Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Rationale

Methods

Study Design and Setting

Data Collection

Analytical Framework

Data Analysis

Ethics

Results

Biological Domain: Symptom Profiles, Physiology, Comorbidity

Socio-Cultural Domain: Norms, Roles, Stigma, Socioeconomic Position

Cultural Explanations and Stigma

Health System: Organisation, Quality, and Access

Anticipatory information Gaps

Primary Care and Pathways

Resourcing and Affordability

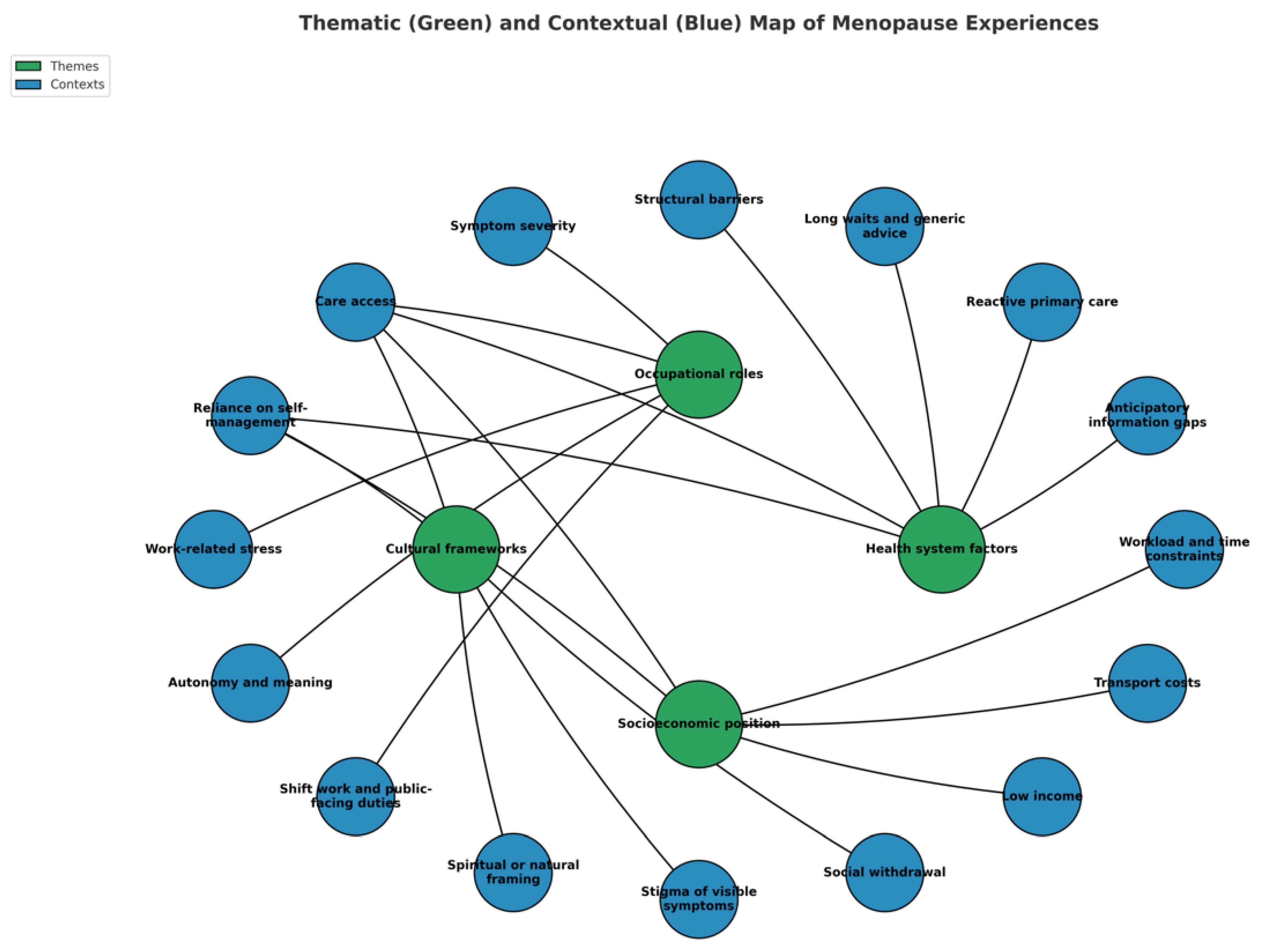

Cross-Correlation Context

Discussion

Interpretation

Clinical Impact

Policy Impact

Population Context

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Code Availability

Ethics Approval

Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Material

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations sexual and reproductive health agency. Nigeria Population 2025 - United Nations Population Fund, (. https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population/NG.

