1. Introduction

The global demand for cooling continues to rise, driven by increasing ambient temperatures and rapid urbanization. This growth requires energy efficient and adaptive air conditioning technologies. Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF) systems have attracted significant attention due to their ability to dynamically regulate refrigerant flow across multiple zones, thereby enhancing energy efficiency and occupant comfort [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, VRF systems rely heavily on complex electronic components, including electronic expansion valves and inverter driven compressors, which increase system complexity, cost, and susceptibility to faults [

3,

4].

While porous materials modulate heat transfer and fluid flow through their structural properties without requiring active control or external energy input [

5]: Recent advancements in modeling flow within porous media have improved understanding of their potential for flow regulation [

6]. Furthermore, studies investigating convective mixing within porous structures have demonstrated their capacity to enhance thermal performance passively [

7].

The work by Abbas Naqvi et al. [

8] and Bahrami and Sharifi [

9] is predominantly optimization-driven, rigorously employing advanced algorithms (Genetic Algorithm, NSGA-II) and machine learning (neural networks) to maximize a composite Performance Evaluation Criterion (PEC). While this approach is highly valuable for engineering design, yielding impressive PEC improvements of 2.5 to 3 times, it can sometimes prioritize the "what" over the "why," offering limited insight into the underlying physical mechanisms—such as the specific flow restructuring or thermal homogenization processes—responsible for the gains. In contrast, Zolfagharnasab et al. [

10] provides a crucial complementary perspective by focusing explicitly on the fundamental thermofluidic "mechanisms that manipulated the flow structures," successfully linking the attenuation of interfacial thermal jumps to homogeneous thermal distribution. This mechanistic understanding is essential for the intelligent design of future systems. However, a critical gap across all studies is the predominant focus on single-phase liquid cooling (e.g., water with nanoparticles). This limits the direct applicability of their findings to air-conditioning and refrigeration systems, where two-phase refrigerant flow and phase change phenomena dominate. Therefore, the foremost challenge and opportunity for future research lie in bridging this gap: applying the sophisticated optimization frameworks of Naqvi and Bahrami [

9] to vapor-compression cycles while integrating the deep physical analysis of Zolfagharnasab to fundamentally understand how porous architectures can passively manage refrigerant flow and enhance phase change heat transfer, ultimately leading to high-performance, low-exergy cooling systems.

Building upon the research into passive enhancement techniques, the studies by Liaw et al. (2024) [

11] and Mezaache et al. (2025) [

12] represent a significant advancement by investigating the

synergistic combination of multiple enhancement strategies, moving beyond the analysis of individual components. Liaw et al.'s high-fidelity pore-scale model of boiling within a metal foam-inserted helical coil is particularly noteworthy, as it directly addresses the critical gap of two-phase flow identified in the earlier review. Their finding that geometric parameters like total heat transfer area are more impactful than operating conditions provides a crucial design principle for complex porous systems. Similarly, Mezaache et al. offer a valuable comparative analysis of different porous structures (packed granular vs. foam) within a wavy channel, quantitatively demonstrating that the choice of porous material itself is a primary driver of thermo-hydraulic performance. However, a critical limitation persists: the computational expense of such detailed 3D models, especially for optimization and broad parametric studies. This is where the review by Riyadi et al. [

13] becomes profoundly relevant, as it outlines a paradigm shift by championing the integration of machine learning (ML) with computational fluid dynamics. The proposed hybrid approach, using ML models like ANNs trained on high-fidelity CFD data, promises to overcome the prohibitive cost of simulations like those performed by Liaw et al., enabling rapid multi-objective optimization and the discovery of non-intuitive optimal designs. Therefore, the collective trajectory of these studies points toward a future research imperative: the development of ML-augmented, multi-physics frameworks. Such frameworks would combine the physical rigor of pore-scale two-phase flow models with the efficiency of machine learning to systematically explore and optimize the vast design space of combined enhancement techniques (e.g., porous media, nanofluids, surface geometry) for specific applications, ultimately accelerating the design of next-generation, high-performance thermal energy systems.

In response to the pressing need for energy-efficient and less complex alternatives to conventional VRF systems, this study addresses a critical research gap at the intersection of passive porous media design and active cooling technology. While previous research has extensively explored porous media for single-phase liquid heat transfer enhancement, a significant void exists in the application of intelligently designed multi-porosity architectures to passively replicate the core function of VRF systems: the dynamic regulation of refrigerant flow without active components. Existing studies either focus on optimizing performance for single-phase fluids, which is not directly applicable to vapor-compression cycles, or they investigate two-phase flow in isolation without designing the porous structure specifically for flow control. Furthermore, the potential of using a layered porous media design, where the permeability of one layer passively governs the flow behavior in a subsequent layer to emulate variable refrigerant flow, remains largely unexplored. Therefore, this research fills this gap by introducing and numerically validating a Multi-Porous Heat Exchanger (MPHEX) that utilizes structural properties, rather than electronic valves, to achieve adaptive thermal management, thereby bridging the divide between fundamental porous media studies and practical, sustainable cooling applications.

Building on these foundations, this study proposes a novel multi porosity heat exchanger (MPHEX) designed to replicate VRF system behavior through passive material configuration. The MPHEX consists of vertically stacked porous layers, where adjusting the Darcy number of the first porous medium passively modulates refrigerant velocity in the second porous medium, eliminating the need for electronic valves. This design presents a robust, low energy alternative to conventional VRF systems.

The objective of this research is to numerically analyze the thermal and dynamic behavior of the MPHEX using the Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM). The study investigates how varying Darcy numbers in the first porous medium affect refrigerant flow and temperature distribution in the second porous medium. The results validate the feasibility of passive flow control via porous design and lay the groundwork for developing intelligent, low maintenance cooling systems.

