1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the capacity of microbial pathogens to survive in the presence of antimicrobials, is considered one of the greatest threats to human health worldwide and is growing rapidly in importance (1,2). Although AMR has always existed, its increasing prevalence is driven in large part by the use of antimicrobials (AMU) by humans (3). In particular, use of antibiotics in livestock animal production is one of the biggest contributors to total AMU, and reducing this use has been identified as a policy priority (4–6). As a middle-income country with a high rate of economic growth, Senegal is identified as suffering from the ‘double-burden’ of rising antibiotic availability and meat consumption combined with rates of bacterial infections that remain high in the global context (1).

At the global level, the FAO-OIE-WHO-UNEP ‘Quadripartite’ have created a Global Action Plan on AMR which seeks to optimise antimicrobial use through a process led by national governments (7). Senegal’s most recent National Action Plan on AMR involved the animal health and food safety sectors (8). It aimed to balance rational use of antibiotics and awareness-raising on AMR with infection control across all One Health sectors. These findings, and others, will contribute to the evidence base which feeds into the upcoming 2023-27 plan.

However, antibiotics can play a therapeutic, prophylactic and growth-promoting role in livestock production (9). Thus, reducing AMU in livestock production, especially in small-scale and semi-intensive farms, may harm farmers’ livelihoods and economic security, and may contribute to food insecurity at the population level if it negatively affects farm productivity. Achieving a reduction in farm AMU will not be realistic or safe if farmers do not feel secure in doing so. It is therefore important to understand what interventions can be paired with AMU reduction, which can prevent any associated loss in farm productivity, and can make farmers feel more comfortable withdrawing or replacing antibiotics. More broadly, understanding how AMU interacts with farm practices and outcomes is key to understanding the impact of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) interventions at the national level, and for guiding AMR policy more broadly.

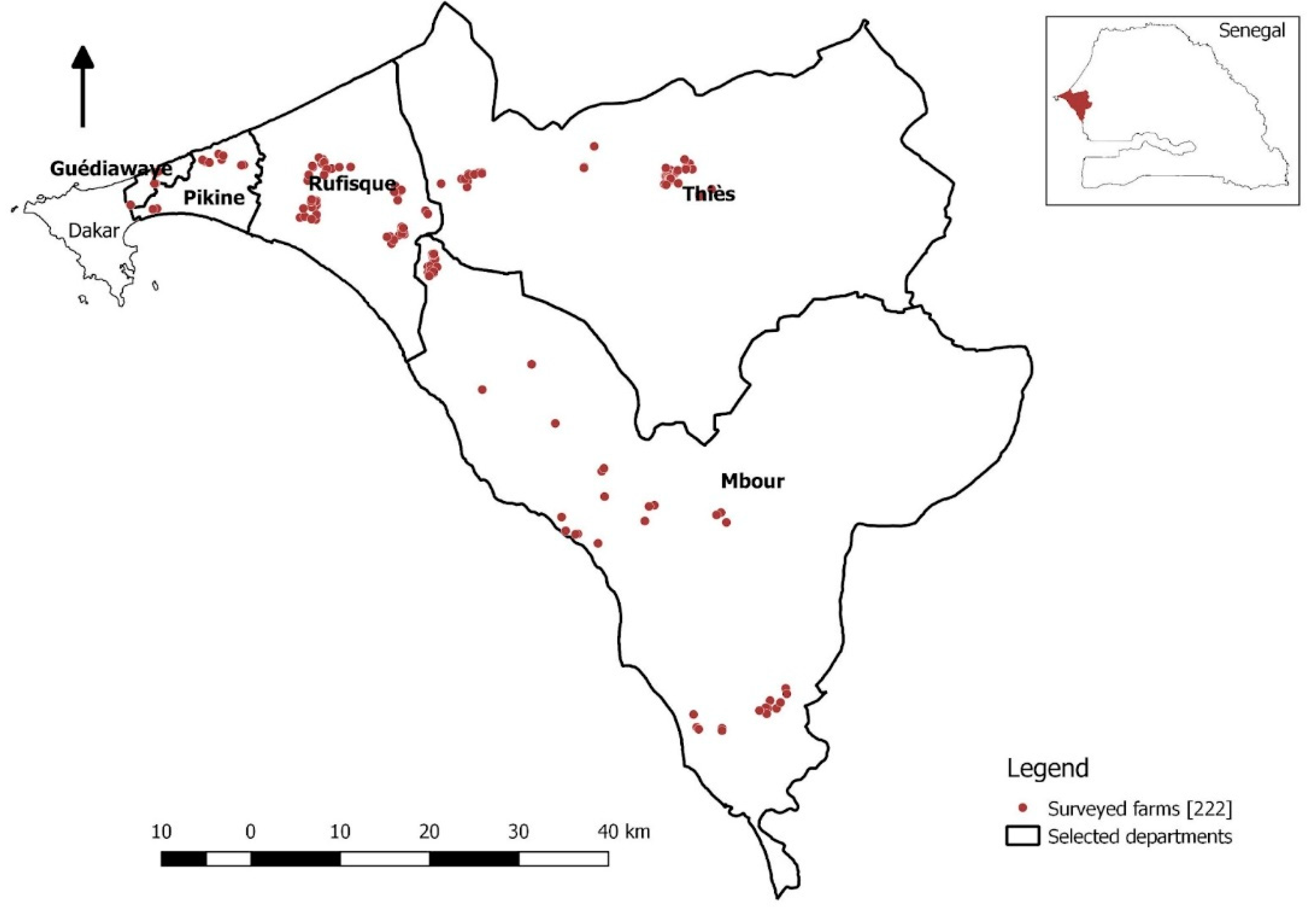

We investigated this question using the case study of semi-intensive peri-urban poultry farms in Dakar and Thiès, in Senegal. The domestic poultry industry in Senegal is rapidly growing, and is a key user of antibiotics (10,11). Semi-intensive farms were selected because they comprise a very large portion of agricultural production in Senegal and many other middle-income countries, the group of countries which is most vulnerable to the effects of AMR (12,13). In other countries, the shift from backyard farming to small- and medium-sized semi-intensive farms in recent decades has been associated with a range of novel and diverse farming practices (14), in some cases meaning more indiscriminate antibiotic use (15,16), with medium-sized farms especially likely to misuse antibiotics (17). Semi-intensive farms are also more economically vulnerable than larger-scale farms, and may have a precarious relationship to creditors and suppliers (16), making them a key target for this investigation. In Senegal, while many studies have been carried out on AMU in poultry farms, these studies tend to be descriptive and focus on mapping out knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP). This is the first study of this kind pointing to evidence on interventions to reduce AMU in Senegal.

We aimed to investigate factors which could induce farmers to reduce antibiotic use, guide more prudent use, or guard against productivity losses in the event of an antibiotic use reduction intervention.

Based on discussion among coauthors, we identified three such factors to investigate. Namely: (1) vaccination of chickens; (2) farmers’ attitudes to, and awareness of, AMR; and (3) on-farm biosecurity measures. We hypothesised that all three could lead to lower and better-informed AMU and/or could enhance productivity. For example, awareness of AMR may encourage lower and more selective AMU, and biosecurity measures and vaccination of chickens may reduce the need for antibiotics as a disease management and growth promotion tool.

Using survey data collected with a modified AMUSE survey tool (18) from 222 farms in Dakar and Thiès, we investigated:

- a)

If better biosecurity, vaccination and awareness of AMR lead to lower or more selective use of antibiotics (e.g., limiting use to therapeutic use, or avoiding use of antibiotics intended for use in humans) in poultry farms

- b)

What effect these three factors, as well as antibiotic use (defined by expenditure on antibiotics), have on farm profitability and disease incidence

After our main results, we also investigate how these factors interact with each other, and explored additional specifications.

2. Results

2.1. Descriptive Statistics

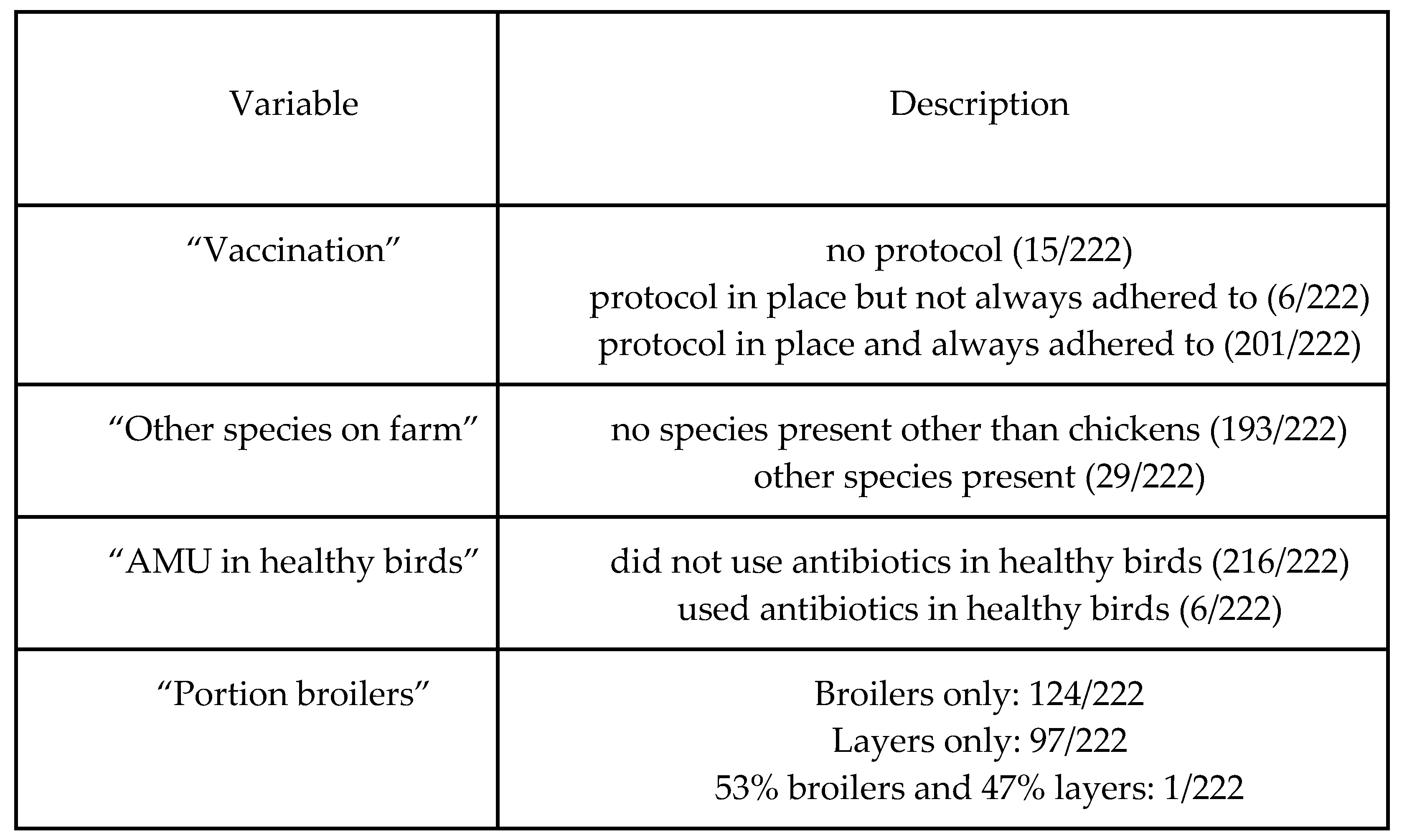

Of the 222 farms in our dataset, 124 had broilers only and 97 had layers only, with one farm having both.

