Submitted:

06 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

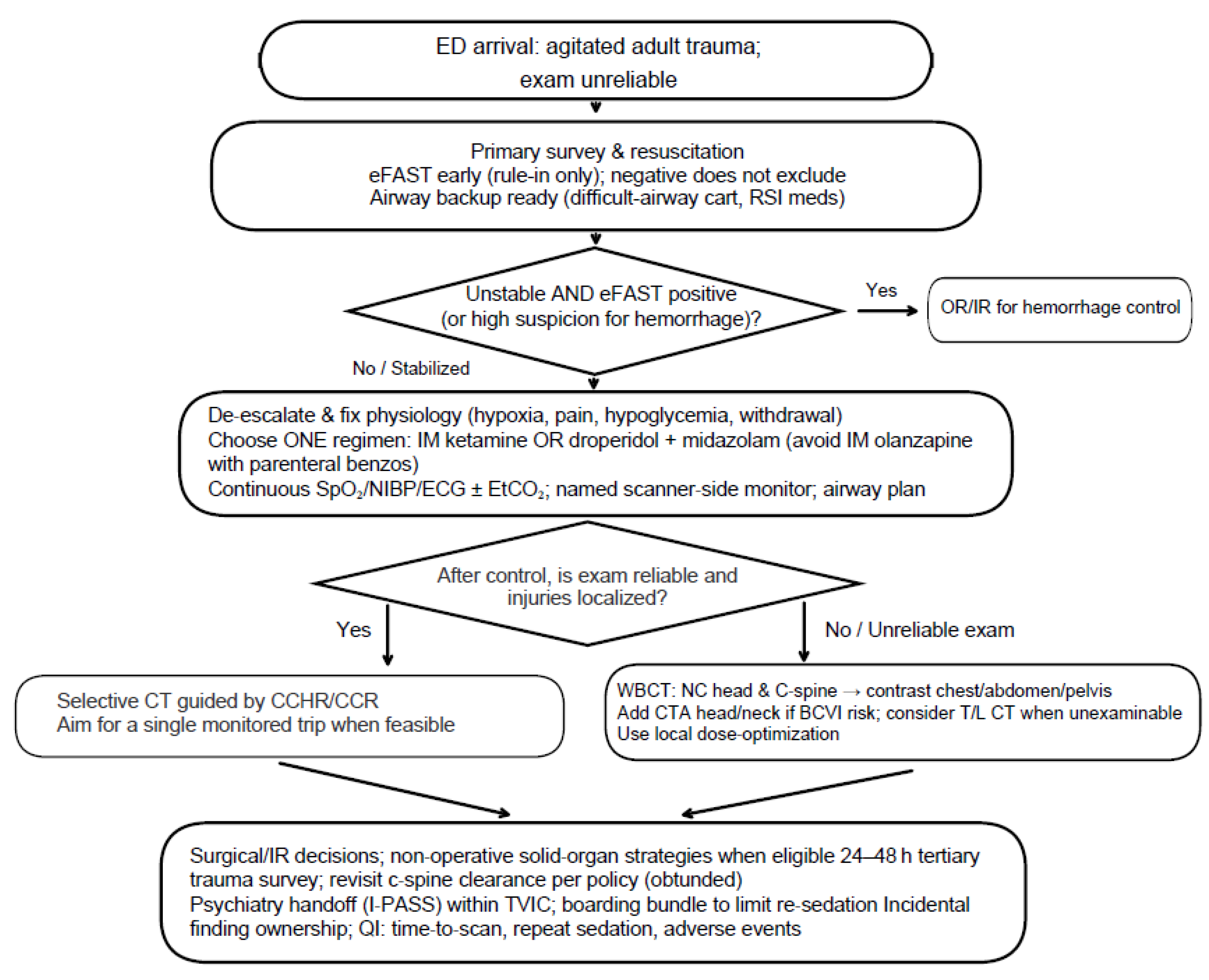

Triage & eFAST-First in the Unreliable Exam

- Unstable patients with positive eFAST or high suspicion of injury: Hemorrhage control is typically prioritized (e.g., straight to OR) over CT. In this context, eFAST has largely supplanted diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) for rapid intra-abdominal bleeding assessment (American College of Surgeons, 2021).

- Stable or stabilized patients but eFAST exam unreliable: the ACR Appropriateness Criteria for Major Blunt Trauma endorses early CT in polytrauma or when clinical assessment is limited. (American College of Radiology, 2025)

Agitation Control to Enable Imaging

- A.

