1. Introduction

The development of chronic degenerative diseases (CDD) is often accompanied by significant metabolic disruptions, frequently exacerbated by high-calorie diets and sedentary lifestyles [

1]. Excessive caloric intake leads to hyperglycemia, contributing to Metabolic Syndrome, which is increasingly observed in younger populations [

2].

Mounting evidence highlights the interplay between energy metabolism and proteostasis, suggesting that this relationship plays a crucial role in CDD progression. Metabolic disturbances in glycolysis and proteolysis can create a detrimental self-reinforcing cycle that induces the production and accumulation of the trioses dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P). This results in elevated levels of methylglyoxal (MGO), identified to be a toxic byproduct derived from the degradation of such trioses [

3]. MGO induces non-enzymatic post-translational modifications (NE/PTM), which can compromise protein stability and lead to misfolding, as previously reported in TPI from

Drosophila [

4].

At low doses (0.3 mM), MGO can form adducts with 5-10% of the cellular protein content [

5]. These adducts primarily involve arginine (Arg) residues, creating hydroimidazolones adducts (MGO-H). MGO-H1 and MGO-H2 are the predominant form, accounting for over 90% of MGO-derived adducts [

6]. MGO can also modify lysine (Lys) residues, generating free radicals like superoxide [

7], which increase intracellular oxidative stress within cells [

8]. Due to its electrophilic nature and reactivity, MGO binds reversibly to nucleophiles such as thiols, especially glutathione (GSH), as well as to cysteine (Cys) residues in proteins forming hemithioacetals [

9]. MGO detoxification occurs via both GSH-independent and GSH-dependent pathways [

10]. Nonetheless, in pathological states such as cancer and metabolic syndrome, where glycolytic activity is significantly upregulated (30 to 200-fold respect normal cells), it has been observed that elevated levels of MGO may paradoxically exert a hormetic or dual adaptive effect, promoting cell proliferation [

11].

In both normal and pathological conditions, as observed in individuals with CDD [

1], these NE/PTMs can induce novel protein functions, excluding their canonical roles through the generation of moonlighting activities. This phenomenon underscores the importance of understanding how NE/PTMs, driven by pathological signals or genetic mutations, underlie disease mechanisms [

12]. MGO can accelerate premature aging and contribute to a plethora of chronic degenerative diseases, including arterial hypertension, atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, cancer [

13], Parkinson's disease [

14], and Alzheimer's disease (AD) [

15]. These diseases are characterized by the accumulation of proteins with altered metabolic functions due to NE/PTMs, such as albumin [

16,

17], hemoglobin

[18], HSP-27 [

19], G3-PDH [

20], α-synuclein [

21] and TPI [

22].

A study on HEK cells overexpressing a double mutant of TPI (Tyr164-Phe and Tyr208-Phe) demonstrated that its nitrotyrosination decreased glycolytic flux due to diminished catalytic activity and elevated MGO production [

23]. This effect correlated with higher glycation levels in AD brains and β-sheet aggregate formation in vitro and transgenic mice. The nitro-oxidative environment in AD promotes high levels of 3-nitrotyrosinated TPI, leading to the inhibition of this enzyme, with subsequent increases of MGO levels [

23], ultimately contributing to the advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) formation [

24].

Glycolytic failure in CDD leads to harmful adduct accumulation and dicarbonyl stress, promoting AGE formation [

25]. It has been shown that AGEs, with diverse chemical structures, could be associated with different pathologies, hence, in part, the difficulty in quantifying them

[26]. Additionally, these AGEs slowly but irreversibly modify Lys and Arg residues [

27], making it possible to classify into non-fluorescent types (e.g., N-ε-(carboxyethyl)lysine [CEL]), carboxymethyl-lysine [CML]) and fluorescent types (e.g., pentosidine, MGO-lysine dimer [MOLD], and ARGp) [

28].

The role of TPI is critical in preventing DHAP accumulation (precursor of MGO and AGEs) [

29]. This study focuses on the functional and structural changes induced by single mutants of human TPI (HsTPI), particularly the E104D and C217K mutants, linked to regulatory effects on enzyme activity. Unlike the deamidated N16D variant [

30], N16D does not exhibit substrate saturation, leading to increased MGO production and ARGp adduct formation. Exposure to G3P or MGO induces structural and functional alterations in these HsTPI mutants, highlighting their susceptibility to MGO and increased ARGp adducts. These changes negatively impact structural stability, accelerating enzymatic inhibition and unfolding. Thus, our results elucidate the impact of some HsTPI mutations on function and structure, providing insights into the severity of HsTPI deficiency, which can be reversed by adding MGO scavenger molecules [

31].

3. Discussion

Glycolytic enzymes have been reported to be targets of NE/PTM through the formation of MGO adducts. The MGO adducts are modified by carbamylation at TPI Arg3 and oxidation at Met14 in samples obtained from epithelial cell lines and peripheral blood lymphocytes [

34]. Moreover, TPI and glycosylated haemoglobin in mice have been reported to be markers of diabetes [

35].

This study delves into how mutations in HsTPI can significantly impact its kinetic stability and protein structure by fostering MGO adduct formation and enzymatic aggregation. Anomalous folding leading to enzyme instability is a known contributor to toxic protein aggregate formation in HsTPI variants associated with pathology [

36]. Our investigation compares wild-type HsTPI against mutants resembling C217K, E104D, and the inherently unstable N16D. This comparison elucidates the effects of mutations on intra- or intersubunit contacts, unfolding, and aggregation in HsTPI [

37], similar to observations in other proteins like albumin [

38].

In a murine AD model, TPI glycation has been detected in the brains of transgenic mice exhibiting β-amyloid plaque formation [

35]. We demonstrate that metabolite-induced inhibition and unfolding, under normal or pathological conditions, manifest in changes such as catalytic instability, enzymatic loss, inhibition, structural unfolding, and increased resistance to proteolysis. We observe a negative synergy between the catalytic activity of mutant enzymes, where kinetic instability precedes protein inactivation. The loss of substrate affinity in C217K promotes substrate transformation to MGO. This compensatory effect decreases affinity by substrate, accelerating G3P isomerization and potentially initiating MGO adduct formation and structural instability.

These alterations were previously shown in N16D to drastically decrease cellular activity and increase MGO in breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) [

39]. Thus, metabolic reprogramming can occur due to increased aerobic glycolysis [

40]. This enzyme represented the behaviour of HsTPI in glycolytic cancer cells. It was evidenced by a more significant number of internal cavities that made it more porous and reactive to inhibitory compounds [

41], therefore showing increased susceptibility to AGE formation, ranking first in ARGp adduct formation, which in five days under intracellular physiological concentrations reported for MGO, enzymatically inhibits and destabilises the mutant proteins analyzed.

The Cys217 residue in α-helix 7 of HsTPI is pivotal in regulating enzyme catalysis and stability [

42]. Mutations disrupting interactions involving Cys217 may directly lead to MGO generation, as seen in C217K, facilitating the acquisition of NE/PTM in HsTPI [

43]. This mutant C217K shows similarity in the accessibility of its free Cys to WT, showing a marginal initial effect on structural stability and enzymatic catalysis. However, this same substitution by directed mutagenesis in Giardia lamblia TPI (GlTPI-C222K) was reported to drastically affect catalysis by introducing a positive charge, with decreased k

cat/K

m < 159-fold vs GlTPI-WT.

Due to the mutation for GlTPI-C222K, It has been reported that the differences in reactivity of Cys217 in HsTPI compared to homologue Cys222 in GlTPI are due to the surrounding environment of these Cys residues [

42]. Still, in HsTPI-C217K, this mutant resembled initially like-WT performance by their catalytic efficiency [

44].

These are consistent with the change in catalytic constants in both GlTPI and HsTPI enzymes, and active site perturbations are associated with alterations in the regions 212–219 and 231–234 in the case of the deficiency mutant HsTPI-V231M located very close to the active site [

45].

The HsTPI-E104D mutant, associated with a human TPI deficiency disease, exhibits normal catalytic activity but diminished 1-fold substrate affinity. Structural alterations in this mutant compromise dimer formation and thermostability, leading to monomerisation under conditions where the wild-type enzyme remains dimeric [

46].

Mutant enzymes C217K and E104D show increased structural alterations, commonly linked to conformational changes induced and amplified by enzymatic activity and subsequent misfolding, resulting in MGO adduct formation. Despite no initial reduction in catalytic activity, similar to pathogenic TPI variants, these mutants exhibit decreased activity, highlighting the need for further investigation into cellular processes contributing to TPI deficiency [

47].

It has been reported that MGO promotes cell damage by increasing ARGp. As this adduct is formed, one month of diabetes in a model animal may be sufficient to produce ARGp [

48]. We show that WT enzyme plus-MGO evidenced structure compaction, but the mutants showed susceptibility to MGO permeability and ARGp adduct formation.

On the other hand, we describe a new approach to exploring the deficiencies of HsTPI or point mutations located at regulatory sites of TPI activity, such as Cys217, that provoked structural instability. Thus, the C217K mutant's behaviour may help unravel the mechanism by which the loss of contacts close to the mutation site can differentially impact the development of functional instability, causing the initial decrease in substrate affinity that induces drastic structural changes observed by biophysical structural probes which confirmed its propensity for denaturation.

An important point is the rate of change of the secondary structure components in the mutant by substrate catalysis. In this sense, the mutant recombinant F240L reported for the human deficiency showed a 6-fold higher activity in purified E. coli extracts than the erythrocytes from patients with the mutation [

47]; thus, in the context of molecular turnover due to catalysis, our data agree that enzymatic catalysis in the mutants enzymes differentially alters their stability making them more susceptible to enzymatic inactivation and structural unfolding.

The rate at which mutants unfolded was much faster and accelerated. In the case of the F240L mutant, the loss of its activity may be related to the number of catalytic events that the enzyme can withstand in the patients due to the mutation, thus showing in patients the presence of enzymes worn out by catalysis and whose activity is lower [

49], as in our explored conditions plus G3P. This behaviour has not yet been investigated in the recombinant mutant enzymes reported for deficiency, but we show that it quickly showed enzymatic inhibition and no derivatization by DTNB plus-G3P.

The restitution of its structural integrity was observed in the mutant enzymes since at that concentration of substrate plus the Arg scavenger; the MGO did not penetrate the nucleus of the enzyme, did not promote the destabilisation of the active site and inhibited the generation of the ARGp adduct, or interaction with Cys and Lys residues to the core of the molecule, since the presence of protein cavities is related to flexibility and stability. The diffusion of small ligands through globular proteins is a global phenomenon, previously noted by [

50], also evidenced in these mutant enzymes.

In this sense, the diffusion of molecules into the crystallographic structure of deamidated HsTPI was more significant [

41]. It has been reported that hemi-phosphorylation of HsTPI on Ser20 in one of its subunits allows the formation of a channel that transports the substrate to the active site and functions as a switch, which enhances its catalysis, indicating that heterodimerization and subunit asymmetry are key features so that phosphorylation of Ser20 on HsTPI optionally potentialise its catalysis [

51]. However, they have not proved their kinetic stability and structural changes induced by substrate, and they could show the same susceptibility for AGE formation in mutants described for human enzymatic deficiency. Therefore, we can expect that any TPI mutant, due to loss of stability and inclusion of MGO, can observe these changes vs the WT enzyme under the same conditions.

