Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Cold Cataracts: The Epitome of β/γ-Crystallin Phase Separation

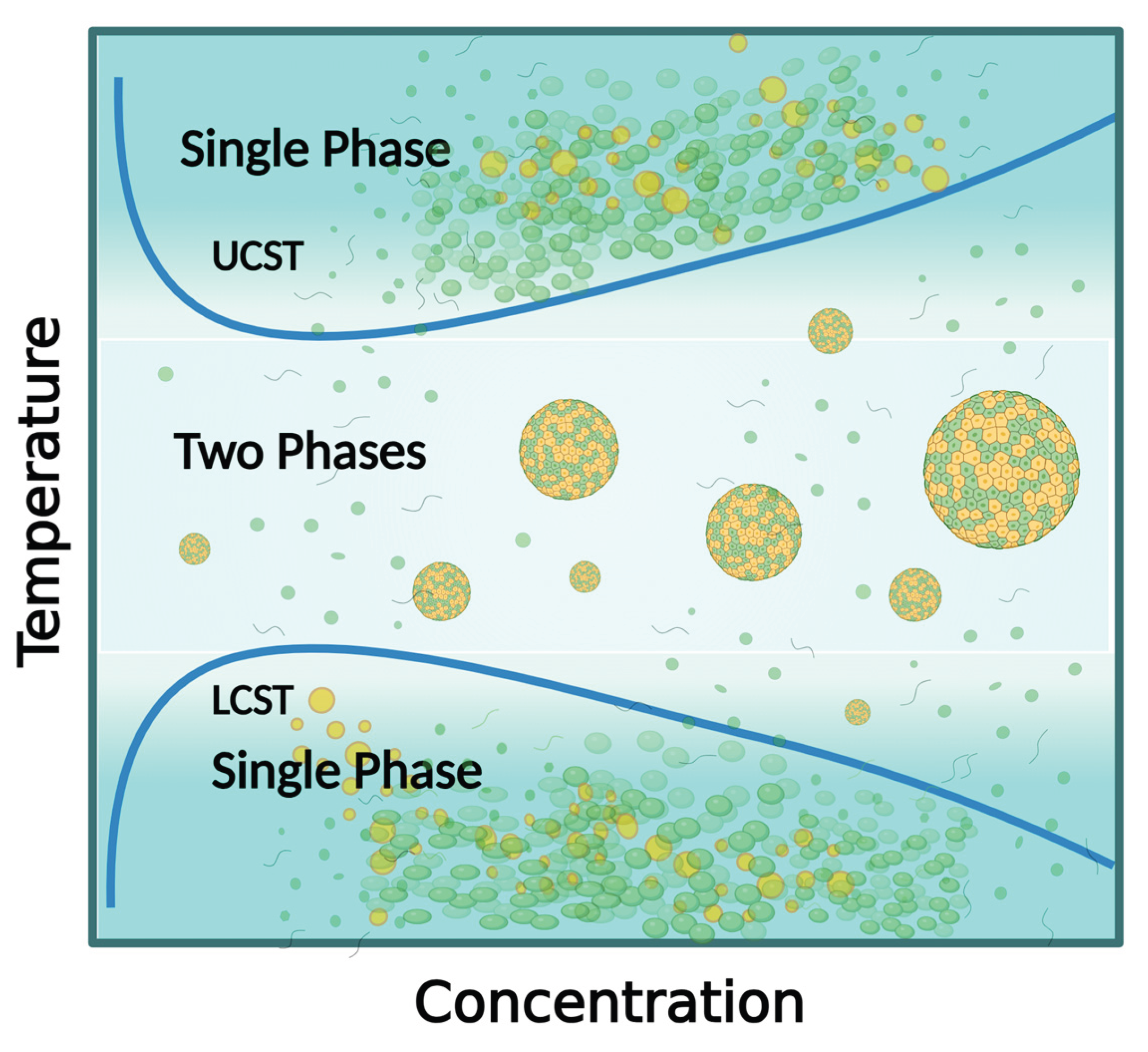

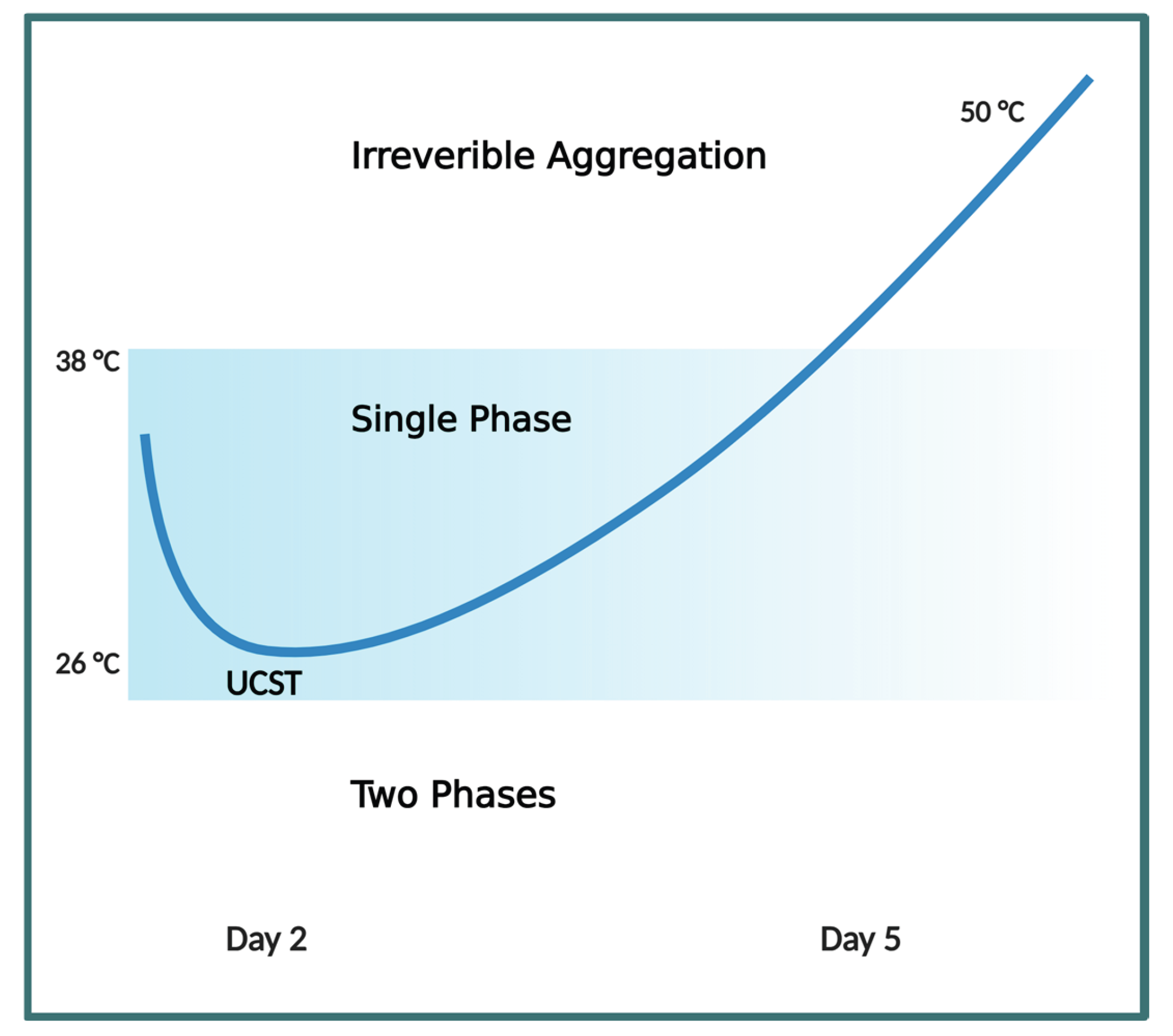

2.1. Phase Separation of β/γ-Crystallins is Dependent Upon Critical Solution Temperatures

2.2. The Irreversible Aggregation of Crystallins by Sodium Selenite

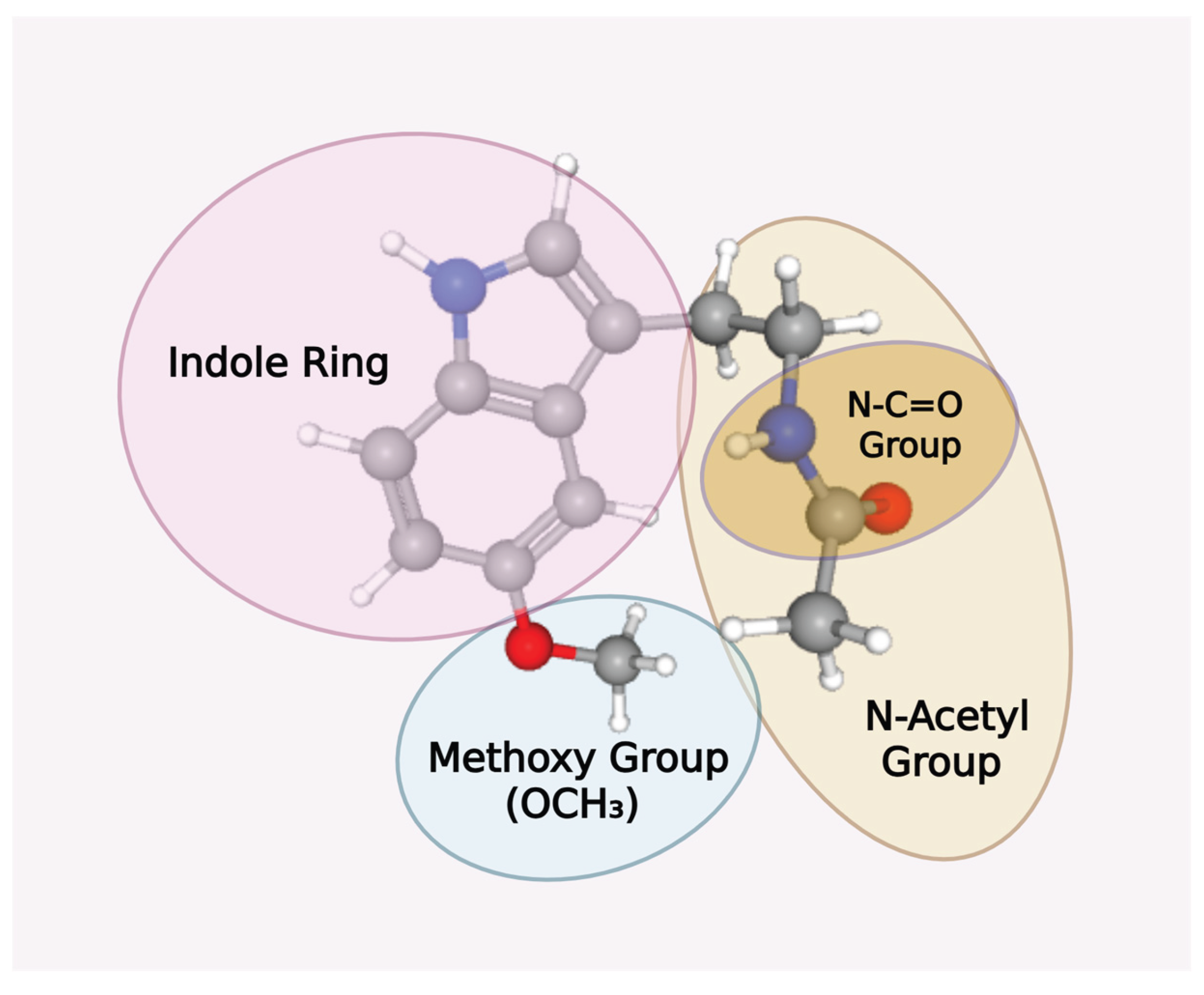

3. The Significance of Melatonin and its Indole Ring in Crystallin Redox Chemistry

3.1. The Free Radical Scavenging Cascade Sets Melatonin Apart from Other Antioxidants

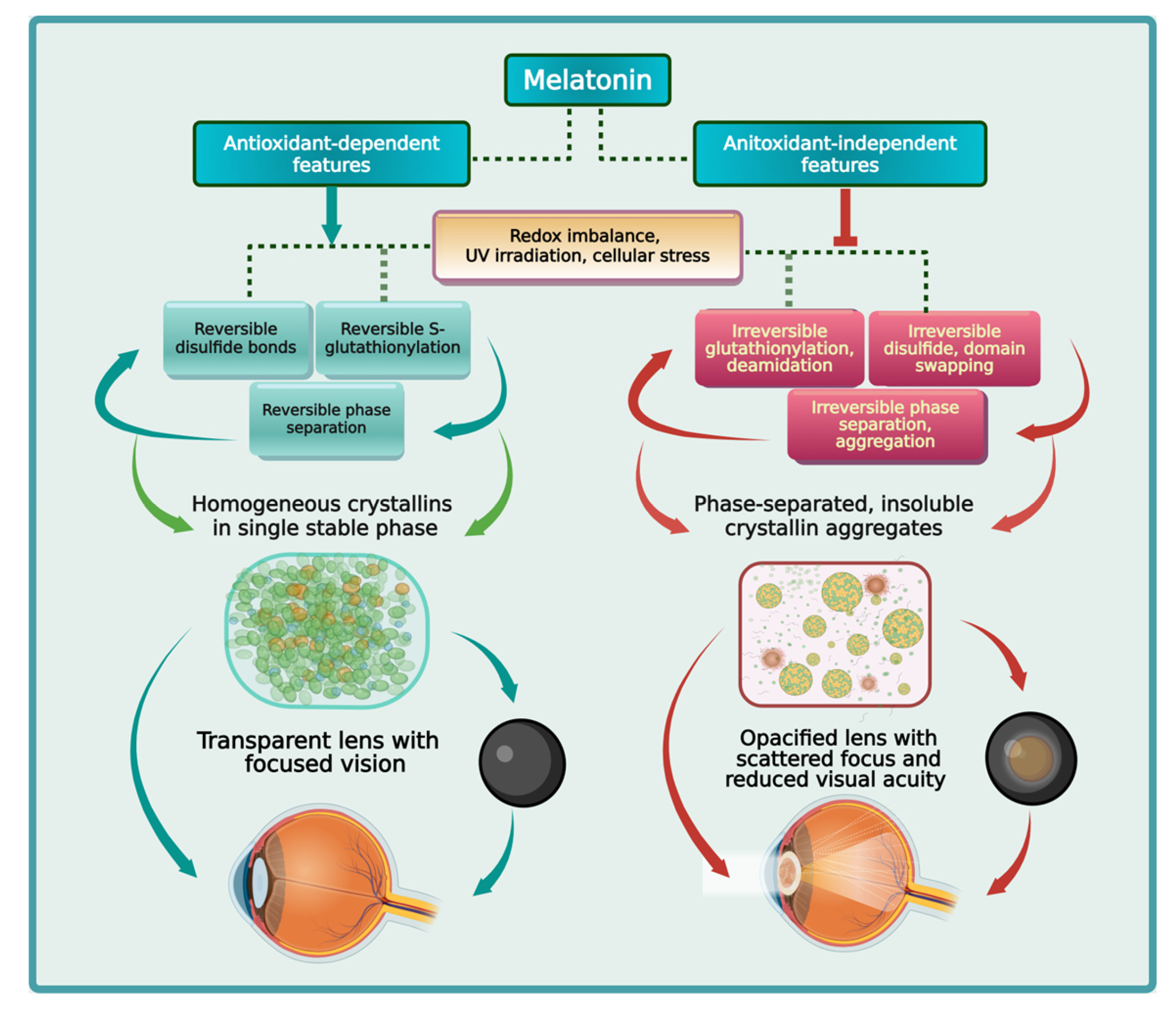

3.2. The Relevance of Maintaining a Balanced Lens Redox Environment in the Prevention of Phase Separation and Aggregation

4. The Redox Chemistry of Glutathione, β/γ Crystallins, and Disulfide Bonds: Location and Composition Determines the Outcome of Phase Separation and Aggregation in the Lens

4.1. Disulfide Bonds are Tunable Levers of Phase Separation

4.2. Location and Aging Determine the Differential Glutathione Concentration in the Lens

4.3. The Differential Location of Crystallins Determines Refractive Index and Susceptibility to Aggregation

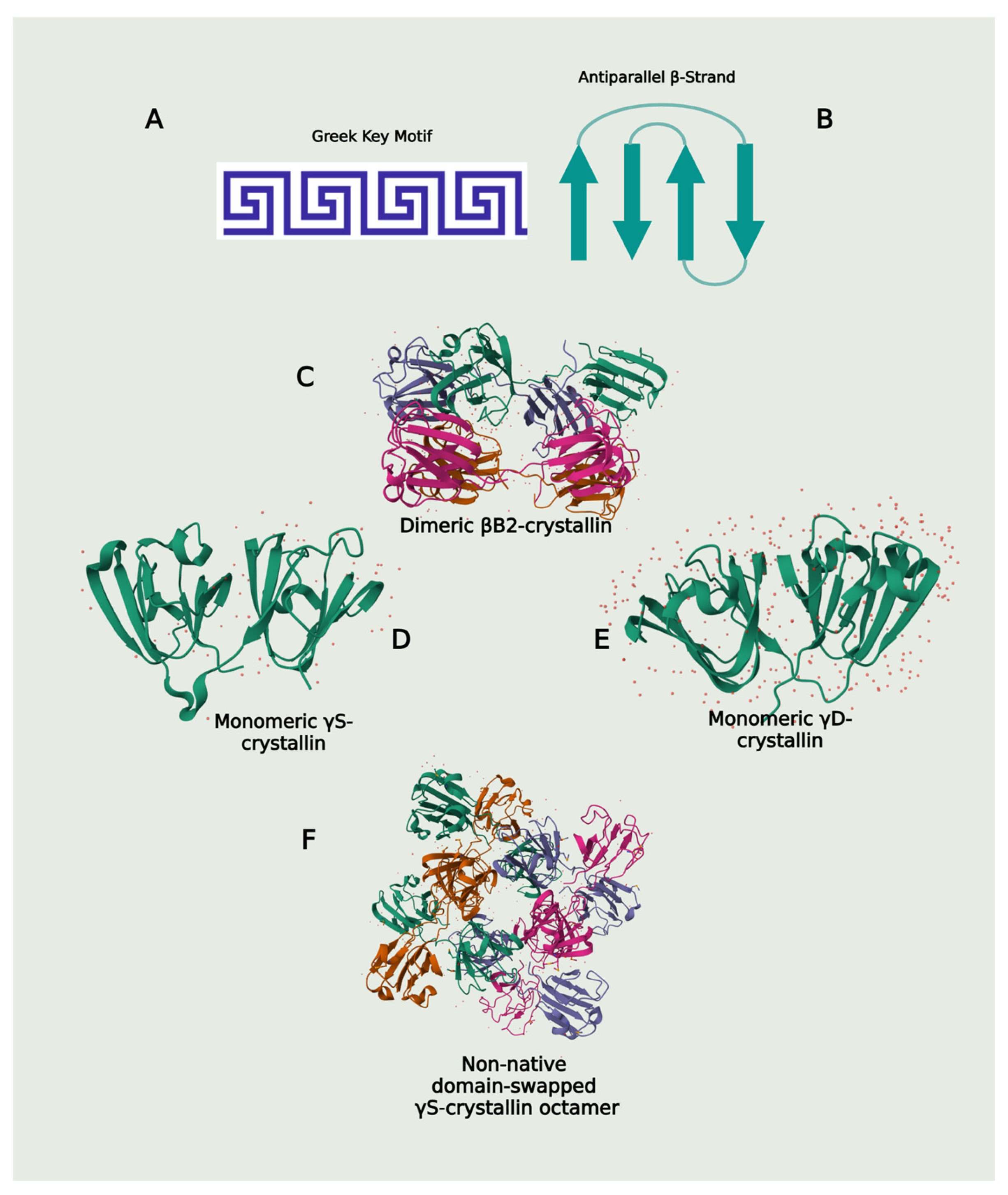

4.3.1. The Greek Key Motif Maintains High Refractive Index, Kinetic and Structural Stability in β/γ-crystallins

4.3.2. The Interactions Between Aromatic and Sulfur Residues in Greek Key Motifs Contribute to Lens Thermal Stability, Structural Integrity, and Transparency