- World Bank Group. Population, female - Nigeria, (2024). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL.FE.IN?locations=NG.

- StatisticsTimes.com. Demographics of Nigeria, (2024). https://m.statisticstimes.com/demographics/country/nigeria-demographics.php?

- Jaff, N. G. & Crowther, N. J. The association of reproductive aging with cognitive function in Sub-Saharan African women. Physical Exercise and Natural and Synthetic Products in Health and Disease, 71-91 (2021).

- Chikwati, R. P. et al. The association of menopause with cardiometabolic disease risk factors in women living with and without HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: Results from the AWI-Gen 1 study. Maturitas 187, 108069 (2024).

- Ameh, N., Madugu, N., Onwusulu, D., Eleje, G. & Oyefabi, A. Prevalence and predictors of menopausal symptoms among postmenopausal Ibo and Hausa women in Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 33, 263 (2016).

- Okolo, A. & Aniuga, C. Awareness And Responsiveness to Health Challenges Peculiar to Women: A Global Perceptive. Managamanet, 2015; 244. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeanyi, E. M. & Ikobho, E. H. Age at menopause and the correlates of natural menopause among urban and rural women in the Southern Nigeria. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol, 2021; 10, 1266. [Google Scholar]

- Delanerolle, G.; et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health, 2025; 13, e196–e198. [Google Scholar]

- OYIBOCHA, E. O. Experiences of Midlife Women and Related Co-Morbidity Issues During Menopausal Transition in Delta State, Nigeria. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, U. C. & Ene, O. C. Association between osteoporosis and severe depressive symptoms among postmenopausal women attending tertiary outpatient clinics in Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health, 2025; 25, 400. [Google Scholar]

- Imaralu, J. A Five-Year Review of Laparoscopic Gynaecological Surgeries in a Private-Owned Teaching Hospital, in Nigeria: West Afr J Med. 2022 Feb 28; 39 (2): 111-118. West Africa Journal of Medicine, 2022; 39, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ukah, C. , Okhionkpamwonyi, O., Okoacha, I. & Okonta, P. A 5-year review of hysterectomy at the Delta State University Teaching Hospital, Oghara, southsouth Nigeria. Ibom Medical Journal, 2023; 16, 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Thisday Newspapers LTD. 2019.

- Angaye, U. S. & Sibiri, E. A. Between stigma and support: how socio-cultural norms shape health decisions among perimenopausal women in bayelsa central, Nigeria. African journal for the psychological studies of social issues, 2025; 28. [Google Scholar]

- Omidoyin, F. Factors Affecting Level of Preparedness For Menopause Among Pre-Menopausal Women in Leo Community, Ido Local Government Area, Oyo State, Nigeria, (2014).

- Ibeachu, C. P. & Uahomo, P. O. Quality of Life in Menopausal Women: Effects of Sociodemographic Factors and Symptoms. South Asian Res J Med Sci, 2024; 6, 178–188. [Google Scholar]

- Balogun, J. A. in The Nigerian healthcare system: pathway to universal and high-quality health care 117-152 (Springer, 2022).

- Islam, R. M.; et al. Menopause in low and middle-income countries: a scoping review of knowledge, symptoms and management. Climacteric, 2025; 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Abah, V. O. in Healthcare Access-New Threats, New Approaches (IntechOpen, 2022).

- Uno, O. E.-O. , Biya, C., Okoye, N. J.-F., Okoye, C. P. & Ozigbo, A. A. A Review on Sociocultural Barriers Affecting Healthcare Access Among Older Adults in Nigeria. Journal of Pharma Insights and Research, 2025; 3, 032–039. [Google Scholar]

- ESCAP, U. & World Health Organization. SDG 3: Good health and well-being. (2021).

| Stage | Description | Application in MARIE WP2a (Nigeria) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Contextual familiarisation | Immersion in transcripts to understand cultural, social, and structural contexts influencing participant narratives. | Researchers reviewed each transcript multiple times, alongside field notes, to identify Nigeria-specific contextual factors such as gender role expectations, cultural beliefs about menopause, and urban–rural healthcare disparities. |

| 2. Equity-oriented coding | Generating initial codes that capture both descriptive phenomena and equity-linked determinants (e.g., gender norms, healthcare access, socioeconomic position). | Codes were developed to reflect participants’ accounts of barriers to care, affordability of treatment, social stigma, workplace exclusion, and intersectional disadvantages linked to age, marital status, and economic position. |