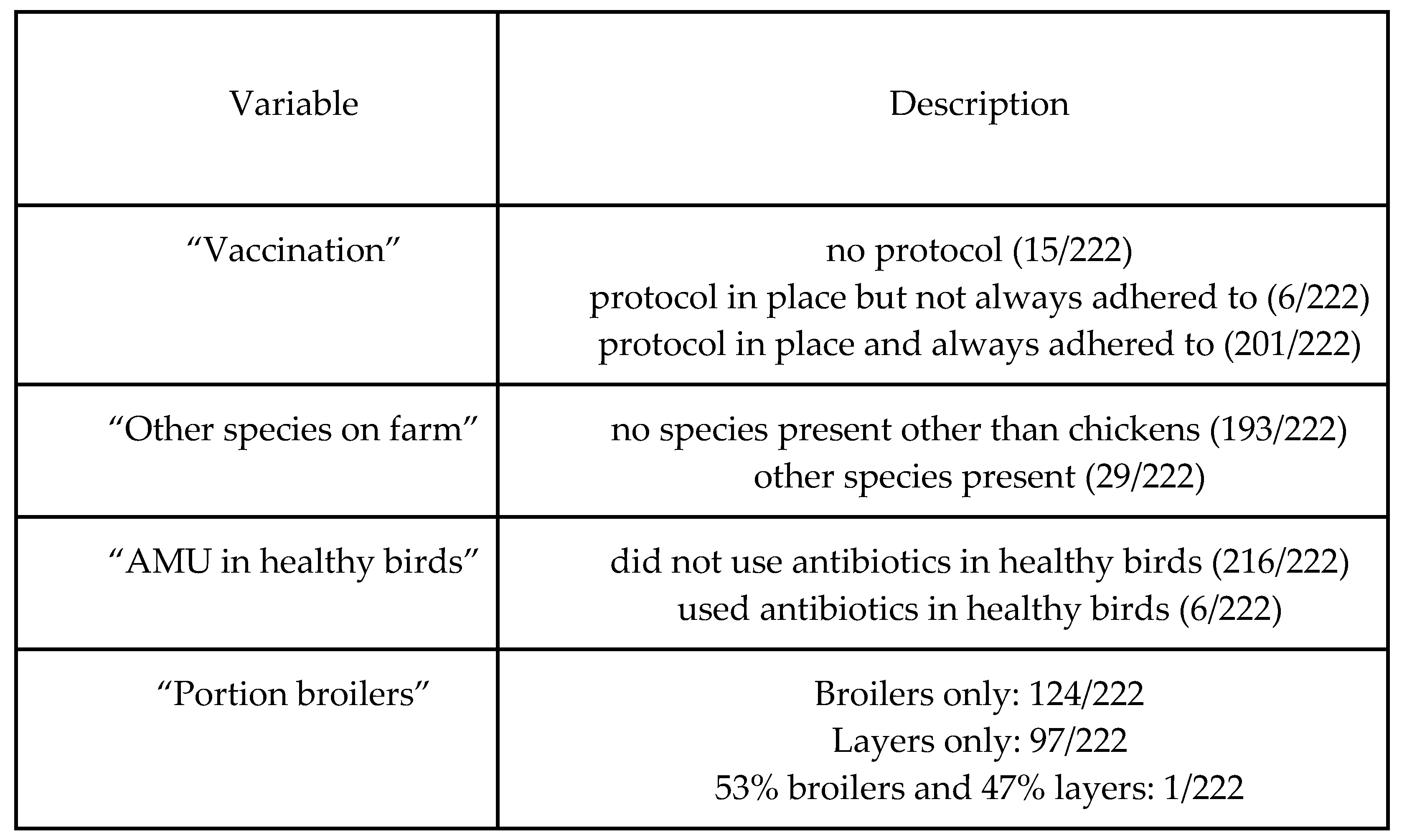

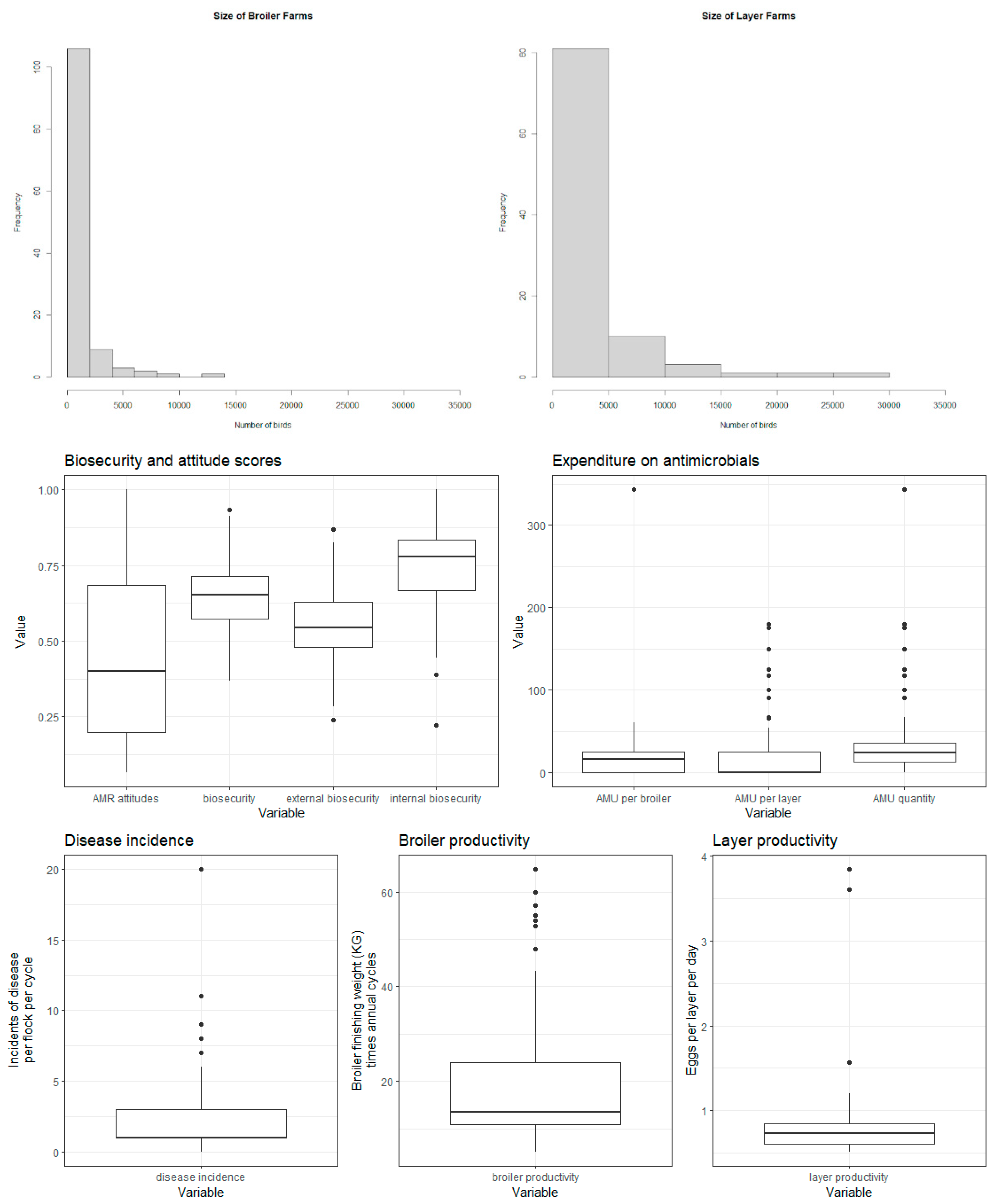

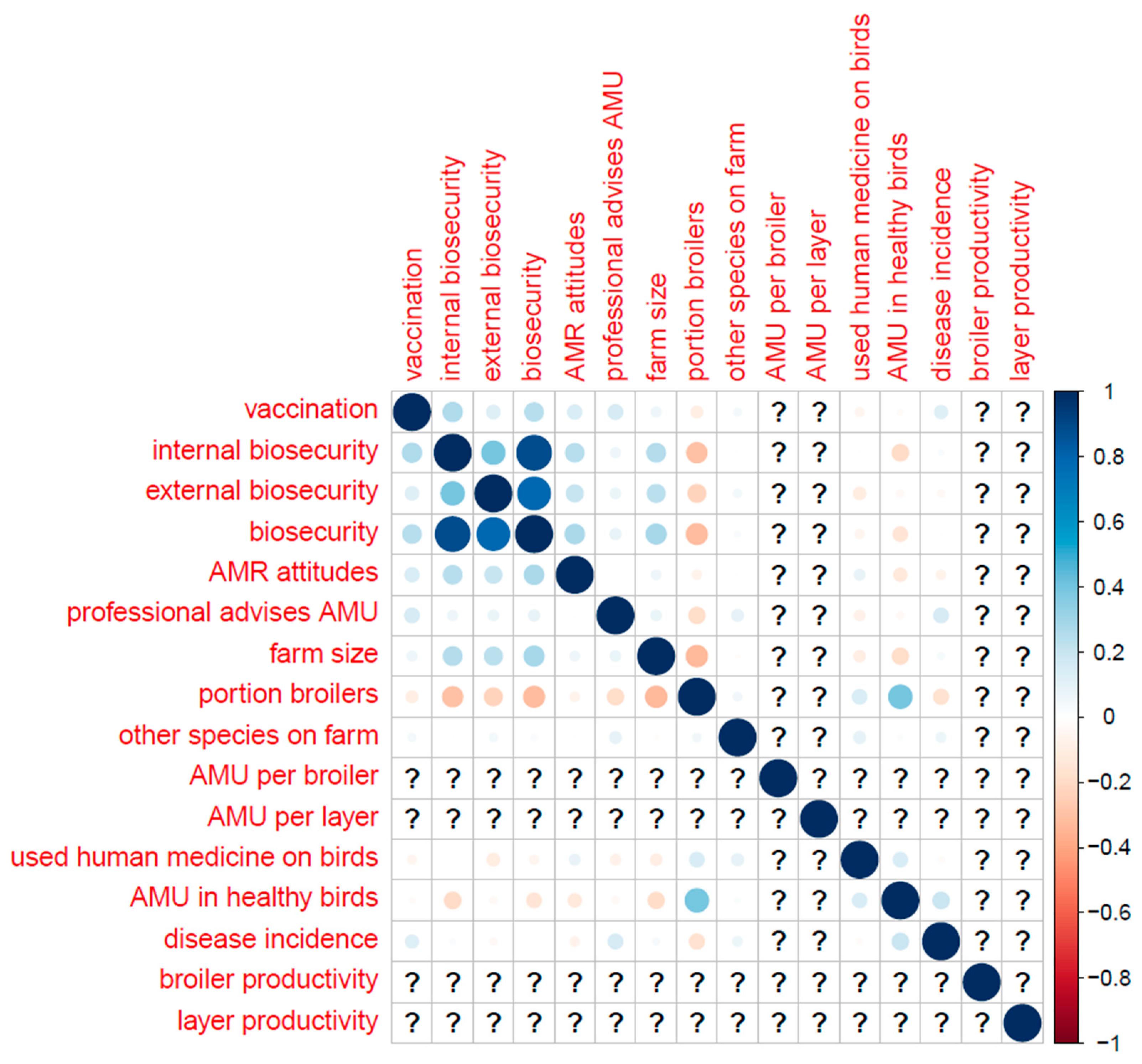

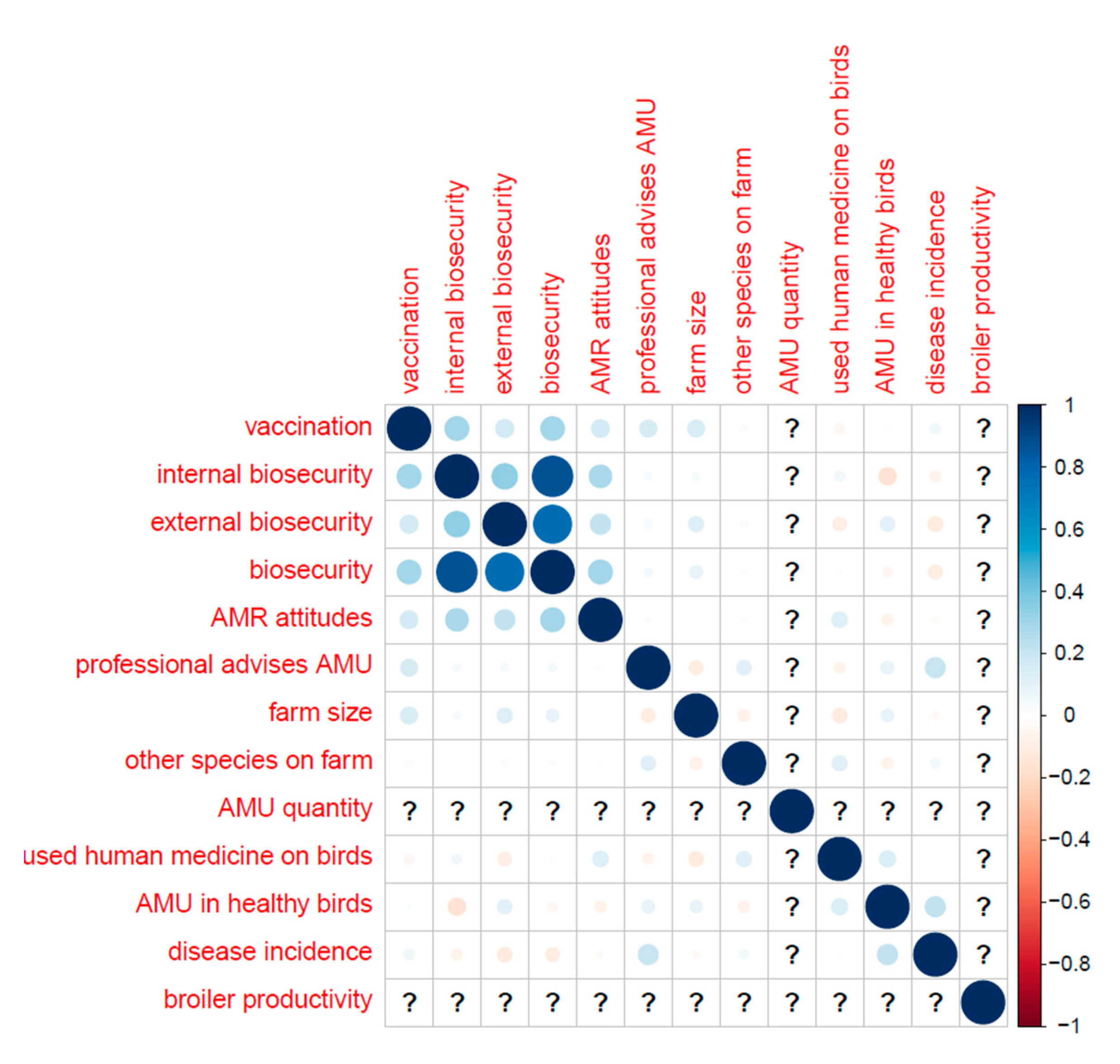

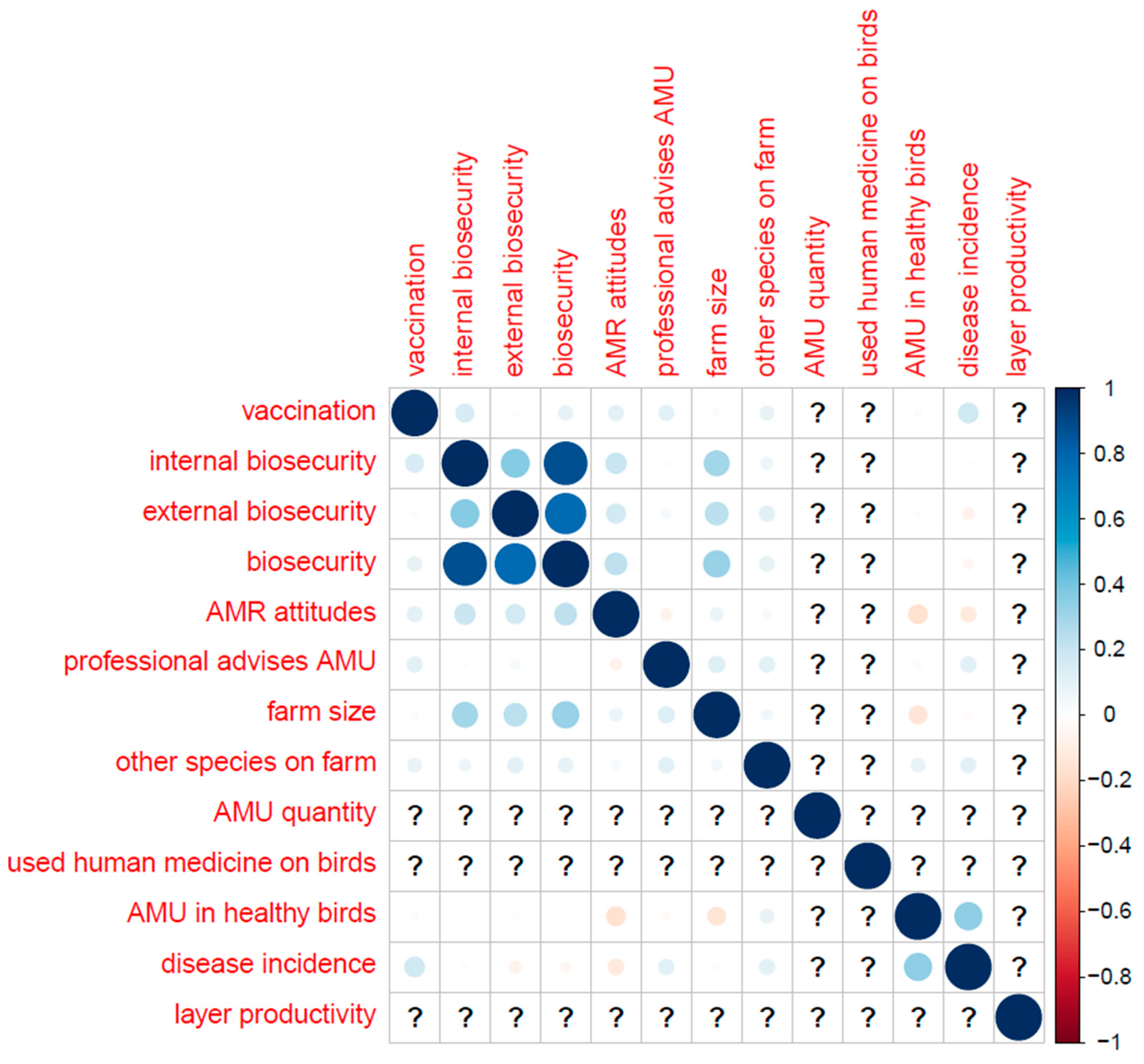

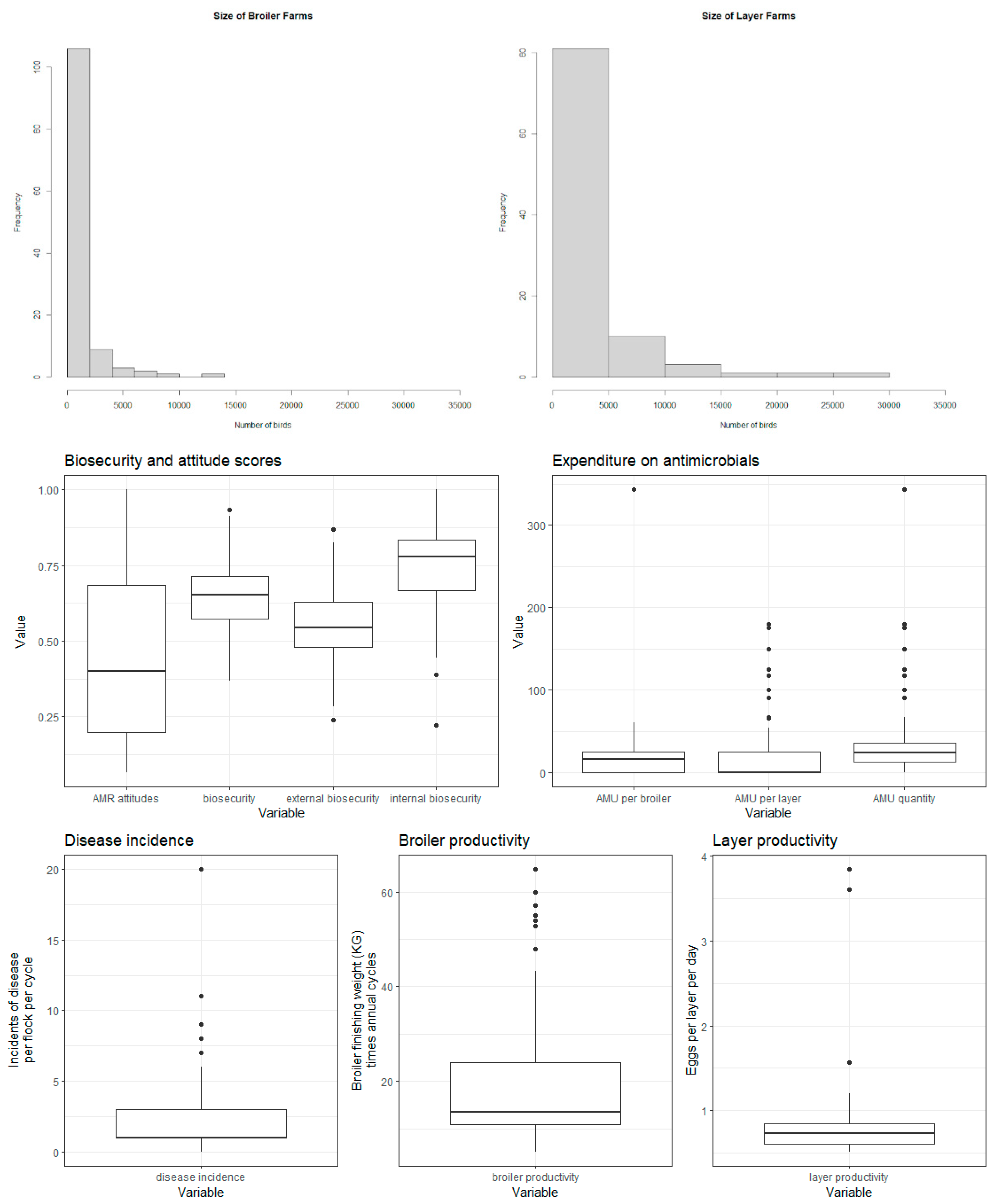

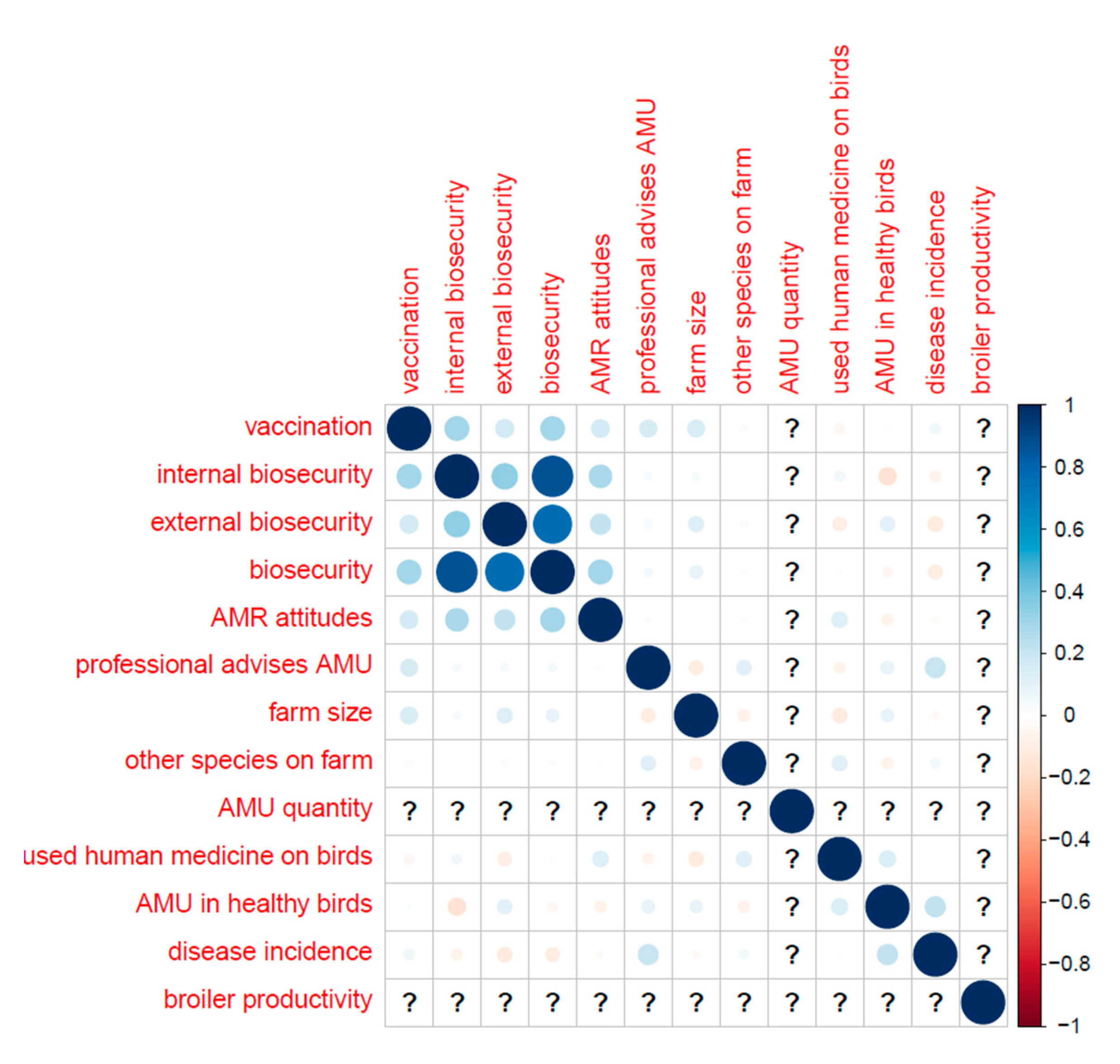

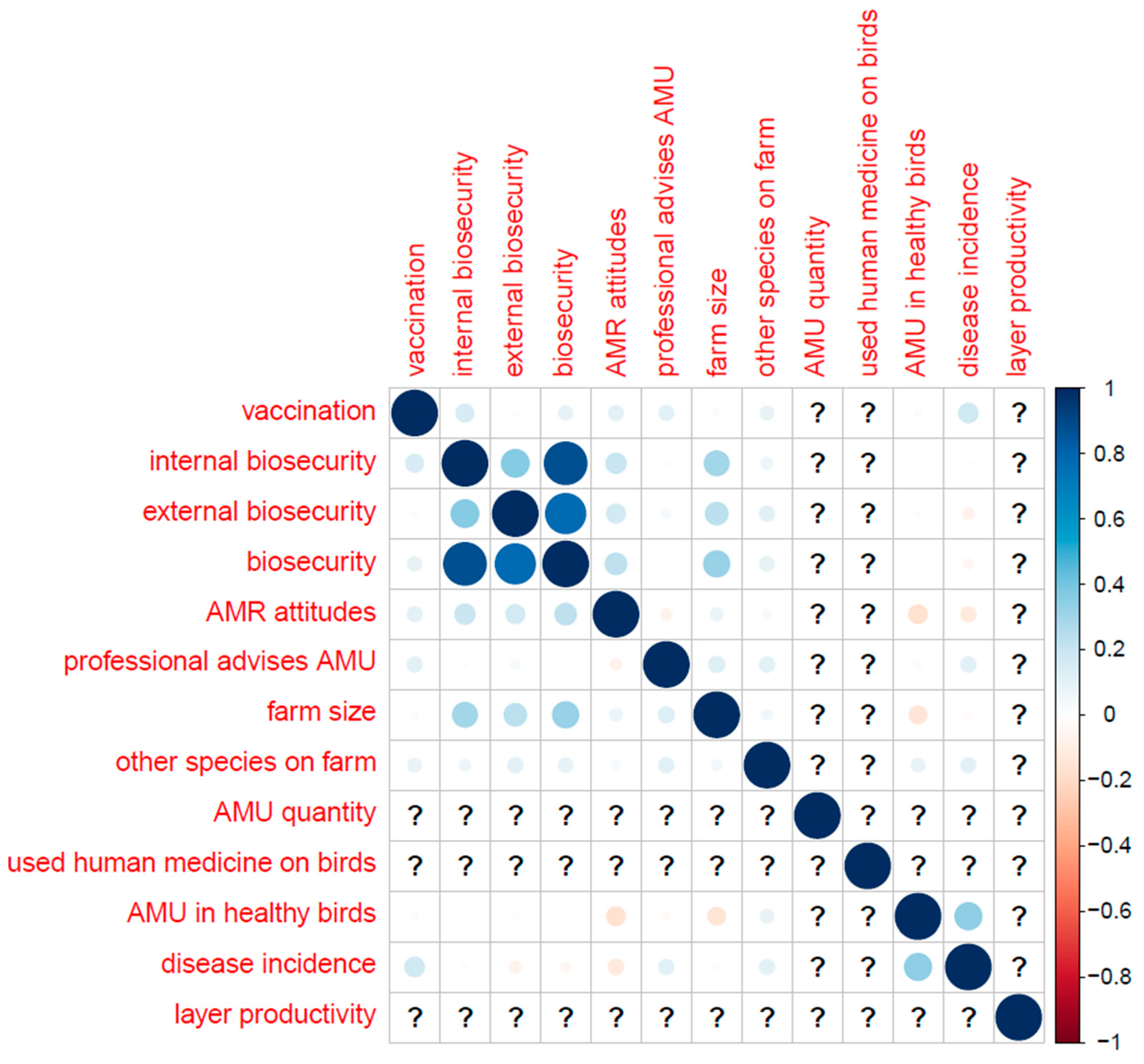

Table B (below) shows the distribution of categorical variables, and Figure B shows the distribution of continuous variables. Correlations (Pearson’s correlation coefficient) between key variables are displayed in

Appendix F.

Table B - summary statistics of categorical variables

Figure B - distribution of continuous variables.

