1. Introduction

Extensive research has been conducted globally to identify the causes of concrete deterioration and develop effective countermeasures. However, studies focusing on repair methods and materials that proactively address deterioration remain comparatively limited. Among the various repair materials, aluminate-based binders, such as calcium sulfoaluminate (CSA) and amorphous calcium aluminate (ACA) cements, have been extensively investigated for their potential to enhance both the mechanical performance and durability of concrete structures, yielding significant research outcomes to date [

1,

2].

CSA cement, primarily manufactured from bauxite, limestone, and gypsum, was first developed in the 1960s. Thenceforth, CSA has been widely utilized as a shrinkage-compensating additive and, in some countries, as an expansive binder owing to the expansive properties of ye’elimite (3CaO

3·Al

2O

3·CaSO

4) present in CSA [

3,

4]. Owing to its rapid setting, quick strength development, and slight expansion, CSA is particularly well suited for rapid repair applications, such as mitigating microcracks in bridge expansion joints [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Research on CSA has addressed the strength, durability, hydration reactions, and hydration modeling of the material [

9,

10,

11]. For example, Coumes et al. [

3] demonstrated that hydration of CSA is accelerated by an increased nucleation rate, thereby enhancing early strength development. Additionally, Chen et al. [

5] elucidated the correlation between alkalinity in pore solution and AFt formation.

ACA cement, primarily composed of C

12A

7 with an alumina content of approximately 40–50%, is characterized by the formation of substantial quantities of needle-like AFt and C

2AH

8 during hydration, resulting in rapid setting [

12]. When combined with ordinary Portland cement (OPC), the presence of Ca(OH)

2 moderates the setting rate, thereby enhancing workability. Additionally, the incorporation of anhydrite accelerates hydration, making ACA suitable for shotcrete applications and rapid repair of concrete structures.

In this study, repair mortars (RM) were formulated by partially replacing OPC with CSA and ACA. The mechanical performance of these mortars was evaluated through measurements of fluidity, setting time, mechanical strength, and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV). Paste samples containing aluminate-based binders (CSA and ACA) were further analyzed to identify hydration products using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and to investigate microstructural characteristics using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Furthermore, freeze–thaw resistance tests were conducted to determine the suitability of these RMs for use in cold climates and winter conditions. The experimental results are anticipated to provide valuable insights for selecting the optimal repair materials for deteriorated concrete structures.

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Materials

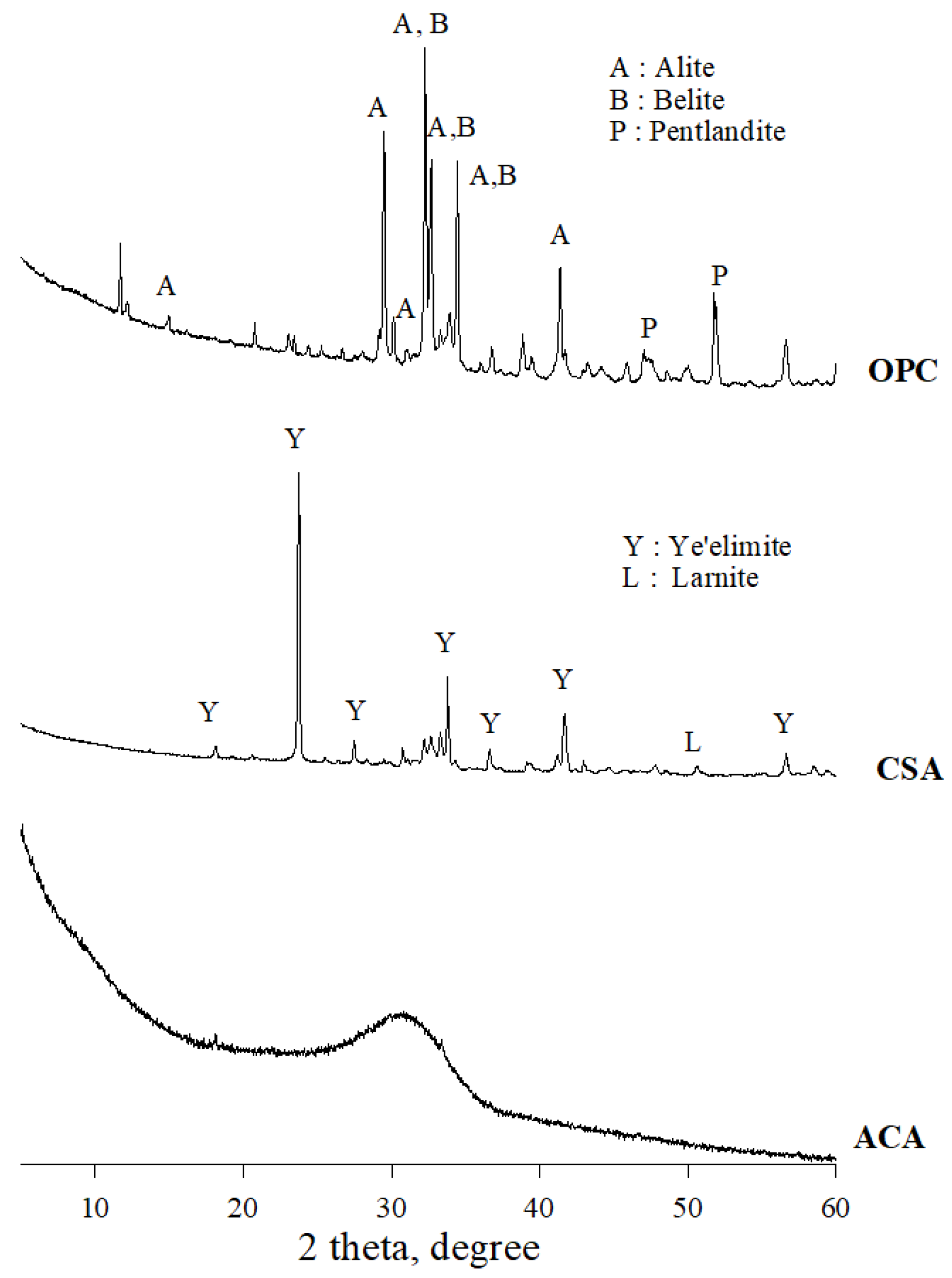

The binders utilized in this study were OPC conforming to ASTM C150, CSA cement, and ACA cement. To accelerate hydration, anhydrite gypsum (AG) was incorporated in varying proportions depending on the mixture. The chemical compositions of the binders are listed in

Table 1, and their XRD patterns are shown in

Figure 1. As indicated by the XRD results, CSA comprises primarily crystalline ye’elimite, whereas ACA cement is predominantly amorphous C

12A

7 [

13].

2.2. Mix Proportions

Six RM mixtures were formulated, as detailed in

Table 2. The RMC-1 mixture was prepared by substituting 25% of OPC with CSA and AG. In RMC-2, 40% CSA and 30% AG replaced OPC. The RMA-1 mixture incorporated 25% ACA and AG as OPC replacements, whereas RMA-2 utilized 40% ACA and 30% AG. For RMCA-1 mixture, 12.5% CSA, 12.5% ACA, and 25% AG were substituted for OPC, whereas RMCA-2 contained 20% CSA, 20% ACA, and 30% AG. All mixtures maintained a constant water-to-binder ratio (w/b) of 57% to ensure comparable setting and workability. The binder-to-fine aggregate ratio was fixed at 1:2 for all mixes. Additionally, paste samples with identical w/b ratios were prepared for each binder system to facilitate analysis of hydration products and microstructural characteristics through XRD and SEM.

2.3. Test Methods

Mortar fluidity was evaluated in accordance with ASTM C1437-20 [

14], whereas the setting time was determined following ASTM C807-21 [

15].

Mortar specimens were demolded 24 h after casting and subjected to water curing at 20 ± 3 °C. Compressive and flexural strengths were evaluated at 1, 7, and 28 days, in accordance with ASTM C109/C109M-21 [

16] and C348-21 [

17], respectively.

UPV was determined in accordance with ASTM C597-22 [

18].

Freeze–thaw resistance was evaluated in accordance with ASTM C666-97 [

19]. The dynamic modulus of elasticity was measured every 30 cycles, and the relative dynamic modulus of elasticity (RDME) was calculated using Equation (1) as follows:

where

represents the fundamental transverse frequency after c cycles of freeze-thaw (Hz) and

represents the fundamental transverse frequency at 0 cycles of freeze-thaw (Hz).

