Submitted:

05 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.1.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics

2.1.2. Zootechnical Parameters

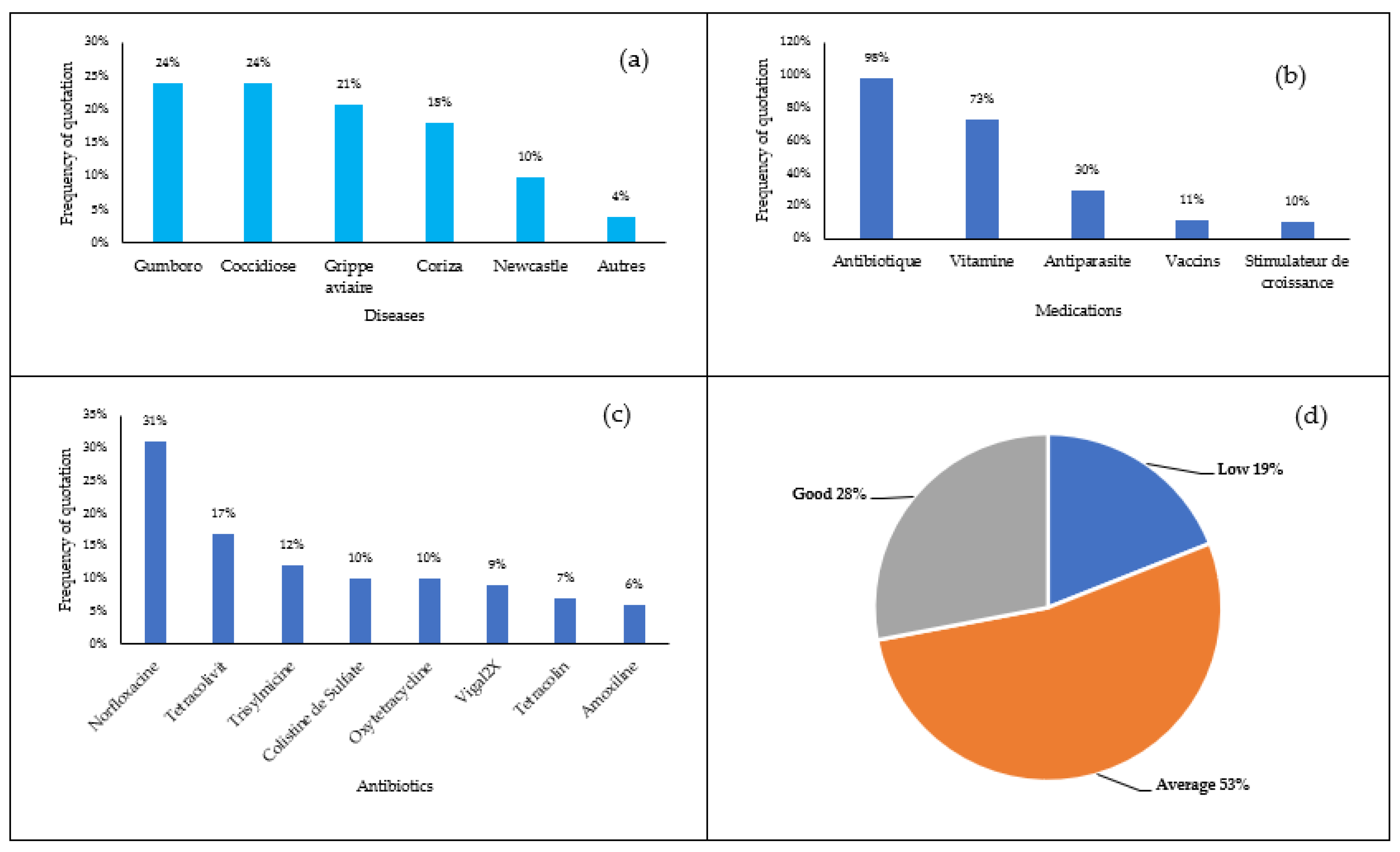

2.1.3. Disease Management

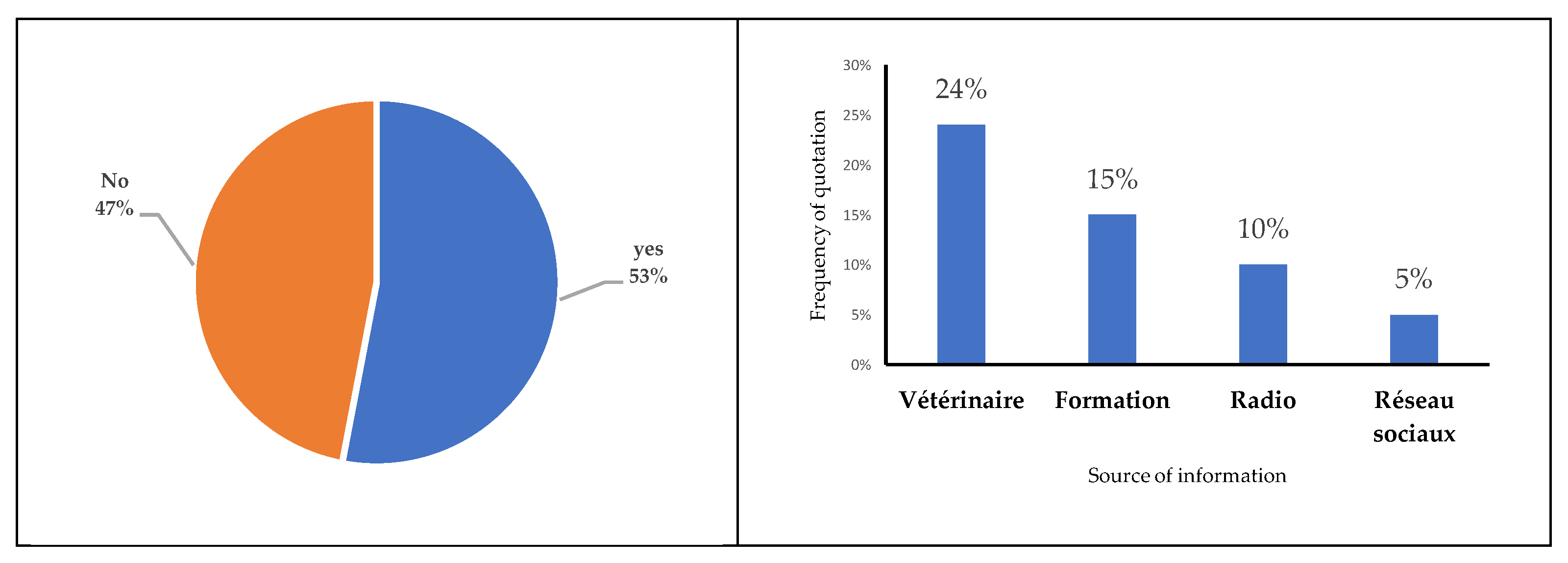

2.1.4. Antibiotic Use Practices

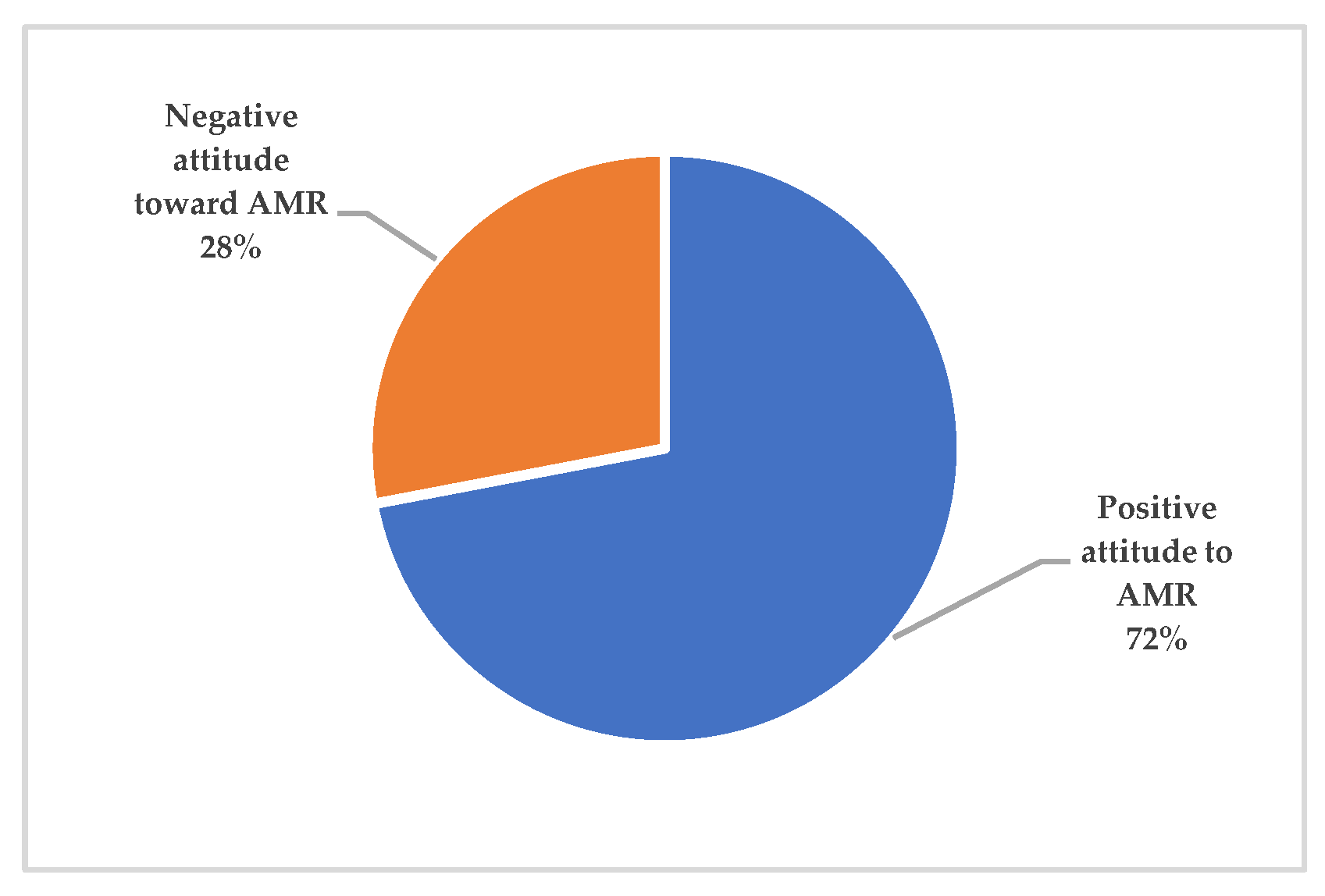

2.1.5. AMR Knowledge and Attitudes

2.1.6. Logistic Regression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

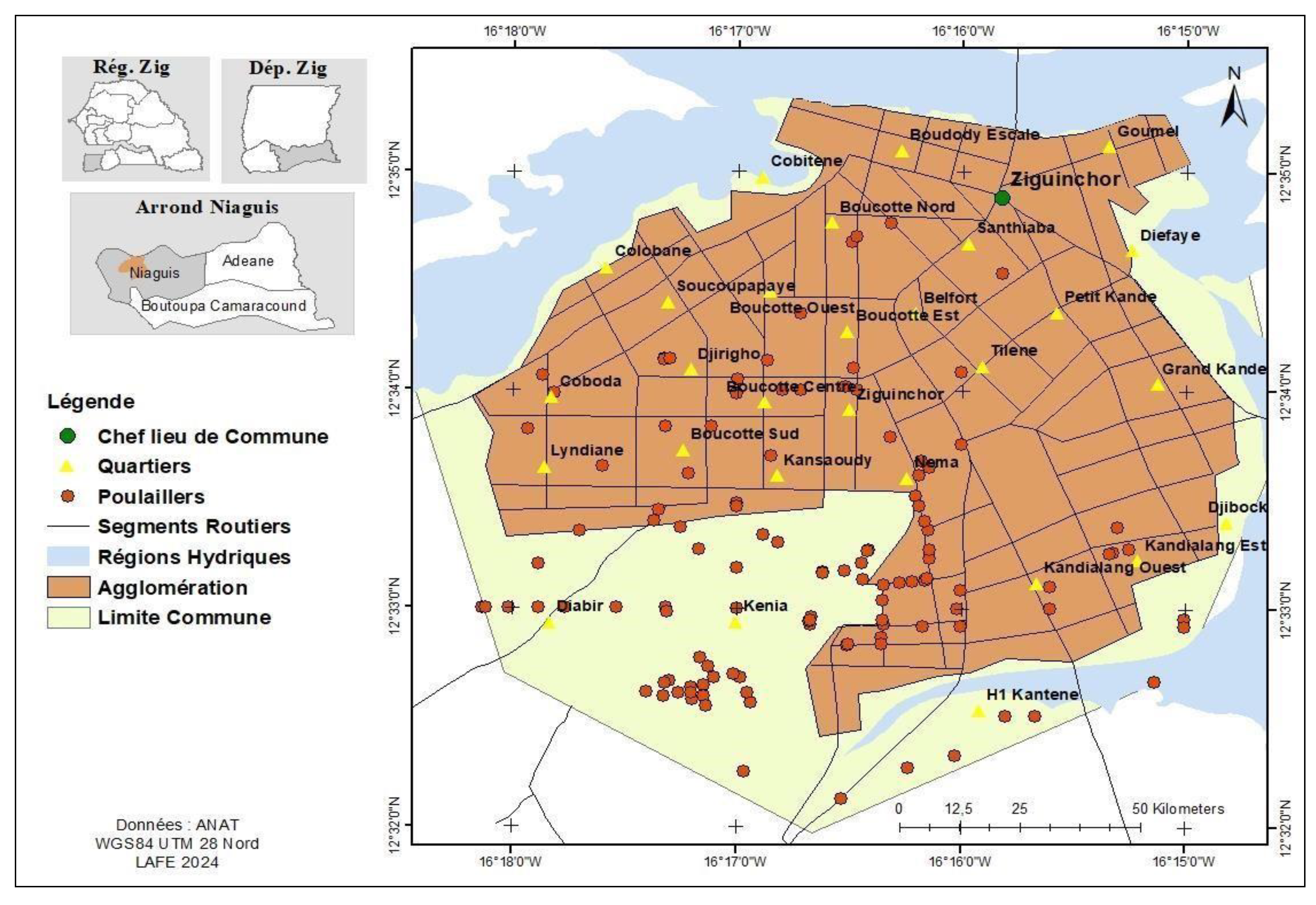

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Sampling

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Data Processing

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organizations |