4.3.3. Domain Swapping and Hydrophobic Interactions: Trading Protein Aggregation for Increased Thermodynamic Stability

4.4. Cysteines in β/γ-crystallins: Beyond the Role of Phase Separation Redox Rheostats

4.4.1. Exposed Cys in β/γ-crystallins Form Non-Native Disulfides Under Oxidizing Conditions

4.4.2. Exposed Cys in γD-Crystallins Prevents Nucleation in Phase Separation

4.5. The Lens Redox Environment Dictates the Fate of Non-Native Disulfide Bonds in β/γ-Crystallins

4.5.1. Structural Frustration from Disulfides Eventually Results in Aggregation

4.5.2. Transferring “Redox Hot Potatotes”: Playing Musical Chair with Protein Aggregation

4.5.3. Irreversible Deamidation Decreases Stability and Increases Aggregation of β/γ-Crystallins

5. Melatonin: The Multifaceted Regulation of Crystallin Phase Separation and Protein Aggregation in Crystallins

5.1. Melatonin Prevents Phase Separation and Aggregation via Van der Waals Forces, Hydrogen Bonds, and Hydrophobic Interactions

5.1.1. The Promotion and Inhibition of Phase Separation by Van der Waals Forces: The Dynamic Relationships Between Entropy, Enthalpy, and the Hydrophobic Effect

5.1.2. Melatonin Binds with Exposed Hydrophobic Residues to Prevent Phase Separation and Aggregation

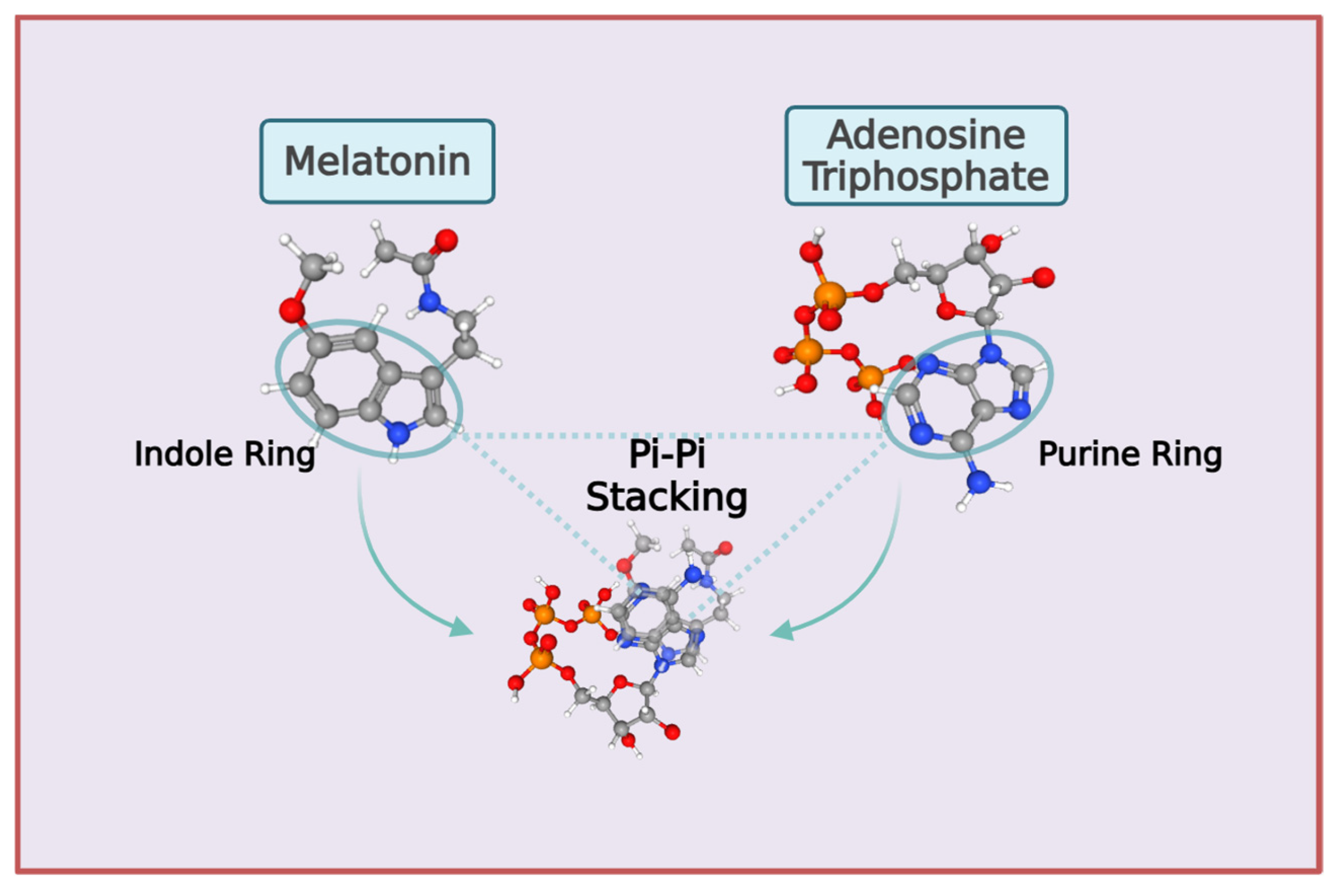

5.2. The Synergy Between Melatonin and the Hydrophilic ATP Prevents Phase Separation and Aggregation of Crystallins

5.3. Melatonin Prevents Lipid Peroxidation-Induced α-Crystallin Membrane Aggregation by Enhancing Cholesterol Liquid-Ordered Domain Stability