| 3. Framework mapping | Organising codes into domains reflecting individual, community, health system, and policy levels, while retaining cross-cutting themes such as stigma, intersectionality, and structural inequality. | Coded data were categorised into four framework domains (individual, community, health system, policy) with cross-cutting Nigerian-specific themes, including religious influences on treatment choice, reliance on informal care networks, and systemic underfunding of women’s health. |

| 4. Integrative interpretation | Synthesising findings to highlight the interplay between lived experiences and systemic factors, situating these within national sociocultural and healthcare contexts. | Themes were integrated to explain how menopause experiences in Nigeria are shaped by sociocultural beliefs, structural health inequities, and policy gaps, highlighting implications for equitable service delivery. |

| Code | Sub-code | Operational definition | Example indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vasomotor symptoms | Visible hot flushes at work | Socially noticeable sweating/heat episodes affecting work or interactions. | Facial sweating causing embarrassment at work |

| Mild internal heat, self-managed | Hot flushes/internal heat present but manageable without treatment. | Internal heat managed independently; no escalation | |

| Heat-triggered sleep fragmentation | Sleep disrupted by heat/humidity; improved by environmental cooling. | Night waking in hot weather; uses rechargeable fan | |

| Musculoskeletal pain | Continuous/limiting low-back pain | Ongoing/recurrent LBP restricting activities; medication use reported. | Continuous, activity-limiting LBP; analgesics required |

| Activity-linked low-back pain (LBP) | Intermittent LBP after prolonged shifts/manual tasks; settles with rest. | LBP after long nursing shifts | |

| Pelvic pain (intermittent) | Pelvic/waist pain that comes and goes; often untreated. | Episodic pelvic pain without therapy | |

| Functional selection due to pain | Task modification/avoidance at work because of pain. | Selects lighter duties during flares | |

| Urogenital symptoms | Stress/urgency incontinence | Leakage if toilet access delayed or with urgency; sometimes medicated. | Needs rapid toilet access; prior continence medication |

| No GU symptoms | Explicit denial of urinary incontinence/pelvic pain. | No GU complaints recorded | |

| Sleep | Stable, protective routine | Consistent sleep/wake pattern; refreshing sleep without aids. | Early regular bedtimes; restorative sleep |

| Insomnia with functional impact | Poor sleep (initiation/maintenance/early waking) reducing daytime performance. | Low sleep rating; daytime fatigue/productivity loss | |

| Ad-hoc hypnotic use / no routine | Intermittent sedative use and/or lack of structured sleep routine. | Occasional sleep tablets; no set routine | |

| Psychological symptoms | Mood lability/irritability | Fluctuating mood, irritability or aggression linked to menopause. | Irritability affecting work interactions |

| Low mood/anxiety | Persistent sadness, worry or anxiety during menopause. | Anxiety/mood swings during flares | |

| Cognitive difficulty | Concentration/forgetfulness impairing task performance. | Uses notes/reminders to compensate | |

| Preference for solitude | Desire to withdraw/isolate as coping. | Seeks quiet space; works alone when overwhelmed | |

| Suicidality risk | Hopelessness | Expressed hopelessness related to menopausal burden. | Affirmed hopelessness on direct probe |

| Thoughts life not worth living | Acknowledged thoughts that life is not worth living. | Affirmed SI probe during interview | |

| Work impact & adaptation | Work stress ↑ from baseline | Self-rated stress higher post-menopause vs pre-. | Stress 8–9/10 vs 4–6/10 pre- |

| Shift/night-duty intolerance | Night shifts/long hours newly difficult due to symptoms. | Reduced tolerance for nights/physically heavy tasks | |

| Pacing/micro-breaks/quiet space | Uses breaks, steady pacing, or quiet areas to cope. | Short breaks and quiet room improve functioning | |

| Role redesign/supervisory buffer | Shift to supervisory/mentoring duties reduces strain. | Supervisory role with low physical load; volunteer role buffering stress | |

| Workplace supports | Supportive managers, no policy | Informal accommodation without formal menopause policy. | Supervisor understanding but no written policy |

| Desired adjustments | Concrete requests for cooling, toilet access, flexible breaks. | Fans/cool spaces; ready toilet access; flexible rest periods | |

| Care-seeking & literacy | Anticipatory education absent | Reports no prior menopause education from health services. | No clinician-led information before onset |

| Informal knowledge sources | Learnt via family, friends, colleagues or books. | Maternal advice | |

| Reactive care / screening-only | Care sought at symptom peak; screening done without management plan. | Pap smear offered; no menopause plan | |

| Treatment stance & preferences | HRT hesitancy/avoidance | Avoids HRT due to risk beliefs or preference for “natural” care. | Fear of oestrogen risks; spiritual/natural framing |