To evaluate hydration products, paste samples cured under water for 28 days were analyzed using XRD. The measurement conditions were as follows: CuKα radiation with a nickel filter, an operating voltage of 30 kV, a current of 20 mA, a scanning speed of 2°/min, and a 2θ range of 5–60°.

Microstructural observations were conducted on paste samples cured for 1 and 28 days using SEM. Hydration was terminated by immersing the samples in acetone for 6 h, followed by vacuum drying for 24 h. Prior to observation, sample surfaces were coated with platinum. An ultra-high resolution field emission-SEM (SU-8220) was utilized to examine the microstructural features.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fluidity

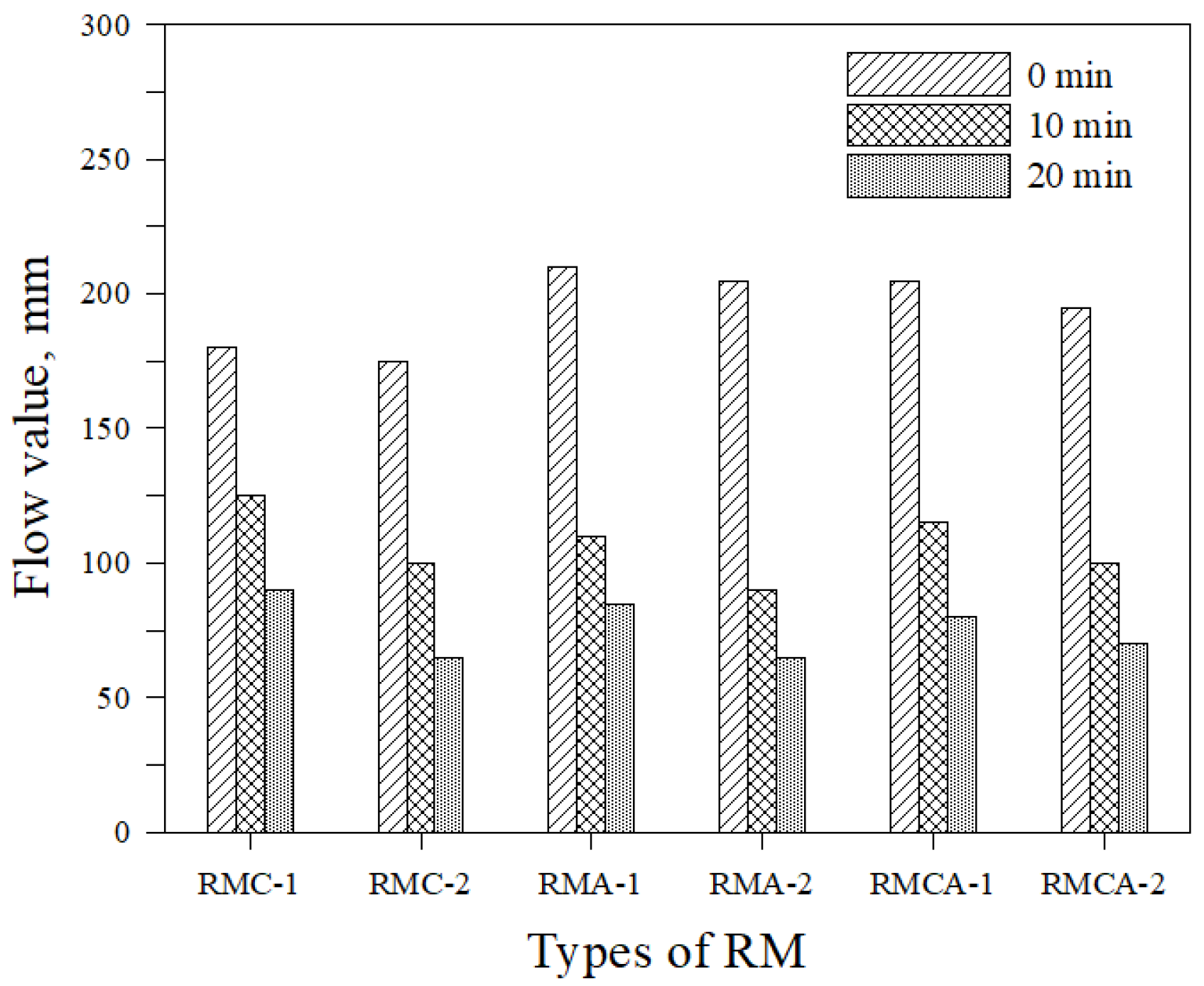

The variation in fluidity of the RMs is shown in

Figure 2. At the initial measurement (0 min), mortars containing ACA (RMA-1 and RMA-2) demonstrate slightly higher flow values compared with those containing CSA (RMC-1 and RMC-2). However, after 10 min, ACA-based mortars experience a more pronounced loss in fluidity, resulting in lower flow values compared with CSA-based RM. Mortars incorporating both CSA and ACA (RMCA-1 and RMCA-2) demonstrate fluidity trends similar to those of ACA mortars, regardless of the elapsed time.

Meanwhile, increasing the content of aluminate-based binders (CSA + ACA) results in reduced fluidity. For example, the flow values of RMA-2 (14% ACA) are 175, 100, and 65 mm at 0, 10, and 20 min, respectively, whereas RMA-1 (8.75% ACA) records 180, 125, and 90 mm over the same time intervals. Similar trends are observed in both RMC and RMCA mortars.

3.2. Setting Time

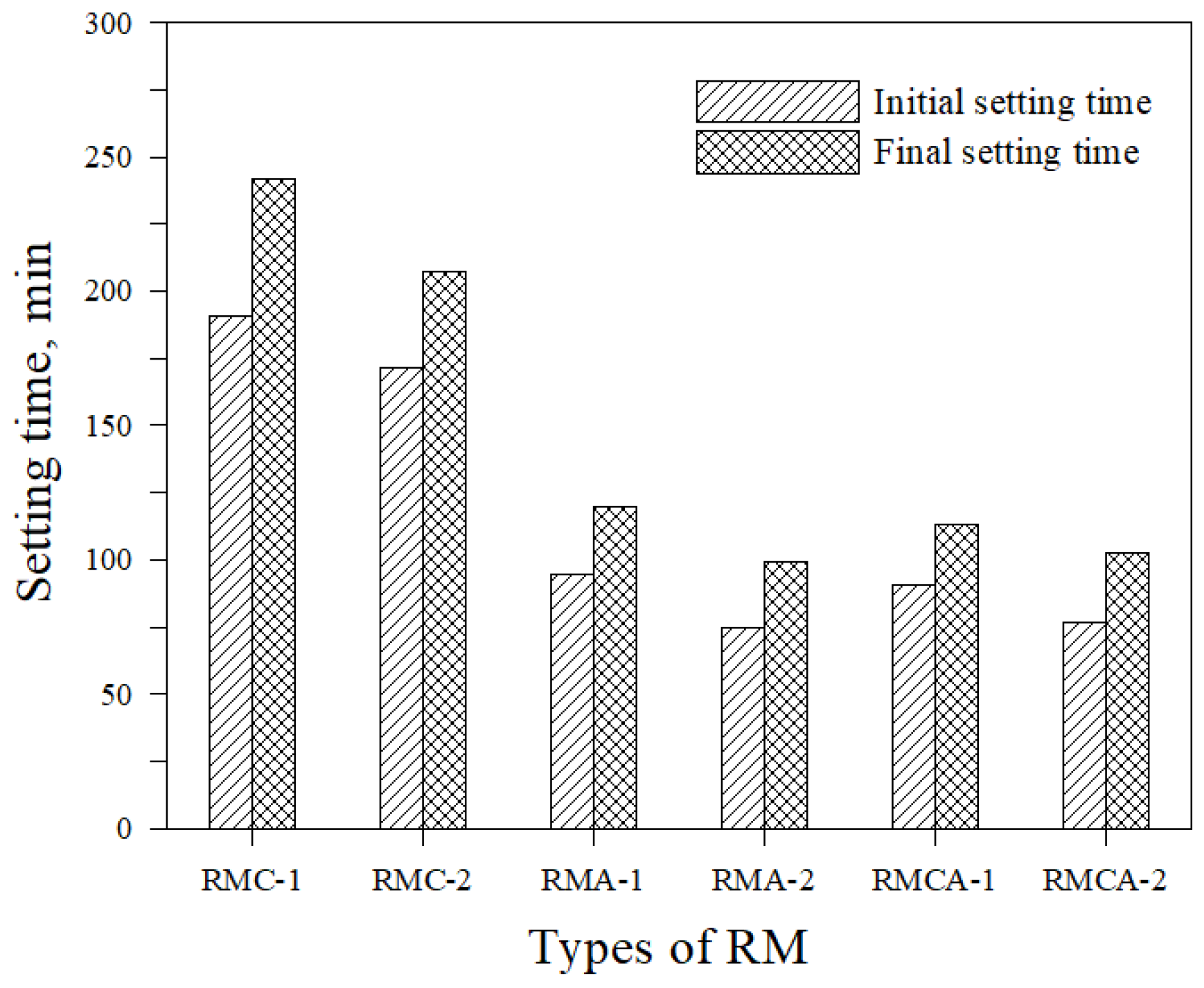

A comparative analysis of the initial and final setting times of the six RMs is shown in