- Rapid single-agent dissociation with ketamine. Evidence from a Canadian RCT supports faster onset versus haloperidol-midazolam in severe agitation (Barbic & Andolfatto, 2021).

- B.

- Antipsychotic + benzodiazepine combination (e.g., droperidol + midazolam) as a guideline supported option when dissociation is not chosen or is contraindicated (American College of Emergency Physicians, 2024).

- C.

- Alternatives include haloperidol ± lorazepam, or IM olanzapine. Avoid co-administration with parenteral benzodiazepines per the product monograph (Eli Lilly Canada, 2020). Agent selection should align with local formulary and policy.

Imaging Decision Node: Selective CT vs Whole-Body CT (WBCT)

Scenarios where WBCT is considered:

- Persistently unreliable or unobtainable eFAST exam despite initial sedation.

- High-energy injury mechanism or suspicion for multi-region injury (e.g., head/neck + chest/abdomen/pelvis).

- Positive eFAST with uncertainty about other compartments.

- After agitation control, the patient regains cooperation and injuries localize clinically.

- Decision rules can be applied (e.g., CCHR, CCR) to focus imaging.

Downstream Surgical Implications

Psychiatric Handoff & Disposition

Discussion

Worked Case: Applying the Conceptual Evidence Map

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2017). Tool: I-pass | agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps-program/curriculum/communication/tools/ipass.html.

- Alrajab, S., Youssef, A. M., Akkus, N. I., & Caldito, G. (2013). Pleural ultrasonography versus chest radiography for the diagnosis of pneumothorax: Review of the literature and meta-analysis. Critical Care, 17(5). [CrossRef]

- American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Severe Agitation. (2024). Clinical policy: Critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult out-of-hospital or emergency department patients presenting with severe agitation. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 83(1), e1–e30. [CrossRef]

- American College of Radiology, Society of Interventional Radiology, & Society for Pediatric Radiology. (2025). Practice parameter for minimal and/or moderate sedation/analgesia in radiology. https://gravitas.acr.org/PPTS/DownloadPreviewDocument?DocId=95.

- American College of Surgeons. (2021). Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) best practices in imaging for trauma patients. https://www.facs.org/media/oxdjw5zj/imaging_guidelines.pdf.

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Moderate Procedural Sedation and Analgesia; American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons; American College of Radiology; American Dental Association; American Society of Dentist Anesthesiologists; & Society of Interventional Radiology. (2018). Practice guidelines for moderate procedural sedation and analgesia 2018. Anesthesiology, 128(3), 437–479. [CrossRef]

- Arruzza, E., Chau, M., & Dizon, J. (2020). Systematic Review and meta-analysis of whole-body computed tomography compared to conventional radiological procedures of trauma patients. European Journal of Radiology, 129, 109099. [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C., Goldbeck-Wood, S., & Mertens, S. (2019). Sanra—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Barbic, D., Andolfatto, G., Grunau, B., Scheuermeyer, F. X., Macewan, B., Qian, H., Wong, H., Barbic, S. P., & Honer, W. G. (2021). Rapid agitation control with ketamine in the emergency department: A blinded, randomized controlled trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 78(6), 788–795. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, N. L., Kim, M. J., & Menon, M. R. (2021). Binder use and early pelvic radiographs in the management of unstable patients with blunt trauma. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 193(18). [CrossRef]

- CADTH. (2016). Grey Matters: A practical tool for searching health-related grey literature. https://www.cadth.ca/grey-matters.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2025a). Emergency department crowding: Beyond Primary Care Access. CIHI. https://www.cihi.ca/en/primary-and-virtual-care-access-emergency-department-visits-for-primary-care-conditions/emergency-department-crowding-beyond-primary-care-access.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2025b). NACRS emergency department visits and lengths of stay. CIHI. https://www.cihi.ca/en/nacrs-emergency-department-visits-and-lengths-of-stay.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2025c). Frequent emergency room visits for help with mental health and substance use. CIHI. https://www.cihi.ca/en/indicators/frequent-emergency-room-visits-for-help-with-mental-health-and-substance-use.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2025d). List of updated indicators and contextual measures, July 2025. CIHI. https://www.cihi.ca/en/list-of-updated-indicators-and-contextual-measures-july-2025.