2.2. Main Results

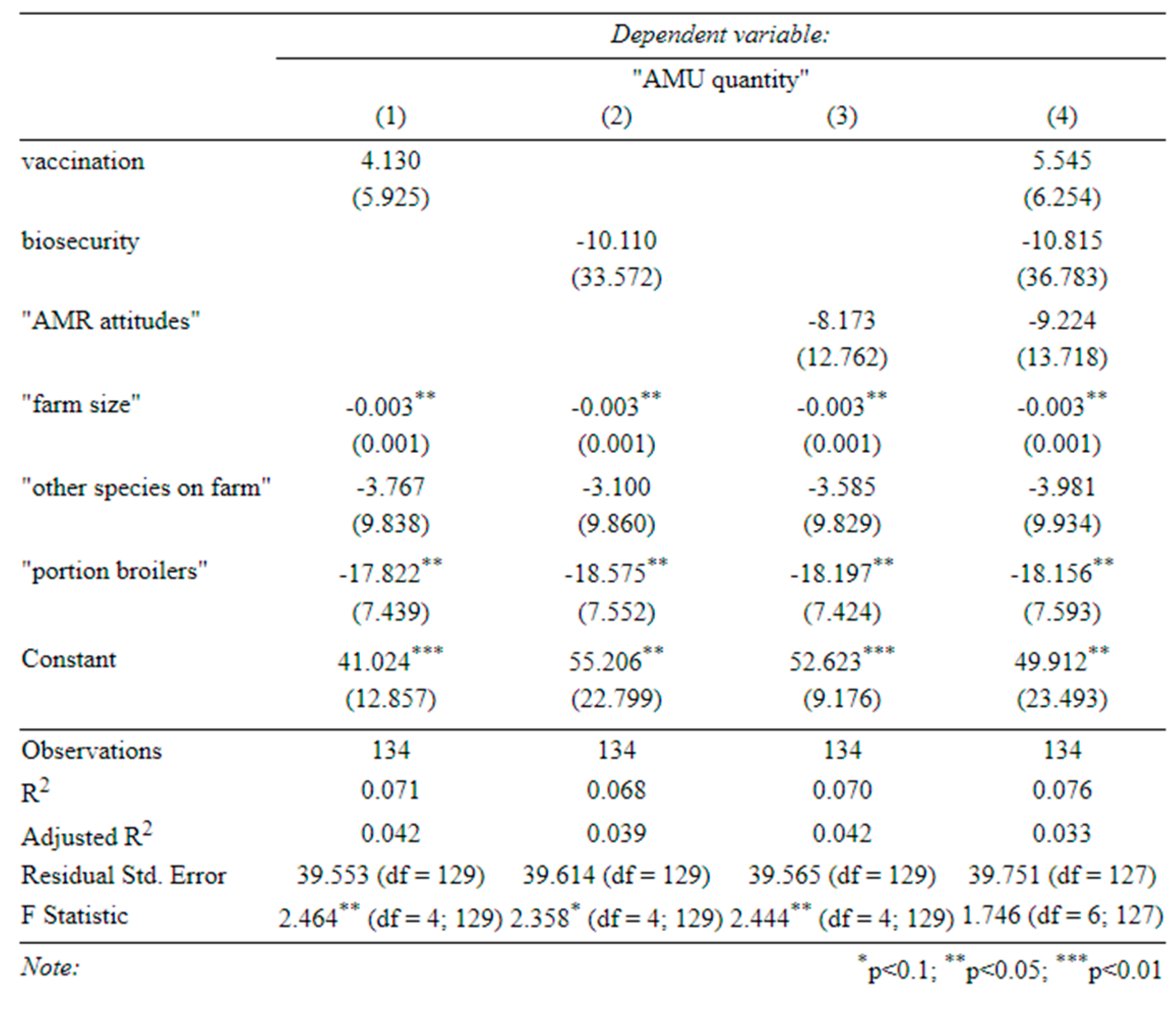

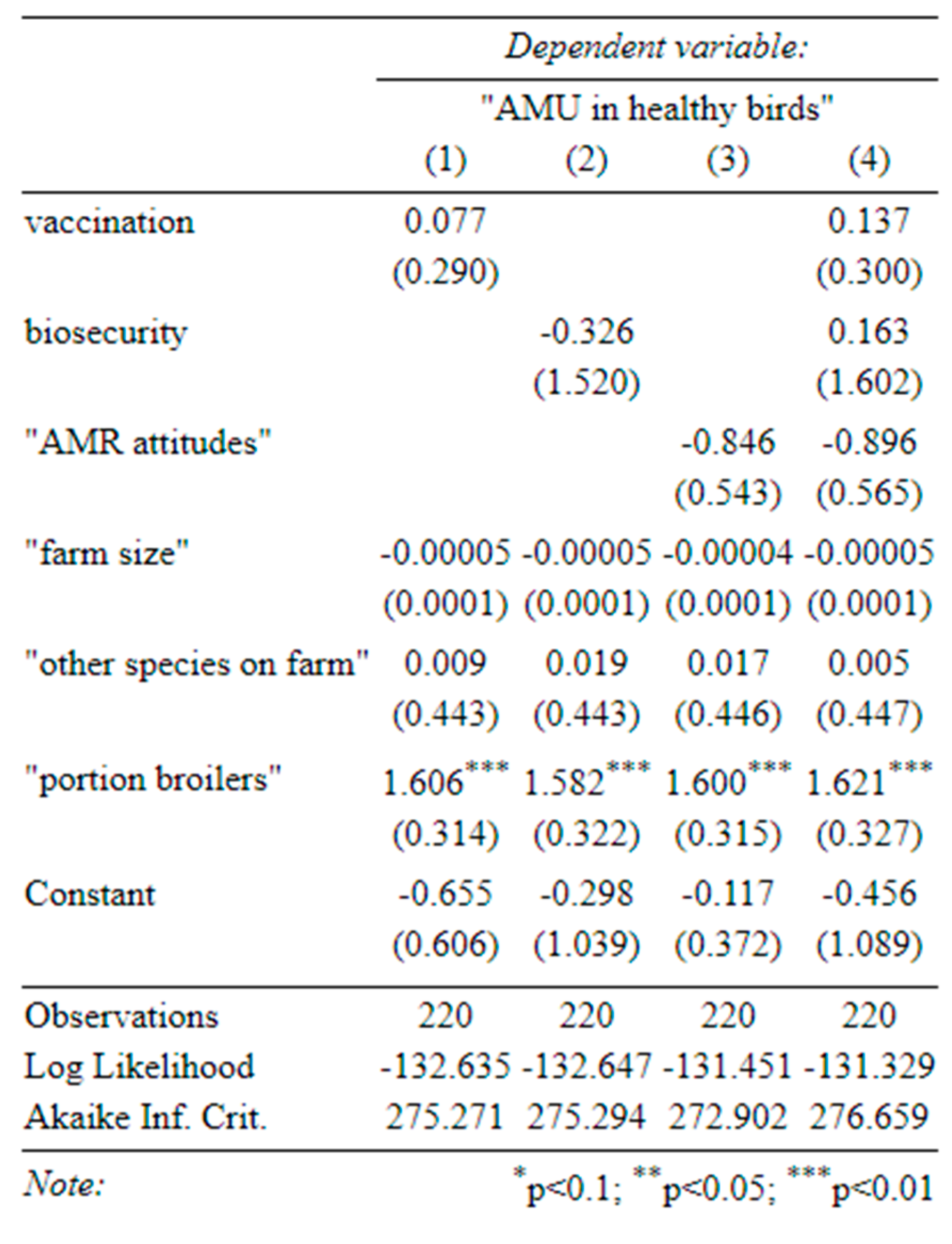

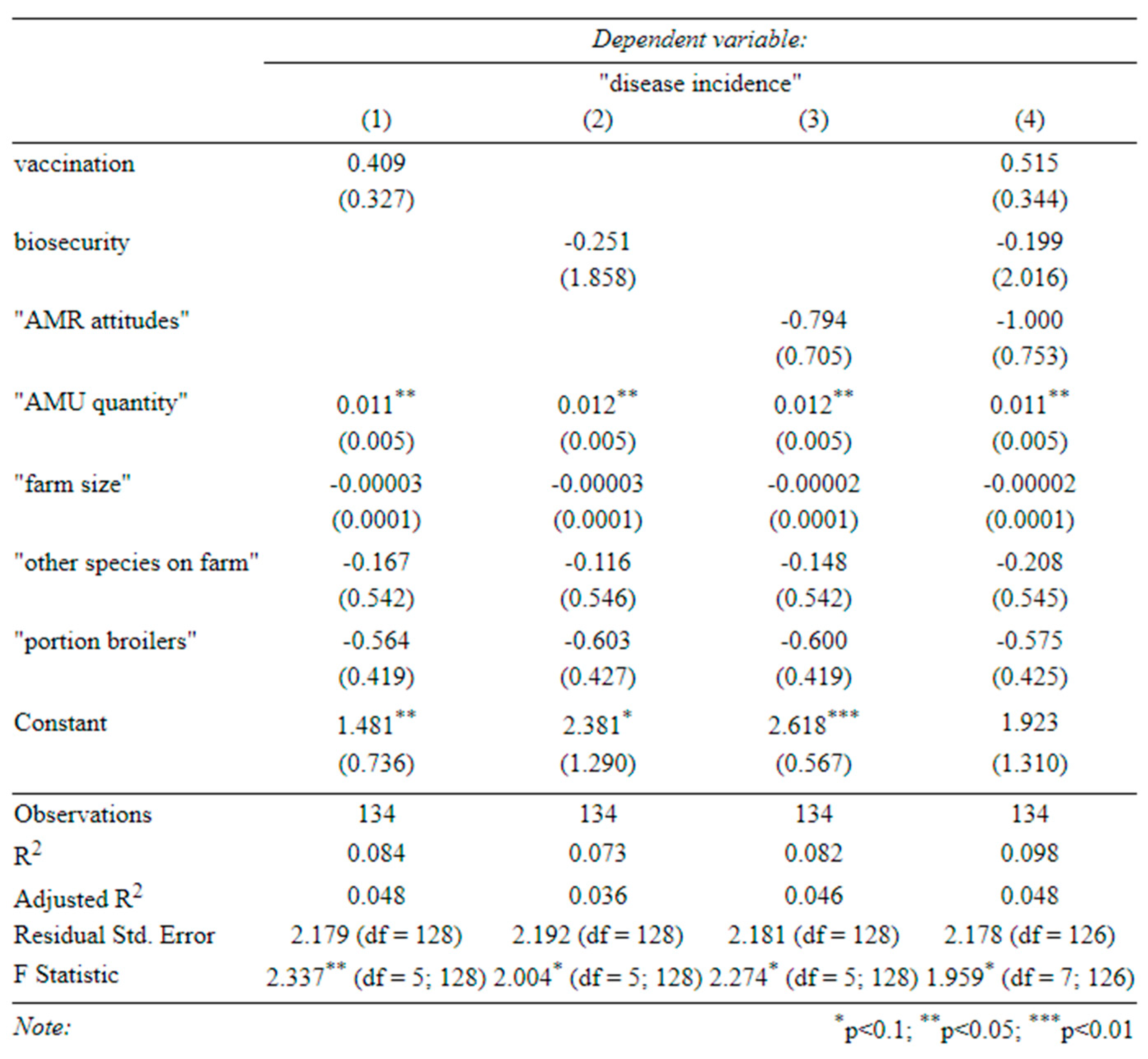

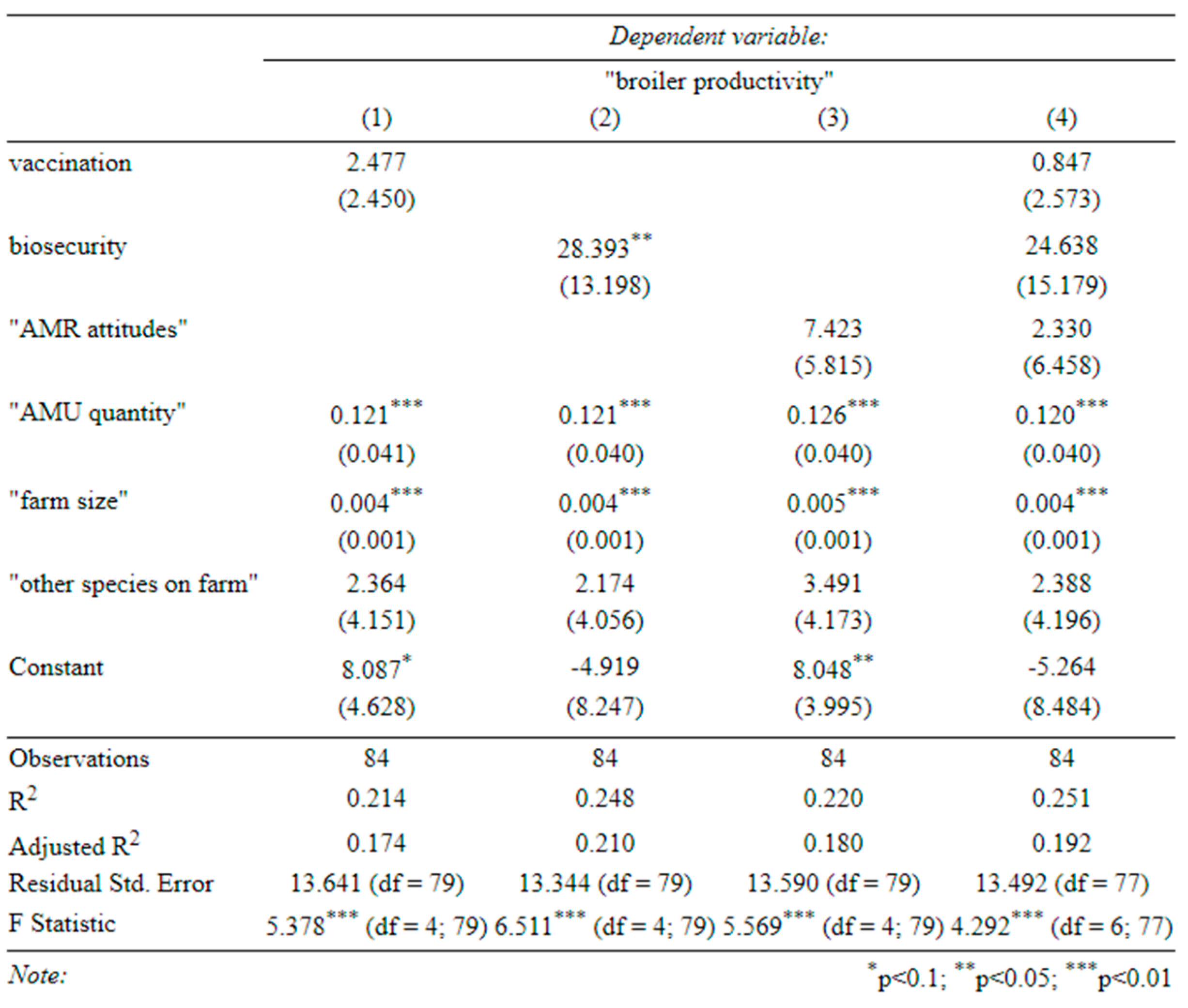

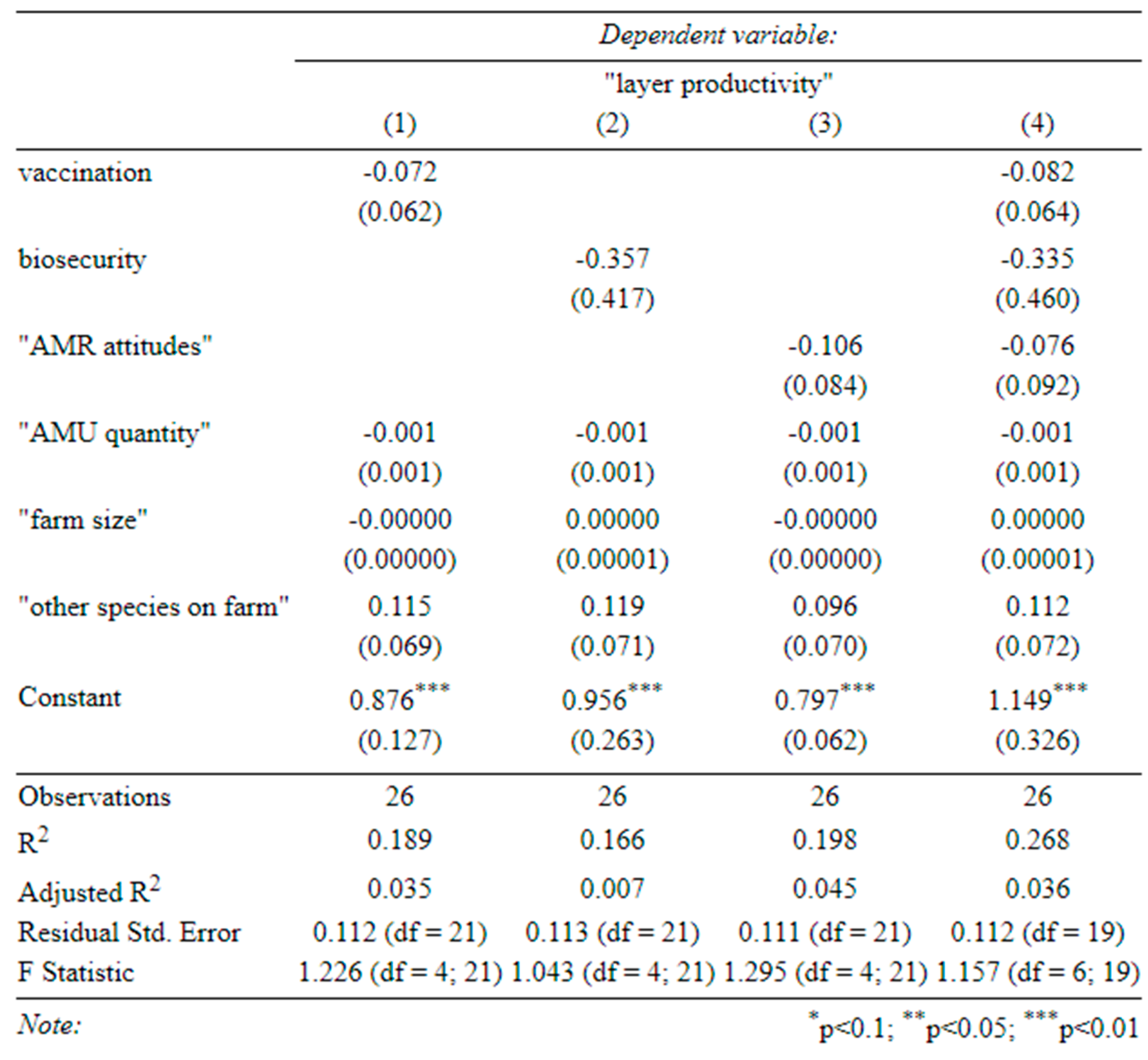

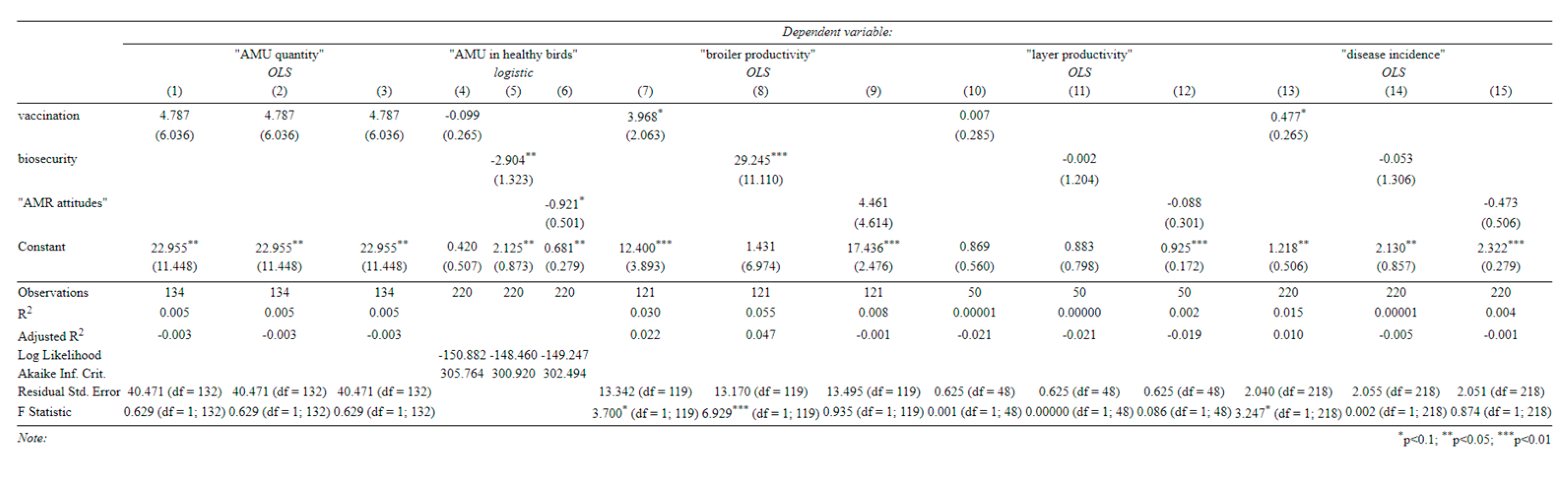

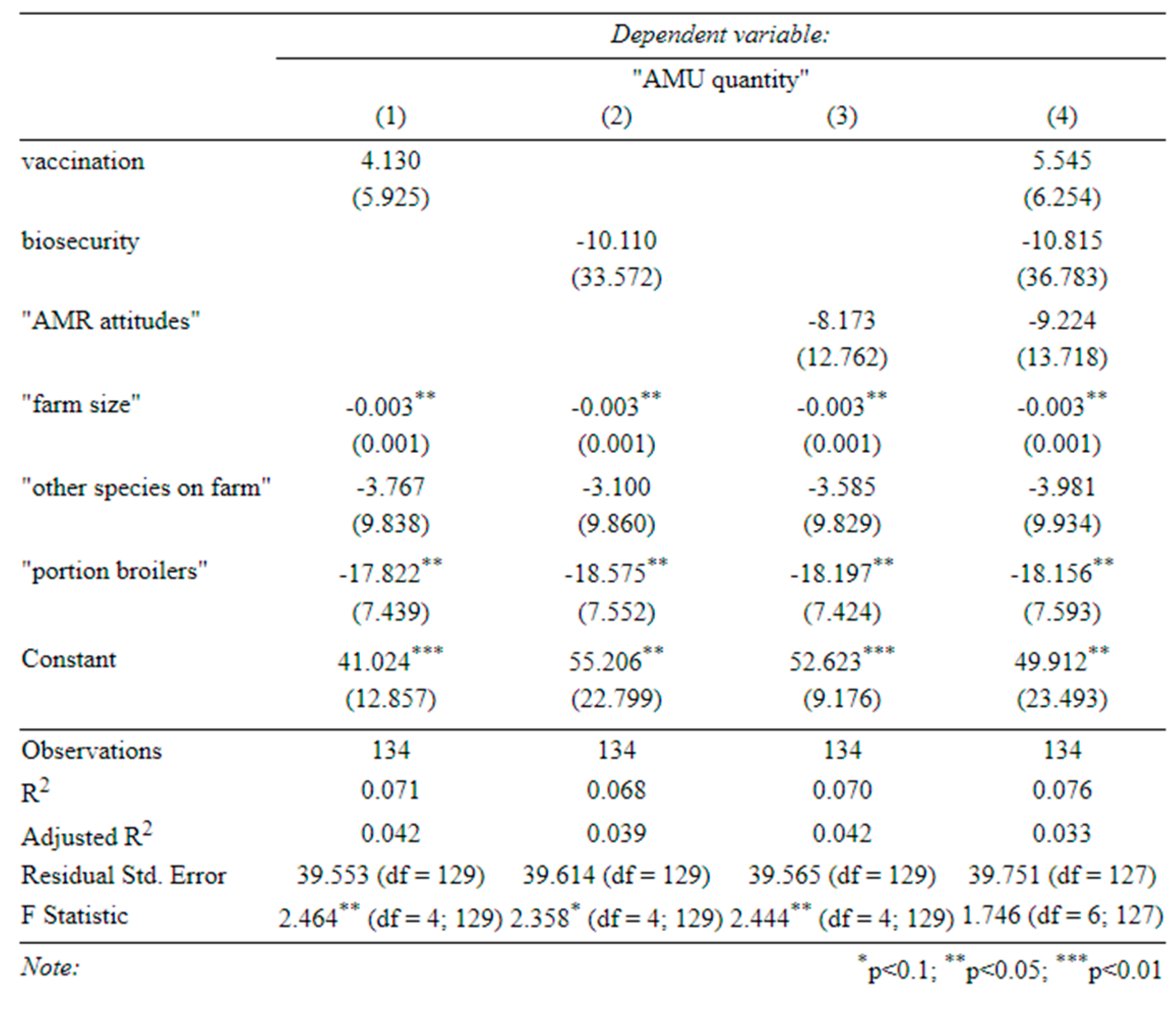

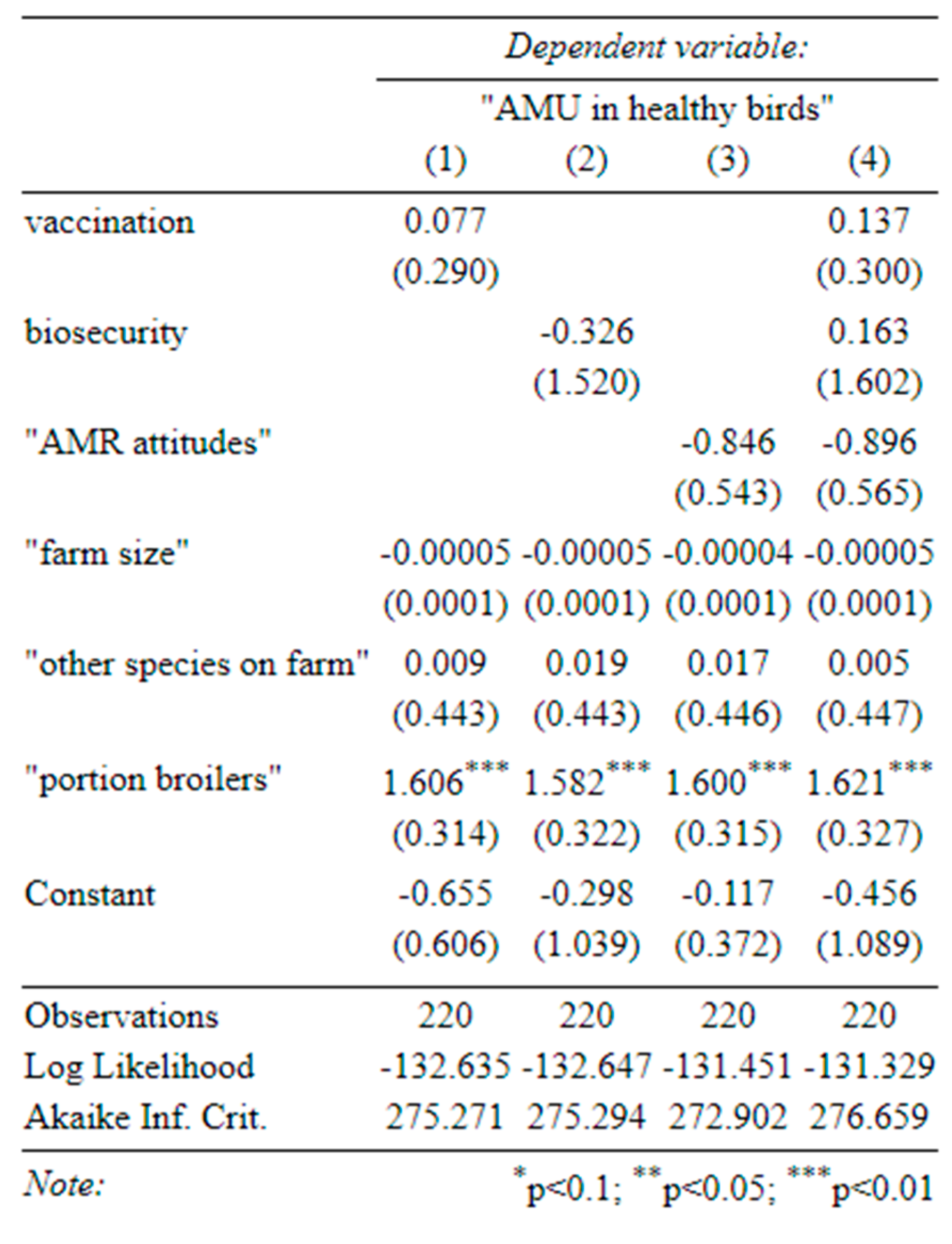

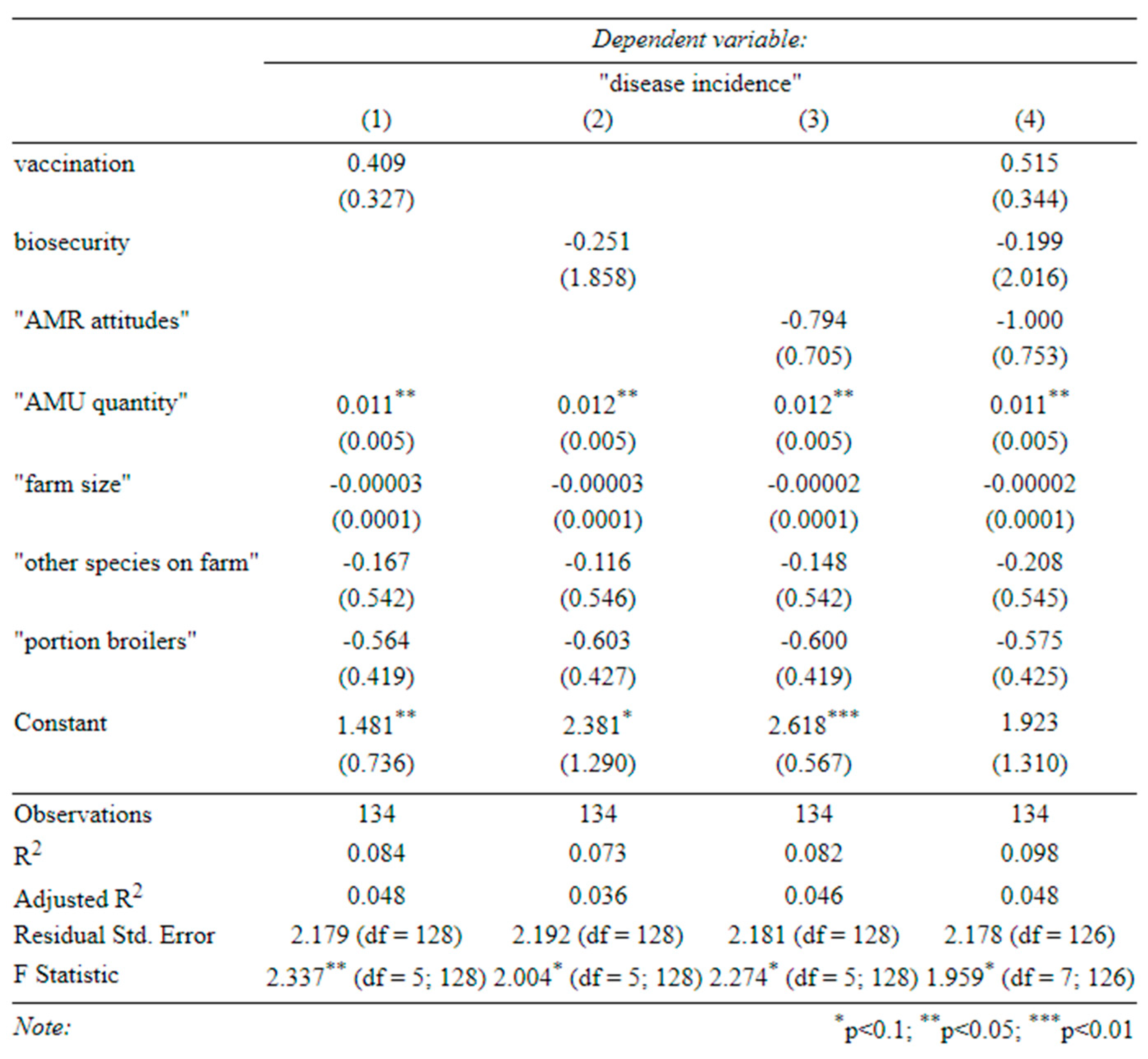

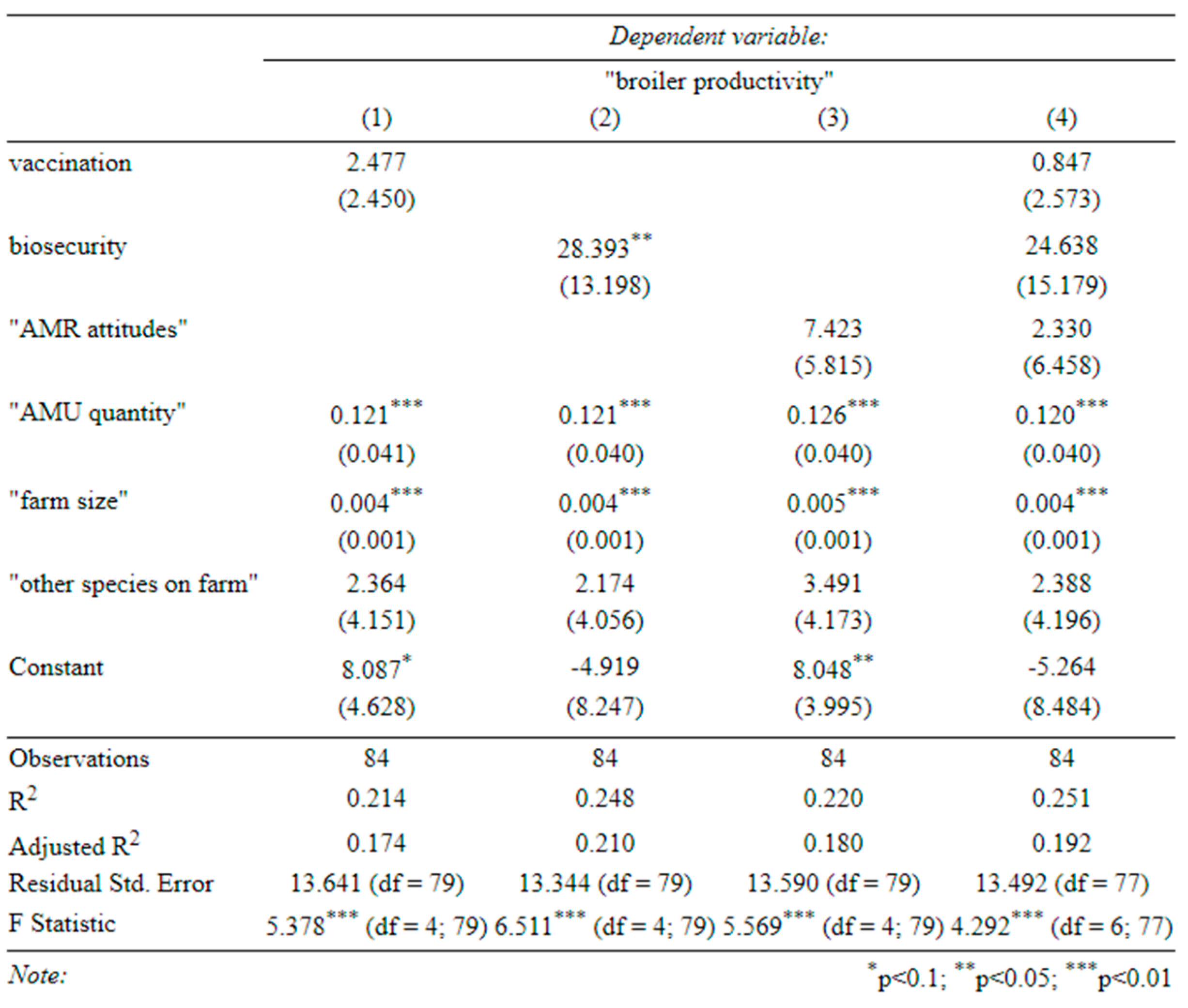

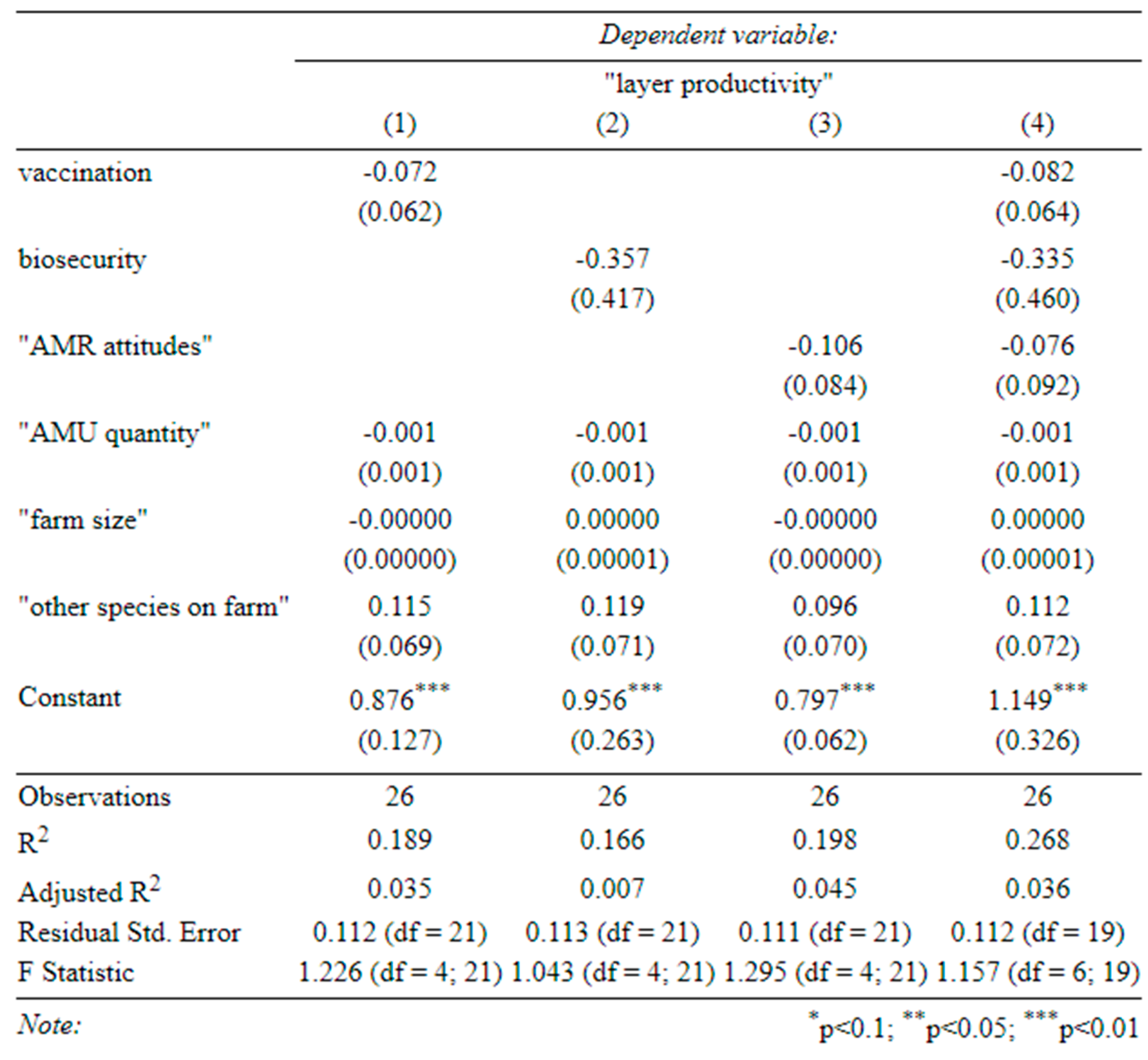

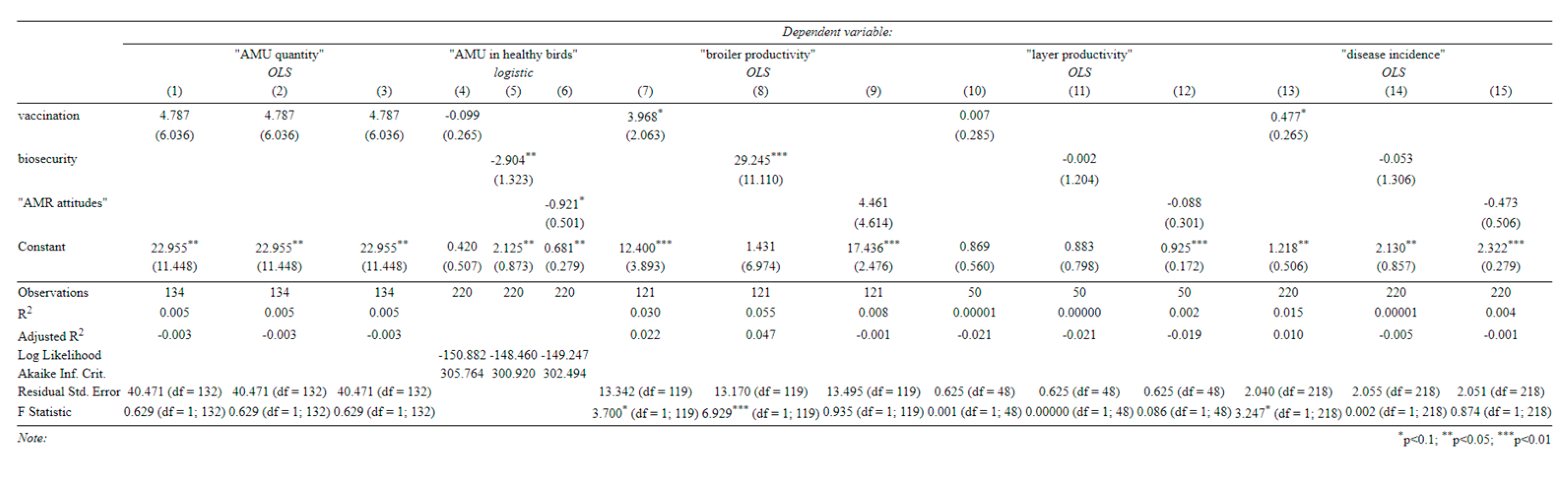

Table C (below) shows the results of our main regressions, where we look at the effect of our three main covariates (“biosecurity”, “AMR attitudes”, and “Vaccination”), on: the quantity of AMU (“AMU quantity”) (Table C-1), the likelihood of using antibiotics on healthy birds (“AMU in healthy birds”) (Table C-2), animal morbidity (“Disease incidence”) (Table C-3), and farm productivity (“broiler productivity” and “layer productivity”) (Table C-4 and C-5).

Table C-1-determinants of AMU quantity (1) effect of vaccination on AMU, (2) effect of biosecurity on AMU, (3) effect of attitudes on AMU, (4) effect of all three on AMU (standard errors in parentheses).

Table C-2-determinants of antibiotic use in healthy birds (1) effect of vaccination on antibiotic use in healthy birds, (2) effect of biosecurity on antibiotic use in healthy birds, (3) effect of attitudes on antibiotic use in healthy birds, (4) effect of all three on antibiotic use in healthy birds (standard errors in parentheses).

Table C-3-determinants of disease incidence (1) effect of vaccination on disease incidence, (2) effect of biosecurity on disease incidence, (3) effect of attitudes on disease incidence, (4) effect of all three on disease incidence (standard errors in parentheses).

Table C-4-determinants of productivity (broilers) (1) effect of vaccination on broiler productivity, (2) effect of biosecurity on broiler productivity, (3) effect of attitudes on broiler productivity, (4) effect of all three on broiler productivity (standard errors in parentheses).

Table C-5-determinants of productivity (layers) (1) effect of vaccination on layer productivity, (2) effect of biosecurity on layer productivity, (3) effect of attitudes on layer productivity, (4) effect of all three on layer productivity (standard errors in parentheses).