Figure 3. RMC mortars display the longest setting times, whereas RMA and RMCA mortars demonstrate relatively shorter and similar setting behaviors. Notably, the setting times of RMA mortars are approximately 50% shorter than those of RMC mortars. This behavior is attributed to the hydration of C

12A

7, the principal component of ACA, which rapidly forms C

2AH

8 at the early stages of hydration, as represented using Equation (2) [

12].

Increasing the dosage of aluminate-based binders (CSA + ACA) consistently results in shorter setting times, regardless of mortar type.

3.3. Compressive and Flexural Strength

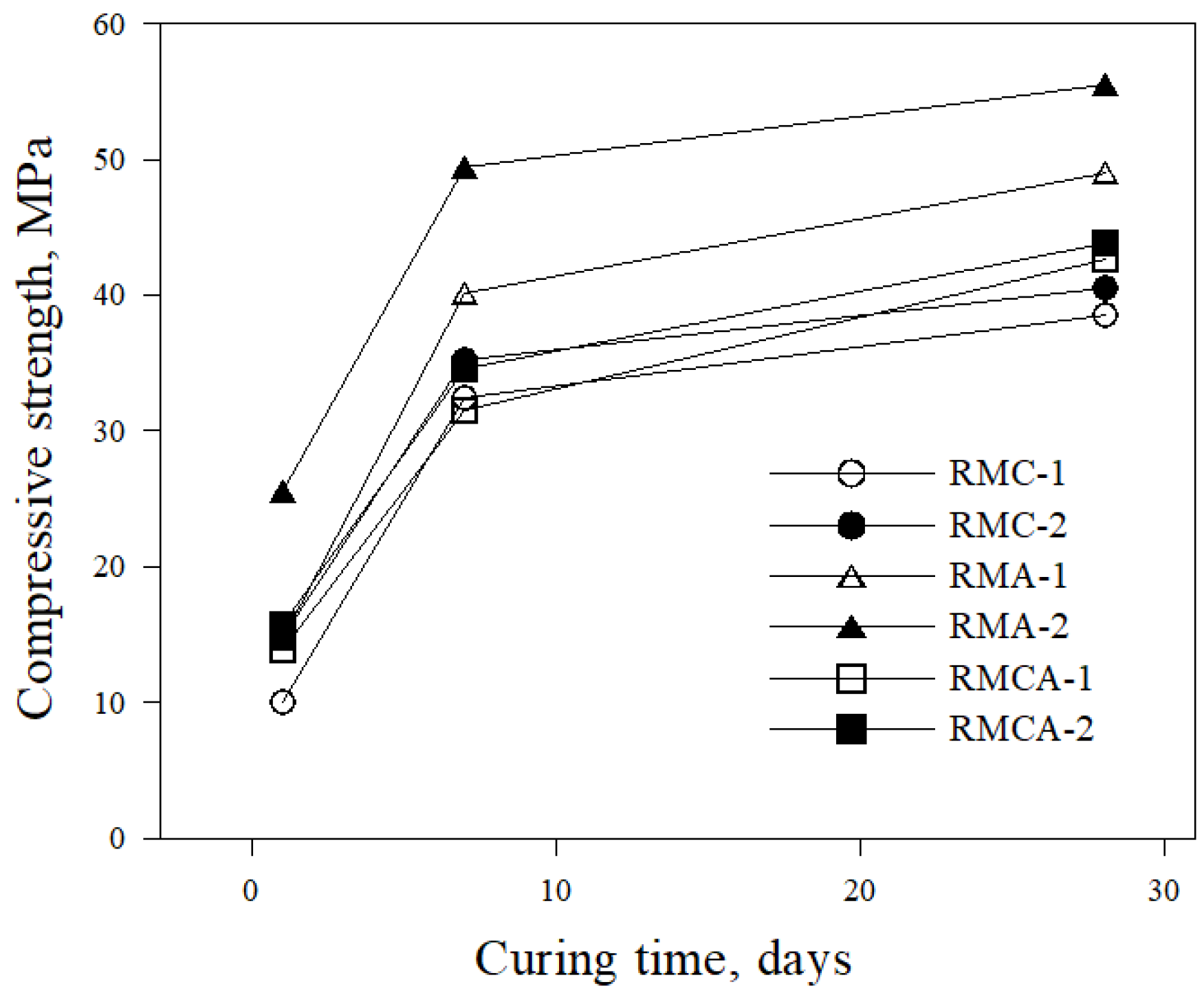

The compressive strength development of the RMs is shown in

Figure 4. Compressive strength increases progressively with curing age. CSA mortars (RMC-1 and RMC-2) display lower compressive strengths compared with ACA mortars (RMA-1 and RMA-2) from the earliest ages. After 1 day of curing, RMA-1 and RMA-2 achieve compressive strengths of approximately 14.7 and 25.6 MPa, respectively, whereas RMC-1 and RMC-2 reach only 10.0 and 14.8 MPa, respectively. The differences become more pronounced after 28 days of curing. The superior performance of ACA mortars is attributed to the formation of aluminate hydrates during hydration, which enhance early strength development [

13,

20].

Furthermore, the effect of binder dosage is evident. RMA-2, containing a higher proportion of ACA, achieves compressive strengths of approximately 25.6, 49.5, and 55.5 MPa at 1, 7, and 28 days, respectively, whereas RMA-1 records lower values of 14.7, 40.2, and 49.0 MPa. In contrast, variations in CSA dosage result in less significant changes in compressive strength.