- Coccolini, F., Stahel, P. F., Montori, G., Biffl, W., Horer, T. M., Catena, F., Kluger, Y., Moore, E. E., Peitzman, A. B., Ivatury, R., Coimbra, R., Fraga, G. P., Pereira, B., Rizoli, S., Kirkpatrick, A., Leppaniemi, A., Manfredi, R., Magnone, S., Chiara, O., … Ansaloni, L. (2017a). Pelvic trauma: WSES classification and Guidelines. World Journal of Emergency Surgery, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Coccolini, F., Montori, G., Catena, F., Kluger, Y., Biffl, W., Moore, E. E., Reva, V., Bing, C., Bala, M., Fugazzola, P., Bahouth, H., Marzi, I., Velmahos, G., Ivatury, R., Soreide, K., Horer, T., ten Broek, R., Pereira, B. M., Fraga, G. P., … Ansaloni, L. (2017b). Splenic Trauma: WSES classification and guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. World Journal of Emergency Surgery, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Coccolini, F., Coimbra, R., Ordonez, C., Kluger, Y., Vega, F., Moore, E. E., Biffl, W., Peitzman, A., Horer, T., Abu-Zidan, F. M., Sartelli, M., Fraga, G. P., Cicuttin, E., Ansaloni, L., Parra, M. W., Millán, M., DeAngelis, N., Inaba, K., Velmahos, G., … Catena, F. (2020). Liver trauma: WSES 2020 guidelines. World Journal of Emergency Surgery, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Dobson, G. R., Chau, A., Denomme, J., Frost, S., Fuda, G., Mc Donnell, C., Milkovich, R., Milne, A. D., Sparrow, K., Subramani, Y., & Young, C. (2025). Guidelines to the practice of anesthesia—Revised edition 2025. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal Canadien d’anesthésie, 72(1), 15–63. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A., Yousefifard, M., Kazemi, H. M., Rasouli, H. R., & Safari, S. (2014). Diagnostic accuracy of chest ultrasonography versus chest radiography for pneumothorax detection: A meta-analysis. Tanaffos, 13(4), 29–37.

- Eli Lilly Canada. (2020). ZYPREXA intramuscular (olanzapine) product monograph. Toronto, Canada: Eli Lilly Canada. https://pi.lilly.com/ca/zyprexa-ca-pm.pdf.

- Fathi, M., Mirjafari, A., Yaghoobpoor, S., Ghanikolahloo, M., Sadeghi, Z., Bahrami, A., Myers, L., & Gholamrezanezhad, A. (2024). Diagnostic utility of whole-body computed tomography/pan-scan in trauma: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. Emergency Radiology, 31(2), 251–268. [CrossRef]

- Flammia, F., Chiti, G., Trinci, M., Danti, G., Cozzi, D., Grassi, R., Palumbo, P., Bruno, F., Agostini, A., Fusco, R., Granata, V., Giovagnoni, A., & Miele, V. (2022). Optimization of CT protocol in polytrauma patients: an update. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences, 26(7), 2543–2555. [CrossRef]

- Franco Vega, M. C., Ait Aiss, M., George, M., Day, L., Mbadugha, A., Owens, K., Sweeney, C., Chau, S., Escalante, C., & Bodurka, D. C. (2024). Enhancing Implementation of the I-PASS Handoff Tool Using a Provider Handoff Task Force at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety, 50(8), 560–568. [CrossRef]

- Gilyard, S., Shinn, K., Nezami, N., Findeiss, L. K., Dariushnia, S., Grant, A. A., Hawkins, C. M., Peters, G. L., Majdalany, B. S., Newsome, J., Bercu, Z. L., & Kokabi, N. (2020). Contemporary Management of Hepatic Trauma: What IRs Need to Know. Seminars in interventional radiology, 37(1), 35–43. [CrossRef]

- Green, S. P., Al-Saedy, S., Thomas, E. C., & Glaser, J. (2024). The utility of whole body computed tomography in trauma activations and the impact of incidental findings on Patient Management: A Review. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Hassankhani, A., Freeman, C. W., Banks, J., Parsons, M. S., Wessell, D. E., Hutchins, T. A., Lenchik, L., Burns, J., Eldaya, R. W., Griffith, B., Hickey, S. M., Khan, M. A., Lawrence, B., Paisley, T. S., Reitman, C., Ropper, A. E., Shah, V. N., Steenburg, S. D., Timpone, V. M., … Policeni, B. (2025). ACR appropriateness criteria® Acute Spinal Trauma: 2024 update. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 22(5). [CrossRef]