None of our covariates of interest significantly affected the quantity of AMU, regardless of whether they were included together or separately (Table C-1). In fact, farm size and production type were the only variables that significantly influenced this, with larger farms consistently using fewer antibiotics per bird (perhaps due to economies of scale) and broiler farms using less per cycle (although production cycles were much shorter).

In univariate specifications (

Appendix B), farmers with more ‘AMR-aware’ attitudes, and those with better biosecurity, appeared less likely to use antibiotics on healthy birds. However, there is little evidence to support the link with biosecurity in our main specifications (Table C-2). Here, AMR-aware attitudes remained negatively associated with use in healthy birds, but this relationship was not quite statistically significant (

p = 0.113 and

p = 0.120). Broiler farms were consistently more likely to use antibiotics in healthy birds, perhaps due to growth-promotion use.

Antibiotic use was consistently associated with a higher incidence of disease (Table C-3), as was our index of vaccination (in the univariate specification only). We speculate that this reflects endogeneity in two ways: (1) that vaccination and antibiotics may be used in response to disease outbreaks and (2) that farmers who are more aware of animal health are both more likely to report disease incidence and also more likely to vaccinate.

A larger farm size, greater use of antibiotics, and better biosecurity were associated with more productive broilers (Table C-4). In the univariate specifications (

Appendix B), better vaccination was also associated with higher broiler productivity. Although antibiotics seemed to increase broiler productivity, so did vaccination and biosecurity. Therefore, a reduction in AMU with a simultaneous improvement in biosecurity (and vaccination) could improve antibiotic stewardship on broiler farms without harming productivity. This does not seem to be the case for layer farms, where none of our covariates significantly predicted productivity (Table C-5).

2.3. Robustness

Following our main results, we regressed the quantity of AMU against each of the biosecurity measures individually, as opposed to the biosecurity index (“Biosecurity”) used elsewhere. Only four individual measures appeared to be significant, but they did not remain significant after adjusting for the false discovery rate or the familywise error rate.

After this, we used Heckman selection (19) to take account of farms which did not use antibiotics. Our covariates of interest had no significant effect, which is unsurprising given that only 13 farms (9.7%) out of 134 with data on antibiotic expenditure reported zero expenditure.