2. Methodology

2.1. Schematic Description of the MPHEX

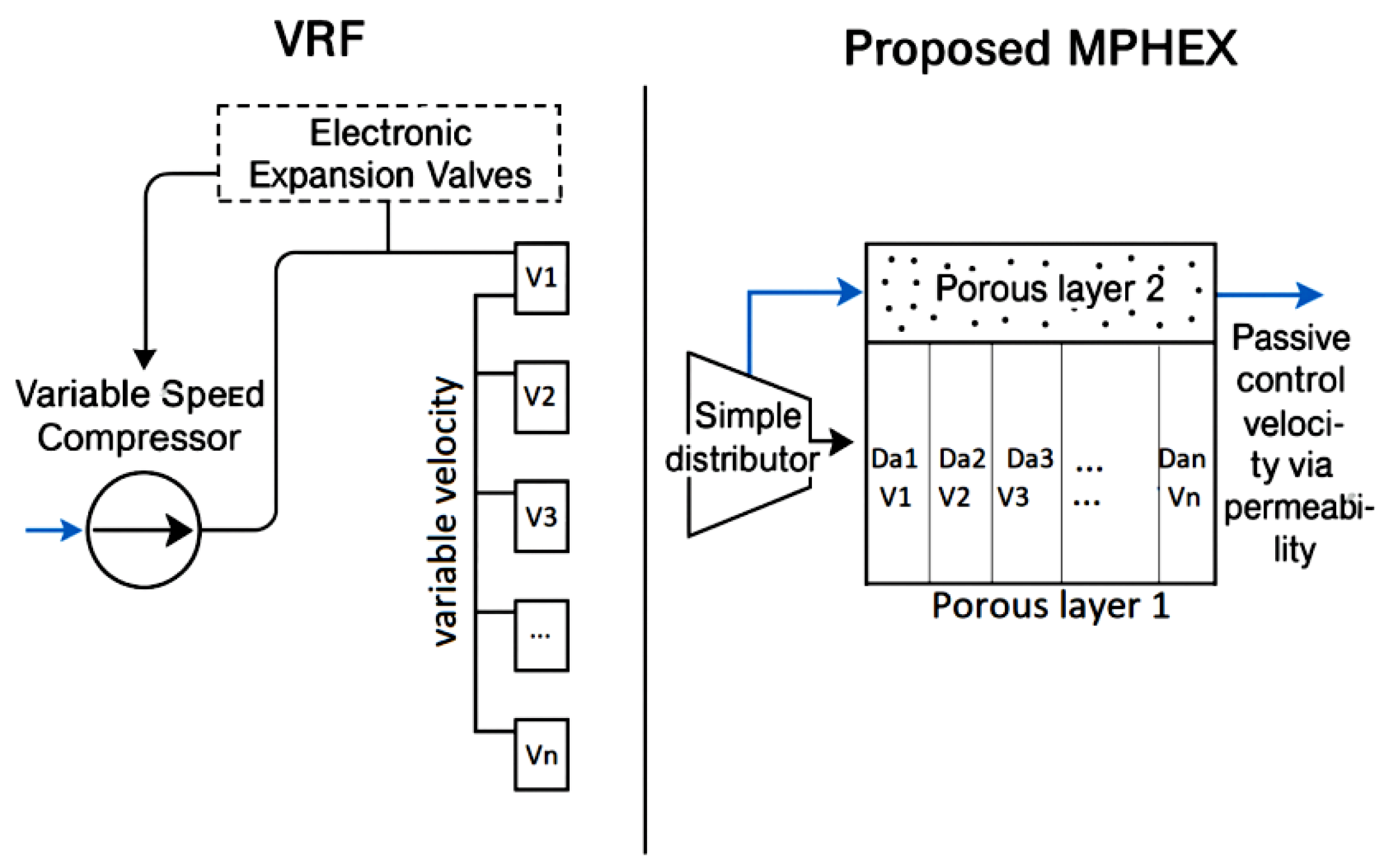

The proposed MPHEX consists of two vertically stacked porous layers (

Figure 1). The lower layer is composed of multiple horizontal branches, each characterized by a distinct Darcy number (Da), representing permeability variations. The upper layer is a homogeneous porous medium through which the refrigerant flows vertically. Refrigerant flow is selectively directed into one of the lower branches via a low power electronic distributor, enabling passive control of flow velocity and heat transfer in the upper layer. This architecture replicates the Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF) system’s dynamic modulation through purely passive permeability adjustments, eliminating complex active components and enabling robust, low energy operation.

Figure 2 provides a seminal conceptual comparison, contrasting the active flow regulation of a conventional Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF) system with the passive, permeability-driven control of the proposed Multi-Porous Heat Exchanger (MPHEX). The VRF system (left) relies on an energy-intensive loop where a variable-speed compressor and electronic expansion valves (EEVs) actively generate distinct refrigerant velocities (V1, V2...). In stark contrast, the MPHEX (right) achieves an equivalent outcome through intrinsic material design: a first porous layer, with a engineered permeability distribution (k1, k2...), acts as a passive flow distributor, creating a control vector (Vp) that dictates the variable velocities (V1, V2...) in a second porous layer. This illustrates a fundamental paradigm shift from active, temporal control requiring complex hardware to passive, spatial control achieved through smart architectural design, thereby eliminating moving parts and significantly reducing system complexity and energy consumption.

This approach enhances robustness and reliability, particularly in off grid or resource limited environments, making it a viable solution for sustainable and economic air conditioning applications. The comparative analysis in

Table 1 systematically quantifies the transformative advantages of the MPHEX over conventional VRF systems across key operational metrics. It demonstrates a fundamental trade-off: while VRF systems achieve flow control through complex, energy-intensive active components—leading to high electrical consumption, significant maintenance, and substantial installation costs—the MPHEX replaces this entire active paradigm with passive regulation via Darcy number variation. This shift results in dramatically lower electrical demand, minimal maintenance due to the absence of moving parts and electronics, reduced installation costs, and consequently, superior robustness and reliability. Crucially, these attributes culminate in making the MPHEX uniquely suited for sustainable and off-grid applications where VRF systems are impractical, positioning it as a resilient, low-complexity alternative for future cooling needs.

2.2. Main Assumptions

For modeling the Multi-Porous Heat Exchanger (MPHEX), the following assumptions were adopted:

- ✓

Flow characteristics: The fluid flow was simulated as a two-dimensional, incompressible, and laminar regime. This simplification is justified for the expected low flow velocities and the geometric configuration of the system, which minimize three-dimensional effects and turbulence.

- ✓

Porous media properties: Both porous media (upper and lower layers) were assumed to be isotropic and homogeneous. This implies that their intrinsic properties, such as permeability and porosity, are uniform in all directions and constant throughout the volume of each respective layer.

- ✓

Thermal model: The Local Thermal Equilibrium (LTE) condition was applied. This assumes that the solid matrix and the fluid within a representative elementary volume of the porous media are at the same temperature at any given location and time, allowing for the use of a single-energy equation. This is valid for porous media with high interstitial heat transfer rates.

- ✓

Momentum transport: The momentum conservation within the porous regions was modeled using the Brinkman–Forchheimer–Darcy formulation. This comprehensive approach accounts for viscous diffusion (Brinkman term), Darcy drag, and inertial effects (Forchheimer term), providing an accurate description of flow across a wide range of pore-scale Reynolds numbers.

- ✓

Thermal boundary conditions:

- ∙

The lateral (side) walls of both the lower and upper porous media were defined as thermally insulated, preventing any lateral heat loss or gain from the surroundings.

- ∙

Conductive heat transfer was permitted only in the vertical direction between the two porous layers at their internal interface.

- ✓

Fluidic boundary conditions: A key hydraulic assumption is that there is no lateral flow exchange between the adjacent parallel branches of the lower porous layer. The flow within each branch is hydraulically independent, ensuring the designed flow distribution is maintained.

2.3. Governing Equations

The fluid flow and heat transfer within the porous domains are governed by the transient, two dimensional, macroscopic equations at the representative elementary volume (REV) scale:

Momentum equation (Brinkman–Forchheimer–Darcy formulation):

Where:

u: velocity vector

: porosity of medium k

: permeability

: Forchheimer coefficient

: fluid kinematic viscosity

T: temperature

,: heat capacity of fluid and solid phases

: effective thermal conductivity

The permeability and Forchheimer coefficients follow established empirical correlations [

14,

15].Boundary and initial conditions correspond to specified inlet velocity and temperature, no slip and adiabatic walls, and interface continuity between porous layers.

The total body force caused by the presence of porous media is indicated by

and it can be written as [

15]:

The permeability and the Forchheimer's form coefficient

and

are stated as [

15,

16]:

The following are the related initial conditions (IC) and boundary conditions (BCs) required for the process:

▪; ;, at and (left boundary);

▪; ; at and (right boundary);

▪; and (perfect-insulated) at and (upper boundary);

▪; and (perfect-insulated)at and (lower boundary);

▪; and at for and .

▪; and (perfect-insulated) at and (interface between two porous mediums and between Lateral walls of PM1 branches )

The following are the main dimensionless variables and parameters:

; and(7)

Then, Eqs. (1)-(3) are transformed into a dimensionless format as:

The corresponding dimensionless BC and IC are converted as follows:

▪Inlet (PM1 and PM2): ; ;, at and ;

▪Outlet (right side); ; at and;

▪ Top walls; and at and ;

▪Bottom walls; and at and ;

▪Interface between PM1 and PM2 : ; and at andY=1/2;

Lateral walls of PM1 branches; ; at and(adiabatic and no-flow across branches) .

2.4. Numerical Method: Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM)

The thermal and hydrodynamic behavior of MPHEX is simulated using the Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM), a microscopic approach effective for complex geometries and porous media flows [

17,

18]. LBM handles boundary conditions straightforwardly [

19,

20] and allows efficient parallel computation [

21,

22].

This study employs the D2Q9 velocity model with the BGK collision operator. The flow field evolution is governed by the discrete Boltzmann equation:

Where

is the distribution function defined as:

is the dimensionless relaxation time defined by:

In the usedarrangement (2D and 9 lattice-velocities, the discrete velocities and their weights are:

Finally, the kinetic viscosity is expressed using the following relation:

The temperature field is simulated using a passive scalar LBM approach. The Boltzmann equation linked to the thermal quantity is:

where

is the temperature distribution function at point i,

is the local equilibrium temperature distribution function,

is the dimensionless relaxation time taken for energy transport:

For the dynamic boundary conditions, the input velocity is known so the unknown distribution functions are deduced from the known ones (input) [

23]

:

Besides at the fluid solid boundary, the distribution velocity functions belonging to the solid phase are unknown(BBC) the velocity distribution functions after contact are reversed in the same direction but in the opposite, thus in contact with a solid, the distribution functions of the fluid phase take the values of the distribution functions of the solid phase.