| ILRI | International Livestock Research Institute |

| LAFE | Laboratoire d’Agroforesterie et d’Ecologie |

| OR | Odds Ratios |

References

- Ly, C. Aviculture et Covid-19 au Sénégal : Situation et perspectives.; Initiative Prospective Agricole et Rurale (IPAR): Senegal, 2020; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- MEPA Document de programmation pluriannuelle des dépenses (DPPD) 2020-2022; Ministère de l’Élevage et des Productions Animales: Senegal, 2019; p. 48;

- FAO The Future of Livestock in Ethiopia: Opportunities and Challenges in the Face of Uncertainty. (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- WHO Antimicrobial resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Hossain, A.; Habibullah-Al-Mamun, Md.; Nagano, I.; Masunaga, S.; Kitazawa, D.; Matsuda, H. Antibiotics, Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria, and Resistance Genes in Aquaculture: Risks, Current Concern, and Future Thinking. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 11054–11075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puvača, N.; Ljubojević Pelić, D.; Pelić, M.; Bursić, V.; Tufarelli, V.; Piemontese, L.; Vuković, G. Microbial Resistance to Antibiotics and Biofilm Formation of Bacterial Isolates from Different Carp Species and Risk Assessment for Public Health. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidara-Kane, A.; Angulo, F.J.; Conly, J.M.; Minato, Y.; Silbergeld, E.K.; McEwen, S.A.; Collignon, P.J.; Balkhy, H.; Collignon, P.; Conly, J.; et al. World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines on Use of Medically Important Antimicrobials in Food-Producing Animals. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2018, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboah, J.; Ngom, B.; Emes, E.; Fall, A.G.; Seydi, M.; Faye, A.; Dione, M. Mapping the Effect of Antimicrobial Resistance in Poultry Production in Senegal: An Integrated System Dynamics and Network Analysis Approach. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, A. Connaissances, Attitudes et Pratiques Des Éleveurs de Volailles Sur l’usage Des Antibiotiques En Zone Péri Urbaine de Dakar. PhD Thesis, Cheikh Anta Diop University: Dakar, 2022.

