Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

- An ad hoc sociodemographic questionnaire was administered to collect information on the participants’ age, hours of mobile phone and video game use, age at first mobile phone use, and gender.

- Cuestionario de Detección de Nuevas Adicciones, (DENA) [25]. This questionnaire was administered to assess video game use on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always) and demonstrates acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α 0.75).

- Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale in Adolescents (MPPUSA). To assess problematic mobile phone use, the Spanish adaptation of the questionnaire [26] was used. The MPPUSA consists of 27 items measured on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 10 (always). To determine types of mobile phone users, the following cut-off points were established: scores from 0 to 35 indicate occasional users, 36 to 173 regular users, 174 to 181 at-risk users, and 182 to 270 problematic users [26]. The scale shows excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α 0.97).

- Escala de Ansiedad Social para niños–Revised (SASC–R) [27] to assess social anxiety. The Spanish version of the scale consists of 18 items, with response options ranging from 1 (never) to 3 (often). The items are structured into three dimensions: Fear of Negative Evaluation (FNE) (items 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 14), Social Avoidance & Distress—Specific to New Peers (SAANP) (items 1, 3, 5, 8, 10, and 16), and Social Avoidance & Distress—General (SAGA) (items 12, 15, 17, and 18). The scale shows good reliability (Cronbach’s α 0.88).