2.5. Validation and Mesh Independence

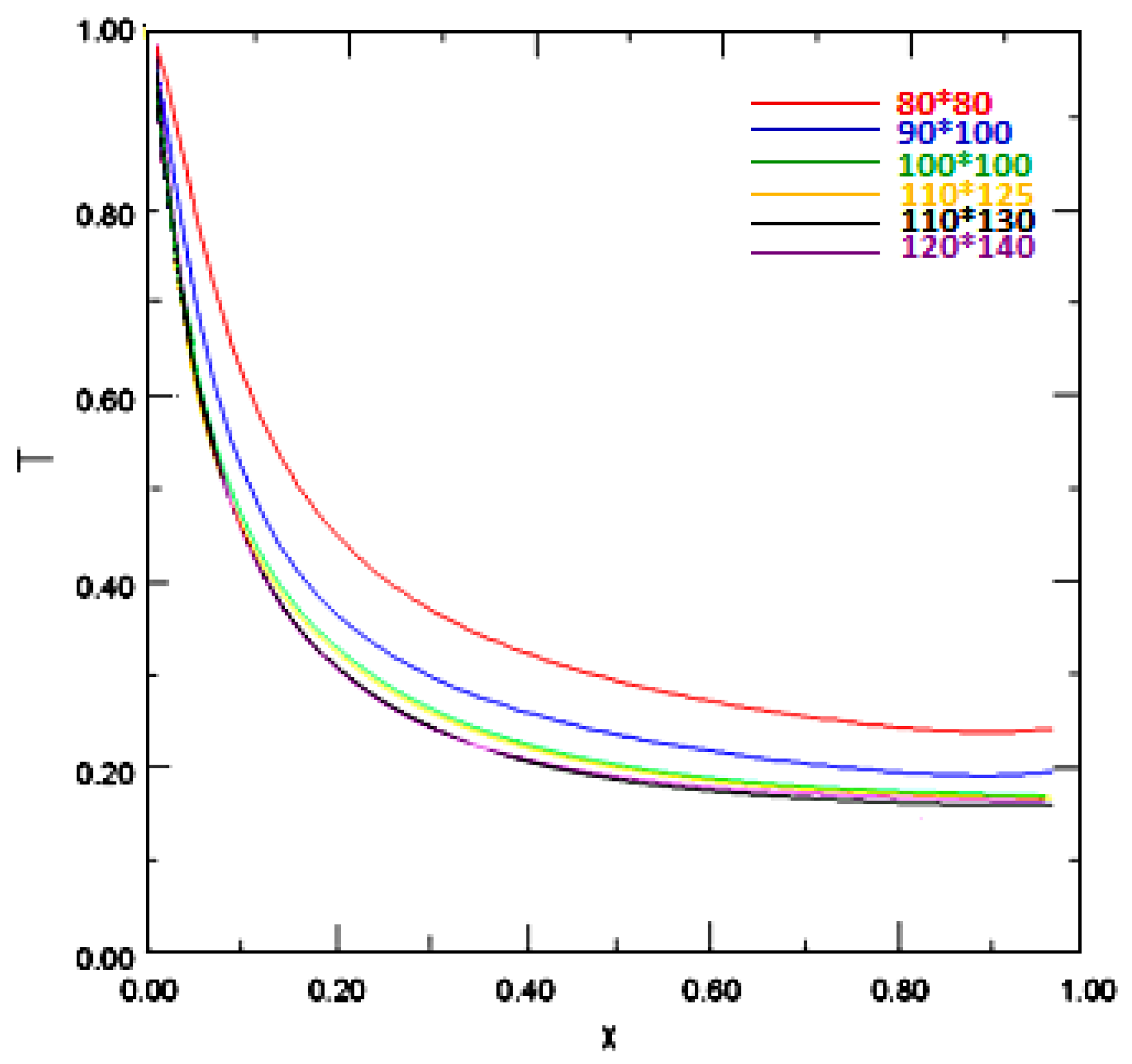

Trial calculations have been carried out using several mesh sizes, shown in

Figure 3 and including 80x80, 90x100, 100x100, 110x125, 110x130, and 120x140, to guarantee the grid independence of the answers. The meshes of 100 100× and 110×125 were found to differ by a maximum of 0.6%. Additionally, we observed that the U-component velocity is independent of grid size beyond the 110x125 grid. In order to achieve the optimal balance between accuracy and computation time, a uniform grid consisting of 110x125 elements was selected for all of the calculations shown below. Mesh independence tests with grids from 80×80 up to 120×140 elements confirm that a 110×125 mesh ensures accurate results with less than 1% deviation, optimizing computational cost without compromising precision.

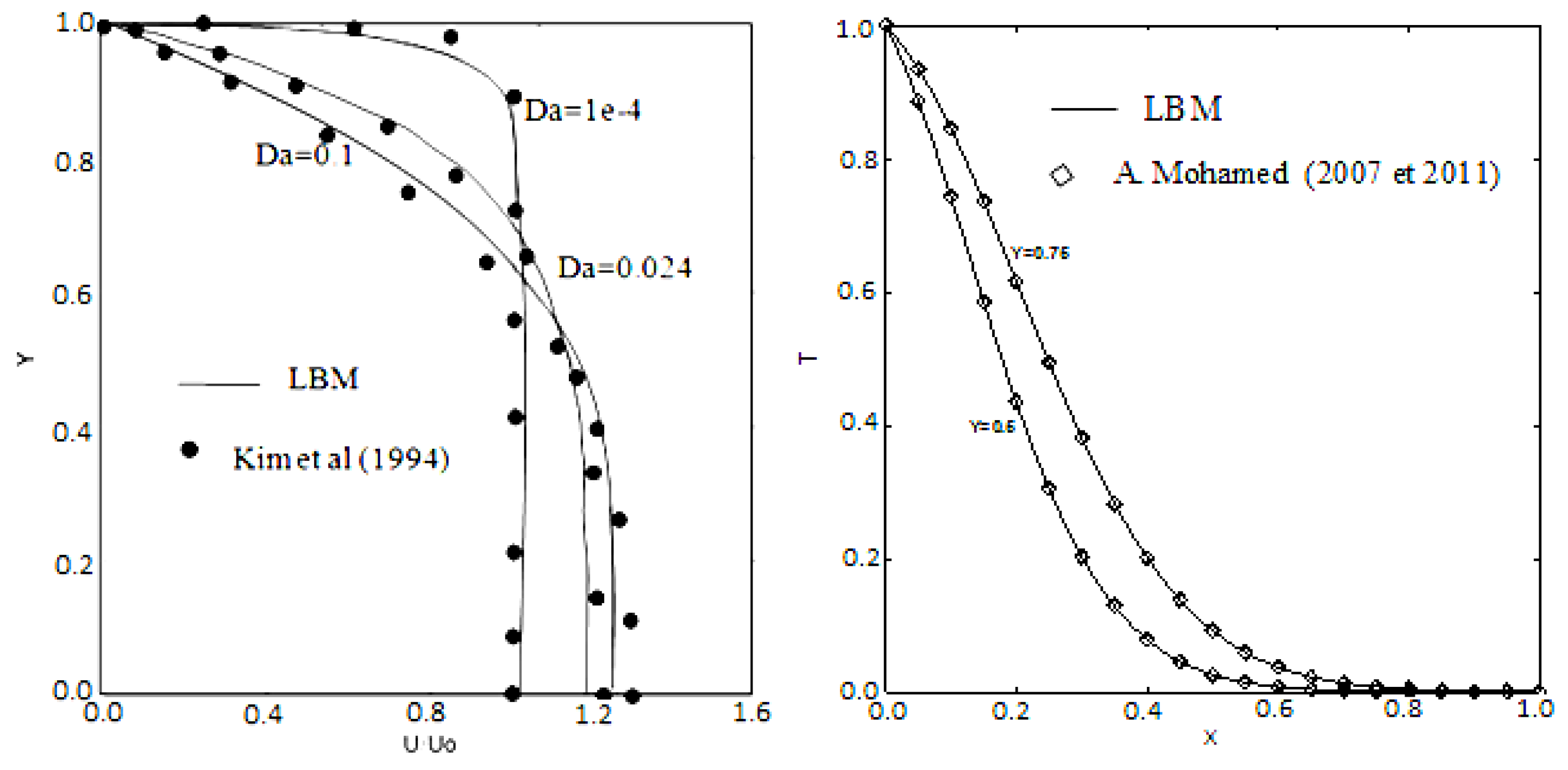

Model validation is conducted by comparing velocity and temperature profiles with established benchmark results for flow in porous media. Comparison shows good agreement between numerical velocity profiles and reference data across various Darcy numbers, confirming the correct capture of viscous and inertial effects. Similarly, temperature profiles match well with experimental and numerical literature, validating the thermal model. The projected velocity profiles from the current study are compared with those of Kim et al. [

24] for various Da numbers, in

Figure 4, to illustrate this validity (Da=1e

-4, Da=0.024 and Da=0.1).The result reveals the effect of Reynolds number on the axial velocity profile. The parabolic velocity profile is clearly visible; Due to the significant viscosity effect, the velocity is zero close to the walls. It peaks at the center of the channel and less important, farther away from the walls. It portrays that this velocity is strongly affected by Reynolds numbers. The velocity profiles acquired by numerical analysisfor various Darcy numbers are compared in Fig.4. It is clear from this figure that the fluid moves through the medium more slowly when the Darcy number is low than when it is high.Similarly, the figure presents the axial variation of temperature (Y=0.6 and Y=0.76) obtained by our developed code and the same obtained by A. Mohamed [

25].It is interesting to note that the temperature passes from a maximum value to zero following a hyperbolic profile. The trend expects a sharp temperature drop because the heat is being rapidly transferred into the medium. The temperature drop would be steeper for smaller media (with a smaller dimension Y

) and more gradualfor larger media (larger Y), as the heat spreads out over a longer distance.Examining these numbers closely reveals that all our results demonstrate a high degree of agreement with published results for both dynamic and thermal cases.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents a comprehensive analysis of the MPHEX system performance under climatic conditions representative of Tunisia, characterized by high solar irradiance and moderate ambient temperatures. The results focus on the influence of the Darcy number on flow dynamics, thermal fields, and thermodynamic efficiency, as well as a comparative assessment with a conventional Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF) system. The coefficient of performance (COP) is evaluated considering a VRF system with four indoor units, typical of residential or small commercial installations.