One of the most exciting questions is the reason for the proteic accumulation of deamidated HsTPI in breast cancer cells, as evidenced in [

39], since greater proteolytic susceptibility was previously demonstrated in vitro in the recombinant deamidated enzyme [

30], and one of the answers to its accumulation, maybe this NE/PTM exerted by MGO over Cys and Lys residues. Because N16D is less active, more porous, and with a greater volume of internal cavities, this facilitates the access of dicarbonyl adducts that interfere in their proteolytic turnover by the proteasome. A similar case was evidenced in the glycation of G6PDH, whose resistance to proteolysis was correlated with increased conformational stability promoted by adducts that were more resistant to proteolytic degradation (also observed in C217K mutant exposed to MGO,

Figure S5) in glyoxal-treated fibroblast culture [

52] as well as by the formation of adducts of Cys-MGO as a reversible hemithioacetal and stable mercapto-methylimidazole to its glycated enzyme [

53].

In these mutants that initially showed WT-like enzyme activity, such as their instability causes a loss of catalysis and delayed cellular enzyme turnover, as well as generalised damage by substrate accumulation and transformation by MGO adduct formation that is increased by TPI enzymatic deficiency by core inclusion of AGEs. These covalent AGE modifications result in functional impairment and the formation of toxic protein inclusions [

54], which are probably related to new moonlighting activities, as reported by [

49], and the development of pathologic functions. This condition constitutes and leads to the development of CDD by the accumulation of MGO adducts that indirectly modify and significantly alter the intracellular redox system.

We understand the mechanism of the dynamic processes associated with the inactivation and turnover of TPI, which promote the reduction or loss of molecular function. We showed the role that specific TPI point mutations could play in developing chronic degenerative disease. This behaviour derived from the inefficient isomerization of substrates, accumulation, and increase of MGO by inhibition of isomerase activity or, finally, the acquisition of methylglyoxal synthase activity how, has been previously proposed in yeast TPI enzyme where a cut in the active site loop 6 converts the enzyme into a better methylglyoxal synthase [

55].

It has been proposed that the best predictor of severity in TPI deficiency in various point mutations is caused by alterations that affect its structural conformation and folding without considering the role of catalytic ageing of this enzyme. However, this study provides elements that show distinctive signatures that should be considered when studying mutations related to this enzymatic deficiency. It displays catalysis-induced structural changes that differentially wear down the mutant enzymes over time.

Previous studies involved in the restitution of activity of TPI identified two compounds, resveratrol and itavastatin, that increase the levels of mutant TPI-E104D protein in a human cellular TPI model of deficiency and TPI deficiency patient cells. These compounds have properties as candidates for repurposing [

56]. An increase in protein levels in a TPI deficiency TPIQ181P/E105D suggests that it could benefit not only patients with the common mutation but compound heterozygous patients [

31], and resveratrol would represent an almost immediately applicable treatment for current TPI deficiency patients.

Although it is clear that NE/PTM is one of the likely mechanisms underlying the structural alteration of HsTIPI, glycation promotes misfolding, unfolding, inactivation, aggregation, and low proteic rechange. In this case, proteins containing reactive cysteines (prone to forming a thiolate anion at cellular pH) are vulnerable to alterations in the redox balance caused by ROS from alterations in nutritional status [

59]. These PTMs can form aggregates due to excessive or chronic consumption of high-calorie foods that accumulate and transform in a proteotoxic cellular environment.

In the future, we intend to explore the determination of specific HsTPI residues involved in PTM development and aggregate formation using mass spectrometry. We foresee the need to enrich this study with other techniques for studying each human deficiency mutant. We propose the use of small-molecule supplements that enzymatically rescue and correct protein folding defects, which can act as scavengers of glycation by MGO and pharmacological chaperones that may reverse TPI deficiency in humans and too for the prevention and general treatment of people with chronic and degenerative diseases.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Expression and Purification

Expression and purification of recombinant enzymes were performed as previously reported [

30].

4.2. Protein Concentration

Protein quantification in each purification step was performed using the bicinchoninic acid method, with bovine serum albumin (BSA) (BSA, Fraction V, EUROClone Ltd. U.K.; Cat.No. EMR086050) as standard. Protein concentrations of WT enzyme and its single mutants C217K, N16D, and E104D, was calculated using ε280 nm = 32595 M-1 ∙ cm-1, and for proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich, CatNo. P2308-100MG) ε280 nm = 33380 M-1 ∙ cm-1.

4.3. Enzymatic Activity

From recombinant HsTPI-WT and mutant C217K, N16D and E104D enzymes with ≥95 % purity. The enzyme activity was determined by a coupled system involving the disappearance of NADH (MERCK, CatNo. N1161) at 340 nm [

30]. The readings were carried out in a Cary 50 spectrophotometer (Varian, Cary 50) with 5, 3.3, 5, and 60 ng/mL of WT, C217K, E104D and -N16D enzymes, respectively.

4.3.1. Kinetic Constants of the Enzymes

For WT and the C217K mutant, Vmax and Km were obtained by fitting the initial velocity data (G3P concentrations from 0.02 to 4 mM) to the Michaelis-Menten equation (Vi = Vmax[S]/Km+[S]) for non-linear-regression-calculations. The data could not be fitted for the N16D mutant with no saturation at the highest substrate concentrations, and Vmax and Km values were not calculated. For -WT and -C217K, kcat values were derived from Vmax considering a monomer MM of 26682.43 Da. For the N16D mutant, kcat/Km ratios were obtained from the slope of the double reciprocal plots according to kcat/Km=1/m∙[enzyme] (where m represents Km/Vmax) and by the use of the previously indicated MM.

4.4. Native Electrophoresis (N-PAGE)

A method to estimate the structural stability of proteins is by preparing native gels that allow us to recognize through native electrophoresis (N-PAGE) the integrity of the quaternary structure of the protein, as well as the homogeneity between the mass-to-charge ratio present with respect to control. Its N-PAGE were carried out with Tris-Glycine pH 8.5 buffer. The running conditions of the samples containing 5-10 ug of proteins were 3 h at a constant 7 mAmp and subsequently stained with Coomassie Brillant Blue G [

30].

4.5. Titration of Free Cysteines

It was carried out with ’Ellman's reagent; briefly, TPI enzymes (330 μg/mL) were added to the quartz cuvette in 100 mM Triethanolamine (TE) buffer (SIGMA Cat. .No.T1502-500G) at pH 7.4 at 25 °C; after addition of 4 mM of cysteine-derivatizing reagent 5,5′-Dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic) acid (DTNB) (SIGMA, Cat No. D8130-5G) ε=13,600 M

-1∙cm

-1 at 412 nm and pH 8.0, Cys modification was determined by recording ΔAbs at 412 nm for each enzyme [

58].

4.5.1. Susceptibility to Cysteine Derivatising Reagent after Substrate Incubation

Protein samples at 200 μg of protein were incubated for 54 h at 37 °C in TE buffer at pH 7.4 plus-G3P 1 mM in a recirculating bath (LAUDA, Brinkman Ecoline RE106). At the end of the incubations, the protein samples were derivatized with DTNB 4 mM. Therefore, the samples in 600 μL were exposed to 4 mM DTNB, and then readings of the ΔAbs at 412 nm due to TNB formation were recorded for 40 min. SDS 20% was added to denature the protein and expose the non-accessible Cys residues to the derivatising reagent. Readings were recorded at 25 °C in a Cary 50 spectrophotometer. The Abs at 412 nm of the blank containing only 4 mM DTNB was subtracted from each sample to obtain the net increase in Abs.

4.6. Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy (CD)

4.6.1. CD Far Ultra-Violet (CD-UV Far)

The CD spectra were analyzed to show changes in the secondary structure of the enzymes. Samples at 1 mg/mL of control and plus-G3P 1 mM were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Protein samples were pre-dialyzed in 25 mM NaH

2PO

4 buffer at pH 7.4 diluted to 0.1 mg/mL and analyzed using a 0.1 cm quartz cuvette at 25 °C. CD spectra were acquired using a JASCO J-810 spectropolarimeter (Jasco Inc., Easton, MD, USA). Spectra were recorded over the spectral range 260 − 190 nm, with data pitch 0.1 nm, continuous analysis mode, speed 20 nm/min., response 2 sec., bandwidth resolution of 1 nm, and accumulation of 3 samples to obtain CD spectra. The signal of CD spectra of the buffer was subtracted from each sample spectrum. The results were expressed as molar ellipticity (θ), which is defined as:

where the observed degrees (θobs) is the average ellipticity of the residues observed in degrees, (c) is the protein concentration in mg/mL, (MRW) is the average relative mass of the aminoacyl residues (106.72972 Da), and (l) is the path length expressed in cm. The CD spectra obtained were the averages of five scans. The spectra were smoothed through an internal algorithm in the Jasco software package, J-810 for Windows.

The online software BeStSel was used to estimate the content of secondary structure by deconvolution of the spectra obtained by the CD of each enzyme in the far UV (Beta Structure Selection) was carried out [

59].

4.6.2. Thermal Stability

For the evaluation of protein thermal stability, protein unfolding was followed as the change in CD signal at 222 nm in a scan from 25 to 90 °C following the temperature increase of 24 °C/h. The unfolded protein fraction and mean denaturation temperature (T

m) values were calculated by recording its molar ellipticity at 222 nm. HsTPI at 100 μg/mL was previously dialysed for the experiments against NaH

2PO

4 25 mM buffer. From the data obtained, the apparent fraction of denatured subunits (FD) was calculated using the Boltzmann equation:

where: yN and yD are ellipticity values of the native and unfolded fractions, respectively. Both parameters were linear extrapolations of the initial and terminal portions of the curve as a function of increasing temperature.

4.7. Intrinsic Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Protein controls HsTPI-WT, C217K, and N16D at 1 mg/mL were previously dialysed in 100 mM TE buffer at pH 7.4 and incubated in a time course from 0, 2, 28, 48, 72, and 96 h at 37 °C, without G3P or MGO. Aliquots were removed each time, and the readings were analyzed at Dil. 1:20 in buffer TE. Each fluorescence intensity reading was obtained on a Perkin-Elmer LS-50 spectrofluorometer in a quartz cuvette with a 1:20 diluted sample (protein at 0.05 mg/mL) in 700 μL. The fluorescence signal of the buffer was subtracted from the protein spectra. Measurements were based on a triplicate of three individual protein preparations. Scans were recorded from 310-500 nm and λ exc. at 280 and 295 nm to obtain emission spectra. The conditions were using exc. and em. slits of 3.5 and scan speed 100 nm∙min−1.

The initial analysis of intrinsic fluorescence (IF) allowed us to determine the changes in maximum fluorescence intensity expressed in arbitrary units (IFmax, a.u.) of each sample of enzyme control. The wavelength emission (λ em.) of IFmax in nm (λ max) was calculated by selecting the point that exhibited the highest FI expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.), as well as spectral centre of masses (SCM) wavelength was calculated according to [

60], where (λ) is the wavelength used, (I) are the intensities obtained at each wavelength. In the same form as controls, readings (0 and until 96 h) were performed that allowed the kinetic demonstration of the structural changes induced by both compounds over HsTPI-WT, C217K, and N16D enzymes exposed to G3P or MGO. The results of the fluorescence spectra were plotted (PC Software, Origin Professional).