5.3.1. Increased Chol in Membranes Reduces Aggregation of α-Crystallins

5.3.2. Membrane Lipid Peroxidation Promotes Extensive Aggregation of α-Crystallins

5.3.3. Melatonin Increases Chol in Membranes and Prevents Lipid Peroxidation by Promoting Phase Separation of Lipid Domains and Dampening Dissipative Processes

5.4. Melatonin Determines the Outcome of Ultraviolet Exposure in the Human Lens

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BC | Biomolecular condensate |

| Chol | Cholesterol |

| Cys | Cysteine |

| D, | Lateral diffusion coefficient |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| LO | Liquid-ordered |

| LD | Liquid-disordered |

| Met | Methionine |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| Phe | Phenylalanine |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Tph | Phase separation temperature |

| Trp | Tryptophan |

| Tyr | Tyrosine |

| UCST | Upper critical solution temperature |

| LCST | Lower critical solution temperature |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| vdW | Van der Waals |

| WT | Wild-type |

References

- Roskamp, K.W.; Paulson, C.N.; Brubaker, W.D.; Martin, R.W. Function and Aggregation in Structural Eye Lens Crystallins. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Magone, M.T.; Schuck, P. The Role of Macromolecular Crowding in the Evolution of Lens Crystallins with High Molecular Refractive Index. Phys. Biol. 2011, 8, 046004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Rodríguez-Vallejo, M.; Martínez, J.; Tauste, A.; Piñero, D.P. From Presbyopia to Cataracts: A Critical Review on Dysfunctional Lens Syndrome. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 2018, 4318405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescosolido, N.; Barbato, A.; Giannotti, R.; Komaiha, C.; Lenarduzzi, F. Age-Related Changes in the Kinetics of Human Lenses: Prevention of the Cataract. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 9, 1506–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study; GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators Global Estimates on the Number of People Blind or Visually Impaired by Cataract: A Meta-Analysis from 2000 to 2020. EYE 2024, 38, 2156–2172. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, G.; Gan, Q.; Yang, T.; Liao, P.; Liang, H. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cataract: A Comprehensive Analysis and Projections from 1990 to 2021. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0326263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Friedrich, M.G.; Truscott, R.J.W.; Schey, K.L. Identification of Age- and Cataract-Related Changes in High-Density Lens Protein Aggregates. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, K.; Guo, Z.-X.; Wan, X.-H. Effect of Lens Crystallins Aggregation on Cataract Formation. Exp. Eye Res. 2025, 253, 110288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, P.V. The Pulling, Pushing and Fusing of Lens Fibers: A Role for Rho GTPases. Cell Adh. Migr. 2008, 2, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosas, A.B.; Carver, J.A. Eye Lens Crystallins: Remarkable Long--lived Proteins. In Long--lived Proteins in Human Aging and Disease; 2021; pp. 59–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, J.; Tan, Q.; Šikić, H.; Taber, L.A.; Bassnett, S. The Effect of Fibre Cell Remodelling on the Power and Optical Quality of the Lens. J. R. Soc. Interface 2023, 20, 20230316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Brown, P.H.; Magone, M.T.; Schuck, P. The Molecular Refractive Function of Lens γ-Crystallins. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 411, 680–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschek, J.; Braun, N.; Franzmann, T.M.; Georgalis, Y.; Haslbeck, M.; Weinkauf, S.; Buchner, J. The Eye Lens Chaperone Alpha-Crystallin Forms Defined Globular Assemblies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 13272–13277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vendra, V.P.R.; Khan, I.; Chandani, S.; Muniyandi, A.; Balasubramanian, D. Gamma Crystallins of the Human Eye Lens. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1860, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, R.H.; Campbell, M.C.; Munger, R.; Fernald, R.D. Refractive Index Distribution and Spherical Aberration in the Crystalline Lens of the African Cichlid Fish Haplochromis Burtoni. Vision Res. 1994, 34, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.J.; Mirarefi, A.Y.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Zukoski, C.F.; Devries, A.L.; Cheng, C.-H.C. Cold-Stable Eye Lens Crystallins of the Antarctic Nototheniid Toothfish Dissostichus Mawsoni Norman. J. Exp. Biol. 2004, 207, 4633–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, Y.; Rezabkova, L.; Wu, Z.; Wistow, G.; Schuck, P. Solution Properties of γ-Crystallins: Hydration of Fish and Mammal γ-Crystallins: Hydration of Fish and Mammal γ-Crystallins. Protein Sci. 2014, 23, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaye, M.; Tardieu, A. Short-Range Order of Crystallin Proteins Accounts for Eye Lens Transparency. Nature 1983, 302, 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.; Lin, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, X.; Cui, L. Unveiling the Dynamic Drivers: Phase Separation’s Pivotal Role in Stem Cell Biology and Therapeutic Potential. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasmeh, P.; Doronin, R.; Wagner, A. The Length Scale of Multivalent Interactions Is Evolutionarily Conserved in Fungal and Vertebrate Phase-Separating Proteins. Genetics 2022, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzorka, A.; Olaniyan, A.O.; Bawa, M. Biophysical Mechanisms of Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation in Biological Systems. Biophys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banani, S.F.; Lee, H.O.; Hyman, A.A.; Rosen, M.K. Biomolecular Condensates: Organizers of Cellular Biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappu, R.V. Phase Separation-A Physical Mechanism for Organizing Information and Biochemical Reactions. Dev. Cell 2020, 55, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Lin, Y. A Brief Guideline for Studies of Phase-Separated Biomolecular Condensates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 18, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borcherds, W.; Bremer, A.; Borgia, M.B.; Mittag, T. How Do Intrinsically Disordered Protein Regions Encode a Driving Force for Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation? arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza Masoodi, H.; Sadat Pourhosseini, R.; Bagheri, S. The Role of Nature of Aromatic Ring on Cooperativity between π–π Stacking and Ion–π Interactions: A Computational Study. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2023, 1220, 114022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doveiko, D.; Kubiak-Ossowska, K.; Chen, Y. Estimating Binding Energies of π-Stacked Aromatic Dimers Using Force Field-Driven Molecular Dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, H.; Kwon, I. Phase Separation of Low-Complexity Domains in Cellular Function and Disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 1412–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignon, G.L.; Zheng, W.; Kim, Y.C.; Mittal, J. Temperature-Controlled Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation of Disordered Proteins. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAinsh, M.; Dey, S.; Zhou, H.-X. Direct and Indirect Salt Effects on Homotypic Phase Separation. eLife 2024.

- Nandy, M.; Ganar, K.A.; Ippel, H.; Dijkgraaf, I.; Deshpande, S. PH-Responsive Phase Separation Dynamics of Intrinsically Disordered Peptides. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zigman, S.; Lerman, S. Properties of a Cold-Precipitable Protein Fraction in the Lens. Exp. Eye Res. 1965, 4, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitt, P.; Forciniti, D. Cold Cataracts: A Naturally Occurring Aqueous Two-Phase System. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 2000, 743, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, B.J.; McPheeters, M.T.; Jenkins, M.W.; Dupps, W.J., Jr; Rollins, A.M. Phase-Decorrelation Optical Coherence Tomography Measurement of Cold-Induced Nuclear Cataract. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivak, J.G.; Stuart, D.D.; Weerheim, J.A. Optical Performance of the Bovine Lens before and after Cold Cataract. Appl. Opt. 1992, 31, 3616–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; He, Y.; Guan, T. Protein and Water Distribution Across Visual Axis in Mouse Lens: A Confocal Raman MicroSpectroscopic Study for Cold Cataract. Front Chem 2021, 9, 767696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ping, X.; Zhou, J.; Ailifeire, H.; Wu, J.; Nadal-Nicolás, F.M.; Miyagishima, K.J.; Bao, J.; Huang, Y.; Cui, Y.; et al. Reversible Cold-Induced Lens Opacity in a Hibernator Reveals a Molecular Target for Treating Cataracts. J. Clin. Invest. 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, M.A.; Bettelheim, F.A. Cold Cataract Formation in Fish Lenses. Exp. Eye Res. 1979, 28, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierma, J.C.; Roskamp, K.W.; Ledray, A.P.; Kiss, A.J.; Cheng, C.-H.C.; Martin, R.W. Controlling Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation of Cold-Adapted Crystallin Proteins from the Antarctic Toothfish. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 5151–5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liedtke, W.B. Deconstructing Mammalian Thermoregulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, 1765–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, B.M. Freeze Avoidance in a Mammal: Body Temperatures below 0 Degree C in an Arctic Hibernator. Science 1989, 244, 1593–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, C.; Singh, M.; Nair, A.; Aglyamov, S.; Larin, K. Optical Coherence Elastography of Cold Cataract in Porcine Lens. J. Biomed. Opt. 2019, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.A.; Schurtenberger, P.; Thurston, G.M.; Benedek, G.B. Binary Liquid Phase Separation and Critical Phenomena in a Protein/water Solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1987, 84, 7079–7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, J.; Agarwal, S. Polymers with Upper Critical Solution Temperature in Aqueous Solution. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2012, 33, 1898–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadsworth, G.M.; Zahurancik, W.J.; Zeng, X.; Pullara, P.; Lai, L.B.; Sidharthan, V.; Pappu, R.V.; Gopalan, V.; Banerjee, P.R. RNAs Undergo Phase Transitions with Lower Critical Solution Temperatures. Nat. Chem. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapnistos, M.; Hinrichs, A.; Vlassopoulos, D.; Anastasiadis, S.H.; Stammer, A.; Wolf, B.A. Rheology of a Lower Critical Solution Temperature Binary Polymer Blend in the Homogeneous, Phase-Separated, and Transitional Regimes. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 7155–7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, C.N.; Bierma, J.C.; Pham, V.; Martin, R.W. γS-Crystallin Proteins from the Antarctic Nototheniid Toothfish: A Model System for Investigating Differential Resistance to Chemical and Thermal Denaturation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 13544–13553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wycherly, B.J.; Moak, M.A.; Christensen, M.J. High Dietary Intake of Sodium Selenite Induces Oxidative DNA Damage in Rat Liver. Nutr. Cancer 2004, 48, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, E.M.; Couri, D. Acute Toxicity of Sodium Selenite and Selenomethionine in Mice after ICV or IV Administration. Neurotoxicology 1981, 2, 383–386. [Google Scholar]