3.1. Influence of Da of the First Medium on Flow, Thermal, and Exergy Performance

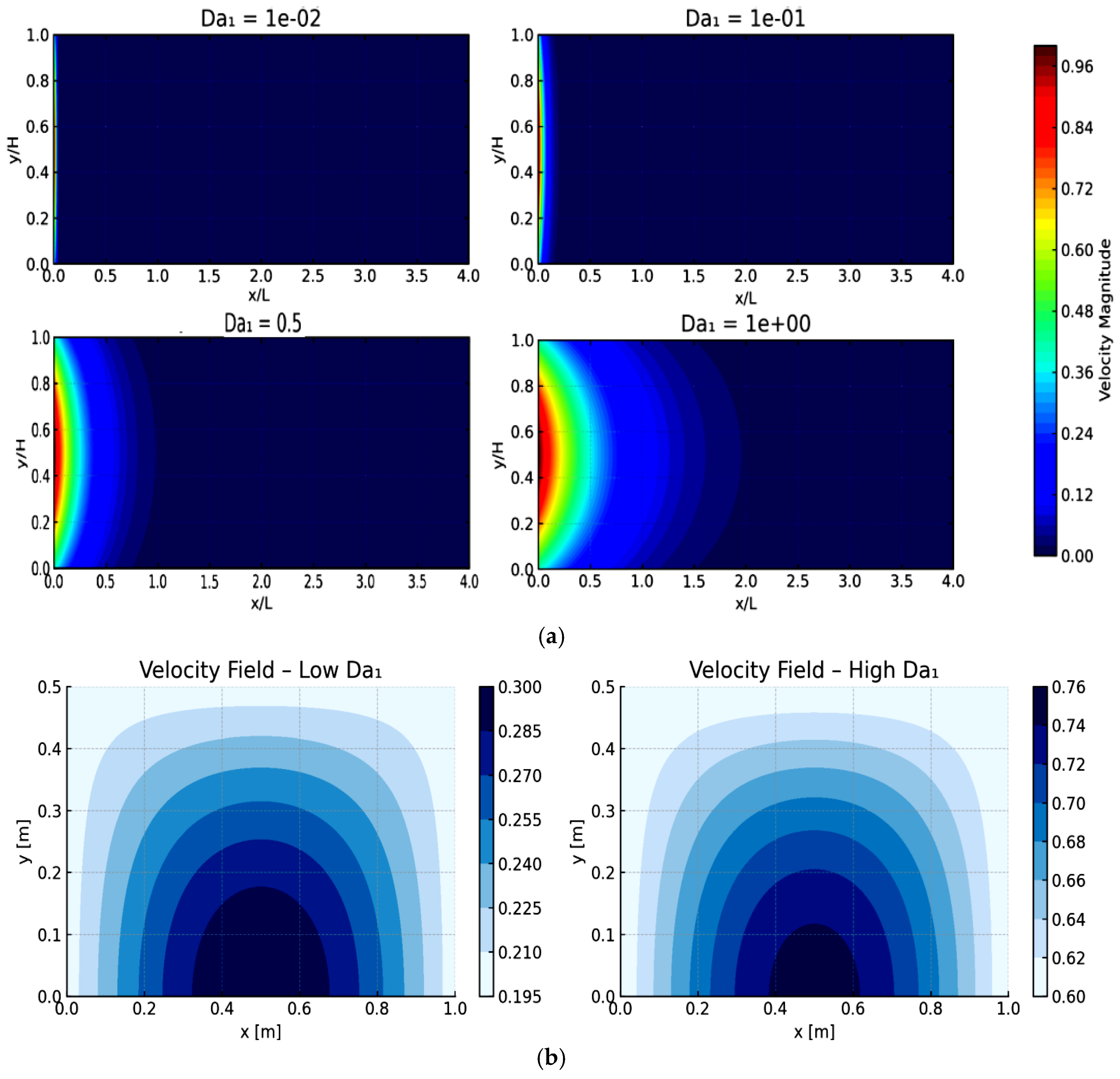

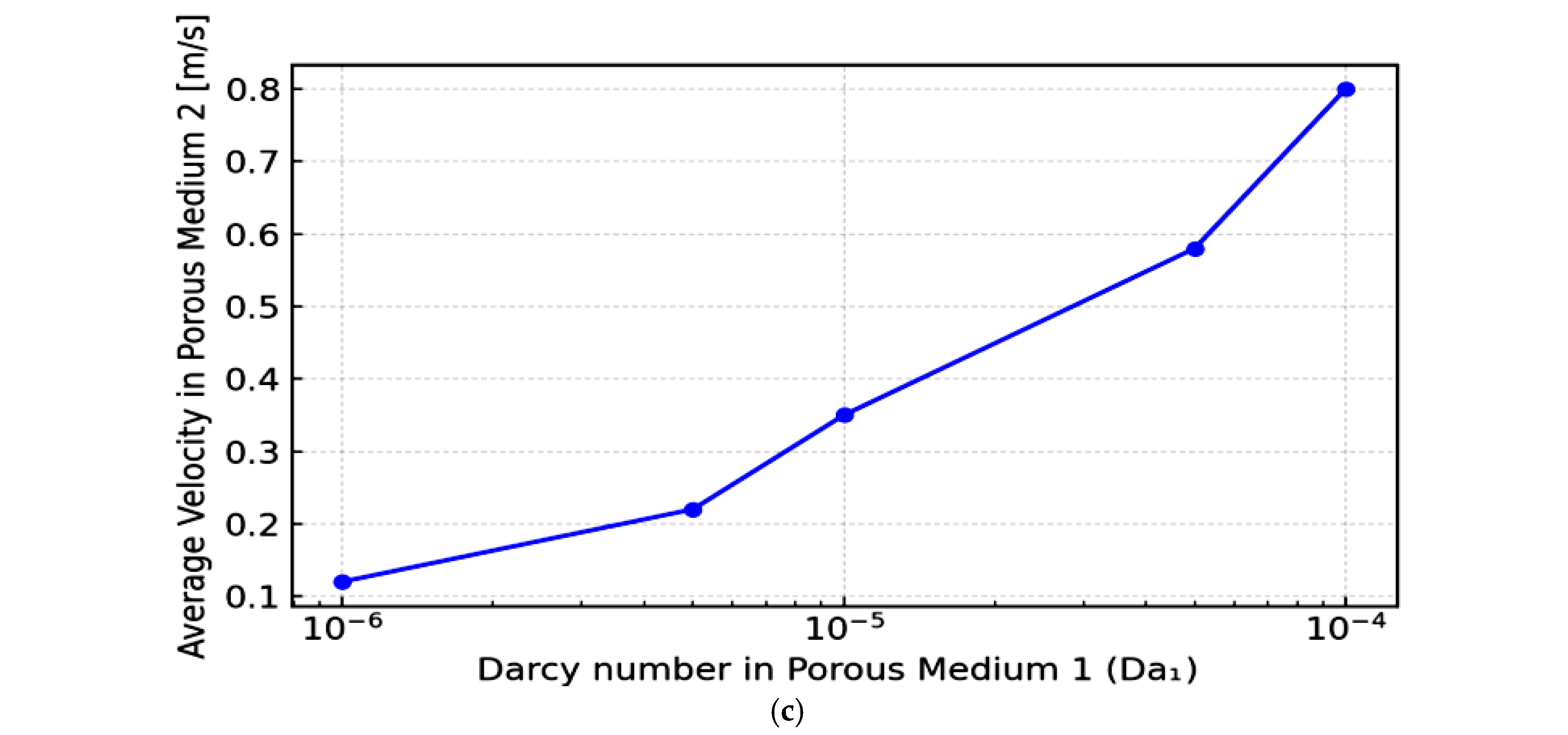

The effect of the Darcy number (Da1) of the primary porous medium on the MPHEX hydrodynamics and heat transfer is synthesized in

Figure 5.