4.7.1. Analysis of the Protein Formation of the Fluorescent Adduct of ARGp

4.7.1.1. Control Curves of the ARGp Adduct Formation

Based on the method reported by Shipanova et al. [

61], control curves of ARGp formation were performed with Arg-MGO as a reference to ARGp formation (ARG-MGO; SIGMA, Cat. A5006-100G and M0252-25ML, respectively) or Arg-G3P (Arg-G3P; SIGMA, Cat. G5376-1G)—samples in an equimolar concentration of 20 mM of each reactant. Sample reads at Dil. 1:20 (G3P or MGO, 1 mM). The same form, C217K protein samples at 1 mg/mL dialysed vs TE buffer at pH 7.4, was incubated at 0 - 500 h at 37 °C with G3P or MGO at 20 mM.

4.7.2. Alterations of the Three-Dimensional Structure G3P or MGO Induced and Evidenced by Intrinsic Fluorescence

The same form as FI of controls was the determination of the structural effect exerted in time over enzymes incubated plus-G3P 2 mM or plus-MGO 1.

4.7.2.1. Kinetic of ARGp Fluorescent Adduct Formation in WT and Mutant Enzymes

Protein samples HsTPI-WT, and C217K and N16D mutants were G3P or MGO treated as in (6 point method above described), but incubated with 2 mM G3P or 1 mM MGO (2, 28, 48, 72 and 96 h) at 37 °C, and then analyzed by λ exc. at 325 nm to obtain λ em. scans at 340-600 nm. The IFmax ARGp λ em. at 395 nm evidenced the formation and increase in time of the fluorescent adduct of ARGp in the enzymes, and the concomitant loss of IFmax and shift of SCM in time course was observed in the treated samples vs their controls. Thus, the formation of ARGp was associated, as previously described [

62], with the unfolding and alteration of the protein structure.

4.7.2.2. Extrinsic Fluorescence Assays

To determine the extrinsic fluorescence (EF) by hydrophobic patches exposed to the protein surface was evidenced with 8-Anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonic acid (ANSA) (SIGMA, Cat. No. A1028-100G) in the protein samples exposed at 2 mM G3P or 1 mM MGO (The samples were treated as point six described above). Only that, this was recorded at λ em. 400 to 600 nm with λ exc. 395 nm; the final concentrations of ANSA and HsTPI were 150 μM and 327 μg/mL, respectively, as previously reported [

32], and from the λ em., the fluorescence signal at 485 nm was taken to plot the binding of ANSA to the protein over time.

4.8. Effect of Physiological Concentrations of MGO or G3P on HsTPI-WT Enzymes and the C217K and E104D Mutant

Experiments were performed with 15 μg enzyme samples incubated at 1 mg/mL with different concentrations of MGO or G3P, from 0, 10, 50,100, 250, 500, 750, until 1000 and 2000 μM. To determine the effect of the addition of MGO scavenger for protein samples at the highest concentration of G3P or MGO (were added iso stoichiometrically Arg at 1000 μM or 2000 μM, respectively). Arg was used to prevent protein glycation with an MGO scavenger. Samples were incubated in TE buffer for 24 and 48 h at 37 °C in a recirculating bath (LAUDA Brinkmann, EcoLine RE106). In the end, residual TPI activity was determined. Native-PAGE (N-PAGE) was simultaneously performed to observe the charge of quaternary structure and structural instability due to alterations in protein.

4.8.1. On enzyme Activity

The residual activity of HsTPI-WT, and mutant C217K and E104D enzymes was determined at each incubation time to observe enzymatic inhibition within the intracellular range of normal concentrations of G3P or MGO explored in the enzymes. To determine residual enzyme activities, 1 mM of G3P substrate was added to the coupled reaction.

4.8.2. Enzyme Stability and Migration Pattern in Native and SDS-PAGE of Glycated TPIs

After incubation of HsTPI-WT, C217K and E104D by 24 or 48 h at 37 °C, N-PAGEs were run for 3 h at 7 mA.; in Tris buffer 13 mM (Tris, MP Biomedicals, Cat. No. SKU:02103133.1) and 96 mM Glycine (J.T. Baker, Cat. No. 4057-02), at pH 8.5 to show changes of quaternary structure or charge, unfolding and aggregation by the effect of G3P or MGO were performed with 5-10 μg of protein per lane. Electrophoresis were carried out in an electrophoretic chamber (Hoeffer SE250 Mighty Small II Mini Vertical Electrophoresis Unit) with 0.75 mm thick gels to determine the effect on the structural integrity of the enzymes vs their control without G3P or MGO vs treatments.

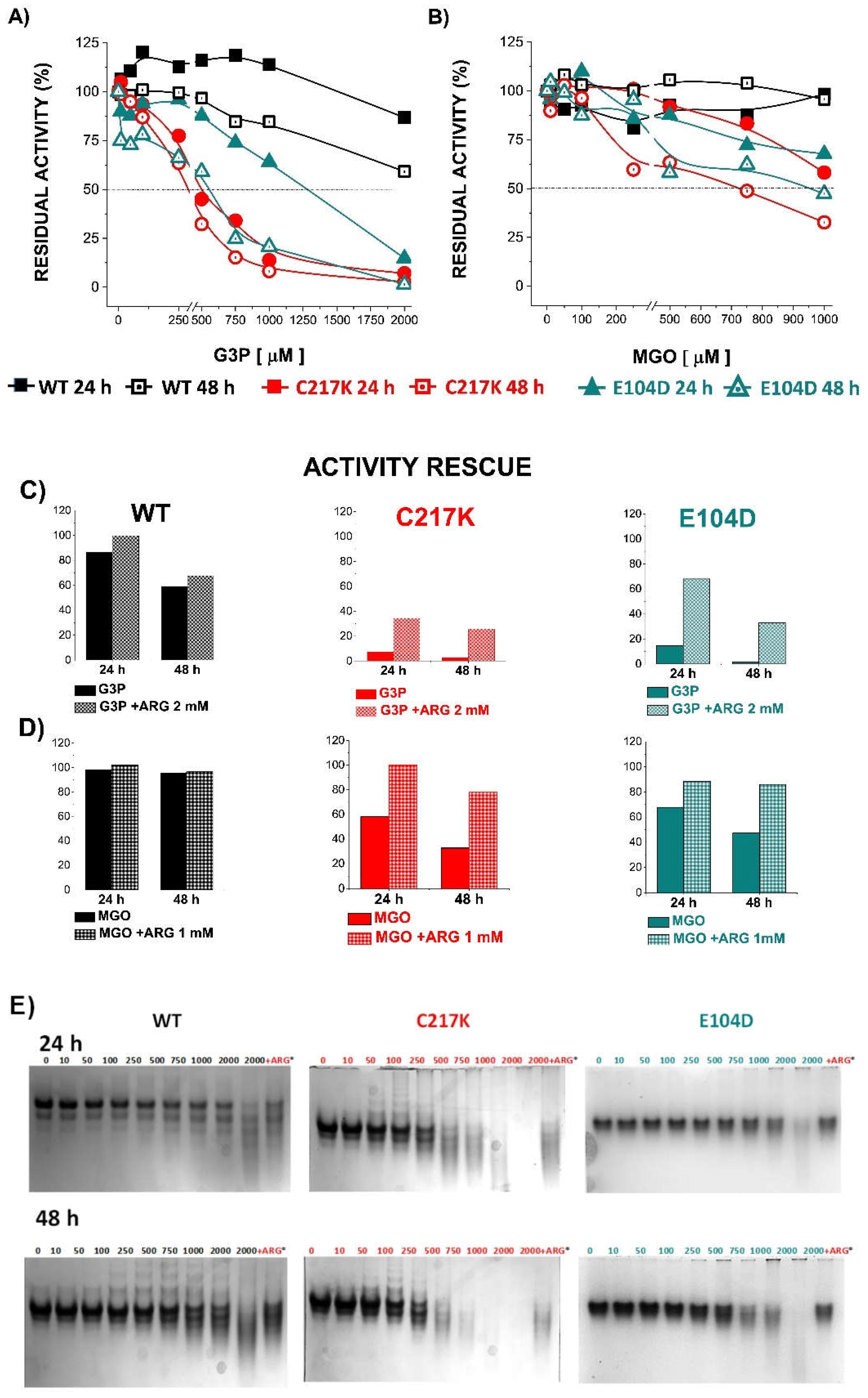

4.9. Western Blot of the Enzymes Exposed to MGO and G3P

The extensive alterations in C217K, N-PAGE, and SDS-PAGE were carried out to show the structural alteration and instability due to adduct formation. Protein samples of C217K mutant previously incubated plus-G3P or plus-MGO (20 mM) by 500 h at 37 °C samples were loaded 5 μg/lane in N-PAGE to appreciate the alteration due to adducts formation and modifications over quaternary structure, and 10 μg/lane in SDS-PAGE at 12% to evidenced aggregates originated by G3P or MGO incubations by 500 h in C217K enzyme.

Protein samples of this enzyme C217K incubated MGO or G3P (20 mM) were revealed, and the presence of ARGp adduct was evidenced by Western blot vs anti-MGO and anti-HsTPI. Briefly, 1.5 μg of protein treated was loaded per lane on SDS-PAGE 12%, and lane 1 included prestained relative mass standards (MWM) (BioRad Kaleidoscope™ Prestained Protein Standards #1610375). Electrophoresis was carried out for ½ h to 90 V and 65 min. at 185 V.

Electrophoretic SDS-PAGE gel, as well as PVDF membranes (Amersham™ Western blotting membrane Hybond®P, PVDF 0.22 μm, Cat. No. GE10600021), were embedded in absolute methanol (J.T. Baker grade HPLC, CatNo. 9093-03) and equilibrated in transfer buffer Trizma-base 24 mM, (SIGMA, Cat. No. T1503-500G); 192 mM Glycine (MP, Cat. No. 194825); 0.1 % SDS (SIGMA Cat.No. L4390-500G) and 20% Methanol at pH 8.3 for 15 min, of shaking. The PVDF membrane was transferred for 1 h at 20 V. in a horizontal transfer chamber (BIO-RAD, Trans-Blot® SD Semi-Dry Electrophoretic Transfer Cell Cat.No. 170-3940).

After transfer, the membranes were blocked with TBS-Tween-20 buffer (TBS-T) + 8% BSA at pH 7.6, in constant shaking for 1 h at room temperature. TBS-T buffer (10 mM Trizma-Base; 150 mM NaCl (VWR Cat.No. 0241-2.5KG); 0.1% Tween 20) was used to perform 2 washes, each for 10 min.

The membranes were incubated in TBS-T (0.1 %) + BSA 1% overnight at 4 °C and shaken (10 mL) with 1st Ac anti-methylglyoxal (α-MGO) (ABCAM, [9F11] ab243074) at Dil. 1:1000; or 1st Ab anti-HsTPI (α-HsTPI) 1:1000 (SantaCruz H11, Cat.No. sc-166785 HRP). After incubation, 3 washes were given in TBS-T for 10 min at room temperature.