- Ostádalová, I.; Babický, A.; Obenberger, J. Cataract Induced by Administration of a Single Dose of Sodium Selenite to Suckling Rats. Experientia 1978, 34, 222–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabha, S.; Vallikannan, B. Fatty Acids Influence the Efficacy of Lutein in the Modulation of α-Crystallin Chaperone Function: Evidence from Selenite Induced Cataract Rat Model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 529, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Sha, T.-T.; Sun, G.-L.; Liang, S.-Z.; Yu, F.-F. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Involved in Age-Related Nuclear Cataract Induced by Sodium Selenite. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.I.; Steele, J.E. Phase-Separation Inhibitors and Prevention of Selenite Cataract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992, 89, 1720–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, T.R.; David, L.L.; Anderson, R.S. Selenite Decreases Phase Separation Temperature in Rat Lens. Exp. Eye Res. 1986, 42, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitton, K.P.; Hess, J.L.; Bunce, G.E. Causes of Decreased Phase Transition Temperature in Selenite Cataract Model. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1995, 36, 914–924. [Google Scholar]

- Bloemendal, H.; de Jong, W.; Jaenicke, R.; Lubsen, N.H.; Slingsby, C.; Tardieu, A. Ageing and Vision: Structure, Stability and Function of Lens Crystallins. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2004, 86, 407–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Garcia, C.M.; Shui, Y.-B.; Beebe, D.C. Expression and Regulation of Alpha-, Beta-, and Gamma-Crystallins in Mammalian Lens Epithelial Cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 3608–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorter, C.E.; De Haard-Hoekman, W.A.; Hermans, M.M.; Bloemendal, H.; De Jong, W.W. Differential Synthesis of Crystallins in the Developing Rat Eye Lens. Exp. Eye Res. 1990, 50, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slingsby, C.; Wistow, G.J. Functions of Crystallins in and out of Lens: Roles in Elongated and Post-Mitotic Cells. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2014, 115, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annunziata, O.; Ogun, O.; Benedek, G.B. Observation of Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation for Eye Lens gammaS-Crystallin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Asherie, N.; Lomakin, A.; Pande, J.; Ogun, O.; Benedek, G.B. Phase Separation in Aqueous Solutions of Lens Gamma-Crystallins: Special Role of Gamma S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996, 93, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.I.; Neuringer, J.R.; Benedek, G.B. Phase Separation and Lens Cell Age. J. Gerontol. 1983, 38, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pande, J.; Lomakin, A.; Fine, B.; Ogun, O.; Sokolinski, I.; Benedek, G. Oxidation of Gamma II-Crystallin Solutions Yields Dimers with a High Phase Separation Temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995, 92, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komariah, C.; Nugraha, J.; Sujuti, H. ; Others Mechanism of Sodium Selenite-Induced Cataract Through Autophagy in Wistar (Rattus Norvegicus) Rats. Journal of Medicinal and Chemical Sciences 2024, 7, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasmaini, O.; Hidayat, M.; Wati, R. The Effect of Topical Glutathione on Malondialdehyde Levels in Rat with Cataract-Induced Sodium Selenite. BioSci. Med. J. Biomed. Transl. Res. 2023, 7, 3356–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fris, M.; Tessem, M.-B.; Saether, O.; Midelfart, A. Biochemical Changes in Selenite Cataract Model Measured by High-Resolution MAS H NMR Spectroscopy. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2006, 84, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, S.D.; Hegde, K.R.; Kovtun, S. Inhibition of Selenite-Induced Cataract by Caffeine. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010, 88, e245–e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebryany, E.; Yu, S.; Trauger, S.A.; Budnik, B.; Shakhnovich, E.I. Dynamic Disulfide Exchange in a Crystallin Protein in the Human Eye Lens Promotes Cataract-Associated Aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 17997–18009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halverson-Kolkind, K.; Thorn, D.C.; Tovar-Ramirez, M.; Shakhnovich, E.; David, L.; Lampi, K. The Eye Lens Protein, γS Crystallin, Undergoes Glutathionylation-Induced Disulfide Bonding between Cysteines 22 and 26. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton-Baker, B.; Mehrabi, P.; Kwok, A.O.; Roskamp, K.W.; Rocha, M.A.; Sprague-Piercy, M.A.; von Stetten, D.; Miller, R.J.D.; Martin, R.W. Deamidation of the Human Eye Lens Protein γS-Crystallin Accelerates Oxidative Aging. Structure 2022, 30, 763–776.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Barnes, R.; Lin, Y.; Jeon, B.-J.; Najafi, S.; Delaney, K.T.; Fredrickson, G.H.; Shea, J.-E.; Hwang, D.S.; Han, S. Dehydration Entropy Drives Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation by Molecular Crowding. Communications Chemistry 2020, 3, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, T.; Alshareedah, I.; Wang, W.; Ngo, J.; Moosa, M.M.; Banerjee, P.R. Molecular Crowding Tunes Material States of Ribonucleoprotein Condensates. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Hou, C.; Ma, X.; Guo, S.; Zhang, H.; Shi, L.; Liao, C.; Zheng, B.; Ye, L.; Yang, L.; et al. Entropy-Enthalpy Compensations Fold Proteins in Precise Ways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jeon, B.-J.; Kim, S.; Jho, Y.; Hwang, D.S. Upper Critical Solution Temperature (UCST) Behavior of Coacervate of Cationic Protamine and Multivalent Anions. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Hecht, A.L.; Noble, S.A.; Huang, Q.; Gillilan, R.E.; Xu, A.Y. Understanding the Impacts of Molecular and Macromolecular Crowding Agents on Protein-Polymer Complex Coacervates. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 4771–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, X.-J.; Zhu, J.; Xi, Y.-B.; Yang, X.; Hu, L.-D.; Ouyang, H.; Patel, S.H.; Jin, X.; Lin, D.; et al. Lanosterol Reverses Protein Aggregation in Cataracts. Nature 2015, 523, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Lin, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, X.; Fan, F.; Yang, J.; Luo, Y.; Liu, X. Acetyl-11-Keto-Beta Boswellic Acid (AKBA) Protects Lens Epithelial Cells against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Injury and Attenuates Cataract Progression by Activating Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 927871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddirala, Y.; Tobwala, S.; Karacal, H.; Ercal, N. Prevention and Reversal of Selenite-Induced Cataracts by N-Acetylcysteine Amide in Wistar Rats. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, B.; Ergen, İ.; İlhan, N. The Protective Effect of Sesamol in the Selenite-Induced Experimental Cataract Model. Turkish Journal of Ophthalmology 2017, 47, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, H.; Sasaki, Y.; Shibata, T.; Sasaki, H.; Chhunchha, B.; Singh, D.P.; Kubo, E. Topical Instillation of N-Acetylcysteine and N-Acetylcysteine Amide Impedes Age-Related Lens Opacity in Mice. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebryany, E.; Chowdhury, S.; Woods, C.N.; Thorn, D.C.; Watson, N.E.; McClelland, A.A.; Klevit, R.E.; Shakhnovich, E.I. A Native Chemical Chaperone in the Human Eye Lens. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulet, D.R.; Knee, K.M.; King, J.A. Inhibition of Unfolding and Aggregation of Lens Protein Human Gamma D Crystallin by Sodium Citrate. Exp. Eye Res. 2011, 93, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, S.-S.; Lu, J.-H.; Wu, J.W.; Lin, T.-H.; Wang, S.S.-S. Protection of Human γD-Crystallin Protein from Ultraviolet C-Induced Aggregation by Ortho-Vanillin. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 261, 120023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, M.; Reiter, R.J.; Orhii, P.B.; Hara, M.; Poeggeler, B. Inhibitory Effect of Melatonin on Cataract Formation in Newborn Rats: Evidence for an Antioxidative Role for Melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 1994, 17, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.R.; Reiter, R.J.; Fujimori, O.; Oh, C.S.; Duan, Y.P. Cataractogenesis and Lipid Peroxidation in Newborn Rats Treated with Buthionine Sulfoximine: Preventive Actions of Melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 1997, 22, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karslioglu, I.; Ertekin, M.V.; Taysi, S.; Koçer, I.; Sezen, O.; Gepdiremen, A.; Koç, M.; Bakan, N. Radioprotective Effects of Melatonin on Radiation-Induced Cataract. J. Radiat. Res. 2005, 46, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yağci, R.; Aydin, B.; Erdurmuş, M.; Karadağ, R.; Gürel, A.; Durmuş, M.; Yiğitoğlu, R. Use of Melatonin to Prevent Selenite-Induced Cataract Formation in Rat Eyes. Curr. Eye Res. 2006, 31, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorsand, M.; Akmali, M.; Sharzad, S.; Beheshtitabar, M. Melatonin Reduces Cataract Formation and Aldose Reductase Activity in Lenses of Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rat. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 41, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Wei, C.; Sun, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Luo, J.; Yu, X.; He, J.; Ge, H.; Liu, P. Melatonin Inhibits Ferroptosis and Delays Age-Related Cataract by Regulating SIRT6/p-Nrf2/GPX4 and SIRT6/NCOA4/FTH1 Pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 157, 114048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourazaran, M.; Yousefi, R.; Moosavi-Movahedi, F.; Panahi, F.; Hong, J.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A. The Structural and Functional Consequences of Melatonin and Serotonin on Human αB-Crystallin and Their Dual Role in the Eye Lens Transparency. Biochim. Biophys. Acta: Proteins Proteomics 2023, 1871, 140928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Ding, D.; Bai, D.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D. Melatonin Biosynthesis Pathways in Nature and Its Production in Engineered Microorganisms. Synth Syst Biotechnol 2022, 7, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Choi, G.-H.; Back, K. Functional Characterization of Serotonin N-Acetyltransferase in Archaeon Thermoplasma Volcanium. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeland, R.; Cardinali, D.P.; Srinivasan, V.; Spence, D.W.; Brown, G.M.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. Melatonin—A Pleiotropic, Orchestrating Regulator Molecule. Prog. Neurobiol. 2011, 93, 350–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Rios, R.; Solà, M. The Relative Stability of Indole Isomers Is a Consequence of the Glidewell-Lloyd Rule. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sravanthi, T.V.; Manju, S.L. Indoles—A Promising Scaffold for Drug Development. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 91, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, B.; Nandi, B.; Paul, S.; Manna, S.; Maity, A.; Bandyopadhyay, K.; Panda, S.; Khan, S.A.; Nath, R.; Akhtar, M.J. Novel Indole-Based Synthetic Molecules in Cancer Treatment: Synthetic Strategies and Structure-Activity Relationship. Med. Drug Discov. 2025, 27, 100208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Han, C.; Mohammed, S.; Li, S.; Song, Y.; Sun, F.; Du, Y. Indole-Containing Pharmaceuticals: Targets, Pharmacological Activities, and SAR Studies. RSC Med. Chem. 2024, 15, 788–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Mayo, J.C.; Tan, D.-X.; Sainz, R.M.; Alatorre-Jimenez, M.; Qin, L. Melatonin as an Antioxidant: Under Promises but over Delivers. J. Pineal Res. 2016, 61, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz, A.; Reiter, R.J.; Topal, T.; Manchester, L.C.; Oter, S.; Tan, D.-X. Melatonin: An Established Antioxidant Worthy of Use in Clinical Trials. Mol. Med. 2009, 15, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manda, K.; Ohkubo, K.; Shoji, Y.; Zoardar, A.K.M.R.K.; Kamibayashi, M.; Ozawa, T.; Anzai, K.; Nakanishi, I. In Vitro Radical-Scavenging Mechanism of Melatonin and Its in Vivo Protective Effect against Radiation-Induced Lipid Peroxidation. Redox Biochem. Chem. 2023, 3-4, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.-X.; Reiter, R.J.; Manchester, L.C.; Yan, M.-T.; El-Sawi, M.; Sainz, R.M.; Mayo, J.C.; Kohen, R.; Allegra, M.; Hardeland, R. Chemical and Physical Properties and Potential Mechanisms: Melatonin as a Broad Spectrum Antioxidant and Free Radical Scavenger. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002, 2, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (2023) PubChem Compound Summary for CID 896, Melatonin Available online:. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Melatonin (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Tan, D.-X.; Manchester, L.C.; Esteban-Zubero, E.; Zhou, Z.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin as a Potent and Inducible Endogenous Antioxidant: Synthesis and Metabolism. Molecules 2015, 20, 18886–18906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sá Alves, F.R.; Barreiro, E.J.; Fraga, C.A.M. From Nature to Drug Discovery: The Indole Scaffold as a “Privileged Structure. ” Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lommel, R.; Bettens, T.; Barlow, T.M.A.; Bertouille, J.; Ballet, S.; De Proft, F. A Quantum Chemical Deep-Dive into the π-π Interactions of 3-Methylindole and Its Halogenated Derivatives-towards an Improved Ligand Design and Tryptophan Stacking. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Hattori, A. Aging-Induced Memory Loss due to Decreased N1-Acetyl-5-Methoxykynuramine, a Melatonin Metabolite, in the Hippocampus: A Potential Prophylactic Agent for Dementia. Neural Regeneration Res. [CrossRef]