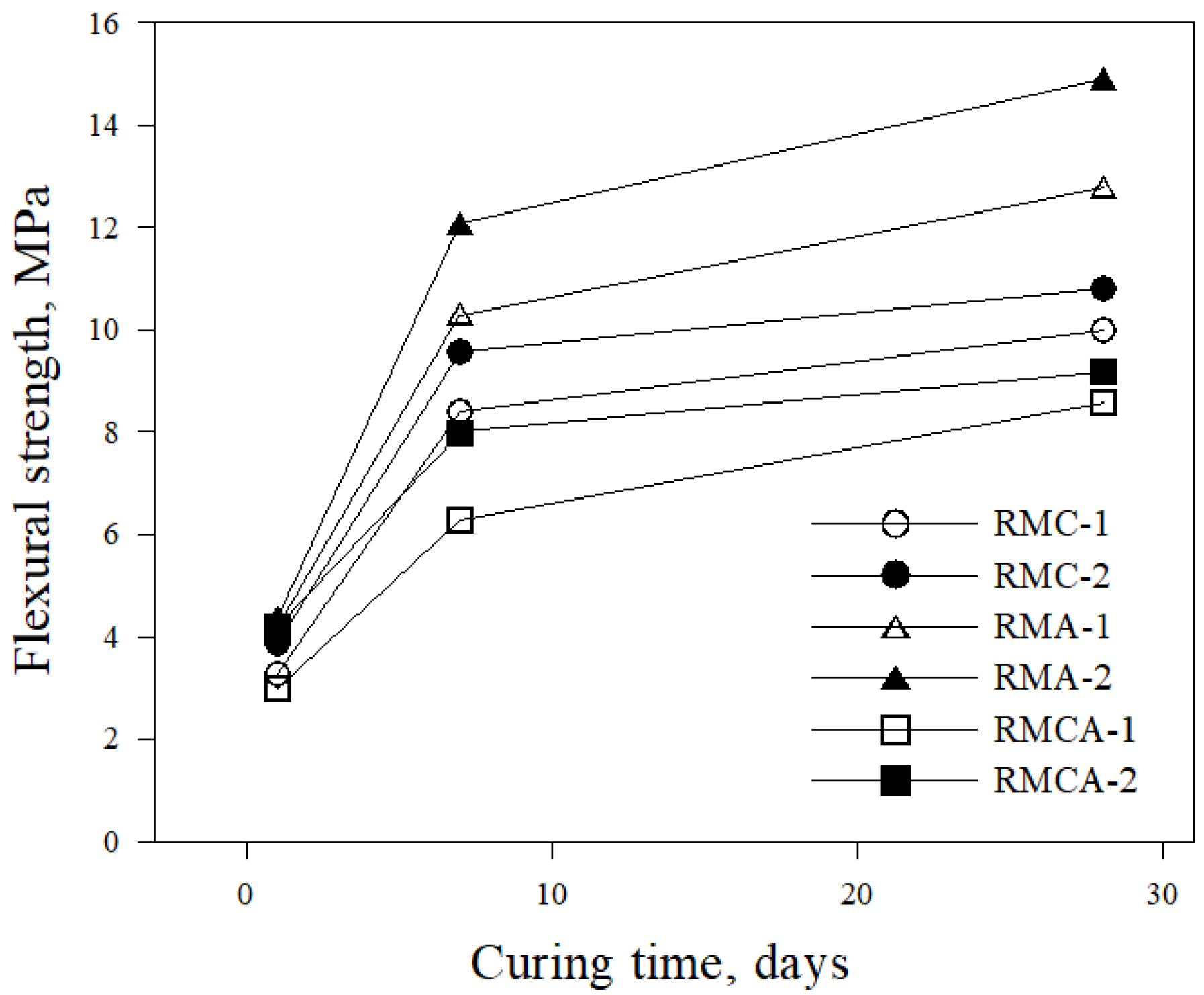

The results of flexural strength are shown in

Figure 5. The flexural performance is influenced by the type of aluminate binder. After 1 day of curing, RMA-2 achieves a flexural strength of approximately 4.3 MPa, compared with 3.8 and 4.2 MPa for RMC-2 and RMCA-2, respectively. After 28 days of curing, the differences are more pronounced: RMA-2 reaches approximately 14.9 MPa, whereas RMC-2 and RMCA-2 record values of 10.8 and 9.2 MPa. These findings validate the superior flexural resistance of ACA mortars compared with that of CSA mortars. However, unlike compressive strength, RMC mortars display slightly higher flexural strength compared with that of RMCA mortars.

Both compressive and flexural strengths are significantly influenced by the dosage of aluminate-based binders, with higher binder content resulting in increased strengths. This enhancement is attributed to variations in the type and quantity of hydration products formed in the RM matrix [

21].

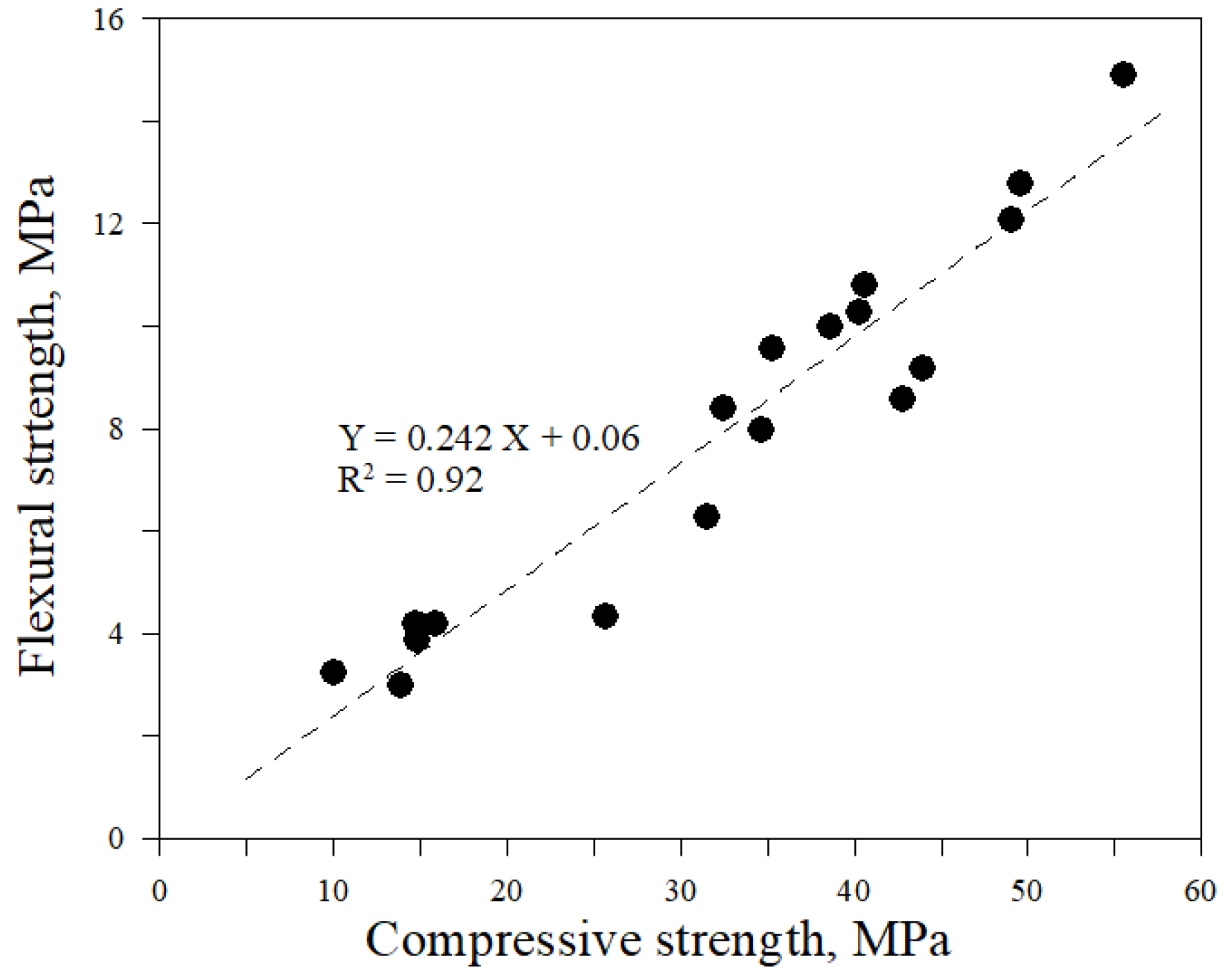

Compressive and flexural strengths are strongly correlated, with an R

2 value of 0.92, as shown in

Figure 6.

