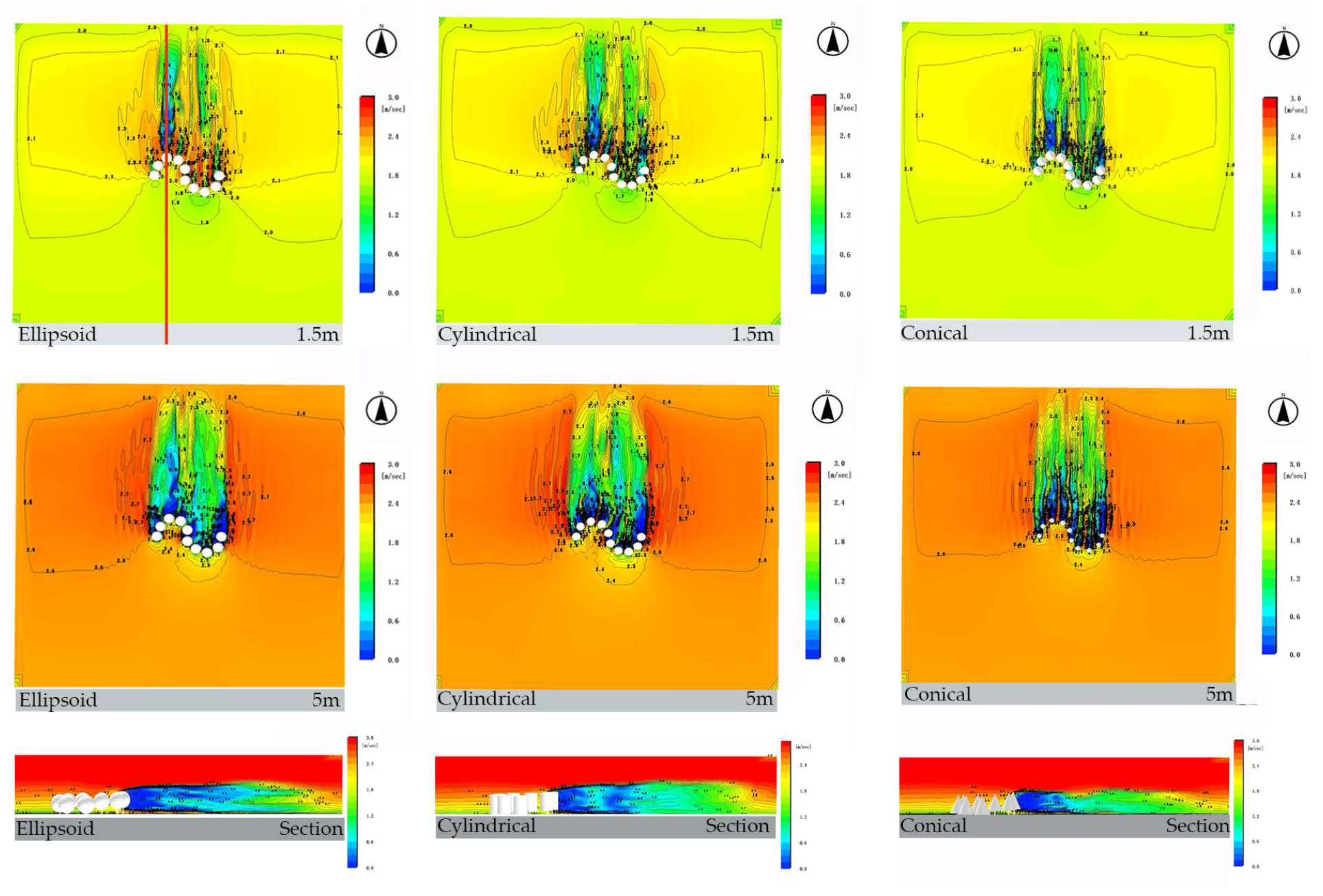

From

Figure 3 and 4, it can be observed that at the pedestrian height of 1.5 m, different canopy morphologies exert distinct influences on wind speed. The ellipsoidal canopy results in the highest downstream wind speed, exhibiting a pronounced enhancement effect. The cylindrical canopy produces intermediate wind speeds; due to its uniform radial dimensions and larger blocking area, it causes moderate attenuation as the wind passes through. In contrast, the conical canopy, with its narrow apex and broad base, further reduces wind speed at this height. At 15 m downstream of all three canopy types, the wind speed recovers to the inflow value of 1.9 m/s.

Figure 3.

This is a table. Tables should be placed in the main text near to the first time they are cited.

Figure 3.

This is a table. Tables should be placed in the main text near to the first time they are cited.