Subsequently, 2nd Ab, peroxidase-bound anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling HRP-linked, Cat.No. 7076s) was added in TBS-T at 1:3000 + BSA 1% for 1 h at room temperature and shaked; subsequently, three washes of TBS-T for 10 min each. Detection of target proteins was carried out with luminol Santacruz Biotec (ImmunoCruz Western Blotting Luminol Reagent, Cat.No. sc-2048; Santacruz Biotechnology, Inc.) in a transilluminator (Bio-Rad, ChemiDoc XRS+ Gel Imaging System).

4.10. Refractory Proteolysis in C217K Glycated by MGO

Limited proteolysis of AGEs-modified C217K enzyme vs WT HsTPI and C217K enzymes without exposure to MGO but incubated by 500 h were proteolyzed vs Proteinase K. The proteolytic susceptibility of C217K without or plus-MGO was determined to evidence the higher MM species as aggregates that could be refractory to proteolysis; therefore, the samples WT, C217K. Briefly, the proteolysis kinetics in mol.-mol. ratio, 1:0.265, at 1 mg/mL vs Proteinase K, respectively, with controls WT, and C217K and C217K plus-MGO were incubated in Proteinase K (SIGMA-Aldrich Cat.No. P2308-1G) to carry out kinetic proteolysis in enzymes incubates since (0, 30, 65, 130 180, 210, 240, 270 and 300 min.) in a recirculation batch at 30 °C. The reactions of proteolytic digestions were arrested with 5 mM Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, SIGMA, Cat.No. 78830-5G). After the stop de reactions of digestion, the residual activity of controls and proteolyzed HsTPI was obtained for both enzymes according to

Section 4.3. The samples were loaded in a 16 % SDS-PAGE previously added 0.4 M DTT and boiled for five min. The method was previously described in [

30].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M.-M., G.H.-A., S.E-F.; methodology, I.M.-M., G.H.-A., I.G-T., G.L.-V., L.A.F.-L., and S.G.-M.; software, S.E.-F.; validation, I.M.-M., and L.A.F.L.; formal analysis, I.M.-M., and S.E.-F; investigation, I.M.-M., S.E.-F., G.H.-A.; resources, S.E.-F., L.A.F.-L.; original draft preparation, I.M.-M.; writing—review and editing, I.M.-M., S.E.-F., G.L.-V., I.G-T., S.G.-M., and L.A.F.-L.; visualization, L.A.F.-L., G.H.-A., and (S.G.-M.); supervision, I.M.-M, and S.E.-F.; project administration, I.M.-M.; funding acquisition, S.E.-F and L.A.F.-L.

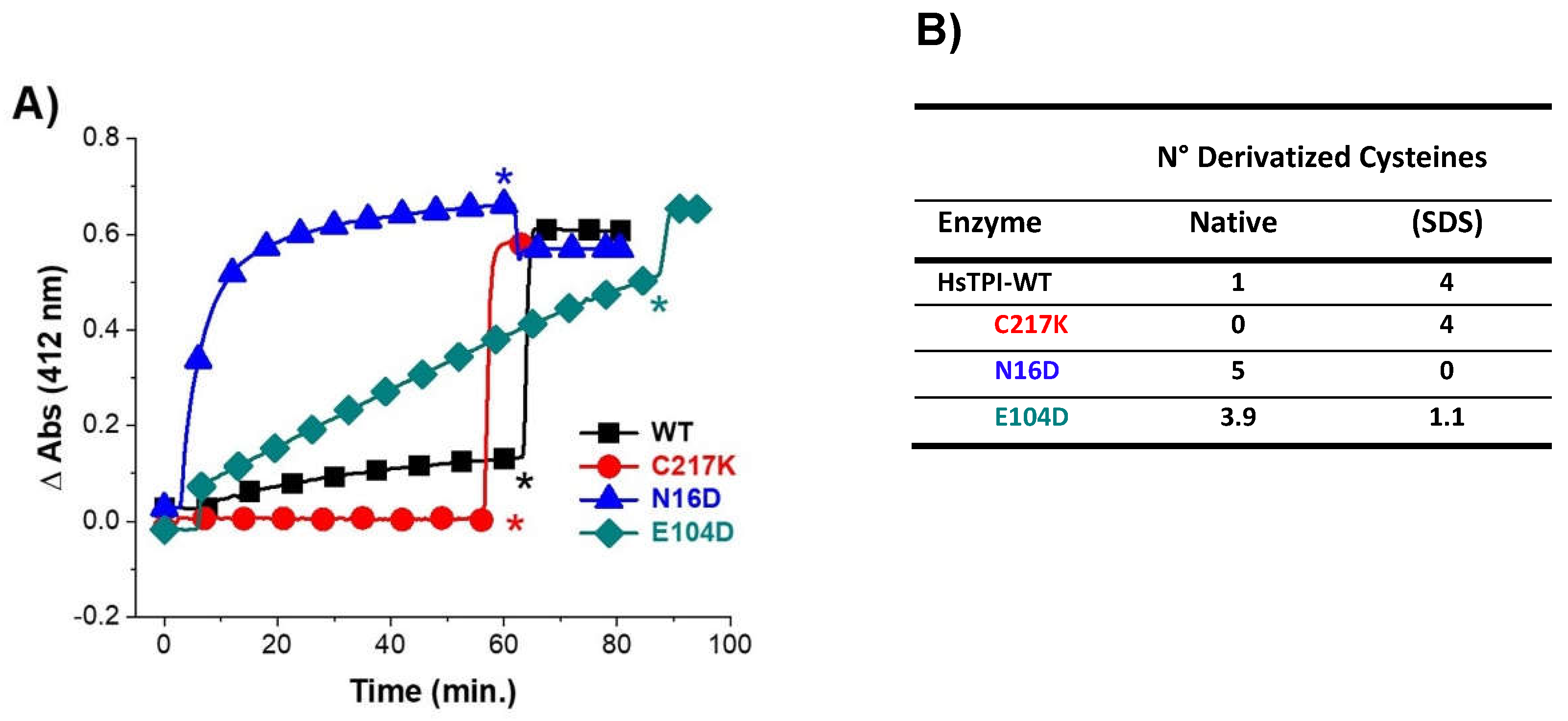

Figure 1.

Permeability by derivatization of free Cys in WT-HsTPI, C217K, N16D, and E104D mu-tants under native conditions (A), and the quantification of derivatized Cys (B). The samples containing 200 µg of protein were incubated for 54 h at 37 °C in TE buffer at pH 7.4 plus-G3P 1 mM. These samples were exposed to DTNB 4 mM, and the absorbance was monitored at 412 nm for 60 min. after SDS was added by complete denatured. Asterisks show the addition of SDS 10 %. HsTPI-WT (black squares). E104D mutant (green diamonds). C217K mutant (red circles). N16D mutant (blue triangles). These results were representative of qualitatively identical duplicate experiments.

Figure 1.

Permeability by derivatization of free Cys in WT-HsTPI, C217K, N16D, and E104D mu-tants under native conditions (A), and the quantification of derivatized Cys (B). The samples containing 200 µg of protein were incubated for 54 h at 37 °C in TE buffer at pH 7.4 plus-G3P 1 mM. These samples were exposed to DTNB 4 mM, and the absorbance was monitored at 412 nm for 60 min. after SDS was added by complete denatured. Asterisks show the addition of SDS 10 %. HsTPI-WT (black squares). E104D mutant (green diamonds). C217K mutant (red circles). N16D mutant (blue triangles). These results were representative of qualitatively identical duplicate experiments.

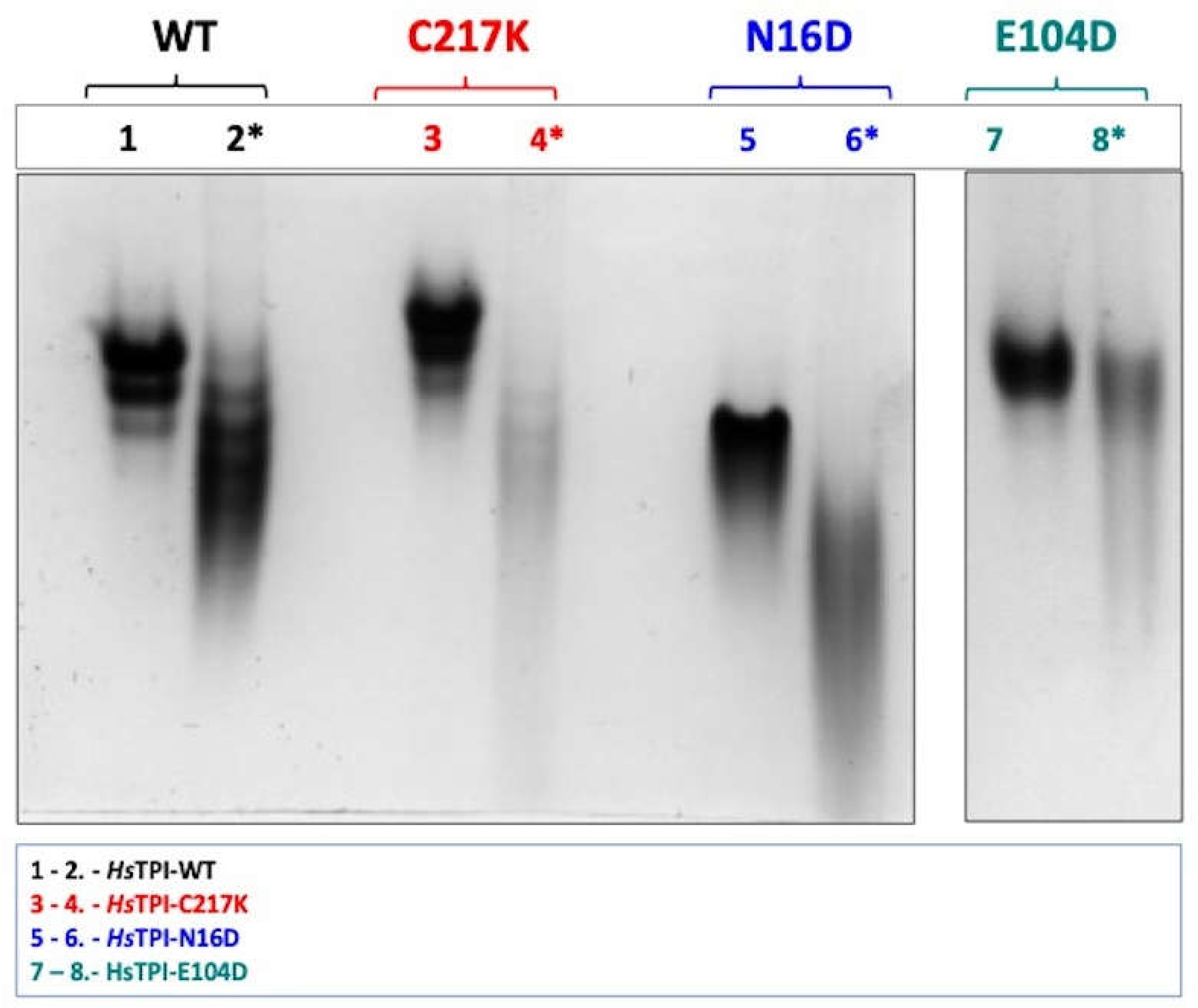

Figure 2.

