Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Outcomes

Study Population

Data Sources and Study Tools

Ethical Considerations

Statistical Analysis

Results

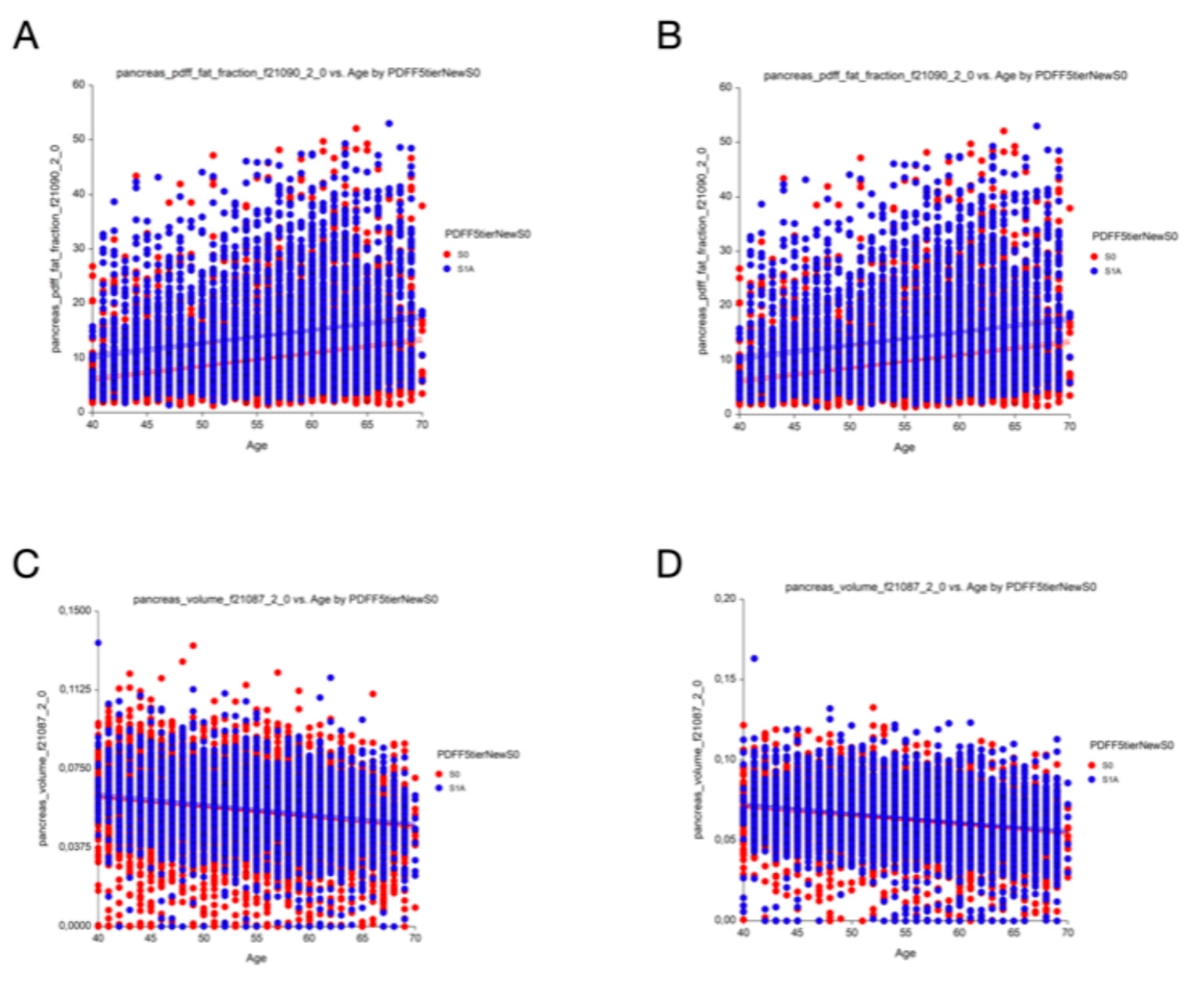

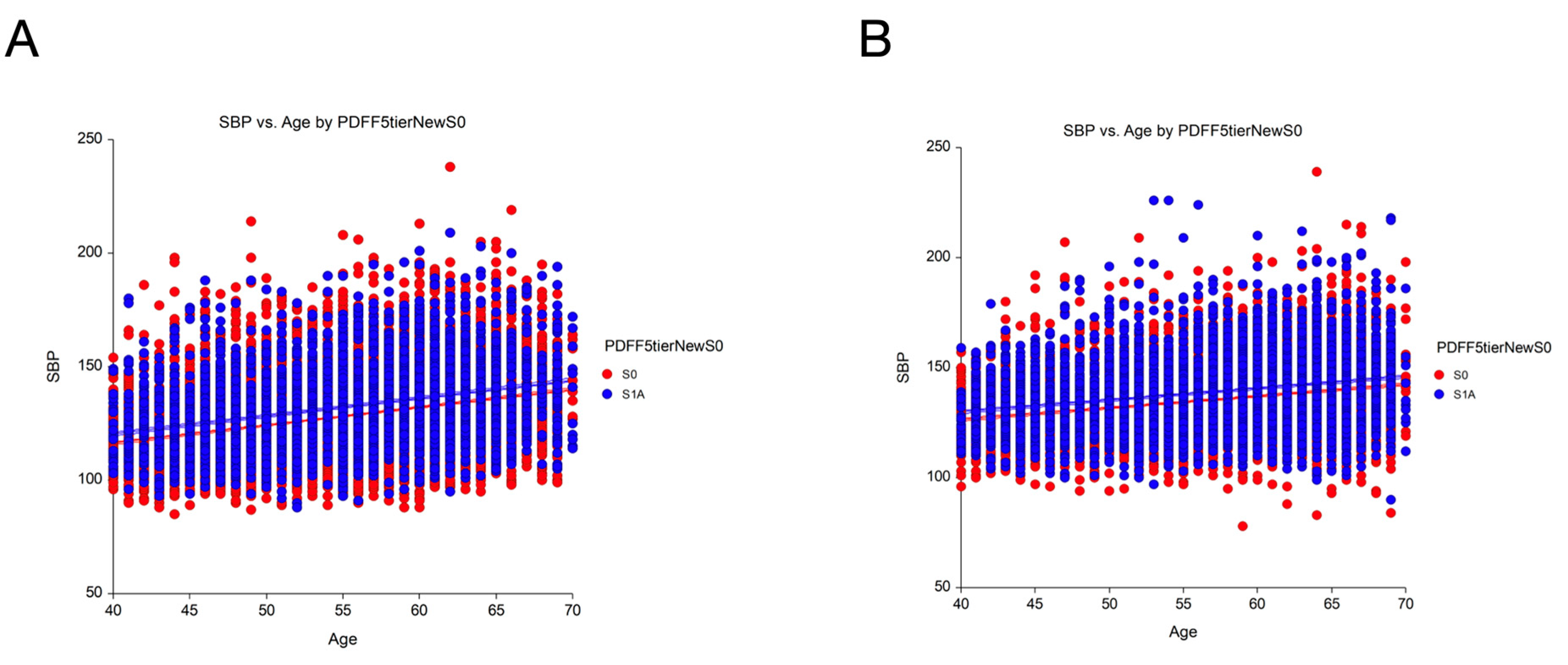

Prevalence and Differences in Clinical Characteristics