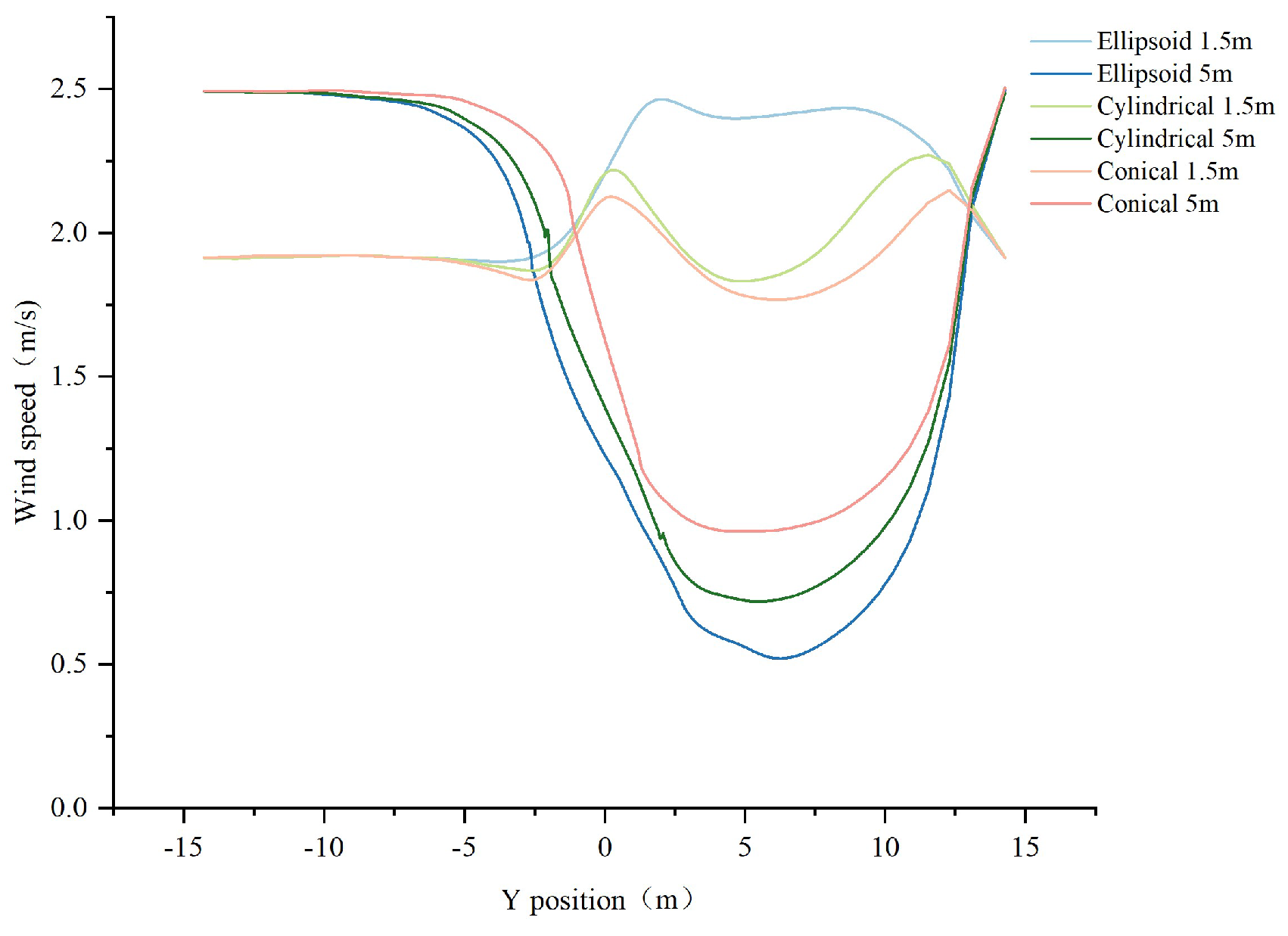

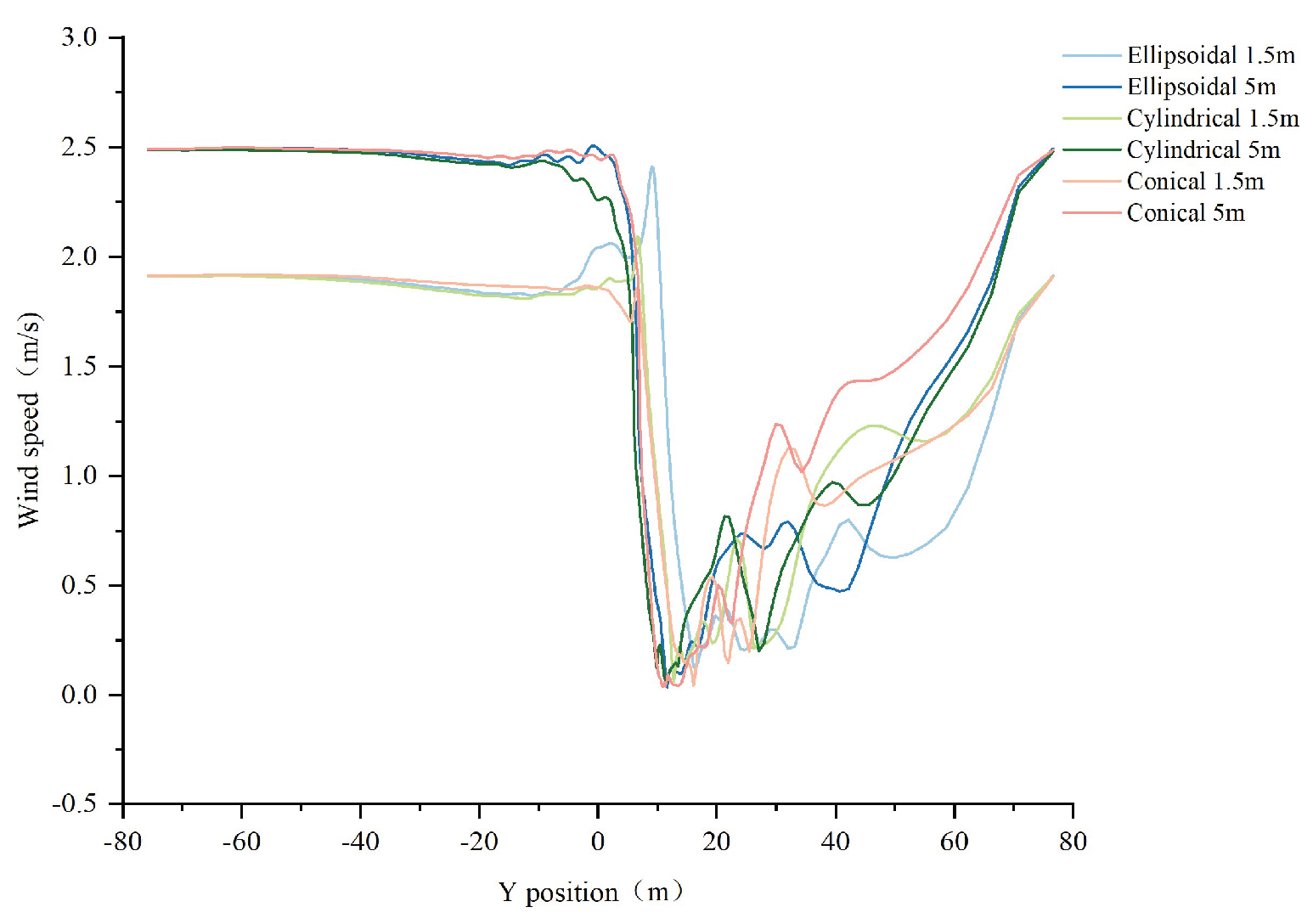

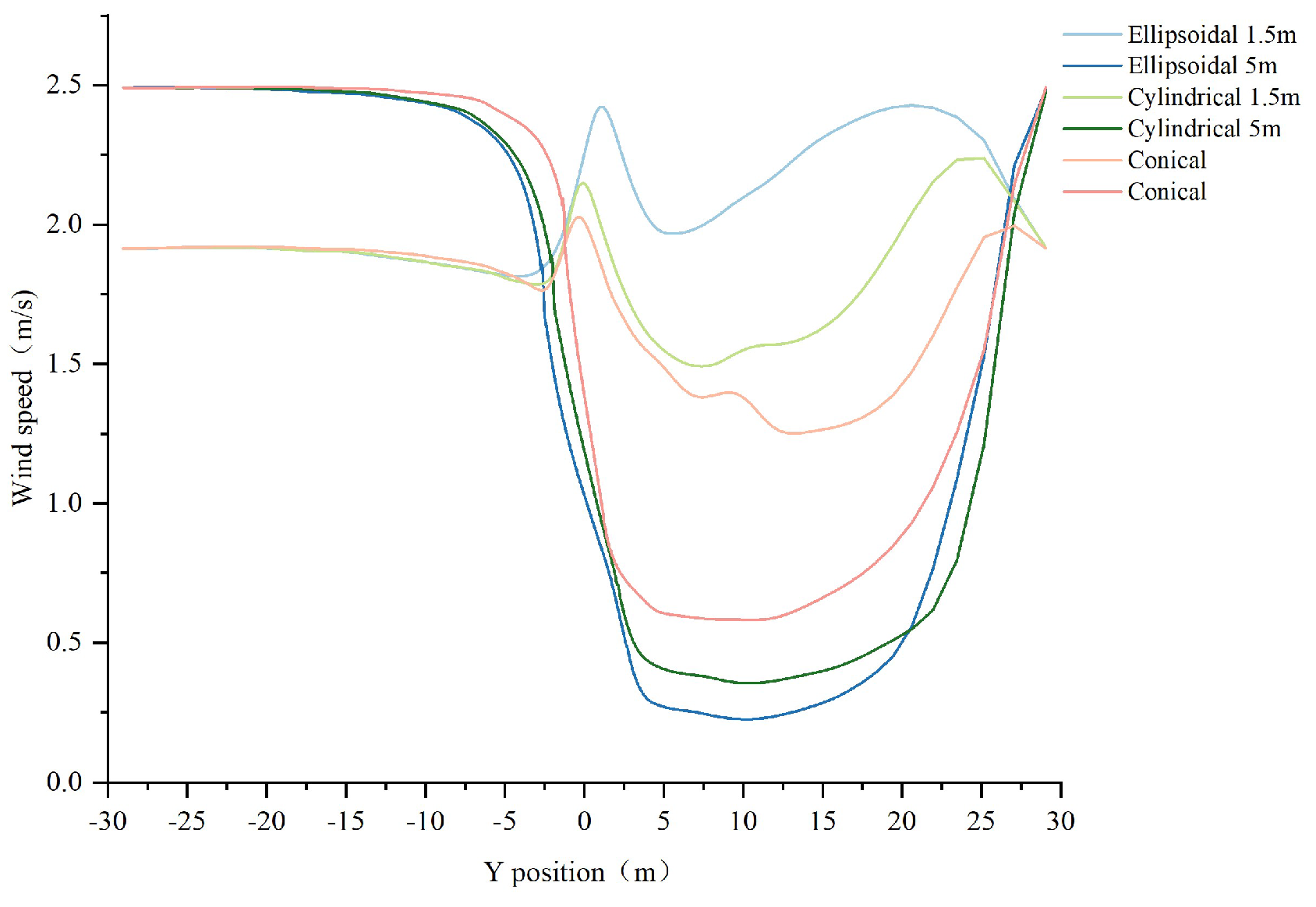

Figure 4.

Line chart of crown shape and wind speed.Wind speed was obtained at 1.5 m (X=0, Y=–15-15, Z=1.5) and 5 m (X=0, Y=–15-15, Z=5).

Figure 4.

Line chart of crown shape and wind speed.Wind speed was obtained at 1.5 m (X=0, Y=–15-15, Z=1.5) and 5 m (X=0, Y=–15-15, Z=5).

At 5 m height, wind speed differences are likewise significant. The ellipsoidal canopy exhibits the strongest reduction effect, followed by the cylindrical, while the conical canopy produces the weakest attenuation. When the incoming flow interacts with the middle section of the canopy, the ellipsoidal form imposes the greatest obstruction to the upper airflow, leading to the most pronounced reduction in wind speed. The cylindrical canopy, owing to its uniform shape, causes a relatively balanced weakening effect, whereas the conical canopy, with a substantially reduced radial dimension at this height, imposes comparatively weaker resistance. Locally, at approximately 5 m behind the trees, the wind speed reaches its minimum values of 0.52 m/s, 0.72 m/s, and 0.96 m/s for ellipsoidal, cylindrical, and conical canopies, respectively. By 15 m downstream, wind speed gradually recovers to the inflow level.

These variations in wind speed distribution across vertical layers clearly demonstrate that canopy morphology exerts a significant regulatory effect on the vertical characteristics of wind flow.