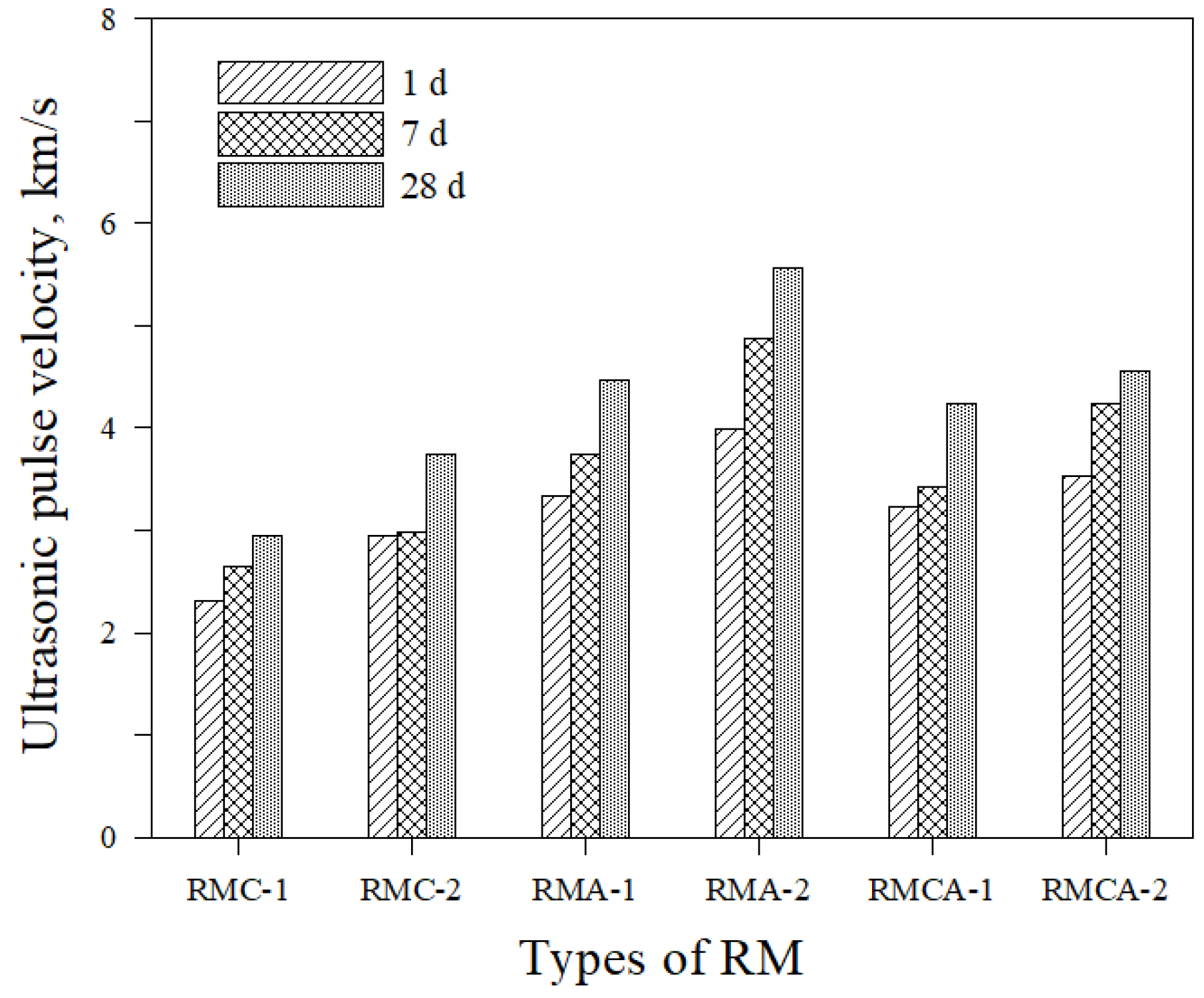

3.4. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV)

The UPV results of the RMs at various curing ages are shown in

Figure 7. UPV values increase with curing age across all mixtures. At each age, mortars incorporating ACA consistently display higher UPV values compared with those containing CSA, which demonstrate relatively lower values. An increase in aluminate-based binder content leads to higher UPV, with this effect being more pronounced in ACA mortars. For example, after 1 day of curing, the UPV of RMC-2 is 2.95 km/s, whereas that of RMA-2 is 3.99 km/s. After 28 days of curing, RMC-2 and RMA-2 reach approximately 3.74 km/s and 5.56 km/s, respectively.

Mortars containing both CSA and ACA (RMCA series) display slightly higher UPV values compared with CSA mortars across all curing ages. Overall, the UPV trends closely match those observed in compressive strength.

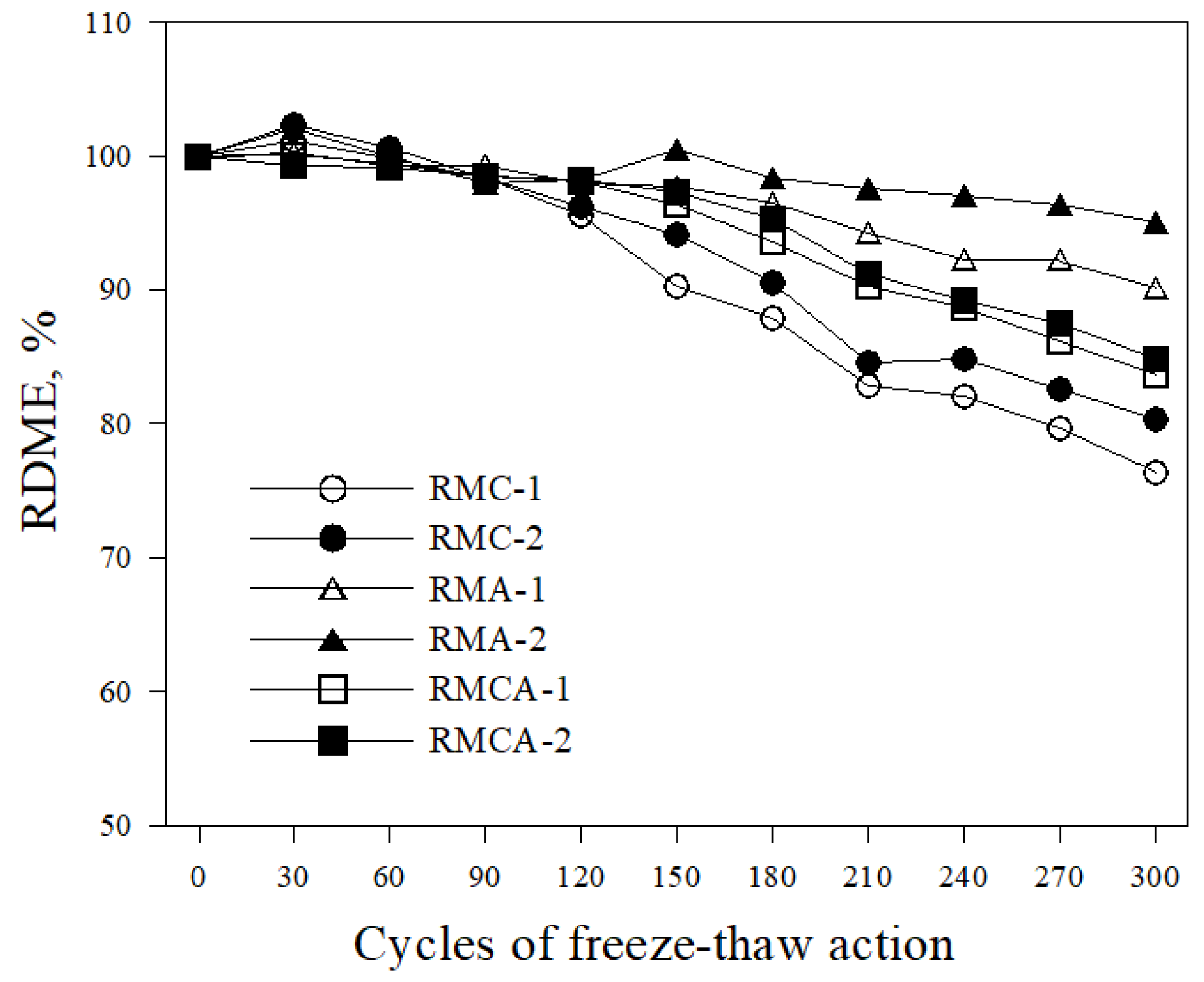

3.5. Freeze-Thaw Resistance

The freeze–thaw resistance of the six RM mixtures was evaluated through exposure tests conducted in accordance with ASTM C666-97 [

19]. The RDME was measured every 30 cycles to evaluate the resistance of each mixture to freeze–thaw damage.

As shown in

Figure 8, after 300 cycles, RMA mortars retain RDME values above 90% (90.1% for RMA-1 and 95.1% for RMA-2), indicating superior freeze–thaw resistance compared with those of RMCA and RMC mortars. Conversely, the RDME of RMC mortars drop below 80% after 300 cycles, indicating comparatively poor resistance to freeze–thaw deterioration.