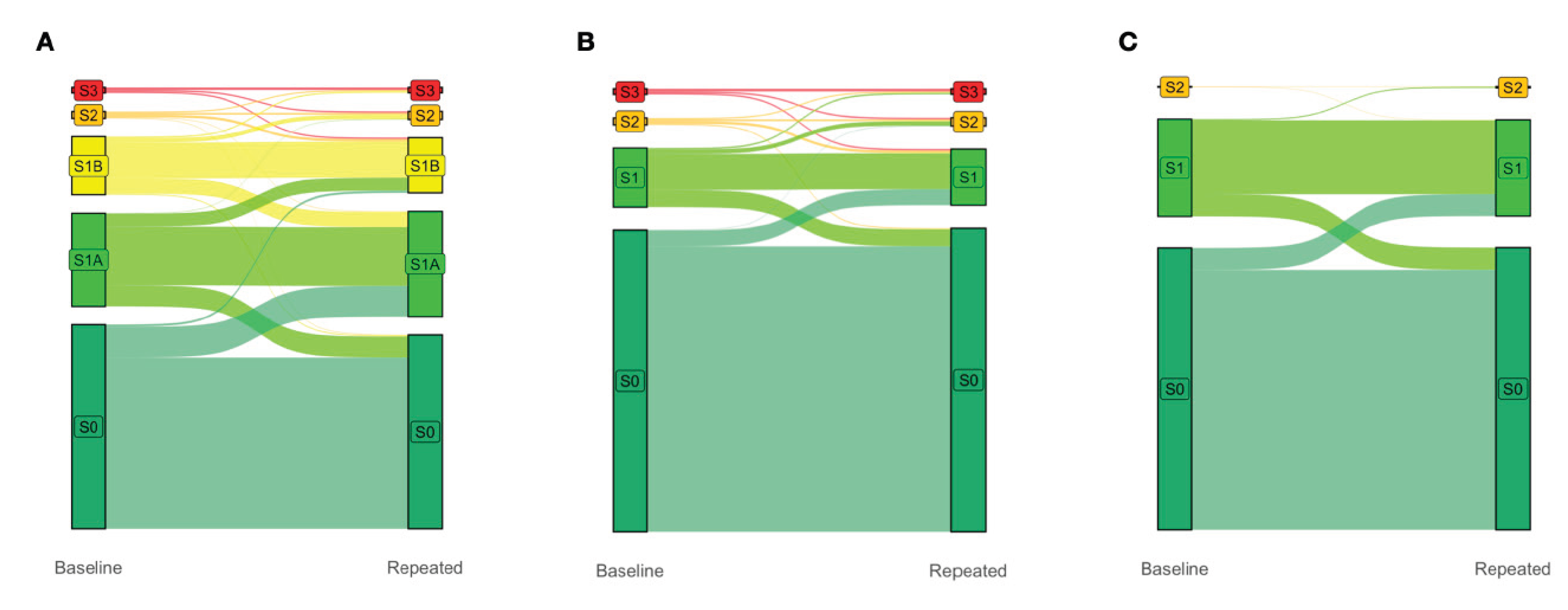

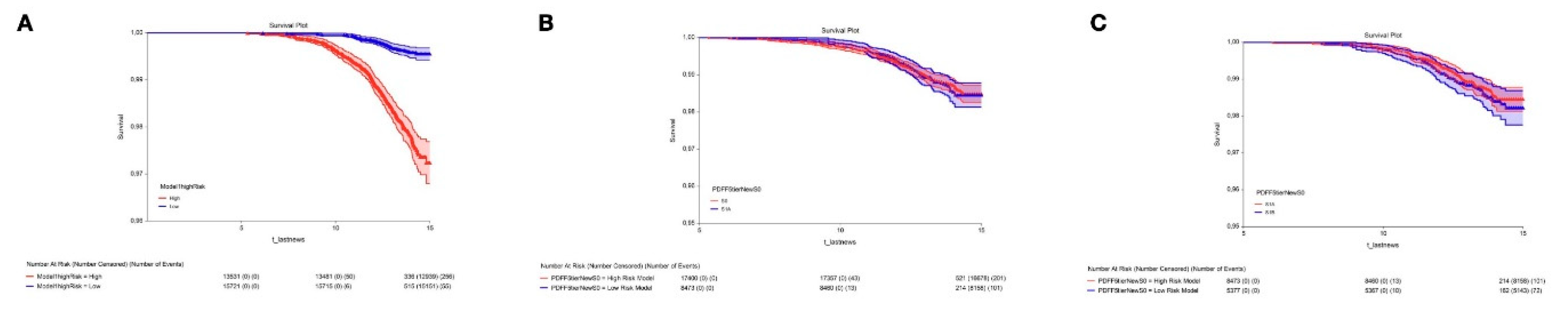

Differences in Prognostic Ability (Figure 2)