- Slominski, A.T.; Kim, T.-K.; Janjetovic, Z.; Slominski, R.M.; Ganguli-Indra, G.; Athar, M.; Indra, A.K.; Reiter, R.J.; Kleszczyński, K. Melatonin and the Skin: Current Progress and Perspectives for Human Health. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocheva, G.; Bakalov, D.; Iliev, P.; Tafradjiiska-Hadjiolova, R. The Vital Role of Melatonin and Its Metabolites in the Neuroprotection and Retardation of Brain Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gu, D.; Huang, F.; Liu, J.; Yu, L.; Yu, X. Melatonin, a Phytohormone for Enhancing the Accumulation of High-Value Metabolites and Stress Tolerance in Microalgae: Applications, Mechanisms, and Challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 393, 130093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galano, A.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin and Its Metabolites vs Oxidative Stress: From Individual Actions to Collective Protection. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 65, e12514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.-X.; Manchester, L.C.; Terron, M.P.; Flores, L.J.; Reiter, R.J. One Molecule, Many Derivatives: A Never-Ending Interaction of Melatonin with Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species? J. Pineal Res. 2007, 42, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeland, R.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. Melatonin, a Potent Agent in Antioxidative Defense: Actions as a Natural Food Constituent, Gastrointestinal Factor, Drug and Prodrug. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 2005, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.X.; Manchester, L.C.; Burkhardt, S.; Sainz, R.M.; Mayo, J.C.; Kohen, R.; Shohami, E.; Huo, Y.S.; Hardeland, R.; Reiter, R.J. N1-Acetyl-N2-Formyl-5-Methoxykynuramine, a Biogenic Amine and Melatonin Metabolite, Functions as a Potent Antioxidant. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 2294–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardeland, R.; Poeggeler, B.; Niebergall, R.; Zelosko, V. Oxidation of Melatonin by Carbonate Radicals and Chemiluminescence Emitted during Pyrrole Ring Cleavage: Carbonate Radicals and Melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2003, 34, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galano, A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. On the Free Radical Scavenging Activities of Melatonin’s Metabolites, AFMK and AMK. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 54, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeland, R. Melatonin, Its Metabolites and Their Interference with Reactive Nitrogen Compounds. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Idle, J.R.; Krausz, K.W.; Tan, D.-X.; Ceraulo, L.; Gonzalez, F.J. Urinary Metabolites and Antioxidant Products of Exogenous Melatonin in the Mouse. J. Pineal Res. 2006, 40, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, C.; Krausz, K.W.; Idle, J.R.; Gonzalez, F.J. A Metabolomic Perspective of Melatonin Metabolism in the Mouse. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 1869–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, E.W.; Buonfiglio, F.; Voigt, A.M.; Bachmann, P.; Safi, T.; Pfeiffer, N.; Gericke, A. Oxidative Stress in the Eye and Its Role in the Pathophysiology of Ocular Diseases. Redox Biol. 2023, 68, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozov, S.V.; Filatova, E.V.; Orlov, A.A.; Volkova, A.V.; Zhloba, A.R.A.; Blashko, E.L.; Pozdeyev, N.V. N1-Acetyl-N2-Formyl-5-Methoxykynuramine Is a Product of Melatonin Oxidation in Rats. J. Pineal Res. 2003, 35, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Dong, L.; Song, Z.; Ge, H.; Cai, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, P. The Role of Melatonin as an Antioxidant in Human Lens Epithelial Cells. Free Radic. Res. 2013, 47, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Li, Z.; Wu, Z.; Lu, H. Phase Separation in Gene Transcription Control. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2023, 55, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, L.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, L.; He, J.; Zhou, M. Melatonin Stimulates Antioxidant Enzymes and Reduces Oxidative Stress in Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury: The Nrf2-ARE Signaling Pathway as a Potential Mechanism. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.W.; Kleszczyński, K.; Hardkop, L.H.; Kruse, N.; Zillikens, D. Melatonin Enhances Antioxidative Enzyme Gene Expression (CAT, GPx, SOD), Prevents Their UVR-Induced Depletion, and Protects against the Formation of DNA Damage (8-Hydroxy-2′-Deoxyguanosine) in Ex Vivo Human Skin. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 54, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.; Mayo, J.C.; Sainz, R.M.; Antolín, I.; Herrera, F.; Martín, V.; Reiter, R.J. Regulation of Antioxidant Enzymes: A Significant Role for Melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2004, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, J.C.; Sainz, R.M.; Antoli, I.; Herrera, F.; Martin, V.; Rodriguez, C. Melatonin Regulation of Antioxidant Enzyme Gene Expression. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 1706–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urata, Y.; Honma, S.; Goto, S.; Todoroki, S.; Iida, T.; Cho, S.; Honma, K.; Kondo, T. Melatonin Induces γ-Glutamylcysteine Synthetase Mediated by Activator Protein-1 in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 1999, 27, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, M.; Rodríguez, C.; Sáinz, R.M.; Antolín, I.; Menéndez-Peláez, A. Melatonin Increases Gene Expression for Antioxidant Enzymes in Rat Brain Cortex. J. Pineal Res. 1998, 24, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oloumi, H.; Maleki, M. Melatonin Modulates the Phytochelatin Synthase and Glutathione Synthase Gene Expression and the Antioxidant Performance of Soybean Plants Under Cadmium Stress. International Journal of Agronomy 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.-X.; Hardeland, R.; Manchester, L.C.; Galano, A.; Reiter, R.J. Cyclic-3-Hydroxymelatonin (C3HOM), a Potent Antioxidant, Scavenges Free Radicals and Suppresses Oxidative Reactions. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressmeyer, A.-R.; Mayo, J.C.; Zelosko, V.; Sáinz, R.M.; Tan, D.-X.; Poeggeler, B.; Antolín, I.; Zsizsik, B.K.; Reiter, R.J.; Hardeland, R. Antioxidant Properties of the Melatonin Metabolite N1-Acetyl-5-Methoxykynuramine (AMK): Scavenging of Free Radicals and Prevention of Protein Destruction. Redox Rep. 2003, 8, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, A.; Sheeja, A.A.; Janardanan, D. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity of Melatonin and Its Related Indolamines. Free Radic. Res. 2020, 54, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.-X.; Terron, M.P.; Flores, L.J.; Czarnocki, Z. Melatonin and Its Metabolites: New Findings Regarding Their Production and Their Radical Scavenging Actions. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2007, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Han, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, L.; Wei, Z.; Wang, F.; Wan, Y. Melatonin Protects Leydig Cells from HT-2 Toxin-Induced Ferroptosis and Apoptosis via Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase/glutathione -Dependent Pathway. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2023, 159, 106410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnir, O.Y.; Yaremii, I.M.; Pantsiuk, K.A.; Kushnir, O.O.; Yaremii, K.M.; Vlasova, K.V.; Vlasova, O.V. Carbohydrate Metabolism in the Rats’ Liver under Conditions of Light and Dark Deprivation and Correction by Melatonin. Wiad. Lek. 2025, 78, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, S.; Wen, H.; Liu, T.; Cai, J.; Du, D.; Zhu, D.; Chen, F.; Xia, C. Melatonin Decreases M1 Polarization via Attenuating Mitochondrial Oxidative Damage Depending on UCP2 Pathway in Prorenin-Treated Microglia. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0212138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.; Eljack, N.D.; Sani, M.-A.; Separovic, F.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Kopec, W.; Khandelia, H.; Cornelius, F.; Clarke, R.J. Membrane Accessibility of Glutathione. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1848, 2430–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Sharma, R.; Tan, D.-X.; Chuffa, L.G. de A.; da Silva, D.G.H.; Slominski, A.T.; Steinbrink, K.; Kleszczynski, K. Dual Sources of Melatonin and Evidence for Different Primary Functions. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkozi, H.A.; Wang, X.; Perez de Lara, M.J.; Pintor, J. Presence of Melanopsin in Human Crystalline Lens Epithelial Cells and Its Role in Melatonin Synthesis. Exp. Eye Res. 2017, 154, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, M.T.; Takahashi, N.; Abe, M.; Shimizu, K. Expression and Cellular Localization of Melatonin-Synthesizing Enzymes in the Rat Lens. J. Pineal Res. 2007, 42, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Itoh, M.T.; Miyata, M.; Ishikawa, S.; Sumi, Y. Detection of Melatonin, Its Precursors and Related Enzyme Activities in Rabbit Lens. Exp. Eye Res. 1999, 68, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder-Schmittbuhl, M.P.; Hicks, D.; Ribelayaga, C.P.; Tosini, G. Melatonin in the Mammalian Retina: Synthesis, Mechanisms of Action and Neuroprotection. J. Pineal Res. 2024, 76, e12951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmijewski, M.A.; Sweatman, T.W.; Slominski, A.T. The Melatonin-Producing System Is Fully Functional in Retinal Pigment Epithelium (ARPE-19). Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 307, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Dickson, E.J.; Jung, S.-R.; Koh, D.-S.; Hille, B. High Membrane Permeability for Melatonin. J. Gen. Physiol. 2016, 147, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.J.; Lopes, R.H.; Lamy-Freund, M.T. Permeability of Pure Lipid Bilayers to Melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 1995, 19, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehan, M.; Alsohim, A.S.; El-Fadly, G.; Tisa, L.S. Detoxification and Reduction of Selenite to Elemental Red Selenium by Frankia. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2019, 112, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieliszek, M.; Serrano Sandoval, S.N. The Importance of Selenium in Food Enrichment Processes. A Comprehensive Review. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 79, 127260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Hou, X.; Guo, Z.; Lei, X.; Peng, M. Biodegradation of Sodium Selenite by a Highly Tolerant Strain Rhodococcus Qingshengii PM1: Biochemical Characterization and Comparative Genome Analysis. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 9, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) as Pleiotropic Physiological Signalling Agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, K.; Schiavone, S.; Miller, F.J., Jr; Krause, K.-H. Reactive Oxygen Species: From Health to Disease. Swiss Med. Wkly 2012, 142, w13659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Berndt, C.; Holmgren, A. Metabolism of Selenium Compounds Catalyzed by the Mammalian Selenoprotein Thioredoxin Reductase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1790, 1513–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajner, S.M.; Rohenkohl, H.C.; Serrano, T.; Maia, A.L. Sodium Selenite Supplementation Does Not Fully Restore Oxidative Stress-Induced Deiodinase Dysfunction: Implications for the Nonthyroidal Illness Syndrome. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Boylan, M.; Selvam, A.; Spallholz, J.E.; Björnstedt, M. Redox-Active Selenium Compounds--from Toxicity and Cell Death to Cancer Treatment. Nutrients 2015, 7, 3536–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Han, B.; Li, Z.; Hua, F.; Huang, F.; Wei, W.; Yang, Y.; Xu, C. Sodium Selenite Induces Apoptosis by ROS-Mediated Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Human Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia NB4 Cells. Apoptosis 2009, 14, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, V.; Tomblin, J.; Yeager Armistead, M.; Murray, E. Selenium (sodium Selenite) Causes Cytotoxicity and Apoptotic Mediated Cell Death in PLHC-1 Fish Cell Line through DNA and Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Damage. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 87, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsamy, P.; Bidasee, K.R.; Shinohara, T. Selenite Cataracts: Activation of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Loss of Nrf2/Keap1-Dependent Stress Protection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 1794–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitton, K.P.; Hess, J.L.; Bunce, G.E. Free Amino Acids Reflect Impact of Selenite-Dependent Stress on Primary Metabolism in Rat Lens. Curr. Eye Res. 1997, 16, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algieri, C.; Oppedisano, F.; Trombetti, F.; Fabbri, M.; Palma, E.; Nesci, S. Selenite Ameliorates the ATP Hydrolysis of Mitochondrial F1FO-ATPase by Changing the Redox State of Thiol Groups and Impairs the ADP Phosphorylation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 210, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, L.B. The Basics of Thiols and Cysteines in Redox Biology and Chemistry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 80, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Averill-Bates, D.A. The Antioxidant Glutathione. Vitam. Horm. 2023, 121, 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, A.; Federici, G.; Bertini, E.; Piemonte, F. Analysis of Glutathione: Implication in Redox and Detoxification. Clin. Chim. Acta 2003, 333, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millis, K.K.; Weaver, K.H.; Rabenstein, D.L. Oxidation/reduction Potential of Glutathione. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 4144–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.J.; Hell, R. Glutathione Homeostasis and Redox-Regulation by Sulfhydryl Groups. Photosynth. Res. 2005, 86, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, K.; Nakaki, T. Glutathione in Cellular Redox Homeostasis: Association with the Excitatory Amino Acid Carrier 1 (EAAC1). Molecules 2015, 20, 8742–8758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filomeni, G.; Rotilio, G.; Ciriolo, M.R. Cell Signalling and the Glutathione Redox System. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002, 64, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquilano, K.; Baldelli, S.; Ciriolo, M.R. Glutathione: New Roles in Redox Signaling for an Old Antioxidant. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.R.; Hurrell, F.; Shannon, R.J.; Lin, T.-K.; Hirst, J.; Murphy, M.P. Reversible Glutathionylation of Complex I Increases Mitochondrial Superoxide Formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 19603–19610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, S.M.; Taylor, E.R.; Brown, S.E.; Dahm, C.C.; Costa, N.J.; Runswick, M.J.; Murphy, M.P. Glutaredoxin 2 Catalyzes the Reversible Oxidation and Glutathionylation of Mitochondrial Membrane Thiol Proteins: Implications for Mitochondrial Redox Regulation and Antioxidant DEFENSE: Implications for Mitochondrial Redox Regulation and Antioxidant Defense. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 47939–47951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarelli, C.; Tozzi, G.; Pastore, A.; Bertini, E.; Piemonte, F. GSSG-Mediated Complex I Defect in Isolated Cardiac Mitochondria. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2010, 26, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dereven’kov, I.A.; Molodtsov, P.A.; Makarov, S.V. Kinetic and Mechanistic Studies of the First Step of the Reaction between Thiols and Selenite. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2020, 131, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tian, W.; Huang, K. Effect of Blood-Retinal Barrier Development on Formation of Selenite Nuclear Cataract in Rat. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 216, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyselova, Z. Different Experimental Approaches in Modelling Cataractogenesis: An Overview of Selenite-Induced Nuclear Cataract in Rats. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2010, 3, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulbay, M.; Wu, K.Y.; Nirwal, G.K.; Bélanger, P.; Tran, S.D. Oxidative Stress and Cataract Formation: Evaluating the Efficacy of Antioxidant Therapies. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, B.; Davies, M.J.; Truscott, R.J. Formation of Hydroxyl Radicals in the Human Lens Is Related to the Severity of Nuclear Cataract. Exp. Eye Res. 2000, 70, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennari, F.; Sharma, V.K.; Pettine, M.; Campanella, L.; Millero, F.J. Reduction of Selenite by Cysteine in Ionic Media. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 124, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, M.F.; Augusteyn, R.C. Oxidation-Induced Mixed Disulfide and Cataract Formation: A Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2025, 14, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, C.; Kumar, A.; Lang, A.; Ohlenschläger, O. Cysteines and Disulfide Bonds as Structure-Forming Units: Insights from Different Domains of Life and the Potential for Characterization by NMR. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Jankoski, P.E.; Lee, L.D.; Dinakarapandian, D.M.; Chiu, T.-Y.; Swetman, W.S.; Wu, H.; Paravastu, A.K.; Clemons, T.D.; Rangachari, V. Reversible Disulfide Bond Cross-Links as Tunable Levers of Phase Separation in Designer Biomolecular Condensates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 25299–25311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Pan, T.; Zhou, L.; Ran, Y.; Zou, J.; Yan, X.; Wen, Z.; Lin, S.; Ren, A.; et al. Targeting a Key Disulfide Linkage to Regulate RIG-I Condensation and Cytosolic RNA-Sensing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2025, 27, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manteca, A.; Alonso-Caballero, Á.; Fertin, M.; Poly, S.; De Sancho, D.; Perez-Jimenez, R. The Influence of Disulfide Bonds on the Mechanical Stability of Proteins Is Context Dependent. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 13374–13380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, K.; Bose, S.K.; Chakrabarti, B.; Siezen, R.J. Structure and Stability of Gamma-Crystallins. II. Differences in Microenvironments and Spatial Arrangements of Cysteine Residues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1987, 911, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.S.; Trune, D.R.; Shearer, T.R. Histologic Changes in Selenite Cortical Cataract. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1988, 29, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pau, H.; Graf, P.; Sies, H. Glutathione Levels in Human Lens: Regional Distribution in Different Forms of Cataract. Exp. Eye Res. 1990, 50, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamei, A. Glutathione Levels of the Human Crystalline Lens in Aging and Its Antioxidant Effect against the Oxidation of Lens Proteins. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1993, 16, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackic, J.B.; Kannan, R.; Kaplowitz, N.; Zlokovic, B.V. Low de Novo Glutathione Synthesis from Circulating Sulfur Amino Acids in the Lens Epithelium. Exp. Eye Res. 1997, 64, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.C.; Grey, A.C.; Zahraei, A.; Donaldson, P.J. Age-Dependent Changes in Glutathione Metabolism Pathways in the Lens: New Insights into Therapeutic Strategies to Prevent Cataract Formation-A Review. Clin. Experiment. Ophthalmol. 2020, 48, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitson, J.A.; Sell, D.R.; Goodman, M.C.; Monnier, V.M.; Fan, X. Evidence of Dual Mechanisms of Glutathione Uptake in the Rodent Lens: A Novel Role for Vitreous Humor in Lens Glutathione Homeostasis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 3914–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Quan, Y.; Ma, B.; Gu, S.; Jiang, J.X. Mechano-Activated Connexin Hemichannels Mediate Intercellular Glutathione Transport and Support Lens Redox Homeostasis. Redox Biol. 2025, 85, 103767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Monnier, V.M.; Whitson, J. Lens Glutathione Homeostasis: Discrepancies and Gaps in Knowledge Standing in the Way of Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Exp. Eye Res. 2017, 156, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giblin, F.J. Glutathione: A Vital Lens Antioxidant. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 16, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Suzuki-Kerr, H.; Lim, C.J.J.; Martis, R.M.; Yang, F.O.; Carlos, E.; Donaldson, P.J.; Poulsen, R.C.; Lim, J.C. Light Influences Time-of-Day Differences in the Expression of Clock Genes and Redox Genes Involved in Glutathione Homeostasis in the Lens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, A.C.; Demarais, N.J.; West, B.J.; Donaldson, P.J. A Quantitative Map of Glutathione in the Aging Human Lens. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 437, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, J.V.; Gascó, E.; Sastre, J.; Pallardó, F.V.; Asensi, M.; Viña, J. Age-Related Changes in Glutathione Synthesis in the Eye Lens. Biochem. J. 1990, 269, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slingsby, C.; Wistow, G.J.; Clark, A.R. Evolution of Crystallins for a Role in the Vertebrate Eye Lens. Protein Sci. 2013, 22, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwitz, J.; Bova, M.P.; Ding, L.-L.; Haley, D.A.; Stewart, P.L. Lens α-Crystallin: Function and Structure. Eye 1999, 13, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, J. Alpha-Crystallin. Exp. Eye Res. 2003, 76, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, B.; Rao, C.M. Chaperone-like Activity and Temperature-Induced Structural Changes of α-Crystallin *. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 23559–23564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, B.; Ramakrishna, T.; Rao, C.M. Temperature Dependent Chaperone-like Activity of Alpha-Crystallin. FEBS Lett. 1995, 365, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Chen, Z.; Wei, Z.; Tian, L. Hydrophobic Interaction: A Promising Driving Force for the Biomedical Applications of Nucleic Acids. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 2020, 7, 2001048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.B.; Kumar, P.A.; Kumar, M.S. Chaperone-like Activity and Hydrophobicity of Alpha-Crystallin. IUBMB Life 2006, 58, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Spector, A. Absence of Low-Molecular-Weight Alpha Crystallin in Nuclear Region of Old Human Lenses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1976, 73, 3484–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynnerup, N.; Kjeldsen, H.; Heegaard, S.; Jacobsen, C.; Heinemeier, J. Radiocarbon Dating of the Human Eye Lens Crystallines Reveal Proteins without Carbon Turnover throughout Life. PLoS One 2008, 3, e1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.R.; Levchenko, V.A.; Blanksby, S.J.; Mitchell, T.W.; Williams, A.; Truscott, R.J.W. No Turnover in Lens Lipids for the Entire Human Lifespan. Elife 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappé, G.; Purkiss, A.G.; van Genesen, S.T.; Slingsby, C.; Lubsen, N.H. Explosive Expansion of Betagamma-Crystallin Genes in the Ancestral Vertebrate. J. Mol. Evol. 2010, 71, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnwal, R.P.; Jobby, M.K.; Devi, K.M.; Sharma, Y.; Chary, K.V.R. Solution Structure and Calcium-Binding Properties of M-Crystallin, a Primordial Betagamma-Crystallin from Archaea. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 386, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendra, V.; Thangapandian, M. The Importance of the Fourth Greek Key Motif of Human γD-Crystallin in Maintaining Lens Transparency-the Tale Told by the Tail. Mol. Vis. 2024, 30, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, E.G.; Thornton, J.M. The Greek Key Motif: Extraction, Classification and Analysis. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 1993, 6, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendra, V.P.R.; Agarwal, G.; Chandani, S.; Talla, V.; Srinivasan, N.; Balasubramanian, D. Structural Integrity of the Greek Key Motif in βγ-Crystallins Is Vital for Central Eye Lens Transparency. PLoS One 2013, 8, e70336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, I.A.; Flaugh, S.L.; Kosinski-Collins, M.S.; King, J.A. Folding and Stability of the Isolated Greek Key Domains of the Long-Lived Human Lens Proteins gammaD-Crystallin and gammaS-Crystallin. Protein Sci. 2007, 16, 2427–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yashchuk, V.M.; Kudrya, V.Y.; Levchenko, S.M.; Tkachuk, Z.Y.; Hovorun, D.M.; Mel’nik, V.I.; Vorob’yov, V.P.; Klishevich, G.V. Optical Response of the Polynucleotides-Proteins Interaction. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2011, 535, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, V.; Wistow, G. Acquired Disorder and Asymmetry in a Domain-Swapped Model for γ-Crystallin Aggregation. J. Mol. Biol. 2022, 434, 167559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, K.S.; Tripathi, V.; Das, R. A Conserved and Buried Edge-to-Face Aromatic Interaction in Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO) Has a Role in SUMO Stability and Function. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 6772–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Udgaonkar, J.B. Mutations of Evolutionarily Conserved Aromatic Residues Suggest That Misfolding of the Mouse Prion Protein May Commence in Multiple Ways. J. Neurochem. 2023, 167, 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-X.; Pang, X. Electrostatic Interactions in Protein Structure, Folding, Binding, and Condensation. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1691–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, C.N.; Treviño, S.; Prabhakaran, E.; Scholtz, J.M. Protein Structure, Stability and Solubility in Water and Other Solvents. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taricska, N.; Bokor, M.; Menyhárd, D.K.; Tompa, K.; Perczel, A. Hydration Shell Differentiates Folded and Disordered States of a Trp-Cage Miniprotein, Allowing Characterization of Structural Heterogeneity by Wide-Line NMR Measurements. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmingsen, J.M.; Gernert, K.M.; Richardson, J.S.; Richardson, D.C. The Tyrosine Corner: A Feature of Most Greek Key Beta-Barrel Proteins. Protein Sci. 1994, 3, 1927–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marazzi, M.; Navizet, I.; Lindh, R.; Frutos, L.M. Photostability Mechanisms in Human γB-Crystallin: Role of the Tyrosine Corner Unveiled by Quantum Mechanics and Hybrid Quantum Mechanics/molecular Mechanics Methodologies. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; King, J. Contributions of Aromatic Pairs to the Folding and Stability of Long-Lived Human γD-Crystallin. Protein Sci. 2011, 20, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, S.K.; Petsko, G.A. Aromatic-Aromatic Interaction: A Mechanism of Protein Structure Stabilization. Science 1985, 229, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, C.A.; Weber, D.S.; Warren, J.J. Clustering of Aromatic Amino Acid Residues around Methionine in Proteins. Biomolecules 2021, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, D.S.; Warren, J.J. The Interaction between Methionine and Two Aromatic Amino Acids Is an Abundant and Multifunctional Motif in Proteins. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 672, 108053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valley, C.C.; Cembran, A.; Perlmutter, J.D.; Lewis, A.K.; Labello, N.P.; Gao, J.; Sachs, J.N. The Methionine-Aromatic Motif Plays a Unique Role in Stabilizing Protein Structure. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 34979–34991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serebryany, E.; Martin, R.W.; Takahashi, G.R. The Functional Significance of High Cysteine Content in Eye Lens γ-Crystallins. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.L.; Mosoni, L.; Berlett, B.S.; Stadtman, E.R. Methionine Residues as Endogenous Antioxidants in Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996, 93, 15036–15040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, M.A.; Yurina, L.V.; Vasilyeva, A.D. Antioxidant Role of Methionine-Containing Intra- and Extracellular Proteins. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechtel, T.J.; Weerapana, E. From Structure to Redox: The Diverse Functional Roles of Disulfides and Implications in Disease. Proteomics 2017, 17, 1600391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgore, H.R.; Raines, R.T. N→π* Interactions Modulate the Properties of Cysteine Residues and Disulfide Bonds in Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 17606–17611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, G.; Foloppe, N.; Messens, J. Understanding the pK(a) of Redox Cysteines: The Key Role of Hydrogen Bonding. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 94–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, J.T.; Purkiss, A.G.; Smith, M.A.; Evans, P.; Goodfellow, J.M.; Slingsby, C. Unfolding Crystallins: The Destabilizing Role of a Beta-Hairpin Cysteine in betaB2-Crystallin by Simulation and Experiment. Protein Sci. 2005, 14, 1282–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieligmann, K.; Mayr, E.M.; Jaenicke, R. Folding and Self-Assembly of the Domains of betaB2-Crystallin from Rat Eye Lens. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 286, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills-Henry, I.A.; Thol, S.L.; Kosinski-Collins, M.S.; Serebryany, E.; King, J.A. Kinetic Stability of Long-Lived Human Lens γ-Crystallins and Their Isolated Double Greek Key Domains. Biophys. J. 2019, 117, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebryany, E.; King, J.A. The βγ-Crystallins: Native State Stability and Pathways to Aggregation. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2014, 115, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; King, J.A.; Zhou, R. Aggregation of γ-Crystallins Associated with Human Cataracts via Domain Swapping at the C-Terminal β-Strands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 10514–10519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinkl, S.; Glockshuber, R.; Jaenicke, R. Dimerization of Beta B2-Crystallin: The Role of the Linker Peptide and the N- and C-Terminal Extensions. Protein Sci. 1994, 3, 1392–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessio, G. The Evolution of Monomeric and Oligomeric Betagamma-Type Crystallins. Facts and Hypotheses. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 3122–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, B.; Lapatto, R.; Nalini, V.; Driessen, H.; Lindley, P.F.; Mahadevan, D.; Blundell, T.L.; Slingsby, C. X-Ray Analysis of Beta B2-Crystallin and Evolution of Oligomeric Lens Proteins. Nature 1990, 347, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolland, A.D.; Takata, T.; Donor, M.T.; Lampi, K.J.; Prell, J.S. Eye Lens β-Crystallins Are Predicted by Native Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry and Computations to Form Compact Higher-Ordered Heterooligomers. Structure 2023, 31, 1052–1064.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, A.K.; Kroone, R.C.; Lubsen, N.H.; Naylor, C.E.; Jaenicke, R.; Slingsby, C. The C-Terminal Domains of gammaS-Crystallin Pair about a Distorted Twofold Axis. Protein Eng. 1998, 11, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Delaglio, F.; Wyatt, K.; Wistow, G.; Bax, A. Solution Structure of (gamma)S-Crystallin by Molecular Fragment Replacement NMR. Protein Sci. 2005, 14, 3101–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronenborn, A.M. Protein Acrobatics in Pairs--Dimerization via Domain Swapping. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009, 19, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.J.; Schlunegger, M.P.; Eisenberg, D. 3D Domain Swapping: A Mechanism for Oligomer Assembly. Protein Sci. 1995, 4, 2455–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.W.; Verdonk, M.L. The Consequences of Translational and Rotational Entropy Lost by Small Molecules on Binding to Proteins. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2002, 16, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshirsagar, M.; Meller, A.; Humphreys, I.R.; Sledzieski, S.; Xu, Y.; Dodhia, R.; Horvitz, E.; Berger, B.; Bowman, G.R.; Ferres, J.L.; et al. Rapid and Accurate Prediction of Protein Homo-Oligomer Symmetry Using Seq2Symm. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlunegger, M.P.; Bennett, M.J.; Eisenberg, D. Oligomer Formation by 3D Domain Swapping: A Model for Protein Assembly and Misassembly. Adv. Protein Chem. 1997, 50, 61–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, Y. Thermodynamics of Solvation of Ions. Part 5.—Gibbs Free Energy of Hydration at 298.15 K. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1991, 87, 2995–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation in the Thermodynamics of Hydrophobicity. Biophys. Chem. 1994, 51, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Cho, S.S.; Levy, Y.; Cheung, M.S.; Levine, H.; Wolynes, P.G.; Onuchic, J.N. Domain Swapping Is a Consequence of Minimal Frustration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 13786–13791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebryany, E.; Woodard, J.C.; Adkar, B.V.; Shabab, M.; King, J.A.; Shakhnovich, E.I. An Internal Disulfide Locks a Misfolded Aggregation-Prone Intermediate in Cataract-Linked Mutants of Human γD-Crystallin. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 19172–19183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgelin, R.; Jackson, C.J. Entropy, Enthalpy, and Evolution: Adaptive Trade-Offs in Protein Binding Thermodynamics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2025, 94, 103080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roterman, I.; Stapor, K.; Dułak, D.; Konieczny, L. Domain Swapping: A Mathematical Model for Quantitative Assessment of Structural Effects. FEBS Open Bio 2024, 14, 2006–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, F.; Schymkowitz, J.W.H.; Itzhaki, L.S. The Unfolding Story of Three-Dimensional Domain Swapping. Structure 2003, 11, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Manyes, S.; Giganti, D.; Badilla, C.L.; Lezamiz, A.; Perales-Calvo, J.; Beedle, A.E.M.; Fernández, J.M. Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy Predicts a Misfolded, Domain-Swapped Conformation in Human γD-Crystallin Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 4226–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskólski, M. 3D Domain Swapping, Protein Oligomerization, and Amyloid Formation. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2001, 48, 807–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, B.; Nagesh, J.; Reddy, G. Double Domain Swapping in Human γC and γD Crystallin Drives Early Stages of Aggregation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 1705–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, D.; Serebryany, E.; Birrane, G.; Grosas, A.; Kaya, A.; Kraay, C.; Bitran, A.; Carver, J.; Shakhnovich, E. The Thermodynamic Cost of Domain-Swapping in Long-Lived γ-Crystallins and the Evolution of Durable Transparency in the Human Eye Lens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 3269–3269. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Brown, P.H.; Schuck, P. On the Distribution of Protein Refractive Index Increments. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 2309–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wible, R.S.; Sutter, T.R. Soft Cysteine Signaling Network: The Functional Significance of Cysteine in Protein Function and the Soft Acids/bases Thiol Chemistry That Facilitates Cysteine Modification. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2017, 30, 729–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, S.M.; Gladyshev, V.N. Analysis and Functional Prediction of Reactive Cysteine Residues. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 4419–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, M.; Board, S.; Languin-Cattoën, O.; Masino, L.; Stirnemann, G.; Garcia-Manyes, S. A Single-Molecule Strategy to Capture Non-Native Intramolecular and Intermolecular Protein Disulfide Bridges. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 3922–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, S.; Wang, B.; Hom, G.; Guo, M.; Li, B.; Yang, J.; Vaysburg, D.; Monnier, V.M. Evidence of Highly Conserved β-Crystallin Disulfidome That Can Be Mimicked by in Vitro Oxidation in Age-Related Human Cataract and Glutathione Depleted Mouse Lens. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2015, 14, 3211–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebryany, E.; Thorn, D.C.; Quintanar, L. Redox Chemistry of Lens Crystallins: A System of Cysteines. Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 211, 108707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, S.; Fan, X.; Wang, B.; Yang, S.; Monnier, V.M. Reactive Cysteine Residues in the Oxidative Dimerization and Cu2+ Induced Aggregation of Human γD-Crystallin: Implications for Age-Related Cataract. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 3595–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strofaldi, A.; Khan, A.R.; McManus, J.J. Surface Exposed Free Cysteine Suppresses Crystallization of Human γD-Crystallin. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 167252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derewenda, Z.S.; Vekilov, P.G. Entropy and Surface Engineering in Protein Crystallization. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006, 62, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hentschel, L.; Hansen, J.; Egelhaaf, S.U.; Platten, F. The Crystallization Enthalpy and Entropy of Protein Solutions: Microcalorimetry, Van’t Hoff Determination and Linearized Poisson-Boltzmann Model of Tetragonal Lysozyme Crystals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 2686–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, S.R.; Smith, D.L.; Smith, J.B. Deamidation and Disulfide Bonding in Human Lens Gamma-Crystallins. Exp. Eye Res. 1998, 67, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.M.; Nye-Wood, M.G.; Rose, K.L.; Donaldson, P.J.; Grey, A.C.; Schey, K.L. MALDI Imaging Mass Spectrometry of β- and γ-Crystallins in the Ocular Lens. J. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 55, e4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkiss, A.G.; Bateman, O.A.; Goodfellow, J.M.; Lubsen, N.H.; Slingsby, C. The X-Ray Crystal Structure of Human Gamma S-Crystallin C-Terminal Domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 4199–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, D.C.; Serebryany, E.; Birrane, G.; Kaya, A.I.; Shakhnovich, E.I. Domain-Swapped Dimeric γ-Crystallin: The Missing Link in the Evolution of Oligomeric β-Crystallins. FASEB J. 2022, 36 Suppl. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lomakin, A.; McManus, J.J.; Ogun, O.; Benedek, G.B. Phase Behavior of Mixtures of Human Lens Proteins Gamma D and Beta B1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 13282–13287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, G.; d’Amico, D.; Gerday, C. Thermodynamic Stability of a Cold-Active Alpha-Amylase from the Antarctic Bacterium Alteromonas Haloplanctis. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 4613–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arribas, O.; Mateo, R.; Tomczak, M.M.; Davies, P.L.; Mateu, M.G. Thermodynamic Stability of a Cold-Adapted Protein, Type III Antifreeze Protein, and Energetic Contribution of Salt Bridges. Protein Sci. 2007, 16, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, W.D.; Freites, J.A.; Golchert, K.J.; Shapiro, R.A.; Morikis, V.; Tobias, D.J.; Martin, R.W. Separating Instability from Aggregation Propensity in γS-Crystallin Variants. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Zhou, H.-X. Atomistic Modeling of Liquid-Liquid Phase Equilibrium Explains Dependence of Critical Temperature on γ-Crystallin Sequence. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.A.; Sprague-Piercy, M.A.; Kwok, A.O.; Roskamp, K.W.; Martin, R.W. Chemical Properties Determine Solubility and Stability in βγ-Crystallins of the Eye Lens. Chembiochem 2021, 22, 1329–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.J.; Pinto, J.T.; Callery, P.S. Reversible and Irreversible Protein Glutathionylation: Biological and Clinical Aspects. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2011, 7, 891–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremers, C.M.; Jakob, U. Oxidant Sensing by Reversible Disulfide Bond Formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 26489–26496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, S.F. Disulfide Bonds and the Stability of Globular Proteins. Protein Sci. 1993, 2, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Uys, J.D.; Tew, K.D.; Townsend, D.M. S-Glutathionylation: From Molecular Mechanisms to Health Outcomes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 233–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushchak, V.I. Glutathione Homeostasis and Functions: Potential Targets for Medical Interventions. J. Amino Acids 2012, 2012, 736837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaogullari, A.; Chai, Y.-C. Redox Regulation by Protein S-Glutathionylation: From Molecular Mechanisms to Implications in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinina, E.; Novichkova, M. Glutathione in Protein Redox Modulation through S-Glutathionylation and S-Nitrosylation. Molecules 2021, 26, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.N.; Pelletier, M.R. Destabilization of Lens Protein Conformation by Glutathione Mixed Disulfide. Exp. Eye Res. 1988, 47, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle-Donne, I.; Rossi, R.; Colombo, G.; Giustarini, D.; Milzani, A. Protein S-Glutathionylation: A Regulatory Device from Bacteria to Humans. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009, 34, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampi, K.J.; Thorn, D.; Halverson-Kolkind, K.; David, L. Mechanism of Glutathionylation-Induced Heat Precipitation of γS-Crystallin. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 1277–1277. [Google Scholar]