Enzyme catalysis induces differential electrophoretic mobility patterns. Enzyme samples were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C without or plus-G3P 1 mM. Lanes 1-2 show the differences between WT enzymes without and with-G3P, respectively (black). Lanes 3-4 show C217K mutant (red). Lanes 5-6 N16D mutant (blue). Lanes 7-8 E104D mutant (green). 10 µg protein/lane, (*) plus-G3P were loaded. The N-PAGE is representative of is representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 2.

Enzyme catalysis induces differential electrophoretic mobility patterns. Enzyme samples were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C without or plus-G3P 1 mM. Lanes 1-2 show the differences between WT enzymes without and with-G3P, respectively (black). Lanes 3-4 show C217K mutant (red). Lanes 5-6 N16D mutant (blue). Lanes 7-8 E104D mutant (green). 10 µg protein/lane, (*) plus-G3P were loaded. The N-PAGE is representative of is representative of three independent experiments.

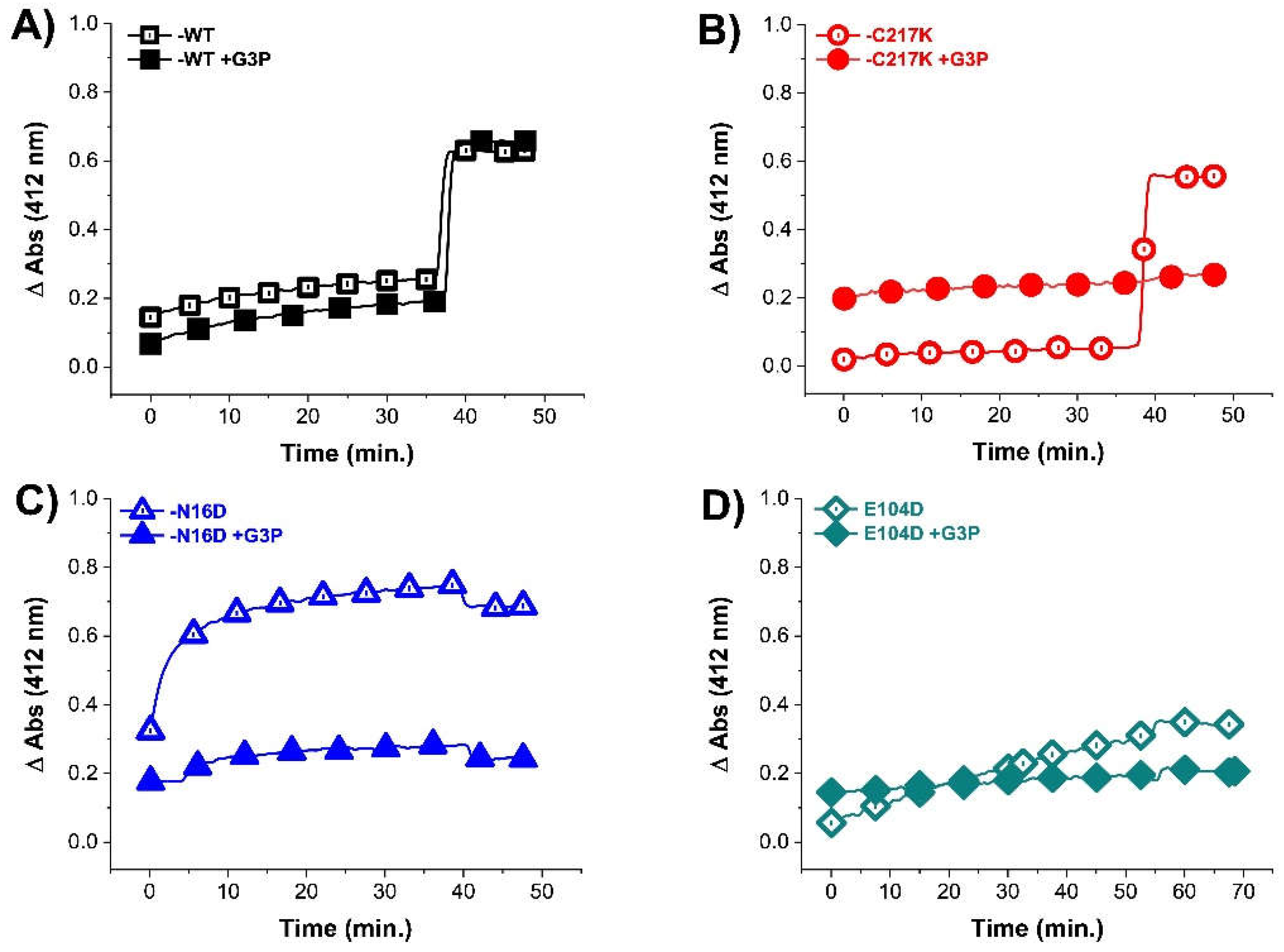

Figure 3.

Differential derivatization of Cys residues in HsTPI-WT, C217K, N16D, and E104D in the presence of G3P. After incubation of (A) WT (black squares), (B) C217K (red circles), (C) N16D (blue triangles), and (D) E104D (green diamonds), the access to Cys residues by DTNB was monitored. The enzymes G3P free samples are shown as open figures (controls). The filled figures are enzymes previously incubated for 56 h at 37 °C with G3P 1 mM. After 40-50 min. with DTNB 4 mM was added SDS. The absorbance of blank plus G3P was subtracted from each sample. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Figure 3.

Differential derivatization of Cys residues in HsTPI-WT, C217K, N16D, and E104D in the presence of G3P. After incubation of (A) WT (black squares), (B) C217K (red circles), (C) N16D (blue triangles), and (D) E104D (green diamonds), the access to Cys residues by DTNB was monitored. The enzymes G3P free samples are shown as open figures (controls). The filled figures are enzymes previously incubated for 56 h at 37 °C with G3P 1 mM. After 40-50 min. with DTNB 4 mM was added SDS. The absorbance of blank plus G3P was subtracted from each sample. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

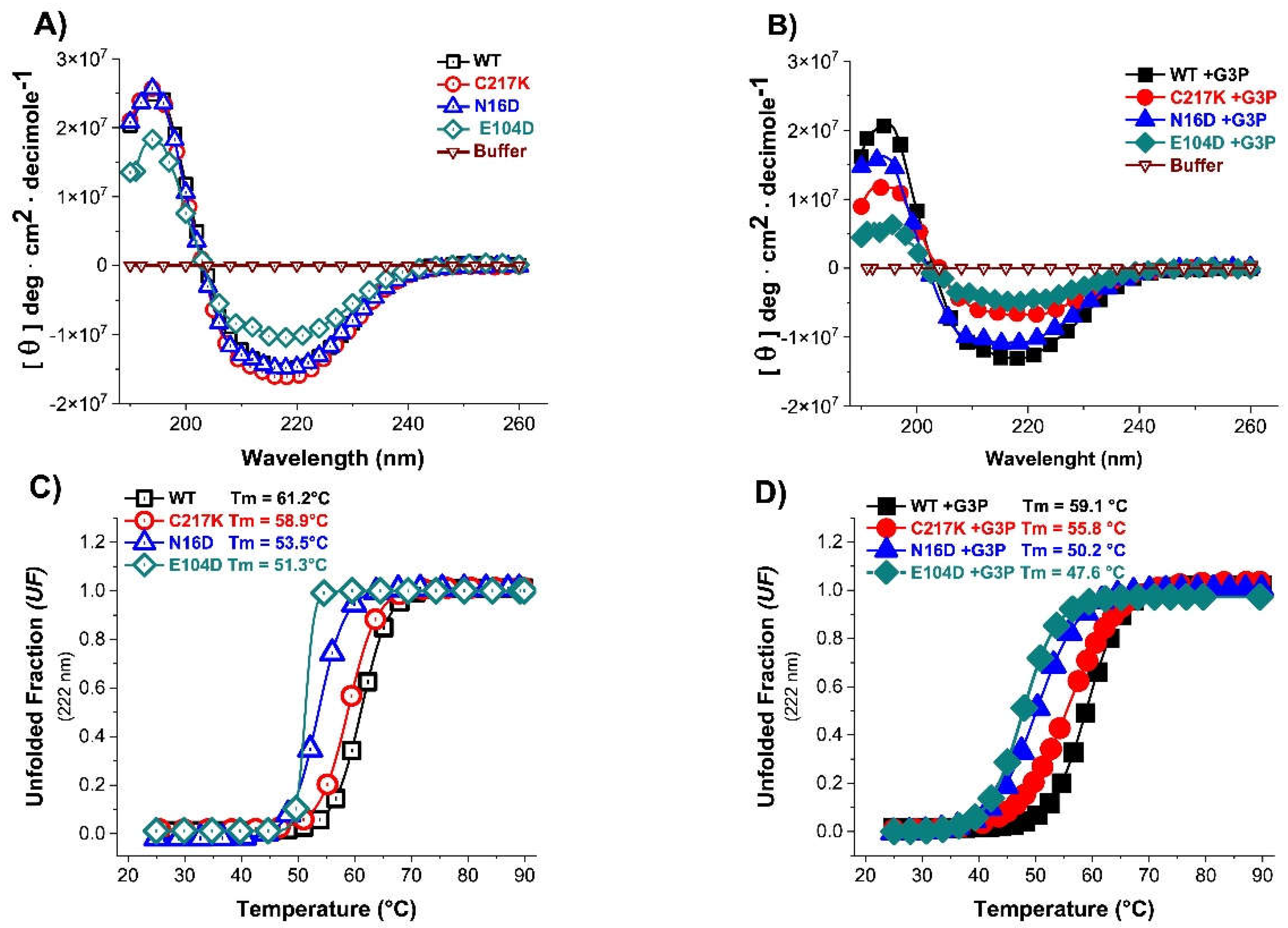

Figure 4.

Evaluation of secondary structure and global stability of HsTPI-WT and mutants. Circular dichroism (CD) in UV-Far of HsTPI-WT and mutants in absence (A) and presence of G3P. The filled figures are enzymes incubated plus-G3P. (B). Molar ellipticity spectra of enzymes (HsTPI-WT, C217K, N16D, and E104D mutants) without substrate, and presence of substrate incubated with G3P 1 mM during 24 h at 37 °C were performed. Blanks without protein were subtracted from the experimental ones; each spectrum was the average of three replicated scans. (C) Thermal stability was obtained by measuring the change in CD signal at 222 nm in response an increase of temperature from 25 to 90 °C in the absence (D) and the presence of G3P 1 mM. The fraction of unfolded protein and mean denaturation temperature (Tm) values are shown for each plot. These experiments are representative of three independent experiments, SE (±) < 5 %.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of secondary structure and global stability of HsTPI-WT and mutants. Circular dichroism (CD) in UV-Far of HsTPI-WT and mutants in absence (A) and presence of G3P. The filled figures are enzymes incubated plus-G3P. (B). Molar ellipticity spectra of enzymes (HsTPI-WT, C217K, N16D, and E104D mutants) without substrate, and presence of substrate incubated with G3P 1 mM during 24 h at 37 °C were performed. Blanks without protein were subtracted from the experimental ones; each spectrum was the average of three replicated scans. (C) Thermal stability was obtained by measuring the change in CD signal at 222 nm in response an increase of temperature from 25 to 90 °C in the absence (D) and the presence of G3P 1 mM. The fraction of unfolded protein and mean denaturation temperature (Tm) values are shown for each plot. These experiments are representative of three independent experiments, SE (±) < 5 %.