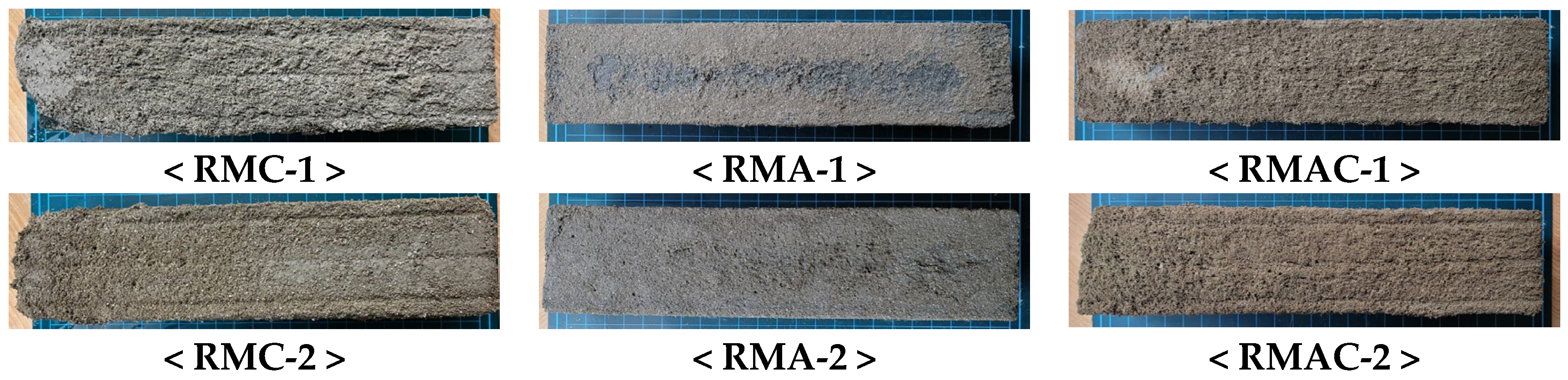

The visual appearance of mortars after 300 cycles is shown in

Figure 9, which indicates that RMC-1 and RMC-2 specimens exhibit severe surface scaling, with evident spalling at edges and noticeable surface softening. In contrast, RMA mortars remain relatively intact, displaying only minor surface cracking and minimal deterioration. RMCA mortars (RMCA-1 and RMCA-2) experienced more significant surface degradation compared with RMA mortars, characterized primarily by surface scaling.

These findings indicate that ACA mortars provide the highest resistance to freeze–thaw action. Accordingly, RMs incorporating ACA are expected to be effective as rapid repair materials for concrete structures in cold regions.

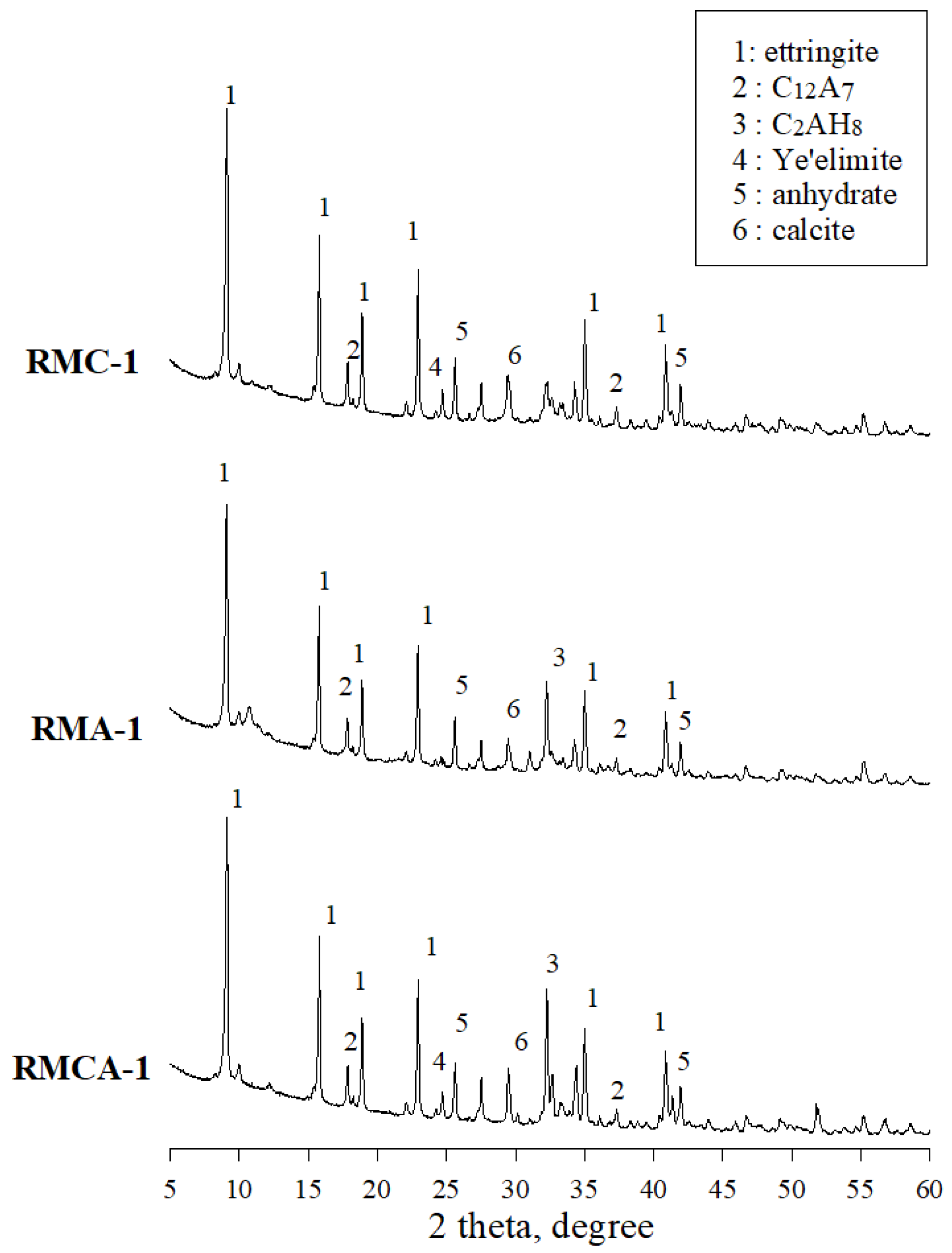

3.6. XRD Analysis

The XRD patterns of paste samples cured for 28 days are shown in

Figure 10, revealing that the hydration products vary depending on the binder type.

In the RMC-1, RMA-1, and RMCA-1 samples incorporating CSA and ACA, strong peaks corresponding to ettringite are observed. Furthermore, peaks corresponding to C

12A

7 and C

2AH

8 are detected, attributed to the combined use of OPC and aluminate-based binders [

12,

13].

For the RMC-1 sample prepared with CSA, the XRD pattern validates the formation of substantial amounts of ettringite through the hydration of ye’elimite (3CaO

3·Al

2O

3·CaSO

4), consistent with the reactions expressed in Equations (3) and (4) [

2].

Distinct C

2AH

8 peaks are observed in the RMA-1 and RMCA-1 samples containing ACA. This phenomenon is attributed to the reaction of C

12A

7, the principal component of ACA, which promotes the consumption of portlandite during hydration and results in the formation of C

2AH

8 as the predominant product [

12].

