Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

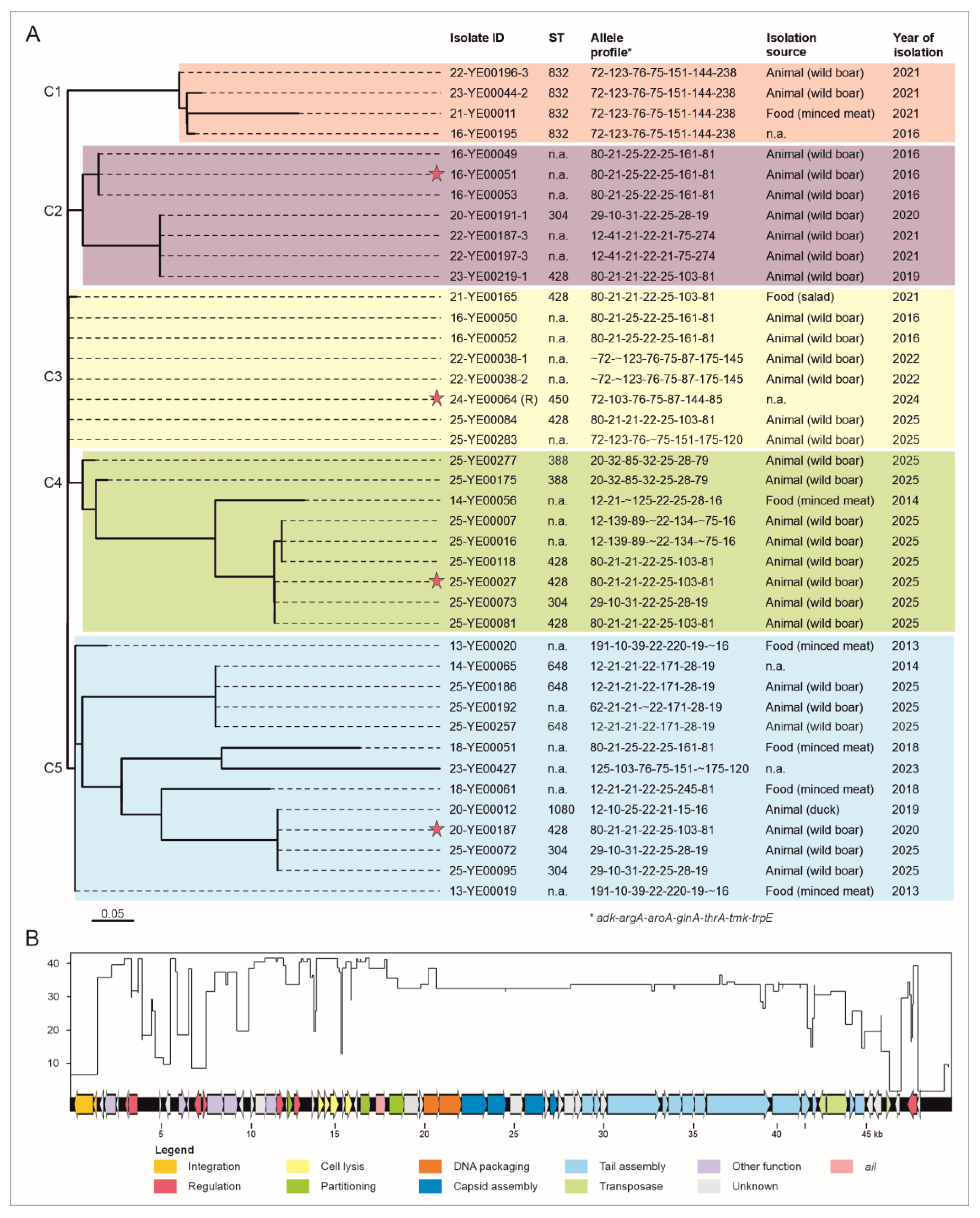

2.1. Forty-One Out of 370 BT 1A Genomes Contain a Prophage-Associated Ail Gene.

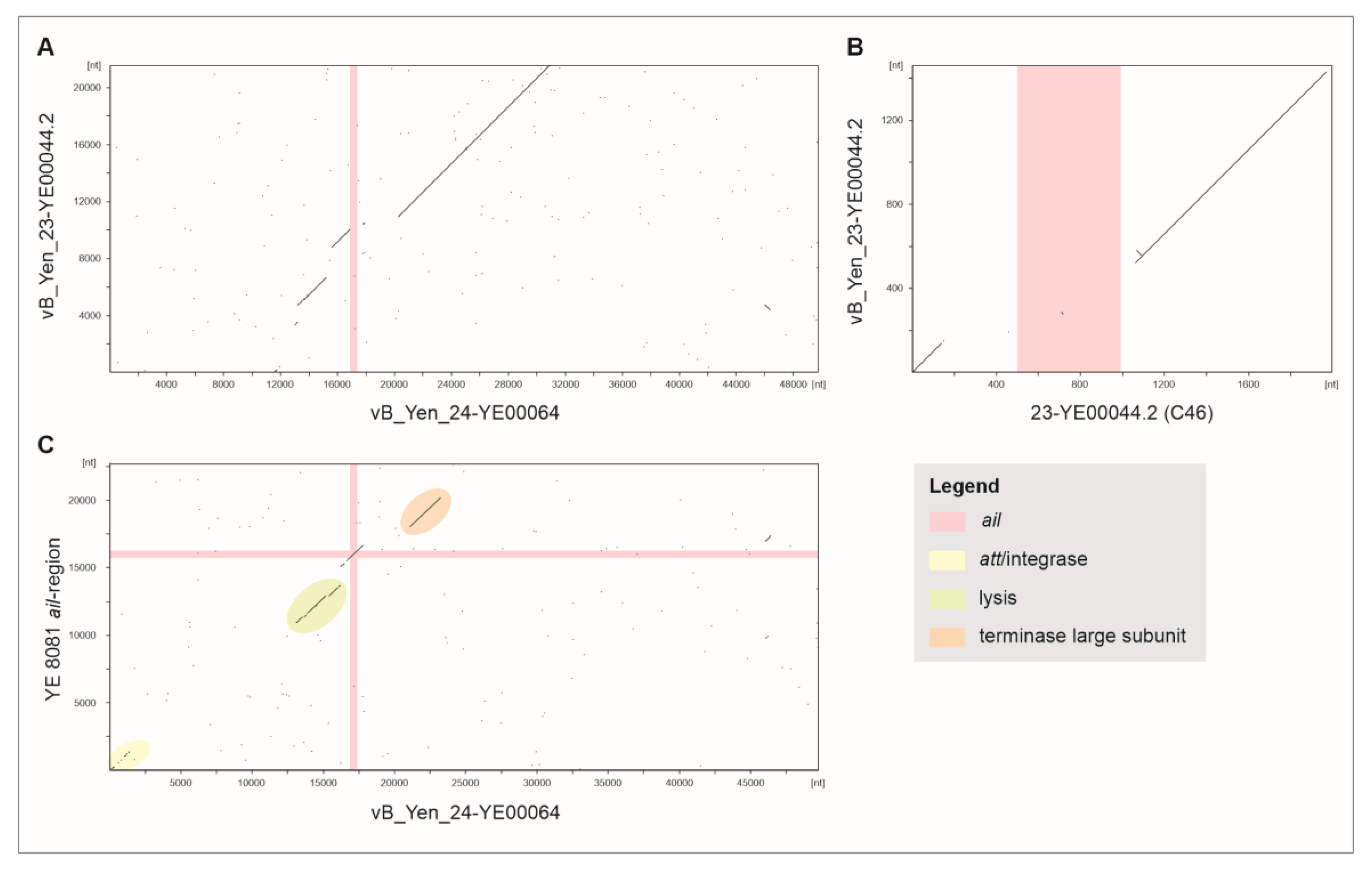

2.2. Comparison of the Prophages Indicates Relationships Between Them.

2.3. Relocation of ail in Cluster C1 and Analysis of 1B/O:8 Strains.

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Typing of Y. enterocolitica Strains.

4.2. Genome Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

4.3. Genome Accession Numbers

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carniel, E. 2001. The Yersinia high-pathogenicity island: an iron-uptake island. Microbes Infect 3:561-9.

- panel) EFSAB. 2007. Monitoring and identification of human enteropathogenic Yersinia spp. ESFA Journal (2007) 595:1-30.