- Thorn, D.C.; Grosas, A.B.; Mabbitt, P.D.; Ray, N.J.; Jackson, C.J.; Carver, J.A. The Structure and Stability of the Disulfide-Linked γS-Crystallin Dimer Provide Insight into Oxidation Products Associated with Lens Cataract Formation. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, J.J. Free and Protein-Bound Glutathione in Normal and Cataractous Human Lenses. Biochem. J. 1970, 117, 957–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craghill, J.; Cronshaw, A.D.; Harding, J.J. The Identification of a Reaction Site of Glutathione Mixed-Disulphide Formation on gammaS-Crystallin in Human Lens. Biochem. J. 2004, 379, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khago, D.; Wong, E.K.; Kingsley, C.N.; Freites, J.A.; Tobias, D.J.; Martin, R.W. Increased Hydrophobic Surface Exposure in the Cataract-Related G18V Variant of Human γS-Crystallin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1860, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampi, K.; Kraay, C.; Halverson-Kolkind, K.; Thorn, D.; Shakhnovich, E.; David, L. BPS2025—Pursuit of the Elusive Disulfide Crosslink in Oxidized γS-Crystallin from the Eye Lens. Biophys. J. 2025, 124, 213a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Schey, K.L. Quantification of Thioether-Linked Glutathione Modifications in Human Lens Proteins. Exp. Eye Res. 2018, 175, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, D.M.; Lushchak, V.I.; Cooper, A.J.L. A Comparison of Reversible versus Irreversible Protein Glutathionylation. Adv. Cancer Res. 2014, 122, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.T.; Chiba, Y.; Arai, H.; Ishii, M. Discovery of an Intermolecular Disulfide Bond Required for the Thermostability of a Heterodimeric Protein from the Thermophile Hydrogenobacter Thermophilus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016, 80, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troussicot, L.; Vallet, A.; Molin, M.; Burmann, B.M.; Schanda, P. Disulfide-Bond-Induced Structural Frustration and Dynamic Disorder in a Peroxiredoxin from MAS NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 10700–10711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankowicz, S.A.; Fraser, J.S. Advances in Uncovering the Mechanisms of Macromolecular Conformational Entropy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2025, 21, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.W.; Mittag, T. Relationship of Sequence and Phase Separation in Protein Low-Complexity Regions. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 2478–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.S.; Levy, Y.; Onuchic, J.N.; Wolynes, P.G. Overcoming Residual Frustration in Domain-Swapping: The Roles of Disulfide Bonds in Dimerization and Aggregation. Phys. Biol. 2005, 2, S44–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Schafer, N.P.; Wolynes, P.G. Frustration in the Energy Landscapes of Multidomain Protein Misfolding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 1680–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, M.F. Glutathione and Glutaredoxin in Redox Regulation and Cell Signaling of the Lens. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebryany, E.; King, J.A. Wild-Type Human γD-Crystallin Promotes Aggregation of Its Oxidation-Mimicking, Misfolding-Prone W42Q Mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 11491–11503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, D.; Serebryany, E.; David, L.L.; Lampi, K.J.; Shakhnovich, E. Playing “redox Hot Potato”: Disulfide Transfer between γ-Crystallins in the Aging, Pre-Cataractous Lens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 1230–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Adav, S.S. Advances in the Study of Protein Deamidation: Unveiling Its Influence on Aging, Disease Progression, Forensics and Therapeutic Efficacy. Proteomes 2025, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapko, V.N.; Purkiss, A.G.; Smith, D.L.; Smith, J.B. Deamidation in Human Gamma S-Crystallin from Cataractous Lenses Is Influenced by Surface Exposure. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 8638–8648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseman, A.J.; Whitley, M.J.; González, J.J.; Rathi, N.; Ambarian, M.; Gronenborn, A.M. Assessing the Structures and Interactions of γD-Crystallin Deamidation Variants. Structure 2021, 29, 284–291.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.; Nakayoshi, T.; Kitamura, Y.; Kurimoto, E.; Oda, A.; Ishikawa, Y. Identification of the Most Impactful Asparagine Residues for γS-Crystallin Aggregation by Deamidation. Biochemistry 2023, 62, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, N.J.; Hall, D.; Carver, J.A. Deamidation of N76 in Human γS-Crystallin Promotes Dimer Formation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1860, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pande, A.; Mokhor, N.; Pande, J. Deamidation of Human γS-Crystallin Increases Attractive Protein Interactions: Implications for Cataract. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 4890–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetter, C.J.; Thorn, D.C.; Wheeler, S.G.; Mundorff, C.C.; Halverson, K.A.; Wales, T.E.; Shinde, U.P.; Engen, J.R.; David, L.L.; Carver, J.A.; et al. Cumulative Deamidations of the Major Lens Protein γS-Crystallin Increase Its Aggregation during Unfolding and Oxidation. Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 1945–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, H.M.; Vetter, C.J.; Jara, K.A.; Reardon, P.N.; David, L.L.; Barbar, E.J.; Lampi, K.J. Altered Protein Dynamics and Increased Aggregation of Human γS-Crystallin due to Cataract-Associated Deamidations. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 4112–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampi, K.J.; Wilmarth, P.A.; Murray, M.R.; David, L.L. Lens β-Crystallins: The Role of Deamidation and Related Modifications in Aging and Cataract. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2014, 115, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiel, M.; Duprat, E.; Skouri-Panet, F.; Lampi, J.A.; Tardieu, A.; Lampi, K.J.; Finet, S. Aggregation of Deamidated Human betaB2-Crystallin and Incomplete Rescue by Alpha-Crystallin Chaperone. Exp. Eye Res. 2010, 90, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, T.; Oxford, J.T.; Demeler, B.; Lampi, K.J. Deamidation Destabilizes and Triggers Aggregation of a Lens Protein, betaA3-Crystallin. Protein Sci. 2008, 17, 1565–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampi, K.J.; Amyx, K.K.; Ahmann, P.; Steel, E.A. Deamidation in Human Lens betaB2-Crystallin Destabilizes the Dimer. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 3146–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampi, K.J.; Fox, C.B.; David, L.L. Changes in Solvent Accessibility of Wild-Type and Deamidated βB2-Crystallin Following Complex Formation with αA-Crystallin. Exp. Eye Res. 2012, 104, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budnar, P.; Tangirala, R.; Bakthisaran, R.; Rao, C.M. Protein Aggregation and Cataract: Role of Age-Related Modifications and Mutations in α-Crystallins. Biochemistry 2022, 87, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, T.; Oxford, J.T.; Brandon, T.R.; Lampi, K.J. Deamidation Alters the Structure and Decreases the Stability of Human Lens betaA3-Crystallin. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 8861–8871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaugh, S.L.; Mills, I.A.; King, J. Glutamine Deamidation Destabilizes Human gammaD-Crystallin and Lowers the Kinetic Barrier to Unfolding. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 30782–30793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampi, K.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Bächinger, H.P.; Boswell, B.A.; Lindner, R.A.; Carver, J.A.; Shearer, T.R.; David, L.L.; Kapfer, D.M. Decreased Heat Stability and Increased Chaperone Requirement of Modified Human betaB1-Crystallins. Mol. Vis. 2002, 8, 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Strub, C.; Alies, C.; Lougarre, A.; Ladurantie, C.; Czaplicki, J.; Fournier, D. Mutation of Exposed Hydrophobic Amino Acids to Arginine to Increase Protein Stability. BMC Biochem. 2004, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antifeeva, I.A.; Fonin, A.V.; Fefilova, A.S.; Stepanenko, O.V.; Povarova, O.I.; Silonov, S.A.; Kuznetsova, I.M.; Uversky, V.N.; Turoverov, K.K. Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation as an Organizing Principle of Intracellular Space: Overview of the Evolution of the Cell Compartmentalization Concept. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, C. The Hydrophobic Effect and the Organization of Living Matter. Science 1978, 200, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gils, J.H.M.; Gogishvili, D.; van Eck, J.; Bouwmeester, R.; van Dijk, E.; Abeln, S. How Sticky Are Our Proteins? Quantifying Hydrophobicity of the Human Proteome. Bioinform. Adv. 2022, 2, vbac002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalakshmi, R. Aromatic Interactions in β-Hairpin Scaffold Stability: A Historical Perspective. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 661, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sancho, D.; López, X. Crossover in Aromatic Amino Acid Interaction Strength: Tyrosine vs. Phenylalanine in Biomolecular Condensates. Phenylalanine in Biomolecular Condensates. eLife 2025.