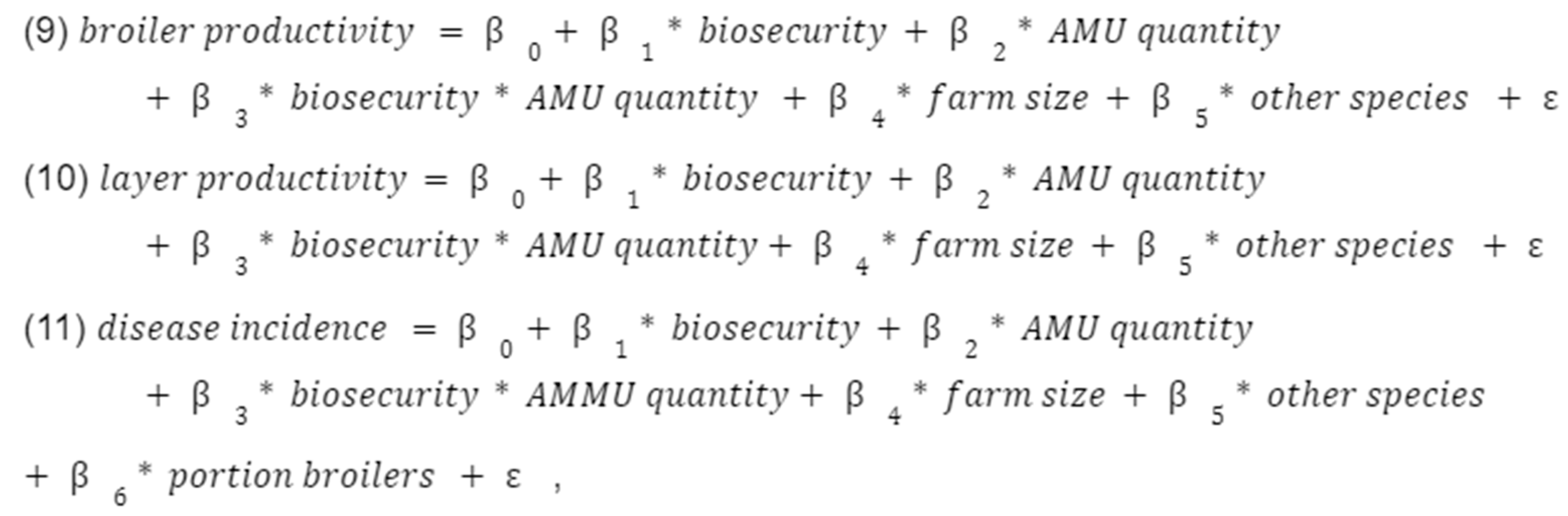

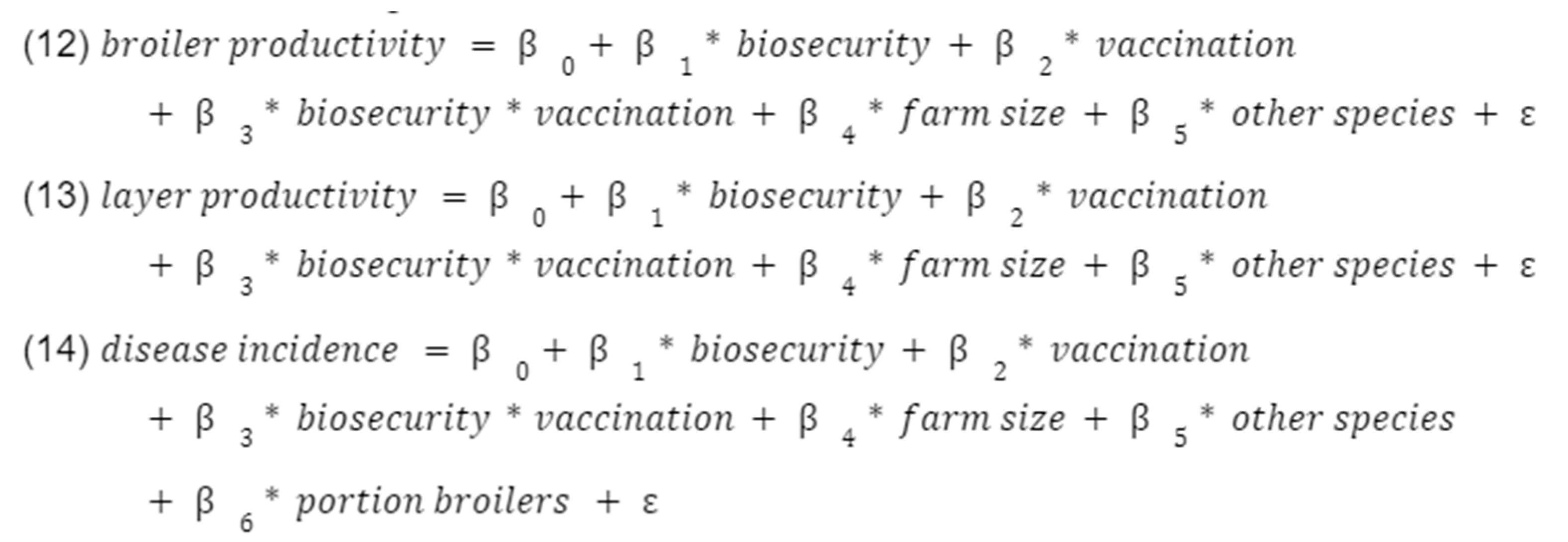

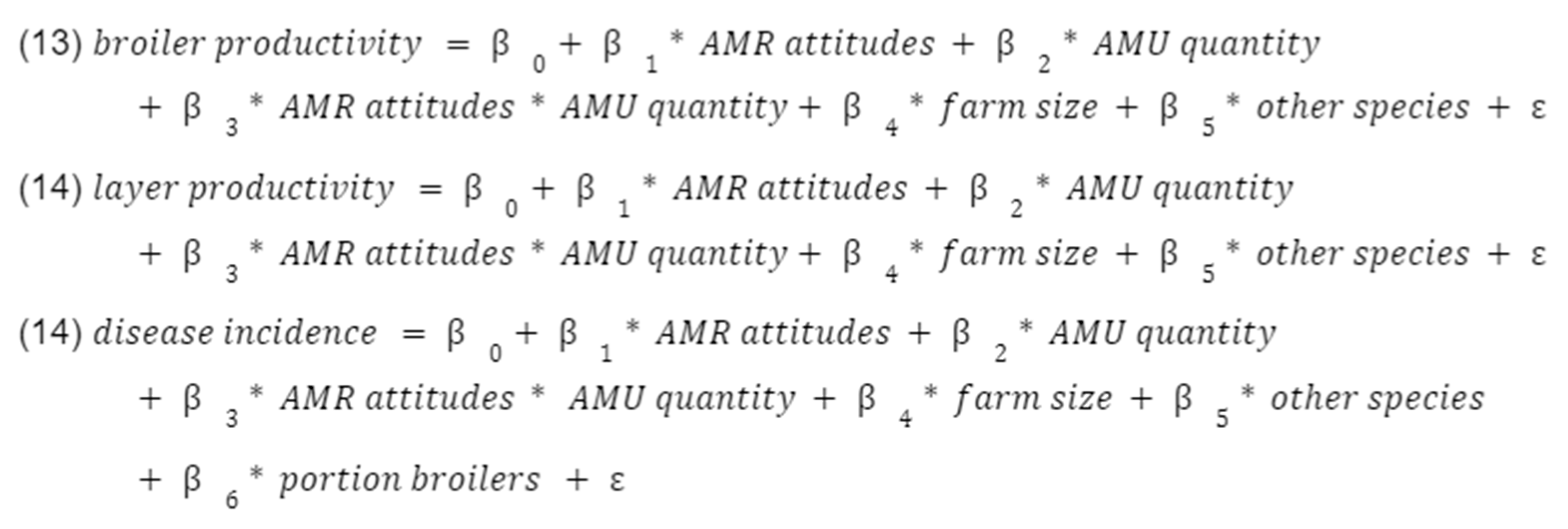

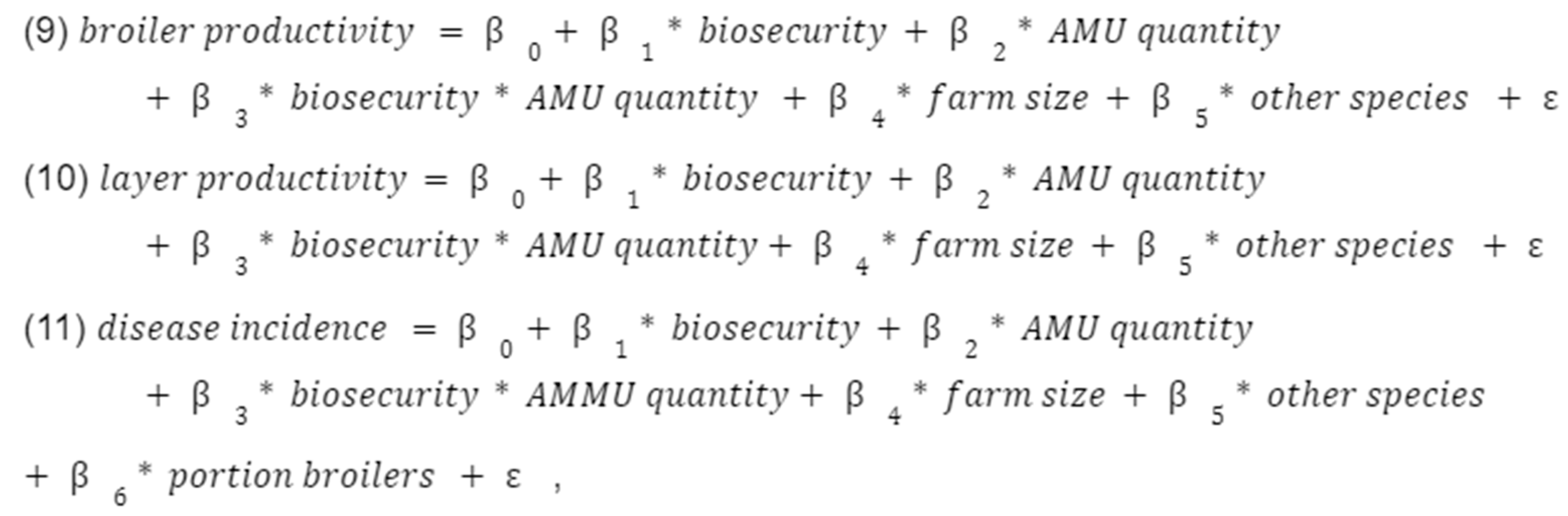

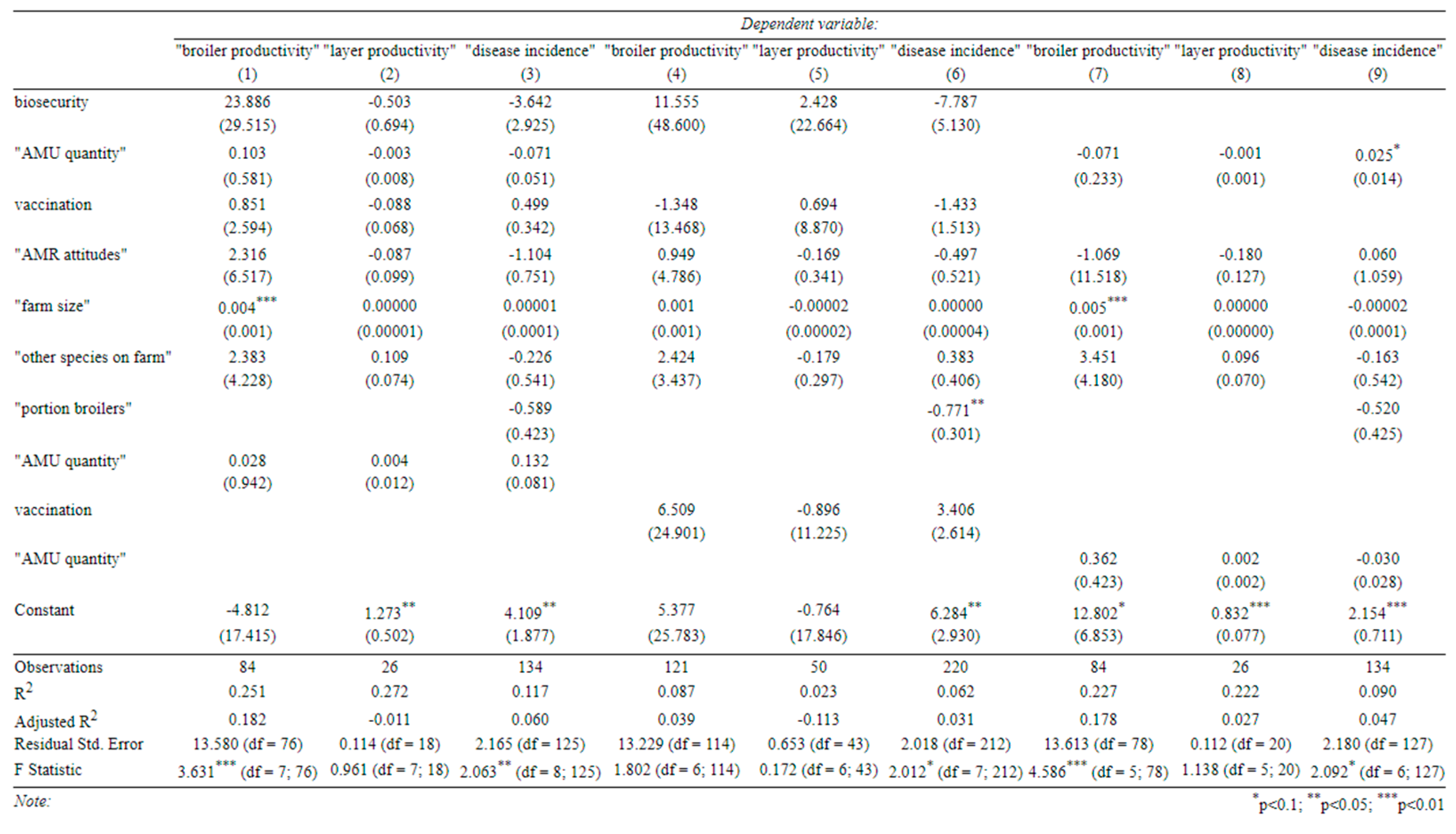

Finally, we examined three sub-hypotheses using interaction terms, all with disease incidence and productivity as our outcomes of interest (

Appendix C). (1) We interacted AMU with biosecurity to see if better biosecurity reduced the need for antibiotics in improving farm outcomes. (2) We interacted vaccination and biosecurity to see if these two measures are substitutes in terms of disease management. (3) We interacted AMR attitudes with AMU to see if better awareness of AMR increased the effectiveness of antibiotics as a disease management tool (following our original assumption that AMU would have a negative effect on disease incidence). However, none of the interaction terms were statistically significant.

3. Discussion

3.1. Overview of Findings

The characteristics and production type of farms were shown to be just as important to antibiotic use practices and farm outcomes as were our covariates of interest (biosecurity, vaccination and AMR attitudes). Larger farms consistently used fewer antibiotics per bird, and had more productive broilers. Broiler farms also seemed more likely to use antibiotics on healthy birds. This could be explained by the fact that broiler production cycles are short with farmers desiring quick turn over–farmers may wish to speed up production cycles using antibiotic growth promotors. Antibiotic use did seem to be associated with a greater productivity in broilers, but not in layers, suggesting some growth-promoting role.

Farmers with more ‘AMR-aware’ attitudes were less likely to use antibiotics on healthy birds in some specifications, which can be seen as indicative of more prudent AMU.

Vaccination was associated with more productive broilers in some specifications, and may be endogenous with disease incidence. Of our three covariates of interest, vaccination likely requires the most further investigation due to the low variation in vaccination practices among the farms surveyed. This also means that vaccination may have effects that we were not able to capture here.

Biosecurity, as measured by an index of various farm practices, was associated with more productive broilers. In univariate specifications, it was also associated with a lower likelihood of using antibiotics in healthy birds.

3.2. Comparison with Previous Work

Previous studies using the AMUSE tool have focused on characterising farm KAP: our addition of questions concerning productivity, biosecurity, vaccination and attitudes and knowledge of AMR greatly enhance the tool. This version of the survey (

Appendix A) can also be used in other contexts, and a replication of our results in other contexts would yield very useful comparisons.

While the effectiveness of antibiotic growth promoters is controversial, there are reasons to believe that low (sub-inhibitory) doses can promote livestock productivity (9). Our findings suggest that this may be the case, at least for semi-intensive broiler farms. This reaffirms the necessity of finding interventions which make antibiotic use reduction safer for farmers.

Weaker biosecurity infrastructure has also been associated with worse disease outcomes in other contexts (20). We do not replicate this result, but we do find a link to broiler productivity.

Lastly, vaccination of poultry is potentially a very effective tool for productivity enhancement and disease management (21). We found some suggestion of a productivity benefit for broilers, but did not replicate this finding consistently, likely reflecting the small sample size and very low variation in vaccination practices observed.

3.3. Meaning of Results and Implications for Future Research

Overall, there is some evidence that our three factors of interest (biosecurity, vaccination, and AMR attitudes) could be used to reduce AMU in poultry production, either by modulating AMU behaviours or by mitigating the potential productivity lost due to antibiotic withdrawal. Specifically, biosecurity may lower the incidence of disease and reduce the need for therapeutic antibiotic use, and biosecurity and vaccination may offset any productivity loss associated with antibiotic use reduction. In addition, awareness-raising and biosecurity improvements may reduce the use of antibiotics in healthy birds and improve antibiotic use prudence.

The findings will inform key interventions of the next multisectoral AMR monitoring action plan for Senegal (2023–2027). The current plan lasted 5 years and is ending in 2022. The overall objective of the plan is to provide an effective response, through an integrated “One Health” approach, to the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance. Specific objectives of the plan which these results can inform include: ensuring rational management and use of antimicrobials; informing and raising awareness on the issue of antimicrobial resistance; hygiene, infection prevention and control; and the rational use of antimicrobials in human, animal, and environmental health.

3.4. Limitations

Using observational survey data such as these poses a few difficulties. For one, there was considerable endogeneity between antibiotic use, vaccination, and disease prevalence, which made causality difficult to disentangle. We recommend the use of bigger datasets and annual followup to improve the statistical power of this type of study, as well as the use of instrumental variable techniques to mitigate this endogeneity. In particular, more data on the effectiveness of animal vaccination in semi-intensive poultry farms is necessary. Beyond this, a key next step should be to test these observational findings in the context of farm-level trials. Antibiotic use reduction (or replacement by non-antimicrobial feed additives) should be trialled alone, as well as in combination with interventions related to vaccination, biosecurity, and awareness-raising. Outcomes measured should include the incidence of disease, farm productivity, the use of antibiotics, the level of resistance in livestock animals, and the extent to which farmers feel safe and willing to withdraw antibiotics.

The relative homogeneity of farms in terms of practices (for example, near-universal antibiotic use and consistent vaccine coverage) not only contrasted stylised facts about the diversity and inconsistency of semi-intensive poultry farming practices(14) but also made statistical inference more difficult. This reaffirms the potential use of farm-level trials, in which these variables are intentionally altered, in future research.

There was also a very low R2 value across all regression specifications, likely reflecting the omission of key variables. A more detailed understanding of the relevant production system, for example using system dynamic models informed and parameterised in consultation with stakeholders (22), could help to collect more relevant data and to build more relevant models.

While we investigated the effect of awareness and attitudes from a statistical perspective, this is not a substitute for an in-depth investigation of these attitudes using mixed-methods research. Other upcoming research using this modified survey tool aims to answer that question in greater detail.

Finally, it must be noted that these findings alone may not be sufficient to facilitate changes to farming practices. The adoption of better biosecurity and vaccination practices are not a matter of individual ‘smart choices’, but are structural and nationwide issues that are heavily dependent on infrastructure and state support and are more effective when rolled out nationally (20,21): attitudes towards AMR can be thought of in the same way. Farmers moving towards more intensified production systems are exposed to novel challenges and require appropriate state support (14). Semi-intensive farmers often exist in a state of financial precarity and may require systems of financial support such as insurance in order to feel safe altering their practices. Small- and medium-scale farmers have complex upstream and downstream relationships with actors such as suppliers and creditors (16). Farmers must be seen as a part of this network, rather than as individual actors, and stakeholders from across this system must be meaningfully consulted in the formulation of future research and interventions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Aims, Data Collection Methods, and Setting