- Boqvist S, Pettersson H, Svensson A, Andersson Y. 2009. Sources of sporadic Yersinia enterocolitica infection in children in Sweden, 2004: a case-control study. Epidemiol Infect 137:897-905.

- Centorame P, Sulli N, De Fanis C, Colangelo OV, De Massis F, Conte A, Persiani T, Marfoglia C, Scattolini S, Pomilio F, Tonelli A, Prencipe VA. 2017. Identification and characterization of Yersinia enterocolitica strains isolated from pig tonsils at slaughterhouse in Central Italy. Vet Ital 53:331-344.

- Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Korte T, Korkeala H. 2000. Contamination of carcasses, offals, and the environment with yadA-positive Yersinia enterocolitica in a pig slaughterhouse. J Food Prot 63:31-5.

- Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Korte T, Korkeala H. 2001. Transmission of Yersinia enterocolitica 4/O:3 to pets via contaminated pork. Lett Appl Microbiol 32:375-8.

- Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Stolle A, Korkeala H. 2006. Molecular epidemiology of Yersinia enterocolitica infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 47:315-29.

- Ostroff SM, Kapperud G, Hutwagner LC, Nesbakken T, Bean NH, Lassen J, Tauxe RV. 1994. Sources of sporadic Yersinia enterocolitica infections in Norway: a prospective case-control study. Epidemiol Infect 112:133-41.

- Tauxe RV, Vandepitte J, Wauters G, Martin SM, Goossens V, De Mol P, Van Noyen R, Thiers G. 1987. Yersinia enterocolitica, 1: and pork: the missing link. Lancet 1, 1129.

- Platt-Samoraj A, Syczylo K, Szczerba-Turek A, Bancerz-Kisiel A, Jablonski A, Labuc S, Pajdak J, Oshakbaeva N, Szweda W. 2017. Presence of ail and ystB genes in Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 1A isolates from game animals in Poland. Vet J 221:11-13.

- Joutsen S, Johansson P, Laukkanen-Ninios R, Bjorkroth J, Fredriksson-Ahomaa M. 2020. Two copies of the ail gene found in Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia kristensenii. Vet Microbiol 247:108798.

- Le Guern AS, Martin L, Savin C, Carniel E. 2016. Yersiniosis in France: overview and potential sources of infection. Int J Infect Dis 46:1-7.

- Kirjavainen V, Jarva H, Biedzka-Sarek M, Blom AM, Skurnik M, Meri S. 2008. Yersinia enterocolitica, e: proteins YadA and ail bind the complement regulator C4b-binding protein. PLoS Pathog 4, 1000.

- Thomson JJ, Plecha SC, Krukonis ES. 2019. Ail provides multiple mechanisms of serum resistance to Yersinia pestis. Mol Microbiol 111:82-95.

- Miller VL, Beer KB, Heusipp G, Young BM, Wachtel MR. 2001. Identification of regions of Ail required for the invasion and serum resistance phenotypes. Mol Microbiol 41:1053-62.

- Kraushaar B, Dieckmann R, Wittwer M, Knabner D, Konietzny A, Made D, Strauch E. 2011. Characterization of a Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 1A strain harbouring an ail gene. J Appl Microbiol 111:997-1005.

- Sihvonen LM, Jalkanen K, Huovinen E, Toivonen S, Corander J, Kuusi M, Skurnik M, Siitonen A, Haukka K. 2012. Clinical isolates of Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 1A represent two phylogenetic lineages with differing pathogenicity-related properties. BMC Microbiol 12:208.

- Hunter E, Greig DR, Schaefer U, Wright MJ, Dallman TJ, McNally A, Jenkins C. 2019. Identification and typing of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis isolated from human clinical specimens in England between 2004 and 2018. J Med Microbiol 68:538-548.

- McNally A, Cheasty T, Fearnley C, Dalziel RW, Paiba GA, Manning G, Newell DG. 2004. Comparison of the biotypes of Yersinia enterocolitica isolated from pigs, cattle and sheep at slaughter and from humans with yersiniosis in Great Britain during 1999-2000. Lett Appl Microbiol 39:103-8.

- McNally A, Dalton T, Ragione RM, Stapleton K, Manning G, Newell DG. 2006. Yersinia enterocolitica, 1: of differing biotypes from humans and animals are adherent, invasive and persist in macrophages, but differ in cytokine secretion profiles in vitro. J Med Microbiol 55, 1725.