- De Sancho, D. Phase Separation in Amino Acid Mixtures Is Governed by Composition. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 4119–4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendruscolo, M.; Fuxreiter, M. Towards Sequence-Based Principles for Protein Phase Separation Predictions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023, 75, 102317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Srivastava, O.P. Deamidation Affects Structural and Functional Properties of Human alphaA-Crystallin and Its Oligomerization with alphaB-Crystallin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 44258–44269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.P.; Petrash, J.M.; Surewicz, W.K. Conformational Properties of Substrate Proteins Bound to a Molecular Chaperone Alpha-Crystallin. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 10449–10452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougherty, D.A. Cation-Pi Interactions Involving Aromatic Amino Acids. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1504S–1508S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasakthi, V.; Anitha, P.; Kumar, K.M.; Bag, S.; Senthilvel, P.; Lavanya, P.; Swetha, R.; Anbarasu, A.; Ramaiah, S. Aromatic-Aromatic Interactions: Analysis of π-π Interactions in Interleukins and TNF Proteins. Bioinformation 2013, 9, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S.E. Understanding Substituent Effects in Noncovalent Interactions Involving Aromatic Rings. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calinsky, R.; Levy, Y. Aromatic Residues in Proteins: Re-Evaluating the Geometry and Energetics of π-π, Cation-π, and CH-π Interactions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 8687–8700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter-Fenk, K.; Liu, M.; Pujal, L.; Loipersberger, M.; Tsanai, M.; Vernon, R.M.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; Head-Gordon, M.; Heidar-Zadeh, F.; Head-Gordon, T. The Energetic Origins of Pi-Pi Contacts in Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]