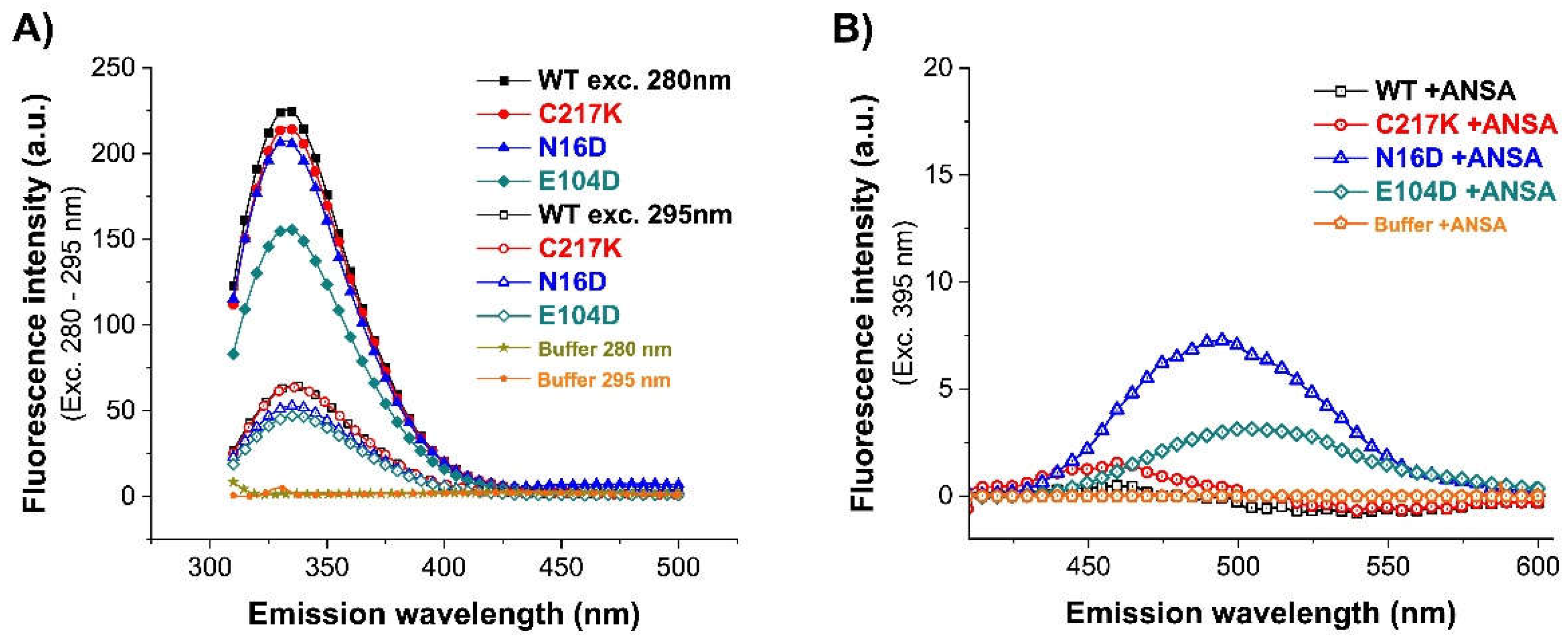

Figure 5.

Fluorescence emission spectra of the enzymes. (A) Intrinsic fluorescence, the emission spectra of scanning from 310 to 500 nm protein sample of WT, C217K, N16D and E104D were recorded after exc. at λ 280 - 295 nm. (B) Extrinsic fluorescence spectra without and with 150 μM ANSA were scanned from 400 to 600 nm after exc. at λ 395 nm. Blanks without protein were subtracted from the experimental ones; each spectrum was the average of three replicated scans.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence emission spectra of the enzymes. (A) Intrinsic fluorescence, the emission spectra of scanning from 310 to 500 nm protein sample of WT, C217K, N16D and E104D were recorded after exc. at λ 280 - 295 nm. (B) Extrinsic fluorescence spectra without and with 150 μM ANSA were scanned from 400 to 600 nm after exc. at λ 395 nm. Blanks without protein were subtracted from the experimental ones; each spectrum was the average of three replicated scans.

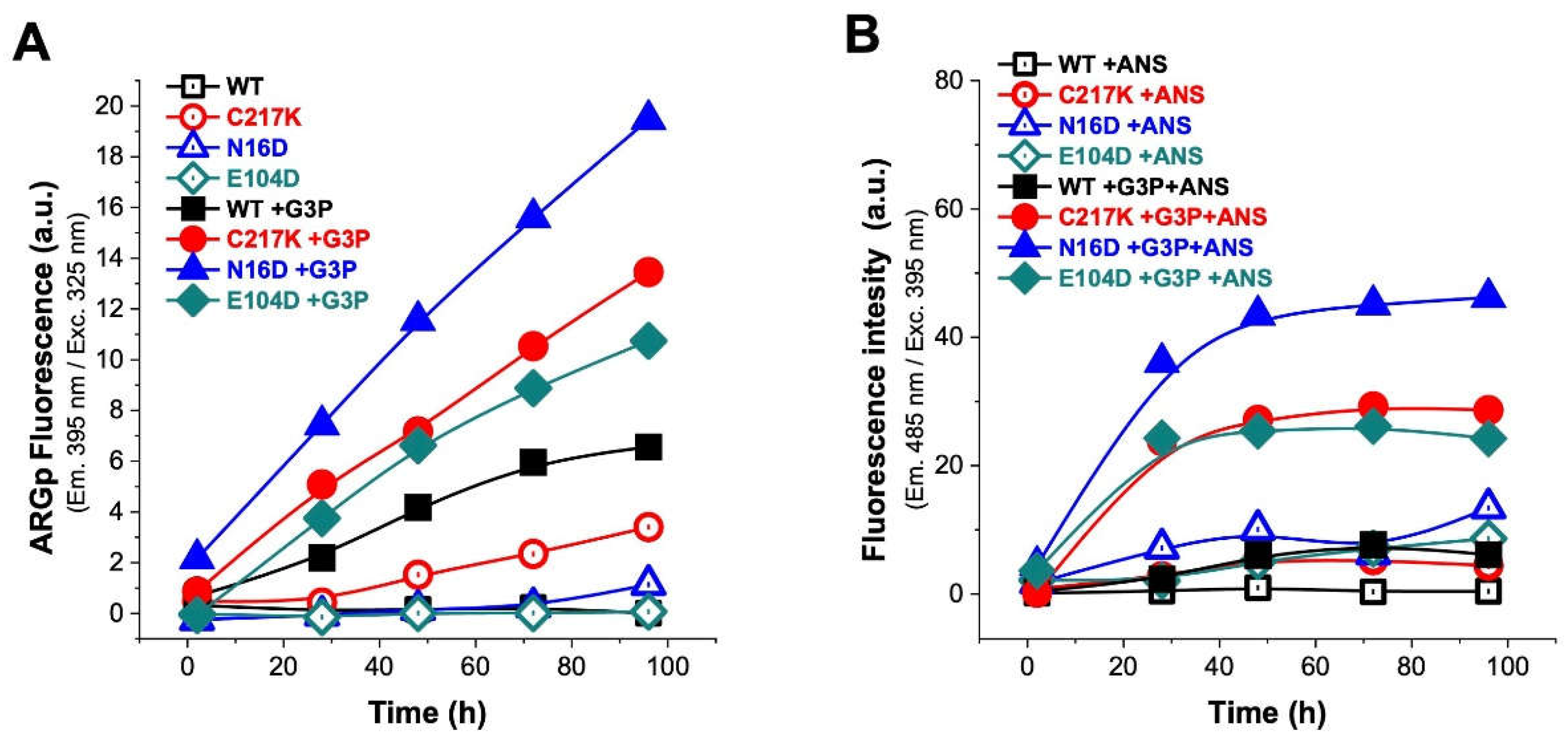

Figure 6.

Analysis of structural effects exerted by G3P on TPI’s. Enzymes exposed to G3P readings from 2, 28, 48, 72, and 96 h at 37 °C. (A) Protein samples HsTPI-WT C217K, N16D and E104D mutants were incubated with G3P 2 mM (2, 28, 48, 72 and 96 h) and then analyzed by λ exc. at 325 nm to obtain λ em. scans at 340-600 nm., with plot of fluorescence intensity signal at 395 nm. (B) The ANSA assay was performed under the same conditions. The samples were recorded at λ em. 400 to 600 nm with λ exc. 395 nm., and plot signal at 485 nm. All assays were carried out in triplicate.

Figure 6.

Analysis of structural effects exerted by G3P on TPI’s. Enzymes exposed to G3P readings from 2, 28, 48, 72, and 96 h at 37 °C. (A) Protein samples HsTPI-WT C217K, N16D and E104D mutants were incubated with G3P 2 mM (2, 28, 48, 72 and 96 h) and then analyzed by λ exc. at 325 nm to obtain λ em. scans at 340-600 nm., with plot of fluorescence intensity signal at 395 nm. (B) The ANSA assay was performed under the same conditions. The samples were recorded at λ em. 400 to 600 nm with λ exc. 395 nm., and plot signal at 485 nm. All assays were carried out in triplicate.