- Rivas L, Horn B, Armstrong B, Wright J, Strydom H, Wang J, Paine S, Thom K, Orton A, Robson B, Lin S, Wong J, Brunton C, Smith D, Cooper J, Mangalasseril L, Thornley C, Gilpin B. 2024. A case-control study and molecular epidemiology of yersiniosis in Aotearoa New Zealand. J Clin Microbiol 62:e0075424.

- Rivas L, Strydom H, Paine S, Wang J, Wright J. 2021. Yersiniosis in New Zealand. Pathogens 10.

- Stephan R, Joutsen S, Hofer E, Sade E, Bjorkroth J, Ziegler D, Fredriksson-Ahomaa M. 2013. Characteristics of Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 1A strains isolated from patients and asymptomatic carriers. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 32:869-75.

- Clarke M, Dabke G, Strakova L, Jenkins C, Saavedra-Campos M, McManus O, Paranthaman K. 2020. Introduction of PCR testing reveals a previously unrecognized burden of yersiniosis in Hampshire, UK. J Med Microbiol 69:419-426.

- Colbran C, May F, Alexander K, Hunter I, Stafford R, Bell R, Cowdry A, Vosti F, Jurd S, Graham T, Micalizzi G, Graham R, Slinko V. 2024. Yersiniosis outbreaks in Gold Coast residential aged care facilities linked to nutritionally-supplemented milkshakes, January-23. Commun Dis Intell (2018) 48. 20 April.

- Horn BP, I.; Cressey, P.; Armstrong, B.; Lopez, L. 2023. Annual report concerning Foodborne Diseases in New Zealand 2022. New Zealand Food Safety Technical Paper No: 2023/17.

- Platt-Samoraj, A. 2022. Toxigenic Properties of Yersinia enterocolitica Biotype 1A. Toxins (Basel) 14.

- Kolodziejek AM, Hovde CJ, Minnich SA. 2012. Yersinia pestis, 1: roles of a single protein. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2.

- Stevens MJA, Horlbog JA, Diethelm A, Stephan R, Nuesch-Inderbinen M. 2024. Characteristics and comparative genome analysis of Yersinia enterocolitica and related species associated with human infections in Switzerland 2019-2023. Infect Genet Evol 123:105652.

- Sihvonen LM, Hallanvuo S, Haukka K, Skurnik M, Siitonen A. 2011. The ail gene is present in some Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 1A strains. Foodborne Pathog Dis 8:455-7.

- Hammerl JA, Barac A, Jackel C, Fuhrmann J, Gadicherla A, Hertwig S. 2022. Phage vB_YenS_P400, a Novel Virulent Siphovirus of Yersinia enterocolitica Isolated from Deer. Microorganisms 10.

- Popp A, Hertwig S, Lurz R, Appel B. 2000. Comparative study of temperate bacteriophages isolated from Yersinia. Syst Appl Microbiol 23:469-78.

- Wauters G, Kandolo K, Janssens M. 1987. Revised biogrouping scheme of Yersinia enterocolitica. Contrib Microbiol Immunol 9:14-21.

- Hammerl JA, Klein I, Lanka E, Appel B, Hertwig S. 2008. Genetic and functional properties of the self-transmissible Yersinia enterocolitica plasmid pYE854, which mobilizes the virulence plasmid pYV. J Bacteriol 190:991-1010.

- Hammerl JA, Rivas L, Cornelius A, Manta D, Hertwig S. 2025. The beta-glucosidase gene for esculin hydrolysis of Yersinia enterocolitica is a suitable target for the detection of biotype 1A strains by polymerase chain reaction. J Appl Microbiol 136.

- Brauer JA, Hammerl JA, El-Mustapha S, Fuhrmann J, Barac A, Hertwig S. 2023. The Novel Yersinia enterocolitica Telomere Phage vB_YenS_P840 Is Closely Related to PY54, but Reveals Some Striking Differences. Viruses 15.

- Hammerl JA, Barac A, Erben P, Fuhrmann J, Gadicherla A, Kumsteller F, Lauckner A, Muller F, Hertwig S. 2021. Properties of Two Broad Host Range Phages of Yersinia enterocolitica Isolated from Wild Animals. Int J Mol Sci 22.