- Heilman, J. A., Flanigan, M., Nelson, A., Johnson, T., & Yarris, L. M. (2016). Adapting the I-PASS Handoff Program for Emergency Department Inter-Shift Handoffs. The western journal of emergency medicine, 17(6), 756–761. [CrossRef]

- Holmstrom, A. L., Ott, K. C., Weiss, H. K., Ellis, R. J., Hungness, E. S., Shapiro, M. B., & Yang, A. D. (2021). Improving trauma tertiary survey performance and missed injury identification using an education-based quality improvement initiative. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery, 90(6), 1048–1053. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., Ma, Y., Jiang, S., Ye, L., Zheng, Z., Xu, Y., & Zhang, M. (2014). Comparison of whole-body computed tomography vs selective radiological imaging on outcomes in major trauma patients: a meta-analysis. Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation, and emergency medicine, 22, 54. [CrossRef]

- Keijzers, G. B., Giannakopoulos, G. F., Del Mar, C., Bakker, F. C., & Geeraedts, L. M. (2012). The effect of tertiary surveys on missed injuries in trauma: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. Y., Biffl, W., Bokhari, F., Brakenridge, S., Chao, E., Claridge, J. A., Fraser, D., Jawa, R., Kasotakis, G., Kerwin, A., Khan, U., Kurek, S., Plurad, D., Robinson, B. R. H., Stassen, N., Tesoriero, R., Yorkgitis, B., & Como, J. J. (2020). Evaluation and management of Blunt Cerebrovascular Injury: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the surgery of trauma. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 88(6), 875–887. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J., Emory, J., Sousa, S., Thompson, D., Jenkins, K., Bettencourt, A. P., McLaughlin, M. K., & Russell-Babin, K. (2024). Implementing the Brøset Violence Checklist in the ED. The American journal of nursing, 124(7), 52–60. [CrossRef]

- Leung, V., Sastry, A., Woo, T. D., & Jones, H. R. (2015). Implementation of a split-bolus single-pass CT protocol at a UK major trauma centre to reduce excess radiation dose in trauma pan-CT. Clinical Radiology, 70(10), 1110–1115. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D., Rang, L., Kim, D., Robichaud, L., Kwan, C., Pham, C., Shefrin, A., Ritcey, B., Atkinson, P., Woo, M., Jelic, T., Dallaire, G., Henneberry, R., Turner, J., Andani, R., Demsey, R., & Olszynski, P. (2019). Recommendations for the use of point-of-care ultrasound (pocus) by emergency physicians in Canada. CJEM, 21(6), 721–726. [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J., Sampson, M., Salzwedel, D. M., Cogo, E., Foerster, V., & Lefebvre, C. (2016). Press peer review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 guideline statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 75, 40–46. [CrossRef]

- Netherton, S., Milenkovic, V., Taylor, M., & Davis, P. J. (2019). Diagnostic accuracy of eFAST in the trauma patient: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CJEM, 21(6), 727–738. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M. B., Humble, S. S., Cullinane, D. C., Day, M. A., Jawa, R. S., Devin, C. J., Delozier, M. S., Smith, L. M., Smith, M. A., Capella, J. M., Long, A. M., Cheng, J. S., Leath, T. C., Falck-Ytter, Y., Haut, E. R., & Como, J. J. (2015). Cervical spine collar clearance in the obtunded adult blunt trauma patient. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 78(2), 430–441. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2025). Trauma and violence-informed approaches to policy and practice. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/health-risks-safety/trauma-violence-informed-approaches-policy-practice.html.

- Rethlefsen, M. L., Kirtley, S., Waffenschmidt, S., Ayala, A. P., Moher, D., Page, M. J., Koffel, J. B., Blunt, H., Brigham, T., Chang, S., Clark, J., Conway, A., Couban, R., de Kock, S., Farrah, K., Fehrmann, P., Foster, M., Fowler, S. A., Glanville, J., … Young, S. (2021). Prisma-S: An extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Roppolo, L. P., Morris, D. W., Khan, F., Downs, R., Metzger, J., Carder, T., Wong, A. H., & Wilson, M. P. (2020). Improving the management of acutely agitated patients in the emergency department through implementation of Project BETA (Best Practices in the Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation). Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians open, 1(5), 898–907. [CrossRef]