Impact of the S1A Stage in the Definition of Steatotic Liver Disease

Discussion

Clinical Relevance of S1A: First Outcome

Overall Mortality of Early Steatosis: Second Outcome

Redefining Disease Prevalence: Third Outcome

Strengths

Limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W.; et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005, 41, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratziu, V.; Charlotte, F.; Heurtier, A.; Gombert, S.; Giral, P.; Bruckert, E.; et al. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005, 128, 1898–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poynard, T.; Paradis, V.; Mullaert, J.; Deckmyn, O.; Gault, N.; Marcault, E.; et al. Prospective external validation of a new non-invasive test for the diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021, 54, 952–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poynard, T.; Deckmyn, O.; Pais, R.; Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Peta, V.; Bedossa, P.; et al. Three Neglected STARD Criteria Reduce the Uncertainty of the Liver Fibrosis Biomarker FibroTest-T2D in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Diagnostics (Basel). 2025, 15, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwal, F.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Loomba, R.; Rinella, M.E. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Update and impact of new nomenclature on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidance on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2024, 79, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, L.C.; Snyder, K.; Yager, T.D. The effect of uncertainty in patient classification on diagnostic performance estimations. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0217146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.K.; Bernstein, N.; Huang, D.Q.; Tamaki, N.; Imajo, K.; Yoneda, M.; et al. Clinical and histologic factors associated with discordance between steatosis grade derived from histology vs. MRI-PDFF in NAFLD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023, 58, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassas, M.; Mostafa, H.; Abdellatif, W.; Shoman, S.; Esmat, G.; Brahmania, M.; et al. Lubiprostone Reduces Fat Content on MRI-PDFF in Patients With MASLD: A 48-Week Randomised Controlled Trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025, 61, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, A.J.; Castera, L.; Wong, V.W.-S. Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Fibrosis in NAFLD. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023, 21, 2026–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Valenti, L.; Byrne, C.D. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. N Engl J Med. 2025, 393, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Z.; Fu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, C.; Yuan, M.; Gao, D. Associations Between Visceral and Liver Fat and Cardiac Structure and Function: A UK Biobank Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2025, 110, e1856–e1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlejohns, T.J.; Holliday, J.; Gibson, L.M.; Garratt, S.; Oesingmann, N.; Alfaro-Almagro, F.; et al. The UK Biobank imaging enhancement of 100,000 participants: rationale, data collection, management and future directions. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poynard, T.; Deckmyn, O.; Peta, V.; Sakka, M.; Lebray, P.; Moussalli, J.; et al. Clinical and genetic definition of serum bilirubin levels for the diagnosis of Gilbert syndrome and hypobilirubinemia. Hepatol Commun. 2023, 7, e0245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckmyn, O.; Poynard, T.; Bedossa, P.; Paradis, V.; Peta, V.; Pais, R.; et al. Clinical Interest of Serum Alpha-2 Macroglobulin, Apolipoprotein A1, and Haptoglobin in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, with and without Type 2 Diabetes, before or during COVID-19. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poynard, T.; Munteanu, M.; Charlotte, F.; Perazzo, H.; Ngo, Y.; Deckmyn, O.; et al. Diagnostic performance of a new noninvasive test for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis using a simplified histological reference. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018, 30, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poynard, T.; Lebray, P.; Ingiliz, P.; Varaut, A.; Varsat, B.; Ngo, Y.; et al. Prevalence of liver fibrosis and risk factors in a general population using non-invasive biomarkers (FibroTest). BMC Gastroenterol. 2010, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poynard, T.; Deckmyn, O.; Munteanu, M.; Ngo, Y.; Drane, F.; Castille, J.M.; et al. Awareness of the severity of liver disease re-examined using software-combined biomarkers of liver fibrosis and necroinflammatory activity. BMJ Open. 2015, 5, e010017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poynard, T.; Ratziu, V.; McHutchison, J.; Manns, M.; Goodman, Z.; Zeuzem, S.; et al. Effect of treatment with peginterferon or interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin on steatosis in patients infected with hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003, 38, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Yilmaz, Y.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Adithya Lesmana, C.R.; et al. Global burden of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, 2010 to 2021. JHEP Rep. 2025, 7, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raverdy, V.; Tavaglione, F.; Chatelain, E.; Lassailly, G.; De Vincentis, A.; Vespasiani-Gentilucci, U.; et al. Data-driven cluster analysis identifies distinct types of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Nat Med. 2024, 30, 3624–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poynard, T.; Munteanu, M.; Deckmyn, O.; Ngo, Y.; Drane, F.; Messous, D.; et al. Applicability and precautions of use of liver injury biomarker FibroTest. A reappraisal at 7 years of age. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.A.; Bedossa, P.; Guy, C.D.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Loomba, R.; Taub, R.; et al. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2024, 390, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratziu, V. Back to Byzance: Querelles byzantines over NASH and fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2017, 67, 1134–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadri, S.; Vartiainen, E.; Lahelma, M.; Porthan, K.; Tang, A.; Idilman, I.S.; et al. Marked difference in liver fat measured by histology vs. magnetic resonance-proton density fat fraction: A meta-analysis. JHEP Rep. 2024, 6, 100928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.-K.; Petta, S.; Noureddin, M.; Goh, G.B.B.; Wong, V.W.-S. Diagnosis and non-invasive assessment of MASLD in type 2 diabetes and obesity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024, 59, S23–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poynard, T.; Ratziu, V.; Naveau, S.; Thabut, D.; Charlotte, F.; Messous, D.; et al. The diagnostic value of biomarkers (SteatoTest) for the prediction of liver steatosis. Comp Hepatol. 2005, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratziu, V.; Giral, P.; Munteanu, M.; Messous, D.; Mercadier, A.; Bernard, M.; et al. Screening for liver disease using non-invasive biomarkers (FibroTest, SteatoTest and NashTest) in patients with hyperlipidaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007, 25, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Hu, P.; Hou, X.; Sun, Y.; Jiao, M.; Peng, L.; et al. Association between triglyceride-glucose related indices and mortality among individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024, 23, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castera L, Laouenan C, Vallet-Pichard A, Vidal-Trécan T, Manchon P, Paradis V, Roulot D, Gault N, Boitard C, Terris B, Bihan H, Julla JB, Radu A, Poynard T, Brzustowsky A, Larger E, Czernichow S, Pol S, Bedossa P, Valla D, Gautier JF; QUID-NASH investigators. High Prevalence of NASH and Advanced Fibrosis in Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Study of 330 Outpatients Undergoing Liver Biopsies for Elevated ALT, Using a Low Threshold. Diabetes Care. 2023, 46, 1354–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourati O, Manchon P, Garteiser P, Castera L, Burgio MD, Van Beers B, Bedossa P, Albuquerque M, Poynard T, Laouenan C, Valla D, Paradis, V.; QUID-NASHinvestigators Morphometric quantification of steatosis fibrosis in metabolic liver disease associated with type 2 diabetes Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025 Sep, 1.5.:.S.1.5.4.2.-3.5.6.5.(.2.5.).0.0.8.0.2.-X. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Context of use Reference |