- Hammerl JA, El-Mustapha S, Bolcke M, Trampert H, Barac A, Jackel C, Gadicherla AK, Hertwig S. 2022. Host Range, Morphology and Sequence Analysis of Ten Temperate Phages Isolated from Pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica Strains. Int J Mol Sci 23.

- Deneke C, Brendebach H, Uelze L, Borowiak M, Malorny B, Tausch SH. 2021. Species-Specific Quality Control, Assembly and Contamination Detection in Microbial Isolate Sequences with AQUAMIS. Genes (Basel) 12.

| Element | Start | Stop | Strand | Predicted function | Accession | E-value |

| ORF01 | 1229 | 147 | - | Phage integrase | WP_339099454 | 0 |

| ORF02 | 1473 | 1204 | - | Phage excisionase | WP_032819545 | 9,65E-58 |

| ORF03 | 1850 | 1548 | - | Unknown | WP_050123456 | 9,16E-67 |

| ORF04 | 2496 | 1873 | - | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | WP_050123460 | 8,2E-151 |

| ORF05 | 2676 | 2506 | - | Unknown | WP_219644695 | 8,92E-32 |

| ORF06 | 3206 | 3033 | - | Phage CIII repressor | CNH66013 | 3,38E-33 |

| ORF07 | 3745 | 3230 | - | Phage AntA/AntB antirepressor | EKN4711341 | 3,1E-123 |

| ORF08 | 4959 | 5075 | + | Unknown | - | - |

| ORF09 | 5588 | 5280 | - | Unknown | WP_219644503 | 9,54E-66 |

| ORF10 | 6039 | 6506 | + | Phage super-infection exclusion protein B | EKN5118889 | 1,6E-107 |

| ORF11 | 6667 | 6509 | - | Unknown | WP_400175511 | 2,44E-28 |

| ORF12 | 7338 | 6916 | - | Phage CI-like repressor | WP_219649054 | 6,25E-98 |

| ORF13 | 7442 | 7699 | + | Phage Cro/Cl family transcriptional regulator | WP_151432101 | 1,28E-56 |

| ORF14 | 7686 | 8636 | + | DNA-binding protein | WP_258018631 | 0 |

| ORF15 | 8626 | 9372 | + | Replisome organizer | EKN4711333 | 0 |

| ORF16 | 9741 | 9454 | - | Unknown | WP_400175508 | 1,3E-63 |

| ORF17 | 10129 | 10335 | + | Unknown | WP_050123484 | 5,88E-40 |

| ORF18 | 10421 | 11020 | + | Unknown | EKN4711330 | 1,3E-143 |

| ORF19 | 11020 | 11592 | + | Phage NinG rap recombination | WP_400175506 | 3,3E-138 |

| ORF20 | 11592 | 12005 | + | Phage antitermination protein Q | WP_219648280 | 6,23E-97 |

| ORF21 | 12185 | 12090 | - | Unknown | EHB0983027 | 0,008902 |

| ORF22 | 12226 | 12510 | + | Type II toxin-antitoxin system (RelE/ParE family) | EKN5956923 | 3,7E-59 |

| ORF23 | 12583 | 12957 | + | Transcriptional regulator | WP_050162972 | 1,09E-84 |

| tRNA01 | 13325 | 13400 | + | tRNA-Thr-CGT | ||

| tRNA02 | 13402 | 13476 | + | tRNA-Gly-TCC | ||

| ORF24 | 13653 | 13772 | + | Unknown | WP_144405165 | 9,81E-16 |

| ORF25 | 13925 | 14320 | + | Phage holin | WP_050123331 | 3,02E-88 |

| ORF26 | 14320 | 14616 | + | Phage holin family protein | WP_219647003 | 1,4E-62 |

| ORF27 | 14603 | 15145 | + | Phage lysozyme (N-acetylmuramidase) family | HDL7801217 | 1,6E-125 |

| ORF28 | 15305 | 15418 | + | Unknown | WP_219644478 | 1,2E-15 |

| ORF29 | 15474 | 15869 | + | Phage endopeptidase Rz | EKN4799071 | 3,51E-87 |

| ORF30 | 16181 | 15999 | - | Unknown | SRY18578 | 1,42E-06 |

| ORF31 | 16338 | 16895 | + | KilA-N domain-containing protein | WP_219644727 | 9,9E-132 |