3.2. Impact of Tree Planting Layout on the Wind Environment

3.2.1. Opposite Tree Planting

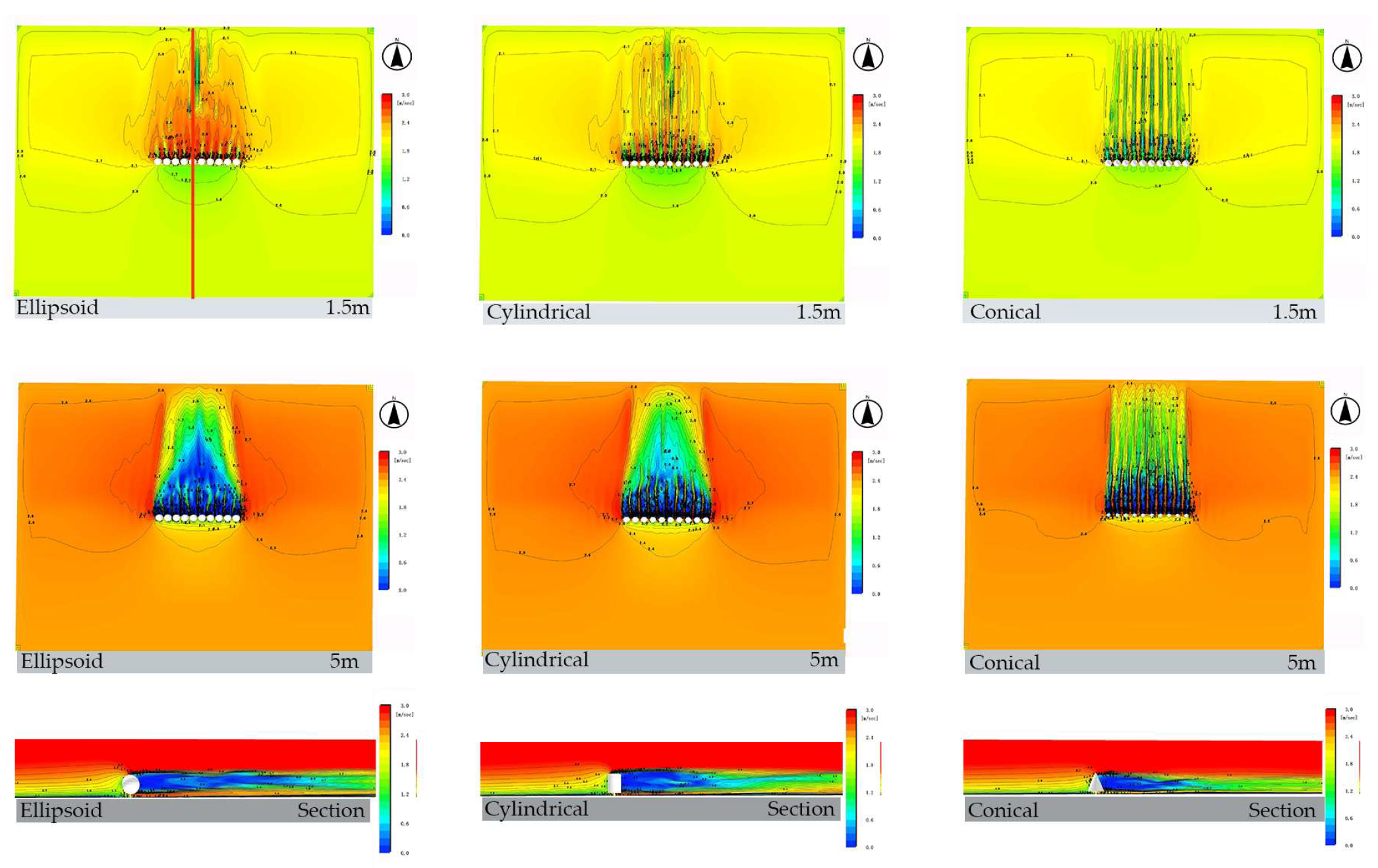

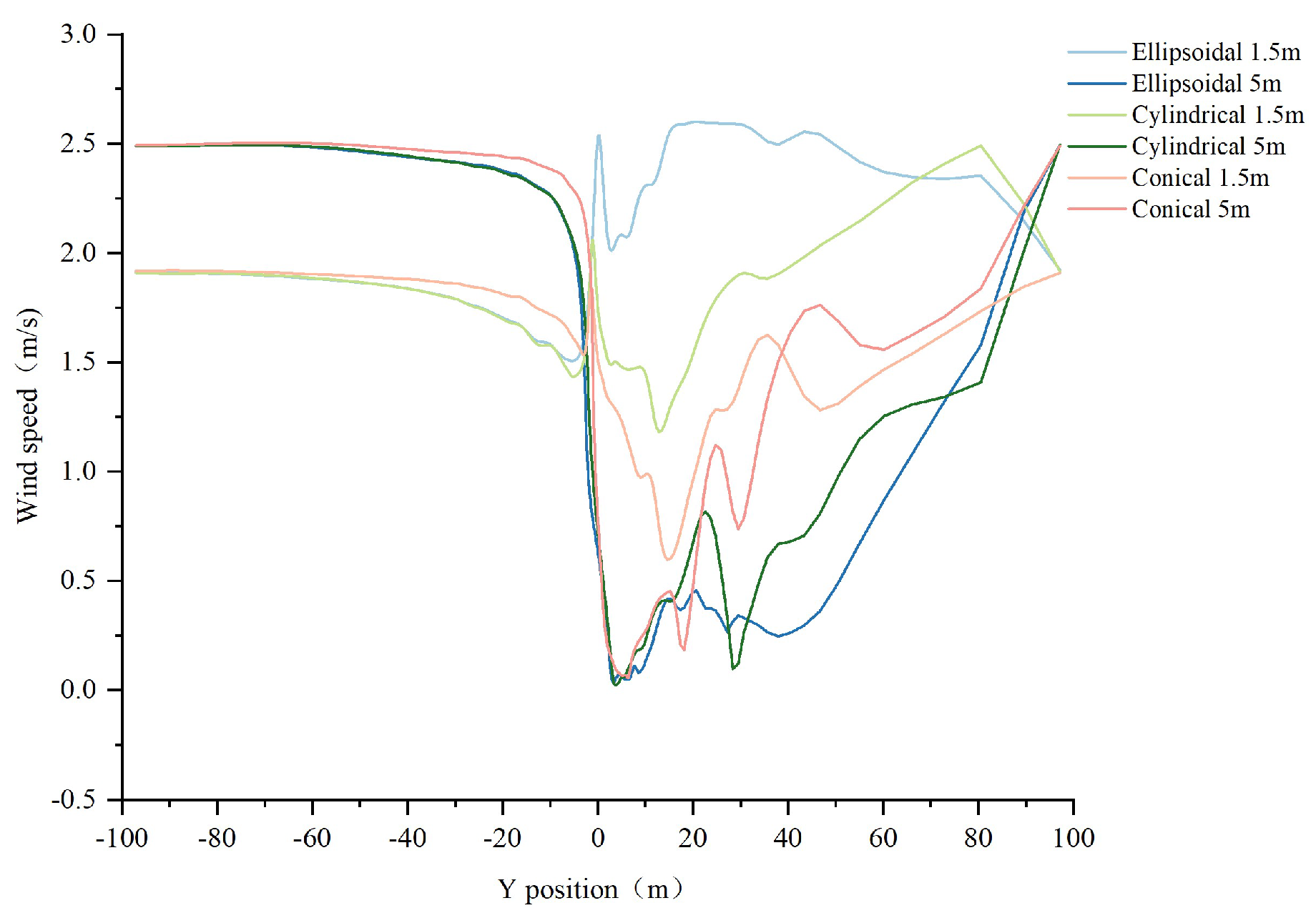

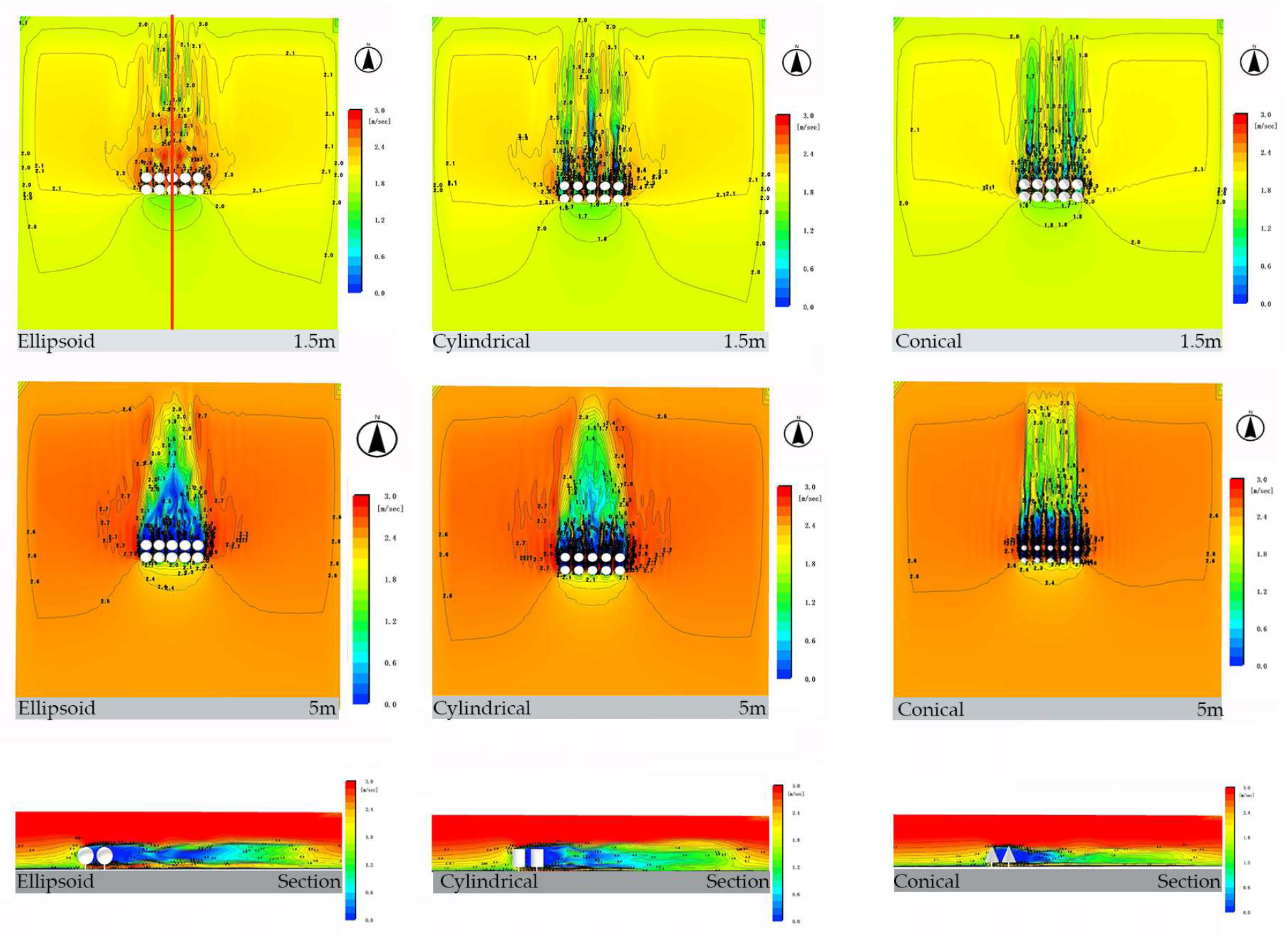

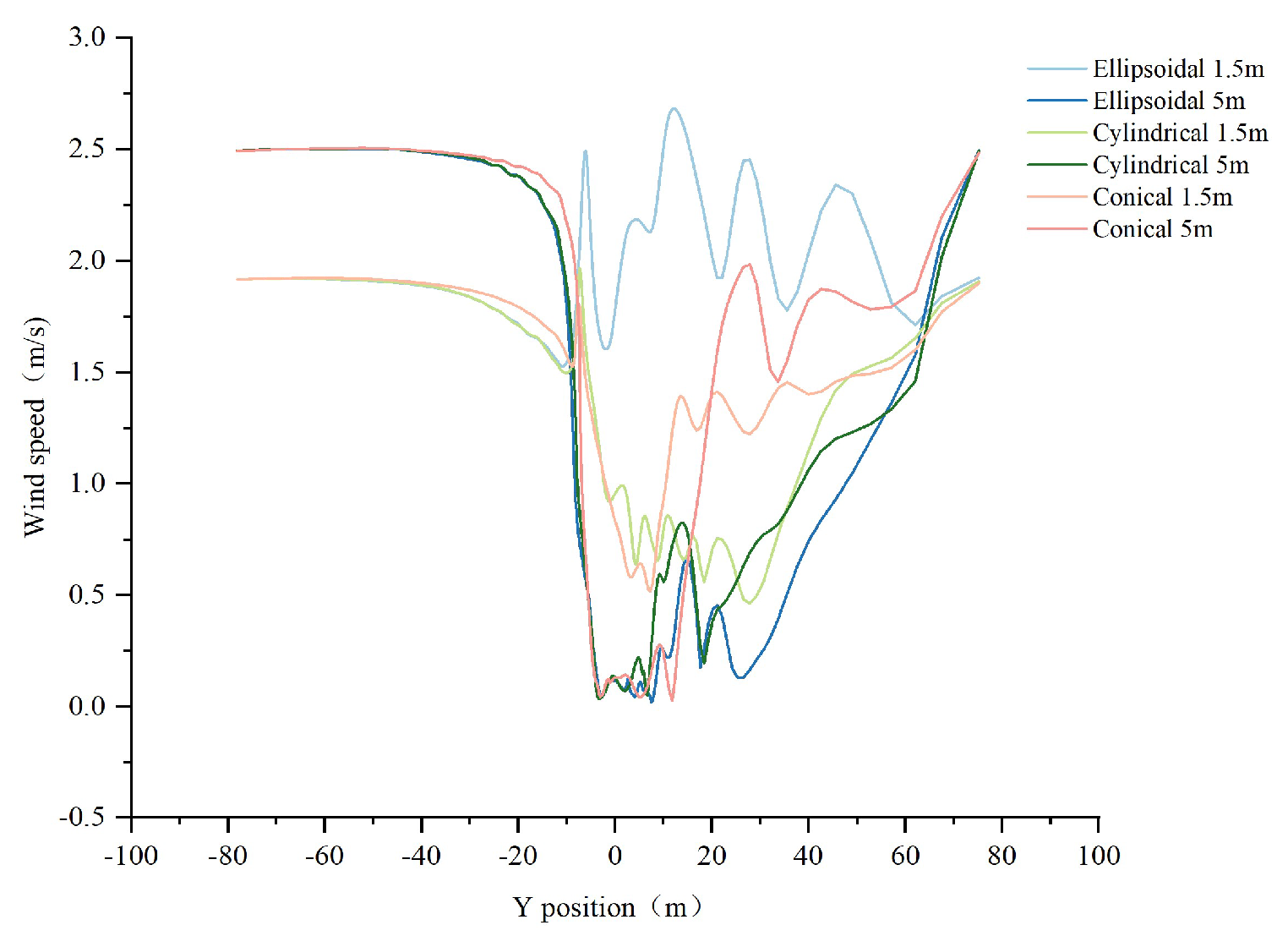

As shown in the simulation results (

Figure 5) and wind speed distribution (

Figure 6), a transient acceleration effect was observed at a height of 1.5 m when the airflow interacted with the canopy. The ellipsoidal canopy produced the greatest increase, followed by the cylindrical and then the conical form. With an incoming wind speed of 1.9 m/s, the wind velocity rose to 2.43 m/s, 2.24 m/s, and 2.03 m/s, respectively, before gradually declining.

At 5 m, wind speed attenuation was more pronounced. Under an incoming wind speed of 2.5 m/s, the presence of tree canopies caused a sharp reduction, forming a distinct low-velocity wake zone. The minimum wind speeds were 0.27 m/s for the ellipsoidal canopy, 0.43 m/s for the cylindrical canopy, and 0.68 m/s for the conical canopy, highlighting the differing degrees of airflow obstruction imposed by each canopy morphology.

3.2.2. Single-Row Planting

As shown in

Figure 7 and 8, at a height of 1.5 m, the ellipsoidal canopy exerts the weakest attenuation effect on wind speed, followed by the cylindrical canopy, while the conical canopy produces the strongest reduction. In the downstream region at the same height, the wind speed ranks as follows: ellipsoidal highest, cylindrical intermediate, and conical lowest.

Figure 7.

Simulation results of the impact of single-row planting on wind speed.

Figure 7.

Simulation results of the impact of single-row planting on wind speed.

Figure 8.

Line chart of single-row planting and wind speed.Wind speed was obtained at 1.5 m (X=23, Y=–100-100, Z=1.5) and 5 m (X=23, Y=–100-100, Z=5).

Figure 8.

Line chart of single-row planting and wind speed.Wind speed was obtained at 1.5 m (X=23, Y=–100-100, Z=1.5) and 5 m (X=23, Y=–100-100, Z=5).