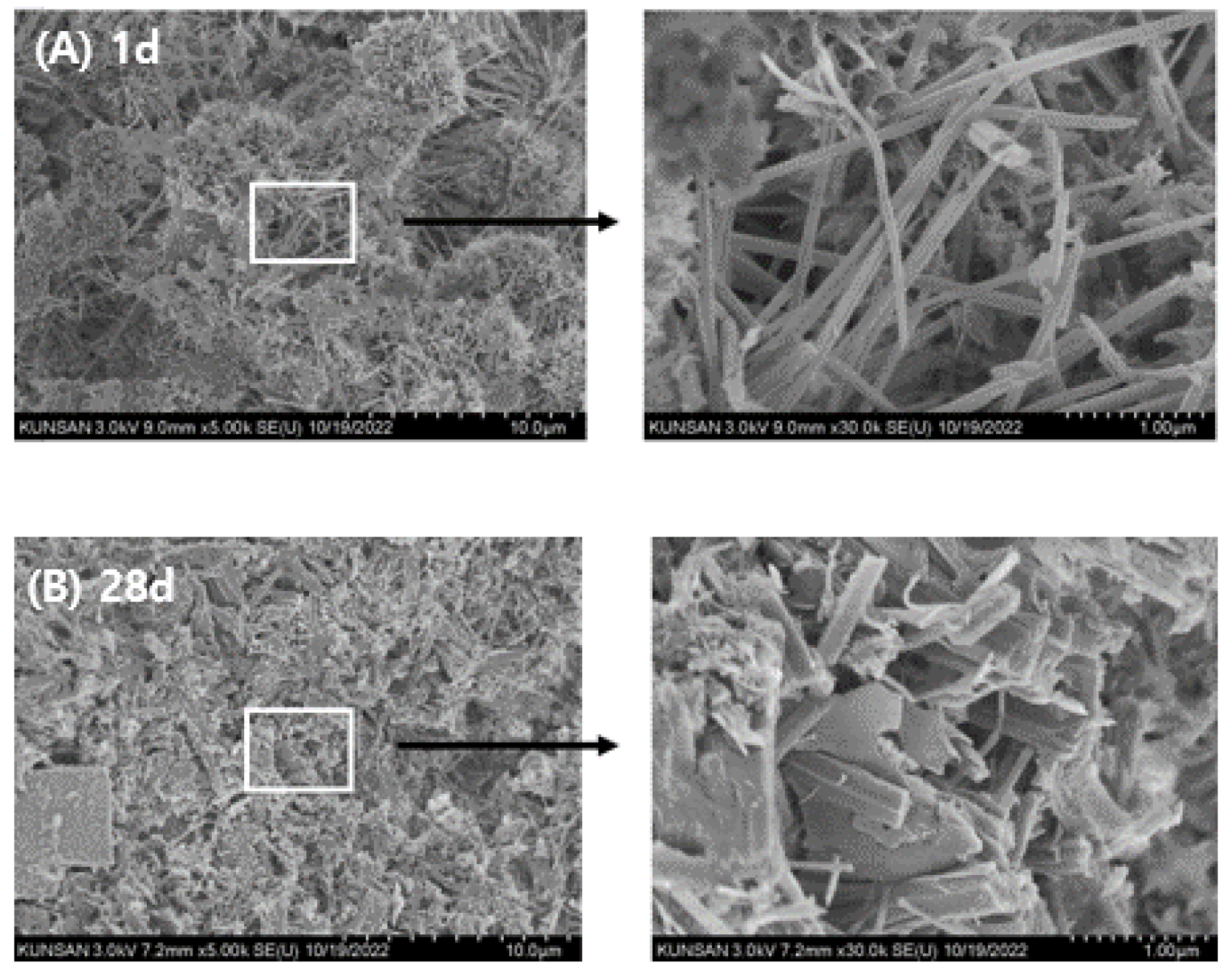

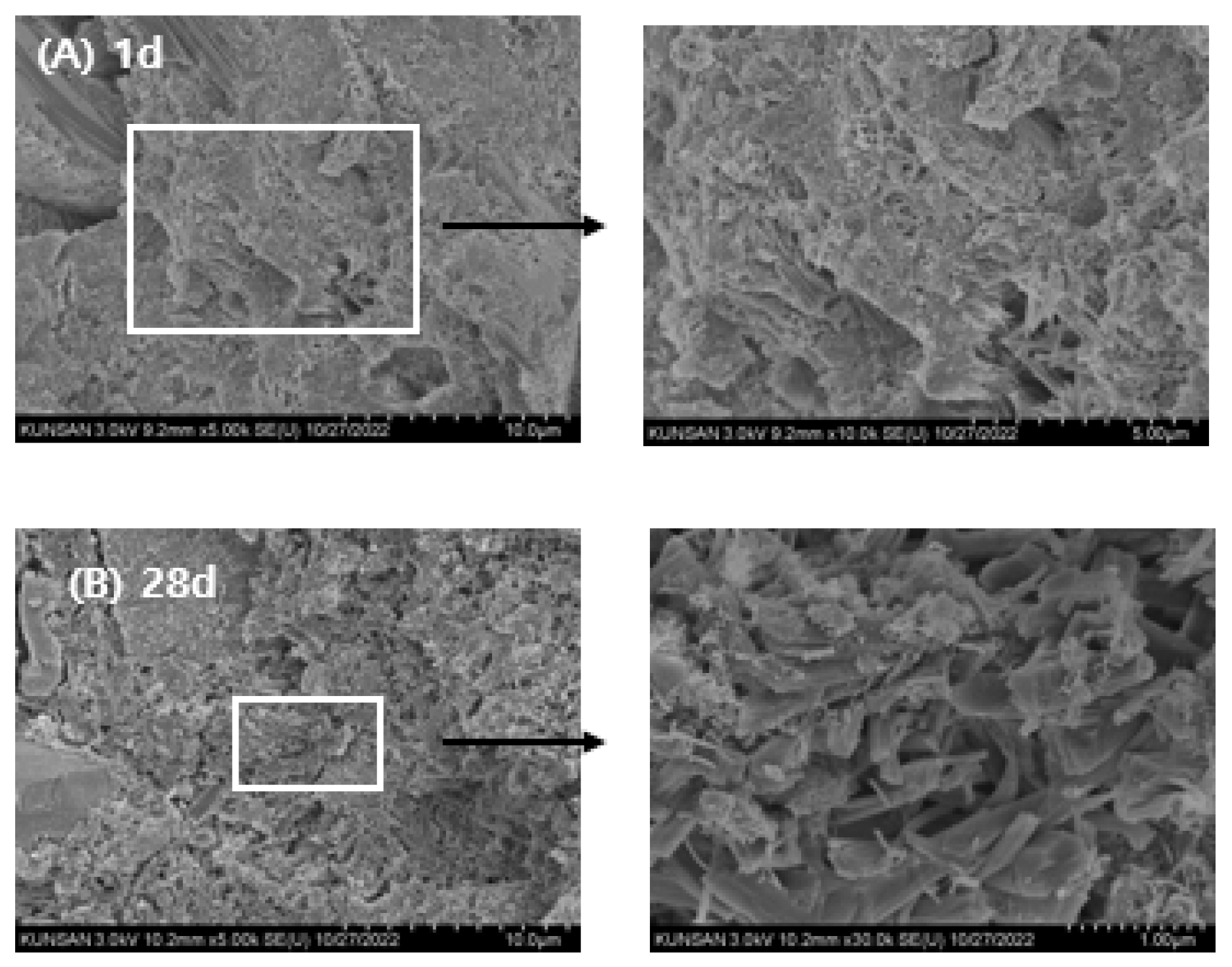

3.7. SEM Observations

The SEM images of the RMC-1 paste are shown in

Figure 11. After 1 day of curing (

Figure 11A), numerous long, needle-like AFt crystals are observed within the pore structure. Minor quantities of portlandite and C–S–H, products of OPC hydration, are also detected, accompanied by a high density of micro-pores. AFm phases are not detected at this stage. After 28 days of curing (Fig. 11B), both needle-like and subhedral AFt crystals are prominent, whereas portlandite is scarcely observed.