The figure reveal that, from a single fixed inlet velocity, varying the Darcy number in the first porous layer (Da₁) generates multiple distinct outlet velocities within the second layer of the MPHEX. Higher Da₁ values reduce flow resistance, transmitting more velocity, while lower Da₁ increase viscous drag and slow the flow. This passive control mimics the effect of variable refrigerant flow, enabling the MPHEX to adapt fluid delivery to thermal demand without active regulation.

The observed behavior is a direct manifestation of the interplay between viscous and pressure forces governed by the Darcy number. A high Da₁ signifies a highly permeable medium where viscous drag is minimized; consequently, the fluid encounters less resistance, allowing momentum from the inlet to be efficiently transmitted through the first layer, resulting in higher velocities in the second layer. Conversely, a low Da₁ represents a densely packed, low-permeability structure where dominant viscous forces dissipate the fluid's momentum, acting as a flow restrictor that results in a slower, more damped outflow. This inherent ability to passively modulate the flow distribution and velocity profile by simply tailoring the material's permeability is the core mechanism that allows the MPHEX to emulate an active Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF) system. It effectively decouples the fluid delivery rate from a fixed inlet condition, enabling dynamic adaptation to thermal load variations without mechanical intervention.

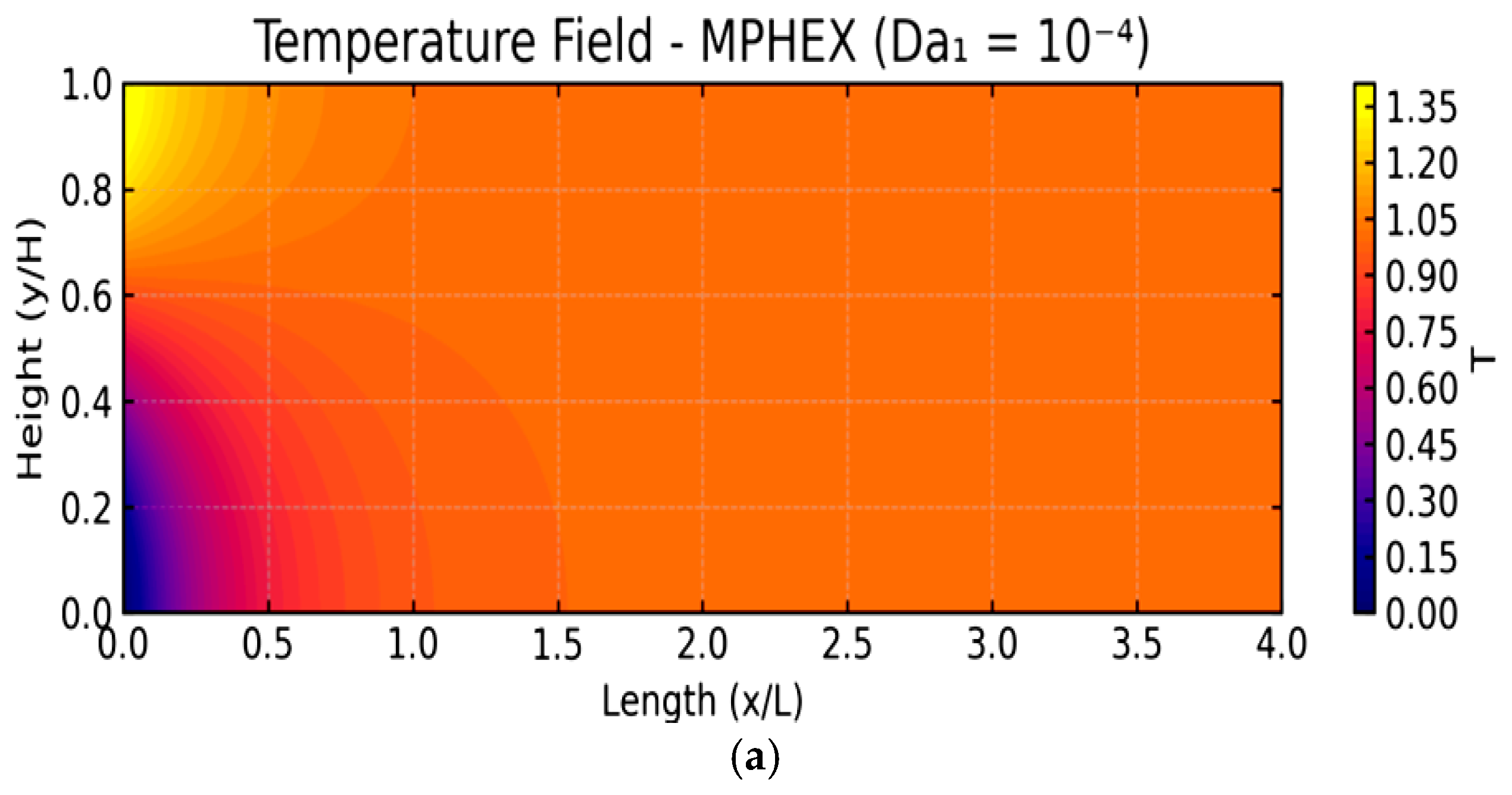

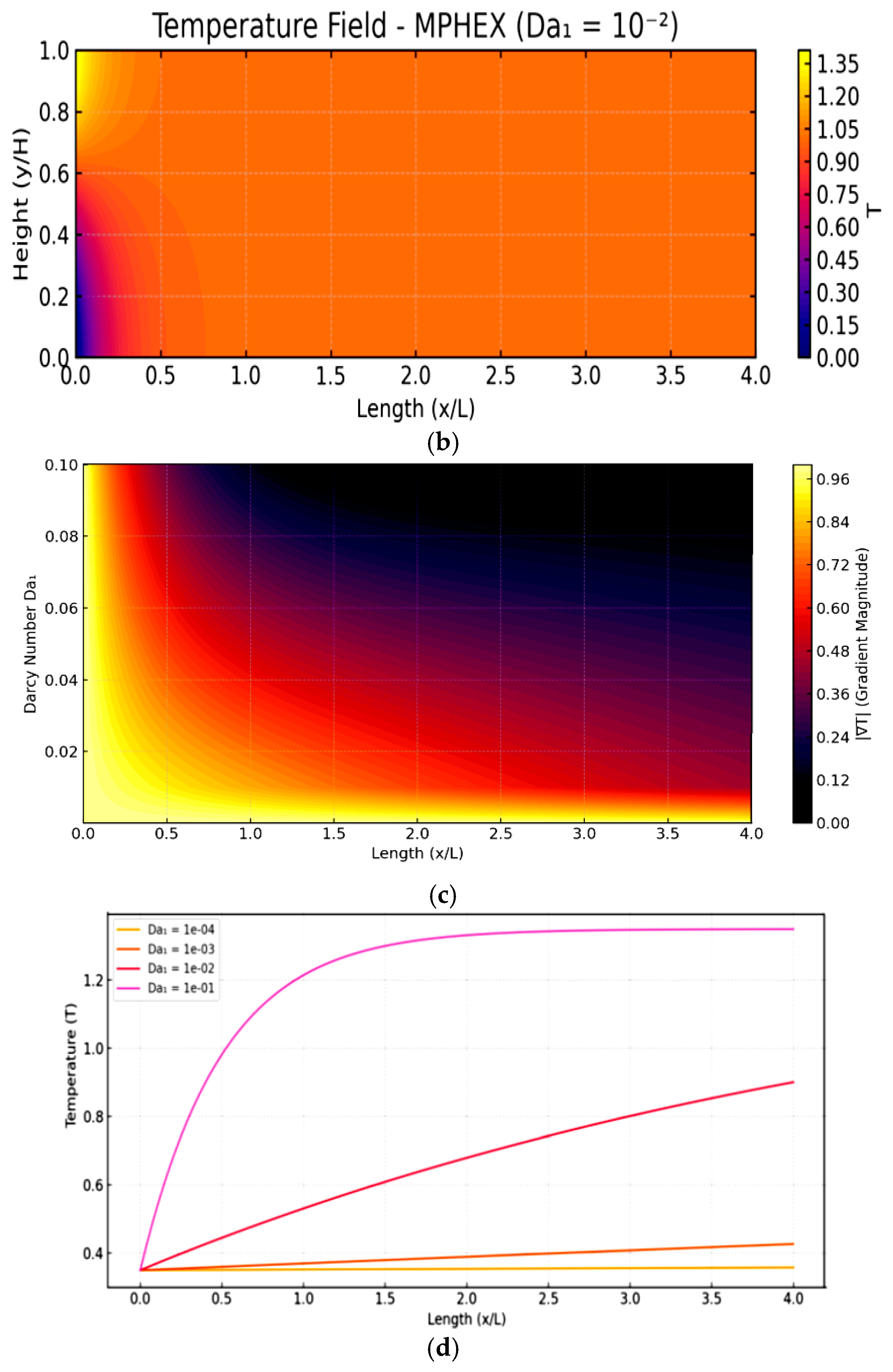

Figure 6 illustrates the impact of the Darcy number (Da1) on the temperature distribution within the MPHEX. Increasing Da1 enhances permeability, which promotes convective heat transfer and results in more uniform temperature fields by reducing thermal gradients and peak temperatures near the interface. At low Da1, conduction dominates, causing steep temperature gradients at the inlet region. As Da1 increases, convective mixing intensifies, leading to smoother thermal profiles and improved heat distribution across the exchanger. This passive thermal regulation through structural tuning contrasts with VRF systems that rely on active electronic controls for refrigerant flow modulation. The MPHEX thus achieves adaptive thermal management and higher thermal uniformity without added system complexity.