At 5 m height, all three canopy types induce pronounced wind speed attenuation, but with varying intensities: the ellipsoidal canopy exhibits the greatest reduction, the cylindrical canopy is intermediate, and the conical canopy the weakest. In the wake region, wind speed gradually recovers, with the recovery rate being slowest behind the ellipsoidal canopy, moderate behind the cylindrical canopy, and fastest behind the conical canopy.

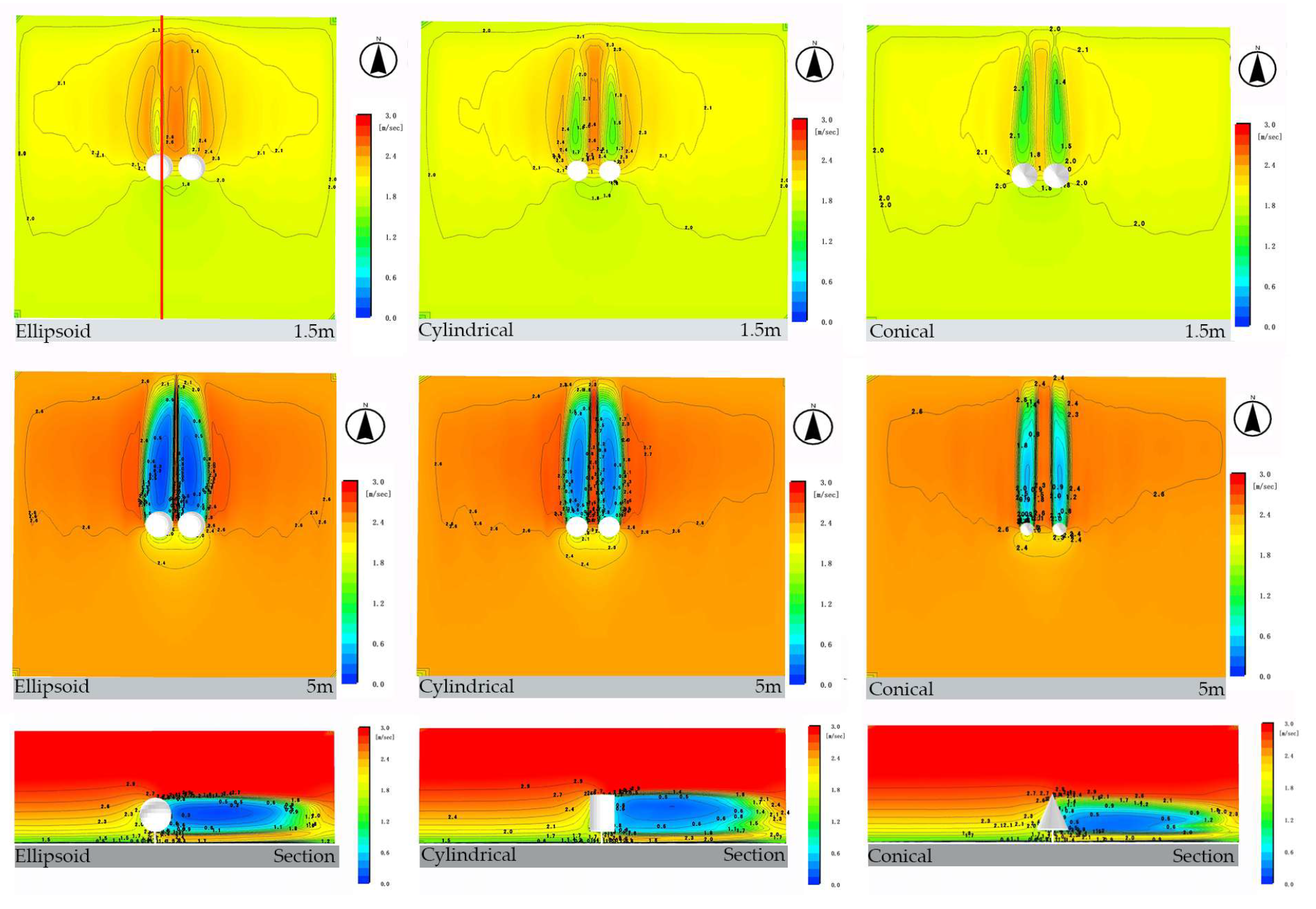

3.2.3. Opposite Tree Pair Planting

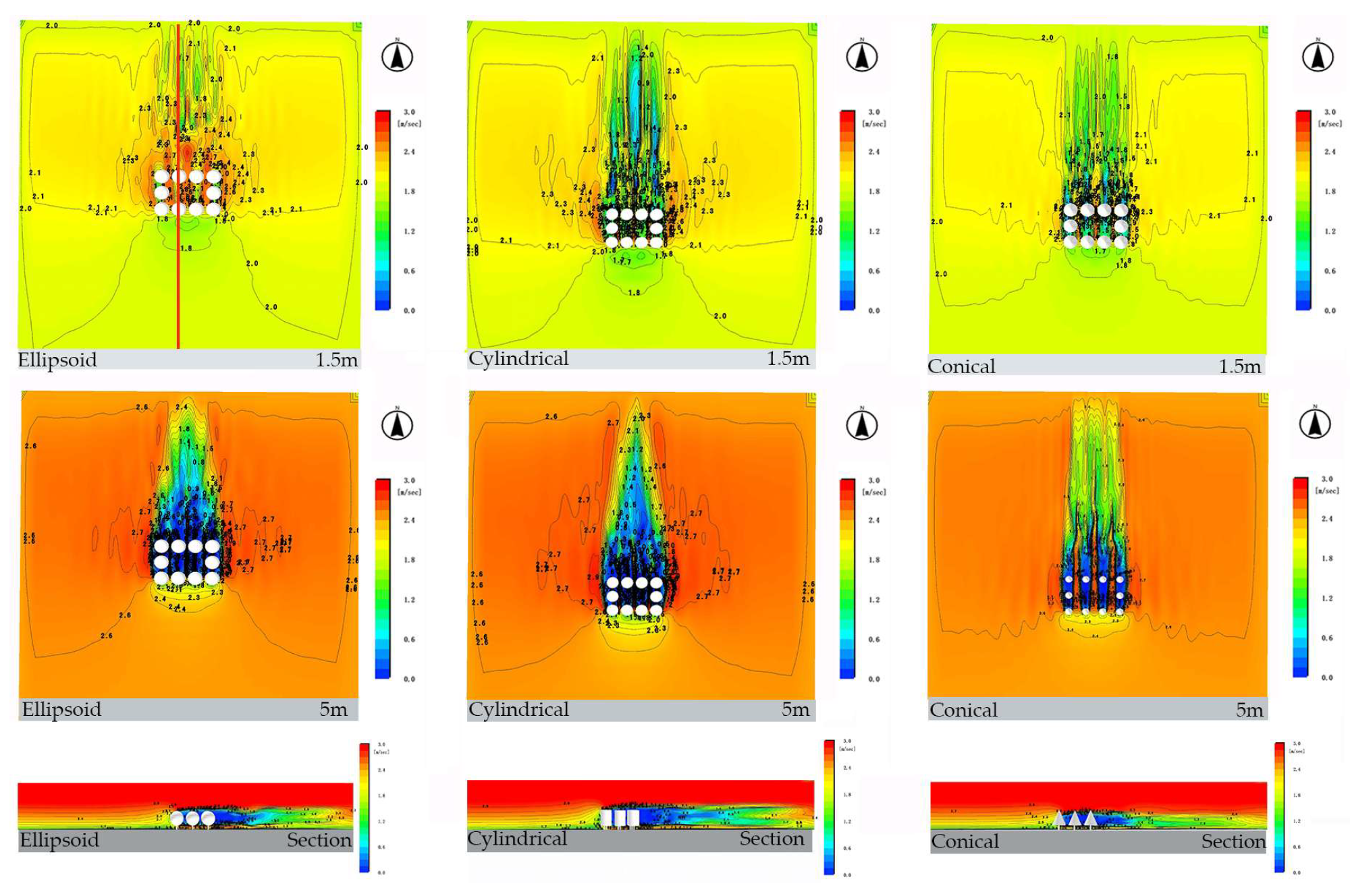

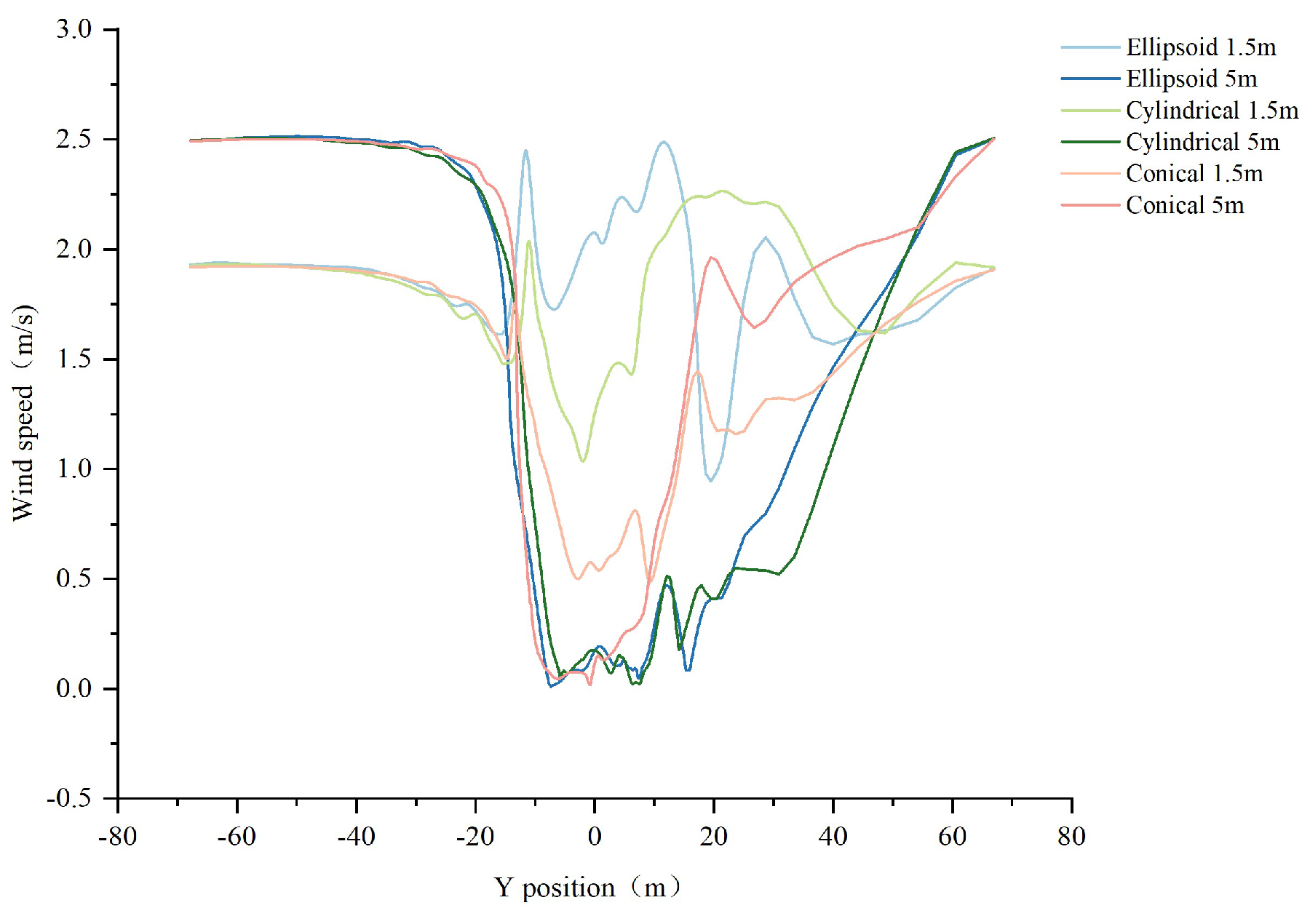

As shown in

Figure 9 and 10, under the two-row planting configuration, the wind speed responses at 1.5 m height exhibit pronounced differences among canopy morphologies. For the ellipsoidal canopy, the relatively weak attenuation of near-surface wind and the shorter reattachment distance result in a faster recovery of downstream wind speed. In contrast, the cylindrical canopy produces a relatively stable wake zone behind the trees, with a lower reattachment rate and thus weaker recovery capacity. The conical canopy, characterized by a larger windward cross-section at the lower part, imposes the strongest reduction on near-surface airflow.

Figure 9.

Simulation Results of Wind Speed under opposite tree pair planting.

Figure 9.

Simulation Results of Wind Speed under opposite tree pair planting.

Figure 10.

Line chart of opposite tree pair planting and wind speed.Wind speed was obtained at 1.5 m (X=12, Y=–80-80, Z=1.5) and 5 m (X=12, Y=–80-80, Z=5).

Figure 10.

Line chart of opposite tree pair planting and wind speed.Wind speed was obtained at 1.5 m (X=12, Y=–80-80, Z=1.5) and 5 m (X=12, Y=–80-80, Z=5).

At 5 m height under two-row planting, the effects of canopy morphology differ systematically from those at 1.5 m. The ellipsoidal canopy exerts stronger obstruction on the upper airflow, leading to greater attenuation and slower recovery. By comparison, the conical canopy, with substantially reduced radial dimensions at this height, imposes weaker direct blockage, thereby producing the smallest reduction and the fastest recovery. The cylindrical canopy exhibits intermediate behavior in both wind attenuation and recovery.

At both heights, wind speed recovers to the inflow levels (1.9 m/s at 1.5 m and 2.5 m/s at 5m) at approximately 75m downstream. Overall, the two-row planting configuration highlights differentiated patterns of attenuation intensity and recovery rate among the three canopy morphologies at different vertical layers.

3.2.4. Enclosure Planting

As shown in

Figure 11 and 12, at a height of 1.5 m, the overall wind speed attenuation effect is relatively weak for the ellipsoidal canopy, moderate for the cylindrical canopy, and strongest for the conical canopy. From a local perspective, when the airflow first encounters the canopy of the first tree, wind speed decreases, with the minimum dropping to 1.48 m/s. It then increases markedly, rising from the inflow velocity of 1.92 m/s to a peak of 2.45 m/s. Approaching the windward side of the second tree, the velocity declines again, reaching a minimum of 0.5 m/s, before gradually recovering to the inflow level.

Figure 11.

Simulation results of impact of enclosure planting on wind speed.

Figure 11.