| HRT used → benefit | Reports HRT with perceived symptom improvement. | On HRT with improvement noted | |

| Supplement reliance | Use of oils/minerals (eg, evening primrose, starflower, calcium). | Evening primrose perceived helpful | |

| Non-pharmacological pacing/rest | Symptom management through rest, pacing, trigger reduction. | Rest periods resolve flares; ceased early morning commitments | |

| Structural & economic barriers | Doctor shortages/quality concerns | Perceived lack of clinicians or poor-quality/generic advice. | Reports of “no doctors” or poor quality care |

| High costs/transport burden | Financial barriers and transport costs limiting access. | Transport costs and hospital bills cited as barriers | |

| Long waits/limited PC support | Long waits; primary care supportive but not menopause-literate. | Limited HRT discussion; generic support only | |

| Social support | Peer confiding | Reliance on friends/peers for emotional support. | Confides in close friend to cope |

| Family labelling symptoms | Family members help name/normalise menopausal symptoms. | Mother identified hot flushes for participant | |

| Comorbidities & parity | Hypertension/diabetes context | NCDs co-exist and influence options/risks. | Comorbidities |

| High parity | ≥3 vaginal births with midlife pelvic-floor implications. | Births | |

| Caesarean for multiples | C/S after multiple gestation. | Triplet pregnancy leading to caesarean | |

| Protective wellbeing | Positive affect/resilience | Stable positive mood and high wellbeing despite menopause. | Consistently happy/energised; no symptoms |

| Meaningful roles & autonomy | Purposeful activity and autonomy buffer distress. | Volunteering; independent driving; supervisory work |

| Participant ID | REGION | AGE (Years) | Menopause stage | Socioeconomic status | Educational Level | Ethnicity | Comorbidies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Awka | 66 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q3 | Primary | Igbo | No |

| 2 | Nnewi | 61 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q3 | Secondary | Igbo | No |

| 3 | Enugu | 57 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q2 | secondary | Igbo | GERD |

| 4 | Lagos | 57 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q1 | Tertiary | Yoruba | No |

| 5 | Ozubulu | 55 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q2 | Secondary | Igbo | No |

| 6 | Nnewi | 61 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q3 | Primary | Igbo | No |

| 7 | Enugu | 59 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q2 | Secondary | igbo | No |

| 8 | Kano | 58 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q2 | Secondary | Hausa | Hypertension |

| 9 | Kano | 55 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q3 | Tertiary | Hausa | No |

| 10 | Oraifite | 65 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q1 | Tertiary | Igbo | No |

| 11 | Ihiala | 60 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q1 | Tertiary | Igbo | Hypertension & Diabetes Mellitus |

| 12 | Nnobi | 59 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q3 | Secondary | Igbo | No |

| 13 | Nnewi | 62 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q1 | Tertiary | Igbo | No |

| 14 | Nsukka | 58 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q2 | Secondary | Igbo | No |

| 15 | Ibadan | 64 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q2 | Tertiary | Yoruba | No |

| 16 | Jalingo | 63 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q2 | Secondary | Hausa | No |

| 17 | Akure | 61 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q3 | Secondary | Yoruba | Hypertension and Diabetes mellitus |

| 18 | Lagos | 57 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q3 | Secondary | Yoruba | No |

| 19 | Lagos | 58 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q2 | Secondary | Yoruba | No |

| 20 | Lagos | 66 | Post-menopause (Surgical) | Q1 | Tertiary | Yoruba | No |

| 21 | Ojiriver | 65 | Post-menopause (Natural) | Q2 | Secondary | Igbo | No |

| Recommendation | Rationale | Priority Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Integrate menopause care into primary healthcare services | Reduces diagnostic delays, ensures continuity of care | Include menopause screening in routine check-ups; train PHC workers |

| Develop Nigerian-specific clinical guidelines for menopause | Provides standardised care pathways | Collaborate with NMA, FMOH, and women’s health experts |

| Expand access to affordable HRT | Addresses cost and availability barriers | Add HRT to National Essential Medicines List; explore subsidy schemes |

| Implement national menopause awareness campaigns | Reduces stigma, increases health-seeking | Use radio, TV, social media, and community outreach |

| Incorporate menopause education into health professional curricula | Improves provider competence | Revise medical, nursing, and pharmacy curricula |

| Foster community-based support programmes | Builds peer networks and trust | Leverage women’s groups, NGOs, and faith-based organisations |

| Establish menopause research funding streams | Fills data gaps, guides policy | Advocate to national and international funders; link to SDGs |

| Increase African-led menopause research collaborations | Strengthens contextual evidence | Create regional research consortia and mentorship networks |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).