- Emes, E.; Faye, A.; Naylor, N.; Belay, D.; Ngom, B.; Fall, A.G.; Knight, G.; Dione, M. Drivers of Antibiotic Use in Semi-Intensive Poultry Farms: Evidence from a Survey in Senegal. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diédhiou, S.O.; Margetic, C.; Sy, O. Stratégies des acteurs de l’aviculture commerciale à Ziguinchor, Sénégal. Revue d’Elevage et de Médecine Vétérinaire des Pays Tropicaux 2022, 75, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traore, E.H.; Sall, C.; Fall, A.A.; Faye, P. Enjeux Économiques de l’influenza Aviaire Sur La Filière Avicole Sénégalaise. Bulletin du Réseau international pour le développement de l’aviculture familiale (Bulletin RIDAF) 2006, 16, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- FAO Secteur Avicole Senegal. Revues Nationales de l’élevage de La Division de La Production et de La Santé Animales de La FAO. No. 7. Rome. - Recherche Google. (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Sawadogo, A.; Kagambèga, A.; Moodley, A.; Ouedraogo, A.A.; Barro, N.; Dione, M. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Related to Antibiotic Use and Antibiotic Resistance among Poultry Farmers in Urban and Peri-Urban Areas of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robi, D.T.; Bogale, A.; Temteme, S.; Aleme, M.; Urge, B. Evaluation of Livestock Farmers’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Regarding the Use of Veterinary Vaccines in Southwest Ethiopia. Veterinary Medicine & Sci 2023, 9, 2871–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemberu, W.T.; Molla, W.; Dagnew, T.; Rushton, J.; Hogeveen, H. Farmers’ Willingness to Pay for Foot and Mouth Disease Vaccine in Different Cattle Production Systems in Amhara Region of Ethiopia. PloS one 2020, 15, e0239829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebretnsae, H.; Hadgu, T.; Ayele, B.; Gebre-Egziabher, E.; Woldu, M.; Tilahun, M.; Abraha, A.; Wubayehu, T.; Medhanyie, A.A. Knowledge of Vaccine Handlers and Status of Cold Chain and Vaccine Management in Primary Health Care Facilities of Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia: Institutional Based Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0269183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravikumar, R.; Chan, J.; Prabakaran, M. Vaccines against Major Poultry Viral Diseases: Strategies to Improve the Breadth and Protective Efficacy. Viruses 2022, 14, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.Z.; Islam, M.S.; Kundu, L.R.; Ahmed, A.; Hsan, K.; Pardhan, S.; Driscoll, R.; Hossain, M.S.; Hossain, M.M. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Regarding Antimicrobial Usage, Spread and Resistance Emergence in Commercial Poultry Farms of Rajshahi District in Bangladesh. Plos one 2022, 17, e0275856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedekelabou, A.P.; Talaki, E.; Dzogbema, K.F.-X.; Dolou, M.; Savadogo, M.; Seko, M.O.; Alambedji, R.B. Assessing Farm Biosecurity and Farmers’ Knowledge and Practices Concerning Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance in Poultry and Pig Farms in Southern Togo. Veterinary world 2022, 15, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeda, B.A.; Amenu, K.; Magnusson, U.; Dohoo, I.; Hallenberg, G.S.; Alemayehu, G.; Desta, H.; Wieland, B. Antimicrobial Use in Extensive Smallholder Livestock Farming Systems in Ethiopia: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Livestock Keepers. Frontiers in veterinary science 2020, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebeyehu, D.T.; Bekele, D.; Mulate, B.; Gugsa, G.; Tintagu, T. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Animal Producers towards Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance in Oromia Zone, North Eastern Ethiopia. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0251596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speksnijder, D.C. Antibiotic Use in Farm Animals: Supporting Behavioural Change of Veterinarians and Farmers. Thesis, University of Utrecht: Netherlands, 2017.