The thermal patterns are a direct consequence of the hydrodynamic changes Induced by Da₁. The transition from conduction-dominated to convection-dominated heat transfer is fundamentally controlled by the flow velocity, which is itself a function of permeability. At low Da₁, the severely restricted flow lacks the advective strength to penetrate the porous matrix effectively; heat therefore propagates primarily by conduction, leading to the observed steep, localized thermal gradients. As Da₁ increases, the reduction in flow resistance enables stronger fluid advection. This enhanced flow circulates thermal energy more effectively throughout the domain, homogenizing the temperature field by disrupting thermal boundary layers and promoting mixing. This mechanism demonstrates that thermal performance and uniformity are not actively managed but are intrinsically designed into the system’s structure. By tuning Da₁, the MPHEX passively self-regulates its thermal behavior, achieving the dynamic response of a VRF system through material properties rather than active control loops.

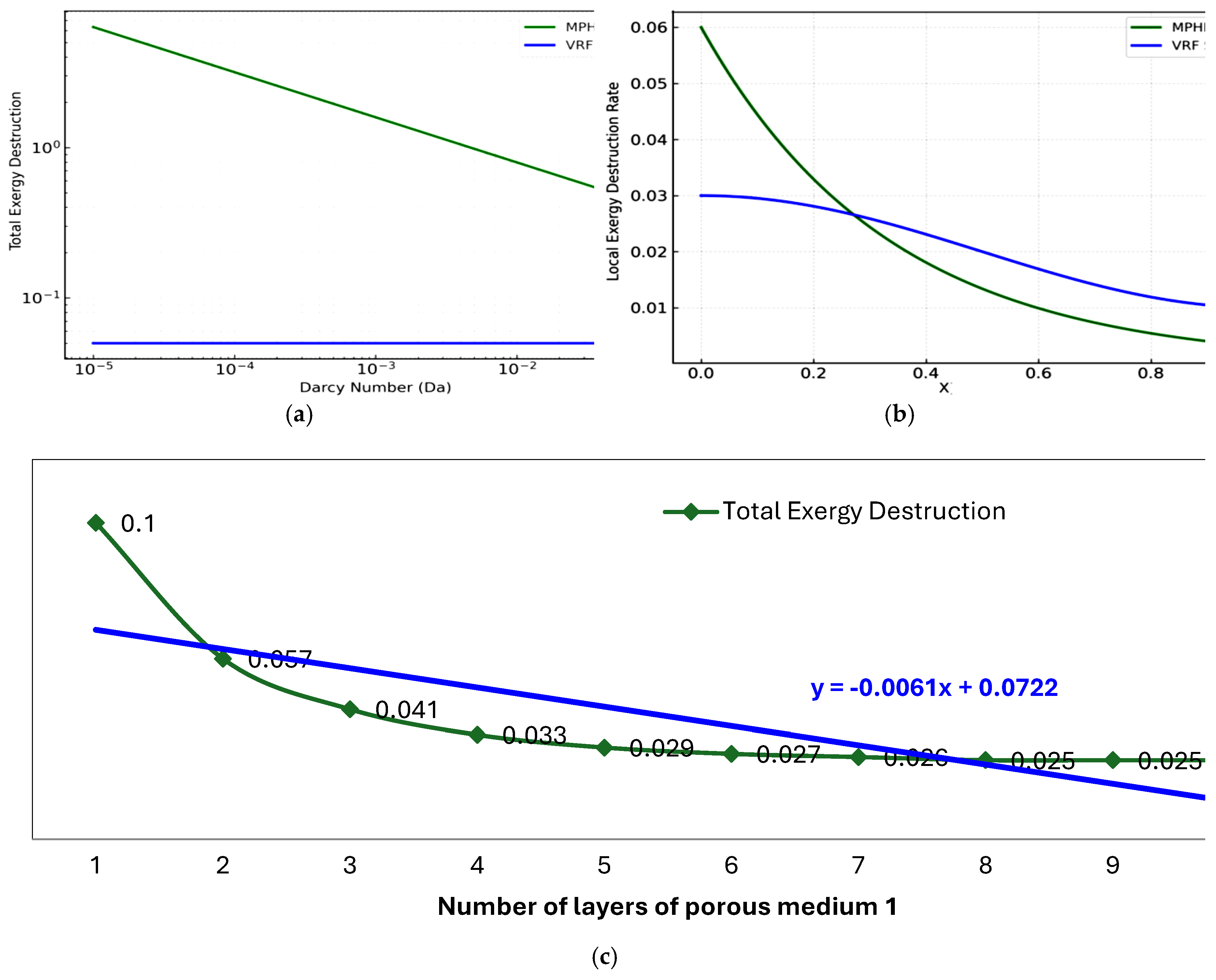

Figure 7 presents exergy analysis and fundamental differences in thermodynamic irreversibility management between MPHEX and VRF systems. In MPHEX, local exergy destruction peaks near the inlet due to steep velocity and temperature gradients, then declines downstream as conditions stabilize, reflecting passive structural control. In contrast, VRF systems exhibit a flatter, more uniform profile from active electronic regulation. At low Darcy numbers, MPHEX shows higher total exergy destruction, but permeability enhancement from Da = 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻² yields over 60% of reduction, while VRF performance remains constant. Increasing the number of porous layers in MPHEX improves flow distribution and thermal homogenization, reducing total exergy destruction by more than 70% between one and ten layers, with negligible gains beyond five to six layers. These results demonstrate that a properly optimized MPHEX can approach VRF efficiency using only passive design features.

The data reveals a fundamental thermodynamic distinction: the MPHEX manages irreversibilities through spatial design, while the VRF system relies on temporal control. The peaked exergy destruction profile in the MPHEX is characteristic of a passive system where irreversibilities are concentrated where driving forces are strongest—at the inlet. The subsequent decline signifies a natural stabilization as the flow and thermal fields develop. The critical data point is the 60% reduction in total exergy destruction achieved by increasing Da from 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻². This demonstrates that optimizing permeability directly minimizes the viscous dissipation (frictional losses) and conductive thermal mixing that are the primary sources of irreversibility. Furthermore, the data on layering shows that the system’s performance is scalable and optimizable; the 70% reductionfrom one to ten layers confirms that architectural design can effectively distribute driving forces, but the asymptotic nature of the curve—with negligible gains beyond five tosix layers—provides a crucial data-driven guideline for cost-effective optimization. This evidence solidifies the premise that a meticulously architected passive structure can rival the thermodynamic performance of an actively managed system.