- Sammut, D., Hallett, N., Lees-Deutsch, L., & Dickens, G. L. (2023). A Systematic Review of Violence Risk Assessment Tools Currently Used in Emergency Care Settings. Journal of emergency nursing, 49(3), 371–386.e5. [CrossRef]

- Shyu, J. Y., Khurana, B., Soto, J. A., Biffl, W. L., Camacho, M. A., Diercks, D. B., Glanc, P., Kalva, S. P., Khosa, F., Meyer, B. J., Ptak, T., Raja, A. S., Salim, A., West, O. C., & Lockhart, M. E. (2020). ACR appropriateness criteria® major blunt trauma. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 17(5). [CrossRef]

- Sierink, J. C., Treskes, K., Edwards, M. J., Beuker, B. J., den Hartog, D., Hohmann, J., Dijkgraaf, M. G., Luitse, J. S., Beenen, L. F., Hollmann, M. W., Goslings, J. C., & REACT-2 study group (2016). Immediate total-body CT scanning versus conventional imaging and selective CT scanning in patients with severe trauma (REACT-2): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 388(10045), 673–683. [CrossRef]

- Soares, B. P., Shih, R. Y., Utukuri, P. S., Adamson, M., Austin, M. J., Brown, R. K. J., Burns, J., Cacic, K., Chu, S., Crone, C., Ivanidze, J., Jackson, C. D., Kalnins, A., Potter, C. A., Rosen, S., Soderlund, K. A., Thaker, A. A., Wang, L. L., & Policeni, B. (2024). ACR appropriateness criteria® altered mental status, coma, delirium, and psychosis: 2024 update. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 21(11). [CrossRef]

- Stengel, D., Mutze, S., Güthoff, C., Weigeldt, M., von Kottwitz, K., Runge, D., Razny, F., Lücke, A., Müller, D., Ekkernkamp, A., & Kahl, T. (2020). Association of Low-Dose Whole-Body Computed Tomography with Missed Injury Diagnoses and Radiation Exposure in Patients with Blunt Multiple Trauma. JAMA surgery, 155(3), 224–232. [CrossRef]

- Stiell, I. G., Wells, G. A., Vandemheen, K., Clement, C., Lesiuk, H., Laupacis, A., McKnight, R. D., Verbeek, R., Brison, R., Cass, D., Eisenhauer, M. E., Greenberg, G., & Worthington, J. (2001a). The Canadian CT Head Rule for patients with minor head injury. Lancet (London, England), 357(9266), 1391–1396. [CrossRef]

- Stiell, I. G., Wells, G. A., Vandemheen, K. L., Clement, C. M., Lesiuk, H., De Maio, V. J., Laupacis, A., Schull, M., McKnight, R. D., Verbeek, R., Brison, R., Cass, D., Dreyer, J., Eisenhauer, M. A., Greenberg, G. H., MacPhail, I., Morrison, L., Reardon, M., & Worthington, J. (2001b). The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA, 286(15), 1841–1848. [CrossRef]

- Stiell, I. G., Clement, C. M., McKnight, R. D., Brison, R., Schull, M. J., Rowe, B. H., Worthington, J. R., Eisenhauer, M. A., Cass, D., Greenberg, G., MacPhail, I., Dreyer, J., Lee, J. S., Bandiera, G., Reardon, M., Holroyd, B., Lesiuk, H., & Wells, G. A. (2003). The Canadian C-spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. The New England journal of medicine, 349(26), 2510–2518. [CrossRef]

- Stone, A., Salehmohamed, Q., & Stark, B. (2023). Point-of-care emergency clinical summary: Treating acute agitation with ketamine in the emergency department. Emergency Care BC. https://emergencycarebc.ca/clinical_resource/clinical-summary/treating-acute-agitation-with-ketamine-in-the-emergency-department/. /.

- Varner, C. (2023). Without more acute care beds, hospitals are on their own to grapple with emergency department crises. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 195(34). [CrossRef]

- Xie, E. C., Chan, K., Khangura, J. K., Koh, J. J.-K., Orkin, A. M., Sheikh, H., Hayman, K., Gupta, S., Kumar, T., Hulme, J., Mrochuk, M., & Dong, K. (2022). CAEP position statement on improving emergency care for persons experiencing homelessness: Executive summary. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 24(4), 369–375. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).