- Chilawa, S.; Mudenda, S.; Daka, V.; Chileshe, M.; Matafwali, S.; Chabalenge, B.; Mpundu, P.; Mufwambi, W.; Mohamed, S.; Mfune, R.L. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Poultry Farmers on Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Kitwe, Zambia: Implications on Antimicrobial Stewardship. Open Journal of Animal Sciences 2022, 13, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubu, Y.; Daneji, A.I.; Mohammed, A.A.; Jibril, A.; Umaru, A.; Aliyu, R.M.; Garba, B.; Lawal, N.; Jibril, A.H.; Shuaibu, A.B. Understanding the Awareness of Antimicrobial Resistance amongst Commercial Poultry Farmers in Northwestern Nigeria. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2024, 228, 106226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Kalam, M.A.; Alim, M.A.; Shano, S.; Nayem, M.R.K.; Badsha, M.R.; Al Mamun, M.A.; Hoque, A.; Tanzin, A.Z.; Nath, C. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices on Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance among Commercial Poultry Farmers in Bangladesh. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasylva, M.; Ndour, N.; Diédhiou, M.A.A.; Sambou, B. Caractérisation Physico-Chimique Des Sols Des Vallées Agricoles de La Commune de Ziguinchor Au Sénégal. ESJ 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, C.; Larivière, V. Principales techniques d’échantillonnage probabilistes et non-probabilistes, SCI6060 – Cours, 4 (2012). Available online: https://www.studocu.com/row/document/universite-ibn-tofail/methodologie-de-recherche/tecnique-echantillonage/49353230 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Dasylva, M.; Ndour, N.; Sambou, B.; Soulard, C.T. Les micro-exploitations agricoles de plantes aromatiques et médicinales : élément marquant de l’agriculture urbaine à Ziguinchor, Sénégal. Cah. Agric. 2018, 27, 25004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjundeswaraswamy, T.S.; Divakar, S. Determination of Sample Size and Sampling Methods in Applied Research. Proceedings on engineering sciences 2021, 3, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Artino Jr, A.R. Analyzing and Interpreting Data From Likert-Type Scales. J Grad Med Educ 2013, 5, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Modalities | Proportions |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 77.04% |

| Female | 22.96% | |

| Age range | <20 | 67% |

| 21-35 | 21% | |

| >35 | 12% | |

| Education level | Primary | 21.48% |

| Secondary | 52.59% | |

| Other | 26.92% | |

| Ethnic groups | Diola | 40.74% |

| Mandingo | 20.19% | |

| Other ethnic groups | 39.07% | |

| Marital status | Married | 53.33% |

| Single | 45.93% | |

| Types of poultry production | Only broiler chickens | 96% |

| Broiler chickens and eggs | 4% | |

| Poultry training | No | 65.93% |

| Yes | 34.07% | |

| Poultry farming experience (years) | 0-4 | 40% |

| 5-10 | 31.85% | |

| > 10 | 28.15% | |

| Poultry farming is the main activity | Yes | 38.52% |

| No | 61.48% | |

| Animal species raised | Poultry | 69.64% |

| Goats | 20.74% | |

| Pigs | 4.44% | |

| Sheep | 2.96% | |

| Cattle | 2.22% | |

| Poultry species raised | Chickens | 74.82% |

| Ducks | 21.48% | |

| Guinea fowl | 2.22% | |

| Turkeys | 1.48% |

| Variables | Average | Standard deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of broilers (no.) | 331 | 1 106 | 8 | 10 000 |

| Number of laying hens (no.) | 3 292 | 3 358 | 105 | 8 000 |

| Broiler age (days) | 44.22 | 4.74 | 33 | 60 |

| Age of laying hen (days) | 196.5 | 125.59 | 4 | 365 |

| Number of eggs produced per day | 1 658.33 | 3 598.48 | 40 | 9 000 |

| Broiler sales weight (kg) | 2.53 | 0.64 | 1 | 5 |

| Broiler mortality rate (%) | 6.75 | 10.37 | 0 | 87 |

| Layer mortality rate (%) | 6.5 | 5.64 | 0 | 14 |

| Casual employees (no.) | 2.64 | 1.5 | 0 | 15 |

| Permanent employees (no.) | 1.01 | 3.61 | 0 | 27 |

| Variables | Modalities | Proportions |

|---|---|---|

| Sources of the first call for illnesses | Veterinarian | 75% |

| Para vet | 3% | |

| Poultry farmer | 22% | |

| Reasons for antibiotic use | Prevention | 31% |

| Disease treatment | 43% | |

| Limiting disease spread | 26% | |

| Subjects of antibiotic molecule administration | Healthy animals only | 2% |

| Healthy and sick birds | 98% | |

| Sources of advice on antibiotic use | Myself | 5% |

| Veterinarian | 85% | |

| Para vet | 1% | |

| Neighboring poultry farmer | 8% | |

| Reasons for stopping antibiotic treatment | Expensive treatment | 3% |

| Ineffective treatment | 7% | |

| Subject’s recovery | 40% | |

| Sale | 30% | |

| Slaughter | 20% | |

| Poultry farmers’ reaction to antibiotic treatment failure | Continue with the same treatment | 8% |