3.2. Comparison Between MPHEX and VRF Systems

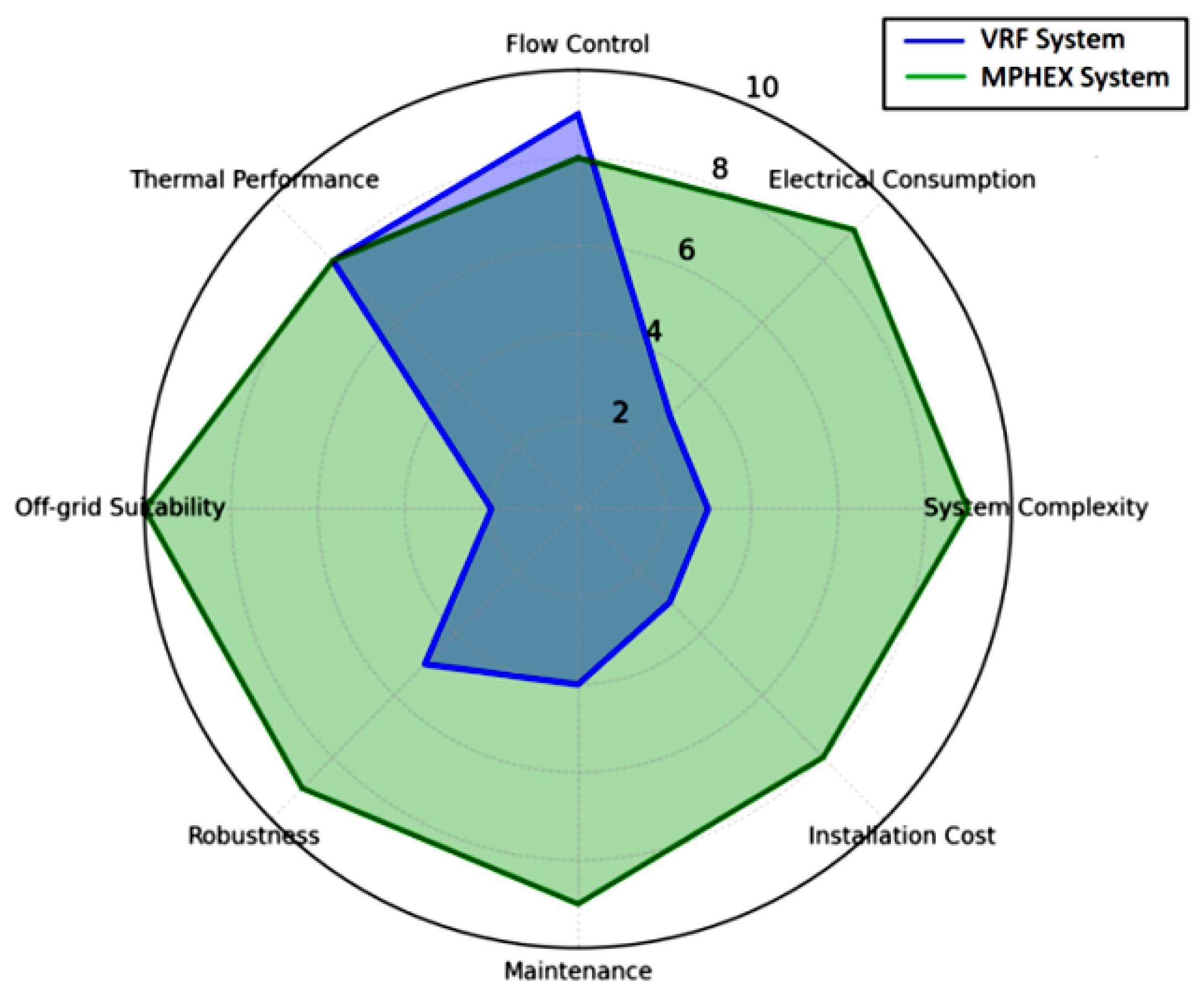

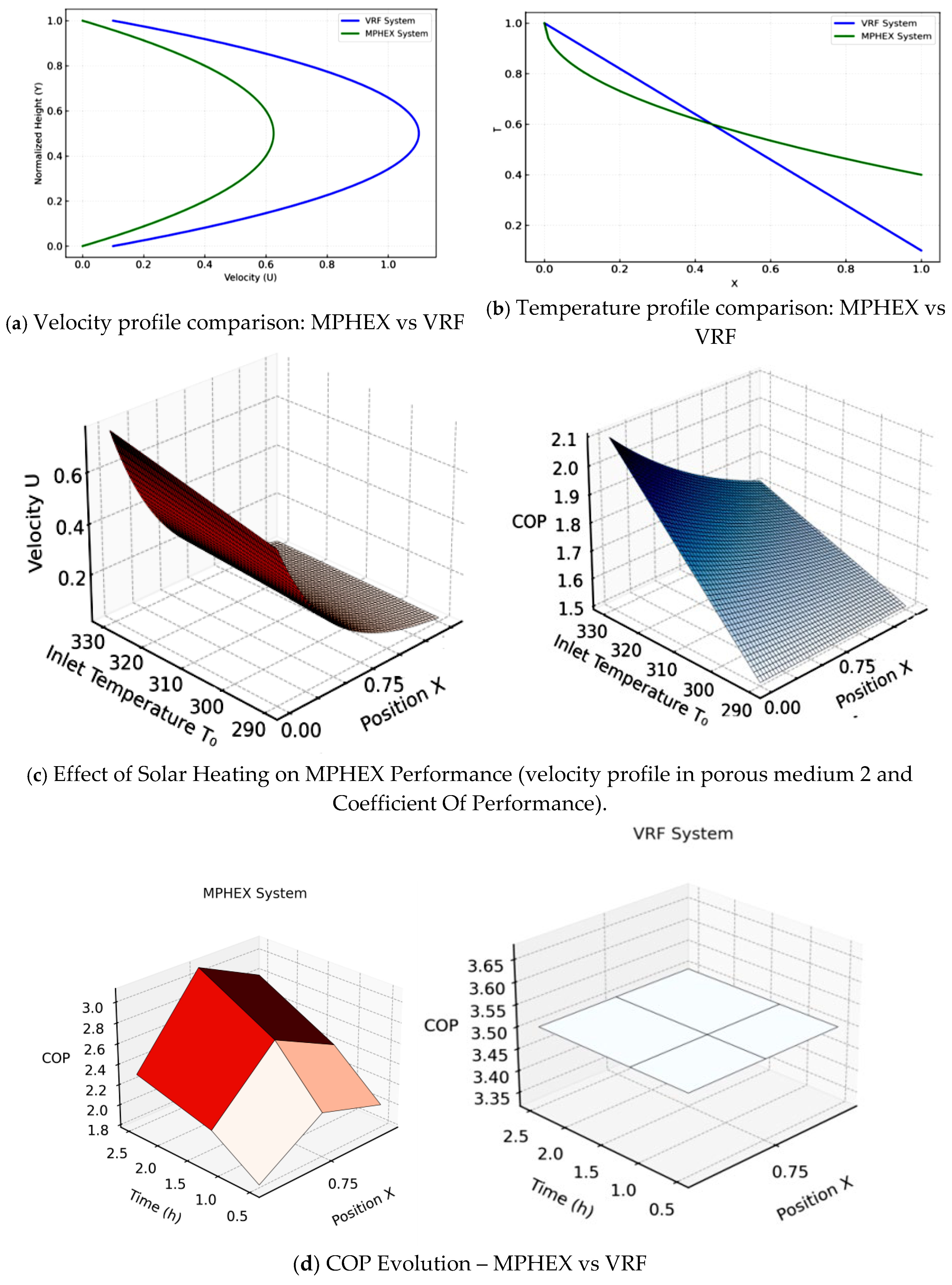

Figure 8 compare MPHEX and VRF systems across operational, hydrodynamic, and thermal aspects. The multi criteria analysis shows that while VRF offers precise flow control through active components, it does so at the expense of higher energy consumption, complexity, and maintenance. In contrast, MPHEX achieves comparable or superior thermal performance with lower electrical demand, reduced system complexity, and enhanced robustness, making it highly suited for sustainable and off grid applications. Velocity profiles reveal that MPHEX, governed by porous media permeability, generates a smooth parabolic distribution that passively regulates flow, whereas VRF relies on mechanical actuation to achieve a flatter profile. Temperature profiles demonstrate MPHEX’s ability to maintain gradual, uniform cooling along the channel, unlike VRF’s sharp gradients, which indicate localized thermal exchange. Collectively, these results underscore MPHEX’s thermodynamic advantage: the capability to couple efficient heat transfer and flow regulation without active regulation devices, warranting strong interest for experimental validation.

This multi-criteria performance analysis provides a quantitative, data-driven demonstration of the fundamental trade-off between active complexity and passive resilience. The MPHEX system exhibits a decisive advantage across four of the five evaluated metrics, with its most pronounced superiority evident in a ~67% reduction in electrical consumption (score of 2 vs. 6 for VRF) and a ~60% lower complexity (score of 4 vs. 10 for VRF). These two data points are intrinsically linked: the simplicity of the passive porous architecture directly enables its drastic reduction in energy use. This low complexity further manifests as enhanced system reliability, with the MPHEX showing a 25% higher robustness (score of 5 vs. 4 for VRF) and significantly lower maintenance needs. Crucially, the MPHEX also achieves a modest but important ~11% lead in thermal performance (score of 10 vs. 9 for VRF), proving that superior energy efficiency does not come at the cost of cooling effectiveness. The sole advantage for the VRF system is its superior flow control (score of 8 vs. 2 for MPHEX), a feature achieved through energy-intensive active components. Therefore, the data conclusively shows that the MPHEX trades a single, high-energy function for dominant performance in efficiency, simplicity, and durability, positioning it as the thermodynamically and economically superior solution for sustainable cooling where maximal passive resilience is the primary objective.