| ORF32 | 17202 | 17738 | + | Attachment invasion locus protein Ail | WP_219647006 | 4E-126 |

| ORF33 | 17951 | 18820 | + | Chromosome (plasmid) partitioning protein ParB | CNF12705 | 0 |

| ORF34 | 18813 | 19685 | + | Unknown | WP_050130101 | 0 |

| ORF35 | 19670 | 19918 | + | Unknown | WP_050130103 | 9,51E-50 |

| ORF36 | 19922 | 20788 | + | Phage terminase, small subunit | WP_258018632 | 0 |

| ORF37 | 20766 | 22070 | + | Phage terminase, large subunit | WP_050123349 | 0 |

| ORF38 | 22075 | 23487 | + | DNA-binding protein | WP_050123375 | 0 |

| ORF39 | 23492 | 24604 | + | Phage head morphogenesis protein | ELI7924874 | 0 |

| ORF40 | 24795 | 25547 | + | Unknown | WP_151431638 | 9,3E-180 |

| ORF41 | 25602 | 26747 | + | Phage major capsid protein | WP_242365527 | 0 |

| ORF42 | 26814 | 27002 | + | Unknown | WP_219647076 | 1,39E-34 |

| ORF43 | 27014 | 27496 | + | DnaT-like ssDNA-binding protein | WP_050123385 | 1,4E-114 |

| ORF44 | 27500 | 27853 | + | Unknown | WP_050123386 | 6,52E-79 |

| ORF45 | 27856 | 28446 | + | Unknown | WP_151431635 | 1E-141 |

| ORF46 | 28443 | 28862 | + | Unknown | WP_050123389 | 4,56E-98 |

| ORF47 | 28880 | 29542 | + | Phage tail protein | WP_050123390 | 1,4E-159 |

| ORF48 | 29565 | 29921 | + | Phage tail assembly chaperone | WP_050123392 | 1,56E-80 |

| ORF49 | 29924 | 30235 | + | Unknown | WP_373368631 | 6,9E-70 |

| ORF50 | 30232 | 33339 | + | Phage tail, tail length tape-measure protein H | WP_219651824 | 0 |

| ORF51 | 33412 | 33753 | + | Phage tail tip, assembly protein M | WP_050123394 | 1,7E-77 |

| ORF52 | 33762 | 34514 | + | Phage tail tip, assembly protein L | WP_219654916 | 0 |

| ORF53 | 34517 | 35233 | + | Phage tail tip, assembly protein K | MFM1259745 | 8,9E-178 |

| ORF54 | 35233 | 35838 | + | Phage tail tip, assembly protein I | MFM1259744 | 9,4E-141 |

| ORF55 | 35851 | 39552 | + | Phage tail tip, host specificity protein J | MFM1259743 | 0 |

| ORF56 | 39619 | 41256 | + | Phage tail fiber protein | WP_289823745 | 0 |

| ORF57 | 41256 | 41783 | + | Phage tail fiber assembly protein | MFM1259741 | 8,3E-124 |

| ORF58 | 41881 | 42189 | + | Phage tail fiber protein | WP_400175531 | 8,95E-65 |

| ORF59 | 42650 | 42225 | - | Transposase | WP_050132355 | 3,3E-98 |

| ORF60 | 42708 | 43871 | + | Transposase | WP_400175835 | 0 |

| ORF61 | 43997 | 44314 | + | Phage tail fiber protein | MFJ1219555 | 1,36E-65 |

| ORF62 | 44321 | 44884 | + | Phage tail fiber assembly protein | WP_050162967 | 1,7E-135 |

| ORF63 | 45339 | 44956 | - | Unknown | WP_032820973 | 1,07E-84 |

| ORF64 | 45809 | 45339 | - | Unknown | WP_004392760 | 6,9E-111 |

| ORF65 | 46078 | 46362 | + | Transposase, IS3/IS911 family | AJI84358 | 1,41E-55 |

| ORF66 | 46856 | 46572 | - | Unknown | WP_050123427 | 9,42E-62 |

| ORF67 | 47840 | 47244 | - | Phage antirepressor protein | WP_339099468 | 7,8E-142 |

| ORF68 | 48028 | 47837 | - | Unknown | WP_032820969 | 3,09E-37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).