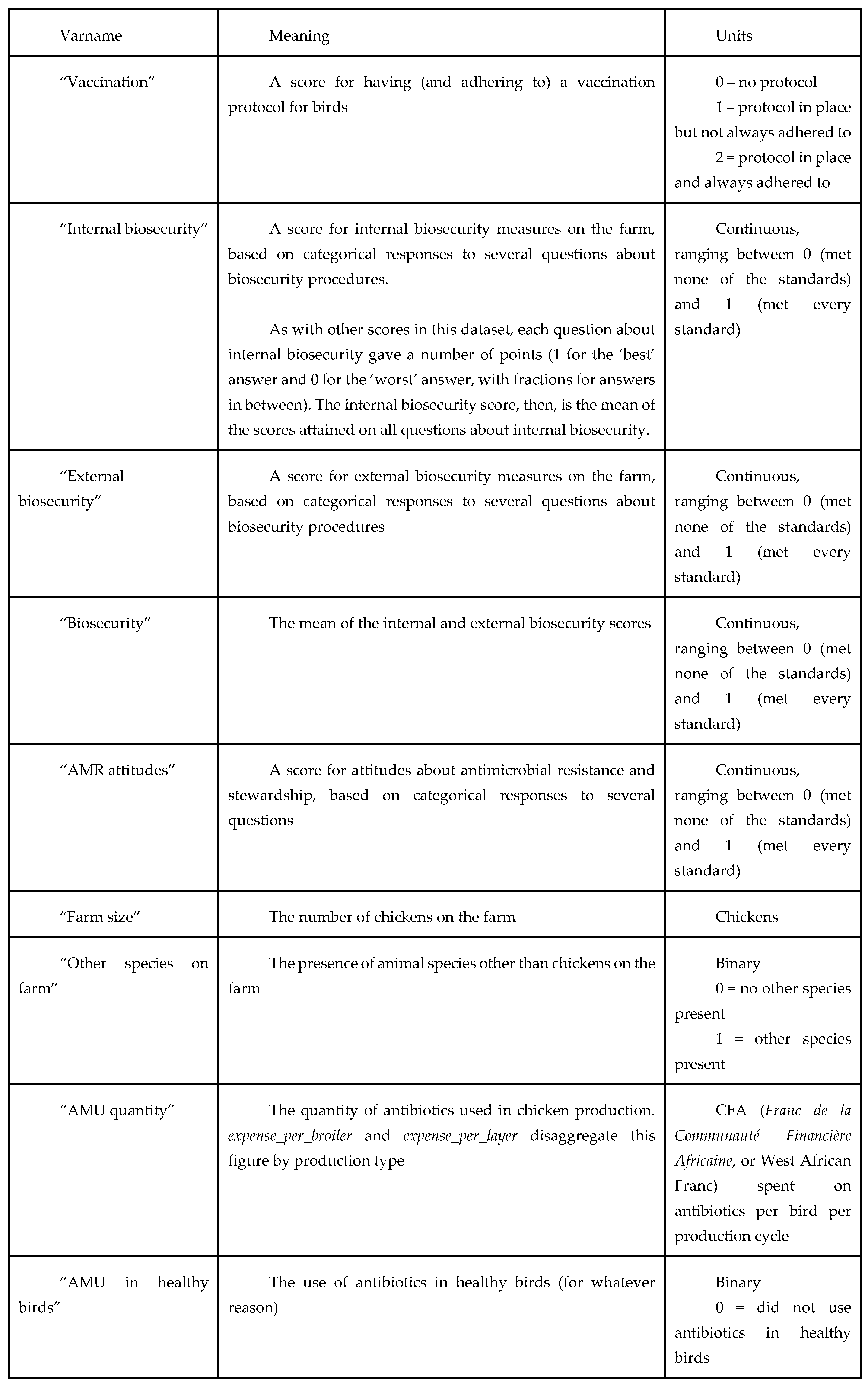

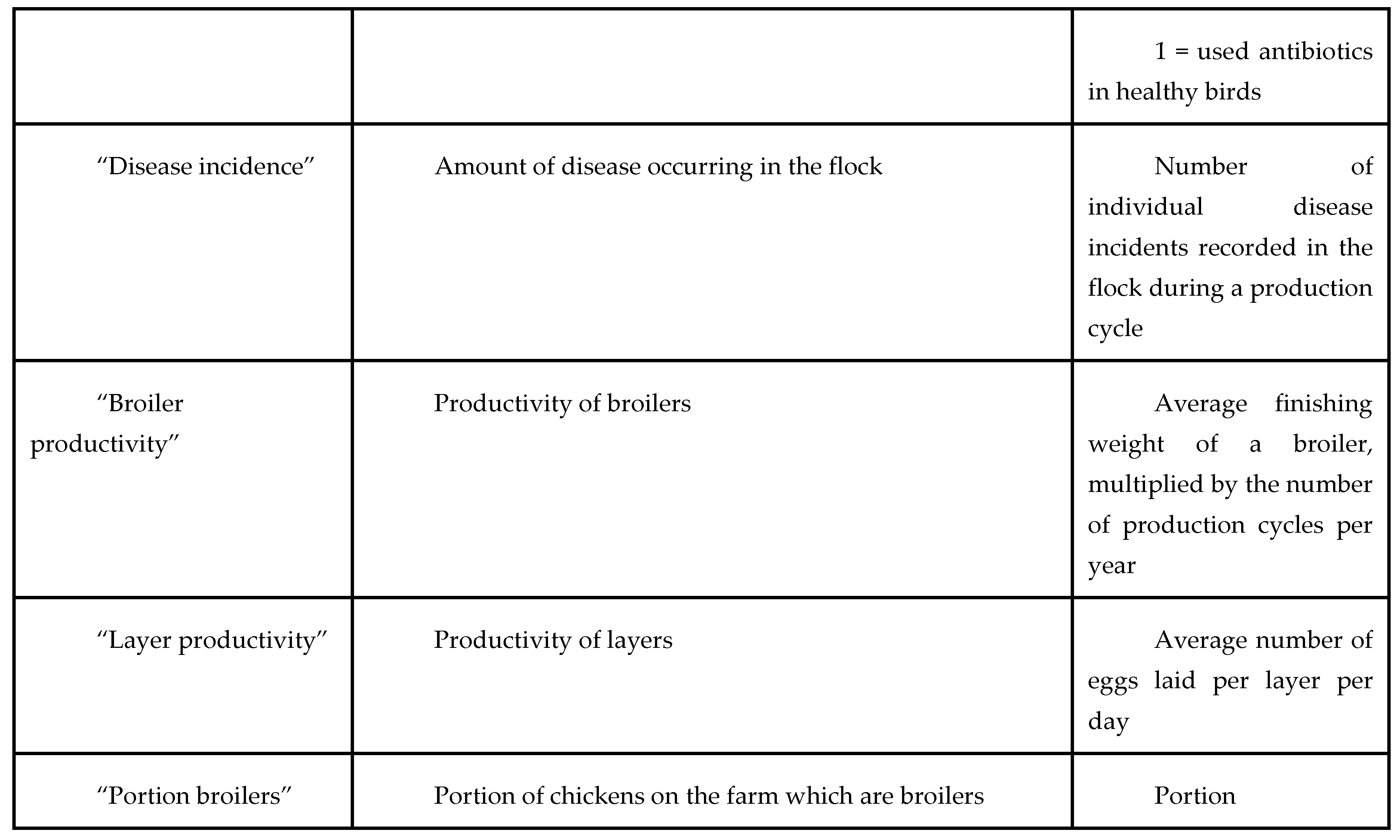

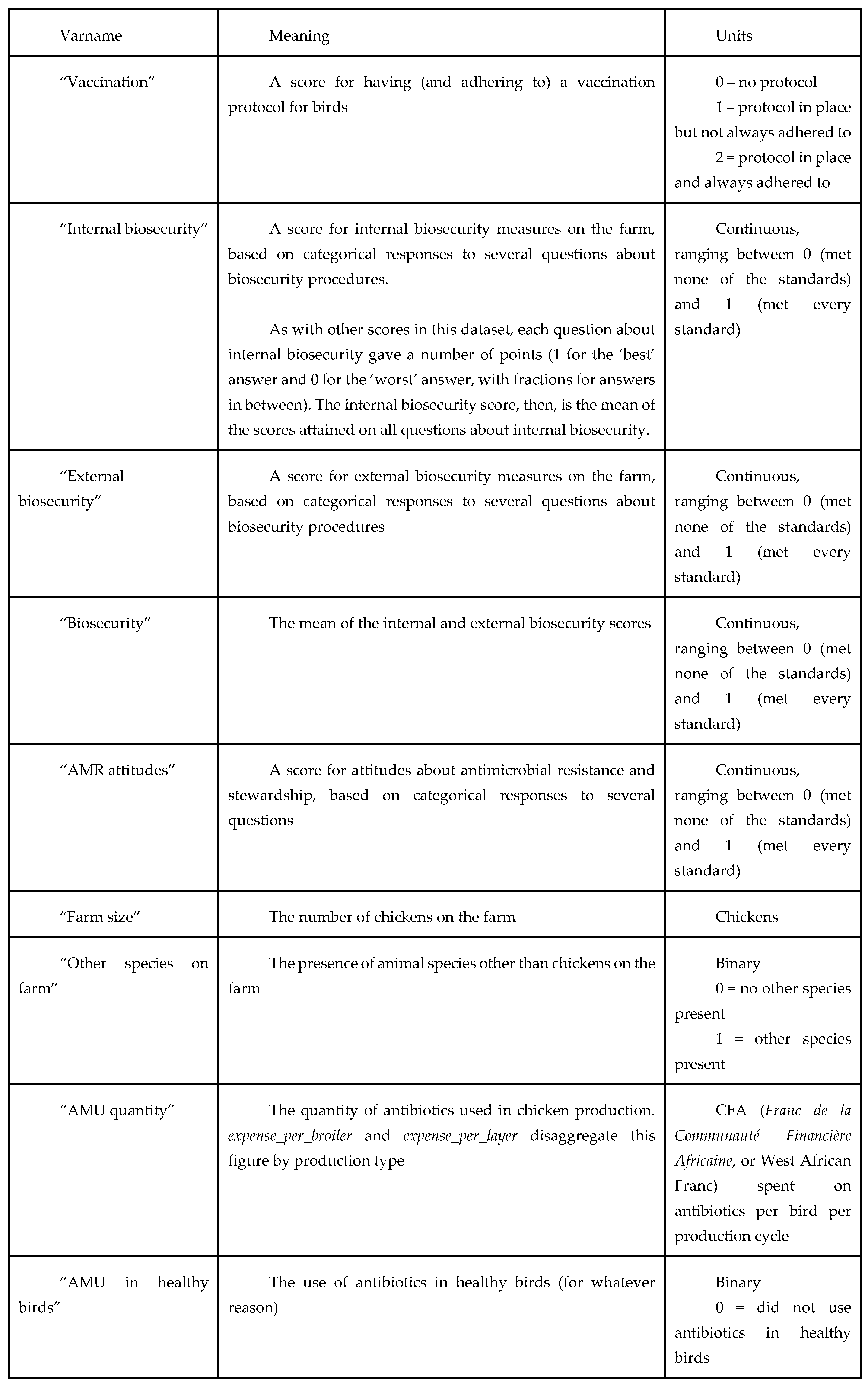

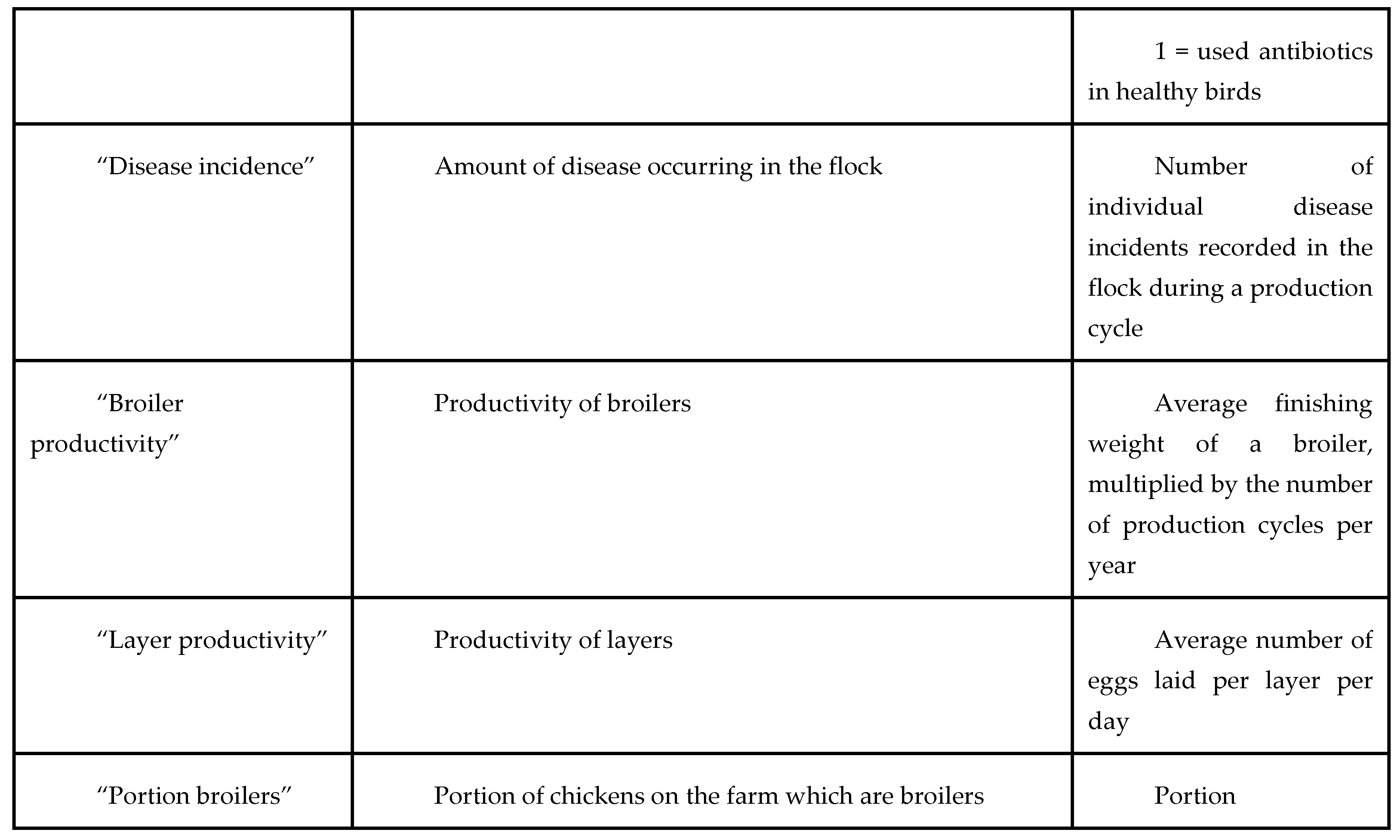

The data used in this study came from a modified version of the AMUSE survey tool, which is used to explore farm characteristics and AMR KAP in livestock farms (18). The original AMUSE tool has been used for descriptive purposes in Senegal as well as in other country settings, and our adapted version was expanded to include more measures of farm productivity, antibiotic use quantity, antibiotic use prudence, vaccination of livestock, AMR knowledge and attitudes, and on-farm biosecurity practices. ‘Prudence’ in this study refers to the use/non-use of antibiotics intended for human use in chickens, and the use/non-use of antibiotics in healthy birds. Also of relevance is the effect that these variables have on farm productivity and disease incidence in chickens. Data were cleaned and answers from sets of questions were compiled into metrics and indices for easier analysis (Table A).

Table A – variable glossary.

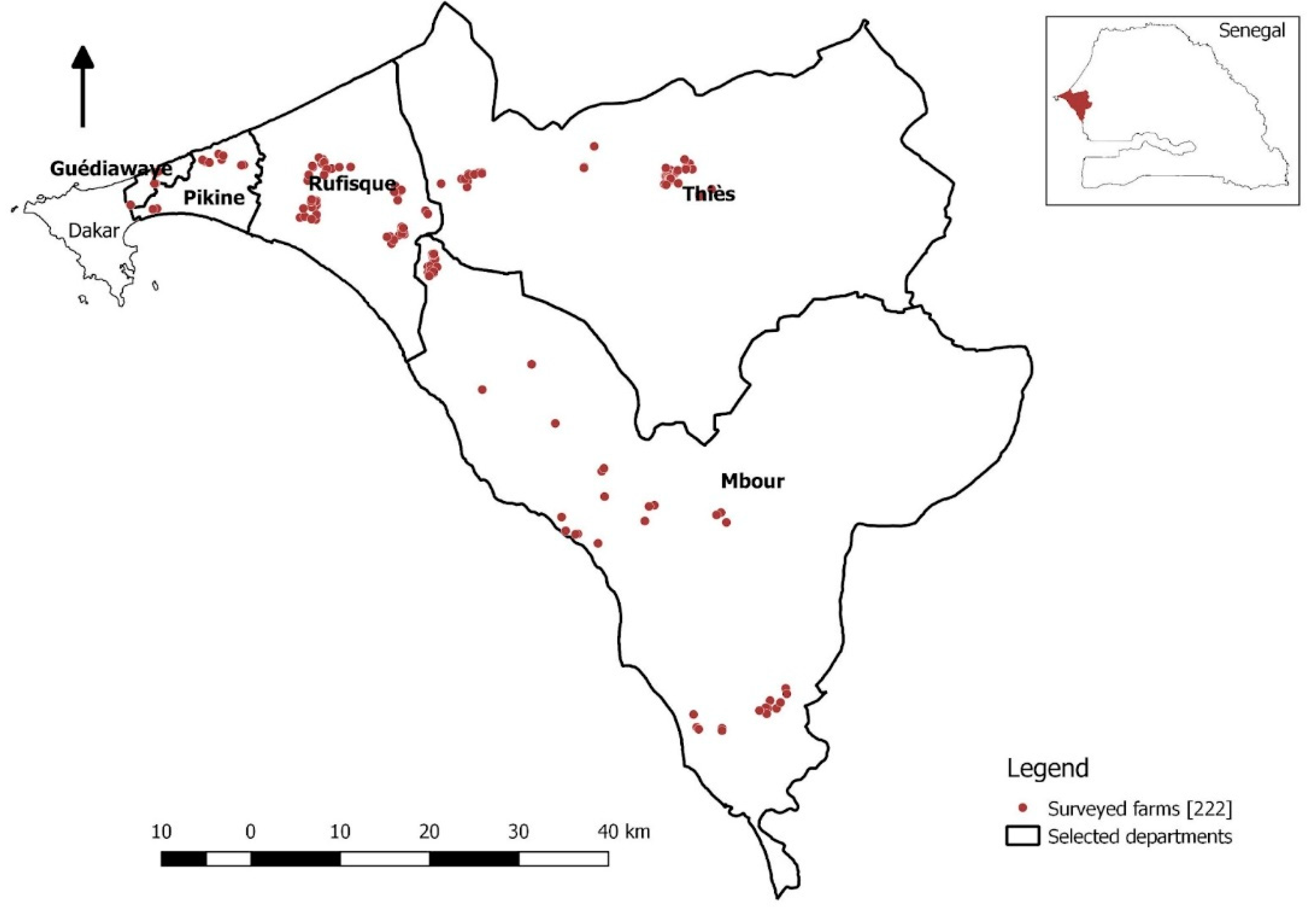

The locations of the farms surveyed are detailed in Figure A (below). Data collection took place from February to September 2022. A snowball sampling method was used to select farms. This method was chosen because a national database of poultry producers has not yet been compiled, making other sampling methods prohibitively difficult. A representative from each farm was interviewed for an average of one hour per farm. Four people in total were responsible for data collection, divided into two pairs, each composed of a veterinary doctoral student and a member of the Veterinary Service Division (DSV) of Dakar or Thiès, sometimes with the addition of a livestock technician to act as a guide and interlocutor. Data were collected electronically on smartphones using the Open Data Kit (ODK) platform.

Figure A – map of the farms surveyed.

The full set of survey questions used can be found in

Appendix A. Ethical approval can be found in

Appendix D and a (translated) copy of the informed consent form used for the study can be found in

Appendix E. Being an observational study, this paper conforms to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist (23).

4.2. Variables Used

We first present descriptive statistics, and then use regression analysis to look at the association between our three variables of interest on the following outcomes (both univariate and controlling for farm characteristics): quantity of AMU (measured by expenditure per bird), the use of antibiotics on healthy birds, farm productivity (meat and egg production), and the incidence of disease. Table A (below) details the variable names used throughout this paper, and outlines how variables were derived where relevant.

4.3. Main Statistical Methods

All statistical analyses were carried out using R version 4.1.2 (24) via RStudio build 554 (25). Key packages used include Stargazer (26), Tidyverse (27), ggplot2 (28), Corrplot (29), and dplyr (30). Model specifications were not chosen based on explanatory power (e.g., AIC or BIC) but were pre-specified in the pre-analysis plan based on theory. This is because we wanted to test specific hypotheses about our chosen variables rather than simply finding the model with the greatest explanatory power. Alternative specifications were explored during robustness testing.