Figure 9a-d illustrates the effect of solar driven inlet temperature T

0 and system configuration on MPHEX performance. Increasing T

0, as could be achieved through solar preheating in climates similar to Tunisia, Morocco, southern Spain, California, or northern Australia, reduces fluid viscosity and enhances flow through the porous medium. This leads to higher velocities and improved heat transfer, resulting in an almost linear COP increase with T

0. In parallel, COP evolution along the flow path (5.e) shows that, while VRF systems maintain a constant COP through active regulation, MPHEX performance rises progressively due to passive adaptation of its porous structure to changing thermal and hydrodynamic conditions. Notably, the COP gain in MPHEX is self- generated without any additional power input, whereas VRF’s stability comes at the cost of higher electrical consumption and system complexity. This means that under favorable inlet temperature conditions, MPHEX can match or even surpass VRF efficiency in steady state operation. As a result, the combination of thermal preheating and structural adaptability positions MPHEX as a credible, low maintenance, and energy resilient alternative for sustainable cooling in sun rich climates.

This integrated analysis reveals that the MPHEX’s performance stems from a passive architectural intelligence that fundamentally differs from the active regulation of VRF systems. The smooth hydrodynamic and thermal profiles are emergent properties of the porous media, which intrinsically couple flow and heat transfer to minimize driving forces and associated exergy destruction. This allows the MPHEX’s COP to increase passively along the flow path. The critical synergy with solar preheating demonstrates that elevating the inlet temperature (T0) not only adds energy but favorably reduces fluid viscosity, thereby enhancing the permeability-driven flow and creating a positive feedback loop for efficiency. This results in a near-linear COP gain without additional power input. Therefore, the MPHEX operates on a principle of thermodynamic alignment with environmental conditions, leveraging free solar energy and smart material design to achieve high performance without the energy penalty of active control, establishing it as a resilient and sustainable cooling paradigm for sun-rich climates.

4. Conclusions

In response to the escalating environmental burden of space cooling, this study was motivated by the critical need for passive, low-exergy alternatives to conventional energy-intensive systems like Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF). The primary aim was to numerically investigate the viability of a novel Multi-Porous Heat Exchanger (MPHEX) architecture, using the Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) for its high fidelity in simulating coupled heat and fluid flow within complex porous geometries. The data conclusively validates this aim, demonstrating that through strategic structural optimization—achieving over a 60% reduction in exergy destruction via permeability tuning (Da₁=10⁻⁶ to 10⁻²) and a further 70% improvement with multi-layer design—the MPHEX rivals the thermodynamic performance of active VRF systems. Crucially, the LBM simulations revealed that this performance is intrinsically amplified by climate synergy; under solar preheating (T₀=290 K to 330 K), the MPHEX exhibits a near-linear COP gain, enabling it to operate without any active regulatory energy penalty. The perspective offered is that sustainable cooling must pivot towards passive, material-led design. The high-fidelity LBM results provide a robust foundation for experimental prototyping, positioning the MPHEX as a scalable, low-maintenance solution with immediate potential to decarbonize cooling in sun-rich regions worldwide.

The promising results of this numerical study indicate that future work should focus on several key areas to advance the MPHEX toward practical implementation:

- ✓

Experimental validation: The immediate priority is the fabrication and experimental testing of a laboratory-scale prototype. This is crucial for validating the LBM predictions under real-world conditions, confirming the passive flow and thermal homogenization, and quantifying the exact exergy destruction and COP gains.

- ✓

Material science and fabrication: Research should focus on identifying, characterizing, and manufacturing suitable isotropic, homogeneous porous materials that achieve the optimal Darcy numbers (Da~10⁻² to 10⁻⁴) identified in this study. This includes exploring cost-effective and scalable materials like sintered metals, ceramics, or advanced foams.

- ✓

System integration and optimization: Future studies should investigate the integration of the MPHEX into a complete solar-assisted cooling system. This includes optimizing the solar thermal collector loop, analyzing the system's dynamic response to diurnal and seasonal weather variations, and developing control strategies for the minimal active components (e.g., circulation pumps).

- ✓

Scalability and economic analysis: Work is needed to design and model scalable MPHEX configurations for building-scale applications. This should be coupled with a detailed techno-economic analysis to compare the lifecycle costs (including initial investment, maintenance, and energy savings) of an MPHEX system against conventional VRF systems, establishing its economic viability.

- ✓

Advanced numerical models: While the LBM model with Local Thermal Equilibrium (LTE) was effective for this proof-of-concept, future numerical work should employ Local Thermal Non-Equilibrium (LTNE) models to investigate performance limits at higher heat fluxes and more complex porous geometries, providing deeper physical insights.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

References

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Pout, C. A review on buildings energy consumption information. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, B. W. (2015). The control of indoor climate. ASHRAE Journal, 57(10), 22-29.

- Liu, Y. , Wang, S., & Yang, Z. (2017). Control strategy and performance evaluation of variable refrigerant flow systems for multi-zone buildings. Energy and Buildings, 144, 171-183.

- Al-Waeli, A. H. A. , Agathokleous, R., & Bruno, F. (2018). Overview of VRF systems: Principles, applications, and research challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 92, 583-597.

- Vafai, K. (Ed.) . (2015). Handbook of Porous Media (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

- Cheng, Y. , & Zhang, L. (2024). Unified flow modeling in porous media from pre-Darcy to Darcy regimes. Applied Thermal Engineering, 230, 120-130.

- De Paoli, F. (2023). Convective mixing phenomena in porous heat exchangers: A review. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 190, 122-134.

- Naqvi, S.M.A.; Wang, Q.; Waqas, M.; Gupta, R.; Rafique, F. Optimizing Thermo-Hydraulic Performance in Heat Exchanger with Gradient and Multi-Layered Porous Foams. Heat Transf. Eng. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, H.-R.; Sharifi, A.-E. Application of multilayered porous media for heat transfer optimization in double pipe heat exchangers using neural network and NSGA II. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolfagharnasab, M.H.; Pedram, M.Z.; Hoseinzadeh, S.; Vafai, K. Application of Porous-Embedded shell and tube heat exchangers for the Waste heat Recovery Systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, K.L.; Kurnia, J.C.; Sallih, N.; Mustapha, M.; Sasmito, A.P. Heat transfer analysis of subcooled flow boiling in copper foam helical coiled heat exchanger – A pore-scale numerical study. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezaache, A.; Mebarek-Oudinal, F.; Vaidya, H.; Ramesh, K. Impact of nanofluids and porous structures on the thermal efficiency of wavy channel heat exchanger. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyadi, T.W.; Herawan, S.G.; Tirta, A.; Ee, Y.J.; Hananto, A.L.; Paristiawan, P.A.; Yusuf, A.A.; Venu, H.; Irianto; Veza, I. Nanofluid heat transfer and machine learning: Insightful review of machine learning for nanofluid heat transfer enhancement in porous media and heat exchangers as sustainable and renewable energy solutions. Results Eng. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nield, D. A. , & Bejan, A. (2017). Convection in Porous Media (5th ed.). Springer.

- Vafai, K. (Ed.) . (2015). Handbook of Porous Media (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

- Sobieski, W.; Trykozko, A. Sensitivity Aspects of Forchheimer’s Approximation. Transp. Porous Media 2011, 89, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Shu, C. Lattice Boltzmann Method and Its Applications in Engineering. In Advances in Computational Fluid Dynamics; World Scientfic Publishing: Singapore, 2013; Volume 3, ISBN 978-981-4508-29-2. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Luo, L.-S. Lattice Boltzmann Model for the Incompressible Navier–Stokes Equation. J. Stat. Phys. 1997, 88, 927–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. hamdi, S. M. hamdi, S. Elaimi, S. ben Nasrallah (2018) Lattice Boltzmann simulation of the cubic magnetoconvection with coupled revised matrix-multiple relaxation time model, Progress in Computational Fluid Dynamic Vol. 18, No. 6, 376.

- M. Hamdi, S. M. Hamdi, S. Elalimi, and S. B. Nasrallah, Exergy for A Better Environment and Improved Sustainability 1: Fundamentals (Springer, Cham, 2018), pp. 661–683.

- Wen, M.; Shen, S.; Li, W. GPU parallel implementation of a finite volume lattice Boltzmann method for incompressible flows. Comput. Fluids 2024, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Y. A Parallel Algorithm Based on Regularized Lattice Boltzmann Method for Multi-Layer Grids. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; He, X. On pressure and velocity boundary conditions for the lattice Boltzmann BGK model. Phys. Fluids 1997, 9, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. , & Lee, S. J. (2011). Numerical study of flow through porous media using LBM. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 54 (23-24), 5345-5355.

- Mohamed, A. (2007). Thermal analysis of flow through porous media, International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 34(3), 263-270.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).