UK-Biobank population-based cohort [10,11,14] |

QuidNash outpatients Type-2 Diabetes [3,4] | ||||||||

| Number participants with PDFF | 29,252 (100%) | 286 (100%) | ||||||||

| Prevalence steatosis % | ||||||||||

| PDFF Tiers cutoffs | S0 | S1A | S1B | S2 | S3 | S0 | S1A | S1B | S2 | S3 |

|

PDFF early steatosis 5-tier (0-<=3.2=S0/ <6.4=S1A/ <17.4=S1B/ <22.1=S2/ >=21.1=S3) |

53.6 | 26.1 | 16.6 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 6 | 45 | 19 | 30 |

| PDFF steatosis 4-tier (Kim 2023) (<6.4=S0/ <17.4=S1/ <22.1=S2/ >=22.1=S3 | 79.7 | 16.6 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 6.1 | 45 | 19 | 30 | ||

| SteatoTest/Fibrosure 4-tier (<= 0.38= S0/ <0.57=S1A/ <0.69=S2/ >0,69=S3) | NA | 9.8 | 28.7 | 40.6 | 21.0 | |||||

| Biopsy (4-tier CRN standard) | NA | 3.2 | 21.3 | 54.2 | 21.3 | |||||

| Phenotype characteristic % | ||||||||||

| Female sex % Female/Male | 51/ 49 | 41/ 59 | ||||||||

| Ethnicity % white | 100 | 80 | ||||||||

| Age years 5-tier % <40/ 50/ 60/ >70) | 1/ 29/ 48/ 22/ 0 | 20/ 20/ 27/ 26/ 7 | ||||||||

| % and cutoffs of Cardiometabolic risk factors according to recent MASLD nomenclature5 | ||||||||||

| Systolic blood pressure mmHg % >=130 | 53 | 56 | ||||||||

| Body mass index % >=25/m2 | 58 | 92 | ||||||||

| Triglycerides mmol/L (>= 1,7) | 19 | 43 | ||||||||

| HDL-cholesterol % (<= 1.0 mmol/L; 40mg/dL for male <= 1.3 mmol/L; 50mg/dL for female) | 33 female 27 male |