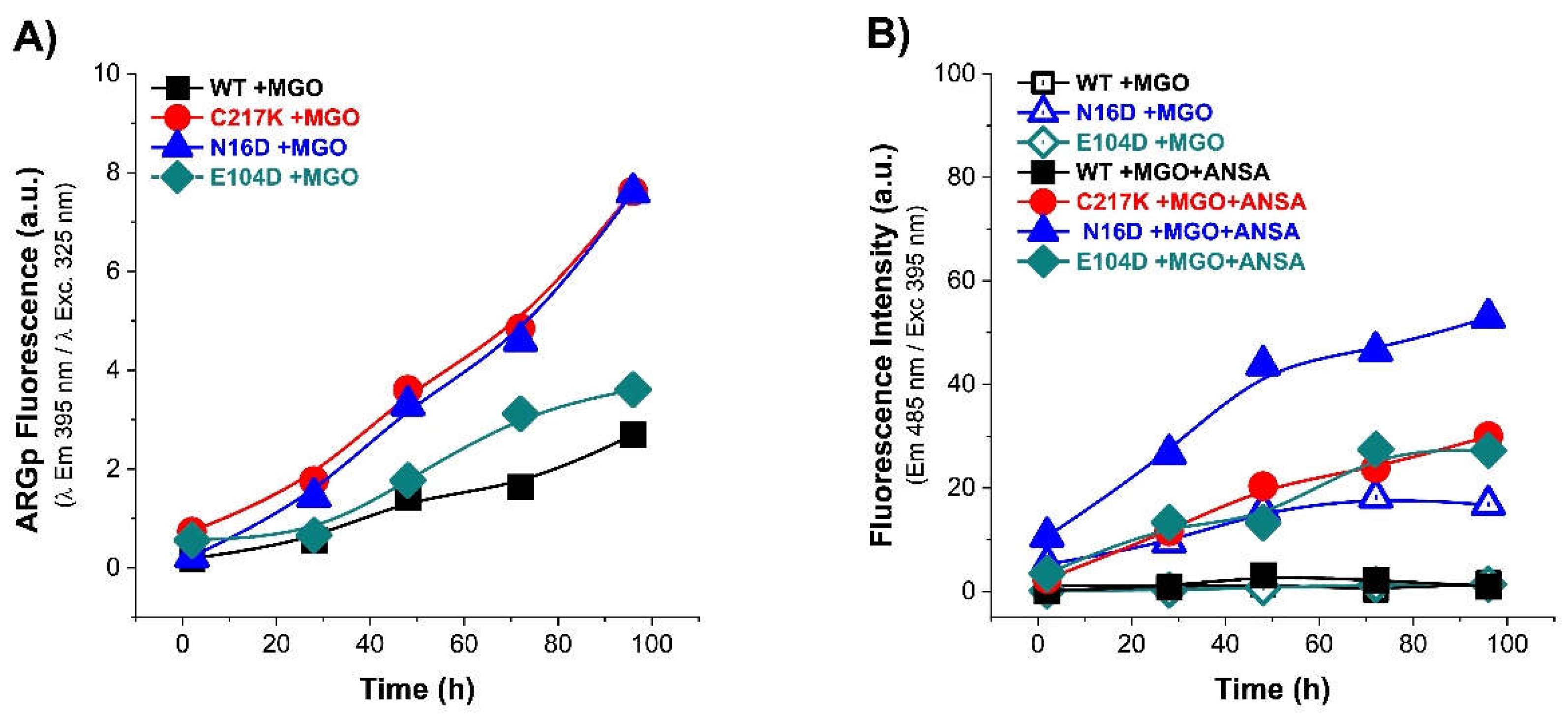

Figure 7.

Analysis of structural effect exerted by MGO on TPIs. (A) Shows the increased signal from the ARGp adduct with respect to incubation time in enzymes exposed to MGO 1 mM readings from 2, 28, 48, 72, and 96 h at 37 °C. (B) The addition of 150 μM ANSA showed the increase of hydrophobic patches on the exposed surface of the protein with respect to time exposure. Representation of enzymes: (WT, black squares); mutants, (C217K, red circles) (N16D, blue triangles) and (E104D, green diamonds); empty squares for (B) shows treatments without ANSA (incubation controls), filled squares represent enzymes plus-MGO.

Figure 7.

Analysis of structural effect exerted by MGO on TPIs. (A) Shows the increased signal from the ARGp adduct with respect to incubation time in enzymes exposed to MGO 1 mM readings from 2, 28, 48, 72, and 96 h at 37 °C. (B) The addition of 150 μM ANSA showed the increase of hydrophobic patches on the exposed surface of the protein with respect to time exposure. Representation of enzymes: (WT, black squares); mutants, (C217K, red circles) (N16D, blue triangles) and (E104D, green diamonds); empty squares for (B) shows treatments without ANSA (incubation controls), filled squares represent enzymes plus-MGO.

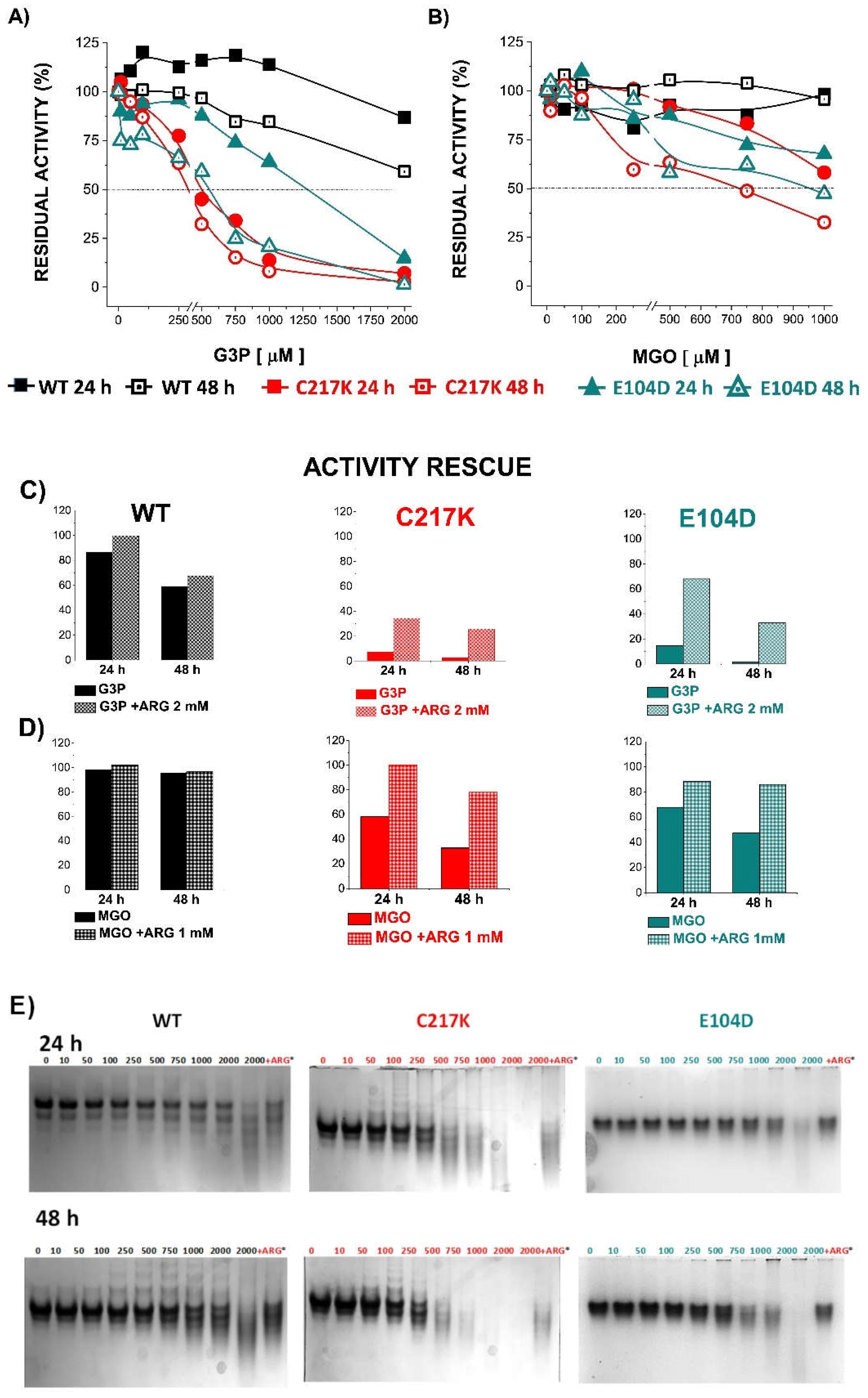

Figure 8.