Simulation results of impact of enclosure planting on wind speed.

Figure 12.

Line chart of enclosure planting and wind speed.Wind speed was obtained at 1.5 m (X=6, Y=–70-70, Z=1.5) and 5 m (X=6, Y=–70-70, Z=5).

Figure 12.

Line chart of enclosure planting and wind speed.Wind speed was obtained at 1.5 m (X=6, Y=–70-70, Z=1.5) and 5 m (X=6, Y=–70-70, Z=5).

At a height of 5 m, the airflow also exhibits a pronounced decrease immediately upon contacting the canopy. The ellipsoidal canopy exerts stronger obstruction on the upper flow, resulting in greater attenuation and slower recovery. The cylindrical canopy produces intermediate effects, whereas the conical canopy causes the weakest reduction in wind speed but facilitates the fastest recovery downstream. These results indicate that canopy morphology leads to significant differentiation in wind speed due to variations in canopy contact height and flow structure.

3.2.5. Curved Planting

As shown in

Figure 13 and 14, at a height of 1.5 m, the ellipsoidal canopy produces the weakest attenuation of wind speed, but also exhibits the slowest recovery. In contrast, both the cylindrical and conical canopies are more effective in responding to wind speed variations and demonstrate comparable recovery capacities.

Figure 13.

Simulation results of impact of curved planting on wind speed.

Figure 13.

Simulation results of impact of curved planting on wind speed.

Figure 14.

Line chart of curved planting and wind speed.Wind speed was obtained at 1.5 m (X=6, Y=–75-75, Z=1.5) and 5 m (X=6, Y=–75-75, Z=5).

Figure 14.

Line chart of curved planting and wind speed.Wind speed was obtained at 1.5 m (X=6, Y=–75-75, Z=1.5) and 5 m (X=6, Y=–75-75, Z=5).

At 5 m height, the differences among canopy morphologies become more pronounced. The simulation results indicate that the conical canopy generates a local minimum wind speed as low as 0.04 m/s, yet the downstream recovery rate is the fastest. By comparison, the cylindrical and ellipsoidal canopies maintain higher minimum wind speeds but display relatively slower recovery processes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Vertical Stratification of Tree Crown Morphology as a Regulatory Mechanism for Wind Environments

The simulation results demonstrate that tree crown morphology plays a critical role in shaping vertical wind speed profiles, with distinct crown forms producing variable attenuation effects at 1.5 m and 5 m heights.This is consistent with the findings of previous studies [

37,

38]. The simulation results highlight pronounced differences among the three tree crown morphologies in regulating wind environments at different vertical layers.

The ellipsoidal tree crown exhibited the weakest attenuation of wind speed at 1.5 m, thereby enhancing near-surface air circulation. By contrast, the conical tree crown produced the most substantial reduction of near-surface winds at 1.5 m. The cylindrical tree crown consistently demonstrated intermediate effects between the ellipsoidal and conical forms, both in terms of wind speed attenuation and recovery, reflecting a more balanced aerodynamic influence across vertical layers. This overall pattern is consistent with the conclusion that trees with conical canopies are subjected to less aerodynamic resistance than those with cylindrical canopies [

39].