| Increase dose | 8% | |

| Change antibiotic | 27% | |

| Follow-up by vet | 23% | |

| Stop treatment | 5% | |

| Apply biosecurity | 29% |

| Appropriate practices N (%) |

Inappropriate practices N (%) |

Test Pearson Chi2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Man | 30 (28.85) | 74 (71.15) | 0.043 |

| Woman | 15 (48.39) | 16 (51.61) | ||

| Age range (years) | < 20 | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 0.914 |

| 21-35 | 30 (32.97) | 61 (67.03) | ||

| > 35 | 14 (35) | 26 (65) | ||

| Education level | Primary | 13 (36.11) | 23 (63.89) | 0.053 |

| Secondary | 28 (14.29) | 43 (60.56) | ||

| University | 4 (14.29) | 24 (85.71) | ||

| Marital status | Single | 12 (19.05) | 51 (80.95) | 0.001 |

| Married | 33 (45.83) | 39 (54.17) | ||

| Ethnic group | Diola | 19 (34.55) | 36 (65.45) | 0.656 |

| Manding | 4 (23.53) | 13 (76.47) | ||

| Others | 22 (34.92) | 41 (65.08) | ||

| Religion | Muslim | 38 (34.33) | 71 (65.14) | 0.440 |

| Christian | 7 (26.92) | 19 (73.08) | ||

| Experience (years) | < 5 | 22 (33.33) | 44 (66.67) | 0.794 |

| 5 to 10 | 13 (29.55) | 31 (70.45) | ||

| > 10 | 9 (37.50) | 15 (62.50) | ||

| Training | Yes | 17 (36.96) | 29 (63.04) | 0.521 |

| No | 28 (34.46) | 61 (68.54) | ||

| Number of chickens | <100 | 33 (57.58) | 24 (42.11) | 0.001 |

| 100 to 300 | 11 (18.64) | 48 (81.36) | ||

| More than 300 | 1 (5.56) | 17 (94.44) | ||

| >500 | 48 (78.69) | 13 (21.31) |

| Variables | Modalities | Proportions |

|---|---|---|

| AMR is a major public health problem | I agree | 61.48% |

| Neutral | 20% | |

| Disagree | 18.52% | |

| Inappropriate use of antimicrobials can hurt human health | Agree | 73.33% |

| Neutral | 9.63% | |

| Disagree | 17.04% | |

| I’m aware of the seriousness and importance of AMR | Agree | 71.22% |

| Neutral | 11.11% | |

| Disagree | 17.78% | |

| The application of bio-security measures to limit the spread of disease and the use of antibiotics to prevent AMR | Agree | 75.56% |

| Neutral | 11.11% | |

| Disagree | 13.33% |

| Variables | Knowledge OR; 95% CI; P-value |

Attitude OR; 95% CI; P-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Woman | Reference | Reference |

| Man | 0.76; 0.23-2.43; 0.644 | -0.17; -0.85-0.51; 0.625 | |

| Age | <20 | 13.92; 1.23-156.57; 0.033 | 1.59; 0.10-3.07; 0.035 |

| >35 | 0.94; 0.29-3.01; 0.926 | -0.007; -0.68-0.67; 0.983 | |

| 21–35 | Reference | Reference | |

| Education | Secondary | 1.25; 0.39-4.01; 0.704 | 0.17; -0.51 – 0.87; 0.610 |

| University | 3.73; 0.86-16.19; 0.078 | 0.84; -0.04-1.73; 0.06 | |

| Primary | Reference | Reference | |

| Marital status | Married | 2.99; 0.93-9.63; 0.065 | 0.63; -0.04-1.31; 0.068 |

| Single | Reference | Reference | |

| Experience | <5 years | 1.61; 0.42-3.14; 0.768 | 0.07; -0.50-0.62; 0.799 |

| >10 years | 0.83; 0.20-3.43; 0.803 | -0.12; -0.95-0.69; 0.759 | |

| 5-10 years | Reference | Reference | |

| Training | yes | 0.40; 0.20-3.43; 0.084 | -0.55; -1.16-0.04; 0.072 |

| No | Reference | Reference | |

| Number of chickens | <100 | 0.78; 0.31-1.98; 0.609 | -0.13; -0.68-0.40; 0.618 |

| >300 | 0.12; 0.01-1.24; 0.07 | -1.22; -2.49-0.04; 0.060 | |

| 100-300 | Reference | Reference | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).