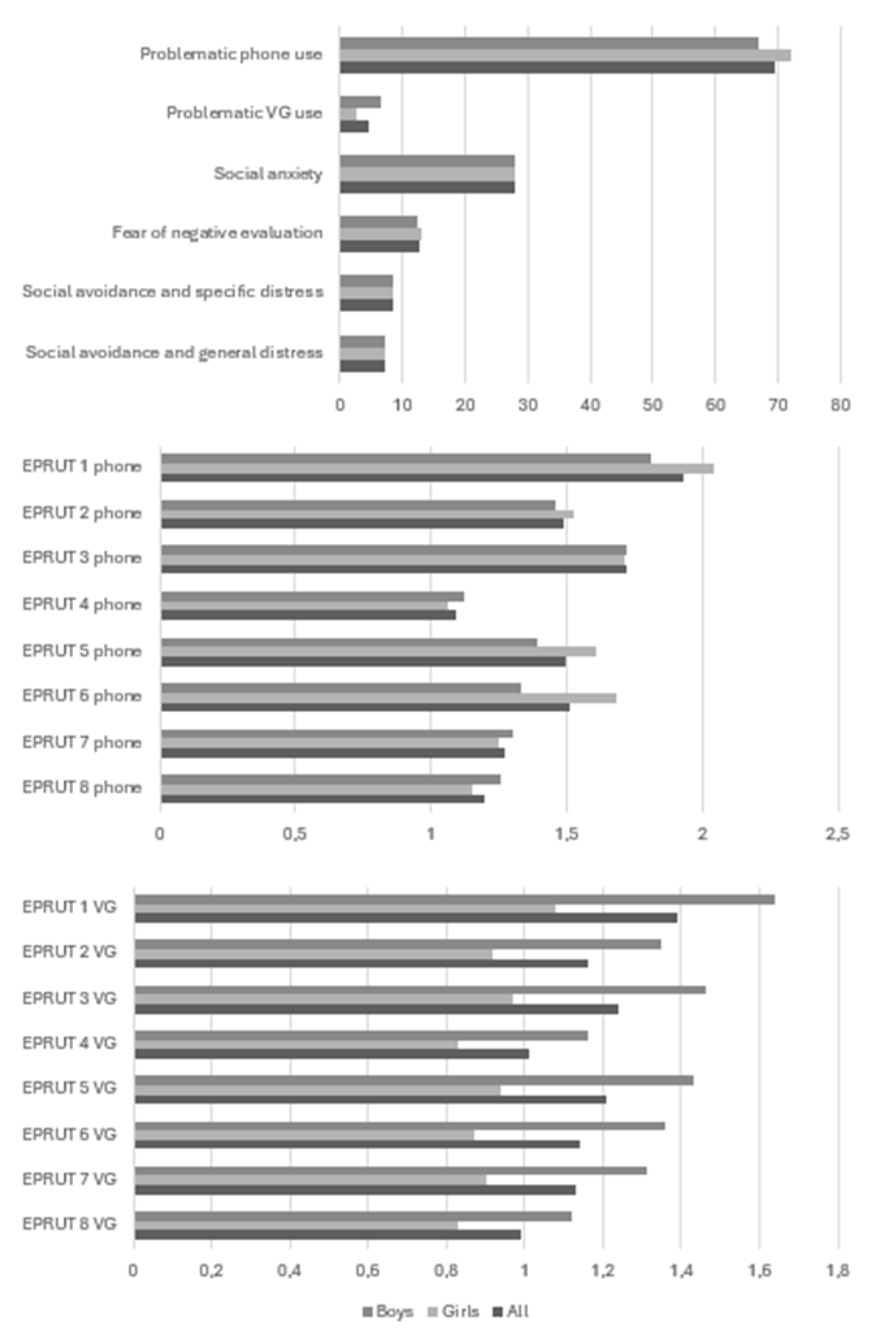

- Escala de percepción del riesgo para el uso de la tecnología en niños y adolescentes (EPRUT). [22]. This scale assesses the extent to which adolescents perceive certain risks related to mobile phone and video game use, such as going to bed later than you should; difficulty falling asleep; not finishing meals because of technology use; suffering violence such as fights or bullying; having less time for leisure activities such as sports, family and personal relationships; arguing with your parents; going out less with friends, and getting bad grades or not doing homework. EPRUT is measured on a 16-item Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (a lot). The reliability coefficient of the EPRUT is 0.84 (Cronbach’s alpha).

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Lines of Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Menéndez-García A, Jiménez-Arroyo A, Rodrigo-Yanguas M, Marín-Vila M, Sánchez-Sánchez F, Roman-Riechmann E, et al. Adicción a Internet, videojuegos y teléfonos móviles en niños y adolescentes: un estudio de casos y controles. Adicciones. 2022, 34, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno CR, Cuenca Peláez KF, Cool Cedeño D, España Murillo León M. El impacto de la tecnología en la vida social de los adolescentes. Rev Estud Gener. 2025, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virós-Martín C, Montaña-Blasco M, Jiménez-Morales M. Can’t stop scrolling! Adolescents’ patterns of TikTok use and digital well-being self-perception. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2024, 11, 1444. [CrossRef]

- Alanko, D. The health effects of video games in children and adolescents. Pediatr Rev. 2023, 44, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilali A, Katsiroumpa A, Koutelekos I, Dafogianni C, Gallos P, Moisoglou I, et al. Association between TikTok use and anxiety, depression, and sleepiness among adolescents: a cross-sectional study in Greece. Pediatr Rep. 2025, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granic I, Lobel A, Engels RCME. The benefits of playing video games. Am Psychol. 2014, 69, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter M, Braun T, Mack W. Social context and gaming motives predict mental health better than time played: an exploratory regression analysis with over 13,000 video game players. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2021, 24, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma K, Sarathamani T, Bhougal SK, Singh HK. Smartphone-induced behaviour: utilisation, benefits, nomophobic behaviour and perceived risks. J Creat Commun. 2021, 17, 336–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei J, Dang J, Mi Y, Zhou M. Mobile phone addiction and social anxiety among Chinese adolescents: mediating role of interpersonal problems. An Psicol. 2024, 40, 103–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virós-Martín C, Montaña-Blasco M, Jiménez-Morales M. Can’t stop scrolling! Adolescents’ patterns of TikTok use and digital well-being self-perception. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2024, 11, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Arenas MP, García-Rojas AD, Hernando Gómez A, Prieto Medel C. Percepción del riesgo de los menores ante el uso de las tecnologías: influencia de diferentes variables. Rotura - Rev Comun Cult Artes. 2025, (Especial Alfamed), 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaltout N. Investigating the risk and protective factors of Internet addiction among adolescents through the lens of cognitive behavioral theory: a cross-sectional study [master’s Thesis]. Cairo: The American University in Cairo; 2025. Disponible en: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/2373.