This result is mainly due to the fact that airflow at 1.5m height is significantly affected by ground friction and obstacles, and the tree crown acts mainly as a porous obstacle at this height [

40]. Tree crown morphology regulates airflow by altering vertical porosity, which determines aerodynamic resistance [

41]. Ellipsoidal canopies, with open bases, create low-drag channels that weaken sheltering effects and minimize wind speed attenuation. Conical canopies, with wide and dense bases, disrupt vertical porosity, increase resistance, and force airflow upward or around the tree crown, producing the strongest attenuation. Cylindrical canopies maintain relatively uniform porosity, resulting in moderate resistance and intermediate effects between ellipsoidal and conical forms.

This study found that at a height of 5 m, the elliptical tree crown produced the strongest wind speed blockage and the slowest recovery, whereas the conical tree crown, with its spire-like structure, facilitated upward airflow and reduced resistance, thereby achieving the fastest recovery. The simulation results further suggest that the streamlined cusp of the conical tree crown minimized airflow disturbance by guiding smooth upward acceleration along its sloped surface and generating a Venturi effect [

42], which enhanced wind speed recovery in the wake region. The cylindrical tree crown exhibited intermediate effects, with both wind speed attenuation and recovery falling between those of the elliptical and conical forms.

However, the rounded apex of the ellipsoidal tree crown is susceptible to flow separation [

43] as airflow passes over its highest point, resulting in a low-pressure, turbulent wake region downstream [

44]. The abrupt termination of the vertical boundary at the top of cylindrical canopies also induces flow separation, though to a lesser extent than in rounded ellipsoids but more pronounced than in streamlined conical canopies. As a result, its impact on wind speeds lies between that of the conical and ellipsoidal forms.

4.2. Hydrodynamic Effects and Optimization Strategies of Plant Configuration Forms

This study revealed that the influence of tree crown shape on the wind environment varies substantially with the scale of planting configurations, shifting from single trees to larger groups. Different configurations generate complex hydrodynamic effects by reshaping the local flow field, producing outcomes that extend well beyond the simple superposition of individual trees. Different spatial arrangements of trees influence wind speed to varying degrees, a finding that is consistent with previous studies [

45]. An appropriate configuration not only enhances thermal and pedestrian comfort, but also guides urban wind corridors and improves neighborhood-scale ventilation efficiency, aligning closely with the positive environmental impacts reported by Hsieh et al. (2016) [

13].

The results of this study indicate that double planting initially produces mutual interference between adjacent tree canopies, leading to sharper fluctuations in the wind speed profile compared with the single-planting case. When the configuration is extended to single-row planting, trees begin to function as a continuous barrier, with flow characteristics largely governed by the horizontal continuity of tree crown structure. More complex flow dynamics emerge under double-row and enclosure planting configurations. As illustrated in

Figure 6, the double-row arrangement generates a characteristic “W”, shaped wind speed profile: airflow decelerates upon encountering the first row, accelerates within the confined channel between the two rows, and decelerates again upon impacting the second row. Within this system, the influence of tree crown morphology becomes multidimensional. Similar patterns of tree–tree aerodynamic interactions have also been reported in previous studies [

46].

This study systematically demonstrates the distinct behavioral patterns of different tree crown shapes during this transition, highlighting that the selection of an optimal tree form should be closely aligned with the scale of the intended planting configuration, rather than evaluated solely on the basis of its monoculture characteristics.

4.3. Practical Implications for Urban Planning and Wind Environment Optimization

The significance of this study lies not only in elucidating the underlying mechanisms, but also in demonstrating that wind environments at specific heights and zones can be effectively managed through the targeted selection of tree crown shapes and planting configurations.

In pedestrian-intensive areas such as streets, squares, and park rest zones, maintaining ventilation comfort at 1.5 m is essential to prevent heat buildup and pollutant stagnation. This study shows that ellipsoidal canopies, under both double and single-row planting, provide the least wind attenuation at this height and may even create localized acceleration, making them particularly suitable for such contexts. At 5 m, their strong blocking effect further helps to reduce wind impacts near the corners of low-rise buildings. In areas that demand protection from strong winds, reducing wind speeds at pedestrian height is essential. The broad base of conical crowns substantially weakens winds at 1.5 m, offering effective ground shelter. Thus, conical-crowned trees are well suited for fencing or strip planting in open spaces to establish efficient windbreak systems. Cylindrical canopy trees are recommended for transitional zones requiring both ventilation and protection, such as inter-building corridors and low-density residential areas. Their moderate effects help avoid poor near-ground ventilation, limit high-altitude wind-shadow zones, and promote a smoother transition in the wind environment.

Planting configuration patterns should be designed in coordination with tree crown morphology. When the design objective is to enhance ventilation, single- or double-row plantings of ellipsoidal crowns are recommended. As demonstrated in this study, such arrangements can utilize canopy gaps to form effective ventilation corridors. In particular, double-row planting generates significant wind acceleration between rows, making it suitable for channeling prevailing summer winds. Conversely, when wind protection is the primary goal, multi-row or fence-like configurations of conical crowns are preferable. Their broad bases create a continuous windbreak, while their streamlined tops reduce undesirable turbulence and allow the wind field to recover smoothly in the leeward zone. Perimeter planting is especially effective for establishing sheltered microclimates, such as in parks or children’s playgrounds, where the enclosed wind field becomes more complex and overall wind speeds are significantly reduced. Within such enclosures, ellipsoidal crowns are most suitable when internal ventilation is prioritized, whereas conical or cylindrical crowns are more appropriate when the goal is to block strong external winds.

This study highlights the importance of precision design based on wind environment considerations. Recognizing canopy aerodynamics as equally important as aesthetic and ecological values enables urban green spaces to function not only as visual amenities but also as infrastructures for active microclimate regulation.

4.4. Limitations of the Study and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, an idealized canopy model with a fixed geometric form and uniform surface was adopted, whereas real trees are dynamic, heterogeneous, and structurally complex. Future research should incorporate key parameters such as the vertical distribution of Leaf Area Density (LAD), spatial and temporal variations in porosity (e.g., deciduous vs. evergreen), and branch flexibility, as well as extend the analysis to additional canopy geometries (e.g., hemispherical, umbrella-like) and morphometric traits (e.g., aspect ratio, volume, projected area) to establish more generalized predictive models. Second, the simulations assumed a steady, unidirectional inflow, while the actual urban wind environment is highly variable; therefore, the performance of different planting configurations under fluctuating wind speeds and directions warrants further investigation. Finally, this study focused solely on aerodynamic effects and did not account for thermal influences. In real environments, temperature gradients substantially affect atmospheric stability and airflow patterns. Future work should combine CFD with urban canopy models to assess the thermal comfort contributions of evapotranspiration and heat exchange in various tree species.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the regulatory effects of tree crown morphology and planting layout on the urban wind environment at pedestrian height (1.5 m) and low-canopy height (5 m) in a high-density hot–humid city. The results demonstrate that vertical stratification of wind speed is primarily governed by crown morphology: under single-tree conditions, ellipsoidal crowns enhance near-surface ventilation but create strong obstruction aloft; conical crowns provide effective shelter at the ground level yet facilitate rapid downstream recovery; cylindrical crowns consistently exhibit intermediate effects between the two. Planting layouts further amplify or moderate these differences: single-row ellipsoidal crowns balance pedestrian-level ventilation with upper-layer blockage; double-row planting generates a pronounced channel effect at pedestrian height, intensifying inter-row acceleration; enclosure layouts magnify intra-area wind speed differences; while curved layouts highlight morphology-dependent recovery patterns, with ellipsoidal crowns recovering the slowest and cylindrical and conical crowns recovering faster. Accordingly, different site conditions should be matched with appropriate crown forms and planting configurations to optimize pedestrian thermal comfort and improve low-altitude ventilation corridors.

Overall, this study emphasizes the importance of incorporating crown morphology and spatial configuration into refined urban greening design. By doing so, urban green spaces can serve not only ecological and aesthetic functions but also act as infrastructures for active microclimate regulation, thereby providing scientific support for enhancing climate resilience in high-density hot–humid cities.