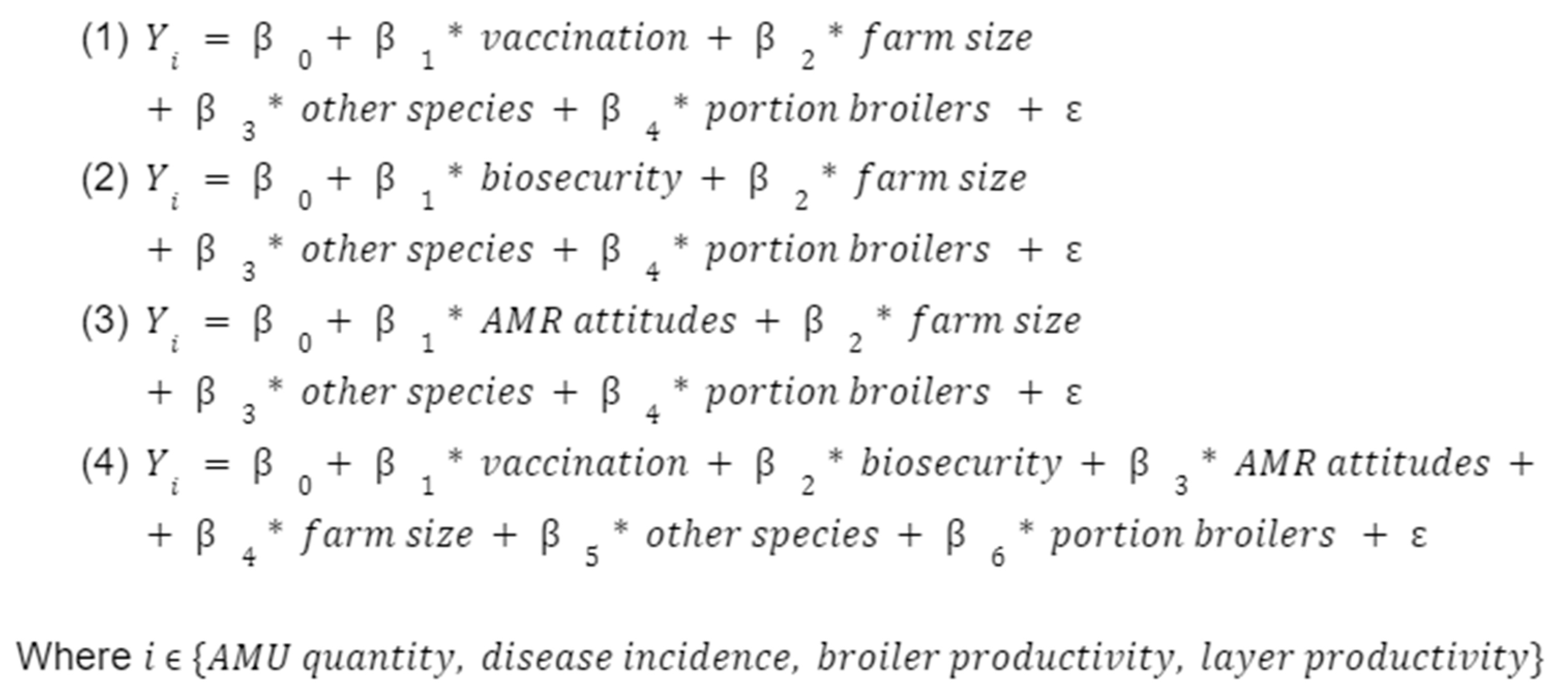

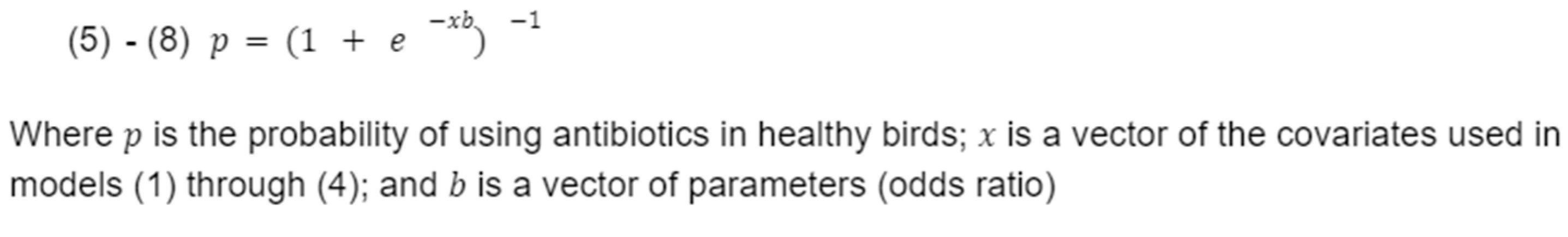

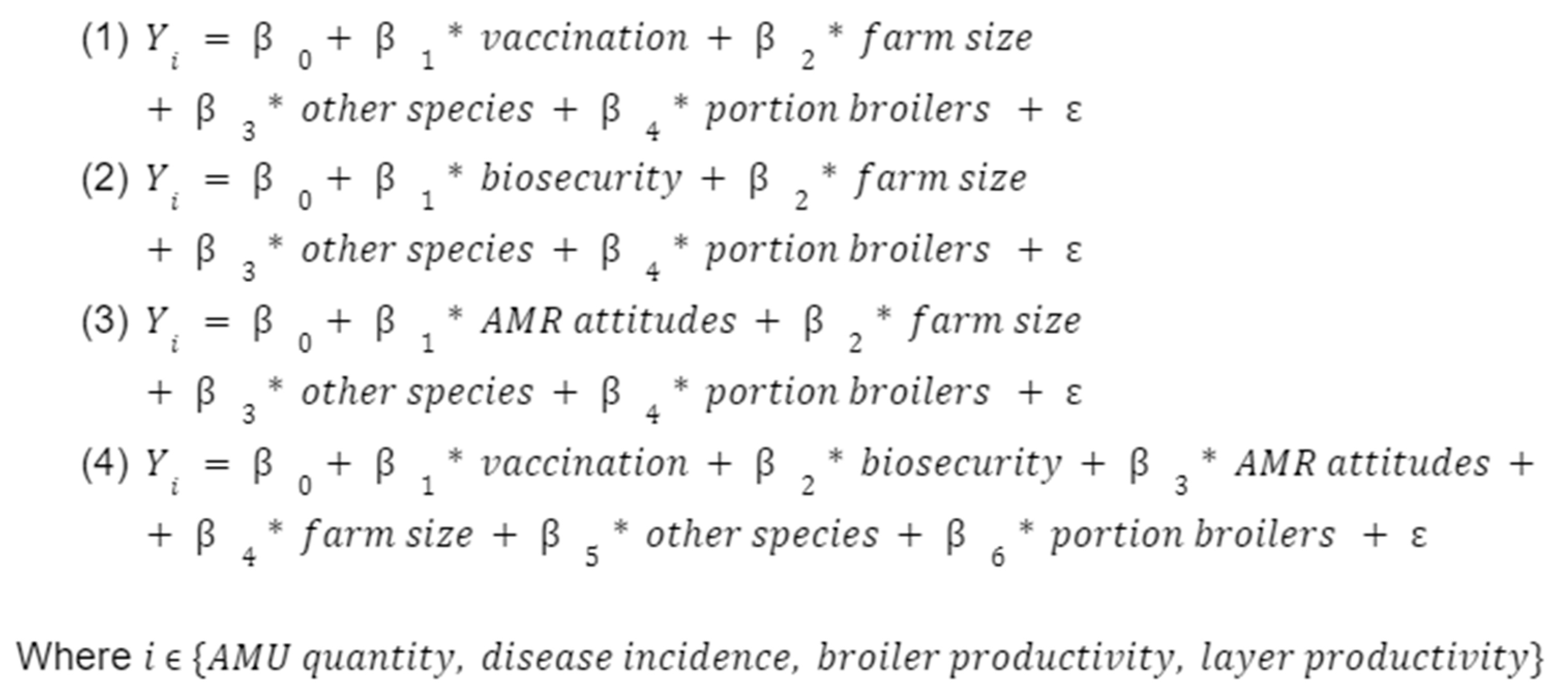

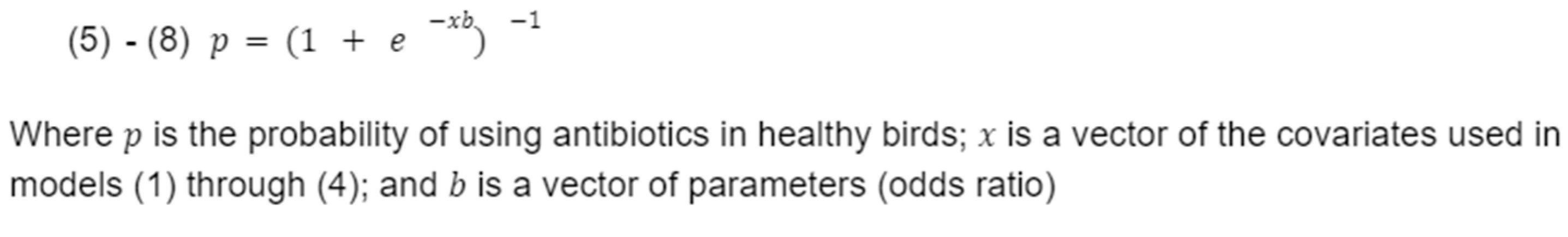

First, we regressed the quantity of antibiotics used (“AMU quantity”) against each of the three main covariates using ordinary least squares (OLS) (models (1)-(3)), and then against all three main covariates together (model (4)). We adjusted for key farm characteristics of farm size, presence of other species, and the ratio of broilers to layers. We then did this for other outcomes, namely disease incidence and productivity (“broiler productivity” and “layer productivity”).

Aside from wanting to investigate the determinants of AMU, we also look at disease incidence and productivity to see if the three measures of interest (vaccination, biosecurity, and sensibilisation) incur any tradeoffs in terms of profitability. Ultimately, if we recommend these measures as means of encouraging farmers to reduce or rationalise AMU, then we should be confident that this will not endanger their economic security or broader food security at the population level.

Following this, we regressed use of antibiotics on healthy birds against each of the three main categories of covariates using a logistic regression (logit). These logistic regressions were performed in order to see if any of the three measures being investigated improved prudent use of antibiotics.

4.4. Robustness and Further Specifications

We first tested the association between AMU and a large number of individual biosecurity measures, as opposed to the biosecurity index (“biosecurity”) used elsewhere. We accounted for multiple hypothesis testing using family-wise error rate (using Bonferroni correction (31)) and the false discovery rate (using the Benjamini-Hochberg step-up procedure (32)).

After this, we looked at the effect of our three main covariates on AMU using Heckman selection (19), with a selection function using variables that were seen to affect AMU in other specifications. This was done to take better account of farms which did not use antibiotics.

Finally, we looked at a number of interactions between key covariates to test some more specific hypotheses. All of these interactions looked at productivity and animal mortality as outcomes. The hypotheses, as described below, were:

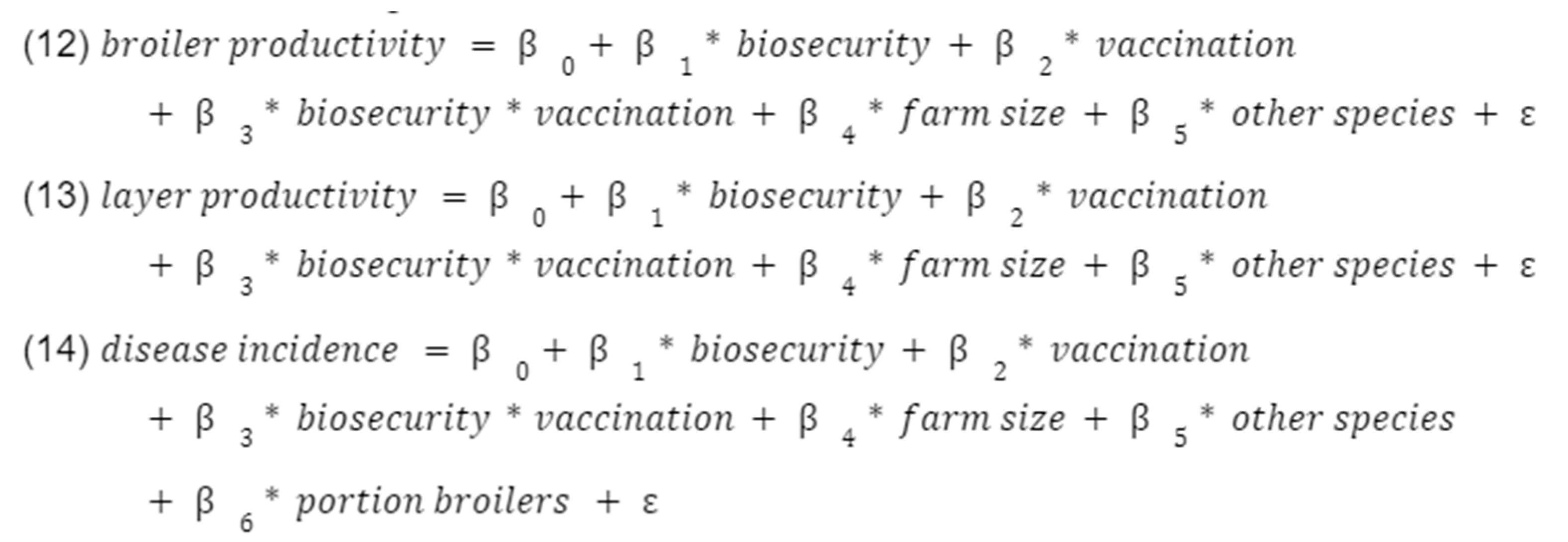

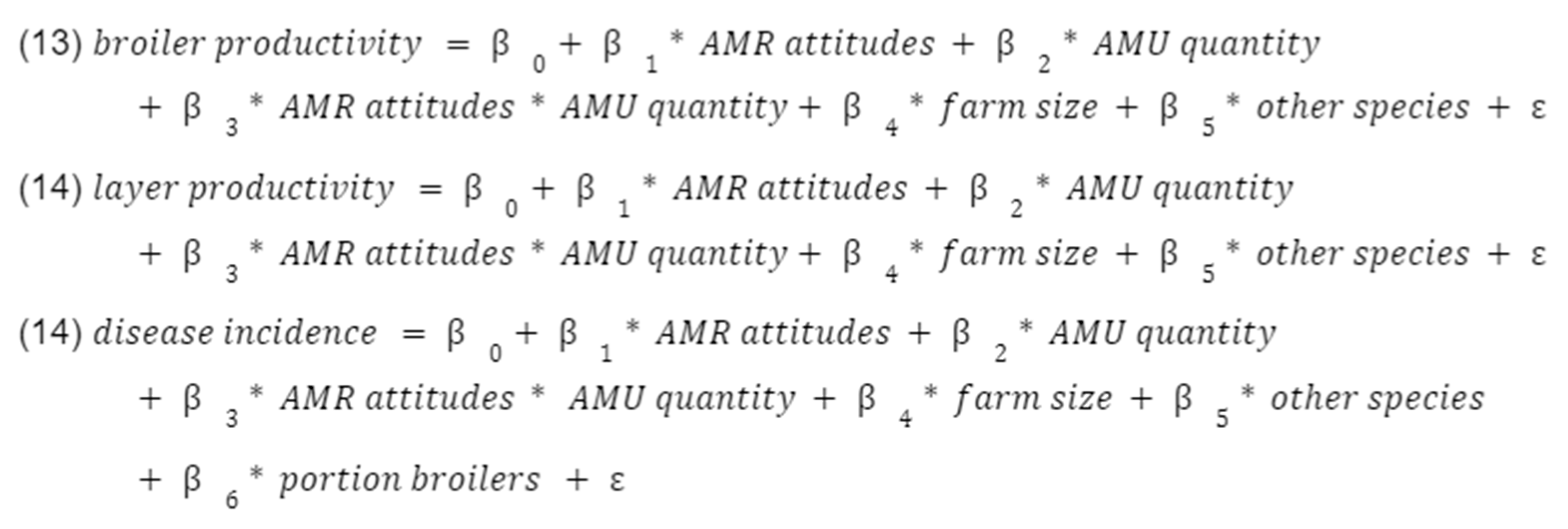

Interacting AMU with biosecurity to see if better biosecurity reduced the need for antibiotics in improving farm outcomes, i.e.

Interacting vaccination and biosecurity to see if these two measures are substitutes in terms of disease management, i.e.

And

Interacting AMR attitudes with AMU to see if better awareness of AMR increased the effectiveness of antibiotics as a disease management tool (following the hypothesis that AMU will be negatively associated with disease incidence), i.e.

5. Conclusions

We found evidence that biosecurity, vaccination, and attitudes towards AMR could mitigate the potentially negative effects of antibiotic withdrawal in semi-intensive poultry farms, and could improve antibiotic use prudence. These findings should be explored further using annual followup and larger sample sizes, and farm-level trials which combine antibiotic withdrawal and replacement with interventions in these three areas are a priority. Finally, these findings alone may not be sufficient to catalyse change in agricultural stewardship of antimicrobials. AMR in agriculture must always be seen as a structural rather than an individual issue, with stakeholders from across the One Health spectrum meaningfully consulted as part of research and policymaking.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: E.E., A.F., B.N., G.K. and M.D.; Methodology: E.E., A.F., N.N., A.G.F., G.K., and M.D.; software: E.E.; validation: E.E., N.N., G.K.; formal analysis: E.E.; investigation: A.F. and A.G.F.; resources: M.D.; data curation: E.E., A.F. and A.G.F.; writing – original draft preparation: E.E.; writing – review and editing: E.E., N.N., D.B., B.N., A.G.F., G.K., and M.D.; visualisation: E.E.; supervision: G.K. and M.D.; project administration: G.K. and M.D.; funding acquisition: E.E., N.N., D.B., G.K. and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JPIAMR, grant number 2021-182. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with nor the funders of this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (protocol code 28216 /RR/29425, date of approval 5 September 2022). The original data collection project received ethical and scientific approval from the Ministry of Health and Social Care of The Republic of Senegal (protocol reference SEN22/73, date of approval 31 August 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study, as well as the code used for data cleaning and analysis, are available in anonymised form on GitHub at

https://github.com/Trescovia/AMUSE-SEFASI-Sharing. The repository is password-protected, and will be made available upon request to those who email the corresponding reason and provide a reason for their desire to access it.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to colleagues at the Veterinary Services Directorate for their insights during the writing process, to attendees of the SEFASI Consortium workshop in Dakar in September for their thoughts on the preliminary results, and to the farmers who participated in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A.–Full Set of Survey Questions Used

The questionnaire used (translated into English) can be found in .PDF form here.

Appendix B.–Univariate Specifications

(Standard errors in parentheses).

Appendix C.–Specifications with Interactions between Our Main Covariates

(Standard errors in parentheses).

Appendix D.–Ethical and Scientific Approval for Original Data Collection

Appendix E.–Copy of Informed Consent Form (Translated into English)

Appendix F.–Correlations between Key Variables (Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient)

The whole sample.

Broilers only

Layers only

References

- OECD. Stemming the Superbug Tide: Just A Few Dollars More [Internet]. OECD; 2018 [cited 2022 Mar 9]. (OECD Health Policy Studies). Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/stemming-the-superbug-tide_9789264307599-en.

- Van Boeckel TP, Brower C, Gilbert M, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, Robinson TP, et al. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015, 112, 5649–54.

- Bennani H, Mateus A, Mays N, Eastmure E, Stärk KDC, Häsler B. Overview of Evidence of Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance in the Food Chain. Antibiot Basel Switz. 2020, 9, 49.

- Woolhouse M, Ward M, Bunnik B, Farrar J. Antimicrobial Resistance in Humans, Livestock and the Wider Environment. Philos Trans R Soc. 2015, 370, 20140083.

- Landers T, Cohen B, Wittum T, Larson E, Faan C. A Review of Antibiotic Use in Food Animals: Perspective, Policy, and Potential. Public Health Rep. 2012, 127.

- Cuong NV, Padungtod P, Thwaites G, Carrique-Mas JJ. Antimicrobial Usage in Animal Production: A Review of the Literature with a Focus on Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 75.

- Who we are | Antimicrobial Resistance | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 28]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/antimicrobial-resistance/quadripartite/who-we-are/en/.

- Target. Global Database for Tracking Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Country Self- Assessment Survey (TrACSS) [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 28]. Available from: http://amrcountryprogress.org/.

- Broom LJ. The sub-inhibitory theory for antibiotic growth promoters. Poult Sci. 2017, 96, 3104–3108. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vounba P, Arsenault J, Bada-Alambédji R, Fairbrother JM. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance and potential pathogenicity, and possible spread of third generation cephalosporin resistance, in Escherichia coli isolated from healthy chicken farms in the region of Dakar, Senegal. PLoS ONE. 2019, 14, e0214304.

- Dione MM, Geerts S, Antonio M. Characterisation of novel strains of multiply antibiotic-resistant Salmonella recovered from poultry in Southern Senegal. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012, 6, 436–442.

- World Bank Group. Pulling Together to Beat Superbugs. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / World Bank; 2019.

- Emes ET, Dang-Xuan S, Le TTH, Waage J, Knight G, Naylor N. Cross-Sectoral Cost-Effectiveness of Interventions to Control Antimicrobial Resistance in Livestock Production [Internet]. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2022 May [cited 2022 Jun 13]. Report No.: 4104382. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4104382. 4104.

- C C, Tp R, Em F, J O, J A, M G, et al. Early intensification of backyard poultry systems in the tropics: a case study. Anim Int J Anim Biosci [Internet]. 2020 Nov [cited 2022 Nov 16];14(11). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32576312/. 3257.

- Parkhi CM, Liverpool-Tasie LSO, Reardon T. Do smaller chicken farms use more antibiotics? Evidence of antibiotic diffusion from Nigeria. Agribusiness [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 16];n/a(n/a). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/agr.21770. 2177.

- Masud AA, Rousham EK, Islam MA, Alam MU, Rahman M, Mamun AA, et al. Drivers of Antibiotic Use in Poultry Production in Bangladesh: Dependencies and Dynamics of a Patron-Client Relationship. Front Vet Sci [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Nov 16];7. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2020.00078. 0007.

- Xu J, Sangthong R, McNeil E, Tang R, Chongsuvivatwong V. Antibiotic use in chicken farms in northwestern China. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020, 9, 10.

- AMUSE Livestock, version 2―Antimicrobial use in livestock production: A tool to harmonise data collection on knowledge, attitude and practices [Internet]. CGIAR Research Program on Livestock. 2020 [cited 2022 Oct 28]. Available from: https://livestock.cgiar.org/publication/amuse-livestock-version-2%E2%80%95antimicrobial-use-livestock-production-tool-harmonise-data.

- Heckman JJ. The Common Structure of Statistical Models of Truncation, Sample Selection and Limited Dependent Variables and a Simple Estimator for Such Models. In: Annals of Economic and Social Measurement, Volume 5, number 4 [Internet]. NBER; 1976 [cited 2022 Nov 1]. p. 475–92. Available from: https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/annals-economic-and-social-measurement-volume-5-number-4/common-structure-statistical-models-truncation-sample-selection-and-limited-dependent-variables-and.

- Hennessey M, Fournié G, Hoque MA, Biswas PK, Alarcon P, Ebata A, et al. Intensification of fragility: Poultry production and distribution in Bangladesh and its implications for disease risk. Prev Vet Med. 2021, 191, 105367.

- Marangon S, Busani L. The use of vaccination in poultry production. Rev Sci Tech Int Off Epizoot. 2007, 26, 265–274.

- Aboah J, Enahoro D. A systems thinking approach to understand the drivers of change in backyard poultry farming system. Agric Syst. 2022 Aug 10. 2022.

- STROBE [Internet]. STROBE. [cited 2022 Jul 13]. Available from: https://www.strobe-statement.org/.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R [Internet]. Boston, USA: RStudio; Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/.

- Hlavac M. stargazer: beautiful LATEX, HTML and ASCII tables from R statistical output. :11.

- Wickham H, RStudio. tidyverse: Easily Install and Load the ‘Tidyverse’ [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 22]. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyverse.

- Wickham H, Chang W, Henry L, Pedersen TL, Takahashi K, Wilke C, et al. ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 22]. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggplot2.

- Taiyun Wei, Simko V. corrplot Package [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/corrplot/vignettes/corrplot-intro.html.

- Wickham H, Roman F, Henry L, Müller K, RStudio. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dplyr/index.html.

- Bonferroni CE. Teoria statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilità. Seeber; 1936. 62 p.

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).