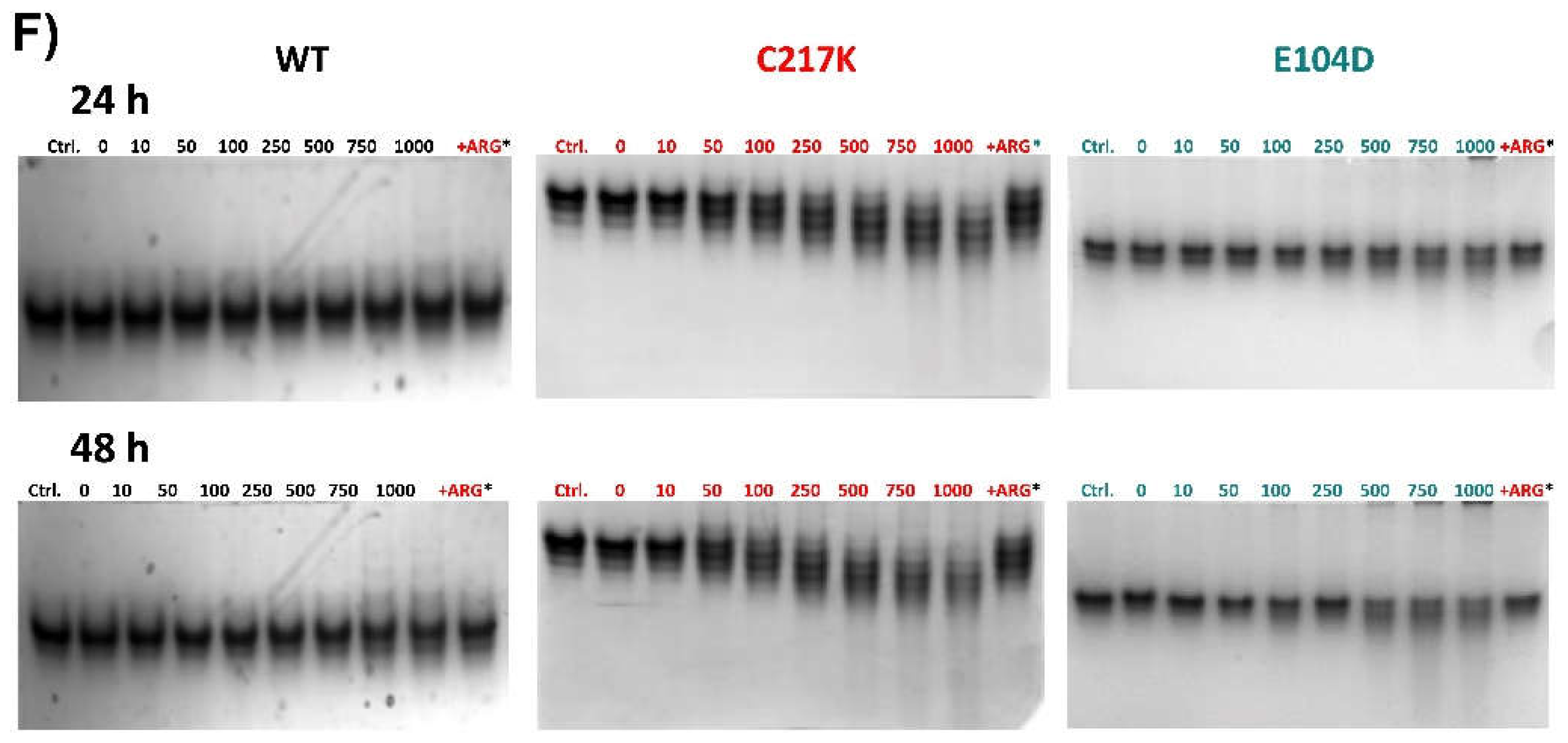

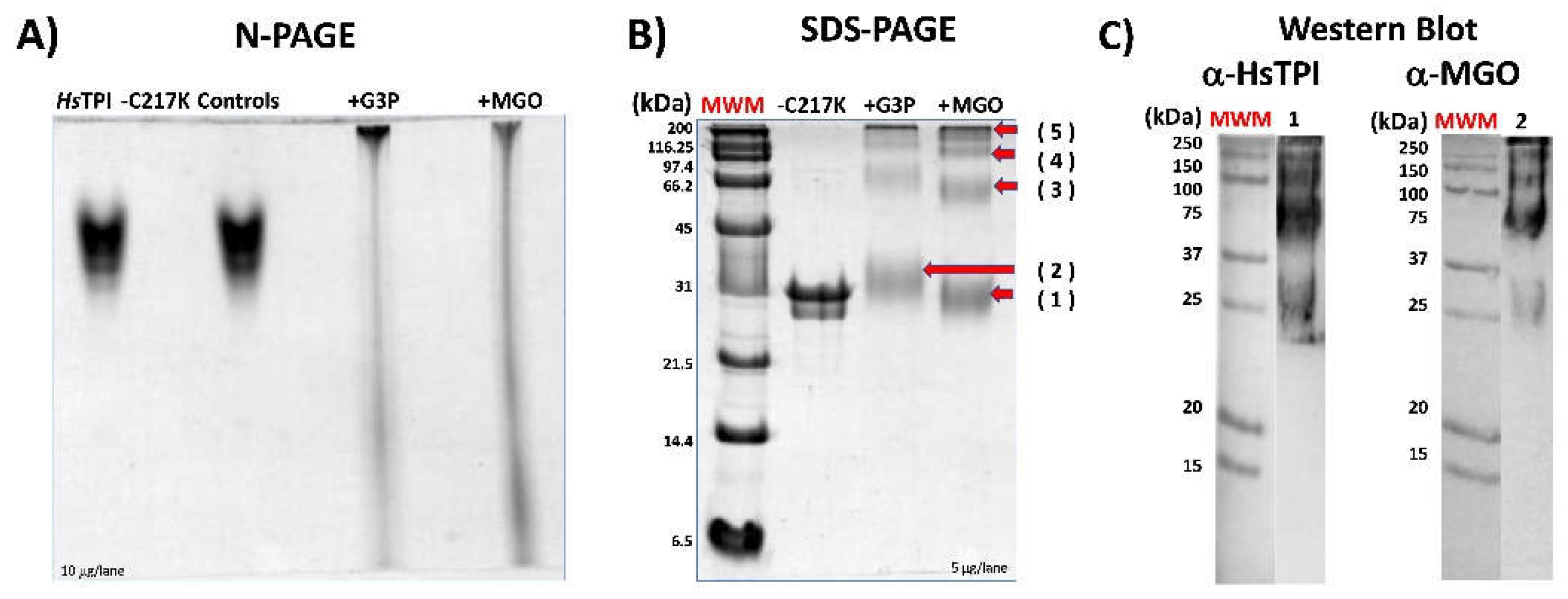

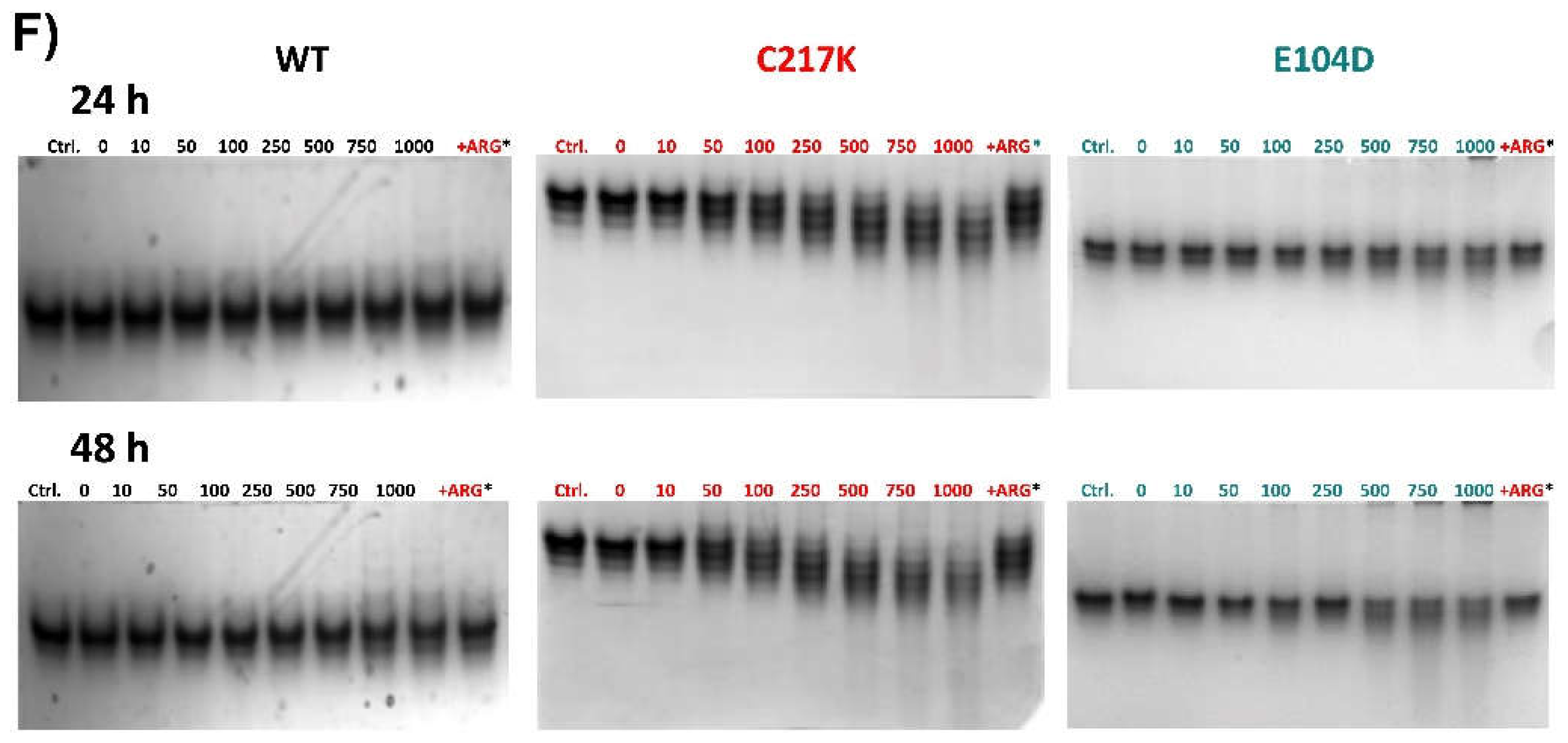

Differential kinetic and structural effect in HsTPI-WT, C217K and E104D induced by G3P or MGO. The enzyme incubations were performed twice, 24 or 48 h, with increasing G3P or MGO concentrations (0, 10-2000 or 0, 10-1000 μM, respectively). The upper left panel (A) shows the residual activity plots for the three proteins incubated plus-G3P at both times. WT 24 h (black squares) and 48 h (open black squares), for C217K at 24 h (red circles) and 48 h (open red circles), and E104D at 24 h (green triangles) and 48 h (open green triangles) respectively. The upper right panel (B) shows the comparative residual activity of proteins plus MGO. The middle panel shows bar graphs of the protector effect of plus-arginine at the highest concentratión of G3P (C) or MGO (D) at 24 or 48 h. The differential effect of Arg equimolar addition as an MGO scavenger in TPI-G3P reactions (2000 μM), or TPI-MGO 1000 μM for the WT, C217K and E104D enzymes, respectively, is shown in the last lane of N-PAGE considering the rescue of residual activity plus-Arg 2000 or plus-1000 μM, respectively (squared bars) for each enzyme at 24 or 48 h vs the protein without Arg at the same time (plain colour bars). The lower panel shows the effects of protein destabilisation observed in N-PAGE induced by G3P (E) or MGO (F) within the incubation time. Each experiment was performed in duplicate.

Figure 8.

Differential kinetic and structural effect in HsTPI-WT, C217K and E104D induced by G3P or MGO. The enzyme incubations were performed twice, 24 or 48 h, with increasing G3P or MGO concentrations (0, 10-2000 or 0, 10-1000 μM, respectively). The upper left panel (A) shows the residual activity plots for the three proteins incubated plus-G3P at both times. WT 24 h (black squares) and 48 h (open black squares), for C217K at 24 h (red circles) and 48 h (open red circles), and E104D at 24 h (green triangles) and 48 h (open green triangles) respectively. The upper right panel (B) shows the comparative residual activity of proteins plus MGO. The middle panel shows bar graphs of the protector effect of plus-arginine at the highest concentratión of G3P (C) or MGO (D) at 24 or 48 h. The differential effect of Arg equimolar addition as an MGO scavenger in TPI-G3P reactions (2000 μM), or TPI-MGO 1000 μM for the WT, C217K and E104D enzymes, respectively, is shown in the last lane of N-PAGE considering the rescue of residual activity plus-Arg 2000 or plus-1000 μM, respectively (squared bars) for each enzyme at 24 or 48 h vs the protein without Arg at the same time (plain colour bars). The lower panel shows the effects of protein destabilisation observed in N-PAGE induced by G3P (E) or MGO (F) within the incubation time. Each experiment was performed in duplicate.

Figure 9.

- Effect of glycation by G3P or MGO on HsTPI-C217K. (A) N-PAGE, plus-G3P or plus-MGO enzymes incubated for 500 h at 37 °C. Samples were loaded with 5 µg/lane. Controls correspond to protein incubated without G3P or MGO. (B) SDS-PAGE 12%. Lane 1. Prestained relative mass standards (MWM). 5 μg of HsTPI-C217K treated with G3P or MGO was loaded per lane. (C) The composite figure of Western blots of C217K plus-MGO vs 1, Ab α-HsTPI (anti-HsTPI) and 2, Ab α-MGO (anti-MGO) was revealed. Red arrows (1-5) indicate MM of soluble aggregate after time exposure to G3P or MGO.

Figure 9.

- Effect of glycation by G3P or MGO on HsTPI-C217K. (A) N-PAGE, plus-G3P or plus-MGO enzymes incubated for 500 h at 37 °C. Samples were loaded with 5 µg/lane. Controls correspond to protein incubated without G3P or MGO. (B) SDS-PAGE 12%. Lane 1. Prestained relative mass standards (MWM). 5 μg of HsTPI-C217K treated with G3P or MGO was loaded per lane. (C) The composite figure of Western blots of C217K plus-MGO vs 1, Ab α-HsTPI (anti-HsTPI) and 2, Ab α-MGO (anti-MGO) was revealed. Red arrows (1-5) indicate MM of soluble aggregate after time exposure to G3P or MGO.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters in WT-HsTPI, C217K, N16D, and E104D mutants.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters in WT-HsTPI, C217K, N16D, and E104D mutants.

| Enzyme |

Vmax

( mol · min-1 · mg-1 ) |

Km G3P

( mM ) |

kcat

( 105 M · min-1 ) |

kcat/Km

( 108 M-1 · s-1 ) |

|

| HsTPI-WT (*1) |

4091 ± 88.068 |

0.46 ± 0.03 |

2.2 |

2.8 |

|

| C217K |

13432.4 ± 1046.4 |

1.76 ± 0.287 |

7.13 |

2.43 |

|

|

N16D (*2)

|

4229.05 ± 210

|

ND |

ND |

0.25 |

|

| E104D |

5905 ± 1.22E-12 |

0.88 ± 1.3E-26 |

3.13 |

2.13 |

|