6. Patents

Heyang Qin was responsible for study design, data processing, manuscript writing, and result interpretation. Chun-Ming Hsieh provided overall guidance throughout the study and conducted substantial revisions. Liyu Pan drafted the Introduction and Methodology sections, and also contributed to proofreading and revising the manuscript. Xueying Wu participated in writing the discussion and revising the manuscript. Shuyi Guo was responsible for study design.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Development Fund (0057/2022/A and 0003/2025/RIA) of Macau.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the data support provided by the Macao Special Administrative Region Government, Macao Meteorological and Geophysical Bureau (SMG), and the field support offered by the Municipal Affairs Bureau of Macao (IAM).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hua, J.; Zhang, X.; Ren, C.; Shi, Y.; Lee, T.-C. Spatiotemporal Assessment of Extreme Heat Risk for High-Density Cities: A Case Study of Hong Kong from 2006 to 2016. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 64, 102507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.; Li, C.; Zhou, L.; Yang, H.; Burghardt, R. Built Environment Influences on Urban Climate Resilience: Evidence from Extreme Heat Events in Macau. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Pan, L.; Hsieh, C.-M. Multi-Scale Analysis of the Mitigation Effect of Green Space Morphology on Urban Heat Islands. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wu, S.; Liang, Z.; Li, S. The Impacts of Urbanization and Climate Change on Urban Vegetation Dynamics in China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 54, 126764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Ghalambaz, S.; Sheremet, M.; Baro, M.; Ghalambaz, M. Deciphering Urban Heat Island Mitigation: A Comprehensive Analysis of Application Categories and Research Trends. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, P.; Hu, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Zhu, L.; Ni, G. Canopy Transpiration and Its Cooling Effect of Three Urban Tree Species in a Subtropical City- Guangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 43, 126368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Juan, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.-T.; Wen, C.-Y.; Yang, A.-S. Effects of Urban Tree Planting on Thermal Comfort and Air Quality in the Street Canyon in a Subtropical Climate. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 91, 104334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.-Y.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Lin, T.-P. The Influence of Trees Shade Level on Human Thermal Comfort and the Development of Applied Assessment Tools. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 263, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How Can Trees Protect Us from Air Pollution and Urban Heat? Associations and Pathways at the Neighborhood Scale. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 236, 104779. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, P.; Lim, K.C.; Jamei, E. Urban Heat Island and Wind Flow Characteristics of a Tropical City. Sol. Energy 2014, 107, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, D.; Bauhus, J.; Mayer, H. Wind Effects on Trees. Eur. J. For. Res. 2012, 131, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhao, M.; Huo, J.; Sha, Y.; Zhou, Y. The Impact of Vegetation Layouts on Thermal Comfort in Urban Main Streets: A Case Study of Youth Street in Shenyang. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-M.; Jan, F.-C.; Zhang, L. A Simplified Assessment of How Tree Allocation, Wind Environment, and Shading Affect Human Comfort. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 18, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-M.; Huang, H.-C. Mitigating Urban Heat Islands: A Method to Identify Potential Wind Corridor for Cooling and Ventilation. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2016, 57, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setaih, K. The Effect of Asymmetrical Street Aspect Ratios on Urban Wind Flow and Pedestrian Thermal Comfort Conditions.; 2016.

- Ricci, A.; Burlando, M.; Repetto, M.P.; Blocken, B. Static Downscaling of Mesoscale Wind Conditions into an Urban Canopy Layer by a CFD Microscale Model. Build. Environ. 2022, 225, 109626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.H.; He, Y.; Nguyen, N.S.; Raghavan, S.V.; Martin, M.; Hii, D.J.C.; Yu, Z.; Deng, J. An Integrated Multiscale Urban Microclimate Model for the Urban Thermal Environment. Urban Clim. 2021, 35, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, A.; Hong, S.-H.; Park, K.; Baik, J.-J. Simulating Urban Heat Islands and Local Winds in the Dhaka Metropolitan Area, Bangladesh. Urban Clim. 2025, 59, 102284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.; Yuan, C.; Chen, L.; Ren, C.; Fung, J.C.H. Improving the Wind Environment in High-Density Cities by Understanding Urban Morphology and Surface Roughness: A Study in Hong Kong. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 101, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, B.; Ouyang, X.; Chen, X.; Bedra, K.B. Does Shrub Benefit the Thermal Comfort at Pedestrian Height in Singapore? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.; Lin, B. Numerical Studies of the Outdoor Wind Environment and Thermal Comfort at Pedestrian Level in Housing Blocks with Different Building Layout Patterns and Trees Arrangement. Renew. Energy 2015, 73, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Niu, J.; Xia, Q. Combining Measured Thermal Parameters and Simulated Wind Velocity to Predict Outdoor Thermal Comfort. Build. Environ. 2016, 105, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Norford, L.; Ng, E. A Semi-Empirical Model for the Effect of Trees on the Urban Wind Environment. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 168, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, L. (Leon); Stathopoulos, T.; Marey, A.M. Urban Microclimate and Its Impact on Built Environment – A Review. Build. Environ. 2023, 238, 110334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefny Salim, M.; Heinke Schlünzen, K.; Grawe, D. Including Trees in the Numerical Simulations of the Wind Flow in Urban Areas: Should We Care? J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2015, 144, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.; Kim, M. Research on Plant Landscape Design of Urban Industrial Site Green Space Based on Green Infrastructure Concept. Plants 2025, 14, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Luo, X.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, C.; Chen, Z. Study on the Impact of Tree Species on the Wind Environment in Tree Arrays Based on Fluid–Structure Interaction: A Case Study of Hangzhou Urban Area. Buildings 2024, 14, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani-Beni, M.; Tabatabaei Malazi, M.; Dehghanian, K.; Dehghanifarsani, L. Investigating the Effects of Wind Loading on Three Dimensional Tree Models Using Numerical Simulation with Implications for Urban Design. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccolieri, R.; Santiago, J.-L.; Rivas, E.; Sanchez, B. Review on Urban Tree Modelling in CFD Simulations: Aerodynamic, Deposition and Thermal Effects. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Xu, Z. Analysis of Urban Public Spaces’ Wind Environment by Applying the CFD Simulation Method: A Case Study in Nanjing. Geogr. Pannonica 2019, 23, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husna Aini Swarno; Nurul Huda Ahmad; Ahmad Faiz Mohammad; Nurnida Elmira Othman Numerical Simulation of the Tree Effects on Wind Comfort and Wind Safety Around Coastline Building Resort. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2024, 117, 1–42. [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Yu, C.-Y.; Xian, T.; Wu, X. Do Parks Act as Cool Islands? A Cross-Scale Evaluation of Their Daytime Cooling Dynamics through Land Surface Temperature and Thermal Comfort in Macau. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 130, 106617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Pan, L.; Hsieh, C.-M. Multi-Scale Analysis of the Mitigation Effect of Green Space Morphology on Urban Heat Islands. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Shen, S.; I, L.W.; Kan, L.W.; Chan, I.T.; He, C.B.; He, J.Q.; Wong, U.H.; Lao, E.P.L.; Smith, R.D. Associations of Ambient Temperature and Relative Humidity with Hospital Admissions in Macau, China Using Time Series Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.-M.; Aramaki, T.; Hanaki, K. The Feedback of Heat Rejection to Air Conditioning Load during the Nighttime in Subtropical Climate. Energy Build. 2007, 39, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-M.; Aramaki, T.; Hanaki, K. Managing Heat Rejected from Air Conditioning Systems to Save Energy and Improve the Microclimates of Residential Buildings. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2011, 35, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayaud, J.R.; Wiggs, G.F.S.; Bailey, R.M. Characterizing Turbulent Wind Flow around Dryland Vegetation. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2016, 41, 1421–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodayari, N.; Hami, A.; Farrokhi, N. The Effect of Trees with Irregular Canopy on Windbreak Function in Urban Areas. Int. J. Archit. Eng. Urban Plan. 2021, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Loehle, C. Biomechanical Constraints on Tree Architecture. Trees 2016, 30, 2061–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.; Kim, J.-J.; Choi, W. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation of Tree Effects on Pedestrian Wind Comfort in an Urban Area. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 56, 102086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, F.; Bell, S. Simulating the Sheltering Effects of Windbreaks in Urban Outdoor Open Space. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2007, 95, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocken, B.; van Hooff, T.; Aanen, L.; Bronsema, B. Computational Analysis of the Performance of a Venturi-Shaped Roof for Natural Ventilation: Venturi-Effect versus Wind-Blocking Effect. Comput. Fluids 2011, 48, 202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, J. The Influence of Wind-Induced Response in Urban Trees on the Surrounding Flow Field. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.K.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Hussain, M.; Lee, S.; Chung, H.; Chung, S. A Wind Tunnel Test for the Effect of Seed Tree Arrangement on Wake Wind Speed. Forests 2024, 15, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhan, Q.; Lan, Y. Effects of the Tree Distribution and Species on Outdoor Environment Conditions in a Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone: A Case Study in Wuhan Residential Quarters. Build. Environ. 2018, 130, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.J.; Cannon, J.B. Modelling Wind Damage to Southeastern Us Trees: Effects of Wind Profile, Gaps, Neighborhood Interactions, and Wind Direction. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4, 719813. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).