97 female 99 male |

||||||||

| Type-2 diabetes %, HbA1c >=5.7% or Glu >5.6 mmol/L | 12 | 100 | ||||||||

| Number of cardiovascular risk factors Median (range) |

2 (0 - 5) | 3 (1 - 5) | ||||||||

| MASLD Raverdy clusters 18 | Controls | Cardiometabolic SLD | ||||||||

| Mild or high alcohol intake % | 22 | 0 (excluded) | ||||||||

| Smoking % | 39 | 29 | ||||||||

| ApoA1 g/L median (IQR) | 1.63 (0.34) female 1.42 (0.29) male |

1.45 (0.28) female 1.29 (0.23) male |

||||||||

| Biopsy Steatosis CRN 4-tier % (0-<5=S0/ 5-<33=S1/ 33-<66=S2/ 66-100=S3 | NA | 21/ 54/ 21/ 4 | ||||||||

| Published subsets |

FibroFrance-CPAM [15] |

USA-Fibrosure [16] |

France- Fibrotest [16] |

FibroFrance-Group [14] |

Hepatitis C [17] |

| Context of use (number participants) | General Population (n=7,399) | Steatotic Liver Disease (n=72,026) | Steatotic Liver Disease (n=67,278) | Steatotic Liver Disease (n=1,081) |

Chronic hepatitis C (n=1,428) |

| Phenotype % (cutoffs) | |||||

| Sex (Female/Male) | 45/ 55 | 54/ 46 | 41/ 59 | 38/ 62 | 34/ 66 |

| Age years 5-tier (<40/ 50/ 60/ >70) | 43/ 33/ 13/ 11 | 18/ 29/ 21/ 32 | 39 /28 /15/ 18 | 21/ 30/ 22/ 27 | 15/ 59/ 11/ 15 |

| Ethnicity (white/ Other) | 45/ 55 | 54/ 46 | 41/ 59 | 38/ 62 | 34/ 66 |

| Steatosis Liver Disease risk factors % (cutoffs) | |||||

| Systolic blood pressure (>=130 mmHg) | 42 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Body mass index (>=25/m2 (23 for Asia) | 90 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Triglycerides g/L 4-tier <1/ 1-1.5/ 1.5-2.0 >2.5 | 43/ 33/ 13/ 11 | 18/ 29/ 21/ 32 | 39 /28 /15/ 18 | 21/ 30/ 22/ 27 | 15/ 59/ 11/ 15 |

| % HDL-cholesterol (<=1.0 mmol/L;40mg/dL male;<=1.3 mmol/L;50mg/dL female | 9 female 8 male |

NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Type-2 diabetes, HbA1c or Glu >=5.7% or >5.6 mmol/L | 26 | 51 | 35 | 40 | 23 |

| MASLD Clusters | Controls faire proxy HBA1c |

faire proxy LDL | faire proxy LDL | ||

| Mild or high alcohol intake % | 48 | NA | 15 | 12 | 34 |

| Smoking % | 18 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| ApoA1 (g/l) median (IQR) | 1.78 (0.37) female 1.59 (0.34) male |

1.49 (0.39) female 1.31 (0.33) male |

1.55 (0.43) female 1.37 (0.37) male |

1.47 (0.36) female 1.34 (0.33) male |

1.56 (0.32) female 1.33 (0.29) male |

| Prevalence steatosis % (cutoffs) | |||||

| SteatoTest/Fibrosure 4-tier<=0.38=S0/ <0.57=S1A/ <0.69=S2/ >0,69=S3 | 47/ 34/ 11/ 7 | 15/ 24/ 20/ 41 | 27/ 23/ 16/ 34 | 16/ 25/ 23/ 36 | 35/ 38/ 20/ 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).