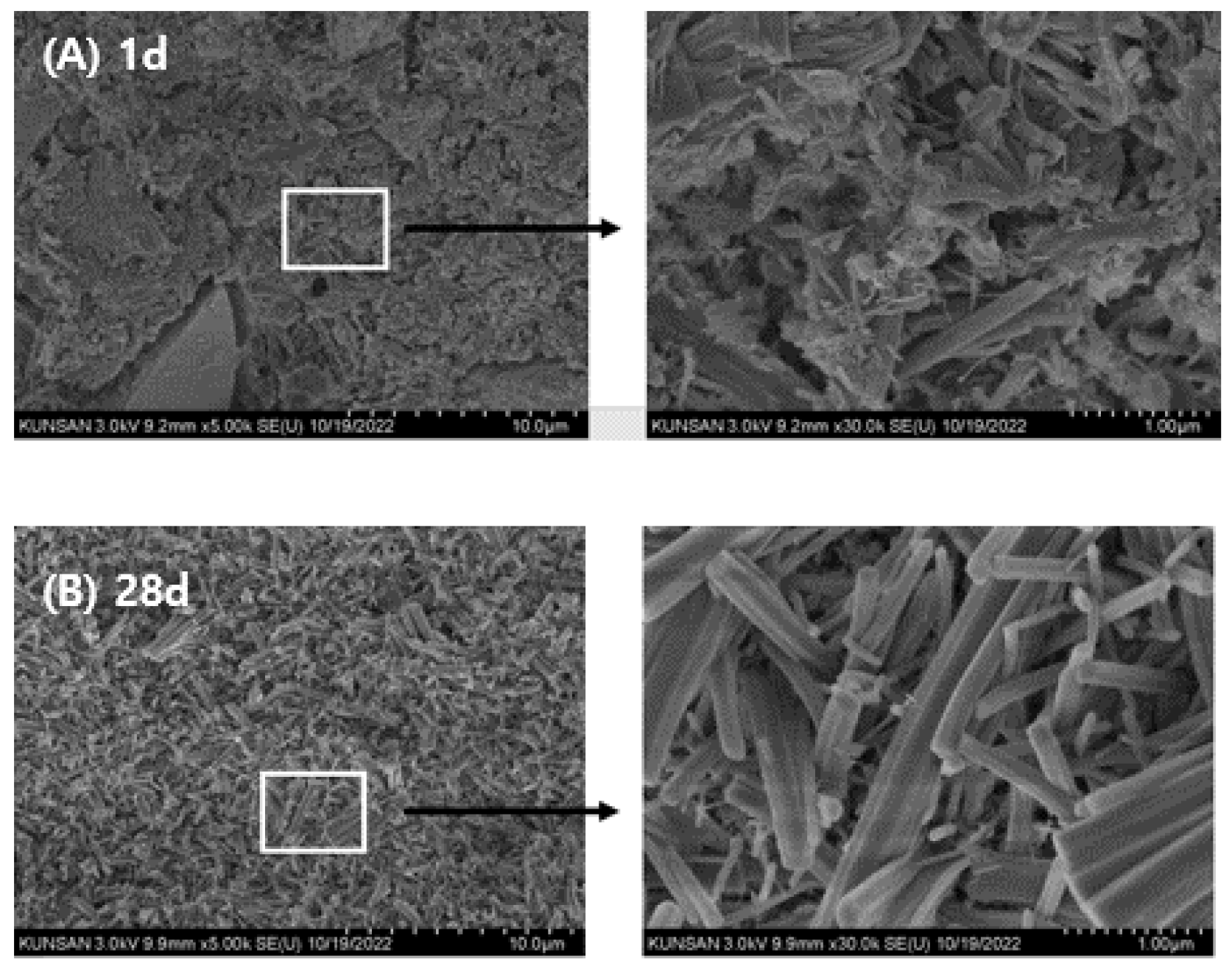

The SEM images of the RMA-1 paste prepared with ACA as the primary binder are shown in

Figure 12. After 1 day of curing (

Figure 12A), the microstructure appears denser compared with RMC-1, with a reduced number of micro-pores. Both subhedral and needle-like AFt crystals are distributed throughout the sample. After 28 days of curing (

Figure 12B), subhedral AFt crystals become the dominant feature.

The SEM images of RMCA-1 are shown in

Figure 13. At the first and 28

th days, the microstructure is comparatively less dense, with numerous pores and cracks. Abundant hexagonal, plate-like portlandite crystals are also observed. Consistent with the XRD results (

Figure 10), ettringite is identified as the primary hydration product in RMCA-1.

These microstructural variations in hydration products are considered to significantly influence the mechanical and durability performance of the RMs.

4. Conclusions

This study experimentally evaluated the mechanical performance and microstructural characteristics of RMs incorporating aluminate-based binders. The conclusions are as follows:

1. The initial flow values of RMA mortars were relatively high; however, they demonstrated a more pronounced loss of fluidity over time. Overall, fluidity decreased as the dosage of aluminate-based binders increased.

2. The setting time was reduced by increasing the amount of CSA and ACA. The setting time of RMA mortars was approximately 50% shorter than that of RMC mortars, primarily attributed to the hydration of C12A7, which represents the primary component of ACA.

3. The compressive and flexural strength results indicated that the strength development of ACA mortars was superior to that of CSA mortars from the earliest ages. For example, the compressive strength of RMA-2 after 28 days of curing was significantly higher by 36.7% compared with that of RMC-2, with the difference further increasing to 74.1% after 1 day of curing. A similar trend was observed in flexural strength.

4. Higher contents of aluminate-based binders resulted in increased UPV values. The incorporation of ACA had a particularly positive effect on UPV; at the first and 28th days, the UPVs of RMA-2 were 3.99 and 5.56 km/s, which were approximately 35% and 48% higher than those of RMC-2, respectively.

5. In freeze–thaw resistance tests, RMA mortars maintained relative RDME values above 90%, whereas those of RMC mortars fell below 80%, validating the significance of ACA in enhancing durability. After 300 cycles, visual inspection revealed that RMA specimens remained relatively intact, displaying only minor surface cracks. In contrast, RMC specimens demonstrated pronounced surface scaling, spalling, and softening.

6. XRD analysis revealed that RMC samples generated significant amounts of ettringite through the hydration of ye’elimite, whereas ACA samples primarily generated C2AH8, resulting from C12A7 hydration. These distinct hydration products are believed to significantly impact the mechanical properties and durability of the mortars. SEM observations further corroborated these findings, demonstrating that ACA mortars possessed denser microstructures even at early ages.

The experimental results are anticipated to provide valuable insights for selecting the optimal repair materials for deteriorated concrete structures.

Author Contributions

Data curation, S.L.; methodology, S.L. and S.P.; funding acquisition, S.L.; formal analysis, S.L. and S.P.; writing-original draft preparation, S.L.; writing-review and editing, S.L. and S.P.; investigation, S.P.; validation, S.L.; supervision, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement (KAIA) grant funded by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (RS-2022-0014256640182064070202).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RM |

Repair mortars |

| CSA |

Calcium sulfoaluminate |

| AG |

Anhydrite gypsum |

| UPV |

Ultrasonic pulse velocity |

| RDME |

Relative dynamic modulus of elasticity |

| OPC |

Ordinary Portland cement |

| ACA |

Amorphous calcium aluminate |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

References

- Vasquez, I.B.; Trauchessec, R.; Tobon, J.I.; Lecomte, A. Influence of ye’elimite/anhydrate ratio on PC-CSA hybrid cements. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 22, 100778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargis, C.W.; Telesca, A.; Monteiro, P.J.M. Calcium sulfoaluminate hydration in the presence of gypsum, calcite, and vaterite. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 65, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coumes, C.C.D.; Dhoury, M.; Champenois, J.B.; Mercier, C.; Damidot, D. Physico-chemical mechanisms involved in the acceleration of the hydration of calcium sulfoaluminate cement by lithium ions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 96, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, G.; Telesca, A.; Valenti, G.L. A porosimetric study of calcium sulfoaluminate cement pastes cured at early ages. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1042–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.A.; Hargis, C.W.; Juenger, M.C. Understanding expansion in calcium sulfoaluminate–belite cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Qian, Z.; Gu, D.; Pan, J. Repair concrete structures with high-early-strength engineered cementitious composites (HES-ECC): material design and interfacial behavior. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 68, 106060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Rahul, A.V.; Mohan, M.K.; De Schutter, G.; Van Tittelboom, K. Recent progress and technical challenges in using calcium sulfoaluminate (CSA) cement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 137, 104908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; You, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Jia, X. A method for assessing bond performance of cement-based repair materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 68, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.H.; Noh, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, Y.Y. Durability characteristics of Latex modified concrete for bridge deck pavement produced with CSA-based admixture for traffic opening at the age of 24 hours. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2017, 29, 625–631. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Qian, J. Influence of ternesite on the properties of calcium sulfonamides cements blended with fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 72, 482–490. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Sun, D.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Mao, Y.; Song, Z. Properties and hydration characteristics of an iron-rich sulfoaluminate cementitious material under cold temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 168, 107152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Terashima, I.; Asaga, K.; Daimon, M. Influence of Ca(OH)2 and CaSO4·2H2O on hydration reaction of amorphous calcium aluminate. Cem. Concr. Res. 1990, 20, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Terashima, I.; Asaga, K.; Daimon, M. A study of hydration of amorphous calcium aluminate by selective dissolution analysis. Cem. Concr. Res. 1990, 20, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM Standards Publication. Standard Test Method for Flow of Hydraulic Cement Mortar, ASTM C1437-20; American Society for Testing Materials; West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM Standards Publication. Standard Test Method for Time of Setting of Hydraulic Cement Mortar by Modified Vicat Needle, ASTM C807-21; American Society for Testing Materials; West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM Standards Publication. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars, ASTM C109/C109M-21; American Society for Testing Materials; West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM Standards Publication. Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Hydraulic-Cement Mortars, ASTM C348-21; American Society for Testing Materials; West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM Standards Publication. Standard Test Method for Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity Through Concrete, ASTM C597-22; American Society for Testing Materials; West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM Standards Publication. Standard Test Method for Resistance of Concrete to Rapid Freezing and Thawing, ASTM C666-97; American Society for Testing Materials; West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1997.

- Pelletier, L.; Winnefeld, F.; Lothenbach, B. The ternary system Portland cement–calcium sulphoaluminate clinker–anhydrite: hydration mechanism and mortar properties. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, N.; Xu, L. Hydration evolution and compressive strength of calcium sulphoaluminate cement constantly cured over the temperature range of 0 to 80 °C. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 100, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).