- Gioia F, Mariano Colella G, Boursier V. Evidence on problematic online gaming and social anxiety over the past ten years: a systematic literature review. Curr Addict Rep. 2022, 9, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino C, Canale N, Vieno A, Caselli G, Scacchi L, Spada MM. Social anxiety and internet gaming disorder: the role of motives and metacognitions. J Behav Addict. 2020, 9, 617–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcellos RP, Sanders T, Lonsdale C, Parker P, Conigrave J, Tang S, et al. Electronic screen use and children’s socioemotional problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2025, 151, 513–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Children and Youth Planning Table of Waterloo Region, Browne D. Digital media use, social isolation, and mental health symptoms in Canadian youth: a psychometric network analysis. Can J Behav Sci 2025. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Feng N, Cui L. Network analysis of social anxiety and problematic mobile phone use in Chinese adolescents: a longitudinal study. Addict Behav. 2024, 155, 108026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, Jiang H, Zhang B, Liang H. Social anxiety, maladaptive cognition, mobile phone addiction, and perceived social support: a moderated mediation model. J Psychol Afr. 2021, 31, 248–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales (DSM-5). 5.ª ed. Madrid: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2022.

- Vázquez, M. Videojuegos: una perspectiva desde la personalidad y el trastorno de ansiedad social. Rev Psicol Sin Fronteras. 2023, 6, 93–7. [Google Scholar]

- Plessis C, Guerrien A, Altintas E. Sociotropy and video game playing: massively multiplayer online role-playing games versus other games. Encephale, 2025; S0013-7006(24)00123-5. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Olivares R, Casas JA, Lucena V, Aguilar-Yamuza B. Propiedades psicométricas de la “Escala de percepción del riesgo del uso de la tecnología para niños y adolescentes”. Behav Psychol Psicol Conductual. 2024, 32, 203–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro B, Beranuy M, Vega MA, Calvo F, Carbonell X. Uso problemático del móvil y diferencias de género en formación profesional. Educ XX1. 2022, 25, 271–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu X, Li H, Bai R, Liu Q. Do boys and girls display different levels of depression in response to mobile phone addiction? Examining the longitudinal effects of four types of mobile phone addiction. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024, 17, 4329–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrador FJ, Villadangos SM, Crespo M, Becoña E. Desarrollo y validación del cuestionario de uso problemático de nuevas tecnologías (UPNT). An Psicol. 2013, 29, 836–47. [Google Scholar]

- López-Fernández O, Honrubia-Serrano ML, Freixa-Blanxart M. Adaptación española del “Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale” para población adolescente. Adicciones. 2012;24(2):123-30. Chorot P, Valiente RM, Santed Germán MA, Sánchez-Arribas C. Estructura factorial de la escala de ansiedad social para niños-revisada (SASC-R). RPPC [Internet]. 1 de mayo de 1999 [citado 18 de septiembre de 2025];4(2):105-13. Disponible en: https://revistas.uned.es/index.php/RPPC/article/view/3876. [CrossRef]

| Mobile | Video games | |||||

| Hours | Boys | Girls | Total | Boys | Girls | Total |

| 0 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 13.7 | 7 |

| 1 | 34.8 | 29.1 | 31.4 | 35 | 33.7 | 33.6 |

| 2 | 20.4 | 17 | 18.3 | 19.3 | 17.6 | 18 |

| 3 | 16.7 | 14.7 | 15.8 | 23.7 | 16.1 | 19.9 |

| 4 | 9.1 | 13.3 | 11 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 6.9 |

| 5 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.9 |

| 6 o more | 11.3 | 18.2 | 15.8 | 10.5 | 8.4 | 10.7 |

| Problematic Mobile Phone Use | |||

| Boys | Girls | Total | |

| Problematic Video Game Use | .621** | .156** | .383** |

| Age | .232** | .402** | .315** |

| Social anxiety | .370** | .388** | .386** |

| Fear of negative evaluation | .416** | .353** | .389** |

| Social avoidance and specific anxiety | .293** | .449** | .381** |

| Social avoidance and general anxiety | -.006 | -.048 | -.015 |

| Going to bed later than you should (mobile phone) | .514** | .599** | .568** |

| Difficulty falling asleep (mobile phone) | .444** | .480** | .471** |

| Not finishing your meal or eating more slowly... (mobile phone) | .435** | .316** | .388** |

| Being subjected to violence such as fights, bullying... (mobile phone) | .364** | .141* | .281** |

| Having less time to do your activities... (mobile phone) | .341** | .365** | .357** |

| Arguing with your parents (mobile phone) | .356** | .537** | .454** |

| Going out less with your friends (mobile phone) | .275** | .177** | .213** |

| Getting bad grades or not doing your homework... (mobile phone) | .361** | .439** | .400** |

| Problematic Video Game Use | |||

| Boys | Girls | Total | |

| Problematic Mobile Phone Use | .621** | .156** | .383** |

| Age | .011 | -.212** | -.091* |

| Social anxiety | .341** | .173** | .244** |

| Fear of negative evaluation | .353** | .123* | .199** |

| Social avoidance and specific distress | .214** | -.018 | .125** |

| Social avoidance and general distress | .058 | .227** | .138** |

| Going to bed later than you should (video game) | .450** | .377** | .456** |

| Falling asleep difficulty (video game) | .431** | .299** | .451** |

| Not finishing your meal or eating more slowly... (Video Game) | .227** | .220** | .258** |

| Being subjected to violence such as fights, bullying... (video game) | .273** | .080 | .265** |

| Having less time to do your activities... (video game) | .311** | .257** | .338** |

| Arguing with your parents (video game) | .319** | .343** | .352** |

| Going out less with your friends (video game) | .255** | .362** | .309** |

| Getting bad grades or not doing your homework... (video game) | .292** | .234** | .311** |

| *p < .05; **p < .01 | |||

| Problematic Mobile Phone Use | ||||||

| Boys | Girls | |||||

| β | t | p | β | t | p | |

| Problematic Video Game Use | 6.664 | 7.050 | <.001 | 1.870 | 3.182 | <.01 |

| Age | ||||||

| Social anxiety | 1.911 | 4.711 | <.001 | 1.084 | 2.848 | <.01 |

| Fear of negative evaluation | ||||||

| Social avoidance and specific distress | 2.611 | 3.063 | <.01 | |||

| Social avoidance and general distress | -2.371 | -2.785 | <.01 | |||

| Going to bed later... (mobile phone) | 10.164 | 5.004 | <.001 | |||

| Difficulty falling asleep (mobile phone) | 5.364 | 3.045 | <.01 | |||

| Not finishing meals... (mobile phone) | 7.594 | 4.673 | <.001 | |||

| Being subjected to violence such as... (mobile phone) | ||||||

| Having less time to... (mobile phone) | ||||||

| Arguing with your parents (mobile phone) | 7.324 | 3.374 | <.001 | |||

| Going out less with your friends (mobile phone) | -2.765 | -1.948 | .053 | -7.633 | -3.820 | <.001 |

| Getting bad grades or not... (mobile phone) | 11.863 | 4.465 | <.001 | |||

| R2=.587 | R2=.630 | |||||

| Problematic Video Game Use | ||||||

| Boys | Girls | |||||

| β | t | p | β | t | p | |

| Problematic Mobile Phone Use | .060 | 8.125 | <.001 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| Social anxiety | ||||||

| Fear of negative evaluation | .221 | 2.810 | <.01 | |||

| Social avoidance and specific distress | ||||||

| Social avoidance and general distress | .163 | 1.698 | .092 | |||

| Going to bed later... (video game) | .901 | 3.042 | <.01 | 1.046 | 2.064 | <.05 |

| Difficulty falling asleep (video game) | ||||||

| Not finishing your meal... (video game) | -.394 | -1.777 | .078 | |||

| Being subjected to violence such as... (video game) | -.601 | -2.006 | <.01 | -1.346 | -2.757 | <.01 |

| Having less time to... (video game) | ||||||

| Arguing with your parents (video game) | .839 | 1.307 | .193 | |||

| Going out less with your friends (video game) | 1.873 | 3.236 | <.01 | |||

| Getting bad grades or not... (video game) | .877 | 2.858 | <.01 | -2.073 | -3.245 | <.001 |

| R2=.556 | R2=.259 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).